Abstract

PURPOSE:

To characterize the progression of optical gaps and expand the known etiologies of this phenotype.

DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort study.

METHODS:

Thirty-six patients were selected based on the identification of an optical gap on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) from a large cohort of patients (n=746) with confirmed diagnoses of inherited retinal dystrophy. The width and height of the gaps in 70 eyes of 36 patients were measured using the caliper tool on Heidelberg Explorer by two independent graders. Measurements of outer and central retinal thickness were also evaluated and correlated with gap dimensions.

RESULTS:

Longitudinal analysis confirmed the progressive nature of optical gaps in patients with Stargardt disease, achromatopsia, occult macular dystrophy, and cone dystrophies (p<0.003). Larger changes in gap width were noted in patients with Stargardt disease (78.1μm/year) and cone dystrophies (31.9μm/year) as compared to patients with achromatopsia (16.2μm/year) and occult macular dystrophy (15.4μm/year). Gap height decreased in patients with Stargardt disease (6.5μm/year) (p=0.02), but increased in patients with achromatopsia (3.3μm/year) and occult macular dystrophy (1.2μm/year). Gap height correlated with measurements of central retinal thickness at the fovea (r=0.782, p=0.00012). Interocular discordance of the gap was observed in 7 patients. Finally, a review of all currently described etiologies of optical gap was summarized.

CONCLUSION:

The optical gap is a progressive phenotype seen in an increasing number of etiologies. This progressive nature suggests a use as a biomarker in the understanding of disease progression. Interocular discordance of the phenotype may be a feature of Stargardt disease and cone dystrophies.

Introduction

Optical gap is an occult macular phenotype that is most discernible on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) in a number of inherited retinal dystrophies. It is characterized by a focal loss of the photoreceptor-attributable ellipsoid zone (EZ) band, previously known as the inner segment and outer segment junction (IS/OS junction), in the fovea and parafoveal region. This phenotype was first described in 2006 by Barthelemes et al. in patients with achromatopsia.1 Soon afterwards, Leng et al. expanded the differential associated with optical gaps to include Stargardt disease as well as dominant cone dystrophies caused by mutations in cyclase proteins.2 Since then, individual case reports detailing novel etiologies of both hereditary and non-hereditary optical gap have been slowly growing in the literature.

The pathogenesis of this finding has previously been a subject of interest in several etiologies of the phenotype. Nõupuu et al. developed a three part staging system using cross-sectional data to suggest progression of the phenotype and noted longitudinal progression from one stage to another in several patients with Stargardt disease.3 Greenberg et al. similarly created a five-step staging system in patients with achromatopsia, but that study was also limited by the use of cross sectional data.4 The clinical significance of the optical gap has been suggested as a potential outcome measure in clinical trials for achromatopsia.4 Longitudinal data of phenotypic progression in individual patients has been attempted in the pediatric achromatopsia population.5 However, it has otherwise not been well characterized and has implications to not only improve our understanding of the optical gap but also determine the necessary length of clinical trials that may use optical gap as an outcome measure.5

The present study describes the analysis of 36 genetically heterogeneous patients with the optical gap phenotype, including two patients harboring mutations in novel candidate genes associated with this phenotype, RAB28 and PITPNM3. Moreover, this study details the longitudinal analysis of 19 individual patients in order to better understand phenotype progression and natural history over time. The authors additionally perform a review of the current literature of this phenotype. This information provides an updated differential diagnosis of optical gap since it was first described in 2006, so as to better guide clinicians who may encounter this phenotype in practice.2

Methods

Subject Selection

A retrospective review was performed of 746 patients with both a clinical and molecular genetic diagnosis of inherited retinal dystrophy who were seen and evaluated at the Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute at Columbia University Irving Medical Center between 2009 and 2019. Retinal images from previous visits were evaluated for the presence of an identifiable loss of reflectance and disruption of the EZ line in the fovea or the parafoveal regions on SD-OCT. Patients with disruptions of the outer retinal layers secondary to macular telangiectasias, vitelliform macular dystrophies, vitreomacular traction, secondary macular neovascular disease and macular holes were excluded. A total of 36 patients were identified who fit the inclusion criteria. This study offered minimal risk to the patients, and due to its retrospective design, patient consent was waived as described in Columbia University Irving Medical Center Institutional Review Board-approved protocol AAAR8743. All procedures were reviewed and deemed to be in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ophthalmic Examination & Imaging

Patients underwent initial ophthalmic examination including measurement of best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), dilation with topical tropicamide (1%) and phenylephrine (2.5%), and fundus examination by a retinal specialist (S.H.T). Additionally, patients underwent multimodal imaging including SD-OCT, short wavelength autofluorescence (SW-AF), and wide field color fundus photography. Full-field electroretinograms (ffERG) were obtained from patients using Dawson, Trick, and Litzkow (DTL) electrodes and Ganzfeld stimulation using a Diagnosys Espion Electrophysiology System (Diagnosys LLC, Littleton, MA, USA) according to ISCEV standards.6 SD-OCT and SW-AF were acquired using a Spectralis HRA+OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Color fundus photography was obtained using an Optos 200 Tx (Optos, PLC, Dunfermline, United Kingdom).

Optical Gap Progression & Statistical Analysis

Disease progression was assessed between initial and follow-up visit using the change in the horizontal (nasal-temporal axis) and vertical (anterior-posterior axis) lengths of the optical gap on corresponding fovea-aligned SD-OCT scans as measured by two independent graders (J.O. and J.R.). Optical gap width was defined as the longest contiguous length of the disruption in the EZ band with the presence of a vacant space in its place (Supplemental Fig. 1A–D, green lines, Supplemental Material at AJO.com). In cases where residual EZ was observed at the fovea but a distinct optical gap was identified on either side of the residual EZ, the residual EZ was included within the measurements. Optical gap height was defined as the distance between the external limiting membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane complex at the fovea (Supplemental Fig. 1A, yellow lines, Supplemental Material at AJO.com). In cases with multiple follow-up visits, measurements were taken between the initial and most recent follow-up visit in which an optical gap was seen in both eyes. In cases with only one follow-up visit in which one eye demonstrated the presence of a gap and the other eye had a gap that had become atrophic, measurements were taken from the single eye with the gap. Areas of peripheral collapse of the retina into the optical gap were not included as part of the optical gap measurements. Measurements were performed with the caliper tool on the Heidelberg Explorer (HEYEX). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated for measurements to determine the reliability of inter-grader variability.

Measurements of central retinal thickness at the fovea (CRTF) and outer retinal thickness (ORT) across the retina were also evaluated between initial and follow-up visit. CRTF was defined as the distance between the RPE-Bruch’s membrane complex and the internal limiting membrane. ORT was defined as the distance between the RPE-Bruch’s membrane complex and the boundary between the outer nuclear and outer plexiform layers. Each scan was manually segmented on HEYEX and then exported. The thicknesses were calculated by a computing software (MATLAB program; The Mathworks, Inc) previously developed and described by Hood et al.7

When available, all measurements were taken using follow-up scans that used automatic real-time tracking to align with baseline images. When matched scans were unavailable for initial and most recent visit, measurements were taken at the fovea from both visits. A paired sample t-test was performed to compare longitudinal measurements of optical gap dimensions and retinal thickness. Correlation of changes in optical gap dimensions with logMAR visual acuity and retinal thickness measurements were also performed. Analysis was performed using R statistical software version 3.6.1 (Vienna, Austria).

