Abstract

Anal fistula is a common and serious complication of Crohn's disease (CD). A sufficiently suitable animal model that may be used to simulate this disease is yet to be established. The aim of the present review was to summarize the different characteristics and experimental methods of commonly used animal models of CD with anal fistula. Electronic databases were searched for studies reporting on the use of this type of animal model. A total of 234 related articles were retrieved, of which six articles met the inclusion criteria; these were used as references for the present review article. The characteristics of the animal models, the advantages and disadvantages of the modeling methods and the similarities with patients with CD and anal fistula were summarized and analyzed. The evidence suggests that a sufficiently suitable animal preclinical model requires to be established.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, anal fistula, animal, model

1. Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is an immune-mediated chronic recurrent, systemic disease characterized by gastrointestinal inflammation (1). CD is a complex disease, which occurs due to genetic and environmental factors (2). Accumulating evidence has indicated that bacteria have a major role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (3). Intestinal bacteria and normal intestinal microbiota may cause damage to the intestinal barrier and induce inflammation in susceptible hosts, which indicates that all bacteria may develop into potential pathogens (4). Changes in microbiota composition and metabolism may lead to enhanced immune response, epithelial dysfunction and increased mucosal permeability (5). Sartor (4,5) performed extensive research on CD in different rodent models. He established at least 11 different models of genetically engineered mice and rats, induced enteritis models of indomethacin, guinea pigs fed carrageenan, a sulfated red seaweed extract, and cotton top tamarins a primate model of colitis (5). These observations in animal models demonstrated that intestinal flora imbalance is a key factor in the development of intestinal inflammation and IBD.

The incidence of CD in industrialized countries has been steadily increasing over the past 70 years. In Europe, the incidence of CD is estimated to be 12.7/100,000 individuals per year (6). The clinical manifestations are abdominal pain, fever, intestinal obstruction and hematochezia or mucinous diarrhea, which mainly affect the gastrointestinal tract and severely compromise the quality of life of affected patients. Since CD is characterized as a discontinuous or segmental inflammatory reaction of the total intestinal wall, it is easy to penetrate into adjacent organs, tissues or skin (7). Therefore, attention should be paid to the formation of fistula in addition to the common complications caused by intestinal obstruction (7).

Anal fistula is the most common perianal lesion observed in CD (8). Panés and Rimola (9) summarized the current classification of perianal fistula in their review article. Perianal fistula is a common complication of CD and it is estimated to affect 26-28% of patients within the first two decades following diagnosis (10). In recent years, local injections of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have achieved promising results in terms of fistula closure (11). However, the lack of clinical safety and effectiveness data remains a major constraint to the development of novel treatments or therapeutic strategies. The pathogenesis of the disease may be investigated and novel treatment methods may be explored by establishing specific animal models and by further studying the safety and effectiveness of different treatment schemes in animals.

