Abstract

Mosquito-borne arboviruses, including a diverse array of alphaviruses and flaviviruses, lead to hundreds of millions of human infections each year. Current methods for species-level classification of arboviruses adhere to guidelines prescribed by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), and generally apply a polyphasic approach that might include information about viral vectors, hosts, geographical distribution, antigenicity, levels of DNA similarity, disease association and/or ecological characteristics. However, there is substantial variation in the criteria used to define viral species, which can lead to the establishment of artificial boundaries between species and inconsistencies when inferring their relatedness, variation and evolutionary history. In this study, we apply a single, uniform principle – that underlying the Biological Species Concept (BSC) – to define biological species of arboviruses based on recombination between genomes. Given that few recombination events have been documented in arboviruses, we investigate the incidence of recombination within and among major arboviral groups using an approach based on the ratio of homoplastic sites (recombinant alleles) to non-homoplastic sites (vertically transmitted alleles). This approach supports many ICTV-designations but also recognizes several cases in which a named species comprises multiple biological species. These findings demonstrate that this metric may be applied to all lifeforms, including viruses, and lead to more consistent and accurate delineation of viral species.

Keywords: biological species concept, gene flow, mosquito-borne viruses, recombination

Introduction

There are more than 100 recognized species of mosquito-borne arboviruses, many of which have contributed to world-wide epidemics leading to hundreds of millions of human infections per year [1, 2]. Among the most prevalent and medically important of these arboviruses are Dengue virus, Yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, Zika virus (which are flaviviruses in the family Flaviviridae) and Chikungunya virus (an alphavirus in the family Togaviridae) [3–6]. Both flaviviruses and alphaviruses are positive-sense, ssRNA viruses with genome sizes in the range of 11–12 kb; and the viruses within these taxonomic groups, even when considering only those viruses implicated in human disease, are highly variable and capable of infecting multiple arthropod vectors and vertebrate hosts [7].

The grouping and classification of these viruses has traditionally relied on a variety of phenotypic or molecular properties, such as disease aetiology, provenance, host range, sequence divergence and phylogenetic ancestry [4, 8, 9]. Furthermore, the ICTV (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [10]) defines a viral species, its lowest recognized taxonomic rank designation, as ‘a monophyletic group of viruses whose properties can be distinguished from those of other species by multiple criteria.’ Separate phylogenetic studies have also defined subdivisions within ICTV-defined species based on antigenic, geographical or phylogenetic groupings. This system has led to variation and inconsistency in the ‘multiple criteria’ by which viral species are delineated. For example, Dengue virus consists of four separate, phylogenetically distinct serotypes [11–13] defined by their differences in surface structures, but is considered a single species due to comparable life cycles and shared geographical distributions and vectors [6].

We advocate for the classification of arboviral species using the same system and criteria applied to cellular organisms, i.e. the Biological Species Concept (BSC) [14], which is conventionally used to delineate biological species based on their ability to form reproductively isolated groups whose members interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Although the BSC was originally used to define species of sexual organisms that exchange genetic material, recent studies [15–17] have shown that sufficient levels of gene flow (homologous recombination) can likewise be detected and used to delineate bacterial and viral species. Among viruses, recombination can occur when viruses co-infect a host cell and exchange genetic information, which can enhance diversity and potentially lead to the emergence of novel strains [18]. Applying the BSC can provide uniformity to the manner in which viral species are defined and also designate the range of genetic and phenotypic variation that is capable of reassorting among viruses, which is crucial for understanding the diversity, distribution and aetiology, and potentially the design of agents for the control of viruses. Although robust evidence of recombination in arboviruses is lacking [19–21], several computational approaches have detected potential recombination events in arboviruses [19, 22, 23]. Therefore, adopting new algorithms to detect recombination will provide alternative ways to address the recombination in arboviruses.

In the present study, we analysed the sequenced genomes from multiple ICTV-designated species of arboviruses to determine the amount and sites of recombination among the viral genomes, and to define the limits of biological species. Although viruses do not engage in sexual reproduction, virtually all arboviruses examined display sufficient recombination to be classified by principles underlying the BSC. We detected numerous cases in which the biological boundaries of a named arboviral species are more limited than those defined conventionally in that certain members of a named species show no history of genetic exchange with their presumed conspecifics and form separate biological species.

Methods

Data collection

To test for recombination in arboviruses, we downloaded complete flavivirus and alphavirus genome sequences from the Virus Pathogen Resource database (https://www.viprbrc.org , last accessed 1 March 2019) [24]. We sampled genomes of seven designated species of flaviviruses [West Nile virus (WNV), Usutu virus (USUV), Zika virus (ZIKV), Spondweni virus (SPONV), Dengue virus (DENV), Wesselsbron virus (WESSV) and Yellow fever virus (YFV)], and eight designated species of alphaviruses [Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), Mayaro virus (MAYV), Semliki Forest virus (SFV), Getah virus (GETV), Madariaga virus (MADV) and Sindbis virus (SINV)] (Table 1). Genome sequences containing modified nucleic acids that were used for vaccine development or chimeric sequences were removed prior to analysis (Table S1, available in the online version of this article). Available metadata, including host range, arthropod vector, provenance, serotype and genotype, were compiled for each genome examined.

Table 1.

Number of flavivirus and alphavirus genomes used in this study

|

Genus |

ICTV groupings |

Classically defined viral species |

Abbreviation |

No. of genomes |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Flavivirus |