Review of the Literature

A review of the current literature was performed using the search terms “foveal cavitation”, “optical gap”, “disruption of the EZ line”, and “disruption of the IS/OS junction” on PubMed to identify other etiologies of optical gap and clarify the differential diagnosis of the phenotype. Review of all other known etiologies of cone and cone-rod retinal dystrophies was also performed. All reviews, original articles, case series, and case reports were included. Manuscripts with evidence of OCT findings consistent with the aforementioned definition of foveal cavitation or optical gap were examined and included in the review.

Results

Clinical Summary

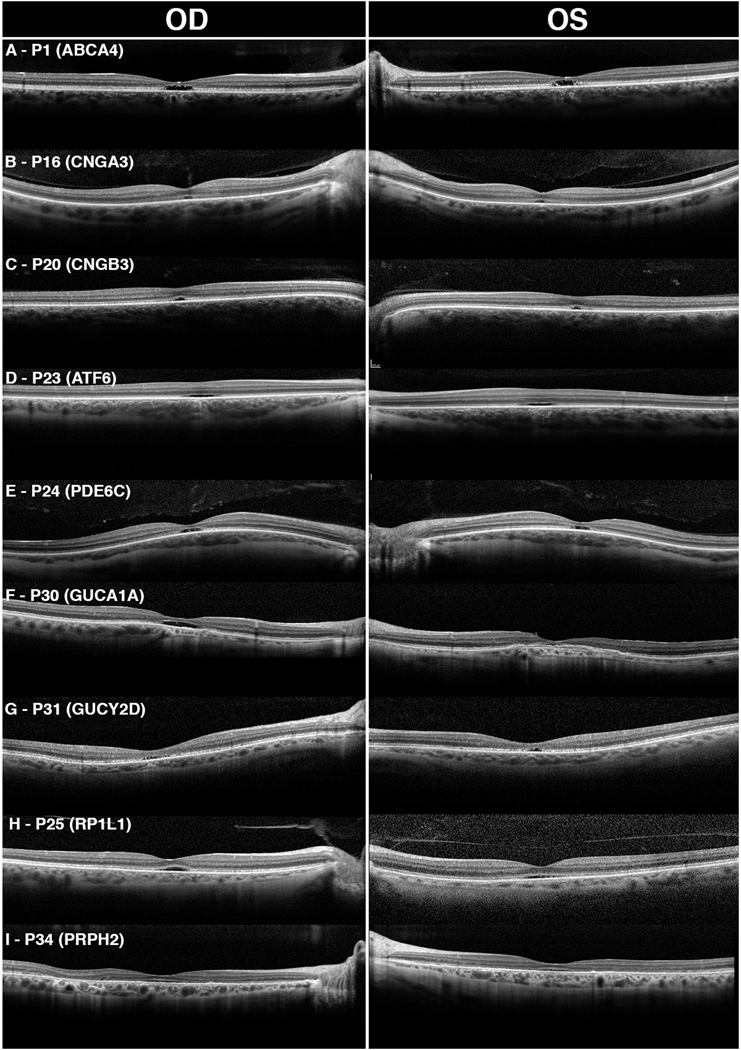

The clinical, genetic, and demographic information of these patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 76 eyes from 38 patients were evaluated for optical gaps. The patients had a mean and median age of 34.6 and 27.5 years (range: 11–77), respectively, at initial evaluation. Twelve patients (P1-P12) presented with a diagnosis of electrophysiologic group I Stargardt disease caused by mutations in ABCA4. Twelve patients (P13-P24) presented with a diagnosis of achromatopsia – six caused by mutations in CNGA3, two in CNGB3, three in AFT6, and one in PDE6C. Five patients (P25-P29) presented with occult macular dystrophy caused by mutations in RP1L1, and three patients (P30-P32) were diagnosed with cone dystrophy caused by guanylate cyclase mutations in the GUCY2D and GUCA1A genes. Two cases of pattern macular dystrophy caused by PRPH2 mutation were identified (P33, P34). Two novel candidate etiologies of optical gap were also evaluated: cone dystrophy caused by two mutations in RAB28 (P35) and cone dystrophy caused by a single mutation in PITPNM3 (P36). Example SD-OCT images of each etiology of optical gap are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 36 patients with optical gaps

| ID | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Gene | Variant | Age of Onset | BCVA (OD, OS) | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 26/M | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.4139C>T:p.Pro1380Leu, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

20 | 20/60, 20/60 | Y |

| P2 | 26/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.1622T>C:p.Leu541Pro, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

24 | N/A | Y |

| P3 †,§ | 26/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.1622T>C:p.Leu541Pro, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

18 | 20/250, 20/250 | N |

| P4 †,§ | 23/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.1622T>C:p.Leu541Pro, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

15 | 20/80, 20/80 | N |

| P5§ | 25/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.286A>G:p.Asn96Asp, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

24 | 20/40, 20/30 | N |

| P6§ | 27/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu, c.6448T>C:p.Cys2150Arg |

15 | 20/150, 20/150 | Y |

| P7§ | 23/M | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu, c.5318C>T:p.Ala1773Val |

22 | 20/40, 20/30 | Y |

| P8§ | 23/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.4139C>T:p.Pro1380Leu, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

18 | 20/40, 20/30 | Y |

| P9 | 23/M | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.1622T>C:p.Leu541Pro, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

23 | N/A | N |

| P10 | 25/F | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu, c.5196+1056A>G |

21 | 20/50, 20/100 | Y |

| P11§ | 13/M | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.2461T>A:p.Trp821Arg, c.6448T>C:p.Cys2150Arg |

11 | 20/150, 20/200 | Y |

| P12 | 26/M | Stargardt | ABCA4 | c.3065A>G:p.Glu1022Gly, c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu |

26 | 20/30, 20/30 | 3 |

| P13* | 30/M | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.1391T>G:p.Leu464Arg, c.1621C>A:p.Leu541Phe |

25 | 20/125, 20/125 | Y |

| P14* | 63/M | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.829C>T p.Arg277Cys, c.847C>T:p.Arg283Trp |

N/A | 20/150, 20/150 | Y |

| P15 | 45/F | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.1702G>A:p.Gly568Arg, c.1823T>A: p.Leu608Gln |

Childhood | 20/100, 20/100 | Y |

| P16* | 34/M | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.830G>A:p.Arg277His, c.1070A>G:p.Tyr357Cys |

N/A | 20/100, 20/150 | Y |

| P17* | 23/M | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.1391T>G:p.Leu464Arg, c.1641C>A:p.Phe547Leu |

1.5 | 20/50, 20/50 | Y |

| P18 | 47/M | Achromatopsia | CNGA3 | c.1669G>A:p.Gly557Arg, c.667C>G:p.Arg223Gly |

5 | 20/150, 20/125 | Y |

| P19* | 32/M | Achromatopsia | CNGB3 | c.1432C>T p.Arg478Ter, c.1432C>T p.Arg478Ter |

23 | 20/160, 20/200 | Y |

| P20* | 46/F | Achromatopsia | CNGB3 | c.1056–3C>G het | Childhood | 20/80, 20/80 | Y |

| P21†, ‡ |

12/F | Achromatopsia | ATF6 | c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys, c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys |

6 | 20/200, 20/200 | Y |

| P22 †,‡ | 23/M | Achromatopsia | ATF6 | c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys, c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys |

18 | 20/63, 20/100 | Y |

| P23 †,‡ | 18/F | Achromatopsia | ATF6 | c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys, c.970C>T:p.Arg324Cys |

12 | 20/100, 20/63 | Y |

| P24 | 32/M | Achromatopsia | PDE6C | c.1759T>C:p.Tyr587His, c.1759T>C:p.Tyr587His |

Childhood | 20/100, 20/150 | Y |

| P25 | 56/F | Occult Macular Dystrophy | RP1L1 | c.133C>T:p.Arg45Trp, c.449C>T:p.Thr150Ile |

