Abstract

Heterogeneous populations of hypothalamic neurons orchestrate energy balance via the release of specific signatures of neuropeptides. However, how specific intracellular machinery controls peptidergic identities and function of individual hypothalamic neuron’s remains largely unknown. The transcription factor T-box 3 (Tbx3) is expressed in hypothalamic neurons sensing and governing energy status, while human TBX3 haploinsufficiency has been linked with obesity. Here we demonstrate that loss-of-Tbx3 function in hypothalamic neurons causes weight gain and other metabolic disturbances by disrupting both peptidergic identity and plasticity of Pomc/Cart and Agrp/Npy neurons. These alterations are observed following loss of Tbx3 in both immature hypothalamic neurons and terminally differentiated murine neurons. We further establish the importance of Tbx3 for body weight regulation in Drosophila melanogaster and show that TBX3 is implicated in the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESC) into hypothalamic Pomc neurons. Our data indicate that Tbx3 directs the terminal specification of neurons as functional components of the melanocortin system and is required for maintaining their peptidergic identity. In summary, we report the discovery of a mechanistic key process underlying the functional heterogeneity of hypothalamic neurons governing body weight and systemic metabolism.

Introduction

Energy-sensing neuronal populations of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC), including proopiomelanocortin-(Pomc) and agouti-related protein (Agrp)-expressing neurons, release specific neuropeptides that control energy homeostasis by modulating appetite and energy expenditure. Dysregulated activity of these neurons, which constitute key components of the melanocortin system1, is causally linked with energy imbalance and obesity2–4. Considering the constantly changing input into these neurons throughout development and adult life, an intricate intracellular regulatory network must be in place to accommodate plasticity adjustments (as an adequate response to energy state) as well as maintenance of cell identity. Whether extrinsic signals can induce in vivo reprogramming of neuropeptidergic identity has not been resolved, partly because of the limited knowledge of the intracellular factors involved.

To identify genes implicated in maintenance of ARC neuronal identity and energy-sensing function, we took advantage of cell-specific transcriptomic approaches that allow profiling of sub-populations of hypothalamic neurons under basal and metabolically stimulated conditions. We cross-referenced publicly available analyzed datasets from phosphorylated ribosome profiling5, translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP)-based sequencing of leptin receptor-expressing neurons6, and single cell-sequencing7. We determined that the transcription factor termed T-Box 3 (Tbx3) is expressed with unique abundance in hypothalamic neuronal populations critically involved in energy balance regulation, (including ghrelin-and leptin-responsive cells5,6), and that its expression is regulated by scheduled feeding5.

Although Tbx3 is known to influence proliferation8, fate commitment and differentiation9–11 of several non-neuronal cell-types, its functional role during neuronal development, or in postmitotic neurons located in the CNS, is currently uncharted. Intriguingly, this factor appears to be selectively expressed in the ARC within the adult murine hypothalamus12. Moreover, TBX3 mutations in humans have been described to cause Ulnar-Mammary syndrome (UMS), exhibiting hallmark symptoms theoretically consistent with ARC neuron dysfunction, including impaired puberty, deficiency in growth hormone production and obesity13,14.

Thus, we hypothesized that Tbx3 in ARC neurons may control neuronal identity and consequently be of critical relevance for systemic energy homeostasis. To test this hypothesis, we explored the functional role of Tbx3 in both murine and human hypothalamic neurons and investigated whether loss of neuronal Tbx3 impacts systemic energy homeostasis in mice and in Drosophila melanogaster.

We here report that Tbx3 directs postnatal fate and is critical for defining peptidergic identity of both immature and terminally differentiated murine melanocortin neurons, a biological process that is essential for regulation of energy balance.

Results

Tbx3 expression profile in CNS and pituitary

To characterize Tbx3 expression in the central nervous system (CNS), we generated a targeted knock-in mouse model in which the Venus reporter protein is expressed under the control of the Tbx3 locus (Tbx3-Venus mice) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Two areas of the brain displayed a detectable Venus signal, the ARC (Fig. 1a) and the nucleus of the solitary tract (Supplementary Fig. 1), both of which are important in the regulation of systemic metabolism15,16. This hypothalamic expression pattern was confirmed via QRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1) and antiTbx3 immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 1), using an antibody validated in-house using Tbx3-deficient embryos (Supplementary Fig. 1). All Venus-positive cells in the ARC and NTS of Tbx3-Venus mice co-expressed Tbx3, as assessed by immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the model was further validated via Southern blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). This underlines the quality of the newly developed transgenic model.

Figure 1. Loss of Tbx3 in hypothalamic neurons promotes obesity.

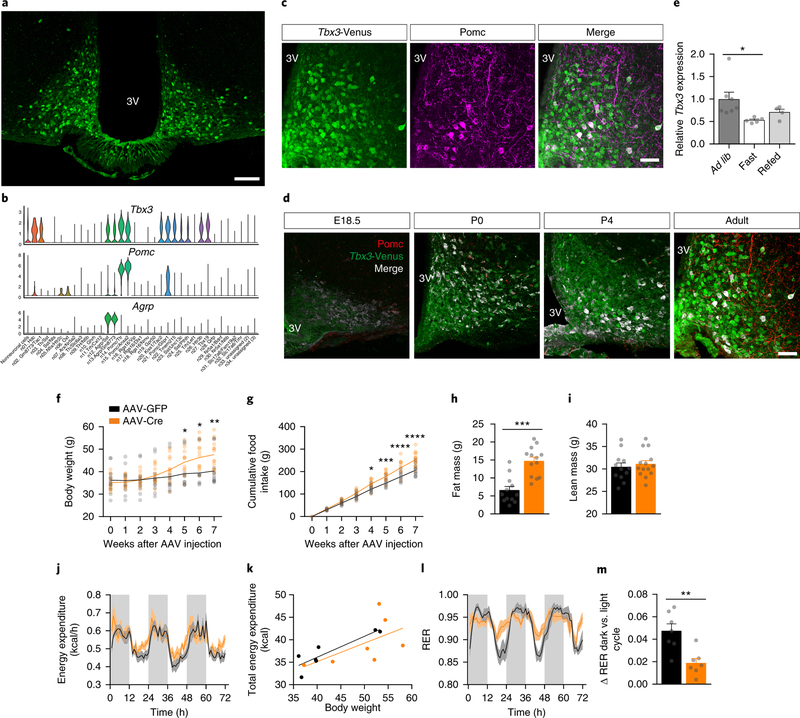

(a) Representative image depicting Tbx3-positive neurons in the ARC of Tbx3-Venus mice, enhanced with GFP immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 100 μm. (b) Violin plots depicting expression of Tbx3, Pomc and Agrp across neuronal clusters identified by Campbell et al.7 Of the 21,086 analyzed cells, 13,079 were identified as neurons and 8,007 as non-neurons based on the expression of the canonical neuronal marker Tubb3. The width of the violin plot at different levels of the log-transformed and scaled expression levels indicates high levels of expression of Tbx3 in neuron clusters 14 (Pomc/Ttr, n = 512), 15 (Pomc/Anxa2, n = 369) and 21 (Pomc/Glipr1, n = 310) compared to the other neuronal clusters. (c) Co-localization between Tbx3-Venus and Pomc in the ARC of Tbx3-Venus mice, assessed by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Co-localization between Tbx3- and Pomc-expressing cells by immunohistochemistry in Tbx3-Venus mice during embryonic (E18.5), neonatal (P0, P4), and adult life (shown previously in Fig. 1c). (e) Quantification of Tbx3 mRNA levels by qRT-PCR in ARC micropunches isolated from adult (12-wk-old) C57BL/6J mice after 24 h of fasting (n=5), or 24 h of fasting followed by 6 h of refeeding (n=4), relative to mice fed ad libitum (n=7). (f) Body weight change and cumulative food intake (g) in adult Tbx3loxP/loxP mice after stereotaxic injection in the medio-basal hypothalamus (MBH) of AAV-Cre (n=14) or AAV-GFP (n=12) particles. (h) Fat mass of AAV-Cre (n=13) or AAV-GFP (n=12)-treated Tbx3loxP/loxP mice, 7 wk after surgery. (i) Lean mass of AAV-Cre (n=14) or AAV-GFP (n=12)-treated Tbx3loxP/loxP mice, 7 wk after surgery. (j) Hourly energy expenditure and total uncorrected energy expenditure correlated to body weight (k) in AAV-Cre (n=7) or AAV-GFP-treated (n=7) Tbx3loxP/loxP mice 4 wk after surgery. (l) Hourly respiratory exchange ratio (RER) and ΔRER averaged between night and day cycles (m) in AAV-Cre (n=7) or AAV-GFP-treated (n=7) Tbx3loxP/loxP mice 4 wk after surgery. 3V, third ventricle. In (k), individual data are presented, and lines depict the fitted regression. In all other analyses, data are mean ± SEM. In (e), *p=0.0476 relative to ad lib. using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posttest. In (f), *p=0.0177, **p=0.0095 using ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-test. In (g), **p=0.0028, ***p=0.0001 and ****p<0.0001 using ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-test. In (h) and (m), ***p<0.0001 and **p=0.0029 and using two-tailed t-test. The experiments in (a) and (c) were repeated more than three independent times with similar results. The experiments in (d) were performed one time with several samples showing similar results.

