Abstract

Introduction: With the unprecedented expansion of women's roles in the U.S. military during recent (post-9/11) conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the number of women seeking healthcare through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has increased substantially. Women Veterans often present as medically complex due to multiple medical, mental health, and psychosocial comorbidities, and consequently may be underserved. Thus, we conducted the nationwide Women Veterans Cohort Study (WVCS) to examine post-9/11 Veterans' unique healthcare needs and to identify potential disparities in health outcomes and care.

Methods: We present baseline data from a comprehensive questionnaire battery that was administered from 2016 to 2019 to a national sample of post-9/11 men and women Veterans who enrolled in Veterans Affairs care (WVCS2). Data were analyzed for descriptives and to compare characteristics by gender, including demographics; health risk factors and symptoms of cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, and mental health; healthcare utilization, access, and insurance.

Results: WVCS2 included 1,141 Veterans (51% women). Women were younger, more diverse, and with higher educational attainment than men. Women also endorsed lower traditional cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (e.g., weight, hypertension) and greater nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., trauma, psychological symptoms). More women reported single-site pain (e.g., neck, stomach, pelvic) and multisite pain, but did not differ from men in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms or treatment for PTSD. Women seek care at VHA medical centers more frequently, often combined with outside health services, but do not significantly differ from men in their insurance coverage.

Conclusion: Overall, this investigation indicates substantial variation in risk factors, health outcomes, and healthcare utilization among post-9/11 men and women Veterans. Further research is needed to determine best practices for managing women Veterans in the VHA healthcare system.

Keywords: Veterans, gender differences, risk factors, cardiovascular health, mental health, pain

Introduction

Women Veterans in the United States

In 1992, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) relaxed previous restrictions on occupational roles for women in the military. Since then, the population of women service members has grown rapidly, with women projected to represent one in five Veterans by 2045.1 As of 2015, women are eligible to participate in direct combat, and many other added duties in combat zones also expose women to uniquely hazardous and potentially traumatic situations (e.g., handling human remains2), increasing their risk of job-related stress and trauma.3

Physical burdens associated with military service, such as carrying heavy loads and working in dangerous terrain, also increase women's risk of musculoskeletal injury.4 In addition to the stress of combat exposure, women are at a sixfold greater risk of military sexual trauma (MST) than men.5 Trauma and injury associated with deployment likely affect women's health differently than men. Yet, the effects of women's service and deployment on their health and well-being after discharge, and how to best meet women's healthcare needs, require further study.

As the population of women military service members has increased, women's enrollment in services through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a component of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), has also risen dramatically—threefold since 2000.6 About 41% of women Veterans now use VA care, which is slightly lower than the percentage of male VA users (i.e., 46%).7

Women who served in Iraq and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF], Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF], and Operation New Dawn [OND]) are enrolling in the VA in record numbers and are also younger, more racially and ethnically diverse, and have attained higher levels of education and employment than their male counterparts or women Veterans in previous eras.8–10 Due to the rapid growth of the women Veterans population, the VHA, a system that has historically cared for a mostly male population, is challenged to understand the unique needs of women Veterans and to provide them with the highest quality care.

The Women Veterans Cohort Study

The Women Veterans Cohort Study (WVCS) was designed to address this gap in knowledge by identifying gender-associated disparities in health outcomes and healthcare utilization among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans cared for by the VA. The goals of WVCS were to assess the following: (i) patterns of disease onset and progression among men and women Veterans; (ii) unique psychiatric and psychosocial moderators of disease for women; (iii) unique care patterns and barriers for women Veterans; and (iv) women's healthcare utilization, costs, and satisfaction. WVCS included an electronic health record (EHR) cohort and a geographically representative survey cohort.

The first WVCS (WVCS1), referred to here as pilot, included data collection from 2008 to 2011 on men and women's military experiences, chronic disease, chronic pain, and trauma. In 2016, the survey was expanded in the second wave of WVCS (WVCS2) to include questions on conditions that have different or unique manifestations in women: cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and mental health outcomes, and healthcare experiences. In this report, we provide baseline parameters from WVCS2 survey data, put those findings in context with other results, and describe the strengths and limitations of this resource.

Methods

Study sites and eligibility

The WVCS2 Survey Cohort was derived from the DoD's OEF/OIF/OND Roster, which is shared with the VHA through the Contingency Tracking System. This roster includes Veterans who were discharged from military service and who enrolled with the VHA from October 1, 2001 (the start of U.S. operations in Afghanistan) through December 31, 2018. Veterans who were members of this cohort and who received care at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, and at VA facilities in Indianapolis, IN, Durham, NC, Los Angeles, CA, and Northampton, MA were recruited to participate in the WVCS2 survey. Inclusion criteria were English literacy and affirmation of OEF/OIF/OND participation. VA Institutional Review Boards approved study procedures.

Recruitment and enrollment

From participating sites, all women Veterans and a random sample of men (at a ratio of three women to two men) who met eligibility criteria were mailed an invitation to participate, consent documents, and a paper version of the baseline survey (n = 4,729), with enrollment occurring from February 11, 2016 to October 28, 2019. Women were oversampled to ensure similar percentages of men and women. Mailings were resent up to three times if there was no response. Veterans who completed consent and the baseline survey were invited to complete one annual follow-up survey. Veterans received $20 for returning each survey.

WVCS2 survey

The survey included questions concerning demographics, military service (e.g., number of deployments, injuries, combat exposure), health risk factors (e.g., smoking, exercise), trauma (e.g., MST), coping (e.g., social support), recent symptoms of pain (e.g., Have you had pain or discomfort for over 3 months and pain sites [e.g., back, abdominal, pelvic]), insomnia, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and alcohol and drug use. Other questions were used to collect a detailed history of chronic pain and musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular risk factors and knowledge, and mental health and related treatment.

Participants also reported if they had received medical treatment in the last 12 months, how many times they received treatment, and what conditions they had received treatment for (e.g., severe chronic pain, high blood pressure, depression). Questions also addressed women's reproductive needs, preferences for care, and experiences with VA reproductive care. All questionnaires were previously validated in Veteran samples. See Table 1 for an abbreviated list of WVCS2 content domains and measures presented in this article.11–30

Table 1.

