Abstract

Background:

The traditional healthcare systems are being avidly looked into in the quest for effective remedies to tackle the menace of COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective:

This was a prospective randomized, controlled open-label, blinded end point (PROBE) study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a fixed ayurvedic regimen (FAR) as an add-on to conventional treatment/standard of care (SOC) in the management of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 infection.

Methodology:

A total of 68 patients were recruited who consumed either FAR + SOC (n = 35) or SOC only (n = 33) for 28 days. Primary outcomes assessed were mean time required for clinical recovery and proportion of patients showing clinical recovery between the groups. Secondary outcomes assessed included mean time required for testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, change in clinical status on World Health Organization (WHO) ordinal scale, number of days of hospitalization, change in disease progression and requirement of oxygen/intensive care unit admission/ventilator support/rescue medication, health status on WHO quality of life (QOL) BREF and safety on the basis of occurrence of adverse event/serious adverse event (AE/SAE) and changes in laboratory parameters.

Results:

Patients consuming FAR as an add-on SOC showed faster clinical recovery from the day of onset of symptoms by 51.34% (P < 0.05) as compared to SOC group. A higher proportion of patients taking FAR recovered within the first 2 weeks compared to those taking only SOC. It was observed that 5 times more patients recovered within 7 days in FAR group when compared to SOC (P < 0.05) group. An earlier clinical recovery was observed in clinical symptoms such as sore throat, cough, loss of taste and myalgia (P < 0.05). Improvement in postclinical symptoms such as appetite, digestion, stress and anxiety was also obs served to be better with the use of FAR. Requirement of rescue medications such as antipyretics, analgesics and antibiotics was also found to be reduced in the FAR group (P < 0.05). FAR showed a significant improvement in all the assessed domains of QOL. None of the AEs/SAE reported in the study were assessed to be related to the study drugs. Further, FAR did not produce any significant change in the laboratory safety parameters and was assessed to be safe.

Conclusion:

FAR could be an effective and safe add-on ayurvedic regimen to standard of care in the management of mild and moderate COVID-19 patients. CTRI number: CTRI/2020/09/027914.

KEYWORDS: Chyawanprash, COVID-19, Fixed Ayurvedic Regimen, Giloy, Kalmegh, Tulsi

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 has acquired a global pandemic status with increasing morbidity and mortality.[1] Currently, there is no accepted “standard of care (SOC)” available for its management in view of inadequate evidence on existing medicines and their limitations.[2] This is an opportune time when AYUSH concepts and interventions should be evaluated for developing better arsenals to prevent and treat the disease. With this objective, the Ministry of AYUSH has constituted an interdisciplinary AYUSH research and development task force for facilitating research of AYUSH interventions in COVID-19.[3] The current study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a fixed ayurvedic regimen (FAR) of AYUSH interventions – Giloy Ki Ghan Vati, Kalmegh tablets Tulsi tablets, and Chyawanprash as an add-on to conventional treatment in the management of mild and moderate COVID-19 infection. AYUSH interventions were selected on the basis of traditional wisdom, government recommendation and the abundant published data on their efficacy and safety. Study outcomes were analyzed basis changes in the mean time required for clinical recovery and proportion of patients showing clinical recovery between the groups. This study is one of the earliest clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety AYUSH interventions as add-on to conventional treatment/SOC in COVID-19 patients.

Ethical conduct of the study

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of KVTR Ayurved College and Hospital, Boradi, Maharashtra, to be conducted at COVID Care Center, Shingave, Shirpur, Dhule, Maharashtra and Dedicated COVID Hospital, Cottage Hospital, Shirpur, Dhule, Maharashtra. The study was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI) on September 19, 2020, vide CTRI number CTRI/2020/09/027914. Study personnel comprised a team of ayurvedic and modern medical doctors trained in good clinical practice for ethical conduction of the study. Study participants gave written informed consent before screening for their participation. An e-consent was also prepared on the lines of written informed consent form. Study data were captured on electronic data capture Electronic Data Capture (EDC) platform.

Study design

This was a prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded end point, two-arm, comparative clinical study conducted between September 2020 and January 2021. An independent investigator who was blinded to the group allotted did the assessment of clinical recovery in the study (blind end point assessment). The study data for all the study participants were captured in an electronic case record form (e-CRF) prepared as per 21 CFR compliant, EDC System. All the requirements of standards of safety, quality and confidentiality of the patients’ data were followed for data collection. First patient enrolment was on September 29, 2020. Last patients’ last follow-up visit was on January 14, 2021.

Study population

Patients were selected from COVID care center/dedicated COVID hospital and comprised male and female patients aged between 18 and 60 years with laboratory-confirmed (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]/rapid antigen test/any other test for as per the current guidelines) mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection of not more than 3 days (≤3 days) as per the MoHFW Government of India (GoI) guidelines [Table 1].[4,5] All the included patients expressed their voluntariness to participate in the study and were willing to follow COVID-19 prevention and containment-related guidelines issued from time to time by government/local health authorities throughout the study period.

Table 1.

US-CDC classification of COVID-19[4]

| Stage | Features |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | No specific clinical symptoms of COVID-19 disease |

| Mild to moderate | Mild clinical symptoms up to mild pneumonia |

| Severe | Dyspnea, hypoxia, or >50% lung involvement on imaging |

| Critical | Respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan system dysfunction |

[Ref: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ clinical-guidance-management-patients.html]. US-CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Patients suffering from severe COVID-19 infection in physician's opinion and fulfilling at least two of the following three criteria: (i) respiratory distress at room ambience (≥30 breaths/min), (ii) oxygen saturation ≤93% at rest on the peripheral digital arterial oximetry and requiring oxygen support for over 1 h to normalize and (iii) any of the known COVID-19 complications and emergency procedures which may require shift/admission in intensive care unit (ICU) (such as respiratory failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome and requirement of oxygen support for over 1 h or mechanical ventilation, septic shock, or severe nonrespiratory organ dysfunction or failure) were excluded.[6] Patients having difficulty in swallowing oral medications, chronic, severe, unstable, uncontrolled co-existent medical conditions (diabetes, hypertension, cardiac, liver, kidney, lung disorders, etc.), immune compromised status or any other medical or surgical condition that would require immediate medical or surgical intervention at the time of screening or may put the patient at increased risk during the study, AYUSH system-based contraindications, allergies or known to be allergic to intraperitoneal, pregnancy, lactation or any other condition, which in the opinion of the investigators, would render the patient unsuitable for participation in the study were also excluded.