Mosquito-borne, Japanese encephalitis virus group |

Usutu |

|

USUV |

159 |

|

West Nile |

|

WNV |

1882 |

||

|

Mosquito-borne, unclassified viruses |

Spondweni |

|

SPONV |

21 |

|

|

Mosquito-borne, Ntaya virus group |

Zika |

|

ZIKV |

818 |

|

|

Mosquito-borne, Dengue virus group |

Dengue |

Total |

DENV |

4764 |

|

|

Dengue serotype 1 |

DENV1 |

2019 |

|||

|

Dengue serotype 2 |

DENV2 |

1544 |

|||

|

Dengue serotype 3 |

DENV3 |

963 |

|||

|

Dengue serotype 4 |

DENV4 |

238 |

|||

|

Mosquito-borne, Yellow fever virus group |

Wesselsbron |

|

WESSV |

7 |

|

|

Yellow fever |

|

YFV |

154 |

||

|

Alphavirus |

SFV Complex |

Chikungunya |

|

CHIKV |

663 |

|

Mayaro |

|

MAYV |

31 |

||

|

Semliki Forest |

|

SFV |

14 |

||

|

Getah |

|

GETV |

34 |

||

|

EEEV Complex |

Madariaga |

|

MADV |

32 |

|

|

Eastern equine encephalitis |

|

EEEV |

457 |

||

|

WEEV Complex |

Western equine encephalitis |

|

WEEV |

47 |

|

|

Sindbis |

|

SINV |

230 |

Recombination within and between designated species

To define species of viruses based on the BSC, we estimated the amount of recombination within each designated species using ConSpeciFix version 1.3.0 [25]. ConSpeciFix executes a series of Python scripts to infer instances of recombination by calculating the ratio of homoplastic sites (h, sites that could not be parsimoniously ascribed to vertical ancestry, i.e. recombinant alleles) to non-homoplastic sites (m, vertically transmitted alleles), with higher h/m ratios indicative of higher amounts of recombination [17]. Homoplastic sites and non-homoplastic sites are inferred based on the distance matrix from RAxML version 8.2.11 [26]. ConSpeciFix calculates the degree of recombination (h/m ratios) among genomes by subsampling four to 100 genomes within the dataset with 50 iterations at each sample size. In cases in which the number of available genomes for a selected species was less than 100, the total number of available genomes was set as the maximum for the subsampling process. In cases in which the number of available genomes exceeded 100, we first calculated the phylogenetic distances among all the available genomes using RAxML, and then selected the 100 most distantly related genomes for analysis. When inclusion of certain genomes in the subsampled dataset leads to a substantial decrease of the h/m ratio, those genomes are considered to be members of a different species. In addition, the χ2 test for outliers method implemented in the R package ‘outliers’ [27] was used to test whether certain genomes belong to a different biological species (see Bobay and Ochman 2017, 2018, and [25] for additional methodological details).

To prepare the data for ConSpeciFix, we first annotated all the protein coding genes using Exonerate version 2.2.0 [28], performed a codon-based alignment of each gene independently using MAFFT version 7.407 [29] and then concatenated all of the protein-coding genes. Scripts for codon alignment are available on GitHub (https://github.com/lyy005/codon_alignment/, last accessed 2 April 2020). We then extracted the genomes belonging to different lineages, as suggested by previous studies for WNV [30], USUV [31–33], ZIKV [34], DENV1 [35], DENV2 [36], DENV3 [37], DENV4 [38], YFV [39, 40], MADV [41, 42], WEEV [43], SINV [44–46] and CHIKV [47]. To establish if recombination occurs between different lineages or sublineages, we added to the group of genomes shown to form a biological species based on ConSpeciFix (termed the ‘base lineage’) one genome from a different lineage (the ‘test lineage’), and tested for recombination. To obtain robust estimates of gene flow [25], we performed these tests only on those base lineages that contained at least 15 genomes (Table S2) and pooled one randomly picked genome of a different test lineage to test for recombination using ConSpeciFix. RAxML is implemented within the ConSpeciFix pipeline and is executed using several pipeline-specific parameters. The default maximum RAxML distance parameter in ConSpeciFix (MAX_RAXML_DISTANCE_ALLOWED=1) is restrictive and is designed to eliminate very divergent genomes, such as those belonging to different species, from analyses. To prevent the removal of very divergent viral genomes (particularly during interspecies tests), this distance parameter was adjusted to 100, which is sufficiently large to include all viral genomes, including the very divergent viral genomes, in the analysis. This analysis was extended to examine the incidence and extent of recombination between ICTV-designated species using an analogous method of combining genomes from designated species with at least 15 sequenced representatives with one genome from another species.

To assess the extent to which homoplasies might arise by convergent evolution in a given group of genomes, we simulated genomes based on their distance, as estimated by RAxML, and BIONJ [48] was used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees based on the estimated distance. Seq-Gen version 1.3.4 [49] with GTR model was used to simulate molecular sequences along the phylogenetic trees maintaining the genome length, nucleotide composition and average nucleotide diversity of the sample group. Scripts used for these simulations are available on GitHub (https://github.com/lyy005/conspecifix_arbovirus, last accessed 15 May 2020). The distribution of h/m ratios among simulated genomes was estimated by ConSpeciFix in the same manner performed with empirical data. When the 95 % confidence intervals of simulated genomes do not overlap with those of the actual genomes, we concluded that the observed homoplasies were due to recombination rather than convergent mutations.

Detecting recombination using RDP4

To confirm the events of recombination, we implemented RDP4 using default parameters [50] on the same sets of aligned genomes tested with ConSpeciFix. Programs executed included RDP [51], GENECONV [52], Bootscan [53], Maxchi [54], Chimaera [55], SiSscan [56] and 3Seq [57]. RDP, Bootscan, SiSscan and 3Seq detect recombinant fragments in all the possible triplets or quartets of genomes that are incongruent with the genome phylogeny, whereas GENECONV, Maxchi and Chimaera detect recombination by searching for sequence fragments with significantly higher similarity than the rest of the genomes. We applied the following default window sizes for each method: RDP (30 bp), Bootscan (200 bp), Maxchi (70 bp of variable sites), Chimaera (60 bp of variable sites) and SisScan (200 bp).

Calculation of ANI

We calculated the average degree of nucleotide identity (ANI) values for each species using an in-house Perl script (https://github.com/lyy005/conspecifix_arbovirus, last accessed 15 May 2020). We superimposed ANI data on graphs of plotted h/m ratios in order to infer patterns and rates of recombination among sites, and along the lengths of the genomes. The ANI for each locus was estimated based on sliding windows of 500 bp with a step size of 100 bp.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction

To visualize the phylogenetic relationship between viral species, we reconstructed the phylogenetic tree based on the aligned nucleotide sequences using IQ-Tree version 2.0-rc1 [58] and visualized using ggtree version 2.0.4 [59].

Results

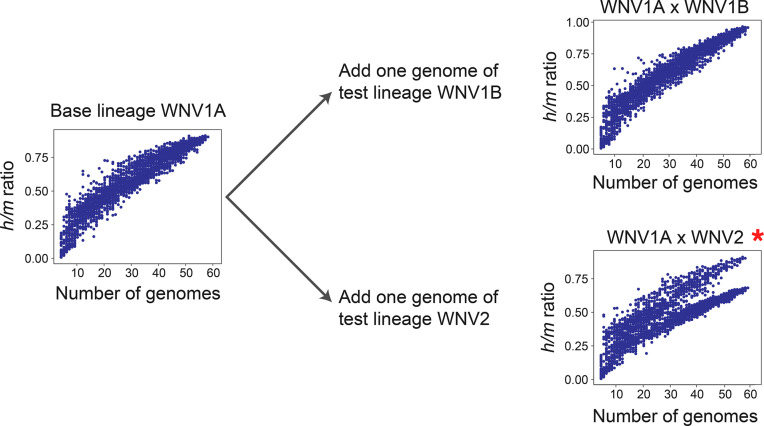

By applying the BSC to define viral species, i.e.; that is, as entities whose members engage in gene exchange, we tested whether and how well genomes currently assigned to an ICTV-designated arboviral species conform to a biological species, and whether any named species comprise multiple biological species or should be merged with other named species. The extent of genetic exchange and recombination for a given set of genomes was based on the ratio of homoplastic (h) polymorphisms to non-homoplastic (m) polymorphisms [25]. When genomes from one recombining biological species are analysed through ConSpeciFix, a single plateauing curve of h/m values emerges; however, when samples contain genomes from more than one biological species, two curves or a sharp drop in h/m ratios is observed, since inclusion of a non-recombining genome decreases the estimation of h and increases the value of m (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Detection of recombination using h/m ratios. Initially, h/m ratios are estimated based on a viral ‘base lineage’, for example West Nile virus genotype 1A (WNV1A), and the single plateauing curve, as shown on the left, is indicative of genomes that constitute a single biological species. Then, a randomly picked genome from a ‘test lineage’ (WNV1B or WNV2) is pooled with the genomes of the base lineage, and if a single plateauing curve remains, as with WNV1B, then the test lineage and the base lineage belong to the same biological species; if two curves are observed, as with WNV2, or there is a sharp drop in the curve (not shown), the test lineage is not a member of the same biological species comprising the base lineage. Note that in all tests, designations to the left of the lower case ‘x’ denote the base lineage, and those to the right side denote the test lineage. Red asterisks indicate that the inclusion of the test lineage in the analysis significantly reduces the h/m ratio.