To further address the cell-specific expression profile of Tbx3, we performed bioinformatic-based re-analysis of a publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing dataset from the ARC7. Our analysis demonstrated overlap of Tbx3 with neurons expressing Pomc, Agrp, kisspeptin (Kiss), and somatostatin (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1), in addition to overlapping with the transcriptional profile of tanycytes, the ‘gateway’ cells to the metabolic hypothalamus17 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Neuroanatomical analysis in Tbx3-Venus mice demonstrated Tbx3 (Venus) expression in almost all ARC Pomc (Fig. 1c) and NTS Pomc neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1), with a comparable pattern of expression from embryonic (E18.5) to postnatal life (P0, P4 and adults) (Fig 1d), indicating that Tbx3 expression in Pomc neurons is switched on embryonically and maintained throughout adult life. As suggested by the analysis of the single cell RNA seq data from the cells from Arc-Median eminence, a significant fraction of Tbx3-positive cells do not express Pomc. Tbx3 transcripts have been previously observed within the pituitary gland18. We found that Tbx3 (Venus) expression was restricted to the posterior pituitary, and that no signal was observed in Pomc-expressing cells of the anterior pituitary (Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, no signs of Tbx3 (Venus) expression were detected in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1) or in microglia (Iba1-positive glial cells) (Supplementary Fig. 1), while a substantial number of Tbx3 (Venus)-positive cells co-expressed the tanycyte and reactive astrocyte marker vimentin (Supplementary Fig. 1), in agreement with single-cell sequencing analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Thus, within the CNS, Tbx3 is expressed in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells known to impact energy homeostasis.

Loss of Tbx3 in hypothalamic neurons promotes obesity

ARC neurons detect changes in energy status, via both direct and indirect sensing of circulating nutrients and hormones, and accordingly modulate their activity to maintain energy balance16. Overnight fasting significantly decreased hypothalamic Tbx3 mRNA levels in the ARC of C57BL/6J mice, while refeeding partially restored Tbx3 expression (Fig. 1e). This suggests that changes in hypothalamic Tbx3 levels are likely involved in the control of systemic metabolism. To test this, we used a viral-based approach to selectively ablate Tbx3 via Cre-LoxP recombination (adeno-associated virus (AAV)-Cre) from the medio-basal (MBH) hypothalamus of 12-wk-old Tbx3loxP/loxP littermate mice (Supplementary Fig. 2).

AAV-Cre-treated mice developed pronounced obesity over the course of 7 wk, with elevated cumulative food intake and higher fat mass relative to control mice (AAV-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated Tbx3loxP/loxP mice), while no difference was observed in lean mass (Fig. 1f–i). Indirect calorimetry did not reveal changes in hourly uncorrected energy expenditure (Fig. 1j), nor in the relationship between total uncorrected energy expenditure and body weight, as demonstrated by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)19 (Fig. 1k). Although the average respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was not altered in AAV-Cre treated mice, these mice displayed metabolic inflexibility relative to controls, as indicated by a flat respiratory exchange ratio with minimal diurnal fluctuations (Fig. 1l–m).

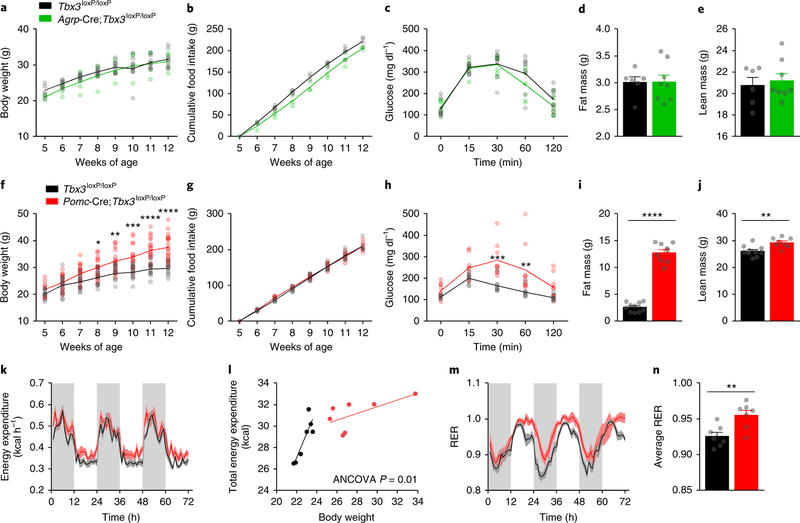

We next asked whether loss-of-function of Tbx3 selectively in either Agrp or Pomc neurons would recapitulate the obesity-prone phenotype observed in the MBH loss-of-function model. No difference in body weight, food intake, glucose tolerance, fat or lean mass was observed in littermate mice bearing a conditional deletion of Tbx3 in Agrp-expressing neurons (Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP) relative to controls (Fig. 2a–e). The quality of this previously validated20 transgenic model was confirmed by the presence of reduced Tbx3 mRNA levels in ARC homogenates (Supplementary Fig. 2), together with a specific reduction of Tbx3 expression within Npy-positive neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Loss of Tbx3 in Pomc but not Agrp neurons triggers obesity.

(a) Body weight in Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=5) relative to control littermates (n=8). (b) Cumulative food intake in Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=3) relative to control littermates (n=4). (c) Glucose tolerance test in adult Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=7) relative to control littermates (n=8). (d) Fat mass and lean mass (e) in adult Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=8) relative to control littermates (n=6). (f) Body weight in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=18) relative to control littermates (n=11). (g) Cumulative food intake in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=7) relative to control littermates (n=7). (h) Glucose tolerance test in adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=9) relative to control littermates (n=8). (i) Fat mass and lean mass (j) in adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=9) relative to control littermates (n=10). (k) Hourly energy expenditure, and energy expenditure correlated to body weight (l), hourly respiratory exchange ratio (RER) (m), and average RER values (n), in 7-wk-old Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=7) relative to control littermates (n=7). Data in (a-k), (m-n), are mean ± SEM. In (f), *p=0.02, **p=0.003, ***p=0.0001, ****p<0.0001 using ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-test. In (h), **p=0.001, ***p=0.0002 using ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-test. In (i-j), ****p<0.0001 and **p=0.0035 using two-tailed t-test. In (n), **p=0.0055 using two-tailed t-test.

In contrast, mice bearing Tbx3 deletion in Pomc-expressing cells21(Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP) displayed elevated body weight relative to control littermates, independently from changes in food intake (Fig. 2f–g). They also had glucose intolerance (Fig. 2h) and increased fat and lean mass (Fig. 2i–j). Indirect calorimetry demonstrated similar hourly energy expenditure – in spite of higher body weight (Fig. 2k), and further revealed a reduction in energy expenditure with respect to body weight in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice relative to controls (Fig. 2l), suggesting that lower systemic energy dissipation might contribute to their obese phenotype. These mice also displayed higher average RER (Fig. 2m–n), indicating that lower lipid utilization might favor the increased adiposity of these mice. A significant reduction in Tbx3 mRNA levels was observed in the hypothalamus of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice, while no changes in Tbx3 mRNA levels were detected in extra-hypothalamic sites expressing Pomc, including the pituitary and adrenals (Supplementary Fig. 2). This transgenic model was further validated via co-staining between Tbx3 and a Cre-dependent membrane GFP reporter, an analysis that revealed blunted Tbx3 immunoreactivity in Cre-positive neurons of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice relative to controls (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, the metabolic alterations observed in this model are attributable to the specific deletion of Tbx3 in Pomc-neurons located in the CNS. Collectively, these data demonstrate that ablation of Tbx3 in ARC neurons has profound functional consequences on energy balance, and that most of these metabolic alterations can be reproduced following specific deletion of this gene in Pomc-positive neurons located in the brain.

Loss of Tbx3 impairs the postnatal melanocortin system

Although Tbx3 is known to control cell-cycle and programming of highly proliferative stem cells and cancer cells9–11,22, its functional role in neurons has remained unexplored. To investigate possible biological mechanisms underlying the metabolic phenotypes observed, we performed Tbx3-focused RNA sequencing and proteomic analyses in hypothalamic tissue as well as in primary hypothalamic cultures. The impact of Tbx3 deletion on transcription in hypothalamic neurons was assessed using primary neurons isolated from Tbx3loxP/loxP mice and infected with adenoviral (Ad) particles carrying the coding sequence for Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) or GFP (Ad-GFP) as a control (Supplementary Fig. 3), an approach that effectively allows knockdown of Tbx3 (Supplementary Fig. 3) in the absence of cell toxicity (Supplementary Fig. 3). Because we had found the most important in vivo metabolic effects with Tbx3 deletion uniquely within Pomc-expressing cells, we performed RNA sequencing of the WT and Tbx3-KO primary hypothalamic cultures and identified genes that were both differentially expressed in this in vitro model and known to be expressed in Pomc neurons. This analysis highlighted 449 transcripts that were differentially expressed (243 downregulated, 206 upregulated). Unbiased pathway analysis revealed that Tbx3 deletion significantly downregulated the expression of genes controlling cellular proliferation, differentiation and determination of cellular fate (Supplementary Fig. 3). In turn, several genes linked with intracellular metabolic pathways were upregulated, albeit in a less significant way (Supplementary Fig. 3). To complement this unbiased approach, in silico analysis of the genomic loci coding for Pomc, Cart and Agrp for potential Tbx3 binding sites (Tbox binding motifs) was performed23. Potential Tbx3 binding sites were found in all three genes, suggesting that Tbx3 could alter their transcription directly (Supplementary Fig. 3). To further explore the molecular machinery linked with Tbx3 in hypothalamic neurons, we performed immunoprecipitation of Tbx3 from adult C57BL/6J mouse hypothalami followed by mass spectrometry to identify Tbx3-interacting proteins. 142 proteins were significantly enriched by Tbx3 precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2), including previously known Tbx3 interactors such as Kif2124, AES25 and Tollip26. Pathway analysis of these interacting proteins highlighted their role in several processes, notably including inter- and intra-cellular signaling and neuronal development (Supplementary Fig. 3). These genomic and proteomic data led us to test the hypothesis that lack of Tbx3 in the ARC might interfere with the cellular fate and differentiation stage of these neurons, and therefore impact their peptidergic profile, in addition to potentially affecting neuropeptide generation via direct transcriptional actions.

