Abstract

Background: Thyroid hormone (TH) has important functions in controlling hepatic lipid metabolism. Individuals with resistance to thyroid hormone beta (RTHβ) who harbor mutations in the THRB gene experience loss-of-function of thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ), which is the predominant TR isoform expressed in the liver. We hypothesized that individuals with RTHβ may have increased hepatic steatosis.

Methods: Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) was assessed in individuals harboring the R243Q mutation of the THRB gene (n = 21) and in their wild-type (WT) first-degree relatives (n = 22) using the ultrasound-based transient elastography (TE) device (FibroScan). All participants belonged to the same family, lived on the same small island, and were therefore exposed to similar environmental conditions. CAP measurements and blood samples were obtained after an overnight fast. The observers were blinded to the status of the patients.

Results: The hepatic fat content was increased in RTHβ individuals compared with their WT relatives (CAP values of 263 ± 21 and 218.7 ± 43 dB/m, respectively, p = 0.007). The CAP values correlated with age and body mass index (BMI) (age: r = 0.55, p = 0.011; BMI: r = 0.51, p = 0.022) in the WT first-degree relatives but not in RTHβ individuals, suggesting that the defect in TRβ signaling was predominant over the effects of age and obesity. Circulating free fatty acid levels were significantly higher in RTHβ individuals (0.29 ± 0.033 vs. 0.17 ± 0.025 mmol/L, p = 0.02). There was no evidence of insulin resistance evaluated by the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance in both groups studied.

Conclusions: Our findings provide evidence that impairments in intrahepatic TRβ signaling due to mutations of the THRB gene can lead to hepatic steatosis, which emphasizes the influence of TH in the liver metabolism of lipids and provides a rationale for the development TRβ-selective thyromimetics. Consequently, new molecules with a very high TRβ affinity and hepatic selectivity have been developed for the treatment of lipid-associated hepatic disorders, particularly nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Keywords: hepatic steatosis, resistance to thyroid hormone beta, thyroid hormones, transient elastography

Introduction

Thyroid hormone (TH) is known to play a central role in hepatic triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism (1). Hypothyroidism is associated with fatty liver; thus, TH treatment reduces hepatic steatosis (2,3). These effects of TH on hepatic lipid homeostasis are primarily exerted through thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ), the predominant isoform expressed in the liver (1). The effects of TH on hepatic lipid metabolism are mediated by the transcriptional regulation of the target genes involved in several pathways of lipid homeostasis, including lipogenesis, beta-oxidation, autophagy, and cholesterol metabolism (1). Recently, TRβ-targeted therapies have shown great promise for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (4).

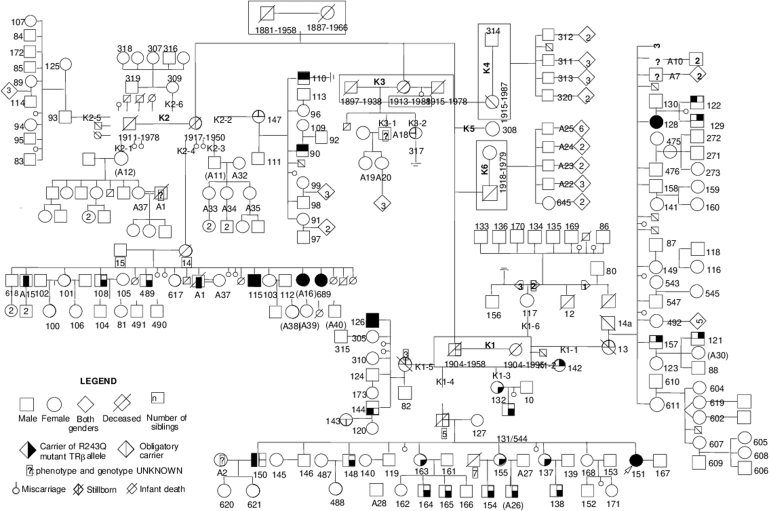

Individuals with resistance to thyroid hormone beta (RTHβ), which is caused by mutations of the THRB gene, experience loss-of-function of TRβ. We wondered whether the intrahepatic fat content is increased in adult RTHβ individuals compared with their unaffected family members. Thus, we studied an extended Azorean family harboring a mutation of the THRB gene (Fig. 1). This selected population is unique because all individuals share a similar genetic background and have been exposed to similar environmental conditions since they all live on the same small island. Goiter and mild tachycardia are the most common clinical manifestations of the disorder in affected individuals who are otherwise euthyroid despite high serum TH levels (5).