We analysed genomes assigned to the following seven named species of flaviviruses: Usutu virus (USUV), West Nile virus (WNV), Spondweni virus (SPONV), Zika virus (ZIKV), Dengue virus (DENV), Wesselsbron virus (WESSV) and Yellow fever virus (YFV). Their ssRNA genomes all encode a single reading frame that specifies three structural and seven non-structural proteins in identical order. Although each of these ICTV-designated species might, on first impression, be considered an individual biological species based on the presence of gene exchange among their constituents, the species boundaries, the limits of recombination and the degree of taxonomic sub-structuring offer signals that ICTV designations might not always represent biological species limits.

Recombination in West Nile virus and Usutu virus

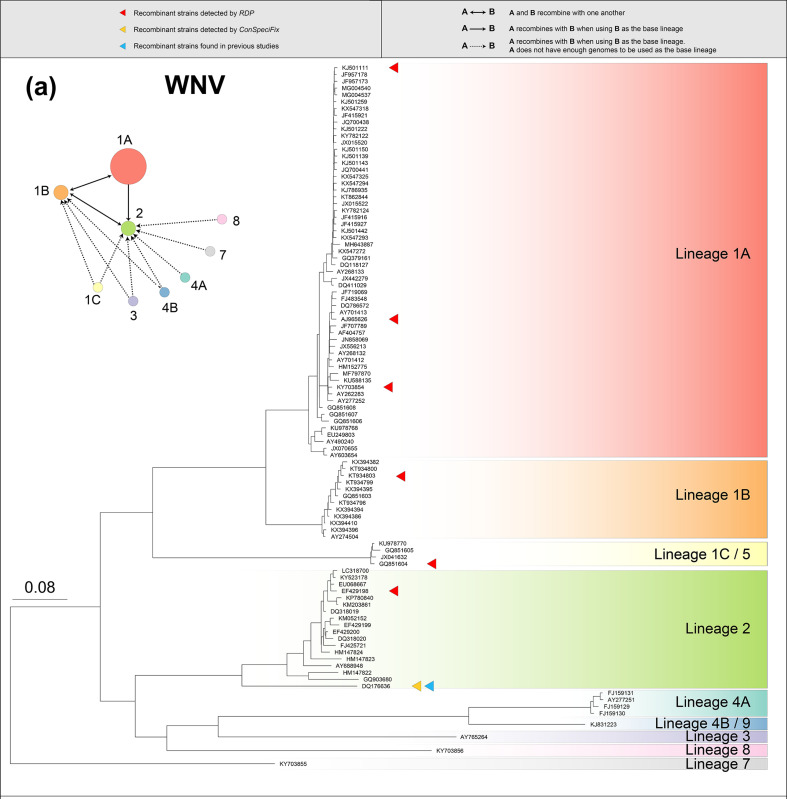

West Nile virus (WNV) and Usutu virus (USUV) are flaviviruses belonging to the mosquito-borne Japanese encephalitis virus group. WNV consists of nine lineages (monophyletic groups) with diverse geographical ranges and various hosts [30]. We estimated the extent of recombination between lineages using tests that combined all the genomes from one of the lineages (the ‘base lineage’) with one genome from a different lineage (the ‘test lineage’). Based on ConSpeciFix, all nine lineages of WNV constitute a single biological species; however, the extent of recombination varies among lineages. WNV lineage 2 (WNV2) has the highest h/m ratio among WNV lineages (Fig. S1) and recombines with all of the lineages (Figs 2 and S1), whereas WNV lineage 1B (WNV1B) recombines with WNV lineages 1A, 1C, 2, 3 and 4B, but not with the other WNV lineages (Fig. S1). Interestingly, WNV1A was initially observed to recombine with WNV2 when WNV2 was used as the base lineage but the reciprocal test (with WNV1A as the base lineage and WNV2 as the test lineage) did not show evidence of recombination. Further analyses between WNV1A and each of the WNV2 genomes indicated that one of the WNV2 genomes, DQ176636, displayed significantly higher amounts of recombination than any of the other WNV2 genomes (χ2 test for outlier; P=0.00237) (Fig. S2). The elevated recombination between DQ176636 and WNV1A is attributable to the hybrid nature of the DQ176636 genome, which resulted from recombination between WNV1A and WNV2, as has been previously reported [60]. In addition to applying ConSpeciFix to recognize recombinants among WNV lineages, we used RDP4 [50] to detect recombination within WNV lineages and discovered six recombinant WNV genomes in WNV lineages 1A, 1B, 1C and 2 that emerged from events of intra-lineage recombination (Fig. 2, Table S3).

