Abstract

Background

. High-quality comprehensive data on short-/long-term physical/mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are needed.

Methods

. The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT) is an international, multi-language (n=30) project involving >230 investigators from 49 countries/territories/regions, endorsed by national/international professional associations. COH-FIT is a multi-wave, on-line anonymous, cross-sectional survey [wave 1: 04/2020 until the end of the pandemic, 12 months waves 2/3 starting 6/24 months threreafter] for adults, adolescents (14-17), and children (6-13), utilizing non-probability/snowball and representative sampling. COH-FIT aims to identify non-modifiable/modifiable risk factors/treatment targets to inform prevention/intervention programs to improve social/health outcomes in the general population/vulnerable subgrous during/after COVID-19. In adults, co-primary outcomes are change from pre-COVID-19 to intra-COVID-19 in well-being (WHO-5) and a composite psychopathology P-Score. Key secondary outcomes are a P-extended score, global mental and physical health. Secondary outcomes include health-service utilization/functioning, treatment adherence, functioning, symptoms/behaviors/emotions, substance use, violence, among others.

Results

. Starting 04/26/2020, up to 14/07/2021 >151,000 people from 155 countries/territories/regions and six continents have participated. Representative samples of ≥1,000 adults have been collected in 15 countries. Overall, 43.0% had prior physical disorders, 16.3% had prior mental disorders, 26.5% were health care workers, 8.2% were aged ≥65 years, 19.3% were exposed to someone infected with COVID-19, 76.1% had been in quarantine, and 2.1% had been COVID 19-positive.

Limitations

. Cross-sectional survey, preponderance of non-representative participants.

Conclusions

. Results from COH-FIT will comprehensively quantify the impact of COVID-19, seeking to identify high-risk groups in need for acute and long-term intervention, and inform evidence-based health policies/strategies during this/future pandemics.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, functioning, physical health, representative, well-being, resilience, survey, international, psychiatry, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic, COH-FIT, children, adolescents, adults

1. Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 virus (known as Coronavirus) a global pandemic. Up until July 23rd, 2021, 192,694,293 individuals had confirmed COVID-19 infection, and 4,138,605 died.(Dong et al., 2020; Johns Hopkins University, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020) The infection was first detected in China and subsequentially in all six inhabited continents, leading to almost ubiquitous public health restrictive measures (e.g., personal/public space hygiene measures, social/physical distancing, travel restrictions, personal protective equipment, quarantine). Both the COVID-19 pandemic and applied restrictive measures can have marked detrimental effects on physical and mental health-related quality of life and functioning of the general population(Kazan Kizilkurt et al., 2020) and in specific population groups, which could be at increased risk of poor health and well-being during infection times (i.e., health workers, children, elderly, individuals with physical or mental conditions,(Alonso et al., 2021; Anmella et al., 2020; Lima et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; Salazar de Pablo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020) refugees/social/ethnic/linguistic minority groups, people experiencing relevant financial loss/losing their job).

A pandemic is a very stressful event per se, considering exposure to deaths, multi-level restrictions, emotions of fear and an uncertain future. In the U.S. only, it is estimated that up to 40 million people will lose their job due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the lower socio-economic strata of the population bearing the hardest consequences.(Poor Americans Hit Hardest by Job Losses Amid Covid-19 Lockdowns, Fed Says - The New York Times, 2021) Moreover, behavioural restriction and social isolation measures have forced drastic life-style changes in every-day (co-)living conditions, which can (independently from the infection's spreading) introduce additional stress with concurrently minimized stress management resources access/availability, and potentially trigger unhealthy life-style, coping strategies, and verbal and physical aggressive behaviours within households.(Fullana et al., 2020) Extended exposure to overall stress may contribute to alterations in biological stress-responsive systems (i.e., hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, autonomic nervous system, sympatho-adreno-medullary system, immune system) and precipitate physical and mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety disorders)(Chrousos, 2009) or negatively affect ongoing conditions in people already affected by mental or physical conditions. Beyond an immediate impact on health, the pandemic might also have delayed onset or long-term consequences in people not returning to their baseline after the removal of the stressful pandemic.

Taken together, apart from the direct COVID-19-infection-related health complications, secondary/indirect physical/mental health complications might represent the much larger, crucial and still unpredictable public-health-related burden of the pandemic.(Clark et al., 2020) However, only few studies have currently reported original, nationally/geographically comparable, inclusive and multi-language, representative data on health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, and even less have included person-level assessments from the pre-COVID-19 period. In contrast, most studies have reported on data only from individual countries, with small and non-representative sample sizes, a focus on subgroups and/or very restricted sets of outcomes.(Thomas et al., 2020) Most published/registered/ongoing studies on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have used an either single-wave cross-sectional or longitudinal design assessing the general population or, even more so, specific groups in a single country (or restricted set of). The largest cross-sectional planned study to the best of our knowledge targeted sample size of 65,000 subjects (NCT04378452), while most studies had <10,000 participants. Few longitudinal studies are targeting large national samples, such as one UK study planning to recruit >1,000,000 people (ISRCTN97041334), or have a multi-national approach, such as one study planning to recruit in 14 countries (NCT04367337). However, even such large studies did not consider linguistic/ethnic minorities, most studies use <5 mental-health-related assessment instruments, and few studies include non-psychological parameters, behavioural coping, or detailed demographic data.(Thomas et al., 2020) Acknowledging these gaps in the existing and evolving literature, and considering the unclear mechanisms underlying associations between the COVID-19 pandemic and health outcomes, unclear epidemiologic estimates, possible persistence of adverse outcomes after the pandemic in subgroups, unclear risk and protective factors, and differences across countries, large multi-language studies collecting multi-dimensional data throughout the pandemic from all the six continents are urgently needed.

This article presents the hypotheses, methodology and current dissemination status (July 23rd, 2021) of the Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT), a large-scale, inclusive and multi-language global study and unique collaboration between over >230 researchers from 49 countries/territories/regions and six continents, focusing on the adult particpant part of the survey study. Concurrently, we put the COH-FIT project in the context of previous or ongoing research on mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The design of the COH-FIT study may allow the better identification of non-modifiable/modifiable multisystem risk/resilience factors, and inform and facilitate both acute/long-term preventive responses and better adaptation capacity to the COVID-19 pandemic, without leaving linguistic minorities behind, potentially informing also evidence-based strategies for future pandemics/global crises.

