Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 900,000 deaths annually. People living with HIV are at a higher risk of developing CVD. We conducted a scoping review guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis. In July 2020, six databases were searched: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Embase, and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, as well as reference lists of relevant studies and key journals. Our review identified 18 studies that addressed nonpharmacological behavioral interventions into the following: physical activity (n = 6), weight loss (n = 2), dietary interventions (n = 1), and multicomponent interventions (n = 9). In the past 10 years, there has been an increased emphasis on nonpharmacological behavioral approaches, including the incorporation of multicomponent interventions, to reduce cardiovascular risk in people living with HIV. The extant literature is limited by underrepresentation of geographic regions and populations that disproportionately experience CVD.

Keywords: behavioral interventions, cardiovascular disease prevention, HIV, scoping review

Antiretroviral therapy has been revolutionary in prolonging the life of persons living with HIV (PLWH), making HIV a manageable chronic condition; however, persons of color remain disproportionately overburdened. Sexual minority men, specifically Blacks and Latinos, account for greater than two thirds of new HIV diagnoses (CDC, 2016). Cardiometabolic changes resulting from HIV and treatment can exacerbate the existing higher rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among this minority population (Finkelstein et al., 2015; Myerson & Glesby, 2019).

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 900,000 deaths annually (Naghavi et al., 2017). PLWH are at a higher risk for developing CVD (Feinstein et al., 2016), and they have a 1.5 to 2 times relative risk of developing CVD at a lower median age when compared with uninfected people (Feinstein et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2018). This risk is multifactorial, including the proatherogenic effects of antiretroviral therapy, such as inducing dyslipidemia, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance (Ballocca et al., 2016; Grinspoon & Carr, 2005); chronic inflammation (Deeks, 2011); genetic predisposition (Wassel et al., 2009; Zilbermint et al., 2019); and suboptimal behavioral/lifestyle factors (Vishnu et al., 2019). Studies using biomarker data found that PLWH with lower CD4+ T-cell counts who showed persistently elevated levels of interleukin-6, an inflammatory marker, had an increased risk for CVD, and increased mortality (Currier, 2018).

A main goal of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020 (White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2015) is to reduce HIV-related health disparities and health inequities, such as CVD, in PLWH. Pharmacological prevention of CVD has been efficacious and focused on the use of statins (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) and aspirin (Maggi et al., 2019). More recently, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force reported that statin therapy may be beneficial as a primary prevention strategy in some adults, with a 10-year CVD risk of less than 10% (Bibbins-Domingo et al., 2016). In addition to medication therapies, screening for CVD risk factors and proven nonpharmacological prevention approaches can be implemented to address the high CVD incidence in PLWH. Behavioral or lifestyle interventions, herein referred to as behavioral interventions, have been used in studies for the prevention of diabetes, obesity, and smoking (Curry et al., 2018; Dunkley et al., 2014; Lancaster & Stead, 2017). Accordingly, CVD prevention should also be premised on associated risk factors and risk-reducing interventions (Stein et al., 2008).

In 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) collected several cardiovascular health metrics into a framework called Life’s Simple 7. The intent of this framework was to create guidelines for cardiovascular health in the general population and address measures that can be taken to enhance prevention of CVD (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010). The seven health metrics are categorized into behaviors: managing blood pressure, controlling cholesterol, reducing blood sugar, getting physically active, healthier eating, weight loss if over-weight, and quitting smoking. These recommendations establish tangible targets to achieve a heart healthy lifestyle (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010).

Studies that address one or more of the Life’s Simple 7 metrics can provide evidence of its effectiveness as a framework for cardiovascular health promotion. For example, a 2015 study examined the association of adherence using Life’s Simple 7 metrics and lifetime risk of heart failure in a cohort of middle-aged adults (range, 45–64 years). Results suggested that higher Life’s Simple 7 scores were negatively associated with heart failure incidence (Folsom et al., 2015).

Given the high CVD risk in PWLH, it is important to consider the heart healthy behaviors addressed by these metrics as the blueprint for nonpharmacological interventions. Although several published systematic reviews have focused on the use of pharmacologic and imaging approaches to capture and/or address CVD risk in PLWH (Bundhun et al., 2017; Feinstein et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2015; Vos et al., 2016), the role of behavioral/lifestyle interventions in preventing CVD in PLWH remains incompletely understood.

We conducted a scoping review to assess the published evidence and examine the types (weight loss, physical activity, dietary, etc.) and characteristics (population, race/ethnicity, age, country, etc.) of nonpharmacological behavioral interventions used to prevent CVD in PLWH. We were specifically interested in studies related to hypertension (HTN) prevention because it is a major risk factor for CVD (Fuchs & Whelton, 2020). We selected a scoping review approach to broadly explore and describe the breadth and depth of existing evidence and any gaps in the literature regardless of study design, types of literature reviewed, or quality of studies included (Aromataris & Munn, 2020; Levac et al., 2010).

Using the population/concept/context framework, the following research question was formulated: “What types of non-pharmacological behavioral interventions exist to prevent CVD in adults living with HIV in the United States and abroad?”

Methods

We conducted a scoping review guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris & Munn, 2020) and reported our findings using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., 2018).