2. Literature search methodology

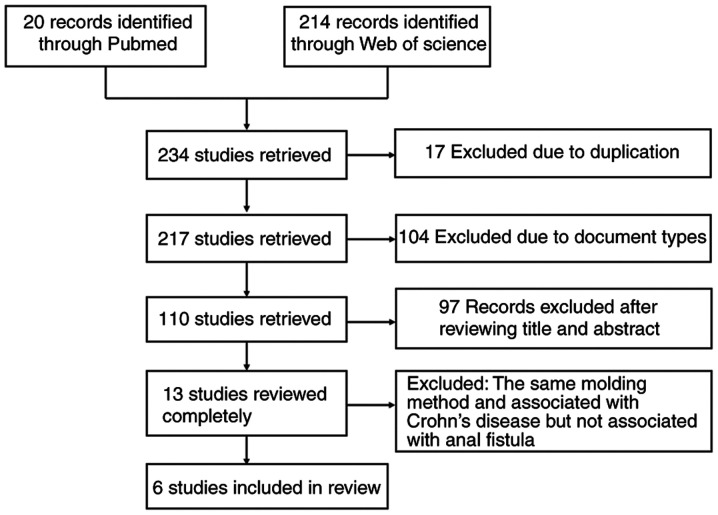

This study was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines. The search included articles published in PubMed and Web of Science. Specific search terms were included, such as ‘Crohn's disease AND fistula AND animal model’. All relevant articles up to December 31, 2020 were included by reviewing the titles and abstracts regarding animal models of CD with anal fistula. In addition, the reference lists of the relevant articles were also screened. The detailed literature screening process is depicted in Fig. 1. In the initial literature search, 234 citations were identified. These articles were examined and six studies were finally selected for inclusion in the present review. The inclusion criterion was that the content was required to be relevant to animal experiments on CD with anal fistula. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Simple anal fistula without any direct association with CD; and ii) repetitive modeling methods, referring to the same modeling method being used in different studies. A total of 234 related studies were retrieved, examined and extracted. After review of the abstract and full-text, 228 articles were excluded. A total of six articles were summarized in accordance with the inclusion criteria. The species of each experimental model and the modeling methods from each study were characterized. The modeling methods and characteristics are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search of studies included in the present review.

3. Establishment of body surface fistula model associated with CD in rats

Ryska et al (12) studied rats using a modified cecal anastomosis described by Bültmann et al (13). Ryska et al (12) performed the following operations on rats: The animals underwent a short (2-2.5 cm) median laparotomy following back fixation. The blind area of the cecum was subcutaneously pulled through the fascia and muscular layer. The cecum was exposed to the side of the laparotomy through a subcutaneous tunnel (2.5 ml/3 cm), simulating the fistula. The intestine was opened and the edge was fixed to the skin without adopting the valgus position. This simulated an external opening. The rats remained at that state for 4 weeks and all fistulas were verified by fecal secretion. The probes were able to pass through the fistula freely using X-ray angiography (12).

Ryska et al (12) used this method to establish a rat model of anal fistula and to observe the efficacy and distribution of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) that included bioluminescent molecules. It was concluded that local application of ADSCs significantly improved the fistula closure rate in this animal model and may provide a novel method for the treatment of CD with anal fistula. Considering that the fistula in this model was artificially created without the background of chronic intestinal inflammation, a certain localized type of disease must be taken into account (10). The data revealed the lack of a complete and accurate clinical correlation between modified cecostomy and the incidence of CD with anal fistula (14). Therefore, the simulated lesion was closer to the external orifice of the perianal fistula. This study provided evidence supporting the use of ADSCs in the treatment of perianal CD-related fistula.

4. Establishment of anal fistula model following enteritis induced by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzensulfonic acid (TNBS) in rats

In 2020, Flacs et al (15) induced proctitis in rats by rectal enema using TNBS. After seven days, the sphincter fistula was established using a surgical line. The anal sphincter was pierced into the external orifice to form the fistula. The external mouth was located ~1 cm from the anus. Subsequently, the needle was removed from the catheter and the surgical line was inserted into the fistula along the catheter. TNBS was injected twice a week until it was removed on the 28th day. Each rat was examined by pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to and after 7 days of suture extraction. The rats were then sacrificed and the fistula was examined by pathological evaluation.

Flacs et al (15) demonstrated that this preclinical model was optimal. A persistent fistula was confirmed by MRI and its pathological examination indicated acute and chronic inflammation, granulation tissue, fibrosis, epithelialization and proctitis adjacent to the rectum (16). This repeatable preclinical model may be used to evaluate the effectiveness of innovative treatment for CD with perianal fistula. It also revealed significant inflammatory activity in the fistula and emphasized the difference between common and CD-induced anal fistula (14). In short, this model is able to successfully reproduce the imaging and pathological characteristics of CD with anal fistula. This simple and repeatable preclinical model may be used to evaluate the efficacy of innovative treatments or strategies for CD with anal fistula.

TNBS is a hapten that induces a direct type 1 T-helper cell response (17). The latter involves the adaptive immune response for the induction of colitis. The use of the TNBS reagent for the induction of colitis is associated with certain limitations. A major limitation of this model is the lack of sufficient immunopathological relevance of using a chemically-induced, self-limiting model of colonic injury-induced inflammation. However, it is an optimal method for inducing CD-associated enteritis due to its operating success and repeatability. The use of spontaneously formed or genetic animal models should also be considered.

5. Spontaneous fistula perianal disease in the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM)P1/YitFc strain

Rivera-Nieves et al (18) established a strain of SAMP1/Yit mice at the University of Virginia in 2003. The phenotypic and immune characteristics were systematically analyzed at the age of 4, 10, 40 and >60 weeks. The distinctive characteristics between the SAMP1/YitFc substrain and its parent SAMP1/Yit Japanese strain have been previously described (19). In addition, it was reported that perianal inflammation developed into fistula in a group of mice, in which superficial perianal ulcers formed fistula bundles similar to those noted in CD-associated human perineal fistula. This was the first report of an animal model of IBD at that time.