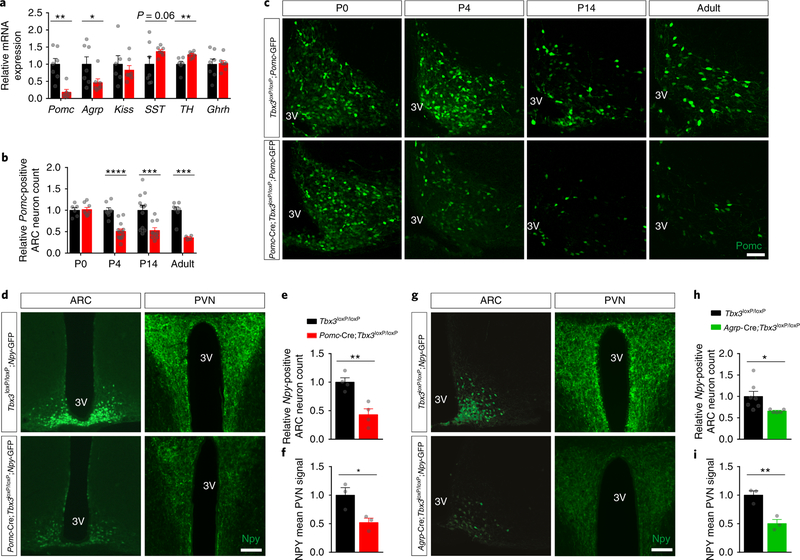

Accordingly, we measured Pomc and Agrp mRNA expression in WT and Tbx3-KO primary hypothalamic neurons by qRT-PCR. Both transcripts were significantly downregulated following Ad-Cre-mediated Tbx3 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 4). These changes were reproducible in vivo, as we found significantly lower expression levels of Pomc and Agrp mRNA in the ARC of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice relative to control littermates (Fig. 3a). No changes in Kiss or growth hormone releasing hormone (Ghrh) mRNA levels were observed in these animals, whereas mRNA levels of tyrosine hydroxylase were elevated and there was a trend toward elevated levels of somatostatin (Fig. 3a). To explore whether these changes in their peptidergic expression profile were caused by neurodevelopmental alterations, Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice were crossed with Pomc-GFP reporter animals in order to precisely quantify Pomc-expressing cells during both embryonic and postnatal life, when ARC-Pomc neurons are generated and acquire their terminal peptidergic identity27,28. No difference in Pomc neuronal cell number was detected in this model at embryonic day (E) 14.5, E15.5, or E18.5, implying normal neuronal generation in utero (Supplementary Fig. 4). No change in Pomc counts was observed at postnatal day (P) 0, whereas a substantial reduction in the number of Pomc-positive neurons was found at P4, and this relative decrement remained at P14 and 12 wk (adult) (Fig. 3b–c). Despite progressive loss of Pomc expression at P2 and P4, no significant apoptotic activity was observed in this region (Supplementary Fig. 4); nor did we detect any proliferation leading to new Pomc-positive neurons between P0 and P3, as assessed using BrdU (Supplementary Fig. 4), confirming that most Pomc neurons are generated during embryonic life28, and suggesting that neurogenesis and/or cellular turnover do not contribute to Tbx3-mediated control of Pomc expression observed during neonatal life . Furthermore, no compensatory change was observed in the Pomc-processing enzymes of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Collectively, these data demonstrate that constitutive loss of Tbx3 in Pomc-expressing neurons undermines the melanocortin system, likely by interfering with the proper terminal differentiation of this neuronal population during postnatal life and possibly via direct transcriptional actions.

Figure 3. Loss of Tbx3 impairs the postnatal melanocortin system.

(a) Quantification of enzyme and neuropeptide mRNA levels by qRT-PCR in ARC micropunches isolated from adult (12-wk-old) Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (n=7) and control Tbx3loxP/loxP littermates (n=7). Kiss: kisspeptin, SST, somatostatin, TH, tyrosine hydroxylase, Ghrh, growth hormone-releasing hormone. (b) Quantification and representative images (c) of the relative number of Pomc-expressing neurons in the ARC of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP mice and in control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP) at different stages of neonatal life, as well as in adult animals. Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP: n=6 (P0), n=8 (P4), n=12 (P14), n=7 (adult). Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP: n=8 (P0), n=13 (P4), n=10 (P14), n=4 (adult). (d) Representative images and relative quantification (e) of Npy-positive neurons in the ARC of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP mice (n=4) and control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP, n=4). (f) Npy-positive neuronal fibers in the PVN of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP mice (n=3) and control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP, n=3). (g) Representative images and relative quantification (h) of Npy-positive neurons in the ARC of adult Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP mice (n=5) and control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP, n=7). (i) Npy-positive neuronal fibers in the PVN of adult Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP mice (n=3) and control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Npy-GFP, n=3). 3V, third ventricle. Scale bars in (c) are 50 μm and scale bars in (d-g) are 100 μm. Data (a-b), (e-f), and (h-i) are mean ± SEM. In (a), **p=0.0017 (Pomc), **p=0.0097 (TH), *p=0.0049 using two-tailed t-test. In (b), ****p<0.0001 (P4), ***p=0.0032 (P14), ***p=0.0002 (Adult) using two-tailed t-test. In (e-f), **p=0.0043, *p=0.034 using two-tailed t-test. In (h-i), *p=0.04, **p=0.0087 using two-tailed t-test. The experiments in (c) were repeated more than three independent times with similar results. The experiments in (d) and (g) were repeated two independent times with similar results.

Loss of Tbx3 alters the peptidergic profile of Agrp neurons

In agreement with the mRNA analysis documenting reduced ARC Agrp mRNA (Fig. 3a), Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice displayed a reduced number of neuropeptide Y (Npy)-expressing neurons (co-expressed in the vast majority of Agrp neurons29) in the ARC (Fig. 3d–e). This was also reflected by reduced Npy projection density in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (Fig. 3d–f), as demonstrated by crossing Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice with Npy-GFP reporter animals. Since a significant fraction of Agrp/Npy neurons are derived from Pomcexpressing cells27, Cre-mediated ablation of Tbx3 in these cells may interfere with Agrp/Npy expression in this animal model. This suggests that Tbx3 action in Agrp-expressing neurons may be similarly implicated in controlling the peptidergic profile of this specific neuronal subpopulation. To test this hypothesis, we crossed Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice with Npy-GFP reporter mice, and quantified their number of Npy-positive neurons as well as their neuronal projections. A significant decrease in Npy-positive neurons in the ARC (Fig. 3g–h), and Npy immunoreactivity in the PVN (Fig. 3g–i), were observed in Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP; Npy-GFP mice relative to littermate controls, as well as a significant reduction in ARC Agrp mRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, Tbx3 action in hypothalamic ARC neurons controls the peptidergic expression profiles of different neuronal sub-populations.

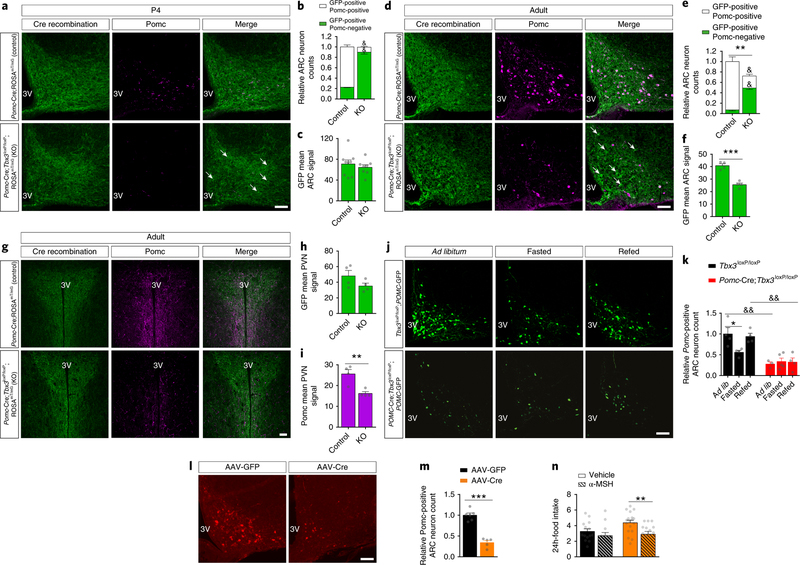

Tbx3 is critical for the differentiation of Pomc neurons

To further delineate the process underlying Tbx3-mediated control of neuropeptide expression, we used a cell lineage approach and crossed Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice with ROSAmT/mG reporter mice to genetically and permanently label cells undergoing Cre-mediated recombination (via the Pomc-Cre driver), as well as their neuronal projections. We then quantified Pomc expression and assessed its co-localization with GFP, indicative of Cremediated recombination. The P4 Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG pups had a significantly reduced number of Pomc-positive cells relative to controls (Fig. 4a–b, raw counts available in Supplementary Table 3), thus reproducing our previously obtained results (Fig. 3b–c). However, no change was observed in the number of neurons or in neuronal-fiber density by analyzing Cre-recombined (GFP-expressing) cells (Fig. 4a–c). These data are in agreement with the absence of apoptotic events at P2–4 (Supplementary Fig. 4) and demonstrate that loss of Tbx3 function in Pomc-expressing cells does not affect cellular survival or neuronal architecture during embryonic or early postnatal development. Instead, most Cre-recombined neurons in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice lacked Pomc immunoreactivity (Fig. 4a–b, indicated with arrows), suggesting that Tbx3 ablation in Pomc-positive cellular populations disrupts their normal peptidergic identity. Such alteration in Pomc neuronal identity in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG was also observed in adult animals (Fig. 4d–e, indicated with arrows, raw counts available in Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, Cre-recombined cells in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG had reduced expression of Cart compared to controls, indicating that the peptidergic alterations in this model are not limited to Pomc (Supplementary Fig. 5, raw counts available in Supplementary Table 3). A slight decrease in the number of Cre-recombined cells and in neuronal fiber density in the ARC and PVN was observed in adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice compared to controls (Fig. 4d–i). We hypothesize that this is indicative of cellular loss in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice during adulthood, since this phenomenon occurs only after the peptidergic identity impairment observed at P4. We speculate that Tbx3 deletion in hypothalamic Pomc neurons may impair neuronal maturation during postnatal life, and that this might in turn provoke cell death in a sub-population of neurons during the transition into adult life. On the other hand, these results could also be linked with reduced postnatal neurogenesis and/or impaired neuronal turnover of Pomc-positive cells in Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice, perhaps linked with the condition of obesity observed in these animals. The concept of postnatal hypothalamic neurogenesis, however, remains controversial30. These data collectively demonstrate that Tbx3 plays a fundamental role in maintaining the identity of ARC Pomc-expressing cells, a process that underlies changes in the neuropeptidergic profile of these neurons and consequently in systemic energy homeostasis.

