Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (BDVT), a rare ventricular arrhythmia, is commonly caused by digitalis toxicity or channelopathies and is rarely…

Key Words: bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, sarcoidosis, ventricular arrhythmia, ventricular bigeminy, ventricular tachycardia

Abstract

Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (BDVT), a rare ventricular arrhythmia, is commonly caused by digitalis toxicity or channelopathies and is rarely caused by aconite toxicity, myocarditis, infarction, or sarcoidosis. This paper describes a patient with BDVT, recurrent syncope, myocardial disarray, and interstitial fibrosis on histology but normal results on echocardiography with variants in the TTN, KCNH2, and GATA4 genes. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Graphical abstract

Presentation

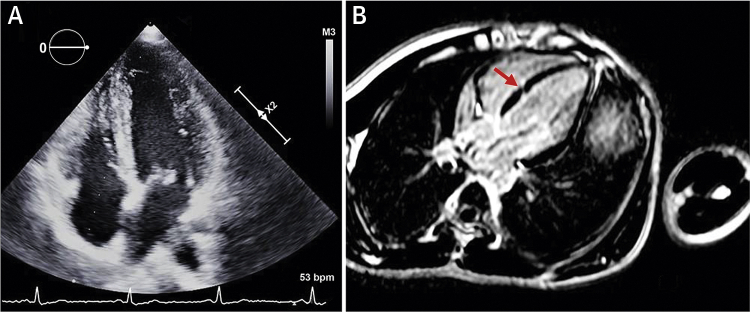

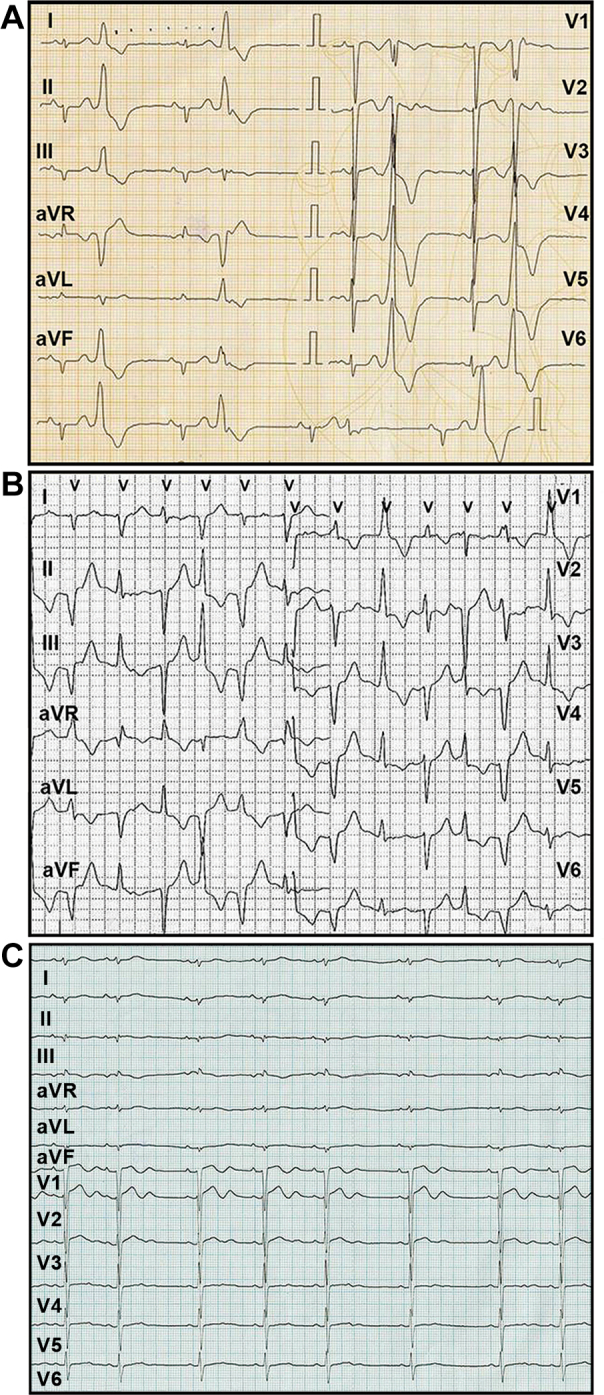

An 11-year-old male patient presented with recurrent history of syncope during exercise for the previous 5 years. There were no prodromal symptoms associated with loss of consciousness or symptoms after recovery within 1 min. The patient was not taking medications or dietary or herbal supplements. Physical examination was unremarkable except for the presence of regularly irregular pulse. Resting electrocardiography (ECG) results showed premature ventricular complexes (PVC) of the left bundle branch block (LBBB) shape in lead V1 in the form of ventricular bigeminy (Figure 1A). Blood chemistry test results were normal. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory Holter monitor traces showed multiple PVCs (n = 24,957 in 24 h) of LBBB (Figure 1A), and right bundle branch block (RBBB) (Figure 1B), and several short runs of nonsustained ventricular rhythm, the longest of which was of RBBB morphology shapes in V1 with alternating left and right frontal axes (Figure 1B).

Learning Objectives

-

•

Work-up of patients with bidirectional VT to narrow the differential diagnosis by stepwise use of ECG, exercise stress test, imaging, biopsy, and genetic testing.

-

•

Importance of histology and genetic testing to assess for early manifestation of concealed form of a disease, for example, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in this case.

-

•

