Abstract

Abdominal pain is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED) and the differential diagnoses is broad. Intussusception is more common in children, with only 5% of cases reported in adults. 80%–90% of adult intussusception is due to a well-defined lesion resulting in a lead point, whereas in children, most cases are idiopathic. The most common site of involvement in adults is the small bowel. Treatment in adults is generally operative management whereas in children, a more conservative approach is taken with non-operative reduction. We present a case of a 54-year-old woman who presented to our ED with severe abdominal pain and vomiting. CT of the abdomen revealed a jejunojejunal intussusception. The patient had an urgent laparoscopy and small bowel resection of the intussusception segment was performed. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen found no pathologic lead point and, therefore, the intussusception was determined to be idiopathic.

Keywords: emergency medicine, gastroenterology, small intestine, radiology, surgery

Background

The word ‘intussusception’ originates from modern Latin ‘intus’ (meaning within) and ‘suscipere’ (meaning to take up).1 It is the telescoping of the proximal portion of bowel (the intussusceptum) into the lumen of the contiguous bowel (the intussuscipiens).2

It is a rare diagnosis accounting for 0.003%–0.02% of all hospital admissions.3 4 Approximately 5% of all intussusception cases occur in adults and they cause up to 5% of all adult bowel obstruction cases.5 6 Initially described in the 17th century by Barbette of Amsterdam, in the 18th century, John Hunter described something similar except named it ‘introsussuception’.7 8

Diagnosis of adult intussusception is often tricky compared with children as clinical symptoms and signs are variable and non-specific. The onset is gradual, with most cases being subacute or chronic.3 6 9 Abdominal pain is the most common symptom, seen in more than 70% of cases, others being nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal distension.3 4 8 The classical clinical triad of abdominal pain, abdominal mass and red currant jelly stool is rarely present in adults.6 9 10 Weight loss and constipation could be present and may suggest an underlying malignancy.11

In contrast to children, around 90% of adult intussusception cases have a well defined, organic lesion resulting in a lead point.3 6 12 This is located in the small bowel in the majority of cases.

Diagnosis is usually made intra-operatively in up to 50% cases,4 although contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen is sufficiently characteristic to make a diagnosis based on radiological appearances.6 8 13

Case presentation

A 54-year-old woman presented to our emergency department (ED) with severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. The pain was gradual in onset, located in the periumblical and epigastric area, and with no radiation. She denied any other symptoms.

She had multiple surgeries in the past including caesarean sections, the last one being 17 years ago, cholecystectomy 8 years ago, gastric bypass surgery 6 years ago, appendicectomy 3 years ago and umblical hernia repair 2 years ago.

She has a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease, controlled with medication. On our initial assessment, she was in severe abdominal pain with a pain score of 8/10 requiring frequent doses of analgesia which reduced her pain score to 4/10. Her vital signs were within normal limits except high blood pressure.

Systemic examination was within normal limits with the exception of the abdomen which was soft, non-distended with epigastric and periumblical tenderness. There were no palpable hernias. The abdomen was reassessed after analgesia and similar findings were seen.

Differential diagnosis at this stage included bowel obstruction, possibly in the small bowel. This could have been related to an internal hernia or due to adhesions from previous surgery. Other differential diagnoses to exclude were myocardial infarction and pancreatitis.

Investigations

Blood tests, a 12-lead ECG, chest X-ray and abdominal X-ray were performed which were unremarkable.

In view of her persistent abdominal pain, that remained refractory to analgesia, a decision was made to proceed with a contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis. Oral and intravenous contrast was administered which demonstrated a jejunojejunal intussusception.

