Abstract

Adenomyosis is associated with dysmenorrhea, infertility, and lesional fibrosis. The pathogenesis of adenomyosis is still unclear. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) plays important roles in pathological activities like tumor metastasis and endometriosis. Our objective was to investigate the expression and localization of PAI-1 in eutopic and ectopic endometrium with adenomyosis and in endometrium without adenomyosis. We also sought to determine the relationship between PAI-1 immunoreactivity and the severity of dysmenorrhea and the extent of lesional fibrosis in adenomyosis. PAI-1 expression was significantly higher in the ectopic endometrium of patients with adenomyosis than in both the eutopic endometrium of patients with adenomyosis and the endometrium of controls. Ectopic PAI-1 expression correlated positively with dysmenorrhea visual analog scale (VAS) scores and the extent of lesional fibrosis in adenomyosis. High PAI-1 expression increased the likelihood of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis. These results suggest that PAI-1 is involved in the adenomyosis-associated dysmenorrhea and lesional fibrosis, which provide a potential target in treating symptomatic adenomyosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43032-021-00513-6.

Keywords: Adenomyosis, PAI-1, Immunohistochemistry, Dysmenorrhea, Fibrosis

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a common chronic gynecological disorder accompanied by progressive dysmenorrhea and infertility [1, 2]. It is characterized by invasion of the glandular epithelium and stroma into the uterine myometrium, together with hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the myometrium [3]. At present, the pathogenesis of adenomyosis mainly includes the theory of invagination and metaplasia [4]. It has been reported that inflammation and innervation might be the key factors involved in the pathogenic mechanism of adenomyosis-related dysmenorrhea [5]. Adenomyosis impairs fertility mainly through reduced endometrial receptivity [6], which is influenced by uterine anatomical distortions due to adhesions and fibrosis [7, 8]. Therefore, the identification of elements involved in adenomyosis-associated dysmenorrhea and fibrosis is critical.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), encoded by the SERPINE1 gene, belongs to the family of serine protease inhibitors and is essential for reacting rapidly with both urokinase-type and tissue-type plasminogen activators (uPA and tPA, respectively) [9]. PAI-1 participates in physiological or pathological activities such as cell adhesion, migration, and invasion and even in tumor formation and metastasis [10]. Studies have reported that PAI-1 might promote angiogenesis and stabilize neovascularization [11, 12], and elevated PAI-1 levels contribute to inflammation and excessive matrix deposition [13]. Researchers recently reported that PAI-1 is highly expressed in endometriosis [14]. Although endometriosis and adenomyosis are proximate in histomorphology and ectopic growth of the endometrium, their clinical characteristics and pathogenesis are not identical [15]. Thus, the expression and cellular localization of PAI-1 in adenomyosis and its associated uterine biology remain to be elucidated.

To investigate the expression and localization of PAI-1 in endometria with and without adenomyosis and to determine the relationship between PAI-1 immunoreactivity and the severity of dysmenorrhea and the extent of lesional fibrosis in adenomyosis, immunohistochemistry experiment, Masson’s trichrome staining, and correlation analysis between adenomyotic PAI-1 expression and the severity of dysmenorrhea and the extent of lesional fibrosis were performed. Furthermore, we evaluated the expression of PAI-1 with the inverse probability weighting (IPW) method to identify its potential role in the risk of the severity of dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

All samples were obtained from our hospital between 2018 and 2019, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and routinely processed for paraffin embedding. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Peace Maternal and Child Health Hospital (NO. GKLW 2017-71). Forty-five specimens of the ectopic endometrium and homologous eutopic endometrium of patients with pathologically confirmed adenomyosis were collected after hysterectomy or adenomyomectomy as the study group. For controls, endometrial samples were collected from patients who underwent laparoscopy with cervical carcinoma in situ or benign ovarian cysts. For patients with cervical carcinoma in situ, the endometria were collected through curettage after hysterectomy. For patients with benign ovarian cysts, we aspirated the endometrium with a Pipelle catheter from parous patients who did not need fertility and had fully informed consent [16]. Patients in the control group were without any clinical history, signs, gynecologic, and sonographic examinations of adenomyosis, endometriosis, and myoma in the preoperative state, laparoscopic examination, and histology after the surgery [17].