Management of bidirectional VT with beta-blockers and flecainide as recommended for CPVT, with monitoring for potential adverse effects, use of ICD for secondary prevention of sudden death, and use of uncommon antiarrhythmic agent that effectively suppressed refractory VT in this patient in the acute setting and over the long term.

Figure 1.

Ventricular Premature Complexes and Slow Bidirectional Ventricular Rhythm

(A) Resting electrocardiogram of premature ventricular complexes in the form of ventricular bigeminy. (B) 24-h Holter monitor traces demonstrating a run of nonsustained slow ventricular rhythm with right bundle branch block morphology in V1 but alternating left and right frontal axis. (C) ECG in sinus rhythm with sinus arrhythmia, a QTc complex of 0.39 s, and a large U-wave in the precordial lead with a QTU interval of 0.51 s.

Medical History

No significant illnesses. No family history of cardiac disorder or sudden death.

Differential Diagnosis

Bidirectional ventricular rhythm or tachycardia: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT); Andersen-Tawil syndrome (ATS); digoxin toxicity; aconitine toxicity; myocarditis; myocardial ischemia; familial hypokalemic periodic paralysis; sarcoidosis; tumor of the ventricle.

Investigations

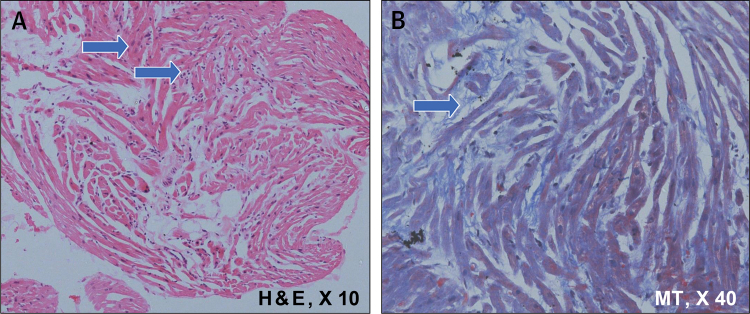

Echocardiography demonstrated normal biventricular function, wall thickness, and chamber dimensions (Figure 2A). Exercise ECG failed to demonstrate any signs of myocardial ischemia, sustained arrhythmias, or VT. The PVC frequency, however, increased with exercise. With the clinical history of exertional syncope and documented nonsustained slow bidirectional ventricular rhythm with structurally normal heart by echocardiography, cardiac channelopathy (CPVT vs. ATS) was believed to be the most probable diagnosis with history negative for digoxin or aconitine use and normal imaging study results. Neuroelectrophysiological testing was negative for ATS.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic and CMR Images of the Proband Heart

(A) Apical 4-chamber view of 2-dimensional echocardiogram showing normal wall thickness and chamber dimensions. (B) CMR image of 4-chamber phase sensitive inversion recovery view demonstrating a linear myocardial crypt (arrow) seen on 3D balanced turbo field-echo sequence images enhancing post-contrast on delayed images. There was no evidence of ventricular septal defect or ventricular hypertrophy. CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance.

