Abstract

Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells have been described in liver and non-liver diseases, and they have been ascribed antimicrobial, immune regulatory, protective, and pathogenic roles. The goals of this review are to describe their biological properties, indicate their involvement in chronic liver disease, and encourage investigations that clarify their actions and therapeutic implications. English abstracts were identified in PubMed by multiple search terms, and bibliographies were developed. MAIT cells are activated by restricted non-peptides of limited diversity and by multiple inflammatory cytokines. Diverse pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and immune regulatory cytokines are released; infected cells are eliminated; and memory cells emerge. Circulating MAIT cells are hyper-activated, immune exhausted, dysfunctional, and depleted in chronic liver disease. This phenotype lacks disease-specificity, and it does not predict the biological effects. MAIT cells have presumed protective actions in chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and decompensated cirrhosis. They have pathogenic and pro-fibrotic actions in autoimmune hepatitis and mixed actions in primary biliary cholangitis. Local factors in the hepatic microenvironment (cytokines, bile acids, gut-derived bacterial antigens, and metabolic by-products) may modulate their response in individual diseases. Investigational manipulations of function are warranted to establish an association with disease severity and outcome. In conclusion, MAIT cells constitute a disease-nonspecific, immune response to chronic liver inflammation and infection. Their pathological role has been deduced from their deficiencies during active liver disease, and future investigations must clarify this role, link it to outcome, and explore therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Innate-like lymphocytes, Antimicrobial, Immune regulatory, Pathogenic, Mucosal-associated invariant T cell

Core Tip: Circulating mucosal-associated invariant T cells are depleted in chronic liver disease, and they have a disease-nonspecific, hyper-activated, immune exhausted, and dysfunctional phenotype. Antimicrobial, immune regulatory, pro-inflammatory, and anti-inflammatory actions are established biological functions of these innate-like lymphocytes, and each function has been invoked to understand the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis and cholestatic liver disease. Future investigations must establish their pathological role in each form of chronic liver disease, determine the factors that direct function in the hepatic microenvironment, associate deficient functionality with disease severity and outcome, and explore therapeutic manipulations.

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are a subset of lymphocytes that engage in innate and adaptive immune responses[1]. MAIT cells react rapidly to pathogens. They can be activated by cytokine stimulation in an antigen-independent manner, and they can eliminate infected or altered cells by releasing pro-apoptotic granzyme B and perforin[2-4]. These features of an innate immune response are complemented by features of an adaptive immune response[1,5]. MAIT cells express a semi-invariant T cell antigen receptor (TCR) that is specific for a limited, but enlarging, array of antigens[6-10]. Furthermore, they can rapidly develop as effector memory cells[11,12].

MAIT cells can recognize riboflavin metabolites or other non-peptide antigens. These antigens are presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-related protein, MR1, which is expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs)[13-16]. Antigen-dependent MAIT cell activation can result in chemokine-directed tissue infiltration and release of diverse pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines[11,12,15,17]. The complex functional phenotype of MAIT cells justifies their inclusion in the family of innate-like lymphocytes[1]. This family includes gamma delta cells (γδ cells)[18-20], natural killer T cells (NKT cells)[21-25], and innate-like B cells (B1 cells, marginal zone B cells, and regulatory B cells)[26-29].

MAIT cells can enhance the adaptive immune response to microbial antigens[2,3]. Bacteria and fungi engaged in riboflavin biosynthesis can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-apoptotic molecules that eliminate infected cells[13,14]. Furthermore, the engagement of highly selected microbial antigens with the semi-invariant TCR of the MAIT cells can generate a cytotoxic CD8+ T cell response[2,30]. MAIT cell activation has been ascribed a protective antimicrobial role in several bacterial (Salmonella typhimurim, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae)[2,3,31] and viral [dengue virus, influenza virus, and hepatitis C virus (HCV)] infections[32-34].

MAIT cells have now been assessed in chronic hepatitis B[35-39], chronic hepatitis C[40-44], chronic hepatitis D[45], alcoholic liver disease (ALD)[46-48], non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[49-51], autoimmune hepatitis[52,53], primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)[54,55], primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)[56,57], and decompensated cirrhosis[58]. The pathological role of MAIT cells in these diverse forms of chronic liver disease remains unclear. They may be disease-nonspecific perpetrators or facilitators of inflammatory activity[59-62]. MAIT cells may stimulate hepatic fibrosis[52,63] and protect against microbial infection in decompensated cirrhosis[58]. They may modulate the cellular immune response[17,64-66] or limit the immune stimulatory effects of bacterial antigens from the intestinal microbiome[46,67-70].

MAIT cells are emerging as pivotal mediators of chronic liver disease[61,62], and clarification of their pathological role may lead to improved management strategies[71]. The goals of this review are to describe the biological properties of MAIT cells, present evidence of their critical involvement in chronic liver disease, and identify investigational opportunities to clarify their disease-associated roles and therapeutic implications.

METHODOLOGY

English abstracts were identified in PubMed using the primary search words, “MAIT cells”, “MAIT cells and chronic liver disease”, “MAIT cells and chronic viral hepatitis”, MAIT cells and chronic alcoholic liver disease”, “MAIT cells and fatty liver disease”, and “MAIT cells and autoimmune liver disease”. Abstracts judged pertinent to the review were identified; key aspects were recorded; and full-length articles were selected from relevant abstracts. A secondary bibliography was developed from the references cited in the selected full-length articles, and additional PubMed searches were performed to expand the concepts developed in these articles. The discovery process was repeated, and a tertiary bibliography was developed after reviewing selected articles from the secondary bibliography. Eight hundred and fifty-three abstracts and 134 full length articles were reviewed through November 2020.

CANONICAL MAIT CELLS

Defining features

MAIT cells are defined by a semi-variant α-chain within the TCR that is encoded in humans as Vα7.2-Jα33 by the TRAV1-2/TRAJ33 gene[3,7,72,73] (Table 1). The TCR α-chain associates with a constrained number of TCR β-chains. Vβ6 and Vβ20[61,73] are the principal β-chains associated with the TCR of MAIT cells, and they are encoded by the TRBV6 and TRBV20-1 genes in humans[6,8,74] (Figure 1). Together, the α- and β-chains form a TCR that can accommodate a limited number of chemical structures[8,10]. Human MAIT cell TCRs have hypervariable complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) in the TCRα-[75] and TCRβ-[8] chains that have restricted lengths. CDR3β of the TCR Vβ chain is stable between individuals, has a length of 11-14 amino acids, and accommodates 80% of the TCRβ repertoire of MAIT cell antigens[8].

Table 1.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cell characteristics and clinical implications

|

Feature

|

Characteristics

|

Clinical implications

|

| Semi-invariant TCR | Semi-invariant α-chain in the TCR[3,7,72]; Canonical Vα7.2-Jα33 α-chain[3,7]; TRAV1-2/TRAJ33 encodes Vα7.2-Jα33[3]; Vβ6 and Vβ20 most common β-chains[61]; TRBV6, TRBV20-1 encode Vβ6, Vβ20[8,74]; Restricted length of CDRs[8,75]; CDR3β key to antigen recognition[10] | Limited number of antigens recognized[8,10]; Antigen diversity still possible[10] |

| MR1-restricted antigens | Class 1b antigen-presenting molecule[2,7]; Expressed on surface of APC[3] | MR1 limits antigens presented by APCs[10,114] |

| CD161 | High surface expression[77-79] | Shared phenotypic marker with other T cells[78] |

| Cytokine receptors | IL-7, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23 receptors[80] | Multiple cytokines can activate MAIT cells[80,81] |

| Chemokine receptors | CCR5, CCR6, CCR9, CXCR6[59,62,77,82] | Chemokine-directed tissue migration[77] |

| Nuclear transcription factors | PLZF (also known as ZBTB16)[61,84,85]; RORγt[86]; T-bet[87,88,90,91]; ABCB1[11,62,83] | Control phenotype and functionality[84-88]; Direct development of memory phenotype[91]; Activate caspases and induce apoptosis[99]; Increase resistance to drugs, xenobiotics[11] |

| Cytokine production | IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-22[11,17,81,102]; IL-13, IL-4, IL-5 (anti-inflammatory)[64,66]; IL-10 (mainly in adipose tissue)[106] | Pro-inflammatory and antiviral effects[17,81,102]; Anti-inflammatory effects[66,106]; Cross regulation of immune responses[64,65] |

| Effector phenotype | Granzyme B[4,107,108]; Perforin[4,74,108] | Antimicrobial and pro-apoptotic actions[4]; Eliminates infected or altered cells[4,107,108] |

| Subsets | Mostly CD8αα cells in liver and blood[101] | More IFN-γ and TNF-α than CD8αβ subset[101] |

ABCB1: Multidrug resistance protein 1; APCs: Antigen presenting cells; CDRs: Complementarity-determining regions; IL: Interleukin; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T cell; MR1: Major histocompatibility complex I-related molecule; PLZF: Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger; T-bet: T-box transcription factor; TCR: T cells antigen receptor; t RORγt: Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

