Abstract

Internal mammary artery graft dissection is a rare condition and is usually caused by iatrogenic complications or mechanical stress. We experienced a case of acute myocardial infarction due to spontaneous internal mammary artery graft dissection that was triggered by emotional stress and was successfully treated by percutaneous intervention using drug-eluting stents. (Level of Difficulty: Beginner.)

Key Words: acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery bypass, dissection

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IMA, internal mammary artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Graphical abstract

Internal mammary artery graft dissection is a rare condition and is usually caused by iatrogenic complications or mechanical stress. We experienced a…

Internal mammary artery (IMA) dissection is a rare condition and could be caused by iatrogenic complications (1,2). Therefore, there are few reports of spontaneous IMA dissection. Here, we present a case of acute myocardial infarction due to spontaneous IMA graft dissection that was triggered by emotional stress and was successfully treated by percutaneous intervention using drug-eluting stents.

Learning Objectives

-

•

Spontaneous IMA graft dissection is one of the causes of acute coronary syndrome in patients with a previous history of CABG.

-

•

Emotional stress as well as the mechanical stress due to physical movement is a possible trigger for spontaneous IMA graft dissection.

-

•

Percutaneous intervention using coronary stents is one of the important treatment options in cases of spontaneous IMA graft dissection.

History of Presentation

A 78-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with sudden onset chest pain immediately after receiving notice of her grandchild's death. Chest pain was relieved by oral nitroglycerin but persisted when she arrived at our hospital. She did not complain of backache or nausea. Her blood pressure on arrival was 150/87 mm Hg and her heart rate was 64 beats/min. Her heart had a regular rhythm; S1 and S2 were normal, and there were no murmurs or gallops. There was no lower extremity edema.

Past medical history

She had been treated for hypertension and dyslipidemia by oral medications. She experienced effort angina and underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) 20 years prior with a left IMA graft to the diagonal branch and saphenous vein grafts to the left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCX), and right coronary artery. The saphenous vein graft to the LCX was occluded immediately after CABG. The LCX was treated by percutaneous coronary intervention using a 2.5 × 28 mm Cypher sirolimus-eluting stent (Cordis Medical, Hialeah, Florida) owing to unstable angina 11 years prior. Furthermore, the saphenous vein graft to the LAD showed occlusion based on angiography performed 1 year prior.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included plaque rupture of the bypass graft, acute coronary syndrome due to plaque rupture, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), very late stent thrombosis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis.

Investigations

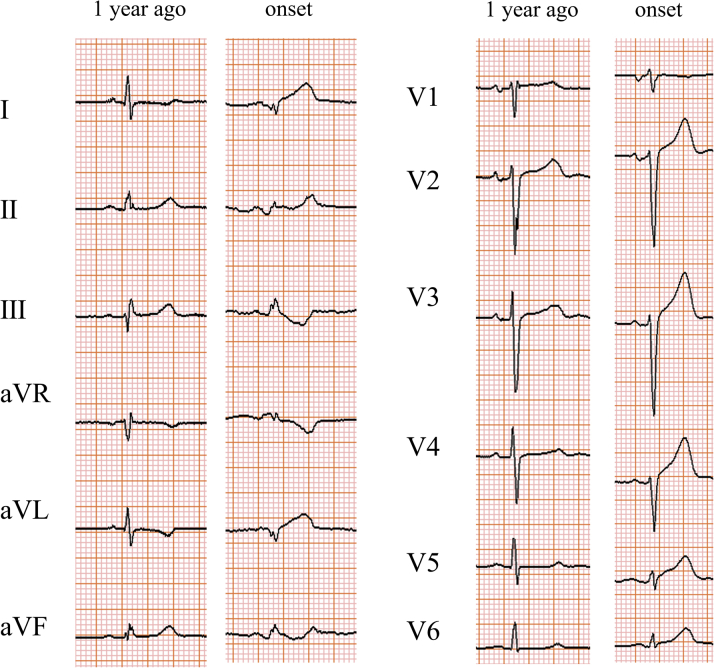

The electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in leads I, aVL, and V2 to V6 (Figure 1). The left ventricular lateral wall was hypokinetic on echocardiography. Troponin T was elevated to 1.06 ng/ml (normal <0.014 ng/ml).

