Abstract

Objective Reconstruction after open surgery of anterior skull base lesions is challenging. The fascia lata graft is our workhorse for achieving dural sealing and preventing cerebrospinal fluid leak and meningitis. This study seeks to analyze the donor and recipient site complication rates after fascia lata reconstruction.

Methods This is a retrospective review of all open anterior skull base operations in which a double-layer fascia lata graft was used for the reconstruction of the defect from 2000 to 2016 at the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, a tertiary referral center in Israel.

Results Of the 369 patients operated for skull base lesions, 119 underwent open anterior skull base surgery and were reconstructed with a fascia lata graft. The patients' mean age was 47.1 years, and 68 (57.1%) were males. The overall postoperative early and late donor site complication rates were 6.7% ( n = 8) and 5.9% ( n = 7), respectively. Multivariate analysis found minor comorbidities and persistent/recurrent disease as being predictors for early-term complications. The overall postoperative early central nervous system (CNS) complication rate was 21.8% ( n = 26), while 12.6% ( n = 15) of the patients had late postoperative CNS complications.

Conclusion Reconstruction of open anterior skull base lesions with fascia lata grafting is a safe procedure with acceptable complication and donor site morbidity rates.

Keywords: skull base, donor site morbidity, fascia lata, complications

Introduction

Introduced in 1934, the fascia lata free graft has become a substitute for reconstructing a variety of soft tissue defects involving the pericardium, pleura, eyelids, facial nerve, abdominal regions, tendons, and joint capsules. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 This is due to its many advantages as a durable autologous tissue, especially when ample tissue is needed. 8 9 Tumors involving the anterior skull base area pose a special challenge for reconstruction. Reconstruction of that area with local and regional vascularized flaps is often not an option due to tissue insult of neoadjuvant radiotherapy or to tumor involvement. 10 11 The devascularized fascia lata free graft has become a workhorse for anterior skull base reconstruction, especially when the dura is involved. It can offer a watertight sealing suitable for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak from dural defects and a barrier between the intracranial and nasal cavities. 12 13 14 15 16 17 Its harvesting is relatively simple, obviating the need for experienced microvascular team, expensive instrumentation, and postoperative intensive management while its remote location enables simultaneously harvesting the graft while ablating skull base lesions, thus shortening operating time as opposed to various locoregional flaps. Since its implementation, refinements have been made to lower donor site morbidity and improve graft survival rates. 5 18 19 20

Publications describing donor site morbidity are scarce, and those that are available were conducted on small samples. 5 21 22 23 This report contributes data on a large number of open skull base surgeries that were performed over a period of 17 years. We believe that the identification and description of the donor site and central nervous system (CNS) complications associated with these rare surgeries will enhance the understanding of the sequelae associated with fascia lata free grafting and assist in the treatment of individual patients.

Methods

Study Design

We reviewed the medical records of all patients who were operated for skull base lesions at the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center between 2000 and 2016. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB 0730-TLV-14), and patient consent was waived. A computer-assisted search performed by the institutional operation registry identified 446 patients who were operated for skull base lesions during the study period.

A total of 369 patients underwent open skull base surgery, of whom 119 underwent open anterior skull base surgery and were reconstructed with a fascia lata graft. The medical charts of all 119 patients were reviewed to retrieve the following data: demographics, imaging studies, comorbidities, disease characteristics, surgical approach and extension (pterygopalatine fossa, infratemporal fossa, cavernous sinus, orbital, dural, and intracranial extension), adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, reconstruction method, surgical final histology (benign/malignant), and postoperative recipient and donor site morbidity. Follow-up data on all patients were obtained from the clinical notes, imaging studies, and histopathological results.

Patient comorbidities were defined according to a modified Charlson comorbidity score (minor: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac arrhythmias, coagulopathies, and smoking; major: coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic renal failure). 24

Complications were referred to as either early (<30 days postsurgery) or late (>30 days postsurgery), and they were divided into those involving the CNS (CSF leak, meningitis, hemorrhage, neuronal injury, pneumocephalus, cerebral edema, and new onset of seizures), and those involving the donor site (hematoma, deep vein thrombosis, infected seroma, wound dehiscence, skin necrosis, and hypoesthesia). We compared the group of patients who had donor site complications with those who did not and the groups of patients who had CNS complications with those who did not. We specifically looked at the complications that appeared during the early and late postoperative periods and conducted univariate and multivariate analyses to identify predictive factors for the development of complications.

