Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines US racial/ethnic disparities in outpatient visit rates to 29 physician specialties.

Access to the full range of medical specialties is a cornerstone of high-quality medical care. However, many patients, especially members of racial and ethnic minority groups, face barriers to such care. We examined nationwide racial/ethnic disparities in outpatient visit rates to 29 physician specialties.

Methods

We pooled data on adults 18 years or older from the 2015 to 2018 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which collects demographic (including self-reported race/ethnicity) and health care utilization data from a nationally representative sample of the noninstitutionalized, civilian US population. We tabulated office and outpatient department visits to each physician specialty and calculated adjusted rate ratios (ARRs) for each racial/ethnic minority group (compared with the White population) using negative binomial regression adjusted for age. In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for sex, self-reported health, health insurance, education level, and income.

Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp), with procedures that accounted for the survey’s complex sampling and MEPS-provided weights to generate national estimates. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. The Cambridge Health Alliance institutional review board exempted this study from review and informed consent because of the use of deidentified, publicly available data.

Results

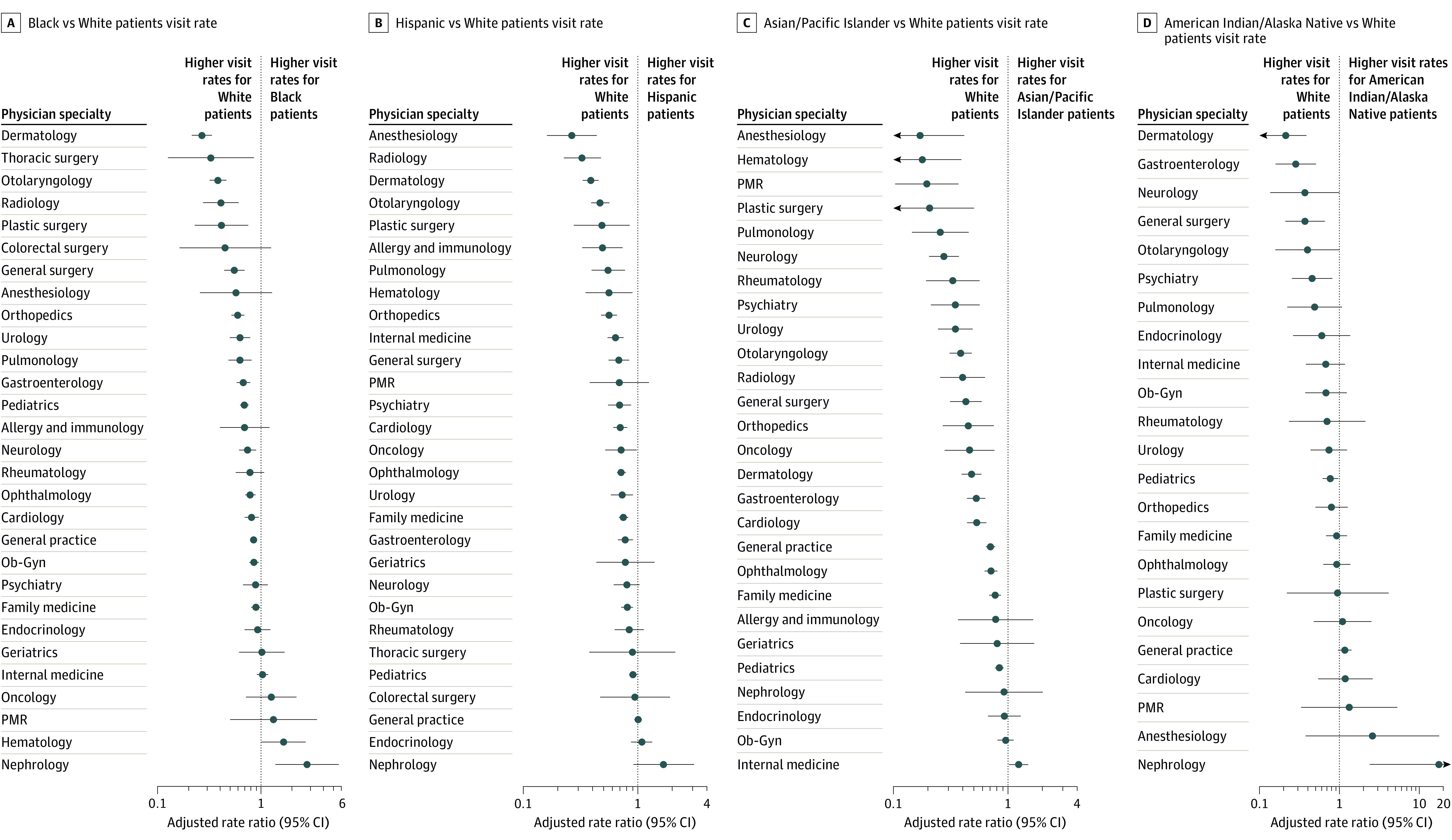

We included 132 423 individuals in our study (Table). Black individuals had low visit rates (vs White individuals) to most specialties (23 of 29 [79.3%]; 17 of 29 [58.6%]; P < .05) specialties (Figure). Among specialties with many visits, Black:White disparities were particularly marked for dermatology (ARR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.21-0.34), otolaryngology (ARR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.32-0.46), plastic surgery (ARR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75), general surgery (ARR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.44-0.69), orthopedics (ARR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.51-0.69), urology (ARR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.50-0.78), and pulmonology (ARR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48-0.81). Black individuals had higher visit rates to nephrologists (ARR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.37-5.62) and hematologists (ARR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.0-2.70) and similar visit rates to internists, geriatricians, and oncologists.