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram

Electrocardiogram from 1 year prior and at the onset.

Management

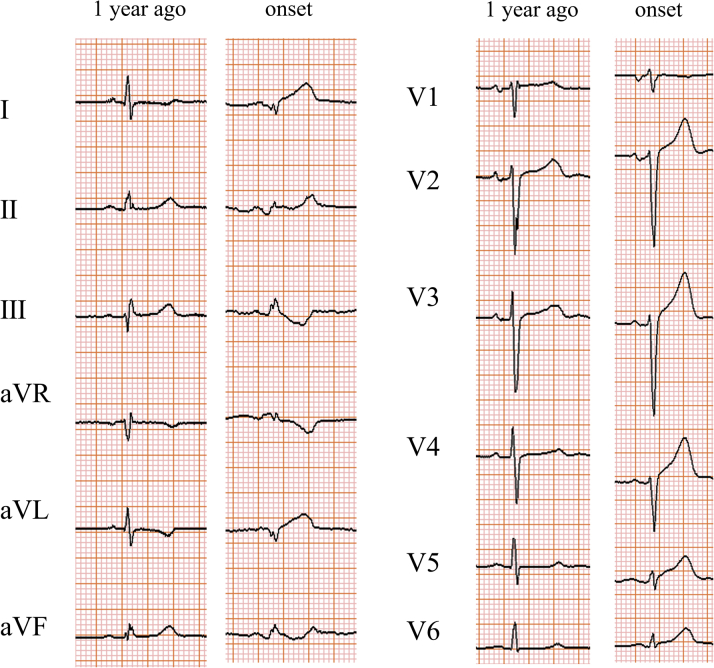

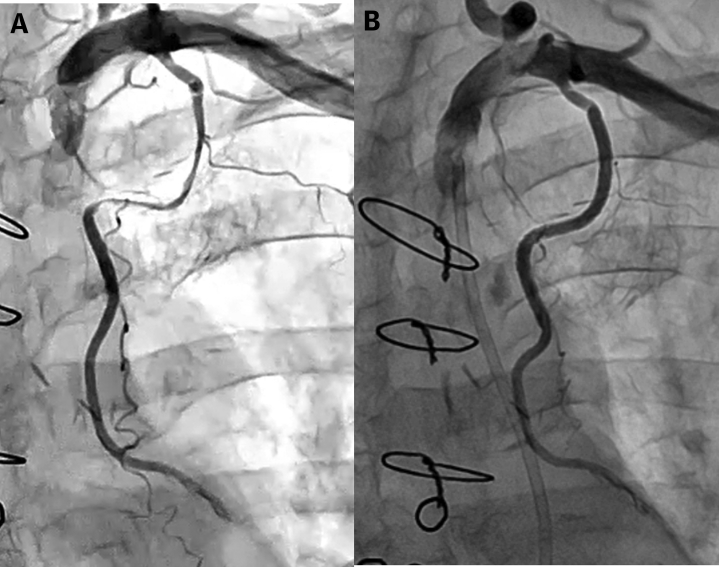

Urgent angiography showed severe stenosis at the mid portion of the left IMA graft with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction flow grade 2, which was not observed 1 year prior (Figure 2). There were no significant changes in the native coronary artery. Therefore, left IMA stenosis was considered to be the culprit lesion and percutaneous intervention was selected for the treatment of this challenging case.

Figure 2.

Angiography of the IMA Graft

(A) Internal mammary artery (IMA) angiography from 1 year ago. (B) IMA graft angiography at the onset with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction flow grade 2.

