Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

What is the cumulative delivery rate (CDR) per aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle in low-prognosis patients as defined by the Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number (POSEIDON) criteria?

SUMMARY ANSWER

The CDR of POSEIDON patients was on average ∼50% lower than in normal responders and varied across POSEIDON groups; differences were primarily determined by female age, number of embryos obtained, number of embryo transfer (ET) cycles per patient, number of oocytes retrieved, duration of infertility, and BMI.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The POSEIDON criteria aim to underline differences related to a poor or suboptimal treatment outcome in terms of oocyte quality and quantity among patients undergoing IVF/ICSI, and thus, create more homogenous groups for the clinical management of infertility and research. POSEIDON patients are presumed to be at a higher risk of failing to achieve a live birth after IVF/ICSI treatment than normal responders with an adequate ovarian reserve. The CDR per initiated/aspiration cycle after the transfer of all fresh and frozen–thawed/warmed embryos has been suggested to be the critical endpoint that sets these groups apart. However, no multicenter study has yet substantiated the validity of the POSEIDON classification in identifying relevant subpopulations of patients with low-prognosis in IVF/ICSI treatment using real-world data.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

Multicenter population-based retrospective cohort study involving 9073 patients treated in three fertility clinics in Brazil, Turkey and Vietnam between 2015 and 2017.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Participants were women with infertility between 22 and 42 years old in their first IVF/ICSI cycle of standard ovarian stimulation whose fresh and/or frozen embryos were transferred until delivery of a live born or until all embryos were used. Patients were retrospectively classified according to the POSEIDON criteria into four groups based on female age, antral follicle count (AFC), and the number of oocytes retrieved or into a control group of normal responders (non-POSEIDON). POSEIDON patients encompassed younger (<35 years) and older (35 years or above) women with an AFC ≥5 and an unexpected poor (<4 retrieved oocytes) or suboptimal (4–9 retrieved oocytes) response to stimulation, and respective younger and older counterparts with an impaired ovarian reserve (i.e. expected poor responders; AFC <5). Non-POSEIDON patients were those with AFC ≥5 and >9 oocytes retrieved. CDR was computed per one aspirated cycle. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to examine the association between patient classification and CDR.

MAIN RESULTS AND ROLE OF CHANCE

The CDR was lower in the POSEIDON patients than in the non-POSEIDON patients (33.7% vs 50.6%; P < 0.001) and differed across POSEIDON groups (younger unexpected poor responder [Group 1a; n = 212]: 27.8%, younger unexpected suboptimal responder [Group 1b; n = 1785]: 47.8%, older unexpected poor responder [Group 2a; n = 293]: 14.0%, older unexpected suboptimal responder [Group 2b; n = 1275]: 30.5%, younger expected poor responder [Group 3; n = 245]: 29.4%, and older expected poor responder [Group 4; n = 623]: 12.5%. Among unexpected suboptimal/poor responders (POSEIDON Groups 1 and 2), the CDR was twice as high in suboptimal responders (4–9 oocytes retrieved) as in poor responders (<4 oocytes) (P = 0.0004). Logistic regression analysis revealed that the POSEIDON grouping, number of embryos obtained, number of ET cycles per patient, number of oocytes collected, female age, duration of infertility and BMI were relevant predictors for CDR (P < 0.001).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Our study relied on the antral follicle count as the biomarker used for patient classification. Ovarian stimulation protocols varied across study centers, potentially affecting patient classification.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

POSEIDON patients exhibit lower CDR per aspirated IVF/ICSI cycle than normal responders; the differences are mainly determined by female age and number of oocytes retrieved, thereby reflecting the importance of oocyte quality and quantity. Our data substantiate the validity of the POSEIDON criteria in identifying relevant subpopulations of patients with low-prognosis in IVF/ICSI treatment. Efforts in terms of early diagnosis, prevention, and identification of specific interventions that might benefit POSEIDON patients are warranted.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

Unrestricted investigator-sponsored study grant (MS200059_0013) from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or manuscript preparation. S.C.E. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck and lecture fees from Merck and Med.E.A. H.Y. declares receipt of payment for lectures from Merck and Ferring. L.N.V. receives speaker fees and conferences from Merck, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) and Ferring and research grants from MSD and Ferring. J.F.C. declares receipt of statistical services fees from ANDROFERT Clinic. T.M.H. received speaker fees and conferences from Merck, MSD and Ferring. P.H. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck, Ferring, Gedeon Richter and IBSA and lecture fees from Merck, Gedeon Richter and Med.E.A. C.A. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck and lecture fees from Merck. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: ART, cumulative delivery rate, embryo transfer, infertility, live birth, life table, POSEIDON criteria, real-world evidence

Introduction

The Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number (POSEIDON) criteria identify and classify the so-called ‘low-prognosis’ patients undergoing ART (Humaidan et al., 2016; Poseidon Group et al., 2016). Under this system, patients are classified into four groups based on female age, ovarian reserve markers (antral follicle count (AFC) and/or anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)), and the number of oocytes retrieved if the patient previously underwent a standard ovarian stimulation. Accordingly, POSEIDON patients encompass women with a sufficient ovarian reserve and a poor or suboptimal response to standard stimulation (i.e. unexpected poor responders (<4 retrieved oocytes) or unexpected suboptimal responders (4–9 retrieved oocytes)), and women with an impaired ovarian reserve (i.e. expected poor responders). These patients are further stratified according to age using a threshold of 35 years. The POSEIDON classification aims to underline differences related to a poor or suboptimal treatment outcome in terms of oocyte quality and quantity, and, thus, create more homogenous groups for the clinical management of infertility and research (Esteves et al., 2019a).

POSEIDON patients are presumed to be at a higher risk of failing to achieve a live birth after IVF/ICSI treatment than normal responders with an adequate ovarian reserve. The cumulative delivery rate (CDR) per initiated/aspiration cycle after the transfer of all fresh and frozen–thawed/warmed embryos has been suggested to be the critical endpoint that sets these groups apart (Esteves et al., 2021a). This metric is increasingly being recognized to be an appropriate way to report ART success (Moragianni and Penzias, 2010; Maheshwari et al., 2015) and has been selected as a critical efficacy outcome in the ESHRE 2019 guideline on ovarian stimulation for IVF/ICSI (Ovarian Stimulation TEGGO et al., 2020). Moreover, it is considered the most meaningful outcome from the patients’ perspective because it adequately reflects the prognosis of achieving a live birth after one initiated/aspirated ART cycle (Malizia et al., 2009).

As ART may involve multiple embryo transfers (ETs), the CDR captures the role of oocyte quality and quantity that are the pillars of the POSEIDON criteria. Female age is a surrogate for oocyte competence given its well-established association with oocyte/embryo ploidy (Cimadomo et al., 2018; Esteves et al., 2019b). In addition, ovarian reserve markers, particularly AFC and AMH, predict the ovarian response to gonadotropin stimulation and, therefore, the expected number of oocytes retrieved (Tal and Seifer, 2017). The latter is closely associated with CDR because each oocyte has pregnancy potential (Drakopoulos et al., 2016; Polyzos et al., 2018). An increased oocyte yield may increase the number of embryos potentially obtained, thereby enhancing the possibility of a live birth delivery with the transfer of fresh or cryopreserved embryos generated from a single stimulation cycle (Vermey et al., 2019).

Accurate reporting of CDR is an essential step in the validation of the POSEIDON criteria. However, as only minimal data on the reproductive prospects of low-prognosis patients are available (Leijdekkers et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020), we investigated the CDR per aspiration cycle of POSEIDON patients using large data analytics. Our primary objectives were (i) to compare CDR among POSEIDON (sub)groups using a control group of normal responders as the reference population, and (ii) to assess the impact of patient and treatment factors on the CDR of POSEIDON patients.