Rivera-Nieves et al (18) further provided a spontaneous model of terminal ileitis similar to CD. In addition, since inbreeding of SAMP1/YitFc mice has been continuously performed for over 20 generations from their original ancestors, genetic variations, by mutation and/or genetic drift, may have occurred. Rivera-Nieves et al (18) provided detailed characteristics of the clinical, pathological and histological progression of a mouse model of spontaneous discontinuous chronic ileitis characterized by focal fibrosis and perianal fistula. This model may provide a unique tool for further understanding the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation of CD and developing novel methods for the treatment of its serious complications. However, only 5% of the mice developed anal fistula lesions, which limits the use of the model for the investigation of the clinical manifestations of CD.

6. Spontaneous enterocutaneous fistulae in mice following transplantation of human fetal small intestine

Bruckner et al (20) transplanted human fetal intestines into mice as a novel platform to assess inflammation by enterocutaneous fistulas (21). The authors reported successful transplantation of human fetal small intestines from week 12 to 18 of gestation to the back of mice (age, 12-16 weeks) with severe combined immune deficiency. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses of the xenostomy graft indicated that the epithelial cells of the mucosa were spindle-shaped and formed fistulas to the chronic non-healing wound in the skin of the host mice covered with the graft. The data indicated that ~17% of the fully developed enterocutaneous fistulas were spontaneously localized in the subcutaneous human intestinal xenograft, which displayed striking histopathological similarity with CD fistulas (22-26). A lack of IL-10 gene expression in the inflammatory response of fully developed human intestinal xenografts to lumen bacteria and systemic lipopolysaccharides was also reported (27). It is assumed that the human intestinal xenografts lacking IL-10 gene expression exhibited inflammation and fistula.

Scharl et al (26) developed a replicable model of spontaneous enterocutaneous fistula with similar morphology to that of CD fistula. However, the practicability of their CD-associated fistula xenograft model requires further verification. Development of fistula did not occur in all xenografts, suggesting that its induction may be artificial, which does not accurately reflect the pathological process of patients with CD.

Mice, which have a strong reproductive capacity and a short reproductive cycle may be used to establish a variety of gene-modified mouse models and to spontaneously induce fistula-associated disease (28,29). However, due to the long disease cycle and low incidence rate, the practicability of this model is limited.

7. Improved model of mechanically induced porcine ARF

Dryden et al (30) established a model of a larger, more invasive fistula based on Buchanan et al (31), which resembled a clinical fistula. The original technique was improved by guiding the 14G venous catheter through the skin incision at different positions (90˚, 180˚ and 270˚, respectively) in the perineum. The catheter was inserted through the muscle of the anal sphincter (confirmed by palpation) and the angle was adjusted following penetration of the rectal mucosa by the catheter. The latter was subsequently removed and a guide wire was passed through the catheter cavity. Subsequently, a 20-ml F dilator was passed through the sphincter above the guide wire. The 4-mm silicon wire was fixed for 4 weeks through the channel behind the expander. Fistula formation was confirmed by MRI and microbiological evaluation. After 28 days, the fat around the aorta was extracted and processed into stromal vessels. Stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was labeled with primary ADSCs by membrane staining and subsequently injected into the fistula or stents. The untreated fistula was injected with fibrin glue. The healing of the animals was observed at the 2nd and 4th week and they were subsequently euthanized to evaluate the healing of the fistula by histological examination. This study made a preliminary evaluation of isolated adipose mesenchymal primary cell therapy for ARF and evaluated the role of bioabsorbable scaffolds in cell therapy. It was suggested that SVF transmitted through bioabsorbable scaffolds promotes faster healing than SVF or fibrin glue alone. It was concluded that stent technology may improve the cure rate of cell therapy for CD-associated ARF.

The model has several characteristics that limit its applicability to human fistulostomy disease, such as the comparison of the mechanical nature of its origin with the spontaneous inflammatory etiology of the disease in humans and the treatment of model fistulostomy without intervention. An additional limitation is the distinction between SVF-induced healing and natural healing at the time prior to the initiation of natural healing, which rarely occurs in human fistulas, particularly those caused by CD. In contrast to these findings, surgical treatments may achieve higher temporary closure rates, whereas they also have a propensity to injure the anal sphincter and induce incontinence (32,33). The authors of these studies suggested that the local anatomy of pigs was similar to that of humans and that the anal fistula model of large animals confirmed by MRI and histology may be further used for investigations regarding the diagnosis and treatment of anal fistula. However, this model is associated with major limitations with regard to animal feeding, cost, size and repeatability.

