Abstract

Educational assortative mating patterns in the U.S. have changed since the 1960s, but we know little about the effects of these patterns on children, particularly on infant health. Rising educational homogamy may alter prenatal contexts through parental stress and resources, with implications for inequality. Using 1969–1994 NVSS birth data and aggregate cohort-state census measures of spousal similarity of education and labor force participation as instrumental variables (IV), this study estimates effects of parental educational similarity on infant health. Controlling for both maternal and paternal education, results support family systems theory and suggest that parental educational homogamy is beneficial for infant health while hypergamy is detrimental. These effects are stronger in later cohorts and are generally limited to mothers with more education. Hypogamy estimates are stable by cohort, suggesting that rising female hypogamy may have limited effect on infant health. In contrast, rising educational homogamy could have increasing implications for infant health. Effects of parental homogamy on infant health could help explain racial inequality of infant health and may offer a potential mechanism through which inequality is transmitted between generations.

Declining birth weights in the U.S. raise concern about infant health and future generations (Donahue et al. 2010). Maternal and neonatal characteristics do not explain these declines (Donahue et al. 2010), which leaves open the possibility that other demographic trends could be related to changes in infant health. Evidence suggests educational assortative mating (the nonrandom matching of romantic partners with respect to education) has increased in the U.S. since the 1960s, particularly among the college educated (Schwartz and Mare 2005; Breen and Salazar 2011). These trends have implications for inequality of childhood contexts (Schwartz 2013; Western et al. 2008; Burtless 1999). However, family systems theory (Kerr 2000; Minuchin 1985) suggests that this educational sorting may also have implications for infant health through prenatal context. For example, parental educational similarity may shape prenatal conditions through maternal stress (e.g., Zhang et al. 2012; Beck and Gonzalez-Sancho 2009), which has implications for a variety of infant health measures (Dancause et al. 2011; Torche 2011; Torche and Kleinhaus 2011; Beijers et al. 2010). Thus, parental educational sorting could influence infant health through its influence on prenatal environment.

The relationship between maternal education and child health is well established (Gunes 2015; Abuya et al. 2012). Even in infancy, maternal education is critical for early measures of health (Currie and Moretti 2003). Although less research has examined the importance of father’s education (Case et al. 2002), some evidence also suggests father’s education is important for child health (Chen and Li 2009; Cochrane et al. 1982). Despite a great deal of attention to the importance of absolute levels of education, however, surprisingly little research has investigated whether the relative similarity of maternal and paternal education also has implications for infant health.

Drawing on family systems theory (Kerr 2000; Minuchin 1985), I use administrative birth and infant health data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) from 1969 to 1994 to examine three questions:

Is parental educational homogamy associated with improved infant health?

If parents have unequal education, does infant health differ depending on which parent has higher education?

Do results differ by maternal cohort? Women’s college entry rates surpassed those of men among cohorts born in the mid-1950s (Bailey and Dynarski 2011). Women’s college graduation rates approximately equaled those of men among cohorts born in the late 1950s and surpassed those of men among cohorts born in the early 1960s (DiPrete and Buchmann 2013). Given changes in potential relationship partners, do results differ among births to mothers born before and after 1956, the cohort in which women surpassed men in college entry and caught men in graduation rates?

The period from 1969 to 1994 includes maternal cohorts both before and after women surpassed men in college education (DiPrete and Buchmann 2013; Bailey and Dynarski 2011). Women now comprise nearly half the U.S. work force (U.S. Department of Labor 2012) and are increasingly independent earners, which could make educational hypogamy or homogamy more appealing. Examining this time period provides insight into the potential implications of growing gender inequality in college graduation and changing marital sorting patterns for infant health.

This study departs from most previous research by: 1) Studying implications of educational assortative mating for infant health; 2) Examining assortative mating among parents rather than all couples. Educational sorting is related to the likelihood and timing of fertility (Nomes and Van Bavel 2016; Nitsche et al. 2018) and couples who produce a child together represent a different population than those who are married or even living together. Evidence from the U.S. in the 1990s suggests the likelihood of homogamy is stronger among parents than married couples (Mare and Schwartz 2006), yet few studies investigate educational sorting among parents (Mare and Schwartz 2006; Goldstein and Harknett 2006; Garfinkel et al. 2002); 3) Using data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), which includes administrative information based on the population of births in the U.S.; and 4) Using instrumental variable (IV) analyses to assess robustness of ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates. Existing research on educational homogamy relies on descriptive techniques, tracing trends in the prevalence and strength of sorting over time or factors associated with those changes (for reviews see Schwartz 2013; Blossfeld 2009; Kalmijn 1998). Potential selection concerns make it important to move beyond associational techniques to approach a causal estimate.

Background

Educational Sorting and Inequality

Given growing gender inequality among college-goers (DiPrete and Buchmann 2013), women with a college education face an increasing likelihood of educational hypogamy (i.e. marrying a man with less education). As college enrollment rates rise among 18- to 24-year-olds (NCES 2011), educational sorting patterns may change among younger cohorts. For example, educational hypogamy or homogamy among women may increase. Learning about the implications of marital sorting in earlier cohorts, particularly among cohorts in which women reached equality with men in college graduation rates, may help anticipate potential consequences of these changes in future years. For example, if trends in educational sorting patterns have implications for infant health, obstetricians and other medical practitioners may be able to serve patients and protect infants more knowledgeably.

Beyond infant health, spousal educational similarity also has implications for inequality (Greenwood et al. 2016; Eika et al. 2017; Schwartz 2013; Breen and Salazar 2011; Western et al. 2008; Kalmijn 1998). By pooling resources, for example, spousal similarity could increase income disparities between households and expand variation in early childhood experiences and contexts (Schwartz 2013; Schwartz and Mare 2005; Blossfeld 2009; Burtless 1999), with consequences for children’s educational chances and the transmission of inequality across generations (Fernandez and Rogerson 2001; Kremer 1997). Edwards and Roff (2016), for example, find that assortative mating is associated with higher cognitive test scores for children, but data limitations prevent the identification of mechanisms for this relationship. One potential mechanism for the link between parental educational similarity and child cognitive or educational outcomes is prenatal context.

Educational Sorting and Family Processes

Family systems theory suggests that families operate as a unit, with complex emotional interactions and interdependencies (Kerr 2000; Minuchin 1985; Fletcher 2009; Gihleb and Lifshitz 2016). Sociologists may conceive of these interactions as social capital (e.g., Furstenberg 2005). Economists may think of them as externalities (e.g., Becker 1981). Regardless of the name assigned, there is agreement across fields that the interactions and interrelationships among family members and their characteristics have implications for the family and its members.

Applied to education, family systems theory suggests that – beyond the absolute level of education – the relative education of parents should also have implications for the family. Although we know that a mother’s level of education is critical for the health of her infant (Currie and Moretti 2003), family systems theory suggests that a mother’s education relative to the father’s may also have implications for infant health. Specifically, maternal educational homogamy (partner has equal education), hypergamy (partner has more education), and hypogamy (partner has less education) may each have different implications for infant health.

A potential explanation for a relationship between parental educational homogamy and infant health is stress. Specifically, parental educational homogamy could improve infant health by reducing prenatal maternal stress. Educational dissimilarity is associated with a higher likelihood of divorce (Goldstein and Harknett 2006) and relationship instability (Garfinkel et al. 2002), although the authors are careful to point out that these are descriptive differences. Continued affiliation with the father throughout the pregnancy has implications for economic and emotional support of the mother and baby. For example, the father can help shoulder the burden of preparing for and caring for a new baby. Thus, educational homogamy could reduce maternal anxiety about her relationship with the father and maternal stress about her ability to support and care for her child after its birth. In addition to relationship anxiety, educational similarity could reduce maternal stress due to agreement when making decisions. Parents with equal education may agree more on parenting practices and family allocation of time and resources (Beck and Gonzalez-Sancho 2009; Martin et al. 2007). For example, parental agreement about such things as medical screening and breastfeeding could reduce maternal stress during pregnancy.

Prenatal stress accounts for approximately 10% of the variation in a variety of infant health measures (Beijers et al. 2010). Studies that take advantage of variation in the timing of natural disasters and stage of pregnancy consistently find a relationship between prenatal maternal stress and birth outcomes, including birth weight, gestation length, and birth length (Dancause et al. 2011; Torche 2011; Torche and Kleinhaus 2011). Maternal stress is thought to promote production of placental corticotropin-releasing hormone, which is related to shorter gestational periods, preterm delivery, and lower birth weight (Torche 2011; Hobel and Culhane 2003; Lockwood 1999).

