Abstract

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS), a rare genetic disorder, affects multiple organs and classically presents with the triad of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (FD), skin hyperpigmentation (café-au-lait spots) and precocious puberty. Diagnosis occurs when patients manifest at least two of these three symptoms. We describe a 4-year-old girl who was admitted to our hospital due to recurrent vaginal bleeding, initially diagnosed as precocious puberty. On brain MRI, abnormalities in the maxillary and occipital bones were compatible with FD. Clinical examination after craniofacial bone lesions and clinical signs indicated MAS revealed abnormally pigmented macules on the neck and back, which were initially overlooked. No abnormal hormone tests were observed. Precocious puberty is the most common MAS-associated symptom that results in the admission to the hospital, whereas the clinical manifestation of FD in the first years of life is usually equivocal and probably has not been discovered by parents. Thus, comprehensive medical examinations are necessary to obtain a prompt and proper diagnosis.

Keywords: radiology, radiology (diagnostics), immunology, endocrinology

Background

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS), first described by McCune and Albright in 1937, is a rare genetic disorder associated with the activating mutation in the guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha-stimulating (GNAS) gene that affects multiple organs.1 2 The estimated prevalence of MAS is 1 in 1 000 000–1 in 100 000 population, according to various studies.3–5 The diagnostic criteria for MAS includes at least two of three abnormal clinical manifestations: fibrous dysplasia (FD), café-au-lait macules and dysfunction of the endocrine system which typically shows as precocious puberty.2 3 However, the clinical symptoms of MAS can be multiform and can involve the typical triad or present with unique symptoms.3 Precocious vaginal bleeding can be the onset sign of MAS, as in the case of our patient, which has to be correctly interpreted through a differential diagnosis among causes of precocious vaginal bleeding and investigating other elements relevant to the diagnosis of MAS. Because of the wide range of possible clinical manifestations, a systematic and careful investigation is necessary to obtain a proper diagnosis and ensure appropriate management.

Case presentation

Our patient, a 4-year-old girl, was referred to the paediatric faculty with the main complaints of recurrent vaginal bleeding during the last 3 months. Neither genital injury nor other notable symptoms reported. Aside the symptom of vaginal bleeding, the examination has not revealed any visible secondary sex characteristics. She presented with normal mental development. She measured 109 cm in height and weighed 17 kg, corresponding to +1.4 SDS (Standard Deviation Score) and +0.4 SDS according to WHO growth chart, respectively.6

In the past, the patient had a history of vaginal bleeding once at the age of 2 years, and normal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) levels were observed at that time, and no treatment was given. No remarkable family history was detected.

Investigations

Laboratory tests showed normal serum LH (<0.3 mIU/mL), FSH (1.16 mIU/mL) and estradiol (<5 pg/mL) levels.

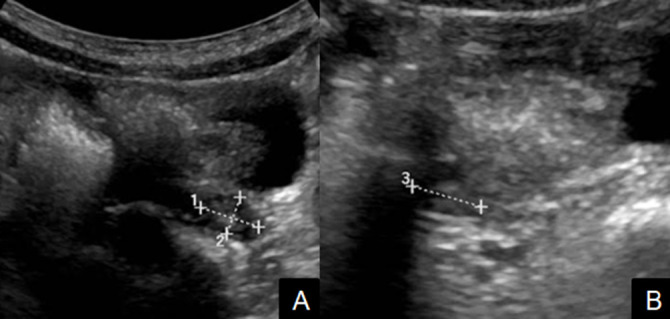

Ultrasound result of the thyroid were normal. Transabdominal ultrasound showed the morphology and volume of uterine and ovaries were in normal limits correlated to age, according to Haber and Badouraki and no ovarian mass was seen (figure 1).7 8 Hand radiograph revealed that the child’s skeleton was compatible with age of 5 years 9 months according to Greulich and Pyle method, which meant her bone maturity advanced about 2 years above chronological age (figure 2). The stature equal to +1.4 SDS and the bone age about 2 years older than the chronological age, could be the result of an acceleration of statural growth due to precocious puberty.

Figure 1.

Transabdominal ultrasound of bilateral ovaries. (A) The left ovary, (B) the right ovary: normal limits in size correlated to age, according to Haber and Badouraki without ovarian mass seen.

Figure 2.

X ray of the left hand: performed to estimate bone age and showed her bone age was compatible with age of 5 years 9 months according to Greulich and Pyle method which means the bone maturation advanced about 2 years above chronological age.

The patient was transferred to the department of radiology to undergo brain MRI, with an initial diagnosis of precocious puberty. On brain MRI, neither intracranial nor hypothalamic–pituitary abnormalities were observed. However, MRI revealed craniofacial bone lesions with diffuse hypertrophy of the maxillary, temporal and occipital bones, and the sphenoid bone on the left side showed intermediate signals on both T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted sequences (figure 3). These lesions were consistent with the sclerotic appearance observed in FD.

Figure 3.

MRI of the patient. (A) Sagittal T2-weighted (T2W) image showed the normal size, shape and signal of the pituitary. (B–D) The expansion of the maxillary, temporal, occipital and sphenoid bones, showing intermediate signals consistent with lesions on both T1-weighted and T2W sequences.

Based on the symptoms of recurrent vaginal bleeding and craniofacial FD, we suspected MAS and searched for skin pigmentation, which was initially overlooked. Café-au-lait spots with irregular borders were identified on the back of the trunk and neck (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Café-au-lait spots on the back of the trunk and neck. These spots featured irregular, Jagged borders. With respect to the midline of the body, these spots followed the developmental lines of Blaschko (black arrow).

Differential diagnosis

Due to the symptoms of recurrent vaginal bleeding, café-au-lait spots on the back of the trunk and neck skin, and imaging features consistent with FD, our patient presented with the typical triad of MAS symptoms.

Despite of advanced bone age, normal values of serum LH, FSH, estradiol and normal morphology of primary and secondary reproductive organs allowed to rule out central precocious puberty or oestrogen dysfunction owing to ovarian tumour.

Treatment

The patient had normal hormone levels, and no abnormalities were observed in the intracranial or hypothalamic–pituitary regions; therefore, no medications or surgical treatments were administered.

Outcome and follow-up

She will receive follow-up visits every 6 months to re-evaluate the potential clinical symptoms of premature puberty and measure the levels of endocrine hormones. Physical development and skeletal maturity are also examined periodically to mornitor advanced pubertal development. Besides, the reassessment of craniofacial FD through clinical examination and CT or MRI study is carried out simultaneously.

Discussion

MAS is a spodaric genetic disorder caused by a postzygotic somatic mutation in the GNAS gene, which affects the bones, skin and certain endocrine organs. These mutations appear during the postzygotic stage; therefore, some cells express wild-type GNAS, and others express the mutant GNAS, resulting in mosaicism.9 GNAS plays a pivotal role in the production of several proteins involved in hormone regulation through cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Proteins encoded by the mutant GNAS gene stimulate the abnormally constant activity of cAMP, leading to the overproduction of hormones that cause the underlying symptoms of MAS.9

Vaginal bleeding can be one of the onset symptoms in prepubertal girls that occurs in congenital conditions such as MAS and acquired abnormalities such as primary hypothyroidism or hormone dysfunction associated with ovarian lesions. Precocious puberty is the most common endocrinopathy described in MAS, often referred to as gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty (GIPP). In female with MAS, vaginal bleeding is usually the first sign of peripheral precocious puberty, which may be isolated or associated with mammary gland development and increased growth and bone maturation.10 The presence of vaginal bleeding accompanied with significant acceleration of bone maturation and rapid growth of stature in our patient likely suggested premature puberty. To rule out central precocious puberty, serum LH level and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue stimulation test are the most reliable laboratory tests.11 The value of LH lower than 0.3mIU/mL and the absence of secondary sexual characteristics in our case allows less targeting on central premature puberty. Therefore, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue stimulation test has not been performed. Due to the morphology and dimension of both ovaries and uterus on the ultrasound was revealed normal, episodic ovarian hypersecretion was not taken into consideration. Other endocrinopathies include hyperthyroidism, excessive growth hormone, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperprolactaemia and hypercortisolism.12 Endocrine hyperactivity is the second most common feature of MAS (after café-au-lait spots). The abnormal proteins encoded by the mutated GNAS gene cause the over-activity of cAMP, which leads to the increased production of several endocrinal tissues.9

Previous studies have revealed that café-au-lait pigmentation typically appears at birth or shortly thereafter.4 12 13 Although these melanotic macules are the most common sign of MAS, identified in approximately 60% of all MAS cases according to previous reports,4 13 14 they are often overlooked and are not the primary presenting sign. Unique café-au-lait spots are common in the general population, appearing in approximately 0.3%–2.7% of newborns and increasing to up to 30% of school children.14 However, the presence of multiple hyperpigmented spots may indicate a systemic disorder. Typical pigmented spots associated with MAS display as light or dark brown in colour, with irregular and jagged borders, often described as resembling the ‘coast of Maine,’ and commonly appearing ipsilateral to identified bone lesions. The development of this pigmentation typically respects the midline of the body and follows the developmental lines of Blaschko.9 15 In our case, the patient presented with characteristic café-au-lait spots, including jagged ‘coast of Maine’ borders and development on both sides, preserving the midline. Skin lesions in MAS must be distinguished from the skin hyperpigmented patches that occur in neurofibromatosis 1, which are typically fewer in number, darker and smooth-bordered, resembling the ‘coast of California,’ and present on both sides of the body.3