Identifying Relevant Studies

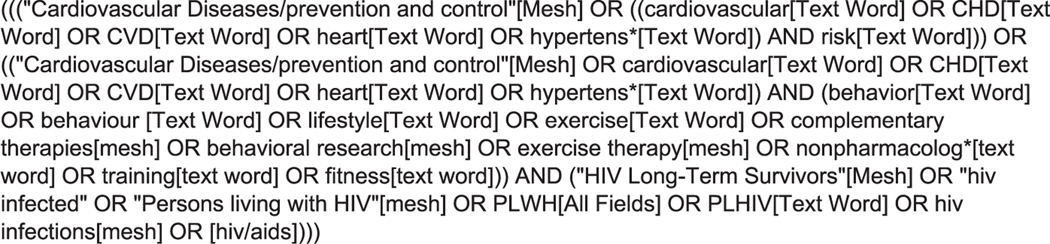

In July 2020, we searched six databases, including PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Embase, and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, as well as the reference lists of relevant studies and the tables of content of key journals. These six databases were selected because of their extensive coverage of social science and health content. Two research librarians specializing in nursing, medicine, and allied health were consulted on developing and refining our search strategy. Search strings were tailored to each database using a combination of keywords and database-specific subject headings where applicable, such as Medical Subject Headings terminology for searching PubMed/MEDLINE. The search strategy for PubMed/MEDLINE can be found in Figure 1. Search strategies were modified and repeated using the appropriate syntax and controlled vocabulary for each specialized database and search interface. Multiple iterations were generated to build a search strategy that would ensure a robust and thorough review of the literature.

Figure 1.

PubMed search strategy.

No restrictions were placed on publication date or geographic location because the researchers were interested in exploring when this body of literature began to emerge and also to explore if there was an associated geographic pattern. This scoping approach allowed the researchers to observe a breadth of literature and identify any topic patterns and/or gaps in the literature. The protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ca2vy).

Study Selection

We were interested in studies of behavioral interventions to prevent CVD in adults living with HIV in the United States and abroad. We defined behavioral interventions as actions designed to induce behavior or lifestyle changes with the intention of preventing illness or promoting health (Anderson et al., 2004). CVD refers to a series of conditions affecting the heart or circulatory system. We focused on the prevention of HTN because it is a predominant risk factor for CVD (Fuchs & Whelton, 2020). To meet the inclusion criteria, articles had to be (a) written in English, (b) published research studies or clinical research protocols, (c) focused on adults living with HIV, and (d) focused on nonpharmacological behavioral/lifestyle interventions to prevent CVD, specifically HTN. We included mixed method, qualitative, quantitative, and clinical trial protocols as part of our study selection. Published literature that did not explicitly state HTN as an outcome, but involved behavioral/lifestyle approaches to prevent HTN, were included. Exclusion criteria were (a) interventions that used a combination of lifestyle and pharmacological management and (b) presentations, editorials, and conference posters.

Charting and Summarizing the Data

Search results were exported from each database and imported into EndNote Reference Manager, a software for managing bibliographies and references. We created separate EndNote groups for each database and removed duplicates. Files were then uploaded into Covidence data management software (https://www.covidence.org) for title, abstract, and article screening. Articles were randomly selected, and the titles and abstracts were discussed and then voted on by the reviewers whether they should be included in the full-text review. Article titles and abstracts were reviewed until there was 80% consensus among the reviewers. Three reviewers (O.M.O., A.H.C., and Y.A.) screened all articles independently and compared results. A separate author (S.R.R.) was consulted to resolve discrepancies and conflicts.

Two reviewers developed the data charting form and independently charted the data using Microsoft Word. Data charting was an iterative process that included distinguishing full-text articles (Table 1) from clinical trial protocols (Table 2). We then abstracted items, such as author, year, sample, age, gender, race/ethnicity, country, study design, intervention, outcome, and key findings (Table 1). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We synthesized our results using the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 as a guide to describe the types of studies that exist using physical activity, weight loss, and healthy diet as behavioral interventions. Our review focused on non-pharmacological behavioral interventions with a special interest in the types of interventions conducted, demographic characteristics of the sample, and the geographic location of the studies. Characterizing these data can outline future directions for nonpharmacological behavioral interventions to prevent CVD in PLWH.

Table 1.

Nonpharmacological Behavioral Interventions: Characteristics of Included Research Articles (N = 11)

| Author, Year, and Sample | Age and Gender | Race/Ethnicity | Country | Design | Intervention | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cade et al., 2010 (n = 50) | 18–70; men and women | African American, White | USA | RCT | 20-week supervised Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga | CVD risk factors, including oral glucose tolerance, lipid/lipoprotein levels, resting blood pressures, body composition, immune and virologic status, and health-related QOL | ↓ resting SBP and DBP; no greater reduction in body weight and fat, lean mass, lipid levels; no improvements in glucose tolerance or overall QOL; improved emotional well-being; no change in immune and virologic status |

| Cioe et al., 2018 (n = 8) | 53 ± 6.6; men and women | White, African American, other; Hispanic/Latino | USA | Qualitative descriptive pilot study | 12-week tailored, goal setting, and physical activity intervention | Perceived risk of CVD, level of physical activity using a pedometer, adoption of heart healthy behaviors | ↑ treatment satisfaction; minimal ↑ in risk perception of CVD; ↑ physical activity at week 8, but ↓ at week 12 to below baseline; 7 of 8 reached 1 goal by week 4 |

