Abstract

Background

The coverage of postpartum care is not ideal, and has not been used very well due to not enough attention being paid to the puerperal women and newborns, especially in developing countries. Practice guidelines on postpartum care provide beneficial practice guidance and help to reduce maternal mortality. However, little is known about the credibility and consistency of those guidelines. This systematic review was conducted to summarize main postpartum care indications and appraise methodological quality of guidelines.

Methods

Seven literature databases and guideline development institutions and organizations of obstetrics and maternity care were searched. Two reviewers independently assessed guideline quality using the AGREE II instrument, and synthesized consistent and non-consistent recommendations using the content analysis approach.

Results

Twenty-nine guidelines were included and a total of eight postpartum care indications were identified. Most guidelines focused on care indications and interventions including exclusive breastfeeding, maternal nutrition, home visit, infant or newborn care and sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing. However, indications such as pain or weight management, pelvic floor muscle training, abdominal rehabilitation, and mental health got less attention. Additionally, the overall quality of all involving postpartum care guidelines is relatively good and acceptable.

Conclusions

Guidelines developed by NICE, RANO, and WHO indicated higher methodological quality. For postpartum care indications, most guidelines are incomplete. Variation in practice guidelines for postpartum care recommendations exists. In the future, implementation research into shared decision-making, as well as further high-quality research to broaden the evidence base for postpartum care indications is recommended.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10389-021-01629-4.

Keywords: Practice guidelines, Postpartum care, Methodological quality, Systematic review

Introduction

The postnatal period, just after delivery and through the first 6 weeks (42 days) of life, is recognized as a critical time for both mothers and newborns (WHO et al. 2018). Postpartum women and their newborns during the postnatal period are more vulnerable to various physiological, psychological, and social problems, especially within 24 h of birth (WHO 2017; Zhen Xiuxia 2012), which poses a great threat to maternal and newborn health. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) reports that a lack of opportunities to promote healthy behaviors during the postpartum period can lead to maternal and newborn disability or death. Specific maternal mortality or morbidity data relating to the postnatal period is limited. However, the global estimates for the year 2017 indicate that there were 295,000 maternal deaths (WHO et al. 2019). The majority of these deaths occur in the postnatal period, with postpartum haemorrhage the most common cause of maternal death (Say et al. 2014). Additionally, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, newborns were at highest risk of death. In 2019, a newborn baby died every 13 s (WHO 2020). With severe disruptions in essential health services, newborn babies could be at much higher risk of dying; for example, in Cameroon, where one out of every 38 newborns died in 2019 (WHO 2020). In 2021, a survey conducted over the summer across 77 countries found that almost 68% of countries reported at least some disruption in health checks for children and immunization services. In addition, 63% of countries reported disruptions in antenatal checkups and 59% in postnatal care (UNICEF 2021).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), especially Sustainable Development Goal number 3 (SDG-3) aim to reduce the neonatal and maternal mortality ratio to less than 12 per 1000 live births and 70 per 100,000 live births respectively by 2030 (UN General Assembly 2015; WHO 2020). However, the postnatal period is a neglected phase of maternity care, with more emphasis and resources placed on antenatal and intrapartum care; enough attention has still not been paid to postpartum women and newborns, especially in developing countries (Adane et al. 2020; Sacks and EV 2016). More and more decision-makers call for measures to be taken to reduce morbidity and mortality of maternal and newborns during the postnatal period, and then propose the concept of full postpartum care. As one of the key components of the “continuum of care” for women and babies and preventive health service, full postpartum care can be defined as preventive care practices and assessments that are designed to identify and manage or refer complications for both mothers and newborns (Langlois et al. 2015). Specifically, comprehensive postpartum care is based and focused on maximizing maternal and newborn health and wellbeing, which contains routine maternal- and infant-care services together with special care for newborns. Postnatal contacts provide an opportunity for healthcare providers to facilitate healthy breastfeeding practices, screen for postpartum depression, monitor the infant’s growth and overall health status, treat newborn/infant-related complications, counsel women about their family planning options, and refer the mother and baby for specialized care if necessary (NICE 2021b; WHO 2013). In 2013, WHO recommended that a mother and her newborn child should receive postpartum care within 24 h of the birth and then at least three more times, including at least on day three after the birth, in the second week after the birth and 6 weeks after the birth (WHO 2013). In order to implement and improve postpartum care services, financial incentives have been encouraged in public health to motivate behaviour change, for example exclusive breastfeeding in the postpartum period (Thomson et al. 2012). One small-scale, gift-based incentive for breastfeeding was generally positively received by women and peer supporters, who perceived it as rewarding, valuing them for breastfeeding (Johnson et al. 2018). However, according to the recent ‘Countdown to 2030’ report, full postpartum care services have the lowest median national coverage of interventions on the continuum of maternal and child healthcare, which is associated with lack of education, poverty, and limited access to health-care facilities, especially in low- and middle-income countries (UNICEF & WHO 2021).

The practice guidelines are of the highest quality of evidence level according to the 6S hierarchy of evidence pyramid (Dicenso et al. 2009). Although evidence-based guidelines are being developed to bridge the gap between research and routine practice, with the goals of changing and improving health care quality (Flodgren et al. 2016), they are inconsistent in application (Campbell et al. 2006; Wiercioch et al. 2020). In recent years, postpartum care guidelines have been issued in many international and national organizations, which aimed to provide evidence-based recommendations for the management of postpartum women and their newborns health. However, little is known about the content and consistency of postpartum care guidelines. To address these gaps, we use systematic review methods to summarize the main postpartum care indications and appraise methodological quality of guidelines, with a view to provide guidance for health care professionals and primary caregivers who are involved in the care of puerperal women and their newborns or infants, and thereby to reduce unnecessary maternal and newborn disability or death.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) criteria (Moher et al. 2009). The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020220890). The search was conducted between January 1st 2010 and May 20th 2021 in guideline and electronic databases, including Guidelines International Network (GIN), National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), World Health Organization (WHO), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario(RNAO), Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, CNKI, WanFang, SinoMed, and VIP. In addition, supplementary searches were also performed, such as forward and backward citation chasing or searching the reference lists of the related guidelines.

Guidelines were also searched from websites of key national authorities in obstetrics and gynecology, specifically including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Collège national des gynécologues et obstétriciens francais (CNGOF), Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (EBCOG) and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), Chinese Maternal and Child Health Association (CMCHA), and National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHFPC).