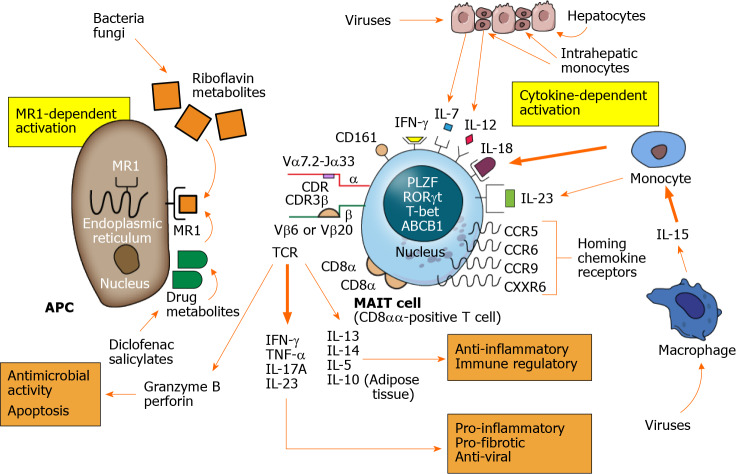

Figure 1.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cell activation and actions. Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are activated by MR1-dependent and cytokine-dependent mechanisms. The major histocompatibility complex class I-related protein, MR1, is expressed on the surface of the antigen presenting cell after stimulation. Riboflavin (vitamin B) metabolites synthesized by bacteria and fungi are presented by the MR1 molecule as are select drug metabolites. The T cell antigen receptor of the MAIT cell consists of a semi-invariant alpha (α) chain and restricted beta (β) chain with antigen selectivity influenced by short length complementarity-determining regions. MR1-dependent activation results in MAIT cell production of multiple cytokines as well as granzyme B and perforin. The cytokines can have pro-inflammatory, pro-fibrotic and antiviral effects (lower right panel) and anti-inflammatory and immune regulatory effects (lower right panel). The granzyme B and perforin can have antimicrobial activity and eliminate infected cells by apoptosis (lower left panel). Cytokine-dependent stimulation is activated by phagocytic macrophages and monocytes resident in the liver or circulation and by injured hepatocytes. Multiple cytokines can activate MAIT cells, especially interleukin 18, after virus infection. Chemokine receptors help direct the activated MAIT cells to the site of inflammation, and CXCR6 is the principal chemokine that directs MAIT cells to the liver. MAIT cells contain diverse nuclear transcription factors that influence phenotype and function, especially promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger, retinoic acid- related orphan receptor gamma t, and T-bet. The nucleus also contains the ABCB1 that affects resistance to gut-derived xenobiotics and certain drugs. The principal subset of activated MAIT cells consists of CD8αα-positive T cells. APC: Antigen presenting cell; TCR: T cell antigen receptor; CDR: Complementarity-determining region; IL: Interleukin; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T.

Antigen-presentation to MAIT cells is limited to the class 1b antigen-presenting molecule, MR1[2,7,76]. This restriction of antigen-activation is another defining aspect of MAIT cells (Table 1). The high surface expression of the C-type lectin, CD161[77-79], cytokine receptors for interleukin (IL)-7, IL-12, IL-18, and IL-23[62,77,80,81], and the chemokine receptors, CCR5, CCR6, CCR9, and CXCR6 are other phenotypic features[59,62,77,82] (Figure 1).

Key attributes

Most MAIT cells express the multidrug resistance protein 1 (also called the multidrug ABCB1 transporter)[11,62,83]. They also possess the nuclear receptor transcription factors, promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) (also known as ZBTB16)[61,84,85], retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt)[86], and T-box transcription factor (T-bet)[87-91] (Figure 1). The ATP binding cassette sub-family B member 1 gene (ABCB1) renders MAIT cells more resistant to cytotoxic drugs, chemotherapeutic agents, and gut-derived xenobiotics than other lymphocytes[11]. The ABCB1 transporter does not protect MAIT cells from immunosuppressive drugs such as tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid which are used in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis[83,92].

The diverse nuclear transcription factors, PLZF, RORγt, and T-bet, are involved in the lineage development of T helper 1 (Th1) cells[87,88,93], memory cells[91], Th17 cells[86], NKT cells[84], and MAIT cells[84,85] (Table 1). PLZP controls the phenotype and functionality of MAIT cells, and it directs the development of an effector memory phenotype[85,94-96]. These memory cells typically have the molecular signature, CD44hiCD95hiCD45RO+CD62Llo[11,12,15,94,97]. They can be activated without prior clonal expansion in response to IL-7[82,98].

PLZP also controls the fate of MAIT cells by activating intracellular caspases and rendering MAIT cells sensitive to apoptotic stimuli[99]. This sensitivity to apoptosis can be counterbalanced by the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP)[100]. The counterbalancing effects of PLZP and XIAP may account in part for the variable numbers of MAIT cells detected in the circulation and tissue sites during active inflammation[99].

Activated MAIT cells rapidly secrete interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-17A, and IL-22[11,17,81,101,102]. These cytokines have pro-inflammatory and antiviral effects (Figure 1). Stimulation of human MAIT cells in culture for 7-10 d can induce the robust release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-13[64,66]. IL-4 and IL-5 are also released but to a lesser extent[65,66]. IL-4 and IL-13 can induce an immunosuppressive phenotype in macrophages[66,103-105], and their production in inflammatory liver disease may cross-regulate the pro-inflammatory type 1 immune response[64,65] (Table 1). Little or no IL-10 is produced by activated human MAIT cells in the circulation, but 14% of resident MAIT cells in human adipose tissue produce IL-10[17,106]. Activated MAIT cells also secrete granzyme B and perforin which can have an antimicrobial effect by eliminating infected or altered cells[4,107,108] (Figure 1).

MAIT cell subsets

Most MAIT cells in the liver and peripheral circulation are CD8+ T cells[61,109]. They can be further characterized by the expression of the cell surface glycoproteins CD8α and CD8β[110,111] (Table 1). CD8α can exist as a disulfide-linked homodimer (CD8αα) or as a heterodimer (CD8αβ) on the MAIT cell surface[111]. Most MAIT cells in humans are CD8αα-positive, and most CD8αα-positive T cells in humans are MAIT cells[101] (Figure 1). Other subsets account for less than 10% of the MAIT cell population[101], and they exist as CD8αβ-positive, CD8-CD4- double-negative, and CD4-positive MAIT cells[61,112].

The CD8αα-positive subset produces more IFN-γ and TNF-α than the CD8αβ subset, and it may be more active in inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases[101]. Expansion and maturation of the CD8αα-positive subset of MAIT cells occur after exiting the thymus. The CD8αα-positive MAIT cells are probably driven by antigens encountered in the periphery, including the intestinal microbiome[101,113].

NON-CANONICAL MAIT CELLS AND MAIT-LIKE CELLS

T cell populations other than the typical Vα7.2-Jα33 MAIT cells have a semi-invariant TCR, reactivity to non-peptide antigens presented by a restricted MHC class I-like molecule, and responses that have innate and adaptive immune features. These populations include MAIT cell variants[8,10,74,114], MR1-restricted non-MAIT cells (MR1T cells)[114], and invariant NKT (iNKT) cells[115-119].

MAIT cell variants

MAIT cell variants have semi-invariant TCR α-chains that are encoded by non-classical genes or paired with different TCR β-chains. MAIT cells can have TCR α-chains encoded as Vα7.2-Jα12 by the TRAV1-2/TRAJ12 gene or Vα7.2-Jα20 encoded by the TRAV1-2/TRAJ20 gene[8,73]. These MAIT cell variants have fundamental traits that are identical to the Vα7.2-Jα33 MAIT cell population. They are activated by riboflavin metabolites in a MR1-dependent manner and by cytokine production. They differ only in homing characteristics. The Vα7.2-Jα12 MAIT cells seem to predominate in solid tissues[8]. A MAIT cell variant that is TRAV1-2neg retains the fundamental properties of MAIT cells and warrants inclusion in this variant category[74].

MR1-restricted non-MAIT cells

MR1-restricted T cells (MR1T cells) lack the fundamental characteristics of MAIT cells[114]. MR1T cells have diverse TCRα and TCRβ chains, and they fail to respond to microbial vitamin B metabolites. They produce a wide range of cytokines, and they recognize monocyte-derived dendritic cells as APCs[114]. MR1T cells have specificity for cell-derived antigens that can polarize their function after antigen stimulation[114]. They may thereby influence adaptive immune responses and immune tolerance of self-antigens. MR1T cells represent 1:2500-1:5000 of circulating T cells in healthy individuals, and they can be activated by a wide array of antigens presented in an MR1-binding groove. This MR1-restricted binding groove is larger and less restrictive than the MR1 of MAIT cells[114].

iNKT cells

iNKT cells are similar to MAIT cells in that they have a semi-invariant TCR and react to non-peptide antigens presented by an MHC class I-like molecule[5,81,120]. They express the natural killer (NK) antigen, NK1.1, which is known as CD161 on MAIT cells, and they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-22[120-122]. iNKT cells differ from MAIT cells in that their TCR α-chain is encoded as Vα24-Jα18 in humans and paired mainly with the TCR β-chain, Vβ11[120,123]. The antigen-restricted molecule that activates iNKT cells is CD1d (cluster of differentiation 1d) rather than MR1, and the activating antigens are lipid-based, including glycosylceramides (primarily, α-galactosylceramide), glycosphingolipids, and phospholipids[120,124-127]. Furthermore, iNKT cells are rare in the peripheral circulation (0.01%-0.1%)[120,122,128] and liver (0.5%)[120,122,129]. Unlike circulating MAIT cells[17], iNKT cells in the peripheral circulation secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10[130], and participate in the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs)[23].