Materials and methods

This is an institutional review board-approved study based on retrospective data collected from patients with infertility who underwent IVF-ICSI treatment between 2015 and 2017 in three fertility centers (ANDROFERT, Campinas, Brazil; Anatolia IVF and Women’s Health Center, Ankara, Turkey; and My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam). The study complies with the standards for reporting observational studies (STROBE) (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

Study population

Eligible patients were consecutively enrolled women with infertility between the ages of 22 and 42 years who had their first IVF/ICSI cycle in the study centers. Included were all patients who (i) had been treated using a standard ovarian stimulation protocol, (ii) had undergone oocyte pick-up regardless of whether or not oocytes were retrieved, and (iii) had either delivered a live-born infant after a fresh or frozen–thawed ET (FET) or had not had a live birth delivery after the transfer of all embryos obtained. Only one cycle per patient was analyzed. Patients undergoing preimplantation genetic testing and those who had undergone IVF/ICSI for purposes other than infertility were excluded. Also excluded were patients treated with mild or minimal stimulation protocols (Nargund et al., 2007) because ovarian stimulation using gonadotropin starting doses of 150 IU or higher is a precondition to classify a patient according to the POSEIDON criteria.

Assessment of ovarian reserve

Ovarian reserve assessment was carried out during a natural menstrual cycle 1–3 months before starting the stimulation. Antral follicle count was measured during the early follicular phase using 2-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography according to the practical recommendations for the standardized use of AFC (Broekmans et al., 2010). AMH serum values were determined using the modified Beckman Coulter Generation II enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Craciunas et al., 2015). Ovarian biomarker results were available before any treatment decision was made concerning the ovarian stimulation regimen of choice (Lan et al., 2013).

Treatment characteristics

The protocols used for standard ovarian stimulation were either the GnRH antagonist protocol or the long GnRH agonist protocol, as previously described (Bozdag et al., 2017; Vuong et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2019; Esteves et al., 2020). Patients received 150–450 IU daily subcutaneous injections of (i) recombinant FSH (rec-FSH), (ii) highly purified human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG), (iii) rec-FSH combined with hMG, or (iv) recombinant FSH combined with recombinant LH (rec-FSH + rec-LH 2:1 ratio). The ovarian stimulation regimen was mainly based on ovarian reserve, age of the woman and, if applicable, previous ovarian stimulation history. Ovarian response was monitored using transvaginal ultrasonography and serum estradiol measurements, and gonadotropin doses were adjusted as needed. Both fixed and flexible GnRH antagonist protocols were used.

Final oocyte maturation was carried out with either hCG or GnRH agonist. The oocytes collected were inseminated via IVF or ICSI, and zygotes were cultured until Day 3 or the blastocyst stage. ET was performed under ultrasound guidance and surplus embryos (or all viable embryos in case of elective embryo freezing) were vitrified. Elective freezing of all embryos was carried out in patients at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, in those with a premature increase in progesterone level on the hCG day (i.e. >1.5 ng/ml), a thin endometrium, accumulation of intrauterine fluid, and endometrial polyps. FET was performed in a hormone replacement treatment cycle without GnRH down-regulation. The number of embryos transferred was based on shared decision-making in compliance with national regulations. In fresh ET cycles, luteal phase support was provided by daily administration of intravaginal progesterone starting on the oocyte pick-up day or one day after and continued until the seventh week of gestation. In FET cycles, ET was scheduled on the 4th and the 6th day after the start of progesterone for the cleavage and blastocyst stage transfers, respectively, and luteal phase support was continued until 10–12 weeks of gestation. Pregnancy was monitored up to live birth delivery according to established practices. No other analyses concerning obstetric and neonatal outcomes were carried out.

Data input

Demographic data consisted of female age, BMI, infertility duration, infertility factor, and AFC and AMH values. The following treatment data were also collected: type of GnRH analogue, gonadotropin type, total gonadotropin dose, duration of stimulation, and trigger type. Embryo data included the numbers of oocytes retrieved, Metaphase II oocytes, embryos obtained, embryos transferred, cryopreserved embryos and ET cycles. Each individual-level input data was processed to produce the indicator of interest, that is, the patient classification (see below). Patients with incomplete data were excluded.

Patient classification

Patients were retrospectively classified into five groups based on the POSEIDON criteria as described below. Patients who did not meet any of the four POSEIDON groups were classified into a fifth group designated ‘non-POSEIDON’. The latter group was constituted by our control group of normal responders who had adequate ovarian reserve markers. We used AFC as the biomarker for classification because this parameter was available in 95.7% (n = 9073) of patients, whereas AMH levels were available in only 60.7% (n = 5750) of cases.

POSEIDON Group 1 (Group 1): Age <35 years, AFC ≥5, and a previous standard ovarian stimulation with <10 oocytes retrieved. This group was further separated into Subgroup 1a, consisting of patients with fewer than 4 oocytes retrieved, and Subgroup 1b, consisting of patients with 4–9 oocytes.

POSEIDON Group 2 (Group 2): Age ≥35 years, AFC ≥5, and a previous standard ovarian stimulation with <10 oocytes retrieved. This group was further separated into Subgroup 2a, consisting of patients with fewer than 4 oocytes retrieved, and Subgroup 2b, consisting of patients with 4–9 oocytes.

POSEIDON Group 3 (Group 3): Age <35 years and AFC <5.

POSEIDON Group 4 (Group 4): Age ≥35 years and AFC <5.

Non-POSEIDON (Group 5): Patients with AFC ≥5 and >9 oocytes retrieved. This group was further separated into Subgroup 5a, consisting of patients aged <35 years; and Subgroup 5b, consisting of patients aged 35 years and older.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was the CDR per aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle with at least one live birth, defined according to the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ICMART) as ‘…the number of deliveries with at least one live birth resulting from one initiated/aspiration ART cycle expressed per 100 patients, including all cycles in which fresh and/or frozen embryos were transferred, until one delivery with a live birth occurred or until all embryos were used, whichever occurred first’ (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2017). The delivery of a singleton or multiples was recorded as one delivery. Patients with no oocytes retrieved or embryos available for transfer were computed as failures.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as median and 25–75% interquartile range. Categorical data are described by the number of cases and percentages. Categorical and continuous data were analyzed using the Pearson Chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon test, respectively. The CDR survival functions were calculated using the non-parametric Kaplan–Meier method and non-censored values. The ‘time’ response in the model was the order of ETs; the patient was the observational unit, whereas live birth delivery was the event. Time-to-event plots and their correspondent tables were generated using three approaches. First, a time-to-event analysis of all POSEIDON patients, combined into a single group, and the control group of non-POSEIDON patients. Second, a similar analysis that included the four POSEIDON groups and the control group of non-POSEIDON patients. Third, a time-to-event analysis that included the above POSEIDON groups in which Groups 1 and 2 were further stratified into Subgroups ‘a’ and ‘b’, and non-POSEIDON patients stratified by age using the 35-year threshold. To verify whether the estimated survival functions differed across the groups, we used the pairwise log-rank statistics (Mantel 1966). P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction False Discovery Rate for multiple testing (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). P-values of <0.05 were considered indicative of a statistically significant difference. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between patient covariates and the CDR. Patient’s demographic data, treatment characteristics, embryonic data, and POSEIDON groups were the independent variables, whereas the CDR was the dependent variable. Only AMH was excluded from the list of patient covariates (see section ‘Datainput’) because of the high frequency of missing values. The independent variables were simultaneously entered into the model. The center effect was also considered. Overfitting was not a concern because the nature of our regression analysis was explanatory, primarily intended to illuminate possible associations between covariates and CDR rather than to form a model to predict CDR for new data. In particular, we aimed to determine a supposed relationship between the POSEIDON groups and CDR, adjusting for the effects of any other covariates. The likelihood of CDR according to POSEIDON groups is reported as odds ratios (OR) with SE and a 95% CI.