The same surgical team performed all the procedures in the study period with a uniform method for graft harvesting and reconstruction.

Our Surgical Technique

Fascia Lata Harvesting

The patient is lying in a supine position with the thigh slightly flexed; the lateral aspect of the thigh is prepped and draped. Preoperative intravenous antibiotics are given, which usually includes a Metronidazole for anaerobic bacteria and a Cephalosporins for aerobic organisms. An S-shaped incision line is marked 5 to 7 cm proximal to the lateral femoral condyle with its axis directed toward the hip joint and centered over a mid-lateral thigh line. The proximal peak of the incision line curves posteriorly, in this manner, the scar is positioned laterally, making it less noticeable. We use an up to 10 cm incision line of 3 cm amplitudes located at 8 to 9 cm proximal to the knee joint. This enables the harvesting of up to 10 × 20 cm fascial sheath ( Fig. 1 ). The skin flaps are sharply elevated above the fascia lata and reflected laterally using self-retaining Jannetta retractor. The fascial sheath is cut longitudinally with slightly opened tips of scissors by gently pushing them along the fibers. A parallel transverse incision is made proximally upon reaching the desired length of the graft. After harvesting, the graft is draped with a wet dressing until used.

Fig. 1.

Generous pieces of fascia lata graft can be harvested reaching up to 10 × 20 cm. Left, skin incision dimensions; right, fascia lata before harvesting.

Subcutaneous fat tissue can be harvested if required and available. After meticulous hemostasis, the fascia and skin are closed in layers using subcutaneous interrupted 4/0 Vicryl sutures and intradermal Monocryl 4/0 sutures. A vacuum drain is left in place for 24 to 48 hours or until fewer than 25 to 30 mL/24 h of fluid is drained. 8 9

Defect Reconstruction

Primary closure of the dura is performed whenever possible. A temporalis fascia graft is used if the defect is small. If tumor resection results in an extensive skull base defect, either the same surgical team, consecutively to the skull base operation, or a second surgical team, simultaneously, will harvest the fascia lata sheath. The size of the fascia used for reconstruction is tailored to the site and dimensions of the dural and skull base defects. The fascia is tacked under the edges of the dura and carefully sutured in place. The dural repair is then covered with a second layer of fascia that is applied against the entire undersurface of the involved sinus wall ( Fig. 2 ). Fibrin glue is used to provide additional protection against CSF leak. Following dural repair, Vaseline gauze is applied below the dura and into the paranasal cavity to provide additional support against dural pulsation. 12 Part of our postoperative treatment protocol is 5 days postoperative antibiotic therapy with Metronidazole and Cephalosporins.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography demonstrates double-layer reconstruction with fascia lata graft. Left, sagittal view; right, coronal view.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described by frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were evaluated for normal distribution using histograms and Q–Q plots and expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the t -test or the Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p -value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corp., released in 2014; IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, New York, United States).

Results

A total of 119 patients underwent open anterior skull base surgery and were reconstructed with fascia lata flaps. Their average age was 47.1 years (IQR: 32.6, 62), and 68 patients (57.1%) were males. Eight patients (6.7%) had early donor site complications, and seven (5.9%) had late donor site complications ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Donor site complications.

| Early donor site complications n = 8 (6.7%) |

Late donor site complications n = 7 (5.9%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematoma | 3 | Seroma | 4 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 | Infected seroma + dehiscence | 1 |

