Graphical abstract

Key Words: cardiotwitter, case reports, social media, twitter

“Always note and record the unusual … When you have made and recorded the unusual or original observation … publish it.”

—Sir William Osler (1849–1919) (1)

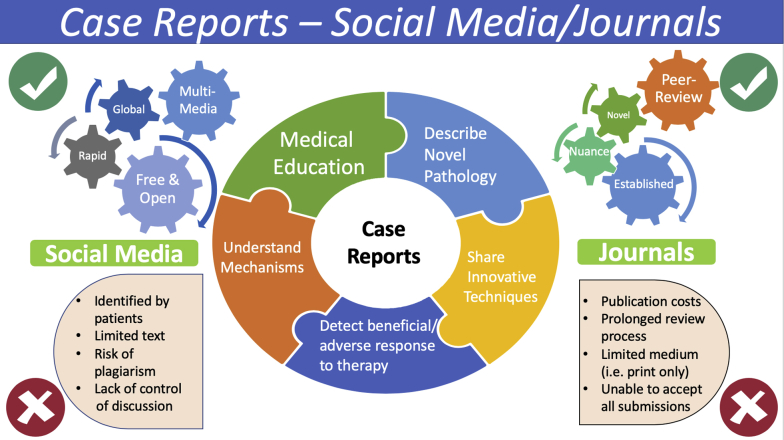

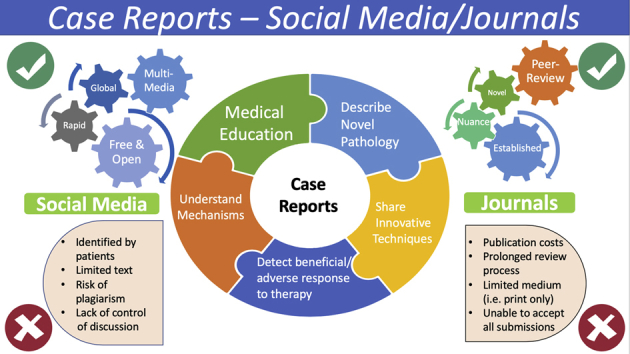

In Sir William Osler’s time, new anecdotal knowledge in medicine was delivered through lectures, the published medium, and telegraph communications, where propagation of knowledge was limited to the privileged few with access to these resources. Could Dr. Osler have imagined the rapidity of global digital, mobile, and multimedia medical communications 100 years after he died? Published case reports have served as a scientific tool to advance our knowledge of rare diseases, recognizing new or unusual disease forms and their presentation, treatments, and clinical outcomes since the time of Hippocrates. Over the past 10 years alone, over 590,000 case reports have been published in PubMed-indexed journals. However, case reports published in this traditional format have several limitations. They are typically relegated to the lowest level of importance as single observations that may not be generalizable, offer limited ability to incorporate pertinent multimedia presentations, and most importantly are limited in their ability to provide a forum for interactive case discussions between colleagues and across specialties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pros and Cons of SoMe vs. Medical Journals

Pros and cons of publishing case reports on social media (SoMe) versus in medical journals.

In contrast, discussion of clinical cases is among the most impactful use of social media (SoMe) by clinicians, overcoming many of the limitations of the traditional journal format. This paper aims to discuss how the paradigm of case reports in cardiovascular (CV) medicine has changed through SoMe by discussing best practices (including respect for patient confidentiality) and opportunities for future advancement.

Journals and Case Reports: Traditional Approach

The traditional approach to publishing cases includes a vigorous peer-review process and selection of cases that are truly rare, novel, or that articulate previously unknown mechanisms of CV disease (Figure 1). Whereas learning from cases is foundational to a clinician’s daily practice, published cases reports often focus around rare manifestations of common disease or rare disease entities that may have little relevance to the practicing clinician in helping them guide the management of complex patients. Furthermore, such reports are often considered to be at the bottom of the evidence hierarchy and are rarely published in widely read journals. As journals focus mainly on the research community, case reports are seldom cited, causing a cycle of missed opportunities for lifelong students of medicine to appraise and therefore enable application of the knowledge derived from such cases for future clinical care.