Lots of search strategies were adopted to identify guidelines. Search terms used were ‘postpartum care’, ‘postpartum period’, ‘postnatal period’, ‘postnatal care’, ‘breastfeeding’, ‘home visit’, ‘health visiting’, ‘infant care’, ‘newborn care’, ‘maternal nutrition’, ‘mental health’, ‘pelvic floor muscle training’, ‘abdominal rehabilitation’, ‘contraception’, ‘birth spacing’, ‘postpartum pain’, ‘domestic care’ for guideline databases and websites of key national authorities in obstetrics and maternity care, combined with the terms ‘guideline*’, ‘guidance*’, ‘recommendation*’, ‘consensus*’, ‘ best practice*’, ‘statement*’, ‘standard*’ for electronic databases. The detailed search strategies are provided in Table 1. Initial screening of search results, identification of eligible guidelines, and data extraction were conducted by two reviewers independently. A third reviewer checked data for errors and negotiated disagreements through discussions.

Table 1.

Database searches of guidelines

| Database | Search strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | #1 ((((postnatal care[MeSH Terms]) OR (postpartum care[MeSH Terms]) OR (postnatal period [MeSH Terms]) OR (postpartum period [MeSH Terms) | 72,810 |

| #2 ((((((((((((breastfeeding[Title]) OR (home visit[Title])) OR (infant care[Title])) OR (newborn care[Title])) OR (maternal nutrition[Title])) OR (mental health[Title])) OR (pelvic floor muscle training[Title])) OR (abdominal rehabilitation[Title])) OR (contraception[Title])) OR (birth spacing[Title])) OR (postpartum pain[Title]) OR (domestic care [Title]) OR (health visiting [Title]) | 87,536 | |

| #3 #1 OR #2 | 157,382 | |

| #4 ((((((guideline*[Title]) OR (guidance*[Title])) OR (recommendation*[Title])) OR (consensus*[Title])) OR (best practice*[Title])) OR (statement*[Title])) OR (standard*[Title]) | 276,967 | |

| #5 ((((guideline[Publication Type]) OR (guideline as topic[MeSH Terms])) OR (consensus development conferences as topic[MeSH Terms])) OR (consensus development conferences[Publication Type])) OR (stand of care[MeSH Terms]) | 38,533 | |

| #6 #4 OR #5 | 290,050 | |

| #7 #3 AND #6 | 2101 | |

| #8 #7 Filters: Publication date from 2010/01/01 to 2021/05/20 | 1150 | |

| Cochrane Library | #1 MeSH descriptor: [Postnatal care] explode all trees | 424 |

|

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Postpartum period] explode all trees #3 (postpartum care):ti OR (postnatal period):ti |

1686 5094 |

|

| #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 | 5310 | |

| #5 (breastfeeding):ti OR (home visit):ti OR (infant care):ti OR (newborn care):ti OR (maternal nutrition):ti OR (mental health):ti OR (pelvic floor muscle training):ti OR (abdominal rehabilitation):ti OR (contraception):ti OR (birth spacing):ti OR (postpartum pain):ti OR (domestic care):ti OR (health visiting):ti | 95,617 | |

| #6 #4 OR #5 | 98,101 | |

| #7 MeSH descriptor: [Guidelines as Topic] explode all trees | 1920 | |

| #8 MeSH descriptor: [Consensus Development Conferences as Topic] explode all trees | 8 | |

| #9 MeSH descriptor: [Consensus Development Conferences] explode all trees | 0 | |

| #10 (guideline):ti OR (guidance*):ti OR (recommendation*):ti OR (consensus*):ti OR (best practice*):ti OR (statement*):ti OR (standard*):ti | 275,110 | |

| #11 #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | 275,112 | |

| #12 #6 AND #11 | 28.507 | |

| #13 #12 with Cochrane Library publication date from Jan 2010 to May 2021 | 856 | |

| Embase | #1 ‘postnatal care’/exp./mj | 40,789 |

| #2 ‘postnatal care’:ti OR ‘postpartum period’:ti OR ‘postnatal period’:ti | 3.311 | |

| #3 #1 OR #2 | 42,383 | |

| #4 ‘breastfeeding’:ti OR ‘home visit’:ti OR ‘infant care’:ti OR ‘newborn care’:ti OR ‘maternal nutrition’:ti OR ‘mental health’:ti OR ‘pelvic floor muscle training’:ti OR ‘abdominal rehabilitation’:ti OR ‘contraception’:ti OR ‘birth spacing’:ti OR ‘postpartum pain’:ti OR ‘domestic care’:ti OR ‘health visiting’:ti | 101,320 | |

| #5 #3 OR #4 | 142,163 | |

| #6 ‘practice guideline’/exp./mj | 101,767 | |

| #7 ‘guideline’:ti OR ‘guidance*’:ti OR ‘recommendation*’:ti OR ‘consensus*’:ti OR ‘best practice*’:ti OR ‘statement*’:ti OR ‘standard*’:ti | 276,318 | |

| #8 #6 OR #7 | 354,566 | |

| #9 #5 AND #8 | 2558 | |

| #10 #9 AND [2020/01/01]/sd NOT [2021/05/20]/sd | 1563 | |

| CNKI |

#1 主题 (产后保健 OR 产后护理 OR 产后) #2 主题 (指南 OR 共识 OR 规范 OR 推荐 OR 指导 OR 最佳实践) #3 #1 AND #2 #4 #3 发表时间:从2010 年至2021 |

15,543 3,863,666 558 534 |

| VIP | #1 (((题名或关键词 = 产后保健 OR 题名或关键词 = 产后护理) OR 题名或关键词 = 产后) | 64,430 |

| #2 (((((题名或关键词 = 指南 OR 题名或关键词 = 共识) OR 题名或关键词 = 规范) OR题名或关键词 = 推荐) OR 题名或关键词 = 指导) OR 题名或关键词 = 最佳实践) | 846,872 | |

| #3 #1 AND #2 | 374 | |

| #4 #3 发表时间:从2010 年至2021 | 366 | |

| WanFang | #1 (题名或关键词:(“产后保健”) + 题名或关键词:(“产后护理”) + 题名或关键词:(“产后”)) | 85,332 |

| #2 (题名或关键词:(“指南”) + 题名或关键词:(“共识”) + 题名或关键词:(“规范”) + 题名或关键词:(“推荐”) + 题名或关键词:(“指导”) + 题名或关键词:(“最佳实践”)) | 832,149 | |

| #3 #1 AND #2 | 993 | |

| #4 #3 发表时间:从2010年至2021 | 857 | |

| SinoMed | #1 “产后保健”[标题:智能] OR “产后护理”[标题:智能] OR “产后”[标题:智能] | 49,713 |

| #2 (((((“指南”[标题:智能]) OR “共识”[标题:智能]) OR “规范”[标题:智能]) OR “推荐”[标题:智能]) OR “指导”[标题:智能]) OR “最佳实践”[标题:智能] | 80,719 | |

| #3 #1 AND #2 | 313 | |

| #4 #3 发表时间:从2010年至2021 | 310 |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

National and international English- or Chinese-language postpartum care guidelines with at least one recommendation were included. Given that most guidelines were updated within a 10-year period, and that guidelines produced more than 10 years before were very likely to be out of date (Zhao Yang et al. 2019), we only considered guidelines published between 2010 and 2021. Also, we excluded guidelines that met at least one of the following criteria: (a) repeated published guidelines, (b) old versions, (c) guideline protocols, and (d) only comments or review without any recommendations.