Based on family systems theory, hypothesis 1 is that parental educational homogamy improves infant health. However, these benefits may only accrue to those with higher education. For example, relationship dissolution is most likely among those with low levels of education (Theunis et al. 2017; Lyngstad 2004). Maternal stress may be lower among those with similarly high levels of education due to pooled economic resources (Oppenheimer 1997) and a more egalitarian division of childcare or housework (Bonke and Esping-Andersen 2011). Therefore, hypothesis 1a is that benefits of educational homogamy are limited to mothers with relatively higher education.

Unequal Education and Infant Health: Variation by Cohort

Among parents with unequal education, the direction of difference may have implications for infant health. Maternal hypergamy is the more traditional relationship pattern (Esteve et al. 2012; Schwartz and Mare 2005) and could be associated with higher relationship stability due to better fit with social norms. However, hypergamy became less common and became associated with higher divorce rates in recent cohorts (Theunis et al. 2017; Schwartz and Han 2014). Some evidence suggests hypogamy is associated with lower marital satisfaction (Zhang et al. 2012; Butterworth et al., 2008; Tzeng, 1992), which could increase divorce rates and maternal stress. In fact, divorce rates were highest among hypogamous couples in marriages formed in the 1950s (Schwartz and Han 2014). However, divorce risk among hypogamous couples decreased over time as hypogamy increased (Schwartz and Han 2014).

While much of the research on hypergamy and hypogamy examines relatively recent or narrow ranges of marriage cohorts (e.g., Zhang et al. 2012), this study covers a wide range of maternal cohorts during which hypogamous relationships became more common in the U.S. and were no longer associated with higher divorce risk (Schwartz and Han 2014). Given changes in the relationship between educational sorting and marital stability over time, the implications of hypogamy and hypergamy for infant health may differ by maternal cohort.

Based on the above discussion, hypothesis 2 is that hypergamy and hypogamy are related to infant health, but the relationship differs by maternal cohort. Specifically, hypothesis 2a is that maternal hypergamy is associated with improved infant health in earlier cohorts, but lower infant health in later cohorts. In contrast, hypothesis 2b is that maternal hypogamy is associated with improved infant health in later cohorts, but lower infant health in earlier cohorts. Finally, partly because stability of homogamous marriages has increased over time (Schwartz and Han 2014), hypothesis 2c is that the infant health benefits of educational homogamy are larger in later cohorts.1 Table 1 summarizes these hypotheses.

Table 1:

Relationship between Relative Parental Education and Infant Health

| Panel A: Hypotheses | ||

| Relative Parental Education | Mothers Born <1956 | Mothers Born 1956+ |

| Mother Has Lower Education | + | − |

| Mother Has Equal Education | + | ++ |

| Mother Has Higher Education | − | + |

| Panel B: Findings | ||

| Relative Parental Education | Mothers Born <1956 | Mothers Born 1956+ |

| Mother Has Lower Education | − | −− |

| Mother Has Equal Education | + | ++ |

| Mother Has Higher Education | − | − |

Hypothesis 1a predicts benefits of equal parental education are limited to mothers with more education.

Hypothesis 1a is supported. Table represents findings of OLS analyses (Table 6, Panel A). IV estimates suggest null effects of maternal hypogamy.

Methods

Data

I use NVSS Birth Data, which provide administrative birth information for a large sample of the annual population of live births in the U.S. I limit analyses to years (1969–1994) with information about both maternal and paternal education. (Starting in 1995, the NVSS birth data did not include paternal education.) Based on administrative records, these data provide the most complete and accurate information about births in the U.S. The number of observations included in NVSS data make finding a significant result highly likely and would overwhelm most personal computers. To increase feasibility and address concerns about rising number of births over time, I take a random sample of 100,000 births with complete parental education in each year from 1969 to 1994.2 Including the same number of births in each year avoids the need for weights (to prevent years with higher numbers of births from driving results). Descriptive statistics of the random sample are similar to those from the full sample.

The total possible sample size over all 26 years is 2,599,596 births. However, sample sizes in regression models are smaller due to missing values. In most cases, the proportion of births with missing data is small. For example, 0.3% of births are missing birth weight. In other cases, the proportion missing is higher because some states did not provide complete information, particularly in early years. For example, no states reported the number of prenatal visits until 1972. In 1972, New York state only reported the number of prenatal visits for 0.3% of births. In 1994, NY reported this information for 95.3% of births. Because the majority of missing data is due to incomplete state reporting, it is largely missing at random with respect to individual birth outcomes. However, the rate of missing data varies systematically over time and by state, with higher rates of missing data in early years. Controlling for year of birth and county fixed effects help address this issue in regressions below, but readers should keep in mind that results are less generalizable to early years for models predicting values with higher missing rates (18% missing for number of prenatal visits and 4% for month prenatal care began).

Measures

Education is measured in years of completed education. NVSS data report the highest year of education completed until 2002, so measuring education in years is consistent with the data. Based on the education of both parents, I create indicators for whether the number of years completed by the infant’s mother is lower, equal, or higher than the number of years completed by the father. Sensitivity analyses examine categorical measures of education based on whether parents have the same level of education. Levels include less than high school (<12 years), high school (12 years), some college (13–15 years), and college or more (16 or more years).

I measure infant health in two ways: birth weight (in grams); and an indicator for low birth weight (less than 2,500 grams). A large body of evidence indicates the benefits of healthy birth weight and the short- and long-term risks associated with low birth weight (Conley et al. 2003; Johnson and Schoeni 2011). However, research suggests that high birth weight is also associated with health problems (Koifman et al. 2008; Johnsson et al. 2015). Higher birth weight values typically indicate better health, but I also predict an indicator for whether an infant is low birth weight to address concerns that higher values may not indicate better health at all levels.

Frequent and early prenatal care may help reduce the likelihood of low birth weight and infant mortality (Joyce et al. 1988; Conway and Deb 2005; Evans and Lien 2005). Because parental educational similarity may influence infant health partly through prenatal medical care, I also estimate its relationship with two measures of prenatal care: the number of prenatal medical visits during pregnancy; and the month of pregnancy in which prenatal care began.

I control for several factors that could be associated with both parental educational similarity and infant health. These include maternal education, age, race (an indicator for non-white), paternal education, sex of the infant (an indicator for male), year the infant was born, and county of maternal residence. I use county of residence because where a woman lives should have more of an impact on the health of her infant than where she is at the moment of birth. By controlling for county of residence, I account for any time-constant county differences in infant health. Counties with better access to medical care or in states that invest more in prenatal care, for example, could have consistently better infant health than others. Controlling for year of infant birth addresses potential changes over time in infant health. For example, anti-smoking efforts could improve average infant birth weight over time.

Analytical Approach

Analyses proceed in four steps. First, I document mean differences in outcomes between births by similarity of parental education. Second, I use OLS models to estimate the relationship between parental educational similarity and infant health, controlling for maternal education, age, and race, paternal education, child sex, and indicators for each year and county of birth. Third, to test hypotheses 1a and 2a-c, I use z-tests to compare coefficients (Paternoster et al. 1998) by level of maternal education and maternal cohort (born before and after 1956).

IV Analyses

Controlling for both mother’s and father’s education helps address the concern that some other factor is driving both parental educational similarity and infant health. Nevertheless, socioeconomic or racial inequality on the marriage or job markets or maternal preferences for particular characteristics in a partner could influence the similarity of her partner’s education and her infant’s health. Thus, a woman who engages in risk-prone behaviors may be more likely to partner with a man who is very different from herself (e.g., has much lower education) and also behave in ways that reduce fetal health. In that case, educational homogamy should not impact infant health after adjusting for endogeneity.

In a fourth step, I use IV models as a robustness check to help address the potentially endogenous relationship between parental educational similarity and infant health. Unfortunately, given the effect of maternal education on infant health (Currie and Moretti 2003), most factors likely to impact educational sorting would also influence infant health (in violation of the exclusion restriction). Therefore, I use U.S. Census and American Community Survey (ACS) data from IPUMS (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series) (Ruggles et al. 2017) to create state-level measures of the prevalence of assortative mating in each maternal cohort (i.e. among adults who were born in each year of mother’s birth). These instrumental variables should predict the educational similarity of two parents without directly influencing their child’s health.