MAIT CELL DEMOGRAPHICS

Frequency

MAIT cells constitute 0.1%-10% of the circulating CD3+ T lymphocytes in healthy individuals[61,131], and they are a resident population in the intestine (2%-20%), lung (1%-10%), and liver (10%-40%)[11,61,81,132] (Table 2). Their predominance in the liver[11,43,82,133] and paucity in lymphoid tissue (< 1%)[11] suggest that they are positioned to react with microbial antigens in the portal circulation or metabolic by-products within the liver or biliary circulation[133].

Table 2.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cell demographics and clinical implications

|

Feature

|

Demographics

|

Clinical implications

|

| Frequency (based on percentage of CD3+ T cells) | Circulation, 0.1%-10%[11,61,81,131]; Intestine, 2%-20%[11,61,102,132]; Lung, 1%-10%[11,15,61,81]; Liver, 10%-40%[11,43,61,82,133]; Lymph nodes, < 1%[11,61] | Liver is most MAIT cell enriched tissue[61]; MAIT cells can react with microbial antigens and metabolites in portal circulation and in bile[133] |

| Hepatic distribution | Present in bile ducts, portal tracts, sinusoids[55,133]; Chemokine-directed migrations[77]; CCR6, CXCR6, integrin αEβ7 to bile ducts[77,133]; CXCR3, LFA-1, VLA-4 to sinusoids[77,133] | Nature of the liver disease may direct MAIT cell migration to key site of inflammation[77,133,134] |

| Age-related changes | Numbers in blood increase up to age 40 yr[135]; Numbers in blood decline after age 60 yr[135]; MAIT cell apoptosis increases with age[135]; Depletion nadir after age 80 yr[136]; Depletion may be faster in men than women[131]; Shift from CD8+ to CD4+ cells with aging[131,137]; May be less pro-inflammatory with aging[131] | Ethnic and environmental factors possible[135]; Uncertain effect on severity and outcome[136]; Consider in design of clinical investigations |

LFA-1: Lymphocyte function-associated-1 protein; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T cell; VLA-4: Very late antigen 4.

Intrahepatic distribution

MAIT cells are localized mainly in the intrahepatic bile ducts, portal tracts, and sinusoids, and the nature of the liver disease may affect their distribution[55,133] (Table 2). MAIT cells have the ability to migrate based on the expression of tissue-homing chemokine receptors and the location of transmembrane adhesion molecules (integrins)[77]. MAIT cells can be directed to the bile ducts by CCR6, CXCR6, and integrin αEβ7 or to the hepatic sinusoids by CXCR3 and the integrins, LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated 1 protein) and VLA-4 (very late antigen 4)[133,134].

Age-related changes

The number of circulating MAIT cells increases from birth to adulthood (ages, 20-40 years) in healthy individuals[135]. Maximum circulating levels are in the third and fourth decades[136] (Table 2). The number of circulating MAIT cells declines after the age of 60 years in association with a gradual increase in MAIT cell apoptosis[135]. It is ten-fold less than in young adulthood after the age of 80 years[136]. The annual decline in the circulating level has been estimated as 3.2% in men and 1.8% in women[131].

Gender differences in the frequency of MAIT cells [131,136] and age-related differences in the phenotype and function of MAIT cells have been described but not established[131,135-137] (Table 2). Advancing age has been associated with an increasing proportion of CD4+ MAIT cells and decreasing proportion of CD8+ MAIT cells in some[131,136,137], but not all[135], ethnic cohorts. The pattern of cytokine production by MAIT cells has also changed to a less inflammatory profile with advancing age in one Asian cohort[131] but not in another[135]. The inconsistent phenotypic and functional age-related alterations may reflect ethnic and environmental factors[135], and they have yet to be ascribed an impact on specific pathological states[136].

MAIT cells are absent in germ-free animals (unlike NKT cells)[7], and their numbers can be reconstituted by intestinal colonization with various microbial organisms[30]. Diverse antigenic encounters during aging may explain the increasing numbers of MAIT cells that are detected in individuals as they enter adulthood[131,135,136].

MAIT CELL ACTIVATION

MAIT cells are activated by MR1-dependent mechanisms that are antigen-mediated and by MR1-independent mechanisms that are mainly cytokine-mediated[71]. Superantigens produced by certain bacteria (mainly, Staphylococcus aureus) can also activate MAIT cells without involvement of MR1[138,139].

MR1-dependent activation

The MR1 molecule is sequestered in the endoplasmic reticulum within the APC[140], and it may be undetectable on the APC surface until antigen exposure[141-146] (Figure 1). The antigen binding groove of the MR1 molecule has two pockets, and it can only bind small molecules[13,147]. The development of murine MAIT cells in the thymus requires exposure to microbial riboflavin metabolites[113]. Most bacteria and fungi synthesize riboflavin and generate riboflavin metabolites that can bind to MR1 and activate MAIT cells[30,148].

The principal ligands of MR1 are riboflavin (vitamin B2)-based metabolites designated as ribityllumazines[13] (Table 3). These ligands are characterized by a ribityl tail that can dock with MR1[13,14,74,149]. They are derived from the biosynthetic pathway for riboflavin which is present in most bacteria and yeast[13] (Figure 1). Folic acid (vitamin B9) derivatives, including 6-formylpterin (6-FP), can also be captured by MR1[13], but they lack the ribityl component and are unrecognizable by MAIT cells[74,143]. The synthetic folate derivative, acetyl-6-formylpterin, inhibits MAIT cell function by competing with other bacterial products for MR1 ligation. Its therapeutic value in modulating MAIT cell activity warrants further investigation[143,150].

Table 3.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cell activation and clinical implications

|

MAIT cell activation

|

Features

|

Clinical implications

|

| MR1-dependent stimulation | Adaptive immune response[1,5]; Antigen-triggered MAIT cell activation[8,10,114]; MR1 undetectable before antigen exposure[140,144]; MR1 binds only small non-peptide molecules[147]; Riboflavin metabolites are main MR1 ligands[13]; Ribityllumazines are main riboflavin metabolites[13]; Bacterial and metabolic by-products can activate[9]; Drugs and drug metabolites can bind to MR1[153] | Antigens for presentation restricted[8,10]; Most microbes metabolize riboflavin[148]; Neo-antigens diversify MR1 repertoire[9]; Can develop effector memory cells[11]; Drugs can modulate MR1 signaling[153]; MR1 expression can be inhibited[155] |

| Modulation of MAIT cell response | Response biased by ligand and TCR β-chain[148]; Riboflavin metabolites differ among microbes[3]; CDR3β rearrangements alter antigen recognition[143]; IL-7 and non-microbial molecules can regulate[155] | Response differs among microbes[154]; TCR plasticity can affect response[143]; Local milieu modulates response[82,155] |

| Cytokine-dependent stimulation | Innate immune response[1,5]; Activates MAIT cells without TCR ligation[156]; Receptors for IL-7, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23, IFN-γ[81]; IL-18 is main MAIT cell activator[157,158]; IL-18 usually with other mediators[82,157,158]; IL-7, IL-18 produced by hepatocytes[81,158]; IL-1β, IL-18, IL-23 produced by monocytes[81,158]; IL-15 acts on MAIT cells directly and indirectly[158]; Bacteria elicit TLR8-induced cytokines[160] | Initiates rapid antimicrobial response[156]; Response affected by local mediators[81]; Effective against viral infections[32,33,159]; Anti-bacterial monocyte response[160] |

| Superantigen stimulation | Rapid powerful response to severe infection[138,163]; Bacterial exotoxins activate T cell populations[161]; Foregoes MR1 antigen activation[138,161]; Direct activation by binding to TCR Vβ[71,138,165]; Indirect activation by released IL-12, IL-18[71,138]; Generates robust release of cytokines[138] | MAIT cells are major responders[138]; May result in toxic shock[162]; Causes immune exhaustion[138,139,163]; May exacerbate autoimmune disease[168]; Induces pathogenic autoantibodies[166] |

CDR3β: Complementarity-determining region 3-beta; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; IL: Interleukin; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T; MR1: Major histocompatibility complex I-related molecule; TCR: T cell antigen receptor; TLR8: Toll-like receptor 8.