2. Study design and methodology

In this section, the COH-FIT project is outlined regarding design, registration, objectives, hypotheses, development, researchers and institutions, countries/territories/regions involved, timeline, primary/key secondary/secondary outcomes, target populations, questionnaire development, variable selection, survey structure, survey platform, recruitment strategies, data storage and management, envisioned statistical analyses, funding, focusing on the COH-FIT-Adult (COH-FIT-A) part of the survey study. A description of the design of COH-FIT-Adolescent (COH-FIT-AD) and COH-FIT-Child (COH-FIT-C) is available elsewhere.(Solmi et al., 2021)

2.1. Clinical trial registration statement

The protocol of the COH-FIT study was finalized before first data collection, submitted on April 27th to ClinicalTrials.gov and officially registered there on May 12th, 2020 (Identifier: NCT04383470).

2.2. Objectives and hypotheses

The primary objective of COH-FIT is to assess, quantify and understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and related protective measures on the health and well-being, as well as on social, behavioural outcomes and coping strategies, and health-service functioning in the general population, and across specific population risk groups. Our hypotheses are that both physical and mental health and well-being of the general population is heterogeneously affected by the pandemic. Some groups that are characterized by non-modifiable risk factors are at increased risk of poor outcome, but also certain individual/environmental/institutional modifiable risk factors are identifiable, informing resource allocation for interventions/preventive strategies during present/future infection times.

2.3. Collaborator network

The COH-FIT project, with >230 clinicians/researchers/academicians, across 49 countries/territories/regions and six continents, embraces to the authors’ knowledge currently the largest global network (full list available at: www.coh-fit.com/collaborators/) among COVID-19 related health projects. Principal investigators of the COH-FIT project (Fig. 1 ) are Christoph U. Correll, MD, and Dr. Marco Solmi, MD, PhD (details available at: https://www.coh-fit.com/project-leads/). Coordinating co-investigators are Agorastos Agorastos, MD, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, and Andrés Estradé, MSc, Universidad Católica, Uruguay. Individual reseachers from the professional network of PIs were invited to the project, with subsequent spontaneous team compositions at country level. Clear criteria for participating to global and local papers were set and agreed upon. No formal agreement was signed by any member, and the project has been developed based on mutual trust and consideration, globally coordinated by the coPIs and study coordinators, and locally at country level.

Fig. 1.

Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT) logo.

2.4. Supporting and endorsing organizations

COH-FIT is supported by many organizations/institutions, and national scientific associations including European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Network on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Mental Health Promotion (ECNP PMD-MHP), European Psychiatric Association (EPA), World Association of Social Psychiatry (WASP), European Lifestyle Medicine Organization (ELMO), The Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health (ACAMH), World Alliance for Crisis Helplines, among many more (full list of supporting partners available at https://www.coh-fit.com/partners/).

Partners that funded COH-FIT are listed in details in supplementary Table 5.

2.5. Study design and timeline

The COH-FIT study is a cross-sectional survey, structured in three consecutive waves (wave 1, during the COVID-19 pandemic until the World Health organization (WHO) has declared the pandemic over; wave 2, starting six months later, lasting 12 months; wave 3, 24 months later, lasting 12 months). Although cross-sectional at an individual level, COH-FIT continuously collects information during and after the pandemic, ultimately collecting longitudinal data at a population level, since individuals of the population are being sampled and assessed at different times and regional severities of the pandemic and related restrictions and effects. Study participation is anonymous. No country is excluded.

2.6. Ethics committee approval

The online survey launch on the COH-FIT website (www.coh-fit.com) occurred immediately after the first ethics committee/Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, 04/27/2020). Afterwards, prior to active local/national investigator outreach and advertisement activities regarding COH-FIT dissemination, approval or waiver (due to the anonymous, observational nature of the study) was sought from at least one national IRB.

2.7. Target population and targeted minimum sample size

The COH-FIT study targets adults (≥18 years old) in all countries/territories/regions, plus adolescents (14-17) and children (6-13) in most countries. Demographic, socio-economic, occupational, and clinical variables will identify specific population subgroups (i.e., age groups, genders, mental or physical conditions, pregnant women, health workers, immigrants, etc.). The minimum targeted sample size upon study design was 50,000 participants in wave 1, and 30,000 each in wave 2 and 3. Since the survey participation is anonymous, individuals can't be matched across consecutive waves, but in waves 2 and 3, participants will be asked if they participated in a prior COH-FIT wave.

2.8. Continent and country participation

The COH-FIT survey is freely accessible online. COH-FIT collaborators from 49 countries/territories/regions are actively promoting/disseminating/advertising the COH-FIT study via multi-channel approaches after IRB approval or waiver (see above). The following 49/territories/regions countries are part of the COH-FIT via >230 local COH-FIT collaborators from over 120 institutions: i) Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda; ii) Asia: Bangladesh, China, India, Iran, Israel, Japan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Palestine, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand; iii) Europe: Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom; iv) North America: Canada, Mexico, United States of America; v) Oceania: Australia; vi) South America: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay.

2.9. Language availability and survey translations

The survey is currently available in the following 30 languages: Arabic, Bengalese, Chinese (traditional), Chinese (simplified), Czech, Danish, Dutch (Belgium), Dutch (Netherlands), English, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Persian (Farsi), Portuguese (Brazil), Portuguese (Portugal), Romanian, Romansch, Russian, Serbian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Urdu, Xhosa.

For each language, the original English version underwent two independent forward translations, followed by a harmonization of the two versions to create a target-language version, and one independent back-to-English translation by a third translator blinded to the original English version. The final version required the consensus of the three translators. Translators were healthcare professionals with specific competence in both the source and target language and questionnaire validation.

2.10. Survey platform, data management and protection

COH-FIT survey data are collected, stored and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software tool hosted at the Department of Neurosciences of the University of Padua, Italy, and at Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany.(Harris et al., 2009) REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies and used in >3,700 institutions worldwide and provides: 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources. The application and data part reside on two separate virtual machines. The information is stored in two different datastore nodes to ensure resilience, disaster recovery and business continuity. Backup of all information is ensured daily. The entire system is protected by two perimetral defense levels. All operations are logged as required by GDPR law. The participation to the study is 100% anonymous and voluntary. No individually identifying information or data regarding individuals’ online activity will be collected and retained. Participating countries’ national data will be made promptly available upon request to the members of each country's national COH-FIT coordinating team, prioritizing the global results dissemination before dissemination of local results. The international PIs and statistical analysis core team (see below) will have unlimited access to all global data for 15 years.

2.11. Informed consent

All adult participants must provide informed consent electronically on the survey's platform prior to initiating the survey.