Sample size

A sample size of 30 patients in each of the groups was calculated considering the predicted recovery rate and period by the physician and using statistical formula. A 5% level of significance (95% confidence interval) with a statistical power of 80% was considered for calculating sample size. Further, considering the novel COVID-19 pandemic condition and nonavailability of significant amount of epidemiological data to calculate appropriate sample size, a minimum statistically relevant sample size of 60 completers (30 each in the two groups) was considered for the present study.[4]

Study interventions and treatment

Patients in the FAR group were prescribed Giloy Ki Ghan Vati, Tulsi tablets and Kalmegh tablets – 1 tablet each, two times a day and 1 teaspoonful (approximately 10–12 g) of Chyawanprash twice daily as add-on to SOC prescribed by concerned health authorities for 28 days.

Giloy Ki Ghan Vati is a classical ayurvedic formulation containing goodness of renowned herb Giloy. Tulsi tablets and Kalmegh tablets are proprietary ayurvedic formulations, containing extracts of Tulsi leaves and Kalmegh roots, respectively, as actives. Chyawanprash is a classical ayurvedic formulation for immunity and overall health containing goodness of over 40 herbs and ingredients. Batch numbers TM00002 Mfd. 8/2020 of Tulsi tablets, BM 6898 Mfd. 09/2020 of Chyawanprash, DRDC/NJT/02 Mfd. 8/2020 of Kalmegh tablets and SB00142 Mfd. 08/2020 of Giloy Ki Ghan Vati, all manufactured by Dabur India Limited, Ghaziabad, were used in the current study.

Patients in SOC group served as control receiving conventional treatment comprising antibiotics/antiallergics/antipyretics/multivitamins as prescribed/advised by local health authorities for 28 days.

Primary outcomes

Mean time (in days) required for clinical recovery from COVID-19 from the day of first noticed symptoms to the day of clinical recovery and from day of randomization to the day of clinical recovery

Proportion of patients showing clinical recovery between the two groups.

Secondary outcomes

Mean time (days) required for testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 from the day of randomization and from the day of first noticed symptoms

Assessment of clinical recovery/postclinical recovery and Ayurvedic clinical assessment

Number of days of hospitalization

Change in disease progression and requirement of oxygen/ICU admission/ventilator support/rescue medication

Change in clinical status on World Health Organization (WHO) ordinal scale and health status on WHO quality of life WHOQOL-BREF

Global assessment of overall change

Percent mortality in the groups

Assessment of safety on the basis of adverse event/serious adverse event (AE/SAEs) and laboratory safety parameters.

METHODOLOGY

At screening visit, a written informed consent was obtained from patients for their participation in the study. Patients’ demographic data, medical history and physical and systemic examinations were done and vitals and SpO2 levels were recorded. Patients’ clinical status was assessed on the 8-point WHO ordinal scale.[7,8] Patients’ laboratory investigations i.e., hematology, blood sugar (Fasting), liver functions, lipid profile, renal functions, HIV status and urinalysis (routine and microscopic), were done. Chest X-ray and electrocardiogram (ECG) were done if advised by the investigator. For all fertile female patients, a urine pregnancy test was done. Patients fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria were recruited and randomized to either of the study groups as per a computer-generated randomization chart. Both the groups were advised to follow their normal/routine and diet which they were already following. At each visit, patients were enquired for occurrence of any AE/SAE during the period from their last visit. Any AE/SAE was recorded in the CRF. Any other tests such as serum ferritin, serum D-dimer and CRP, if advised by the health authorities, were done. Patients’ ayurvedic clinical assessment was done and their physical constitution (ayurvedic Dosha Prakriti) and QOL[9] were assessed.

During hospital stay, patients’ physical and systemic examinations, vitals and SpO2 levels were routinely checked. Patients’ ayurvedic clinical assessment and clinical status rating on ordinal scale were assessed. Patients were enquired for occurrence of any AE/SAE and their drug compliance was checked. Assessment of number of patients requiring oxygen, ICU admission and ventilator support, any other higher treatment, or rescue medication was done. Clinical recovery from COVID-19 symptoms was assessed basis criteria mention in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria for clinical recovery

| 1. Normal body temperature (≤36.6°C axilla or≤37.2°C oral) |

| 2. Absence of cough or mild cough (infrequent, short episodic, non-wheezy, relieved by minimal or no medication, not interfering with routine speech and not related to lying in bed, mild sore throat, or nasal congestion) |

| 3. Absence of breathlessness on routine daily self-care chore or respiratory rate less than 30 breaths per minute without supplemental oxygen |

| 4. Normalization of SpO2 by standard peripheral oximetry device (above 95%) |

| 5. Recovery should be sustained for at least 48 h under physician observation |

| 6. Absence of any other symptom/sign attributed to COVID-19 illness |

| 7. Assessed by physician blinded to treatment allocation |

| 8. All of the above criteria ought to be fulfilled |

Clinically recovered patients were discharged from the hospital as per hospital guidelines. The mean time (days) required for clinical recovery from the day of randomization and from the day of the first noticed symptom was recorded CRF. Patients’ COVID test was repeated at the time of discharge. If it was positive, then the test was to be repeated on day 28. If required, patients’ hematological and biochemical parameters or any other tests, if advised, were done and patients’ clinical status and ayurvedic assessment of postclinical recovery (appetite, digestion, sleep, anxiety, physical weakness, etc.) were also done. Number of days of hospital stay was noted in the CRF. Patients were enquired for the occurrence of any AE/SAE during the period from the last visit and their drug compliance was recoded. Discharged patients in both the groups were advised to continue with their respective treatments as advised by the investigators and the local health authorities till day 28 and follow the instructions given by the investigator/local health authorities such as practicing self-isolation, respiratory etiquettes, wearing masks and physical distancing. The discharged patients were followed up telephonically on day 14 to assess their clinical status and ayurvedic postclinical recovery (appetite, digestion, sleep, anxiety, physical weakness, etc.). Patients were also inquired for the occurrence of any AE/SAE during the period from the last visit and drug compliance.

