Abstract

Aim

To characterise the epidemiology, clinical features and treatment of paediatric cellulitis.

Methods

A retrospective study of children presenting to a paediatric tertiary hospital in Western Australia, Australia in 2018. All inpatient records from 1 January to 31 December 2018 and emergency department presentations from 1 July to 31 December 2018 were screened for inclusion.

Results

302 episodes of cellulitis were included comprising 206 (68.2%) admitted children and 96 (31.8%) non-admitted children. The median age was 5 years (IQR 2–9), 40 (13.2%) were Aboriginal and 180 (59.6%) boys. The extremities were the most commonly affected body site among admitted and non-admitted patients. There was a greater proportion of facial cellulitis in admitted patients (27.2%) compared with non-admitted patients (5.2%, p<0.01). Wound swab was the most frequent microbiological investigation (133/302, 44.0%), yielding positive cultures in the majority of those tested (109/133, 82.0%). The most frequent organisms identified were Staphylococcus aureus (94/109, 86.2%) (methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (60/94, 63.8%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and Streptococcus pyogenes (22/109, 20.2%) with 14 identifying both S. aureus and S. pyogenes. Intravenous flucloxacillin was the preferred antibiotic (154/199, 77.4%), with median intravenous duration 2 days (IQR 2–3), oral 6 days (IQR 5–7) and total 8 days (IQR 7–10).

Conclusions

Cellulitis is a common reason for presentation to a tertiary paediatric hospital. We confirm a high prevalence of extremity cellulitis and demonstrate that children with facial cellulitis often require admission. Cellulitis disproportionately affected Aboriginal children and children below 5 years. Prevention of cellulitis involves early recognition and treatment of skin infections such as impetigo and scabies.

Keywords: epidemiology, microbiology, dermatology

What is known about the subject?

Cellulitis is a common skin infection, caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Cellulitis contributes the largest portion of the disease burden caused by S. pyogenes in Australia.

Cellulitis in children includes periorbital infection and infection of the extremities.

What this study adds?

Cellulitis is a common condition in children accounting for 1.1% of presentations to the paediatric tertiary hospital in Western Australia.

Facial cellulitis is a common cause for admission to hospital, with a large proportion of this being periorbital cellulitis.

Children under 5 years and Australian Aboriginal children are disproportionately admitted for cellulitis.

Introduction

Cellulitis is a localised skin infection caused by disruption of the physical barrier allowing pathogen entry.1 2 In children it is commonly caused by trauma, insect bites or varicella, predominantly affecting the face or extremities.2–4 Common pathogens are Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci (GAS)) and Staphylococcus aureus.1 2 5–7 Cellulitis is non-purulent, making pathogen detection challenging, hence GAS contribution may be underestimated.1 In Australia, cellulitis contributes the greatest burden of GAS disease across all ages, ahead of impetigo, pharyngitis and invasive GAS.8 An improved understanding of the burden of paediatric cellulitis will inform the role for a GAS vaccine in cellulitis prevention.

Although presumably common, few studies describe the burden of cellulitis in Australian children. The proportion of admissions, clinical features and treatment of cellulitis in hospitalised children in Australia remains unknown. In one linked dataset, skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) accounted for 3% of all paediatric hospital admissions, with cellulitis as the second most frequent admission reason.9 Aboriginal children were 15 times more likely to be admitted for SSTI compared with non-Aboriginal.9 Furthermore, SSTIs are recognised as the most common group of bacterial infections in children.10 Although cellulitis is often managed in primary care, hospitalisation is required for severe, progressive cellulitis.9 11 12

We aimed to describe the epidemiology, clinical features, treatment and adherence to antibiotic guidelines for cellulitis in children presenting to hospital.