2.12. Survey structure and format

2.12.1. Survey structure

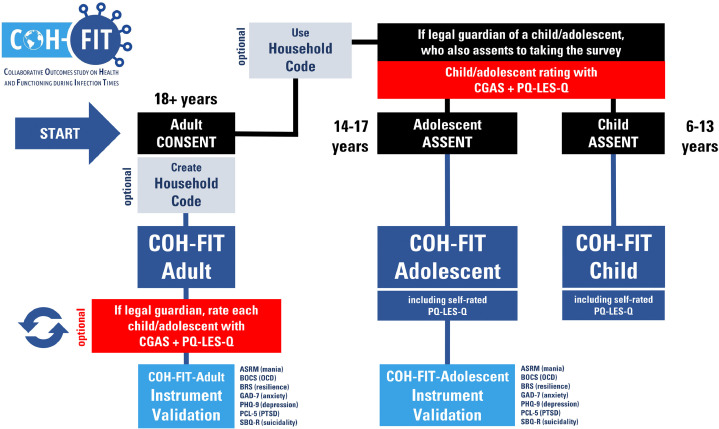

The survey is divided into three arms, namely COH-FIT-A (adults), COH-FIT-AD (adolescents), COH-FIT-C (children) (Fig. 2 ). We here focus on COH-FIT-A.

Fig. 2.

COH-FIT survey participation flow chart

Legend. ASRM, Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (Altman et al., 1997); BOCS, Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Bejerot et al., 2014); BRS, Brief Resilience Scale(Smith et al., 2008); CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale(Shaffer et al., 1983); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale(Spitzer et al., 2006); OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5(Blevins et al., 2015); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale(Kroenke et al., 2001); PQ-LES-Q, Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire(Endicott et al., 2006); PQ-16, Prodromal Questionnaire-16(Ising et al., 2012); PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; SBQ-R, Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised(Osman et al., 2001).

In the COH-FIT-A, adults first fill out the self-rated COH-FIT-A questionnaire. Additionally, participants reporting being legal guardians of minors have the option to list their children's or adolecents’ age, and physical and mental health diagnoses and rate them with the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS),(Shaffer et al., 1983) and Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q).(Endicott et al., 2006) Finally, before study completion, participants have the option to answer validated questionnaires, namely Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM),(Altman et al., 1997) Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (BOCS),(Bejerot et al., 2014) Brief Resilience Scale (BRS),(Smith et al., 2008) CGAS,(Shaffer et al., 1983) Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7),(Spitzer et al., 2006) Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9),(Kroenke et al., 2001) PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5),(Blevins et al., 2015) Prodromal Questionnaire-16,(Ising et al., 2012) Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R).(Osman et al., 2001)

2.12.2. Survey format

The survey has an adaptive format. Depending on the selected age of the participant, COH-FIT-A, COH-FIT-AD, or COH-FIT-C are individually activated. In addition, particular questions are displayed based on specific answers to preceeding questions, following a predefined branching logic. Participants have the option of saving their answers and returning later to the survey for questionnaire completion through a generated Return Code. This code is sent automatically to an individually inputed e-mail address of preference (neither the code nor email address are stored in the database) and is requested to rejoin and complete the saved questionnaire.

2.13. COH-FIT questionnaire, variables and rating

2.13.1. Targeted areas of interest

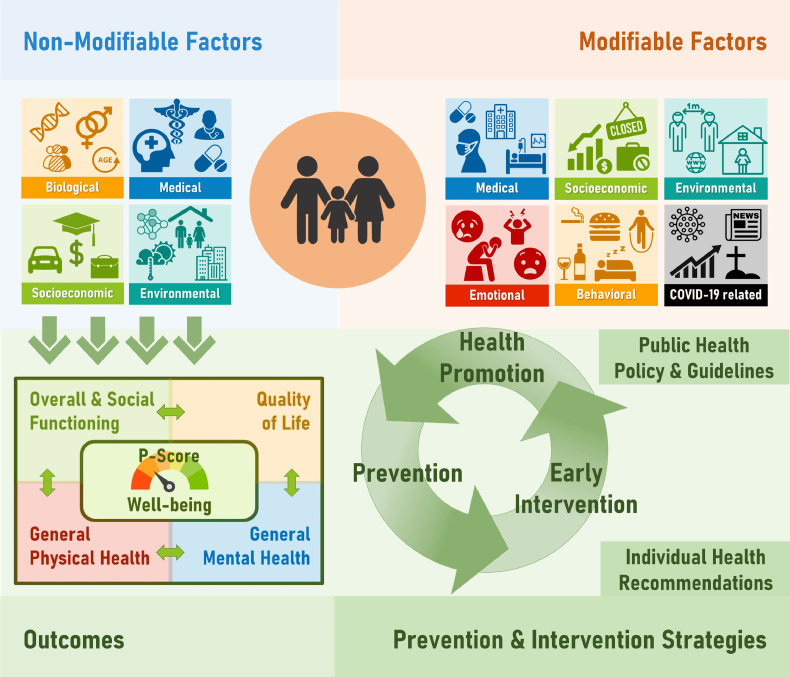

The COH-FIT questionnaire targets information on demographic and socioeconomic status including migrant status, physical and mental health, pregnancy stuatus, well-being, functioning, emotional/psychological, behavioural and environmental factors, including restrictions and COVID-19 exposure-related information, health care access/utilization, vaccine-related beliefs/behavior, treatment adherence, telehealth, personal opinions about pandemia response measures and individual coping strategies, among others. A list of modifiable/non-modifiable factors and outcomes is available in Table 1 , and Fig. 3 . “Modifiable” and “non-modifiable” labels have been assigned from a stake-holder perspective, with those labeled “modifiable” that represent promptly actionable factors.

Table 1.

A list of main variables and a-priori definition (exposure, outcome) of variables collected in the COH-FIT study.

| Non modifiable exposure |

Modifiable exposure |

Outcomes [baseline values acting also as moderators, and change values as mediators] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and socio-economic | Environmental and clinical | Behavioral/Psychological | Emotions / subjective status | Environmental and clinical | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | ||

| Age | COVID-19 infection / symptoms | Adherence to pandemic-related social restrictions | Anger | Access to medications | Well-being | Anxiety symptoms / Panic episodes | Aggressive behavior perpetration | Appetite and food intake |

| Education | COVID-19 related social restriction severity and duration | Vaccine-related beliefs and behavior | Boredom | Mental health care access/utilization | Composite mental health P-Score | Depressive symptoms | Aggressive behavior victim | BMI |

| Employment status | Family history of mental illness | Coping strategies | Fear of getting infected | Physical healthcare access/utilization | Euphoric mood/Mood swings | Aggressive behavior witnessing | Pain | |

| Ethnicity/migration | Household (rooms, outside space, co-living people, social support) | Exercise | Frustration | Access to protective devices | Key secondary outcomes | Obsessive-compulsive symptoms | Concentration | Telemedicine experience |

| Gender | Mental condition | Prosocial behavior | Helpelessness | COVID-19 information | P-Extended score | Post-traumatic symptoms | Self-injurious behavior | Impact on education |

| Job type | Medical condition | Screen time (social media, TV, gaming, reading, listening to music) | Loneliness | Economic loss | General mental health | Psychotic symptoms (Hallucinatory experiences/ delusional experiences) | Sleep problems | |

| Marital status | Past traumatic events | Sexual activity | Resilience | Healthcare system (by country) | General physical health | Suicidal ideation / attempt | Addictive behaviors/substances | |

| Socioeconomic status | Urbanicity | Stress | Number of medications | Functioning / Quality of life | ||||

Legend. Modifiable exposure will also be considered as outcomes, depending on hypotheses to be tested.

