SUMMARY

Clinical studies demonstrate associations between circulating levels of the gut microbiota derived metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) and incident stroke risks. However, a causal role of gut microbes in stroke has not yet been demonstrated. Herein we show that gut microbes, through dietary choline and TMAO generation, directly impact cerebral infarct size and adverse outcomes following stroke. Fecal microbial transplantation from low vs high TMAO producing human subjects into germ-free mice shows that both TMAO generation and stroke severity are transmissible traits. Further, employing multiple murine stroke models and transplantation of defined microbial communities with genetically engineered human commensals into germ-free mice, we demonstrate that the microbial cutC gene (an enzymatic source of choline to TMA transformation) is sufficient to transmit TMA/TMAO production, heighten cerebral infarct size and lead to functional impairment. We thus reveal that gut microbiota in general, and the metaorganismal TMAO pathway specifically, directly contributes to stroke severity.

Keywords: trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), gut microbiota, stroke, fecal microbial transplantation, CutC

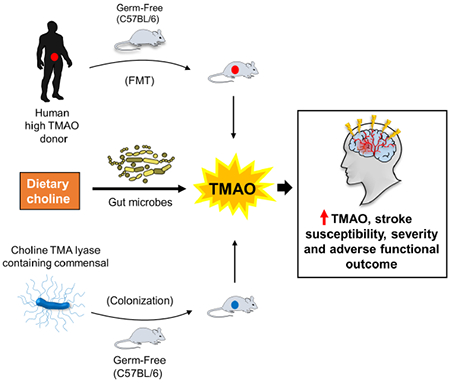

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Zhu et al., demonstrate via gut microbial transplantation studies that stroke severity is transmissible. Specifically, the metaorganismal TMAO pathway was found to impact stroke size and functional impairment in mice. Gut microbial CutC enhanced host TMAO generation, cerebral infarct size, and post-stroke functional deficits.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple clinical studies have reported an association between circulating levels of the gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), risk of stroke and its long-term adverse outcomes (Haghikia et al., 2018; Rexidamu et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2019). However, experimental studies have yet to directly demonstrate a contribution of gut microbes to cerebral vascular diseases including stroke. Transmission of a particular phenotype or disease susceptibility through microbial transplantation from a host to a naïve donor (i.e. fulfilling Koch’s postulate of disease susceptibility) provides strong supportive evidence for a causal contribution of gut microbiota to that phenotype or disease risks (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2018; Routy et al., 2018; Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2016). Our previous studies demonstrated transplantation of microbial communities with high (versus low) capability to generate trimethylamine (TMA), precursor to TMAO, resulted in enhanced atherosclerosis and thrombosis in mice (Gregory et al., 2015; Skye et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2016). Despite the striking clinical associations between plasma TMAO levels and stroke risks, microbial transplantation studies exploring involvement of gut microbiota in stroke have not yet been reported.

Gut microbial production of TMA originates with multiple dietary nutrient precursors, including choline, which is present in both animal and plant foods, and also an abundant constituent within bile. The choline utilization (cut) c gene, which catalyzes choline TMA lyase activity (choline→TMA transformation), is a major microbial choline TMA lyase activity within the human gut microbiome (Craciun and Balskus, 2012). In previous studies employing genetic engineering of human commensals, we directly demonstrated that the presence of a functional gut microbial cutC gene can impact platelet function and thrombosis potential in the host (Skye et al., 2018). Herein we tested whether gut microbiota in general, or either TMAO or a functioning gut microbial cutC gene, can impact stroke severity using multiple rodent models of stroke.

RESULTS

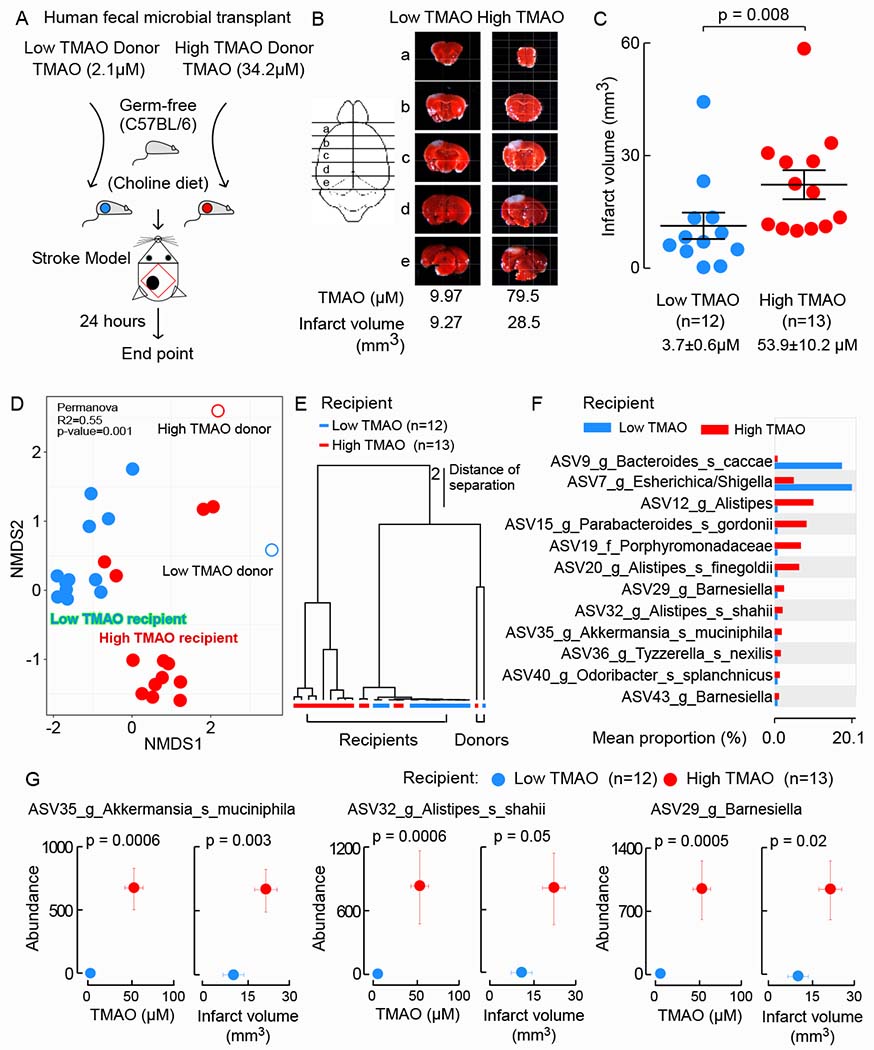

TMAO production and stroke severity are transmissible traits with human fecal microbial transplantation

We previously reported TMAO is associated with incident thrombotic event risk (myocardial infarction or stroke) in subjects (Zhu et al., 2016). Compared with subjects having low plasma TMAO levels (<2.43 μM), fourth quartile subjects (6.18-312 μM) had an adjusted 1.64-fold increase in thrombotic event risk over the ensuing 3 years (Zhu et al., 2016). In another study, microbial transplantation with gut commensals from donors with high vs low circulating TMAO levels following choline challenge was shown to differentially impact recipient mouse platelet reactivity and thrombosis potential following arterial injury (Skye et al., 2018). Because of the clear involvement of platelet reactivity in cerebral vascular diseases including stroke, we initially sought to use a similar human fecal transplantation model to test whether gut microbiota can influence stroke severity. For selection of stable polymicrobial communities to serve as donors, we used human fecal material collected during a recently reported human intervention study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01731236). Two donors were selected - one showing persistently high TMAO (range 34.2-44.3 μM), and the other persistently low TMAO (2.1-3.5μM) on serial plasma TMAO testing (Zhu et al., 2017). Mice were colonized by oral gavage and maintained on the Choline diet. Stroke injury was performed 5 days post fecal transplantation utilizing the murine Rose Bengal cold light stroke model to impart cerebrovascular injury because this model both is reported to initiate platelet activation to generate regional ischemia (Labat-gest and Tomasi, 2013), and can be performed under BSL-2 containment conditions. Figures 1A-C show the overall study design, illustrative coronal cross-sectional images with vital dye staining, and quantification of the extent of infarct volume and plasma TMAO levels observed in recipient mice 24 hours post stroke injury. Notably, germ-free mice colonized by the “high” versus “low” TMAO donor fecal microbial communities showed marked (~15-fold; p<0.0001) differences in circulating plasma TMAO levels (Figure 1C). Moreover, examination of the relationship between systemic TMAO levels and stroke severity among all recipients showed a significant positive correlation (ρ=0.44; P=0.03), with larger infarct volume observed in the high vs. low TMAO recipients (p=0.008; Figure 1B, C).