The adenomyosis and control groups were both required to fulfill the same criteria as follows: childbearing women who had regular menstruation (lengths varied from 21 to 35 days). The study flow chart is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The visual analog scale (VAS) was used to evaluate the dysmenorrhea of patients [18]. According to whether changing sanitary pads <3, between 3 and 6 or >6 times per day, the amount of menses during menstruation was grouped into 3 classes: light, moderate, and heavy [17].

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were used for immunohistochemistry. Serial 4-μm sections were obtained from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, with the first resultant slide stained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to confirm pathologic diagnosis and the subsequent slides stained for PAI-1. Adenomyosis was defined by the ectopic endometrial glands and stroma at least one lower-power field of view (approximately 2–3 mm) away from the endometrial-myometrial junction [19]. Sections were rehydrated through graded alcohol and rinsed in distilled water. Antigen retrieval was conducted by microwave heating in citric saline for 15 min. Then, H2O2 and goat serum (10%) were used to deactivate endogenous peroxidase and block nonspecific binding, respectively. After that, samples were incubated with a PAI-1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (bs-6562R, Bioss, China, dilution 1:400) in a wet box at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody. PBS was used as a negative control. DAB and hematoxylin were used to stain the sections. A series of 3 to 5 random views were captured by microscopy (Leica, DM2000). The number and intensity of positive cells were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) to evaluate the mean optical density (MOD), as reported previously [5, 20]. Briefly, the immunohistochemistry parameters measured in the view included the following: (a) integrated optical density (IOD); (b) total stained area; and (c) MOD, which was defined as MOD = IOD/S, equivalent to the staining levels in all positive cells. The immunoreactivity level of PAI-1 staining referred to the MOD values.

Masson’s Trichrome Staining

Masson’s trichrome staining was used to detect collagen fibers in tissue samples. Tissue sections (4 μm, paraffin embedded) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in a graded alcohol series, and then soaked in Bouin’s solution at 37 °C for 2 h. Bouin’s solution was made with 75 mL of saturated picric acid, 25 mL of 10% formalin solution (v/v), and 5 mL of acetic acid. Tissue sections were stained using a Masson’s trichrome staining kit (RIBIOLOGY, Shanghai, China). The areas of the collagen fiber layer stained blue relative to the entire portion of the ectopic implants were calculated by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 and taken as the extent of lesional fibrosis as previously reported [21].

Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as the mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous data according to whether the values were distributed normally assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportions for categorical variables when appropriate. The comparison of distributions of continuous variables between two groups was made using Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, while distributions of continuous variables among three or more groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis test. When both variables were continuous or at least one variable was ordinal, we used Pearson’s or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to evaluate correlations between them.

To assess the impact of the MOD value of PAI-1 on the severity of dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis, we calculated the odds ratio (OR, 95% CI) by binary logistic regression separately [22]. The interaction of the PAI-1 MOD value and extent of lesional fibrosis was evaluated. IPW, designed to minimize confounding in observational studies, is a statistical method widely applied in epidemiological studies [23] and has been used in IVF studies [24, 25]. In this study, we used the IPW method to better estimate the risk of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea among women with higher PAI-1 expression. All analyses were performed with R statistical software version 3.6.2 (packages MatchIt, reportReg, MASS). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic Data

The characteristics of the adenomyosis and control groups and the statistical significance of the difference in these characteristics between the two groups are listed in Table 1. Eighty-five women were included in this study: 45 with adenomyosis (adenomyosis group) and 40 without adenomyosis (control group). The adenomyosis and control groups were comparable in age and menstrual phase, yet women in the adenomyosis group tended to have more pregnancies (P=0.043). It seems that the severity of dysmenorrhea in the adenomyosis group was more severe than that in the control group. Among the 45 patients with adenomyosis, 7 (15.6%), 13 (28.9%), 10 (22.2%), and 15 (33.3%) complained of having none, mild, moderate, and severe dysmenorrhea, respectively, and patients in the adenomyosis group had a higher median VAS score than patients in the control group (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of women in the adenomyosis and control groups and significant differences between the two groups