FIG. 1.

More than 200 members of this family with RTHβ spanning six generations were identified. They were traced to a late 19th-century founder couple that served as the progenitor of 68 nuclear families. Family members belonging to the sixth generation are not drawn in this tree because it would increase the size of the figure behind acceptable limits. Furthermore, none of these individuals were included in the present study due to their young age (younger than 18 years). RTHβ, resistance to thyroid hormone beta.

The THRB gene mutation identified in this family results in the substitution of glycine for arginine at position 243 (R243Q) of TRβ (6) and has been found in several other unrelated families (7). It is located in the “hinge” region of the THRB and involves a CpG hot spot. Only one homozygous individual has been reported to date (8). In vitro studies have revealed that the R243Q-mutant TRβ exhibits normal triiodothyronine (T3) binding in solution. However, when bound to DNA, T3-dependent dissociation of the mutant receptor homodimers or the release of a corepressor is markedly impaired due to reduction of the receptor affinity for T3 only after it binds to DNA. This suggests that the receptor DNA-binding domain can modulate the function of the hormone-binding domain via allosteric mechanisms (9).

Materials and Methods

Adult individuals harboring the R243Q (Arg243→Gln) mutation and their wild-type (WT) first-degree relatives who all lived on São Miguel island, the Azores (Portugal), were invited to participate in this study. All affected individuals belonging to the Azorean family were heterozygous for the mutation. The following exclusion criteria were applied: the presence of chronic liver disease, alcohol abuse (drinking habits of more than 20 g of alcohol/day in females and 30 g of alcohol/day in males), or the use of known steatogenic drugs. This work was approved by the internal review board of Hospital Divino Espirito Santo. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical and biochemical parameters were collected and recorded in a database created for this study. Serum measurements included hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelet count, albumin, fasting glucose, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides. Free triiodothyronine (fT3), free thyroxine (fT4), thyrotropin (TSH), and insulin were measured by a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (ARCHITECT; Abbott). Serum concentrations of glucose and insulin were used to calculate the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) scores with the following equation: fasting insulin [μU/mL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL]/405 (10). Serum levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) were measured with an enzymatic fluorometric assay (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

We used the ultrasound-based transient elastography (TE) device (FibroScan; Echosens, France) with estimation of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) to assess the hepatic fat content. The TE device consists of an ultrasound source (3.5 MHz) mounted in the axis of a vibrator that generates vibration-induced elastic shear waves. The velocity of propagation of the shear waves across the liver is a marker of liver stiffness and is expressed in kilopascals (kPa) (11). The normal range in healthy livers is 2.5–7.5 kPa (12). The CAP algorithm calculates the decrease in the amplitude of the ultrasound wave travelling in the liver. CAP values are expressed in decibels per meter (dB/m) and have been shown to correlate well with biopsy-proven steatosis (13). A CAP value >240 dB/m has demonstrated a high sensitivity for detecting hepatic steatosis, which is defined as the presence of lipid vacuoles in more than 5% of hepatocytes (14). Furthermore, cutoff values for CAP have been proposed to grade the severity of hepatic steatosis (15,16).

The TE measurements in the present study were obtained after an overnight fast by the same observer who was blinded to the status of the participants. The probe was placed on the right lobe of the liver through the intercostal spaces with the patient lying in the decubitus position and with the right arm in maximal abduction. The CAP value was calculated only if the liver stiffness measurements were reliable to ensure accurate attenuation. The final CAP result was obtained as a median of at least 10 measurements. The procedure was deemed a failure if 10 valid measurements could not be obtained, if the percentage of valid measurements compared with the total number of measurements was <60%, and/or if the interquartile range exceeded 30% of the median. Unsuccessful measurements, that is, those not validated by the algorithms of the device, were automatically rejected, and the message “invalid measurement” was displayed on the monitor.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the software IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 for Windows. Descriptive statistics are summarized as means and standard deviations, and counts and percentages were used for categorical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to test for normality of numerical variables. The two-tailed t-test for independent samples was used to test continuous data with a normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed for continuous non-normally distributed variables in cases with two independent groups. Pearson's correlation was used to study the relationship between two variables that were normally distributed. Multivariate logistic regression models were performed to assess the independence of the correlated variables. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Twenty-three individuals harboring the R243Q (Arg243→Gln) mutation in the THRB gene and 25 WT first-degree relatives were recruited. Five individuals were excluded: three because of alcohol abuse, one who was treated with tamoxifen due to previous breast cancer, and one individual with epilepsy who was medicated with carbamazepine. Twenty-one affected individuals and 22 WT relatives were therefore enrolled in the present study. CAP measurements were successfully obtained for all included individuals. There were no significant differences in age (RTHβ: 36 ± 11 years; WT: 34 ± 9 years; mean ± SD) or body mass index (BMI) (RTHβ: 21.9 ± 3.6 kg/m2; WT: 23.8 ± 6.1 kg/m2) between individuals with RTHβ and WT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Parameters of Study Participants