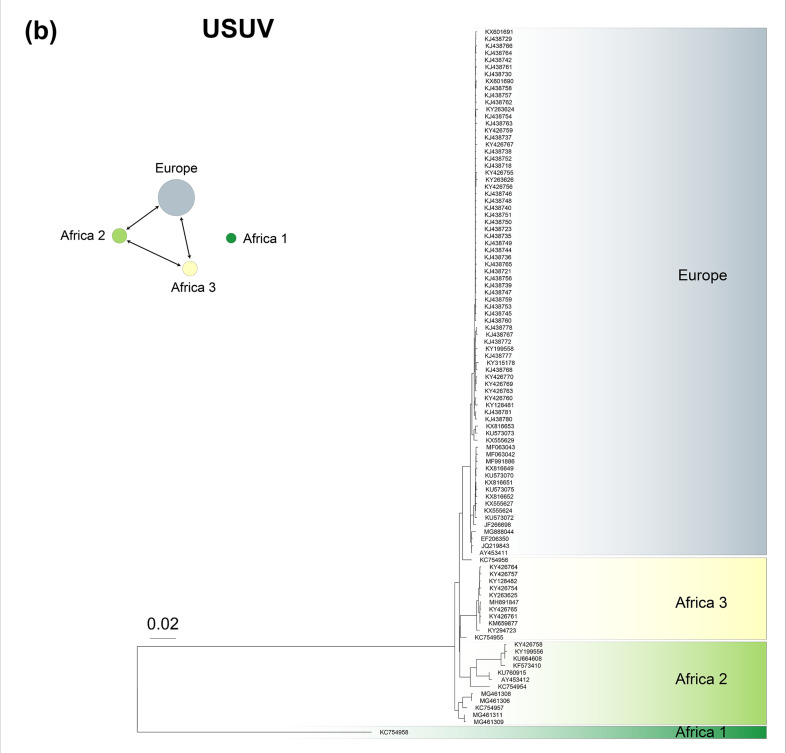

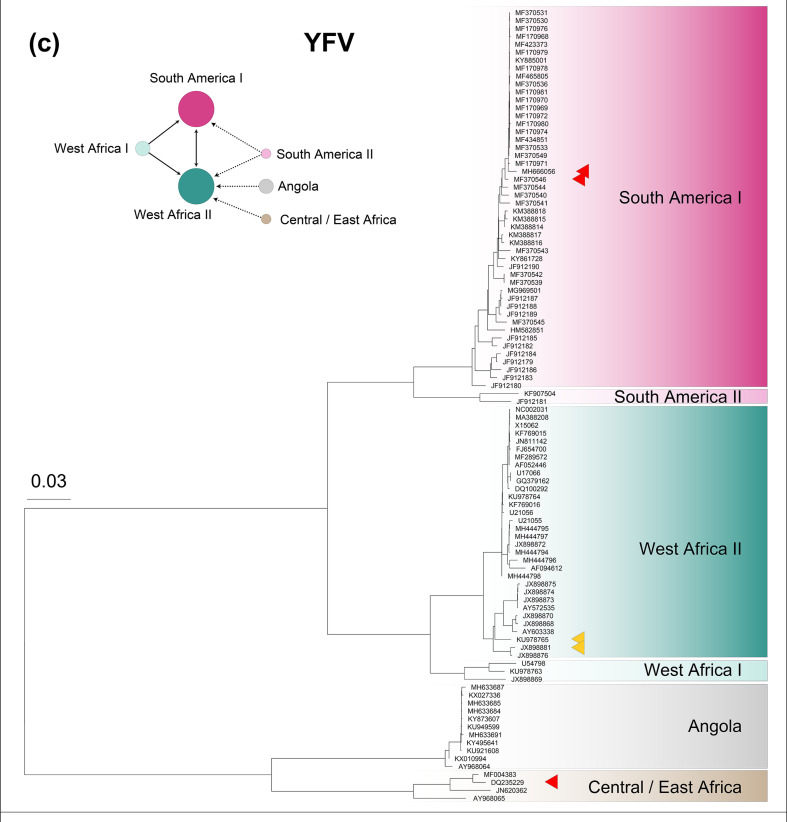

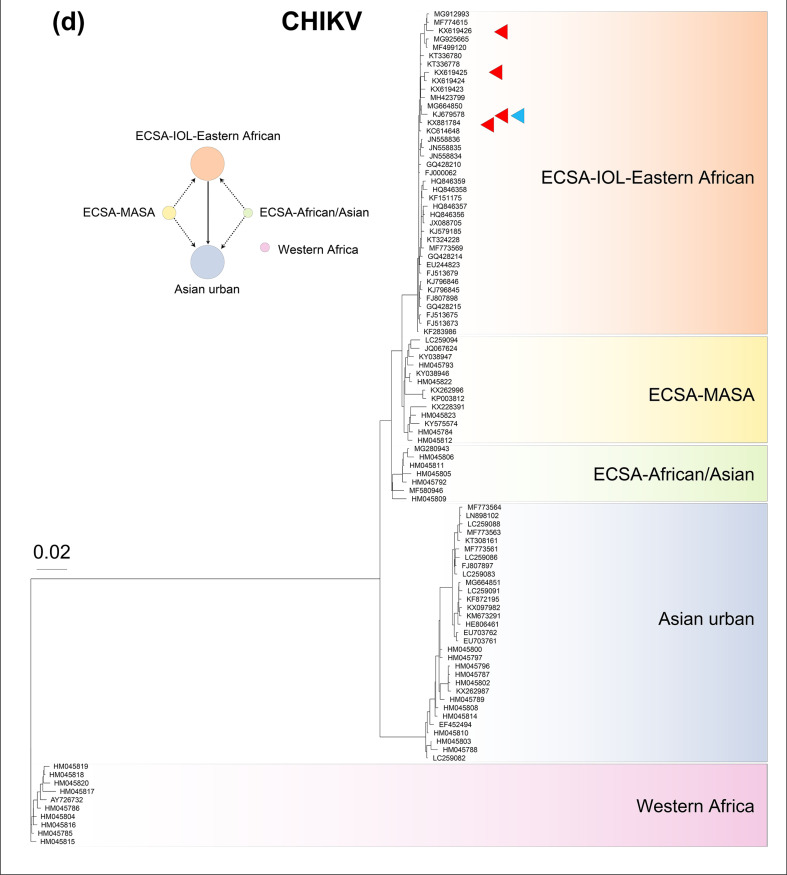

Fig. 2.

Phylogeny of (a) 100 West Nile virus (WNV) genomes, (b) 100 Usutu virus (USUV) genomes, (c) 100 Yellow fever virus (YFV) genomes and (d) 100 Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) genomes. Within each phylogeny, represented lineages or geographical sublineages are colour-coded, and coloured carats denote genomes in which recombination has been detected. Network plots to the left of phylogenetic trees display the recombination network within WNV, USUV, YFV and CHIKV, with circle colours corresponding to those used to denote lineages in each phylogeny and circle sizes are proportional to the number of genomes used in the analysis. Arrows connecting circles show routes of recombination, as described in the key at the top of the figure. Note that in the USUV network, Africa 1 was used as a test lineage with each of the other lineages as the base lineage, and no recombination was detected. The Western Africa lineage of CHIKV was used as a test lineage with each of the other lineages as the base lineage, and no recombination was detected, as is also the case with the Western Africa lineage and the other geographical lineages of CHIKV.

USUV comprises one European and three African lineages that are differentiated by their geographical ranges [32, 33]. All lineages recombine with one another, with the exception of Africa 1, which could be considered a separate biological species (Figs 2 and S3). Tested with both ConSpeciFix and RDP4, there was no recombination between genomes typed as WNV with those typed as USUV. Therefore, WNV and USUV are represented by three biological species (WNV, USUV Africa 1 and the remaining USUV lineages).

Recombination within and among Dengue serotypes

The Dengue antigenic complex is partitioned into four serotypes (DENV serotypes 1–4), which together form a single ICTV-designated species. Recombination is detected within each of the Dengue serotypes, with the exception of a single DENV2 genome (KX274130) (Fig. S4). Examining recombination among Dengue serotypes, our findings support that DENV1, 3 and 4 are each separate biological species, and that DENV2 comprises two biological species (in that KX274130 does not recombine with other DENV2 genomes). KX274130 is even more genetically distinct (ANI=76 %) from other DENV2 lineages than from the sylvatic DENV2 genomes [61].