Data extraction and evidence summary

The following data from all included guidelines were independently extracted by two reviewers: title, published year, guideline group, country or region, short name. In addition, we adopted the content analysis approach to analyze the included postpartum care guidelines (Downe-Wamboldt 1992). Two reviewers extracted all the main themes or aspects from each guideline into predetermined data collection forms and identified them. Then postpartum care indications and measures among the guidelines were categorized, summarized, and analyzed. The number of guidelines that encouraged main indications twice or more was calculated as the statistical index. A third reviewer checked data for errors and negotiated disagreements through discussions during the whole process.

Quality evaluation

We used the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) Instrument for the evaluation of each guideline (AGREE Next Steps Consortium 2017). The AGREE II Instrument is a valid and reliable tool for evaluating the quality of guidelines, which includes 23 items within six domains; scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development; clarity and presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Each item of an individual domain is graded on a 7-point scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two assessors independently appraised each item of each guideline. Standardized guideline domain scores are calculated by summing all the scores of individual items in a domain, and then the scaled domain score is presented as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain.

The quality assessment of all included practice guidelines was performed by two reviewers independently. Agreement between each reviewer’s scores was tested using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for each domain across all guidelines. The degrees of agreement were graded as minor (≤ 0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80) and almost perfect (≥ 0.81) (Zhao Yang et al. 2019) .

Results

Systematic search results

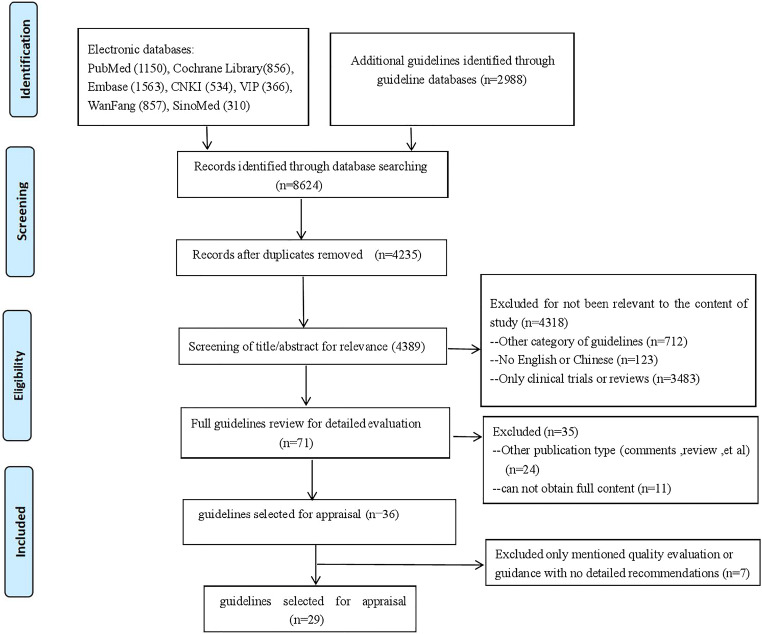

The overall search yielded a total of 8624 records from the seven databases and website sources, and a total of 4235 duplicate articles were removed by using EndNote software. After screening the references, 4318 articles were excluded owing to the abstracts and titles not being relevant to this study. Full texts of the remaining 71 articles were assessed for eligibility. After a careful review, a total of 29 guidelines were found to be suitable for inclusion in our study (AAP 2017; ACOG 2018a, b, c; 2012; 2017; CNS 2016; FSRH 2020; Marangoni et al. 2016; NHMRC 2012, 2013; Sénat et al. 2016; NICE 2014a, 2014b; 2010a, 2010b;2021a, 2021b; 2019; 2016; NHFPC 2011, 2015; Patnode et al. 2016; RANO 2018; WHO 2013; 2015; 2011a, 2011b; 2016). The overall systematic process conducted for the guideline selection is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The search and selection guidelines used for the analysis

Characteristics of included guidelines

Table 2 presents the characteristics of included guidelines. The minority (34%) of the guidelines were published within the latest 3 years. Among the 29 guidelines, 24 (83%) were published by national institutions of obstetrics and gynecology, and the remaining five by the international organization. Two guidelines were from Australia (NHMRC 2012, 2013) one from France (Sénat et al. 2016), one from Canada (RANO 2018), nine from the UK (NICE 2014a, 2014b; 2010a, 2010b; 2021a, 2021b; 2016; 2019; FSRH 2020), one from Italy (Marangoni et al. 2016), three from China (NHFPC 2011, 2015; CNS 2016), and seven from the USA (ACOG 2018a, b, c, 2012, 2017; Patnode et al. 2016; AAP 2017).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included guidelines

| Country/region | Guideline group | Short name | Title | Published year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | National Health and Medical Research Council | NHMRC | Infant feeding guidelines: information for health workers | 2012 |

| France | Collège national des gynécologues et obstétriciens francais | CNGOF | Postpartum practice: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians | 2016 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Vitamin D: supplement use in specific population groups (PH56) | 2014 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance | 2014 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth | 2010 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Weight management before, during and after pregnancy | 2010 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Neonatal infection: antibiotics for prevention and treatment | 2021 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Long-acting reversible contraception | 2019 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Postnatal care | 2021 |

| UK | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | NICE | Jaundice in newborn babies under 28 days | 2016 |

| UK | Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare | FSRH | Contraception after pregnancy | 2020 |

| Italy | Marangoni et al | – | Maternal Diet and Nutrient Requirements in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. An Italian Consensus Document | 2016 |

| China | The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China | NHFPC | Work standards for pregnancy and postnatal care | 2011 |

| China | The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China | NHFPC | National food safety standards: nutritional supplements for pregnant and breastfeeding women | 2015 |

| China | Chinese Nutrition Society | CNS | Dietary guidelines for lactating women | 2016 |

| USA | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | ACOG | Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG Committee Opinion No 736. | 2018 |

| USA | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | ACOG | Lead screening during pregnancy and lactation. ACOG Committee Opinion No 533. | 2012 |