Computations were carried out using JMP® PRO 13 and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

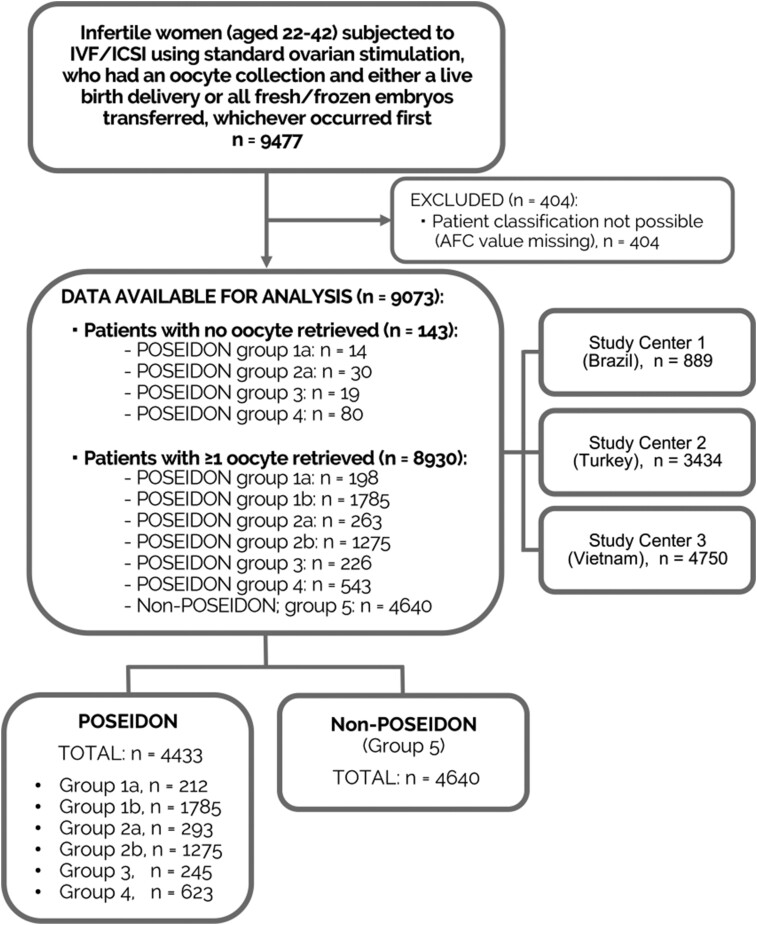

A total of 9073 patients were included in the study. Among these, 4433 (48.9%) patients met the POSEIDON criteria and were classified in one of the ‘low-prognosis’ groups (Fig. 1). Within the overall population, 6722 fresh and 3010 FET cycles were performed during the study. Of these, 3429 fresh ETs and 784 FETs were performed in POSEIDON patients. No oocytes were retrieved in 143 patients (1.6% of total studied population) (Group 1a = 14/212 (6.6%)); Group 2a = 30/293 (10.2%); Group 3 = 19/245 (7.7%); and Group 4 = 80/623 (12.8%)).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing total patient breakdown. POSEIDON (Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number) Group 1: younger (<35 years) unexpected poor or suboptimal responders; Subgroup 1a (poor): <4 oocytes retrieved, Subgroup 1b (suboptimal): 4–9 oocytes. POSEIDON Group 2: older (≥35 years) unexpected poor or suboptimal older responders; Subgroup 2a (poor): <4 oocytes retrieved; Subgroup 2b (suboptimal): 4–9 oocytes. POSEIDON Group 3: younger (<35 years) expected poor responder. POSEIDON Group 4: older (≥35 years) expected poor responders. Non-POSEIDON (Group 5): normal responders (>9 oocytes retrieved) with an adequate AFC (≥5).

Patient and treatment characteristics

Table I shows the baseline and treatment characteristics of the patients studied. Patients in POSEIDON Groups 1 and 3 were younger, had higher AFC values and a shorter infertility duration, respectively, than those in Groups 2 and 4. The aforementioned characteristics are expected because they are related to the attributes that define each POSEIDON group. By contrast, the non-POSEIDON group consisted predominantly of young patients with optimal AFC values.

Table I.

Baseline and treatment characteristics of patients stratified according to the POSEIDON criteria.

| POSEIDON Groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 n = 1997 |

Group 2 n = 1568 |

Group 3 n = 245 | Group 4 n = 623 | Total n = 4433 | Group 5 (Non-POSEIDON) n = 4640 | |||

| 1a n = 212 | 1b n = 1785 | 2a n = 293 | 2b n = 1275 | |||||

| Baseline characteristics: | ||||||||

| Female Age (years) | 31 [28; 33] | 31 [28; 34] | 39 [37–41] | 38 [36; 40] | 32 [30; 33] | 39 [37; 42] | 34 [31; 38] | 31 [28; 35] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22 [20–25] | 22 [20–26] | 22 [20–25] | 22 [21; 25] | 21 [20; 23] | 22 [20; 24] | 22 [20; 25] | 22 [20; 25] |

| Infertility duration (months) | 48 [24–72] | 48 [24–72] | 48 [24–96] | 60 [24; 102] | 48 [24–72] | 60 [24; 108] | 48 [24–84] | 48 [24–72] |

|

Infertility cause, n (%): |

||||||||

| Male factor | 47 (29.4) | 515 (28.9) | 43 (10.2) | 281 (22.0) | 26 (10.6) | 77 (12.4) | 989 (22.3) | 1771 (38.1) |

| Tubal | 13 (5.7) | 176 (9.8) | 30 (6.8) | 143 (11.2) | 22 (9.0) | 42 (6.7) | 426 (9.6) | 523 (11.2) |

| Endometriosis | 13 (5.7) | 91 (5.1) | 17 (5.8) | 44 (3.4) | 14 (5.7) | 61 (9.8) | 240 (5.4) | 152 (3.3) |

| Ovulatory | 17 (8.0) | 104 (5.8) | 10 (3.4) | 35 (2.7) | 5 (2.0) | 7 (1.1) | 178 (4.0) | 649 (14.0) |

| Unexplained | 49 (23.1) | 492 (27.6) | 71 (24.2) | 287 (22.5) | 86 (35.1) | 182 (29.2) | 1167 (26.3) | 1089 (23.6) |

| Combined* | 73 (34.4) | 407 (22.8) | 122 (41.6) | 485 (38.2) | 92 (37.6) | 254 (40.8) | 1433 (32.4) | 456 (9.8) |

| AFC (n) | 7 [6–12] | 11 [8–16] | 6 [5–8] | 8 [6; 11] | 3 [2; 4] | 3 [2; 4] | 8 [5; 12] | 17 [13; 22] |

| AMH (ng/mL)ϒ | 1.2 [0.7–2.8] | 2.5 [1.4–4.5] | 1.1 [0.6–1.9] | 1.6 [1.1; 2.8] | 0.7 [0.3; 1.2] | 0.7 [0.3; 1.1] | 1.4 [0.8; 2.8] | 4.8 [2.9; 7.7] |

| Treatment characteristics: | ||||||||

| Stimulation duration (days) | 9 [8–10] | 9 [8–10] | 9 [8–10] | 9 [8–10] | 10 [8–11] | 9.5 [8–11] | 9 [8–10] | 9 [8–10] |

| GnRH analogue: | ||||||||

| Antagonist | 149 (70.3) | 1261 (70.6) | 238 (81.2) | 927 (72.7) | 207 (84.5) | 574 (92.1) | 3356 (75.7) | 3817 (82.3) |

| Agonist | 63 (29.7) | 524 (29.4) | 55 (18.8) | 348 (27.3) | 38 (15.5) | 49 (7.9) | 1077 (24.3) | 823 (17.7) |

| Total gonadotropin dose (IU) |

2700 [2025–3450] |

2200 [1575–3000] |

3000 [2325–3450] |

2700 [2250–3450] |

3075 [2700–4050] |

3075 [2480–3900] |

2700 [2000–3450] |

2025 [1455–2700] |

| Gonadotropin type: | ||||||||

| rFSH | 56 (26.4) | 755 (42.3) | 56 (19.1) | 351 (27.5) | 55 (22.5) | 101 (16.2) | 1374 (31.0) | 2451 (52.8) |

| rFSH+hMG | 134 (63.2) | 864 (48.4) | 160 (54.6) | 706 (55.4) | 156 (63.7) | 395 (63.4) | 2415 (54.5) | 1865 (40.2) |

| rFSH+rLH | 11 (5.2) | 92 (5.1) | 71 (24.2) | 179 (14.1) | 24 (9.8) | 110 (17.7) | 487 (11.0) | 259 (5.6) |

| hMG | 11 (5.2) | 74 (4.1) | 6 (2.0) | 39 (3.0) | 10 (4.0) | 17 (2.7) | 157 (3.5) | 65 (1.4) |

| Trigger type: | ||||||||

| hCG | 208 (98.1) | 1719 (96.3) | 262 (89.4) | 1213 (95.1) | 234 (95.5) | 577 (92.6) | 4213 (95.0) | 3712 (80.0) |

| GnRH agonist | 4 (1.9) | 66 (3.7) | 31 (10.6) | 62 (4.9) | 11 (4.5) | 46 (7.4) | 220 (5.0) | 928 (20.0) |

| Elective embryo freezing | 16 (7.5) | 180 (10.1) | 36 (12.3) | 208 (16.3) | 17 (6.9) | 69 (11.0) | 526 (11.9) | 1083 (23.3) |

Values are median and interquartile range or number and percentage. AFC, antral follicle count; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; rFSH, recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone; HMG, human menopausal gonadotropin; rLH, recombinant luteinizing hormone.