As noted previously [22], intra-serotype recombination is prevalent among Dengue viruses. There are 11, 20, 14 and 10 intra-serotype recombinant genomes in DENV1, DENV2, DENV3 and DENV4, respectively, based on ConSpeciFix, RDP4 and previous studies [23, 36–38] but we find no evidence of inter-serotype recombination, as was previously reported by Worobey et al. [23].

Recombination within and among other flaviviruses

Prompted by the finding that biological species limits do not always match ICTV-designated species, we analysed representative genomes from other named flavivirus species and tested for recombination.

Zika virus

There are two lineages of ZIKV – an African lineage and an Asian lineage [34, 62] – and we found that all genomes, despite their geographical origins, belong to a single biological species. Although there is usually more recombination within each of the geographical lineages, genome KX601167 (isolated in Malaysia in 1966 and classified as an Asian lineage genome [34]) shows significantly elevated recombination with African lineages based on a χ2 test for outliers (P=1.859e-12) (Figs S5 and S6), and KY241712, another Asian lineage, displays significantly higher recombination in the capsid (C) and envelope protein (E) genes compared to other Asian lineage genomes (Fig. S6).

Yellow fever virus

We evaluated the extent of recombination in six YFV lineages: South America I (SA I), South America II (SA II), West Africa I (WA I), West Africa II (WA II), Angola and Central/East Africa (CEA) (Fig. 2) [39]. Although all lineages are members of a single biological species (Fig. S7), recombination is not continuous among lineages: lineages SA I, SA II and WA I do not recombine with the Angola or Central/East Africa lineages. The pattern of recombination events among YFV genomes is consistent with the demographic histories of lineages. For example, the West Africa lineages (WA I and WA II) and South America lineages (SA I and SA II) recombine with one another, as supported by previous findings that YFV was introduced into South America from West Africa through slave trade from around 400 years ago [63, 64]. YFV was previously shown to have a relatively low level of recombination [65 and Holmes 2003 [66], and RDP4 analysis detected only three recombinant genomes (KU978765, JX898881 and DQ235229).

Spondweni virus and Wesselsbron virus

There are low h/m ratios and no recombinant genomes detected in SPONV and WESSV, designating each as a clonal species refractory to classification by the BSC. It is noteworthy that SPONV and WESSV both have very small numbers of available genomes (21 and eight, respectively) (Table 1), so the inability to detect recombination could be due to both low rates of genetic exchange and limited sampling. Although SPONV is not an ICTV-designated species, we included the genomes of SPONV in our analysis due to its close relationship to ZIKV.

Recombination between flaviviruses

Lastly, we performed recombination analyses between all pairs of ICTV-designated flaviviruses using ConSpeciFix and RDP4. There is, as yet, no evidence of recombination between ICTV-designated species. Thus, the boundaries of biological species in flaviviruses are similar, although often narrower, than those defined by their ICTV-designations.

Recombination within alphavirus complexes

Alphaviruses constitute a second major taxonomic group of mosquito-borne arboviruses, and we analysed genomes assigned to the following eight named species: Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) and Madariaga virus (MADV), both members of the EEEV complex; Sindbis virus (SINV) and Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), both members of the WEEV complex; and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Mayaro virus (MAYV), Semliki forest virus (SFV) and Getah virus (GETV), all members of the SFV complex. The ssRNA genomes of the alphaviruses contain two ORSs, one encoding five structural proteins and the second encoding four non-structural proteins.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus complex

EEEV comprises a single lineage distributed in North America and the Caribbean, whereas MADV, also known as the ‘South American’ Eastern equine encephalitis virus, contains three lineages [41]. EEEV and MADV display some ecological and genetic differences: EEEV genomes are highly conserved (minimum ANI=98 %) and can lead to severe disease in humans, whereas MADV is more divergent (minimum ANI=80 %), uses different hosts, and is not clearly associated with human disease [67–69]. Results from ConSpeciFix support the current designations of EEEV and MADV as distinct biological species, with the three MADV lineages all belonging to the same biological species (Figs S5 and S8).

Western equine encephalitis virus complex

WEEV is known to be a recombinant between an EEEV-like virus and an SINV-like virus [70, 71]. WEEV consists of a North American and a South American lineage, and inclusion of the South American GQ287646 genome in ConSpeciFix analysis substantially reduces h/m ratios, indicating the presence of two biological species within WEEV (Fig. S9) [43].

SINV contains three lineages (lineage I, lineage IV, lineage SW-Australia), with lineage I harbouring the most diversity and containing seven geographically partitioned sublineages [44, 45]. Analysis of recombination in multiple combinations of genomes from the different lineages and sublineages revealed that SINV comprises five biological species (Fig. S11): the HRSP lineage, Southwest Australia lineage of SINV (AF429428), the most divergent genome of Lineage I (MF409177), the rest of Lineage I and Lineage IV, all manifest as distinct species as they do not recombine with any other SINV lineages (Figs S5 and S10).

Semliki forest virus complex

We estimated recombination within and between the Western African (WA), Asian Urban (AUL) and East Central and South African (ECSA) lineages of CHIKV. The Asian Urban lineage (AUL) has two sublineages, one containing older genomes (those isolated prior to 1996) and a re-emerging group (genomes isolated after 2006) [72], and the ECSA lineage includes three geographical sublineages – the Indian Ocean (IOL)-Eastern African, Middle African South American (MASA) and African/Asian sublineages [47]. We found that all the lineages of CHIKV recombine with one another except for the Western African (WA) lineage (Figs 2 and S11), which is an enzootic lineage, whereas all others are epidemic lineages [73].

The other ICTV-designated species within the Semliki forest virus complex, MAYV and GETV, constitute one biological species respectively. SFV does not have enough genomes for within-species ConSpeciFix analysis and therefore was only used as a test lineage.

Having determined that some of the ICTV-designated species of alphaviruses contain multiple biological species, we investigated the extent of recombination between all possible pairs of ICTV-designated alphavirus species. For example, it has already been shown that WEEV genomes are recombinants between members of the EEEV complex and SINV-like viruses [70, 71] (Table S3), despite their low level of sequence identity (ANI≈60 %) and lack of detectable recombination among sequenced genomes (Table S4, Fig. S12). Based on ConSpeciFix, there is no evidence of recombination between the ICTV-designated alphavirus species. In contrast, all of the recombination detection programs implemented in RDP4 identified WEEV as a recombinant species between EEEV and SINV.