The local anatomy of pigs is similar to that of humans. The large animal model of perianal disease confirmed by MRI, histology and pathology may be used to study the diagnosis and therapeutic strategies for CD with anal fistula. Pig models have been used to simulate the development of CD with anal fistula (30,34). The pigs were eventually euthanized to obtain tissue samples and pathological specimens. Compared with the sacrificing of animals, the application of endoscopy in research studies is considered a minimally invasive and more humane method, along with assessing the intestinal condition of the animals and obtaining tissue specimens (35-37).

8. Canine model of human fistulizing CD

Ferrer et al (38) reported that canine anal furunculosis (CAF) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of perianal fistula in dogs. Dogs may naturally develop an immune disease, which has several characteristics in common with human CD-induced fistula (39,40). These studies used spontaneous perianal fistula as a CD model of fistulostomy. Human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived MSCs were injected into each fistula at the same time to treat CAF. The therapeutic potential and safety of intracerebral injection of stem cells from different sources were evaluated by recording the number and depth of the fistulas at 6 months following treatment and the average daily dose of cyclosporin required to prevent injury in the dogs. The results indicated that hESC-MSCs were well tolerated. At 1 month after surgery, the expression levels of serum IL-2 and IL-6 were decreased. The data indicated that the inflammatory cytokines IL-2 and IL-6 were associated with the development of CD (41). A previous study demonstrated the safety and therapeutic potential of hESC-MSCs in large animal models (38). This study for Canine model of human fistulizing CD was the first preliminary evidence indicating the use of pluripotent stem cell-derived therapy for the treatment of fistulas in a large animal model (38). The treatment of spontaneous canine fistula with expanded hESCs supports the concept that canine models may be used to evaluate cell therapy. However, this was an open trial and, as a result, the efficacy was not compared with any placebo group. In the absence of a predictable time of onset or the inability to easily induce fistula, this model has limited applicability to preclinical studies.

Dogs exhibit high similarity with humans in terms of the anal muscles, glands and biological functions, and they are considered as one of the few animal species with the type of anal gland suitable for inducing anal fistula formation. Due to the complex animal ethics and experimental methodology, only a small number of studies have been performed using canine models. It has been suggested that endoscopy should be used in experiments with large animals, as it is simple and may reduce the level of trauma to animals (35,37). Furthermore, endoscopy may be used repeatedly to obtain a more accurate assessment of the disease status.

9. Discussion

Several issues regarding perianal CD have remained to be thoroughly addressed. The majority of the causes of anal fistula originate from anorectal abscess, whereas certain cases of anal fistula involve inflammatory diseases of the anorectal region, such as CD and tuberculosis (42). Previous studies have indicated that two mechanisms appear to have a major role in the development of CD: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and matrix-remodeling enzymes (43). The expression levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) enzymes have exhibited a significant increase following the development of fistula in CD (43). This effect has been notably observed with regard to MMP3 protein and mRNA levels (44). Clinical observations have indicated that antibiotic therapy and fecal diversion may benefit the management of perianal fistulizing CD, suggesting that the gut microbiota may also be a pathogenic contributor (45). Investigation of the pathogenesis of CD is challenging due to the lack of relevant animal models and the difficulty in obtaining human tissue samples that may accurately reflect the different stages of fistula formation. It has been indicated that certain patients with serious cavity diseases have never had an anal fistula, whereas certain cavity and perianal lesions exhibited inconsistent reactions, indicating that this type of complication may involve specific factors and requires more effective treatment (9).

The present review has certain limitations. First, the literature search included only animal models of fistula formation. As a result, other animal models of CD-associated inflammation were omitted or did not meet the inclusion criteria. However, it must be considered that fistula formation in animal models does not fully reflect the condition in humans. In addition, it is well known that the risk of fistula formation increases with the duration of the disease. Therefore, animal models are either not monitored long enough to observe their long-term condition, or only a limited number of animals develop the disease, which is an accurate reflection of the clinical condition in humans. In addition, animal models of spontaneous fistula formation have been previously reported. Furthermore, clinicians have limited knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of emerging fistulas. The inclusion criteria described in the present study also impose several limitations. Therefore, it is suggested to develop more specific animal models that represent the corresponding clinical condition.