| USA | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | ACOG | Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. ACOG Committee Opinion No 722. | 2017 |

| USA | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | ACOG | Optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No 756. | 2018 |

| USA | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | ACOG | Postpartum pain management. ACOG Committee Opinion No 742. | 2018 |

| Canada | Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario | RANO | Breastfeeding--promoting and supporting the initiation, exclusively, and continuation of breastfeeding for newborns, infants, and young children | 2018 |

| International | World Health Organization | WHO | WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn | 2013 |

| International | World Health Organization | WHO | Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice (3rd edition) | 2015 |

| USA | US Preventive Services Task Force | USPSTF | Primary care interventions to support breastfeeding | 2016 |

| USA | American Academy of Pediatrics | AAP | The American Academy of Pediatrics breastfeeding guidelines (2nd edition) | 2017 |

| International | World Health Organization | WHO | Vitamin A supplementation in postpartum women | 2011 |

| International | World Health Organization | WHO | Iron supplementation in postpartum women | 2016 |

| International | World Health Organization | WHO | Vitamin A supplementation in infants 1–5 months of age | 2011 |

| Australia | National Health and Medical Research Council | NHMRC | Australia dietary guideline | 2013 |

Postpartum care indications and recommendations for care interventions

As outlined in Table 3, guidelines were developed with a focus on eight postpartum care indications: exclusive breastfeeding (n = 11), home visit (n = 6), infant or newborn care (n = 6), mental health (n = 6), pain or weight management (n = 3), maternal nutrition (n = 12), sexuality, contraception ,and birth spacing (n = 8) ,and pelvic floor muscle training and abdominal rehabilitation (n = 2). Additionally, only one guideline (NICE 2021b) involved eight postpartum care indications, two guidelines (WHO 2013, 2015) focused on five care indications, three guidelines (NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016; NHFPC 2011) focused on four care indications, two guidelines (ACOG 2018a; RANO 2018) focused on three care indications, one guideline (ACOG 2018b) focused on two care indications, and 20 guidelines focused on one care indication.

Table 3.

Main indications of postpartum care guidelines

| Exclusive breastfeeding | Home visits |

Infant & newborn care |

Mental health |

Pain & weight management |

Maternal nutrition |

Sexuality & Contraception & birth spacing |

Pelvic floor muscle training & abdominal rehabilitation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start time & frequency |

Optimal duration |

Benefits | Influenced factors |

Complications & treatment |

Maternal illnesses |

Substance use |

||||||||

| NHMRC (2012) | M | M | – | M | M | M | M | – | M | M | – | M | – | – |

| Sénat et al. (2016) | – | M | M | – | M | – | M | M | – | – | – | – | M | M |

| NICE (2014a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| NICE (2014b) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – |

| NICE (2010a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NICE (2010b) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – |

| NICE (2021a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – |

| NICE (2019) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – |

| NICE (2021b) | – | – | – | – | M | – | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| NICE (2016) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – |

| FSRH (2020) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – |

| Marangoni et al. (2016) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| NHFPC (2011) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | M | M | – | M | – | – |

| NHFPC (2015) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| CNS (2016) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| ACOG (2018a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | M | – | – | M | – |

| ACOG (2012) | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ACOG (2017) | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ACOG (2018b) | M | M | M | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – |

| ACOG (2018c) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – |

| RANO (2018) | M | M | – | M | M | – | M | – | M | – | – | – | – | – |

| WHO (2013) | – | M | M | – | – | – | – | M | M | M | – | – | M | – |

| WHO (2015) | M | M | M | – | M | M | M | M | M | – | – | M | M | – |

| Patnode et al. (2016) | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AAP (2017) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| WHO (2011a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| WHO (2016) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| WHO (2011b) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | M | – | – |

| NHMRC (2013) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

M: mentioned in the guideline; –:not mentioned in the guideline; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; FSRH, Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare; NHFPC, The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China; CNS, Chinese Nutrition Society; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; RANO:Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario

In addition, Table 5 summarizes 66 recommendations, which were divided into 20 topics. Of these, we found that the main recommendations included: (1) the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding should preferably be the first 6 months, (2) exclusive breastfeeding reduces the newborn’s incidence of various infectious diseases, (3) avoid smoking, drinking, and illegal drugs when breastfeeding, (4) conduct basic postpartum care including maternal physical well-being, breastfeeding status, family social status, emotional support, and provision of maternal sexual and contraceptive guidance, (5) take measures to assess the emotional state of maternity during postnatal visit, (6) health professional strength nutritional guidance and support for postpartum women to achieve a balanced diet, (7) give sexuality guidance to the mother, (8) health professionals should discuss contraceptive methods with the mother, (9) daily intake of nutrients for breastfeeding mother are recommended to be taken by four or more guidelines.

Table 5.

Recommendations for postpartum care interventions

| Topic | Key recommendations |

|---|---|

| Best time to start breastfeeding after birth | • Initiate breastfeeding within 1 h after delivery [NHMRC 2012; RANO 2018; WHO 2015]. |

| Frequency of breastfeeding | • On demand and at least eight times respectively during the day and night within 24 h after birth [WHO 2015]. |

| Exclusive breastfeeding optimal duration |

• First six months [NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016; ACOG 2018b; RANO 2018; WHO 2013; 2015]. • Encourage breastfeeding continuation for 1 or 2 years on the basis of supplementary feed according to maternal decision [NHMRC 2012; ACOG 2018b; RANO 2018]. |

| Exclusive breastfeeding benefit |

• Reduce newborn’s incidence of various infectious diseases [NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016; ACOG 2018b; WHO 2013; 2015]. • Prevent baby’s infections and allergies, reduce breastfeeding mother’s vaginal bleeding [WHO 2015]. |

| Exclusive breastfeeding influencing factors |

• Influenced by positive factors (e.g., breastfeeding within 1 h after delivery, father’s support, implement Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative), negative factors (e.g., Caesarean section, mother obesity, parents smoking) [NHMRC 2012]. • Insufficient evidence to support unrelated factors (e.g., races, support except for father, infant gender, refused breast milk) [NHMRC 2012]. |

| Nipple pain or trauma treatment |

• Appropriate guidance and education of breast attachment and latching for breastfeeding mother [NHMRC 2012; RANO 2018; WHO 2015]. • Single intervention can not effectively prevent or improve maternal symptoms and duration [Sénat et al. 2016]. |

| Nipple vasospasm (Raynaud’s phenomenon), nipple dermatitis or eczema) |

• Provide specific recommendations and precautions [NHMRC 2012]. • Insufficient evidence to make a statement [Sénat et al. 2016]. |

| Breast congestion | • Analgesic measures and timely emptying of milk [NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016]. |