The most prominent skeletal abnormality associated with MAS is FD, which is a developmental and tumour-like condition that manifests as the replacement of normal bone with the excessive proliferation of cellular fibrous connective tissue intermixed with irregular bony trabeculae. FD is associated with an increased risk of pathologic fractures, skeletal deformities, functional impairments and pain.3 FD is typically classified into two groups: monostotic (involving one bone) and polyostotic (involving multiple bones). Bony lesions are predominately identified on one side of the body. In our case, most of the cranial bone lesions were found on the left side, including the left maxillary, left temporal and left occipital bones. MAS onset typically presents in craniofacial bones at an early age. Ninety per cent of craniofacial bone abnormalities present by 3.4 years of age, according to Leet et al.16 Common clinical signs of craniofacial FD include painless lumps and facial asymmetry. In later years, the FD involvement can occur in the extremities and the axial skeleton.16 The appearance of FD in radiographs and CT imaging consists of the presence of ground glass opacities, a homogeneously sclerotic or cystic appearance, well-defined borders and the expansion of bones, with intact overlying bones and endosteal scalloping. Although MRI is not predominantly used to differentiate FD from other entities, certain signs of FD can be observed on MRI, including the expansion of the bone, typically associated with an intermediate signal on T1W, and lesions can range from high to low signal on fluid-sensitive sequences, depending on the amount of bone within the lesion. The degree of contrast enhancement depends on the active status of bony lesions.

To sum up, MAS syndrome is a rare disease associated with activating mutations in the GNAS gene; however, this is one of the etiologies of precocious puberty. MAS is diagnosed by at least two symptoms of the triad including GIPP, hyperpigmented spots and FD. Sometimes MAS presents with a single symptom within the triad that is a challenge for physicians to give accurate diagnosis and prognosis. A meticulous clinical examination to look for café-au-lait macules and signs of FD is important in patients with recurrent vaginal bleeding to suspect the diagnosis of MAS and correctly direct the diagnostic workup.

Learning points.

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) is a rare disease associated with activating mutations in the guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha-stimulating gene.

MAS is predominantly characterised by gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty, hyperpigmented spots and fibrous dysplasia.

Vaginal bleeding, a symptom of precocious puberty, can be the onset of MAS.

Although MAS with the typical triad is not difficult to diagnose, cases that lack one or more typical symptoms may challenge diagnosis. A meticulous clinical examination and long-term follow-up are recommended.

Café-au-lait macules are a common sign that could be overlooked. Neurofibromatosis 1, cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphataemia syndrome and various fibro-osseous skeletal lesions that share features with MAS must be distinguished from MAS.

Footnotes

NVD and NMD contributed equally.

Contributors: NVD and NMD contributed equally to this article as cofirst authors. NVD and NMD were responsible for writing and drafting the manuscript. NMD and VKN were responsible for reviewing, guiding, and editing the final draft. VKN and NVA were responsible for interpreting X-ray and MRI.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.McCune DJ. Osteitis fibrosa cystica: the case of a nine-year-old girl who also exhibits precocious puberty, multiple pigmentation of the skin and hyperthyroidism. Am J Child 1936;52:743–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright F, BUTLER AM, Hampton AO, et al. Syndrome characterized by osteitis fibrosa disseminata, areas of pigmentation and endocrine dysfunction, with precocious puberty in females. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1937;216:727–46. 10.1056/NEJM193704292161701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce AM, Florenzano P, de Castro LF. Fibrous Dysplasia/McCune-Albright syndrome. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK274564/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumitrescu CE, Collins MT. Mccune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:12. 10.1186/1750-1172-3-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jibbe N, Jibbe A, Rajpara A. McCune Albright syndrome. Kans J Med 2020;13:49–50. 10.17161/kjm.v13i1.13491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age ; methods and development. Geneva: WHO Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haber HP, Mayer EI. Ultrasound evaluation of uterine and ovarian size from birth to puberty. Pediatr Radiol 1994;24:11–13. 10.1007/BF02017650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badouraki M, Christoforidis A, Economou I, et al. Sonographic assessment of uterine and ovarian development in normal girls aged 1 to 12 years. J Clin Ultrasound 2008;36:539–44. 10.1002/jcu.20522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Happle R. The McCune-Albright syndrome: a lethal gene surviving by mosaicism. Clin Genet 1986;29:321–4. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1986.tb01261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corica D, Aversa T, Pepe G, et al. Peculiarities of precocious puberty in boys and girls with McCune-Albright syndrome. Front Endocrinol 2018;9:337. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein DA, Emerick JE, Sylvester JE, et al. Disorders of puberty: an approach to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2017;96:590–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Völkl TMK, Dörr HG. Mccune-Albright syndrome: clinical picture and natural history in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2006;19 Suppl 2:551–9. 10.1515/JPEM.2006.19.S2.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth JG, Esterly NB. Mccune-Albright syndrome with multiple bilateral café Au Lait spots. Pediatr Dermatol 1991;8:35–9. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landau M, Krafchik BR. The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40:877–90. 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70075-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung A-J, Soskin S, Paris F, et al. Syndrome de McCune-Albright révélé PAR des taches café-au-lait blaschko-linéaires Du DOS. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie 2016;143:21–6. 10.1016/j.annder.2015.10.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leet AI, Chebli C, Kushner H, et al. Fracture incidence in polyostotic fibrous dysplasia and the McCune-Albright syndrome. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:571–7. 10.1359/JBMR.0301262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]