Specifically, I use census data from 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 and 2010 ACS data to calculate the proportion of married, male household heads from each birth cohort in each state whose spouse has an education level lower than their own. That is, by year of birth and state of residence, these data provide measures of spousal educational similarity among adult, married household heads. Education levels are based on the highest year of school completed and include less than 9th grade, grades 9–11, grade 12, some college (1–3 years), four years of college, and more than four years of college. I also calculate state-cohort mean differences in spousal participation in the labor market (proportion of couples in which only one person is in the labor force). I use weights to adjust these IV measures for unequal likelihood of appearing in the data; however, results are consistent using unweighted IV measures. These state-cohort measures are linked to births based on mother’s birth year and state of residence in the NVSS data and measure spousal similarity among household heads born in the same year as the mother.

The IVs could influence parental educational similarity in several ways, including through social norms or impacts on the marriage pool. For example, if most female residents in a woman’s state who are approximately her age are married to someone of higher education, she may be more likely to partner with someone with higher education as well. Her choice of partner could be influenced by social norms or by friends she sees as role models. Similarly, if most couples in an area specialize (i.e. one participates in the labor force and the other takes care of the home) or occupy traditional gender roles, future parents may follow suit. Women may strive to achieve a relationship similar to those observed around themselves, for example, or emulate married friends, choosing to occupy traditional gender roles or selecting a similarly educated partner if friends and neighbors did the same.

Alternatively, a woman’s partner choice could be influenced by those who remain available on the marriage market. For example, if most residents around a woman’s age marry someone of similar education, that may leave only those with her own education level as potential partners. These are just two potential explanations for how the IVs could influence parental educational similarity. This paper does not attempt to identify or adjudicate among the possible mechanisms, but in all models I test the strength of the relationship between the IVs on one hand, and parental educational similarity and father’s education on the other.

IV models use a two-stage regression approach to estimate the effect of parental educational similarity, corrected for endogeneity, on infant health. Shown in Equations 1 and 2, infant health measures (e.g., birth weight) for each birth (i) in year (j) to mother residing in county (k) in state (l) and born in cohort (m) are predicted based on similarity of parental education, father’s education, and controls. Controls include child sex, year, and maternal education, age, and race.

1st stage:

| (1) |

2nd stage:

| (2) |

For simplicity, I show equations with one measure of educational assortative mating (called Parents Equal Ed – an indicator for whether parents have the same level of education). In combination with maternal education, father’s education determines parental educational similarity. Father’s education, in other words, may be endogenous for the same reasons as parental educational similarity. To include father’s education in IV models, two IVs are required – one to instrument father’s education and one to instrument parental educational similarity. The IVs (educational and labor force similarity, called Ed Sim and LF Sim in Equation 1) represent mean spousal similarity of education and labor force participation among adults in the mother’s state and cohort.

The second stage regression (Equation 2) uses the predicted measures of parental educational similarity and father’s education from the first stage, where the IVs controlled for some exogenous variance. The key parameter is e in the second stage regression. A significant effect of having similarly educated parents using the IV approach would suggest the relationship does not simply reflect selection or unobserved heterogeneity. Identification is based on variation over time in educational sorting patterns or norms. To allow this, the IV models control for a linear measure of year rather than year fixed effects. This approach assumes that educational sorting patterns and infant health measures change linearly over time. Sensitivity analyses include year fixed effects and use variation over maternal cohort for identification (i.e. do not control for maternal age). These models include both county and year fixed effects and control for father’s age rather than mother’s age.

Out of concern about models that use non-linear link functions (Mood 2010), I use linear probability models to predict likelihood of low birth weight. All regressions use Huber-White standard errors adjusted for county-level clustering. Standard errors are corrected for the two-stage approach using Stata’s xtivreg2 command.

Concerns about any instrument include exogeneity (which cannot be tested directly), strength (the IV must substantially affect the endogenous variable), and monotonicity (the IV pushes individuals in only one direction). Applied to this study, the assumptions are that state-cohort prevalence of sorting: 1) impacts an individual infant’s birth outcomes only through the educational similarity of her parents; 2) significantly influences the educational similarity of parents; and 3) does not perversely discourage some adults from forming a relationship with a similarly educated partner. Statistical tests of IV strength and endogeneity of parental educational similarity and paternal education are reported for all models.

While I cannot test exogeneity directly, I can examine census data for evidence of non-monotonicity. For example, as the prevalence of educational assortative mating increases over cohorts, the mean and standard deviation of the gap in years of partner education should decrease. Increases in those measures would suggest violation of the monotonicity assumption. Among household heads born in each year from 1920 to 1982 (the range of maternal cohorts in the birth data), I track the proportion of heads whose spouse has the same level of education, as well as the mean and standard deviation of spousal difference in years of education. Consistent with the monotonicity assumption, the mean and standard deviation of the gap in years of spousal education decrease with the prevalence of educational assortative marriage over cohorts in the census. This cannot confirm but is consistent with monotonicity.

IV analyses should be seen as a robustness check on the OLS analyses. The IV approach increases internal validity, but may produce imprecise or biased estimates due to collinearity or potential violation of the IV assumptions. I present results of multiple IV modeling strategies to assess whether OLS results are robust to addressing potential selection into parental educational similarity.

Sensitivity Analyses

First, because most research on assortative mating investigates married couples, I compare results by parental marital status. Second, I repeat the main analyses including state-specific time trends (indicators for each state interacted with a continuous measure of birth year). Third, I examine results when limited to mothers over age 25, who are more likely to have completed their education. (These analyses are discussed in the Appendix due to potential endogeneity concerns among this sample.) Fourth, I estimate the relationship between infant health measures and the absolute value of the difference in years of parental education. Fifth, given the importance of educational transitions (e.g., Mare 1980), I repeat analyses using measures of educational categories and indicators for whether the mother has a lower, equal, or higher educational category than the father. Sixth, I repeat the main analyses with a measure of average parental years of education, instead of separate measures for each parent. These models use the same approach as the main IV analyses, but instrument parental educational similarity and average parental education. Finally, I repeat analyses including indicators for mothers having both equal and more education in the same model to estimate differences from mothers with less education than the father. These models instrument two parental similarity indicators, but treat father’s education as exogenous with less internal validity.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive information for infants born 1969–1994 and compares mean values for infants born to parents with or without equal education. Means are different (p<0.01) on all measures except sex of the infant and maternal and paternal race. Compared to infants whose parents have unequal education, those born to equally educated parents are higher birth weight, less likely to be low birth weight, have more prenatal medical visits, began prenatal care earlier, have older mothers, and have more educated mothers but less educated fathers. Infants with equally educated parents are born slightly later, consistent with rising homogamy documented by other studies (Schwartz and Mare 2005; Breen and Salazar 2011).

Table 2:

Descriptive Statistics – NVSS Birth Data 1969–1994

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Parents Have Unequal Educ | Parents Have Equal Educ | Diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Weight (grams) | 3356.44 | 587.40 | 3352.42 | 3362.06 | ** |

| Low Birth Weight | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.06 | ** |

| Prenatal Visits | 10.99 | 3.78 | 10.94 | 11.06 | ** |

| Month Began Prenatal Care | 2.79 | 1.55 | 2.82 | 2.75 | ** |

| Mother Has Lower Education | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.00 | n/a |

| Mother Has Equal Education | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | n/a |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.00 | n/a |

| |Diff in Years of Parents’ Educ| | 1.32 | 1.58 | 2.26 | 0.00 | n/a |

| Mother Education (years) | 12.52 | 2.39 | 12.41 | 12.67 | ** |

| Mother Age | 25.98 | 5.37 | 25.96 | 26.01 | ** |

| Mother Non-White | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Mother Married | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.91 | 0.92 | ** |

| Father Education (years) | 12.75 | 2.65 | 12.80 | 12.67 | ** |

| Father Age | 28.61 | 6.27 | 28.78 | 28.36 | ** |

| Father Non-White | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Child Male | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.51 | |

| Year | 1981.51 | 7.50 | 1981.40 | 1981.66 | ** |

| Mother’s State of Residence and Cohort Means | |||||

| Spouse Lower Education | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.31 | ** |

| |Spousal Diff Years of Educ| | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.74 | 0.74 | ** |

| Diff. Labor Force Participation | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.33 | ** |

| N | 2,592,813 | 1,510,436 | 1,082,377 | ||

Source: NVSS Birth Data 1969–1994 linked to maternal state of residence and birth cohort mean measures of spousal educational and labor force similarity from 1970–2000 Census and 2010 ACS. Sample includes all 99,596 births in 1969 with complete maternal and paternal education. For years 1970–1994, a random sample of 100,000 births from each year with complete parental education information is included.