On day 28 (end of study), patients were called at the study site for final follow-up visit. Their physical and systemic examinations and all clinical assessments were done, and QOL was assessed using the WHO QOL BREF instrument. Patients were enquired for the occurrence of any AE/SAE during the period from the last visit and drug compliance. Patients’ global assessment of safety and efficacy was evaluated by the investigator and patients themselves. Patients’ laboratory investigations were done. If required, chest X-ray and ECG can be done and serum ferritin, serum D-dimer and CRP can also be done. RT-PCR/rapid antigen test was repeated for patients who tested positive on discharge from hospital. If patients’ report was negative, it was recorded in CRF. In case any patient tested positive on day 28, he was instructed to take further treatment and follow guidelines as prescribed by the local health authorities.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

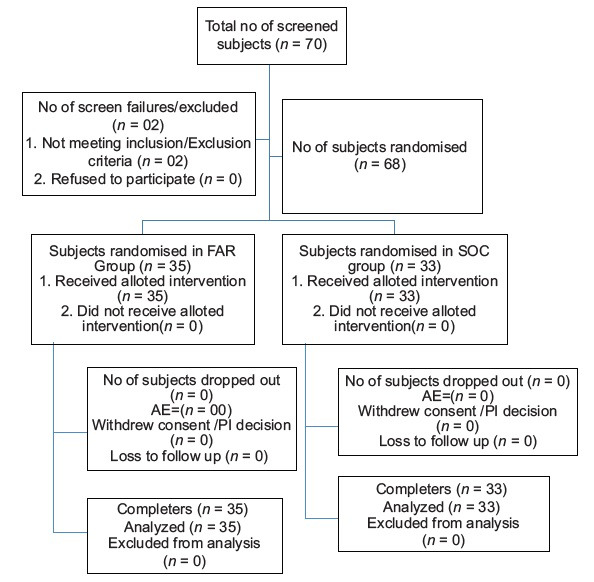

A total of 70 patients were screened, out of which there were two screen failures as these patients did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria and 68 patients were recruited in the study. Recruited patients were randomized into either of the study groups as per computer-generated randomized list, of which 35 patients were randomized in the FAR/add-on group and 33 patients in the SOC/control group. There were no drop-outs; all the recruited patients completed the study and were considered as completers or efficacy evaluable cases at the end of the study. The study flow is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Demographic details

Age- and sex-wise distribution of patients

The average age of the patients was 39.20 ± 11.68 years in the FAR group and 41.06 ± 12.12 years in the control group, showing no significant difference (P > 0.05). Of the 35 patients in FAR group, there were 19 (54.28%) males and 16 (45.72%) females. Of the 33 randomized in the control group, there were 24 (72.72%) males and 9 (27.27%) females. The average body weight and body mass index of the patients at baseline in the FAR and SOC groups was 59.71 ± 9.56 kg and 22.40 ± 2.93 kg/m2 and 62.24 ± 9.414 kg and 22.55 ± 3.238 kg/m2, showing no statistical difference (P > 0.05).

Assessment of Prakriti and Ayurvedic Clinical Parameters

Prakriti wise Analysis

Analysis of Prakriti[10,11,12,13] showed a predominance of Vata-Pitta Prakriti in FAR group. None subjects were of a single Doshic predominance. The SOC group showed a predominance of Pitta-Kapha Prakriti [Table 3]. Ayurvedic clinical assessment done at baseline basis Agni and Kostha, Dosha, Rogibala, Dushya etc[10,11,12,13] showed a predominance of - Vishamagni in FAR Group and Mandagni in SOC group. None of the subjects possessed Tikshnagni. Assessment of Kostha (bowel strength) showed a predominance of Madhyam Kostha in both study groups. Assessment of Rogibala (strength of the patient) showed predominance of Madhyam Bala in both study groups. Maximum subjects in both the groups had Vata predominant conditions (Vata/Vata-Pitta/Vata-Kapha). Subjects in both the study groups showed involvement of Dushya like Rasa, Rakta & Mamsa Dhatu. Assessment of Adhisthan and Strotas revealed maximum involvement of Pranavaha, Annavaha and Rasavaha Srotas (respiratory, digestive and circulatory systems) [Tables 4-8].

Table 3.

Prakriti wise Distribution of Subjects

| Type of Prakriti | No. of Subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR Group | SOC Group | |

| Vata | 0 | 1 (3.03%) |

| Pitta | 0 | 0 |

| Kapha | 0 | 1 (3.03%) |

| Vata-Pitta | 11 (31.42%) | 7 (21.21%) |

| Vata-Kapha | 5 (14.28%) | 5 (15.15%) |

| Pitta-Kapha | 3 (8.57%) | 9 (27.27%) |

| Pitta-Vata | 3 (8.57%) | 3 (9.09%) |

| Kapha-Pitta | 8 (22.85%) | 5 (15.15%) |

| Kapha-Vata | 4 (11.42%) | 2 (6.06%) |

| Sama | 1 (2.85%) | 0 |

| Total | 35 | 33 |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Table 4.

Assessment of agni

| Type of agni | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR group, n (%) | SOC group, n (%) | |

| Manda | 15 (42.85) | 19 |

| Tikshna | 0 | 0 |

| Vishama | 19 (54.28) | 14 (42.42) |

| Sama | 1 (2.85) | 0 |

| Total | 35 | 33 |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Table 8.

Assessment of adhishthan/srotas

| Adhishthan/srotas | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR group, n (%) | SOC group, n (%) | |

| Pranavaha | 35 (100) | 32 (96.96) |

| Annavaha | 31 (88.57) | 29 (87.87) |

| Udaka Vaha | 0 | 0 |

| Rasavaha | 7 (20) | 6 (18.18) |

| Raktavaha | 0 | 0 |

| Mansavaha | 2 (5.71) | 0 |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Table 5.

Assessment of kostha

| Type of koshtha | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR group, n (%) | SOC group, n (%) | |

| Mrudu | 4 (11.42) | 3 (9.09) |

| Madhyam | 17 (48.57) | 25 (75.75) |

| Krura | 14 (40) | 5 (15.15) |

| Total | 35 | 33 |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Table 6.

Assessment of doshic predominance

| Doshic predominance | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR group, n (%) | SOC group, n (%) | |

| Vata | ||

| Vata | 1 (2.85) | 5 (15.15) |

| Vata-Pitta | 1 (2.85) | 2 (6.06) |

| Vata-Kapha | 19 (54.28) | 16 (48.48) |

| Pitta | ||

| Pitta | 0 | 0 |

| Pitta-Vata | 0 | 0 |

| Pitta-Kapha | 0 | 1 (3.03) |

| Kapha | ||

| Kapha | 0 | 2 (6.06) |

| Kapha-Vata | 13 (37.14) | 5 (15.15) |

| Kapha-Pitta | 1 (2.85) | 1 (3.03) |

| Tridosha | ||

| Vata-Pitta-Kapha | 0 | 1 (3.03) |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Table 7.