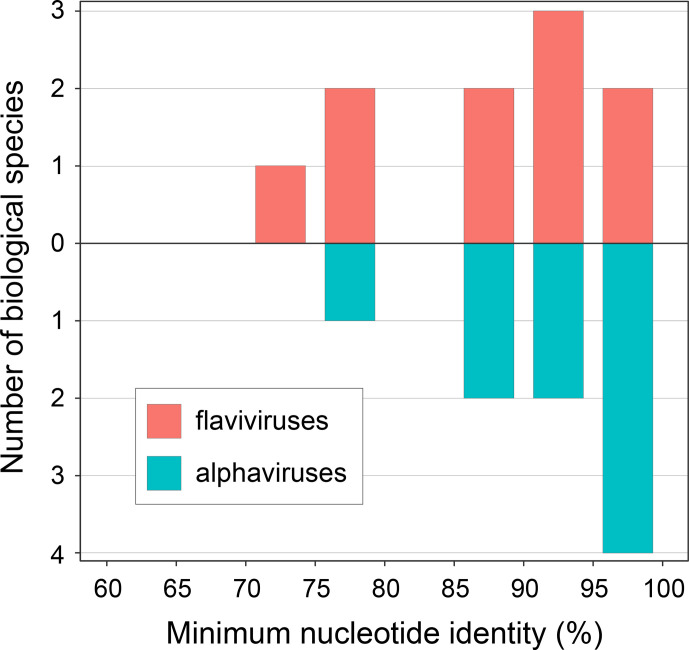

To further understand the relationship between species boundaries and the overall degree of genomic sequence similarity required to maintain the ability to recombine, we calculated ANI for the most divergent genomes within the same biological species (Fig. 3). Among alphaviruses, the minimum amount of nucleotide identity between members of the same species averages 94 %, with MADV showing the most within-species divergence (minimum ANI=79 %). In flaviviruses, the minimum nucleotide identity between members of the same species averages 90 %, with WNV showing the most within-species divergence (minimum ANI=74 %).

Fig. 3.

Nucleotide sequence similarity between the most divergent members of the same biological species. For each species, minimum nucleotide sequence similarity is calculated as the average nucleotide identity (ANI) between genomes.

Discussion

Species-level classification of arboviruses is conventionally based on an approach that integrates multiple properties, often incorporating knowledge of viral vectors, hosts, geographical distribution, antigenicity, disease association, ecology and genome sequence. Our aim in the present study was to incorporate a single criterion – the ability to exchange genetic material – in order to enhance consistency to the delineation of viral species. Moreover, this criterion is the benchmark of the BSC, which stands as the most widely applied procedure for defining species. It is conventionally thought that viruses, being asexual, are not amenable to species-level classification based on gene flow because each clonal individual is reproductively isolated from one another. However, except for those few incidences of individual viral genomes that do not form part of the recombining population and should themselves be viewed as separate species (e.g. the Africa 1 lineage of Usutu virus; the KX274130 genome of Dengue 2), the vast majority of arboviruses that we analysed displayed sufficient levels of recombination to allow classification as true biological species. This parallels what was reported in an analysis of recombination in an array of RNA and DNA animal viruses and bacteriophages in which over 85 % of named taxa were amenable to species-level classification based on the BSC (Bobay and Ochman 2018).

Aside from reconciling the manner in which all lifeforms are classified at the species level, there are both practical and pragmatic reasons for identifying members of recombining populations of viruses that are reproductively isolated from other such viral groups. Although recombination is not required for arbovirus life cycles, members from the same biological species can exchange genes during an infection of the same host through a ‘copy-choice’ process [18]. Knowing the limits of recombination helps define what sequences, and what properties, are transmissible to a genome through homologous exchange, potentially altering the range, infectivity or antigenic properties of a virus.

Nonetheless, robust evidence of recombination among arboviruses is limited. The lack of appropriate experimental systems to detect and isolate viable recombinant arboviruses [19–21] could contribute to the rare detection of recombinant arboviruses. Although few studies [71, 74] have confirmed recombination in arboviruses, our findings are consistent with other studies detecting recombination based on genome similarity and phylogeny [19, 22, 23]. Our novel approach provides another alternative to describe and further delineate recombination boundaries.

Many of the BSC-defined species that we identified are consistent with their ICTV designations, with the notable exceptions that among the flaviviruses, DENV and USUV, and among the alphaviruses, SINV and CHIKV, each contained multiple biological species. The BSC-defined species were often more accurate in discriminating viral lineages derived from different sylvatic ancestors or, in some cases, lineages with distinct geographical distributions. For example, the four DENV serotypes are traditionally considered to form a single species in that they co-circulate in the same geographical regions, share the same vectors and manifest similar disease symptoms. However, each of the DENV serotypes recombines only with members on its own serotype, and partitioning into four species would be consistent with their independent evolution from sylvatic progenitors [75, 76], variable antigenic characteristics [77]; Katzelnick et al. 2015) and different efficacy against vaccines [78, 79].

Similarly, a recombination-based approach also assigned the Western African (WA) lineage of CHIKV to a distinct biological species, separate from the other CHIKV lineages, East Central and South African (ECSA), and Asian Urban (AUL). The WA lineage is limited geographically to sylvatic areas of Africa [73, 80, 81], whereas the other CHIKV lineages, which together form a single biological species, circulate globally. Additionally, the ECSA lineage has a sylvatic ancestry independent from that of the WA lineage [72].

Even in cases in which an individual viral genome or lineage constitutes a separate biological species, it is possible to find indications that it is not a member of the recombining population. For example, the USUV Africa 1 lineage does not co-circulate with the other three lineages [82], and the SINV HRSP lineage is a laboratory domesticate that does not co-circulate with other lineages [83]. That BSC-defined species are largely consistent with the polyphasic method of species classification currently in use indicates that the BSC serves as a single, uniform and informative criterion that can meaningfully complement arbovirus classification. The degree of genetic divergence within the biological species of arboviruses, which range from 74 to 98 % based on ANI, is comparable with those of other animal viruses (Bobay and Ochman 2018), and the variation in this range signals that no single sequence identity threshold can be applied to delineate the boundaries of viral species.

In addition to ConSpeciFix, we applied multiple sequence- and phylogeny-based approaches to measure recombination among arboviral genomes. Because h/m ratios are calculated based on each nucleotide, ConSpeciFix is able to detect recombination events of a different scale than most other methods, which typically search for stretches of recombinant sites and recombination breakpoints. However, this feature also makes ConSpeciFix less sensitive to ancient recombination events. For example, WEEV is known to be a recombinant virus, arising about 1300 to 1900 years ago from recombination between EEEV and SINV [71]; however, ConSpeciFix views WEEV, EEEV and SINV as three separate species because the subsequent occurrence of new mutations eliminated many homoplastic sites.

Among the recombining lineages or geographical sublineages within a species, several displayed asymmetric patterns, such that recombination was detected when using one lineage as the base lineage but not when using the other lineage as the base lineage. For example, WNV1A and WNV2 were shown to recombine with one another when using WNV2 as the base lineage but not when WNV1A was used as the base lineage, an asymmetry caused by the inclusion of the recombinant genome DQ176636 in the recombination test. When we subsequently selected a random WNV2 genome to compare with all of the WNV1A genomes (guaranteeing that the recombinant genome DQ17663 was not included in the analysis), h/m decreased (‘WNV1A × WNV2’ in Fig. S1); however, when using WNV2 as the base lineage (such that DQ176636 was included), it resulted in a single, plateauing h/m curve indicative of recombination (‘WNV2 × WNV1A’ in Fig. S1). The shared geographical distribution of WNV1A and WNV2 can create opportunities for the co-infection of the two lineages at the same time, facilitating events of recombination.