Methods

Study design and population

A retrospective chart review was conducted at Perth Children’s Hospital (PCH), the only tertiary paediatric centre in Western Australia (WA) with an estimated 60 000 presentations to the emergency department (ED) annually.13

Records with a primary diagnosis of cellulitis were identified using the International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 coding (online supplemental table S1). At PCH, all inpatient records from 1 January to 31 December 2018 were screened for inclusion. Due to the time constraints of the study, ED presentations from 1 July to 31 December 2018 only were reviewed. Exclusion criteria were patients aged ≥16 years, alternative diagnosis more likely on detailed chart review or where insufficient documentation was available to assess for inclusion. Orbital cellulitis and odontogenic cellulitis were excluded from this review, as their management is considerably different from that of traditional cellulitis.

bmjpo-2021-001130supp001.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

Cellulitis (ICD10 codes L03.01–L03.11 and H60.1–H60.13) is a bacterial infection of the superficial layers of the skin (epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissues) characterised by erythema, pain, warmth, swelling and rapid progression. Recurrent cellulitis was defined as an additional admission for cellulitis occurring >30 days from the index diagnosis to exclude the possibility of counting relapses or treatment failure (representation within 30 days of hospital discharge). SSTI includes cellulitis, impetigo, skin abscess, scabies and fungal infections. Extremities are the hands and feet including the finger and toes. Geographical location was ascertained by postcode, grouped according to Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Structure on the basis of relative access to healthcare services.14

The hospital in the home (HITH) service consists of a team of trained clinical nurses. It provides acute care at home for children who are medically stable and require ongoing regular medical care. They conduct daily home visits to provide treatments such as intravenous antibiotics, dressings and clinical assessments. Patients can be referred to HITH directly from ED in order to avoid an admission or from an inpatient unit to facilitate early discharge.

Data collection

Data were extracted from paper and electronic hospital records, including demographics, admission duration, clinical findings, investigations, management and outcomes. The characteristics assessed included age, Aboriginal status, geographical location, presence of common comorbidities and recurrent cellulitis. Data were captured and stored in a standardised purpose-built REDCap database by a medically trained abstractor.15 16 Adherence to treatment duration was assessed against the intravenous to oral switch guidelines.17

Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive and comparative statistics. According to the 2016 census data, 3.9% of the WA paediatric population are Aboriginal.18 The proportion of Aboriginal children in the study was compared with the census data using a binomial probability test. The frequency of cellulitis affecting specific body sites, identified causes, investigations performed and follow-up with a paediatrician were compared between admitted and non-admitted patients using Pearson’s χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. χ2 tests were used to compare the age of study participants to the 2016 WA population data.19 Data were analysed using Stata V.16.0 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 16).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

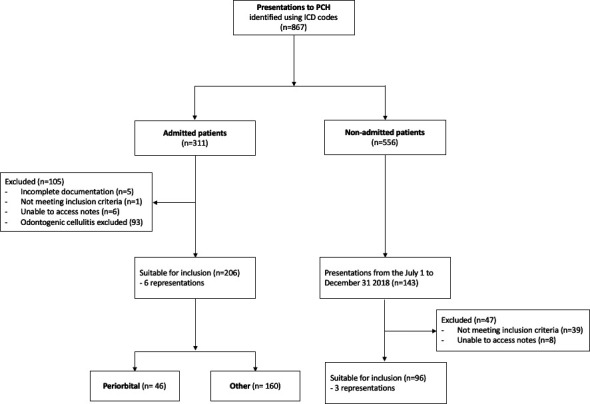

Eight hundred and sixty-seven patients with a primary diagnosis of cellulitis presented to PCH in 2018. This included 311 admitted patients and 556 non-admitted patients. Hospital coding errors were present in 11.8% (102/867) of cases: 40 patients excluded with an alternative primary SSTI and 62 with different primary diagnoses coded in the ED notes compared with the discharge summary. Ninety-three patients with odontogenic cellulitis were also excluded. Of the remaining 672 patients, 206 (30.6%) were included in the 12-month admitted cohort and 96 (14.2%) in the 6-month non-admitted cohort. Further details on the exclusion reasons are presented in figure 1. Cellulitis accounted for 1.1% (672/62 985) of all presentations and 0.8% (206/26 884) of annual admissions to PCH.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants included in the study. ICD, International Classification of Disease; PCH, Perth Children’s Hospital.