Fig. 3.

COH-FIT variables universe

Legend. P-score is a psychopathology composite score indicating an “overall” symptom measure. It includes anxiety, depressive, obsessive-compulsive, post-traumatic, delusional and hallucinatory experiences, as well stress, sleep, concentration.

2.13.2. Questionnaire development

Survey questions were chosen according to published literature on the effects of pandemics and social isolation, and ongoing survey and cohort studies assessing the health impact of COVID-19 (see Supplementary Material for the considered body of evidence). The goal was to develop a questionnaire that was easy to score through simple rating and scoring instructions, comprehensively covering the areas of evaluation specified in Table 1 and Fig. 3. The first-draft questionnaire was developed by the two PIs, which then underwent extensive testing, revision and improvement by the whole COH-FIT Consoritum who ultimately approved the final version. Specifically, after reaching consensus on the areas to be assessed by the COH-FIT survey, the item pool was screened to determine the questions’ applicability and relevance to the pandemic phases across cultures. Special attention was given to including items rating the level of COVID-19-related information in the population, access to/utilization of healthcare, current restrictive measures, specific emotional or behavioral changes. The language of the collected questions was adapted to qualify for use in the general population. Group consensus on both content and form was finally reached. The items were selected, so that the COH-FIT-A can be completed within 30-35 minutes.

To utilize a consistent and intuitive rating/scoring system that also will allow pooling across different times/dimensions, the final continuous, quantitative outcome items were as much as possible rescaled into a homogenous 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS). These outcome questions are asked for the time period of “2 weeks of normal life prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic” and for the “last two weeks prior to taking the survey”. We chose the period of two weeks to allow for a reasonable time frame that would assure stability and validity of the response and also to be consistent with the The CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS), conducted by investigators of the National Institute of Mental Health.(CRISIS, 2021) (https://github.com/nimh-comppsych/CRISIS) Exceptions to this 2-week time frame are questions about suicide attempts (lifetime before the pandemic and since the pandemic). Items for each psychopathologic/behavioral domain of interest were selected by the two PIs aiming to as much as possible capture the assessed dimension (e.g., asking about sadness and lack of interest to capture depression, about being nervous/anxious/on the edge and unable to stop worrying for anxiety, about recurrent trauma-related experiences, acting/feeling like if trauma occurring again, avoidant behavior and alert status for post-traumatic symptoms) and endorsed/approved after beta-testing by the extended COH-FIT investigator team. For some outcomes, key items were extracted from the following validated questionnaires (which were optional additional questionnaires that a subset of adults can complete after completion of COH-FIT-A to test the validity of the selected COH-FIT-A items): Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM),(Altman et al., 1997) Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (BOCS),(Bejerot et al., 2014) Brief Resilience Scale (BRS),(Smith et al., 2008) CGAS, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7),(Spitzer et al., 2006) Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9),(Kroenke et al., 2001) PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5),(Blevins et al., 2015) Prodromal Questionnaire-16,(Ising et al., 2012) Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R).(Osman et al., 2001) Answers to all questions, except for consent, the date of survey response, and age are optional.

2.14. The COH-FIT project international website

The website (www.coh-fit.com) is the project hub, providing information on the project (study design, project leads, collaborators, supporting and/or endorsing organizations, funding, relevant publications) and link to the survey in all available languages. A prominent, central link directs visitors to the survey platform, where visitors can re-select the survey language. Hourly updated study participation statistics per country are provided on an interactive world map (https://www.coh-fit.com/project-statistics/).

2.15. Participant recruitment

Two main recruitment strategies are applied. The first snowball approach generates a non-probability, convenience sample aiming to maximize the overall number of collected responses through several channels of targeted/untargeted, personal/institutional advertisement (e.g., social media, mass media, personal network, press releases, institutional newsletters) in all countries/territories/regions with IRB approval/waiver. The second approach targets nationally representative samples (with respect to sex, age, country/region, education (university: yes/no), and employment (yes/no), by paid professional polling companies collecting COH-FIT survey responses on behalf of the project members.

2.16. Primary and secondary outcomes

Co-primary outcomes are well-being, and a composite psychopathology measure (P-score). Well-being is measured with the full WHO-5 questionnaire,(Topp et al., 2015) yet answer options were converted from the six-points Likert items to a VAS 0-100 scale.

The P-score is measured as the sum of unit-weighted domains measuring symptoms in the psychopathologic spectra, including only a priori extracted items proving to be valid after external validation with full questionnaires (correlation threshold r≥0.5). A-priori domains envisioned to compose P-Score are: anxiety, depression, sleep, concentration, post-traumatic stress, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, bipolar mania, stress, and psychosis (for domains with multiple items, we will only retain the items correlating at least r≥0.2 provided the combined r≥0.5).

Singe/dual items used in the COH-FIT survey were extracted from the following validated self-report instruments: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale(Spitzer et al., 2006) for anxiety, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (Kroenke et al., 2001) for depression, sleep and concentration, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Blevins et al., 2015) for post-traumatic stress, Brief Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Bejerot et al., 2014) for obsessive-compulsive symptoms, Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale(Altman et al., 1997) for bipolar mania, WHO-5(Topp et al., 2015) for stress, and the Prodromal Questionnaire-16(Ising et al., 2012) for psychosis.

Key secondary outcomes are a P-Extended score (see below), global physical health, global mental health, global health (average of physical and mental health). The P-Extended score is the sum of unit weighted domains also including those domains not correlating well enough to make it to the P-Score, plus loneliness, helplessness, and anger, for which no validated scales were utilized. For further information about the data analytic approach, see below.