51 | 20/100, 20/125 | Y |

| P26 | 65/M | Occult Macular Dystrophy | RP1L1 | c.133C>T:p.Arg45Trp | 49 | 20/70, 20/60 | Y |

| P27† | 25/M | Occult Macular Dystrophy | RP1L1 | c.133C>T:p.Arg45Trp | N/A | N/A | Y |

| P28† | 23/M | Occult Macular Dystrophy | RP1L1 | c.133C>T:p.Arg45Trp | 12 | 20/80, 20/80 | Y |

| P29 | 43/F | Occult Macular Dystrophy | RP1L1 | c.133C>T:p.Arg45Trp | 33 | 20/60, 20/60 | Y |

| P30 | 77/F | Cone Dystrophy | GUCA1A | c.526C>T:p.Leu176Phe | 45 | 20/125, 20/200 | N |

| P31 | 66/M | Macular Dystrophy | GUCY2D | c.2516C>T:Thr839Met | 64 | 20/100, 20/80 | Y |

| P32 | 24/F | Cone Dystrophy | GUCY2D | c.2513G>A:p.Arg838His | 24 | N/A | N |

| P33 | 49/F | Macular Dystrophy | PRPH2 | c.424C<T:p.Arg142Trp | Childhood | 20/50, 20/50 | Y |

| P34 | 56/F | Macular Dystrophy | PRPH2 | c.514C>T p.Arg172Trp | 56 | 20/60, 20/60 | Y |

| P35 | 41/M | Cone Dystrophy | RAB28 | c.136G>C:p.Gly46Arg, c.70G>C: p.Gly24Arg |

42 | 20/70, 20/70 | N |

| P36 | 51/F | Cone Dystrophy | PITPNM3 | c.227_229del:p.Gly76del | 45 | 20/80, 20/CF | N |

BCVA – best corrected visual acuity, OD – right eye, OS – left eye, N/A – not available

sibling pairs: P3 & P4 and P21, P22, & P23 and P27 & P28

Subject previously reported by Noupuu et al.

Subject previously reported by Greenberg et al.

Subject previously reported by Kohl et al

Figure 1. Previously described etiologies of optical gap as seen on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography.

Optical gap in Stargardt disease (A) was characterized by bilateral ovoid subfoveal cavities that contain photoreceptor debris. Hyperreflectance of the external limiting membrane (ELM) was also characteristic. Patients with achromatopsia due to mutations in CNGA3 (B), CNGB3 (C), ATF6 (D), and PDE6C (E) presented with small subfoveal gaps that were flat with less bowing of the ELM. Foveal hypoplasia was noted in several of these patients (C, D). Optical gap was also seen in patients with cone dystrophies caused by mutations in cyclase proteins, GUCA1A (F) and GUCY2D (G). P30 presented with a large, empty, ovoid gap in the right eye with hypertransmission into the choroid and hyperreflectance of the ELM. The left eye had a gap that was occupied by a foveal detachment of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). P31 presented with a small, bilateral ovoid gap without evidence of RPE atrophy. Occult macular dystrophy (H) and PRPH2 mediated macular dystrophy (I) caused small, symmetric subfoveal gaps containing photoreceptor debris. Hyperreflectance of the ELM was absent in both conditions.

The optical gap phenotype was characterized across different disease groups based on a number of features seen on SD-OCT, including EZ disruption and external limiting membrane (ELM) reflectivity, age of onset and age at evaluation, BCVA, and a number of other traits as summarized in Table 2. A distinction was made during analysis between Stargardt disease, occult macular dystrophy, and other causes of cone and macular dystrophies due to the larger number of patients with Stargardt disease and occult macular dystrophy with identified optical gaps, allowing for a more detailed description of disease specific characteristics. Notably, both the age of onset and age at which the phenotype was noticed were significantly lower in patients with achromatopsia and Stargardt disease as compared to patients with cone or macular dystrophies (p<0.001). No significant difference was seen in logMAR BCVA between diagnoses.

Table 2.

Characteristics of optical gap phenotype by diagnosis

| Diagnosis | Patients | Age of onset | Average gap width (μm) | Average gap height (μm) | EZ disruption | ELM Reflectivity | Changes on AF | Disease Duration | Average BCVA at presentation | Interocular Discordance | ffERG | Other characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STGD | 12 | 19.8±4.4 | 704.0±287.3 | 51.8±23.2 | Continuous | Yes | Yes | Progressive | 0.614 (n=10) | Yes | Unchanged | HyperAF flecks |

| ACHM | 12 | 12.9±9.2† | 679.4±408.4 | 52.0±49.7 | Continuous | Yes | Yes | Slowly progressive | 0.752 (n=12) | No | Decreased photopic | Foveal hypoplasia |

| CORD/M D |

7 | 44.5±12.9 § |

1504.6±852. 7 | 40.5±17.2 | Intermittent | Yes | Yes | Progressive | 0.631 (n=6) | Yes | Decreased photopic | Central lesion on AF and fundus exam |

| OMD | 5 | 36.3±18.1 | 547.1±242.9 | 30.3±9.1 | Intermittent | No | Occult | Slowly progressive | 0.641 (n=4) | No | Unchanged | Abnormal mfERG |

3 patients noted onset from childhood who were not included

1 patient noted onset from childhood who was not included,

STGD – Stargardt disease, ACHM – achromatopsia, CORD/MD – cone, cone-rod dystrophy and macular dystrophy, OMD – occult macular dystrophy EZ – ellipsoid zone, ELM – external limiting membrane, AF – autofluorescence, BCVA – best corrected visual acuity, ffERG – full field electroretinogram, mfERG – multifocal electroretinogram

RAB28-related Optical Gap

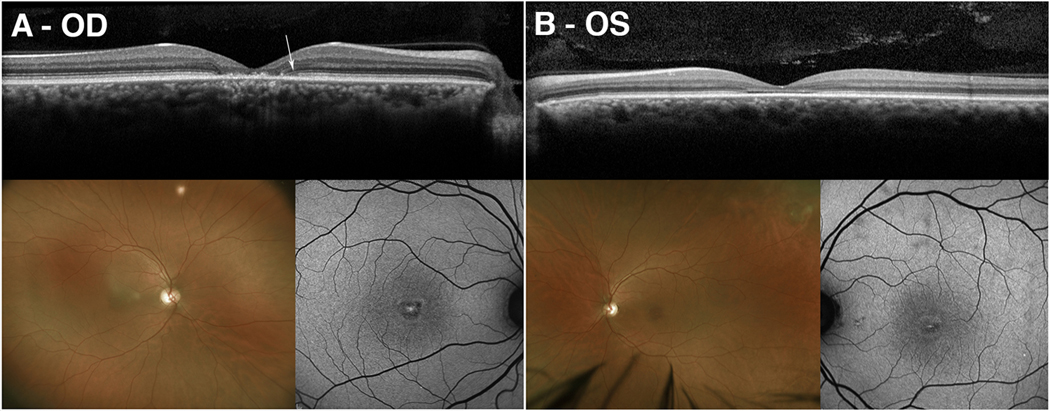

P35 was a 41-year-old male who was initially referred for the evaluation of Stargardt disease. Per family history, the patient had one unaffected sister and one brother with macular dystrophy. At the initial visit, his BCVA was 20/70 in both eyes. A targeted retinal dystrophy panel using whole exome sequencing identified two compound heterozygous mutations, c.860>G:p.(Gly46Arg) and c.70G>C:p.(Gly24Arg), in the candidate gene, RAB28, which is known to cause autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy.8 Segregation analysis using parental samples confirmed that the two variants were located on separate chromosomes. Neither variant was found in population databases, and in silico tools predicted both variants to be deleterious and damaging. On SD-OCT, the patient presented with discordant optical gap in the left eye and foveal atrophy with thinning of the outer retinal layers in the right eye (Fig. 2A–B). Color fundus photography revealed central foveal atrophy which was also seen on SW-AF surrounded by a hyperautofluorescent ring (Fig. 2A–B). ffERG demonstrated spared scotopic responses with significant amplitude attenuation and implicit time delay of the 30 Hz flicker.