Management

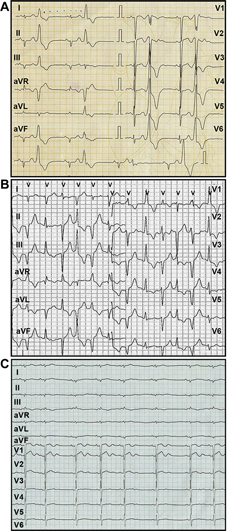

Treatment with a beta-adrenergic antagonist (metoprolol tartrate, 25 mg twice daily) was started. When the dose of beta-blocker was increased over the next week (metoprolol tartrate, 3 times a day), the patient developed bradycardia without any decrease in PVC load. Hence, a combined therapy of reduced dose beta-blocker (metoprolol tartrate, 25 mg twice daily) and flecainide (50 mg twice daily) was started under continuous cardiac monitoring. Twenty-four hours after the initiation of flecainide, while in his hospital bed and not asleep, the patient went into cardiac arrest due to fast VT degenerating to ventricular fibrillation. The arrhythmia episode was detected immediately on the monitor and was cardioverted. The first biphasic 100-J shock failed, but successful cardioversion to sinus rhythm was achieved with the second, 200-J shock. After direct current cardioversion, ECG recoding showed frequent multifocal PVCs. Considering the possibility of flecainide toxicity, the drug was stopped, and the patient was treated with intravenous sodium bicarbonate. Sodium bicarbonate and conventional antiarrhythmic agents including amiodarone failed to control the ectopy, but the patients responded dramatically to intravenous phenytoin. ECG in showed sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia, QTc of 0.39 s, and prominent U-wave in the precordial lead with prolonged Q-U interval (0.51 s) (Figure 1C). Cardiac magnetic resonance tomography with gadolinium showed the presence of a deep crypt at the left ventricular aspect of the septal myocardium with associated discrete delayed post-contrast hyperenhancement (Figure 2B). Endomyocardial biopsy from the interventricular septum demonstrated myocyte disarray, increased interstitial fibrosis, and myocyte hypertrophy (Figure 3). The same histological changes were seen in all 4 biopsy samples from different areas of the interventricular septum (2 from the mid septum and 2 from the apical septum).

Figure 3.

Histological Changes on Endomyocardial Septal Biopsy Samples of the Proband Heart

(A) Endomyocardial biopsy fragment (arrows) showed mild hypertrophy with nucleomegaly, myocyte disarray (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain; original magnification ×10]). (B) Intermyofiber fibrosis (blue arrow) (Masson trichrome [MT] stain; original magnification ×40). Inflammatory cell infiltrate was absent.

With the histological changes suggestive of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) in the absence of imaging evidence of ventricular hypertrophy, a diagnosis of phenotype-negative HCM (nonhypertrophic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) was considered, and genetic analysis using next generation sequencing targeting the panel of 195 genes associated with cardiomyopathies and channelopathies obtained (Strand Centre for Genomics and Personalized Medicine, Bangalore, India). Three variants were found to be significant. A heterozygous nonsense variation in TTN (p.Ala6612LeufsTer6) was classified as pathogenic and 2 heterozygous missense variations, one at KCNH2 (p.Val535Met) and the other at GATA4 (p.Pro407Gln) were classified as variants of unclear significance. Both of the patient’s parents were asymptomatic and had normal baseline ECG, echocardiography, 24-h Holter monitoring, and exercise ECG results. Genetic analysis showed that the patient’s father harbored the same variation in the TTN and KCNH2 genes, whereas the mother carried the variation in the GATA4 gene.

With the clinical, electrocardiographic, imaging, histological, and genetic data, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as dual HCM and long QTU phenotype due to variation in TTN and KCNH2. An insertable cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted. Treatment with beta-blocker and phenytoin was continued.