| RTHβ patients (R243Q) (n = 21) | WT first-degree relatives (n = 22) | p-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 36 ± 11 (18–55) | 34 ± 9 (18–60) | 0.72 |

| Sex, M/F | 12/9 | 10/12 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.9 ± 3.6 (14.8–31.2) | 23.8 ± 6.1 (18.1–44.1) | 0.06 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 133 ± 13 (101–143) | 131 ± 8 (103–138) | 0.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 81 ± 6 (79–91) | 80 ± 5 (76–89) | 0.7 |

| Heart rate, beats per minute | 88 ± 8 (74–106) | 78 ± 6 (61–91) | 0.04 |

| TSH, mIU/L (0.35–4.94) | 2.4 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 0.5 |

| fT4, ng/dL (0.70–1.48) | 1.98 ± 0.52 | 1.12 ± 0.32 | 0.004 |

| fT3, pg/mL (1.71–3.71) | 6.12 ± 1.68 | 3.10 ± 0.68 | 0.04 |

| SHBG, nmol/L (20–130) | 49.9 ± 17 | 54 ± 13 | 0.8 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L (46–149) | 114.7 ± 55 | 101.7 ± 65 | 0.09 |

| Liver aminotransferase, ALT, IU/L (10–49) | 43 ± 29 | 34 ± 23 | 0.1 |

| Liver aminotransferase, AST, IU/L (<34) | 31 ± 19 | 29 ± 25 | 0.5 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL (0.4–1.2) | 0.62 ± 0.16 | 0.52 ± 0.21 | 0.9 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, IU/L (<68) | 32 ± 19 | 37 ± 15 | 0.6 |

| Platelet count × 103 (150–400) | 217 ± 32 | 227 ± 29 | 0.09 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD; the range is indicated in parentheses.

Level of significance, p < 0.05.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine; RTHβ, resistance to thyroid hormone beta; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; TSH, thyrotropin; WT, wild type.