Case Discussion on Social Media: A New Paradigm

Free open access to medical education

SoMe platforms particularly Twitter (#cardiotwitter) have rapidly gained prominence as an indispensable, free, and open access platform for the delivery of medical education (#FOAMed). Online participants engage in meaningful discussions on challenging cases, share personal or institutional experiences, and highlight the effective use of novel approaches in health care delivery. SoMe educators often utilize a case-based format, collaborating effectively in discussing state of the art diagnostic and treatment strategies with a global audience.

Interesting, challenging, and rare cases can be posted from anywhere in the world and can be viewed by anyone on SoMe. Twitter has become a rich repository of angiograms, echocardiograms, and other CV imaging modalities. The CV community has developed specialty or disease-specific hashtags to link this repository together, thereby creating an opportunity to crowdsource approaches to difficult scenarios in which evidence may be uncertain. Clinician educators on SoMe, however, often link references, appropriate use criteria, and diagnostic pathways through an illustrative case discussion. The rich peer-to-peer discussion around a particular case allows for virtual education and enhances the practice of evidence-based medicine. Importantly, SoMe lets this education permeate freely through the volunteer efforts of clinicians, allowing dissemination of knowledge to parts of the world that may not otherwise have access to traditional journals or have the financial resources to attend national and international scientific meetings.

Social media and adoption of technique

Benjamin Franklin once wrote “tell me and I forget, teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn” (2). Techniques in the CV community often have a steep learning curve and require interactive involvement between teacher and learner. Whereas a print journal alone may inform readers about a new technique, SoMe allows for active engagement to allow others to learn and adopt the technique. The best example of crowdsourced case-based education is use of SoMe to enhance radial cardiac catheterization use, captured through the hashtag #RadialFirst and more recently left distal transradial access (#ldTRA). #ldTRA was described in 2011 (3) but its more widespread adoption was when it was introduced on SoMe in a single case-based format describing the steps of the technique in 2017.

Multispecialty discussion

Given the complexity and heterogeneous presentation of CV diseases, SoMe harnesses global expertise by allowing individual clinicians from different CV subspecialties the opportunity to interact and facilitate case-based discussion and education. These discussions support the advancement of CV medicine by enhancing the utilization of a broad knowledge landscape promoting the common goal of improving the treatment of CV disease encountered daily by the practicing clinician.

Measuring case impact

Traditionally, a CV journal has measured impact through its journal impact factor, which may fail to analyze the impact of an article on a journal’s readership, particularly for article types such as case reports that are seldom cited. In contrast, SoMe allows for a number of ways to assess its global impact through an analysis of engagement, digital impressions, and news mentions. The Altmetric attention score is a commonly used measure for early and real-time impact analysis prior to the accrual of citations and has been associated with increased paper downloads and a neutral to positive effect on citations (4). Published cases often have the highest online engagement as measured in shares, retweets, and direct interactions with the tweet that are not readily apparent by focusing on citations. This is most likely due to an appealing multimedia presentation, accessible nature of the content, and perceived value to the clinician. The original investigators of a work, the journal itself, and SoMe physician users help to generate a high-quality discussion on SoMe, thus further advancing the dissemination and impact of a specific case report.

SoMe intervention and engagement has been linked to more article downloads and higher Altmetric attention score with medical journals embracing strategies to improve their performance on SoMe (5). Dedicated SoMe teams that are part of the editorial board are increasingly utilized and are made up of multigenerational members that appeal to the diverse user base on different SoMe platforms. Since its launch, JACC: Case Reports has harnessed SoMe to enhance and build on its published content. #JACCCaseReports is a journal hashtag used by @JACCJournals on SoMe to promote interactive learning and house a dynamic forum for interactive discussions that focus around widely peer-reviewed case reports published in this open access journal.