Secondary outcomes include individual psychopathology domains (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, bipolar mania symptoms, mood swings, delusions, hallucinations). In addition, episodes of self-injurious behavior, panic, sleep problems are assessed. We also consider suicidality (suicidal thoughts during the pandemic only, number of suicide attempts and proportion of people attempting suicide/ number of suicide attempts during pandemic), number of episodes witnessing, experiencing or perpetrating, aggressive behavior, other psychological experiences (anger, loneliness, helplessness, fear of infection, boredom, frustration, stress, cognition, sleep, anger, helplessness), substance and behavioral addictive behaviors (cigarettes, alcohol, cannabinoids, other substances, as well as gambling). Family/social/interpersonal/work/school functioning, self-care, social interactions, hobbies/free-time are inquired about. Resilience is also considered as a potential outcome influenced by the pandemic or as an outcome moderator. Regarding physical health, general physical health, body mass index (kg/m2), and pain are measured. Social altruism is captured with experienced social support and episodes of prosocial activities. Other daily behaviors include time spent on social media, internet, gaming, watching TV, reading, listening to music, and physical activity/exercising, among others. Finally, data on the impact of COVID-19 on educational activities of medical doctors, and the impact of telemedicine on their clinical experience are collected.

Co-primary, key secondary, and secondary outcomes are measured as change between the last two weeks of regular life before COVID-19 outbreak and the immediate last two weeks before taking the COH-FIT survey.

To view the whole set of questions, readers are invited to take the survey at www.coh-fit.com.

2.17. Statistical analyses

All analyses will be conducted with either R (https://www.R-project.org)(https://www.R-project.org/. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, n.d.) or Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 15, 2017) upon consensus on scripts between two analysts to ensure consistent results across analysts, softwares, and packages.

Descriptive statistics will be used for demographic, socio-economic, environmental, clinical, behavioral and psychological variables and emotions, across modifiable and non-modifiable factors. Change of co-primary, key secondary and secondary outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic will be reported, as well as proportion of people with worst and best outcome during the pandemic. Additionally, worst or best percentile, proportions of subjects above a threshold validated against full questionnaires, or mean value during the pandemic will be used as outcomes to anwer different reseach questions.

2.17.1. Data cleaning and quality check

Any responses provided on the website before April 26th, 2020 (first COH-FIT approval by Ethical Committee and Institutional Review Board of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, on April 15th, 2020) will be removed. Only respondents providing responses to all items of two-item outcomes, or to all items but one of three or more-item outcomes, will be included in the main analyses. The allowed missing items will be imputed via multiple inputation by chained equations (using MICE alogrithm with mice(van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011) package in R).

2.17.2. Weighting and adjusting for confounding factors

In order to provide nationally representative estimates, the following weighting procedures will be applied within countries/territories/regions. Within each country, the non-representative sample will be weighted by quota of key variables e.g. age, gender, job status, education, according to official representative quota (https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population) to maximize consistency. Weighting will be applied to countries with ≥100 participants who completed the surveys, with countries with <100 left unweighted. Weighting will be performed with the “survey” package in R using the following procedures, with the primary objective of correcting survey coverage error. First, as some population reference statistics are available as joint probabilities (age X gender) but others only as marginal probabilities (education, employment), we will use iterative proportional fitting (raking) to compute sample weights that approximate the overall population distributions, but with the constraint that weights cannot exceed sample unit weights by a factor of more than 12. Second, if the fitting algorithm fails to converge for any country (e.g. due to very low sample cell sizes), we would then attempt to compute weights for that country through post-stratification, first on age X gender, and then education (second) or employment (third) in the event of non-convergence resulting from the constraints previously referred to. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

We will also run our key secondary analysis separately in by-continent analyses including an additional adjustment factor derived from direct comparison of representative vs non-representative samples on a by-continent basis.

To adjust for representativeness of each country's samples, each country will be assigned an adjustment factor accounting for the responses/country population ratio.

2.17.3. Association between factors and outcomes

The association between non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors and co-primary outcomes will be measured as follows. The association between explanatory factors and co-primary, key secondary, and secondary outcomes will be tested with multivariable linear or logistic regression analysis (depending on outcome of interest). Multivariable models will include date/country-matched COVID-19 cumulative incidence and deaths in the past 7 or 14 days (freely available repository by the Johns Hopkins University: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19), as well as country-specific and/or region-specific restriction measures drawn from the survey responses and/or national databases. Backward model selection and/or LASSO will be used to select the best multivariable model, together with literature-based relevant factors. Factors will be presented in descending order based onhttps://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19 large, medium, and small effect size associations, following Cohen's original definition (small=0.2-0.49, medium=0.5-0.79, large≥0.8).(Sullivan and Feinn, 2012) For backward model selection, in case the variables are collinear, the most statistically or clinically significant variable will be selected.

For additional publications the same analyses will be conducted on additional outcomes, with added approaches as appropriate.

2.17.4. Additional analytic approaches

Additional analytic approaches will be used. First, we will run a network analysis with a set of “nodes” selected based both on results of the primary analyses (exposure variables consistently associated with primary and secondary outcomes) and on clinical judgement. Second, we will test several path analyses, driven and suggested by the network structure and its nodes’ centrality, in order to understand the mediation and moderation role of exposure variables, to develop a mechanistic insight into what leads to poor or resilient health outcomes. Third, we will also test internal psychometric properties of questionnaires used as validation parameters (several of them are being translated for the first time in new languages). Fourth, by means of a ROC analysis, using diagnostic thresholds of validated questionnaires as valid external reference, we will identify the score of primary and secondary outcomes items with the best specificity/sensitivity trade-off. Such threshold will be used to estimate the prevalence, as well as the incidence, persistence and remission rates of likely syndromal anxiety, depressive, manic, obsessive-compulsive, post-traumatic stress disorder, at-risk for psychosis as well as of suicidal ideation symptoms during the pandemic. Fifth, machine learning techniques (e.g., LASSO or random forest) will be used to identify predictors of primary or secondary outcomes. Sixth, time-series analyses will be conducted to describe the trend of primary and secondary outcomes in relationship with the pandemic course and restrictions. Additonal secondary analysis strategies will be discussed among members of COH-FIT as relevant/appropriate for the addressed research questions.

2.17.5. Validation analyses

To test the validity of items used in the composite P-score, a Pearson correlation analysis will be conducted with the total score of validated questionnaires provided in the validation section of the COH-FIT-A survey (see above). The Pearson correlation analysis will be performed on the whole sample and by individual languages. Additionally, in an exploratory sensitivity analysis, we ill repeat the Pearson correlation analyses between the one, two, or four COH-FIT items drawn from the full questionnaires with the full respective questionnaires between two participants’ subgroups, one subgroup matched to the COH-FIT sample in the same countries/territories/regions that took part in the survey and not answering the validation questionnaires, and a second subgroup consisting of the remainder of the unmatched participants answering the validation questionnaires. We will only perform weighting procedures in case that the samples completing and not completing the validated scales are materially different on key demographic variables on a by-country level. Finally, internal validity of the P-Score will be measured with standard psychometric procedures.

