Abstract

Background:

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, new guidelines were issued cautioning against performing elective procedures. We aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on operational and financial aspects of plastic surgery in Miami.

Methods:

A multiple-choice and short-answer survey regarding practice changes and financial impact was sent to all 67 members of the Miami Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Results:

A 41.8% (n = 28) response rate was obtained, five responses did not meet the inclusion criteria, and statistical analysis was performed on 34.3% (n = 23) of responses. Of the plastic surgeons who responded, 21.74% operate in an academic setting, 60.87% are in a single practitioner private practice, and 17.39% are in a multi-practitioner private practice. An estimated 60% of academic plastic surgeons had 75% or more of their previously scheduled cases canceled, compared with 57.14% in single practitioner private practice and 100% in multi-practitioner private practice. In total, 64.29% of single practitioner private practices and 50% of multi-practitioner private practices have had to obtain a small business loan. Single practitioner private practice plastic surgeons reported having an average of 6.5 months until having to file for bankruptcy or permanently close their practices, and multi-practitioner private practice plastic surgeons reported an average of 6 months.

Conclusions:

Guidelines to support small business must be implemented in order to allow private practice surgeons to recover from the substantial economic impact caused by the pandemic because it is necessary to reestablish patient access and provide proper care to our patients.

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has created a rapidly evolving global health crisis that has brought the world to a halt. The disease emerged from China in December 2019, and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020.1 In a short span of several months, the virus has spread diffusely and has infected over 110,000,000 people worldwide and has claimed the lives of over 2,400,000 people.2,3 If left unchecked, the virus could potentially claim the lives of many others. Measures to contain the disease have been limited, and faulty healthcare systems and public health systems may have contributed to the severity of the pandemic.4

Countries such as Italy that were impacted before the global realization of the imminent danger at hand suffered greatly. Health care systems were overwhelmed by the rapidly rising number of cases and the workload required to care for these patients. Within weeks, countries around the globe implemented guidelines such as those recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, which range from social distancing to curfews and stay-at-home orders, in an attempt to curb the spread of disease and prevent potentially overwhelming the healthcare system.5,6

It is known that COVID-19 is mainly spread through the respiratory droplets of affected patients.7 Given that COVID-19 is primarily a medical disease with no known surgical intervention, virtually all surgery came to a halt. Plastic surgery was no exception. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons recommendations encouraged all plastic surgeons to cease performing elective or nonessential services, thus reducing exposure to aerosol-generating procedures and potential transmission of the disease as well as preserving the limited supply of personal protective equipment and redirecting them to healthcare providers caring for COVID-19 patients.8,9 Shortly thereafter, 36 states issued guidelines prohibiting all healthcare personnel from providing any medically unnecessary, nonurgent or nonemergent services.10 Florida was one of the last states in which the governor issued a stay-at-home order, and therefore was at an increased risk of developing new cases of COVID-19.10 The lack of timely implementation of public health measures intended to curb the disease could have had catastrophic results for the collective health of the city of Miami, one of the major metropolitan centers in the United States, and a sought-after destination for tourism and business.

Miami is known for its robust plastic surgery community, which covers a wide spectrum ranging from private practice to tertiary care centers and safety-net hospitals. What makes plastic surgery in Miami unique is the large number of plastic surgery practices along with a high concentration of world-renowned plastic surgeons who are experts in their fields, leading to patients coming to Miami from all over the world seeking plastic surgery. Miami has a long history with plastic surgery, and the climate provides an optimal environment for recovery without the stigma associated with cosmetic surgery. It is for these reasons that Miami became known as the plastic surgery capital of the world.

Sir Harold Gillies’ principles of plastic surgery state to “always keep a lifeboat.”11 Keeping a lifeboat is an important principle that underscores not only wound repair, but operational and financial aspects of plastic surgery as well. Things do not always go as planned and alternatives must be kept in mind. Plastic surgery is characterized by innovation and the ability to solve problems. Through continuing to provide patient care, plastic surgeons can continue to fulfill their duty to patients and duty to serve during unprecedented times. However, they must be able to remain financially afloat to continue providing care to patients. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on operational and financial aspects of plastic surgery practices in Miami, so as to explore how plastic surgeons can recover from the situation at hand, and how they can protect themselves in similar situations should they arise in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An institutional review board-approved anonymous, multiple-choice and short-answer Qualtrics survey regarding plastic surgery practice changes and financial impact was sent to all 67 active and nonactive members of the Miami Society of Plastic Surgeons by email on April 28, 2020. The moratorium on elective procedures was in effect at the time the survey was conducted. The survey was closed on May 28, 2020, and the data were collected and processed through Qualtrics statics reports. Survey responses with less than 30% completion were excluded from statistical analyses.