The finding that arboviral species can be delineated by principles of the BSC implies that gene flow can serve as a universal and unifying approach for the classification of all lifeforms, including viruses, at the species level across viruses. The BSC-defined species recognized in this study are often more consistent than ICTV-designated species with respect to their biological properties, including evolutionary history and geographical distribution. Defining the biological species boundaries is useful both for describing the relatedness of existing arboviruses, and potentially, for providing information about emerging arboviruses.

Data Availability

The bioinformatic scripts and arboviral genome sequences used in this study are available on GitHub (https://github.com/lyy005/conspecifix_arbovirus, last accessed 15 May 2020).

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number R35GM118038) and the National Science Foundation (grant numbers DEB-1831730, DEB-1551092).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kim Hammond for assistance with preparation of figures. We also thank Brian Shin-Hua Ellis for optimizing the code of ConSpeciFix for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANI, average nucleotide identity; BSC, biological species concept; CHIKV, Chikungunya virus; DENV1, Dengue serotype 1; DENV2, Dengue serotype 2; DENV3, Dengue serotype 3; DENV4, Dengue serotype 4; DENV, Dengue virus; EEEV, Eastern equine encephalitis virus; GETV, Getah virus; ICTV, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; MADV, Madariaga virus; MAYV, Mayaro virus; SFV, Semliki Forest virus; SINV, Sindbis virus; SPONV, Spondweni virus; USUV, Usutu virus; WEEV, Western equine encephalitis; WESSV, Wesselsbron virus; WNV, West Nile virus; YFV, Yellow fever virus; ZIKV, Zika virus.

Eleven supplementary figures and two supplementary tables are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasilakis N, Gubler DJ. Arboviruses: Molecular Biology, Evolution and Control. UK: Caister Academic Press. Poole; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braack L, Gouveia de Almeida AP, Cornel AJ, Swanepoel R, de Jager C. Mosquito-Borne arboviruses of African origin: review of key viruses and vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2559-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Jiang D, Ni M, Li J, Chen Z, et al. Phylogenomic analysis unravels evolution of yellow fever virus within hosts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbach R, Junglen S, van Rij RP. Mosquito-specific and mosquito-borne viruses: evolution, infection, and host defense. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2017;22:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, Gould EA, Meyers G, et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017;98:2–3. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutchko KM, Madden EA, Morrison C, Plante KS, Sanders W, et al. Structural divergence creates new functional features in alphavirus genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:3657–3670. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmonds P, Adams MJ, Benkő M, Breitbart M, Brister JR, et al. Consensus statement: virus taxonomy in the age of metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:161–168. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefkowitz EJ, Dempsey DM, Hendrickson RC, Orton RJ, Siddell SG, et al. Virus taxonomy: the database of the International Committee on taxonomy of viruses (ICTV) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D708–D717. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams MJ, Lefkowitz EJ, King AMQ, Carstens EB. Recently agreed changes to the International Code of virus classification and nomenclature. Arch Virol. 2013;158:2633–2639. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1749-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa RL, Voloch CM, Schrago CG. Comparative evolutionary epidemiology of dengue virus serotypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henchal EA, Putnak JR. The dengue viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:376–396. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.4.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrivastava S, Tiraki D, Diwan A, Lalwani SK, Modak M, et al. Co-circulation of all the four dengue virus serotypes and detection of a novel clade of DENV-4 (genotype I) virus in Pune, India during 2016 season. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayr E. The biological species concept. In: Wheeler QD, Meier R, editors. Species Concepts and Phylogenetic Theory: A Debate. NY: Columbia University Press; 2000. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobay L-M, Ochman H. Biological species are universal across Life’s domains. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:491–501. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bobay L-M, O'Donnell AC, Ochman H. Recombination events are concentrated in the spike protein region of Betacoronaviruses. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1009272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobay L-M, Ochman H. Biological species in the viral world. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:6040–6045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717593115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Losada M, Arenas M, Galán JC, Palero F, González-Candelas F. Recombination in viruses: mechanisms, methods of study, and evolutionary consequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;30:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaskov J, Buzacott K, Field E, Lowry K, Berlioz-Arthaud A, et al. Multiple recombinant dengue type 1 viruses in an isolate from a dengue patient. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:3334. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taucher C, Berger A, Mandl CW. A trans-complementing recombination trap demonstrates a low propensity of flaviviruses for intermolecular recombination. J Virol. 2010;84:599–611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01063-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver SC, Costa F, Garcia-Blanco MA, Ko AI, Ribeiro GS, et al. Zika virus: history, emergence, biology, and prospects for control. Antiviral Res. 2016;130:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes EC, Worobey M, Rambaut A. Phylogenetic evidence for recombination in dengue virus. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:405–409. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worobey M, Rambaut A, Holmes EC. Widespread intra-serotype recombination in natural populations of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7352–7357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickett BE, Sadat EL, Zhang Y, Noronha JM, Squires RB, et al. ViPR: an open bioinformatics database and analysis resource for virology research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D593–D598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bobay L-M, Ellis BS-H, Ochman H. ConSpeciFix: classifying prokaryotic species based on gene flow. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3738–3740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komsta L. Tests for outliers. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=outliers . 2011

- 28.Slater GSC, Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fall G, Di Paola N, Faye M, Dia M, Freire CCdeM, et al. Biological and phylogenetic characteristics of West African lineages of West Nile virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadar D, Lühken R, van der Jeugd H, Garigliany M, Ziegler U, et al. Widespread activity of multiple lineages of Usutu virus, Western Europe, 2016. Euro Surveill. 2017;22:30452. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.4.30452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engel D, Jöst H, Wink M, Börstler J, Bosch S, et al. Reconstruction of the evolutionary history and dispersal of Usutu virus, a neglected emerging arbovirus in Europe and Africa. mBio. 2016;7:e01938–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01938-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roesch F, Fajardo A, Moratorio G, Vignuzzi M. Usutu virus: an arbovirus on the rise. Viruses. 2019;11:640. doi: 10.3390/v11070640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong Z, Xu X, Han G-Z. The diversification of Zika virus: are there two distinct lineages? Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:2940–2945. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollett S, Melendrez MC, Maljkovic Berry I, Duchêne S, Salje H, et al. Understanding dengue virus evolution to support epidemic surveillance and counter-measure development. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;62:279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waman VP, Kolekar P, Ramtirthkar MR, Kale MM, Kulkarni-Kale U. Analysis of genotype diversity and evolution of dengue virus serotype 2 using complete genomes. PeerJ. 2016b;4:e2326. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waman VP, Kale MM, Kulkarni-Kale U. Genetic diversity and evolution of dengue virus serotype 3: a comparative genomics study. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;49:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waman VP, Kasibhatla SM, Kale MM, Kulkarni-Kale U. Population genomics of dengue virus serotype 4: insights into genetic structure and evolution. Arch Virol. 2016a;161:2133–2148. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2886-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beasley DWC, McAuley AJ, Bente DA. Yellow fever virus: genetic and phenotypic diversity and implications for detection, prevention and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2015;115:48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen R, Mukhopadhyay S, Merits A, Bolling B, Nasar F, et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Togaviridae. J Gen Virol. 2018;99:761–762. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arrigo NC, Adams AP, Weaver SC. Evolutionary patterns of eastern equine encephalitis virus in North versus South America suggest ecological differences and taxonomic revision. J Virol. 2010b;84:1014–1025. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01586-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lednicky JA, White SK, Mavian CN, El Badry MA, Telisma T, et al. Emergence of Madariaga virus as a cause of acute febrile illness in children, Haiti, 2015-2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0006972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergren NA, Auguste AJ, Forrester NL, Negi SS, Braun WA, et al. Western equine encephalitis virus: evolutionary analysis of a declining alphavirus based on complete genome sequences. J Virol. 2014;88:9260–9267. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01463-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling J, Smura T, Lundström JO, Pettersson JH-O, Sironen T, et al. Introduction and dispersal of Sindbis virus from central Africa to Europe. J Virol. 2019;93:e00620–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00620-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundström JO, Pfeffer M. Phylogeographic structure and evolutionary history of Sindbis virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:889–907. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pickering P, Aaskov JG, Liu W. Complete genomic sequence of an Australian Sindbis virus isolated 44 years ago reveals unique indels in the E2 and NSP3 proteins. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8:e00246–19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00246-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider AdeB, Ochsenreiter R, Hostager R, Hofacker IL, Janies D, et al. Updated phylogeny of Chikungunya virus suggests lineage-specific RNA architecture. Viruses. 2019;11:798. doi: 10.3390/v11090798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gascuel O. BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:685–695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rambaut A, Grassly NC. Seq-Gen: an application for the Monte Carlo simulation of DNA sequence evolution along phylogenetic trees. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:235–238. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1:vev003. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin DP, Posada D, Crandall KA, Williamson C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:98–102. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith JM. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Posada D, Crandall KA. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: computer simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13757–13762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241370698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibbs MJ, Armstrong JS, Gibbs AJ. Sister-scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:573–582. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lam HM, Ratmann O, Boni MF. Improved algorithmic complexity for the 3SEQ recombination detection algorithm. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:247–251. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, TTY L. ggtree: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods in Ecol and Evol. 2017;8:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pickett BE, Lefkowitz EJ. Recombination in West Nile virus: minimal contribution to genomic diversity. Virol J. 2009;6:165. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu W, Pickering P, Duchêne S, Holmes EC, Aaskov JG. Highly divergent dengue virus type 2 in traveler returning from Borneo to Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:2146–2148. doi: 10.3201/eid2212.160813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beaver JT, Lelutiu N, Habib R, Skountzou I. Evolution of two major Zika virus lineages: implications for pathology, immune response, and vaccine development. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1640. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bryant JE, Holmes EC, Barrett ADT. Out of Africa: a molecular perspective on the introduction of yellow fever virus into the Americas. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nunes MRT, Palacios G, Cardoso JF, Martins LC, Sousa EC, et al. Genomic and phylogenetic characterization of Brazilian yellow fever virus strains. J Virol. 2012;86:13263–13271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00565-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Twiddy SS, Holmes EC. The extent of homologous recombination in members of the genus flavivirus. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:429–440. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGee CE, Tsetsarkin KA, Guy B, Lang J, Plante K, et al. Stability of yellow fever virus under recombinatory pressure as compared with Chikungunya virus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arrigo NC, Adams AP, Watts DM, Newman PC, Weaver SC. Cotton rats and house sparrows as hosts for North and South American strains of eastern equine encephalitis virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010a;16:1373–1380. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carrera J-P, Forrester N, Wang E, Vittor AY, Haddow AD, et al. Eastern equine encephalitis in Latin America. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:732–744. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vittor AY, Armien B, Gonzalez P, Carrera J-P, Dominguez C, et al. Epidemiology of emergent madariaga encephalitis in a region with endemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis: initial host studies and human cross-sectional study in Darien, Panama. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hahn CS, Lustig S, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Western equine encephalitis virus is a recombinant virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5997–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weaver SC, Kang W, Shirako Y, Rumenapf T, Strauss EG, et al. Recombinational history and molecular evolution of Western equine encephalomyelitis complex alphaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:613–623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.1.613-623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen R, Puri V, Fedorova N, Lin D, Hari KL, et al. Comprehensive genome scale phylogenetic study provides new insights on the global expansion of Chikungunya virus. J Virol. 2016;90:10600–10611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01166-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Volk SM, Chen R, Tsetsarkin KA, Adams AP, Garcia TI, et al. Genome-Scale phylogenetic analyses of Chikungunya virus reveal independent emergences of recent epidemics and various evolutionary rates. J Virol. 2010;84:6497–6504. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chuang CK, Chen WJ. Experimental evidence that RNA recombination occurs in the Japanese encephalitis virus. Virology. 2009;394:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Twiddy SS, Holmes EC, Rambaut A. Inferring the rate and time-scale of dengue virus evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:122–129. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang E, Ni H, Xu R, Barrett AD, Watowich SJ, et al. Evolutionary relationships of endemic/epidemic and sylvatic dengue viruses. J Virol. 2000;74:3227–3234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3227-3234.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vasilakis N, Durbin AP, da Rosa APAT, Munoz-Jordan JL, Tesh RB, et al. Antigenic relationships between sylvatic and endemic dengue viruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hadinegoro SR, Arredondo-García JL, Capeding MR, Deseda C, Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. Efficacy and long-term safety of a dengue vaccine in regions of endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-García JL, Rivera DM, Cunha R, et al. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:113–123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Filomatori CV, Bardossy ES, Merwaiss F, Suzuki Y, Henrion A, et al. RNA recombination at Chikungunya virus 3'UTR as an evolutionary mechanism that provides adaptability. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007706. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Langsjoen RM, Haller SL, Roy CJ, Vinet-Oliphant H, Bergren NA, et al. Chikungunya virus strains show lineage-specific variations in virulence and cross-protective ability in murine and nonhuman primate models. mBio. 2018;9:e02449–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02449-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sieg M, Schmidt V, Ziegler U, Keller M, Höper D, et al. Outbreak and cocirculation of three different Usutu virus strains in eastern Germany. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:662–664. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strauss EG, Rice CM, Strauss JH. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of Sindbis virus. Virol. 1984;133:92–110. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The bioinformatic scripts and arboviral genome sequences used in this study are available on GitHub (https://github.com/lyy005/conspecifix_arbovirus, last accessed 15 May 2020).