| Breast abscesses |

• Adapt incision drainage while avoiding antibiotic treatments [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Choose repeated puncture instead of surgical drainage to treat moderate breast abscesses [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Ultrasonic examination, needle aspiration or surgical incision drainage [NHMRC 2012]. • Continue breastfeeding if the incision location does not interfere with breastfeeding [NHMRC 2012]. |

| Mastitis |

• Drugs (e.g., aspirin, NSAID) and non-pharmacological treatment are not effective [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Treat moderate symptoms with acetaminophen or ibuprofen every 4 hours, and give antibiotics flucloxacillin (first-line drug) or cephalexin (if allergic to penicillin) 10–14 days [NHMRC 2012]. |

| Maternal illnesses |

• Prohibit breastfeeding absolutely when women with HIV-positive or undergoing breast cancer chemotherapy [NHMRC 2012]. • Suspend breastfeeding when women with severe diseases [sepsis, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or syphilis] [NHMRC 2012]. • Give additional care and treatments to breastfeeding women and babies with HIV [WHO 2015]. |

| Substance use |

• Avoid smoking, drinking, and illegal drugs when breastfeeding [NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016; NICE, 2010a; ACOG 2017; RANO 2018; WHO 2015; NICE 2021b]. • Avoid breastfeeding temporarily when taking drugs (e.g., sedatives, anti-epileptics, or opioids) or using radioactive iodine 131, iodine, povidone iodine, or iodophor [NHMRC 2012]. • Consume moderate caffeine intake (less than 750 ml) of five cups or less per day in avoidable condition [NHMRC 2012]. • Marijuana is discouraged despite insufficient evidence to evaluate the effects of marijuana on infants during breastfeeding [ACOG 2017]. |

| The optimum time of home visits |

• Within 24 h of delivery, at 3 days of delivery, between 7 and 14 days of delivery, and at 6 weeks of delivery [WHO 2013]. • At 3 days of delivery, between 7 and 14 days of delivery, and at 6 weeks of delivery [WHO 2015]. • Between 6 and 8 weeks of delivery [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Conduct early postpartum assessment within 3 weeks of delivery to address early postpartum problems, and perform a fully individualized postpartum visit within 12 weeks of delivery (4–6 weeks of delivery) [ACOG 2018a]. • Conduct home visit for the newborns during the first week of life [WHO 2013]. • Within 36 h of delivery and 7–14 days of delivery [NICE 2021b] |

| Main contents of home visits |

• Conduct basic postpartum care including maternal recovery outcomes, breastfeeding status, family social status, emotional support, and provide maternal sexual and contraceptive guidance [Sénat et al. 2016; NHFPC 2011; ACOG 2018a; WHO 2013]. • Provide professional carers to evaluate maternal diet, nutrition, exercise, and domestic violence [WHO 2013; NICE 2021b]. • Provide breastfeeding instructions to mothers and solve maternal breastfeeding difficulties [NHMRC 2012; NICE 2021b]. • Vitamin D supplements are recommended for all breastfeeding women [NICE 2021b] • Perform pap smear examination, weight detection, and timely feedback of information [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Provide advice to postpartum maternal sleep, physical fatigue, and chronic diseases management [ACOG 2018a]. • At each postnatal contact by a midwife, assess the woman’s symptoms and signs of infection, thromboembolism, anaemia, pre-eclampsia [NICE 2021b] |

| Mental health |

• Take measures to assess the emotional state of maternity during postnatal visit [NHMRC 2012; Sénat et al. 2016; NICE 2014b; 2021b; NHFPC 2015; ACOG 2018a; WHO 2013]. • Emotional assessment mainly focuses on 10–14 days after delivery [WHO 2013]. • Use Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to identify postnatal depression timely and raise the risks and precautions of using antidepressants [NHMRC 2012]. • Provide opportunities of consultation and interventions for women with depression, anxiety disorders, and serious mental illnesses (e.g., psychosis, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) [NICE 2014b]. • Provide support and guidance for women with possible postnatal depression by trained personnel [WHO 2012b]. • Give additional supportive care in case of miscarriage or stillbirth [WHO 2013]. • Manage mother’s emotional health with depression [ACOG 2018a]. |

| Pain and weight management |

• Obstetric caregivers individualize and use the step-by-step, multimodal analgesic approach to relieve pain in postpartum women [ACOG 2018c]. • Consider using a validated pain scale to monitor perineal pain [NICE 2021b] • Achieve and maintain a healthy weight through balanced diet and physical activity [NICE 2010b]. |

| Maternal nutrition | • Health professional strength, nutritional guidance, and support for postpartum women to achieve a balanced diet [NHMRC 2012; 2013; NICE 2014a; Marangoni et al. 2016; NHFPC 2011; 2015; CNS 2016; WHO 2015; AAP 2017; WHO 2011a; WHO 2016; NICE 2021b]. |

| Sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing |

• Give sexuality guidance to mother [ACOG 2018a; WHO 2013; 2015, especially within 2–6 weeks of delivery [WHO 2013]. • Health professionals discuss contraceptive methods with mother [Sénat et al. 2016; NHFPC 2011; ACOG 2018a; b; WHO 2013, 2015; FSRH 2020]. • Inform and explain the risk of short inter-pregnancy interval (less than 6 months) to women [Sénat et al. 2016; ACOG 2018a]. • Provide recommendations on how to prevent possible complications of next pregnancy [ACOG 2018a]. • The choice of contraceptive method should be initiated by 21 days after childbirth [FSRH 2020] • Women requiring contraception should be given information about and offered a choice of all methods, including long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods [NICE 2019] |

| Pelvic floor muscle training and abdominal rehabilitation |

• Providing detailed interventions [Sénat et al. 2016]. • Give women information about the importance of pelvic floor exercises [NICE 2021b] |

| Infants & newborns care |

• Carry out a complete examination of the baby within 72 h of the birth and at 6 to 8 weeks after the birth [NICE 2021b] • Assess development, mental status, and feeding effectiveness of infants [NHMRC 2012; NHFPC 2015]. • Professional carer identify infant risk signs, perform umbilical cord care [WHO 2013, 2015; NICE 2021b], counsel mothers on exclusive breastfeeding [WHO 2013; NICE 2021b], keep infant warm, vaccination [WHO 2015; NICE 2021b], and newborn care practices [WHO 2013]. • Offer parents or carers information about identity and treatment for jaundice [NICE 2016] • Consider the bathing, touching, and immunization of newborns as core elements of neonatal health care [WHO 2013]. • Offer parents or carers information about antibiotics treatment and management for neonatal infection [NICE 2021a] • Not recommend Vitamin A supplementation as a public health intervention to reduce infant morbidity and mortality among infants aged 1–5 months [WHO 2011b]. • Encourage parents to value the time they spend with their baby as a way of promoting emotional attachment [NICE 2021b] |

NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; FSRH, Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare; NHFPC, The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China; CNS, Chinese Nutrition Society; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; RANO:Registered Nurses’Association of Ontario

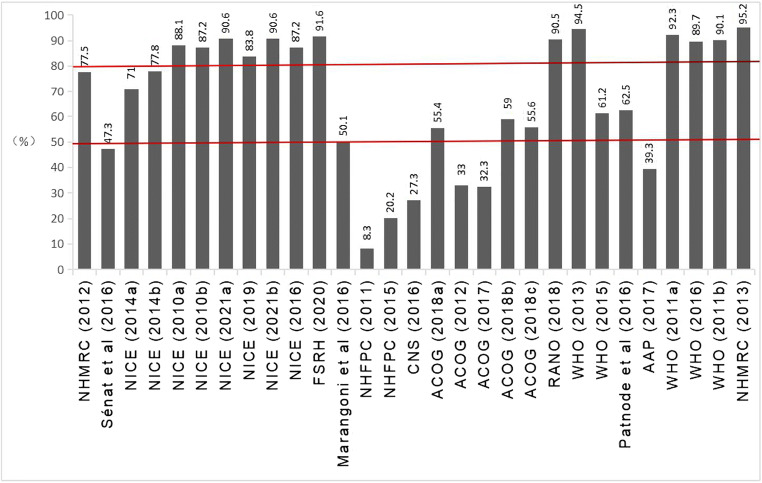

AGREE II assessment

Overall scores of the included guidelines are shown in Fig. 2. Twenty-two out of 29 guidelines scored higher than 50% (50.1%–95.2%) for total scores. Thirteen out of 29 guidelines scored higher than 80% (83.8%–95.2%) for total scores (NICE 2010a, 2010b; 2021a, 2021b; 2019; 2016; FSRH 2020; RANO 2018; WHO 2013; 2011a; 2016; 2011b; NHMRC 2013).

Fig. 2.

AGREE II overall scores of the included guidelines

Domain scores of included guidelines are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 4. Among the 29 guidelines, the guidelines developed by NICE (2010a, 2010b; 2021a, 2021b; 2016, 2019), FSRH ( 2020), RANO (2018) and WHO ( 2013; 2011a, 2011b; 2016) scored higher than 50% across all six domains. Three guidelines scored higher than 50% in five domains (NHMRC 2012; NICE 2014a; Patnode et al. 2016), whereas two guidelines achieved a score of 50% or more merely in one domain (NHFPC 2015; CNS 2016). Two guidelines scored higher than 50% only in two domains (ACOG 2012; 2017). Generally, the NICE (2010a, 2010b; 2016; 2019; 2021a; 2021b), RANO ( 2018) and WHO ( 2013; 2011a; 2016 ; 2011b) guidelines scored the highest, and well above the other eight guidelines.

Fig. 3.

AGREE II domain scores of the included guidelines

Table 4.

AGREE II domain scores of the included guidelines

| Organization | Scope and purpose % |

Stakeholder involvement % |

Rigor of development % |

Clarity of presentation % |

Applicability % |

Editorial independence % |

Overall guideline assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHMRC (2012) | 92 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 85 | 21 | Strongly recommended |

| Sénat et al. (2016) | 24 | 26 | 61 | 83 | 40 | 50 | recommended with provisions or alterations |

| NICE (2014a) | 44 | 83 | 84 | 72 | 60 | 83 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2014b) | 86 | 92 | 83 | 83 | 43.75 | 79 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2010a) | 86 | 89 | 93.75 | 92 | 85 | 83 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2010b) | 83 | 89 | 91 | 97 | 85 | 78 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2021a) | 97 | 97 | 73 | 97 | 92 | 87.5 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2019) | 83 | 83 | 88 | 89 | 85 | 75 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2021b) | 97 | 97 | 73 | 97 | 92 | 87.5 | Strongly recommended |

| NICE (2016) | 80 | 89 | 86 | 97 | 92 | 79 | Strongly recommended |

| FSRH (2020) | 86 | 92 | 93.75 | 97 | 85 | 96 | Strongly recommended |

| Marangoni et al. (2016) | 69 | 14 | 21 | 67 | 42 | 91 | recommended with provisions or alterations |

| NHFPC (2011) | 45 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Not recommended |

| NHFPC (2015) | 42 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 23 | 0 | Not recommended |

| CNS (2016) | 33 | 19 | 20 | 67 | 25 | 0 | Not recommended |

| ACOG (2018a) | 45 | 29 | 50 | 71 | 37.5 | 100 | recommended with provisions or alterations |

| ACOG (2012) | 61 | 0 | 26 | 86 | 25 | 0 | Not recommended |

| ACOG (2017) | 61 | 0 | 26 | 86 | 23 | 0 | Not recommended |

| ACOG (2018b) | 61 | 75 | 23 | 75 | 33 | 87.5 | Strongly recommended |

| ACOG (2018c) | 72 | 28 | 16 | 86 | 44 | 87.5 | recommended with provisions or alterations |

| RANO (2018) | 89 | 83 | 91 | 92 | 92 | 96 | Strongly recommended |

| WHO (2013) | 92 | 100 | 96 | 92 | 92 | 95 | Strongly recommended |

| WHO (2015) | 89 | 61 | 42 | 94 | 81 | 0 | Strongly recommended |

| Patnode et al. (2016) | 75 | 81 | 58 | 61 | 21 | 79 | Strongly recommended |

| AAP (2017) | 69 | 31 | 0 | 86 | 50 | 0 | recommended with provisions or alterations |

| WHO (2011a) | 97 | 92 | 91 | 89 | 85 | 100 | Strongly recommended |

| WHO (2016) | 92 | 94 | 91 | 92 | 83 | 96 | Strongly recommended |

| WHO (2011b) | 92 | 97 | 87.5 | 92 | 85 | 87.5 | Strongly recommended |

| NHMRC (2013) |

97 73.76 2 |

97 63 4 |

100 60.48 6 |

100 82.41 1 |

77 60.80 5 |

100 63.4 3 |

Strongly recommended |

NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; FSRH, Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare; NHFPC, The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China; CNS, Chinese Nutrition Society; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; RANO:Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario

Among the six domains of all guidelines, the highest average domain score was “Clarity of presentation” (82.41%), followed by “Scope and purpose” (73.76%), “Editorial independence” (63.40%), “Stakeholder involvement” (63.00%), “Applicability” (60.80%) and “Rigour of development” (60.48%). In addition, nineteen out of all included guidelines were labelled as “strongly recommended”, five guidelines were labelled as “recommended with provisions or alterations” and five guidelines were labelled as “not recommended”.