Figure 1. Stroke severity is a transmissible trait.

(A) Scheme illustrating fecal microbial transplant study design. (B) Representative images of 2mm serial brain slices stained with TTC from a mouse within each group, along with plasma TMAO level and infarct volume in the mouse. (C) Infarct volume was quantified along with plasma TMAO levels 24 hours post-stroke injury. Shown are mean (±SEM) with indicated number of mice. Significance was measured by Mann-Whitney Test. (D) NMDS plots based on the Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity index between donor and recipients groups. Statistical analysis was performed with PERMANOVA. R2 values are noted for comparisons with significant P values and stand for percentage variance explained by the variable of interest. (E) Hierarchical clustering using unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean of human donor and recipient mice. Branch lengths indicate distance of separation based on unweighted UniFrac distance matrices. (F) White’s non-parametric t-test analysis (p value correction for false discovery rate using Benjamini/Hochberg) identified cecal taxa from mouse characteristic in low vs. high TMAO recipient mice. (G) Illustration of three taxa identified in recipient cecal microbes whose abundance are significantly associated with both plasm TMAO levels and infarct volume when grouped as low (n=12) and high (n=13) TMAO recipient mice. Values in both x and y directions are plotted as mean ± SEM. Robust Hotelling T2 test p values are displayed.

We next examined microbial community amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) structure(Callahan et al., 2016) in both human donor fecal samples and the cecal contents of all germ-free recipients via 16S rRNA gene sequencing analyses, followed by differential abundance analysis, as described in Methods. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) demonstrated significant (Permanova < 0.05, R2=0.55) clustering of the low (blue, n=12) and high TMAO (red, n=13) recipients (Figure 1D). hierarchical clustering analyses confirmed the defined separation between the two groups (Figure 1E). Pairwise comparisons (White’s non-parametric t-test, p-value <0.05, false discovery rate= Benjamini–Hochberg) identified ASVs differentially abundant between the low and high TMAO recipient communities (Figure 1F). We further identified cecal bacterial taxa (i.e. ASVs) whose abundances were correlated with plasma TMAO levels or lesion size in recipients. In all, we observed 19 ASVs whose proportions were significantly (FDR adjusted p < 0.01) associated with plasma TMAO levels, and 12 species level ASVs whose proportions were significantly associated with cerebral infarct volume (Figure S1A). Among these, 12 ASVs were significantly associated with both plasma TMAO and lesion size (p-value < 0.005, Benjamini–Flochberg false discovery rate). Notably, in every case, microbial taxa that were positively associated with higher plasma TMAO levels, were also associated with larger lesion size. Interestingly, the abundances of most of the identified bacterial ASVs characteristic of high TMAO recipients (Figure 1F were also positively associated with a more severe stroke phenotype (i.e., larger infarct volume) (Figure 1G and Figure S1B) (See Table S1 for a complete list of all ASVs detected).

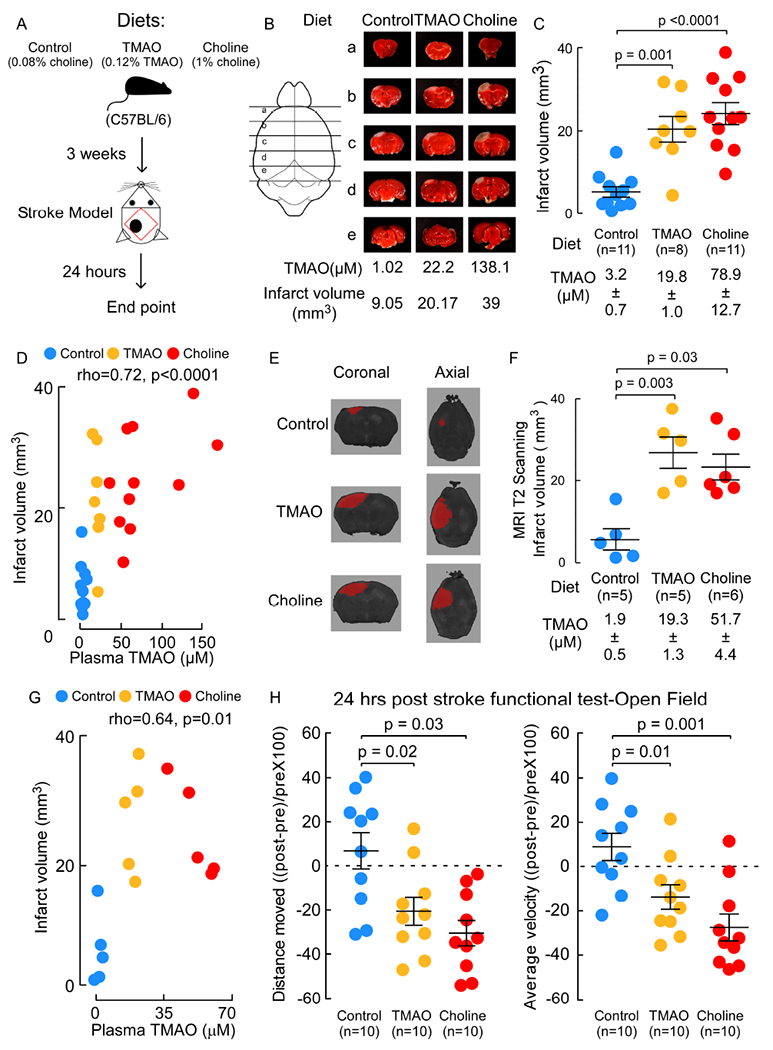

Dietary supplementation with either choline or TMAO increases cerebral infarct size and post stroke motor function deficit

In additional studies we examined whether dietary choline supplementation (which raises plasma TMAO) or direct TMAO feeding impact stroke severity. Conventionally reared C57BL/6 mice were placed on either a control diet (0.08% total choline, confirmed by mass spec), or the same diet supplemented with either TMAO (0.12% w/w) or choline (1% w/w). Animals were maintained on diets for three weeks prior to cerebral injury using the Rose Bengal cold light stroke model. Twenty-four hours after stroke injury plasma TMAO and infarct volume were assessed (Figure 2A). Two methods (independent experiments) were used to detect and quantify cerebral infarct volume by investigators blinded to diet group: (i) triphenyltetrazolium chloride-staining (TTC) with computer image capture; and (ii) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2 scanning. As illustrated in Figure 2B, C, D (TTC), and Figure 2E, F, G (MRI T2), both TMAO and choline supplementation significantly elevated plasma TMAO levels, and in parallel, significantly increased cerebral infarct volume. Further, TMAO levels were significantly correlated with stroke severity (infarct volume) across all dietary groups of mice in both studies (TTC quantification ρ=0.72, P<0.0001, Figure 2D; and MRI T2 quantification ρ=0.64, P=0.01, Figure 2G).

Figure 2. TMAO and choline supplementation increase infarct volume and motor function deficit in a photochemical ischemic stroke injury model.