Group 1a: Younger (<35 years) unexpected poor responder (<4 oocytes retrieved); Group 1b: Younger (<35 years) unexpected suboptimal responder (4–9 oocytes retrieved); POSEIDON group 2a: Older (≥35 years) unexpected poor responder; Group 2b: Older unexpected suboptimal responder; Group 3: Younger expected poor responder; Group 4: Older expected poor responder; Group 5: Non-POSEIDON: normal responders (>9 oocytes retrieved) with an adequate AFC (≥5).

Based on data of 5750 patients.

Presence of both a male and a female factor.

Infertility due to male factor occurred more frequently in younger POSEIDON patients (Groups 1 and 3) and their non-POSEIDON counterparts, whereas a female infertility factor was commonly found in older POSEIDON patients (Groups 2 and 4). The most common ovarian stimulation regimen across all POSEIDON groups consisted of a GnRH antagonist, the association between rec-FSH and hMG, and an hCG trigger. Non-POSEIDON patients were more frequently treated with rec-FSH monotherapy. Among these patients, GnRH agonist trigger and elective frozen ET were relatively common.

IVF/ICSI outcomes are reported in Table II. Overall, the numbers of oocytes retrieved and embryos obtained were ~2-fold lower in POSEIDON patients than in their non-POSEIDON counterparts. In addition, the percent in whom ET was cancelled because of a lack of oocytes/embryos was higher in POSEIDON patients (11.1%) than in non-POSEIDON patients (1.2%). The frequency of patients who had undergone more than one ET cycle due to the availability of supernumerary frozen embryos was lower in POSEIDON patients (8.7%) than non-POSEIDON patients (28.2%). Within the POSEIDON groups, the numbers of frozen embryos and ET cycles were higher in unexpected suboptimal responders (Groups 1b and 2b) than in unexpected poor responders (Groups 1a and 2a).

Table II.

IVF/ICSI outcomes of studied patients stratified according to the POSEIDON criteria.

| POSEIDON Groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 n = 1997 |

Group 2 n = 1568 |

Group 3 n = 245 | Group 4 n = 623 | Total n = 4433 | Group 5 (Non-POSEIDON) n = 4640 | |||

| 1a n = 212 | 1b n = 1785 | 2a n = 293 | 2b n = 1275 | |||||

| N. Oocytes retrieved | 3 [2; 3] | 7 [6; 8] | 2 [2; 3] | 7 [5; 8] | 3 [2; 5] | 3 [1; 4] | 6 [4; 8] | 14 [12; 18] |

| N. Metaphase II oocytes | 2 [1; 3] | 5 [4; 7] | 2 [1; 2] | 5 [4; 7] | 2 [1; 4] | 2 [1; 3] | 4 [3; 6] | 11 [9; 14] |

| N. Embryos obtained | 1.5 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 4] | 1 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 3] | 2 [1; 3] | 1 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 3] | 5 [2; 8] |

| N. Embryos transferred | 1 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 2] | 1 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 2] | 2 [1; 2] | 2 [1; 2] | 2 [2; 2] | 2 [2; 2] |

| N. (%) Patients with surplus frozen embryos after first ET | 3 (1.4) | 252 (14.1) | 1 (0.3) | 180 (14.1) | 15 (6.1) | 15 (2.4) | 466 (10.5) | 1716 (37.0) |

| N. Frozen embryos | 0 [0; 0] | 1 [0; 2] | 0 [0; 0] | 1 [0; 2] | 0 [0; 0] | 0 [0; 0] | 0 [0; 1] | 2 [1; 4] |

| Type of transfer, n (%) | ||||||||

| Fresh only | 157 (74.1) | 1417 (79.4) | 162 (55.3) | 901 (70.7) | 154 (62.9) | 365 (58.6) | 3156 (71.2) | 2355 (50.8) |

| FET only | 15 (7.1) | 180 (10.1) | 33 (11.3) | 195 (15.3) | 17 (6.9) | 69 (11.1) | 511 (11.5) | 1288 (27.8) |

| Fresh and FET | 2 (0.9) | 142 (7.9) | 1 (0.3) | 119 (9.3) | 4 (1.6) | 7 (1.1) | 273 (6.2) | 938 (20.2) |

| No transferϒ | 38 (17.9) | 46 (2.6) | 97 (33.1) | 60 (4.7) | 70 (28.6) | 182 (29.2) | 493 (11.1) | 59 (1.2) |

| N. (%) Patients >1 ET cycle | 2 (0.9) | 202 (11.3) | 1 (0.3) | 155 (12.2) | 12 (4.9) | 13 (2.1) | 385 (8.7) | 1309 (28.2) |

| Pregnancy outcome: | ||||||||

| CDR*, n (%) | 59 (27.8) | 854 (47.8) | 41 (14.0) | 389 (30.5) | 72 (29.4) | 78 (12.5) | 1493 (33.7) | 2347 (50.6) |

| Conception mode∞, n (%) IVF/ICSI fresh | 53 (89.8) | 692 (77.3) | 33 (78.5) | 299 (76.9) | 63 (87.5) | 62 (79.5) | 1202 (80.5) | 1352 (57.6) |

| Conception mode∞, n (%) IVF/ICSI FET | 6 (10.2) | 162 (22.7) | 8 (19.5) | 90 (23.1) | 9 (12.5) | 16 (20.5) | 291 (19.5) | 995 (42.4) |

| LBR per transfer fresh (%) | 33.3 | 44.4 | 20.2 | 293 | 39.9 | 16.7 | 35.1 | 41.0 |

| LBR per transfer FET (%) | 35.3 | 50.3 | 23.5 | 28.7 | 42.8 | 23.2 | 37.1 | 44.7 |

| N. ET/patient | 1 [1; 1] | 1 [1; 1] | 1 [0; 1] | 1 [1; 1] | 1 [0; 1] | 1 [0; 1] | 1 [1; 1] | 2 [1; 3] |

Values are median and interquartile range or number and percentage. ET, embryo transfer; FET, frozen-thawed ET; LBR, live birth rate.

CDR: cumulative delivery rate from one aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle, considering the number of deliveries with at least one live birth, expressed per 100 patients, including all cycles in which fresh and/or frozen embryos were transferred, until one delivery with a live birth occurred or all embryos were used.

Include patients with no oocytes retrieved, no zygote or embryo developed, or no post-warming viable embryo.

Among patients who achieved a live birth delivery.

Group 1a: Younger (<35 years) unexpected poor responder (<4 oocytes retrieved); Group 1b: Younger (<35 years) unexpected suboptimal responder (4–9 oocytes retrieved); POSEIDON Group 2a: Older (≥35 years) unexpected poor responder; Group 2b: Older unexpected suboptimal responder; Group 3: Younger expected poor responder; Group 4: Older expected poor responder; Group 5: Non-POSEIDON: normal responders (>9 oocytes retrieved) with an adequate AFC (≥5).