2.18. Dissemination of results

Results from the COH-FIT project will be disseminated via presentations at scientific meetings, press releases and and interviews as well as scientific publications. This strategy includes at least two main papers per wave involving all collaborators merging data from all the included countries/territories/regions, one in adult participants, one in children/adolescents, which will target major medical journals. Additional manuscripts on subgroups of participants, professions, participating countries/territories/regions, and specific outcomes, etc, will be published by subgroups of authors working specifically on these topics.

3. COH-FIT preliminary dissemination results

By 23/07/2021, >150,000 subjects (adults, adolescents, children) have given consent to participate and started to answer the survey at least answering to the first question. Responses came from 155 countries/territories (49 with ≥ 50 complete adult survey): 24 in Europe, eight in Asia, five in Africa, two in North and Central America, five in South America, three in Oceania. Representative adult (aged 18+) samples have been/are being collected in 15 countries: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Denmark France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA.

4. Discussion

New information, learnings and adaptation are needed rapidly in order to minimize the likely relevant and potentially lasting negative impact of COVID-19 pandemic, including a worsening of already existing health problems and inequalities, and impact on fragile groups.(Adhikari et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Colao et al., 2020; Cowling et al., 2020; D'Agostino et al., 2020; Esposito et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2020; Kamrath et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Moreno et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Panovska-Griffiths et al., 2020; Pereira-Sanchez et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020a; Ravi, 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020; Webb Hooper et al., 2020). Acknowledging the current state of published or ongoing research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions (cf. Suppl. Material), to the best of our knowledge, so far there does not exist a study with a large-scale, multi-national, multi-language, and transdiagnostic approach that targets the complexity of a comprehensive, literature-informed list of modifiable and non-modifiable risk and protective factors influencing health, well-being, functioning, behavioral coping and social interactions as well as health-service access and functioning across the six continents, including representative samples. Investigating a small subset of the general population without at least weighting for representative quota of demographic and regional variables, likely limits a fuller understanding of the multifaceted factors and impacts that the pandemic exerts on the general population and relevant subgroups.(Holmes et al., 2020) Indeed, not every individual has been experiencing or will experience a deterioration in health during the pandemic, as several individual, demographic, socioeconomic, clinical and behavioral factors have repeatedly been shown to be closely associated with mental and physical health-related outcomes in a complex multidimensional network that can be modifiable or non-modifiable according to the management of the pandemic (Table S4).(Kamrath et al., 2020; Moreno et al., 2020; Ravi, 2020; Solmi et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020) In fact, subgroups might even have improved health due to reduced stress, for example, by not having to attend school or work in person, having increased family interactions and time, or by utilizing specific sets of coping strategies that other subgroups could also benetit from.(Luo et al., 2020) For instance, a large cohort study also showed that despite at the beginning of lockdown in United Kingdom anxiety and depression symptoms were high, they decreased across weeks following lockdown.(Fancourt et al., 2020)

In general, non-modifiable factors identify individuals at increased risk during the pandemic, who might be in need of specific interventions, while modifiable factors identify potential targets for prevention/intervention strategies. These actionable results from a large population speaking different languages across/within countries/territories/regions affected by COVID-19 across six continents are insufficiently available, limiting a desirable evidence-based and precision political and health care governance, without neglecting evidence from other-than-official language speaking minorities in each country.(Gao et al., 2020; Hanney et al., 2020; Maulik et al., 2020; Nussbaumer-Streit et al., 2020; Raboisson and Lhermie, 2020; Rhodes et al., 2020) So far, most recommendations are based on expert consensus.(Cortese et al., 2020; Moreno et al., 2020)

COH-FIT envisions to fill the current gap largely excluding linguistic/ethnic minorities across the globe, as the largest international collaborative study translated in 30 languages, collecting to our knowledge the biggest set of transdiagnostic, multi-dimensional and multi-disciplinary data from currrently 152 high-, middle-, and low-income countries/territories/regions across the globe from the general population starting from age 6. Respondents are allowed to chose their own preferred language, regardless of the country where they are answering from. Beyond that, COH-FIT particularly assesses specific populations at risk, such as minors and elderly, individuals with preexisting physical and mental disorders, lower-socioeconomic status or/and unemployed population, urban/rural area inhabitants, populations with limited access to health care and/or availability of protective devices, migrants and refugees, healthcare workers, working parents of home-school attending minors, gender minorities, pregnant women, those with economic threats, etc. In addition, COH-FIT targets pandemic effects on whole families and the relationship between of adults’ andminors’ health and functioning status, through the combined direct (COH-FIT-AD/C) and indirect (COH-FIT-A parental rating) assessment of same household family members, and specifically investigates the moderating effect of adaptive and maladaptive coping factors, including total screen time, substance use, social media usage, physical activity, social interaction, sexual activity, hobbies, etc.

The COH-FIT study is an investigator-driven project, without industry funding, which secures independent results usable by decision makers (national/international public health authorities, professional health associations, and other stakeholders), who can benefit from learnings that can be used within and across high-, middle-, and low-income countries/territories/regions in order to implement evidence-based, timely and multi-level (systemic, societal, individual) strategies for the current and, possibly, future pandemic outbreaks. The participant recruitment of the COH-FIT survey has been already proven effective with over 150,000 participants from 155 countries/territories/regions on July 23rd, , 2021 since its launch in April 2020.

COH-FIT has limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the study has a three-wave, cross-sectional design, allowing data collection in each wave over an extended period of time (duration of the pandemic, and up to 36 (waves 2 plus 3) post-end of the COVID-19 pandemic) during heterogeneous scenarions regarding both the pandemic and the applied protective measures. Furthermore, depending on IRB approval, the beginning of the proactive dissemination/advertising of the COH-FIT questionnaire varies across countries/territories/regions within the COH-FIT network. We plan to account for such heterogenenity by collecting information on restrictions in the COH-FIT questionnaire, and supplementing multivariate models with the temporally and locally fine-graned data from the Johns Hopkins website.(Dong et al., 2020) On the other hand, the variation in environmental “viral load” and related restrictions over time and regions will also allow for time-series analyses plotting primary, secondary outcomes, but also environmental “exposure” following the pandemic breakout throughout time. Second, retrospective items referring to the 2-week time period before the pandemic outbreak are vulnerable to recall bias. Third, the COH-FIT questionnaire includes several non-validated items for primary and secondary outcomes. However, most of these items have been extracted from already validated tools, and will undergo external/internal validation assessment. Fourth, the majority of respondents are recruited via a snow-ball/ yielding non-representative/biased sample. However, we designed the study to also include representative samples to assess differences in the results between representative and non-representative samples and to weight non-representative responses according to representative quota (age, gender, region, job status, education). Yet, residual bias is always present in representative samples.(Pierce et al., 2020b) Fifth, the survey is long, which may lead to incomplete assessments in certain subgroups. However, we placed the co-primary outcome questions early within the questionnaire, right after key demographic and COVID-19 related questions. Moreover, we will assess if certain demographic variables are associated with non-completion of the survey, and will weight results based on representative quota.