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 40) | Adenomyosis group (n = 45) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; median [IQR]) | 45 (7) | 45 (6) | 0.301 |

| Menstrual phase | |||

| Proliferative | 24 (60.0%) | 23 (51.1%) | 0.411 |

| Secretory | 16 (40.0%) | 22 (48.9%) | |

| Gravidity | |||

| 0 | 5 (12.5%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.043 |

| 1 | 10 (25.0%) | 3 (6.7%) | |

| 2 | 12 (30.0%) | 18 (40.0%) | |

| ≥3 | 13 (32.5%) | 22 (48.9%) | |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 5 (12.5%) | 5 (11.1%) | 0.346 |

| 1 | 32 (80.0%) | 36 (80.0%) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (8.9%) | |

| 3 | 2 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Severity of dysmenorrhea | |||

| None | 29 (72.5%) | 7 (15.6%) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 11 (27.5%) | 13 (28.9%) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (22.2%) | |

| Severe | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (33.3%) | |

| VAS score for dysmenorrhea (median [IQR]) | 0 (1) | 5 (7) | <0.001 |

| Amount of menses | |||

| Light | 18 (45.0%) | 20 (44.4%) | 0.788 |

| Moderate | 11 (27.5%) | 10 (22.2%) | |

| Heavy | 11 (27.5%) | 15 (33.3%) | |

Data are presented as the median (IQR) or number (percentage)

VAS means visual analog scale; IQR means interquartile range

PAI-1 Expression Levels in the Control Endometrium, Eutopic Endometrium, and Ectopic Lesions