Figure 2. Multimodal imaging of RAB28 mediated optical gap.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of a 41-year-old man (P35) with compound heterozygous mutations in RAB28 demonstrated the presence of atrophy and loss of retinal architecture at the fovea on SD-OCT in the right eye (A). In contrast, the left eye demonstrated the presence of an optical gap with hyperreflectance of the external limiting membrane (B). A residual optical gap phenotype was seen in the right eye as previously described by Nõupuu et al. (A, white arrow). Color fundus photography revealed bilateral foveal atrophy which was also seen on short-wavelength autofluorescence imaging surrounded by hyperautofluorescent rings (A-B).

PITPNM3-related Optical Gap

P36 was a 51-year-old woman who presented for progressively worsening vision with a referring diagnosis of cone dystrophy. Past medical, ocular, and family history were unremarkable. At the initial visit, BCVA was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left eye. At three and five-year follow-up visits, the patient’s vision decreased from 20/50 to 20/80 in the right eye and from 20/80 to 20/100 in the left eye. Whole exome sequencing identified a c.227_229delCTC:p.(Gly76del) in-frame deletion variant in the candidate gene, PITPNM3. This variant was found to occur at a low allelic frequency of 0.00002166 in gnomAD, suggesting that this is not a common variant, and in silico prediction tools predicted this mutation to be deleterious to protein structure. PITPNM3 is known to be a rare cause of cone-rod dystrophy and segregation analysis of this variant was not performed due to inability to obtain familial samples.9,10

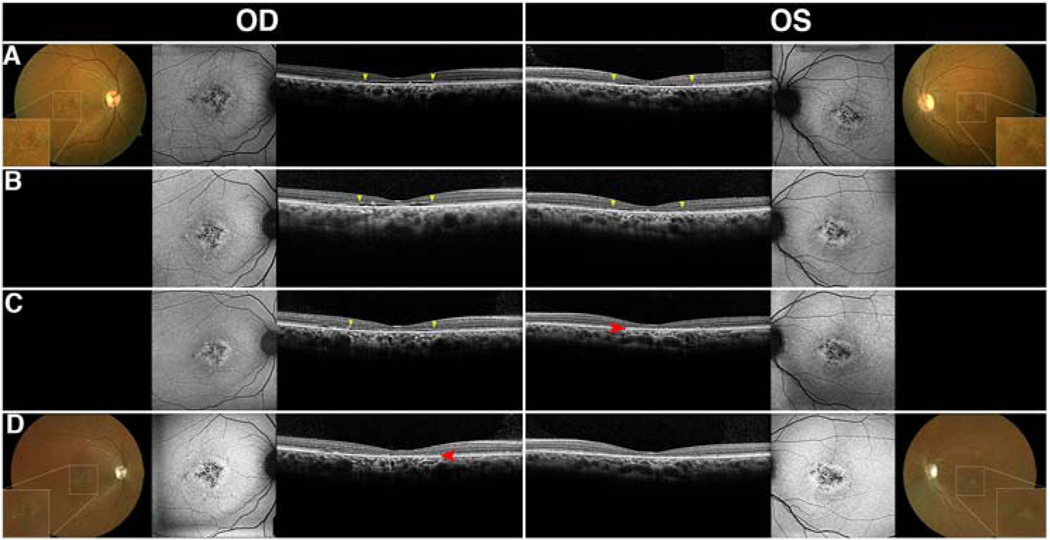

At the initial visit, SD-OCT revealed symmetric, ovoid optical gaps characterized by photoreceptor debris projecting anteriorly to the foveal ELM, and hypertransmission of the choroidal signal underneath the fovea (Fig. 3A). The ELM in this patient was not hyper-reflective, like those commonly seen in patients with achromatopsia or Stargardt disease.3,4,11 However, sparing of the foveal EZ relative to the parafoveal EZ was seen, as has been described in a cohort of patients with early stage Stargardt disease (Fig. 3A).12 Over the course of five years, follow-up visits revealed incremental widening and eventual collapse of the neurosensory retina into the optically empty cavity (Fig. 3A–D). These changes notably occurred at different time points for each eye. Collapse of the inner retina in the left eye was detected four years after initial presentation, while collapse was noted in the right eye 1 year later (Fig. 3B–C). BCVAs before and after collapse were stable at 20/100 in the left eye but decreased from 20/50 to 20/80 in the right eye. Despite the structural change shown on SD-OCT, the patient denied any subjective changes to vision.

Figure 3. Multimodal imaging of PITPNM3 mediated optical gap.

Spectral-domain-optical coherence tomography images of a 51-year-old woman (P36) with a heterozygous mutation in PITPNM3 revealed a bilateral, symmetric optical gap and hypertransmission into the choroid (A). Gradual changes in optical gap width were observed over the course of follow-up at 1 year, 4 years, and 5 years, respectively (B, C, D, yellow arrows). The optical gap was observed to progress asymmetrically as it widened in the right eye (B), but narrowed in the left eye due to collapse along the nasal and temporal edges of the gap (C). Complete atrophy of the gap was observed at 4 years in the left eye (C, red arrow), and 5 years in the right eye (D, red arrow).

SW-AF images obtained at the initial visit revealed intermittent patches of central RPE atrophy surrounded by fleck-like lesions and parafoveal mottling (Fig. 3A). Throughout follow-up, parafoveal atrophy increased in size (Fig. 3B–D). The ffERG at the initial visit demonstrated preserved scotopic responses with significant attenuation of 30 Hz flicker amplitude with implicit time delay bilaterally consistent with generalized cone dysfunction. Over the course of follow-up, rod responses remained spared, but photopic 30 Hz flicker amplitudes further decreased.

Interocular Discordance and Early Foveal Sparing of Optical Gap Phenotype

On SD-OCT, seven (P3, P4, P9, P30, P32, P35, and P36) out of 19 patients with Stargardt disease or cone-rod and macular dystrophies presented with interocular discordance of the optical gaps or showed progression from one stage to another at different time points throughout their follow-up (Fig. 4). Typically, this was seen as the collapse of the optical gap in one eye while the optical gap in the other eye retained the integrity of the cavity. Using the staging system previously described for Stargardt disease, this meant that one eye progressed from Stage II to Stage III while the other remained in Stage II.3 The residual patterns of the optical gap phenotype can sometimes be seen in these patients following atrophy. This is characterized by an optically empty space between the preserved EZ-line and the location of neurosensory collapse (Fig. 4, white arrows), which is eventually eliminated by progressive atrophy.3 In contrast, all achromatopsia patients with the optical gap phenotype and confirmed CNGA3, CNGB3, PDE6C, or ATF6 mutations were found to have interocular agreement of the phenotype based on cross-sectional analysis of 7 patients and longitudinal analysis of 5 patients.

Figure 4. Interocular discordance in patients with optical gaps.