Selection of Content Domains, Variables, and Measures from the WVCS2 Baseline Survey

| Domains | Survey data |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Current age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, recent residences, employment, income |

| Military service | Deployment and service history, injuries during service Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory-2 (DRRI-2): Training and Preparation for Deployment and Unit Support Subscales11 Combat Exposure Scale (CES12) |

| Medical comorbidities | Health conditions following deployment |

| Health characteristics and behaviors | Height and weight, smoking Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-1213,14) Leisure time exercise Insomnia Severity Index (ISI15) |

| Pain | Recent symptoms and treatment, chronic pain, and specific sites of pain Brief Pain Inventory (BPI16) |

| Cardiovascular health | Recent symptoms and treatment Risk factors and likelihood of experiencing risk factors, heart disease and prevention knowledge, barriers to a heart healthy lifestyle17–21 |

| Mental health | Recent treatment Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-822) Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-723) PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M24) |

| Substance use | Recent treatment Drug Abuse Screening Test 10 (DAST-1025) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C26) |

| Trauma | Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ27) Extended-Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream (E-HITS28) |

| Coping | Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey29 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)30 |

| Healthcare access, utilization, and insurance | Healthcare utilization since returning from most recent deployment, perceptions of VA healthcare and benefits Use of VA and non-VA healthcare, health insurance |

PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; VA, Veterans Affairs medical centers; WVCS2, Women Veterans Cohort Study survey cohort.

Healthcare utilization, access, and insurance

Participants reported about their healthcare utilization, access, and insurance status during the previous 12 months. Questions included the following: “How many times have you seen a healthcare provider for any reason, such as in primary care, family doctor, emergency room, or mental health provider?” “Have you been seen by VA providers only, non-VA providers, or VA and non-VA providers?” “Was any non-VA care paid for by the VA?” “Do you plan to use the VA for healthcare in the future?” and, “How many times have you used the following health services outside the VA in the past 12 months: a general practitioner; outpatient care (clinic or emergency room), overnight stays in a hospital or nursing home; a psychiatrist; a psychologist, professional counselor, marriage therapist, or social worker; a minister, priest, rabbi, or other spiritual advisor)?” Other questions pertained to whether the Veteran had any health insurance in the past year and what type of insurance (private [e.g., employer-sponsored] or public [e.g., Medicare]).

Statistical analysis

Means, standard deviations, percentages, and 95% confidence intervals were computed from individual items and validated survey measures. Bivariate associations were examined using t-tests for continuous variables, and Fisher's exact test or the chi-square test for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess covariate-adjusted gender differences in survey responses. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to compare the response percentages between men and women (using men as the referent group). A priori covariates included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), service branch and component, and number of deployments. All analyses were performed using SAS V9.4, with p < 0.05 (two-sided) indicating statistical significance.

Results

Survey response

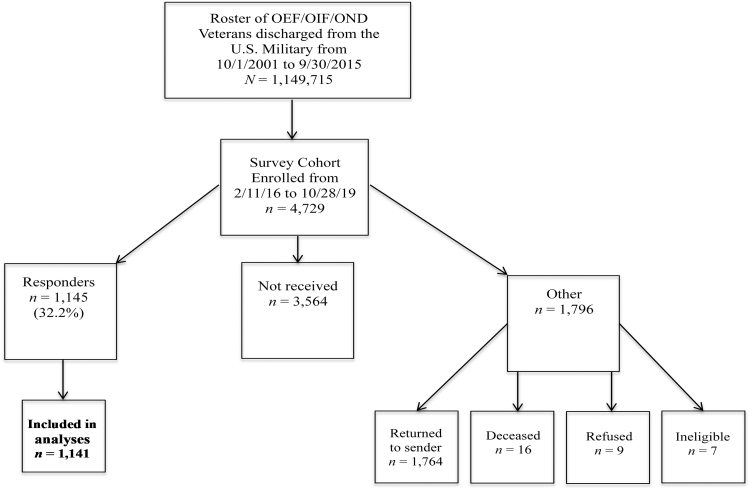

Of the 4,729 Veterans who were recruited, 1,145 surveys were completed, for a response rate of 32.2% (Fig. 1). Four individuals did not provide information concerning gender and were excluded from these results, leaving n = 1,141 (51.4% women). Relative to nonresponders, responders were less likely to be racial/ethnic minorities (34.4% vs. 22.4%), were significantly older (40.0 vs. 43.8 years), more likely to be women (44.7% vs. 51.4%), to have participated in active duty (17.6% vs. 39.1%), and to have served in the Coast Guard, Navy, or Marines (32.9% vs. 39.7%) rather than in the Army (all p < 0.001).

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of recruitment for the Women Veterans Cohort Study survey cohort (WVCS2), consisting of men and women who participated in Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND).

Demographic characteristics, military service, health risk factors, and coping

Detailed sociodemographic and health characteristics of the WVCS2 survey cohort are displayed in Table 2. Participants were 44 years old on average, and women were significantly younger than men (41.6 vs. 46.2, p < 0.001). Most participants identified as White, non-Hispanic, but the sample of women had a greater percentage of racial/ethnic minorities than men (25% vs. 18%, p = 0.03). More women than men had at least an Associate degree (85% vs. 72%), but also reported a lower personal income (e.g., <$50,001 among 62% of women vs. 49% of men), and a lower percentage of women owned their residence relative to men (78% vs. 83%, all p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the WVCS2 Survey Cohort, 2016–2019

| Total (N = 1,141)a | Women (n = 586) | Men (n = 555) | p-Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 43.8 ± 10.9 | 41.6 ± 10.3 | 46.2 ± 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.03 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 851 (74.5) | 425 (72.5) | 426 (76.8) | |

| Black | 97 (8.5) | 61 (10.7) | 36 (6.8) | |

| Hispanic | 90 (7.9) | 50 (8.5) | 40 (7.2) | |

| Mixed/other | 58 (5.1) | 34 (5.8) | 24 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 45 (3.9) | 16 (2.7) | 29 (5.2) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 636 (55.7) | 272 (46.4) | 364 (65.6) | |