Antigen diversity: The antigenic repertoire that binds to MR1 and activates MAIT cells has expanded beyond the ribityllumazines. Transitory neo-antigens have been described that are generated by the interaction of 5-amino-6-d-ribitylaminouracil, an early intermediate in the bacterial synthesis of riboflavin[151], with the metabolic by-products, glyoxal and methylglyoxal[152] (Table 3). Chemically unstable pyrimidine intermediates, 5-(2-oxopropylideneamino)-6-d-ribitylaminouracil (5-OP-RU) and 5-(2-oxoethylideneamino)-6-d-ribitalaminouracil (5-OE-RU), are formed, and these lumazine precursors can activate MAIT cells[9]. The unstable 5-OP-RU and 5-OE-RU molecules have diverse bacterial origins, and they are trapped in the antigen binding groove of the MR1 molecule by a reversible covalent Schiff base[9].

The antigen-binding groove of the MR1 molecule can also accommodate the structurally distinct compounds associated with the metabolism of drugs[153] (Figure 1). Salicylates and diclofenac can generate small molecules that bind with MR1 and exert a stimulatory (salicylates) or inhibitory (diclofenac) effect (Table 3). The findings indicate that diverse ligands outside the riboflavin and folic acid metabolites can be recognized by MAIT cells. They support the prospect that additional antigens will be discovered that modulate MAIT cell function[10,74].

Modulation of MAIT cell response: The MAIT cell response reflects mainly ligand-specific MR1 dependencies and TCR β-chain biases for a particular antigen[148] (Table 3). Different microbial species may produce different riboflavin metabolites and generate a selective MAIT cell response[3] or trigger the memory of a previous microbial exposure[154]. Conformational changes within the CDR3β segment may alter TCR flexibility and modulate antigen recognition within individual MAIT cell populations[143].

MAIT cell activation may also be modulated by the cytokine milieu created by the cells at the site of inflammation (Table 3). IL-7 produced by hepatocytes during inflammation can up-regulate MAIT cell production of Th1 cytokines and IL-17A[82]. Factors that regulate the cell surface expression of MR1 could also influence MAIT cell activation[144]. The non-microbial ligand, 3-([2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-yl]formamido) propanoic acid, down-regulates cell surface expression of MR1 and prevents antigen recognition[155].

The generation of MAIT cell antigens from bacterial and host-derived metabolic by-products constitute a rapidly responsive mechanism by which to target particular microbial pathogens under prescribed circumstances[9].

Cytokine-dependent activation

MAIT cells can be activated directly by cytokine stimulation in the absence of TCR ligation[156] (Table 3). MAIT cells express cytokine receptors for IL-7, IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-γ, and they can express the receptor for IL-23 after activation[81] (Figure 1). Cytokine activation of MAIT cells is mainly dependent on IL-18 in association with other inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15, and the type 1 interferons)[32,33,82,157,158]. These inflammatory mediators are derived from different cell types at the site of inflammation, and they can modulate the MAIT cell reaction in different combinations[81].

Hepatic inflammation can release IL-7 and IL-18 from hepatocytes, and activated monocytes can produce IL-1β, IL-23, and IL-18 after stimulation with IL-15[81,158] (Figure 1). Combinations of IL-1β, IL-7, IL-12, and IL-23 can affect MAIT cell production of IFN-γ and IL-17A[11,81,82]. IL-15 can directly stimulate MAIT cell production of IFN-γ or indirectly induce MAIT activation by stimulating monocyte production of IL-18[81,158].

MAIT cell activation in viral infections (dengue virus, influenza virus, and HCV infections) is dependent on IL-18 production[32]. The antimicrobial protection afforded by MAIT cells against influenza infection is based on the anti-viral activity of IFN-γ. MAIT cells release IFN-γ after stimulation with IL-18 alone[159] or in synergy with IL-12[33,157,160]. Intrahepatic monocytes are activated to produce IL-12 and IL-18 after stimulation of Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8)[160]. The cytokine milieu at the site of inflammation is a key modulator of MAIT cell activity, and it can tailor or finely tune the MAIT cell response to the disease process.

Superantigen activation

Superantigens are bacterial exotoxins that activate large numbers of T cells without undergoing the conventional route of activation by antigen-presenting MHC class I or class II molecules[70,138,161-163]. The superantigens bind to the lateral surfaces of class II MHC molecules expressed on APCs[164] or to Vβ regions within the TCR of T lymphocytes[70,165]. The massive simultaneous activation of exposed T cells can generate a robust release of cytokines, precipitate a toxic shock syndrome, and result in immune cell exhaustion and anergy[162,166]. Staphlococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, gram negative bacteria, mycoplasma, and viruses are key producers of superantigens[163].

MAIT cells are major responders to microbial infection and superantigens[138] (Table 3). MAIT cells can be activated directly by binding superantigens to their TCR Vβ region[71,138,139,165]. They can also be activated indirectly by the release of IL-12 and IL-18 from superantigen-activated T cells[71,138]. MAIT cell activation may in turn induce T cell exhaustion and immunosuppression that prevent adequate control of infection[138].

The impact of MAIT cell activation by superantigens on the occurrence and course of chronic inflammatory or immune-mediated disease is unclear. By activating large numbers of T cells, bacterial superantigens may enhance the proliferation of autoreactive T cells as well as MAIT cells[167,168]. Superantigens may also facilitate production of pathogenic autoantibodies by previously primed B cells[166,169,170]. These consequences could exacerbate an autoimmune disease. Alternatively, superantigens could promote immunosuppression by T cell exhaustion and prevent or ameliorate immune-mediated disease[168]. The actual impact may reflect the timing and intensity of MAIT cell activation[168].

MAIT CELLS IN CHRONIC NON-HEPATIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

MAIT cells have been evaluated in diverse chronic non-hepatic inflammatory diseases[15], including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[171], rheumatoid arthritis[171,172], multiple sclerosis[120,173-176], inflammatory bowel disease[132,177,178], celiac disease[179], and infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[109,180]. The findings have commonly demonstrated reduced frequencies of circulating MAIT cells[171,176,178-180], increased numbers of MAIT cells infiltrating the involved tissue (synovium, central nervous system, and ileum)[132,171,173,176], and uncertainties about the pathological role of the infiltration[15,120,181,182]. Furthermore, the studies have been complicated by disparities in the methodology to detect MAIT cells[12,73,183,184] and difficulties in separating treatment-associated from disease-related findings[15,177,185].

MAIT cell depletion in the circulation has been attributed to tissue migration during inflammation[132,176], apoptosis[99], activation-induced cell death (AICD)[109], exhaustion[186], and concurrent therapy with glucocorticoids[15,177,185]. MAIT cell determinations based on cell surface expression of CD161 have been faulted since chronic inflammation can down-regulate CD161 expression[12,73], and the preferred assay for MAIT cell recognition based on antigen-loaded MR1 tetramers has been used inconsistently[12,73,184,187]. The clinical investigations of MAIT cells in chronic non-hepatic inflammatory diseases provide insights, justifications, comparisons, and caveats that can strengthen and extend the investigations of MAIT cells in chronic liver disease.

MAIT CELLS IN CHRONIC HEPATITIS

The investigations of MAIT cell involvement in chronic hepatitis have been broad, mainly descriptive, and generally consistent with findings demonstrated in other chronic inflammatory diseases. They have positioned MAIT cells at the interface of inflammation and tissue injury, and they have confirmed their lack of disease-specificity. They have also expanded their possible roles as pathogenic, protective, and immune regulatory agents. Furthermore, they have indicated that in some liver diseases MAIT cells have contradictory effects.

MAIT cells may represent a primary, albeit defective, host-directed anti-viral response in chronic viral hepatitis[32,43,45,188]. They may constitute a hyperactive, immune exhausted, and depleted antibacterial defense in alcoholic hepatitis[46,47]. They may be a source of regulatory cytokines that reduce liver injury in NAFLD[51], and they may promote pro-inflammatory responses that enhance tissue injury and hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis[52,53]. The MAIT cell investigations in chronic hepatitis provide foundational knowledge that should incentivize further studies and impact on future management strategies.

MAIT cells and chronic viral hepatitis

The number of MAIT cells has been assessed in the blood and liver of patients with chronic hepatitis B[35-39] and chronic hepatitis C[40-44], and the functionality of circulating MAIT cells has been determined in both patient populations[36,39-42].