Sample sizes differ for the following measures: prenatal visits N=2,123,887; month began prenatal care N=2,481,007; mother married N=2,309,910; father age N=2,566,860; father non-white N=2,585,922.

Difference column indicates significance of a t-test of the mean difference between births with and without equal parental education.

p<0.01

p<0.05

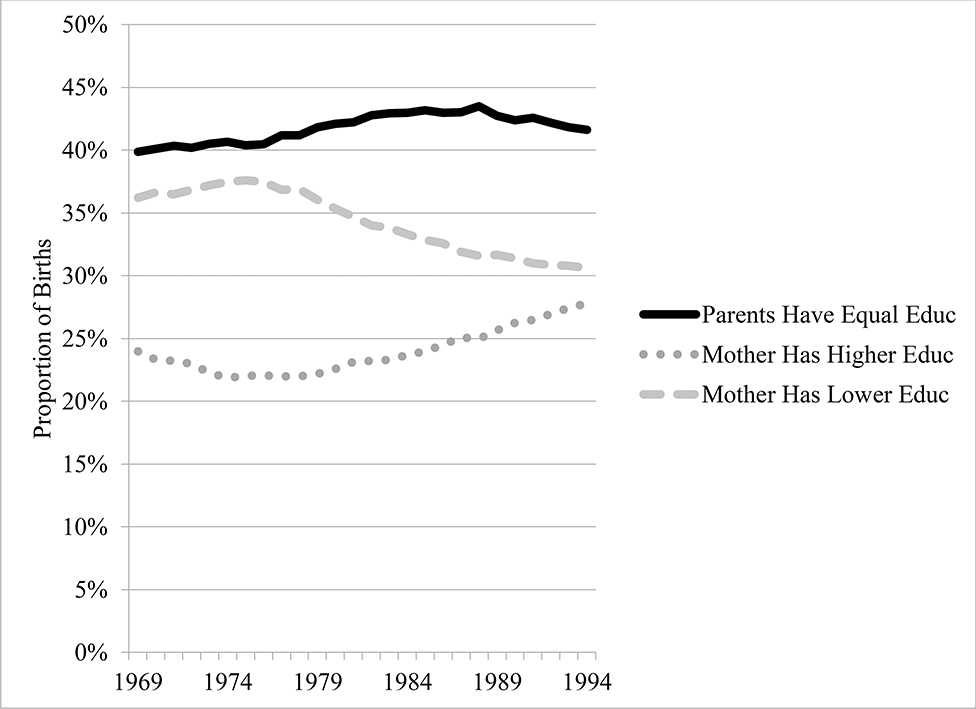

Figure 1 illustrates rising educational assortative mating among parents. The proportion of births to equally educated parents hovered around 40% until the mid-1970s, increased to a high of 43.5% in 1988, and then fell to 41.5% in 1994. At the same time, the proportion of births to hypergamous mothers fell from a high of 37.7% in 1975 to a low of 30.6% in 1994. The proportion of births to hypogamous mothers rose from a low of 21.9% in 1975 to a high of 27.9% in 1994. Figure 1 uses the same sample as regression analyses, but the picture is the same using complete NVSS data.

Figure 1:

Births by Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Cohort, 1969–1994

Source: NVSS Birth Data 1969–1994. Sample is same as in Table 2. Trends are similar using the full population of births in each year. Mother Has Less Educ represents the proportion of births for which the mother has less education than the father (maternal educational hypergamy).

Ordinary Least Squares Analyses

Table 3 presents OLS estimates of the relationship between parental educational similarity and infant health. Panel A suggests that maternal hypergamy is associated with lower birth weight, higher likelihood of being low birth weight, fewer prenatal visits, and later prenatal care (p<0.01). Across all models, both maternal and paternal education are significantly related to better infant health. These estimates are similar in magnitude, suggesting that education is similarly associated with infant health for both parents. However, holding constant the education of each parent, maternal educational hypergamy is also related to infant health. In Model 1, for example, a one-year increase in paternal education is associated with a 7.2-gram increase in birth weight. However, if that additional year makes parents’ education unequal, birth weight is slightly lower (7.2 – 8.6 = −1.4 grams).

Table 3:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: OLS Estimates

| Panel A: Mother Has Less Education than Father | ||||

| VARIABLES | (1) Birth Weight | (2) Low Birth Weight | (3) Prenatal Visits | (4) Month Began Prenatal Care |

| Mother Has Lower Education | −8.60** (109) | 0.004** (0.000) | −0.18** (0.01) | 0.11** (0.00) |

| Mother Education | 6.80** (0.64) | −0.002** (0.000) | 0.14** (0.00) | −0.07** (0.00) |

| Father Education | 7.20** (0.36) | −0.003** (0.000) | 0.15** (0.00) | −0.08** (0.00) |

| Mother Age | 5.76** (0.15) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.02** (0.00) | −0.02** (0.00) |

| Mother Non-White | −197.82** (7.40) | 0.046** (0.002) | −1.10** (0.05) | 0.50** (0.02) |

| Child Male | 125.33** (0.82) | −0.010** (0.000) | −0.04** (0.00) | 0.01** (0.00) |

| Constant | 2,935.53** (7.25) | 0.126** (0.003) | 6.06** (0.13) | 5.41** (0.07) |

| Observations | 2,592,813 | 2,592,813 | 2,126,157 | 2,481,007 |

| R-squared | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Number of Counties | 3,163 | 3,163 | 3,140 | 3,156 |

| County & Year Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Panel B: Parents Have Equal Education | ||||

| VARIABLES | (1) Birth Weight | (2) Low Birth Weight | (3) Prenatal Visits | (4) Month Began Prenatal Care |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 7.09** (0.79) | −0.003** (0.000) | 0.11** (0.01) | −0.07** (0.00) |

| Mother Education | 8.04** (0.64) | −0.002** (0.000) | 0.17** (0.00) | −0.08** (0.00) |

| Father Education | 5.92** (0.30) | −0.002** (0.000) | 0.13** (0.00) | −0.07** (0.00) |

| Mother Age | 5.78** (0.15) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.02** (0.00) | −0.02** (0.00) |

| Mother Non-White | −197.76** (7.40) | 0.046** (0.002) | −1.10** (0.05) | 0.50** (0.02) |

| Child Male | 125.33** (0.82) | −0.010** (0.000) | −0.04** (0.00) | 0.01** (0.00) |

| Constant | 2,930.02** (7.31) | 0.129** (0.003) | 5.95** (0.13) | 5.47** (0.07) |

| Observations | 2,592,813 | 2,592,813 | 2,126,157 | 2,481,007 |

| R-squared | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Number of Counties | 3,163 | 3,163 | 3,140 | 3,156 |

| County & Year Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Panel C: Mother Has More Education than Father | ||||

| VARIABLES | (1) Birth Weight | (2) Low Birth Weight | (3) Prenatal Visits | (4) Month Began Prenatal Care |

| Mom Has Higher Education | −7.87** (1.22) | 0.003** (0.001) | −0.07** (0.01) | 0.05** (0.00) |

| Mother Education | 9.32** (0.71) | −0.003** (0.000) | 0.18** (0.00) | −0.09** (0.00) |

| Father Education | 4.63** (0.33) | −0.002** (0.000) | 0.11** (0.00) | −0.06** (0.00) |

| Mother Age | 5.79** (0.15) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.02** (0.00) | −0.02** (0.00) |

| Mother Non-White | −197.73** (7.40) | 0.046** (0.002) | −1.10** (0.05) | 0.50** (0.02) |

| Child Male | 125.33** (0.82) | −0.010** (0.000) | −0.04** (0.00) | 0.01** (0.00) |

| Constant | 2,934.95** (7.13) | 0.127** (0.002) | 6.01** (0.13) | 5.43** (0.07) |

| Observations | 2,592,813 | 2,592,813 | 2,126,157 | 2,481,007 |

| R-squared | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Number of Counties | 3,163 | 3,163 | 3,140 | 3,156 |

| County & Year Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Notes: Robust standard errors adjusted for county-level clustering in parentheses.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Models predicting low birth weight are linear probability models. Sample is the same as that in Table 2.