Taken together, COH-FIT is a unique, inclusive multi-language study collecting large-scale, multi-dimensional data on individual, society, and services outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe. COH-FIT measures health, behavior, well-being, quality of life, health-service and society functioning as outcomes (among others), and accounts for the likely largest set of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors to date, including ethnicity, ongoing conditions, job, psychological factors (resilience), financial loss, pandemic burden and course, restrictions, among many others. The multi-wave, detailed, multi-level insight generated by the COH-FIT project is expected to be instrumental for multi-level guideline development and implementation of targeted interventions on key parameters identified by the COH-FIT results. It is hoped that the resulting data will be informative on an individual and global level, contributing to the much-needed development and refinement of evidence-based and precision resource allocation and governance during this and future infection times in order to improve overall outcomes.

Funding statement

All the institutions and funding agencies are listed in supplementary Table 5. COH-FIT PIs and collaborators have applied/are actively applying for several national and international grants to cover expenses related to the coordination of the study, website, nationally representative samples, advertisement of the study, and future dissemination of study findings.

Authors' contribution

Christoph U. Correll (CUC), Marco Solmi (MS), designed the study. Agorastos Agorastos (AA), Andres Estradè (AE), CUC, MS wrote the study protocol. Ai Koyanagi (AK), CUC, Dimitris Mavridis (DM), Elena Dragioti (ED), Friedrich Leisch (FL), MS, Joaquim Radua (JR), Trevor Thompson (TT) designed the statistical analysis plan. AA, AE, CUC, Davy Vancampfort (DV), MS conducted a preliminary review of the available publications and ongoing registered studies. All authors contributed to the final version of the COH-FIT survey and are involved in disseminating the COH-FIT survey link and collecting the data and designing and preparing research reports on national data. All local researchers contributed to and approved translations of the COH-FIT survey in their respective language. AK, CUC, DM, ED, FL, MS,JR, TT, had access to the global raw data on participation results. AA, AE, CUC, MS, wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors read, contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All conflict of interest statements of all authors are detailed in Supplementary Table 6.

Acknowledgement

All authors thank all respondents who took the survey so far, funding agencies and all professional and scientific national and international associations supporting or endorsing the COH-FIT.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.116.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Adhikari S., Pantaleo N.P., Feldman J.M., Ogedegbe O., Thorpe L., Troxel A.B. Assessment of community-level disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections and deaths in large US metropolitan areas. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J., Vilagut G., Mortier P., Ferrer M., Alayo I., Aragón-Peña A., Aragonès E., Campos M., Cura-González I.D., Emparanza J.I., Espuga M., Forjaz M.J., González-Pinto A., Haro J.M., López-Fresneña N., Salázar A.D.M.de, Molina J.D., Ortí-Lucas R.M., Parellada M., Pelayo-Terán J.M., Pérez-Zapata A., Pijoan J.I., Plana N., Puig M.T., Rius C., Rodríguez-Blázquez C., Sanz F., Serra C., Kessler R.C., Bruffaerts R., Vieta E., Pérez-Solà V. Mental health impact of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers: a large cross-sectional survey. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman, E.G., Hedeker, D., Peterson, J.L., Davis, J.M., 1997. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anmella G., Fico G., Roca A., Gómez-Ramiro M., Vázquez M., Murru A., Pacchiarotti I., Verdolini N., Vieta E. Unravelling potential severe psychiatric repercussions on healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 crisis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Pasea L., Harris S., Gonzalez-Izquierdo A., Torralbo A., Shallcross L., Noursadeghi M., Pillay D., Sebire N., Holmes C., Pagel C., Wong W.K., Langenberg C., Williams B., Denaxas S., Hemingway H. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1715–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerot S., Edman G., Anckarsäter H., Berglund G., Gillberg C., Hofvander B., Humble M.B., Mörtberg E., Rastam M., Stahlberg O., Frisén L. The Brief Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (BOCS): a self-report scale for OCD and obsessive-compulsive related disorders. Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2014;68:549–559. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.884631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins C.A., Weathers F.W., Davis M.T., Witte T.K., Domino J.L. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress. 2015;28:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009;5:374–381. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark H., Coll-Seck A.M., Banerjee A., Peterson S., Dalglish S.L., Ameratunga S., Balabanova D., Bhutta Z.A., Borrazzo J., Claeson M., Doherty T., El-Jardali F., George A.S., Gichaga A., Gram L., Hipgrave D.B., Kwamie A., Meng Q., Mercer R., Narain S., Nsungwa-Sabiiti J., Olumide A.O., Osrin D., Powell-Jackson T., Rasanathan K., Rasul I., Reid P., Requejo J., Rohde S.S., Rollins N., Romedenne M., Singh Sachdev H., Saleh R., Shawar Y.R., Shiffman J., Simon J., Sly P.D., Stenberg K., Tomlinson M., Ved R.R., Costello A. After COVID-19, a future for the world's children? Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31481-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A., Piscitelli P., Pulimeno M., Colazzo S., Miani A., Giannini S. Rethinking the role of the school after COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e370. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S., Asherson P., Sonuga-Barke E., Banaschewski T., Brandeis D., Buitelaar J., Coghill D., Daley D., Danckaerts M., Dittmann R.W., Doepfner M., Ferrin M., Hollis C., Holtmann M., Konofal E., Lecendreux M., Santosh P., Rothenberger A., Soutullo C., Steinhausen H.C., Taylor E., Van der Oord S., Wong I., Zuddas A., Simonoff E. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling B.J., Ali S.T., Ng T.W.Y., Tsang T.K., Li J.C.M., Fong M.W., Liao Q., Kwan M.Y., Lee S.L., Chiu S.S., Wu J.T., Wu P., Leung G.M. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e279–e288. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISIS [WWW Document], 2021. URL https://github.com/nimh-comppsych/CRISIS.