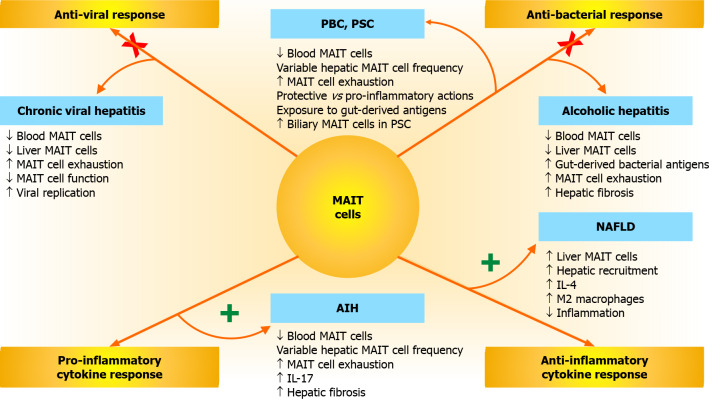

Reduced frequency of circulating MAIT cells: Five of six studies that have evaluated the frequency of circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B have found reduced numbers compared to healthy individuals[35-39,45] (Figure 2). In one of these studies, patients with concurrent infection with hepatitis delta virus had more severe depletion than patients with mono-infection[45] (Table 4). Similar findings of a reduced number of circulating MAIT cells relative to other T cells have been reported in 6 studies that have evaluated this issue in patients with chronic hepatitis C[32,40-44].

Figure 2.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cell responses and associations with chronic liver disease. Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells have anti-viral, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and pro-inflammatory responses that can affect the occurrence, severity, and outcome of diverse chronic liver diseases, including chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Impairments in the anti-viral and anti-bacterial responses of MAIT cells (indicated by an “X” across each activation pathway) may promote chronic viral hepatitis, PBC, PSC, and alcoholic hepatitis. Hyperactivity of the anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokine responses of MAIT cells (indicated by a “+” next to each activation pathway) may affect NAFLD and AIH. Increased release of interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-17 may contribute to the modulation of these responses. MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; IL: Interleukin.

Table 4.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in chronic hepatitis and clinical implications

|

Liver disease

|

MAIT cell features

|

Clinical implications

|

| Chronic hepatitis B | Reduced frequency circulating MAIT cells[37,38]; Depletion increased by delta infection[45]; Depleted intrahepatic MAIT cells[38,39,45]; Less granzyme B, IFN-γ, IFN-α release[36,188]; Conjugated bilirubin linked to dysfunction[39]; Increased PD-1 and CTLA-4 on MAIT cells[36]; Exhaustion correlates with HBV DNA level[36] | Chronic activation and exhaustion[36,39]; Less antiviral action[36,39,188]; Increased MAIT cell death[99]; Presumed defective protective role[36] |

| Chronic hepatitis C | Reduced frequency circulating MAIT cells[41,42]; Depleted intrahepatic MAIT cell[43]; Increased histologic indices reflect depletion[43]; Less TCR-activation and IFN-γ production[40,43]; Increased PD-1 and CTLA-4 on MAIT cells[41] | Hyper-activation and exhaustion[40,41,43]; Increased MAIT cell death[43,61,99]; Antiviral therapy not restorative[40,42,43]; Presumed defective protective role[43] |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | Reduced frequency in blood and liver[46,47,133]; Decreased granzyme B and IL-17 production[46]; Circulating bacterial products[46,47]; Increased percentage PD-1+ MAIT cells[47]; Abundant circulating stimulatory cytokines[47]; Myofibroblasts stimulated and pro-fibrotic[63] | Hyper-activation and dysfunctional[46,47]; Immune exhaustion[46,47]; Impaired intestinal mucosal barrier[46,47]; Increased MAIT cell death[47]; Diminished anti-bacterial function[133]; Presumed defective protective role[46,47] |

| NAFLD | Circulating MAIT cell frequency decreased[51]; Circulating cells express PD-1 and CD69[51]; Increased intrahepatic MAIT cell frequency[51]; Frequency correlates with NAFLD score[51]; Decreased IFN-γ and TNF-α production[51]; IL-4 induced polarization to M2 macrophages[51] | Activated and immune exhausted[51]; Increased hepatic migration[51]; Recruited by inflammatory activity[51]; Reduced functionality[51]; Promotes anti-inflammatory milieu[51]; Presumed defective protective role[51] |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Circulating MAIT cell frequency decreased[52,53]; Reduced granzyme B and IFN-γ secretion[52,53]; Variable intrahepatic frequency[52,53]; Increased IL-17A and HSC stimulation[52]; Increased expression of PD-1 and TIM-3[52] | Activated and immune exhausted[52,53]; Reduced functionality[52,53]; Pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu[52]; Progressive fibrosis[52]; Presumed active pathogenic role[52] |

CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HSC: Hepatic stellate cell; IFN-α: Interferon-alpha; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PD-1: Programmed cell death 1; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; TIM-3: T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Reduced frequency of intrahepatic MAIT cells: The number of intrahepatic MAIT cells was reduced in three of four studies in chronic hepatitis B[35,38,39,45] (Figure 2). Of two studies evaluating the number of intrahepatic MAIT cells in chronic hepatitis C, one disclosed reduced numbers[43] and another failed to associate the marked depletion in blood with an increased accumulation in liver[44] (Table 4). The lack of hepatic accumulation weakens the possibility that hepatic migration of MAIT cells explains the reduced peripheral count. The liver-homing chemokine, CXCR6[189], was also down-regulated on circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B[39].

Impaired functionality of MAIT cells: Circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C have impaired function (Figure 2). This impairment has been manifested mainly by reduced production of granzyme B[36,39,188], IFN-γ[36,39,188], and IFN-α[38] in patients with chronic hepatitis B and by reduced TCR-dependent antigen activation and IFN-γ production in patients with chronic hepatitis C[40,43] (Table 4). In patients with chronic hepatitis B, IFN-γ production has been reduced mainly in patients with serum conjugated bilirubin levels > 10-fold the upper limit of the normal range (ULN). This deficiency has been corrected by TCR-mediated stimulation[39].

In patients with chronic hepatitis C, receptor-mediated, but not cytokine-mediated, activation has been impaired[40,43]. Despite this deficiency, MAIT cells from the liver have had higher levels of activation and cytotoxicity than MAIT cells from the peripheral circulation (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the frequency of MAIT cells in the liver has correlated inversely with histological inflammation (r = -0.5437, P = 0.0006) and fibrosis (r = -0.5829, P = 0.0002)[43]. The findings suggest that deficiencies in the number and function of intrahepatic MAIT cells in chronic hepatitis C contribute to the pathological process or are consequences of it.

MAIT cell exhaustion: Circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B[36,39] and chronic hepatitis C[41] have expressed surface markers indicative of immune exhaustion, especially programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), CD39, T cell immunoglobulin mucin protein 3 (TIM-3), CD57, CD38, CD69, and HLA-DR (Table 4). The expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 and the percentage of MAIT cells expressing these markers have been higher in patients with chronic hepatitis B and viremia than in patients without viremia[36]. Furthermore, the expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 on MAIT cells has correlated positively with the level of viremia as assessed by plasma levels of hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid (HBV DNA)[36].

Similar findings have been described in patients with chronic hepatitis C (Table 4). Circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C have expressed higher levels of surface markers for immune exhaustion (HLA-DR, CD38, PD-1 TIM-3, and CTLA-4) and immunosenescence (CD57) than healthy controls[41]. Chronic immune stimulation and exhaustion could account for MAIT cell dysfunction in chronic viral hepatitis[39] (Figure 2).

Consequences of MAIT cell exhaustion and dysfunction: The consequences of MAIT cell exhaustion and dysfunction in chronic viral hepatitis may include depletion of circulating and intrahepatic MAIT cells and reduced suppression of virus replication[39] (Figure 2). An inverse correlation between the percentage of circulating MAIT cells and the expression of HLA-DR rather than viral load suggests that MAIT cell depletion is a consequence of chronic immune stimulation and exhaustion in chronic hepatitis B[36] (Table 4). MAIT cells have a pro-apoptotic propensity that may contribute to their peripheral depletion in the exhausted state and reduce their accumulation in the liver[43,99].

The positive association of exhausted MAIT cells with plasma HBV-DNA levels in chronic hepatitis B[36] attest to the potential value of MAIT cells as protective agents in chronic viral hepatitis[43]. This association is also supported by the inverse relationship between the number of intrahepatic MAIT cells and the severity of liver inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C[43]. The reduced number of intrahepatic MAIT cells in chronic viral hepatitis differs from experiences in non-hepatic chronic inflammatory diseases. In inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis, MAIT cell numbers are increased in the inflamed tissue consistent with active recruitment[132,171,173,176]. In chronic viral hepatitis, hepatic recruitment may be less or their intrahepatic destruction more robust[43,61].

Successful antiviral therapy with direct-acting agents does improve the number of intrahepatic MAIT cells[43], but it does not restore the number and function of circulating MAIT cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C[40,42,43] (Table 4). Immune exhaustion is a reversible state in most instances[190-192]. Failure to normalize the circulating MAIT cell population after virus eradication may reflect the low frequency of circulating MAIT cells in healthy individuals, the high density of other immune cells in the circulation, and the long lag time before full restoration[43]. Normalization of the serum conjugated bilirubin level and administration of the mitogen, IL-2, have expanded MAIT cells under experimental conditions in chronic hepatitis B[39]. This observation has not been investigated further.

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia: The frequencies of circulating and intrahepatic MAIT cells have correlated inversely with the serum conjugated and total bilirubin levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B[39]. Serum conjugated bilirubin levels > 10-fold ULN in chronic hepatitis B have been associated with a reduced number of circulating MAIT cells and a high rate of apoptosis. Surface markers for activation and exhaustion have been present; cytokine production has been variable; and MAIT cell proliferation and expansion have been impaired[39] (Table 4).

