Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare the symptoms, treatment patterns, and quality of life (QoL) of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients to non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) patients in the USA.

Method

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with rheumatologists and their consulting patients in the USA from June through August 2018. Patients who had a rheumatologist confirmed diagnosis of AS and nr-axSpA were eligible to participate. Patient demographics, symptoms, and medication use were reported by the rheumatologist, while work disability and QoL measures were reported by the patient. Patient demographics, symptoms, QoL and treatment patterns of AS and nr-axSpA patients were compared using parametric tests and non-parametric tests when appropriate.

Results

A total of 515 AS patients and 495 nr-axSpA patients were included in this analysis. A higher proportion of AS patients were male (p < 0.001), older (p = 0.014), and more likely to be prescribed a biologic (p < 0.0001). On average, AS patients experienced slightly more symptoms at diagnosis (p = 0.023); however, nr-axSpA patients were more likely to experience enthesitis (p = 0.048) and synovitis (p = 0.003). Patient reported outcomes such as the ASAS Health Index (p = 0.171), ASQoL (p = 0.296), BASDAI (p = 0.124), and WPAI (p = 0.183) were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients after adjusting for confounding variables such as medication use.

Conclusions

AS and nr-axSpA patients share the same clinical features. The burden of the disease, as assessed by QoL measurements, is also similar in AS and nr-axSpA patients; however, despite these similarities, patients with nr-axSpA are less likely to be treated with a biologic.

Key Points

|

• Ankylosing spondylitis and non • radiographic axial spondyloarthritis patients share similar clinical features and burden of disease. • Quality of life is similar among ankylosing spondylitis and non • radiographic axial spondyloarthritis after adjusting for current treatment patterns. |

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, Quality of life, Treatment patterns

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that mainly affects the axial skeleton and sacroiliac joints [1]. It is estimated that up to 1.4% of the adult population in the USA have axSpA [2]. AxSpA is an umbrella term that includes patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) [3] and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) [4, 5]. Many rheumatologists and professional organizations, such as ASAS and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), consider AS and nr-axSpA to be part of one disease spectrum (axSpA) [6, 7]. AS in its most advanced expression can be characterized by severe spinal immobility and functional disability caused by fusion of the spine [8]. Patients with nr-axSpA can sometimes progress to AS; however, not all patients with nr-axSpA progress to AS [8]. Progression from nr-axSpA to AS has been reported to occur in approximately 5% to 12% of patients after 2 years [9, 10] and approximately 25% of patients after 15 years [11].

Differentiating AS and nr-axSpA based on symptoms, disease activity, function, and quality of life (QoL) may not be possible, as studies have shown many similarities between these two groups [12–14]. Studies comparing AS and nr-axSpA patients have predominately been conducted outside of the USA [12, 15, 16]. In this study, we compare the symptoms, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of AS patients and nr-axSpA in the USA in a real-world setting.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with rheumatologists and their patients in the USA from June through August 2018. The survey methodology was implemented as previously published [17] and adapted to the AS and nr-axSpA population. Rheumatologists seeing at least 10 AS and nr-axSpA patients in a typical month were eligible to participate in this cross-sectional survey.

A geographically representative sample of eligible rheumatologists (n = 88) in the USA was included in this study and completed patient record forms for the next ten consecutive axSpA patients (5 AS and 5 nr-axSpA). The diagnosis of AS or nr-axSpA was made by the clinical judgement of the rheumatologist. The rheumatologist completed the patient record forms which included patient demographics, disease status, remission status, clinical characteristics, and current medication use. Presence of symptoms were recorded by the rheumatologist by selecting the symptoms from a list provided.

AS and nr-axSpA patients were invited to complete a survey independent of their rheumatologist. As part of the survey, AS and nr-axSpA patients were asked to complete a patient declaration page where they agreed to complete the survey in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Patients provided consent for de-identified and aggregated reporting of research findings. Data were de-identified according to HIPAA regulations before receipt by Adelphi Real World. All questionnaires used in the survey were reviewed and approved by Western Institutional Review Board.

Patient-reported outcomes

Disease activity was measured using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [18, 19]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the following patient-reported outcome measures: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society Health Index (ASAS HI) [20], Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) [21], and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [22]. Work productivity and impact of axSpA on activity impairment outside of work was measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [23].

