Abstract

Cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) levels are elevated in septic shock and are higher in nonsurvivors. Whether CFH is only a marker of sepsis severity or is involved in pathogenesis is unknown. This study aimed to investigate whether CFH worsens sepsis-associated injuries and to determine potential mechanisms of harm. Fifty-one, 10–12 kg purpose-bred beagles were randomized to receive Staphylococcus aureus intrapulmonary challenges or saline followed by CFH infusions (oxyhemoglobin >80%) or placebo. Animals received antibiotics and intensive care support for 96 h. CFH significantly increased mean pulmonary arterial pressures and right ventricular afterload in both septic and nonseptic animals, effects that were significantly greater in nonsurvivors. These findings are consistent with CFH-associated nitric oxide (NO) scavenging and were associated with significantly depressed cardiac function, and worsened shock, lactate levels, metabolic acidosis, and multiorgan failure. In septic animals only, CFH administration significantly increased mean alveolar-arterial oxygenation gradients, also to a significantly greater degree in nonsurvivors. CFH-associated iron levels were significantly suppressed in infected animals, suggesting that bacterial iron uptake worsened pneumonia. Notably, cytokine levels were similar in survivors and nonsurvivors and were not predictive of outcome. In the absence and presence of infection, CFH infusions resulted in pulmonary hypertension, cardiogenic shock, and multiorgan failure, likely through NO scavenging. In the presence of infection alone, CFH infusions worsened oxygen exchange and lung injury, presumably by supplying iron that promoted bacterial growth. CFH elevation, a known consequence of clinical septic shock, adversely impacts sepsis outcomes through more than one mechanism, and is a biologically plausible, nonantibiotic, noncytokine target for therapeutic intervention.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) elevations are a known consequence of clinical sepsis. Using a two-by-two factorial design and extensive physiological and biochemical evidence, we found a direct mechanism of injury related to nitric oxide scavenging leading to pulmonary hypertension increasing right heart afterload, depressed cardiac function, worsening circulatory failure, and death, as well as an indirect mechanism related to iron toxicity. These discoveries alter conventional thinking about septic shock pathogenesis and provide novel therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: cell-free hemoglobin, iron, septic shock

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a rapidly lethal disease with an in-hospital mortality rate of ∼16% (1). Over the past half-century, scores of candidate therapies that inhibit the host response have been tested. None has proved effective (2–6). Recent research has found that early in the course of clinical sepsis, cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) levels are elevated and are higher in patients who die (7, 8). Elevated CFH levels have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of other disorders including sickle cell disease, hereditary hemolytic anemias, malaria, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), eclampsia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (9–13). However, in patients with sepsis, it is unknown whether CFH elevations are only a marker of severity or are directly involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis, worsening or inducing sepsis-associated injuries, and death. In our canine Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia model, we previously reported that transfusing stored red blood cells (RBCs) increased hemolysis, releasing CFH and iron while worsening outcomes (14). In addition to CFH and iron, hemolysis also releases other potentially toxic products such as membrane lipids and proteins that could also explain increased injury (15).

Known mechanisms of CFH-related injury, include nitric oxide (NO) scavenging, which causes vasoconstriction resulting in pulmonary and systemic hypertension that may lead to endothelial damage (15–19). CFH also degrades into heme, an iron-containing molecule that can induce inflammation, oxidative stress, and cytotoxicity resulting in tissue injury (20–24). CFH-derived heme may also worsen bacterial infections by delivering iron to infecting organisms, thereby increasing bacterial growth (14, 25, 26). Infusions of commercial iron preparations in animals with bacterial infections increased mortality rates and haptoglobin concentrate administration, which binds and clears CFH, lowered iron levels, and decreased mortality (27, 28).

None of the studies in large animals have investigated whether the CFH challenge can worsen sepsis pathophysiology. We infused purified canine CFH to normal animals and animals with S. aureus pneumonia. A two-by-two factorial study design was employed to determine if the toxicity of CFH similar to known abnormalities seen during clinical sepsis exists, and if so, whether the mechanism is dependent on an interaction between CFH and the bacterial challenge or solely dependent on the properties of CFH and, therefore, occurs in both the absence and presence of infection.

METHODS

Overview

We studied 51 healthy purpose-bred beagles (age: 1.7 ± 0.4 yr, weight: 12.1 ± 2.1 kg, male, Covance and Marshall Farms). Eight animals, during a CFH dose-finding study, received a known nonlethal dose of intrapulmonary S. aureus to cause pneumonia. Then, different doses of canine CFH were given as an intravenous bolus followed by constant infusion over hours. Using this information, we then investigated in 42 animals if CFH had different effects when administered in the presence and absence of bacteria. Animals received either intrabronchial S. aureus alone, or a CFH bolus and infusion alone, both CFH and S. aureus, or neither agent. The doses of CFH and bacteria administered to each of the animals studied were identical within each of the 15, 96 h cycles. We also investigated in two animals if CFH, when administered in the absence of bacteria, had effects on cardiac right ventricular performance as measured by transthoracic echocardiography (Sonosite M-Turbo, Bothell, WA) over the 96-h study period. For description of the blood and physiological tests performed each day, see supplemental data (Supplemental Fig. S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066969).

Two-by-Two Factorial Design Study

A total of 42 animals were studied that received either intrabronchial S. aureus challenge alone (n = 11 animals), or intravenous infusion of CFH alone (n = 10 animals), or both S. aureus and CFH (n = 17 animals), or neither of them (n = 4 animals). On day 1 at 0 h, all animals received either an intrabronchial challenge of S. aureus (dose range: 0.4–0.9 CFU/kg) to induce sepsis or equivalent volume of PBS as a control. At 8-h after bacterial or saline intrapulmonary challenge, all animals received CFH bolus and infusion or an equivalent volume of PBS. Initially, the dose of CFH infused was a bolus of 8 µmol/kg and infusion at 16 µmol/h for 6 h as described in the dose-finding study. To increase mortality, the dose of bacterial inoculum was gradually increased throughout the study from a starting dose of 0.4 CFU/kg to 0.9 CFU/kg to effect severe lung injury and a mortality endpoint in animals receiving both CFH and bacteria combined. At the beginning of cycle 8 and until the end of the study, the CFH infusion duration was extended from 6 to 12 h at the same rate of 16 µmol/h, effectively doubling the dose of CFH delivered during the infusion. The infusion duration was increased to prolong the elevated plasma levels of CFH, to maximize morbidity and mortality in animals receiving CFH and bacteria combined, and thereby to provide contrast to the effects of administering CFH or bacteria alone. The study was analyzed looking for effects within cycle and at no point was the animal receiving both bacteria and CFH disadvantaged by receiving a higher dose of bacteria or CFH than other animals within the same cycle. See supplemental data (Supplemental Table S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067002.v1) for a complete cycle-by-cycle view of all animals studied in the dose-response and two-by-two factorial study portions of this manuscript.

Common Care Protocol for All Animals Studied

On day 1, all animals were anesthetized, intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Femoral arterial, central venous, urinary catheters, and a tracheostomy were inserted into each study animal as previously described (14). During the 96 h study, all animals received appropriate intensive care unit (ICU) level care with intravenous fluids, vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and sedation titrated to physiological endpoints. All animals also received ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg every 8 h starting 4-h after intrabronchial challenge and also prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin 3,000 units every 8 h, chlorhexidine oral rinses, and frequent repositioning to prevent pressure ulcers. A sedation regimen consisting of fentanyl, midazolam, dexmedetomidine, and propofol, was titrated to physiological endpoints to obtain appropriate sedation and analgesia. All animals were treated identically, except for the receipt of the two intended experimental interventions: CFH infusions and intrabronchial bacteria. Animals were continuously monitored and cared for by a clinician or trained technician throughout the experiment. After 96 h, animals that were still alive were considered survivors and euthanized. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CCM 19-01).

Hemodynamic parameters including mean arterial pressure (MAP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), pulmonary arterial occlusion pressure (PAOP), central venous pressure (CVP), heart rate (HR), and cardiac output were measured and blood sampling from the animals for arterial blood gases, complete blood counts (CBC), serum chemistries, nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI), troponin, and cytokines were measured in all animals studied at the times (Supplemental Fig. S1) as previously described (14, 28). Cytokines (TNFα, IL-6, and IL-10) were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (ProcartaPlex, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) as previously described. Troponin I was determined using a multidetection microplate reader (Synergy HT, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) and commercially available canine-specific ELISA kits (Life Diagnostics, West Chester, PA) as previously described (28).

Preparation of Cell-Free Hemoglobin

Universal donor, nonexpired, leukoreduced canine whole blood units were purchased from Animal Blood Resources International (Dixon, CA). Within 7–10 days of purchase, blood was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 15 min, then plasma and preserving solution were removed. The remaining RBCs were washed three times using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then underwent centrifugation at 4,000 g for 15 min; supernatant fractions were discarded. The resulting red blood cells were immediately used for the preparation of CFH as described previously (29–31). Red blood cells were lysed hypotonically with double-distilled water and centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. CFH concentration was determined by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy using available canine hemoglobin standard reference spectra as previously described for human CFH (29–31). The CFH concentration was then adjusted to 2 mM with PBS. The resulting solution was centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min to remove insoluble fractions. The purity of CFH and absence of methemoglobin (<5%) were confirmed spectroscopically. Samples were aliquoted into storage bags and frozen at −70°C until further use.