Concentrations of conjugated bilirubin equivalent to serum levels > 10-fold ULN have induced apoptosis in MAIT cells obtained from healthy donors, but other direct effects of conjugated bilirubin on MAIT cell function remain unclear[39]. Therapeutic strategies directed at reducing the serum concentration of conjugated bilirubin may be effective because of overall improvement in liver inflammation and function rather than elimination of a prime pathogenic factor[39].

MAIT cells and alcoholic hepatitis

The frequencies of circulating and intrahepatic MAIT cells have been decreased in most studies evaluating patients with alcoholic hepatitis[46-48,63,133] (Figure 2). Furthermore, the residual MAIT cells have been hyper-activated and dysfunctional in a manner similar to patients with chronic viral hepatitis[46,47] (Table 4). MAIT cell expression of transcription factors, RORγt, PLZF, T-bet, and eomesodermin (eomes), has been weak and associated with peripheral MAIT cell depletion and reduced secretion of granzyme B and IL-17[46]. Bacterial products, including endotoxin, D-lactate, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), have been present in the circulation. Furthermore, macrocyte/monocyte activation by bacterial LPS has been implied by the presence of the soluble receptor for LPS (sCD14)[46,47]. These findings have suggested that bacterial translocation from the intestine is a basis for chronic MAIT cell stimulation in alcoholic hepatitis.

Gut-derived MAIT cell stimulation: Chronic MAIT cell stimulation can impair the expression of nuclear transcription factors that are critical for maintaining antibacterial activity[107]. In alcoholic hepatitis, chronic exposure to gut-derived bacterial products may be a basis for impairing the antibacterial function of MAIT cells and creating a detrimental feedback loop[46] (Table 4). Moreover, fecal extracts from the stools of patients with alcohol-related liver disease have induced MAIT cell depletion in the absence of marked apoptosis or immune exhaustion[46] in a manner suggestive of AICD[46,193].

The presence of gut-derived bacterial markers in the peripheral circulation has also been demonstrated in another study of patients with alcoholic hepatitis[47]. An increased frequency of PD-1-positive MAIT cells has indicated immune exhaustion, and the frequency of exhausted MAIT cells has correlated inversely with the percentage of circulating MAIT cells[47]. Furthermore, there has been a shift in the MAIT cell phenotype from CD8+ to CD4+. The findings suggest that chronic bacterial stimulation contributes to MAIT cell hyper-activation, immune exhaustion, and depletion[47].

Cytokine-mediated MAIT cell stimulation: The hyper-activation of MAIT cells in alcoholic hepatitis could also be ascribed to increased circulating levels of cytokines associated with MAIT cell activation, including IL-7, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18, IL-23, IFN-γ, and TNF-α[47] (Table 4). Most of these cytokines have subsided after 6 mo of alcohol abstinence, but circulating levels of IL-18, IL-23, and IFN-γ have remained elevated for at least 12 mo[47]. Persistence of these cytokines could continue to stimulate and exhaust the MAIT cells. Future investigations must evaluate factors contributing to this sluggish improvement in MAIT cell numbers and function during alcohol abstinence. Persistent permeability of the intestinal mucosal barrier and protracted gut-derived bacterial translocation to the peripheral circulation are key aspects that require further evaluation.

MAIT cells and hepatic fibrosis: Activated human MAIT cells stimulate the proliferation of hepatic myofibroblasts in co-cultures[63] (Figure 2). The direct contact of activated MAIT cells with myofibroblasts obtained from patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis promotes their proliferation in an MR1-dependent manner (Table 4). The activated MAIT cells release TNF-α which can in turn increase the production of IL-6 and IL-8 by the hepatic myofibroblasts[63]. Under these circumstances, mitigation of MAIT cell activity could have a beneficial effect by reducing the release pro-inflammatory cytokines and the propensity for hepatic fibrosis.

Principal MAIT cell role in alcoholic hepatitis: The principal role of MAIT cells in alcoholic hepatitis appears to be protective. IL-17, which is a product of activated MAIT cells, is pivotal in initiating a cascade of antibacterial responses[194], and activated MAIT cells can eliminate MR1-positive infected cells[133]. MAIT cell dysfunction in alcoholic hepatitis may weaken these defense mechanisms and contribute to a high frequency of bacterial infection (49%)[195] and sepsis (13%)[196]. It may also account for the increased risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 2.33, P < 0.001) in severe alcoholic hepatitis[195].

The pathogenic association between MAIT cell dysfunction and adverse outcomes in alcoholic hepatitis remains conjectural, and it awaits studies that establish the protective value of enhanced MAIT cell function. The major therapeutic challenge of investigational MAIT cell manipulation is to promote the antibacterial properties of MAIT cells over their potential pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic effects.

MAIT cells and NAFLD

The frequency of circulating MAIT cells is also decreased in patients with NAFLD, and the frequency is inversely correlated with serum concentrations of gamma glutamyl transferase (γ-GGT) and triglycerides[51] (Table 4). Unlike patients with chronic viral hepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis, patients with NAFLD have an increased number of intrahepatic MAIT cells, and this number correlates directly with the NAFLD activity score[51] (Figure 2). Furthermore, the expression of the liver-homing chemokine, CXCR6[189], is increased as is the expression of CCR5 in the circulating MAIT cells[51]. CCR5 promotes MAIT cell migration to areas of hepatic steatosis by interacting with CCL5 (also known as RANTES)[197]. In patients with NAFLD, MAIT cells congregate around degenerating fat-laden hepatocytes in sinusoidal areas[51]. These observations suggest that MAIT cells are actively recruited from the circulation to the liver in response to inflammatory stimuli and hepatic steatosis.

As in chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis, the circulating MAIT cells are activated and immune exhausted. CD69 and PD-1 are expressed on the circulating MAIT cells, and the MAIT cells are functionally altered[51] (Table 4). The production of IFN-γ and TNF-α is decreased, and the release of IL-4 is increased (Figure 2). IL-4 has anti-inflammatory properties which can be manifested in NAFLD as a polarization of Kupffer cells into an M2 phenotype[198].

Macrophages can have a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype in response to IFN-γ[199] or an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype stimulated by IL-4[198,199]. A high percentage of monocytes/macrophages co-cultured with activated MAIT cells from patients with NAFLD display the M2 phenotype, and the ratio of M2:M1 macrophages is increased[51] (Figure 2). M2 macrophages can induce the apoptosis of M1 macrophages by a mechanism mediated by IL-10 produced by the M2 macrophages[198]. M2 polarization is a pathway that could reduce inflammatory activity in NAFLD, and it may be influenced by MAIT cells[51].

Free fatty acids increase the surface expression of MR1 in monocyte-derived macrophages[51], and they can also activate macrophages by signaling through TLR4 on the macrophage surface[200]. Free fatty acids could thereby increase macrophage activity and stimulate Kupffer cell expression of MR1. They could also increase TCR-mediated activation of MAIT cells and alter MAIT cell function by immune exhaustion. The net pathological consequence would depend on the balance between MAIT cell production of IL-4, the level of Kupffer cell polarization to the M2 phenotype, the pro-inflammatory effects of free fatty acids, and the extent of MAIT cell exhaustion. Clarification of the sequence and pivotal interactions of these pathological events could identify key targets for therapeutic intervention.

MAIT cells in obesity and diabetes: Obesity and diabetes are conditions that may accompany NAFLD, and MAIT cells can affect these co-morbidities. The frequency of circulating MAIT cells is decreased in obese patients and in obese and non-obese patients with type 2 diabetes[49] (Table 4). The decreased frequency is accompanied by increased activation (high expression of CD69) of the residual circulating MAIT cells and impaired production of IFN-γ and TNF-α[49]. The frequency of circulating MAIT cells that produce IL-17 is increased with obesity, and the expression of PD-1 is up-regulated, suggesting functional exhaustion[106]. Similar changes have been described in children with type 1 diabetes[50].

Adipose tissue from the omentum of obese patients has a higher frequency of MAIT cells than the peripheral blood (0.59% vs 0.06%) consistent with active recruitment, and the percentage of omental MAIT cells producing IL-17 is greater than the percentage in lean persons (26.9% vs 7.5%, P = 0.0009)[49]. IL-17 induces insulin resistance in adipocytes and hepatocytes[201,202], and the dysfunctional MAIT cells in adipose tissue and peripheral circulation may be a link between obesity and insulin resistance[106].

MAIT cells in human adipose tissue also produce IL-10[106] and IL-4[49]. MAIT cells from obese individuals produce less IL-10 and more IL-17 than MAIT cells from non-obese individuals, and the counterbalance between IL-10 and IL-17 production may modulate insulin resistance[106]. MAIT cells from obese individuals also express less of the anti-apoptotic molecule, B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)[49]. A shortened survival within the MAIT cell population may be another factor that alters the cytokine milieu.