The ICC values for all six AGREE II domains ranged from 0.88 to 0.99 (scope and purpose:0.88; stakeholder involvement: 0.97; rigor of development: 0.99; clarity of presentation: 0.92;applicability: 0.96; editorial independence: 0.99), indicating an almost perfect level of the intra-rater agreement.

Discussion

Among all included guidelines, 19 of the overall guidelines were labelled as “strongly recommended”. Only the guidelines developed by NICE ( 2010a, 2010b; 2016; 2019; 2021a, 2021b), RANO ( 2018) and WHO ( 2013; 2011a, 2011b; 2016) scored higher than the other included across all six domains. Generally speaking, the overall quality of all involved postpartum care guidelines is relatively good and acceptable. However, there was varying quality among the guidelines. This can be attributed to the fact that the variability may be influenced by multiple factors such as guideline issuance and update date, evaluation criteria, available evidence, and appraiser opinions. NICE, RANO, and WHO guidelines based their recommendations on the best available evidence, and during the process of guideline development, they involved multidisciplinary guideline development groups, as well as producing lots of materials to support implementation activity. However, we also included consensus-based guidelines, which were developed through an agreement method of experts without systematic review of literature and careful consideration of evidence. They, to some extent, reflect the views of participants rather than update evidence, and thus are responsible for poor guideline quality.

Although significant progress in clinical guidelines development has been achieved in the past 2 decades (Grilli et al. 2000; Qaseem et al. 2012), for some national guidelines there are very few or no high-quality studies, especially randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which often drive the recommendations, with the literature largely consisting of case reports. The evidence quality may lead to conflicting or ambiguous recommendations. In our study, one of the included guidelines states that prolonging breastfeeding significantly reduces breast cancer prevalence but fails to prevent postpartum depression. A systematic review conducted by Dias & Figueiredo (2015) demonstrates that there are associations between breastfeeding and postpartum depression. However, the direction of the link and some ambiguous findings have not been explained.

Different standards are used for the establishment of guideline evidence levels, which limits the promotion and application of national guidelines to some extent. Therefore, it is recommended to use the common GRADE system to formulate their recommendations in the future (Guatt et al. 2011). Compared to other countries, the overall quality of Chinese postnatal care guidelines is unsatisfactory. There is still no complete postnatal care guideline, using RCTs or systematic reviews to support evidence for recommendations. Given the limited evidence, future guideline developers should improve adherence to the AGREE II instrument to enhance the credibility of guidelines. Our findings indicate significant variability in postpartum care guidelines in relation to care indication and interventions; this undisputed fact is also consistent with findings from other guideline reviews which highlight wide variability in guideline quality and recommendations (Hill et al. 2012; Foureur et al. 2010). In our study, comprehensive postpartum care guideline should include the eight care indications and interventions; however, most included incomplete guidelines which mainly focused on three or four indications such as exclusive breastfeeding, maternal nutrition, home visit, infant or newborn care, and sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing. Indications such as pain or weight management, pelvic floor muscle training and abdominal rehabilitation, and mental health got less attention. The reasons for this differences may be related to the core purpose of guidelines, national economic level, and regional characteristics. Given the complexity of the existing literature, and the variability in care indications and interventions in clinical guidelines, much of the literature indicates that it may be more appropriate for guidelines to stress the importance of shared decision-making (Coates et al. 2020; Domen 2016). Currently, some of the included guidelines mention that decisions should be informed by women’s preferences and a process of shared decision-making, especially with regard to the duration of continued breastfeeding and choice of contraceptive method (NICE 2021b). But in other aspects of postpartum care, most guidelines do not address shared decision-making.

This is the first review to appraise the methodological quality of postpartum care guidelines, as well as to identify and synthesize care indications and interventions. However, limitations include inclusion of English or Chinese language guidelines only, as there may have been valuable additional guidance and/or underlying contributing studies not published in English or Chinese in the non-English or non-Chinese language guidelines. Furthermore, some guideline developers could have included the AGREE items in the development process, but did not report it, thus undermining the judgement of guideline quality. The review is also of necessity limited by the quality and quantity of the underlying trials/original research that included guidelines draw upon, hence the necessity for further high-quality postpartum care RCTs.

Conclusion

Guidelines developed by NICE, RANO, and WHO demonstrated higher methodological quality. For postpartum care indications, most guidelines are incomplete. Variation in practice guidelines for postpartum care recommendations exists. In the future, implementation research into shared decision-making, as well as further high quality research to broaden the evidence base for postpartum care indications, is recommended.

Supplementary Information

(DOC 60 kb)

Authors’ contributions

Wei Yue set up the review aim and objectives. Wei Yue, Xinrui Han, and Chunhong Hu set up the review protocol. Xiaoning Sun and Jianghe Luo undertook the literature search, selection, and the final review of the results and findings with the guidance of Ming Yang. Wei Yue drafted the manuscript. Ming Yang provided supervision to the manuscript drafting and revisions. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and have approved it for submission.

Funding

This work is supported by 1) Educational Science Planning Projects in Guangdong Province: research on the mechanism of association between maternal and child health literacy and social network types in urban villages in the Pearl River Delta region [Grant number 2020JXJK079], 2) Postgraduate Education Innovation Program in Guangdong Province: research on the construction of “FIRST” five-in-one nursing talents training mode under the background of the “Double First-Class” initiative [Grant number 2020JGXM029], 3) Humanities and Social Sciences Program in Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine: research on improving the capacity of the community-based primary care nurses model in the post-epidemic era to provide traditional Chinese medicine care [Grant number 2020SKXK09], and 4) Educational Science Planning Projects in Guangdong Province: research on a multi-level innovative nursing talents training model based on “scientific research leading and task-based learning” [Grant number 2018GJK019].

Declarations

Ethical approval/review

As this is a review paper, no ethical approval or review is needed for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Consent for publication

The authors of this review have consented to its publication in the Journal of Public Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ming Yang and Wei Yue contributed equally to this work.

References

- Adane B, Fisseha G, Walle G, Yalew M. Factors associated with postnatal care utilization among postpartum women in Ethiopia: a multi-level analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Arch Public Health. 2020;78(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00415-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2017) The AGREE II Instrument (Electronic version). http://www.agreetrust.org.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (2017) The American Academy of Pediatrics breastfeeding guidelines, 2nd edn. Science and Technology Press, Beijing

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2012) ACOG Committee Opinion No 533: lead screening during pregnancy and lactation. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/08/lead-screening-during-pregnancy-and-lactation. [DOI] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2017) ACOG Committee Opinion No 722: marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/10/marijuana-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2018a) ACOG Committee Opinion No 736: optimizing postpartum care. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/05/optimizing-postpartum-care.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2018b) ACOG Committee Opinion No 756: optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/10/optimizing-support-for-breastfeeding-as-part-of-obstetric-practice .