| Cutrono et al., 2016 (n = 89) | 48 ± 7; men and women | Non-Hispanic White, African American, Hispanic | USA | Quasiexperiment pre-post test | 3-month aerobic and resistance training | Physical characteristics, non-lipid blood markers, blood lipid profile, and physical fitness variables | ~25% met physical activity recommendations, hsCRP changes non-significant; tin upper and lower-body strength; improved aerobic capacity |

| Dolan et al., 2006 (n = 38) | 43 ± 2; women | White, African American, Hispanic, other | USA | RCT | 16-week supervised home-based aerobic and strength training | Cross-sectional muscle area and muscle attenuation, cardiorespiratory fitness | Significant improvement in aerobic capacity, muscle size and quality; ↓ in muscle adiposity; ↑ in muscular strength |

| Ezema et al., 2014 (n = 30) | 22–63; men and women | African | Nigeria | RCT | 8-week moderate-intensity aerobic exercise | Systolic BP, diastolic BP, VO2 max and CD4+ T cell | Significant ↓ in systolic and diastolic BPs; ↑ CD4+ T cell and VO2 |

| Fitch et al., 2006 (n = 28) | 18–65; men and women | Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, and other | USA | RCT | 6-month intensive dietary modification program | Metabolic syndrome criteria | Improvement in metabolic syndrome parameters (↓ SBP, A1C, lipodystrophy score, caloric intake and ↑ physical activity) |

| Hodges and Holstad, 2013 (n = 76) | 23–68; women | African American and unspecified other | USA | Secondary analysis of RCT | 8-week nurse and health educator- led health promotion program | Weight, BMI, and waist-to-hip ratio | No significant ↓ in anthropometric measurements |

| Jaggers et al., 2013 (n = 68) | 48 ± 10; men and women | African American, White, Other, Hispanic | USA | RCT | 9-month home-based physical activity program and telephone coaching | Physical activity and CVD risk factors | Study in final stages of data collection |

| MacArthur et al., 1993 (n = 6) | 38.8 ± 4.8; men and women | Not specified | USA | Pilot Study | 24-week low or high-intensity exercise training | Cardiopulmonary effects CD4+ T cell, and perceived sense of well-being | ↑ VO2 max and oxygen pulse; nonsignificant ↑ in overall well-being |

| Webel et al., 2018 (n = 107) | 52.3 ± 7.39; men, women, and transgender | African American, White | USA | RCT | 6-month in-person lifestyle behavior intervention | Time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and Healthy Eating Index | No effect on physical activity and no improvement on Healthy Eating Index |

| Wing et al., 2019 (n = 37) | 49.9 ± 8.8; men and women | Caucasian, African American, Native American, Hispanic, other | USA | RCT | 12-week internet weight-loss intervention | Dietary changes, physical activity, behavioral strategies, and cardiometabolic parameters | ↑ weight loss, ↑ use of healthy weight control strategies, ↓ caloric intake ↑ physical activity |

Note. A1C = hemoglobin A1c; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; QOL = quality of life; RCT = randomized control trial; SBP = systolic blood pressure; VO2 = maximum oxygen uptake.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Research Protocols for Nonpharmacological Behavioral Interventions (N = 7)

| Author, Year, and Sample | Age and Gender | Country | Design | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Côté et al., 2015 (n = 750) | 18+; gender not specified | Canada | RCT | 6-month web-based health promotion and behavior change intervention | Adoption of health behaviors (smoking cessation, physical activity, or healthy eating) |

| Mitrani, 2019 (n = 18) | 50+; men | USA | Feasibility Study | 16-week multicomponent, social and physical activity intervention | Feasibility of recruitment, retention rate, and acceptability of intervention |

| Nieuwkerk, 2014 (n = 250) | 181; gender not specified | The Netherlands | RCT | 12-month CVD risk communication tool intervention | 5-year absolute CVD-risk score |

| Okeke, 2019 (n = 50) | 40–75; open to all genders | USA | RCT | 24-week case manager/social worker-delivered telephone intervention | Change in ambulatory SBP and change in fasting LDL-c levels |

| Saumoy, 2012 (n = 54) | 18+; men and women | Spain | RCT | 55-month intensive, multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention delivered by preventative health physician and dietician | Changes in lipid parameters and Framingham score |

| Stradling et al., 2016 (n = 60) | Adults; gender not specified | United Kingdom | RCT | 12-month dietary intervention | Feasibility and acceptability of trial procedures for recruitment, retention, data completion, and the intervention |

| Waldrop-Valverde, 2016 (n = 115) | 50–75; open to all genders | USA | RCT | 12-week in-home walking program | Improvement in memory, concentration thinking abilities, physical function, and quality of life |

Note. CVD = cardiovascular disease; LDL-c = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; RCT = randomized control trial; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Results