Preparation of Staphylococcus aureus

Frozen aliquots of a virulent S. aureus strain previously isolated from a patient with sepsis were used in these experiments. S. aureus was identified as a nontoxic shock-type pathogen (TSST-1) by the Centers for Disease Control (Atlanta, GA). S. aureus was further identified as a virulent capsular serotype 8 (32). We periodically sequenced the bacterial genome (Accugenix, AccuGENX-ID) and performed sensitivity testing (Oxoid, ceftriaxone antimicrobial susceptibility disks) and have found that the bacterium has not mutated and remains sensitive to ceftriaxone. Aliquots were thawed and inoculated in 250 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). After incubation for 19 h, suspensions were centrifuged at 1,200 g for 30 min at 4°C, washed twice in PBS, and resuspended. Bacterial concentration in this solution was determined turbidometrically. PBS was added to the bacterial suspension to produce a concentration of 0 to 2 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of S. aureus. The concentrations were confirmed by plating serial dilutions on Sheep Blood Agar and MacConkey culture medium and counting colonies as previously described. During the inoculation, animals were preoxygenated with 100% O2 for 5 min while under continuous intravenous sedation. After preoxygenation, the ventilator was disconnected from the tracheostomy and a sterile bronchoscope (Olympus BF-1T20, Lake Success, NY) was advanced to the right lower lobe segmental bronchus via the tracheostomy site. A pulmonary arterial thermodilution catheter was advanced via the suction port of the bronchoscope and wedged with the balloon inflated into a subsegmental bronchus. A predetermined suspension of S. aureus (range: 0 to 2 × 109 CFU/kg) or placebo was administered via the catheter directly into the subsegmental bronchus. Following inoculation, the catheter balloon was deflated, bronchoscope and thermodilution catheter were removed, and the animal was reattached to mechanical ventilation.

In our animal model, antibiotics were given at doses known to produce therapeutic levels to increase the clinical relevance of the model. In this setting, cultures for sensitive bacteria became uninformative and precluded meaningful quantitative blood and sputum bacterial cultures. Bronchoalveolar lavage to obtain cultures in previous studies could not be performed without adversely affecting outcome in the model itself and, therefore, had to be abandoned. A qualitative measure of increased lung parenchymal injury in this model by histopathology has previously been published (14).

Dose-Finding Study

Initially, four animals received a known nonlethal dose of intrabronchial S. aureus (0.6 × 109 CFU/kg as described in Overview) along with different doses of CFH. A serum cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) level of 100–150 µM was associated with increased NO consumption, lung injury, and pulmonary arterial pressures based on a previous publication using this model. We, therefore, targeted a steady-state level of 100 µM (14). To this end, a CFH bolus dose of 2, 5, 10, and 16 µmol/kg was administered over 20 min, immediately followed by an intravenous CFH infusion at rates of 2.4, 4.9, 19.4, and 32.4 µmol/h, for 6, 10, or 19 h. The first four animals experienced severe lung injury with a rapid 100% mortality (Supplemental Fig. S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067014.v1). Four additional animals were studied and the bolus and infusion dose and infusion time of CFH were drastically reduced and the bacterial dose was minimally reduced. The next four animals were given a bolus of 1, 2, 4, and 8 µmol/kg of CFH, immediately followed by infusion rates of 2, 4, 8, and 16 µmol/h. In all four animals, the infusion duration was reduced to 6 h. The bacterial inoculum dose was also reduced to 0.4 CFU/kg. This resulted in no mortality in all four animals and severe lung injury only in one of the four animals. Therefore, the next part of the study used a CFH bolus of 8 µmol/kg followed by an infusion at a rate 16 µmol/h for 6 h, as this was the dose of CFH found to cause lung injury with minimal mortality.

Measurement of CFH levels, percentage oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin, and nontransferrin bound iron.

Canine levels of CFH (μmol/L) and oxidation/oxygenation state were determined using UV-vis spectrophotometry. After sedimentation of red blood cells, the supernatant was scanned using a Cary 100 (Varian) spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere detector used to capture scattered light so that turbidity contributions to the spectra are minimized. The spectra were deconvoluted using a least-squares fit-to-basis spectra for oxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin normalized by their known extinction coefficients. Fitting results provided concentrations of each species and the total values. Canine nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI) plasma levels were determined by a commercial laboratory (Aferrix Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel) using a proprietary assay.

Statistical Analysis

Survival times were plotted using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and analyzed using stratified log-rank tests. For all other variables, changes from baseline values were analyzed in linear mixed models to account for the correlation of animals studied in each cycle and the repeated measures within each animal. To evaluate shock reversal, we standardized MAP and norepinephrine using Z-scores and then calculated a shock score based on the difference between the MAP Z-score and norepinephrine Z-score. We first tested the group-time interaction. If the interaction term is significant, groups are compared at each time point; otherwise, group comparisons are based on the main effects. Standard residual diagnostics were used to check model assumptions. All P values are two-sided and considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. For some variables, logarithm transformation was used when necessary. SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses in this study. Echocardiography data were analyzed using linear mixed models to estimate the mean change from baseline levels, accounting for repeated measures of each animal. Randomization was performed by the statistician using a random number generator to randomize up to four animals in each weekly experiment.

RESULTS

Injurious Effects of CFH are More Profound in the Presence than in the Absence of Infection

Mortality.

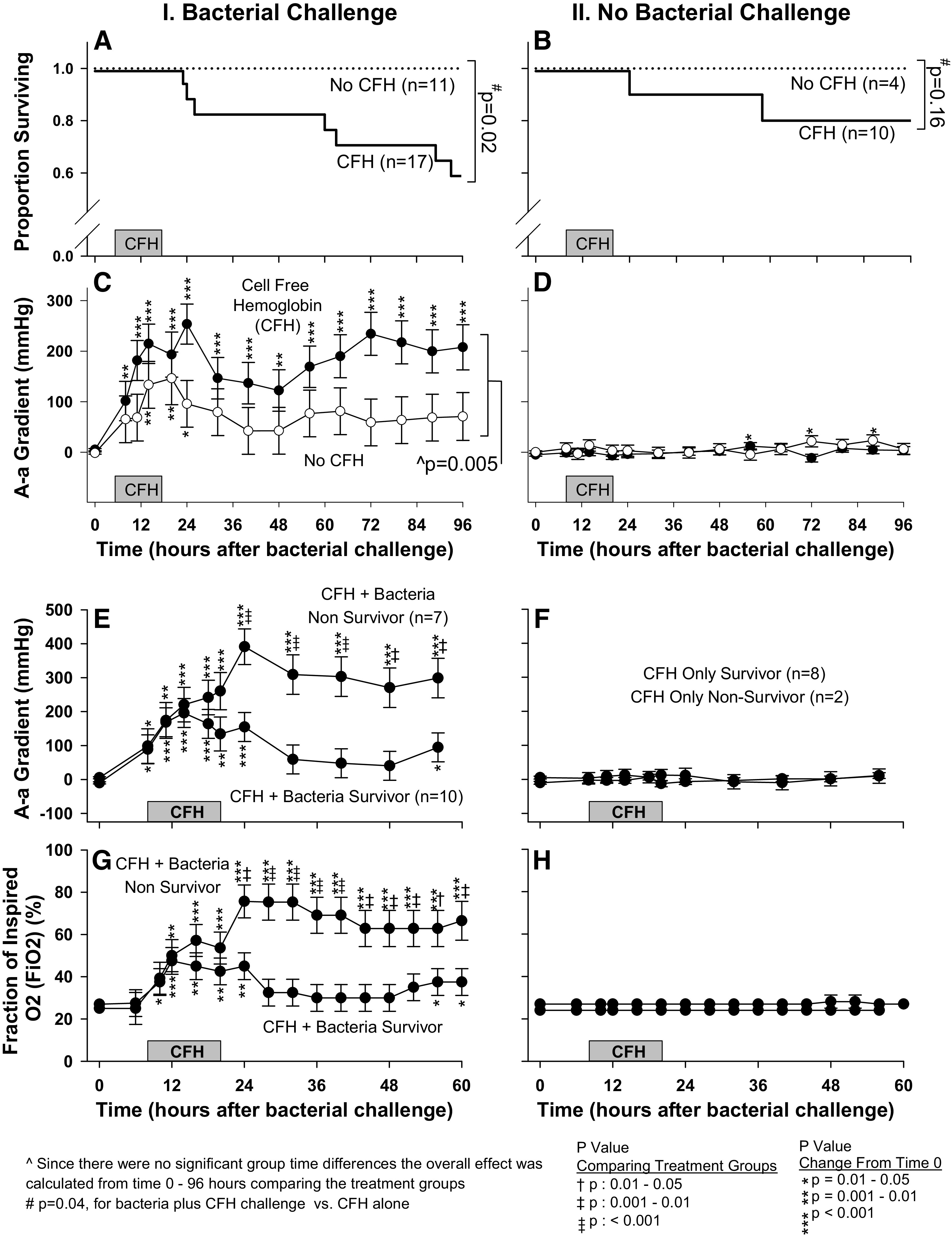

In animals challenged with bacteria, those randomized to receive CFH (n = 17) had a significantly increased mortality rate compared with animals randomized to receive bacteria alone (n = 11, 41% vs. 0%, P = 0.02, stratified log-rank test) (Fig. 1A). In animals not challenged with bacteria, those randomized to receive CFH (n = 10) had a nominally higher mortality rate compared with animals that received neither bacteria nor CFH, (n = 4, 20% vs. 0%, P = 0.16, stratified log-rank test) (Fig. 1B). CFH infusion, when added to a nonlethal bacterial challenge, was associated with significantly increased mortality rate compared with CFH alone (41% vs. 20%, P = 0.04, stratified log-rank test) (Fig. 1, A and B, respectively).

Figure 1.

Effects of CFH on survival and pulmonary injury in both septic and normal (nonseptic) animals. A: survival in septic animals receiving CFH (solid line) is compared with septic controls not receiving CFH (dotted line). B: survival in nonseptic animals receiving CFH (solid line) is compared with nonseptic control animals not receiving CFH (dotted line). C: serial mean (± SE) AaO2 in septic animals that received CFH (filled circles) is compared with septic controls not receiving CFH (open circles). D: serial mean (± SE) AaO2 in nonseptic animals that received CFH (filled circles) is compared with nonseptic control animals not receiving CFH (open circles). E: serial mean (± SE) AaO2 is compared in survivors vs. nonsurvivors for animals receiving both bacteria and CFH. F: the format is similar to (E) except that animals represented here received CFH alone. G: serial mean (± SE) is compared in survivors vs. nonsurvivors for animals receiving both bacteria and CFH. H: the format is similar to (G) except that animals represented here received CFH alone. On the x-axis, CFH represents duration of CFH infusion in animals receiving CFH and duration of placebo infusion in animals receiving placebo. AaO2, alveolar-arterial gradient; CFH, cell-free hemoglobin; , fraction of inspired oxygen.