RESULTS

A 41.8% (n = 28) response rate was obtained, five responses did not meet the inclusion criteria, and statistical analysis was performed on 34.3% (n=23) of responses. Of the plastic surgeons who responded, 21.74% operate in an academic setting, 60.87% operate in a single practitioner private practice, and 17.39% operate in a multi-practitioner private practice. The percentage of cases normally seen in practice across academic and private practice plastic surgeons is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of Cases Seen in Practice in Academic and Private Practice

| Field | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmetic? __% | 0.00 | 100.00 | 50.39 | 33.43 |

| Reconstructive? ___% | 0.00 | 85.00 | 35.26 | 26.71 |

| Hand? ___% | 0.00 | 90.00 | 13.48 | 27.76 |

| Other | 0.00 | 20.00 | 0.87 | 4.08 |

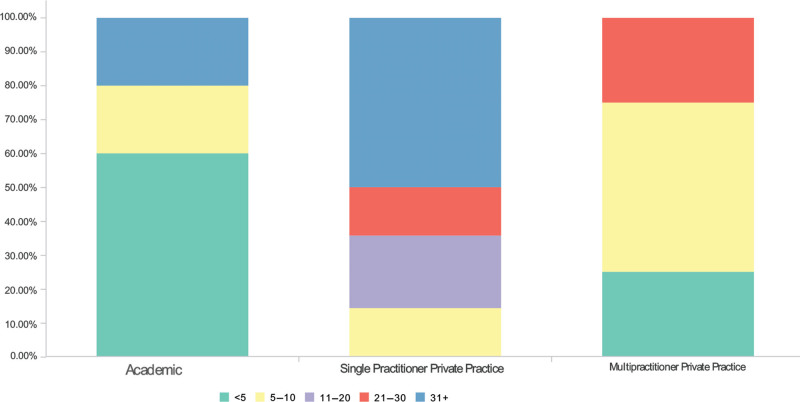

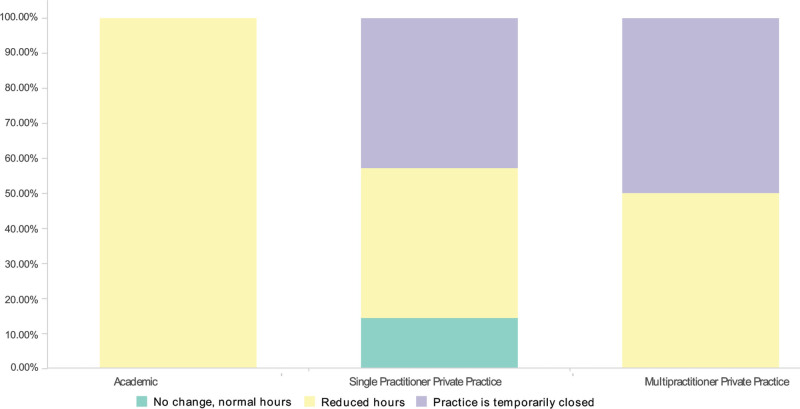

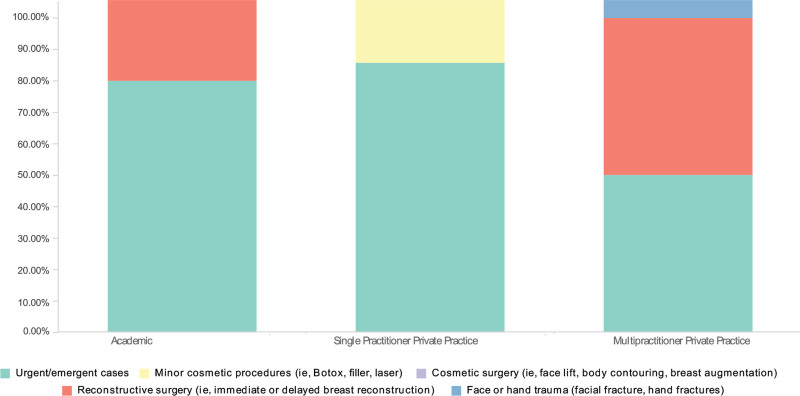

The number of years each plastic surgeon has been in practice is shown below in Figure 1 and is separated by the type of practice. The hours of operation during the COVID-19 pandemic are also recorded and divided by type of practice as shown in Figure 2. The types of cases seen during the COVID-19 pandemic by different practices are demonstrated in Figure 3.

Fig. 1.

The number of years in practice separated by the type of practice.

Fig. 2.

Hours of operation separated by the type of practice.

Fig. 3.

Type of cases seen during COVID-19 pandemic separated by the type of practice.

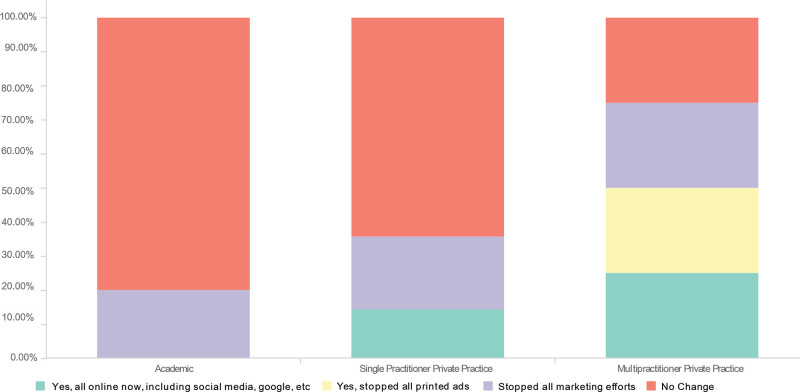

Many plastic surgeons began offering virtual consults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighty percent of academic plastic surgeons conducted fewer than 10 virtual consults per week, compared with 64.29% of single practitioner private practice and 100% of multi-practitioner private practice. Sixty percent of academic plastic surgeons had 75% or more of their previously scheduled cases canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with 57.14% in single practitioner private practice and 100% in multi-practitioner private practice. Figure 4 demonstrates how marketing strategies have changed across the types of practice and highlights the methods used.

Fig. 4.

Marketing strategy changes due to COVID-19 pandemic divided by type of practice.

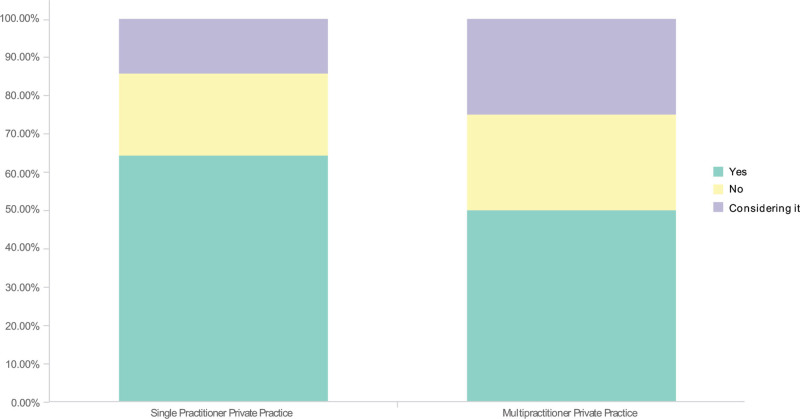

Eighty-eight percent of private practice plastic surgeons stated that they were not able to obtain a discount for their rented equipment (lasers, medical devices, etc). Seventy-seven percent of all plastic surgeon respondents stated that there are currently no companies offering to take back expiring products like Botox and fillers. Sixty-four percent of single practitioner private practices and 50% of multi-practitioner private practices have had to obtain a loan, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of plastic surgeons who have obtained a loan due to COVID-19 pandemic separated by type of practice.

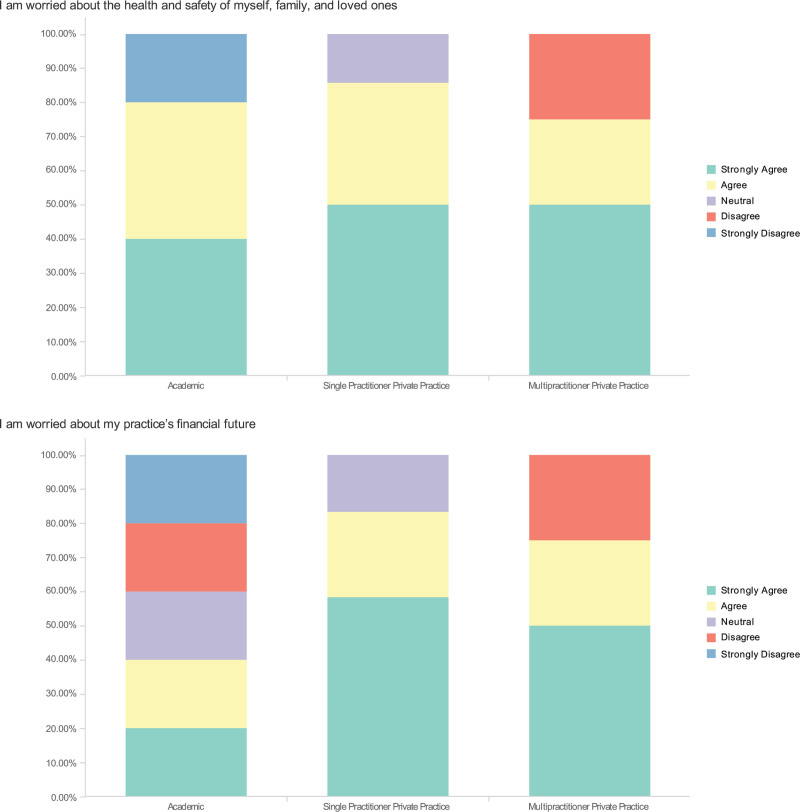

On average, private practice plastic surgeons employ six ancillary staff. Sixty-seven percent of private practice plastic surgeons stated that salary is their biggest overhead followed by 33.33% stating that rent is their biggest overhead. Fifty-seven percent of single practitioner private practice surgeons are paying full salaries followed by 21.43% paying reduced salaries, compared with 50% of multi-practitioner private practice surgeons who are paying full salaries followed by 50% paying reduced salaries. Of the single practitioner private practice surgeons, 42.86% agreed to pay full salaries until the COVID-19 pandemic is resolved compared with 50% of multi-practitioner private practice. Thirty-six percent of single practitioner private practice and 25% of multi-practitioner private practice plastic surgeons had employees placed on furlough compared with 0% of academic surgeons. Fifty percent of academic plastic surgeons reported losing $20,000 or more per week due to COVID-19 pandemic compared with 76.92% of single practitioner private practice and 50% of multi-practitioner private practice. When plastic surgeons were asked how long they have until they have to file for bankruptcy or permanently close their practice, single practitioner private practice surgeons reported having an average of 6.5 months and multi-practitioner private practice surgeons having an average of 6 months. Figure 6 demonstrates the level of worry that plastic surgeons have regarding their families and loved ones, as well as the future of their practice. When asked if the American Society of Plastic Surgeons has been helpful during this pandemic, 52.17% responded yes, highlighting guidelines and webinars to be very helpful.

Fig. 6.

Scale of worry about the health and safety of family and loved ones as well as the financial future of their practice separated by type of practice.

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented public health crisis that brought the world to a halt. While countries around the world took measures to prevent overwhelming the healthcare system, healthcare providers were tasked with implementing new management tactics to care for the rapidly increasing number of patients with COVID-19 in addition to all other patients.12,13 New management strategies mandated physicians to conserve resources and adjust to a new norm of practice.12

Many plastic surgery practices were required to limit the type of cases seen to urgent or emergent cases. Some practices began offering telemedicine consultations, and others either had limited hours or closed their practice entirely. With such a sudden drastic change in the scope of practice of plastic surgery, we sought out to measure the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on plastic surgeons in Miami.

In our order to assess the impact of the pandemic on plastic surgeons, we examined the demographics of our sampled population. We surveyed plastic surgeons in academic, single practitioner and multi-practitioner private practice. As seen in Figure 1, the overall majority of respondents are well established and have been in practice for more than five years, and Table 1 shows that our sampled population has a wide scope of clinical practice that covers all aspects of plastic surgery.

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, hours of operation were significantly affected across all three types of practice, with the majority shifting to urgent/emergent cases and hand/face trauma. This may be due to the reduction in nonemergent cases and relative increase of emergent cases, as well as a shift to performing more emergent cases to be able to continue to operate and reduce the burden on emergency departments.12–14

Interestingly, out data suggest that virtual consults were not utilized to their full potential. The majority of plastic surgeons who offered virtual consults were still conducting fewer than 10 virtual consults per week, which suggests that patients prefer to interact with their plastic surgeons in person.15 Other causes can be due to the fact that it is a new concept that was not previously utilized, and patients were either not familiar with it or not comfortable using it, especially because plastic surgery physical examinations tend to be very private and require extensive exposure of the patient. The possibility that there are limitations that prevent patients from participating in virtual consults could also be a reason for the limited number of virtual consults.

The impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice was not only limited to consults; the majority of plastic surgeons across all three types of practices had more than 75% of their previously scheduled cases get canceled due to the pandemic with multi-practitioner private practice having 100% of their cases canceled. The substantial drop in patient access also had a significant negative impact on the financial stability of these practices and especially private practices.15,16 While patient access suddenly became practically nonexistent, the financial overhead many practices carry did not change. Plastic surgeons across the board reported that they were still required to pay rent, that they were not able to obtain any sort of negotiated discount for their rented equipment such as lasers and medical devices, and that there were no plans for pharmaceutical companies to take back any unused or expiring products. It is worth noting that there was a 10% variation between being able to obtain a discount on rented equipment compared with being able to return expiring products. We believe this is due to the nature of the long-term contracts in place with rented equipment, and companies might be more willing to negotiate with practices when such contracts are not in place.

Just as the world economy was negatively impacted by the pandemic, plastic surgeons were no different.17,18 As we can see from the data presented, plastic surgeons across the board were seeing fewer patients and preforming fewer procedures. Further extrapolation of the figures above shows that private practice plastic surgeons were most affected by the economic crash the pandemic produced. Private practice physicians are similar other small businesses, but whose goal is to provide patients with proper care by a board-certified physician and as a small business, they do in fact need to be financially stable to continue providing their patients with care while positively impacting the local economy.18

Plastic surgery private practices employ an average of six ancillary staff and the majority of plastic surgeons state that salary is their largest overhead. Ancillary staff are an integral component of any practice and physicians would not be able to operate without them. Plastic surgeons spend a significant amount of time with their office staff. As we can see from our data, plastic surgeons sense a moral obligation to ensure that their employees are well cared for, especially during a pandemic. More than half of private practice plastic surgeons were still paying full salaries, many of whom agreed to do so until the end of the pandemic.

Private practice plastic surgeons continue to uphold their financial obligations; however, this imposes great challenges, as shown by 76.92% of single practitioner private practice and 50% of multi-practitioner private practice report losing $20,000 or more per week due to the COVID-19 pandemic compared with 50% of academic plastic surgeons. It is apparent that private practice plastic surgeons are suffering significantly, and Figure 5 explains how the majority of these practices have been able to withstand the financial shock. Sixty-four percent of single practitioner private practice surgeons and 50 percent of multi-practitioner private practice surgeons have obtained a loan due to the pandemic to continue to uphold their financial obligations.

While it is easy to assume that the financial and operational impact of COVID-19 is limited to private practice plastic surgeons, it can theoretically be generalized to any small business. According to the United States Small Business Administration, healthcare and social assistance businesses that have 1–20 employees provide jobs for 569,088 people, which accounts for 21.62% of all healthcare and social assistance businesses.18 This shows the significant impact these practices have on the economy as a whole and the urgent need for federal agencies to intervene to ensure that the national economy does not collapse further.

Figure 6 provides a visual representation of the current state of worry that is amongst plastic surgeons, with the majority stating that they are worried about their own safety and the safety of their loved ones as well as the financial future of their practice. If we as a society do not intervene once restrictions are lifted to help these practices, we might be faced with a significant economic crash at the local and national level that ultimately causes many of these practices to vanish. Upholding all financial obligations during a lockdown is only financially sustainable for a limited period of time, especially in a period of anxiety and uncertainty. Private practice plastic surgeons reported that they have an average of approximately 6 months until they have to file for bankruptcy or permanently close their practice, which foreshadows the limited time that we, as a society, have remaining to intervene on behalf of these practices.

Local guidelines are urgently needed to prevent such a catastrophe from happening. Insurance companies can also help protect these businesses by including pandemics under the catastrophe clause of their insurance policies. Cities can begin with covering the costs of additional personal protective equipment that many practices require due to the change in current laws as well as offsetting the cost of preoperative COVID-19 testing to ensure patient and provider safety. Additionally, local governments can offer rental extensions to suffering small businesses and can create a pathway for tax breaks and additional loans with delayed repayment plans to allow these businesses to recover from the financial impact caused by the pandemic.

Albeit vital to plastic surgery, research concerning private practice plastic surgeons is very limited. We conducted a thorough literature search regarding plastic surgery, private practice, and COVID-19, and we were not able to find any published data, which was a limitation to our discussion because we are not aware of the impact that COVID-19 has had on other cities. Other limitations included our survey response rate and small sample size due to the geographic limitations set by our study.

CONCLUSIONS

The world economy as a whole was negatively impacted by the pandemic, all plastic surgeons included. Academic surgeons were negatively impacted but to a lesser extent, due to the nature of their practice and the magnitude of the academic centers they operate in, compared with private practice plastic surgeons who were severely impacted. This negative economic impact not only affects the surgeons, but also families, employees, and the local economy. Our data provide a unique perspective that demonstrates how significant the negative impact has been and emphasizes the necessity for local guidelines to support small businesses to allow private practice surgeons to recover from the substantial economic impact caused by the pandemic.

Footnotes

Published online 19 July 2021.

Drs. Mahmood J. Al Bayati and George J. Samaha contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, et al. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Home – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [online]. 2021. Available at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 3.World Health Organisation. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation reports. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizumoto K, Chowell G. Estimating risk for death from 2019 novel coronavirus disease, China, January-February 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1251–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus (COVID-19). [online]. 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). [online]. 2020. Available at nih.gov/health-information/coronavirus. Accessed June 16, 2020. [PubMed]

- 7.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facchin F, Scarpa C, Vindigni V, et al. Effectiveness of preventive measures against Covid-19 in a Plastic Surgery Unit in the epicenter of the pandemic in Italy. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:112e–113e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. ASPS guidance regarding elective and non-essential patient care. [online]. 2020. Available at https://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/covid19-member-resources/previous-statements. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 10.Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. State guidance on elective surgeries. [online]. 2020. Available at https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-state. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 11.Pandey S, Chittoria RK, Mohapatra DP, et al. Mnemonics for Gillies principles of plastic surgery and it importance in residency training programme. Indian J Plast Surg. 2017;50:114–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taub PJ. Plastic surgeons in the time of a pandemic: thoughts from the front line. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:458–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teven CM, Rebecca A. Coronavirus and the responsibility of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganesh Kumar N, Garfein ES, Cederna PS, et al. Responding to the COVID-19 crisis: if not now, then when? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:711–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Omar K, Bakkar S, Khasawneh L, et al. Resuming elective surgery in the time of COVID-19: a safe and comprehensive strategy. Updates Surg. 2020;72:291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reissis D, Georgiou A, Nikkhah D, et al. U.K. response to the COVID-19 pandemic: managing plastic surgery patients safely. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:250e–251e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKinsey & Company. Covid-19 implications for business. [online]. 2020. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/covid-19-implications-for-business#. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 18.Small Business Association. 2018 small business profile. [online]. 2018. Available at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/2018-Small-Business-Profiles-US.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.