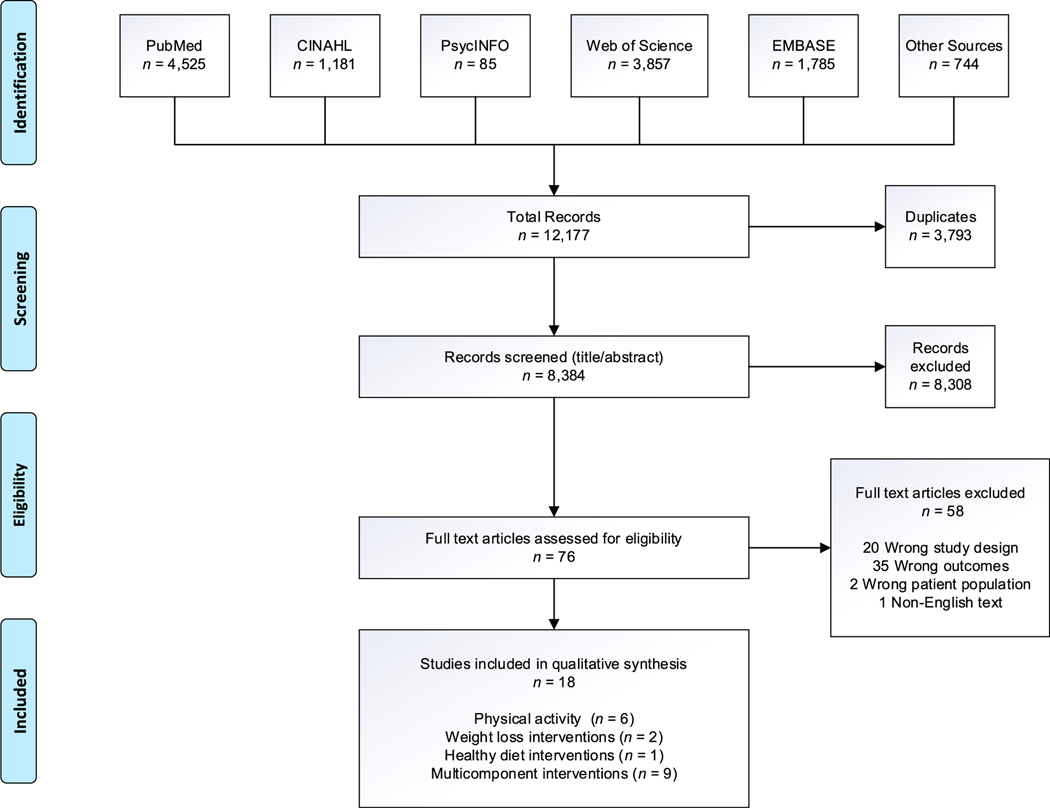

The search strategy identified a total of 12,177 articles. The database search yielded 11,443 while 744 articles were identified from other sources including reference lists, hand searches, and grey literature sources. After removing duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 8,384 articles. After review, 8,308 articles were excluded and 76 were included for a full-text review. Fifty-eight articles were excluded after full-text review. Eighteen studies, including hand-searched articles, were included in the qualitative synthesis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension flow diagram is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension diagram. Note. CINAHL 5 Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Behavioral Intervention Study Characteristics

The age range of participants in behavioral interventions was 18–75 years. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 750. Study samples were composed of men and women (n = 9), only women (n = 2), only men (n = 1), men, women, and transgender participants (n = 1), gender unspecified (n = 3), and open to all genders (n = 2). With the exception of the international study, most of the 11 published studies were diverse with regard to race (African Americans, Whites, Native Americans and other) and ethnicity (Hispanics and non-Hispanics). Approximately 82% of studies included African Americans (n = 9); approximately 73% (n = 8) included Whites; approximately 9% (n = 1) included Native Americans; approximately 55% (n = 6) included races labeled as “other”; approximately 9% (n = 1) were unspecified, and approximately 55% (n = 6) included Hispanics. The predominant study design used was the randomized control trial (RCT; n = 13). The other five studies each used a different design (qualitative descriptive, quasi-experiment, secondary analysis of an RCT, pilot study, and a feasibility study). The earliest behavioral intervention in this review was conducted more than two decades ago in 1993. Multicomponent behavioral interventions started to emerge in the literature in 2006. The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (Figure 3), specifically, in the northeast (n = 4), the southeast (n = 6), and the midwest (n = 3). No studies were conducted in the west and southwest. A total of five studies were conducted abroad in Africa, Canada, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

Figure 3.

Map of nonpharmacological behavioral interventions in the United States.

Behavioral Intervention Characteristics

Behavioral interventions were grouped into the following categories using the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 metrics: physical activity (n = 6), weight loss (n = 2), and dietary interventions (n = 1). Some studies were multicomponent, incorporating more than one intervention or a component that did not fall under any of the Simple 7 metrics (n = 9). Of the 18 studies included, the most common behavioral interventions reported were multicomponent interventions. One study was a nurse-led intervention to improve CVD risk perception and adoption of heart healthy behaviors, specifically, physical activity (Cioe et al., 2018). A second multicomponent study was a 9-month home-based exercise program that included physical activity and telephone coaching (Jaggers et al., 2013). Another study provided a visual graphic presentation of participant-calculated 5-year CVD risk in a 12-month nurse-led multifactorial CVD risk factor counseling intervention (Nieuwkerk, 2014). One study incorporated a 16-week multicomponent, health promotion intervention that used social and physical activity (Mitrani, 2019). Another study will have participants choose one of three different metrics (smoking cessation, physical activity, and healthy eating) they wish to adopt in a web-based tailored intervention (Côté et al., 2015).

Many of the multicomponent interventions combined physical activity and healthy dieting. These included (a) a 6-month intervention with weekly one-on-one dietary counseling sessions (Fitch et al., 2006), (b) a case manager/social worker-led, telephone-based educational curriculum to improve CVD outcomes (Okeke, 2019), (c) an intensive lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk (Saumoy, 2012), and (d) six in-person weekly group sessions focusing on improving lifestyle behaviors (Webel et al., 2018).