In a murine model of obesity, MAIT cell frequency has been reduced in blood, epididymal adipose tissue, and ileum compared to lean mice[203]. The MAIT cells in the epididymal adipose tissue of obese mice have produced more IL-17A and TNF-α than in the lean mice, and the MAIT cells in the ileum have produced more IL-17A. The pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu has polarized the macrophages to an M1 phenotype in the epididymal adipose tissue of the obese mice, and it has been associated with an intestinal dysbiosis[203]. Treatment with the folic acid metabolite and TCR-blocking ligand, acetyl-6-formylpterin, decreased IL-17A production in the adipose tissue and ileum, prevented dysbiosis, and improved insulin sensitivity and glucose intolerance[203]. This mouse model of obesity has supported the clinical observations in obese individuals by implicating pro-inflammatory MAIT cells in adipose tissue as a potentially treatable factor contributing to insulin resistance and diabetes risk.

MAIT cell role in NAFLD, obesity, and diabetes: MAIT cells may have a protective role in patients with NAFLD by creating an anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu that polarizes M2 macrophages[51] (Figure 2). This protective role has been supported by animal studies that have demonstrated the development of severe hepatic steatosis[51] or exacerbated diabetes[50] in MAIT cell-deficient mice. MAIT cells may also have a pro-inflammatory effect that contributes to insulin resistance. This possibility has been supported by studies in obese patients[106], diabetic patients[50], and murine models of obesity[203] and diabetes[50]. The clinical and experimental studies in NAFLD, obesity, and diabetes underscore the diversity of MAIT cell activities and the need to better understand the factors that influence these activities within the involved tissue. This understanding is essential before considering targeted therapeutic manipulations.

MAIT cell deficiencies do improve as obesity and diabetes are successfully treated[49,50]. However, the relationship between correction of the MAIT cell deficiency and improvement of the metabolic disease remains conjectural. Bariatric surgery and subsequent weight loss have not normalized MAIT cell frequency or decreased IL-17 production[49]. Furthermore, insulin treatment of type 1 diabetes has not normalized the MAIT cell phenotype in children[50]. The possibility of a genetic predisposition for MAIT cell deficiency or a disease-acquired impairment that persists long-term has not been excluded. Future investigations of MAIT cells in NAFLD and its metabolic co-morbidities will need to define more fully the disease response as a function of MAIT cell activity.

MAIT cells and autoimmune hepatitis

The MAIT cell abnormalities described in untreated autoimmune hepatitis mirror those recognized in other forms of chronic hepatitis. Circulating MAIT cells are activated but depleted[52,53], and they are functionally altered in a manner consistent with immune exhaustion (reduced production of granzyme B and IFN-γ)[52,53] (Figure 2). The number of intrahepatic MAIT cells varies from low[52] to high[53], and the bases for this variation remain uncertain (Table 4). The key insight has been the recognition of MAIT cells as pivotal pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic agents.

The frequency of circulating, activated MAIT cells has been significantly higher (P = 0.009) in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and advanced hepatic fibrosis (fibrosis score, F3-F4) than in patients with little or no fibrosis (fibrosis score, F0-F2)[53]. Furthermore, blood levels of IL-17 have been increased in patients with autoimmune hepatitis[204]. IL-17A, which is a product of activated MAIT cells, is a recognized pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokine[11,101]. This production has been robust despite features of MAIT cell exhaustion in autoimmune hepatitis[52].

MAIT cells stimulate proliferation of hepatic stellate cells and increase the expression of genes that regulate the production of pro-fibrotic (collagen 1, lysyl oxidase, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1) and pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and CCL2) molecules[52]. These deleterious actions could help explain progressive hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. They have also been implicated in ALD[63].

MAIT cells have been associated mainly with detrimental pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic effects in autoimmune hepatitis[52,53] (Figure 2). Glucocorticoids have decreased the frequency of circulating MAIT cells by 23% in asthmatic patients[177], and they have altered MAIT cell populations in other autoimmune diseases[15,177,185]. Studies that explore the effects of glucocorticoids on MAIT cell numbers and function in patients with autoimmune hepatitis could clarify their pathogenic role and further validate or improve current corticosteroid-based management strategies[92].

MAIT CELLS IN CHRONIC CHOLESTATIC LIVER DISEASE AND DECOMPENSATED CIRRHOSIS

MAIT cells have been evaluated in patients with chronic cholestatic liver disease[54-57] and patients with decompensated cirrhosis[58] (Figure 2). The findings strengthen perceptions already developed in the various forms of chronic hepatitis. MAIT cells are common components of the host response to liver injury independent of etiology or clinical phenotype, and they may be protective, pathogenic, or both protective and pathogenic. The modifiable factors that direct these actions remain unclear and warrant further investigation.

MAIT cells and PBC

MAIT cells in PBC have abnormalities reminiscent of the findings in chronic hepatitis. Circulating MAIT cells are decreased in frequency compared to control subjects[54,55]; intrahepatic MAIT cells are reduced[54] or increased[55] in number; expression of the liver-homing chemokines, CXCR6 and CCR6, are up-regulated; and cytokine production is altered[54] (Table 5). Immune exhaustion has been invoked as a basis for aberrant MAIT cell function[54,55]. Apoptosis, attributable to AICD, has been proposed as a reason for MAIT cell depletion[54,55]. The key insight has been the recognition of MAIT cells as a pivotal immune regulatory population with complex and possibly contradictory actions.

Table 5.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in cholestatic liver disease and decompensated cirrhosis

|

Liver disease

|

MAIT cell features

|

Clinical implications

|

| PBC | Circulating MAIT cells decreased[54,55]; Intrahepatic MAIT cells variable[54,55]; Upregulated liver-homing CXCR6, CCR6[54]; Aberrant MAIT cell function[55]; Depletion associated with increased AP[55]; Low IFN-γ unable to impair HSC activation[55]; Preferential portal tract distribution[55]; Activation associated with increased ALT[54]; Cholic acid-induced hepatocyte IL-7[55]; IL-7-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines[55]; Limited expression of IL-7R and IL-18R[54] | Immune exhaustion[54,55]; Apoptosis-based depletion (AICD)[54,55]; Unable to prevent cholestasis[54,55]; Unable to inhibit hepatic fibrosis[55]; Defective barrier to gut-derived ligands[55]; Pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu[54,55]; UDCA improves but not restorative[54,55]; Presumed defective protective role[54,55]; Presumed active pathogenic role[54,55] |

| PSC | Circulating MAIT cell frequency reduced[57]; Intrahepatic MAIT cell frequency less[56]; CD69, CD56, PD-1, and CD39 expressed[57]; Impaired response to bacteria[57]; Abundant extrahepatic bile duct MAIT cells[57] | Activated and immune exhausted[57]; Depleted in circulation and liver tissue[56,57]; Less anti-bacterial protection[57]; Abundant migration to bile ducts[57]; Presumed defective protective role[57] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | Circulating MAIT cell frequency reduced[58]; High expression of activation markers[58]; MAIT cell frequency increased in ascites[58]; Increased cytokines from peritoneal cells[58]; Increased granzyme B from peritoneal cells[58]; Increased frequency in SBP ascites[58]; Homing chemokine CXCR3 on MAIT cells[58]; Abundant CXCL10 ligand in ascites[58] | Activated and recruited to ascites[58]; Anti-microbial protective response[58]; Protective role of uncertain efficacy[58] |

AICD: Activation-induced cell death; ALT: Serum alanine aminotransferase level; AP: Serum alkaline phosphatase level; HSC: Hepatic stellate cells; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; IL-7: Interleukin 7; IL-7R: Interleukin 7 receptor; IL-18R: Interleukin 18 receptor; MAIT: Mucosal-associated invariant T; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis; PD-1: Programmed cell death 1; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; SBP: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid.

MAIT cells may have a protective effect in PBC. The frequency of circulating MAIT cells has correlated negatively with the serum alkaline phosphatase level, suggesting that the loss of a protective MAIT cell function may permit worsening cholestasis[55] (Table 5). MAIT cell production of IL-17 is increased, and the production of IFN-γ is reduced[55]. IFN-γ is a cytokine that can impair hepatic stellate cell activation[205-207], and the reduced production of IFN-γ by MAIT cells could favor the pro-fibrotic actions of IL-17 in PBC[55,207]. MAIT cells preferentially infiltrate the portal tracts in PBC, and the expression of MR1 is up-regulated in hepatocytes, injured biliary epithelial cells, and inflammatory cells[55]. MR1-mediated stimulation of MAIT cells, possibly by bacterial ligands derived from the intestinal microbiome, could be a protective antimicrobial mechanism in PBC[55].