Figure 4. Tbx3 is critical for the differentiation of Pomc neurons.

(a) Representative images and relative quantification (b) of GFP-expressing neurons (Cre recombination) and Pomc-positive neurons in the ARC of P4-old Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice (n=8) relative to controls (Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG, n=9), assessed by immunohistochemistry. Arrows depict GFP-positive/Pomc-negative cells. (c) Relative densitometric analysis of Cre recombination (GFP immunoreactivity) in the ARC of P4old Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice (n=8) and controls (n=9). (d) Representative images and relative quantification (e) of GFP-expressing neurons (Cre recombination) and Pomc-positive neurons in the ARC of adult (12-wk old) Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice (n=4) and controls (n=4), assessed by immunohistochemistry. Arrows depict GFP-positive/Pomc-negative cells. (f) Relative densitometric analysis of Cre recombination (GFP immunoreactivity) in the ARC of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice (n=4) and controls (n=4). (g) Representative images depicting Cre recombination (GFP immunoreactivity) and Pomc-positive neuronal fibers in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice and controls, assessed by immunohistochemistry. (h) Relative densitometric analysis of Cre recombination (GFP immunoreactivity) and Pomc immunoreactivity (i) in the PVN of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice (n=4) and controls (n=4). (j) Representative image and cell number quantification (k) of Pomc-positive neurons in the ARC of adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP mice or control littermates (Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP) after 15-h of fasting with or without 2 h of refeeding. Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP: n=4 for each condition. Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP: n=3 (Ad lib), n=5 (Fasted), n=4 (Refed). (l) Representative images and relative quantification (m) of Pomc-expressing neurons in the ARC of adult Tbx3loxP/loxP mice 7 wk after AAV-Cre (n=5) or AAV-GFP (n=6) MBH injection. (n) 24-h food intake measured in adult Tbx3loxP/loxP mice 7 wk after AAV-Cre or AAV-GFP MBH injection, following intracerebroventricular administration of vehicle or αMSH. AAV-Cre: n=18 (vehicle), n=15 (αMSH). AAV-GFP: n=14 (vehicle), n=12 (αMSH). 3V, third ventricle. Scale bars in (a-d-g-j-l) are 50 μm. Data are mean ± SEM. In (b) and (e), &p<0.0001 for comparisons of GFP-positive/Pomc-positive or GFP-positive/Pomc-negative sub-populations counts between PomcCre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice and controls, **p=0.0025 for comparison between total number of Cre-recombined neurons of Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice and controls, using ANOVA followed by Sidak’s posttest. In (f) and (i), ***p=0.0003 and **p=0.0071 using two-tailed t-test. In (k), *p=0.04, &&p=0.011 comparing Ad lib Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice vs Ad lib controls, &&p=0.027 comparing Refed Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;ROSAmT/mG mice vs Refed controls, by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. In (m), ***p<0.0001 using two-tailed t-test. In (n), **p=0.0061 by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. The experiments in (a) were repeated two independent times with similar results. The experiments in (d), (g), (j) were performed one time with several samples showing similar results. The experiments in (l) were repeated two independent times with similar results.

Tbx3 controls identity and plasticity of mature Pomc neurons

Since ARC Tbx3 levels are modulated by nutritional status in mice (Fig. 1e), we asked whether Tbx3 in hypothalamic Pomc neurons might be implicated in the previously observed plastic ability of these cells to adjust Pomc expression and release in response to changes in nutritional status31. Pomc-positive cells and Pomc immunoreactivity were measured in adult Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFP and control animals in the ad libitum-fed condition and after exposure to a fasting/refeeding paradigm. In controls, fasting reduced Pomc-positive cell counts (Fig. 4j–k) and Pomc immunoreactivity (Supplementary Fig. 5) relative to what occurred in ad libitum-fed mice, while refeeding normalized Pomc expression, as previously reported31. In contrast changes in nutritional status failed to alter Pomc expression in adult PomcCre;Tbx3loxP/loxP;Pomc-GFPmice (Fig. 4j–k, Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that Tbx3 is implicated in fine-tuning Pomc expression in response to energy needs. These data also suggest that Tbx3 likely controls the peptidergic profile of fully differentiated hypothalamic neurons of adult mice. To assess this possibility, we quantified Pomc-positive neurons in our adult-onset model of viral-mediated hypothalamic Tbx3 deletion. A prominent reduction of ARC Pomc-positive cells was observed (Fig. 4l–m), with no changes in apoptotic events (Supplementary Fig. 5), implying that loss of Tbx3 in fully mature and specified neurons alters their peptidergic identity. To uncover whether such alteration might underlie hyperphagia and therefore the obese phenotype observed in AAV-Cre treated mice, we challenged these animals with intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of the biologically active Pomc-derived peptide alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) at a sub-effective dose. ICV injection of this dose of α-MSH had a slight, non-significant hypophagic effect in control (AAV-GFP) mice. In contrast, this approach significantly normalized food intake in AAV-Cre treated animals to the level of control AAV-GFP mice (Fig. 4n). Together, these results document that Tbx3 knockdown in fully differentiated ARC neurons impairs their peptidergic expression profile under non-stimulated conditions and undermines the ability of Pomc neurons to adjust Pomc expression and release in response to changes in nutritional status. These alterations, in turn, provoke dysregulated central melanocortin tone, a blunted neuronal response to the organism’s nutritional status, and ultimately obesity.

Tbx3 functions are conserved in Drosophila and human neurons

The T-Box family of transcription factors is remarkably conserved among species32. In Drosophila melanogaster, a Tbx3 homolog protein is encoded by the gene omb (or bifid). Omb is expressed in the CNS of adult flies, as assessed by double immunohistochemistry between omb and the synaptic marker bruchpilot (labeled by the Nc82 antibody) (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 6). To address whether neuronal Tbx3 action on energy homeostasis is conserved in Drosophila, we generated flies bearing an inducible nervous system-specific omb knockdown system (Fig. 5b). Relative to what occurred in controls (RNAi off), knockdown of omb (RNAi on) induced a significant increase in body fat content (Fig. 5c). These results were reproduced in a second transgenic Drosophila model using a different omb RNAi targeted sequence (Supplementary Fig. 6).

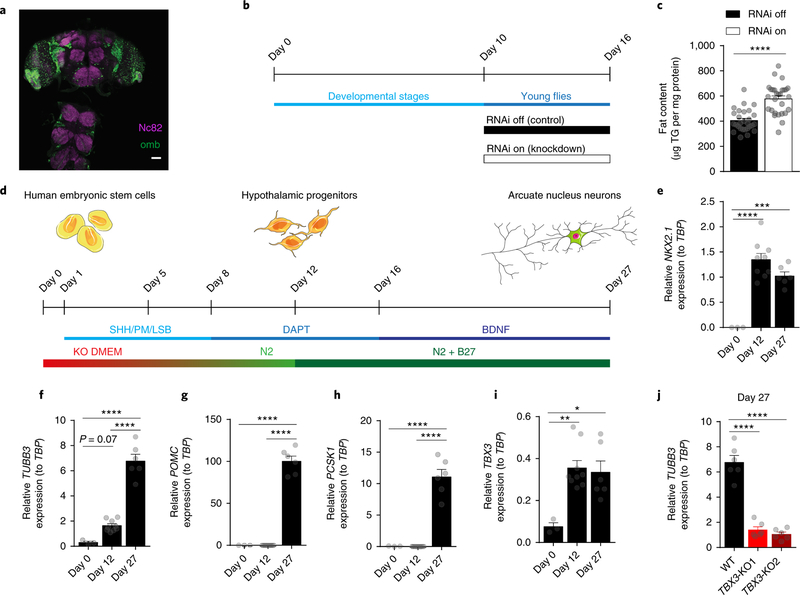

Figure 5. Tbx3 functions in Drosophila and human neurons.