(A) Scheme illustrating study design. (B-G) Mice were fed the indicated diets for 3 weeks. Both TMAO levels and cerebral infarct volumes were quantified 24 hours post stroke model. (B) Representative images of 2mm serial brain slices stained with TTC. (C) Infarct volume was quantified along with plasma TMAO levels. (D) Correlation (Spearman) between plasma TMAO levels and infarct volume among mice in all groups. (E) Representative images of MRI T2 scanning. (F) Infarct volume was quantified along with plasma TMAO levels. Shown are mean (±SEM) with indicated number of mice. (G) Correlation (Spearman) between plasma TMAO levels and infarct volume among mice in all group. (H) Open field test was used to evaluate motor activity 24 hours post stroke. Total distance moved (left) and Average velocity (right) is plotted as the percent of deduction from pre-stroke for each mouse. Bar and whiskers represent mean (±SEM) for the indicated number of mice. For significance Mann-Whitney Test was used for two group comparisons.

In separate studies, to explore whether the choline-TMAO pathway exacerbates post-stroke functional deficits, animals were maintained on the indicated diets for 3 weeks, and then (continuing with the same diet), various functional analyses were performed (e.g. the open field test (Doeppner et al., 2014) and marble burying (Romano et al., 2017)) before stroke, 24 hours after stroke injury, or over the course of 5 days following stroke, as indicated. Of interest, pre-stroke, the dietary choline-supplemented group showed modest but significant increases in average velocity and total distance moved relative to pre-stroke Control diet and TMAO-supplemented diet groups (Figure S2A). When comparing pre-versus post stroke function across the different dietary groups, both the TMAO and Choline supplemented post-stroke mice reproducibly exhibited significant reductions in all measures of motor activity, in contrast to the post-stroke Control diet group (Figure S2A). Figure 2H illustrates pre-versus post-stroke function within each dietary group of mice and shows that while the Control diet group has no significant change at the time point examined, significant 20–30% reductions post stroke were observed in both Choline and TMAO supplemented groups for the different functional indices monitored (total distance moved, and average velocity during open field testing, all p≤0.03 for all comparisons, Figure 2H). In a separate study, mice were placed on either the Control (n=20) or Choline (n=20) supplemented diets starting 3 weeks prior to stroke, and then marble-burying (30 min) tests were performed before (pre-) or following stroke (1, 3, and 5 days) on a subset of 5 mice in each diet group at each time point (to avoid pre-exposure of marble burying for the mice). While Control diet versus Choline diet groups pre-stroke showed no significant differences, following stroke the Choline diet mice showed significant reductions in the number of marbles buried (Figure S2B).

In a separate set of studies, we examined whether dietary choline enhanced TMAO levels impacts cerebral infarct size in an alternative stroke model, the middle cerebral artery occlusion model (MCAO) (Longa et al., 1989; Rousselet et al., 2012). Mice (both male and female C57BL/6) were placed on the Control diet versus Choline supplemented diet for three weeks, and then middle cerebral artery stroke was induced by monofilament insertion into the internal carotid artery (Figure 3A). Ischemia was confirmed during the surgical procedure by a concurrent drop in cerebral blood flow (≥80% relative to baseline) by real-time laser Doppler flow monitoring. Following (24 hours) stroke injury, both plasma TMAO levels and cerebral infarct volume (% of contralateral) were evaluated (by TTC staining). As shown in Figure 3B and 3C, choline supplementation, which increases plasma TMAO, consistently led to significant increase in cerebral infarct volume. Of note, decreased food intake for the 24 hours post stroke resulted in relatively lower plasma TMAO levels than usual. None-the-less, plasma TMAO levels were highly positively correlated with stroke severity (infarct volume) across all dietary groups of the mice in both sexes (TTC quantification ρ=0.51, P=0.006, Figure 3D). To explore functional recovery for a longer period of time following MCAO, we evaluated open field, Barnes Maze (Jin et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2018) and Y Maze (Jin et al., 2017; Maki et al., 2018) up to 10-15 days post recovery/reperfusion. As shown in Figure 3E, 3F and 3G, compared with Control diet, the Choline supplemented mice showed slower motor function recovery, as evaluated by open field testing, and worse cognitive recovery, as evaluated by both Barnes maze (spatial learning and memory) and Y maze on different sets of animals. No difference was noted between Control vs Choline diet groups pre-stroke injury (data not shown).

Figure 3. Choline diet enhances TMAO generation and stroke severity in the MCAO stroke model.

(A) Scheme illustrating study design. (B) Representative images of 2mm serial brain slices stained with TTC from each group. (C) Both plasma TMAO levels and the infarct volume (% of contralateral) were quantified. Significance was measured by Mann-Whitney Test. (D) Correlation (Spearman) between plasma TMAO levels and infarct volume among mice in all groups. (E-G) C57BL/6 female mice were fed the indicated diet for three weeks, and following MCAO stroke, multiple functional tests were performed at the indicated times post stroke injury. (E) Open field. (F) Barnes maze. (G) Y maze. Data are present as mean (±SEM) for the indicated numbers of mice. Overall significance was determined by non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis (K.W.)) with multiple comparisons. Significance between “Control” and “Choline” groups was determined by Mann-Whitney Test.