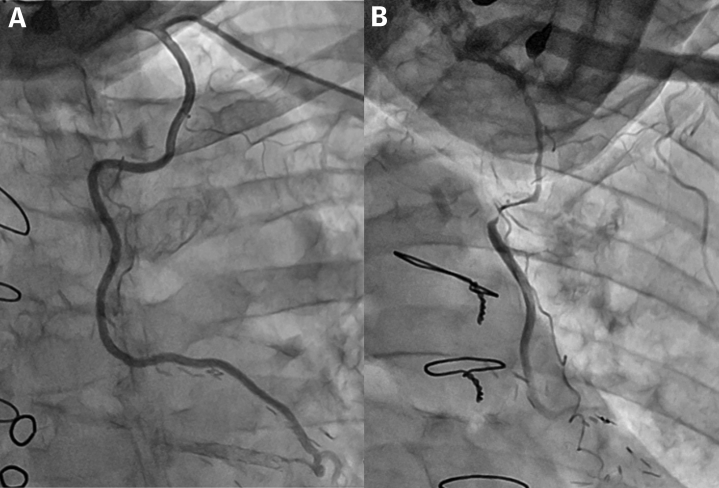

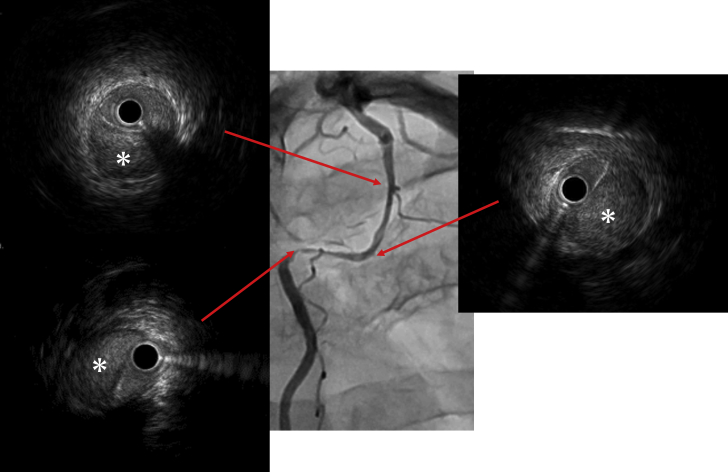

The left radial artery was selected as an approach site, and a 6-F Judkins Right 3.5 guiding catheter (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) was used for the intervention. A SION blue wire (Asahi Intecc USA, Santa Ana, California) did not pass the culprit lesion due to insufficient backup. Therefore, the approach site was changed to the femoral artery, and the wire successfully advanced through the lesion. Intravascular ultrasound revealed dissection with intramural hematoma throughout the stenotic lesion (Figure 3). The intramural hematoma and dissection flap were fully stented using 2 platinum chromium SYNERGY everolimus-eluting stents (2.5 × 38 mm and 2.5 × 12 mm; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts). Final angiography showed good stent expansion with TIMI flow grade 3 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Intravascular Ultrasound Findings

Angiography and intravascular ultrasound findings. Asterisks show intramural hematoma.

Figure 4.

Angiography of the IMA Graft

(A) Internal mammary artery (IMA) graft angiography before percutaneous coronary intervention. (B) IMA graft angiography after percutaneous coronary intervention with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction flow grade 3.

The patient’s symptoms resolved after percutaneous coronary intervention, and the serum creatine kinase increased up to 521 U/l. She was discharged from our hospital on post-operative day 9.

Discussion

IMA graft dissection is considered to be very important condition because of its frequent use for LAD bypass grafting. One of the major causes of IMA graft dissection is iatrogenic complications. Shammas et al. (1) reported a case in which dissection of the IMA graft occurred during diagnostic angiography and was treated successfully with a drug-eluting stent. Spontaneous IMA graft dissection is another cause (2), and it is crucially important, as it can lead to acute coronary syndrome (3, 4, 5, 6). Koyama et al. (7) reported spontaneous dissection of an IMA graft causing acute coronary syndrome and ventricular fibrillation. Although spontaneous IMA graft dissection is not common, we should keep in mind that it could be the cause of acute coronary syndrome or life-threatening arrhythmia in those with previous CABG.

The main cause of spontaneous IMA dissection has been reported to be associated with mechanical stress owing to physical movement (Table 1) (3,4,6). Freixa and Gallo (6) proposed that the shear stress between the chest wall and IMA triggered dissection. In this case, the patient was exposed to emotional stress upon notification of her grandchild's death, and then chest pain occurred. It is possible that emotional stress could have been the cause of IMA dissection in this case. Emotional stress is reported to be a major trigger of SCAD (8). Stress catecholamines could increase the arterial shear stress, resulting in dissection (9). The same mechanism may have caused dissection of the IMA in this case.

Table 1.