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) (2018c) ACOG Committee Opinion No 742: postpartum pain management. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/07/postpartum-pain-management.

- UN General Assembly (2015) Sustainable development goals. SDGs, Transforming our world: vol 2030. United Nations Organisation, New York

- Campbell F, Dickinson HO, Cook JV, Beyer FR, Eccles M, Mason JM. Methods underpinning national clinical guidelines for hypertension: describing the evidence shortfall. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Nutrition Society (CNS) Dietary guidelines for lactating women. Chin J Perinatal Med. 2016;19(10):721–726. [Google Scholar]

- Coates D, Homer C, Wilson A, et al. Induction of labour indications and timing: a systematic analysis of clinical guidelines. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Dis. 2015;171:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB. Accessing pre-appraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Evid Based Nurs. 2009;12:99–101. doi: 10.1136/ebn.12.4.99-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen RE. The ethics of ambiguity: rethinking the role and importance of uncertainty in medical education and practice. Acad Pathol. 2016;3:2374289516654712. doi: 10.1177/2374289516654712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13:313–321. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) (2020). Contraception After Pregnancy. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/contraception-afterpregnancy-guideline-january-2017/.

- Flodgren G, Hall AM, Goulding L, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Leng GC, Shepperd S. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Databases of Syst Rev. 2016;8:D01066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010669.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foureur M, Ryan CL, Nicholl M, Homer C. Inconsistent evidence: analysis of six national guidelines for vaginal birth after cesarean section. Birth. 2010;37(1):3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):380–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, Mura G, Liberati A. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet. 2000;355:103–106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JB, Ammons A, Chauhan SP. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: comparison of ACOG practice bulletin with other national guidelines. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(4):969–977. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182708a60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Whelan B, Relton C, Thomas K, Strong M, Scott E, et al. Valuing breastfeeding: a qualitative study of women's experiences of a financial incentive scheme for breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1651-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois ÉV, Miszkurka M, Zunzunegui MV, Ghaffar A, Ziegler D, Karp I. Inequities in postnatal care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(4):259–270. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.140996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni F, Cetin I, Verduci E, Canzone G, Giovannini M, Scollo P, Corsello G, Poli A. Maternal diet and nutrient requirements in pregnancy and breastfeeding. An Italian consensus document. Nutrients. 2016;8(10):629. doi: 10.3390/nu8100629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2012) Infant feeding guidelines: information for health workers. NHMRC Australia, Canberra. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/infant-feeding-guidelines-information-health-workers.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2013) Australia dietary guideline. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-dietary-guidelines.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2010a) Smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth. NICE, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph26.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2010b) Weight management before, during and after pregnancy. NICE, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph27.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2014a) Vitamin D: supplement use in specific population groups. NICE, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph56.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2014b) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. NICE, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192. [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021a). Neonatal infection: antibiotics for prevention and treatment. NICE, London. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng195. [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021b). NICE guideline:postnatal care. NICE, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng194 /resources/postnatal-care-pdf-66142082148037. Accessed 20 May 2021

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2019). Long-acting reversible contraception. NICE, London. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg30. [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016). Jaundice in newborn babies under 28 days. NICE, London. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs57. [PubMed]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China (NHFPC) (2011) Work standards for pregnancy and postnatal care. NHFPC, Beijing

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China (NHFPC) (2015) National food safety standards: nutritional supplements for pregnant and breastfeeding women. NHFPC, Beijing. https://www.cnsoc.org/policys/page4.html.

- Patnode CD, Henninger ML, Senger CA, Perdue LA, Whitlock EP. Primary care interventions to support breastfeeding: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1694–1705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschlager G, Phillips S, van der Wees P, Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network Guidelines international network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):525–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RANO) (2018) Breastfeeding--promoting and supporting the initiation, exclusivity, and continuation of breastfeeding for newborns, infants, and young children. RANO, Toronto

- Sacks E, EV L. Postnatal care: increasing coverage, equity and quality. Lancet. 2016;4(7):442–443. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(6):e323–ee33. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sénat MV, Sentilhes L, Battut A, et al. Postpartum practice: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;202:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson G, Dykes F, Hurley M et al (2012) Incentives as connectors: insights into a breastfeeding incentive intervention in a disadvantaged area of north West England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12:22. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- UNICEF, WHO (2021) Tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive newborn and child health. UNICEF and WHO, New York and Geneva. http://countdown2030.org/pdf/Countdown-2030-complete-with-pro files.pdf Accessed (20 May 2021)

- UNICEF (2021). Tracking the situation of children during COVID-19. UNICEF, New York. https://data.unicef.org/resources/rapid-situation-tracking-covid-19-socioeconomic-impacts-data-viz/.

- Wiercioch W, Nieuwlaat R, Akl EA, et al. Methodology for the American Society of Hematology VTE guidelines: current best practice, innovations, and experiences. Blood Adv. 2020;4(10):2351–2365. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2011b) Vitamin A supplementation in infants 1–5 months of age. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/elena//title/guidance_summaries/vitamina_infants/en/.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2011a) Vitamin A supplementation in postpartum women. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/guidelines/vas_postpartum/en/. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. WHO, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97603/9789241506649_eng.pdf;jsessionid=53FED5316BA4A951A31FAD3569C57231?sequence=1. Accessed 20 May 2021 [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: A guide for essential practice (3 rd edition). WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/imca-essential-practice-guide/en/. Accessed 20 May 2021 [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO), UNFPA, World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division (2019) Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516488. Accessed 20 May 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2016) Guideline: Iron supplementation in postpartum women. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/9789241549585-63k. Accessed 20 May 2021 [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2017) WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee: World Health Organization. WHO, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259269. Accessed 20 May 2021

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group (2018) Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. WHO, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 20 May 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) COVID-19 could reverse decades of progress toward eliminating preventable child deaths, agencies warn. WHO, Geneva https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2020-covid-19-could-reverse-decades-of-progress-toward-eliminating-preventable-child-deaths-agencies-warn

- Yang Z, Lu H, Yu Z, Xia L. A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines on uncomplicated birth. BJOG: Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2019;127(7):789–797. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiuxia Z (2012) Nursing of obstetrics and gynecology. People's Medical Publishing House, Beijing

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 60 kb)