| Divorced/separated | 227 (20.2) | 139 (23.8) | 88 (15.9) | |

| Single | 271 (23.8) | 169 (29.0) | 102 (18.4) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Less than or equal to high school/GED | 234 (20.8) | 85 (14.6) | 149 (27.2) | |

| Associate degree/2-year college | 269 (23.8) | 145 (24.9) | 124 (22.7) | |

| Bachelor's degree/4-year college | 357 (31.6) | 208 (35.7) | 149 (27.2) | |

| Graduate/professional degree | 269 (23.8) | 144 (24.7) | 125 (22.9) | |

| Employment | <0.001 | |||

| Employed | 800 (70.1) | 399 (68.1) | 401 (72.3) | |

| Unemployed | 100 (8.8) | 41 (7.0) | 59 (10.6) | |

| Student | 128 (11.2) | 93 (15.9) | 35 (6.3) | |

| Retired | 171 (15.0) | 72 (12.3) | 99 (17.8) | |

| Personal income | <0.001 | |||

| $0 | 141 (12.4) | 88 (15.1) | 53 (9.6) | |

| $1–$25,000 | 203 (17.8) | 128 (22.0) | 75 (13.6) | |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 290 (25.4) | 146 (25.0) | 144 (26.2) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 235 (20.6) | 117 (20.1) | 118 (21.5) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 130 (11.4) | 54 (9.3) | 76 (13.8) | |

| >$100,000 | 104 (9.1) | 33 (5.6) | 71 (12.9) | |

| Residence | <0.001 | |||

| Owned apartment or house | 853 (80.2) | 423 (77.8) | 430 (82.9) | |

| Rented room, apartment | 218 (26.0) | 131 (28.9) | 87 (22.6) | |

| Other (with family, shelter, street, rehab) | 92 (10.9) | 50 (9.2) | 42 (8.1) | |

| Military service | ||||

| Branch | <0.001 | |||

| Army | 693 (60.7) | 361 (61.6) | 332 (59.8) | |

| Air force | 187 (16.4) | 110 (18.8) | 77 (13.9) | |

| Navy | 158 (13.8) | 82 (14) | 76 (13.7) | |

| Marines | 82 (7.3) | 26 (4.4) | 56 (10.1) | |

| Component | 0.01 | |||

| Active duty | 443 (39.1) | 230 (39.2) | 213 (38.8) | |

| National guard | 363 (31.8) | 164 (27.9) | 199 (35.9) | |

| Reserves | 302 (26.5) | 172 (29.3) | 130 (23.4) | |

| Service history | ||||

| Number of deployments | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.7 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Combat exposure (CES) | 10.6 ± 9.7 | 8.0 ± 8.4 | 13.4 ± 10.2 | <0.001 |

| Preparation for deployment (DRRI-2) | 50.58 ± 11.7 | 50.0 ± 11.9 | 51.2 ± 11.5 | 0.10 |

| Unit support (DRRI-2) | 41.76 ± 12.8 | 39.9 ± 13.7 | 43.3 ± 11.5 | <0.001 |

| Physical injury related to deployment | 697 (61.1) | 335 (57.9) | 362 (65.9) | 0.005 |

| Physical injury during other duties | 566 (49.6) | 285 (49.2) | 281 (50.9) | 0.57 |

| Health risk factors and coping | ||||

| Smoking status | 0.39 | |||

| Current | 699 (14.8) | 88 (14.4) | 81 (14.6) | |

| Former | 361 (31.6) | 176 (30.2) | 185 (33.3) | |

| Never | 611 (53.6) | 322 (55.3) | 289 (52.1) | |

| Exercise | 0.03 | |||

| Often | 435 (39.1) | 208 (36.5) | 227 (41.8) | |

| Sometimes | 442 (39.7) | 224 (39.3) | 218 (40.2) | |

| Never/rarely | 236 (21.2) | 138 (24.2) | 98 (18.1) | |

| BMIc | <0.001 | |||

| Overweight | 437 (38.2) | 192 (33.2) | 244 (44.9) | |

| Obese | 411 (36.0) | 199 (34.4) | 212 (39.9) | |

| Trauma | ||||

| Lifetime trauma (TLEQ) | 23.4 ± 15.9 | 23.2 ± 15.4 | 23.7 ± 16.4 | 0.60 |

| Military sexual trauma | 352 (31.8) | 321 (56.5) | 31 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Intimate partner violence (E-HITS) | 375 (33.5) | 186 (32.4) | 189 (34.7) | 0.51 |

| Coping | ||||

| Social support (MOS) | 65.6 ± 27.6 | 64.6 ± 28.0 | 66.6 ± 27.2 | 0.21 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 27.1 ± 7.8 | 26.3 ± 8.0 | 28.0 ± 7.5 | <0.001 |

Most data are presented as n (%). All other data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Missing data: 0.3%–13.0%.

Bold values denote statistically significant differences.

BMI = 703 × weight (lbs)/[height (in)]2.

BMI, body mass index; CD-RISC, 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; CES, Combat Exposure Scale; DRRI-2, Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory-2; E-HITS, Extended-Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream; GED, General Educational Development degree; MOS, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey; TLEQ, Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire.

The degree of combat exposure was lower in women compared with their male counterparts (8.0 [“light exposure”] vs. 13.4 [“light-moderate exposure”], p < 0.001), as was perceived social support from fellow unit members and leaders, (39.9 vs. 43.3, p < 0.001), while a greater percentage of men experienced a physical injury related to deployment (58% vs. 66%; p = 0.005). Significantly more women reported a history of MST (57% vs. 6%; p = 0.03). Women reported less frequent exercise than men, but a significantly lower BMI (ps < 0.001–0.03). Finally, women Veterans reported significantly lower resilience (p < 0.001).

Health characteristics and recent medical treatment

Multivariate analyses are displayed in Table 3. Many respondents reported good or very good health (67%), but women endorsed significantly worse health than men (i.e., fair and poor health was reported by 28% of women vs. 23% of men; p = 0.02). Approximately 75% of Veterans endorsed current chronic pain lasting >3 months, with a higher prevalence of neck, headache/migraine, stomach/abdominal, and pelvic pain among women versus men (all p < 0.05). Significantly more women than men also endorsed chronic pain in multiple sites (63% vs. 57%; p = 0.02). Over one-third of Veterans reported sleep disturbances that met clinical criteria for insomnia (35%), with no significant gender difference.