Reported Cases of Spontaneous IMA Dissection

| First Author (Ref. #) | Year | Age (yrs) | Sex | Trigger | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wong et al. (3) | 2004 | 69 | M | Digging up a postbox | 4 stents |

| Suresh and Evans (4) | 2007 | 75 | M | Lifting a heavy bookcase | Multiple stents |

| Karabulut and Tanriverdi (5) | 2011 | 59 | F | Kinking of the IMA | CABG |

| Freixa and Gallo (6) | 2013 | 61 | M | Raising arms | 3 stents |

| Koyama et al. (7) | 2015 | 47 | M | No specific trigger | 2 stents |

| Current case | 2019 | 78 | F | Emotional stress | 2 stents |

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; IMA = internal mammary artery.

On the one hand, a conservative strategy is mostly selected in cases of SCAD. Only 14% of patients had percutaneous coronary intervention in the Canadian SCAD cohort study (8). On the other hand, percutaneous intervention using coronary stents is the major treatment strategy for IMA dissection (Table 1) (3,4,6,7). Percutaneous intervention to the IMA is usually challenging because of the acute angle, tortuous course, and small lumen of the IMA. However, balloon angioplasty and stenting of IMA is reported to be safe and effective (10). Although the prior report did not refer to dissection cases, percutaneous intervention could be a valuable treatment option to treat flow-limited IMA dissection cases, considering the risk of reoperation in those with previous CABG. Nevertheless, the dilemma of whether to perform intervention or not remains in the spontaneous IMA dissection. As there was no evidence of any disease 1 year prior, the dissected IMA could have been healed completely without intervention. Furthermore, there is a risk of propagating dissection by the wiring to the false lumen. In this case, intervention was selected due to the ongoing chest pain and flow limitation of IMA. Arrhythmias or hemodynamic instability could also be the indication of intervention for spontaneous IMA dissection.

This case uniquely demonstrates emotional stress as a possible trigger of IMA graft dissection and complements previous case reports demonstrating the role of percutaneous intervention in its management.

Follow-up

The patient did well at 1 month of follow-up in our hospital. Echocardiography showed left ventricular lateral wall motion that was mildly hypokinetic, but it was better than that at the onset.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this could be the first case of spontaneous IMA graft dissection that was triggered by emotional stress and successfully treated by percutaneous intervention.

Footnotes

Dr. Kotooka has served as the endowed chair for Asahi-Kasei Corporation. Dr. Node has received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma; has received research funding from Teijin Pharma, Terumo, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Asahi-Kasei, and Astellas; and has received scholarships from Bayer Yakuhin, Daiichi-Sankyo Healthcare, and Teijin Pharma. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Adhir Shroff, MD, served as Guest Associate Editor for this paper.

Informed consent was obtained for this case.

References

- 1.Shammas N., Karia R. Iatrogenic intramural hematoma identified by intravascular ultrasound following selective angiography of the left internal mammary artery. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2019;1:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan Z., Latif F., Dasari T.W. Internal mammary artery graft dissection: a case-based retrospective study and brief review. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41:653–656. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-13-3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong P., Rubenstein M., Inglessis I. Spontaneous spiral dissection of a LIMA-LAD bypass graft: a case report. J Interv Cardiol. 2004;17:211–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2004.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suresh V., Evans S. Successful stenting of stenotic lesion and spontaneous dissection of left internal mammary artery graft. Heart. 2007;93:44. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.087551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karabulut A., Tanriverdi S. Acute coronary syndrome secondary to spontaneous dissection of left internal mammary artery bypass graft nine years after surgery. Kardiol Pol. 2011;69:970–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freixa X., Gallo R. Internal thoracic artery dissection: a proposed mechanistic explanation. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2013;6:533–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyama K., Yoneyama K., Tsukahara M. A rare case of spontaneous dissection in a left internal mammary artery bypass graft in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2015;8:996–997. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saw J., Starovoytov A., Humphries K. Canadian spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort study: in-hospital and 30-day outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1188–1197. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saw J., Aymong E., Sedlak T. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:645–655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruberg L., Dangas G., Mehran R. Percutaneous revascularization of the internal mammary artery graft: short- and long-term outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:944–948. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]