Dushya involvement dhatu

| Dushya involvement | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| FAR group, n (%) | SOC group, n (%) | |

| Rasa | 35 (100) | 33 (100) |

| Rakta | 33 (94.28) | 33 (100) |

| Mansa | 4 (11.42) | 8 (24.24) |

| Meda | 0 | 0 |

| Asthi | 0 | 0 |

| Majja | 0 | 1 (3.03) |

| Shukra | 0 | 0 |

FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Assessment of primary outcomes

Comparative assessment of mean time (days) required for clinical recovery

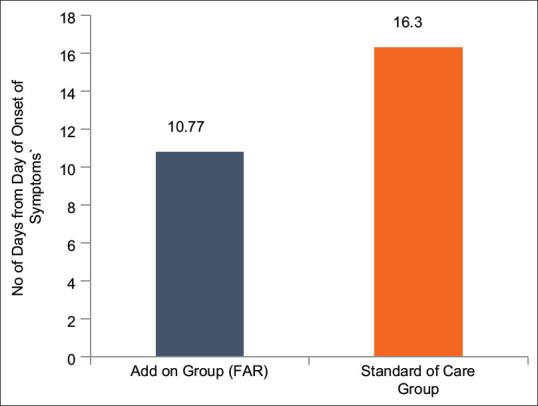

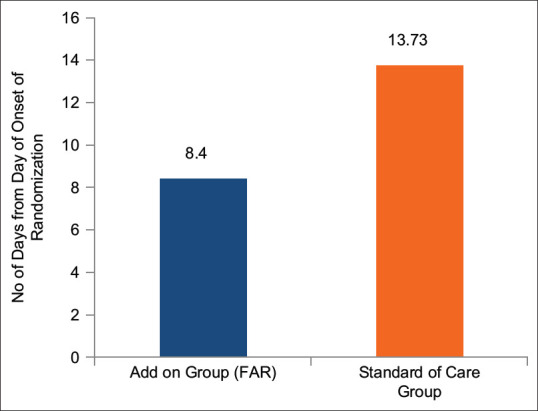

The average number of days required for clinical recovery from the day of onset of symptoms (1st day of appearance of symptoms) and from the day of randomization in the FAR and SOC groups was 10.77 ± 3.24 and 16.30 ± 5.93 and 8.40 ± 3.10 and 13.73 ± 5.66, respectively. The recovery in the FAR group was assessed to be 51.34% faster from the day of onset of symptoms and 63.45% faster from day of randomization in comparison to the control group [Table 9, Figures 2 and 3]. This difference between the groups was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001) and patients in the FAR group were assessed to have recovered faster and earlier as compared to those in the control group.

Table 9.

Assessment of days for clinical recovery

| Group | Mean time (days) required for clinical recovery from COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| From day of onset of symptoms | From day of randomization | |

| FAR group (n=35) | 10.77±3.24 | 8.40±3.10 |

| SOC group (n=33) | 16.30±5.93 | 13.73±5.66 |

| P value between the groups | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Percentage difference between the groups | 51.34* | 63.45* |

*Significant (P<0.05). FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care

Figure 2.

Time to Clinical Recovery (days) from Day of Onset of Symptoms

Figure 3.

Time to Clinical Recovery (days) from Day of Randomization

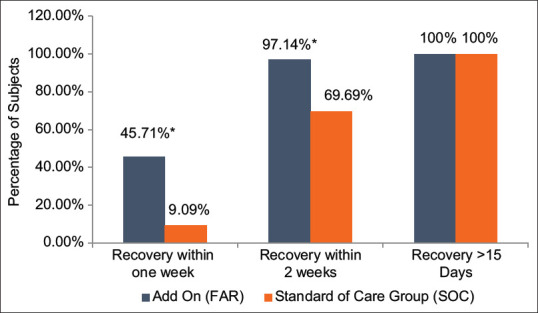

Comparative proportion of patients showing clinical recovery

A higher number of patients (45.71% and 97.14%) taking FAR showed clinical recovery within 1 and 2 weeks (7 and 14 days) from the day of randomization, while in the control group, this number was lesser (9.09% and 69.69%). Statistically, the proportion of patients showing recovery based on the number of days showed a significantly higher number of patients (P < 0.05) achieving earlier clinical recovery in the FAR group as compared to control group. It was observed that 5 times more patients showed clinical recovery in the 1st week in FAR group than control group. All patients recovered completely in both the groups at the end of the study, i.e., 28 days [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Comparative assessment of proportion of patients showing clinical recovery

Assessment of secondary outcomes

Comparative assessment of mean time (days) required for testing negative for SARS-CoV-2

Testing for RT-PCR was done as per the guidelines of the local health authorities for COVID-19. The average number of days required for testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 (on RT-PCR/rapid antigen test) assessed from the day of randomization was 14.74 ± 8.74 and 16.61 ± 10.19 in the FAR and control groups, respectively, while the same was 17.17 ± 8.77 and 19.15 ± 10.46 from the day of onset of symptoms, respectively, in the groups. Although the average number of days for testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 was lesser in FAR group than control group, statistically this difference between the groups was not significant.

Comparative assessment of duration of fever and other clinical symptoms

The common clinical symptoms recorded in the study groups were fever, sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, headache and generalized weakness. The average number of days required for recovery in clinical symptoms was found to be lesser in FAR group as compared to the control group. Patients in FAR group showed a significantly earlier (P < 0.05) recovery in symptoms such as sore throat, loss of taste, myalgia, anorexia, weakness and vertigo when compared to control [Table 10].

Table 10.