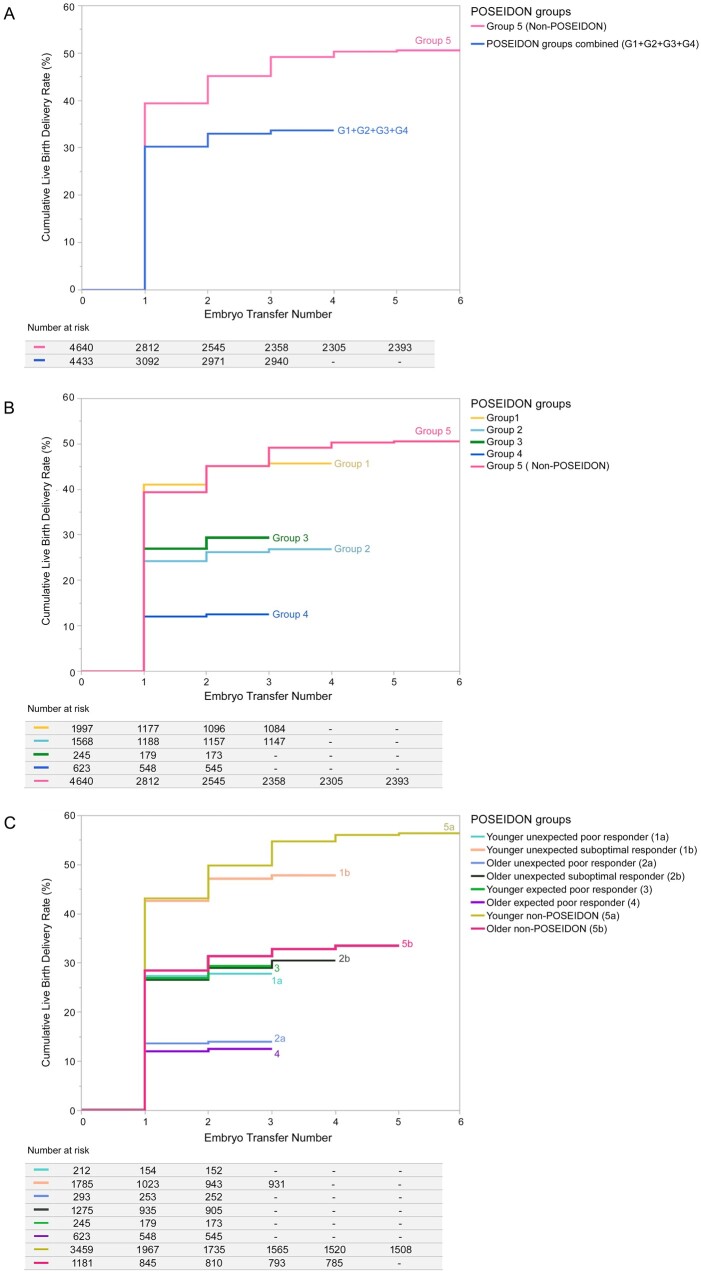

Cumulative delivery rate per aspiration cycle

A total of 3840 (42.3%) patients achieved a live birth delivery after one or more ET(s) from one aspirated cycle (Table II). Figure 2 shows the CDR survival plots for each patient group, and Table III shows the results of pairwise group comparisons. The CDR was lower in POSEIDON patients than in non-POSEIDON patients (33.7% vs 50.6%, P < 0.001). Among POSEIDON groups, those including the younger population had the highest CDRs per aspirated cycle (Group 1: 45.7%; Group 3: 29.4%). Within the groups of unexpected responders (Groups 1 and 2), CDRs were significantly higher in suboptimal responders (Group 1b: 47.8%; Group 2b: 30.5%) than in poor responders (Group 1a: 27.8%; Group 2a: 14.0%; P = 0.0004). CDR was lowest in older POSEIDON patients with an expected poor response (Group 4: 12.5%). Within the non-POSEIDON group, CDR was lower in older (≥35 years) than in their younger (<35 years) counterparts (56.4% vs 34.8%, P = 0.004). However, CDR in older (≥35 years) non-POSEIDON patients was higher than that of POSEIDON suboptimal responders of a similar age stratum (Group 2b: 30.5%; P = 0.03) (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Cumulative delivery plots and their correspondent tables. Patients were stratified according to the POSEIDON criteria, and the time-to-event plots were generated by (A) all POSEIDON patients—combined into a single group—and the control group of non-POSEIDON patients, (B) the four POSEIDON groups and the control group of non-POSEIDON patients, and (C) the four POSEIDON groups, in which Groups 1 and 2 were further stratified in Subgroups ‘a’ and ‘b’, and non-POSEIDON patients further stratified by age using the 35-year threshold. Cumulative delivery rate survival functions were calculated using the nonparametric Kaplan–Meier method and non-censored values. The ‘time’ response was the order of embryo transfers (ETs); the patient was the observational unit, and live birth delivery was the event. The survival tables detail the number of patients who failed to achieve a live birth delivery (number at risk). The tables are sectioned (columns) by each ET from one aspirated IVF/ICSI cycle (see ET order, 1, 2., 3… on the ‘x’ axis of correspondent survival plots), and each group occupies its own row in the tables. The start of the tables (left column) indicates the number of patients who commenced treatment and had an oocyte pick-up. The lines in each plot represent the cumulative proportion of patients achieving a live born from the start of treatment until the ‘time’ response.

Table III.

Pairwise log-rank comparisons of the cumulative delivery plots.

|

Adjusted P-values (Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1a | Group 1b | Group 2a | Group 2b | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 1 (1a and 1b combined) | Group 2 (2a and 2b combined) | All POSEIDON groups combined | Group 5 (Non- POSEIDON) | |

| Group 1a | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group 1b | 0.0004* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group 2a | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group 2b | 0.94 | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group 3 | 0.94 | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.73 | – | – | 0.0004* | 0.61 | – | – |

| Group 4 | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.71 | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | – | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | – | – |

| Group 1 (1a and 1b combined) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Group 2 (2a and 2b combined) | – | – | – | – | 0.0004* | – | – | – | ||

| All POSEIDON groups combined | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.0004* |

| Group 5 (Non-POSEIDON) | 0.0004* | 0.0444* | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | 0.0004* | – | – |

Group 1a: Younger (<35 years) unexpected poor responder (<4 oocytes retrieved); Group 1b: Younger (<35 years) unexpected suboptimal responder (4–9 oocytes retrieved); POSEIDON Group 2a: Older (≥35 years) unexpected poor responder; Group 2b: Older unexpected suboptimal responder; Group 3: Younger expected poor responder; Group 4: Older expected poor responder; Group 5: Non-POSEIDON: normal responders (>9 oocytes retrieved) with an adequate AFC (≥5); All POSEIDON groups: Groups 1–4.

Adjusted P-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction False Discovery Rate. *P-values <0.05 indicate a statistically significant difference in cumulative delivery rate from one aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle.

Logistic regression analysis

A significant regression equation was found between patient co-variates and CDR (Chi-square = 2196.09; degrees of freedom = 22; P < 0.0001) with an R-square of 0.215. POSEIDON (sub)groups, number of embryos obtained, number of ET per patient, number of oocytes retrieved, female age, duration of infertility and BMI were the relevant predictors for CDR (P < 0.001). A study center effect was not observed in the model. Infertility factor, AFC, GnRH analogue, gonadotropin type, total gonadotropin dose, duration of stimulation, trigger type, and type of transfer (fresh or frozen–thawed) were not significantly associated with CDR.

Table IV shows the adjusted ORs with their 95% CI for CDRs among patient groups. Non-POSEIDON patients were used as the reference category. Overall, our model indicated that the classification ‘POSEIDON’ was an independent negative predictor for CDR per aspiration cycle.

Table IV.