| Infected seroma + dehiscence | 1 | Hematoma | 1 |

| Dehiscence + skin necrosis | 1 | Hypoesthesia | 1 |

| Hypoesthesia | 1 | ||

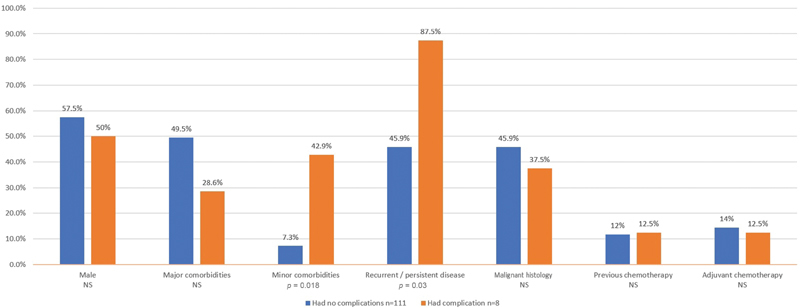

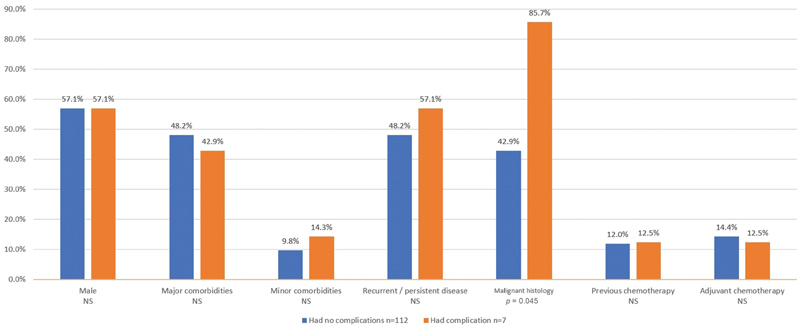

There was no significant age difference between the patients who had early donor site complications and those who had no complications (47 vs. 49.1 years, respectively, p > 0.999), or between patients with late donor site complications and those who had no complications (46.9 vs. 50.4 years, p = 0.911). No significant difference was found in the rate of previous or adjuvant treatment between the groups. Minor comorbidities and recurrent or persistent disease were found to be predictors for early donor site complications in both the univariate and multivariate analyses ( Fig. 3 ). Malignancy emerged as a predicting factor for late donor site complications in the univariate analysis ( Fig. 4 ), while multivariate analysis did not identify any predicting factor for late donor site complications.

Fig. 3.

Predictors for early donor site complications (univariate analysis). NS, nonsignificant.

Fig. 4.

Predictors for late donor site complications (univariate analysis). NS, nonsignificant.

The hospitalization periods were also similar for the patients who had early donor site complications and for those who had no complications (13.3 vs. 16 days, p = 0.121), as well as for patients who had late donor site complications and those who had no complications (13.4 vs. 14.8 days, p = 0.111).

We then analyzed the patients who developed CNS complications. The results showed that 26 (21.8%) of the patients had early CNS complications (13 had meningitis, 1 had a CSF leak, 10 had pneumocephalus, 5 had seizures, 1 had encephalitis, 1 had a cerebrovascular accident [CVA], and 1 had epidural abscess). Previous surgery or chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy were not found as predictors for early CNS complications development. Malignant histology and lumbar drainage were found to be predictors for developing early CNS complications ( Figs. 5 and 6 ), as did multivariate analysis ( Table 2 ). Tumor extension did not influence the early CNS complications rate ( Fig. 6 ). Fifteen patients (12.6%) had late CNS complications (six had seizures, two had meningitis, two had a CSF leak, two had a cerebral abscess, one had pneumocephalus, one had encephalitis, and one had a CVA). Univariate and multivariate analyses did not identify any predictors for late CNS complications.

Fig. 5.

Predictors for early central nervous system complications (univariate analysis). NS, nonsignificant.

Fig. 6.

Predictors for early central nervous system complications—tumor extension (univariate analysis). ITF, infratemporal fossa; NS, nonsignificant; PPF, pterygopalatine fossa.

Table 2. Predictors for early central nervous system complications (multivariate analysis).