Discussion

The expressed phenotype of this patient is a variable combination of heart muscle disease and channelopathy. In 1990, autopsy studies reported that sudden cardiac death patients with a family history of HCM may demonstrate widespread interstitial fibrosis with myocardial disarray in the absence of ventricular hypertrophy 1, 2. The increased availability of genetic analysis in HCM patients documented the fact that a subset of individuals in the family of classical HCM patients carry the causative gene mutation in the absence of classical ventricular hypertrophy (3). This subset of individuals was categorized as a genotype positive/phenotype negative (G+P−) or a nonhypertrophic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype. Detection of myocardial crypts in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging has been suggested as a marker of G+P− HCM (4); however, this is not specific for HCM and can be observed in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy or ischemic heart disease (5). Although the natural history of G+P− subsets is reported to be mostly benign (6), there are reports of sudden cardiac arrest in G+ family members of HCM patients in the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy (7). Endomyocardial biopsy in this patient demonstrated myocardial disarray, myocyte hypertrophy, and nucleomegaly suggestive of HCM. Autopsy studies have reported that myocardial disarray may be found in some areas of normal heart (8). In the present patient, however, widespread disarray was documented in all biopsy samples obtained from the apical and mid septum and was associated with increased interstitial fibrosis, and pathological changes in cardiomyocytes reduce the possibility of “physiological disarray.” The patient had a history of recurrent exertional syncope with spontaneous recovery over the previous 5 years and developed cardiac arrest only after initiation of flecainide therapy. There is the possibility that flecainide sustained VT due to a re-entrant mechanism with slowing of conduction within the myocardium along the fibrotic area, thus creating a proarrhythmic milieu within the microscopic structural abnormality in an otherwise grossly normal heart. Alternatively, flecainide could have exerted proarrhythmic effects due to its mild potassium channel blocking properties, predisposing to prolongation of repolarization and triggered activity, particularly if the repolarization reserve was already reduced, which is a possibility due to reduction in the rapid component of the delayed rectifier current (IKr) that may result from the KCNH2 variant. Bradycardia with flecainide has been described with sinoatrial conduction delays but seems unlikely in this patient.

The genetic test revealed a variation in the TTN gene, which encodes Titin, a sarcomeric protein. TTN mutations have been reported in HCM as well as in dilated cardiomyopathy. The variation identified (c.19831delC) is predicted to cause a frame shift and consequently premature termination of the protein (p.Ala6612LeufsTer6), which could result in a loss-of-function. Although the identified variant seems to be a novel mutation, a variation immediately proximal to the site described in this patient has been reported as “disease causing” in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy (9). Whether the novel variant identified in the TTN gene in this patient with a structurally normal heart, according to echocardiography, but with histological characteristics of HCM (myocyte disarray, interstitial fibrosis, and myocyte hypertrophy), is an early manifestation of concealed HCM or of dilated cardiomyopathy is not known. This can only be determined by long-term follow-up that may reveal time-dependent expression of the phenotype.

In this patient, features such as episodes of nonsustained slow, bidirectional ventricular rhythm, PVCs of 2 different patterns, unique response of the arrhythmia to phenytoin and prominent U-wave in sinus rhythm ECG are interesting characteristics. BDVT and characteristic U-wave abnormality is a feature of ATS that presents with modest prolongation of QT and prominent U-wave and prolong QU interval, as was observed in the patient. A range of 10% to 15% of patients with genetically defined LQTS may present with baseline normal QTc (10). Phenytoin, a Class Ib antiarrhythmic agent, can reduce the duration of the action potential by inhibiting the slow sodium current and the inward calcium current in the plateau phase of action potential in Purkinje fibers (11), and clinical reports of phenytoin effectiveness in torsades de pointes, even in refractory cases, has been published (12). The unique response of arrhythmia to phenytoin may be a phenotypical expression of the complex electrophysiological milieu in the patient with myocardial disarray, fibrosis, and mutations in the TTN and KCNH2 genes.

The patient harbors a variation in KCNH2 gene that encodes the potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 protein, which plays a role in the transport of potassium ions across the cell membrane during repolarization through the rapid component of the delayed rectifier Kþ channels IKr. Pathogenic variations in the KCNH2 gene have been shown to be associated with the autosomal dominant Romano-Ward long QT syndrome (loss of function) and short QT syndrome (gain of function). The identified variant in the present patient has been previously reported in a proband and his mother with LQTS2 (13), both with normal QT intervals (QTc <450 ms), but with a prominent U-wave, such as in the patient, suggesting contributory role of the variation in the expressed phenotype.

The association between HCM and QTc prolongation has been reported with prolongation of repolarization attributed to the sheer mass of ventricular myocardium 14, 15 and electrical remodelling with down-regulation of repolarizing K+ channels. Recent studies, however, reported concomitant LQT-related gene mutations associated with QT interval prolongation in HCM patients (16) in whom the ECG changes may appear earlier than those with ventricular hypertrophy alone (17).