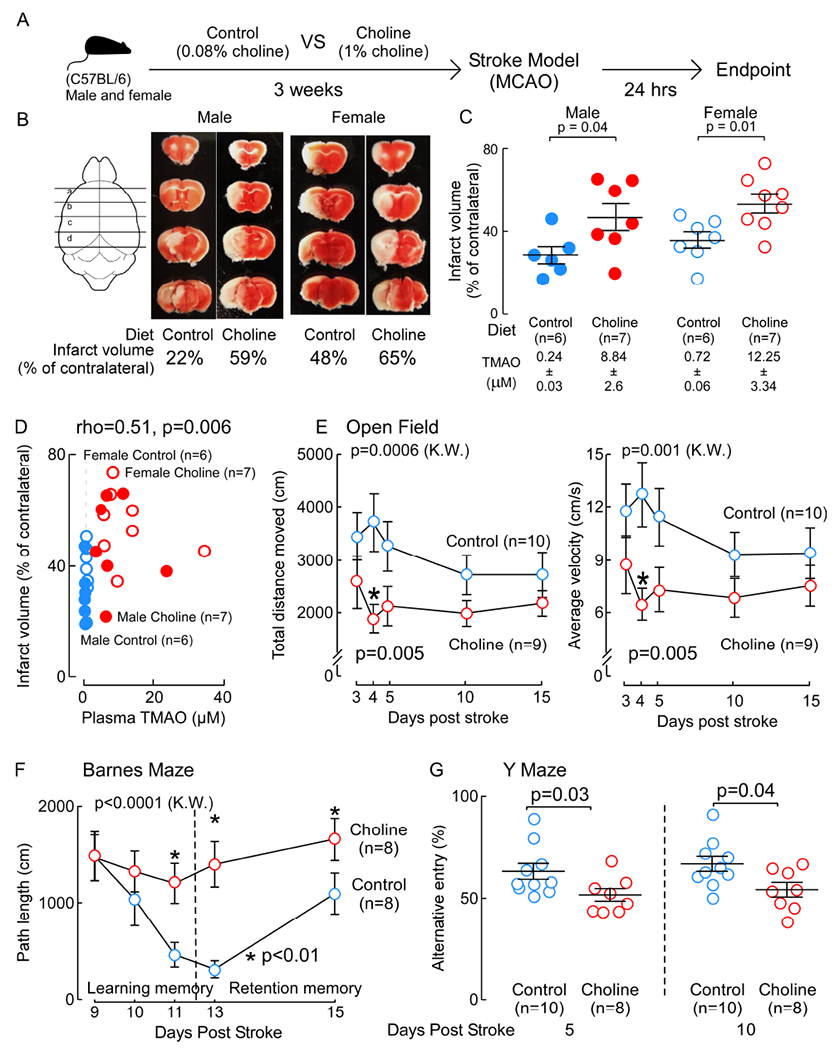

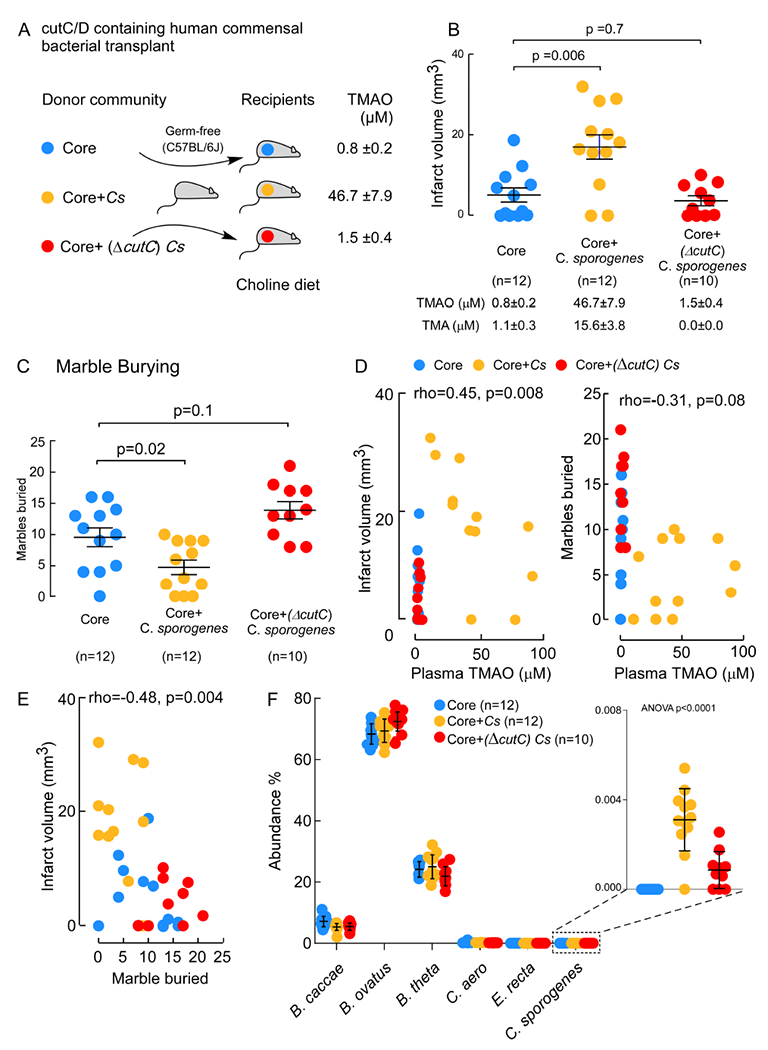

Gut microbial CutC is sufficient to transmit within hosts heightened TMAO level, and stroke severity (cerebral infarct size and functional deficits).

In additional studies, we sought to test whether a functional gut microbial CutC, a major choline TMA lyase (Craciun and Balskus, 2012), can enhance stroke severity in vivo. For these studies (scheme shown Figure 4A) germ-free mice on sterile Choline diet were colonized under gnotobiotic conditions using a genetically tractable synthetic bacterial community representing diverse bacteria phyla dominant in the human gut and confirmed to lack the ability to produce TMA (comprised of Eubacterium rectale, Collineslla aerofaciens, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides ovatus and Bacteroides caccae; aka “Core”) (Romano et al., 2015; Skye et al., 2018). In addition, one subset of the mice were also colonized with Core + wild type Clostridium sporogenes (Cs), which contains a known functional cutC (group referred to as Core+Cs), and another subset were colonized with Core + a Cs mutant engineered to lack a functional CutC enzyme (group referred to as Core+(ΔcutC)Cs). As expected, only germ-free mice colonized with the Core+Cs community displayed elevated plasma TMAO levels, with minimal TMAO observed in the plasma of the germ-free mice colonized with either the Core community alone or Core+(ΔcutC)Cs (Figure 4A, B). Notably, when each group of mice were exposed to stroke injury using the Rose Bengal cold light stroke model, the mice with elevated levels of TMAO (Core+Cs recipients) showed greater stroke severity (Figure 4B). Post-stroke motor activity and general cognitive function was assessed among the recipients of the three communities using the marble burying test, which is well-suited for use on gnotobiotic animals. Animals colonized with the Core+Cs community, which possess the highest TMAO levels, buried significantly fewer marbles than either the Core or Core+(ΔcutC)Cs groups (Figure 4C). Further investigation of the relationship between plasma TMAO and stroke severity across all groups of gnotobiotic recipients demonstrated a significant positive correlation (ρ=0.45; P=0.008; Figure 4D, left). Similarly, TMAO levels were inversely associated with marble buried across all groups of the mice (ρ=−0.31; P=0.08 Figure 4D, right). We also found infarct volume was inversely associated with marbles buried across all groups of the mice (ρ=−0.48; P=0.004; Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Microbial colonization of germ-free mice with a cutC/D containing human commensal is sufficient to transmit enhanced stroke severity.

(A) Scheme illustrating overall study design involving colonization of germ-free mice with the indicated synthetic bacterial communities. After 2 weeks, mice underwent photochemical stroke injury and then TMAO levels and stroke severity were assessed as described under Methods. (B) Infarct volume was quantified following TTC staining, along with plasma TMAO levels. Shown are mean (±SEM) with indicated number of mice. (C) Marble burying test (25 marbles total) by the indicated groups. Shown are mean (±SEM) with indicated number of mice. (D) Correlation (Spearman) between infarct volume and plasma TMAO levels (left panel), or Marble buries (right panel) among mice in all group. (E) Cecal microbial community composition. For significance Mann-Whitney Test was used for two group comparisons, and One-way ANOVA was used for multiple group comparisons.

Cecal microbial composition of recipient mice was assessed as described under Methods. Remarkably, while wild-type C. sporogenes represented only a small fraction of the overall gut community (~0.004%, Figure 4F, right), it none-the-less was sufficient to foster within the host significant increases in circulating TMAO levels, cerebral infarct volume, and post-stroke reduction in functional outcomes relative to mice colonized with either community lacking TMA generation capacity (Core, or Core+(ΔcutC)Cs; Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Collectively, the results presented herein show that gut microbiota in general, and the microbial choline-TMA(O) pathway specifically, impacts both host stroke severity and adverse functional outcomes. Notably, these findings are in keeping with the numerous recent clinical association studies reporting elevated circulating TMAO levels are associated with heightened risk for stroke, and adverse clinical outcomes in subjects with history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke (Haghikia et al., 2018; Nie et al., 2018; Rexidamu et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2019). Similar results were observed using two independent murine stroke models (Rose Bengal cold light and MCAO), in both sexes, and with multiple outcome measures of severity and function (infarct volume, open field mobility, marble burying, Barnes maze and Y maze). It is also of clinical interest that dietary supplementation with choline (and TMAO also) both enhanced cerebral infarct size, and elicited more severe functional deficits following stroke injury. It is notable that both a Western diet and a diet rich in red meat are known to significantly elevate TMAO levels (Koeth et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019), and numerous epidemiological studies have shown a significant association between these and stroke risks (Fung et al., 2004; Jain et al., 2020; Schwingshackl et al., 2019; Spence, 2019; Wolk, 2017). The present studies, when combined with previous clinical studies associating TMAO with stroke risks, suggest dietary interventions in subjects at heightened risk for experiencing stroke merit further investigation.

The present studies add to the growing body of data linking gut microbiota to human health and disease susceptibility (Backhed et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2012; Kasahara and Rey, 2019; Koh et al., 2016; Turnbaugh et al., 2006). Circulating TMAO is generated by microbial metabolism of trimethylamine (TMA) containing precursors, such as phosphatidylcholine and choline, which are commonly enriched in a western diet. To date, various TMA producing enzyme complexes (cutC/D, CntA/B, and Yea W/X) have been identified to metabolize choline, of which cutC/D is the most ubiquitous and well-studies (Craciun and Balskus, 2012; Jameson et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2014). The microbial transplantation studies performed herein reveal that a functional gut microbial cutC significantly increases stroke infarct size, and also worsens functional outcomes following stroke. Moreover, genetic disruption of cutC rescued TMAO-associated stroke severity. It is thus of interest that recent studies have shown that pharmacologically targeting gut microbial cutC and choline TMA lyase activity can reduce thrombosis risk in alternative arterial injury models (Roberts et al., 2018). Further studies are warranted examining the gut microbial TMAO pathway as a potential therapeutic target for the prevention or treatment of stroke. Moreover, the differences in cerebral infarct volumes and functional outcomes noted in low versus high TMAO states is remarkable, and a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms contributing to TMAO driven stroke risks is an area of intense interest.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Weifei Zhu (zhuw@ccf.org)

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents. Clostridium sporogenes ΔcutC was from Michael A. Fischbach, Stanford University (Skye et al., 2018).