Table. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | % (SE) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Native American | Other | Total | |

| No. | 56 454 | 23 218 | 38 262 | 9122 | 1167 | 4200 | 132 423 |

| Total | 60.0 (0.8) | 12.3 (0.5) | 17.7 (0.6) | 6.1 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.2) | 100 (NA) |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 42.4 (0.3) | 35.9 (0.3) | 31.3 (0.2) | 37.3 (0.6) | 36.2 (1.3) | 27.6 (0.6) | 38.8 (0.2) |

| Women | 50.9 (0.3) | 53.1 (0.5) | 49.9 (0.5) | 52.4 (0.7) | 45.7 (2.0) | 51.0 (1.2) | 51.1 (0.2) |

| Insurance | |||||||

| Private | 61.4 (0.7) | 47.7 (1.0) | 44.6 (1.0) | 65.9 (1.3) | 43.0 (3.7) | 55.7 (1.6) | 56.7 (0.6) |

| Medicaid | 9.4 (0.4) | 26.0 (0.8) | 28.6 (0.8) | 13.6 (1.1) | 19.9 (2.6) | 25.7 (1.4) | 15.7 (0.4) |

| Any Medicare | 20.8 (0.4) | 13.4 (0.5) | 7.7 (0.3) | 12.2 (0.8) | 11.5 (1.5) | 10.0 (0.7) | 16.6 (0.3) |

| Other public, including VA | 3.4 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.3) | 5.4 (1.5) | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.1) |

| Other | 0.4 (0) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.1 (0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.3 (0) |

| Uninsured | 4.7 (0.2) | 8.2 (0.4) | 16.5 (0.6) | 6.3 (0.5) | 20.0 (2.5) | 4.6 (0.6) | 7.4 (0.2) |

| Education levela | |||||||

| <High school | 34.5 (0.7) | 35.5 (0.9) | 36.2 (0.7) | 34.3 (1.6) | 39.0 (4.4) | 35.6 (1.8) | 35.1 (0.4) |

| High school | 21.2 (0.6) | 22.7 (0.9) | 21.5 (0.6) | 16.4 (1.2) | 21.5 (3.3) | 17.5 (1.4) | 21.0 (0.4) |

| ≥Some college | 44.4 (0.8) | 41.8 (1.0) | 42.3 (0.7) | 49.3 (1.7) | 39.5 (4.0) | 46.9 (1.8) | 43.9 (0.5) |

| Income (% of federal poverty level) | |||||||

| 0-100 | 8.7 (0.3) | 22.2 (0.8) | 19.2 (0.7) | 10.3 (1.0) | 23.2 (2.1) | 16.7 (1.2) | 12.7 (0.3) |

| 100-200 | 13.9 (0.4) | 23.0 (0.6) | 26.3 (0.6) | 13.7 (0.9) | 26.8 (2.7) | 20.4 (1.2) | 17.5 (0.3) |

| 200-300 | 1.05 (0.4) | 17.7 (0.6) | 19.1 (0.6) | 12.7 (0.9) | 20.5 (2.9) | 16.3 (1.2) | 16.0 (0.3) |

| ≥300 | 62.3 (0.7) | 37.0 (1.0) | 35.4 (0.9) | 63.3 (1.4) | 29.4 (3.2) | 46.6 (2.0) | 53.8 (0.6) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; VA, Veteran Affairs/Tricare.