Interocular discordance of optical gap was observed in five patients (P3, P4, P9, P30, P32) with cone-first retinal degenerations at presentation (A-E). Three patients (P3, P4, P9) were found to have asymmetric disease with optical gap and residual foveal photoreceptors in one eye and collapse of the retina into the cavity with loss of the inner and outer retinal layers in the other eye (A-C). P30 presented a preserved optical gap in the right eye while the left eye demonstrated detachment of the retinal pigment epithelium and consequent occupation of the space. P32 presented with a visible optical gap in the left eye and intermittent disruptions of the ellipsoid zone-line indicative of impending gap formation in the right eye.

Additionally, a relative sparing of the foveal EZ was seen in a total of 9 eyes from 5 patients (P6, P8, P19, P25, P36). This was consistent with prior reports of early foveal sparing in patients with early-stage Stargardt disease.12 In this cohort, this phenotype was seen not only in Stargardt disease but also in patients with cone dystrophy, achromatopsia, and occult macular dystrophy.

Optical Gap Progression & Correlates

Progression of the optical gap phenotype was analyzed using longitudinal data from 19 patients (nine ABCA4, two CNGA3, one CNGB3, two ATF6, three RP1L1, one PITPNM3, and one GUCY2D) over a mean and median follow-up interval of 3.3 and 2.7 years, respectively. Thirty-four of thirty-eight eyes exhibited increases in optical gap width between the initial and final visit, suggesting that the optical gap phenotype is progressive and enlarging (p<0.001). Mean increase in optical gap width was 78.1±34.8 μm/year in patients with Stargardt disease, 16.2±11.5μm/year in patients with achromatopsia, 31.9±46.3 μm/year in patients with non-Stargardt cone dystrophies, and 15.4±11.3μm/year in patients with occult macular dystrophy. In the right eye of P2, a decrease in gap width was observed between initial and final visit due to collapse of the optical gap along the nasal and temporal edges of the gap (Supplemental Fig. 1B, Supplemental Material at AJO.com). These areas were not included in the measurements. In the left eye of P36, a reduction in the gap width was noted due to the collapse of the neurosensory retina along the temporal margin of the optical gap (Supplemental Fig. 1C–D, Supplemental Material at AJO.com). Finally, the right eyes of P3 and P4 were excluded from analysis as the optical gaps had progressed to complete atrophy between initial and second visits.

While a significant decrease in optical gap height of 6.5±6.1 μm/year was noted in patients with Stargardt disease (p=0.02), overall changes in optical gap height were not significant in the cohort as a whole. Small increases in optical gap heights of 3.3±4.8 μm/year and 1.2±1.4 μm/year were seen in patients with achromatopsia and occult macular dystrophy, respectively. The two patients with non-Stargardt cone dystrophy, P31 and P36, demonstrated a 5.6 μm/year increase and a 4.3 μm/year decrease in optical gap height, respectively. ICC between both graders was calculated using pooled data points from each eye at both initial and final visit. The ICC for both gap width and height measurements was >0.999 between graders across both eyes longitudinally.

Overall, ORT decreased at a small but significant rate of 2.5±5.1μm/year (p=0.048). No significant change was noted in CRTF; however, CRTF did decrease at a mean rate of 1.6±5.0μm/year. A mean decrease of 2.4±3.5μm/year in ORT and 4.7±5.5μm/year in CRTF was seen in patients with Stargardt disease at rates. A small decrease in ORT of 0.8±0.9μm/year and a small increase in CRTF of 0.4±0.2μm/year was observed in patients with occult macular dystrophy. In contrast, a minute increase in ORT of 0.1±0.7μm/year and in CRTF of 0.2±0.2μm/year was seen in patients with achromatopsia.

Three patients (two ABCA4 and one PITPNM3) demonstrated the development of interocular discordance in the presence of optical gap due to the collapse of the retinal layers into the gap. Comparison of changes in optical gap dimensions with changes in ORT and CRTF revealed a significant correlation (r=0.782) between CRTF and optical gap height (p=0.00012). While no significant association was found between changes in optical gap height and LogMar converted visual acuity, a potentially positive correlation (r=0.573) was observed between changes in optical gap width and visual acuity (Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Material at AJO.com).

Discussion

The optical gap phenotype has been described as a finding affecting foveal cones in a variety of progressive, heterogeneous inherited retinal dystrophies as well as a number of non-hereditary conditions. Staging of gap progression was performed in the past for specific conditions, including Stargardt disease and achromatopsia, and has been described to occur across three discrete clinical stages beginning with disruption of the EZ band, followed by the formation of a sub-foveal cavitation with hyperreflectivity of the ELM, and ending with the collapse of the remaining foveal layers into the gap.3,4,11 Prior studies have suggested that gap progression is symmetric and may be used to guide future treatments of hereditary retinal disease.4 In this study, a cohort of 36 patients with heterogeneous causes of the optical gap phenotype as identified on SD-OCT was examined, including two novel candidate etiologies of gap – mutations in PITPNM3 and RAB28. Both novel etiologies of optical gap cause cone or cone-rod dystrophy in humans and are consistent with prior suggestions that optical gap is primarily associated with cone-first retinal degenerations.

A common feature seen in the two patients with mutations in RAB28 and PITPNM3 was interocular discordance in the optical gap phenotype. This feature was found in over a third of patients in this cohort who were diagnosed with Stargardt disease, cone-, and cone-rod dystrophies but was absent in all patients diagnosed with achromatopsia or occult macular dystrophy. The ability to capture noticeable interocular discordance suggests that progression of the optical gap phenotype occurs more rapidly in patients with Stargardt disease, cone-, and cone-rod dystrophies as compared to patients with achromatopsia and occult macular dystrophy. The discordance seen in these conditions may have further implications in clinical trials that use the fellow eye as a control for the treated eye. Clinically, the finding of unilateral optical gap with the presence of atrophy in the other eye may help guide clinical diagnoses and genetic testing towards cone-first retinal degenerations.

In addition to interocular discordance, other features of the optical gap phenotype and clinical examination may be helpful in guiding clinicians towards a diagnosis (Table 2). Both the age of symptomatic onset and age at which the optical gap phenotype was observed occurred earlier in patients with Stargardt disease and achromatopsia as compared to patients with cone and macular dystrophies. A bulls-eye lesion seen on fundus examination coincident with continuous EZ disruption and hyperreflectivity of the ELM are consistent with a diagnosis of Stargardt disease likely associated with the hypomorphic c.5882G>A:p.(Gly1961Glu) variant in ABCA4. A combination of foveal hypoplasia with ELM hyperreflectivity and EZ disruption on SD-OCT was characteristic of patients with achromatopsia. In the older cohort of patients, occult macular dystrophy related optical gap was seen to have an absence of ELM hyperreflectivity, and disruption of the EZ line was intermittent. Additionally, SD-OCT was the only imaging modality capable of detecting change. Cone and macular dystrophies represented the most heterogeneous cohort of patients, and while the optical gap in this group was typically wide with intermittent EZ disruption, a higher degree of variability was noted.

Although a combination of these characteristics may be helpful in distinguishing between etiologies of optical gap, a limitation of this summary is the small sample size in this cohort. Further evaluation of larger cohorts of these patients will help validate these findings as well as demonstrate whether a correlation between optical gap dimensions and visual acuity does exist. An additional limitation of our current study is the absence of axial length evaluation to account for potential image scaling effects on transverse measurements. In this cohort, refractive error was assessed in a total of 23 of 36 patients, which showed that all but 2 patients had mild ametropia between −3D and +3D, and no patients were found to have pathologic ametropia (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Material at AJO.com). While this does not eliminate the potential effects of axial length on measurements, the presence of mostly mild refractive error in this cohort suggests that the impact may not be large. Future studies including axial length measurements will help validate these findings.