(a) Representative image depicting expression of the Drosophila Tbx3 ortholog omb (omb expression assessed via GFP in ombP3-Gal4>GFP flies) and Nc82 (neuronal marker) in the central nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Scale bar = 50 μm. (b) Timeline of RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown of omb (RNAi on), and control flies (RNAi off). (c) Quantification of Drosophila body fat content following knockdown of omb (RNAi on, n=28) compared to controls (RNAi off, n=28) using the omb-RNAi line 1. (d) Differentiation of human ESC into hypothalamic arcuate-like neurons. The combination of dual SMAD inhibition (L, LDN193189, 2.5 μM; SB, SB431542, 10 μM), early activation of sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling (100 ng/ml SHH; SHH agonist PM, purmorphamine, 2 μM) and step-wise switch from ESC medium (KO DMEM) to neural progenitor medium (N2) followed by inhibition of Notch signaling (DAPT, 10 μM) converts hESC into hypothalamic progenitors. For neuronal maturation, cells are cultured in neuronal medium (N2 + B27), treated with DAPT and subsequently exposed to BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, 20 ng/ml). Gene expression analyses of (e) NKX2.1, (f) TUBB3, (g) POMC, (h) PCSK1, and (i) TBX3 over the time course of differentiation of ESC into hypothalamic neurons by qRT-PCR. (j) Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR of TUBB3 in wildtype (WT) human ESC clones and in TBX3 knockout (TBX3-KO1 and TBX3-KO2) cell lines at ARC-like neurons (Day 27) stage. Data are mean ± SEM. In (e-i), n=3 (day 0), n=9 (day 12), n=6 (day 27). In (j), n=6 per group. In (c), ****p<0.0001 using two-tailed t-test. In (e), ****p<0.0001 and ***p=0.0005 using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. In (f-i), *p=0.01,**p=0.0039, and ****p<0.0001 using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. In (j), ****p<0.0001 using ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test. The experiment in (a) was repeated two independent times with similar results.

To determine whether Tbx3 loss-of-function phenotypes can be recapitulated in a relevant human neuro-cellular model system, we investigated the role of TBX3 in the control of differentiation and the peptidergic profile of human hypothalamic neurons. H9 human embryonic stem cells (hESC; WA09; WiCell) were differentiated into ARC-like neurons over the course of 27 d (Fig. 5d), as previously described33–35. In this in vitro human hypothalamic neuronal model, NKX2.1 expression can be observed by Day 12 of differentiation, corresponding to the hypothalamic progenitor stage (Fig. 5e). Low level expression of Class III β-tubulin (TUBB3), a neuronal differentiation marker, occurs by Day 12 and reaches maximum at Day 27 (Fig. 5f). Expression of POMC and its processing enzyme Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 1 (PCSK1) can be detected following neuronal maturation at Day 27 (Fig. 5g–h). TBX3 expression was observed in this model at Day 12 of differentiation, corresponding to the NKX2.1-positive hypothalamic progenitor stage, and TBX3 levels remained stable in differentiated ARC-like neurons as obtained on Day 27 (Fig. 5i).

To assess the impact of TBX3 deletion on human hypothalamic neuronal differentiation, two independent TBX3-KO hESC lines were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Despite efficient TBX3 ablation (Supplementary Fig. 6), no change in hypothalamic progenitor marker NKX2.1 was observed at Day 12 in either TBX3-KO line (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting normal differentiation into hypothalamic progenitors. At Day 27, NKX2.1 as well as TUBB3, the marker for neuronal differentiation, were greatly reduced in TBX3-KO cells as compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 6, Fig. 5j, respectively), indicative of an impaired neuronal maturation state in the TBX3-KO condition in this in vitro human neuro-cellular model system. In silico analysis of the genomic loci of genes coding for human POMC, CART and AGRP for potential Tbx3 binding sites (T-box binding motifs) revealed, as in mice, Tbx3 binding sites in all three genomic loci (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, since the strong reduction in TUBB3 in the absence of TBX3 indicates that some hypothalamic differentiation programs are halted, further analysis of expression levels for neuropeptides such as POMC is precluded.

Together, these data reveal that TBX3 is essential for the maturation of hypothalamic progenitors into ARC-like POMC-expressing neurons. Furthermore, our data suggest that Tbx3 has a conserved role in the regulation of energy homeostasis in invertebrates and mammals, including humans, albeit the molecular and cellular underpinnings might differ across different species.

Discussion

The heterogeneity of hypothalamic ARC neurons allows rapid and precise physiological adaptation to changes in body energy status and is thus highly relevant for adequate maintenance of energy homeostasis. While several transcriptional nodes are known to establish hypothalamic neuronal identity by controlling early neurogenesis and cellular fate during embryonic life28,36–38, the molecular program driving the terminal specification and identity maintenance of ARC neurons during postnatal life remains incompletely understood, with some advances identifying Islet-139,40, Bsx41, and miRNA’s42 as crucial regulators.

In the present experiments, we demonstrate that the transcription factor Tbx3 is required for terminal specification of hypothalamic ARC melanocortin neurons during neonatal development, and is also required for the normal maintenance and plasticity of their peptidergic program throughout adulthood.

Our work highlights a previously uncharacterized role for Tbx3 in the regulation of energy metabolism. The brain expression profile and the functional data presented reveal that Tbx3 action in hypothalamic neurons contributes to the CNS-mediated control of systemic metabolism. Loss of Tbx3 in Pomc-expressing neurons during development causes glucose intolerance and obesity secondary to decreased energy expenditure and lipid utilization in adult mice.

These metabolic alterations are accompanied by a massive decrease in the number of Pomc-expressing neurons during postnatal life, independently from changes in the cell number, which likely underlies the observed obesity phenotype. In agreement, neonatal Pomc neuronal ablation promotes similar metabolic alterations43. Intriguingly, constitutive loss of Tbx3 specifically in Agrp/Npy co-expressing neurons does not translate into phenotypic metabolic changes, albeit with a significant reduction in Agrp and Npy expression. Such lack of metabolic alterations in this model is likely the result of compensatory developmental mechanisms masking the ability of Agrp and Npy to modulate systemic metabolism44, a phenomenon previously observed following neonatal Agrp/Npy neuronal ablation45,46. Thus, Tbx3 impacts systemic energy homeostasis by controlling the peptidergic identity profile of different populations that directly modulate the activity of the melanocortin system in ARC neurons during neonatal life, when maturation of the melancortin system occurs28,47.

Importantly, Tbx3 deletion in fully mature adult hypothalamic ARC neurons selectively reduces the number of Pomc-expressing neurons, phenocopying the observation in mice with Pomc-promoter-driven deletion of Tbx3 from the genome at mid-term developmental stages. This translates into dysregulated central melanocortin tone that is in turn linked to hyperphagia, alteration in systemic lipid oxidation capacity, and obesity. All of these are in agreement with the physiological role of Pomc neurons and the central melanocortin system during adulthood48,49. Thus, Tbx3 is required not only for establishing POMC identity during neonatal life, but likely plays a key role in maintaining the peptidergic identity and functional activity of fully differentiated ARC neurons.

The cellular and metabolic effects provoked by Tbx3 ablation in hypothalamic ARC neurons are independent from neuronal survival and/or turnover, as demonstrated by our cell-lineage tracing approach. Rather, Tbx3 seems to direct intracellular programs controlling the neuronal differentiation state, in agreement with previous studies linking Tbx3 intracellular activity with differentiation and cell fate commitment in non-neuronal cells9–11. Whether Tbx3 loss-of-function in immature and/or fully differentiated hypothalamic neurons may induce cellular reprogramming and a peptidergic identity switch is a compelling hypothesis requiring further scrutiny, but it is supported by evidence of neuronal developmental plasticity within the mammalian CNS50–52. In this context, our in silico-based prediction of Tbx3 binding sites suggests that the observed changes in the peptidergic identity profiles might be also explained by direct transcriptional effects in Pomc, Cart and Agrp genomic loci. However, a more comprehensive and unbiased analysis, such as by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing, will be required to directly test this hypothesis. Similarly, a detailed characterization of the molecular machinery controlled by Tbx3 in hypothalamic neurons will be necessary to elucidate the main intracellular mechanisms underlying the metabolic effects observed. Our profiling of genes and proteins linked with Tbx3 does not allow causally linking them with the metabolic changes observed, but this initial effort may spur future research addressing the role of such Tbx3-linked machinery in the context of obesity. It will be also of paramount importance to determine whether Tbx3 influences neuropeptidergic profiles and systemic metabolism via interactions with known metabolic signals implicated in neuronal specification, such as neurogenin 3, Mash1, OTP, or Islet-137–39.

Our observations in Drosophila melanogaster suggest that the link between neuronal Tbx3 action and systemic energy homeostasis is likely evolutionarily conserved, albeit our data do not allow to comprehend the cellular and molecular mechanism underlying the obese-like phenotype observed in flies, nor whether these mechanisms are conserved across different species. Since Drosophila does not express Pomc, Agrp, or any homolog peptide, another neuronal population might link Tbx3 action with adiposity regulation in this species. Intriguingly, our data show that TBX3 is essential for the maturation of hypothalamic progenitors into ARClike human neurons. Since human subjects with TBX3 mutations display pathological conditions consistent with ARC neuronal dysfunction (obesity, impaired GHRH release, and alterations in reproductive capacity13,14), we speculate that mutations affecting TBX3 in humans might undermine ARC neuronal differentiation status and/or peptidergic profiles, changes which ultimately impact body weight regulation, reproduction and growth. Thus, our findings might have implications for human pathophysiology.

Neurons sensitive to the orexigenic hormone ghrelin express Tbx3, such that ghrelin may also regulate directly Tbx3 expression5. Moreover, we uncovered a clear link between nutritional status, Tbx3 action, and neuropeptide expression in hypothalamic Pomc neurons. Whether hormonal factors and nutritional status in turn alter the peptidergic identity of hypothalamic neurons in physiological or pathophysiological conditions via modulation of Tbx3 remains a critical question. A detailed characterization of the role of Tbx3 in the context of nutritional and hormonal-based regulation of hypothalamic neuronal activity might help in deciphering the main environmental factors controlling peptidergic identity development, maintenance and potential plasticity in mammalian CNS neurons.

We uncovered a molecular switch implicated in the terminal differentiation of body weight-regulating ARC neurons into specific peptidergic subtypes, unraveling one of the mechanisms responsible for the neuronal heterogeneity of hypothalamic ARC neurons. Our findings represent another step toward the identification the key molecular machinery controlling the functional identity of hypothalamic neurons, particularly during postnatal life, and this may in turn facilitate the understanding of the fundamental neuronal mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of obesity and its associated metabolic perturbations.