Consistent with hypothesis 1, Panel B suggests having equally educated parents is positively related to each measure of infant health (p<0.01), net of maternal and paternal education. For example, an additional year of maternal education is associated with an extra 8 grams at birth. However, when that additional year makes parents’ education equal, it is associated with a 15-gram increase in birth weight (8.0 + 7.1). Similarly, an additional year of paternal education is associated with a 5.9-gram increase in birth weight, but a 13-gram increase if that year makes parents’ education equal (5.9 + 7.1). Results suggest a similar pattern for other infant health outcomes, with a greater return to parental education if it makes parents’ education equal. Thus, if a mother has 12 years of education, her infant is predicted to weigh more at birth, have a lower likelihood of low birth weight, and have more prenatal visits if the father also has 12 years compared to 13 years of education. However, the benefits of an additional year of paternal education outweigh the benefits of having equal education if the father has 2 additional years of education (a total of 14 years in this scenario).

Results in Panel C suggest having a more highly educated mother than father is associated with lower infant health on each measure (p<0.01). For example, in Model 1 an additional year of maternal education is associated with a 9-gram increase in birth weight, but only a 1.4-gram increase if that year makes the mother’s education higher than the father’s (9.3 – 7.9 = 1.4). Similarly, one less year of father’s education is associated with a 4.6-gram decrease in birth weight, but a decrease of 12.5 grams if that year makes the mother’s education higher than the father’s (−4.6 – 7.9 = −12.5).

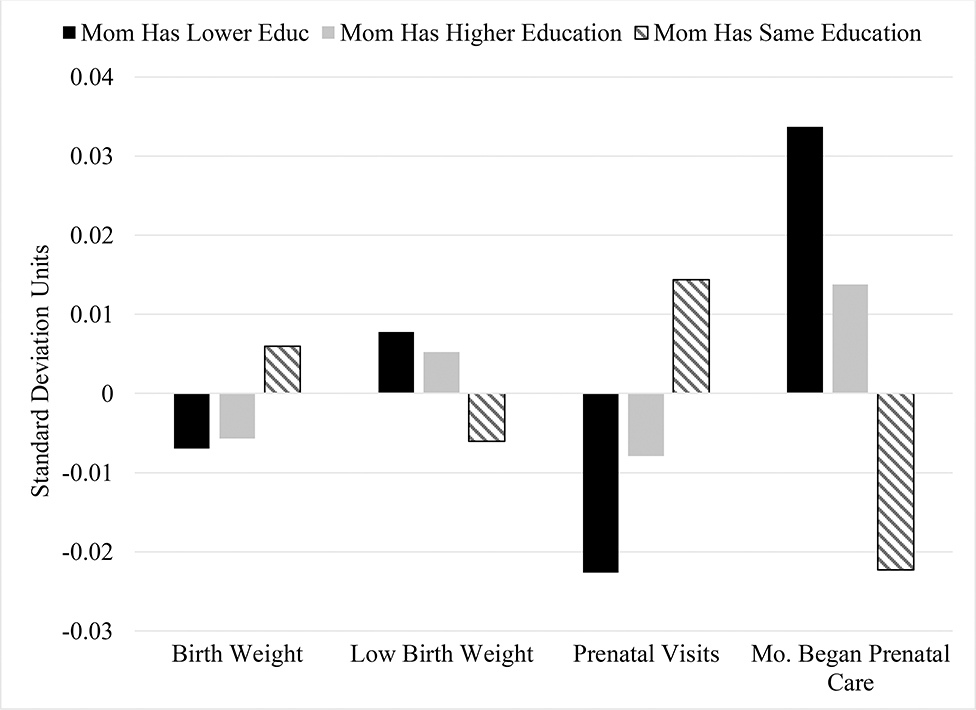

Overall, results in Table 3 are consistent with hypothesis 1 and suggest that having equally educated parents is associated with better infant health. In contrast, Panels A and C indicate that unequally educated parents (both maternal hypergamy and hypogamy) are associated with lower infant health. These results are illustrated in Figure 2, which provides standardized coefficients to allow comparison across models.

Figure 2:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: Standardized OLS Estimates

Source: Table 3. All estimates are significant at p<0.01.

Instrumental Variable Analyses

Table 4 presents results of four IV modelling strategies. The first strategy uses the main approach described in the methods section, controlling for maternal education and instrumenting parental educational similarity and paternal education. To address potential collinearity between parents’ education, strategy 2 excludes maternal education and strategy 3 instruments mean parental education (in place of separate parental measures). Strategy 4 instruments indicators for maternal homogamy and hypogamy, estimating effects compared to hypergamy. These alternative approaches assess robustness, but the first strategy is preferred because it reflects that women make choices in deciding with whom to have a child. One factor in that decision is the amount of education her partner has. Therefore, it is preferable to instrument both parental educational similarity and father’s education.

Table 4:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: IV Estimates

| Modelling Strategy | Birth Weight | Low Birth Weight | Prenatal Visits | Month Began Prenatal Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Including Maternal Education | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −426.29** | −0.06 | −4.50** | 5.16** |

| Mother Has Equal Education | 374.73* | 0.05 | 4.02** | −4.56** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −3,098.80 | −0.44 | −37.52+ | 39.25 |

| 2) Excluding Maternal Education | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −339.80** | −0.06 | −2.65** | 4.04** |

| Mother Has Equal Education | 344.90* | 0.06 | 3.14** | −4.17** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 22,984.29 | 4.04 | 17.1 | −129.54 |

| 3) Using Mean Parental Education | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −324.22** | −0.06 | −2.11* | 3.84** |

| Mother Has Equal Education | 331.14* | 0.07 | 2.52** | −4.00** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 15,518.40 | 3.08 | 12.72 | −100.5 |

| 4) Compared to Mother Has Lower Educ | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | (omitted category) | |||

| Mother Has Equal Education | 341.23** | 0.06 | 2.11+ | −4.07** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 244.66** | −0.12** | 5.60** | −2.88** |

Notes: Sample is the same as that in Table 2, limited to those with data for the instrumental variables (maternal state-cohort mean values of the proportion of male household heads whose spouse has lower education than his own and the proportion whose spouse has different labor force participation than his own). All models control for paternal education, maternal age, indicator for non-white mother, child sex, and year. Robust standard errors adjusted for county-level clustering in parentheses.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Modelling Strategies: 1) Primary IV analyses instrumenting parental educational similarity category and father’s education, controlling for maternal education; 2) Same as strategy 1, but excluding maternal education; 3) Instrumenting parental educational similarity category and mean parental education; 4) Instrumenting two parental educational similarity categories (mother has equal and mother has higher education) and excluding maternal education. Mother has lower education is the omitted category.

Each value in the table is a coefficient from a separate model except for Modelling Strategy 4, where the two coefficients in the same column are estimated in one model compared to mothers with lower education than the father. Tests of IV strength, underidentification, and endogeneity for all models are included with the full tables in Appendix Tables S1–S4.

Nevertheless, results are generally consistent across strategies. For example, strategies 1–3 suggest maternal hypergamy reduces birth weight and number of prenatal visits and delays the start of prenatal care (p<0.05), consistent with OLS estimates. Coefficients predicting low birth weight rarely reach significance in IV models.

Parental homogamy consistently increases birth weight, with estimates ranging from 331 to 375 grams (p<0.05), depending on the strategy. This is about 10% of the sample mean birth weight (331/3356). Black et al. (2007) find that a 10% increase in birth weight increases height in adulthood by almost a centimeter and increases the likelihood of high school completion and adult earnings by about 1%. Thus, this increase in birth weight is small, but not trivial. In addition to the positive effect on birth weight, having homogamous parents predicts 2–4 additional prenatal visits and speeds the start of prenatal care by 4–4.5 months, depending on the strategy.

The full models, along with IV tests, are provided in Appendix Tables S1–4. Measures of IV strength are above the Stock and Yogo (2005) critical value of 10% in models estimating effects of homogamy and hypergamy, suggesting strong IVs. Endogeneity tests of parental educational similarity and father’s education suggest they are endogenous in these models, justifying the IV approach. Underidentification tests indicate that models estimating hypergamy and hypogamy are identified (p<0.01). Thus, IV results support hypothesis 1, that parental educational homogamy improves infant health.