Longitudinal analysis suggested that the optical gap phenotype widens more rapidly in patients with Stargardt disease and cone dystrophies as compared to patients with achromatopsia or occult macular dystrophy. Similarly, there was an overall larger change in optical gap height in patients with Stargardt disease and cone dystrophies, which exhibit, on average, a decrease in optical gap height, as compared to patients with achromatopsia and occult macular dystrophy. We hypothesize that this decrease in optical gap height may either be a structural compensation for the increases in width as the gap is stretched or a morphological change that mirrors retinal thinning as a result of disease progression.

Measurements of retinal thickness demonstrated a decrease in both CRTF and ORT in patients with Stargardt disease and cone dystrophies and a small increase in patients with achromatopsia. In patients with occult macular dystrophy, a small increase in CRTF and decrease in ORT were observed. Overall, measurements of CRTF were significantly correlated with the height of the optical gap (p<0.001), but measurements of ORT were not. The change in retinal thickness in our patients with Stargardt disease, achromatopsia, and cone dystrophies are consistent with prior reports, and the observed correlation supports the hypothesis that the morphology of the optical gap in IRDs mirrors changes in the retinal architecture as disease progresses.13–16

Further longitudinal studies are required to validate the changes in optical gap height, ORT, and CRTF especially in patients with achromatopsia and occult macular dystrophy, as the calculated annual changes in height were similar to the axial resolution of the Spectralis HRA+OCT at 3.5 μm/year.17 The slow change over time in these patients suggests that optical gap would be a poor outcome measurement in the ongoing clinical trials and future treatment of these conditions. Additional limitations of this analysis include the small sample size and absence of axial length measurements, and as such, further evaluation of larger cohorts of these patients with axial length scaling are warranted.

While our study provides characterization of changes in heterogeneous cases of optical gap over time, both the pathophysiology of this phenotype and the reason why certain patients develop this gap while others do not remain unclear. We hypothesize that in many patients, these optical gaps may not be observed as patients will present after the gap has collapsed and central macular atrophy has taken place. Within our retrospective analysis of 746 patients, a total of 92 patients with the same monogenic causes of IRD without optical gap were identified. Among them 76, were found to have macular atrophy at initial presentation while the remaining 16 had signs of EZ disruption without cavity formation. It is possible that over time, these 16 patients will go on to develop a cavitation, and longitudinal follow-up will be informative. Notably, a genotype-phenotype correlation, which has been previously noted, was seen as the majority of patients with Stargardt disease and optical gaps were found to have the c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu variant in ABCA4.4 Further studies are warranted to demonstrate why this specific variant leads to gap formation.

Future studies are also needed to elucidate the contents of the optical gap. In many of the subjects in this cohort as well as in previous studies, SD-OCT images revealed the presence of debris within the optical gap which is seen loosely adherent to the ELM or the RPE.3,4 We hypothesize that the debris is composed of the remnants of cone photoreceptor inner and outer segments, and the hyperreflective dots may be microglia, which could facilitate the removal of the debris.18 The non-reflective portion of the gap may be filled by water, lactate, glucose, calcium, acyl carnitines and other substrates and byproducts of cone metabolism.19,20

Review

When the optical gap SD-OCT phenotype was elaborated upon by Leng et al. in 2012, the differential diagnosis of this phenotype was considered to include Stargardt disease, achromatopsia, and autosomal dominant cone dystrophies due to cyclase deficiencies.2 Since then, a variety of other etiologies have been described in the literature, suggesting that the differential diagnosis of optical gap includes a larger than previously thought array of heterogeneous inherited retinal dystrophies, chemical toxicities, and environmental or occupation-associated injuries. In this study alone, the authors describe a cohort of 36 patients with optical gap who possess mutations in ABCA4, CNGA3, CNGB3, PDE6C, AFT6, RP1L1, GUCY2D, GUCA1A, PRPH2, as well as two novel candidate etiologies – mutations in RAB28 and PITPNM3. In addition to the conditions described in this study, a review of the literature for conditions causing “foveal cavitation”, “optical gap”, “disruption of the IS/OS junction”, or “disruption of the EZ line” was performed to broaden the currently understood causes of optical gap.

Achromatopsia

Achromatopsia is a heterogeneous autosomal recessive retinal disorder that has frequently been associated with optical gap in the literature.4,5,21–29 Patients typically present with color blindness, photophobia, nystagmus, and decreased visual acuity. Genetic etiologies of achromatopsia include mutations in CNGA3, CNGB3, GNAT2, PDE6C, PDE6H, and ATF6 genes. The optical gap phenotype has been observed in patients with all of these genetic etiologies except for PDE6H, which represents a minority population of total patients with achromatopsia.30 Further evaluation of these patients will help elucidate the presence or absence of this phenotype in association with this gene. Thiadens et al. first suggested the progressive nature of achromatopsia in 2010 using SD-OCT to monitor retinal thinning.21 In 2014, Greenberg et al. corroborated this finding using a five-part staging system to classify disease progression.4

Blue cone monochromacy

Blue cone monochromatism, or “atypical achromatopsia”, is an X-linked stationary cone disorder that results in loss of long-wavelength and medium-wavelength cone photoreceptors, leading to marked loss of color vision in the red-green spectrum.31 Remaining color vision is typically derived from residual short-wavelength cone photoreceptors.31 Similar to patients with complete achromatopsia, patients with blue cone monochromatism present with decreased color vision and visual acuity, nystagmus, and photophobia.31 The optical gap phenotype in patients with blue cone monochromacy has been described in patients with mutations in OPN1LW and OPN1MW, as reported by Barthelmes et al.1,32,33

Stargardt and Stargardt-like Disease

Optical gap in Stargardt disease was first described by Cella et al. in association with the c.5882G>A:p.Gly1961Glu variant in the ABCA4 gene, and later by Palejwala et al in association with the ELOVL4-mediated autosomal dominant Stargardt-like retinopathy.15,34 Stargardt disease is a progressive, early onset retinal dystrophy leading to a loss of central vision and a decrease in visual acuity. Given the genotype and phenotype heterogeneity seen in patients with Stargardt disease, genotype-phenotype correlation of optical gap with identified variants is valuable in understanding disease progression and prognosis.2,15,34–36 Nõupuu et al. describe the progressive nature of optical gap seen in Stargardt disease in 15 patients, 14 of whom possess the p.Gly1961Glu variant, and suggest a three-step staging system for the gap in patients with Stargardt disease.3 Stage 1 disease was characterized as subfoveal EZ line disruption in the absence of a visible cavity. Stage 2 disease was described as the total absence of the EZ line and formation of the empty subfoveal space. Finally, Stage 3 disease was characterized by collapse of neurosensory retina into the cavity.

Occult Macular Dystrophy

Occult macular dystrophy and associated optical gap was first described on SD-OCT by Park et al.37–40 Occult macular dystrophy is a dominant inherited retinal dystrophy caused by mutations in the RP1L1 gene. Clinically, patients present with decreased visual acuity but otherwise normal fundus autofluorescence and ffERG findings. A report of 46 patients with this dystrophy suggests that the incidence of optical gap findings is particularly high, with a described incidence rate of 63% in patients.38

Cone & Cone-Rod Dystrophies

Among the many heterogeneous causes of cone and cone-rod dystrophies, the literature specifically describes cases of KCNV2-, GUCY2D-, GUCA1A-, PRPH2-, POC1B-, and SCA7- associated disease with optical gap phenotypes on SD-OCT imaging.41–46 Review of other etiologies of cone and cone-rod dystrophies, including those associated with mutations in CACNA2D4, AIPL1, CRX, PROM1, RAX2, RIMS1, UNC119, ADAM9, C21ORF2, C8ORF37, CDHR1, CERKL, POC1B, RPGRIP1, SEMA4A, TTLL5, CACNA1F, and RPGR did not provide any cases with the optical gap phenotype on SD-OCT imaging. Leng et al. suggest that optical gap is a phenotype most commonly associated with cone and cone-rod dystrophies.2 While a number of etiologies of cone-first retinal degenerations have been shown to produce an optical gap phenotype, a larger number have not yet been shown to have this association. Further evaluation of patients with cone and cone-rod dystrophies on SD-OCT imaging may help strengthen the association of this phenotype with these conditions.