Data and Code Availability

Metagenomic data are deposited in MG-RAST-Argonne National Laboratory (http://metaqenomics.anl.gov/) and can be accessed through project name: Stroke and TMAO. Sequencing data sets used for community composition analysis are publicly available through NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) Database under BioProject PRJNA694913. All software and code used to analyze the current study are either open-source or commercially available (all included in KEY RESOURCES TABLE). The data sets generated and or/analyzed during the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author, Weifei Zhu (zhuw@ccf.org).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Eubacterium rectale | ATCC | ATCC33656 |

| Collinsella aerofaciens | ATCC | ATCC25986 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | ATCC | ATCC 29148 |

| Bacteroides ovatus | ATCC | ATCC8483 |

| Bacteroides caccae | ATCC | ATCC43185 |

| Clostridium sporogenes | ATCC | ATCC15579 |

| Clostridium sporogenes ΔcutC | Michael A. Fischbach, Stanford University (Skye et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| High TMAO human fecal sample | Skye et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Low TMAO human fecal sample | Skye et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Rose Bengal | Sigma | Cat # 198250 |

| 2,3,5-Triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride solution ( TTC) | Sigma | Cat# T8877 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Deposited data | ||

| V4–16S rRNA sequences | NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) Database | BioProject PRJNA694913 |

| Metagenomic data | MG-RAST-Argonne National Laboratory (http://metagenomics.anl.gov/) | Stroke and TMAO |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 00664 |

| C57BL/6 (re-Derived Germ-Free) | Cleveland Clinic Gnotobiotics facility | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer set for CutC (Fwd: 5’-CGTGTTCATAAGGAACTTGCAC-3’; | IDT | N/A |

| Primer set for CutC (Rev: 5’-GCTTTTCTCTCGATTATACC-3’) | IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImagePro9 software | Media Cybernetics | https://www.mediacy.com/ |

| Lab Solutions | Shimadzu Scientific Instruments | N/A |

| EthoVision software | Noldus | https://www.noldus.com/ethovision-xt |

| R statistical package | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org |

| Prism (version 8) | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| split_libraries_fastq.py script implemented in QIIME1.9.1 | Caporaso et al., 2010 | http://qiime.org/scripts/split_libraries_fastq.html |

| R package microbiomeSeq | Benjamini, 2010 | http://www.github.com/umerijaz/microbiomeSeq |

| R package phyloseq v 1.19.1 | McMurdie and Holmes, 2013 | https://joey711.github.io/phyloseq/ |

| R package DADA2 | Callahan et al., 2016 | https://benjjneb.github.io/dada2/tutorial.html |

| R package ggplot2 v3.2.0 | Wickham, 2009 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html |

| MIPAV, version 7.3.0. | McAuliffe et al., 2001 | N/A |

| FSL | Smith et al., 2004 | N/A |

| AFNI | Cox, 1996 | N/A |

| COPROseq pipeline | Romano et al., 2017 | https://github.com/DanishKhan14/aligner_RL |

| Other | ||

| Control Diet | Envigo | TD130104 |

| TMAO Diet | Envigo | TD 07865 |

| Choline Diet | Envigo | TD09041 |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2 | ClosTron | pMTL007C-E2 |

| Macherey-Nagel PCR Purification Column | Macherey-Nagel | 740609.250 |

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Human fecal transplant material was from consented human donors collected at the Cleveland Clinic under approved protocols (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01731236, CARNIVAL, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01731236).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Ethical considerations

All animal model studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic. All study protocols and informed consent for human subjects were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Stroke models and diets.

All stroke model studies followed RIGOR guidelines for effective translational stroke research (Fisher et al., 2009; Lapchak et al., 2013; Stroke Therapy Academic Industry, 1999). Two in vivo stroke models were used: a Rose Bengal cold light stroke model, and the Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) model. Before each, mice were fed for the indicated time (typically three weeks) with the indicated diets whose compositions have previously been described (Gregory et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2018 ; Skye et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2016). The base diet used is called the “Control” diet (Tekled Envigo, TD130104), and had chemically defined level of total choline content (0.08%, w/w), which was independently confirmed by mass spectrometry, as previously described (Zhu et al, 2016). Two alternative diets used the same base Control diet supplemented with either 0.12% (w/w) TMAO (called the “TMAO” diet; Tekled Envigo, TD 07865), or the same base Control diet supplemented with an additional 1.00% (w/w) free choline (called the “Choline” diet; Tekled Envigo, TD09041). For most studies, mice were subjected to the Rose Bengal cold light stroke model following established methods (Labat-gest and Tomasi, 2013). Briefly, anesthetized mice received an intraperitoneal injection of Rose Bengal at a dose of 1.5 mg per 10 g body weight. Rose Bengal solution was freshly prepared the day of use at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. The anesthetized mice were then placed in a prone position. To restrict the illuminated area, a skull mask with a hole of 30mm2 was applied. The target brain region − 2 mm lateral and 2 mm posterior to bregma on the left hemisphere – was illuminated for 15 minutes with a cold light source (Schott, KL1500) starting 5 minutes after the Rose Bengal injection. The mice were then placed on a heating pad until they had fully recovered, and then were returned to their home cages.

In alternative studies, a Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) model was performed (Longa et al., 1989). Briefly, mice were under anesthesia, and body temperature was monitored and maintained at 36.5–37.5°C. After making an incision in the midline skin, the left common carotid artery, external carotid artery (ECA), and internal carotid artery (ICA) were exposed. A MCAO suture (Doccol Corporation, Sharon, MA, USA) was then inserted into the right ICA through the broken end of the ECA to block the origin of the MCA. Induction of ischemia was confirmed by a concurrent drop in cerebral blood flow value as a percentage (≥80%) relative to baseline by laser Doppler flowmetry. Cerebral ischemia through the intraluminal suture was maintained for 90-120 min, followed by removal of the suture and reperfusion. At 24 h hours after MCAO, the brains were dissected for TTC staining. Tissues were collected and immediately frozen at −80°C.

Human fecal microbiota collection

Stool samples from consented human donors were collected at the Cleveland Clinic under approved protocols (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01731236) and stored for future studies as fecal slurries (0.15g/ml) in 10% glycerol at −80°C. The samples were prepared in aerobic environment (biosafety hood). Two human donors stool samples were used in this study: one persistently high TMAO producer and one low TMAO producer, according to multiple blood draws on multiple different days.

METHOD DETAILS

Human fecal microbial transplantation.

Germ-free C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks were provided from Cleveland Clinic Gnotobiotics facility and were maintained in sterile Allentown Sealed Positive Pressure cages for the duration of the experiment. Mice were colonized with 200μl of a 5× dilution of the above stock by oral gavage. Starting on the morning of fecal transplantation germ-free mice were fed sterile (autoclaved) Choline diet (Tekled: Envigo TD.09041). Following colonization (5 days), the Rose Bengal cold light stroke model was performed. Infarct volume in mice 24 hours post stroke injury was assessed. We chose the timing for our studies (5 days post fecal microbial transplantation) based on several reasons. Others have shown fecal microbial profiles largely indistinguishable from donors with similar time-lines post microbial transplantation (Ericsson et al., 2017; Goodman et al., 2011). Moreover, in previous studies using the same design (5days post FMT on a high choline diet from high vs low TMAO donor) we observed significant differences in both cecal microbial choline TMA lyase enzyme activity (p=0.006), and circulating TMAO levels (P<0.0001) in recipient mice of “high” versus “low” TMAO donor fecal material (Skye, et al., 2018).