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted for the entire axSpA population and then stratified by AS and nr-axSpA patients. Summary statistics were used to compare patient demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and PROs between AS and nr-axSpA patients. Categorical variables were analyzed by frequency counts and percentages, with Chi-square tests used for subgroup analyses. Continuous variables were analyzed by mean (standard deviation [SD]), with two-sample t-tests used for subgroup analyses. In addition, ordinary least squared regressions were performed on the PRO variables after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), overall severity, and treatment. Marginal means were calculated based on the regression model.

Results

Demographics

A total of 1010 axSpA patients (AS, 515; nr-axSpA, 495) were included in this analysis; 570 axSpA patients completed the patient survey (AS, 284; nr-axSpA, 286). Demographic information for all axSpA patients, as well as those with AS and nr-axSpA, is included in Table 1. Overall, 62.5% (n = 631) of axSpA patients were male, had a mean age of 45.2 years, mean BMI of 27.3, and 77.7% were employed either full-time or part-time. A statistically higher proportion of AS patients were male (71.3% vs. 53.3%; p < 0.001) and older (mean age: 46.3 vs. 44.2; p = 0.014) when compared to nr-axSpA patients (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient-reported outcomes

| PRO measure | Concepts measured | Number of items | Response options | Score ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASDAI18-19 |

Disease activity including • Fatigue • Spinal pain • Peripheral arthritis • Enthesitis • Intensity of morning stiffness • Duration of morning stiffness |

6 | 0–10 numeric rating scale | 0–10 (“no disease activity” to “high disease activity”) |

| ASAS HI20 | Overall health and functioning | 17 | “I agree” (score 1), “I do not agree” (score 0), or “not applicable” (only for item 7 and 8). | 0–17 (“good health” to “poor health”) |

| ASQoL21 | Quality of life | 18 | “Yes (score 1)” or “No (score 0)” | 0–18 (“good QoL” to “poor QoL”) |

| EQ-5D VAS22 | Overall health status | 0–100 | 0–100 visual analogue scale | 0–100 (“the worst health you can imagine” to “the best health you can imagine”) |

| WPAI-SpA23 |

• Absenteeism • Presenteeism • Overall work impairment • Activity impairment |

6 | 0–10 numeric rating scale |

• Percentage of Absenteeism (0–100%) • Percentage of Presenteeism (0–100%) • Overall work impairment score (combining absenteeism and presenteeism) (0–100%) • Percentage of activity impairment (0–100%) |

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| axSpA patients N = 1010 |

AS patients N = 515 |

nr-axSpA patients N = 495 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 631 (62.5%) | 367 (71.3%) | 264 (53.3%) | |

| Female | 379 (37.5%) | 148 (28.7%) | 231 (46.7%) | |

| Age, mean | 45.2 | 46.3 | 44.2 | 0.014 |

| Ethnic, origin | 0.420 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 811 (80.3%) | 417 (81.0%) | 394 (79.6%) | |

| African American | 77 (7.6%) | 43 (8.3%) | 34 (6.9%) | |

| Native American | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.4%) | |

| Asian | 31 (3.1%) | 18 (3.5%) | 13 (2.6%) | |

| Middle Eastern | 8 (0.8%) | 3 (0.6%) | 5 (1.0%) | |

| Mixed race | 19 (1.9%) | 7 (1.4%) | 12 (2.4%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 60 (5.9%) | 25 (4.9%) | 35 (7.1%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean | 27.3 | 27.5 | 27.1 | 0.185 |

| Smoking status* | 0.634 | |||

| Current smoker | 101 (10.8%) | 48 (10.1%) | 53 (11.6%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 195 (20.9%) | 104 (21.8%) | 91 (19.9%) | |