Increasing Engagement for Case Discussion

How does the CV clinician effectively harness SoMe engagement? One of the keys to engaging the audience is by posting clinically relevant questions in a case-based format that summarizes the interesting and pertinent aspects of a clinical case using multimedia modalities. For the clinician-educator, SoMe serves as an outlet to cultivate multimedia educational tools and to refine teaching methodology.

A few suggestions follow.

Images

Images can be in the form of a central illustration, figures, slides, or a case image. In the era of rapidly developing multimodality cardiac imaging, exposure to different techniques or modalities during the case discussion that the clinician may not be familiar with provides a unique educational opportunity and drives engagement.

Central illustration

The concepts of a central illustration and visual abstract were developed to provide a visual summary of key findings of an article to be understood within seconds. Central illustrations and visual abstracts result in dramatically increased engagement when compared with text-only case posts.

Polls

The use of a poll format allows for different options for investigating or treating a case to be presented and discussed in a real-time basis with comments, links to reference papers, and guidelines, as well as highlighting relevant personal experiences pertaining to that case.

Tweetorials

SoMe #tweetorials, are a short series of multimedia tweets containing clinical bullet point educational content centered on a particular topic. Often, the #tweetorials are structured in an interactive fashion with polls to prompt participation, stepwise revelation of diagnostic clues, and opportunities for questions and feedback.

Some educators have compiled multimedia slides into a GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) or Twitter Moments to deliver teaching points.

Best practices

Whereas the benefits of SoMe for interactive case discussion, education, and collaborations are undeniable, the benefits must be weighed against respect for patient privacy. It is important to remember that legal and ethical issues of patient privacy govern the use of patient data in such public forum.

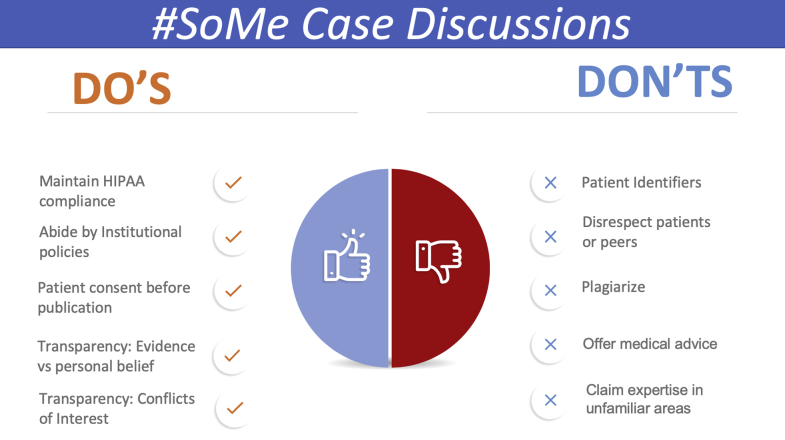

In the authors’ opinion, the following 6 recommendations constitute best practice around case discussions on SoMe (Figure 2).

-

1.Before posting a clinical vignette, make sure the post is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. It is important to remember that, according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, deidentifying the protected health information of cases is not enough to prevent the identification of the patient (6). Therefore:

-

•Avoid contemporaneous posting;

-

•Be careful with rare presentations as they may be easily identifiable.

-

•

-

2.

Abide by institutional codes of conduct.

-

3.

Procure written or verbal consent(s) from patients to use their clinical information for educational purposes.

-

4.

Be respectful when posting about patient complications. Comments or emojis shared within the posting should reflect the respect and devotion to patient care.

-

5.

Maintain professionalism and decorum. Scientific ideas and concepts in medicine are traditionally debated at national meetings among colleagues. Aggressive or demeaning conversations on #SoMe while debating case-based diagnostic pathways or management plans may taint the physicians, their institutions, and the wider medical community’s reputation, in addition to offending and confusing patients (7). Act in a way as you would do in a scientific congress surrounded by your peers.