V4-16S rDNA gene sequencing.

The 16S rRNA V4 region was amplified and sequenced using protocols mentioned in the Earth Microbiome Project (EMP) (Gilbert et al., 2014). Raw 16S amplicon sequence and metadata were demultiplexed using split_libraries_fastq.py script implemented in QIIME1.9.1 (Caporaso et al., 2010). The demultiplexed fastq file was split into sample specific fastq files using split_sequence_file_on_sample_ids.py script from Qiime1.9.1 (Caporaso et al., 2010). Individual fastq files without non-biological nucleotides were processed using Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm (DADA) pipeline (Callahan et al., 2016).

Microbial community analysis.

Nonmetric-multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix (Beals, 1984) between groups and visualized with the ggplot2 package in R (Wickham, 2009). NMDS clustering was based on the dissimilarity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index) between the donor and recipient groups (high vs low TMAO). Statistical analysis was performed with PERMANOVA using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure, to control the false discovery rate (Benjamini, 2010). P-values are labeled in plots. We performed an ANOVA among sample categories while measuring the α-diversity of measures using the plot_anova_diversity function in the microbiomeSeq package (http://www.qithub.com/umeriiaz/microbiomeSeq). Two group analyses were performed with White’s non-parametric t-test (White et al., 2009), using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (Benjamini, 2010). All graphs and analyses were performed in R using the phyloseq package v 1.19.1 and the associated dependencies (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). Comparison of specific microbial genera abundance with TMAO or other phenotypes were determined by “lm” function implemented in R using “broom” and “dplyr” packages. R2 and corrected p-values are noted for comparisons with significant p-values and stand for percentage variance explained by the variable of interest.

Hierarchical clustering by unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) was performed using the unweighted UniFrac distance matrices in QIIME. Heatmaps containing OTUs at 0.005% relative abundance by sample were organized by row using PCoA with unweighted UniFrac distance measure. All graphs and analyses were performed in R using the phyloseq package v 1.19.1 and the associated dependencies (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). Abundances of specific microbial genera with TMAO levels or lesion size were compared using unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction. Heatmaps were generated with the R statistical package (version 3.6.3). False discovery rates (FDRs) of the multiple comparisons were estimated for each taxon based on the p values resulting from Spearman correlation estimates.

Bacterial communities resulting from inoculation of germ-free animals with synthetic communities were analyzed using previously reported methods (Romano et al., 2017).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition and analysis.

MRI acquisitions were carried out postmortem on a 7 T MRI scanner (Bruker BioSpec 70/20 MRI; Billerica, MA) using an 86 mm linear coil coupled with a 4-channel proton receive-only mouse brain array coil (Bruker Biospin GMBH). The imaging protocol consisted of a three-dimensional high resolution T2-weighted sequence (TE = 48 ms, TR=1980 ms, RARE factor = 10, SA = 1, FOV = 18 x 18 x16 mm3, matrix size = 256 × 129 x 114 pixels and resolution = 0.07 x 0.14 x 0.14 mm3).

The T2w MRI image set for each animal was initially pre-processed for bias field correction (Tustison et al., 2010) and extra-cranial material was removed to segment the brain volume. The infarct volume was then segmented using a level set algorithm in MIPAV (McAuliffe et al., 2001), version 7.3.0. All image processing and volume calculations were performed using FSL (Smith et al., 2004) and AFNI (Cox, 1996) tools.

Behavior tests.

Four behavior tests were performed.

Open field:

The mouse was placed in the open field box (40x50x60cm) and allowed to behave freely for 10 min. All test sessions were video recorded for data archiving. After the test session, the open field box was cleaned with 70% ethanol and dried to minimize any olfactory cues before the next mouse was tested. Distance traveled and velocity were analyzed by the EthoVision software.

Marble-burying test:

Each mouse was individually placed in a plastic cage (18x32x14 cm3) containing 5 cm thick coating of Sani-chip contact animal bedding (Envigo (Teklad) 6324). Twenty five small glass marbles (diameter 10–12 mm) were arranged on the bedding evenly spaced in five rows. Visual barriers were placed between cages. Each mouse was placed in the prepared cage and left undisturbed for 30 min, after which point the mouse was carefully removed as to not further disturb the marbles. A marble at least two thirds (2/3) covered by bedding was considered “buried”. Three independent investigators blind to treatment determined the number of marbles buried. For germ-free mouse experiments, all supplies were autoclaved before use and carried out in a biological safety cabinet.

Barnes Maze test:

Barnes Maze- Mice special learning and retention memory were assessed by Barnes maze post-stroke. The mice were started to train on the Barnes maze 9th-day post-stroke. The Barnes maze with forty holes including the escape hole was used for the study. Extra-maze cues all around the room and intramaze cues were placed as reference cues to help mice to locate the escape hole. Bright overhead light on the Barnes maze was used as an adverse stimulus to motivate mice to locate the escape hole. To assess the learning memory, mice were trained for three consecutive days to locate the escape hole. During the learning phase, mice went through two five-minute sessions at the sixty-minute interval. Mice were allowed to locate the escape hole during the first session and if mice fail to locate the escape hole within five-minutes, were gently guide to find the escape hole and left for two-minutes in the hole. During the second session, mice were tracked by EthoVision software to record the total distance travel before finding the escape hole within five-minutes and were allowed to stay in the hole for two-minutes. Retention memory was assessed after one and three days following the learning memory test.

Y-Maze test:

To assess the spontaneous alternation mice were subjected to Y-maze 5th and 10th days post-stroke. Mice were placed into one arm of the Y-maze facing the center and tracked for 10-minutes using EthoVision software. The videos of the session were analyzed and scored manually. The mouse were considered entering to the arm when all four-paws of the animal cross the threshold set in the central zone and the mouse snout wass in the direction toward the arm end.

Construction of cutC directly insertional mutants that are enzymatically null.

Disruptions of the cutC gene in Clostridium sporogenes (CLOSPO_02864) was accomplished using the ClosTron mutagenesis procedure as previously reported (Williams, 2011; Heap et al., 2010; Skye et al., 2018). The cutC targeting DNA sequence was cloned into the shuttle plasmid pMTL007C-E2 to make the retargeted vector pMTL007C-E2::Csp-cutC. The retargeted pMTL007C-E2::Csp-cutC plasmid was conjugated into C. sporogenes and plated onto TYG agar plates supplemented with D-cycloserine (250μg/ml) and thiamphenicol (15μg/ml) (Williams, 2011). Antibiotic resistant colonies were verified by diagnostic PCR as containing the plasmid of interest. PCR positive colonies were spread onto TYG agar plates supplemented with erythromycin (5μg/ml_) prior to selection again on TYG plates supplemented with D-cycloserine and erythromycin. Screening for intron insertion was performed after bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using the Zymo Fungal/Bacterial DNA Extraction Kit. Extracted DNA was used for diagnostic PCR using the primer set (Fwd: 5’-CGTGTTCATAAGGAACTTGCAC-3’; Rev: 5’-GCTTTTCTCTCGATTATACC-3’), which results in a ~1000 bp product for the wild-type cutC DNA sequence and ~3200 bp product for the directed insertional mutant containing the intron. PCR verified directional insertion clones were confirmed to not produce TMA by stable isotope dilution LC/MS/MS analyses (Koeth et al., 2014).

Gnotobiotic mouse colonization.

Microbial strains used to colonize mice were grown as monocultures on Mega Medium agar plates anaerobically for 24-48h at 37°C. Single colonies were then inoculated into 3 ml of Mega Medium and grown anaerobically at 37°C until late log phase. Strains belonging to the same treatment group were combined in an equal volume ratio in a Hungate tube. Germ-free, C57BL/6 8–10-week-old mice were inoculated by oral gavage with 200μl of mixed bacterial culture inside the gnotobiotic isolator or in a biological safety cabinet. At the time of sacrifice tissues were immediately collected, frozen, and stored at −80°C.

Community profiling by sequencing.