| Never smoked | 638 (68.3%) | 325 (68.1%) | 313 (68.5%) | |

| Employment status** | 0.112 | |||

| Full-time | 708 (70.5%) | 364 (71.2%) | 344 (69.8%) | |

| Part-time | 72 (7.2%) | 33 (6.5%) | 39 (7.9%) | |

| Homemaker | 57 (5.7%) | 20 (3.9%) | 37 (7.5%) | |

| Student | 26 (2.6%) | 12 (2.3%) | 14 (2.8%) | |

| Unemployed | 43 (4.3%) | 23 (4.5%) | 20 (4.1%) | |

| Retired | 87 (8.7%) | 52 (10.2%) | 35 (7.1%) | |

| Long-term sick leave | 11 (1.1%) | 7 (1.4%) | 4 (0.8%) | |

| Disease status | 0.484 | |||

| Improving | 298 (29.5%) | 145 (28.2%) | 153 (30.9%) | |

| Stable | 557 (55.1%) | 282 (54.8%) | 275 (55.6%) | |

| Unstable | 87 (8.6%) | 47 (9.1%) | 40 (8.1%) | |

| Deteriorating | 66 (6.7%) | 41 (8.0%) | 27 (5.5%) | |

| In remission | 390 (41.5%) | 201 (42.2%) | 189 (40.7%) | 0.644 |

| Rheumatologist’s global assessment VAS***, mean | 31.8 | 32.4 | 31.1 | 0.744 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.222 |

| Joint inflammation or stiffness | 336 (33.3%) | 156 (30.3%) | 180 (36.4%) | 0.045 |

| Inflammatory back pain | 432 (42.8%) | 215 (41.7%) | 217 (43.8%) | 0.525 |

| Morning stiffness for more than 30 min | 372 (36.8%) | 193 (37.5%) | 179 (36.2%) | 0.696 |

| HLA B27 positive at diagnosis | 504 (54.3%) | 270 (57.9%) | 234 (50.6%) | 0.030 |

| Alternating buttock pain | 65 (6.4%) | 33 (6.4%) | 32 (6.5%) | 1.000 |

| Dactylitis | 27 (2.7%) | 13 (2.5%) | 14 (2.8%) | 0.846 |

| Enthesitis | 76 (7.5%) | 34 (6.6%) | 42 (8.5%) | 0.284 |

| Tendonitis | 81 (8.0%) | 45 (8.7%) | 36 (7.3%) | 0.419 |

| Synovitis | 69 (6.8%) | 31 (6.0%) | 38 (7.7%) | 0.320 |

| Arthritis | 176 (17.4%) | 92 (17.9%) | 84 (17.0%) | 0.740 |

| Osteoporosis of the spine | 31 (3.1%) | 24 (4.7%) | 7 (1.4%) | 0.003 |

*Smoking status: axSpA, n = 934; AS, n = 477; nr-axSpA n = 457

**Employment Status: axSpA, n = 1004; AS, n = 511; nr-axSpA, n = 493

***Physician’s Global Assessment: axSpA, n = 160; AS, n = 85; nr-axSpA, n = 75

Clinical characteristics and spondyloarthritis features

The clinical characteristics and extra-articular manifestations were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (Table 2). At the time of diagnosis, nr-axSpA patients were more likely than AS patients to have enthesitis (p = 0.048) and synovitis (p = 0.003). At the time of diagnosis, AS patients were more likely to have osteoporosis of the spine (p = 0.021) and elevated CRP (p = 0.022) and were HLA-B27 positive (p = 0.030) when compared to nr-axSpA patients.

Disease status and disease activity

The majority of axSpA patients’ current disease status was reported by their rheumatologist as stable or improving (84.6%). AS and nr-axSpA patients’ current disease status (p = 0.484) and remission rates were similar (42.2% vs. 40.7%; p = 0.644). The mean scores of the physician’s global assessment (PGA) in AS and nr-axSpA patients were comparable (32.4 vs. 31.1; p = 0.745). The mean score of the patient’s global assessment (PtGA) was 34.4 for AS and 31.5 for nr-axSpA patients, which was not statistically different (p = 0.447). Disease activity, as measured by the mean BASDAI, was also similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (p = 0.124).