Table 3.

Health Characteristics and Recent Medical Treatment Among the WVCS2 Survey Cohort

| Total (N = 1,141) | Women (n = 586) | Men (n = 555) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General health (VR-12) | 0.85 (0.69–1.06) | 0.14 | 0.74 (0.58–0.95) | 0.02 | |||

| Excellent | 85 (7.4) | 45 (7.7) | 40 (7.2) | ||||

| Very good | 335 (29.3) | 166 (28.4) | 169 (30.5) | ||||

| Good | 431 (38.1) | 211 (36.1) | 220 (39.7) | ||||

| Fair | 238 (20.8) | 129 (22.1) | 109 (19.7) | ||||

| Poor | 50 (4.4) | 34 (5.8) | 16 (2.9) | ||||

| Recent symptoms | |||||||

| Chronic pain in any sitea | 849 (74.5) | 436 (74.5) | 413 (74.4) | 0.99 (0.76–1.30) | 0.96 | 0.71 (0.54–1.06) | 0.11 |

| Back pain | 686 (83.8) | 351 (82.6) | 335 (85.0) | 1.20 (0.82–1.74) | 0.35 | 1.08 (0.69–1.69) | 0.73 |

| Neck pain | 507 (63.6) | 279 (66.6) | 228 (60.3) | 0.76 (0.57–1.02) | 0.07 | 0.69 (0.49–0.97) | 0.03 |

| Headache or migraine | 512 (64.4) | 299 (71.7) | 213 (56.4) | 0.51 (0.38–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.38–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Stomach or abdominal pain | 341 (43.6) | 204 (48.6) | 137 (37.7) | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | 0.002 | 0.64 (0.45–0.89) | 0.009 |

| Joint pain | 712 (85.6) | 359 (83.1) | 353 (88.3) | 1.53 (1.03–2.27) | 0.04 | 1.08 (0.68–1.70) | 0.76 |

| Chest pain | 160 (20.7) | 81 (19.9) | 79 (21.6) | 1.11 (0.79–1.57) | 0.55 | 1.15 (0.75–1.75) | 0.53 |

| Facial pain | 103 (13.5) | 61 (15.0) | 42 (11.7) | 0.75 (0.50–1.15) | 0.19 | 0.70 (0.43–1.17) | 0.43 |

| Pelvic pain | 167 (21.6) | 110 (26.5) | 57 (15.8) | 0.52 (0.37–0.75) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.31–0.72) | <0.001 |

| Pain across the entire body | 224 (28.8) | 126 (30.7) | 98 (26.7) | 0.82 (0.60–1.12) | 0.22 | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) | 0.18 |

| Chronic pain in multiple sites | 685 (60.3) | 370 (63.1) | 315 (56.8) | 0.67 (0.39–1.15) | 0.14 | 0.49 (0.26–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Insomnia (ISI) | 352 (35.1) | 176 (34.4) | 176 (35.8) | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) | 0.64 | 0.94 (0.70–1.27) | 0.69 |

| Depression (PHQ-8) | 338 (30.6) | 193 (33.9) | 145 (27.2) | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.67 (0.49–0.92) | 0.01 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 308 (27.7) | 179 (31.1) | 129 (24.0) | 0.70 (0.54–0.91) | 0.008 | 0.70 (0.51–0.97) | 0.03 |

| PTSD (PCL-M) | 398 (36.4) | 204 (36.4) | 194 (36.5) | 1.00 (0.79–1.29) | 0.97 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.97 |

| Alcohol use disorder (AUDIT-C) | 474 (42.3) | 229 (39.8) | 245 (44.7) | 1.22 (0.96–1.54) | 0.11 | 1.49 (1.12–1.98) | 0.006 |

| Drug abuse (DAST-10) | 37 (3.3) | 12 (2.1) | 25 (4.5) | 2.25 (1.12–4.52) | 0.02 | 2.80 (1.22–6.44) | 0.02 |

| Frequency of recent medical treatmentb | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | 0.15 | 0.60 (0.41–0.89) | 0.01 | |||

| No visits | 40 (3.5) | 13 (2.2) | 27 (4.9) | ||||

| 1–3 visits | 509 (44.8) | 228 (39.0) | 281 (50.8) | ||||

| 4+ visits | 588 (51.7) | 343 (58.7) | 245 (44.3) | ||||

| Recently treated conditionsb | |||||||

| Severe chronic pain | 427 (37.7) | 223 (38.3) | 204 (37.1) | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 0.67 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.41 |

| Migraine | 287 (25.4) | 177 (30.3) | 110 (20.1) | 0.58 (0.44–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) | 0.009 |

| Chronic sleep problems | 416 (36.8) | 213 (36.6) | 203 (37.0) | 1.02 (0.80–1.29) | 0.90 | 0.94 (0.70–1.26) | 0.67 |

| High blood pressure | 225 (19.9) | 83 (14.3) | 142 (25.8) | 2.08 (1.54–2.82) | <0.001 | 2.06 (1.41–3.03) | <0.001 |

| Other cardiac problems | 81 (7.2) | 40 (6.9) | 41 (7.5) | 1.09 (0.70–1.72) | 0.70 | 1.05 (0.60–1.84) | 0.87 |

| Diabetes | 77 (6.8) | 24 (4.2) | 53 (9.7) | 2.47 (1.50–4.06) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.26–4.57) | <0.001 |

| Depression/anxiety/emotional disorder | 493 (43.4) | 290 (49.7) | 203 (36.8) | 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.43–0.76) | <0.001 |

| PTSD | 416 (36.8) | 219 (37.6) | 197 (35.8) | 0.93 (0.73–1.18) | 0.53 | 0.90 (0.67–1.20) | 0.46 |

| Alcohol/drug abuse | 54 (4.8) | 23 (4.0) | 31 (5.6) | 1.45 (0.83–2.51) | 0.19 | 1.55 (0.79–3.05) | 0.20 |

Data are presented as n (%). Missing data: 0.6%–12.1%. Bold values denote statistically significant group differences.

Of those who reported chronic pain lasting >3 months.

In the last 12 months.

AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DAST-10, Drug Abuse Screening Test 10; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist-Military Version; PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire-8; VR-12, Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Clinically meaningful depression and anxiety symptom severity was endorsed by more than half of the cohort, and a greater percentage of women than men met criteria for major depressive disorder (34% vs. 27%, p = 0.01) and generalized anxiety disorder (31% vs. 24%, p = 0.03). Equivalent percentages of women and men reported clinically significant PTSD symptom severity (∼36% per group). Significantly fewer women than men met criteria for an alcohol use disorder (40% vs. 45%; p = 0.006) or drug abuse (2% vs. 5%; p = 0.02).

Most OEF/OIF/OND Veterans reported that they had received medical treatment in the past 12 months (97%). Over half of the sample made ≥4 medical visits in that period (52%), including a higher percentage of women than men (59% vs. 44%). About 38% of Veterans reported that they received medical treatment in the last year for severe chronic pain, with similar percentages by gender. Approximately 25% had been treated for migraines, which was more common among women (30% vs. 20%, p = 0.009). Thirty-seven percent of Veterans reported recent treatment for chronic sleep problems, with no differences by gender.

Twenty percent of Veterans reported recent treatment for high blood pressure, with fewer women reporting this treatment (18% vs. 34%, p < 0.001). Treatment for other cardiovascular conditions or diabetes was reported by 7% of Veterans, and compared to women, twice as many men reported diabetes treatment (4% vs. 10%, p < 0.001). Combined, treatment for depression, anxiety, or other emotional disorders was commonly reported (43%), with significantly more women reporting this than men (50% vs. 37%; p < 0.001). While PTSD treatment was less commonly reported (37%), women and men were equally likely to report recently receiving this treatment. Few Veterans endorsed receiving recent treatment for alcohol or drug abuse (5%), with no significant gender difference.

Healthcare utilization, access, and insurance

Data on healthcare utilization, access, and insurance are presented in Table 4. More than half of Veterans (54%) reported that they used both VA and non-VA providers, with more women reporting such utilization (57% vs. 51%, p < 0.001). Fewer Veterans reported that they received care exclusively through the VA (30%), while a greater percentage of women reported that they solely used non-VA providers (17% vs. 14%, p < 0.001). In addition, more women compared with men reported that they received non-VA care paid for by the VA (32% vs. 15%, p = 0.02).

Table 4.

Healthcare Utilization, Access, and Insurance from the WVCS2 Survey Cohort

| Total (N = 1,141) | Women (n = 586) | Men (n = 555) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of care | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 0.01 | 0.54 (0.41–0.71) | <0.001 | |||

| VA providers only | 331 (30.3) | 148 (25.9) | 181 (34.7) | ||||

| Non-VA providers only | 174 (15.8) | 99 (17.3) | 75 (14.4) | ||||

| VA and non-VA providers | 591 (53.8) | 325 (56.8) | 266 (51.0) | ||||

| Non-VA care paid for by the VA | 213 (28.8) | 131 (32.0) | 82 (14.8) | 0.71 (0.51–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.63 (0.43–0.94) | 0.02 |

| Future VA healthcare utilization | 1.19 (0.94–1.51) | 0.15 | 1.15 (0.86–1.52) | 0.34 | |||

| As a primary source of care | 719 (64.0) | 381 (65.6) | 338 (62.1) | ||||

| As a backup to non-VA care | 342 (30.3) | 173 (29.8) | 168 (30.9) | ||||

| For prescriptions only | 12 (1.1) | 5 (0.9) | 7 (1.3) | ||||

| No | 53 (4.7) | 22 (3.8) | 31 (5.7) | ||||

| Recent use of non-VA services | |||||||

| General practitioner | 594 (54.8) | 319 (57.6) | 275 (52.3) | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.67 (0.52–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Outpatient care | 469 (43.0) | 262 (46.7) | 207 (39.3) | 0.70 (0.55–0.88) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.47–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Overnight care | 91 (8.6) | 58 (10.6) | 33 (6.4) | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 0.01 | 0.43 (0.25–0.75) | 0.003 |

| Psychiatrist | 112 (10.3) | 68 (11.9) | 44 (8.6) | 0.69 (0.46–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | <0.001 |

| Psychologist, counselor, therapist | 182 (17.0) | 110 (19.9) | 72 (14.9) | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) | 0.17 | 0.77 (0.53–1.12) | 0.16 |

| Spiritual adviser | 77 (7.4) | 34 (6.3) | 43 (8.4) | 1.38 (0.87–2.21) | 0.01 | 1.63 (0.93–2.87) | 0.08 |

| Private health insurance | 668 (59.1) | 329 (57.0) | 338 (61.5) | 1.20 (0.95–1.53) | 0.13 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.97 |

| Type of private insurance | 0.38 (0.27–0.54) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.14–0.51) | <0.001 | |||

| Directly from the insurer | 46 (7.2) | 19 (6.0) | 27 (8.4) | ||||

| Through a current or former employer | 455 (71.5) | 199 (62.8) | 256 (80.0) | ||||

| Through a spouse or partner's current or former employer | 105 (16.5) | 82 (25.9) | 23 (7.2) | ||||

| Through government-related exchange (Affordable Care Act) | 21 (3.3) | 12 (3.8) | 9 (2.8) | ||||

| None/don't know | 10 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | ||||

| Government-provided health insurance | 671 (59.9) | 340 (59.1) | 331 (60.6) | 1.06 (0.84–1.35) | 0.61 | 0.84 (0.64–1.12) | 0.24 |

| Type of government insurance | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 0.80 | 1.22 (0.67–2.23) | 0.51 | |||

| Medicare | 70 (10.6) | 32 (9.6) | 38 (11.8) | ||||

| Medicaid or other health insurance based on financial need | 30 (4.6) | 19 (5.7) | 11 (3.4) | ||||

| CHAMPUS/TRICARE or other insurance programs for military personnel or Veterans | 509 (77.7) | 258 (77.3) | 251 (78.0) | ||||

| None/don't know | 47 (7.1) | 25 (7.5) | 22 (6.8) | ||||

| No health insurance in the past year | 82 (7.8) | 47 (8.6) | 35 (6.9) | 0.79 (0.50–1.24) | 0.30 | 1.30 (0.76–2.23) | 0.34 |

All data are presented as n (%). Missing data: 1.0%–8.0%. Bold values denote statistically significant group differences.