Bacterial communities resulting from inoculation of germ-free animals were analyzed according to published methods(McNulty et al., 2011; Romano et al., 2017 ; Romano et al., 2015). Briefly, DNA was extracted from cecal samples using mechanical disruption. Total bacterial gDNA was sonicated in a water bath sonicator then cleaned and concentrated using a Macherey-Nagel PCR Purification Column before further processing. Concentrated DNA was blunted and poly-A tailed. A-tailed molecules were then ligated to the specified barcoded Illumina adapter sequences. Adapter bound DNA was size-selected on a 2% agarose gel by electrophoresis. Purified fragments of the desired size were PCR amplified and again purified over a Macherey-Nagel PCR Purification Column. Purified PCR products were given to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center for quality assurance and library sequencing following the manufacturer’s protocols for the Illumina MiSeq platform. Raw FASTQ files were provide by the Biotechnology Center for analysis after sequencing. Sequences were demultiplexed by 7bp barcodes present in the adapters. Barcodes required an exact match to be included in community analysis (sequences without a barcode match were excluded from the analysis). Sequences were aligned to the reference genomes of the 6 bacteria included in this study using Bowtie as a part of the COPROseq pipeline (https://github.com/DanishKhan14/aligner_RL). Only reads which mapped uniquely to the reference genomes were used for abundance analysis. Raw counts were normalized based on the genome size of each organism included in the analysis to account for genome size bias. The proportional representation of each organism in the analysis was determined by dividing its normalized counts within a sample by the total normalized counts for all organisms within that sample. Organisms used in the analysis include: Bacteroides_caccae_ATCC_43185, Bacteroides_ovatus_ATCC_8483, Bacteroides_thetaiotaomicron_VPI-5482, Collinsella_aerofaciens_ATCC_25986, Eubacterium_rectale_ATCC_33656, and Clostridium_sporogenes_ATCC_15579.

Mass spectrometry quantification of plasma analytes.

Stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography with on-line tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) was used for quantification of plasma TMA and TMAO, as well as the content of free ant total choline of all chemically defined diets, as previously described (Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous variables between the study groups. Post hoc comparisons was made using Mann-Whitney Test. Spearman was used to measure correlation. Statistical analysis was performed with PERMANOVA in NMDS plots. Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean was sued in Hierarchical clustering. White’s non-parametric t-test analysis (p value correction for false discovery rate using Benjamini/Hochberg) was used to identify cecal taxa from mouse characteristic in different groups. Robust Hotelling T2 test was used to identify in microbes whose abundance are significantly associated with different phenotypes. More significance information can be found in Figure Legend.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Gut microbial transplantation studies show stroke severity is a transmissible trait

The metaorganismal TMAO pathway impacts stroke size and functional impairment

Gut microbial CutC enhances host TMAO, cerebral infarct size and functional deficits

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center DNA Sequencing Facility for providing sequencing access and support services as well as Dr. Kazuyuki Kasahara for assistance in library preparation. The authors thank Cleveland clinic Small Animal Imaging Core, which was supported by the Ohio Third Frontier IPP TECH 150141 Grant (to B. D.T.). We thank Prasenjit Saha for the assistance in graphic abstract drawing. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL150537 to W.Z., P01 HL147823 and R01 HL103866 to S.L.H.) and the Foundation Leducq. K.A.R. was supported in part by NIH/NHLBI training grant HL134622.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

S.L.H. reports being named as co-inventor on pending and issued patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics and therapeutics, being a paid consultant for Procter & Gamble, having received research funds from Procter & Gamble and Roche Diagnostics, and being eligible to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics or therapeutics from Cleveland HeartLab, a subsidiary of Quest Diagnostics, and Procter & Gamble. The other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, and Gordon JI (2004). The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 15718–15723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals EW (1984). Advances in Ecological Research, Vol 14 (Cambridge: Academic Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y (2010). Discovering the false discovery rate. 72, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, and Holmes SP (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature methods 13, 581–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods 7, 335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methe BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, et al. (2012). Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature 488, 621–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW (1996). AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research, an international journal 29, 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S, and Balskus EP (2012). Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 21307–21312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doeppner TR, Kaltwasser B, Bähr M, and Hermann DM (2014). Effects of neural progenitor cells on post-stroke neurological impairment-a detailed and comprehensive analysis of behavioral tests. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 8, 338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson AC, Personett AR, Turner G, Dorfmeyer RA, and Franklin CL (2017). Variable Colonization after Reciprocal Fecal Microbiota Transfer between Mice with Low and High Richness Microbiota. Front Microbiol 8, 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, Lo EH, and Group S (2009). Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke 40, 2244–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung TT, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rexrode KM, Willett WC, and Hu FB (2004). Prospective study of major dietary patterns and stroke risk in women. Stroke 35, 2014–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Jansson JK, and Knight R (2014). The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC biology 12, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, Prieto PA, Vicente D, Hoffman K, Wei SC, et al. (2018). Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Kallstrom G, Faith JJ, Reyes A, Moore A, Dantas G, and Gordon JI (2011). Extensive personal human gut microbiota culture collections characterized and manipulated in gnotobiotic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 6252–6257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JC, Buffa JA, Org E, Wang Z, Levison BS, Zhu W, Wagner MA, Bennett BJ, Li L, DiDonato JA, et al. (2015). Transmission of atherosclerosis susceptibility with gut microbial transplantation. J Biol Chem 290(9), 5647–5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghikia A, Li XS, Liman TG, Bledau N, Schmidt D, Zimmermann F, Krankel N, Widera C, Sonnenschein K, Haghikia A, et al. (2018a). Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine N-Oxide Predicts Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Stroke and Is Related to Proinflammatory Monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol 38, 2225–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap JT, Kuehne SA, Ehsaan M, Cartman ST, Cooksley CM, Scott JC, and Minton NP (2010). The ClosTron: Mutagenesis in Clostridium refined and streamlined. Journal of microbiological methods 80, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P, Suemoto CK, Rexrode K, Manson JE, Robins JM, Hernan MA, and Danaei G (2020). Hypothetical Lifestyle Strategies in Middle-Aged Women and the Long-Term Risk of Stroke. Stroke 51, 1381–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson E, Fu T, Brown IR, Paszkiewicz K, Purdy KJ, Frank S, and Chen Y (2016). Anaerobic choline metabolism in microcompartments promotes growth and swarming of Proteus mirabilis. Environmental microbiology 18, 2886–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Barnett A, Zhang Y, Yu X, and Luo Y (2017). Poststroke Sonic Hedgehog Agonist Treatment Improves Functional Recovery by Enhancing Neurogenesis and Angiogenesis. Stroke 48, 1636–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara K, and Rey FE (2019). The emerging role of gut microbial metabolism on cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Microbiol 50, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeth RA, Levison BS, Culley MK, Buffa JA, Wang Z, Gregory JC, Org E, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, et al. (2014). γ-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell metabolism 20, 799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, et al. ( 2013). Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19(5), 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, and Backhed F (2016). From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 165, 1332–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labat-gest V, and Tomasi S (2013). Photothrombotic ischemia: a minimally invasive and reproducible photochemical cortical lesion model for mouse stroke studies. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapchak PA, Zhang JH, and Noble-Haeusslein LJ (2013). RIGOR guidelines: escalating STAIR and STEPS for effective translational research. Transl Stroke Res 4, 279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Shan W, and Zuo Z (2018). Perioperative use of cefazolin ameliorates postoperative cognitive dysfunction but induces gut inflammation in mice. J Neuroinflammation 15, 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, and Cummins R (1989). Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharshak N, Packey CD, Ellermann M, Manick S, Siddle JP, Huh EY, Plevy S, Sartor RB, and Carroll IM ( 2013). Altered enteric microbiota ecology in interleukin 10-deficient mice during development and progression of intestinal inflammation. Gut Microbes 4(4):, 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki T, Morancho A, Martinez-San Segundo P, Hayakawa K, Takase H, Liang AC, Gabriel-Salazar M, Medina-Gutierrez E, Washida K, Montaner J, et al. (2018). Endothelial Progenitor Cell Secretome and Oligovascular Repair in a Mouse Model of Prolonged Cerebral Hypoperfusion. Stroke 49, 1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe MJ, Lalonde FM, McGarry D, Gandler W, Csaky K, and Trus BL (2001). Medical Image Processing, Analysis and Visualization in clinical research. Paper presented at: Proceedings 14th IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems CBMS 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie PJ, and Holmes S (2013). phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PloS one 8, e61217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty NP, Yatsunenko T, Hsiao A, Faith JJ, Muegge BD, Goodman AL, Henrissat B, Oozeer R, Cools-Portier S, Gobert G, et al. (2011). The impact of a consortium of fermented milk strains on the gut microbiome of gnotobiotic mice and monozygotic twins. Sci Transl Med 3, 106ra106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Xie L, Zhao BX, Li Y, Qiu B, Zhu F, Li GF, He M, Wang Y, Wang B, et al. (2018). Serum Trimethylamine N-Oxide Concentration Is Positively Associated With First Stroke in Hypertensive Patients. Stroke 49, 2021–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexidamu M, Li H, Jin H, and Huang J (2019). Serum levels of Trimethylamine-N-oxide in patients with ischemic stroke. Biosci Rep 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, Hurd AG, Wang Z, Zhu W, Gupta N, Skye SM, Cody DB, Levison BS, et al. (2018). Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med 24(9):, 1407–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KA, Martinez-Del Campo A, Kasahara K, Chittim CL, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, Balskus EP, and Rey FE (2017). Metabolic, Epigenetic, and Transgenerational Effects of Gut Bacterial Choline Consumption. Cell host & microbe 22, 279–290.e277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KA, Martinez-Del Campo A, Kasahara K, Chittim CL, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, Balskus EP, and Rey FE (2017). Metabolic, Epigenetic, and Transgenerational Effects of Gut Bacterial Choline Consumption. Cell Host Microbe 22(3):, 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KA, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, and Rey FE (2015). Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. mBio 6, e02481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselet E, Kriz J, and Seidah NG (2012). Mouse model of intraluminal MCAO: cerebral infarct evaluation by cresyl violet staining. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillere R, Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M, Rauber C, Roberti MP, et al. (2018). Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Okun JG, Schwarz KV, Hauke J, Zorn M, Nurnberg C, Ungerer M, Ringleb PA, and Mundiyanapurath S (2020). Trimethylamine-N-oxide is elevated in the acute phase after ischaemic stroke and decreases within the first days. Eur J Neurol 27, 1596–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwingshackl L, Knuppel S, Michels N, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Iqbal K, De Henauw S, Boeing H, and Devleesschauwer B (2019). Intake of 12 food groups and disability-adjusted life years from coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer in 16 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol 34, 765–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skye SM, Zhu W, Romano KA, Guo CJ, Wang Z, Jia X, Kirsop J, Haag B, Lang JM, DiDonato JA, et al. (2018). Microbial Transplantation With Human Gut Commensals Containing CutC Is Sufficient to Transmit Enhanced Platelet Reactivity and Thrombosis Potential. Circulation Research 123, 1164–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, et al. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 23 Suppl 1, S208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JD (2019). Nutrition and Risk of Stroke. Nutrients 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroke Therapy Academic Industry, R. (1999). Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke 30, 2752–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, and Gordon JI (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444(7122), 1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, Zheng Y, Egan A, Yushkevich PA, and Gee JC (2010). N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 29, 1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Bergeron N, Levison BS, Li XS, Chiu S, Jia X, Koeth RA, Li L, Wu Y, Tang WHW, et al. (2019). Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur Heart J 40, 583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, et al. (2011). Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472, 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Levison BS, Hazen JE, Donahue L, Li XM, and Hazen SL (2014). Measurement of trimethylamine-N-oxide by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical biochemistry 455, 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JR, Nagarajan N, and Pop M (2009). Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS computational biology 5, e1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2009). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Verlag New York: Springer; ). [Google Scholar]