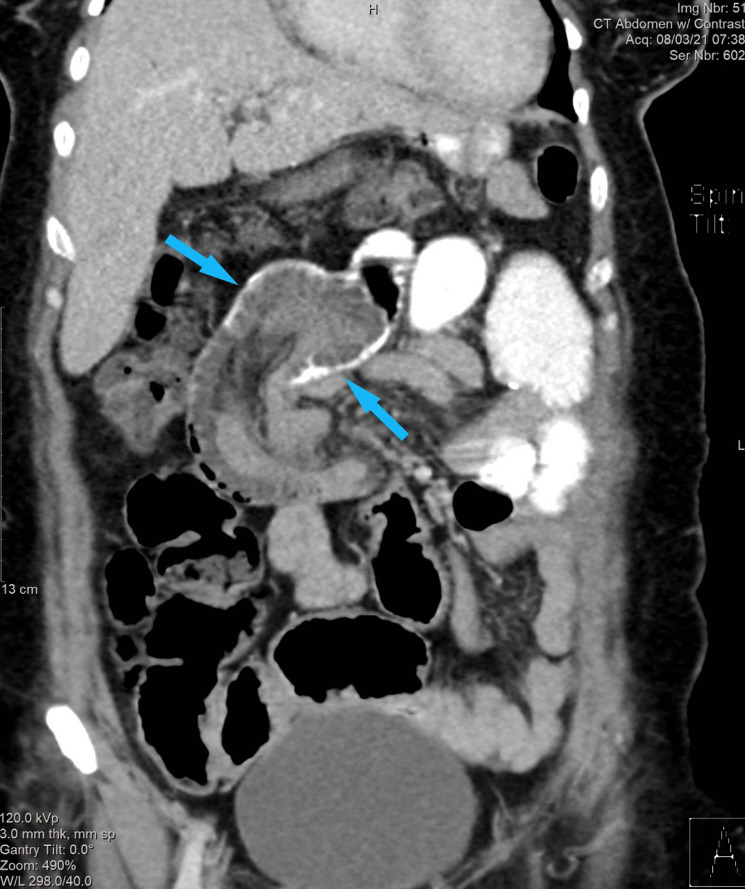

In figure 1, the intussusception can be seen in the CT coronal image of the abdomen and pelvis. This is demonstrated as a ‘bowel within bowel’ configuration with ingested contrast outlining the outer intussusceptum. Proximal small bowel obstruction is also seen.

Figure 1.

The intussusception can be seen in the contrast-enhanced CT coronal image of the abdomen and pelvis. This demonstrates a ‘bowel within bowel’ configuration (blue arrow) with ingested contrast outlining the outer intussuscipiens. Proximal small bowel obstruction is also seen.

The intussusception is also demonstrated as a round mass with intraluminal soft tissue and eccentric fat density, referred to as a target-like lesion in the CT axial image seen in figure 2. We were unable find a well-defined pathological lesion serving as a lead point based on CT.

Figure 2.

The intussusception is also demonstrated as a target-like lesion that is, a round mass with intraluminal soft tissue and eccentric fat density (blue arrow) in the contrast enhanced CT axial image.

Treatment

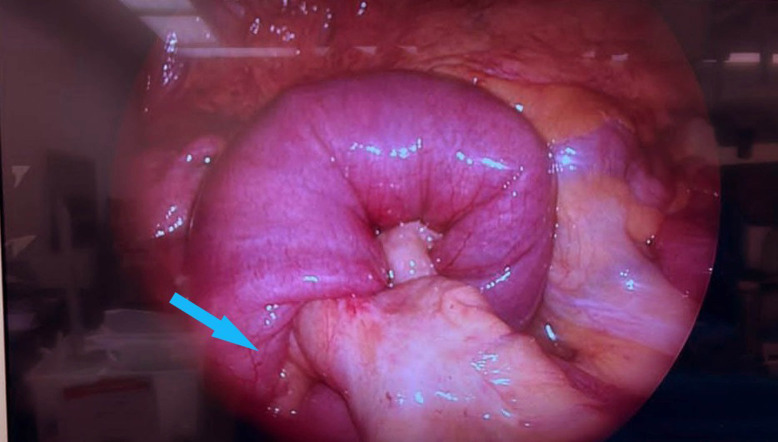

This patient reported severe persistent abdominal pain requiring multiple doses of analgesia and fluid resuscitation. The surgical team were consulted in ED who assessed the patient and reviewed all investigations including CT images of abdomen and pelvis. In view of the patient’s clinical condition in conjunction with the imaging reports, a decision was made to proceed for operative management. The patient underwent an urgent diagnostic laparoscopy. This confirmed the preoperative diagnosis of jejunojejunal intussusception located approximately 250 cm from the terminal ileium (figure 3). A small bowel resection containing the jejunojejunal intussusception segment was performed and a primary anastomosis fashioned. The immediate postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was treated with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. The patient was discharged from hospital after 3 days.

Figure 3.

Intussusception segment on diagnostic laparoscopy showing bowel (blue arrow) telescoping into a contiguous segment of bowel.

Outcome and follow-up

Subsequent histopathology of the resected bowel demonstrated focal oedema in the mucosal and submucosal layers. No benign or malignant lesions were identified.

The patient was evaluated postoperatively in the hospital on day 8. She was well with no documented fever, abdominal pain or vomiting. The wound site examination showed mild serous discharge with no signs of cellulitis and the abdomen was non-tender.