A total of six studies included animal models of CD with anal fistula, of which two model types were used. Of these, one study comprised large animal models, such as pigs and dogs. These are generally considered more similar to humans and may be used to simulate the development of various clinical diseases in humans. However, the experimental conditions used in these animals do not fully represent the clinical condition of CD in humans (46,47). The second type of animal model involved immunodeficient mice. Immunodeficiency may exhibit an inherited predisposition to CD, which may be used to assess the mechanism of perianal CD (19). However, due to their physiological structure, the use of endoscopy in these small animal models to visually assess intestinal morphology is difficult, which limits the overall feasibility of evaluating the disease. Optimal pathological tissue specimens may only be obtained by sacrificing the animals. Therefore, these are not considered ideal models for anorectal diseases. However, medium-sized animals, such as rabbits, may be used to assess CD and perianal disease. Although a rabbit model that resembles human CD perianal fistula is yet to be established, several studies have examined experimental colitis in rabbits (38). The rabbit is considered a medium-to-large size animal. Rabbits are easy to maintain and rabbit models are cost-effective and have satisfactory repeatability and operability. A variety of preclinical rabbit models have been widely reported (48-50). In these models, the auxiliary examinations of the human body, such as ultrasound, CT, MRI and endoscopy, are able to be successfully simulated. It is worth emphasizing that rabbit models allow the use of endoscopy, which is valuable (51). An accumulating number of studies have confirmed that rabbit models of immune deficiency were successfully established (52,53). However, additional experimental data are required to support and confirm the utility of rabbits in preclinical models of perianal fistulizing CD.

It remains necessary, albeit challenging, to establish a suitable preclinical model of CD with anal fistula. This model requires to be assessed with regard to safety, repeatability and clinical similarity to humans. Perianal disease treatment technology may be used for CD. However, an ideal animal model is required. The optimal animal model should include the genetically-mediated development of CD with anal fistula. However, an ideal model for preclinical research is difficult to be established due to the long experimental period required. Therefore, the evaluation and identification of a relatively practical and reliable animal model is required to study CD with anal fistula.