Assessment of number of days for clinical recovery from symptoms of COVID-19

| Symptoms | Incidence of symptom | Days for clinical recovery | P** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAR group (n=35) | Control group (n=33) | FAR group (n=35) | Control group (n=33) | ||

| Fever | 34 (97.14) | 32 (96.96) | 5.60±1.57 | 6.25±3.38 | >0.05 |

| Sore throat | 32 (91.42) | 30 (90.90) | 6.93±2.34 | 8.50±3.83 | <0.05* |

| Cough | 31 (88.57) | 32 (96.96) | 8.45±2.62 | 13.25±5.77 | <0.05 |

| Shortness of breath | 14 (40) | 8 (18.18) | 5.26±2.15 | 6.50±2.44 | >0.05 |

| Loss of taste | 26 (74.28) | 23 (69.69) | 5.73±1.80 | 6.91±2.90 | <0.05* |

| Loss of smell | 24 (68.57) | 14 (42.42) | 5.75±1.64 | 5.57±1.82 | >0.05 |

| Myalgia | 33 (94.28) | 30 (90.90) | 8.08±2.26 | 13.42±5.02 | <0.05* |

| Headache | 18 (51.42) | 14 (42.42) | 2.66±0.48 | 2.85±1.02 | >0.05 |

| Anorexia, vertigo general weakness etc. | 14 (40) | 17 (51.51) | 9.14±3.93 | 11.75±1.95 | <0.05* |

*Significant, P<0.05, **Between the groups. FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen

Comparative assessment of change in clinical status on World Health Organization ordinal scale

WHO ordinal scale was used to score improvement in clinical status of patients.[7] The total score in FAR group at the time of diagnosis of COVID infection was 105 (n = 35 with a score of 3 each) and 99 (n = 33 with a score of 3 each) in SOC group. During hospitalization, the total score in FAR group was 106 (n = 34 with score of 3 and 1 with score of 4) and 101 in SOC group (n = 31 with score of 3 and 2 patients with score of 4 each). At the end of the study, the score in both the groups was 0 as all the patients recovered.

Comparative assessment of disease progression and requirement of oxygen, intensive care unit admission, ventilator support and percent mortality

One patient in FAR group and two in control group required oxygen support. One patient required ICU admission in FAR group, while none of the patients required ICU admission in control group. None of the patients required ventilator support in any of the groups. There was no mortality in the study.

Assessment of number of days of hospitalization in the two groups

The average number of days of hospitalization in FAR group was 7.80 ± 2.81 while in the control group was 7.64 ± 3.17. Statistically, there was no significant difference between the groups.

Assessment of postclinical recovery

Post clinical recovery was assessed from baseline to the end of the study basis changes in parameters in parameters such as appetite, digestion, sleep, stress, anxiety, and physical weakness. A higher number of patients in the FAR group showed improvement in their appetite and digestion (74.28% and 54.54%), stress and anxiety levels (71.42% and 54.54%), sleep quality (31.42% and 27.27%) and physical strength levels (80% and 75.75%) in comparison to control group. Comparative assessment between the groups, however, showed no statistical difference.

Comparative assessment of requirement of rescue medications

Patients in both the groups were provided similar SOC consisting of antibiotics, antiallergics, antipyretics and multivitamins from the day of randomization to discharge. In FAR group, 33 (94.28%) patients were given antibiotics while 32 patients (96.96%) received antibiotics in SOC group during this period. Thirty-one patients (88.57%) required antipyretics/analgesics in FAR group, while the number was 29 (87.87%) in control group. Nineteen patients (54.28%) were given antiallergics/antihistamines in FAR group, while the number was 23 (69.69%) in control group. In FAR group, 31 (88.57%) were advised multivitamins and calcium supplements, while 33 (100%) patients were given these supplements in the control group. Two (5.71%) patients were given steroids in FAR group, while none were given steroid in control group. Further, 2 (5.71%) patients were given antiviral in FAR group, while three patients (9.09%) received antivirals in control group.

From the time of discharge to the end of the study, a statistically higher number of patients in SOC group were found to require rescue medications such as antibiotics and antipyretics/analgesics. None of the patients required steroids after discharge in either of the groups. One patient was given antiviral after discharge in control group, while none required them in FAR group. A total of 11 (31.42%) patients required tonics (multivitamins, calcium supplements) in the FAR group, while 18 (54.54%) required them in the control group [Table 11].

Table 11.

Assessment of requirement of rescue medications

| Drug categories | FAR group (n=35), SOC group (n=33) | Number of patients | P** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During hospitalization, n (%) | Discharge till EOS, n (%) | |||

| Antibiotics | FAR group | 33 (94.28) | 5 (14.28) | <0.05* |

| SOC group | 32 (96.96) | 13 (39.39) | ||

| Antiallergics/antihistamines | FAR group | 19 (54.28) | 5 (14.28) | >0.05 |

| SOC group | 23 (69.69) | 12 (36.36) | ||

| Antipyretics/analgesics | FAR group | 31 (88.57) | 6 (17.14) | <0.05* |

| SOC group | 29 (87.87) | 14 (42.42) | ||

| Steroids | FAR group | 2 (5.71) | 0 | NA |

| SOC group | 0 | 0 | ||

| Multi-vitamins and calcium supplements | FAR group | 31 (88.57) | 11 (31.42) | >0.05 |

| SOC group | 33 (100) | 18 (54.54) | ||

| Antivirals | FAR group | 2 (5.71) | 0 | NA |

*Significant, P<0.05, **Between the groups. FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care, EOS: End of study, NA: Not available

Comparative assessment of changes in quality of life

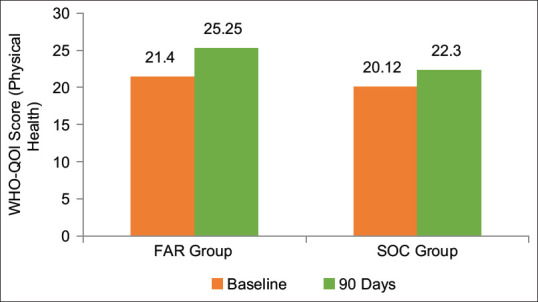

QOL was assessed using WHO QOL BREF[14] at the baseline, at discharge and at the end of the study on the basis of changes in four domains, namely physical, psychological, social and environmental health, as also, the overall QOL and the general health. All the assessed parameters of QOL showed improvement in both the groups at all the evaluated time points. Between the groups analysis, however, showed a significantly better improvement in FAR group in all the domains as compared to control group. There was a 66.11% higher improvement in physical health domain in FAR group as compared to control group [Table 12 and Figure 5].

Table 12.

Assessment of domain scores on World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale BREF Scale

| Group | Physical health | Psychological health | Social health | Environmental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | EOS | Baseline | EOS | Baseline | EOS | Baseline | EOS | |

| FAR | 21.4±3.18 | 25.25±4.81* | 18.62±3.01 | 22.68±2.65* | 7.97±2.41 | 9.71±2.55* | 25.97±4.09 | 29.28±3.43* |

| SOC | 20.12±3.17 | 22.30±3.93 | 19.63±2.36 | 20.75±2.29 | 9.69±1.66 | 10.15±1.52 | 26.03±3.88 | 27.78±3.73 |

| P** | >0.05 | <0.05* | >0.05 | <0.05* | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | <0.05* |

*Significant (P<0.05) from baseline, **Between the groups. FAR: Fixed ayurvedic regimen, SOC: Standard of care, EOS: End of study

Figure 5.