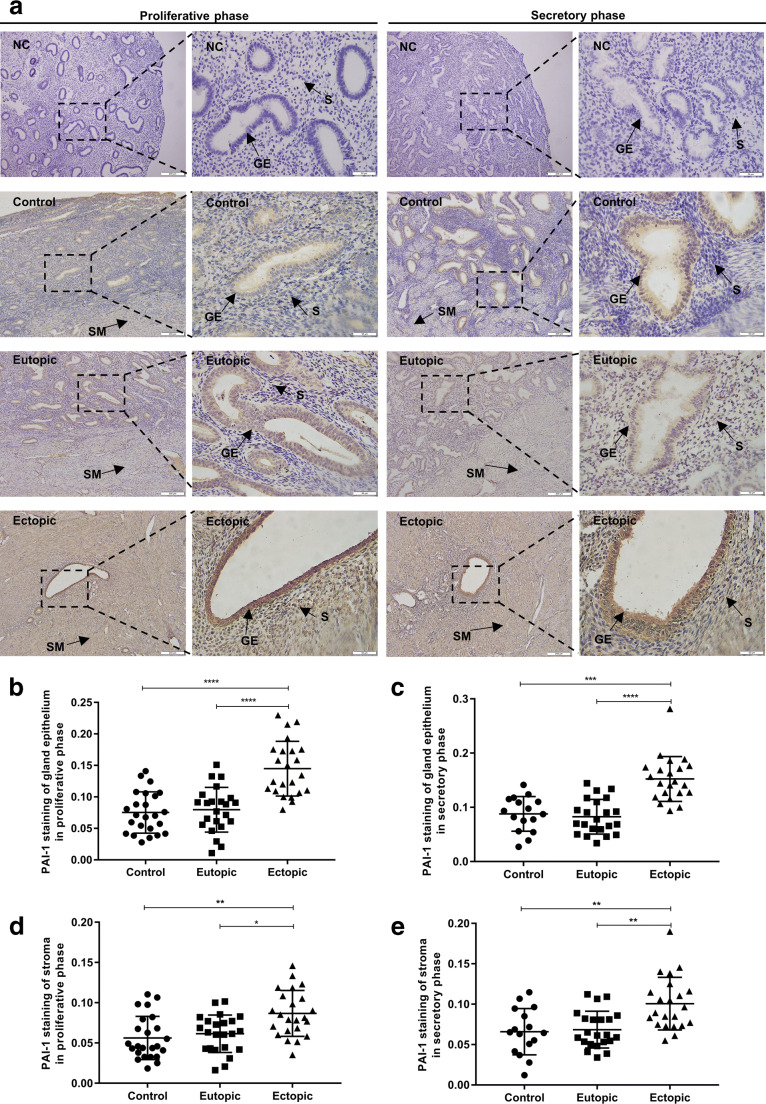

PAI-1 was stained throughout the uterine tissue, not only in the endometrium but also in the myometrium and vessels. PAI-1 immunoreactivity was more intense in the glandular epithelium than in the stroma, and intense PAI-1 staining was found mainly in the membranes and cytoplasms of glandular epithelial cells in the ectopic endometrium (Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for PAI-1. a Representative photomicrographs of the immunohistochemical analysis of PAI-1 in ectopic and paired eutopic endometria with adenomyosis and control endometrium without adenomyosis. Black arrows indicate the localization of the glandular epithelium (GE), stroma (S), and smooth muscle (SM). b and c Quantitative analysis of the MOD values of PAI-1 immunoreactivity in the glandular epithelium among control, eutopic, and ectopic endometria in the proliferative phase and secretory phase, respectively. d and e Quantitative analysis of the MOD values of PAI-1 immunoreactivity in the stroma among control, eutopic, and ectopic endometria in the proliferative phase and secretory phase, respectively. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. NC, negative control; GE, glandular epithelium; S, stroma; SM, smooth muscle

The MOD value of PAI-1 staining of the glandular epithelium in the ectopic endometrium with adenomyosis was significantly stronger than that in the eutopic endometrium with adenomyosis and the normal endometrium without adenomyosis (for the proliferative phase, both 푃 < 0.0001; for the secretory phase, 푃<0.0001 and 푃=0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1b and c). Regarding the endometrial stroma, we observed a similar pattern: PAI-1 expression in the ectopic stroma was also higher than that in the eutopic and control endometria (for the proliferative phase, 푃=0.0235 and 푃=0.0014, respectively; for the secretory phase, 푃=0.0011 and 푃=0.0012, respectively), but such an increase in the stroma was not as obvious as in the glands (Fig. 1d and e). Variation between the proliferative phase and secretory phase of PAI-1 immunoreactivity was not observed in the control, eutopic, or ectopic endometrium or in the glandular epithelium or stroma (for the control endometrium, P=0.2320 and P=0.2354, respectively; for the eutopic endometrium, P=0.7241 and P=0.3138, respectively; for the ectopic endometrium, P=0.5360 and P=0.1342, respectively) (Supplemental Figure. 2).

Associations Between PAI-1 Immunohistochemistry and the Extent of Lesional Fibrosis or the Severity of Dysmenorrhea in the Adenomyosis Group