Material and methods

Ethical compliance statement.

All animal experiments were approved and conducted under the guidelines of the Helmholtz Zentrum Munich and of the Faculty Animal Committee at the University of Santiago de Compostela.

Mice

All experiments were conducted on male mice. Mice were fed standard chow diet, and group-housed on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle at 22 °C with free access to food and water unless indicated otherwise. C57BL/6J mice were provided by Jackson Laboratories. Tbx3loxP/loxP mice were generated previously53 and backcrossed on a C57BL/6J background for 5 generations. Pomc-Cre mice (Jax mice stock# 596521) and Agrp-Cre mice (Jax mice stock # 01289920) were mated with Tbx3loxP/loxP mice to generate Pomc and Agrp-specific Tbx3-knockout mice (Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP, or Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP). Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP and control (Pomc-Cre) mice were crossed with a ROSAmT/mG reporter line (Jax mice stock# 00757654) so that neurons that express Pomc are permanently marked. Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP, Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP or control mice (Tbx3loxP/loxP) were crossed with mice that selectively express the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in Npy-expressing neurons (Npy-GFP, Jax mice stock# 00641755) or in Pomc-expressing neurons (Pomc-GFP Jax mice stock# 00959356).The Tbx3-Cre-Venus mouse line was created by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. The coding sequences for 2A peptide bridges, Cre recombinase and Venus fluorescent protein, and bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal were cloned into a targeting vector between 5’ and 3’ homology arms flanking the stop codon of the Tbx3 locus. Homologous recombination was confirmed by PCR and southern blot analysis (using the DIG system from Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For the studies involving embryos, the breeders were mated 1 h before the dark phase and checked for a vaginal plug the next day. The day of conception (sperm positive vaginal smear) was designated as embryonic day 0. The day of birth was considered postnatal day 0. See additional information on the Reporting Summary.

Physiological measures

To measure food consumption, mice were housed 2 to 3 per cage. Body composition (fat and lean mass) was measured using quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance technology (EchoMRI, Houston, TX). Energy expenditure and the respiratory exchange ratio were assessed using a combined indirect calorimetry system (TSE PhenoMaster, TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany). O2 consumption and CO2 production were measured every 10 min for a total of up to 120 h (after a minimum of 48 h of adaptation). Energy expenditure (EE, kcal/h) values were correlated to the body weight of the animals recorded at the end of the measurement using analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA)19. For the analysis of glucose tolerance, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.75 g glucose per kg of BW (Agrp-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice) or 1.5 g glucose per kg of BW (Pomc-Cre;Tbx3loxP/loxP mice). 20% (wt/v) D glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.9% (wt/v) saline was used. Tail blood glucose concentrations (mg/dl) were measured using a handheld glucometer (TheraSense Freestyle).

Viral-mediated deletion of Tbx3

To ablate Tbx3 in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH), recombinant adeno-associated viruses (AAV) carrying the Cre recombinase and the hemagglutinin (HA)-tag (AAV-Cre), or control viruses carrying renilla GFP (AAV-GFP), were generated as previously described57 and injected bilaterally (0.5 μl/side; 1.0 × 1011 viral genomes/ml) into the MBH of Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (12-wkold), using a motorized stereotaxic system from Neurostar (Tubingen, Germany). The nuclear localization signal (nls) of the simian virus 40 large T antigen and the Cre-recombinase coding region was fused downstream of the hemagglutinin (HA)-tag, in a rAAV plasmid backbone containing the 1.1kb CMV immediate early enhancer/chicken β-actin hybrid promoter (CBA), the woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE), and the bovine growth hormone poly(A) (bGH) to obtain rAAV-CBA-WPRE-bGH carrying Cre-recombinase (AAV-Cre). The rAAV-CBA-WPRE-bGH backbone carrying the renilla GFP cDNA (Stratagene) was used as negative control. rAAV chimeric vectors (virions containing a 1:1 ratio of AAV1 and AAV2 capsid proteins with AAV2 ITRs) were generated by transfecting HEK293 cells with the AAV cis plasmid, the AAV1 and AAV2 helper plasmids, and the adenovirus helper plasmid by standard PEI transfection methods. Sixty hours after transfection, cells were harvested and the vector purified using OPTIPREP density gradient (Sigma). Genomic titers were determined using the ABI 7700 real time PCR cycler (Applied Biosystems) with primers designed to WPRE. Virus were injected bilaterally (0.5 μl/side; 1.0 × 1011 viral genomes/ml) into the MBH of Tbx3loxP/loxP mice (12-wk-old), using a motorized stereotaxic system from Neurostar (Tubingen, Germany). Stereotaxic coordinates were −1.6 mm posterior and +/−0.25 mm lateral to bregma and −5.8 mm ventral from the dura. During the same procedure, a stainless-steel cannula (Bilaney Consultants GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany) was implanted into the lateral cerebral ventricle. Stereotaxic coordinates for intracerebroventricular (icv) injections were −0.8 mm posterior, −1.4 mm lateral from bregma and −2.0 mm ventral from dura. Surgeries were performed using a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100 and 7 mg/kg, respectively) as anesthetic agents and Metamizol (200 mg/kg, subcutaneous), followed by Meloxicam (1 mg/kg, on 3 consecutive days, subcutaneous) for postoperative analgesia. For icv studies, mice were infused with 1 μl of either vehicle (aCSF; Tocris Bioscience) or α-MSH (1 nmol, R&D systems, Tocris) 2 h before the onset of the dark cycle, and food intake was followed immediately for 24 h.

BrdU experiments

50 mg/kg of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in ~50 μl of sterile saline was injected daily at postnatal days 0, 1, 2 and 3 in the dorsal neck fold of pups. The pups were sacrificed at P7 and the brains processed for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Adult mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Fisher Scientific). Brains from embryos and pups were isolated from non PFA-perfused animals. After dissection, brains were post-fixed for 24 h with 4% PFA, equilibrated in 30% sucrose for 24 h, and sectioned on a cryostat (Leica Biosystems) at 25 μm. Brain sections were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-Pomc precursor (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals), goat anti-Agrp (R&D systems, AF634), chicken anti-GFP (Acris, AP31791PU-N), goat anti-GFP (Abcam, ab6673), rabbit anti-Npy (Abcam, ab30914), rabbit anti-Cart (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc. CA, USA), mouse anti-BrdU (Sigma), goat anti-Tbx3 (A20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-Tbx3 (A303–098A, Bethyl Laboratories), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (5A1E, Cell signaling), goat anti-Iba1 (Abcam ab107519), rabbit anti-GFAP (Dako, Z0334), chicken anti-vimentin (Sigma, Abcam ab24525), Rabbit anti-HA tag (C29F4, Cell signaling). Primary antibodies were incubated at the concentration of 1:500 overnight at 4°C in 0.1M TBS containing gelatin (0.25%) and Triton X100 (0.5%). Sections were washed with 0.1M TBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 0.1 M TBS containing gelatin (0.25%) and Triton X100 (0.5%), using the following secondary antibodies (1:1000) from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories: goat anti-rabbit (Alexa 647), goat anti-chicken (Alexa 488), donkey anti-goat (Alexa 488), and donkey anti-mouse (Alexa 488).

Image analysis

Images were obtained using a BZ-9000 microscope (Keyence) or a Leica SP5 confocal microscope, and automated analysis was performed using Fiji 1.0 (ImageJ) when technically feasible. Manual counts were performed blinded. When anatomically possible, neuronal cell counts were performed on several sections spanning the medial arcuate nucleus and averaged.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Dissected tissues were immediately frozen on dry ice, and RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen). Whole hypothalamus was isolated and immediately frozen on dry ice. To obtain RNA from arcuate nucleus micropunches, freshly dissected whole brains were immersed in RNAlater (AM7021, Thermofisher) for a minimum of 24 h at 4°C. The RNAlater-immersed brains were subsequently cut coronally in 280 μm slices using a vibratome, and the arcuate nucleus was dissected from each slice using a scalpel visually aided by binoculars. RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen). cDNA was generated with reverse transcription QuantiTech reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the following TaqMan probes (ThermoFisher scientific): Hprt (Mm01545399_m1), Ppib (Mm00478295_m1), Npy (Mm03048253_m1), Pomc (Mm00435874_m1), Agrp (Mm00475829_g1), Kisspeptin (Mm03058560_m1), Somatostatin (Mm0043667_m1), Tyrosine hydroxylase (Mm00447557_m1), Ghrh (Mm00439100_m1), Tbx3 (Mm01195726_m1), Pcsk1 (Mm00479023_m1), Pcsk2 (Mm00500981_m1), Pam (Mm01293044_m1), and Cpe (Mm00516341_m1). Target gene expression was normalized to reference genes Hprt or Ppib. Calculations were performed by a comparative method (2−ΔΔ CT).

Primary murine hypothalamic cell cultures

Hypothalami were extracted from Tbx3loxP/loxP mouse fetuses on embryonic day 14 (E14) in ice cold calcium- and magnesium-free HBSS (Life Technologies), digested for 10 min at 37°C with 0.05% trypsin (Life Technologies), washed three times with serum-free MEM supplemented with L-glutamine (2mM) and glucose (25mM), and dispersed in the same medium. Cells were plated on 12-well plates coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) at density 1.5 × 106 per well in MEM supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% horse serum, and 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and glucose (25 mM) without antibiotics. On Day 4, half the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium lacking fetal bovine serum, and containing 10 μM mitotic inhibitor AraC (cytosine-1-β-D-arabinofuranoside, Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit non-neuronal cell proliferation. On Day 6, neurons were infected with a recombinant adenovirus carrying the coding sequence for the recombinase Cre (Ad5-CMV-Cre-eGFP, named Ad-Cre) to delete the loxP-flanked portion of the Tbx3 gene, or with a control virus (Ad5-CMV-eGFP, named Ad-GFP) from Vector Development Laboratory (TX, USA). On Day 7, after 12 h of incubation, virus-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh growth medium. Neurons were further incubated for 48 h to ensure efficient recombination before performing experiments. Cell cytotoxicity was assessed using Pierce LDF Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (#88953, ThermoFisher Scientific).