The second most common type of CVD prevention behavioral interventions were physical activity interventions. These included (a) a 20-week Ashtanga yoga intervention (Cade et al., 2010), (b) an 8-week exercise group program (Ezema et al., 2014), (c) a 12-month community exercise program (Cutrono et al., 2016), (d) a 12-week walk-at-home intervention (Waldrop-Valverde, 2016), (e) a 16-week supervised home exercise program (Dolan et al., 2006), and (f) a 24-week low- and high-intensity exercise program (MacArthur et al., 1993).

Weight loss interventions included a health promotion educational program on improving cardiovascular risk factors of weight, body mass index, and waist-to-hip ratio (Hodges & Holstad, 2013) and an internet behavioral weight loss program (Wing et al., 2019). Dietary intervention focused on testing a Mediterranean diet with cholesterol-lowering foods (Stradling et al., 2016).

Discussion

We mapped the literature to understand the types of behavioral/lifestyle interventions used to prevent HTN in PLWH. We accomplished this by assessing the sampled participants’ characteristics, the types of interventions, and the geographic regions. Interest in the study of behavioral interventions to prevent CVD in PLWH has increased since 2013. The number of behavioral interventions in this area has grown significantly, with 13 studies published over the past 7 years. We believe that this is due to an increase in initiatives, such as Life’s Simple 7, to mitigate CVD risk.

A secondary data analysis, which was included in our synthesis (Hodges & Holstad, 2013), used data from a health promotion control group that was part of a primary data collection study tangentially related to PLWH. That study was a clinical trial that explored the efficacy of a motivational group to promote antiretroviral therapy adherence and risk reduction behaviors in a sample of adult women living with HIV (Holstad et al., 2011). As part of the primary study on antiretroviral adherence, they included a health promotion control group. The control group consisted of eight group sessions to promote healthy nutrition, exercise, management of stress, and women’s health (Hodges & Holstad, 2013). The health promotion control group data, from the primary study, were analyzed and reported as a secondary data analysis (Hodges & Holstad, 2013), which we included in our data synthesis.

Figure 3 highlights the behavioral interventions identified during this scoping review and their geographic location in the United States. Findings from our review suggested that the majority of CVD prevention behavioral interventions were conducted in the southeast, midwest, and northeast regions of the United States. A systematic analysis of CVD burden revealed that the U.S. states with the highest prevalence were Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia (Roth et al., 2018). The causes of high CVD burden in those states included poor diet, elevated systolic blood pressure, elevated lipid and glucose levels, obesity, tobacco use, and decreased physical activity (Roth et al., 2018). Our review identified 18 studies that addressed nonpharmacological behavioral CVD prevention in PLWH, most of which were located in the southeastern United States; however, based on our findings, the published behavioral intervention studies underrepresent geographic regions and populations experiencing high CVD disparities.

Regular physical activity can improve inflammatory response and cardiometabolic health in PLWH (d’Ettorre et al., 2014; Feinstein et al., 2019; Jaggers et al., 2014). The benefits of physical activity are numerous, and a growing body of research suggests that regular physical activity decreases all-cause mortality by increasing cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal fitness, flexibility, balance, and speed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). It also improves brain health, including cognition and sleep, and can prevent anxiety and depression (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association contend that consuming a diet rich in lean protein sources, fruits, legumes, vegetables, and whole grains is an optimal preventative measure to reduce CVD (Arnett et al., 2019). Reducing modifiable risk factors (BMI, tobacco use, diet, blood glucose, and blood pressure) is necessary and is in alignment with top health indicators to mitigate the inherent complications associated with CVD in PLWH (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2016).

Forty-six percent of all adults in the United States have CVD, with HTN accounting for 10.5% of all CVD-related deaths (Virani et al., 2020), and current evidence points to an increasing number of younger adults (e.g., ages 18–30 years) developing comorbid conditions (Fox et al., 2013). Comorbid conditions are affecting adults at an earlier age, and the incidence of HIV in young adult populations increases the risk of HIV-related conditions. Medication therapy as a focus of prevention has been efficacious in preventing and managing CVD; however, the abundance of research surrounding pharmacological therapy alone has not sufficiently reduced the population- and region-related health disparities in the incidence of CVD among PLWH. By incorporating AHA’s Simple 7 (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010) metrics for sustained cardiovascular health into lifestyle, CVD incidence and premature deaths can be reduced (Sanchez, 2018). There is an urgent need for larger scale behavioral clinical trials on CVD prevention in PLWH. These studies are necessary to reach an increasing number of early onset comorbidities among the younger adult population, in addition to the adult and older adult populations. Such studies can also inform effective strategies for behavioral prevention and management.

By conducting a scoping review using an appropriate methodological framework (Aromataris & Munn, 2020), we were able to assess the size and scope of existing literature (Grant & Booth, 2009) related to nonpharmacological behavioral interventions for preventing CVD in PLWH. Although broad in scope, this type of review shares several rigor characteristics with a systematic review. Our approach toward search strategy, collection, and preferred reporting demonstrates transparency and reproducibility of findings. Additionally, the research librarians brought essential value to the scoping review methodology. Their expertise in scoping review research question formulation, comprehensiveness of search strategy, and reporting guidelines (Morris et al., 2016) resulted in a very thorough review.