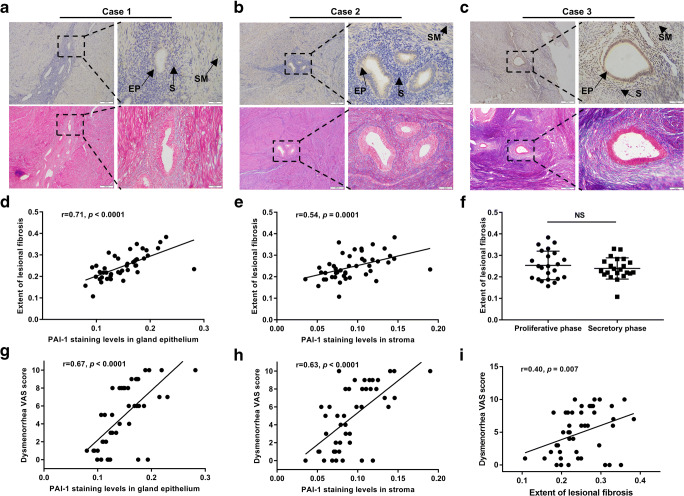

Representative images of Masson’s staining corresponding to specimens with different intensities of PAI-1 staining are presented (Fig. 2a–c). Correlation analysis showed that the extent of lesional fibrosis positively correlated with the ectopic staining levels of PAI-1 (r=0.71, P<0.0001; r=0.54, P=0.0001, respectively, in the glandular endometrium and stroma) (Fig. 2d and e). A difference in the extent of fibrosis between the proliferative phase and secretory phase was not observed in the ectopic endometrium (P=0.4199) (Fig. 2f). In addition, increased ectopic PAI-1 staining levels in the glandular epithelium and stroma were significantly correlated with increased dysmenorrhea (r=0.67, P<0.0001; r=0.63, P<0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 2g and h). Nevertheless, an association between eutopic PAI-1 expression and dysmenorrhea levels had no statistical correlation (r=−0.04, P=0.7778; r=0.22, P=0.1488, respectively). Interestingly, the severity of dysmenorrhea was also slightly correlated with the extent of fibrosis in adenomyotic lesions (r=0.40, P=0.007) (Fig. 2i). In contrast to dysmenorrhea and fibrosis, there was no statistical correlation between ectopic PAI-1 expression and the volume of menstrual flow in the glandular epithelium and stroma (r=0.12, P=0.4389; r=−0.02, P=0.8898, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Associations among lesional PAI-1 immunoreactivity, the severity of dysmenorrhea, and the extent of fibrosis. a–c Masson’s trichrome-stained fibrosis and corresponding PAI-1 immunoreactivity in the biopsy samples derived from three representative cases. Black arrows indicate the localization of the glandular epithelium (GE), stroma (S), and smooth muscle (SM). Correlation of PAI-1 expression levels with the extent of lesional fibrosis in the glandular epithelium (d) and stroma (e); extent of lesional fibrosis between the proliferative phase and secretory phase (f); correlation between PAI-1 expression levels and the severity of dysmenorrhea, as measured by the VAS scores, in the glandular epithelium (g) and stroma (h); correlation of the extent of lesional fibrosis with dysmenorrhea VAS scores (i); the dashed line indicates a linear regression fit of the data. NS, P>0.05. MOD, mean optical density; GE, glandular epithelium; S, stroma; SM, smooth muscle

Effects of Adenomyotic PAI-1 Status and the Severity of Dysmenorrhea in Adenomyosis

To further analyze the associations between PAI-1 MOD values and the severity of dysmenorrhea, patients with adenomyosis were categorized into two groups by the VAS score: absent to mild dysmenorrhea (VAS=0–3 cm) or moderate to severe dysmenorrhea (or VAS=4–10 cm) [22]. Binary logistic regression analysis, which included age, menstrual phase, gravidity, and parity, confirmed that the PAI-1 MOD value in either anatomical compartment was an independent predictor of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea (P=0.002, aOR=1.07, 95% CI=1.22–2.39; P=0.005, aOR=1.64, 95% CI=1.16–2.33, respectively) (Table 2). Furthermore, we divided the PAI-1 MOD values into two groups according to the median MOD value among ectopic endometria with adenomyosis. Binary logistic regression indicated that the group with a higher MOD value had a greater risk of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in the glandular epithelium or stroma, and the risk after stratification was also higher (P=0.002, aOR=48.17, 95% CI=4.17–557.01; P=0.003, aOR=13.64, 95% CI=2.36–78.78). The results were similar, while systematic differences were addressed with the use of the IPW method (Table 2). Moreover, the interaction of the extent of lesional fibrosis and the PAI-1 MOD value in the epithelium or stroma was not significant (Table 2), indicating that the association of the PAI-1 MOD value with moderate-to-severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis is similar in all cases of lesional fibrosis.