ChIP-MS

For ChIP experiments followed by mass spectrometry (ChIP-MS), hypothalamic samples from 34 individual mice were pooled together and 5 hypothalami at a time were homogenized in 9 ml of 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. After quenching for 5 min with 125 mM glycine, samples were washed twice with PBS. Pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.3% SDS, 1.7% Triton, 5 mM EDTA pH 8, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl) and the chromatin was sonicated to an average size of 200 bp. After incubation with either a Tbx3 antibody (A303–098A, Bethyl Laboratories Inc.) or an IgG antibody (rabbit IgG 2729S, Cell Signaling Technology), antibody-bait complexes were bound by protein G-coupled agarose beads (Cell signaling technology) and washed three times with wash buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton), once with wash buffer B (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton) and twice with TBS. Beads were incubated for 30 min with elution buffer 1 (2 M Urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 20 μg/ml Trypsin) followed by a second elution with elution buffer 2 (2 M Urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM Chloroacetamide) for 5 min. Both eluates were combined and further incubated over-night at room temperature. Tryptic peptide mixtures were acidified with 1% TFA and desalted with Stage Tips containing 3 layers of C18 reverse phase material and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Peptides were separated on 50‐cm columns packed in-house with ReproSil‐Pur C18‐AQ 1.9 μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH). Liquid chromatography was performed on an EASY‐nLC 1000 ultra‐high‐pressure system coupled through a nanoelectrospray source to a Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded in buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and separated by applying a non-linear gradient of 5–32% buffer B (0.1% formic acid, 80% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min over 100 min. Data acquisition switched between a full scan and 15 data‐dependent MS/MS scans. Full scans were acquired with target values of 3 × 106 charges in the 300–1,650 m/z range. The resolution for full scan MS spectra was set to 60,000 with a maximum injection time of 20 ms. The fifteen most abundant ions were sequentially isolated with an ion target value of 1 × 105 and an isolation window of 1.4 m/z. Fragmentation of precursor ions was performed by higher energy C-trap dissociation with a normalized collision energy of 27 eV. Resolution for HCD spectra was set to 15,000 with maximum ion injection time of 60 ms. Multiple sequencing of peptides was minimized by excluding the selected peptide candidates for 25 s. Raw mass spectrometry data were analyzed with MaxQuant (version 1.5.6.7)58 and Perseus (version 1.5.4.2) software packages. Peak lists were searched against the mouse Uniprot FASTA database (2015_08 release) combined with 262 common contaminants by the integrated Andromeda search engine59. False discovery rate was set to 1% for both peptides (minimum length of 7 amino acids) and proteins. ‘Match between runs’ (MBR) with a maximum time difference of 0.7 min was enabled. For a gain in peptide identification, MS spectra were matched to a library of Tbx3 ChIP MS data derived from murine neuronal progenitor cells. Relative protein amounts were determined by the MaxLFQ algorithm60, with a minimum ratio count of two. Missing values were imputed from a normal distribution applying a width of 0.2 and a downshift of 1.8 standard deviations. Significant outliers were defined by permutation-controlled Student’s t-test (FDR < 0.05, s0 =1) comparing triplicate ChIP-MS samples for each antibody. See additional information on the Reporting Summary.

RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed in primary neurons isolated from Tbx3loxP/loxP mice and treated with Ad-Cre or Ad-GFP viruses. Sequencing was performed in three independent neuronal isolations totaling 9 Ad-GFP- and 11 Ad-Cre-treated independent samples. Prior to library preparation, RNA integrity was determined with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano Kit. All samples had RNA integrity number (RIN) values greater than 7. One μg of total RNA per sample was used for library preparation. Library construction was performed as described in the Low Throughput protocol of the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Guide (Illumina) in an automated manner, using the Bravo Automated Liquid Handling Platform (Agilent). cDNA libraries were assessed for quality and quantity with the Lab Chip GX (Perkin Elmer) and the Quant-iTPicoGreendsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies). cDNA libraries were multiplexed and sequenced as 100 bp paired-end runs on an Illumina HiSeq2500 platform. About 8 Gb of sequence per sample were obtained. The GEM mapper61 (v 1.7.1) with modified parameter settings (mismatches = 0.04, min-decoded-strata = 2) was used for split-read alignment against the mouse genome assembly mm9 (NCBI37) and UCSC knownGene annotation. Duplicate reads were removed. To quantify the number of reads mapping to annotated genes, we used HTseq-count62 (v0.6.0). We normalized read counts to correct for possibly varying sequencing depths across samples using the R/Bioconducter package DESeq263 and excluded genes with low expression levels (mean read count < 25) from the analysis. We combined RNA-Seq data of the three independent neuronal isolations. As the independence of the three neuronal isolations might introduce batch effects, we applied surrogate variable analysis implemented in the R package sva64 to remove them. Gene expression levels between the two virus treatments were compared using DESeq2. We chose 0.001 to be the p value cut-off after FDR correction (Benjamini-Hochberg). To obtain genes selectively expressed in Pomc neurons, we used the single cell sequencing data set previously published7 and selected the n14 (Pomc/Ttr), n15 (Pomc/Anxa2) and n21 (Pomc/Glipr1) neuronal clusters as gene expression references. We chose all genes that had a normalized expression value above a noise level of 4.5. Additionally, we required the selected genes to be expressed in at least 10% of the 1191 samples in our Pomc neuron reference. We intersected the genes differentially expressed in our Tbx3 AdCree65 to test these genes against GO biological process terms66. After the overrepresentation test we excluded GO Terms whose gene list overlapped the list of another term completely. All calculations were performed using R (v3.4.3).

Drosophila

The Drosophila melanogaster neuronal Geneswitch Gal4 driver line (Elav-Gal4GS) was obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC43642). GeneSwitch drivers can be activated by progesterone steroids67. The RNAi transgenic lines for the Tbx3 homolog gene omb (line 1, UAS-ombRNAi-C4, line 2, UAS-ombRNAi-C1) were described in68. Elav-Gal4GS virgin females and 15 omb RNAi transgenic males were crossed in big-fly food vials for 24 h, and around 600 F1 embryos were seeded and kept at 25°C for growth on standard cornmeal media (12:12 Light:Dark cycle; 60–70% humidity). After eclosion (24 h), 50 young adult male and virgin females were fed on small fresh drug-food vials (mifepristone, 200μM) and control food vials (ethanol, same as mifepristone dissolved volume) respectively for 6 d. At least eight technical replicates (5 flies each) were collected for body fat content measurement (TAG value normalized to protein value), based on the coupled-colorimetric assay (triglyceride, Pointe Scientific (T7532))69 and bicinchoninic acid assay (protein, Pierce, Thermo Scientific; Cat. #: 23225)70,71: 5 adult male flies per technical replicate, 600 μL homogenization buffer (0,05% Tween-20 in water) and 5mm metal beads (QIAGEN, Cat. #: 69989) were homogenized in 1.2 ml collecting tubes (Qiagen, Cat. #: 19560; Caps: Cat. #: 19566) using a tissue lyser II (QIAGEN, 85300), and immediately incubated at 70 °C (water bath) for 5 min. The fly homogenates were spinned down at 5000 rpm for 3min. 2 × 50 μL supernatant of each replicate, TAG standards solutions (Biomol, Cat. #: Cay-10010509; 0, 5.5, 11, 22, 33, 44 μg in 50 μL homogenization buffer), BSA (Bovine serum albumin), and protein standard samples (0, 25, 125, 250, 500, 750 mg/mL) were measured at 500nm (for TAG) and 570nm (for protein). The assay kit for the colorimetric assay was from Pointe Scientific (T7532). Immunostainings were carried in 5 days-old adult male flies (omb-Gal4>UAS-GFP transgenic line72) using a method reported previously73. Brains were dissected in cold PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. Brain tissues were incubated with 0.25% Triton® X-100 in PBS (0.25% PBST) at RT for 25min and blocked with 1% BSA & 3% normal goat serum (NGS) in 0.25% PBST for 1h at RT with mild rotations. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Bruchpilot (nc82, 1:50) (nc82, deposited to the DSHB by Buchner, E. (DSHB Hybridoma Product nc82)), chicken anti-GFP (1:1000) (Acris, AP31791PU-N), and rabbit anti-Omb serum (1:1000)74. The following secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used: donkey anti-mouse (Alexa 568), goat antirabbit (Alexa 647), and goat anti-chicken (Alexa 488) were used. Secondary antibodies were incubated at RT for 2 h. After 5 × 10min washing with 0.25% PBST and 1 x overnight washing with PBS, tissues were mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides and cover slipped for image analysis. Images were obtained with Leica SP8 confocal system (20x air objective) and processed with Fiji 1.0 (ImageJ).