Physical health domain score of World Health Organization-Quality of Life scale

Global assessment of overall efficacy and safety as per physician and participants

Global assessment of overall efficacy as per the physician and participants showed improvement in all the patients in both the groups. Majority of the patients taking FAR showed very much improvement both as per investigators and the patients (62.85% and 65.71%), while SOC group showed much improvement (78.78% each). None of the patients in either of the groups showed worsening in the study. Assessment of overall safety by physician showed that maximum patients showed overall safety of FAR followed by good overall safety (71.42% and 25.71%) while assessment as per patients’ reported of excellent overall safety of FAR in majority followed by good overall safety (62.85% and 34.28%).

Assessment of safety

Safety evaluation based on occurrence of adverse event/serious adverse event

A total of eight AEs, four in each group, were recorded in the study. The common AEs in the study were loose motions, constipation, retrosternal burning, difficulty in breathing and joint pains. None of these AEs were assessed to be related to the study products. One SAE was reported in the study in the FAR group which resulted in admission to higher care facility. This SAE, in investigator's opinion, was assessed to be not related to the study products.

Safety evaluation based on laboratory parameters and vitals

Safety evaluation with respect to hematological and biochemical parameters, liver functions, renal functions, lipid profile and urinalysis done at the baseline and EOS did not show any significant change. Further, no significant change in vital parameters (pulse, temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure and SpO2 levels) was observed from baseline to discharge and further till the end of the study in both the study groups.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 infection was first reported in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019 and has since been recorded in virtually all nations of the world. Since its emergence, the race against time is on globally to assess various existing drugs for COVID-19 and to develop a safe and effective cure for the disease. Many allopathic, herbal and traditional medicines are being evaluated clinically for their preventive as well as curative roles against SARS-CoV-2. India too has recorded a huge number of cases followed by gradual stability and upsurges in pandemic situation. Many AYUSH drugs including Chyawanprash, Tulsi and Giloy have been advocated by the GoI for the prevention and management of COVID-19[15] and are being tested for their beneficial effects in its management.[16,17] The current study evaluated a FAR of Giloy Ki Ghan Vati, Tulsi tablets, Kalmegh tablets and Chyawanprash as add-on to conventional treatment/SOC in the management of mild and moderate COVID-19 patients. The rationale for selection of these drugs was traditional wisdom[18,19,20] and the abundant scientific data on the herbs Giloy (Tinospora Cordifolia Miers), Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum L.) and Kalmegh (Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees). A recently concluded clinical study concluded regular consumption of Chyawanprash plays a significant role in the prevention of infections including COVID-19 infection in the current pandemic. The severity of infection-related illnesses including COVID-19 also was found to be lower with the consumption of Chyawanprash.[21] Ministry of AYUSH in its various guidelines has recommended Chyawanprash both as a preventive measure and for aiding post-COVID recovery.[15,22]

This study was conducted at dedicated COVID-19 hospital and COVID care center in accordance with guidelines and regulations pertaining to diagnosis, investigations and testing, administration of SOC treatment and duration of hospital stay in pandemic situation issued by local health authorities. Guidelines issued by the Interdisciplinary Research and Development Task Force, Ministry of AYUSH, GoI, were followed with respect to development of protocol, sample size calculation, CRF development, etc., A total of 68 patients (35 in FAR and 33 in control/SOC group) were recruited in the study all of which completed the study. Primarily, patients of middle-aged males formed the study population. This finding is in line with the global findings where higher incidence of COVID-19 is reported among males compared to females.[23] Assessment of patients on ayurvedic clinical parameters in line with AYUSH guidelines was carried out in this study. Majority of the patients in both groups were found to possess digestive dysfunctions. Predominantly, imbalance of Vata and Kapha Doshas and Rasa and Rakta Dhatus was observed in both the groups. Earlier studies report patients with Vata-Kapha, Pitta-Kapha and Kapha-dominant Prakriti have been found more affected with COVID-19.[24]

Assessment of Vyadhi Adhisthan (seat of the disease) revealed that Pranvaha, Annavaha and Rasavaha channels (respiratory, digestive and circulatory systems) to be predominantly affected in both the groups. The findings are in line with earlier studies on COVID-19 profiling that report involvement of these channels considering febrile condition with respiratory symptoms, such as cough cold and breathing problems.[24] Considering the pathophysiology of infection of novel coronavirus and the observations of the Ayurvedic assessments of patients in both groups, COVID-19 could be correlated with Bhutabhishangaja Vyadhi/Bhutabhishangaja Jvara which is Samsargaja/Aupasargika in nature (a febrile contagious condition primarily affecting the respiratory system/lungs) described in ayurvedic texts.[25] In earlier researches too, COVID-19 infection had been provisionally understood from the ayurvedic perspective as Vata-Kapha-dominant Sannipatajvara of Agantu origin with Pittanubandha.[24,25]

The results of the present study revealed that patients administered FAR as add-on to conventional treatment recovered faster and earlier as compared those administered SOC only, as assessed by the lesser number of days required for clinical recovery from the day of randomization and also from the time of onset of symptoms of COVID-19. The clinical recovery was found to be 63.45% faster in FAR group when compared from the day of randomization and 51.34% faster when compared from the day of onset of symptoms. A significantly higher proportion of patients (P < 0.05) also showed faster and earlier recovery in FAR group as compared to control group within 1 and 2 weeks. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in the mean number of days required for testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 either from the day of randomization or from the day of onset of clinical symptoms.

Only a few patients in both the groups required ICU admission and oxygen support, while none of the patients required ventilator support in the both the groups, possibly due to inclusion of mild-to-moderate COVID infection only. No significant difference was observed in number of days of hospitalization between the groups. All the patients recovered completely toward the end of the study. No mortality was observed in any of the groups. Postrecovery from the illness, FAR group reported a significantly better improvement in appetite and digestion. A significant reduction in stress and anxiety levels was observed in FAR group in comparison to control. Statistically, no difference was observed on physical strength and sleep quality in both the groups. Assessment on WHO QOL parameters showed significantly better improvement in all the QOL parameters in FAR group compared to control group. Global assessment of the overall efficacy as per physician and patients revealed a better improvement in FAR group compared to control group. Assessment basis of requirement of rescue medications (antibiotics, analgesics, antipyretics, antiallergics, etc.) showed a significantly lesser number of patients required these in FAR group in comparison control group. The results of the study establish FAR as an effective add-on to the SOC in the management of mild-to-moderate cases of COVID-19 infection.