Table 2.

Risk of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis by binary logistic regression models according to the PAI-1 MOD value of the ectopic endometrium in patients with adenomyosis (n=45)

| Absent to mild dysmenorrhea vs. moderate to severe dysmenorrhea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| PAI-1 expression in the epitheliumc | 1.62 (1.23–2.15) | 0.001 | 1.071 (1.22–2.39) | 0.002 |

| PAI-1 MOD value < 0.145 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| PAI-1 MOD value ≥ 0.145 | 17.94 (3.88–83.09) | <0.001 | 48.17 (4.17–557.01) | 0.002 |

| IPWb, PAI-1 expression in the epithelium | ||||

| PAI-1 MOD value < 0.145 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| PAI-1 MOD value ≥ 0.145 | 14.48 (5.06–41.46) | <0.001 | 52.09 (8.51–318.47) | <0.001 |

| PAI-1 expression in the stromac | 1.72 (1.22–2.42) | 0.002 | 1.64 (1.16–2.33) | 0.005 |

| PAI-1 MOD value < 0.086 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| PAI-1 MOD value ≥ 0.086 | 10.29 (2.53–41.75) | 0.001 | 13.64 (2.36–78.78) | 0.003 |

| IPWb, PAI-1 expression in the stroma | ||||

| PAI-1 MOD value < 0.086 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| PAI-1 MOD value ≥ 0.086 | 8.33 (3.16–21.99) | <0.001 | 14.23 (4.05–49.97) | <0.001 |

| Fibrosis | ||||

| Fibrosis by PAI-1 in the EP* interaction* | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.970 | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 0.507 |

| Fibrosis by PAI-1 in the ST* interaction* | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.150 | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.234 |

OR means odds ratio; PAI-1 means plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; EP means epithelium; ST means stroma

aOR adjusted for age, menstrual phase, gravidity, and parity

bData weighted by the inverse of the probability of age, menstrual phase, gravidity, and parity

cData are shown as the risk of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis for each hundred numerical increases in the PAI-1 MOD value

Discussion

Several studies have revealed that PAI-1 is dysregulated in numerous pathological states, such as metabolic syndrome, vascular diseases, fibrosis, and different kinds of cancer [26]. In a recent study, endometriotic PAI-1 expression in deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) was significantly higher than that in the eutopic endometrium [14]. Our study illustrated high PAI-1 expression in the ectopic endometrium with adenomyosis for the first time, and its expression is not regulated by the menstrual cycle. The increase in PAI-1 expression in the ectopic endometrium might contribute to limiting the invasive potential and proteolytic activity of the ectopic endometrium in adenomyosis, contributing to the deposition of fibrin and extracellular matrix components and finally forming regional lesions in the myometrium, which was similarly reported in advanced stages of endometriosis [27, 28]. Combined with our previous results of the higher SERPINE1 mRNA level in adenomyosis [29], the increasing levels of both mRNA and protein of PAI-1 in the ectopic endometrium suggested the vital role of PAI-1 in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis.

Determining what causes dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis may help identify a therapeutic target for relieving this debilitating symptom. It was noted that elevated tissue factor (TF) immunoreactivity was related to the increased severity of dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis [30], and TF in nonhematopoietic cells induced adipocyte PAI-1 expression, indicating the regulation of PAI-1 by TF signaling [31]. In addition, Alotaibi et al. illustrated that PAI-1 expression in endometriosis was associated with dysmenorrhea by promoting inflammation [32]. Our results showed that increased PAI-1 expression in the ectopic endometrium was significantly associated with more severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis, which may indicate that PAI-1 could be a vital therapeutic target for adenomyosis-associated dysmenorrhea.