MAIT cells may also have a pro-inflammatory effect in PBC. The association of MAIT cell activation with elevated serum alanine aminotransferase levels suggests that the MAIT cell response could enhance inflammatory activity[54]. Furthermore, IL-7 stimulates the production of inflammatory cytokines and granzyme B by MAIT cells[55], and IL-7 is increased in the plasma and liver tissue of patients with PBC[55] (Table 5). The bile acid, cholic acid, up-regulates the expression of IL-7 in hepatocyte lines, and the intrahepatic MAIT cells in PBC may develop a pro-inflammatory phenotype[55]. Circulating MAIT cells have reduced expression of receptors for IL-7 (IL-7R) and IL-18 (IL-18R) in PBC, possibly because of immune exhaustion, and it is unclear how this observation might affect the intrahepatic MAIT cell response to IL-7[54].

Therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for at least 6 mo in 24 patients with PBC has increased the frequency and absolute number of circulating MAIT cells in those patients whose liver tests had improved[55]. The expression of the activation marker, CD25, has decreased; the percentage of apoptotic MAIT cells has diminished; and the frequency of MAIT cells producing IL-17A and granzyme B has decreased. Similar improvements in the frequency and absolute number of MAIT cells have also been demonstrated in 7 patients who had normalized liver enzymes after 6 mo of UDCA therapy[54]. In this series, the frequency of MAIT cells and the expression of IL-7R and IL-18R did not fully recover.

MAIT cells and PSC

Studies of MAIT cells in PSC have been limited, and the findings have been familiar (Figure 2). The frequency of circulating MAIT cells has been dramatically reduced in PSC, and the reduction has been similar to that encountered in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or PBC[57] (Table 5). The MAIT cell depletion has not been associated with particular clinical characteristics, and the MAIT cells have expressed markers of activation (CD69 and CD56) and immune exhaustion (PD-1 and CD39)[57]. The MAIT cell response to bacteria has been reduced, and the cytokine-dependent response has also been impaired[57]. MAIT cells have localized mainly to fibrotic areas in liver samples, and the overall intrahepatic population has been less than in donor or resected liver specimens[56].

The key finding in these studies has been the demonstration of abundant MAIT cells within the biliary tract by brushings obtained at endoscopic retrograde cholangiography[57] (Table 5). The proportion of MAIT cells in the biliary brush samples has been four-fold greater than in matched peripheral blood samples, and the MAIT cell accumulation at the site of inflammation has been consistent with a chronic protective response against intestinal pathogens in the biliary mucosa[57]. Patients with PSC have a high frequency of bacteria in bile cultures, especially with dominant strictures[208-210], manifest intestinal dysbiosis[211,212], and improve clinically after antibiotic therapy[213-216]. These observations have supported the concept that bacterial by-products from the intestinal microbiome stimulates immune-mediated damage to the biliary tree and liver and that MAIT cells have a protective, antimicrobial function in PSC[67,210].

MAIT cells and decompensated cirrhosis

The protective, anti-microbial role of MAIT cells in chronic liver disease has been supported by studies of MAIT cell frequency and function in patients with cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation (Table 5). The frequency of circulating MAIT cells has been reduced in these patients, and the MAIT cells have had an activated phenotype (high levels of HLA-DR, CD25, CD38, CD56)[58]. The frequency of MAIT cells has been increased in the ascites, and the highly activated peritoneal MAIT cells have produced higher levels of IFN-γ and granzyme B than the MAIT cells in matched blood samples[58].

MAIT cell frequency and total number have also been significantly increased in the ascites of patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis compared to patients with uninfected ascites[58] (Table 5). The peritoneal MAIT cells have lacked markers of tissue residency, and they have not been actively proliferating[58]. These features have suggested that the MAIT cells have migrated to the ascites from the circulation. The expression of the homing chemokine, CXCR3, by the peritoneal MAIT cells and the presence of high levels of CXCL10 in the ascites have also supported this conjecture.

MAIT cells in decompensated cirrhosis may have a protective function in uninfected ascites and a critical antimicrobial function in infected ascites. Studies that evaluate interventions to expand and strengthen the MAIT cell population in ascites might improve the control of bacterial infection in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Investigations in a murine model have already demonstrated that IL-23 combined with the MR1-ligand, 5-OP-RU, can protect against pulmonary infection with Legionella[217], and they encourage similar evaluations in models of advanced liver disease.

INCORPORATING MAIT CELLS INTO THE PATHOGENESIS OF CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

The incorporation of MAIT cells into the pathogenesis of chronic liver disease requires clarification of the role of MAIT cells in each type of chronic liver disease and demonstration that MAIT cell manipulation can affect disease severity and outcome.

Clarification of the disease-related role of MAIT cells

MAIT cells have been proposed as the new guardians of the liver[17], and patients with chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, PSC, and decompensated cirrhosis could be protected by the antimicrobial actions of fully functioning MAIT cells[2-4,30,218]. Similarly, patients with NAFLD might be protected by the anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13) generated by MAIT cells in the liver[51] and in adipose tissue[49,106]. Conversely, patients with autoimmune hepatitis could be disadvantaged by abundant MAIT cell production of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines[52,53], and patients with PBC could be either disadvantaged by MAIT cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines[55] or benefited by antibacterial actions against products from the intestinal microbiome[55].

The variability of the presumed consequences of MAIT cell depletion or dysfunction in the different liver diseases suggests that local factors in the hepatic microenvironment modulate the nature of the MAIT cell response. These factors may include local inflammatory cues (cytokine milieu)[219], bile acids (cholic acid)[55], gut-derived bacterial products (LSP, endotoxin, antigens)[46,47,69], and metabolic by-products (riboflavin metabolites, glyoxal, methylglyoxal)[9,13,14,151,152].

MAIT cells have different activation thresholds which can modulate their response to non-commensal antigens. Inflammatory signals derived from IL-12, IL-15, or IL-18 elicit robust antiviral (IFN-γ) and antibacterial (granzyme B) responses from MAIT cells[219], whereas direct TCR stimulation induces a brief, less robust release of IFN-γ and TNF-α and a less vigorous effector response[219]. The most potent effector function is elicited when both the inflammatory (cytokine-mediated) and TCR (antigen-mediated) signals are delivered concurrently to the MAIT cells[219]. Conditions at the site of inflammation could modify the activation thresholds for various MAIT cell functions and elicit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, or pro-inflammatory actions that are situation-specific[219,220]. Clarification of the conditions that drive the MAIT cell response toward a protective or pathogenic nature are needed to develop targeted, disease-appropriate, therapeutic interventions[220].

Manipulating MAIT cells to assess effects on disease severity and outcome

MAIT cell manipulations are necessary to establish the impact of MAIT cells on disease severity and outcome. Animal studies have demonstrated that genetically manipulated mice without MR-1 and MAIT cells exacerbate experimental NAFLD[51], whereas studies that demonstrate the effect of restoring the MAIT cell population are lacking. These studies would validate a critical pathogenic relationship that is necessary before considering therapeutic manipulations of MAIT cells in clinical trials.

MAIT cells can be up-regulated and down-regulated by several interventions that could help determine their pathogenic role in animal models. MAIT cells are immune exhausted in chronic liver disease, and they may be less responsive to MR1-dependent stimulation[82]. Cytokine-mediated stimulation may be the preferred method of restoring immune exhausted MAIT cells, and recombinant IL-7 has the potential to improve MAIT cell proliferation, cytokine production, effector (granzyme B) function, and MR1-mediated activation[82,107]. Furthermore, the administration of recombinant IL-7 to patients with chronic HIV infection has restored the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier[221]. Protection from gut-derived bacterial products by the administration of recombinant IL-7 might have a particular advantage in experimental models of alcoholic hepatitis[46,47], PBC[55], or PSC[57]. IL-15, IL-1β and IL-23 are other cytokines that can activate MAIT cells, but they have less potency than IL-7[82,158,222]. Cytokines of less potency or in various combinations may achieve the desired result without generating opposite or adverse effects.

Drugs and drug-like molecules can also modulate the function of MAIT cells as ligands that bind to MR-1[153]. Diclofenac metabolites can promote MAIT cell activity, and salicylates can inhibit this activity. Drugs have the promise of achieving the MAIT cell response appropriate for the individual disease as an agonist or antagonist of MAIT cell activity. Other therapeutic possibilities are ex vivo re-programming of MAIT cell function with select cytokines[82,107], vaccination with IL-23 in combination with 5-OP-RU[217], and re-programming and re-differentiating MAIT cells using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from MAIT cells[223]. Glucocorticoids reduce MAIT cell frequency in certain immune-mediated diseases[15,177,185], and they also may have a role in modulating MAIT cell activity.

Specific molecular interventions that could down-regulate MAIT cell activity are 3-([2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-yl]formamido) propanoic acid which can impair cell surface expression of MR1 and prevent antigen recognition[155] and acetyl-6-formylpterin, which can inhibit MAIT cell function by competing with other bacterial products for MR1 ligation[143,150]. These molecular interventions have the potential to clarify mechanisms of MR1 expression and function and possibly emerge as experimental agents by which to modulate MAIT cell activity.

MAIT cell manipulation will be an important experimental method to establish the protective and pathogenic importance of MAIT cells in chronic liver disease. This laboratory experience will be essential before considering MAIT cell intervention as a therapeutic strategy in patients.

CONCLUSION