Limited to adults 25 years and older.

Figure. Outpatient Visit Rate Ratios for Individuals in Racial Minority Groups Compared With White Individuals, Adjusted for Age.

Visit ratios of less than 1 indicate that racial/ethnic minority group patients make fewer visits to that specialty than White patients. All ratios are adjusted for age. Scale is logarithmic. Patients identified a physician specialty for 411 272 of 418 823 visits (98.2%). Because osteopathic physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) can work in any specialty, and because visits to clinicians whom patients identified as osteopaths, NPs, or PAs were not assigned to specific specialties, visits to these clinician types were excluded. For each race/ethnicity, we excluded specialties with fewer than 10 unweighted visits, as well as visits to nonoutpatient specialties (ie, pathologists and hospitalists). For this reason, the number of specialties varies by race/ethnicity. We have substituted the term colorectal surgery for proctology, which is used in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Ob-Gyn indicates obstetrics and gynecology; PMR, physical medicine and rehabilitation.

For Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals, visit ratios (compared with White individuals) were lower than 1.0 for 26 of 29 (89.7%) and 26 of 27 specialties (96.3%), respectively, and significantly lower for 20 of 29 (69.0%) and 21 of 27 specialties (74.1%). Similar patterns were present for Native American individuals, although the 95% CIs were wide. The ARRs for Hispanic vs White individuals were markedly low for dermatology (0.39; 95% CI, 0.33-0.46), otolaryngology (0.47; 95% CI, 0.39-0.56), and pulmonology (0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.77). The ARRs for Asian/Pacific Islander vs White individuals were markedly low for hematology (0.18; 95% CI, 0.08-0.39), pulmonology (0.26; 95% CI, 0.15-0.45), and otolaryngology (0.39; 95% CI, 0.31-0.48).

Results were similar when stratified by sex (data not shown). In sensitivity analyses, disparities persisted after controlling for age, sex, self-reported health, health insurance, income, and education level. The ARRs for Black vs White individuals in these models included dermatology (0.34; 95% CI, 0.26-0.43), plastic surgery (0.35; 95% CI, 0.21-0.59), otolaryngology (0.43; 95% CI, 0.34-0.54), general surgery (0.54; 95% CI, 0.42-0.69), orthopedics (0.63; 95% CI, 0.54-0.74), urology (0.63; 95% CI, 0.51-0.78), and pulmonology (0.56; 95% CI, 0.40-0.77).

Discussion

Racial and ethnic minority groups are markedly underrepresented in the outpatient practices of most medical and surgical specialties. Disparities persisted after accounting for several social determinants of access to care.

Several factors may underlie these findings. Racial/ethnic minority groups are more likely to reside in areas with a shortage of physicians1 and less likely to receive specialty referrals from primary care physicians.2 The history of racism in health care may lead non-White patients to distrust the health care system, suppressing utilization.3 Physicians are less likely to grant appointments for patients with Medicaid or without insurance, who are disproportionately members of racial/ethnic minority groups.4 A higher burden of end-stage kidney disease and nearly universal Medicare coverage for patients with this disease may explain the high nephrology visit rates for individuals of racial/ethnic minority groups.5

Our study has limitations. We lacked detailed clinical metrics; thus, we cannot assess whether unequal utilization affects outcomes. Physician specialty was patient-reported, which may introduce errors.

The study findings demonstrate a consistent pattern of racial and ethnic disparities in outpatient care, implicating systemic defects that are best characterized as structural racism. Eliminating these structural impediments will require changes in the health care system and society at large.

References

- 1.Doescher M, Fordyce M, Skillman S, Jackson E, Rosenblatt R. Persistent primary care health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) and health care access in rural America. Accessed November 16, 2020. http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/Persistent_HPSAs_PB.pdf

- 2.Landon BE, Onnela J-P, Meneades L, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL. Assessment of racial disparities in primary care physician specialty referrals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2029238. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(6):2093-2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2324-2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Racial disparities in kidney disease outcomes. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33(5):409-415. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]