One hundred and eighty (59.6%) children were boys (table 1). Eleven (3.6%) children re-presented with cellulitis during the study period: 3 children with recurrent cellulitis of a different body site, 4 children with treatment failure requiring re-admission to hospital, 1 child requiring admission after unsuccessful discharge from ED and 3 children with treatment failure representing to ED.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Total (n=302) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 180 (59.6) |

| Female | 122 (40.4) |

| Age group (years) | |

| <5 | 147 (48.7) |

| 5–9 | 87 (28.8) |

| 10–14 | 52 (17.2) |

| 15 | 16 (5.3) |

| Indigenous status | |

| Aboriginal | 40 (13.2) |

| Non-Aboriginal | 262 (86.8) |

| Geographical location | |

| Metropolitan | 282 (93.4) |

| Regional/remote | 17 (5.6) |

| International | 3 (1.0) |

| Previous admission | |

| Cellulitis | 27 (8.9) |

| Other SSTI | 23 (7.6) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Eczema | 18 (6.0) |

| Surgery | 3 (1.0) |

| URTI | 13 (4.3) |

Values are n (%).

SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Children below 5 years were over-represented in the study population, 147/302 (48.7%, p<0.001) (table 2). The median age of children admitted to hospital was 5 years (IQR 2–9) and for non-admitted patients 5 years (IQR 2–8).

Table 2.

Comparison of study participants and the WA population by age group

| Age group (years) | Study | WA population* | P value |

| <5 | 147 (48.7) | 161 727 (31.9) | p<0.001 |

| 5–9 | 87 (28.8) | 164 153 (32.4) | |

| 10–14 | 52 (17.2) | 150 806 (29.8) | |

| 15† | 16 (5.3) | 29 934 (5.9) | |

| Total | 302 | 506 620 |

Values are n (%).

*WA population data from the 2016 Australian census.19

†Children aged 16 years and above were excluded from the study.

WA, Western Australia.

Aboriginal children with cellulitis (40/302, 13.2% (95% CI: 9.4% to 17.1%)) were significantly over-represented in the study population compared with being 3.9% of the WA paediatric population (p<0.001) (table 3). Aboriginal children were more likely to be admitted to hospital (36/40, 90.0% (95% CI: 81% to 99%)) than their non-Aboriginal peers (170/262, 64.9% (95% CI: 59% to 71%), p<0.001) (table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of study participants and the WA population by Indigenous status

| Study population | WA population* (%) | P value | |

| Aboriginal | 40 (13.2%) (95% CI: 9.4% to 17.1%) |

3.9 | p<0.001 |

| Non-Aboriginal | 262 (86.8%) (95% CI: 82.9% to 90.6%) |

96.1 | |

| Total | 302 (100%) | 100 |

*Data from the 2016 Australian Census.18

WA, Western Australia.

Table 4.

Proportion of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal patients admitted to hospital

| Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | P value | |

| Admitted | 36 (90) (95% CI: 81% to 99%) |

170 (65) (95% CI: 59% to 71%) |

p<0.001 |

| Non-admitted | 4 (10) (95% CI: 1% to 19%) |

92 (35) (95% CI: 29% to 41%) |

|

| Total | 40 | 262 |

Values are n (% (95% CI)).

The most common causes of cellulitis in the study group were insect bites (66/302, 21.8%), trauma (60/302, 19.9%) and impetigo (17/302, 5.6%) (table 5). In both groups, the most affected body location was the extremities (119/302, 39.4%). The proportion of facial cellulitis was significantly greater among admitted patients compared with non-admitted patients (56/206, 27.2% vs 5/96, 5.2%; p<0.001).

Table 5.