Discussion

Due to its variable presentation and often indolent course, the diagnosis of adult intussusception in ED requires a high index of suspicion. Adult intussusception has been reported across ages, the highest numbers seen in the 30–50 age group. The male: female incidence ratio is approximately 2:1.3 Compared with children, malignancy is more commonly associated with intussusception in adults in up to 42%–65% cases.7 9

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom, reported in more than 70% of cases. The onset is gradual with the average interval between onset and presentation being around 5 weeks, ranging from 1 day to 1 year.3 Around half of all cases have a preoperative diagnosis of bowel obstruction.3 7

Where the small bowel is involved, patients usually present with colicky central abdominal pain and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting are also commonly reported in 40%–60% of cases.

Diarrhoea is often seen in large bowel intussusception and can be associated with lower abdominal pain and blood/mucus in stool and has been reported in 2%–29% of cases.3 12

There have been multiple classifications of adult intussusception described.14–16 Dean’s classification, from 1956, remains commonly used describing four types based on location.15 17 Enteric intussusception is the most common type seen in adults and originates in the small bowel. In ileocecal intussusception, the ileocecal valve becomes the lead point. In ileocolic intussusception, the ileum goes through the ileocaecal valve. In colocolic intussusception, the colon telescopes in a contiguous part of the colon.

Malignancy as a lead point, is more commonly associated with large bowel intussusception, in up to 80% of cases, with adenocarcinoma being the the most common malignant lesion seen. Other malignant lesions include lymphoma, lymphomasarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. The rest are benign lesions like leiomyoma, endometriosis and previous anastomosis.6 18 In contrast, the majority of lead points in small bowel intussusception are benign in nature like lipomas, polyps, haemangiomas, coeliac disease, Henoch Schonlein Purpura, Meckel’s diverticulum, lymphoid hyperplasia and villous adenoma of the appendix. In small bowel intussusception, malignancy is seen in only 14%–47% of cases as metastasis (from melanomas and carcinomatosis), adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and leiomyosarcoma.17 18

Laboratory investigations are not useful in establishing a diagnosis of intussusception. Often the first imaging requested when patients present with abdominal pain and vomiting is a plain abdominal X-ray which has a low sensitivity to rule out bowel obstruction or intussusuception.13 18

Contrary to children, in adults with suspected intussusception, contrast enema studies are rarely performed. Ultrasound has been used regularly to evaluate intussusception in children than in adults and with a skilled operator has a high sensitivity and specificity approaching 100% for intussusception in children. In adults, this is not the case.13 MRI of the small bowel has similar accuracy to CT but requires a stable patient to stay still for a longer period time and may not be as readily available as CT in the ED.13 CT is the imaging modality that more commonly diagnoses intussusception, with most cases found incidentally when performed for non-specific abdominal pain or bowel obstruction.13 Additional diagnostic information around bowel viability and aetiology of intussusception can also be identified with this modality.13 A target-like lesion is seen when the beam is at 90° to the long axis of the intussusception segment. This appears as a round shadow with intraluminal soft tissue and eccentric fat density. The intussusception can also appear like a sausage-shaped mass when the beam is parallel to the long axis of the lesion. When oral contrast is administered, contrast coating of the outer opposing walls of the intussusceptum can also be seen. A kidney-like reniform appearance is also described.13 18 While different appearances of intussusception are described on CT, the presence of a ‘bowel-within-bowel’ appearance is pathognomonic for this condition.19

With increasing accessibility and utilisation of CT, some cases of transient intussusception are also being diagnosed. These are usually self-resolving and, in some cases, asymptomatic. It has been hypothesised intestinal dysmotility results in telescoping of bowel segments in these patients. Transient intussusception has been described in adults with coeliac and Crohn’s disease. Metabolic acidosis, electrolyte disturbances like hyperglycaemic and hyperkalaemia can also be associated with this condition.20

The best practice for management of adult intussusception remains debatable. Well-designed therapeutic trials comparing surgical to non-surgical treatment in adults are lacking.21 In contrast to children, in adults, most cases are managed operatively perhaps due to the higher likelihood of finding a pathological lesion.19 21 Some studies suggest small bowel intussusception can be reduced without resection if an underlying benign lead point is suspected, a medically treated condition is found like inflammatory bowel disease, or if the surgery could result in short bowel syndrome.10 22 It is recommended these cases have a follow-up small bowel enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy to rule out an intraluminal lesion that may predispose to recurrent intussusception.22 Indications for operative management in adult intussusception may include bowel obstruction, a palpable abdominal mass or a lead point identified on imaging, gastrointestinal bleeding, constitutional symptoms of malignancy and colocolic or ileocolic intussusception due to their greater association with malignancy.22 23

Another study reported surgery as the modality of treatment in patients with clinical features of acute abdomen, clinical or radiological signs of bowel obstruction, peritonism, septic shock, intussusception with a mass visible on CT scan, patients with a diagnosis of colonic or ileocolic intussusception (often associated with malignancy), even in the absence of acute abdomen.24

Learning points.