Strategies 1–3 suggest maternal hypogamy is not significantly related to infant health. In contrast to OLS results, this could indicate no effects of maternal hypogamy. However, the IVs are weak and the models are underidentified. Strategy 4 suggests hypogamy improves infant health compared to hypergamy – even more than homogamy when predicting likelihood of low birth weight and prenatal visits. However, given the inconsistent results across strategies and weak IVs in most models, results for hypogamy are inconclusive.

Figure 3 provides standardized coefficients from the first strategy in Table 4. Summarizing the IV results, the figure illustrates that having a less educated mother than father reduces birth weight and prenatal visits and delays prenatal care. In contrast, having equally educated parents improves those outcomes. Overall, IV results suggest OLS estimates are robust to addressing endogeneity when estimating effects of maternal hypergamy and homogamy. Controlling for the absolute level of parental education, these results suggest a health advantage for infants having equally educated parents and a disadvantage for those having a less educated mother than father during the 1969 to 1994 period.

Figure 3:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: Standardized IV Estimates

Source: Table 4 Strategy 1. Tests of IV strength for mother having higher education are weak, so estimates are not shown. * p<0.05); ** p<0.01

Sensitivity analyses including year fixed effects and using variation over maternal cohort for identification (i.e. excluding maternal age from the controls) are presented in Table S10. Models include both county and year fixed effects and control for father’s rather than mother’s age. Consistent with Table 4, estimates suggest parental educational homogamy increases birth weight and hypergamy decreases it (p<0.01). However, the estimates are implausibly large, suggesting the models are likely misspecified. For example, identifying off of variation in maternal cohort may overestimate the first stage effect of the IV (which varies by maternal cohort). Therefore, the more conservative results in Table 4 are preferred.

Variation by Maternal Education

To test hypothesis 1a, Table 5 compares coefficients among mothers with less than high school, high school, some college, and a bachelor’s degree. OLS results (Panel A) suggest that benefits of parental homogamy are limited to mothers with high school or more. Specifically, parental educational homogamy is positively associated with all infant health measures (p<0.01) among births to mothers with a high school education. Homogamy is also associated with lower likelihood of low birth weight and earlier prenatal care among births to mothers with some college (p<0.05). In contrast, educational homogamy is negatively associated with prenatal care measures when the mother has less than high school (p<0.01). IV results (Panel B) indicate that homogamy speeds the start of prenatal care among moms with high school (p<0.01). It also increases birth weight and prenatal visits and speeds prenatal care (p<0.01), but only when the mother has some college education. In contrast, homogamy reduces infant health measures among mothers with less than high school. Thus, IV and OLS results support hypothesis 1a, suggesting benefits of homogamy are limited to mothers with more education. Furthermore, results suggest that negative effects of hypergamy are found primarily among births to mothers with at least some college education.

Table 5:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: by Maternal Education

| Panel A: OLS Estimates | ||||

| Maternal Education Category | Birth Weight | Low Birth Weight | Prenatal Visits | Month Began Prenatal Care |

| Less than HS | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | 4.66+ | 0.001 | 0.22** | −0.07** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | −2.59 | 0.000 | −0.17** | 0.06** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −1.40 | −0.002 | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| HS | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | 9.76** | −0.002** | −0.06** | 0.04** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 5.96** | −0.002** | 0.19** | −0.10** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −27.47** | 0.007** | −0.46** | 0.24** |

| Some College | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | 0.44 | 0.001 | −0.11** | 0.08** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 2.97 | −0.002* | 0.02 | −0.03** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −5.36* | 0.002+ | 0.07** | −0.03** |

| BA | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | 2.02 | −0.001 | −0.08** | 0.03** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | −1.65 | 0.000 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 1.64 | 0.001 | 0.11** | −0.05** |

| Panel B: IV Estimates | ||||

| Maternal Education Category | Birth Weight | Low Birth Weight | Prenatal Visits | Month Began Prenatal Care |

| Less than HS | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −3,397.75 | 1.35 | −140.08 | 28.59 |

| Parents Have Equal Education | −1,265.28* | 0.50+ | −19.32* | 11.15* |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 921.96* | −0.37* | 16.98** | −8.02** |

| HS | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −188.68 | −0.06 | −2.68 | 7.41** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 71.25 | 0.02 | 1.19 | −2.84** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −114.49 | −0.03 | −2.13 | 4.60** |

| Some College | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −1,404.54** | 0.18+ | −8.49** | 6.14** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 1,246.10** | −0.16+ | 9.01** | −5.51** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −11,046.96 | 1.45 | 148.63 | 53.79 |

| BA | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −394.08 | −0.19 | −8.32 | 3.63* |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 795.18 | 0.38 | 23.62 | −7.97 |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 781.28 | 0.37 | 12.85 | −6.66* |

Notes: Coefficients are from OLS models predicting infant health with controls for mother’s education, age, race, father’s education, child sex, and county and year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are adjusted for county-level clustering.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Models predicting low birth weight are linear probability models. Sample is the same as that in Table 2, but limited to infants whose mothers have less than 12 years of education (Less than HS), 12 years (HS), 13-15 years (Some College), or more than 15 years of education (BA).

Sample sizes by maternal education category: <HS birth weight N=531,473; prenatal visits N=407,830; month began prenatal care N=501,590 HS birth weight N=1,125,593; prenatal visits N=901,872; month began prenatal care N=1,075,995 Some College birth weight N=503,566; prenatal visits N=434,723; month began prenatal care N=485,623 BA birth weight N=432,181; prenatal visits N=381,732; month began prenatal care N=417,799

Notes: Coefficients are from IV models predicting infant health with controls for mother’s education, age, race, father’s education, child sex, year, and county fixed effects. Instruments are the same as those used in the main analyses (Table 4 Strategy 1 or see Table S1 for full details). Robust standard errors are adjusted for county-level clustering.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Models predicting low birth weight are linear probability models. Sample is the same as that in Table 2, but limited to infants with information for the instrumental variables and whose mothers have less than 12 years of education (Less than HS), 12 years (HS), 13-15 years (Some College), or more than 15 years of education (BA).

Sample sizes by maternal education category: <HS birth weight N=531,405; prenatal visits N=407,753; month began prenatal care N=501,512 HS birth weight N=1,125,545; prenatal visits N=901,828; month began prenatal care N=1,075,946 Some College birth weight N=503,515; prenatal visits N=434,666; month began prenatal care N=485,564 BA birth weight N=432,103; prenatal visits N=381,648; month began prenatal care N=417,718

Variation by Maternal Cohort

To test hypotheses 2a-c, Table 6 compares the relationship between parental educational sorting and infant health among mothers born before and after 1956. OLS results (in Panel A) suggest a stronger negative association between maternal hypergamy and infant health among later maternal cohorts. For example, having a less educated mother than father was associated with a birth weight decrease of 2.2 grams when the mother was born before 1956, but a decrease of 13.2 grams among mothers from later cohorts. The coefficients for maternal hypergamy are consistently larger in magnitude among births to later maternal cohorts, compared to mothers born before 1956 (p<0.05). These results are partially consistent with hypothesis 2a: maternal hypergamy is more strongly associated with lower infant health in later cohorts, but in early cohorts it is still associated with lower (not higher) infant health.

Table 6:

Relationship between Parental Educational Similarity and Infant Health: Before and After 1956 Maternal Cohort

| Panel A: OLS Estimates | ||||

| Birth Weight | Low Birth Weight | PrenatalVisits | Month Began Prenatal Care | |

| Mother born before 1956 | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −2.21 | 0.003** | −0.10** | 0.08** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 4.63** | −0.003** | 0.07** | −0.06** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −9.27** | 0.003** | −0.06** | 0.06** |

| Mother born 1956 or later | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −13.02** | 0.005** | −0.20** | 0.10** |

| Parents Have Equal Education | 9.30** | −0.003** | 0.12** | −0.06** |

| Mother Has Higher Education | −8.10** | 0.002** | −0.08** | 0.04** |

| Panel B: IV Estimates | ||||

| Birth Weight | Low Birth Weight | Prenatal Visits | Month Began Prenatal Care | |

| Mother born before 1956 | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | −15,043.66 | 2.72 | −87.83 | −13.99 |

| Parents Have Equal Education | −4,046.37 | 0.73 | −14.46 | −0.48 |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 3,188.69 | −0.58 | 12.42 | 0.46 |

| Mother born 1956 or later | ||||

| Mother Has Lower Education | 4,438.04 | −2.68 | 36.93 | −7.14 |

| Parents Have Equal Education | −1,843.47 | 1.11 | −20.19 | 3.72 |

| Mother Has Higher Education | 3,153.28 | −1.91 | 44.54 | −7.78 |

Notes: Coefficients are from OLS models predicting infant health with controls for mother’s education, age, race, father’s education, child sex, and county and year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are adjusted for county-level clustering.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Models predicting low birth weight are linear probability models. Sample is the same as that in Table 2, but limited to infants whose mothers were born before or after 1956.