Possible causes and location of cellulitis

| Admitted (n=206) | Non-admitted (n=96) | ||

| Possible source | |||

| Unknown | 76 (36.9) | 30 (31.2) | p=0.339 |

| Skin sore | 17 (8.3) | 0 (0) | p=0.004 |

| Trauma | 45 (21.8) | 15 (15.6) | p=0.207 |

| Insect bite | 31 (15.0) | 35 (36.5) | p<0.001 |

| Lymphoedema | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | – |

| Other* | 36 (17.5) | 16 (16.7) | p=0.862 |

| Location† | |||

| Face | 56 (27.2) | 5 (5.2) | p<0.001 |

| Head and neck | 9 (4.4) | 3 (3.1) | p=0.758 |

| Upper limbs | 14 (6.8) | 13 (13.5) | p=0.056 |

| Torso | 8 (3.9) | 7 (7.3) | p=0.255 |

| Groin and buttocks | 11 (5.3) | 16 (16.7) | p=0.001 |

| Lower limbs | 54 (26.2) | 21 (21.9) | p=0.416 |

| Extremities | 76 (36.9) | 43 (44.8) | p=0.191 |

Values are n (%).

*Other includes animal bite, recent injection site, rash, wound or foreign body infection and sinusitis.

†Some cases involved infection of multiple sites.

Most admitted patients (199/206, 96.6%) received intravenous antibiotics, frequently flucloxacillin (154/199, 77.4%) for a median duration of 2 days (IQR 2–3) before step-down to oral antibiotics (table 6). The median duration of oral antibiotics was 6 days (IQR 5–7). The median total duration of antibiotic therapy was 8 days (IQR 7–10). The most common intravenous antibiotic regimen for periorbital cellulitis was intravenous ceftriaxone and flucloxacillin in combination (38/46, 82.6%).

Table 6.

Management and outcomes of patients admitted to PMH/PCH in 2018

| Total | Periorbital | Other | |

| (n=206) | (n=46) | (n=160) | |

| Duration of intravenous antibiotics, days, median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Intravenous antibiotic, n (%) | n=199 | n=45 | n=154 |

| Flucloxacillin | 154 (77.4) | 41 (91.1) | 113 (73.3) |

| Cefotaxime | 2 (1.0) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Ceftriaxone | 47 (23.6) | 41 (91.1) | 6 (3.9) |

| Cefazolin | 38 (19.1) | 5 (11.1) | 33 (21.4) |

| Clindamycin | 10 (5.0) | – | 10 (6.5) |

| Cotrimoxazole | 2 (1.0) | – | 2 (1.3) |

| Benzylpenicillin | 1 (0.5) | – | 1 (0.6) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 15 (7.5) | 4 (8.9) | 11 (7.1) |

| Vancomycin | 27 (13.6) | 2 (4.4) | 25 (16.2) |

| Other | 3 (1.5) | – | 3 (1.9) |

| Duration of oral antibiotics, days, median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 7 (5–8) | 5 (5–7) |

| Oral antibiotic on discharge, n (%) | n=192 | n=42 | n=150 |

| Flucloxacillin | 20 (10.4) | 1 (2.4) | 19 (12.7) |

| Cephalexin | 103 (53.6) | 13 (30.9) | 90 (60.0) |

| Clindamycin | 8 (4.2) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (4.7) |

| Cotrimoxazole | 20 (10.4) | 2 (4.8) | 18 (12.0) |

| Amox/clav duo forte | 37 (19.3) | 24 (57.1) | 13 (8.7) |

| Amoxicillin | 2 (1.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 4 (2.1) | – | 4 (2.7) |

| Total duration of antibiotic therapy, median (IQR) | 8 (7–10) | 9 (8–11) | 8 (7–10) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 52 (25.2) | – | 52 (32.5) |

| Duration of admission, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| Discharged to HITH, n (%) | 16 (7.8) | 9 (19.6) | 7 (4.4) |

| Follow up with paediatrician documented, n (%) | 80 (38.8) | 15 (32.6) | 65 (40.6) |

HITH, hospital in the home; PCH, Perth Children’s Hospital; PMH, Princess Margaret Hospital for Children.

Sixteen (5.3%) admitted children were discharged to the HITH programme for further intravenous antibiotics. The majority of these children had periorbital cellulitis (9/16, 56.3%).

Fifty-two patients underwent surgical procedures including subcutaneous abscess drainage (37/52, 71.2%), finger or toe-nail removal (14/52, 26.9%) and foreign body removal (1/52, 1.9%).