Alveolar-arterial gradient.

In animals challenged with bacteria, those randomized to receive CFH had a statistically significant elevation from baseline (0 h) in mean alveolar-arterial gradient (AaO2) at all 14 time points measured from 8 to 96 h after bacterial challenge (Fig. 1C). In animals receiving bacterial challenge alone, the mean AaO2 was significantly elevated above baseline at only 3 of 14 time points measured (14, 20, and 24 h). Accordingly, the increase in mean AaO2 from baseline was significantly greater on average from 8 to 96 h in animals receiving bacteria and CFH compared with those receiving bacteria alone (P = 0.005). In contrast, when comparing animals that received CFH alone (n = 10) with animals that received neither CFH nor bacteria (n = 4), the mean AaO2 changes from baseline throughout the study were minimal and showed no significant group differences (all, P > 0.05, Fig. 1D).

Pulmonary injury and respiratory support in nonsurvivors versus survivors.

In animals challenged with both bacteria and CFH, nonsurvivors had significantly greater increases from baseline in mean AaO2 compared with survivors from 24 to 60 h (Fig. 1E). As expected, since CFH had minimal or no effect on lung injury in the absence of infection, there were no significant differences in mean AaO2 between survivors and nonsurvivors in animals receiving CFH alone (Fig. 1F). In animals receiving both bacteria and CFH, nonsurvivors compared with survivors required a significantly higher mean fraction of inspired oxygen () from 24 to 60 h (Fig. 1G), and significantly higher mean positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) at 24, 48–56 h (Supplemental Fig. S3A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066996.v1), as well as significantly higher mean respiratory rates (RR) from 16 to 60 h (Supplemental Fig. S3B). There were no significant differences between survivors versus nonsurvivors in animals receiving CFH alone in mean (Fig. 1H), PEEP (Supplemental Fig. S3C), and RR (Supplemental Fig. S3D; all, P > 0.05). These findings indicate that CFH increased lung injury during bacterial infection, which affected mortality.

Injurious Effects of CFH Similar in the Presence and Absence of Infection

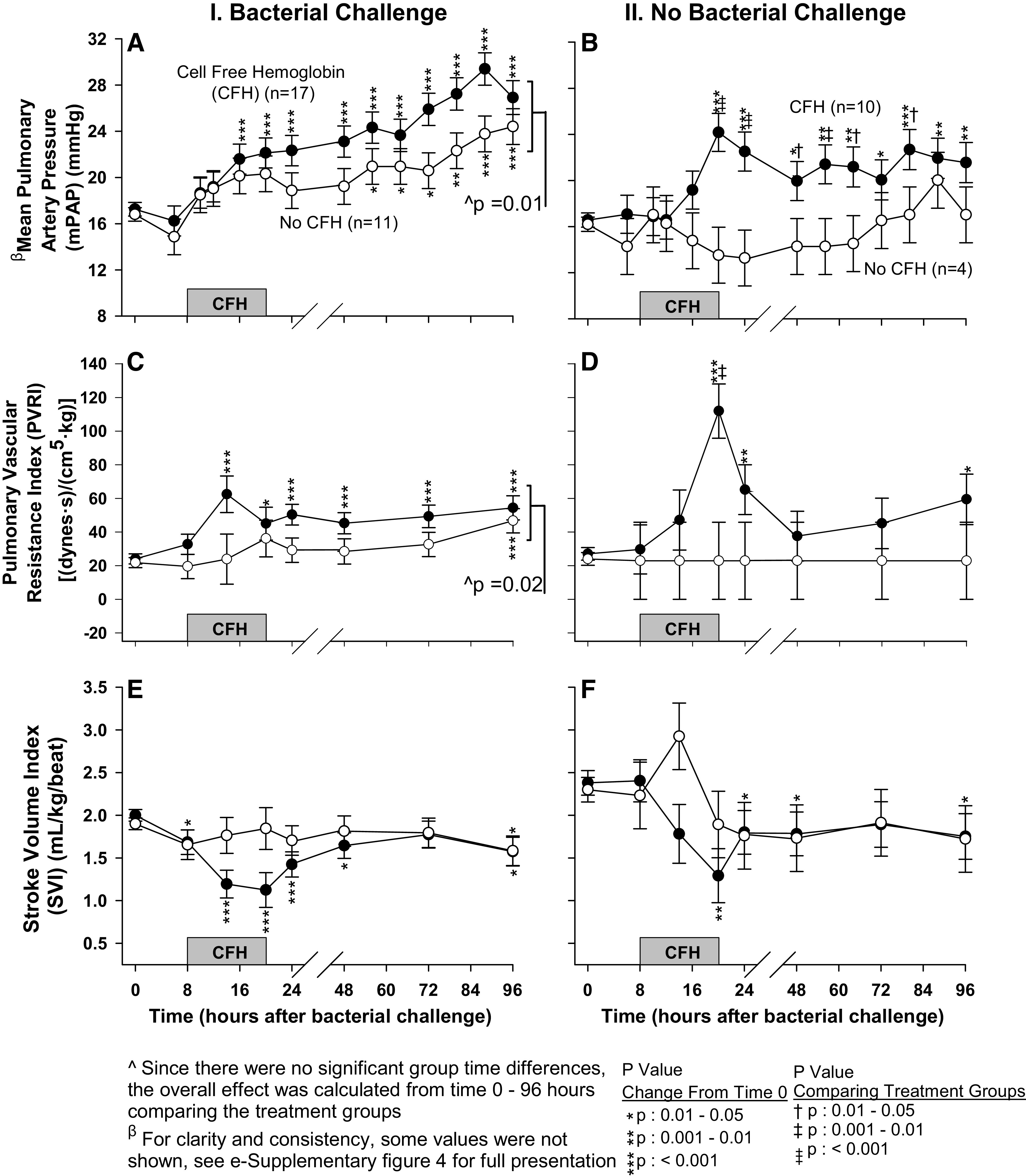

mPAP and PVRI.

In animals challenged with bacteria and CFH, the mean mPAP was significantly elevated from baseline at 10 of 13 time points (16–96 h) (Fig. 2A, for a full presentation of mean mPAP see Supplemental Fig. S4; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067005.v1). In animals receiving bacteria alone, mean mPAP was significantly elevated from baseline at only 6 of 13 time points (56–96 h). Averaged over all the time points measured, mPAP was greater (P = 0.01) in animals that received CFH and bacteria compared with bacteria alone.

Figure 2.

The format is similar to Fig. 1 (C and D), except now serial mean (± SE) pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) (A and B), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) (C and D), and stroke volume index (SVI) (E and F) are shown.

The mean mPAP in animals receiving CFH without bacteria had significant elevations from baseline at all time points measured from 20 to 96 h, whereas animals receiving neither challenge had no significant changes in mean mPAP from baseline (Fig. 2B). There were significantly greater increases from baseline in mean mPAP at 20–64, 80 h in animals receiving CFH without bacteria versus those receiving neither CFH nor bacteria. These patterns of significant changes in both animals challenged with and without bacteria were similarly observed for the mean pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) (Fig. 2, C and D, respectively).

Stroke volume index.

Since increased pulmonary pressures can depress cardiac performance by increasing right ventricular afterload, we investigated whether stroke volume index was depressed in the setting of the pulmonary hypertensive effects of CFH. In animals receiving bacterial challenge, those randomized to CFH had significant decreases in stroke volume index (SVI) from baseline at 6 of 7 time points (8–48, 96 h), whereas those receiving bacteria alone had significant decreases from baseline at only 1 of 7 time points (up to 96 h) (Fig. 2E). In animals that did not receive bacteria, those randomized to CFH alone, had significant decreases from baseline in mean SVI at 4 of 7 time points (20–48, 96 h), whereas there were no significant changes from baseline in mean SVI in animals receiving neither bacteria nor CFH (Fig. 2F). In animals receiving CFH (with bacteria and without), this depression of SVI and increased pulmonary pressures was most pronounced during infusion (Fig. 2, E and F, respectively). We next investigated how the CFH effect on raising pulmonary pressures and reducing SVI impacted other measures of cardiac performance [heart rate (HR) and cardiac index (CI)] along with right ventricular function as measured by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC).

HR and CI.

Both groups receiving CFH (with and without bacteria), experienced significant increases in mean HR from baseline associated with decreases in mean SVI (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B, respectively; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067008.v1). Increases in mean HR were significantly greater in animals receiving both CFH with bacteria and CFH alone compared with animals receiving bacteria alone at 24 h and those receiving neither CFH nor bacteria at 48 h (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B, respectively). This increase in mean HR overall in animals receiving CFH appeared to compensate for the decrease in mean SVI as CI was relatively unchanged throughout the study, with the exception of some early time points (Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). Animals receiving bacteria alone had significant increases in mean CI from baseline at 8–14 h (Supplemental Fig. S5C). However, when CFH was added to bacteria, this increase in mean CI was significantly suppressed. Mean CI was depressed from baseline by 14 h, such that animals receiving CFH with bacteria had a depressed mean CI compared with animals receiving bacteria alone P < 0.001 (Supplemental Fig. S5C).

To further investigate effects on cardiac performance, two normal animals were infused with CFH (oxyhemoglobin) alone in doses comparable with infected animals. Both animals had significant right ventricular dysfunction compared with baseline (0 h) as evidenced by reduced right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC, P = 0.003, Supplemental Fig. S6A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066972.v1) and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE, P = 0.004, Supplemental Fig. S6B) throughout the 96 h study by cardiac echocardiography. Decreases in right ventricular function in these two animals were associated with significantly increased pulmonary pressures (Supplemental Fig. S6C).