With regard to recent non-VA healthcare utilization (i.e., in the last 12 months), over half of the sample who reported using non-VA care saw a general practitioner (55%), and use of outpatient specialty care was also common (43%). Significantly more women than men used a non-VA general practitioner (58% vs. 52%, p = 0.002) or non-VA outpatient care (47% vs. 39%, p < 0.001). A smaller percentage of Veterans reported use of non-VA overnight care (i.e., a hospitalization; 9%) or a non-VA psychiatrist (10%). Women were more likely than men to use non-VA overnight care (11% vs. 6%, p = 0.003) or a non-VA psychiatrist (12% vs. 9%, p < 0.001). Many Veterans endorsed current private health insurance plans (59%) and/or government-provided insurance (60%), and a greater percentage received insurance from their employer or a partner's employer (88% overall), with no differences by gender.

Discussion

This report describes baseline data from the first longitudinal prospective cohort study of OEF/OIF/OND Veterans aimed at improving clinical care and outcomes for women Veterans. Consistent with previous observations from EHR data8 and the national population of women Veterans,10 women in the WVCS2 survey cohort were younger, more diverse, and had more years of education than men. These women were also less likely to be married, and reported lower incomes and rates of home ownership. Although women represent a growing percentage of the U.S. Armed Forces, and report lower combat exposure than men, women Veterans also reported lower unit support.9

Men and women did not differ in some key risk factors (e.g., smoking, lifetime trauma) or metrics of physical and mental health (insomnia, PTSD), but women reported worse perceived health, nearly 10 × higher rates of MST, and significantly more women met criteria for major depression and generalized anxiety disorders. In contrast, men were more likely to report being overweight or obese, to have high blood pressure, and to meet criteria for substance abuse. When examining healthcare utilization, women received more frequent and more recent medical treatment, from a mix of VA and non-VA providers.

Although there was a similar prevalence of chronic pain among men and women (i.e., 75%), significantly more women reported recent pain in many bodily sites and across multiple sites. Both results align with earlier reports from smaller OEF/OIF/OND Veteran samples.31,32 It is possible that risk of musculoskeletal problems and chronic pain among women Veterans may not be approximated by the traditional service-related metrics that are used to appraise potential health risks in men. For example, the physical risks to which women are exposed may not be reflected in their number of deployments or participation in combat, which occurs less frequently for women versus men. Although a higher percentage of men reported physical injury due to deployment (i.e., 66%), it is still notable that over half of women (58%) reported deployment-related physical injury. Almost half of men and women, respectively, also reported physical injury that occurred during other service.

The number of women Veterans who reported recent treatment for severe chronic pain (38%) also appears to be remarkably disproportionate to those who experience regular pain symptoms and interference with daily life (75%). Reasons for this discrepancy may include difficulties that women Veterans experience in communicating about pain and/or that they are “not being heard” by their providers when talking about pain.33 Previous studies of gender differences in civilian pain care indicate that women are less likely than men to receive some treatments, including interventional techniques, but may be more likely to receive opioids,31 a treatment option that may be useful to treat pain but does not target its source. Determining underlying risk factors for pain conditions and optimal therapeutic strategies (e.g., early exercise, physical therapy, weight reduction, and social support32) is needed to better address pain among younger women Veterans.

The cardiovascular health of women Veterans is receiving growing attention.34 In this study, approximately one-quarter of respondents, overall, reported recent treatment for high blood pressure or related cardiovascular disease risk factors (e.g., diabetes), and women were less likely to report this than men, suggesting a lower prevalence of those conditions among women. Other studies of OEF/OIF/OND Veterans have shown that women with hypertensive blood pressure are less likely than men to have a diagnosis of hypertension or to receive antihypertensive medication,35 and disparities have been found in lipid management and control of diabetes.36–38 As the OEF/OIF/OND cohort ages, cardiovascular disease will become an increasingly important health issue. It is important to note that younger women Veterans are more likely to identify as minorities than men.10 Higher rates of cardiovascular risk have been previously described among Black women, particularly among Black women in the WVCS EHR cohort with depression,36 a factor that, along with PTSD, increases risk of incident cardiovascular disease.39,40

Women reported a similar or greater prevalence of nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., MST, mental health disorders, insomnia34,41) compared with men, matching observations in the broader population of women Veterans and civilians. Lower traditional risk factors observed among women WVCS2 participants also align with previous reports,42 suggesting that OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans should be viewed as a distinct group, and two hypotheses are proposed: women Veterans' cardiovascular risk increases to exceed that of comparison groups later in life, and women's nontraditional risk factors are more substantial predictors of cardiovascular health over time.

Orienting the VHA research agenda toward exploring these hypotheses is essential before healthcare providers integrate such correlates of cardiovascular health into clinical decision making and educating women patients about their cardiovascular risk. Determining the subgroups of women who are more vulnerable to incident cardiovascular conditions and their trajectories of risk over time will aid in the development and testing of surveillance strategies, and in the design and implementation of targeted preventive interventions for women Veterans.

On the WVCS2 survey, 10 × more women endorsed exposure to MST compared with men, and a higher percentage of women endorsed significant symptoms of depression and anxiety, but similar percentages endorsed lifetime traumatic events, intimate partner violence, PTSD, and PTSD treatment. Some of these results are consistent with EHR data, showing that depression and anxiety are more often diagnosed among women.8,43 EHR data also indicate that a PTSD diagnosis is more common among men,8 contrasting with the similar level of PTSD symptom severity reported by men and women in this cohort. There are several explanations for this discrepancy: symptoms of trauma may manifest differently for women or women may under-report symptoms of trauma.44 Alternately, women's trauma-related psychiatric symptoms may be appraised differently by providers who may instead diagnose depression and anxiety,45 due to shared characteristics with PTSD.46

