Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in pregnancy induces a robust maternal immune response, with transplacental antibody transfer detectable in cord blood as early as 16 days after the first dose.

INTRODUCTION

Pregnant women were excluded from initial clinical trials for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines1,2; thus, the understanding of the immunologic response to vaccination in pregnancy and the transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies is limited.3,4

METHODS

Between January 28, 2021, and March 31, 2021, we studied 122 pregnant women with cord blood available at the time of birth at a single academic medical center. Women who self-reported receipt of one or both doses of a messenger RNA (mRNA)–based COVID-19 vaccine and gave birth to a singleton neonate (gestational age between 35 0/7 and 41 2/7 weeks) were included in the study. Semi-quantitative testing for antibodies against S-receptor binding domain5,6 was performed on leftover clinical sera of maternal peripheral blood to identify antibodies mounted against the vaccine and on leftover clinical sera of cord blood to study passive immunity. Only women who tested negative for antibodies against the nucleocapsid protein antigen7 were included to ensure antibodies were not the result of past severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The relationship between immunoglobin (Ig)G antibody levels and time was studied using analysis of variance. The relationship between maternal and cord blood IgG levels and between IgG placental transfer (neonatal/maternal) ratio and time was studied using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression. The study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

By the time of delivery, 55 pregnant women had received one dose of an mRNA vaccine and 67 had received both vaccine doses. Eighty-five women received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, and 37 women received the Moderna vaccine. All women tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on nasopharyngeal swabs, and all women and neonates were asymptomatic at birth and until time of discharge.

Eighty-seven pregnant women tested at birth produced an IgG response, 19 women produced both an IgM and IgG response, and 16 women had no detectable antibody response, the latter of whom were within 4 weeks of vaccine dose 1 (Fig. 1A). As the number of weeks elapsed, the number of women who mounted an antibody response and who conferred passive immunity to their neonates increased (Fig. 1A). All women and cord blood samples, except for one, had detectable IgG antibodies by 4 weeks after vaccine dose 1 (Fig. 1A). The one dyad with no transfer of antibodies to the neonate was 10 weeks from dose 1 and 6 weeks from dose 2. The earliest detection of antibodies in women occurred 5 days post–vaccine dose 1, and the earliest detection of antibodies in cord blood occurred 16 days post–vaccine dose 1. Forty-four percent (24/55) of cord blood samples from women who received only one vaccine dose had detectable IgG, whereas 99% (65/67) of cord blood samples from women who received both vaccine doses had detectable IgG.

Fig. 1. Maternal antibody response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mRNA vaccination. A. Number of women who produced no antibody response, produced an antibody response but did not demonstrate passive immunity to their neonates, or produced an antibody response and also demonstrated passive immunity to their neonates. Time 0 is day of maternal vaccination dose 1. The earliest detection of antibodies in neonates (passive immunity) was at 16 days post–maternal dose 1. The one mother–neonate dyad with no transfer of antibodies to the neonate was at 10.14 weeks from dose 1 and 6 weeks from dose 2. B. Maternal immunoglobulin (Ig)G levels vs weeks elapsed since maternal vaccination dose 1 for women who received only one dose of the vaccine (n=55). Time point 0 is day of vaccination dose 1. C. Maternal IgG levels vs weeks elapsed since maternal vaccination dose 2 for women who received both doses of the vaccine (n=67). Time point 0 is day of vaccination dose 2. All positive serology cutoffs were 1 (dashed line). The relationship between IgG antibody levels and time was studied using analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc. Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.6.3, RStudio 1.1.463. ns, not significant.

Prabhu. COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2021.

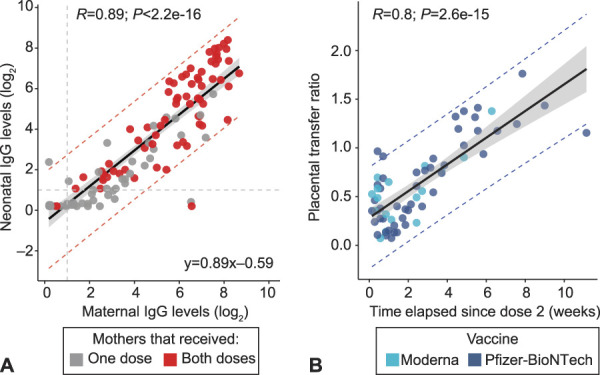

Maternal IgG levels were significantly higher, week by week, starting 2 weeks after the first vaccine dose (P=.005 and .019, respectively), as well as between the first and second weeks after the second vaccine dose (P=2e-07) (Fig. 1B and C). Maternal IgG levels were linearly associated with cord blood IgG levels (R=0.89, P<2.2e-16) (Fig. 2A). The placental transfer ratio correlated with the number of weeks elapsed since maternal vaccine dose 2 (R=0.8, P=2.6e-15) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Neonatal antibody response to maternal coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mRNA vaccination. A. Cord blood immunoglobulin (Ig)G levels vs maternal IgG levels. Grey dots represent neonates born to mothers who received only one dose of the vaccine. All positive serology cutoffs were 1 (dashed gray line). The relationship between maternal and neonatal IgG levels was studied using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression on log2-scaled serologic values. CIs are represented by shaded region (95% CI 0.80–0.97). Lower and upper prediction intervals are indicated with dotted red lines. B. Placental transfer ratio (neonatal IgG/maternal IgG) vs weeks elapsed since maternal vaccination dose 2 for 65 dyads containing mothers who received both vaccine doses. Time point 0 is day of vaccine dose 2. The relationship between IgG placental transfer ratio (neonatal/maternal) and time was studied using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression on placental transfer ratio and time elapsed since dose 2 (weeks). CIs are represented by shaded region (95% CI 0.11–0.16). Lower and upper prediction intervals are indicated with dotted blue lines. Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.6.3, RStudio 1.1.463.

Prabhu. COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2021.

DISCUSSION

Messenger RNA–based COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant women lead to maternal antibody production as early as 5 days after the first vaccination dose and transplacental transfer of passive immunity to the neonate as early as 16 days after the first vaccination dose. The increasing levels of maternal IgG over time and the increasing placental IgG transfer ratio over time suggest that timing between vaccination and birth may be an important factor to consider in vaccination strategies of pregnant women. Given the variability in antibody transfer and lack of transfer to one neonate, further studies are needed to understand the factors that influence transplacental transfer of IgG antibodies, as well as the protective nature of these antibodies.

Footnotes

Yawei J. Yang is funded through the COVID-19 research grant at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Financial Disclosure Zhen Zhao received seed instruments and sponsored research from ET Healthcare and sponsored research from Roche. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Published online ahead-of-print April 28, 2021.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C318.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021;384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray KJ, Bordt EA, Atyeo C, Deriso E, Akinwunmi B, Young N, et al. COVID-19 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mithal LB, Otero S, Shanes ED, Goldstein JA, Miller ES. Cord blood antibodies following maternal COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.035 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubiak JM, Murphy EA, Yee J, Cagino KA, Friedlander RL, Glynn SM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 serology levels in pregnant women and their neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.01.016 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang HS, Racine-Brzostek SE, Lee WT, Hunt D, Yee J, Chen Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody characterization in emergency department, hospitalized and convalescent patients by two semi-quantitative immunoassays. Clin Chim Acta 2020;509:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2. 2021. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/137605/download [Google Scholar]