Quality of life

PROs measuring overall function, health, and quality of life such as the ASAS HI, ASQoL, and EQ-5D VAS were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (Table 3). The mean ASAS HI score was 5.7 for AS patients and 5.2 for nr-axSpA patients (p = 0.171). The mean ASQoL score was 6.3 for AS patients and 5.8 for nr-axSpA patients (p = 0.296). The mean EQ-5D VAS was 75.7 for AS patients and 74.9 for nr-axSpA patients (p = 0.590). After adjusting for confounding variables, the marginal means of the ASAS HI, ASQoL, and EQ-5D VAS were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean and marginal means of patient reported outcome measures

| Means | Marginal means* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire score range | AS | nr-axSpA | p Value | AS | nr-axSpA | p Value | |

| ASAS Health Index | 0–17 | 5.7 (n = 274) | 5.2 (n = 276) | 0.171 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 0.295 |

| ASQoL | 0–18 | 6.3 (n = 272) | 5.8 (n = 273) | 0.296 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 0.383 |

| BASDAI | 0–10 | 3.2 (n = 276) | 2.9 (n = 276) | 0.124 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.414 |

| EQ-5D VAS | 0–100 | 75.7 (n = 277) | 74.9 (n = 276) | 0.590 | 76.4 | 74.2 | 0.122 |

| Patient’s global assessment VAS | 0–100 | 34.4 (n = 86) | 31.5 (n = 77) | 0.447 | 33.7 | 32.2 | 0.685 |

| WPAI | |||||||

| Absenteeism | 0–100 | 5.0 (n = 174) | 4.0 (n = 178) | 0.579 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 0.641 |

| Presenteeism | 0–100 | 21.3 (n = 189) | 21.9 (n = 188) | 0.749 | 21.9 | 21.2 | 0.655 |

| Overall work impairment | 0–100 | 23.1 (n = 170) | 23.6 (n = 175) | 0.788 | 23.8 | 22.9 | 0.663 |

| Activity impairment | 0–100 | 30.2 (n = 269) | 27.6 (n = 271) | 0.183 | 29.2 | 28.6 | 0.743 |

*Marginal means were calculated from the ordinary least squared regression models after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, Charlson Comorbidity Index, overall severity, and treatment

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

The majority of AS (n = 364; 71.2%) and nr-axSpA (n = 344; 69.8%) patients reported working full-time at the time of the survey. An additional 6.5% (n = 33) of AS patients and 7.9% (n = 39) of nr-axSpA patients indicated that they worked part-time at the time of the survey. Mean rates of absenteeism (p = 0.579), presenteeism (p = 0.749), work productivity (p = 0.788), and activity impairment (p = 0.183), as assessed by the WPAI questionnaire, were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (Table 3). These results did not differ when stratified by treatment. After adjusting for confounding variables, the marginal means of absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity, and activity impairment were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients (Table 3).

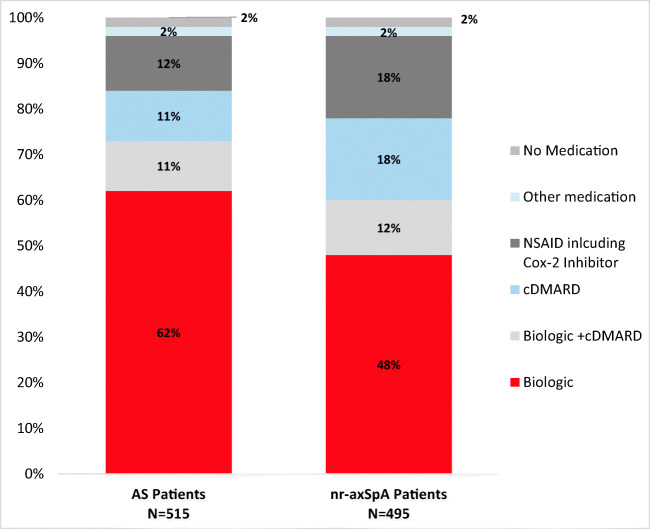

Medication use

Two-thirds (66.7%) of axSpA patients were currently receiving a biologic. Overall, 55.3% were receiving a biologic as monotherapy, and 11.4% were receiving a biologic in combination with a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (cDMARD) (Fig. 1). AS patients were more likely to receive a biologic than nr-axSpA patients (73.6% vs. 59.6%, p < 0.001). Nr-axSpA patients were more likely to be prescribed a cDMARD (18.4% vs. 11.1%) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)/Cox-2 Inhibitor (18.2% vs. 11.8%) than AS patients.

Fig. 1.