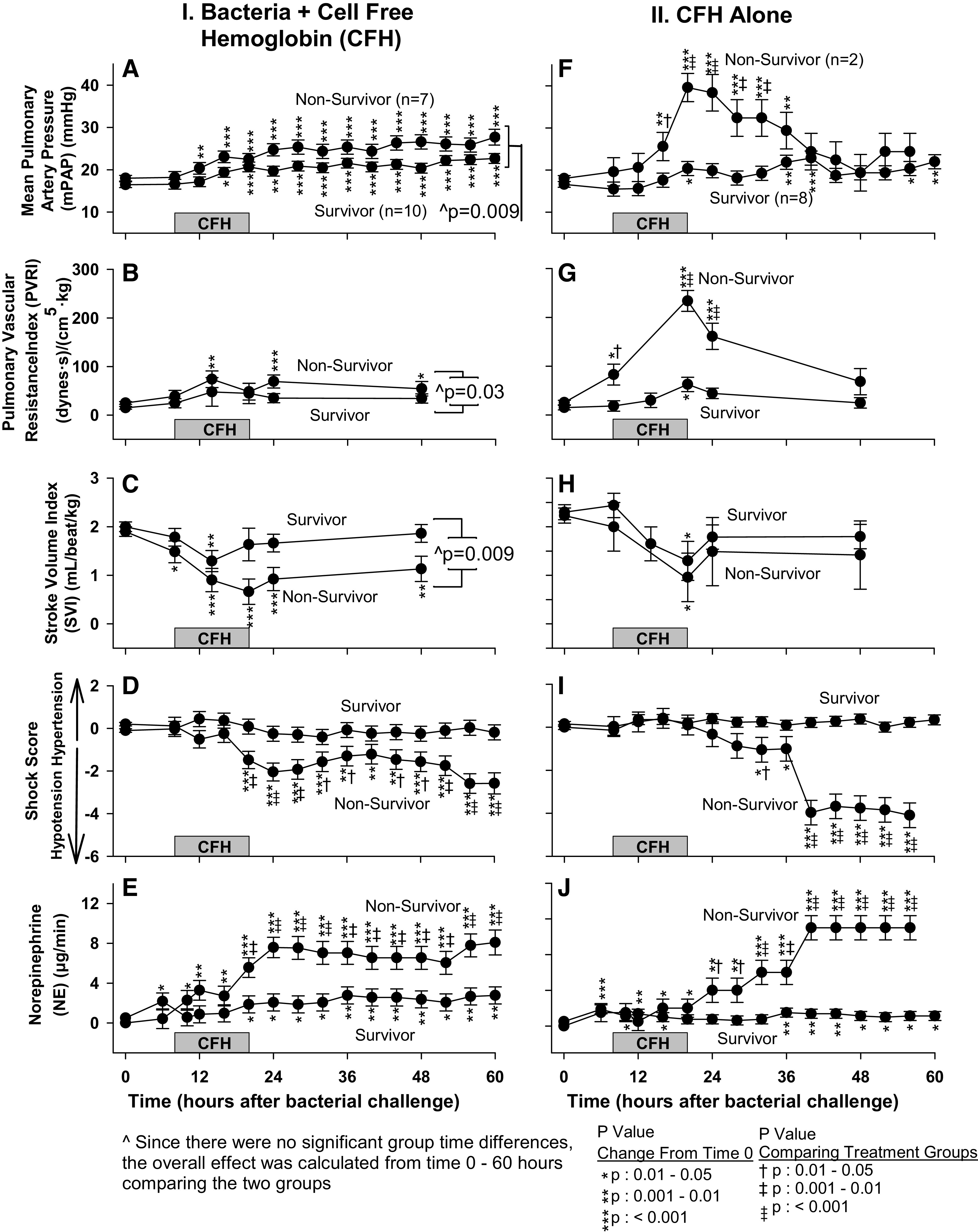

mPAP, PVRI, SVI, Shock Score, and Norepinephrine Doses in Nonsurvivors versus Survivors

In animals challenged with both bacteria and CFH, mean increases from baseline in mPAP when averaged from 8 to 60 h were greater (P = 0.009) in nonsurvivors compared with survivors (Fig. 3A). Similarly, in this group, the mean increases from baseline in PVRI, when averaged from 8 to 60 h, were also overall higher (P = 0.03) in nonsurvivors (Fig. 3B). Nonsurvivors that received CFH with bacteria had on average from 8 to 48 h significantly greater decreases from baseline in mean SVI (P = 0.009, Fig. 3C). In animals receiving CFH with bacteria, nonsurvivors experienced more severe shock and required higher mean norepinephrine levels from 20 to 60 h to return mean arterial pressure (MAP) to near normal levels (Fig. 3, D and E).

Figure 3.

For the panels on the left, the format is similar to Fig. 1 (E), except now serial mean (± SE) mPAP (A), PVRI (B), SVI (C), shock score (D), and norepinephrine levels (E) are shown. For the panels on the right, the format is similar to Fig. 1 (F), except now serial mean (± SE) mPAP (F), PVRI (G), SVI (H), shock score (I), and norepinephrine levels (J) are shown. mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SVI, stroke volume index.

In animals receiving CFH without bacteria, nonsurvivors compared with survivors had significantly greater increases from baseline in mean mPAP at 16–32 h and in mean PVRI from 8 to 24 h (Fig. 3, F and G). In animals that received CFH alone, nonsurvivors had nominally greater decreases in mean SVI from baseline during this same time that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3H). We next examined if this depression of cardiac performance was associated with worse shock in nonsurvivors. In animals receiving CFH alone, nonsurvivors at 32, 40–56 h also had significantly worse shock (lower mean shock scores) and higher mean norepinephrine levels from 24 to 56 h required to normalize mean MAP (Fig. 3, I and J).

These data indicate that nonsurviving animals receiving CFH, regardless of whether they were infected or not, sustained more profound increases in pulmonary arterial pressures and cardiac dysfunction associated with hemodynamic compromise and worse shock. Death with CFH and bacteria was associated with an indirect mechanism of injury worsening lung oxygenation and also a direct mechanism of injury consisting of hemodynamic abnormalities associated with elevated pulmonary vascular pressures and compromised cardiac function both in the presence and absence of infection. We next evaluated CFH decreased cardiac filling pressures as a possible explanation for this cardiac dysfunction and worsened shock.

Central venous pressure and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure.

There were no major abnormalities in cardiac filling pressures as measured by central venous pressure (CVP) and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) in these four treatments groups that could explain the worse outcomes with CFH; mean cardiac filling pressures were in a normal range but higher with CFH treatment with and without bacterial challenge (Supplemental Fig. S7, A and B; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066978.v1 and Supplemental Fig. S8, A and B; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066990.v1). Given the direct harmful effects of CFH on the pulmonary vasculature and cardiac function with and without infection, we next evaluated other possible direct injuries associated with CFH.

Other Injurious Effects of CFH Similar in the Presence and Absence of Infection

Renal, hepatic, muscle, hematological, and metabolic abnormalities.

Animals challenged with bacteria and CFH demonstrated significantly greater increases from baseline in mean creatinine (Cr) at 10, 14–48, and 96 h and mean blood urea nitrogen (BUN) from 14 to 48 h compared with animals receiving bacteria alone (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Fig. S9A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066993.v1, respectively). Animals challenged with CFH without bacteria had significantly greater increases from baseline in mean Cr from 16 to 48 h and mean BUN from 20 to 24; however, there were no significant increases from baseline in mean Cr and BUN in animals receiving neither challenge throughout (Fig. 4B, Supplemental Fig. S9B). There were also no significant increases from baseline in any of the groups studied in the mean BUN:CR ratio that might explain these results by volume shifts (Supplemental Fig. S9, C and D). These findings are most consistent with direct renal toxicity due to CFH.

Figure 4.

The format is similar to Fig. 1 (C and D), except now serial mean (± SE) serum creatinine in logarithmic scale (A and B), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in logarithmic scale (C and D), creatine phosphokinase (CPK) (E and F), white blood cell (WBC) count (G and H), lactate in logarithmic scale (I and J), and pH (K and L) are shown.

Animals challenged with CFH and bacteria had significant elevations from baseline in mean alanine aminotransferase (ALT) from 8 to 24 h, whereas animals challenged with bacteria alone had no significant changes from baseline in mean ALT throughout (Fig. 4C). In animals receiving CFH alone without bacteria, mean ALT was significantly elevated from baseline at 12–14, 18–24 h, whereas animals receiving neither challenge had no significant elevations from baseline in mean ALT (Fig. 4D). In animals receiving CFH with bacteria from 12 to 96 h and without bacteria from 18 to 48 h, there were significantly greater increases from baseline in mean creatine phosphokinase (CPK) compared with animals that received, respectively, bacteria alone or neither challenges (Fig. 4, E and F, respectively). In normal animals, CFH caused no significant elevations in troponin levels (all, P > 0.05, Supplemental Fig. S10, A and B; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066981.v1). These findings suggest a direct hepatic and skeletal muscle injury due to CFH.

Animals challenged with CFH and bacteria compared with animals challenged with bacteria alone had significantly less increase from baseline in mean white blood cell (WBC) count from 11 to 20 h (Fig. 4G). Similarly, animals receiving CFH without bacteria compared with animals receiving neither CFH nor bacteria had significantly less increase from baseline in mean WBC count from 11 to 20 h (Fig. 4H). This pattern of changes in WBCs was similar for the mean neutrophil count (Supplemental Fig. S11, A and B, respectively; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066984.v1). In animals challenged with CFH and bacteria, mean platelet count significantly decreased from 227 (± 13) to 80 (± 23) cells/µL from 0 h (baseline) to 96 h, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S11C). In animals challenged with bacteria alone, mean platelet count significantly decreased from 227 (± 13) to 125 (± 25) from 0 h to 96 h, respectively. The mean decreases in platelet count from 0 h (baseline) to 96 h were significantly greater in septic animals that received CFH (P = 0.02). In animals receiving CFH alone, the mean platelet counts significantly decreased from 232 (± 19) to 75 (± 28) cells/µL from 0 h (baseline) to 96 h, respectively. In animals receiving neither CFH nor bacteria, the mean platelet count had no significant changes from baseline 232 (± 19) cells/µL throughout the study (all, P > 0.05). The mean decreases in platelet count from 0 h (baseline) to 96 h were significantly greater in nonseptic animals that received CFH (Supplemental Fig. S11D). There were no significant abnormities or differences in the hemoglobin levels throughout in any of the four treatment groups (Supplemental Fig. S11, E and F).