Because we did not restrict our search by geographic location, we were able to include international studies focused on behavioral interventions for CVD prevention in Africa, Canada, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Pursuant to our research question and purview of a scoping review, these international studies from five different countries were identified. As such, descriptive data are provided for these five studies, but the discussion focused on the studies conducted in the United States.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our review. Our selection of the search terms, although extensive, may not have identified some relevant studies. Scoping reviews also hold potential for bias due to their lack of rigor when compared with systematic reviews. Furthermore, there is the potential that the scoping review did not capture current, nonpharmacological, behavioral interventions that are currently active and have not yet been published and are not documented as a clinical trial protocol. Finally, scoping reviews do not include a quality assessment because of their exploratory, descriptive design, and focus on the existence, not the quality, of evidence.

Conclusions

By conducting a scoping review, we explored the types (physical activity, dietary, weight loss, etc.) and study characteristics (age, gender, location, etc.) of nonpharmacological behavioral studies that focused on the prevention of CVD, specifically HTN in PLWH. Most of the studies employed a rigorous study design, the RCT. Based on the publication dates, most studies were conducted within the past 7 years. This appears to indicate that prior to a decade ago, a focus on nonpharmacological approaches had not been often considered, and now, it has become a viable option to examine. More researchers used multicomponent interventions as a means to alleviate cardiovascular risk in PLWH instead of choosing a single intervention.

Although most of the U.S. studies were conducted in the southeast, where great CVD burden exists, our findings suggest that there is a lack of behavioral interventions representing all the geographic regions and populations experiencing high CVD-risk disparities. Future research should focus on expanding the representation and geographic location of large-scale non-pharmacological behavioral CVD prevention interventions for PLWH.

Key Considerations.

Persons living with HIV have a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of developing CVD.

Preventative behavioral interventions are needed to address lifestyle-based modifiable CVD risk factors.

Multicomponent interventions may be beneficial in future studies that look to reduce CVD-risk in PLWH.

There is an urgent need to broaden the representation and geographic locations of large-scale, nonpharmacological, behavioral CVD prevention interventions for PLWH.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by LEveraging A viRtual eNvironment (LEARN) to Enhance Prevention of HIV-related Comorbidities in at-risk Minority MSM (NIH/NHLBI K01HL145580; PI: Ramos) and Research Education Institute for Diverse Scholars (REIDS; NIH/NIMH R25MH087217; PI: Kershaw). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

As with all peer reviewed manuscripts published in JANAC, this article was reviewed by at least two impartial reviewers in a double-blind review process. One of JANAC’s associate editors handled the review process for the paper, and the Editorial Board member, S. Raquel Ramos, had no access to the paper in her role as an editorial board member or reviewer.

Contributor Information

S. Raquel Ramos, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Olivia M. O’Hare, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Ailene Hernandez Colon, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Susan Kaplan Jacobs, Health Sciences Librarian/Curator, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Brynne Campbell, Health Sciences Reference Associate, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Trace Kershaw, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and Director, P30 Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS and R25 REIDS HIV Training Programs, School of Public Health, Yale, University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA..

Allison Vorderstrasse, College of Nursing, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA..

Harmony R. Reynolds, Sarah Ross, Soter Center for Women’s Cardiovascular Research, Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology, and Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, NYU School of Medicine, NYU LangoneHealth, New York, New York, USA..