Human embryonic stem cells

The human H9 ESC line was purchased from WiCell. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C on irradiated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; CF-1 MEF 4M IRR; GLOBALSTEM) in DMEM KO medium (Cat # 10829018; ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 15% knockout Serum Replacement (Cat # 10828028; ThermoFisher Scientific), 0.1 mM MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Cat # 11140050; ThermoFisher Scientific), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Cat # 35050061; ThermoFisher Scientific), 0.06 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Cat # 21985023; ThermoFisher Scientific), FGF-Basic (AA 1 – 155), (20 ng/ml media; Cat # PHG0263; ThermoFisher Scientific), and 10 mM Rock inhibitor (Cat # S1049; Selleckchem). Cells were passaged using Accutase (Cat # 00–4555-56; ThermoFisher Scientific). For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of Tbx3, pCas9_GFP was obtained from Addgene (Kiran Musunuru; # 44719). As previously published, the GFP was replaced by a truncated CD4 gene from the GeneArt® CRISPR Nuclease OFP Vector (ThermoFisher Scientific) by GenScript using CloneEZ® seamless cloning technology resulting in vector pCas9_CD475. The full vector sequence of pCas9_CD4 is given in Supplementary Table 4. The guide RNA sequence 5’-TCATGGCGAAGTCCGGCGCC-3’ was obtained using Optimized CRISPR Design (MIT; http://crispr.mit.edu/). Cloning of the gRNA into pGS-U6-gRNA was performed by GenScript. 800,000 human ESC were collected and mixed in nucleofection buffer (Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 2; Cat # VPH-5022) with gRNA and pCas9_CD4 plasmids (2.5 μg each). Nucleofection was performed in an Amaxa Nucleofector II (Program A-023) with the Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were plated on MEFs for 2 d for recovery, followed by purification of transfected cells by positive selection of CD4-expressing cells using human CD4 MicroBeads (Cat # 130–045-101; MS Column, Cat # 130–042-20; MACS Miltenyi Biotec) and re-plated at clonal density in 10 cm2 tissue culture plates on MEFs. After 7 – 12 d, ESC colonies were picked into 96-well plates and, 4 – 5 d later, split 1:2 (one well for genomic DNA extraction followed by sequence analysis as described below, and one well for amplification of clones and further analysis and freezing if indicated). For genomic DNA extraction and PCR analysis, genomic DNA was extracted using HotShot buffer following a published protocol76. The DNA region of interest was PCR-amplified with the following primers: 5’-GAGAGCGCCGCCGCGCCGT-3’ and 5’-GCTGCGGACTTGTCCCCGGCTGGA-3’76. Sequences were generated by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen). Sequence analysis was performed to identify clones carrying mutations resulting in TBX3 KO. Positive clones were amplified, and genomic DNA was extracted using Gentra Puregene Core Kit A (Qiagen). Topo TA Cloning Kit for sequencing (Cat # K457501; ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to determine zygosity of TBX3 KO with the following primers: 5’- CACCTTGGGGTCGTCCTCCA-3’ and 5’- CGCAAGGCACAAGGACGGTCA-3’. G-band karyotyping analysis was done by Cell Line Genetics. Chromosome analysis was performed on 20 cells per cell line.

Differentiation of human ESC into Arcuate-like neurons

Human ESC were differentiated into hypothalamic arcuate-like neurons were derived from human ESC using a previously published protocol33–35. H9 cells were plated on Matrigel (Cat # 08–774-552; ThermoFisher Scientific)-coated dishes at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2) in human ESC medium as described above supplemented with bFGF and Rock inhibitor. Cell density was observed after 24 h. If the cells were not at 100 % confluency yet, medium was aspirated and replaced with ESC medium with bFGF and Rock inhibitor for another 24 h. Once cells reached 100 % confluency, differentiation was initiated. 10μM SB 431542 (Cat # S1067; Selleckchem) and 2.5 μM LDN 193189 (Cat # S2618; Selleckchem) were used from Day 1 to Day 8 to inhibit TGFβ and BMP signaling in order to promote neuronal differentiation from human ES cells77. 100 ng/ml SHH (Cat # 248-BD; (R&D Systems) and 2 μM Purmorphamine (PM; Cat # S3042; Selleckchem) were added from Days 1 to 8 to induce ventral brain development and NKX2.1 expression. Cells were cultured on Day 1 to 4 in ESC medium, from Day 5 to 8 the medium was switched stepwise from ESC medium to N2 medium (3:1, 1:1, 1:3). N2 medium (500 ml) consists of 485 ml DMEM/F12 (Cat # 11322; ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 5 ml MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Cat # 11140050; ThermoFisher Scientific), 5 ml of a 16 % glucose solution and 5 ml N2 (Cat # 1370701; ThermoFisher Scientific). Ascorbic acid (Cat # A0278; Sigma-Aldrich) was added at just prior use at a final concentration of 200 nM. From Day 9 on cells were cultured in N2-B27 medium consisting of 475 ml DMEM/F12 (Cat # 11322; ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 5 ml MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Cat # 11140050; ThermoFisher Scientific), 5 ml of a 16 % glucose solution, 5 ml N2 (Cat # 1370701; ThermoFisher Scientific) and 10 ml B27 (Cat # 12587010; ThermoFisher Scientific). Ascorbic acid (Cat # A0278; Sigma-Aldrich) was added at just prior use at a final concentration of 200 nM. Inhibition of Notch signaling by 10 μM DAPT (Cat # S2215; Selleckchem) was performed from Days 9 to 12. Nkx2.1+ progenitors were collected and re-plated on extracellular matrix (poly-L-ornithine [Cat # A-004-C; Millipore] and laminin [Cat # 23017015; ThermoFisher Scientific]) to enhance the attachment and differentiation of neuron progenitors. The Notch inhibitor DAPT was used to inhibit the proliferation of progenitor cells and promote further neuronal differentiation78,79. The neurotrophic factor BDNF (20 ng/ml; Cat # 450–02; PeproTech) was introduced following DAPT treatment to improve the survival, differentiation and maturation of these neurons. For RT-PCR analyses, Cells at Day 0, Day 12 and Day 27 of differentiation were homogenized in Trizol® Reagent (Cat # 15596026; ThermoFisher Scientific) and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Cat # 74034; Qiagen) with on-column DNaseI (Cat # 79254; Qiagen) treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination and stored at −80°C until further processing. A total of 500 ng of total RNA was used for reverse transcription utilizing the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat # 04897030001; Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN) using a mixture of Anchored Oligo(dT)18 and Random Hexamer primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed with a Light-Cycler® 480 (Roche Diagnostics) using SYBR Green in a total volume of 10 μl with 1 μl of template, 1 μl of forward and reverse primers (10 μM) and 5 μl of SYBR Green I Master-Mix (Cat # 04707516001; Roche Diagnostic). Reactions included an initial cycle at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for 5 sec, and extension at 72°C for 15 sec. Crossing points were determined by Light-Cycler 480 software using the second derivative maximum technique. Relative expression data were calculated by the delta-delta Ct method, with normalization of the raw data to TBP. Quantitative PCR was performed to determine the mRNA level of TBX3, POMC, TUBB3, PCSK1, NKX2.1. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blot analysis

Human ESC (H9) and hypothalamic arcuate-like neurons (Day 27 of differentiation) were washed with DPBS and lysed in RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Cat # 89900; ThermoFisher Scientific) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Cat # 78442; ThermoFisher Scientific), incubated at 4°C for 15 min and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Fifteen μg of total protein from each extract were loaded on a 4–12% gradient Bis-Tris gel (Cat # NP0335BOX; ThermoFisher Scientific) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane using iBlot 2 Dry Blotting System (ThermoFisher Scientific). The membrane was blocked for 1 h at room temperature with SuperBlock T20 (TBS) Blocking Buffer (Cat # 37536; ThermoFisher Scientific) and then incubated with primary antibody against TBX3 (1:100; Cat # ab99302; Abcam) overnight at 4°C, washed three times using TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (Cat # 1706531; BioRad), and incubated with secondary antibody anti-rabbit HRP (1:10,000; Cat # 7074S; Cell Signaling) for 1 h at room temperature. Specific bands were then detected by ECL analysis using SuperSigna West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Cat # 34577; ThermoFisher Scientific). An antibody against beta-actin (1:1,000; Cat # ab8226; Abcam), using anti-mouse HRP (1:10,000; Cat # 7076S; Cell Signaling) as a secondary antibody, was used as loading control. Validation of the goat anti-Tbx3 antibody (A20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed using Tbx3-deficient embryos (E13.5) kindly provided by Dr. A. Kispert80. Proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL USA) 1 mM phenyl-methane-sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Proteins were transferred on nitrocellulose membranes using a Trans Blot Turbo transfer apparatus (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), stained with primary antibody goat anti-Tbx3 (1.500) and a secondary antibody anti-goat HRP (1.1000). Detection was carried out on a LiCor Odyssey instrument (Lincoln, NE, USA, software Image studio 2.0), using ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). See additional information on the Reporting Summary.

Tbx3-focused single-cell RNA sequencing analysis

Data for the scRNA-seq analysis were obtained from GEO Accession codes GSE90806 and GSE93374 7. The data matrix comprised of 21,086 cells and 22,802 genes generated from the Arcuate-median eminence (Arc-ME) of the mouse hypothalamus by Campbell et al7. We used Seurat software81 to perform clustering analysis. We identified the 2,250 most-variable genes across the entire dataset controlling for the known relationship between mean expression and variance. After scaling and centering the data along each variable gene, we performed principal component analysis, and identified 25-significant PCs for downstream analysis that were used to identify 20 clusters. Similar to those identified by Campbell et al7, we identified a total of 13,079 neurons and 8,007 non-neuronal cells. We further used the neuronal identities assigned by the authors for clustering the neurons into their respective neuronal clusters. For differential expression between cell type clusters, we used the negative binomial test, a likelihood ratio test assuming an underlying negative binomial distribution for UMI-based datasets.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0a). For each experiment, slides were numerically coded to obscure the treatment group. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test, 1-way ANOVA, or 2-way ANOVA, followed by appropriate post hoc test as indicated in the legends, and linear regression when appropriate. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. See additional information on the Reporting Summary.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper [and its supplementary information files]. The RNA-seq database generated in our paper has been made publicly available: GEO accession number: GSE119883.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements