Cardiovascular medicine is among the most gender-imbalanced medical specialties in the United States. Over the last 12 years, the proportion of women in U.S. cardiology fellowship programs has remained stagnant around 20% (1). A recent survey led by the American College of Cardiology revealed that the majority of female cardiologists experience gender bias in their daily lives (2). Over the last decade, many professional barriers for female cardiologists—such as wage inequality (3,4), discrimination and sexual harassment (2), lack of mentorship and role modeling (5), and inadequate workplace support for pregnant and nursing cardiologists (6)—have become better defined. These obstacles uniquely affect female trainees, as fellowship training occurs during childbearing years, a particularly vulnerable personal and professional time. They may struggle with timing pregnancies, concerns about exposure to radiation, ensuring adequate or paid maternity leave, perceptions about burdening peers due to missed training, and working in a traditionally male-dominated environment that is historically unfamiliar with or unfriendly to pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Despite the well-established benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and infants, many women physicians face overwhelming barriers that prevent them from breastfeeding after returning to work. In a survey of more than 14,000 physician mothers, only 42% reached the recommended 12-month target duration for breastfeeding (7). A smaller survey of cardiology fellows at a single center found that half of the women stopped breastfeeding before 6 months (8). A 2015 American College of Cardiology survey found that 68% of female cardiologists reported experiencing significant obstacles to breastfeeding upon re-entry to work, including time constraints, lack of pumping space, lack of adequate breaks, and inability to maintain milk supply (6). Given that the majority of female cardiologists are pregnant at some point in their careers, improving the experience of pregnancy and early parenthood, particularly during the more vulnerable periods of fellowship training, would support female cardiologists, create an inclusive work environment, and may attract talented students and residents who would have otherwise avoided pursuing cardiology due to these perceived barriers.

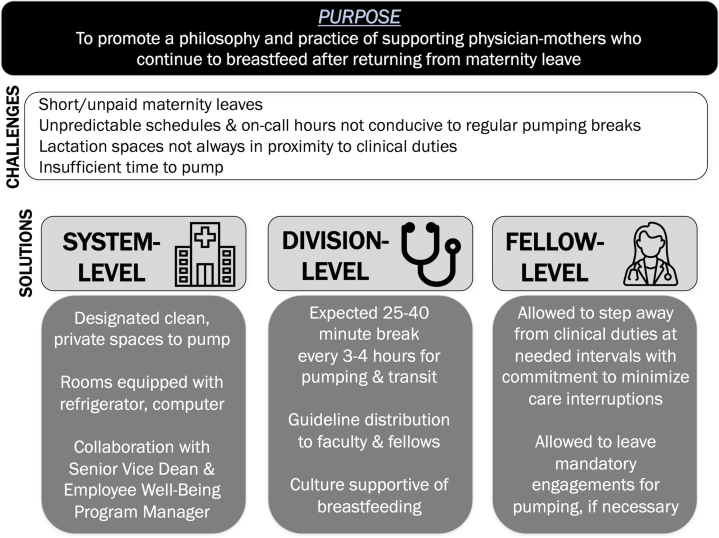

To demonstrate its commitment to supporting female cardiology fellows and to minimize some of the most apparent workplace obstacles to successful breastfeeding, the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Division of Cardiovascular Medicine developed a set of behavioral and practice guidelines for lactating fellows, written by fellows-in-training and early career faculty: Guidelines for Wellness of Breastfeeding Cardiology Fellows (Figure 1). The document summarizes challenges faced by breastfeeding fellows, namely that the 80-h workweek, overnight and weekend hours on call, and unpredictable schedules are not conducive to regular pumping breaks. Furthermore, the guidelines acknowledge the lack of sufficient time and dedicated spaces for women to pump. The document enumerates the minimum requirements necessary for pumping spaces used by fellows—cleanliness, privacy, refrigeration capabilities, and availability of a telephone and computer for performing clinical work—and the typical amount of time (i.e., 25 to 40 min every 3 to 4 h, including time to travel to and from the lactation area) required to express milk. Most importantly, the guidelines emphasize the importance of a supportive culture in helping our trainee mothers meet their parenting goals.

Figure 1.