In the present study, both the child and his father harbored the same variation in TTN and KCNH2 gene, but the father lacked the variation in the GATA4 gene, which could have influenced the selective expression of disease phenotype in the proband. Thus, the GATA4 variation could be acting as a genetic modifier in the patient, as previously reported for patients with HCM (18).

Follow-up

During 3 years’ follow-up, this patient has been asymptomatic, without any clinical VT or any significant ventricular arrhythmia, documented on 24 h ambulatory ECG monitoring. Follow-up echocardiography has so far failed to demonstrate any ventricular hypertrophy or dilatation.

Conclusions

BDVT with structurally normal heart has been described in at least 2 channelopathies, CPVT and ATS. To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, BDVT has not been reported with any spectra of HCM. This study reports a rare case of BDVT in a patient with combined phenotype of nonhypertrophic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with prominent U wave and a prolonged QTU interval. Under autosomal dominant conditions, the absence of a family history can be explained by variable penetrance or expression of the abnormal genes; in the present case, it is proposed that GATA4 could have acted as a genetic modifier for TTN and KCNH2 in the proband, giving rise to a complex phenotype of variable combination of heart muscle and electrical disease not observed in the parents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Pfaff and Susan Nord, Aurora Cardiovascular and Thoracic Service Line, Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for their editorial assistance, and Brian Miller and Brian Schurrer for help with the figures.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.McKenna W.J., Stewart J.T., Nihoyannopoulos P., McGinty F., Davies M.J. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without hypertrophy: two families with myocardial disarray in the absence of increased myocardial mass. Br Heart J. 1990;63:287–290. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.5.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron B.J., Kragel A.H., Roberts W.C. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with normal left ventricular mass. Br Heart J. 1990;63:308–310. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.5.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron B.J., Semsarian C. Emergence of gene mutation carriers and the expanding disease spectrum of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1551–1553. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron M.S., Rowin E.J., Lin D. Prevalence and clinical profile of myocardial crypts in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:441–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.972760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Child N., Muhr T., Sammut E. Prevalence of myocardial crypts in a large retrospective cohort study by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:66. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray B., Ingles J., Semsarian C. Natural history of genotype positive-phenotype negative patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:258–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiaans I., Lekanne dit Deprez R.H., van Langen I.M., Wilde A.A. Ventricular fibrillation in MYH7-related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy before onset of ventricular hypertrophy. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1366–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker A.E., Caruso G. Myocardial disarray. A critical review. Br Heart J. 1982;47:527–538. doi: 10.1136/hrt.47.6.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansweijer J.A., Nieuwhof K., Russo F. Truncating titin mutations are associated with a mild and treatable form of dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:512–521. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moric-Janiszewska E., Markiewicz-Łoskot G., Łoskot M., Weglarz L., Hollek A., Szydłowski L. Challenges of diagnosis of long-QT syndrome in children. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:1168–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheuer T., Kass R.S. Phenytoin reduces calcium current in the cardiac Purkinje fiber. Circ Res. 1983;53:16–23. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yager N., Wang K., Keshwani N., Torosoff M. Phenytoin as an effective treatment for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia due to QT prolongation in a patient with multiple drug intolerances. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-209521. pii: bcr2015209521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao C., Lu Y., Liu M. Electrophysiological study of V535M hERG mutation of LQT2. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2011;31:741–748. doi: 10.1007/s11596-011-0670-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin A.B., Garson A., Jr., Perry J.C. Prolonged QT interval in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy in children. Am Heart J. 1994;127:64–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson J.N., Grifoni C., Bos J.M. Prevalence and clinical correlates of QT prolongation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1114–1120. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L., Zuo L., Hu J. Dual LQT1 and HCM phenotypes associated with tetrad heterozygous mutations in KCNQ1, MYH7, MYLK2, and TMEM70 genes in a three-generation Chinese family. Europace. 2016;18:602–609. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao H., Zhang Y., Liu L. [Relationship between electrocardiographic and genetic mutation (MYH7-H1717Q, MYLK2-K324E and KCNQ1-R190W) phenotype in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2016;44:50–54. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso-Montes C., Rodríguez-Reguero J., Martín M. Rare genetic variants in GATA transcription factors in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Investig Med. 2017;65:926–934. doi: 10.1136/jim-2016-000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]