Most non-admitted patients received oral antibiotics only (95/96, 99.0%), commonly cephalexin (70/95, 73.7%) for a median duration of 5 days (IQR 5–7). Three patients received parenteral antibiotics (online supplemental table S2). Documented follow-up was less likely in non-admitted patients compared with those admitted (11.5% vs 38.8%, p<0.01).

The most frequent investigations were full blood count, C reactive protein and wound swab (table 7). Blood cultures were performed in 45.6% (94/206) of admitted cases with only one positive results: coagulase negative Staphylococcus, a probable skin contaminant. Investigations were less common in non-admitted patients (p<0.001) (table 7).

Table 7.

Investigations carried out in children presenting with cellulitis

| Admitted | Non-admitted | ||

| (n=206) | (n=96) | ||

| Full blood count performed, n (%) | 168 (81.6) | 5 (5.2) | p<0.001 |

| White blood cell, median (IQR) | 11.9 (8.9–15.5) | 8.56 (7.95–11.2) | |

| Elevated,* n (%) | 96 (57.1) | 1 (20.0) | |

| C reactive protein performed, n (%) | 166 (80.6) | 5 (5.2) | p<0.001 |

| C reactive protein, median (IQR) | 13.5 (5–36) | 2.6 (2.4–5.5) | |

| Elevated,* n (%) | 111 (66.9) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Blood culture performed, n (%) | 94 (45.6) | 2 (2.1) | p<0.001 |

| Organism identified, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | – | |

| Wound swab performed, n (%) | 120 (58.3) | 13 (13.5) | p<0.001 |

| Organisms identified, n (%) | 99 (82.5) | 10 (76.9) | |

| Imaging, n (%) | 123 (59.7) | 14 (14.5) | p<0.001 |

| Ultrasound scan, n (%) | 35 | 3 | |

| X-ray, n (%) | 71 | 12 | |

| CT, n (%) | 13 | – | |

| MRI, n (%) | 4 | – |

*Elevated as per laboratory reported reference range.

Wound swabs yielded pathogens in 36.1% (109/302) of patients. S. aureus was most frequently identified (n=94, 86.2%): 60 (63.8%) methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA); 34 (36.2%) methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and 22 (20.2%) S. pyogenes (table 8). Fourteen children had mixed gram-positive infections: MSSA and S. pyogenes (n=10); MRSA and S. pyogenes (n=3); MSSA and MRSA (n=1). S. pyogenes was detected in isolation in only nine cases.

Table 8.

Microorganisms identified on wound swab

| Microorganism | Admitted (n=99) | Non-admitted (n=10) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 20 | 2 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 86 | 8 |

| Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus | 54 | 6 |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 32 | 2 |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 1 | – |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | 1 |

| Other* | 7 | – |

*Other includes Staphylococcus intermedius, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus intermedius, mixed anaerobes, Eikenella corrandes, Pasteurella multocida.

Eight children with recurrent cellulitis had positive wound swabs for MRSA.

Discussion

This study demonstrates four key findings: (1) cellulitis is common accounting for 1.1% of all presentations to the tertiary hospital; (2) patients with facial cellulitis are more frequently admitted to hospital; (3) children under 5 years and Aboriginal children are disproportionately affected by cellulitis and (4) 3.6% of the cohort had recurrent cellulitis.

We confirm that paediatric cellulitis accounts for a significant burden on the hospital system, consistent with previous linked data showing 3% of paediatric hospital admissions in WA were due to SSTI, with cellulitis the second most common diagnosis.9 The “Cellulitis at Home or Inpatient in Children from the Emergency Department” (CHOICE) trial in Melbourne reported 700 presentations of cellulitis to the Royal Children’s Hospital over 17 months, with 304 (43%) admissions.20 Our cohort has a higher presentation rate of approximately 56 children per month compared with only 41 per month in Melbourne, while our overall admission rate was slightly lower at 30.7%. In the Northern Territory, 2.3% of all paediatric presentations to the Royal Darwin Hospital ED in 2013 were for cellulitis, making it the eighth most common reason for presentation to the ED.21 Prevention of cellulitis will reduce the burden of hospitalisation on children and families. Cellulitis prevention strategies from current national guidelines include insect repellent, antiseptics for minor trauma22 and possibly vaccination when a GAS vaccine becomes available over the next decade. A recent study investigating the health and economic burden of GAS disease in Australia found that, out of the 24 diseases caused by GAS, cellulitis contributed to over half the total burden in both children and adults, further confirming the need for a GAS vaccine.8