Cell shading indicates coefficients differ for births to mothers born before and after 1956 (p<0.05) (Paternoster et al. 1998).

Notes: Coefficients are from IV models predicting infant health with controls for mother’s education, age, race, father’s education, child sex, year, and county fixed effects. Instruments are the same as those used in Table 4. Robust standard errors are adjusted for county-level clustering.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

Models predicting low birth weight are linear probability models. Sample is the same as that in Table 2, but limited to infants with information for the instrumental variables and whose mothers were born before or after 1956.

When estimating the relationship between infant health and educational homogamy, Table 6 Panel A suggests a stronger benefit for birth weight and prenatal visits in later maternal cohorts. For example, the birth weight benefit associated with having equally educated parents is approximately twice as high (9.3 vs. 4.6 grams) in later maternal cohorts. Consistent with hypothesis 2c, the coefficients for equally educated parents are significantly larger among births to later maternal cohorts when predicting birth weight and prenatal visits (p<0.01). In contrast, coefficients for maternal hypogamy do not differ significantly by maternal cohort. As predicted by hypothesis 2b, maternal hypogamy is negatively associated with infant health in early cohorts. However, this negative relationship also holds in later cohorts.

As women surpassed men in college entry rates, OLS results suggest that maternal educational hypergamy and homogamy became more strongly associated with infant health. In contrast, the relationship between infant health and maternal educational hypogamy remained similar among earlier and later maternal cohorts. IV results provide inconclusive results due to weak instruments when limiting the sample by maternal cohort. This suggests the IVs may influence parental educational similarity partly through differences by maternal cohort. Due to weak instrument concerns, I do not interpret the IV results in Table 6.

Sensitivity Analyses

Analyses limited to married and unmarried mothers are provided in Tables S5 and S6. Results among married mothers are similar to those from the main analyses, reflecting the high proportion of births to married mothers between 1969 and 1994. IV estimates among married mothers are consistent with but in some cases less precise than those including the full sample. Births to unmarried mothers provide a smaller sample size and results are discussed in the Appendix.

To assess robustness of the main analyses, I replicate the main OLS and IV analyses (strategy 1) when including state-specific time trends. Results (see Table S7) are similar to those in the main analyses and offer further evidence that parental homogamy increases infant health and prenatal care, while maternal hypergamy reduces those outcomes. In addition, I estimate the relationship between infant health measures and the absolute value of the difference in years of parental education. OLS results (Table S9) suggest that each additional year of difference between parents’ education is associated with a small decrease in the number of prenatal visits (−0.01, p<0.01) and a slightly later start to prenatal care (0.01, p<0.01). In IV models, each additional year of difference reduces birth weight by 82 grams, decreases the number of prenatal visits by one, and delays prenatal care by one month (p<0.05). This suggests infant health depends on both qualitative and quantitative differences in parental education.

In further support of this conclusion, Tables S11–S13 provide results of analyses using categorical education measures. Both OLS and IV results are consistent with birth weight benefits of homogamy and lower infant health with maternal hypergamy. Although educational categories are more important in understanding socioeconomic inequality and its persistence across generations (e.g., Mare 1980), these results suggest that differences in both categories and years of education have implications for processes within families.

Conclusion

Since the 1960s, educational assortative mating patterns in the U.S. have changed, with implications for inequality of childhood contexts (Schwartz 2013; Western et al. 2008; Burtless 1999). These trends may also alter prenatal contexts, yet we know relatively little about the effects of educational sorting on infant health. Family systems theory suggests that – beyond the absolute levels of parental education – the relative similarity of parental education may influence infant health through prenatal stress. This study uses NVSS birth data and both OLS and instrumental variable approaches to estimate the relationship between parental educational similarity and infant health.

Results suggest having equally educated parents speeds the start of prenatal care and increases birth weight and prenatal visits, while maternal hypergamy reduces those outcomes. OLS results suggest maternal hypogamy is associated with poorer infant health, but estimates are inconsistent or do not reach significance in IV models. Overall, results support family systems theory, which suggests that parental educational similarity is beneficial for infant health.

Infant health at birth depends on multiple factors, including but not limited to parental behaviors (Griffiths et al. 2007; Voldner et al. 2009; Rosenzweig and Schultz 1982). To put the findings in context, I compare standardized OLS coefficients from this study to those in another study examining determinants of birth weight in the U.S. Using 1967–1969 survey data, Rosenzweig and Schultz (1982) estimate the following effect sizes on birth weight in the U.S. (calculated by multiplying the authors’ OLS coefficients in their Table 2.3 Model 1 by std. dev. x/std. dev. y from Table 2.1): Maternal age at birth d = 0.035; Delay in prenatal care (months of pregnancy before seeing a doctor) d = −0.004; Maternal cigarettes smoked per day during pregnancy d = −0.154; and Family in a metropolitan area (SMSA) d = −0.017. In this study, the standardized OLS coefficient for parental educational homogamy predicting birth weight is d = 0.006. Standardized OLS coefficients are similar in size, but opposite sign, for hypergamy and hypogamy. Thus, estimates from this study are larger than Rosenzweig and Schultz’s effect size for delay in prenatal care, approximately 1/6 their effect size for maternal age, and approximately 1/3 their effect size for residence in a metropolitan area. Not surprisingly, the effect size of parental homogamy is much smaller than that of maternal smoking during pregnancy (1/26). These comparisons suggest the importance of parental educational similarity is relatively small but not trivial compared to other factors related to birth weight, with the exception of smoking.

However, the implications of educational sorting differ by maternal education and cohort. First, the benefits of homogamy are limited to mothers with higher education. For the most part, these benefits emerge among mothers with at least high school in OLS analyses and some college in IV analyses. Similarly, negative effects of hypergamy are also most apparent among mothers with at least some college.

Second, OLS results differ by maternal cohort, suggesting that the relationship between certain patterns of educational sorting and infant health increased over time. Specifically, the infant health benefit of having equally educated parents was higher among later maternal cohorts, when women’s college entry and graduation rates reached and surpassed men’s (Buchmann and DiPrete 2013; Bailey and Dynarski 2011). The negative relationship between maternal hypergamy and infant health also increased in later maternal cohorts. This suggests declining rates of maternal hypergamy (Schwartz and Han 2014) may benefit infant health. In contrast, the relationship between infant health and maternal hypogamy did not differ by maternal cohort. As women’s advantage in college graduation rate grows, the proportion of infants born to homogamous or hypogamous parents may increase (Schwartz and Mare 2005). Results by maternal cohort suggest that the benefit of parental educational homogamy for infant health may increase over time, while the implications of maternal hypogamy may remain flat.

These potential implications should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, this study examines births from 1969 to 1994. These dates allow comparison of the relationship between assortative mating and infant health before and after women’s educational attainment surpassed men’s, but future research should investigate effects of educational sorting on infant health in more recent cohorts. Second, this study uses mean levels of spousal educational and employment similarity in a mother’s birth year and state of residence to instrument the educational similarity of parents and father’s education. As in any IV analysis, there is concern that the instruments may not be exogenous. This study uses one approach to address endogeneity of both father’s education and parental educational similarity, but research using a natural experiment that shifted parental sorting would provide additional information. Third, the education of both parents is reported by the mother. For unmarried or divorced women, father’s education could therefore be reported with more error than others. Separate results by marital status find consistent results among married mothers, particularly using OLS regressions. The relatively small sample size of births to unmarried mothers prevent strong conclusions. Further research should examine effects of assortative mating among unmarried mothers. Finally, this study focuses on health at birth. It cannot address whether parental educational similarity has effects on child health later in life.