Current medication use

Discussion

This analysis of a large real-world survey of rheumatologists and their axSpA patients provides a comparison of AS and nr-axSpA patients in the USA. This analysis was conducted to compare clinical and demographic characteristics, disease activity, HRQoL, work impairment, and treatment patterns of AS and nr-axSpA patients. Similar to previous studies, our analysis showed that AS and nr-axSpA patients share many clinical symptoms and experience a similar burden of disease [12–14, 24]. The most important finding of our study is that despite the similar burden of disease, patients with nr-axSpA are receiving biologics less commonly than AS patients. Over two-thirds of AS patients were prescribed biologic therapy either as a monotherapy or in combination with a cDMARD. In comparison, only 59.6% of nr-axSpA patients were prescribed biologic therapy. Over one-third of nr-axSpA patients were prescribed a cDMARD or NSAID compared to only one-fourth of AS patients.

Consistent with previous literature, AS patients in our study were more likely to be male, older, and working full-time in comparison to nr-axSpA patients [12, 13, 15, 25]. The PtGA scores, PGA scores, current pain levels, and QoL were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients. These findings are comparable to those found in the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort (GESPIC), which reported no significant difference between PtGA and total pain score of AS and nr-axSpA patients [14].

Overall, there were few statistically significant differences in the clinical characteristics and symptoms reported by AS and nr-axSpA patients in our study. Patients with AS were more likely to be HLA-B27 positive when compared to nr-axSpA patients; however, the rates of HLA-B27 positivity among AS patients in our study (57.6%) was lower than that in previous research. In the Spanish REGISPONSER database, they reported that 83% of AS patients were HLA-B27 positive [26]. Our study also found that many AS and nr-axSpA patients have concomitant peripheral disease. Rates of arthritis, tendonitis, and dactylitis were similar between AS and nr-axSpA patients. Similar to the GESPIC cohort [14], AS patients in our study were more likely to have loss of movement and osteoporosis of the spine when compared to nr-axSpA patients. The more compromised function of patients with AS may be attributed to the structural changes in the spine [27].

The efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) treatment in nr-axSpA has been shown to be similar to that in AS, specifically in patients with objective signs of inflammation at baseline [16, 24, 28, 29]. The RAPID-axSpA [30] and ESTHER [16] studies both found that there was not a significant difference in treatment response between AS and nr-axSpA patients. As demonstrated in these studies as well as in our current study, the severity of symptoms, the disease activity, and the clinical characteristics of AS and nr-axSpA are similar between these two groups of patients.

While this study provides a comparison of AS and nr-axSpA patients in the USA and the results are primarily consistent with findings in different geographical areas, some limitations of this analysis should still be considered. There could be the potential for bias based on the recruitment strategy since rheumatologists voluntarily participating in this study selected ten consecutive consulting patients with axSpA. These patients may not be representative of axSpA patients in the USA that are not being treated by a rheumatologist. Additionally, rheumatologists were not required to include axSpA patients who fulfilled the formal classification criteria or clinical test results, so misclassification could exist. In the USA, at the time of this survey, there were no approved treatments for nr-axSpA, and therefore some patients may have been mislabeled as AS in order to get the treatment as recommended by their rheumatologist. Despite these limitations, this study provides evidence that the clinical characteristics, symptomology, quality of life, and disease status of AS and nr-axSpA patients in the USA are similar. The shared characteristics of these AS and nr-axSpA patients are consistent with the prevalent opinion that AS and nr-axSpA are two subtypes on the spectrum of axSpA. AS and nr-axSpA patients face the same burden and need the same level of access to targeted advanced treatment.

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All questionnaires used in the survey were reviewed and approved by Western Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest

TH and DS are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. EH and NB are employees of Adelphi Real World. AD has received grants or research support from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma and consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2017;390:73–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reveille J, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:905–901. doi: 10.1002/acr.21621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Braun J, Chou CT, Collantes-Estevez E, Dougados M, Huang F, Gu J, Khan MA, Kirazli Y, Maksymowych WP, Mielants H, Sorensen IJ, Ozgocmen S, Roussou E, Valle-Onate R, Weber U, Wei J, Sieper J. The development of Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–783. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, Listing J, Marker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:717–727. doi: 10.1002/art.24483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baraliakos X, Braun J. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: what are the similarities and differences? RMD Open. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deodhar A, Strand V, Kay J, Braun J. The term ‘non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis’ is much more important to classify than to diagnose patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:791–794. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieper J, van der Heijde D. Review: Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: new definition of an old disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:543–551. doi: 10.1002/art.37803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougados M, Demattei C, van den Berg R, Hoang V, Thevenin F, Reijnierse M, et al. Rate and predisposing factors for sacroiliac joint radiographic progression after two-year follow-up period in recent-onset spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68:1904–1913. doi: 10.1002/art.39666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Listing J, Marker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, Braun J, Sieper J. Rates and predictors of radiographic sacroiliitis progression over 2 years in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1369–1374. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.145995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang R, Gabriel S, Ward M. Progression of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis to ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68:1415–1421. doi: 10.1002/art.39542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiltz U, Baraliakos X, Karakostas P, Igelmann M, Kalthoff L, Klink C, Krause D, Schmitz-Bortz E, Flörecke M, Bollow M, Braun J. Do patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis differ from patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1415–1422. doi: 10.1002/acr.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallis D, Haroon N, Ayearst R, Carty A, Inman R. Ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: part of a common spectrum or distinct diseases? J Rheumatol. 2013;40:2038–2041. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudwaleit M, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, Collantes-Estevez E, Davis J, Dijkmans B, Dougados M, Emery P, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Inman R, Khan MA, Leirisalo-Repo M, van der Linden S, Maksymowych WP, Mielants H, Olivieri I, Sturrock R, de Vlam K, Sieper J. The development of assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheuam Dis. 2009;68:770–776. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malaviya AN, Kalyani A, Rawat R, Bhushan S. Comparison of patients with ankylosing (AS) and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) from a single rheumatology clinic in New Delhi. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18:736–741. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song IH, Weiss A, Hermann KG, Haibel H, Althoff CE, Poddubnny D, et al. Similar response rates in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis after 1 year of treatment with etanercept: results from the ESTER trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:823–825. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real world rheumatologist and patient behavior across countries: disease-specific programmes- a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3063–3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:ii1–ii44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, Cieza A, Stucki G, Khan MA, Maksymowych WP, Marzo-Ortega H, Reveille J, Stebbings S, Bostan C, Braun J. Development of a health index in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (ASAS HI): final result of a global initiative based on the ICF guided by ASAS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:830–835. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Packham J, Jordan K, Haywood K, Garratt A, Healy E. Evaluation of Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life questionnaire: responsiveness of a new patient-reported outcome. Rheumatology. 2012;51:707–714. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szende AOM, Devlin N. EQ-5D value sets: inventory, comparative review and user guide. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, Kupper H, van der Heijde D. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:812–819. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciurea A, Scherer A, Exer P, Bernhard J, Dudler J, Beyeler B, Kissling R, Stekhoven D, Rufibach K, Tamborrini G, Weiss B, Müller R, Nissen MJ, Michel BA, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Boonen A, Weber U, on behalf of the Rheumatologists of the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Program for Axial Spondyloarthritis Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition in radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results from a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3096–3106. doi: 10.1002/art.38140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Karki C, Palmer JB, Liu M, Pandurengan R, Park Y, et al. Characterization of patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in the US-Based Corrona Registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:1661–1670. doi: 10.1002/acr.23534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arévalo M, Masmitjà JG, Moreno M, Calvet J, Orellana C, Ruiz D, et al. Influence of HLA-B27 on the ankylosing spondylitis phenotype: results from the REGISPONSER database. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:1724–1727. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1724-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machado P, Landewe R, Braun J, Hermann KA, Baker D, van der Heijde D. Both structural damage and inflammation of the spine contribute to impairment of spinal mobility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1465–1470. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poddubnyy D, Sieper J. Similarities and differences between nonradiographic and radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a clinical, epidemiological and therapeutic assessment. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:377–383. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieper J, Landewe R, Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Mease PJ, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol over ninety-six weeks in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a phase III randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67:668–677. doi: 10.1002/art.38973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landewe R, Braun J, Deodhar A, Dougados M, Makymowych WP, Mease PJ, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:39–47. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]