Children with facial cellulitis are more frequently hospitalised than children with cellulitis of other sites. This may be representative of the need for multidisciplinary specialist care and the potential for sight-threatening and life-threatening complications in children with periorbital cellulitis. All but one child with periorbital cellulitis in our study group were admitted for intravenous antibiotics and specialist review (ophthalmology and otolaryngology). This management is supported in the literature, which suggests that multidisciplinary management and early intervention can improve outcomes for children with periorbital cellulitis.23 Canadian data have also demonstrated over-representation of facial cellulitis among paediatric inpatients (26.8%) compared with non-admitted patients (16.3%) with cellulitis.24 Similarly, Canadian ED presentations were also predominantly extremity cellulitis (69.5%), due to insect bite (21.6%) and trauma (20.3%).24

Aboriginal children and children under 5 years were overrepresented in the study group when compared with the WA population. This is consistent with rates of paediatric hospitalisation for SSTI in WA, showing higher admission rates in children under 5 years and Aboriginal children,9 and a known heavy burden of skin infections in Aboriginal children.25 Previous data from Australia demonstrate that Aboriginal children are more likely to be admitted for all health conditions compared with non-Aboriginal children.26 27 The greatest disparity in admission is for infectious diseases, including SSTI.26 27 These high admission rates likely reflect disadvantages relating to the social determinants of health, including poor access to healthcare, overcrowded housing, financial concerns and living in remote locations.26 It is also observed that children living further distances from healthcare centres generally present later and hence have more severe illness.27 As such, it is important to address these factors to reduce the rates of cellulitis and SSTI in Aboriginal children. Vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type B and Streptococcus pneumoniae has been effective in reducing periorbital cellulitis attributable to these pathogens in children below 5 years.28 29 It is likely that a GAS vaccine will have a similarly significant effect for cellulitis attributable to GAS.8

In our study, 3.6% of children had recurrent cellulitis compared with rates of 22%–49% in adults.1 In children, recurrent cellulitis is previously only reported in the context of lymphoedema30 and periorbital cellulitis associated with rhinosinusitis.31 Our study demonstrates a high rate of recurrent cellulitis in children without these risk factors, with MRSA common in recurrent cellulitis. More studies are required to examine the risk factors for recurrent cellulitis in children and inform the use of prophylactic antibiotics and prevention strategies.

The choice and duration of antibiotics was strongly adherent to international guidelines (1–3 days intravenous antibiotics, 5–7 days total duration of antibiotics for moderate–severe cellulitis).17 Children with periorbital cellulitis required longer treatment duration (median 3 days intravenous, median 7 days total), which was also consistent with recommendations (2–3 days intravenous, 7–10 days total).17 Our reported length of stay is comparable to international studies of cellulitis and SSTI.11 24 Most non-admitted patients received oral antibiotics only, which is consistent with recommendations for treatment of mild cellulitis in children.17 The choice of antibiotic was also consistent with the PCH antimicrobial stewardship programme, ChAMP. Further opportunities to improve management of children with cellulitis presenting to hospital include incorporating evidence for early oral treatment using the highly bioavailable regimens of clindamycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.32 Evidence for use of these agents has been synthesised in recent years for children and adults to treat purulent cellutlitis and other uncomplicated SSTI in the outpatient setting. With increasing MRSA prevalence, these MRSA active agents with a strong evidence base are useful for paediatricians to consider.