- Williams James A. (2011). Strain Engineering: Methods and Protocols (Totowa New Jersey: Humana; ). [Google Scholar]

- Wolk A (2017). Potential health hazards of eating red meat. J Intern Med 281, 106–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Q, Wang X, Chen C, Tang Y, Wang Y, Tian J, Zhao Y, and Liu X (2019). Prognostic Value of Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide Levels in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol 39, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E, Buffa JA, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M, et al. ( 2016). Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 165(1), 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Wang Z, Tang WHW, and Hazen SL (2017). Gut Microbe-Generated Trimethylamine N-Oxide From Dietary Choline Is Prothrombotic in Subjects. Circulation 135, 1671–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Jameson E, Crosatti M, Schafer H, Rajakumar K, Bugg TD, and Chen Y (2014). Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 4268–4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Metagenomic data are deposited in MG-RAST-Argonne National Laboratory (http://metaqenomics.anl.gov/) and can be accessed through project name: Stroke and TMAO. Sequencing data sets used for community composition analysis are publicly available through NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) Database under BioProject PRJNA694913. All software and code used to analyze the current study are either open-source or commercially available (all included in KEY RESOURCES TABLE). The data sets generated and or/analyzed during the current study are available upon request from the corresponding author, Weifei Zhu (zhuw@ccf.org).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Eubacterium rectale | ATCC | ATCC33656 |

| Collinsella aerofaciens | ATCC | ATCC25986 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | ATCC | ATCC 29148 |

| Bacteroides ovatus | ATCC | ATCC8483 |

| Bacteroides caccae | ATCC | ATCC43185 |

| Clostridium sporogenes | ATCC | ATCC15579 |

| Clostridium sporogenes ΔcutC | Michael A. Fischbach, Stanford University (Skye et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| High TMAO human fecal sample | Skye et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Low TMAO human fecal sample | Skye et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Rose Bengal | Sigma | Cat # 198250 |

| 2,3,5-Triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride solution ( TTC) | Sigma | Cat# T8877 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Deposited data | ||

| V4–16S rRNA sequences | NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) Database | BioProject PRJNA694913 |

| Metagenomic data | MG-RAST-Argonne National Laboratory (http://metagenomics.anl.gov/) | Stroke and TMAO |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 00664 |

| C57BL/6 (re-Derived Germ-Free) | Cleveland Clinic Gnotobiotics facility | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer set for CutC (Fwd: 5’-CGTGTTCATAAGGAACTTGCAC-3’; | IDT | N/A |

| Primer set for CutC (Rev: 5’-GCTTTTCTCTCGATTATACC-3’) | IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImagePro9 software | Media Cybernetics | https://www.mediacy.com/ |

| Lab Solutions | Shimadzu Scientific Instruments | N/A |

| EthoVision software | Noldus | https://www.noldus.com/ethovision-xt |

| R statistical package | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org |

| Prism (version 8) | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| split_libraries_fastq.py script implemented in QIIME1.9.1 | Caporaso et al., 2010 | http://qiime.org/scripts/split_libraries_fastq.html |

| R package microbiomeSeq | Benjamini, 2010 | http://www.github.com/umerijaz/microbiomeSeq |

| R package phyloseq v 1.19.1 | McMurdie and Holmes, 2013 | https://joey711.github.io/phyloseq/ |

| R package DADA2 | Callahan et al., 2016 | https://benjjneb.github.io/dada2/tutorial.html |

| R package ggplot2 v3.2.0 | Wickham, 2009 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html |

| MIPAV, version 7.3.0. | McAuliffe et al., 2001 | N/A |

| FSL | Smith et al., 2004 | N/A |

| AFNI | Cox, 1996 | N/A |

| COPROseq pipeline | Romano et al., 2017 | https://github.com/DanishKhan14/aligner_RL |

| Other | ||

| Control Diet | Envigo | TD130104 |

| TMAO Diet | Envigo | TD 07865 |

| Choline Diet | Envigo | TD09041 |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2 | ClosTron | pMTL007C-E2 |

| Macherey-Nagel PCR Purification Column | Macherey-Nagel | 740609.250 |