Despite these limitations, this study advances knowledge about the potential consequences of changing educational sorting patterns and provides a novel estimate of their relationship with infant health. In support of family systems theory, results suggest that the relative similarity of parental education may have consequences for infant health beyond the absolute levels of parental education. These implications of parental educational similarity may contribute to racial inequality at birth. Gender differences in educational attainment are larger among African Americans than Whites (McDaniel et al. 2011), reducing the likelihood of homogamy for African American women. At the same time, low birth weight is more common among African Americans than Whites (13.7% vs. 8.2%, Kaiser Family Foundation 2016). Potential explanations for this birth weight gap include racial inequality in prenatal care, maternal health, infections, and stress, but questions remain because racial gaps in infant health are larger among mothers with higher education (Braveman 2012). Results of this study suggest that racial differences in parental educational sorting could help explain inequality of infant health. For example, the benefits of educational homogamy are limited to mothers with more education, but homogamy may be unlikely for highly educated African American women. Future research should examine racial differences in educational homogamy and their potential implications for infant health.

Furthermore, the consequences for infant health offer a potential mechanism for the relationship between educational sorting and intergenerational inequality. While existing research provides evidence that educational sorting can strengthen the intergenerational transmission of educational inequality (Fernandez and Rogerson 2001), results of this study suggest the intergenerational importance of such sorting may be broader. In fact, results suggest parental educational sorting may help transmit inequality between generations even before birth, through infant health. Evidence of a strengthening relationship between educational sorting and infant health by maternal cohort raises potential concern for inequality of infant health in future years. As women’s advantage in college entry and graduation grows, the intergenerational consequences of assortative mating patterns may also increase. Further research should examine child outcomes beyond infant health to determine in which ways assortative mating could increase or reproduce inequality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a University of Kansas general research fund grant. I am grateful for helpful feedback from Margot Jackson, Christine Schwartz, and anonymous reviewers.

About the Author

Emily Rauscher is an Assistant Professor in the Sociology Department at Brown University. Her research seeks to understand intergenerational inequality with a focus on education and health. She uses causal inference techniques to investigate these areas and to identify policies that could increase equality of opportunity. Other recent research has appeared in the American Journal of Sociology, Social Forces, and Demography.

Footnotes

The absolute level of parental education has implications for factors that could influence prenatal stress and infant health, such as labor force participation, marital satisfaction, and likelihood of divorce (e.g., Heaton 2002; Mirecki et al. 2013). However, these relationships changed over time, as more women entered the labor force and the association between education and divorce reversed (e.g., U.S. Department of Labor 2012; Harkonen and Dronkers 2006). In the 1940s those with more education were better able to afford a divorce, but as divorce became more common this relationship gradually reversed and divorce became more common among those with less education (Harkonen and Dronkers 2006). Because the likelihood of divorce by education was relatively equal in mid-20th century, this period provides lower heterogeneity by absolute education level.

In 1969, there are only 99,596 births with complete parental education. I include all of those births. 29% of records lack information for either maternal or paternal education. The missing rate varies by year, but generally trends downward over time as birth certificates became more standardized (Brumberg et al. 2012). Controlling for year helps address this change. The proportion missing is lower for maternal than paternal education (17% versus 29%), which suggests missing paternal education drives much of the missing rate. Therefore, the sample with complete parental education is likely more generalizable to births to parents in a stable relationship.

References

- Abuya Benta A., Ciera James, and Kimani-Murage Elizabeth. 2012. “Effect of Mother’s Education on Child’s Nutritional Status in the Slums of Nairobi.” BMC Pediatrics 12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Martha J. and Dynarski Susan M.. 2011. “Inequality in Postsecondary Education.” Pp. 117–131 in Duncan GJ and Murnane RJ (eds.), Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beck Audrey and Gonzalez-Sancho Carlos. 2009. “Educational Assortative Mating and Children’s School Readiness.” Center for Research on Child Wellbeing Working Paper 2009–05-FF. Retrieved January 14, 2014 from http://crcw.princeton.edu/workingpapers/WP09-05-FF.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beijers Roseriet, Jansen Jarno, Riksen-Walraven Marianne, de Weerth Caroline. 2010. “Maternal Prenatal Anxiety and Stress Predict Infant Illnesses and Health Complaints.” Pediatrics 126(2):e401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Sandra E., Devereux Paul J., and Salvanes Kjell G.. 2007. “From the Cradle to the Labor Market? The Effect of Birth Weight on Adult Outcomes.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(1):409–439. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld Hans-Peter. 2009. “Educational Assortative Marriage in Comparative Perspective.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bonke Jens, and Esping-Andersen Gosta. 2011. “Family Investments in Children—Productivities, Preferences, and Parental Child Care.” European Sociological Review 27(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman Paula. 2008. “Racial Disparities at Birth: The Puzzle Persists.” Issues in Science and Technology 24(2):1–6. Retrieved July 31, 2018 from http://issues.org/24-2/p_braveman/. [Google Scholar]

- Breen Richard and Salazar Leire. 2011. “Educational Assortative Mating and Earnings Inequality in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 117(3):808–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg HL, Dozor D, and Golombek SG. 2012. “History of the Birth Certificate: From Inception to the Future of Electronic Data.” Journal of Perinatology 32:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtless Gary. 1999. “Effects of Growing Wage Disparities and Changing Family Composition on the U.S. Income Distribution.” European Economic Review 43(4–6):853–65. [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Lubotsky Darren, and Paxson Christina. 2002. “Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient.” American Economic Review 92(5): 1308–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Yuyu and Li Hongbin. 2009. “Mother’s Education and Child Health: Is There a Nurturing Effect?” Journal of Health Economics 28: 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Susan H. 1982. “Parental Education and Child Health: Intracountry Evidence.” Health Policy and Education 2(3–4):213–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley D, Strully KW, and Bennett NG. 2003. The Starting Gate: Birth Weight and Life Chances. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conley Dalton, Laidley Thomas, Belsky Daniel W., Fletcher Jason M., Boardman Jason D., and Domingue Benjamin W.. 2016. “Assortative Mating and Differential Fertility by Phenotype and Genotype across the 20th Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(24):6647–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Conway Karen and Deb Partha. 2005. “Is prenatal care really ineffective? Or, is the ‘devil’ in the distribution?” Journal of Health Economics 24(3): 489–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet and Moretti Enrico. 2003. “Mother’s Education and the Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital: Evidence from College Openings.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4):1495–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Dancause Kelsey N., Laplante David P., Oremus Carolina, Fraser Sarah, Brunet Alain, and King Suzanne. 2011. “Disaster-Related Prenatal Maternal Stress Influences Birth Outcomes: Project Ice Storm.” Early Human Development 87:813–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPrete Thomas A. and Buchmann Claudia. 2013. The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What It Means for American Schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue Sara M.A., Kleinman Ken P., Gillman Matthew W., and Oken Emily. 2010. “Trends in Birth Weight and Gestational Length Among Singleton Term Births in the United States 1990–2005.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 115(2 Pt 1):357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Ryan D. and Roff Jennifer. 2016. “What Mom and Dad’s Match Means for Junior: Marital Sorting and Child Outcomes.” Labour Economics 40: 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Eika Lasse, Mogstad Magne, and Zafar Basit. 2017. “Educational assortative mating and household income inequality.” Staff Report, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, No. 682. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr682.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Esteve Albert, García-Román Joan, and Permanyer Iñaki. 2012. “The Gender-Gap Reversal in Education and Its Effect on Union Formation: The End of Hypergamy?” Population and Development Review 38(3):535–46. [Google Scholar]

- Evans William N. and Diana S. Lien. 2005. The benefits of prenatal care: evidence from the PAT bus strike. Journal of Econometrics 125(1–2): 207–239. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Raquel and Rogerson Richard. 2001. “Sorting and Long-Run Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116:1305–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher Jason. 2009. “All in the Family: Mental Health Spillover Effects between Working Spouses.” B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 9(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F. 2005. “Banking on Families: How Families Generate and Distribute Social Capital.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67:809–821. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel Irwin, Glei Dana, and McLanahan Sara S.. 2002. “Assortative Mating among Unmarried Parents: Implications for Ability to Pay Child Support.” Journal of Population Economics 15(3):417–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gihleb Rania and Lifshitz Osnat. 2016. “Dynamic Effects of Educational Assortative Mating on Labor Supply.” IZA Discussion paper No. 9958. Retrieved January 12, 2017 from ftp.iza.org/dp9958.pdf.