Intussusception is a rare diagnosis in adults with a variable and non-specific presentation.

Most cases are found incidentally on contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis, or intraoperatively.

Adult intussusception is more commonly associated with a well-defined pathological lesion acting as a lead point such as malignancy, compared with children.

In adults, malignancy is more common in intussusception involving the large bowel compared with intussusception in the small bowel.

While there is no consensus on management, it is more common for adult intussusception patients to undergo operative intervention, compared with children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Balamurugan Rathinavelu, Consultant Radiologist, Shaikh Shakhbout Medical City for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @hasqay

Contributors: AHYAZ, JAAJ, SNA and HQ reviewed the patient. AHYAZ, JAAJ and SNA wrote the first draft. HQ conceptualised the idea, reviewed the first draft, and added critically important intellectual data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.intussusception (n.) [Internet]. Index, 2021. Available: https://www.etymonline.com/word/intussusception

- 2.Patel S, Eagles N, Thomas P. Jejunal intussusception: a rare cause of an acute abdomen in adults. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014. 10.1136/bcr-2013-202593. [Epub ahead of print: 28 May 2014]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg 1997;226:134–8. 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagorney DM, Sarr MG, McIlrath DC. Surgical management of intussusception in the adult. Ann Surg 1981;193:230–6. 10.1097/00000658-198102000-00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean DL, Ellis FH, Sauer WG. Intussusception in adults. Arch Surg 1956;73:6–11. 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280010008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begos DG, Sandor A, Modlin IM. The diagnosis and management of adult intussusception. Am J Surg 1997;173:88–94. 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00419-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:1546–51. 10.1007/s10350-006-0664-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, et al. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:407. 10.3748/wjg.15.407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coran AG, WEiLBAECHER AD, Bolin JA, Dav H. Intussusception in adults. Am J Surg 1969;117:735–8. 10.1016/0002-9610(69)90418-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;36:18–21. 10.1097/00004836-200301000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potts J, Al Samaraee A, El-Hakeem A. Small bowel intussusception in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:11–14. 10.1308/003588414X13824511650579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman MJ, Hugh TB, May RE, et al. Intussusception in the adult. ANZ J Surg 1981;51:179–80. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1981.tb05933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne AT, Geoghegan T, Goeghegan T, Govender P, et al. The imaging of intussusception. Clin Radiol 2005;60:39–46. 10.1016/j.crad.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donhauser JL, Kelly EC. Intussusception in the adult. Am J Surg 1950;79:673–7. 10.1016/0002-9610(50)90333-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toso C, Erne M, Lenzlinger PM, et al. Intussusception as a cause of bowel obstruction in adults. Swiss Med Wkly 2005;135:87–90. doi:2005/05/smw-10693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brayton D, Norris WJ. Intussusception in adults. Am J Surg 1954;88:32–43. 10.1016/0002-9610(54)90328-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay R. Ileocecal intussusception in an adult: the laparoscopic approach. 4, 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, et al. Adult intussusception—a CT diagnosis. Br J Radiol 2002;75:185–90. 10.1259/bjr.75.890.750185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YH, Blake MA, Harisinghani MG, et al. Adult intestinal intussusception: CT appearances and identification of a causative lead point. Radiographics 2006;26:733–44. 10.1148/rg.263055100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai J, Ramai D, Murphy T, et al. Transient adult Jejunojejunal intussusception: a case of conservative management vs. surgery. Gastroenterology Res 2017;10:369–71. 10.14740/gr881w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadid T, Elazzamy H, Kafri Z. Bowel intussusception in adults: think cancer! Case Rep Gastroenterol 2020;14:27–33. 10.1159/000505511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenoy S. Adult intussusception: a case series and review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017;9:220. 10.4253/wjge.v9.i5.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erkan N, Hacıyanlı M, Yıldırım M, et al. Intussusception in adults: an unusual and challenging condition for surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis 2005;20:452–6. 10.1007/s00384-004-0713-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panzera F, Di Venere B, Rizzi M, et al. Bowel intussusception in adult: prevalence, diagnostic tools and therapy. World J Methodol 2021;11:81-87. 10.5662/wjm.v11.i3.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]