- D'Agostino A., Demartini B., Cavallotti S., Gambini O. Mental health services in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Nee J., Yang R., Wohlberg C. Pediatric quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q): reliability and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2006;45:401–407. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000198590.38325.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C., D’Agostino A., Dell’Osso B., Fiorentini A., Prunas C., Fontana E., Gargano G., Viscardi B., Giordano B., D’Angelo S., Wiedenmann F., Macellaro M., Giorgetti F., Turtulici N., Gambini O., Brambilla P. Impact of the first COVID-19 pandemic wave on first episode psychosis in Milan, Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2021;298(113802) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113802. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana M.A., Hidalgo-Mazzei D., Vieta E., Radua J. Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Liu R., Zhou Q., Wang X., Huang L., Shi Q., Wang Z., Lu S., Li W., Ma Y., Luo X., Fukuoka T., Ahn H.S., Lee M.S., Luo Z., Liu E., Chen Y., Shu C., Tian D. Application of telemedicine during the coronavirus disease epidemics: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020;8:626. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3315. –626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanney S.R., Kanya L., Pokhrel S., Jones T.H., Boaz A. How to strengthen a health research system: WHO's review, whose literature and who is providing leadership? Heal. Res. policy Syst. 2020;18:72. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00581-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A.K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Worthman C.M., Yardley L., Cowan K., Cope C., Hotopf M., Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;0 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. https://www.R-project.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing . A.U.R.L., n.d. R Core Team; Vienna: 2019. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ising H.K., Veling W., Loewy R.L., Rietveld M.W., Rietdijk J., Dragt S., Klaassen R.M.C., Nieman D.H., Wunderink L., Linszen D.H., van der Gaag M. The validity of the 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38:1288–1296. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University, 2020. Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) [WWW Document]. URL https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed 4.22.20).

- Kamrath C., Mönkemöller K., Biester T., Rohrer T.R., Warncke K., Hammersen J., Holl R.W. Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan Kizilkurt Ozlem, MD, Dilbaz Nezrim, MD, Noyan Cemal Onur., MD Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on General Population in Turkey: Risk Factors. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2020;32(8):1. doi: 10.1177/1010539520964276. In this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima C.K.T., Carvalho P.M., de M., Lima I., de A.A.S., Nunes J.V.A., de O., Saraiva J.S., de Souza R.I., da Silva C.G.L., Neto M.L.R. The emotional impact of coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease) Psychiatry Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Bao Y., Huang X., Shi J., Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020;4 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik P.K., Thornicroft G., Saxena S. Roadmap to strengthen global mental health systems to tackle the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020;14:57. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00393-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S., Nordentoft M., Crossley N., Jones N., Cannon M., Correll C.U., Byrne L., Carr S., Chen E.Y.H., Gorwood P., Johnson S., Kärkkäinen H., Krystal J.H., Lee J., Lieberman J., López-Jaramillo C., Männikkö M., Phillips M.R., Uchida H., Vieta E., Vita A., Arango C. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.-G., Ma W., Mehta R.S., Warner E.T., Sikavi D.R., Lo C.-H., Kwon S., Song M., Mucci L.A., Stampfer M.J., Willett W.C., Eliassen A.H., Hart J.E., Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Davies R., Capdevila J., Lee K.A., Lochlainn M.N., Varsavsky T., Sudre C.H., Cardoso M.J., Wolf J., Spector T.D., Ourselin S., Steves C.J., Chan A.T., Consortium, =COronavirus Pandemic Epidemiology Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer-Streit B., Mayr V., Dobrescu A.I., Chapman A., Persad E., Klerings I., Wagner G., Siebert U., Christof C., Zachariah C., Gartlehner G. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Bagge C.L., Gutierrez P.M., Konick L.C., Kopper B.A., Barrios F.X. The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8:443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panovska-Griffiths J., Kerr C.C., Stuart R.M., Mistry D., Klein D.J., Viner R.M., Bonell C. Determining the optimal strategy for reopening schools, the impact of test and trace interventions, and the risk of occurrence of a second COVID-19 epidemic wave in the UK: a modelling study. The Lancet Child And Adolescent Health. 2020;4(11):817–827. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30250-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Sanchez V., Adiukwu F., El Hayek S., Bytyçi D.G., Gonzalez-Diaz J.M., Kundadak G.K., Larnaout A., Nofal M., Orsolini L., Ramalho R., Ransing R., Shalbafan M., Soler-Vidal J., Syarif Z., Teixeira A.L.S., da Costa M.P. COVID-19 effect on mental health: patients and workforce. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e29–e30. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., Kontopantelis E., Webb R., Wessely S., McManus S., Abel K.M. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., McManus S., Jessop C., John A., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S., Wessely S., Abel K.M. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Graziosi S, Brunton J, Ghouze Z, O'Driscoll P, Bond M (2020). EPPI-Reviewer: advanced software for systematic reviews, maps and other evidence synthesis [Software]. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/CMS/Default.aspx?alias=eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4 [last access July 23rd, 2021].

- Poor Americans Hit Hardest by Job Losses Amid Covid-19 Lockdowns, Fed Says - The New York Times [WWW Document], 2021. URL https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/business/economy/coronavirus-jobless-unemployment.html (accessed 5.29.20).

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboisson D., Lhermie G. Living with COVID-19: a systemic and multi-criteria approach to enact evidence-based health policy. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:294. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi K. Ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality: are comorbidities to blame? Lancet. 2020;396:22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T., Rhodes T., Lancaster K., Lees S., Parker M. Modelling the pandemic: attuning models to their contexts. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2020;5:2914. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar de Pablo G., Vaquerizo-Serrano J., Catalan A., Arango C., Moreno C., Ferre F., Shin J.Il, Sullivan S., Brondino N., Solmi M., Fusar-Poli P. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D., Gould M.S., Brasic J., Fisher P., Aluwahlia S., Bird H. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Lu Z.A., Que J.Y., Huang X.L., Liu L., Ran M.S., Gong Y.M., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y.K., Shi J., Bao Y.P., Lu L. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M., Estrade A., Agorastos A., Radua J., Cortese S., Dragioti E., Leisch F., Vancampfort D., Thompson T., Correll C., et al. Physical and mental health impact of COVID-19 on children, adolescents, and their families: the Collaborative Outcome study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times - Children and Adolescents (COH-FIT-C&A) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.090. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M., Koyanagi A., Thompson T., Fornaro M., Correll C.U., Veronese N. Network analysis of the relationship between depressive symptoms, demographics, nutrition, quality of life and medical condition factors in the Osteoarthritis Initiative database cohort of elderly North-American adults with or at risk for osteoarthritis - CORRIGENDUM. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019;1 doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Statistical Software: Release 15., 2017.

- Sullivan G.M., Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012;4:279–282. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R.K., Suleman R., Mackay M., Hayer L., Singh M., Correll C.U., Dursun S. Adapting to the impact of COVID-19 on mental health: an international perspective. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1503/jpn.200076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp C.W., Østergaard S.D., Søndergaard S., Bech P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015;84:167–176. doi: 10.1159/000376585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S., Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Software. 2011;45(Issue 3) doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viner R.M., Russell S.J., Croker H., Packer J., Ward J., Stansfield C., Mytton O., Bonell C., Booy R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M., Nápoles A.M., Pérez-Stable E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020. COVID-19 situation reports [WWW Document]. URL https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed 4.22.20).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.