Assessment of overall safety as per physician and participants revealed excellent overall safety of both the treatment groups. A total of eight AEs, four in each group, such as loose motion, constipation and retrosternal burning, were recorded in the study. None of these AEs, however, were assessed to be related to the consumption of the study products. The one SAE recorded in the study in FAR group was also not assessed to be related in investigator's opinion. There was no significant change in the laboratory and vital parameters in both the study groups. These findings validate the safety of FAR as add-on to SOC in the management of mild-to-moderate cases of COVID-19.

The herbs Giloy, Tulsi and Kalmegh are renowned for their various health benefits in Ayurveda.[18,19,20] These herbs have exhibited antiviral,[26,27,28] anti-inflammatory,[29,30,31] immunomodulatory,[32,33,34] antiallergic,[35,36,37] antipyretic,[38,39,40] and antioxidant[41,42,43] potential in scientific studies. Chyawanprash is a traditionally renowned ayurvedic health supplement that has been studied extensively in scientific and clinical studies for its immunostimulatory,[44,45] antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials.[46] Beneficial effects have also been established on lung health against particulate matter-induced pulmonary disease in mice by estimating various cytokines and immunoglobulin.[45] Chyawanprash has also been established as a prophylactic measure for COVID-19 infection by virtue of its immunity-boosting effects.[21] A better and faster clinical recovery in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients administered FAR as an add-on to SOC can be attributed to the synergistic immunity and overall health-boosting effect of the herbs contained in Giloy Ki Ghan Vati, Tulsi tablets, Kalmegh tablets and Chyawanprash.

Strengths and limitations

FAR as add-on to conventional treatment/SOC resulted in faster and earlier clinical and postclinical recovery in mild-to-moderate-19 infection. A randomized control study with larger sample size and testing of certain laboratory parameters to evaluate the effect on inflammatory biomarkers and cytokines would help in further validation of study results.

CONCLUSION

FAR significantly reduced the clinical recovery time in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 infection when used as add-on conventional treatment or the SOC. Patients consuming FAR as an add-on to SOC showed a faster clinical recovery from the day of onset of symptoms by 51.34% (P < 0.05) as compared to SOC group. A significantly higher proportion of patients taking FAR showed recovery within the first 2 weeks as compared to those taking conventional treatment only. It was observed that 5 times more patients recovered within 7 days in FAR group when compared to control. A faster recovery was observed in clinical symptoms such as sore throat, cough, myalgia and loss of taste. Improvement in postclinical symptoms such as appetite, digestion, stress and anxiety was observed to be better with the use of FAR. Requirement of rescue medications such as antipyretics, analgesics and antibiotics was also found to be reduced in FAR group (P < 0.05). Further, FAR showed a significant improvement in all the assessed domains of QOL. None of the AEs/SAEs reported in the study were assessed to be related to study drugs. Further, FAR did not produce any significant change in the laboratory safety parameters and was assessed to be safe.

The study concludes FAR to be an effective and safe ayurvedic regimen as add-on to conventional treatment/SOC in the management of mild and moderate COVID-19 patients. The study outcomes establish the role of AYUSH interventions (FAR) as add-on to conventional treatment in management of newer diseases such as COVID-19 infection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Dabur India Limited.

Conflicts of interest

Arun Gupta, Rajiva K Rai, Sasibhushan Vedula and Ruchi Srivastava are employed with Dabur India Limited.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the team involved in the conduct of the study in these challenging times, especially, the team from CRO - Dr Swapnali Mahadik (Senior - Clinical Trial Monitor, Head – EDC and Data Management), Ms. Mansi Mehta (Senior CRC Mumbai and Clinical Trial Data Manager), Dr. Ruby Dubey (Senior CRC and Data Monitoring Executive), Dr. Shital Raka, Dr. Maya Patil, Dr. Shaligram Nerkar, Dr. Mahendra Shalunke (Clinical Research Coordinators), Dr. Vinay Pawar (Bio-Statistician and Medical Writing), Dr. Vyanketash Shivane (External Medical Expert), Dr. Shikha Mishra, Mr. Karun Wadhwa and Mr. Pankaj Kumar Gupta (Tulsi Tablets & Kalmegh Tablets) & Mr. Dharmendra Kumar (Dabur Chywanprash & Giloy ki Ghanvati) and Dr. Rugvedi Padmanabha (Dabur India Ltd. for Editorial Support).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicola M, O’Neill N, Sohrabi C, Khan M, Agha M, Agha R. Evidence based management guideline for the COVID-19 pandemic-Review article. Int J Surg. 2020;77:206–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tillu G, Salvi S, Patwardhan B. AYUSH for COVID-19 management. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020;11:95–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidelines in AYUSH Clinical Studies in COVID-19 Recommended by Interdisciplinary AYUSH R&D Task Force. Ministry of AYUSH. [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.ayush.gov.in/

- 5.Clinical Trials on AYUSH Interventions for COVID-19: Methodology and Protocol Development. A Publication by Interdisciplinary AYUSH Research and Development Task Force Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. of India April 2020. [Accessed 2020 Sep 04]. Available from: https://www.ayush.gov.in/docs/clinical-protocol-guideline.pdf .

- 6.Liu Y, Yan LM, Wan L, Xiang TX, Le A, Liu JM, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:656–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A Minimal Common Outcome Measure Set for COVID-19 Clinical Research. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S1473-3099%2820%2930483-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.WHO R&D Blueprint Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 Therapeutic Trial Synopsis. [Last accessed on 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/COVID-19_Treatment_Trial_Design_Master_Protocol_synopsis_Final_18022020.pdf .

- 9.Vahedi S. World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of their item response theory properties based on the graded responses model. Iran J Psychiatry. 2010;5:140–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhalerao S, Deshpande T, Thatte U. Prakriti (ayurvedic concept of constitution) and variations in platelet aggregation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:248. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajan S, Munjal Y, Shamkuwar M, Nimabalkar K, Sharma A, Jindal N, et al. Prakriti Analysis of COVID 19 patients: An observational study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2021:AT6631. [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patil VC, Baghel MS, Thakar AB. Assessment of Agni (digestive function) and Koshtha (bowel movement with special reference to Abhyantara snehana (internal oleation) Anc Sci Life. 2008;28:26–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Singh G, Patwardhan K, Gehlot S. Development, validation and verification of a self-assessment tool to estimate agnibala (digestive strength) J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22:134–40. doi: 10.1177/2156587216656117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol .

- 15.Ministry of AYUSH: Ayurveda's Immunity Boosting Measures for Self-Care during COVID 19 Crisis. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.ayush.gov.in/docs/123.pdf .

- 16.Devpura G, Tomar BS, Nathiya D, Sharma A, Bhandari D, Haldar S, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial on the efficacy of ayurvedic treatment regime on COVID-19 positive patients. Phytomedicine. 2021;84:153494. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shree P, Mishra P, Selvaraj C, Singh SK, Chaube R, Garg N, et al. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytochemicals of ayurvedic medicinal plants-Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha), Tinospora cordifolia (Giloy) and Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) – A molecular docking study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1810778. [doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1810778]. [Ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monograph on Giloy. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India. Part I. I. Government of India, Ministry of AYUSH; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monograph on Tulsi. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India. Part I. II. Government of India, Ministry of AYUSH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monograph on Kalmegh. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India. Part I. VIII. Government of India, Ministry of AYUSH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical Evaluation of Dabur Chyawanprash (DCP) as a Preventive Remedy in Pandemic of COVID-19 – An Open Label, Multi Centric, Randomized, Comparative, Prospective, Interventional Community Based Clinical Study on Healthy Individuals. [Last accessed on 2021 Feb 05]. Available from: http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/rmaindet.php?trialid=43374&EncHid=64708.23959&modid=1&compid=19 .

- 22.Health Ministry Boosting Guidelines for Recovered Covid-19 Patients. [Last accessed on 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: https://ayushnext.ayush.gov.in/detail/writeUps/health-ministry-boosting-guidelines-forrecovered-covid-19-patients-1 .

- 23.Bwire GM. Coronavirus: Why Men are More Vulnerable to Covid-19 Than Women? SN Compr Clin Me. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00341-w. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puthiyedath R, Kataria S, Payyappallimana U, Mangalath P, Nampoothiri V, Sharma P, et al. Ayurvedic clinical profile of COVID-19-A preliminary report. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.05.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurao RP, Namburi SU, Kumar S* Pathogenesis of COVID 19: A review on integrative understanding through Ayurveda. J Res Ayurvedic Sci. 2020;4:104–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury P. In silico investigation of phytoconstituents from Indian medicinal herb ‘Tinospora cordifolia (giloy)’ against SARSCoV-2 (COVID-19) by molecular dynamics approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803968. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghoke SS, Sood R, Kumar N, Pateriya AK, Bhatia S, Mishra A, et al. Evaluation of antiviral activity of Ocimum sanctum and Acacia Arabica leaves extracts against H9N2 virus using embryonated chicken egg model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:174. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enmozhi SK, Raja K, Sebastine I, Joseph J. Andrographolide as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: An in silico approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1760136. [doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1760136] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patgiri B, Umretia BL, Vaishnav PU, Prajapati PK, Shukla VJ, Ravishankar B. Anti-inflammatory activity of Guduchi Ghana (aqueous extract of Tables Tinospora cordifolia Miers.) Ayu. 2014;35:108–10. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.141958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, Agrawal SS. Anti-asthmatic and anti-inflammatory activity of Ocimum sanctum. Int J Pharmacogn. 1991;29:306–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abu-Ghefreh AA, Canatan H, Ezeamuzie CI. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory effects of andrographolide. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma U, Bala M, Kumar N, Singh B, Munshi RK, Bhalerao S. Immunomodulatory active compounds from Tinospora cordifolia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141:918–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkatachalam VV, Rajinikanth B. Immunomodulatory activity of aqueous leaf extract of Ocimum sanctum. In: Malathi R, Krishnan J, editors. Recent Advancements in System Modelling Applications. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering. Vol. 188. India: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Wang J, Dong SF, Liu CH, Italiani P, Sun SH, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of andrographolide on macrophage activation and specific antibody response. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:191–201. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zalawadia R, Gandhi C, Vaibhav Patel V, Balaraman R. The protective effect of Tinospora cordifolia on various mast cell mediated allergic reactions. Pharm Biol. 2009;47:1096–106. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sim LY, Abd Rani NZ, Husain K. Lamiaceae: An insight on their anti-allergic potential and its mechanisms of action. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:677. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta PP, Tandon JS, Patnaik JK. Antiallergic activity of andrographolides isolated from Andrographis paniculata (Burm.F) Wall. Pharm Biol. 1998;36:1, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussain L, Akash MS, Ain NU, Rehman K, Ibrahim M. The analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic activities of Tinospora cordifolia. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24:957–64. doi: 10.17219/acem/27909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balakrishna V, Pamu S, Pawar D. Evaluation of anti-pyretic activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn using Brewer's yeast induced pyrexia in albino rats. J Innov Pharm Sci. 2017;1:55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balu S, Boopathi CA, Elango V. Antipyretic activities of some species of Andrographis wall. Anc Sci Life. 1993;12:399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince PS, Menon VP. Antioxidant activity of Tinospora cordifolia roots in experimental diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65:277–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhary A, Sharma S, Mittal A, Gupta S, Dua A. Phytochemical and antioxidant profiling of Ocimum sanctum. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57:3852–63. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dandu AM, Inamdar NM. Evaluation of beneficial effects of antioxidant properties of aqueous leaf extract of Andrographis paniculata in STZ-induced diabetes. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2009;22:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madaan A, Kanjilal S, Gupta A, Sastry JL, Verma R, Singh AT, et al. Evaluation of immunostimulatory activity of Chyawanprash using in vitro assays. Indian J Exp Biol. 2015;53:158–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta A, Kumar S, Dole S, Deshpande S, Singh S, et al. Evaluation of cyavanaprasa on health and immunity related parameters in healthy children: A two arm, randomized, open labelled, prospective, multicenter, clinical study. Anc Sci Life. 2017;36:141–50. doi: 10.4103/asl.ASL_8_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma R, Martins N, Kuca K, Chaudhary A, Kabra A, Rao MM, et al. Chyawanprash: A traditional Indian bioactive health supplement. Biomolecules. 2019;9:161. doi: 10.3390/biom9050161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]