References

- Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, & National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life. (2004). Behavioral health interventions: What works and why? In Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK25527/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfar DC, Khera A, Llyod-Jones JD, McEvoy JW, Michos DE, Miedema DM, Munoz D, Smith CS Jr, Virani SS, Williams AK Sr, Yeboah J, & Ziaeian B (2019). 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 74(10), e177–e232. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E, & Munn Z (2020). Joanna Briggs Institute manual for evidence synthesis. The Joanna Briggs Institute. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballocca F, Gili S, D’Ascenzo F, Marra WG, Cannillo M, Calcagno A, Bonora S, Flammer A, Coppola J, Moretti C, & Gaita F (2016). HIV infection and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Lights and shadows in the HAART era. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 58(5), 565–576. 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FA, Gillman WM, Kemper RA, Krist HA, Kurth EA, Landefeld CS, Lefevre LM, Mangione MC, Phillips RW, Owens KD, Phipps GM, & Pignone P (2016). Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults:U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 316(19), 1997–2007. 10.1001/jama.2016.15450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundhun PK, Pursun M, & Huang W-Q (2017). Does infection with human immunodeficiency virus have any impact on the cardiovascular outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 17(1), 190. 10.1186/s12872-017-0624-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade WT, Reeds DN, Mondy KE, Overton E, Grassino J, Tucker S, Bopp C, Laciny E, Hubert S, Lassa-Claxton S, & Yarasheski KE (2010). Yoga lifestyle intervention reduces blood pressure in HIV‐infected adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors. HIV Medicine, 11(6), 379–388. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00801.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report, 27, 1–114. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cioe PA, Guthrie KM, Freiberg MS, Williams DM, & Kahler CW (2018). Cardiovascular risk reduction in persons living with HIV: Treatment development, feasibility, and preliminary results. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 29(2), 163–177. 10.1016/j.jana.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, Cossette S, Ramirez-Garcia P, De Pokomandy A, Worthington C, Gagnon M-P, Auger P, Boudreau F, Miranda J, Guéhéneuc Y-G, & Tremblay C (2015). Evaluation of a web-based tailored intervention (TAVIE en santé) to support people living with HIV in the adoption of health promoting behaviours: An online randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1042. 10.1186/s12889-015-2310-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JS (2018). Management of long-term complications of HIV disease: Focus on cardiovascular disease. Topics in Antiviral Medicine, 25(4), 133–137. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5935217/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Dooubeni AC, Elpling WJ Jr, Grossman CD, Kemper AR, Kublik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione MC, Phipps GM, Silverstein M, Simono AM, Tseng C-W, & Wong BJ (2018). Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA, 320(11), 1163–1171. 10.1001/jama.2018.13022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrono SE, Lewis JE, Perry A, Signorile J, Tiozzo E, & Jacobs KA (2016). The effect of a community-based exercise program on inflammation, metabolic risk, and fitness levels among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior, 20(5), 1123–1131. 10.1007/s10461-015-1245-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG (2011). HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 141–155. 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Giustini N, Mastroianni CM, Silvestri G, & Vullo V (2014). Taming HIV-related inflammation with physical activity: A matter of timing. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(10), 936–944. 10.1089/aid.2014.0069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan SE, Frontera W, Librizzi J, Ljungquist K, Juan S, Dorman R, Cole EM, Kanter RJ, & Grinspoon S (2006). Effects of a supervised home-based aerobic and progressive resistance training regimen in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus: A randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(11), 1225–1231. 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley AJ, Bodicoat DH, Greaves CJ, Russell C, Yates T, Davies MJ, & Khunti K (2014). Diabetes prevention in the real world: Effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and of the impact of adherence to guideline recommendations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 37(4), 922–933. 10.2337/dc13-2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezema C, Onwunali A, Lamina S, Ezugwu U, Amaeze A, & Nwankwo M (2014). Effect of aerobic exercise training on cardiovascular parameters and CD4 cell count of people living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 17(5), 543–548. 10.4103/1119-3077.141414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein MJ, Achenbach CJ, Stone NJ, & Lloyd-Jones DM (2015). A systematic review of the usefulness of statin therapy in HIV-infected patients. The American Journal of Cardiology, 115(12), 1760–1766. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, Longenecker CT, Hsue P, So-Armah K, Freiberg SM, & Lloyd-Jones DM (2016). Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV-infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. The American Journal of Cardiology, 117(2), 214–220. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA, Bloomfield GS, Currier JS, Freiberg MS, Grinspoon KS, Levin J, Longenecker CT, & Post WS (2019). Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 140(2), e98–e124. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein JL, Gala P, Rochford R, Glesby MJ, & Mehta S (2015). HIV/AIDS and lipodystrophy: Implications for clinical management in resource‐limited settings. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 19033. 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch KV, Anderson EJ, Hubbard JL, Carpenter SJ, Waddell WR, Caliendo AM, & Grinspoon SK (2006). Effects of a lifestyle modification program in HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome. AIDS, 20(14), 1843–1850. 10.1097/01.aids.0000244203.95758.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom AR, Shah AM, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Alonso A, Avery CL, Miedema MD, Konety S, Chang PP, & Solomon SD (2015). American Heart Association’s life’s simple 7: Avoiding heart failure and preserving cardiac structure and function. The American Journal of Medicine, 128(9), 970–976. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Duggan M, Rainie L, & Purcell K (2013, November 26). The diagnosis difference: A portrait of the 45% of US adults living with chronic health conditions. Pew Internet & American Life Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/11/26/the-diagnosis-difference-2/ [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs FD, & Whelton PK (2020). High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension, 75(2), 285–292. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, & Booth A (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon S, & Carr A (2005). Cardiovascular risk and body-fat abnormalities in HIV- infected adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(1), 48–62. 10.1056/NEJMra041811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges S, & Holstad MM (2013). The Impact of a health promotion educational program on cardiovascular risk factors for HIV infected women on antiretroviral therapy. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 4, 224. 10.4172/2155-6113.1000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstad MM, DiIorio C, Kelley ME, Resnicow K, & Sharma S (2011). Group motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors in HIV infected women. AIDS and Behavior, 15(5), 885–896. 10.1007/s10461-010-9865-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2016, October 6). Life expectancy & probability of death. http://www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/life-expectancy-probability-death

- Jaggers JR, Dudgeon W, Blair SN, Sui X, Burgess S, Wilcox S, & Hand GA (2013). A home-based exercise intervention to increase physical activity among people living with HIV: Study design of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 502. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggers JR, Prasad VK, Dudgeon WD, Blair SN, Sui X, Burgess S, & Hand GA (2014). Associations between physical activity and sedentary time on components of metabolic syndrome among adults with HIV. AIDS Care, 26(11), 1387–1392. 10.1080/09540121.2014.920075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster T, & Stead LF (2017). Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD001292. 10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, & O’Brien KK (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Hom PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Roberson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, & Rosamond WD (2010). Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation, 121(4), 586–613. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur RD, Levine SD, & Birk TJ (1993). Supervised exercise training improves cardiopulmonary fitness in HIV-infected persons. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 25(6), 684–688. 10.1249/00005768-199306000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi P, De Socio G, Cicalini S, D’Abbraccio M, Dettorre G, Di Biagio A, Martinelli C, Nunnari G, Rusconi S, Sighinolfi L,Spagnuolo V, & Squillace N (2019). Statins and aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular disease among HIV-positive patients between controversies and unmet needs: review of the literature and suggestions for a friendly use. AIDS Research and Therapy, 16(1), 11. 10.1186/s12981-019-0226-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrani V (2019). The happy older Latinos are active (HOLA) health promotion study in HIV-infected Latino men (HOLA). ClinicalTrials. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03839212?cond5THe1Happy1older1latinos1are1active&draw52&rank51 [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Boruff JT, & Gore GC (2016). Scoping reviews: Establishing the role of the librarian. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(4), 346. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson M, & Glesby MJ (2019). Cardiovascular care in patients with HIV. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Adetokunboh O, Afshin A, Agrawal A, Ahmadi A, Ahmed MB, Aichour AN, AIchour MTE,Aichour I, Aiyar S, Alahdab F, Al-Aly Z, Alam K,& Murray CJL (2017). Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet, 390(10100), 1151–1210. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KA, Peer N, Mills EJ, & Kengne AP (2015). Burden, determinants, and pharmacological management ofhypertension in HIV-positive patients and populations: A systematic narrative review. AIDS Reviews, 17(2), 83–95. 10.1007/978-3-030-10451-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkerk PT (2014). Lifestyle intervention with or without risk-factor passport to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors at the HIV outpatient clinic. Cochrane Library. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=NTR4622 [Google Scholar]