Pathogen confirmation is difficult in cellulitis. We confirm the futility of blood cultures in cellulitis in immunocompetent children.33 Wound cultures are more helpful, with over 80% of those tested yielding a positive result. Although MSSA was the most commonly cultured organism, it is believed that the role of GAS may be underestimated. One study, using serology in adults with cellulitis, suggested up to 73% of unculturable cellulitis is due to GAS.34

HITH referrals were uncommon despite the availability and accessibility of this programme. The Australian CHOICE trial demonstrated that home parenteral antibiotics are safe, effective and cost-effective for children with moderate to severe cellulitis.23 35 Further efforts to admit children to HITH from ED would improve the quality of life for children with cellulitis, however, it appears that this is not currently common practice. Ibrahim et al found that there are several barriers to clinicians choosing home treatment with intravenous antibiotics including younger age, risk of complications, risk of deteriorating unnoticed and risk of needing to represent to hospital.36 Further education of ED clinicians could reduce these perceived barriers to home intravenous antibiotics. ED clinicians should strongly consider intravenous antibiotics via HITH as a viable and cost-effective option for suitable patients with uncomplicated cellulitis.

Limitations include the retrospective nature of the study, however, this design allowed for initial assessment of the population and the generation of hypotheses for further research. We limited the study population to children with a primary diagnosis of cellulitis presenting to the tertiary centre therefore, it does not include children who presented to the hospital with an alternative diagnosis but were also treated for cellulitis or children managed in primary care. In doing so, the study focuses on tertiary management which provides guidance on treatment for the state. Due to time constraints of the study the data collection for the non-admitted cohort was limited to the proximal 6 months. The data observed represented less than half the expected number of non-admitted cases per annum. The discrepancy likely arises due to the fact that cellulitis is likely more common in the summer months as reported in an adult literature.37 A further limitation is the absence of blinding of the abstractor. While we acknowledge this may introduce bias in retrospective chart reviews, the focus of the study was on epidemiological factors such as age, sex, Aboriginal status and body site affected, which are not susceptible to interpretation bias given they are objective findings. Additionally, the study population represents only moderate to severe cases of cellulitis as milder cases are usually ambulatory.38

Based on our findings, future research should consider the effectiveness of targeted prevention strategies for the high-risk groups identified. Cellulitis is an important cause for young and Aboriginal children to be admitted to hospital in Australia. Prevention of childhood cellulitis requires a multifaceted approach to preventing insect bites, reducing minor trauma and in the future may also include use of a GAS vaccine.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ACB devised the study. ACB and ES planned the project, with input from the other authors. ES and CIM completed the data collection and data analysis. ES led the manuscript writing. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors meet requirements of authorship as per the ICMJE guidelines for authorship.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC Ref 923) with reciprocal approval from the University of Western Australia and the GEKO programme at the Child and Adolescent Health Service (PRN 29036).