10. Conclusion

In conclusion, a total of six existing preclinical studies of perianal fistulizing CD that focused on intestinal inflammation or fistula were discussed in the present review. Of note, although considerable progress in research on animal models of perianal fistulizing CD has been made, the extrapolation of the basic research data to the clinical setting requires additional study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SL, KZ, YG and EW made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. SL KZ, YG and EW performed the literature search. JH was involved in drafting the manuscript, revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. SL and JH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in olmsted county, minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875–880. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verstockt B, Smith KG, Lee JC. Genome-wide association studies in Crohn's disease: Past, present and future. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(e1001) doi: 10.1002/cti2.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balfour Sartor R. Bacteria in Crohn's disease: Mechanisms of inflammation and therapeutic implications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41 (Suppl 1):S37–S43. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802db364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balfour Sartor R. Enteric microflora in IBD: Pathogens or commensals? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1997;3:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahat A, Assulin Y, Beer-Gabel M, Chowers Y. Endoscopic ultrasound for perianal Crohn's disease: Disease and fistula characteristics, and impact on therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu P, Chen Y, Gu Y, Chen H, An X, Cheng Y, Gao Y, Yang B. Analysis of clinical characteristics of perianal Crohn's disease in a single-center. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2016;19:1384–1388. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.e42, e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panés J, Rimola J. Perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:652–664. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, Holmström B. Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1980;21:525–527. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.6.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, Pascual JA, Del-Valle E, Zorrilla J, De-La-Quintana P, Garcia-Arranz M, Pascual M. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: A phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:79–86. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181973487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryska O, Serclova Z, Mestak O, Matouskova E, Vesely P, Mrazova I. Local application of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells supports the healing of fistula: Prospective randomised study on rat model of fistulising Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroentero. 2017;52:543–550. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1281434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bültmann O, Philipp C, Ladeburg M, Berlien HP. Creation of a caecostoma in mice as a model of an enterocutaneous fistula. Res Exp Med (Berl) 1998;198:215–228. doi: 10.1007/s004330050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: A phase 3 randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flacs M, Collard M, Doblas S, Zappa M, Cazals-Hatem D, Maggiori L, Panis Y, Treton X, Ogier-Denis E. Preclinical model of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:687–696. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soker G, Gulek B, Yilmaz C, Kaya O, Arslan M, Dilek O, Gorur M, Kuscu F, İrkorucu O. The comparison of CT fistulography and MR imaging of perianal fistulae with surgical findings: A case-control study. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016;41:1474–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0722-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camoglio L, Te Velde AA, de Boer A, ten Kate FJ, Kopf M, van Deventer SJ. Hapten-induced colitis associated with maintained Th1 and inflammatory responses in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1486–1495. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1486::AID-IMMU1486>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera-Nieves J, Bamias G, Vidrich A, Marini M, Pizarro TT, McDuffie MJ, Moskaluk CA, Cohn SM, Cominelli F. Emergence of perianal fistulizing disease in the SAMP1/YitFc mouse, a spontaneous model of chronic ileitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:972–982. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto S, Okabe Y, Setoyama H, Takayama K, Ohtsuka J, Funahashi H, Imaoka A, Okada Y, Umesaki Y. Inflammatory bowel disease-like enteritis and caecitis in a senescence accelerated mouse P1/Yit strain. Gut. 1998;43:71–78. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruckner RS, Nissim-Eliraz E, Marsiano N, Nir E, Shemesh H, Leutenegger M, Gottier C, Lang S, Spalinger MR, Leibl S, et al. Transplantation of human intestine into the mouse: A novel platform for study of inflammatory enterocutaneous fistulas. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:798–806. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savidge TC, Morey AL, Ferguson DJ, Fleming KA, Shmakov AN, Phillips AD. Human intestinal development in a severe-combined immunodeficient xenograft model. Differentiation. 1995;58:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5850361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scharl M, Huber N, Lang S, Fürst A, Jehle E, Rogler G. Hallmarks of epithelial to mesenchymal transition are detectable in Crohn's disease associated intestinal fibrosis. Clin Transl Med. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.1186/s40169-015-0046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scharl M, Rogler G. Pathophysiology of fistula formation in Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:205–212. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharl M, Frei P, Frei SM, Biedermann L, Weber A, Rogler G. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in a fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma in a patient with long-standing Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:114–118. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32836371a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frei SM, Hemsley C, Pesch T, Lang S, Weber A, Jehle E, Rühl A, Fried M, Rogler G, Scharl M. The role for dickkopf-homolog-1 in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease-associated fistulae. PLoS One. 2013;8(e78882) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scharl M, Weber A, Fürst A, Farkas S, Jehle E, Pesch T, Kellermeier S, Fried M, Rogler G. Potential role for SNAIL family transcription factors in the etiology of Crohn's disease-associated fistulae. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1907–1916. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nissim-Eliraz E, Nir E, Shoval I, Marsiano N, Nissan I, Shemesh H, Nagy N, Goldstein AM, Gutnick M, Rosenshine I, et al. Type three secretion system-dependent microvascular thrombosis and ischemic enteritis in human gut xenografts infected with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2017;85:e00558–17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00558-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demeyer A, Van Nuffel E, Baudelet G, Driege Y, Kreike M, Muyllaert D, Staal J, Beyaert R. MALT1-deficient mice develop atopic-like dermatitis upon aging. Front Immunol. 2019;10(2330) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peintner L, Venkatraman A, Waeldin A, Hofherr A, Busch T, Voronov A, Viau A, Kuehn EW, Köttgen M, Borner C. Loss of PKD1/polycystin-1 impairs lysosomal activity in a CAPN (calpain)-dependent manner. Autophagy. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1826716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dryden GW, Boland E, Yajnik V, Williams S. Comparison of stromal vascular fraction with or without a novel bioscaffold to fibrin glue in a porcine model of mechanically induced anorectal fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1962–1971. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan GN, Sibbons P, Osborn M, Bartram CI, Ansari T, Halligan S, Cohen CR. Experimental model of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:353–356. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehg KL, Sanchez JE, Krieger BR, Marcet JE. Fecal diversion in perirectal fistulizing Crohn's disease is an underutilized and potentially temporary means of successful treatment. Am Surg. 2009;75:715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Al-Mishlab TG, Stromberg AJ. Perianal Crohn disease: Predictors of need for permanent diversion. Ann Surg. 2005;241:796–801. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161030.25860.c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.A Ba-Bai-Ke-Re MM, Chen H, Liu X, Wang YH. Experimental porcine model of complex fistula-in-ano. World J Gastroentero. 2017;23:1828–1835. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i10.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radefeld K, Papp S, Havlicek V, Morrell JM, Brem G, Besenfelder U. Endoscopy-mediated intratubal insemination in the cow-development of a novel minimally invasive AI technique. Theriogenology. 2018;115:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobel DS. Upper respiratory tract endoscopy in the cat: A minimally invasive approach to diagnostics and therapeutics. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15:1007–1017. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13508252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salavati M, Pérez-Accino J, Tan YL, Liuti T, Smith S, Morrison L, Salavati Schmitz S. Correlation of minimally invasive imaging techniques to assess intestinal mucosal perfusion with established markers of chronic inflammatory enteropathy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:162–171. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrer L, Kimbrel EA, Lam A, Falk EB, Zewe C, Juopperi T, Lanza R, Hoffman A. Treatment of perianal fistulas with human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: A canine model of human fistulizing Crohn's disease. Regen Med. 2016;11:33–43. doi: 10.2217/rme.15.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.House AK, Gregory SP, Catchpole B. Pattern-recognition receptor mRNA expression and function in canine monocyte/macrophages and relevance to canine anal furunuclosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;124:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massey J, Short AD, Catchpole B, House A, Day MJ, Lohi H, Ollier WE, Kennedy LJ. Genetics of canine anal furunculosis in the German shepherd dog. Immunogenetics. 2014;66:311–324. doi: 10.1007/s00251-014-0766-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patterson AP, Campbell KL. Managing anal furunculosis in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2005;27:339–355. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.025. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1–12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800630102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirkegaard T, Hansen A, Bruun E, Brynskov J. Expression and localisation of matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in fistulae of patients with Crohn's disease. Gut. 2004;53:701–709. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.017442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seow-Choen F, Hay AJ, Heard S, Phillips RK. Bacteriology of anal fistulae. Br J Surg. 1992;79:27–28. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazzoni M, Caremoli F, Cabanillas L, de Los Santos J, Million M, Larauche M, Clavenzani P, De Giorgio R, Sternini C. Quantitative analysis of enteric neurons containing choline acetyltransferase and nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivities in the submucosal and myenteric plexuses of the porcine colon. Cell Tissue Res. 2021;383:645–654. doi: 10.1007/s00441-020-03286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Li F, Wang H, Yin C, Huang J, Mahavadi S, Murthy KS, Hu W. Immune/Inflammatory response and hypocontractility of rabbit colonic smooth muscle After TNBS-induced colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1925–1940. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4078-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murai K, Hamamoto S, Okuma T, Kageyama K, Yamamoto A, Ogawa S, Nota T, Sohgawa E, Jogo A, Miki Y. Survival benefit of radiofrequency ablation with intratumoral cisplatin administration in a rabbit VX2 lung tumor model. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2021;44:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02686-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schilling AL, Moore J, Kulahci Y, Little SR, Rigatti LH, Wang EW, Lee SE. Evaluating inflammation in an obstruction-based chronic rhinosinusitis model in rabbits. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11:807–809. doi: 10.1002/alr.22729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boissady E, Kohlhauer M, Lidouren F, Hocini H, Lefebvre C, Chateau-Jouber S, Mongardon N, Deye N, Cariou A, Micheau P, et al. Ultrafast hypothermia selectively mitigates the early humoral response after cardiac arrest. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(e017413) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang J, Shuang J, Xiong G, Wang X, Zhang Y, Tang X, Fan Z, Shen Y, Song H, Liu Z. Establishing a rabbit model of malignant esophagostenosis using the endoscopic implantation technique for studies on stent innovation. J Transl Med. 2014;12(40) doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hashikawa Y, Hayashi R, Tajima M, Okubo T, Azuma S, Kuwamura M, Takai N, Osada Y, Kunihiro Y, Mashimo T, Nishida K. Generation of knockout rabbits with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci Rep. 2020;10(9957) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66780-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song J, Wang G, Hoenerhoff MJ, Ruan J, Yang D, Zhang J, Yang J, Lester PA, Sigler R, Bradley M, et al. Bacterial and pneumocystis infections in the lungs of gene-knockout rabbits with severe combined immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2018;9(429) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.