- Okeke NL (2019). Case managers for CVD risk reduction in HIV clinic. ClinicalTrials. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03839394?cond=Case+managers+for+CVD+risk+reduction1in1HIV1clinic&draw=2&rank=1 [Google Scholar]

- Roth GA, Johnson CO, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Ahmed M, Alam K, Alam T, Alvis-Guzman N, Ansari H, Arnlov A, Atey TM,., Awasthi A, Awoke T, Barac A, Barnighausen T, Bedi N, Bennett D, Bensenor I, Biadgilign S, & Murray CJL (2018). The burden of cardiovascular diseases among U.S. states, 1990–2016. JAMA Cardiology, 3(5), 375–389. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E (2018). Life’s simple 7: Vital but not easy. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7(11), e009324. 10.1161/JAHA.118.009324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saumoy M (2012). The effect of an intensive intervention on life style in cardiovascular risk in an HIV-infected cohort with moderate to high cardiovascular risk: A randomized trial. ISRCTN Registry. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN11313360?totalResults=34&pageSize=10&page=1&searchType=basicsearch&offset=7&q=&filters=conditionCategory%3AInfections+and+Infestations%2CrecruitmentCountry%3ASpain&sort= [Google Scholar]

- Shah AS, Stelzle D, Lee KK, Beck EJ, Alam S, Clifford S, Longenecker CT, Strachan F, Bagchi S, Whiteley W, Rajagopalan S, Kottilil S, Nair H, Newby DE, McAllister DA, & Mills NL (2018). Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation, 138(11), 1100–1112. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JH, Hadigan CM, Brown TT, Chadwick E, Feinberg J, Friis-Møller N, Ganesan A, Glesby MJ, Hardy D, Caplan RC, Kim P, Lo J, Martinez E, & Sosman J (2008). Prevention strategies for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients. Circulation, 118(2), e54–e60. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stradling C, Thomas GN, Hemming K, Frost G, Garcia-Perez I, Redwood S, & Taheri S (2016). Randomised controlled pilot study to assess the feasibility of a Mediterranean Portfolio dietary intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction in HIV dyslipidaemia: A study protocol. BMJ Open, 6(2), e010821. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters DJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L,Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tuncalp O, & Straus SE (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Physical activity guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.). USDHHS. [Google Scholar]

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, & Tsao CW (2020). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: A report from the American Heart Association.Circulation, 149(1), E139–E596. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnu A, Belbin GM, Wojcik GL, Bottinger EP, Gignoux CR, Kenny EE, & Loos RJ (2019). The role of country of birth, and genetic and self-identified ancestry, in obesity susceptibility among African and Hispanic Americans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 110(1), 16–23. 10.1093/ajcn/nqz098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos AG, Idris NS, Barth RE, Klipstein-Grobusch K, & Grobbee DE (2016). Pro- inflammatory markers in relation to cardiovascular disease in HIV infection: A systematic review. PLoS One, 11(1), e0147484. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde D (2016). Healing hearts and mending minds in older adults living with HIV. Clinical Trials. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02711878?cond=Healing+hearts+mending+minds+in+older+adults+living+with+HIV&draw=2&rank=1 [Google Scholar]

- Wassel CL, Pankow JS, Peralta CA, Choudhry S, Seldin MF, & Arnett DK (2009). Genetic ancestry is associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease in African-Americans and Hispanics from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics, 2(6), 629–636. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.876243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Moore SM, Longenecker CT, Currie J, Davey CH, Perazzo J, Sattar A, & Josephson RA (2018). A randomized controlled trial of the aystemCHANGE intervention on behaviors related to cardiovascular risk in HIV+ adults. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 78(1), 23. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House Office of National AIDS Policy. (2015, July 30). National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. HIV.gov. https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/nhas-update.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Becofsky K, Wing EJ, McCaffery J, Boudreau M, Evans EW, & Unick J (2019). Behavioral and cardiovascular effects of a behavioral weight loss program for people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 24(4), 1032–1041. 10.1007/s10461-019-02503-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilbermint M, Hannah-Shmouni F, & Stratakis CA (2019). Genetics of hypertension in African Americans and others of African descent. International Journal of MolecularSsciences, 20(5), 1081. 10.3390/ijms20051081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]