Understandably, most research to date concerning women Veterans' healthcare utilization has focused on utilization in VA medical centers.8,47 To complement this literature, additional detailed information regarding the perspectives of, preferences for, and experiences with VA versus non-VA-based healthcare by women Veterans, and their access to non-VA care, is needed to contextualize demographic and health information, and to successfully improve the integration between VA and non-VA care in the service of women's health management.48 In WVCS2, women reported utilizing VA care at higher rates than men and receiving both VA and non-VA care, results that intersect with previous findings from EHR data and gender differences in healthcare utilization observed among the general population.8,10

As of 2015, women Veterans across all service eras typically had >12 annual VA encounters.10 Of note, 66% of women and 62% of men surveyed in WVCS2 stated their intention to use the VA as their main source of healthcare in the future. However, more than 37% of women Veterans are sent into the community for specialty services that are unavailable at the VA (i.e., mammograms, gynecologic surgery).10 OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans may also prioritize the cost and convenience of non-VA care.49 Based on this survey, it is unknown if women reported receiving external care because the VA sent them for treatment, or if women are choosing to use non-VA care for self-pay, and whether there are different rationales for seeking non-VA care from a general practitioner, psychiatry, or other outpatient services.

Healthcare utilization and access among Veterans are also a direct reflection of their insurance coverage. Generally, Veterans with private insurance coverage are less likely to exclusively use VA care.50,51 Although there is a paucity of information about healthcare coverage among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans or women Veterans overall, results from the WVCS2 survey begin to fill this gap. Women reported similar health insurance to men, and women were equally likely to have private or government-provided insurance.

Assessing the value of non-VA care and determining the best strategies for coordinating between VA and external care are essential for women. As the population of women Veterans grows, it will place greater demand on VA outpatient services. Women's care preferences and needs must be considered to ensure that VHA policy and planning decisions account for both the changing Veteran population and chronic conditions that are common among women.10

Several limitations of the current report should be noted. First, there are aspects of the WVCS2 data that may reduce the generalizability of our findings. The response rate of 32%, while consistent with paper survey studies of women Veterans in the last 5 years,52 is relatively low. Furthermore, WVCS2 only includes Veterans who enrolled in VA care. Other recent data indicate that 57% of OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans and 55% of men are enrolled in the VA, suggesting that about half of the younger population of Veterans may be unaccounted for.53 This constraint could result in under- or overestimated prevalence statistics and gender comparisons.

Also related to generalizability, WVCS2 participants were recruited from geographically diverse study sites, but survey respondents were a self-selected group, and the percentage of respondents who were racial minorities did not align with national data.47 Although data were combined across study sites, there may be geographic differences (e.g., rural–urban54) in the prevalence of certain conditions, their treatment, and gender differences, which represent areas for future investigation.

Self-report data are also known to include a degree of bias. Yet, many of these results align with findings from smaller samples of OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans and EHR data. The cross-sectional nature of these data also prevents interpretations about causality, although the WVCS2 follow-up survey will offer that opportunity.

In WVCS2, women Veterans were not compared with women civilian counterparts.55 Drawing such distinctions was not a goal of this investigation, and is merited to fully discern younger women Veterans' unique conditions and needs for preventive healthcare from those in the general population. Finally, gender was only measured with male and female options. Other studies of younger Veterans should include a broader range of gender options to identify nonconforming persons who may be uniquely vulnerable to emotional or physical health conditions.

Conclusion

Baseline data from the WVCS2 survey cohort extend our knowledge of musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and mental health among the youngest women Veterans, including the distinctive characteristics and needs of these women Veterans seeking VA care after military service, thereby illuminating potential areas for research with this unique group. Some comparisons by gender also revealed similarities in medical morbidities, utilization, or access, which may be equally important for understanding the healthcare needs of contemporary women Veterans and for offering equitable, gender-specific care.

Information disseminated from the WVCS1 parent study has already begun to provide an evidence base for why and how to improve national policies concerning health services research and development for women Veterans.3,8,35,36 WVCS2 findings may also inform the design and testing of new healthcare models that tailor practices and address specific trajectories of, and vulnerabilities to, disease in women Veterans. These advances may effectively reduce the burden of chronic disease faced by the healthcare system and experienced by each woman who has served in the U.S. military.

Acknowledgments

We are exceptionally grateful to the Veterans who participated in WVCS and would like to extend our gratitude to the entire OED/OIF/OND cohort of Veterans for their service. We are also grateful to Erin Krebs for sharing her expertise when designing the original WVCS survey, to Mary Driscoll for her guidance concerning the pain measures, to Norman Silliker and Vera Gaetano for their contributions coordinating WVCS1 and 2 and in support of this article, and to Harini Bathulapalli and Amber Brown for their assistance with data collection, processing, and study management.

Authors' Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to this work, including to the intellectual content, gave final approval of the published version, and agree to be accountable for the work, thus adhering to the guidelines set forth by this Journal.

Disclaimer

The U.S. Veterans Health Administration had no direct role in the study design, execution, writing, or decision to submit this article for publication. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy or position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, and Health Services Research and Development grants (CIN13-407, HIR09-007, DHI07-065-1), and is a translational use case project within the Veterans Health Administration-funded Consortium for Healthcare Informatics Research; by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (1K01NR013437); and is supported by the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the Center for Advancing Translational Science, components of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR024138). A.E.G.'s and C.E.C.'s efforts were sponsored by Advanced Fellowships in Women's Health and Health Services Research and Development through the Veterans Health Administration Office of Academic Affairs. A grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K23HL141644) sponsored L.R.'s efforts.