Non-hereditary Optical Gap

Pharmacologic etiologies of optical gap discussed in the literature include tamoxifen-induced retinopathy, as first described by Doshi et al. in 3 patients with foveal cavitation, as well as poppers maculopathy in a case series of 7 patients who developed optical gap after the inhalation of poppers.47–51 Reports regarding the change over time in these conditions is limited, but in patients with poppers maculopathy, cases of resolution of the EZ-line disruption have been described.50

Non-hereditary causes of optical gap include solar retinopathy, arc welding maculopathy, juxtafoveal macular telangiectasias, microholes from vitreomacular traction, central serous chorioretinopathy, and laser pointer retinopathy.52–56 The pathophysiology of the optical gap phenotype in these conditions has been attributed to photoradiation of melanosomes in the RPE and consequent necrosis of RPE and photoreceptors outer segment damage.52 Environmental or occupation-associated injuries are typically noted to recover over time, but with extensive or recurrent injury, damage may be irreversible.

Summary

The differential diagnosis of optical gap is continually being expanded. Currently, this includes a wide variety of cone and cone-rod dystrophies, achromatopsia, and pharmacologic etiologies or exposure injuries. In this study, the authors describe a large cohort of patients seen in their practice with the gap phenotype, including two patients with novel candidate etiologies – PITPNM3 and RAB28-mediated cone-rod dystrophies. Longitudinal progression of the optical gap width is described in this study for a total of 19 patients, suggesting that phenotype progression is more rapid in cone-first retinal degenerations and much slower in patients with achromatopsia and occult macular dystrophy. Interocular discordance was also a common finding in patients with cone dystrophies, with patients experiencing progression from the gap phenotype to collapse of the neurosensory retina into the gap at different times for each eye. These findings have implications in the understanding of the optical gap phenotype. In clinical practice, the identification of an optical gap on SD-OCT should direct the differential diagnosis towards cone-first retinal degenerations or non-hereditary causes of disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The causes of the optical gap phenotype are continually increasing and need to be characterized.

The rate of optical gap widening is progressive and differs across etiologies of the phenotype.

Changes in optical gap size do not necessarily correlate with changes in visual acuity.

Changes in optical gap height correlate well with changes in central foveal retinal thickness.

Interocular discordance is a feature of optical gap caused by Stargardt disease or cone dystrophy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS/DISCLOSURES

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The Jonas Children’s Vision Care and Bernard & Shirlee Brown Glaucoma Laboratory are supported by the National Institute of Health 5P30CA013696, U01EY030580, U54OD020351, R24EY028758, R24EY027285, 5P30EY019007, R01EY018213, R01EY024698, R01EY024091, R01EY026682, R01EY009076, R21AG050437, the Schneeweiss Stem Cell Fund, New York State [SDHDOH01-C32590GG-3450000 ], the Foundation Fighting Blindness New York Regional Research Center Grant [PPA-1218-0751-COLU], Nancy & Kobi Karp, the Crowley Family Funds, The Rosenbaum Family Foundation, Alcon Research Institute, the Gebroe Family Foundation, the Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) Physician-Scientist Award, unrestricted funds from RPB, New York, NY, USA. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Please add R01EY009076 to Support

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that there are no financial disclosures.

