Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the Lifestyle Enhancement for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Program (LEAP), a novel parent behavior management training program that promotes physical activity (PA) and positive health behaviors and is enhanced with mobile health technology (Garmin) and a social media (Facebook) curriculum for parents of children with ADHD.

Methods

The study included parents of children ages 5–10 years diagnosed with ADHD who did not engage in the recommended >60 min/day of moderate to vigorous PA based on parent report at baseline. Parents participated in the 8-week LEAP group and joined a private Facebook group. Children and one parent wore wrist-worn Garmin activity trackers daily. Parents completed the Treatment Adherence Inventory, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, and participated in a structured focus group about their experiences with various aspects of the program.

Results

Of 31 children enrolled, 51.5% had ADHD combined presentation, 36.3% with ADHD, predominately inattentive presentation, and 12.1% had unspecified ADHD (age 5–10; M = 7.6; 48.4% female). Parents attended an average of 86% of group sessions. On average, parents wore their Garmins for 5.1 days/week (average step count 7,092 steps/day) and children for 6.0 days/week (average step count 9,823 steps/day). Overall, parents and children were adherent to intervention components and acceptability of the program was high.

Conclusions

Findings indicate that the LEAP program is an acceptable and feasible intervention model for promoting PA among parents and their children with ADHD. Implications for improving ADHD symptoms and enhancing evidence-based parent training programs are discussed.

Keywords: attention, health behavior, hyperactivity and ADHD, parenting, pilot/feasibility trial

Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children 6 years and older participate in 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) on most days of the week (Korioth, 2020). Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are less likely to get recommended amounts of PA and are more likely to engage in sedentary behaviors such as screen time, compared with peers without ADHD (Tandon et al., 2019). In fact, results of the National Survey of Child Health found that only one-third of children with ADHD engaged in PA for at least 20 min every day, which is well below recommendations (Tandon et al., 2019). Although hyperactivity would seem to increase PA, children with ADHD encounter barriers to adequate PA and sports participation that is related to their diagnosis (e.g., disruptive behavior, noncompliance, loss of interest, etc.). Furthermore, overfocus on screens, which provide instant gratification, is a growing problem as children with ADHD get older and increases sedentary behaviors (Nikkelen et al., 2014). Sleep problems are also common for children with ADHD (Owens et al., 2013), and appear to be interrelated with PA and screen time in children with ADHD (Hong et al., 2020).

Behavior management training (BMT) interventions have shown to be effective in modifying child behavior and improving ADHD functional outcomes by teaching parent-implemented behavior change strategies such as praise, incentives, and consequences (Pfiffner & Haack, 2014). Such programs focus primarily on reducing noncompliance and have not historically targeted health behaviors that are related to ADHD symptoms such as PA, screen-based media use, and sleep. There is a need to develop and evaluate innovative, generalizable intervention strategies as an alternative or adjunct to existing treatments to improve longer-term developmental and health trajectories of children with ADHD (Halperin & Healey, 2011).

PA is associated with improvements in ADHD symptoms and benefits for the academic and social functioning for children with ADHD (Hoza et al., 2016). PA is also positively associated with improvements in cognitive performance, such as executive functioning skills (Gapin & Etnier, 2010), attention problems (Medina et al., 2010; Verret et al., 2012), and inhibitory control (Pontifex et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013) that are typically compromised in children with ADHD (Halperin et al., 2014). A randomized trial of a school-based PA-intervention in an ADHD-risk sample showed moderate effect sizes on parent-reported measures (ADHD symptoms, mood, and peer functioning) and a subset of teacher-reported measures across 12 weeks, indicating lasting effects of the intervention throughout the day (Hoza et al., 2015). However, prior interventions and studies have focused on acute periods of PA (e.g., a 20-min active playgroup), and we know little about how to help families of children with ADHD make lifestyle changes that will increase PA and related health behaviors in the long term.

Sleep problems are experienced by nearly 85% (Yürümez & Kılıç, 2016) of children with ADHD and these problems are associated with more severe ADHD symptoms and lower child and family functioning (Sung et al., 2008). A meta-analysis on sleep in children with ADHD found these children experience higher bedtime resistance, more sleep onset difficulties, night awakenings, difficulties with morning awakenings, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness (Cortese et al., 2009). The prevalent use of screen-based media use also exacerbates ADHD symptoms and functional problems (Nikkelen et al., 2014). In a recent study, children with ADHD reported more than 4.5 hr with screen-based media on school days compared with 2 hr of screen time in children without ADHD (Thoma et al., 2020). Therefore, management of ADHD symptoms involves a broad focus on health behaviors by targeting sleep health and screen-based media use in addition to PA.

We developed and piloted the Lifestyle Enhancement for ADHD Program (LEAP), which was adapted from an existing BMT curriculum (Barkley, 2013) with a primary goal to increase child PA and an added focus on sleep behaviors, screen use, and parent mindfulness. Emerging research on mindful parenting interventions supports positive effects for reducing parental stress and mental health problems (stress and depression) and improvements in child outcomes (Emerson et al., 2021), with a study noting fewer parent-reported behavior problems, attention problems, and ADHD symptomatology among children whose parents participated in a mindfulness-based intervention (Neece, 2014; van der Oord et al., 2012).