References

- 1.Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA 2016;316:325–37. 10.1001/jama.2016.8825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodyear H. Infections and infestations of the skin. Paediatr Child Health 2015;25:72–7. 10.1016/j.paed.2014.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kilburn SA, Featherstone P, Higgins B, et al. Interventions for cellulitis and erysipelas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;6:CD004299. 10.1002/14651858.CD004299.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sartori-Valinotti JC, Newman CC. Diagnosing cellulitis for the Nondermatologist. Hosp Med Clin 2014;3:e202–17. 10.1016/j.ehmc.2013.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunderson CG, Martinello RA. A systematic review of bacteremias in cellulitis and erysipelas. J Infect 2012;64:148–55. 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swartz MN. Cellulitis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2004;350:904–12. 10.1056/NEJMcp031807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10–52. 10.1093/cid/ciu296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon JW, Jack S, Wu Y, et al. An economic case for a vaccine to prevent group A Streptococcus skin infections. Vaccine 2018;36:6968–78. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdalla T, Hendrickx D, Fathima P, et al. Hospital admissions for skin infections among Western Australian children and adolescents from 1996 to 2012. PLoS One 2017;12:e0188803. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larru B, Gerber JS. Cutaneous bacterial infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am 2014;61:457–78. 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez MA, Cruz AT, Kowalkowski MA, et al. Trends in resource utilization for hospitalized children with skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatrics 2013;131:e718–25. 10.1542/peds.2012-0746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu S, Kuo DZ. Hospital charges of potentially preventable pediatric hospitalizations. Acad Pediatr 2012;12:436–44. 10.1016/j.acap.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Child and Adolescent Health Service . Child and adolescent health service 2018-19 annual report. Perth (WA), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Statistical Geographical Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure. Canberra (ACT): Commenwealth of Austrlia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMullan BJ, Andresen D, Blyth CC, et al. Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: systematic review and guidelines. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:e139–52. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30024-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Canberra (ACT): Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Census of population and housing: time series profile, Australia, 2016. Canberra (ACT): Commonwealth of Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim LF, Hopper SM, Babl FE, et al. Who can have parenteral antibiotics at home?: a prospective observational study in children with moderate/severe cellulitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016;35:269–74. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buntsma D, Lithgow A, O'Neill E, et al. Patterns of paediatric emergency presentations to a tertiary referral centre in the Northern Territory. Emerg Med Australas 2017;29:678–85. 10.1111/1742-6723.12853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.RHD Action . National healthy skin guideline: for the prevention, treatment and public health control of impetigo, scabies, crusted scabies and tinea for Indigenous populations and communities in Australia. 1st edn, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy DC, Meghji S, Alfiky M, et al. Paediatric periorbital cellulitis: a 10‐year retrospective case series review. J Paediatr Child Health 2021;57:227–33. 10.1111/jpc.15179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kam AJ, Leal J, Freedman SB. Pediatric cellulitis: success of emergency department short-course intravenous antibiotics. Pediatr Emerg Care 2010;26:171–6. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181d1de08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136789. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falster K, Banks E, Lujic S, et al. Inequalities in pediatric avoidable hospitalizations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in Australia: a population data linkage study. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:169. 10.1186/s12887-016-0706-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dossetor PJ, Martiniuk ALC, Fitzpatrick JP, et al. Pediatric hospital admissions in Indigenous children: a population-based study in remote Australia. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:195. 10.1186/s12887-017-0947-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambati B, et al. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis before and after the advent of Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccination. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1450–3. 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walls A, Pierce M, Krishnan N, et al. Pediatric Head and Neck Complications of Streptococcus pneumoniae before and after PCV7 Vaccination. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;152:336–41. 10.1177/0194599814557777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quéré I, Nagot N, Vikkula M. Incidence of cellulitis among children with primary lymphedema. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2047–8. 10.1056/NEJMc1802399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tzelnick S, Soudry E, Raveh E, et al. Recurrent periorbital cellulitis associated with rhinosinusitis in children: characteristics, course of disease, and management paradigm. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2019;121:26–8. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen AC, Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, et al. Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim (cotrimoxazole) for skin and soft tissue infections including impetigo, cellulitis, and abscess. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4:ofx232. 10.1093/ofid/ofx232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trenchs V, Hernandez-Bou S, Bianchi C, et al. Blood cultures are not useful in the evaluation of children with uncomplicated superficial skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:924–7. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeng A, Beheshti M, Li J, et al. The role of beta-hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis: a prospective investigation. Medicine 2010;89:217–26. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e8d635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim LF, Huang L, Hopper SM, et al. Intravenous ceftriaxone at home versus intravenous flucloxacillin in hospital for children with cellulitis: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:1101–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30288-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ibrahim LF, Babl FE, Hopper SM, et al. Cellulitis: oral versus intravenous and home versus hospital-what makes clinicians decide? Arch Dis Child 2020;105:413.2–5. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-316824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manning L, Cannon J, Dyer J, et al. Seasonal and regional patterns of lower leg cellulitis in Western Australia. Intern Med J 2019;49:212–6. 10.1111/imj.14034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Sullivan C, Baker MG. Skin infections in children in a new Zealand primary care setting: exploring beneath the tip of the iceberg. N Z Med J 2012;125:70–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjpo-2021-001130supp001.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.