The profibrotic nature of lesions was investigated in recent studies of endometriosis [33]. Several factors may contribute to fibrosis in endometriosis: high expression levels of α-SMA and ADRB2 positively correlate with more extensive fibrosis, while E-cadherin expression levels negatively correlate with the fibrotic content [5]. Nonetheless, few molecules have been examined to explore their correlation with the extent of lesional fibrosis in adenomyotic lesions. To the best of our knowledge, PAI-1 regulates fibrinolytic activity, wound healing, and matrix remodeling at physiological levels, but in diseases, PAI-1 could be caused by some cytokines and thus result in tissue fibrosis [13]. Multiple reports have reflected the profibrotic role of PAI-1 in the lung, liver, and kidney [34]. Likewise, our finding that PAI-1 expression in the ectopic endometrium was positively correlated with the extent of lesional fibrosis first revealed a molecule that may be associated with fibrosis of the adenomyotic lesion in adenomyosis.

Although the research has reported that endometrial PAI-1 is significantly high in patients with essential menorrhagia in the menstrual phase [35], we found no statistical correlation between ectopic PAI-1 expression and the amount of menses in patients with adenomyosis, regardless of in proliferative or secretory phases.

We further revealed the expression of PAI-1 in different cell types, including glandular epithelial and stromal cells of the endometrium. In addition, we treated PAI-1 expression as an independent variable for moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis by binary logistic regression. One limitation is that the study was cross-sectional, and the influence of other variables on the results could not be excluded; therefore, we used the IPW statistical method to adjust for confounding factors.

In summary, this study initially revealed significantly high PAI-1 expression in the ectopic endometrium and its positive correlation with the severity of dysmenorrhea and the extent of lesional fibrosis in adenomyosis. The MOD value of adenomyotic PAI-1 expression was used to evaluate moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis. These findings suggest that PAI-1 could be mediated in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis and its associated dysmenorrhea and lesional fibrosis; thus, it might be a potential target in treating symptomatic adenomyosis.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 171 kb)

Author Contribution

Bingxin Yang, Nihao Gu, and Shu Shi contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (NO. 2020YFC2002804), Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (NO. shslczdzk01802), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 81771551, 81901536, and 81701402), the Shanghai Chinese Traditional and Western Medicine Clinical Collaboration Pilot Construction Project (NO. ZXYXZ-201905), the Research Program of International Peace Maternal and Child Health Hospital (NO. CR2018WX06 and YN201914), and the Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project (NO. SHDC12017123).

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Peace Maternal and Child Health Hospital (NO. GKLW 2017-71).

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bingxin Yang, Email: ybx1995@sjtu.edu.cn.

Nihao Gu, Email: marcogoo@sjtu.edu.cn.

Shu Shi, Email: wendyshishu@163.com.

Chen Zhang, Email: 13916681426@163.com.

Lan Chen, Email: lanzchen@163.com.

Jing Ouyang, Email: ouyangjing126@126.com.

Yu Lin, Email: linyu089@163.com.

Feng Sun, Email: sunfeng0711@126.com.