Purpose and framework for the Guidelines for Wellness of Breastfeeding Cardiology Fellows

The guidelines recognize that fellows have an ongoing and unwavering commitment to patient care and should give careful consideration to clinical continuity when scheduling pumping breaks. They emphasize communication between breastfeeding fellows and those impacted by their breaks—attending physicians, co-fellows, residents, and students on the given service. Fellows in clinic or on the inpatient services are given time to step away from clinical duties at a reasonable interval and are expected to communicate this clearly to team members ahead of time. Fellows on procedural rotations, such as interventional cardiology, echocardiography, and electrophysiology, minimize interruption to procedural teams by pumping before or after cases whenever possible. Given that fellows’ daily morning and noon conferences provide protected time at 2 separate times of the day, breastfeeding mothers are given explicit permission to leave those didactics for pumping if necessary. The document clearly sets the expectations that fellows will not be discriminated against for taking time during the day to pump and that required clinical duties will be completed in a timely fashion. Access to additional institutional resources for breastfeeding fellows, colleagues, and supervisors is included in the document, which also specifies that if any issues regarding a fellow’s ability to pump are to arise, the Program Director will take responsibility in assessing and meeting the fellow’s specific needs. Overall, the document is, to our knowledge, the first of its kind implemented in a cardiovascular training program. For a general fellowship that has comprised 50% women over the past 3 years, the guidelines are a unique demonstration of leadership support and a proclamation that fellows’ health and well-being are core priorities of the Cardiovascular Division. These guidelines are a part of our initiatives to improve the climate for trainee parents taking time away from and re-entering training, including a standardized approach to scheduling parental leave for women and men, 12 weeks of leave with flexible rotation assignments offered for each trainee parent, and support for trainees to continue pursuing academic interests upon their return to work.

After approval by the fellowship Program Director, the guidelines were disseminated to faculty and posted to the fellowship’s intranet site, a central hub containing essential resources for fellows. They are also individually sent to every pregnant fellow and advertised at Women in Cardiology events and other Department of Medicine women’s groups meetings. The guidelines are part of a collection of resources provided to each pregnant fellow, which also includes the locations of lactation rooms around the health system and information about maternity leave allowances. Creation of the guidelines also prompted a fellow-driven, hospital-wide assessment of the available lactation spaces, in collaboration with the institution’s Senior Vice Dean for Academic Affairs and Employee Benefit and Well-Being Program Manager. This effort resulted in a number of changes being made, including increased numbers and better labeling of lactation spaces, improved resourcing of the spaces, and creation of innovative pilot programs for efficient scheduling of the most highly utilized rooms.

Since the guidelines were implemented, 4 fellows either became new mothers or continued breastfeeding to meet their goals. Feedback from trainee mothers has been overwhelmingly positive. Women fellows have stated that the creation and dissemination of the guidelines raised awareness of the importance of pumping and led to faculty more openly supporting fellows to break from clinical duties as needed. They also felt that the guidelines gave them confidence to balance their work and parenting commitments and relieved the self-doubt and guilt that many trainee mothers experience during breastfeeding. In the future, we plan to collect data from fellows and attending physicians on their awareness, knowledge, and perception of organizational and institutional policies regarding parental leave and breastfeeding and how the policies influence their goals and experiences.

Although significant gender disparities within cardiology exist, there is growing momentum for systemic change and to create a more inclusive and diverse environment within the field. Becoming a parent during cardiology training is not uncommon, and programs should be prepared to help both women and men with clearly outlined policies, including one for women who continue to breastfeed after returning to work. We have experienced success with our Guidelines for Wellness of Breastfeeding Cardiology Fellows, and this initiative is embedded in a larger ongoing programmatic effort to advocate for adequate and paid maternity and paternity leaves, widely disseminate medical specialty board and existing health system policies on leave and extensions of training, and ensure occupational radiation safety. By cultivating a culture of openness and acceptance for new and future parents, we hope that continued efforts such as ours help support trainees as well as attract and retain more women as future generations of cardiologists.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Michigan Department of Surgery Residents for inspiring them to create our guidelines and Drs. Thomas P. Cappola, Srinath Adusumalli, Dipika Gopal, Allison Padegimas, and the women fellows and faculty of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania for their support of this initiative.

Footnotes

Dr. Reza is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Human Genome Research Institute Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service T32 Award in Genomic Medicine (T32 HG009495). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.ACGME Data Resource Book. https://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book Available at:

- 2.Lewis S.J., Mehta L.S., Douglas P.S. Changes in the professional lives of cardiologists over 2 decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagsi R., Biga C., Poppas A. Work activities and compensation of male and female cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah R.U. The $2.5 million wage gap in cardiology. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:674–676. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal D.M., Olenski A.R., Yeh R.W. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017;135:506–517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarma A.A., Nkonde-Price C., Gulati M., Duvernoy C.S., Lewis S.J., Wood M.J. Cardiovascular medicine and society: the pregnant cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melnitchouk N., Scully R.E., Davids J.S. Barriers to breastfeeding for US physicians who are mothers. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1130–1132. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mwakyanjala E.J., Cowart J.B., Hayes S.N., Blair J.E., Maniaci M.J. Pregnancy and parenting during cardiology fellowship. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]