Adjusted odds ratio for cumulative delivery rates from one aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle according to POSEIDON groups.

| Patient category | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-POSEIDON (Group 5)* | 1 | – | – |

| POSEIDON Group 1a | 0.623 | 0.471-0.782 | 0.031 |

| POSEIDON Group 1b | 0.812 | 0.566-1.070 | 0.110 |

| POSEIDON Group 1 (a + b combined) | 0.742 | 0.571-0.922 | 0.037 |

| POSEIDON Group 2a | 0.514 | 0.343-0.894 | 0.015 |

| POSEIDON Group 2b | 0.594 | 0.453-0.871 | 0.001 |

| POSEIDON Group 2 (a + b combined) | 0.688 | 0.547-0.866 | 0.001 |

| POSEIDON Group 3 | 0.709 | 0.534-0.952 | 0.031 |

| POSEIDON Group 4 | 0.378 | 0.259-0.550 | <0.001 |

| All POSEIDON groups combined | 0.407 | 0.282-0.535 | <0.001 |

Reference category.

Group 1a: Younger (<35 years) unexpected poor responder (<4 oocytes retrieved); Group 1b: Younger (<35 years) unexpected suboptimal responder (4–9 oocytes retrieved); POSEIDON group 2a: Older (≥35 years) unexpected poor responder; Group 2b: Older unexpected suboptimal responder; Group 3: Younger expected poor responder; Group 4: Older expected poor responder; Group 5: Non-POSEIDON: normal responders (>9 oocytes retrieved) with an adequate AFC (≥5).

Discussion

This multicenter, multinational observational cohort study demonstrates that CDR per aspirated IVF/ICSI cycle is ∼50% lower in women who meet the POSEIDON criteria than in normal responders who have adequate ovarian reserve markers. This finding substantiates the concept that POSEIDON patients have a lower prognosis after ART treatment than normal responders. The effect size varied across POSEIDON groups, and the differences were primarily related to female age and number of oocytes retrieved, which underline the importance of oocyte quality and quantity. Younger POSEIDON patients (Groups 1 and 3) were less affected than their older counterparts (Groups 2 and 4); the former achieved a CDR of ∼44% after one stimulated IVF/ICSI cycle. By contrast, the CDR was the lowest (∼12%) in older women with an abnormal ovarian reserve (Group 4). Within the unexpected poor/suboptimal responder women (Groups 1 and 2), the CDR was twice higher in suboptimal responders (4–9 oocytes; Subgroups 1b and 2b) than in poor responder counterparts (<4 oocytes retrieved; Subgroups 1a and 2a).

Interpretation of findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to assess the CDR from one aspiration cycle in POSEIDON patients according to the ICMART terminology. We included a control group of normal prognosis patients for comparison and evaluated CDRs in POSEIDON patients both overall and by group. We also evaluated the CDR in unexpected poor/suboptimal POSEIDON patients (Groups 1 and 2) based on the number of oocytes retrieved. Lastly, we assessed the impact of patient covariates on the CDR using logistic regression analysis.

Our findings indicate that in POSEIDON patients, the inverse relationship between female age and CDR after one aspiration cycle is likely due to oocyte quality. Moreover, the CDR ultimately obtained was also affected by oocyte quantity. Using a large cohort of normal responders with an adequate ovarian reserve as a comparator, we found a remarkable difference in the CDR between POSEIDON and non-POSEIDON groups. The lower CDR in POSEIDON patients is not surprising because fewer oocytes were retrieved and fewer embryos were obtained in these patients after one stimulation cycle, thereby limiting the number of supernumerary cryopreserved embryos for subsequent transfers. Yet, the impact of the POSEIDON classification on CDR was attenuated in younger POSEIDON patients by the well-known protective age-related effect exerted on oocyte/embryo quality in these women (Cimadomo et al., 2018; Esteves et al., 2019b). In addition, an increased number of oocytes retrieved was associated with a better CDR. However, the effect of oocyte number on the CDR of POSEIDON patients was age-dependent. Indeed, younger (<35 years) unexpected suboptimal responders (4–9 oocytes) achieved ∼1.5× higher CDRs than their older (≥35 years) counterparts. While genetic and treatment factors may be involved in the pathophysiology of poor/suboptimal response in women with adequate ovarian reserve markers (Alviggi et al., 2018), oocyte quality does not seem to be affected.

We also found that the number of oocytes obtained was associated with the number of embryos generated and cryopreserved. Our data show that 37% of non-POSEIDON patients had supernumerary vitrified embryos. In addition, 14% of suboptimal responders (Subgroups 1b and 2b) had supernumerary vitrified embryos, i.e. four times higher (vs 3.4%) than that observed in expected poor responders (Groups 3 and 4) and ~17x higher (vs 0.8%) than in unexpected poor responders (Subgroups 1a and 2a). Consequently, more suboptimal responder patients than poor responder patients received a subsequent ET after the first failed cycle, thereby increasing the CDR in this patient subset. Our findings are consistent with studies showing that female age and number of oocytes retrieved play a critical role in cumulative pregnancy estimations (Ji et al., 2013; Drakopoulos et al., 2016; McLernon et al., 2016). While the positive impact of supernumerary embryos on the CDR depends on the availability of efficient cryopreservation protocols, embryo vitrification results in optimal success rates and is widely available (Sciorio and Esteves, 2020).

Previous trials have reported CDRs in POSEIDON patients (Leijdekkers et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020), but various CDR definitions used in these studies hampers data comparison. Leijdekkers et al. (2019) published landmark work on this matter using data from the OPTIMIST Dutch multicenter observational cohort study. They used AMH for patient classification and reported a CDR of 56% in POSEIDON patients, markedly higher than in our study (∼34%). They also reported that young POSEIDON patients achieved CDRs similar to normal responders, suggesting that oocyte quantity had limited importance for reproductive outcomes in younger POSEIDON patients. (Leijdekkers et al., 2019). However, the authors reported cumulative live birth rates over multiple complete IVF/ICSI cycles during 18 months of treatment which might inflate cumulative pregnancy estimations due to cycles’ repetition (Brandes et al., 2009; Esteves et al., 2019c).

Along these lines, Li et al. (2019) in a large single-center retrospective analysis, reported a CDR of 43% per initiated cycle in POSEIDON patients. However, no control group of normal responders was available for comparisons, and the effect of oocyte number on unexpected poor/suboptimal responders was not evaluated. Moreover, a recent sizeable single-center study showed that CDRs per started cycle varied across POSEIDON groups and were lower overall than in non-POSEIDON controls (Yang et al., 2020). In this study, Yang et al. reported that both female age and oocyte quantity affected the CDR of POSEIDON patients. Nevertheless, the authors used various ovarian stimulation protocols and it is unclear whether AMH, AFC, or both markers were used for patient classification. Moreover, they did not report the number of POSEIDON patients with supernumerary embryos for freezing, nor the outcomes of FET cycles, thus, limiting the interpretation of the effect of oocyte quantity on cumulative pregnancy data.

Clinical implications

The reporting of cumulative delivery rates after one stimulation cycle in real-world settings using a standardized classification system such as the POSEIDON criteria has important clinical implications. First, it may provide useful counseling tools regarding pregnancy prospects for ART patients and, thus, help to establish realistic expectations. Second, it may reveal causal associations between patient characteristics and the ‘low-prognosis’ condition, which may have implications for research and clinical practice. Moreover, the present findings may help policymakers and healthcare professionals implement measures to attenuate the risk of ‘low-prognosis’ and potentially refine reproductive planning. Awareness campaigns emphasizing the adverse effects of advanced maternal age and diminished ovarian reserve have been explored, as has the potential positive impact of lifestyle changes on pregnancy (Vause et al., 2009; Deatsman et al., 2016; Revelli et al., 2016; Kudesia et al., 2018; Salih et al., 2019; Mintziori et al., 2020).