-

6.

Avoid plagiarism. As with any publication format, plagiarism whether intentional or otherwise must be avoided because this can taint the reputation of a SoMe physician among the colleagues.

Figure 2.

Best Practices of Case Discussions on SoMe

Recommendations regarding best practices around case discussions on social media (SoMe). HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

The different SoMe platforms have their own system of reporting unacceptable behaviors or postings; physician users should get familiar with them.

Limitations of Case Discussion on SoMe

Although online cases have the significant potential for learning, SoMe provides no quality checks for the cases being shared for their suitability for providing a learning opportunity, the appropriateness of the management strategy employed, and whether it is in line with internationally accepted, guideline-recommended best practices. The crowdsourcing of case discussions around such SoMe cases can be limited to the biased opinion of the posters and SoMe educators and may lack the granularity of cases published in more traditional media. Voices heard through SoMe are important; however, the absence of a moderator in the virtual world may facilitate the dissemination of non-evidence-based practice, which can adversely affect patient outcomes (Figure 1). There is information overload with anecdotal experiences shared on SoMe that can change medical practice negatively, particularly when not in line with guideline recommendations of international societies that are evidence-based and have gone through multiple levels of peer review by experts in the field. It is advisable to use the knowledge gained from SoMe as a supplement to a detailed review of the publications on the subject and to augment practice recommended through societal guidelines and evidence base.

Future and Conclusions

Knowledge in CV medicine is accumulating more quickly than the current traditional infrastructure available to harness it. Important areas for development will include quantification of a physician’s continuing medical education through provision of continuing medical education credits for virtual case-based education as well as a structured means of archiving and accessing this content instantaneously.

Since the time of Hippocrates, clinical cases have been used to describe clinical manifestations of the disease process and provide a means through which education can be delivered and experiences shared. SoMe, through the innovative use of multimedia resources, facilitates rich peer-to-peer case-based discussions providing a platform for virtual education that enhances the practice of evidence-based medicine through a crowdsourced global education. It is important for the CV community to establish appropriate standards to protect the patient-physician relationship, maintain patient privacy, and yet allow for SoMe education from the atypical scenarios, novel mechanisms, case-based applications of guidelines and research to everyday practice, and fortuitous responses to therapy. As the best use of these educational platforms is rapidly evolving, best practice recommendations should be equally responsive to this ever-changing landscape.

Footnotes

Dr. Parwani serves as a social media consultant for the Journal of American College of Cardiology. Dr. Choi serves as a social media editor for JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. Dr. Chamsi-Pasha serves as a social media consultant for JACC: Case Reports. Dr. Vidal-Perez serves as a social media director for JACC: Case Reports. Dr. Mamas serves as a social media editor for the European Society of Cardiology.

References

- 1.Abu Kasim N, Abdullah B, Manikam J. The current status of the case report: terminal or viable? Biomed Imaging Interv J 2009;5:e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.van der Molen J.W., Peijs J. Tell me and I’ll forget - Show me and I may remember - Involve me and I’ll understand: learning from educational software versus traditional instruction. Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap. 2009;37:274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babunashvili A., Dundua D. Recanalization and reuse of early occluded radial artery within 6 days after previous transradial diagnostic procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:530–536. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barakat A.F., Nimri N., Shokr M. Correlation of Altmetric attention score with article citations in cardiovascular research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:952–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widmer R.J., Mandrekar J., Ward A. Effect of promotion via social media on access of articles in an academic medical journal: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2019 May 28 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002811. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parwani P., Choi A.D., Lopez-Mattei J. Understanding social media: opportunities for cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells D.M., Lehavot K., Isaac M.L. Sounding off on social media. Acad Med. 2015;90:1015–1019. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]