Animals receiving CFH with and without bacteria had on average over the 96 h experiment, significantly greater increases in mean lactate levels from baseline compared with animals receiving bacteria alone (Fig. 4I) or neither CFH nor bacteria, respectively (Fig. 4J). Similarly, there were greater decreases in mean bicarbonate from baseline in those animals receiving CFH in the presence and absence of bacteria versus those animals receiving only bacteria or neither CFH nor bacteria respectively (Supplemental Fig. S12, A and B, respectively; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066999.v1). Accordingly, animals receiving CFH with bacteria had a significantly greater decrease from baseline in mean pH at 24, 40, 48, 80, and 88 h compared with animals receiving bacteria alone (Fig. 4K). Animals receiving CFH without bacteria also experienced significant decreases from baseline in mean pH from 14 to 64 h, whereas animals receiving neither CFH nor bacteria had no significant decreases from baseline in mean pH (Fig. 4L). There were no significant differences in mean PaCO2 throughout that could explain this metabolic acidosis (Supplemental Fig. S12, C and D). Thus, CFH in the presence and absence of infection causes a metabolic acidosis associated with more elevated lactate levels.

Bilirubin, Sodium, Chloride, Calcium, Glucose, Inorganic Phosphorous, Alkaline Phosphatase, Total Cholesterol, Total Protein, Potassium, and Albumin

Animals receiving CFH with bacteria from 8 to 24 h and CFH alone from 8 to 48 h, as expected, had significantly greater increases from baseline in mean total bilirubin, a degradation product of CFH, compared with animals receiving bacteria alone and neither challenge, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S13, A and B, respectively; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067011.v1).

Other analytes, sodium, chloride, calcium, glucose, inorganic phosphorous, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total cholesterol, total protein, potassium, and albumin had no marked abnormalities throughout the study and the occasional significant differences comparing treatments groups did not easily explain the marked pulmonary vascular and cardiac dysfunction seen with CFH infusions (For laboratory values, see Supplemental Table S2; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066987.v1).

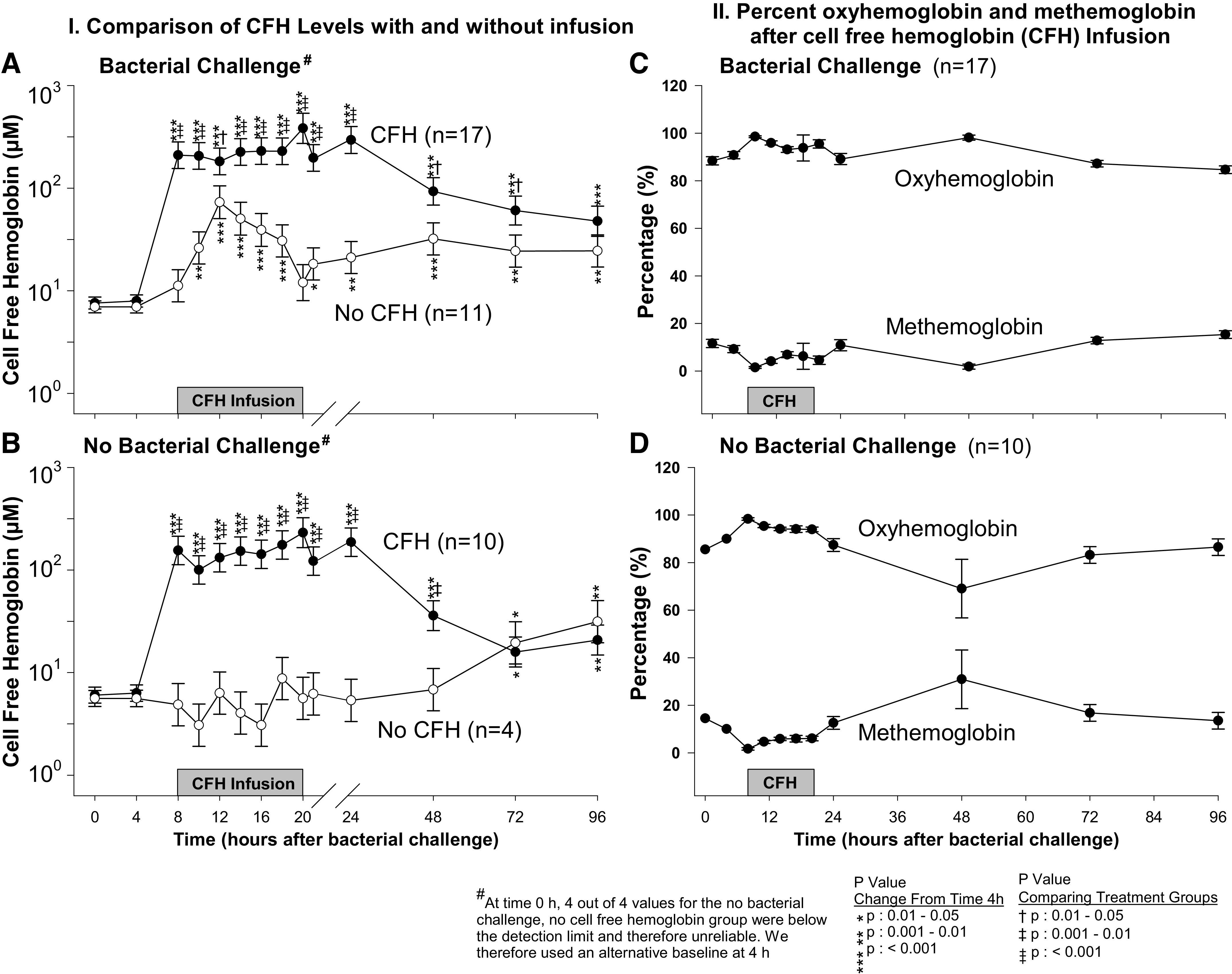

CFH Levels and Percent Oxyhemoglobin versus Methemoglobin

Animals receiving CFH with bacterial challenge from 8 to 96 h had significant increases from baseline (4 h) in mean log plasma CFH levels (Fig. 5A). Animals receiving bacteria alone also had significant elevations from baseline in mean log plasma CFH levels from 10 to18 and 21 to 96 h, but were significantly lower than animals receiving CFH with bacteria from 8 to72 h (Fig. 5A). Animals receiving CFH without bacterial challenge from 8 to 96 h had significant increases from baseline (4 h) in mean log plasma CFH levels (Fig. 5B). Animals receiving neither CFH nor bacteria had significant elevations from baseline in log mean CFH levels only at late isolated time points (72 and 96 h) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

The format is similar to Fig. 1 (C and D), except now serial mean (± SE) cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) levels in logarithmic scale (A and B) are shown. C and D: the serial mean percent (± SE) oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin levels are shown in animals receiving CFH with bacteria (C) and CFH without bacteria (D).

Using spectral deconvolution, we found that during CFH infusion (8–20 h) with and without bacterial challenge, the majority of CFH infused was in the form of oxyhemoglobin, > 90% (Fig. 5, C and D, respectively). In the period following CFH infusion (20–96 h), in the presence of bacterial infection ∼90% of CFH remained as oxyhemoglobin (Fig. 5C), whereas in the absence of infection, ∼80% of CFH remained as oxyhemoglobin (Fig. 5D), indicating that there may have been more in vivo conversion to methemoglobin in the absence of infection. These data indicate that in animals given CFH, a steady state of between 150 and 200 µM of oxyhemoglobin was reached during infusion with slow lowering of levels over 96 h with minimal conversion to methemoglobin. We next measured NTBI levels after CFH infusions in the presence and absence of infection.

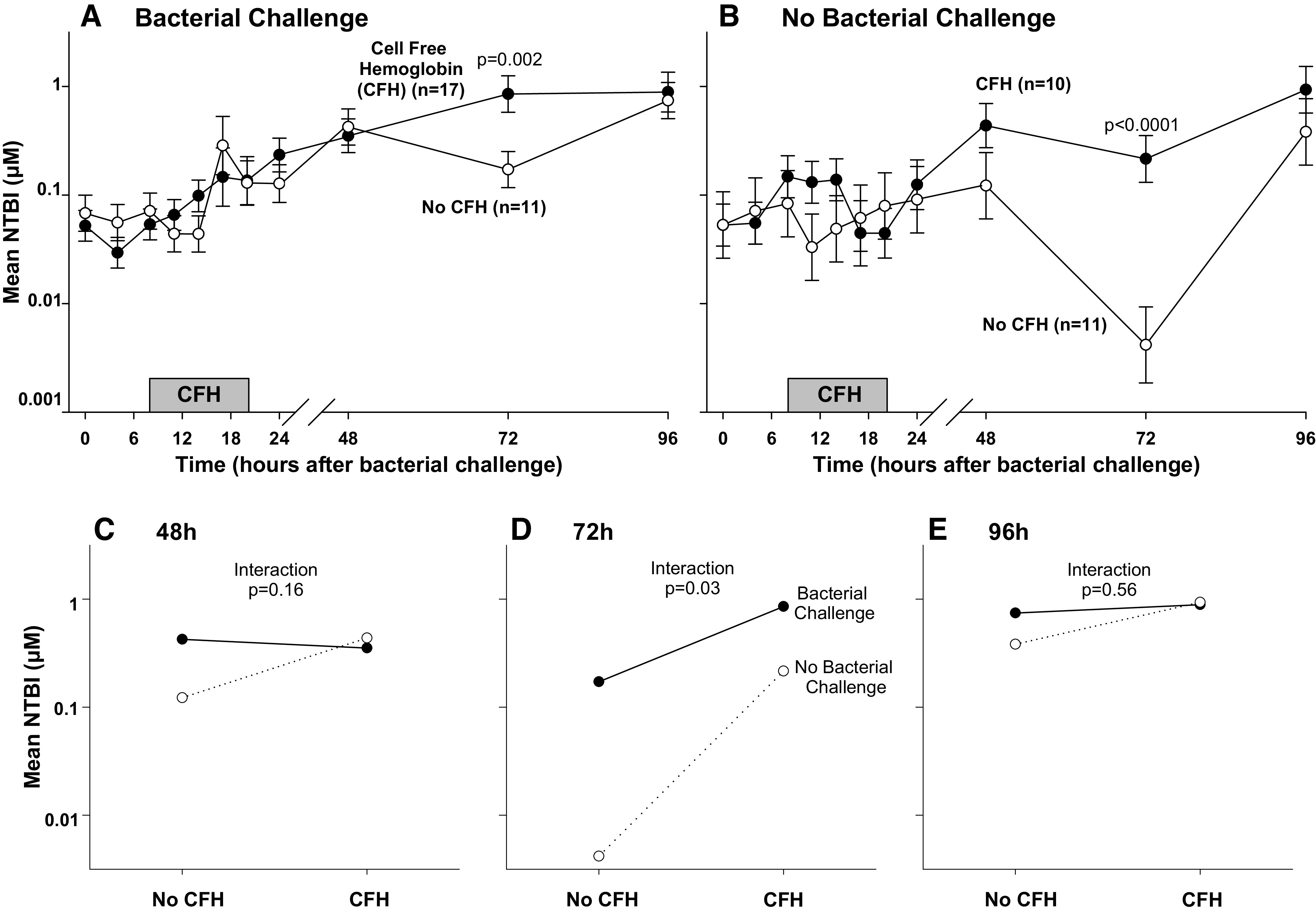

Nontransferrin Bound Iron

CFH was infused from 4 to 20 h. Iron in this form is bound to heme and not quantified by NTBI measurements. Hemoglobin-bound iron requires metabolism and degradation to release iron from heme to become measurable by NTBI (33). Thus, during early infusion (0 to 24 h), there were no significant differences in mean NTBI levels in septic animals regardless of whether or not they received CFH (all, P > 0.05, Fig. 6A). This pattern was also found from 0 h to 24 h in nonseptic animals regardless of whether they received CFH (all P > 0.05, Fig. 6B). In contrast, by 72 h, mean NTBI levels in septic animals receiving CFH with bacteria were significantly higher compared with septic animals receiving bacteria alone (P = 0.002, Fig. 6A). Likewise, at 72 h, nonseptic animals receiving CFH without bacteria also had a significantly higher mean NTBI level compared with nonseptic animals receiving neither CFH nor bacteria (P < 0.0001, Fig. 6B). The increases in mean NTBI levels seen at 72 h with CFH infusions were significantly depressed in the presence of bacteria compared with the absence of bacteria (Fig. 6D, P = 0.03, quantitative interaction). The same pattern seen at 72 h, where mean NTBI level increase was less in the presence of bacteria compared with its absence, was also nominally present at 48 h (Fig. 6C), and 96 h (Fig. 6E). These findings indicate that the ability of CFH to raise mean NTBI levels after the infusion has been completed and is depressed by the presence of bacterial infection.

Figure 6.

The format on the top is similar to Fig. 1 (C and D), except now mean (± SE) nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI) levels in logarithmic scale (A and B) are shown. In the lower panels, interaction figures are shown demonstrating the differential effect of cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) on mean NTBI levels in the presence or absence of bacterial challenge at 48 h (C), 72 h (D), and 96 h (E). Please note that in the absence of bacteria (dotted line) at 48, 72, and 96 h, NTBI levels rise with the addition of CFH. However, in the setting of bacterial infection (solid line) at these same time points, these rises are attenuated.

Interleukin-6, Interleukin-10, and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

Septic animals whether challenged with CFH or not had significant increases in mean log10 IL-6 levels at 14 h and 24 h compared with baseline (Supplemental Fig. S14A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066975.v1). However, there were no significant group differences in mean log10 IL-6 levels comparing septic animals that received CFH or not.

Nonseptic animals challenged with CFH had significant increases in mean log10 IL-6 levels at 14 h and 24 h compared with baseline (Supplemental Fig. S14B). In contrast, nonseptic animals not receiving CFH had no significant changes from baseline in mean log10 IL-6 levels throughout the experiment (all, P > 0.05). Accordingly, from 14 to 24 h, nonseptic animals receiving CFH alone had significantly greater increases from baseline in IL-6 levels compared with nonseptic animals receiving neither challenge (P < 0.0001, Supplemental Fig. S14B).

Notably, the CFH challenge in nonseptic animals resulted in a significantly greater increase in mean log10 IL-6 levels compared with the increase in mean log10 IL-6 levels in septic animals challenged with CFH at 14 h (P = 0.02 for interaction, Supplemental Fig. S14C). This same comparison at 24 h reached a P value of 0.08 for the same interaction (Supplemental Fig. S14D). Mean log10 IL-10 and log10 TNF-α levels followed a similar pattern (Supplemental Fig. S14, E– L). Thus, CFH can significantly increase cytokine levels in the absence and presence of bacterial infection. However, in the presence of bacteria, the addition of CFH results in a smaller increase in IL-6 levels than in the absence. There were no significant differences in IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels between survivors and nonsurvivors in both groups analyzed with deaths occurring (all, P > 0.05, Supplemental Fig. S15; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066966.v1).

DISCUSSION

This study employed a two-by-two factorial design to investigate whether CFH is involved in the pathogenesis of septic shock or is just a marker of disease severity. This design was specifically employed to determine if any observed injuries from CFH interacted with infection or were attributable directly to the properties of CFH and occurred similarly in the absence and presence of infection. Some injuries from CFH were dependent solely on the properties of the molecule itself. CFH administration significantly increased pulmonary pressures (mPAP and PVRI) in normal and septic animals alike, resulting in increased right ventricular afterload, which was associated with significantly depressed cardiac function, worsening shock, and death. In groups receiving CFH, the nonsurvivors had significantly greater increases in pulmonary pressures and vasopressor requirements. The ability of CFH to scavenge NO results in such direct toxicity from vasoconstriction may contribute to endothelial injury. In addition, renal, hepatic, and metabolic injuries were also present in the form of a direct injury occurring both in the absence and presence of infection.

A second, distinct indirect pattern of injury from CFH was also evident and was dependent on the presence of infection. Lung parenchymal injury, as measured by the ability of the lung to transfer oxygen [AaO2, a clinically relevant direct measurement of lung function (34)] had this form of injury. The AaO2 worsened when CFH was administered in the presence of pneumonia and was associated with significantly increased mortality rates; however, the AaO2 was in the normal range and unchanged throughout the study in the absence of infection. Among infected animals receiving CFH, nonsurviving animals had even worse pulmonary oxygenation and greater mechanical ventilation requirements. Importantly, elevations in iron levels associated with CFH were suppressed in the presence of infection but not in its absence.

Our findings do not directly prove that the known properties of CFH to scavenge NO and donate iron are the mechanisms that worsen organ injury during sepsis. This would require directly inhibiting these effects and showing that CFH thereby loses its harmful effects in sepsis. However, in this study, two distinct patterns of injury were augmented in the presence of CFH challenge. One, lung parenchymal injury, as measured by increases in the AaO2 gradient, occurred only in the presence of infection. The other, increased shock and multiorgan failure, occurred both in the presence and absence of infection. CFH is known to be a source of iron that can promote bacterial growth (35, 36). This mechanism, iron-induced bacterial growth and worsening of pneumonia and lung injury would only occur if the infection was present. This was consistent with our findings. The second pattern of injury we found can be explained by the known ability of CFH to scavenge NO with resulting vasoconstriction. NO scavenging is not dependent on the presence of infection and as expected, increases pulmonary vascular pressures in the presence and absence of infection. Although it is not possible to totally exclude other known or unknown mechanisms, these well-established mechanisms associated with CFH can fully explain both the physiology and pattern of sepsis-associated injuries seen in this study.

A sustained drop in platelet counts and a transient fall in WBC counts were notably observed with CFH infusions. Previously published mechanisms could potentially explain these findings. CFH scavenges NO and provokes adenosine diphosphate (ADP) release, which induces platelet aggregation, and which lowers circulating counts (37, 38). In addition, neutrophils can become activated and undergo apoptosis when they engulf activated platelets, possibly explaining the drop in both WBC and platelet counts (39). However, we have no direct evidence that these mechanisms are occurring in our model and the decline in platelet counts seen with CFH administration might be due to several other mechanisms including platelet activation, suppression, aggregation, or sequestration. Nonetheless, the effect of CFH on platelet and neutrophil counts was observed in both the presence and absence of infection; however, no lung injury was seen in the absence of infection.

The early decrease in mean neutrophil counts in septic animals was greater with CFH infusion, an occurrence that might be associated with a greater lung injury seen after CFH challenge only in animals with sepsis. Evidence against this interpretation is that leukopenia was transient over only the first 24 h. Failure to expand neutrophil counts above 7.2 × 103 cells/µL without absolute neutropenia has been associated with a poor outcome in clinical sepsis (40). However, neutrophil counts, in the presence of CFH, fell from ∼7 to 2 × 103 cells/µL and were low normal in all animals studied. To our knowledge, there is no clinical or laboratory evidence which indicates that a change in neutrophil counts within this range affects outcomes in infection; furthermore, slight decreases in neutrophil count should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, increased activation of pathways associated with inflammation could potentially explain the significant increases in mortality rates observed with CFH infusions after nonlethal bacterial challenge. If this were the case, the cytokine levels might be expected to markedly increase in an additive, or potentially synergistic fashion, compared with each challenge given individually and likewise, cytokine levels might be expected to be higher in nonsurvivors than survivors. Noteworthy, the two challenges combined did markedly increase some parameters such as AaO2 and pulmonary vascular resistance index in an additive fashion and these parameters were increased even more in nonsurvivors. In contrast, the cytokine levels measured (TNF, IL6, IL8) throughout the experiment were not associated with death and were remarkably similar between nonsurvivors and survivors. Furthermore, IL-6 levels (pg/mL), in the setting of these two challenges combined, were significantly less than additive compared with when the two challenges were given alone at the same time points (Supplemental Table S3; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14454219.v1). These findings do not support the notion that cytokine elevations associated with exposure to CFH during infection are responsible for the profoundly increased mortality rates; rather, other factors such as changes in iron levels, AaO2, and pulmonary vascular resistance, all associated with death, when the two challenges are combined appear to better account for these findings.

CFH elevations in clinical sepsis are not completely understood. In our model of bacterial pneumonia, the S. aureus used for the pulmonary challenge is known to produce hemolysins, which disrupt RBCs and release CFH (41). CFH is a source of iron, an essential nutrient for bacterial growth. Iron is tightly regulated in the plasma and normally rapidly bound to transferrin and transported intracellularly to be sequestered by ferritin. Bacteria have developed multiple mechanisms to liberate and use iron in the plasma and “steal” iron from transferrin (41). The importance of CFH as a source of iron in bacterial infection is supported by our previous transfusion studies employing various canine models as discussed below (14, 27, 28, 42–44).

In a previously performed set of six studies using three different animal models (bacterial pneumonia, hemorrhagic shock, and normal animals), we transfused longer (42-day) versus shorter (7-day) stored red blood cells (RBCs) to raise CFH levels (14) or gave iron challenges. The effects of these transfusion-related elevations of CFH and iron levels further support the iron hypothesis to explain why lung injury occurred with CFH challenge only in the presence but not the absence of infection. To summarize these studies: 1) in antibiotic-treated canine pneumonia, transfusion-related increases in CFH and iron levels were associated with worsening parenchymal lung injury and mortality (14); 2) in the setting of elevated CFH levels due to transfusion, increases in bacterial challenge dose were associated with progressively greater lowering of iron levels along with more profound increases in the severity of septic shock (44); 3) in two models of hemorrhagic shock and in normal animals, high CFH and iron levels associated with transfusion of longer stored blood produced no measurable changes in parenchymal lung injury (43); 4) in antibiotic-treated canine pneumonia with and without RBC transfusion, the addition of haptoglobin therapy, a protein that binds CFH and compartmentalizes it intravascularly, increases CFH clearance, lowering CFH and iron levels, and is associated with decreased parenchymal lung injury and mortality rates (28); 5) altering the model of canine pneumonia to prevent haptoglobin-associated clearance of CFH and iron with and without RBC transfusion abrogates all beneficial clinical outcomes associated with haptoglobin (42); and finally, 6) in our antibiotic-treated bacterial pneumonia model, clinical outcomes such as parenchymal lung injury and mortality rates were increased when we administered commercial iron preparations (27).

Small animal models further support the role of targeting CFH, or its components, as a potential therapy for sepsis. In a rat model of cecal-ligation and puncture (CLP), haptoglobin administration decreased mortality, a beneficial outcome associated with lower CFH levels (45). Administering hemopexin, a molecule that binds and sequesters heme, to septic wild-type mice undergoing high-grade CLP also significantly decreased mortality rates (46). A recent multicenter-randomized clinical trial of a CFH-based NO scavenger for treatment of vasopressor-dependent shock also supports the role of targeting CFH and blocking its ability to scavenge NO, as a potential therapy for sepsis. The trial enrolling predominantly patients with sepsis had to be stopped early due to increased prevalence of adverse events including mortality and multiorgan failure associated with giving a CFH-based NO scavenger (47).

There are several limitations in our animal model. Antibiotics were administered to increase the relevance of the model to clinical human infections; however, this caused cultures for the infecting agent to become uninformative and precluded our ability to perform meaningful quantitative blood and sputum bacterial cultures. Bronchoalveolar lavage to obtain cultures in previous studies could not be performed without adversely affecting outcomes and had to be abandoned. A qualitative measure of increased lung parenchymal injury in this model by histopathology has previously been published (14). Another limitation to the generalizability of our findings is that we included only male animals to limit variability in our study population. A potential source of variability in this model was that the dose of bacterial inoculum varied from 0.4 CFU/kg to 0.9 CFU/kg and the duration of CFH infusion was increased from 6 to 12 h. However, within each cycle, animals challenged with CFH and/or bacteria received the same dose and duration; therefore, no group was disadvantaged within each cycle and all effects seen were first determined within each week and then averaged over weeks. Measurements of IL-22, NO, haptoglobin, hemopexin, induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and constitutive nitric oxide synthase (cNOS) levels, if obtained, would have likely been informative and helped us better understand the mechanisms underlying the mortality and morbidity seen in this animal model.

In summary, this study provides insights into mechanisms of CFH toxicity in a canine model of bacterial pneumonia and sepsis. We and others have shown in large and small animal models that targeting CFH during sepsis improves clinical outcomes (28, 45, 46). These study findings are consistent with the notion that CFH elevations alone can worsen pneumonia and thereby mortality through the use of released iron by infecting bacteria, despite antibiotic treatment. In addition, CFH worsens shock, multiorgan failure, and the lethality of sepsis by scavenging NO, causing pulmonary hypertension and cardiogenic shock. These findings support targeting CFH as a novel biologically plausible, nonantibiotic early approach to sepsis aimed at decreasing the severity of source infections, and lessening or preventing shock, multiorgan-failure, and lethality associated with sepsis.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support this study are available at:

Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067002.v1

Supplemental Table S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066987.v1

Supplemental Table S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14454219.v1

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066969

Supplemental Fig. S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067014.v1

Supplemental Fig. S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066996.v1

Supplemental Fig. S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067005.v1

Supplemental Fig. S5: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067008.v1

Supplemental Fig. S6: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066972.v1

Supplemental Fig. S7: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066978.v1

Supplemental Fig. S8: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066990.v1

Supplemental Fig. S9: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066993.v1

Supplemental Fig. S10: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066981.v1

Supplemental Fig. S11: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066984.v1

Supplemental Fig. S12: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066999.v1

Supplemental Fig. S13: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067011.v2

Supplemental Fig. S14: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066975.v3

Supplemental Fig. S15: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066966.v2

GRANTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) intramural funding from the Clinical Center and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, by the NIH extramural Grants R01 HL098032 and P01 HL103455 (to M.T.G.), R01 HL125886 (to J.T. and M.T.G.), and HL09832 (to D.B.K-S.), and by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania grants (to M.T.G).

DISCLOSURES

M.T.G. and D.B.K-S. are coinventors in patents for the treatment of hemolysis (Patent No. 8980871 and 9114109). M.T.G. and J.T. are coinventors of pending patent applications and planned patents directed to the use of recombinant neuroglobin and heme-based molecules as antidotes for CO poisoning, which have recently been licensed by Globin Solutions Inc. M.T.G. and J.T. are shareholders and directors in Globin Solutions Inc. In addition, and unrelated to CO poisoning, M.T.G. and D.B.K-S. are coinventors on patents directed to the use of nitrite salts in cardiovascular diseases, which have been licensed by the United Therapeutics and Hope Pharmaceuticals, and M.T.G. is a coinvestigator in a research collaboration with Bayer Pharmaceuticals to evaluate riociguat as a treatment for patients with sudden cardiac death.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.S., R.L.D., J.L., and C.N. conceived and designed research; J.W., W.N.A., S.B.S., J.F., Z.G.C., T.F.R., J.T., E.A., S.B., D.B.K-S., and M.T.G. performed experiments; J.S. analyzed data; J.W., W.N.A., R.L.D., V.S., D.B.K-S., M.T.G., H.G.K., and C.N. interpreted results of experiments; J.W. and W.N.A. prepared figures; J.W., W.N.A., D.B.K-S., M.T.G., H.G.K., and C.N. drafted manuscript; J.W., W.N.A., J.S., S.B.S., J.F., Z.G.C., T.F.R., R.L.D., J.T., J.L., E.A., S.B., V.S., D.B.K-S., M.T.G., H.G.K., and C.N. edited and revised manuscript; J.W., W.N.A., J.S., S.B.S., J.F., Z.G.C., T.F.R., R.L.D., J.T., J.L., E.A., S.B., V.S., D.B.K-S., M.T.G., H.G.K., and C.N. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Kelly Byrne and Juli Maltagliati for assistance with the manuscript and Andreas Perlegas for technical assistance. The work by the authors was done as a part of the US government-funded research; however, the opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Kadri SS, Angus DC, Danner RL, Fiore AE, Jernigan JA, Martin GS, Septimus E, Warren DK, Karcz A, Chan C, Menchaca JT, Wang R, Gruber S, Klompas M; CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US Hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA 318: 1241–1249, 2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall JC. Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol Med 20: 195–203, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman BD, Natanson C. Anti-inflammatory therapies in sepsis and septic shock. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 9: 1651–1663, 2000. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.7.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natanson C, Esposito CJ, Banks SM. The sirens' songs of confirmatory sepsis trials: selection bias and sampling error. Crit Care Med 26: 1927–1931, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quezado ZMN, Banks SM, Natanson C. New strategies for combatting sepsis: the magic bullets missed the mark…but the search continues. Trends Biotechnol 13: 56–63, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)88906-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeni F, Freeman B, Natanson C. Anti-inflammatory therapies to treat sepsis and septic shock: a reassessment. Crit Care Med 25: 1095–1100, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamzik M, Hamburger T, Petrat F, Peters J, de Groot H, Hartmann M. Free hemoglobin concentration in severe sepsis: methods of measurement and prediction of outcome. Crit Care 16: R125, 2012. doi: 10.1186/cc11425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janz DR, Bastarache JA, Peterson JF, Sills G, Wickersham N, May AK, RobertsLJ, 2nd, Ware LB. Association between cell-free hemoglobin, acetaminophen, and mortality in patients with sepsis: an observational study. Crit Care Med 41: 784–790, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182741a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buehler PW, Humar R, Schaer DJ. Haptoglobin therapeutics and compartmentalization of cell-free hemoglobin toxicity. Trends Mol Med 26: 683–697, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladwin MT, Kanias T, Kim-Shapiro DB. Hemolysis and cell-free hemoglobin drive an intrinsic mechanism for human disease. J Clin Invest 122: 1205–1208, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI62972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janz DR, Ware LB. The role of red blood cells and cell-free hemoglobin in the pathogenesis of ARDS. J Intensive Care 3: 20, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato GJ, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest 127: 750–760, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI89741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gbotosho OT, Kapetanaki MG, Kato GJ. The worst things in life are free: the role of free heme in sickle cell disease. Front Immunol 11: 561917, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.561917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon SB, Wang D, Sun J, Kanias T, Feng J, Helms CC, Solomon MA, Alimchandani M, Quezado M, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Mortality increases after massive exchange transfusion with older stored blood in canines with experimental pneumonia. Blood 121: 1663–1672, 2013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-462945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donadee C, Raat NJH, Kanias T, Tejero J, Lee JS, Kelley EE, Zhao X, Liu C, Reynolds H, Azarov I, Frizzell S, Meyer EM, Donnenberg AD, Qu L, Triulzi D, Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cell microparticles and cell-free hemoglobin as a mechanism for the red cell storage lesion. Circulation 124: 465–476, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berra L, Pinciroli R, Stowell CP, Wang L, Yu B, Fernandez BO, Feelisch M, Mietto C, Hod EA, Chipman D, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Bloch KD, Zapol WM. Autologous transfusion of stored red blood cells increases pulmonary artery pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190: 800–807, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0850OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB. Storage lesion in banked blood due to hemolysis-dependent disruption of nitric oxide homeostasis. Curr Opin Hematol 16: 515–523, 2009. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833157f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, Hogg N, Cannon RO, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med 8: 1383–1389, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Zhi H, Yuen PST, Star RA, Banks SM, Schechter AN, Natanson C, Gladwin MT, Solomon SB. Hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction mediated by accelerated NO inactivation by decompartmentalized oxyhemoglobin. J Clin Invest 115: 3409–3417, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI25040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alayash AI. Redox biology of blood. Antioxid Redox Signal 6: 941–943, 2004. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortes GB, Alves LS, de Oliveira R, Dutra FF, Rodrigues D, Fernandez PL, Souto-Padron T, De Rosa MJ, Kelliher M, Golenbock D, Chan FKM, Bozza MT. Heme induces programmed necrosis on macrophages through autocrine TNF and ROS production. Blood 119: 2368–2375, 2012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin T, Maita D, Thundivalappil SR, Riley FE, Hambsch J, Van Marter LJ, Christou HA, Berra L, Fagan S, Christiani DC, Warren HS. Hemopexin in severe inflammation and infection: mouse models and human diseases. Crit Care 19: 166, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0885-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olonisakin TF, Suber TL, Gonzalez-Ferrer S, Xiong Z, Penaloza HF, van der Geest R, Xiong Y, Osei-Hwedieh DO, Tejero J, Rosengart MR, Mars WM, Tyne DV, Perlegas A, Brashears S, Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT, Bachman MA, Hod EA, St Croix C, Tyurina YY, Kagan VE, Mallampalli RK, Ray A, Ray P, Lee JS. Stressed erythrophagocytosis induces immunosuppression during sepsis through heme-mediated STAT1 dysregulation. J Clin Invest 131: e137468, 2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI137468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SK, Ding JL. A perspective on the role of extracellular hemoglobin on the innate immune system. DNA Cell Biol 32: 36–40, 2013. doi: 10.1089/dna.2012.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hod EA, Spitalnik SL. Harmful effects of transfusion of older stored red blood cells: iron and inflammation. Transfusion 51: 881–885, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porcheron G, Garenaux A, Proulx J, Sabri M, Dozois C. Iron, copper, zinc, and manganese transport and regulation in pathogenic Enterobacteria: correlations between strains, site of infection and the relative importance of the different metal transport systems for virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3: 90, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suffredini DA, Xu W, Sun J, Barea‐Mendoza J, Solomon SB, Brashears SL, Perlegas A, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C, Cortes-Puch I. Parenteral irons versus transfused red blood cells for treatment of anemia during canine experimental bacterial pneumonia. Transfusion 57: 2338–2347, 2017. doi: 10.1111/trf.14214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remy KE, Cortés-Puch I, Solomon SB, Sun J, Pockros BM, Feng J, Lertora JJ, Hantgan RR, Liu X, Perlegas A, Warren HS, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Haptoglobin improves shock, lung injury, and survival in canine pneumonia. JCI Insight 3: e123013, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Z, Shiva S, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP, Ringwood LA, Irby CE, Huang KT, Ho C, Hogg N, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Enzymatic function of hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase that produces NO under allosteric control. J Clin Invest 115: 2099–2107, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI24650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tejero J, Basu S, Helms C, Hogg N, King SB, Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Low NO concentration dependence of reductive nitrosylation reaction of hemoglobin. J Biol Chem 287: 18262–18274, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zijlstra WG, Buursma A, van Assendelft OW. Visible and Near Infrared Absorption Spectra of Human and Animal Haemoglobin: Determination and Application. The Netherlands: VSP International Science Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natanson C, Danner RL, Elin RJ, Hosseini JM, Peart KW, Banks SM, MacVittie TJ, Walker RI, Parrillo JE. Role of endotoxemia in cardiovascular dysfunction and mortality. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus challenges in a canine model of human septic shock. J Clin Invest 83: 243–251, 1989[Erratum inJ Clin Invest83: 1087, 1989]. doi: 10.1172/JCI113866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brissot P, Ropert M, Le Lan C, Loréal O. Non-transferrin bound iron: a key role in iron overload and iron toxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1820: 403–410, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, Kuebler WM; Acute Lung Injury in Animals Study Group. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 725–738, 2011. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13: 509–519, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hod EA, Zhang N, Sokol SA, Wojczyk BS, Francis RO, Ansaldi D, Francis KP, Della-Latta P, Whittier S, Sheth S, Hendrickson JE, Zimring JC, Brittenham GM, Spitalnik SL. Transfusion of red blood cells after prolonged storage produces harmful effects that are mediated by iron and inflammation. Blood 115: 4284–4292, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-245001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helms CC, Marvel M, Zhao W, Stahle M, Vest R, Kato GJ, Lee JS, Christ G, Gladwin MT, Hantgan RR, Kim-Shapiro DB. Mechanisms of hemolysis-associated platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost 11: 2148–2154, 2013. doi: 10.1111/jth.12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villagra J, Shiva S, Hunter LA, Machado RF, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ. Platelet activation in patients with sickle disease, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and nitric oxide scavenging by cell-free hemoglobin. Blood 110: 2166–2172, 2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhasym A, Annarapu GK, Saha S, Shrimali N, Gupta S, Seth T, Guchhait P. Neutrophils develop rapid proinflammatory response after engulfing Hb-activated platelets under intravascular hemolysis. Clin Exp Immunol 197: 131–140, 2019. doi: 10.1111/cei.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Güell E, Martín-Fernandez M, De la Torre MC, Palomera E, Serra M, Martinez R, Solsona M, Miro G, Valles J, Fernandez S, Cortes E, Ferrer V, Morales M, Yebenes JC, Almirall J, Bermejo-Martin JF. Impact of lymphocyte and neutrophil counts on mortality risk in severe community-acquired pneumonia with or without septic sshock. J Clin Med 8: 754, 2019. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conroy BS, Grigg JC, Kolesnikov M, Morales LD, Murphy MEP. Staphylococcus aureus heme and siderophore-iron acquisition pathways. Biometals 32: 409–424, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10534-019-00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Remy KE, Cortés-Puch I, Sun J, Feng J, Lertora JJ, Risoleo T, Katz J, Basu S, Liu X, Perlegas A, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C, Solomon SB. Haptoglobin therapy has differential effects depending on severity of canine septic shock and cell-free hemoglobin level. Transfusion 59: 3628–3638, 2019. doi: 10.1111/trf.15567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon SB, Cortés-Puch I, Sun J, Remy KE, Wang D, Feng J, Khan SS, Sinchar D, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Transfused older stored red blood cells improve the clinical course and outcome in a canine lethal hemorrhage and reperfusion model. Transfusion 55: 2552–2563, 2015. doi: 10.1111/trf.13213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Cortés-Puch I, Sun J, Solomon SB, Kanias T, Remy KE, Feng J, Alimchandani M, Quezado M, Helms C, Perlegas A, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Transfusion of older stored blood worsens outcomes in canines depending on the presence and severity of pneumonia. Transfusion 54: 1712–1724, 2014. doi: 10.1111/trf.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang H, Wang H, Levine YA, Gunasekaran MK, Wang Y, Addorisio MM, Zhu S, Li W, Li J, de Kleijn DP, Olofsson PS, Warren HS, He M, Al-Abed Y, Roth J, Antoine DJ, Chavan SS, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Identification of CD163 as an antiinflammatory receptor for HMGB1-haptoglobin complexes. JCI Insight 1: e85375, 2016. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen R, Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Tokaji L, Bozza FA, Japiassú AM, Bonaparte D, Cavalcante MM, Chora A, Ferreira A, Marguti I, Cardoso S, Sepulveda N, Smith A, Soares MP. A central role for free heme in the pathogenesis of severe sepsis. Sci Transl Med 2: 51ra71, 2010. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vincent J-L, Privalle CT, Singer M, Lorente JA, Boehm E, Meier-Hellmann A, Darius H, Ferrer R, Sirvent J-M, Marx G, DeAngelo J. Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study of pyridoxalated hemoglobin polyoxyethylene in distributive shock (PHOENIX). Crit Care Med 43: 57–64, 2015. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available at:

Supplemental Table S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067002.v1

Supplemental Table S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066987.v1

Supplemental Table S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14454219.v1

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066969

Supplemental Fig. S2: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067014.v1

Supplemental Fig. S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066996.v1

Supplemental Fig. S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067005.v1

Supplemental Fig. S5: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067008.v1

Supplemental Fig. S6: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066972.v1

Supplemental Fig. S7: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066978.v1

Supplemental Fig. S8: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066990.v1

Supplemental Fig. S9: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066993.v1

Supplemental Fig. S10: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066981.v1

Supplemental Fig. S11: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066984.v1

Supplemental Fig. S12: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066999.v1

Supplemental Fig. S13: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14067011.v2

Supplemental Fig. S14: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066975.v3

Supplemental Fig. S15: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14066966.v2