Supplemental Material available at AJO.com

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barthelmes D, Sutter FK, Kurz-Levin MM, et al. Quantitative analysis of OCT characteristics in patients with achromatopsia and blue-cone monochromatism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):1161–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leng T, Marmor MF, Kellner U, et al. Foveal cavitation as an optical coherence tomography finding in central cone dysfunction. Retina. 2012; 32: 1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nõupuu K, Lee W, Zernant J, Tsang SH, Allikmets R. Structural and genetic assessment of the ABCA4-associated optical gap phenotype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014; 55(11):7217–7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg JP, Sherman J, Zweifel SA, Chen RW, Duncker T, Kohl S, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography staging and autofluorescence imaging in achromatopsia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:437–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Purohit R, Sheth V, McLean RJ, Kohl S, Leroy BP, Sundaram V, Michaelides M, Proudlock FA, Gottlob I: Retinal Development in Infants and Young Children with Achromatopsia. Ophthalmology 2015, 122(10):2145–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCulloch DL, Marmor MF, Brigell MG, et al. ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Documenta Ophthalmologica. 2015;130(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood DC, Lin CE, Lazow MA, Locke KG, Zhang X, Birch DG. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(5):2328–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roosing S, Rohrschneider K, Beryozkin A, et al. Mutations in RAB28, encoding a farnesylated small GTPase, are associated with autosomal-recessive cone-rod dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(1):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köhn L, Kohl S, Bowne SJ, et al. PITPNM3 is an uncommon cause of cone and cone-rod dystrophies. Ophthalmic Genet. 2010;31(3):139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohn L, Kadzhaev K, Burstedt MS, et al. Mutation in the PYK2-binding domain of PITPNM3 causes autosomal dominant cone dystrophy (CORD5) in two Swedish families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15(6):664–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke TR, Yzer S, Zernant J, Smith RT, Tsang SH, Allikmets R: Abnormality in the external limiting membrane in early Stargardt disease. Ophthalmic Genet 2013, 34(1–2):75–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan KN, Kasilian M, Mahroo OAR, et al. Early Patterns of Macular Degeneration in ABCA4-Associated Retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(5):735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirji N, Georgiou M, Kalitzeos A, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Retinal Structure in Achromatopsia Patients With Long-Term Follow-up. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(15):5735–5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho SC, Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM. Morphologic characteristics of the outer retina in cone dystrophy on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27(1):19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim BJ, Ibrahim MA, Goldberg MF. Use of spectral domain-optical coherence tomography to visualize photoreceptor abnormalities in cone-rod dystrophy 6. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2011;5(1):56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella W, Greenstein VC, Zernant-Rajang J, Smith TR, Barile G, Allikmets R, Tsang SH: G1961E mutant allele in the Stargardt disease gene ABCA4 causes bull’s eye maculopathy. Exp Eye Res 2009, 89(1):16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heidelberg Enginneering. Spectralis hardware operating instructions. Technical Specifications. 2007:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coscas G, De Benedetto U, Coscas F, et al. Hyperreflective dots: a new spectral-domain optical coherence tomography entity for follow-up and prognosis in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologica. 2013;229(1):32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanow MA, Giarmarco MM, Jankowski CS, et al. Biochemical adaptations of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium support a metabolic ecosystem in the vertebrate eye. Elife. 2017;6:e28899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giarmarco MM, Cleghorn WM, Sloat SR, Hurley JB, Brockerhoff SE. Mitochondria Maintain Distinct Ca2+ Pools in Cone Photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2017;37(8):2061–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiadens AA, Somervuo V, van den Born LI, et al. Progressive Loss of Cones in Achromatopsia: An Imaging Study Using Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51(11):5952–5957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahim AT, Khan NW, Zahid S, Schachar IH, Branham K, Kohl S, Wissinger B, Elner VM, Heckenlively JR, Jayasundera T: Diagnostic fundus autofluorescence patterns in achromatopsia. Am J Ophthalmol 2013, 156(6):1211–1219 e1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genead MA, Fishman GA, Rha J, Dubis AM, Bonci DM, Dubra A, Stone EM, Neitz M, Carroll J: Photoreceptor structure and function in patients with congenital achromatopsia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011, 52(10):7298–7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohl S, Zobor D, Chiang WC, Weisschuh N, Staller J, Gonzalez Menendez I, Chang S, Beck SC, Garcia Garrido M, Sothilingam V et al. : Mutations in the unfolded protein response regulator ATF6 cause the cone dysfunction disorder achromatopsia. Nat Genet 2015, 47(7):757–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaram V, Wilde C, Aboshiha J, Cowing J, Han C, Langlo CS, Chana R, Davidson AE, Sergouniotis PI, Bainbridge JW et al. : Retinal structure and function in achromatopsia: implications for gene therapy. Ophthalmology 2014, 121(1):234–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiadens AA, den Hollander AI, Roosing S, Nabuurs SB, Zekveld-Vroon RC, Collin RW,De Baere E, Koenekoop RK, van Schooneveld MJ, Strom TM et al. : Homozygosity mapping reveals PDE6C mutations in patients with early-onset cone photoreceptor disorders. Am J Hum Genet 2009, 85(2):240–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas MG, McLean RJ, Kohl S, Sheth V, Gottlob I: Early signs of longitudinal progressive cone photoreceptor degeneration in achromatopsia. Br J Ophthalmol 2012, 96(9):1232–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueno S, Nakanishi A, Kominami T, Ito Y, Hayashi T, Yoshitake K, Kawamura Y, Tsunoda K, Iwata T, Terasaki H: In vivo imaging of a cone mosaic in a patient with achromatopsia associated with a GNAT2 variant. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2017, 61(1):92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zobor D, Werner A, Stanzial F, Benedicenti F, Rudolph G, Kellner U, Hamel C, Andreasson S, Zobor G, Strasser T et al. : The Clinical Phenotype of CNGA3-Related Achromatopsia: Pretreatment Characterization in Preparation of a Gene Replacement Therapy Trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58(2):821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl S, Coppieters F, Meire F, Schaich S, Roosing S, Brennenstuhl C, Bolz S, van Genderen MM, Riemslag FC, European Retinal Disease C et al. : A nonsense mutation in PDE6H causes autosomal-recessive incomplete achromatopsia. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 91(3):527–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner JC, Michaelides M, Holder GE, et al. Blue cone monochromacy: causative mutations and associated phenotypes. Mol Vis. 2009;15:876–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll J, Dubra A, Gardner JC, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Cooper RF, Dubis AM, Nordgren R, Genead M, Connor TB Jr., Stepien KE et al. : The effect of cone opsin mutations on retinal structure and the integrity of the photoreceptor mosaic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53(13):8006–8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patterson EJ, Kalitzeos A, Kasilian M, et al. Residual Cone Structure in Patients With X-Linked Cone Opsin Mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(10):4238–4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palejwala NV, Gale MJ, Clark RF, Schlechter C, Weleber RG, Pennesi ME: Insights into Autosomal Dominant Stargardt-Like Macular Dystrophy through Multimodality Diagnostic Imaging. Retina 2016, 36(1):119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritter M, Zotter S, Schmidt WM, Bittner RE, Deak GG, Pircher M, Sacu S, Hitzenberger CK, Schmidt-Erfurth UM, Macula Study Group V: Characterization of stargardt disease using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography and fundus autofluorescence imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54(9):6416–6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sisk RA, Leng T: Multimodal imaging and multifocal electroretinography demonstrate autosomal recessive Stargardt disease may present like occult macular dystrophy. Retina 2014, 34(8):1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park SJ, Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM, Chung H: Morphologic photoreceptor abnormality in occult macular dystrophy on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010, 51(7):3673–3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn SJ, Ahn J, Park KH, Woo SJ: Multimodal imaging of occult macular dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013, 131(7):880–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato Y, Hanazono G, Fujinami K, Hatase T, Kawamura Y, Iwata T, Miyake Y, Tsunoda K: Parafoveal Photoreceptor Abnormalities in Asymptomatic Patients With RP1L1 Mutations in Families With Occult Macular Dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58(14):6020–6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saffra N, Seidman CJ, Rakhamimov A, Tsang SH: ERG and OCT findings of a patient with a clinical diagnosis of occult macular dystrophy in a patient of Ashkenazi Jewish descent associated with a novel mutation in the gene encoding RP1L1. BMJ Case Rep 2017, 2017:bcr2016218364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sergouniotis PI, Holder GE, Robson AG, Michaelides M, Webster AR, Moore AT: High-resolution optical coherence tomography imaging in KCNV2 retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2012, 96(2):213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee R, Robson AG, Holder GE, Stockman A, Egan CA, Moore AT, Webster AR: A detailed phenotypic description of autosomal dominant cone dystrophy due to a de novo mutation in the GUCY2D gene. Eye (Lond) 2014, 28(4):481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manes G, Mamouni S, Herald E, Richard AC, Senechal A, Aouad K, Bocquet B, Meunier I, Hamel CP: Cone dystrophy or macular dystrophy associated with novel autosomal dominant GUCA1A mutations. Mol Vis 2017, 23:198–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maertz J, Gloeckle N, Nentwich MM, Rudolph G: [Genotype-phenotype correlation in patients with PRPH2-mutations]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2015, 232(3):266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roosing S, Lamers IJ, de Vrieze E, van den Born LI, Lambertus S, Arts HH, Group PBS, Peters TA, Hoyng CB, Kremer H et al. : Disruption of the basal body protein POC1B results in autosomal-recessive cone-rod dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2014, 95(2):131–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watkins WM, Schoenberger SD, Lavin P, Agarwal A: Circumscribed outer foveolar defects in spinocerebellar ataxia type 7. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013, 7(3):294–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doshi RR, Fortun JA, Kim BT, Dubovy SR, Rosenfeld PJ: Pseudocystic foveal cavitation in tamoxifen retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2014, 157(6):1291–1298 e1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee S, Kim H-A & Yoon YH, Optical Coherence Tomography Angiographic Findings of Tamoxifen Retinopathy: Similarity with Macular Telangiectasia Type 2, Ophthalmology Retina (2019), doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, Bhatt PR, Mathews JP, Sahni J, Haslett R, McKibbin M: Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of ‘poppers maculopathy’. Eye (Lond) 2012, 26(11):1479–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR: ‘Poppers maculopathy’--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond) 2012, 26(6):888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luis J, Virdi M, Nabili S: Poppers retinopathy. BMJ Case Rep 2016, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dirani A, Chelala E, Fadlallah A, Antonios R, Cherfan G: Bilateral macular injury from a green laser pointer. Clin Ophthalmol 2013, 7:2127–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, Zheng A, Nie H, Bhavsar KV, Xu Y, Sliney DH, Trokel SL, Tsang SH: Laser-Induced Photic Injury Phenocopies Macular Dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet 2016, 37(1):59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birtel J, Harmening WM, Krohne TU, Holz FG, Charbel Issa P, Herrmann P: Retinal Injury Following Laser Pointer Exposure. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017, 114(49):831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jain A, Desai RU, Charalel RA, Quiram P, Yannuzzi L, Sarraf D: Solar retinopathy: comparison of optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography (FA). Retina 2009, 29(9):1340–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang C, Dang G, Zhao T, Wang D, Su Y, Qu Y: Predictive value of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography features in assessment of visual prognosis in eyes with acute welding arc maculopathy. Int Ophthalmol 2019, 39(5):1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.