| p -Value | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.994 | 1.004 |

| Major comorbidities | 0.912 | 1.065 |

| Minor comorbidities | 0.390 | 0.352 |

| Previous treatment (surgery/radio/chemotherapy) | 0.626 | 0.682 |

| Adjuvant treatment (chemoradiotherapy) | 0.724 | 0.621 |

| Recurrent/persistent disease | 0.127 | 3.518 |

| Malignant histology | 0.023 | 0.253 |

| Lumbar drainage | 0.013 | 15.469 |

| Dural extension | 0.999 | 1.098 |

| Intracranial extension | 0.121 | 2.731 |

Discussion

Resection of lesions from the anterior skull base leaves a complex three-dimensional deficit at the skull base and adjacent vital structures. Reconstruction in this anatomical location is challenging and failure may lead to fatal complications including pneumocephalus, CSF leak, meningitis, seizures, and others. The goals of skull base reconstruction are to achieve a dural sealing to prevent CSF leak, to isolate the intracranial content from the nasal cavity and sinuses, and to support the local tissue to withstand the effect of pre- or postoperative radiotherapy. Available dural grafting sources are allogeneic and synthetic materials, as well as autologous materials, such as the temporoparietal fascia, pericranium, and fascia lata. The use of the fascia lata is one of the available sources of choice, especially when a broad tissue graft is needed. 12 13 14 15 16 17

The present study represents the largest study describing donor site morbidity of open skull base reconstruction with fascia lata graft.

The ideal reconstruction material should have excellent tissue compatibility, be easily contoured, and be able to retain a stable shape. Our group previously investigated the healing process of fascia lata grafts in three patients who had undergone a second surgery. Fragments of fascia lata that had previously been used for skull base reconstruction and were not involved with the tumor were excised and histopathologically evaluated. The histological findings demonstrated an almost complete fibrous replacement of the fascia lata graft. 25 In our current study, we identified early and late donor site complications of the fascia lata graft after open anterior skull base operations. In our cohort of 119 patients, 8 patients (6.7%) had early donor site complications, and the multivariate analysis identified minor comorbidities and persistent/recurrent disease as predictors for such complications. Late complications occurred in seven patients (5.9%), but the multivariate analysis was unable to identify predictors for them. The most common early donor site complications were hematoma, followed by deep vein thrombosis, infected seroma, and dehiscence. These complications occurrence could be explained by the related documented comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, cardiac arrhythmias, and smoking. In the current study, the donor site incision and defect size were not referred, but these might have contributed to the formation of wound complications such as seroma, dehiscence, and hematoma ( Table 1 ).

Mattavelli et al identified 3.2% of overall donor site complications after fascia lata harvest for endoscopic skull base reconstruction, and reported a similar distribution of complications type to those of our cohort. Their results, like ours, did not show higher rates of complications after neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy treatment. Those authors also administrated donor site morbidity questionnaires, and the results were completely satisfactory in terms of both functional and cosmetic outcomes. Of note, the incidence of complications in the few other published reports with smaller cohorts is similar to our rate. 23 26 Earlier studies on fascia lata complications for ptosis surgery, which is obviously achieved with smaller graft size, found lower satisfaction in the first week, which improved with time. 21 22 In our cohort of patients, 21.8% ( n = 26) had early, and 12.6% ( n = 15) had late CNS complications, and these rates are also similar to large published studies. 10 11

In an effort to identify the patients who had early CNS complications after fascia lata reconstruction, our univariate and multivariate analyses found that malignant histology and the use of continuous lumbar drainage were predictors for CNS complications. These results are compatible with our recent finding of a higher CNS complications rate with the routine use of lumbar drainage in open anterior skull base operations. 27

Limitations of this study include an inherent bias that is associated with retrospective analysis. This study does not compare reconstruction with fascia lata to other reconstructive methods and focuses on open approaches to the anterior skull base. The encouraging results of this study should promote head to head prospective comparison of various reconstructive methods of open anterior skull base defects.

Conclusions

Reconstruction with a fascia lata graft after the ablation of anterior open skull base lesions is a safe procedure with acceptable complications and donor site morbidity rates. It offers minimal postoperative dysfunction, with the risk of developing CNS complications equivalent to other reconstruction methods described in the literature.