References

- 1. Veteran Population Projections Model (VetPop). 2016 Tables 5L and 8D, 2016. Available at: www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp Accessed April2, 2019

- 2. Burkman K, Maguen S. Gender differences in sleep and war zone-related post-traumatic stress disorder. In Vermetten E, Germain A, Neylan T. (eds): Sleep and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. New York, NY: Springer, 2018:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Portnoy GA, Relyea MR, Decker S, et al. Understanding gender differences in resilience among veterans: Trauma history and social ecology. J Trauma Stress 2018;31:845–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mattocks KM, Haskell SG, Krebs EE, Justice AC, Yano EM, Brandt C. Women at war: Understanding how women veterans cope with combat and military sexual trauma. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klingensmith K, Tsai J, Mota N, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Military sexual trauma in US veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:e1133–e1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Volume 4: Longitudinal trends in sociodemographics, utilization, health profile, and geographic distribution. In Women's Health Evaluation Initiative (eds): Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Washington, DC: Women's Health Services, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018:1–144 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center. Performance measure report. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haskell SG, Mattocks K, Goulet JL, et al. The burden of illness in the first year home: Do male and female VA users differ in health conditions and healthcare utilization. Womens Health Issues 2011;21:92–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Street AE, Gradus JL, Giasson HL, Vogt D, Resick PA. Gender differences among veterans deployed in support of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:556–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frayne S, Phibbs C, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women veterans in the veterans health administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal trends in sociodemographics, utilization, health profile, and geographic distribution. Washington, DC: Women's Health Evaluation Initiative, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11. King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, Samper RE. Deployment risk and resilience inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Mil Psychol 2006;18:89–120 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM, Zimering RT, Taylor KL, Mora CA. Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychol Assess 1989;1:53–55 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iqbal SU, Rogers W, Selim A, et al. The veterans RAND 12 item health survey (VR-12): What it is and how it is used. CHQOERs VA Medical Center. Bedford, MA: CAPP Boston University School of Public Health, 2007:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, et al. A shorter form health survey: Can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med 1997;19:179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cleeland C. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CL, Loeser JD, eds. Advances in pain research and therapy: Issues in pain measurement. New York: Raven Press, 1989:391–403 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mosca L, Mochari-Greenberger H, Dolor RJ, Newby LK, Robb KJ. Twelve-year follow-up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health. Circulation 2010;3:120–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mosca L, Mochari H, Christian A, et al. National study of women's awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation 2006;113:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Towfighi A, Albert MA. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: Results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation 2013;127:1254–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mochari-Greenberger H, Mills T, Simpson SL, Mosca L. Knowledge, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular disease prevention by race and ethnicity in women: An American Heart Association national survey. J Womens Health 2010;19:1243–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mochari H, Ferris A, Adigopula S, Henry G, Mosca L. Cardiovascular disease knowledge, medication adherence, and barriers to preventive action in a minority population. Prev Cardiol 2007;10:190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychol Assess 1998;10:408 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 1993;88:791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychol Assess 2000;12:210–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan C, Chan Y, Au A, Cheung G. Reliability and validity of the “Extended-Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream”(E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2010;17:109–117 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:1019–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Driscoll MA, Higgins D, Shamaskin-Garroway A, et al. Examining gender as a correlate of self-reported pain treatment use among recent service veterans with deployment-related musculoskeletal disorders. Pain Med 2017;18:1767–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Driscoll MA, Higgins DM, Seng EK, et al. Trauma, social support, family conflict, and chronic pain in recent service veterans: Does gender matter? Pain Med 2015;16:1101–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mattocks K, Casares J, Brown A, et al. Women veterans' experiences with perceived gender bias in US department of veterans affairs specialty care. Womens Health Issues 2020;30:113–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Han JK, Yano EM, Watson KE, Ebrahimi R. Cardiovascular care in women veterans: A call to action. Circulation 2019;139:1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burg MM, Brandt C, Buta E, et al. Risk for incident hypertension associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in military Veterans and the effect of posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Psychosom Med 2017;79:181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haskell SG, Brandt C, Burg M, et al. Incident cardiovascular risk factors among men and women Veterans after return from deployment. Med Care 2017;55:948–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vimalananda VG, Miller DR, Christiansen CL, Wang W, Tremblay P, Fincke BG. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among women veterans at VA medical facilities. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:517–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whitehead A, Davis M, Duvernoy C, et al. The state of cardiovascular health in women veterans. Volume 1: VA outpatient diagnoses and procedures in fiscal year (FY) 2010. Washington, DC: Women's Health Evaluation Initiative, Women's Health Services, Veteran's Health Administration, Department of Veteran's Affairs, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Burg MM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review. Am Heart J 2013;166:806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wulsin LR, Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med 2003;65:201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gaffey AE, Redeker NS, Rosman L, et al. The role of insomnia in the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and hypertension. J Hypertens 2020;38:641–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whitehead AM, Maher NH, Goldstein K, et al. Sex Differences in veterans' cardiovascular health. J Womens Health 2019;28:1418–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramsey C, Dziura J, Justice AC, et al. Incidence of mental health diagnoses in veterans of operations Iraqi freedom, enduring freedom, and new dawn, 2001–2014. Am J Public Health 2017;107:329–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mengeling MA, Burkitt KH, True G, et al. Sexual trauma screening for men and women: Examining the construct validity of a two-item screen. Violence Vict 2019;34:175–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maynard C, Nelson K, Fihn SD. Characteristics of younger women Veterans with service connected disabilities. Heliyon 2019;5:e01284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Price M, Legrand AC, Brier ZM, Hébert-Dufresne L. The symptoms at the center: Examining the comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and depression with network analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2019;109:52–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moreau JL, Dyer KE, Hamilton AB, et al. Women veterans' perspectives on how to make veterans affairs healthcare settings more welcoming to women. Womens Health Issues 2020;30:299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Evans EA, Tennenbaum DL, Washington DL, Hamilton AB. Why women veterans do not use VA-provided health and social services: Implications for health care design and delivery. J Humanist Psychol 2019. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1177/0022167819847328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Hamilton AB, Cordasco KM, Yano EM. Women veterans' healthcare delivery preferences and use by military service era: Findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:571–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dworsky M, Farmer CM, Shen M. Veterans' health insurance coverage under the affordable care act and implications of repeal for the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Washington DL, Farmer MM, Mor SS, Canning M, Yano EM. Assessment of the healthcare needs and barriers to VA use experienced by women veterans: Findings from the national survey of women veterans. Med Care 2015;53:S23–S31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gaeddert LA, Schneider AL, Miller CN, et al. Recruitment of women veterans into suicide prevention research: Improving response rates with enhanced recruitment materials and multiple survey modalities. Res Nurs Health 2020;43:538–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. VA Utilization Profile FY 2016. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, 2017:1–22 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cordasco KM, Mengeling MA, Yano EM, Washington DL. Health and health care access of rural women veterans: Findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Rural Health 2016;32:397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Nelson KM, Jakupcak M, Simpson TL. Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]