Furthermore, specific interventions might be beneficial in relevant subpopulations. Although the medical management of low-prognosis patients remains incredibly challenging, recent reports suggest that these patients may be managed more efficiently. In fact, in a retrospective study that included POSEIDON Group 4 patients, Chen et al. found that patients pre-treated with dehydroepiandrosterone for 12 weeks achieved higher oocyte yields and embryo numbers than those who were not, and these improvements were associated with higher pregnancy rates (Chen et al., 2020). Pretreatment with coenzyme Q10 for 60 days has also been shown to increase the number of high-quality embryos in a randomized controlled trial including 186 POSEIDON Group 3 patients (Xu et al. 2018). Chern et al. reported that the dual trigger (vs hCG trigger) was associated with a higher number of oocytes retrieved and embryos obtained, ultimately resulting in increased live birth rates in POSEIDON Group 4 patients (Chern et al., 2020). Similarly, Li et al. (2020) showed that the long agonist protocol was associated with better clinical outcomes in younger patients (POSEIDON Groups 1 and 3) than the GnRH antagonist protocol. Lastly, Berker et al. (2021) retrospectively evaluated the clinical utility of providing LH-activity supplementation to recombinant FSH stimulation in a cohort of 558 women, consisting mainly of POSEIDON Groups 3 and 4. In the latter study, the addition of hMG to recombinant FSH from the early follicular phase was associated with higher live birth rates (21.9% vs 11.6%, P = 0.03) per initiated cycle than with recombinant FSH alone.

Limitations

This report is observational with the inherent limitations of studies of this nature. Efforts were made to check for confounders by selecting study centers sharing similar patient evaluation and treatment practices. However, POSEIDON patients were classified based solely on AFC values, obtained using 2-dimension transvaginal ultrasound and assessed by different operators and with different machines. Although this technique may yield different results even when used by experienced operators (Deb et al., 2009), its agreement with AMH to classify POSEIDON patients was shown to be adequate (Esteves et al., 2021b). In this latter study, we showed that the degree of agreement between AFC and AMH in classifying patients according to POSEIDON groups was strong (kappa = 0.802), and nearly 74% of individuals were classified under the same group using both biomarkers. Despite that, we cannot exclude the possibility that variations in AFC technique and reporting may have influenced the proportion of patients allocated to each category. While the three-dimension technique and the offline analysis of stored images have been advocated to increase AFC reproducibility (Deb et al., 2009), their clinical use to increase the accuracy of the POSEIDON classification remains unknown.

Another limitation relates to the fact that patients were classified into POSEIDON groups a posteriori and therefore treatment regimens were not tailored accordingly. Thus, we cannot exclude that the gonadotropin dose influenced patient classification. Although our data support the finding that the CDR is increased in patients with a high oocyte yield, we cannot provide any guidance on regimens to increase oocyte quantity because patients were treated according to the practices prevailing in each center. Notably, our patient population was overwhelmingly treated with the GnRH antagonist protocol and all patients received at least 150 IU of gonadotropins daily. Moreover, patients with a high oocyte yield are those most likely to have an intrinsically better prognosis. In this context, prospective interventional trials are needed to assess whether treatment regimens might increase both oocyte yield and the CDR in POSEIDON patients. Notwithstanding the above limitations, we are confident that the present data provide a righteous representation of real-world IVF practices.

Conclusion

The CDR per aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle of low-prognosis patients undergoing standard ovarian stimulation is on average ∼50% lower than that of normal responders and varies across POSEIDON groups. Differences were primarily determined by female age and number of oocytes retrieved, reflecting the importance of oocyte quality and quantity. Our data substantiate the validity of the POSEIDON criteria in identifying relevant subpopulations of patients with a low-prognosis in IVF/ICSI treatment. The POSEIDON criteria may be helpful for counseling, clinical management and research. Efforts in terms of early diagnosis, prevention and identification of specific interventions that might benefit POSEIDON patients are warranted.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction online.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the text and its supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Luciana Abreu (Statistika Consulting) for helping with data compilation and statistical analysis.

Contributor Information

Sandro C Esteves, ANDROFERT, Andrology and Human Reproduction Clinic, Campinas, Brazil.

Hakan Yarali, Anatolia IVF, Ankara, Turkey; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

Lan N Vuong, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; IVFMD, My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; HOPE Research Center, My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

José F Carvalho, Statistika Consulting, Campinas, Brazil.

İrem Y Özbek, Anatolia IVF, Ankara, Turkey.

Mehtap Polat, Anatolia IVF, Ankara, Turkey.

Ho L Le, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; IVFMD, My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Toan D Pham, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; IVFMD, My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Tuong M Ho, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; IVFMD, My Duc Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Peter Humaidan, Fertility Clinic Skive, Skive Regional Hospital, Skive, Denmark.

Carlo Alviggi, Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Science and Odontostomatology, University of Naples, Federico II, Naples, Italy.

Authors’ roles

S.C.E. designed and coordinated the study and helped with data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. H.Y. and L.N.V. designed the study, helped with data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. J.F.C. carried out the statistical analyses and helped with data interpretation. I.Y.O., M.P., H.L.L., T.D.P. and T.M.H. participated in data acquisition and in the revision of the article for critical intellectual content. P.H. and C.A. helped to design the study, performed data interpretation, and revised the article for critical intellectual content. All authors contributed intellectually to the writing and revision of the manuscript, approved the final version, and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by an unrestricted investigator-sponsored study grant (MS200059_0013) from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest

S.C.E. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck and lecture fees from Merck and Med.E.A. H.Y. declares receipt of payment for lectures from Merck and Ferring. L.N.V. receives speaker fees and conferences from Merck, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) and Ferring and research grants from MSD and Ferring. J.F.C. declares receipt of statistical services fees from ANDROFERT Clinic. T.M.H. received speaker fees and conferences from Merck, MSD and Ferring. P.H. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck, Ferring, Gedeon Richter and IBSA and lecture fees from Merck, Gedeon Richter and Med.E.A. C.A. declares receipt of unrestricted research grants from Merck and lecture fees from Merck. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Alviggi C, Conforti A, Esteves SC, Vallone R, Venturella R, Staiano S, Castaldo E, Andersen CY, De Placido G.. Understanding ovarian hypo-response to exogenous gonadotropin in ovarian stimulation and its new proposed marker-the Follicle-To-Oocyte (FOI) index. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg J.. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc: Ser B 1995;V57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berker B, Şükür YE, Özdemir EÜ, Özmen B, Sönmezer M, Atabekoğlu CS, Aytaç R.. Human menopausal gonadotropin commenced on early follicular period increases live birth rates in POSEIDON group 3 and 4 poor responders. Reprod Sci 2021;28:488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdag G, Polat M, Yarali I, Yarali H.. Live birth rates in various subgroups of poor ovarian responders fulfilling the Bologna criteria. Reprod Biomed Online 2017;34:639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes M, van der Steen JO, Bokdam SB, Hamilton CJ, de Bruin JP, Nelen WL, Kremer JA.. When and why do subfertile couples discontinue their fertility care? A longitudinal cohort study in a secondary care subfertility population. Hum Reprod 2009;24:3127–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans FJ, de Ziegler D, Howles CM, Gougeon A, Trew G, Olivennes F.. The antral follicle count: practical recommendations for better standardization. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1044–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang H, Zhou H, Bai H, Wang T, Shi W, Shi J.. Follicular output rate and Follicle-to-Oocyte Index of low prognosis patients according to POSEIDON criteria: a retrospective cohort study of 32,128 treatment cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern CU, Li JY, Tsui KH, Wang PH, Wen ZH, Lin LT.. Dual-trigger improves the outcomes of in vitro fertilization cycles in older patients with diminished ovarian reserve: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0235707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimadomo D, Fabozzi G, Vaiarelli A, Ubaldi N, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L.. Impact of maternal age on oocyte and embryo competence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunas L, Roberts SA, Yates AP, Smith A, Fitzgerald C, Pemberton PW.. Modification of the Beckman-Coulter second-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay protocol improves the reliability of serum antimüllerian hormone measurement. Fertil Steril 2015;103:554–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatsman S, Vasilopoulos T, Rhoton-Vlasak A.. Age and fertility: a study on patient awareness. JBRA Assist Reprod 2016;20:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb S, Jayaprakasan K, Campbell BK, Clewes JS, Johnson IR, Raine-Fenning NJ.. Intraobserver and interobserver reliability of automated antral follicle counts made using three-dimensional ultrasound and SonoAVC. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;33:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakopoulos P, Blockeel C, Stoop D, Camus M, de Vos M, Tournaye H, Polyzos NP.. Conventional ovarian stimulation and single embryo transfer for IVF/ICSI. How many oocytes do we need to maximize cumulative live birth rates after utilization of all fresh and frozen embryos? Hum Reprod 2016;31:370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Alviggi C, Humaidan P, Fischer R, Andersen CY, Conforti A, Bühler K, Sunkara SK, Polyzos NP, Galliano D.. et al. The POSEIDON criteria and its measure of success through the eyes of clinicians and embryologists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019a;10:814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Carvalho JF, Martinhago CD, Melo AA, Bento FC, Humaidan P, Alviggi C; POSEIDON (Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number) Group .Estimation of age-dependent decrease in blastocyst euploidy by next generation sequencing: development of a novel prediction model. Panminerva Med 2019b;61:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Roque M, Sunkara SK, Conforti A, Ubaldi FM, Humaidan P, Alviggi C.. Oocyte quantity, as well as oocyte quality, plays a significant role for the cumulative live birth rate of a POSEIDON criteria patient. Hum Reprod 2019c;34:2555–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Yarali H, Ubaldi FM, Carvalho JF, Bento FC, Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Özbek İY, Polat M, Bozdag G.. et al. Validation of ART calculator for predicting the number of metaphase II oocytes required for obtaining at least one euploid blastocyst for transfer in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;10:917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Conforti A, Sunkara SK, Carbone L, Picarelli S, Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Rienzi L, Ubaldi FM, Zullo F.. et al. Improving reporting of clinical studies using the POSEIDON criteria: POSORT guidelines. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne )2021a;12: 587051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves SC, Yarali H, Vuong LN, Carvalho JF, Özbek İY, Polat M, Le HL, Pham TD, Ho TM.. Antral follicle count and anti-Müllerian hormone to classify low-prognosis women under the POSEIDON criteria: a classification agreement study of over 9000 patients. Hum Reprod 2021b;36:1530–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R, Nakano FY, Roque M, Bento FC, Baukloh V, Esteves SC.. A quality management approach to controlled ovarian stimulation in assisted reproductive technology: the "Fischer protocol". Panminerva Med 2019;61:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humaidan P, Alviggi C, Fischer R, Esteves SC.. The novel POSEIDON stratification of ‘Low prognosis patients in Assisted Reproductive Technology’ and its proposed marker of successful outcome. F1000Res 2016;5:2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Liu Y, Tong XH, Luo L, Ma J, Chen Z.. The optimum number of oocytes in IVF treatment: an analysis of 2455 cycles in China. Hum Reprod 2013;28:2728–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudesia R, Wu H, Hunter Cohn K, Tan L, Lee JA, Copperman AB, Yurttas Beim P.. The effect of female body mass index on in vitro fertilization cycle outcomes: a multi-center analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018;35:2013–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan VT, Linh NK, Tuong HM, Wong PC, Howles CM.. Anti-Müllerian hormone versus antral follicle count for defining the starting dose of FSH. Reprod Biomed Online 2013;27:390–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leijdekkers JA, Eijkemans MJC, van Tilborg TC, Oudshoorn SC, van Golde RJT, Hoek A, Lambalk CB, de Bruin JP, Fleischer K, Mochtar MH,. et al. ; OPTIMIST Study Group. Cumulative live birth rates in low-prognosis women. Hum Reprod 2019;34:1030–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Ye T, Kong H, Li J, Hu L, Jin H, Su Y, Li G.. Efficacies of different ovarian hyperstimulation protocols in poor ovarian responders classified by the POSEIDON criteria. Aging (Albany NY )2020;12:9354–9364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li X, Yang X, Cai S, Lu G, Lin G, Humaidan P, Gong G.. Cumulative live birth rates in low prognosis patients according to the POSEIDON criteria: an analysis of 26,697 cycles of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A, McLernon D, Bhattacharya S.. Cumulative live birth rate: time for a consensus? Hum Reprod 2015;30:2703–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS.. Cumulative live-birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med 2009;360:236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLernon DJ, Steyerberg EW, Te Velde ER, Lee AJ, Bhattacharya S.. Predicting the chances of a live birth after one or more complete cycles of in vitro fertilisation: population based study of linked cycle data from 113,873 women. BMJ 2016;355:i5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintziori G, Nigdelis MP, Mathew H, Mousiolis A, Goulis DG, Mantzoros CS.. The effect of excess body fat on female and male reproduction. Metabolism 2020;107:154193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moragianni VA, Penzias AS.. Cumulative live-birth rates after assisted reproductive technology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2010;22:189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund G, Fauser BC, Macklon NS, Ombelet W, Nygren K, Frydman R;. Rotterdam ISMAAR Consensus Group on Terminology for Ovarian Stimulation for IVF. The ISMAAR proposal on terminology for ovarian stimulation for IVF. Hum Reprod 2007;22:2801–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian Stimulation T, Bosch E, Broer S, Griesinger G, Grynberg M, Humaidan P, Kolibianakis E, Kunicki M, La MA, Lainas G.. et al. ESHRE guideline: ovarian stimulation for IVF/ICSI†. Hum Reprod Open 2020;2020:hoaa009. Erratum in: Hum Reprod Open 2020;2020:hoaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyzos NP, Drakopoulos P, Parra J, Pellicer A, Santos-Ribeiro S, Tournaye H, Bosch E, Garcia-Velasco J.. Cumulative live birth rates according to the number of oocytes retrieved after the first ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multicenter multinational analysis including ∼15,000 women. Fertil Steril 2018;110:661–670.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poseidon Group (Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number), Alviggi C, Andersen CY, Buehler K, Conforti A, De Placido G, Esteves SC, Fischer R, Galliano D, Polyzos NP.. et al. A new more detailed stratification of low responders to ovarian stimulation: from a poor ovarian response to a low prognosis concept. Fertil Steril 2016;105:1452–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelli A, Razzano A, Delle Piane L, Casano S, Benedetto C.. Awareness of the effects of postponing motherhood among hospital gynecologists: is their knowledge sufficient to offer appropriate help to patients? J Assist Reprod Genet 2016;33:215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih Joelsson L, Elenis E, Wanggren K, Berglund A, Iliadou AN, Cesta CE, Mumford SL, White R, Tydén T, Skalkidou A.. Investigating the effect of lifestyle risk factors upon number of aspirated and mature oocytes in in vitro fertilization cycles: interaction with antral follicle count. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciorio R, Esteves SC.. Clinical utility of freeze-all approach in ART treatment: a mini-review. Cryobiology 2020;92:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Zhou H, Tian L, Zhao Z, Zhang W, Shi J.. Cumulative live birth rates of good and low prognosis patients according to POSEIDON criteria: a single center analysis of 18,455 treatment cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R, Seifer DB.. Ovarian reserve testing: a user's guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:W163–W194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vause TDR, Jones L, Evans M, Wilkie V, Leader A.. Pre-conception health awareness in infertility patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31:717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermey BG, Chua SJ, Zafarmand MH, Wang R, Longobardi S, Cottell E, Beckers F, Mol BW, Venetis CA, D'Hooghe T.. Is there an association between oocyte number and embryo quality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2019;39:751–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong LN, Dang VQ, Ho TM, Huynh BG, Ha DT, Pham TD, Nguyen LK, Norman RJ, Mol BW.. IVF transfer of fresh or frozen embryos in women without polycystic ovaries. N Engl J Med 2018;378:137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Nisenblat V, Lu C, Li R, Qiao J, Zhen X, Wang S.. Pretreatment with coenzyme Q10 improves ovarian response and embryo quality in low-prognosis young women with decreased ovarian reserve: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018;16:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Zhang C, Chen L, Wang Y, Li R, Liu P, Qiao J.. Cumulative live birth rate of low prognosis patients with POSEIDON stratification: a single-centre data analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2020;41:834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, Rienzi L, Sunde A, Schmidt L, Cooke ID.. et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1786–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the text and its supplementary material.