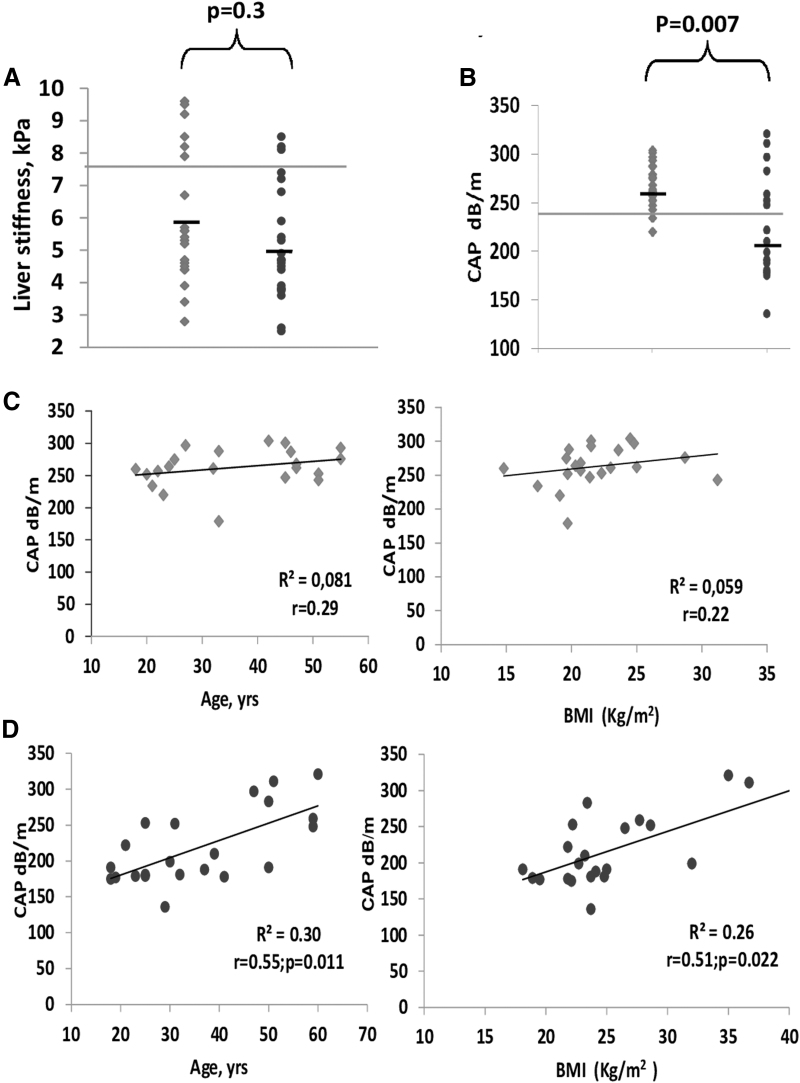

Patients with RTHβ and WT relatives had no differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but patients with RTHβ had increased resting heart rate (88 ± 8 vs. 78 ± 6 beats per minute; p = 0.04). There were no significant differences in serum TSH levels; however, serum fT4 and fT3 levels were higher than the upper limits of the reference range in individuals with RTHβ compared with the WT relatives (1.98 ± 0.52 ng/dL vs. 1.12 ± 0.32 ng/dL, p = 0.01; and 6.12 ± 1.68 pg/mL vs. 3.10 ± 0.68 pg/mL, p = 0.02, respectively). The mean values of liver stiffness assessed by TE were similar in both groups (5.8 ± 2.1 and 5.1 ± 1.65 kPa, p = 0.3) (Fig. 2A). Conversely, the hepatic fat content estimated by CAP measurements was significantly higher in RTHβ individuals (263 ± 21 dB/m) compared with their WT relatives (218.7 ± 43 dB/m; p = 0.007) (Fig. 2B). Next, we investigated the association of CAP with known correlated factors (age and BMI). One BMI value that was >40 kg/m2 was considered an outlier and was removed from the calculations. Without this outlier, BMI was also normally distributed in the WT relatives. CAP values were positively correlated with age and BMI in the WT group (age: r = 0.55, p = 0.011; BMI: r = 0.51, p = 0.022) but not in the RTHβ individuals (age: r = 0.29, p = 0.3; BMI: r = 0.22, p = 0.23) (Fig. 2C, D). No interaction was found between age and BMI, and the association remained independently correlated in the WT patients when tested in a multivariate model. We identified no influence of sex on CAP values (males, 261 ± 21 dB/m and females, 266 ± 32 dB/m [p = 0.68] in RTHβ individuals; males, 224 ± 45 dB/m and females, 216 ± 36 dB/m [p = 0.93] in the WT first-degree relatives).

FIG. 2.

(A) Values of liver stiffness obtained by TE in 21 (square) RTHβ individuals and 22 (circle) WT relatives. The difference between the means was not significant. Notably, 6 of 21 RTHβ individuals (28.6%) presented levels >7.5 kPa (upper limit of normal indicated by a horizontal line in this panel) compared with only 3 of 22 (13.6%) in the WT relatives (11,12). (B) The CAP values were significantly higher in the RTHβ individuals compared with those measured in their first-degree relatives (t-test; p < 0.007). CAP values >240 dB/m are very sensitive for hepatic steatosis (13,14). This cutoff is indicated in the panel as a horizontal line. (C) Age and BMI were not correlated (linear regression) with CAP values in individuals with RTHβ, indicating that loss of TRβ signaling is a strong and independent risk factor of hepatic steatosis. (D) In the WT first-degree relatives without impaired TRβ signaling, the CAP values were correlated (linear regression) with age and BMI (one outlier BMI value of >40 kg/m2 was removed). Both correlations remained significant after adjustment for BMI and age, respectively. BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; TE, transient elastography; TRβ, thyroid hormone receptor beta; WT, wild type.

Both groups had a similar lipid profile, except that HDL cholesterol was significantly lower in RTHβ individuals (RTHβ: 40 ± 8 mg/dL; WT: 52 ± 10 mg/dL; p = 0.009) (Table 2). Serum levels of FFAs were significantly higher in RTHβ individuals compared with their WT relatives (0.29 ± 0.033 and 0.17 ± 0.025 mmol/L, respectively, p = 0.02). Insulin, glycemia, and HOMA-IR were within the normal ranges and showed no significant differences between the two groups. We analyzed serum liver function tests and found that alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase were within the normal ranges for both groups and did not differ significantly. Platelet counts also did not differ significantly between the two groups. Finally, serum levels of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) were similar in both groups (49.9 ± 17 and 54.7 ± 18 nmol/L [p = 0.8] in RTHβ individuals and WT first-degree relatives, respectively).

Table 2.

Serum Lipids and Glucose Homeostasis

| RTH patients (R243Q) (n = 21) | WT first-degree relatives (n = 22) | p-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (<190 mg/dL) | 165 ± 27 | 175 ± 30 | 0.24 |

| HDL cholesterol (>40 mg/dL) | 40 ± 8 | 52 ± 10 | 0.009 |

| LDL cholesterol (<115 mg/dL) | 103 ± 16 | 113 ± 29 | 0.140 |

| Triglycerides (30–150 mg/dL) | 115 ± 45 | 108 ± 43 | 0.355 |

| Free fatty acids (0.09–0.060 mmol/L) | 0.29 ± 0.033 | 0.17 ± 0.025 | 0.02 |

| Fasting glycemia (74–106 mg/dL) | 90 ± 10 | 85 ± 7.0 | 0.058 |

| HbA1c (3.8–5.8%) | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Fasting insulin (5–10 mU/L) | 6.6 ± 2.9 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 0.4 |

| HOMA-IR (0.4–2.6) | 1.84 ± 1.3 | 1.45 ± 0.73 | 0.66 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD; the range is indicated in parentheses.

Level of significance, p < 0.05.

HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

We used a noninvasive assessment of hepatic steatosis to demonstrate that patients with RTHβ exhibit an increase in intrahepatic fat content compared with their WT relatives. This finding demonstrates the importance of TRβ-dependent signaling in hepatic lipid metabolism in humans. Previously, several clinical studies have shown that hypothyroid patients have an increased risk of NAFLD (17–21). Additionally, major genes altered in the liver biopsies of morbidly obese patients were found to be TH-responsive (22). Furthermore, knock-in mutant mice harboring a dominant negative mutation in the THRB gene that mimics the RTHβ phenotype in humans developed enlarged livers with hepatic steatosis early in life (23). This mouse model of RTHβ demonstrated an increase in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) signaling and downstream targets regulating lipogenesis, similar to what was noted in hypothyroid mice. However, T3 decreased PPARγ mRNA to control levels only in hypothyroid mice. This serves as an indication that the same T3-responsive pathways are involved in hypothyroidism and in mutant TRβPV mice. Therefore, both situations resulted in reduced TRβ signaling either due to the decreased availability of TH (hypothyroidism) or due to a mutation in the receptor (RTHβ). The absence of a significant difference between serum SHBG levels in the two groups is not surprising (Table 1). In fact, basal SHBG is not a peripheral marker of TH action sensitive enough to differentiate normal individuals from patients with hypothyroidism and RTHβ individuals (24,25).

NAFLD has increasingly become a serious clinical concern because of its severe morbidity and potential progression to end-stage liver disease, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. NAFLD has a current global prevalence of ∼25% in the adult population (26). In our study, 85% (18 of 21) of RTHβ individuals had CAP values >240 dB/m, which is the commonly accepted cutoff point for hepatic steatosis (more than 5% of the liver is composed of fat cells) (13,14); conversely, only 32% (7 of 22) of the WT first-degree relatives had CAP values >240 dB/m. CAP measurements were found to be positively correlated with age and BMI in the WT relatives. However, this age- and BMI-dependent increase in intrahepatic fat content was not demonstrated in RTHβ individuals, indicating that the defect in TRβ signaling was predominant over the effects of age and obesity in determining hepatic steatosis in these individuals.

Fasting insulin levels and HOMA-IR did not differ significantly between the groups. These findings suggest that insulin resistance was not a major determinant of hepatic steatosis in RTHβ individuals as it is in other conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Thus, impairment in TH and TRβ signaling appears to be an independent and significant cause of hepatic steatosis in these patients, further supporting the role of TH in the hepatic metabolism of lipids. There is a well-known decline in the serum levels of TH, particularly of fT3, with aging (27,28). However, we did not identify a significant correlation between serum levels of TH and CAP values in individuals with and without TRβ impairment. Therefore, the hypothesis that the age-dependent increase in the hepatic fat content in the WT relatives would be related to a decrease in TH levels seems improbable.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no publications reporting measurements of hepatic fat in RTH patients harboring other mutations. In terms of lipid metabolism, Mitchell et al. (29) investigated 55 patients with different heterozygous TRβ mutations. Overall, the group had increased FFA levels (p < 0.01), decreased HDL cholesterol (p = 0.01), and unchanged total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. This is similar to our data showing increased FFAs, decreased HDL cholesterol, and no change in other lipid parameters. The significant increase in serum FFA levels exhibited in RTHβ individuals and also reported by others (29) may reflect a decrease in the clearance of FFAs by the liver where the regulation of FFAs transporters is dependent on TH (30). Intrahepatic catabolic actions of TH in lipids are primarily mediated by the mobilization of FFAs from triacylglycerol stored in fat droplets by autophagy (lipophagy) and hepatic lipases (31). The intracellular FFAs subsequently undergo β-oxidation within the mitochondria. The rate-limiting process of β-oxidation is regulated by TH (32). Therefore, the loss of TRβ signaling in RTHβ individuals leads to the accumulation of fat in the liver, most likely due to the impaired beta-oxidation of FFAs, which is dependent on multiple TH-regulated processes such as lipophagy, lipase activity, and mitochondrial function.

Adipose tissue is an important target of TH. All the isoforms of TR receptors (TRα-1, TRα-2, and TRβ-1) are present in white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT), but TRα-1 is more abundantly expressed and plays a predominant role in the obligatory thermogenesis and sympathetic response, whereas TRβ may play a more significant role in stimulating uncoupled protein 1 (Ucp1) expression in the BAT (33). TRα is also crucial in the generation and maintenance of the mature adipocyte phenotype and regulates the expression of lipogenic enzymes (34). Therefore, TRα overactivity induced by increased levels of TH in RTHβ may alter the lipid pattern of affected individuals by increasing lipolysis from fat stores in WAT and from dietary fat sources to generate circulating FFAs, which are the major source of lipid for the liver (35).

The CAP is a noninvasive quantitative marker of hepatic steatosis (14). Liver biopsy is considered the “gold standard” in the assessment of hepatic steatosis; however, it has limitations since fat accumulation may be focal and avoiding sampling errors remains a major challenge. Furthermore, liver biopsy is an invasive procedure, with a risk of complications that is not negligible. CAP, a noninvasive and low-cost procedure, allowed us to demonstrate for the first time in humans that similar to mice, individuals with RTHβ exhibited an increase in intrahepatic fat content compared with their WT relatives.

Although we found that RTHβ individuals had increased hepatic steatosis compared with their WT relatives, there was no significant difference in liver stiffness measured by TE (Fig. 2A). This lack of difference in liver stiffness measurements between the two groups could be due, at least partially, to the relatively young age of the individuals enrolled in the present study because more time may be required to develop hepatic fibrosis. Nevertheless, although the mean levels of liver stiffness did not differ significantly between the two groups, it is noteworthy that 6 of 21 RTHβ individuals (28.6%) presented levels >7.5 kPa (upper limit of normal) compared with only 3 of 22 (13.6%) in the WT relatives. Therefore, the risk of progression from hepatosteatosis to hepatic fibrosis associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) appears to be increased in RTHβ individuals. In this sense, affected individuals should be monitored regularly through noninvasive examinations such as TE. Furthermore, NASH and hepatic cirrhosis may ultimately be the consequence of a complex process in which many factors, including genetic susceptibility and environmental toxicants, in addition to hepatic steatosis, may play important roles (36,37).

In conclusion, our results show that similar to earlier findings in rodents, impairment in intrahepatic TH and TRβ signaling can lead to hepatosteatosis. These findings emphasize the rationale for the development of thyromimetics to treat lipid-associated hepatic disorders, particularly NAFLD. Although the effects of TH on the heart and bones are mainly connected to TRα, TRβ is the predominant isoform of TR in the liver; therefore, much effort has been directed toward the design of thyromimetics with a very high TRβ affinity and hepatic selectivity to treat lipid-associated hepatic disorders such as NAFLD without generating cardiac toxicity or accelerating bone loss.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family members for their willingness to participate in this study.

Authors' Contributions

S.R., P.Y., E.B., and J.A. conceived the study. J.A. and C.C. participated in the design and coordination of the study. E.B. and C.C. drafted the article. All the authors read and approved the final text.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

S.R. is supported by grant DK15070 from National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1. Sinha RA, Bruinstroop E, Singh BK, Yen P 2019. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypercholesterolemia: roles of thyroid hormones, metabolites, and agonists. Thyroid 29:1173–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mantovani A, Nascimbeni F, Lonardo A, Zoppini G, Bonora E, Mantzoros CS, Targher G 2018. Association between primary hypothyroidism and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 28:1270–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bruinstroop E, Dalan R, Cao Y, Bee YM, Chandran K, Cho LW. 2018. Low-dose levothyroxine reduces intrahepatic lipid content in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and NAFLD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103:2698–2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CG, Zhou R, Moylan CA, Frias JP, Alkhouri N, Bansal MB 2019. Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 394:2012–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anselmo J, Cao D, Karrison T, Weiss R, Refetoff S 2004. Fetal loss associated with excess thyroid hormone exposure. JAMA 292:691–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anselmo J, Kay T, Dennis K, Szmulewitz R, Refetoff S, Weiss RE. 2001. Resistance to thyroid hormone does not abrogate the transient thyrotoxicosis associated with gestation: report of a case. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:4273–4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Onigata K, Yagi H, Sakurai A, Nagashima T, Nomura Y, Nagashima K, Hashizume K, Morikawa A. 1995. A novel point mutation (R243Q) in exon 7 of the c-erbA beta thyroid hormone receptor gene in a family with resistance to thyroid hormone. Thyroid 5:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moran C, Habeb AM, Kahaly GJ, Kampmann C, Hughes M, Marek J, Rajanayagam O, Kuczynski A, Vargha-Khadem F, Morsy M, Offiah AC, Poole K, Ward K, Lyons G, Halsall D, Berman L, Watson L, Baguley D, Mollon J, Moore AT, Holder GE, Dattani M, Chatterjee K. 2017. Homozygous resistance to thyroid hormone β: can combined antithyroid drug and triiodothyroacetic acid treatment prevent cardiac failure? J Endocr Soc 8:1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yagi H, Pohlenz J, Hayashi Y, Sakurai A, Refetoff S. 1997. Resistance to thyroid hormone caused by two mutant thyroid hormone receptors beta, R243Q and R243W, with marked impairment of function that cannot be explained by altered in-vitro 3,5,3′- triiodothyronine binding affinity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1608–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD, Follmann DA, Sullivan G, Quon MJ. 2000. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2402–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. 2008. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol 48:835–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cobbold JL, Taylor-Robinson SD. 2008. Liver stiffness values in healthy subjects: implications for clinical practice. J Hepatol 48:529–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ledinghen V, Vergniol J, Capdepont M. 2014. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) for the diagnosis of steatosis: a prospective study of 5323 examinations. J Hepatol 60:1026–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eddowes PJ, Sasso M, Allison M, Tsochatzis Anstee QM, Sheridan D, Guha IN, Cobbold JF, Deeks JJ, Paradis V, Bedossa P, Newsomet PN. 2019. Accuracy of FibroScan. Controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement in assessing steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 156:1717–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eun YE, Jung KE, Kim KG, Joo DJ, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han K-W, Kim SU. 2015. Normal controlled attenuation parameter values: a prospective study of healthy subjects undergoing health checkups and liver donors in Korea. Dig Dis Sci 60:234–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Runge JH, Smith LP, Verheij J, Depla A, Kuiken SD, Baak BC, Nederveen AJ, Beurs U, Stroker J. 2018. MR spectroscopy-derived proton density fat fraction is superior to controlled attenuation parameter for detecting and grading hepatic steatosis. Radiology 266:547–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim D, Kim W, S Joo SK, Bae JM, Kim JH, Ahmed A. 2018. Subclinical hypothyroidism and low-normal thyroid function are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 16:123–131.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, Yim JY, Park MJ, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS. 2012. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol 57:150–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrandino G, Kaspari RR, Spadaro O, Reyna-Neyra A, Perry RJ, Cardone R, Kibbey RG, Shulman GI, Dixit VD, Carrasco N. 2017. Pathogenesis of hypothyroidism-induced NAFLD is driven by intra- and extrahepatic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E9172–E9180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dalan R, Cao Y, Bee Y, Toh S-U, Velan S, Yen P, Ballestri S, Mantovani A, Nascimbeni F, Lugari S, Targher G. 2019. Pathogenesis of hypothyroidism-induced NAFLD: evidence for a distinct disease entity? Dig Liver Dis 51:452–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bano A, Chaker L, Plompen E, Hofman A, Dehghan A, Franco O, Janssen H, Murad S, Peeters RP. 2016. Thyroid function and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Rotterdam study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101:3204–3211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pihlajamäki J, Boes T, Kim EY, Dearie F, Kim BW, Schroeder J, Mun E, Nasser I, Park PJ, Bianco AC, Goldfine AB, Patti ME. 2009. Thyroid hormone-related regulation of gene expression in human fatty liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3521–3529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Araki O, Ying H, Zhu XG, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. 2009. Distinct dysregulation of lipid metabolism by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol Endocrinol 23:308–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sarne DH, Refetoff S, Rosenfield RL, Farriaux JP. 1988. Sex hormone-binding globulin in the diagnosis of peripheral tissue resistance to thyroid hormone: the value of changes after short term triiodothyronine administration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 66:740–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh BK, Yen P. 2017. A clinician's guide to understanding resistance to thyroid hormone due to receptor mutations in the TRα and TRβ isoforms. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 3:8–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marjor T, Moolla A, Cobbold JF, Hodson L, Tomlison JW. 2020. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: current concepts in etiology, outcomes, and management. Endocr Rev 41:66–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mariotti S, Franceschi C, Cossarizza A, Pinchera A. 1995. The aging thyroid. Endocr Rev 41:66–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peeters RP 2008. Thyroid hormones and aging. Hormones (Athens) 7:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mitchell CS, Savage DB, Dufour S, Schoenmakers N, Murgatroyd P, Befroy D, Halsall D, Northcott S, Raymond-Barker P, Curran S, Henning E, Keogh J, Owen P, Lazarus J, Rothman DL, Farooqi IS, Shulman GI, Chatterjee K, Petersen KF. 2010. Resistance to thyroid hormone is associated with raised energy expenditure, muscle mitochondrial uncoupling, and hyperphagia. J Clin Invest 120:1345–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sinha AR, BrijeshBK, Yen PM. 2018. Direct effects of thyroid hormones on hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat Rev 14:259–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ritter M, Amano I, Hollenberg A. 2020. Thyroid hormone signalling and the liver. Hepatology 72:742–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackson-Hayes L, Song S, Lavrentyev E, Jansen M, Hillgartner F, Tian L, Wood Ph, Cook G, Park E. 2003. A thyroid hormone response unit formed between the promoter and first intron of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase-Iα gene mediates the liver-specific induction by thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem 278:7964–7972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yay W, Yen P. 2020. Thermogenesis in adipose tissue activated by thyroid hormone. Int J Mol Sci 21:3020–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang W, Miyamoto T, Kakizawa T, Sakuma T, Nishio S-I, Takeda T, Suzuki S, Hashizume K. 2004. Expression of thyroid hormone receptor alpha in 3T3-L1 adipocytes; triiodothyronine increases the expression of lipogenic enzyme and triglyceride accumulation. J Endocrinol 182:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu, J, Han L, Zhu L, Yu Y. 2016. Free fatty acids, not triglycerides, are associated with non-alcoholic liver injury progression in high fat diet induced obese rats. Lipids Health Dis 15:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Satapathy SK, Sanyal AJ. 2015. Epidemiology and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 35:221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loomba R, Schork N, Chen C-H, Bettencourt R, Bahatt A, Ang B, Neguyen P, Hernadez C, Richards L, Saloti J, Lin S, Seki E, Nelson KE Sirlin CB and Brenner D. 2015. Heritability of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis based on a prospective twin study. Gastroenterology 149:1784–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]