Acknowledgments

Esther Eshkol, MA, the institutional medical and scientific copyeditor (Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center), provided editorial assistance. Tomer Ziv, PhD, provided statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Ono J, Takeda A, Akimoto M. Free tensor fascia lata flap and synthetic mesh reconstruction for full-thickness chest wall defect. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:914716. doi: 10.1155/2013/914716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kageyama Y, Suzuki K, Matsushita K, Nogimura H, Kazui T. Pericardial closure using fascia lata in patients undergoing pneumonectomy with pericardiectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66(02):586–587. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasserman B N, Sprunger D T, Helveston E M. Comparison of materials used in frontalis suspension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(05):687–691. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies H. Experiences with fascia lata grafts in the operative treatment of facial paralysis: (section of otology and section of laryngology) Proc R Soc Med. 1934;27(10):1372–1382. doi: 10.1177/003591573402701039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley S J, Adamson A S. Minimally invasive harvesting of fascia lata for use in the pubovaginal sling procedure. BJU Int. 2001;88(03):293–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stensbirk F, Thorborg K, Konradsen L, Jørgensen U, Hölmich P. Iliotibial band autograft versus bone-patella-tendon-bone autograft, a possible alternative for ACL reconstruction: a 15-year prospective randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(09):2094–2101. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2630-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedrich J B, Hanel D P, Chilcote H, Katolik L I. Management of Posttraumatic Radioulnar Synostosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:450–458. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-07-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amir A, Gur E, Gatot A, Zucker G, Cohen J T, Fliss D M. Fascia lata sheaths harvest revisited. Oper Tech Otolaryngol--Head Neck Surg. 2000;11(04):304–306. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amir A, Gatot A, Zucker G, Sagi A, Fliss D M. Harvesting large fascia lata sheaths: a rational approach. Skull Base Surg. 2000;10(01):29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganly I, Patel S G, Singh B. Complications of craniofacial resection for malignant tumors of the skull base: report of an International Collaborative Study. Head Neck. 2005;27(06):445–451. doi: 10.1002/hed.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus D H, Shah J P, Arbit E, Galicich J H, Strong E W. Complications of craniofacial resection for tumors involving the anterior skull base. Head Neck. 1994;16(04):307–312. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880160403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil Z, Abergel A, Leider-Trejo L. A comprehensive algorithm for anterior skull base reconstruction after oncological resections. Skull Base. 2007;17(01):25–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ketcham A S, Hoye R C, Van Buren J M, Johnson R H, Smith R R. Complications of intracranial facial resection for tumors of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg. 1966;112(04):591–596. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(66)90327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon D, Iloreta A, Miles B, Inman J. Open anterior skull base reconstruction: a contemporary review. Semin Plast Surg. 2017;31(04):189–196. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klatt-Cromwell C N, Thorp B D, Del Signore A G, Ebert C S, Ewend M G, Zanation A M. Reconstruction of skull base defects. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49(01):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gullane P J, Lipa J E, Novak C B, Neligan P C.Reconstruction of skull base defects Clin Plast Surg 20053203391–399., vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattavelli D, Schreiber A, Ferrari M. Three-layer reconstruction with iliotibial tract after endoscopic resection of sinonasal tumors. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Link M J, Converse L D, Lanier W L.A new technique for single-person fascia lata harvest Neurosurgery 200863(04, Suppl 2):359–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naugle T C, Jr, Fry C L, Sabatier R E, Elliott L F. High leg incision fascia lata harvesting. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(09):1480–1488. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tay V S-L, Tan K S, Loh I CY. Minimally invasive fascia lata harvest: a new method. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1(01):1–2. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0b013e31828c4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattavelli D, Schreiber A, Villaret A B. Complications and donor site morbidity of 3-layer reconstruction with iliotibial tract of the anterior skull base: retrospective analysis of 186 patients. Head Neck. 2018;40(01):63–69. doi: 10.1002/hed.24931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheatcroft S M, Vardy S J, Tyers A G. Complications of fascia lata harvesting for ptosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(07):581–583. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitali M, Canevari F R, Cattalani A, Grasso V, Somma T, Barbanera A. Direct fascia lata reconstruction to reduce donor site morbidity in endoscopic endonasal extended surgery: a pilot study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;144(144):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson M, Szatrowski T P, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fliss D M, Gil Z, Spektor S. Skull base reconstruction after anterior subcranial tumor resection. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(05):e10. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.12.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chibber P J, Shah H N, Jain P. A minimally invasive technique for harvesting autologous fascia lata for pubo-vaginal sling suspension. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37(01):43–46. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-6080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ringel B, Carmel-Neiderman N N, Peri A. Continuous lumbar drainage and the postoperative complication rate of open anterior skull base surgery. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):2702–2706. doi: 10.1002/lary.27266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]