Hong Xu, Email: xuhong1558@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Maheshwari A, Gurunath S, Fatima F, Bhattacharya S. Adenomyosis and subfertility: a systematic review of prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and fertility outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(4):374–392. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo SW, Groothuis PG. Is it time for a paradigm shift in drug research and development in endometriosis/adenomyosis? Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(5):577–598. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benagiano G, Brosens I, Habiba M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):386–402. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans MM. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding D, Wang X, Chen Y, Benagiano G, Liu X, Guo SW. Evidence in support for the progressive nature of ovarian endometriomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(7). 10.1210/clinem/dgaa189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Munro MG. Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(4):629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanbo T, Fedorcsak P. Endometriosis-associated infertility: aspects of pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment options. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):659–667. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo SW. Genesis, genes and epigenetics of endometriosis-associated infertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha H, Oh EY, Lee HB. The role of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in renal and cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(4):203–211. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57(1):25–40. doi: 10.1007/s000180050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajou K, Noel A, Gerard RD, Masson V, Brunner N, Holst-Hansen C, et al. Absence of host plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 prevents cancer invasion and vascularization. Nat Med. 1998;4(8):923–928. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407(6801):249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabieian R, Boshtam M, Zareei M, Kouhpayeh S, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 as a regulator of fibrosis. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(1):17–27. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alotaibi FT, Peng B, Klausen C, Lee AF, Abdelkareem AO, Orr NL, Noga H, Bedaiwy MA, Yong PJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression in endometriosis. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo SW. The pathogenesis of adenomyosis vis-a-vis endometriosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2). 10.3390/jcm9020485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Herndon CN, Aghajanova L, Balayan S, Erikson D, Barragan F, Goldfien G, Vo KC, Hawkins S, Giudice LC. Global transcriptome abnormalities of the eutopic endometrium from women with adenomyosis. Reprod Sci. 2016;23(10):1289–1303. doi: 10.1177/1933719116650758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nie J, Liu X, Guo SW. Immunoreactivity of oxytocin receptor and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 and its correlation with dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):346 e1–346 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang X, Yu D, Zou M, Wang L, Xing HR, Wang Z. The effect of exercise on high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment efficacy in uterine fibroids and adenomyosis: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2017;124(Suppl 3):46–52. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munro MG. Classification and reporting systems for adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie J, Lu Y, Liu X, Guo SW. Immunoreactivity of progesterone receptor isoform B, nuclear factor kappaB, and IkappaBalpha in adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):886–889. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan D, Liu X, Guo SW. Neuropeptides substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide accelerate the development and fibrogenesis of endometriosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2698. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39170-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pluchino N, Mamillapalli R, Wenger JM, Ramyead L, Drakopoulos P, Tille JC, Taylor HS. Estrogen receptor-alpha immunoreactivity predicts symptom severity and pain recurrence in deep endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(6):1224–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grool AM, Aglipay M, Momoli F, Meehan WP, 3rd, Freedman SB, Yeates KO, et al. association between early participation in physical activity following acute concussion and persistent postconcussive symptoms in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2504–2514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peuranpaa P, Hautamaki H, Halttunen-Nieminen M, Hyden-Granskog C, Tiitinen A. Low anti-Mullerian hormone level is not a risk factor for early pregnancy loss in IVF/ICSI treatment. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(3):504–515. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Modest AM, Wise LA, Fox MP, Weuve J, Penzias AS, Hacker MR. IVF success corrected for drop-out: use of inverse probability weighting. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(12):2295–2301. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S, Wei X, He J, Tian X, Yuan S, Sun L. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cancer research. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;105:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilabert-Estelles J, Estelles A, Gilabert J, Castello R, Espana F, Falco C, et al. Expression of several components of the plasminogen activator and matrix metalloproteinase systems in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(7):1516–1522. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilabert-Estelles J, Castello R, Gilabert J, Ramon LA, Espana F, Romeu A, et al. Plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitors in endometriosis. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1162–1176. doi: 10.2741/1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang Y, Sun Y, Yang B, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yu T, Huang H, Zhang J, Xu H. Transcriptome sequencing of adenomyosis eutopic endometrium: a new insight into its pathophysiology. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(12):8381–8391. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Nie J, Guo SW. Elevated immunoreactivity to tissue factor and its association with dysmenorrhea severity and the amount of menses in adenomyosis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(2):337–345. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badeanlou L, Furlan-Freguia C, Yang G, Ruf W, Samad F. Tissue factor-protease-activated receptor 2 signaling promotes diet-induced obesity and adipose inflammation. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1490–1497. doi: 10.1038/nm.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Donato N, Montanari G, Benfenati A, Leonardi D, Bertoldo V, Monti G, et al. Prevalence of adenomyosis in women undergoing surgery for endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;181:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigano P, Candiani M, Monno A, Giacomini E, Vercellini P, Somigliana E. Time to redefine endometriosis including its pro-fibrotic nature. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(3):347–352. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flevaris P, Vaughan D. the role of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 in fibrosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017;43(2):169–177. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gleeson NC. Cyclic changes in endometrial tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in women with normal menstruation and essential menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(1):178–183. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 171 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.