In addition to the enhanced parent training program, we employed two novel change-supporting strategies to increase effectiveness and engagement (Atienza & Patrick, 2011). First, we incorporated the use of mobile health (mHealth) technology (wearable activity tracker, cell phone application and texting) to encourage parents and children to monitor, set goals, and communicate about PA. Second, we included a social media component (Facebook group) to increase parent engagement, motivation, and parent social support. The social media group provides a format for reminders, social reinforcement, and problem solving around parents’ efforts to increase PA. These mHealth technology approaches (wearable activity tracker, texting, social media) have been successfully used to promote PA in adolescents with ADHD (Schoenfelder et al., 2017), adolescent survivors of cancer (Mendoza et al., 2017), and non-clinical populations (Pumper et al., 2015), but have not been used to support parents or young children with ADHD. The present study evaluates the feasibility and acceptability of this novel, technology-integrated health and behavior intervention intended to improve PA, health behaviors, and ultimately ADHD symptoms and functioning in children with ADHD.

Methods

LEAP Description

LEAP consists of three components: (a) an enhanced 8-week, group based BMT curriculum, (b) parent and child use of a Garmin wrist-worn activity tracker accompanied by personalized goal-setting, and (c) parent participation in a private Facebook group to promote social support, positive parenting, and engagement around PA.

The enhanced 8-week group LEAP curriculum was based on an existing evidence-based BMT model, Barkley’s Defiant Children (Barkley, 2013) curriculum, with integrated content specifically focused on promoting and addressing barriers to PA, sleep, and screen time limits. For example, group leaders discussed challenges encountered with PA and overcoming barriers, using incentives to promote healthy behaviors, the role of bedtime routines/sleep, and goal-setting for future/strategies for sustainability. Each session started with a parent mindfulness exercise, and parents were asked to practice the exercises weekly. Sessions also included family discussions, troubleshooting of home practices, and role plays. Table I presents a sampling of session content, highlighting the unique aspects of the LEAP curriculum compared with standard BMT. A licensed psychologist and psychology trainees led each parent group in an outpatient hospital-based psychiatry clinic. Groups met for 90 min weekly, and 30-min make-up sessions were offered for families who missed a group session.

Table I.

Behavior Management Training (BMT) Standard and Lifestyle Enhancement for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Program (LEAP)-Sample of Sessions 1–8

| BMT-standard Barkley’s defiant children | LEAP |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy instruction | Session | Unique strategy instruction | Unique targets |

|

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

We created a private Facebook group for each LEAP group. Group coleaders posted at least twice weekly on the Facebook group page (M = 3.58; SD = 4.58), interacted with parents in the group, and screened daily content posted by parents. The initial two LEAP groups also received weekly digital badges for meeting their weekly activity goals (e.g., most steps for an individual) as well as for social interactions (e.g., “liking” other’s posts) or improving/approaching PA goals (e.g., most improved). The badges were replaced with more information and resources relevant to that week’s skill or topic for subsequent groups, based on parent feedback.

Each child participant received a Garmin vivofit jr. Although multiple caregivers could participate in LEAP, only one caregiver per child received the Garmin vivofit3 at the first session to track their step counts. Parents and children were supported in setting personalized goals of 10% above their previous week’s step count via text messages. If a weekly goal was not met, their step count goal remained the same. Parents participating in LEAP were encouraged to work toward their own PA goals to provide them with tools for adopting and sustaining healthy and active lifestyles for themselves and their families.

Recruitment and Screening Process

The Seattle Children‘s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Families were recruited from an outpatient psychiatry clinic via clinician referrals, study fliers distributed to local primary care clinics, and social media (Facebook) advertisements. Inclusion criteria included: (a) children between 5 and 10 years of age and (b) having an ADHD diagnosis. Exclusion criteria included: (a) children who met PA guidelines (>60 min/day for 5 days/week of MVPA) based on parent report, (b) parents who had participated in a structured BMT program in the past 2 years, (c) children who met diagnostic criteria for other psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorder, Depression, Intellectual Disability) that could interfere with the intervention uptake, and (d) any physical or medical restriction on PA. Children who were receiving stimulant medication and were on a stable dose (in the past 30-days) since the time of screening were included.

Families who met eligibility criteria were invited for a diagnostic screening evaluation with the Schedule for Affective Disorders for School-Aged Children Present and Lifetime Version completed by a licensed psychologist (Kaufman et al., 1997). Families were eligible for group participation if the child met criteria for ADHD and had a clinician-rated score between 4 and 6 on the Clinical Global Impression—Severity Scale (Guy, 1976).

Measures and Data Collection

Parents completed an online demographic survey before starting the first LEAP group. Parents received incentives for completing all study assessments in the following amounts: $15 for screening visit, $25 for week 5 measures, $50 for week 9 (posttest) measures, and $15 for participating in a focus group after the completion of LEAP.

Feasibility

We assessed feasibility by demand through inquiry and enrollment rates and participation through attrition and adherence with the intervention (group attendance, percentage of days wearing the Garmin, participation in the Facebook group) and study procedures (screening, follow-up assessment). We assessed the Garmin component’s feasibility through wear time recorded in the Garmin software application. We assessed participation in the Facebook group via “likes,” views, comments, and wall posts from participants in the Facebook group (Pumper et al., 2015).

Our feasibility targets were established prior to the initiation of the first intervention group and included: (a) <60% of parents miss more than two consecutive group sessions; (b) >80% of parents join the Facebook group; (c) >60% of caregivers wear their Garmin activity trackers at least 3 days/week throughout the study; (d) >60% of children wear their Garmin activity trackers at least three days/week throughout the study; and (e) >75% of participants retained for posttest measurement at the end of the study, regardless of adherence to the intervention.

Acceptability

Postintervention, parents rated their satisfaction with LEAP using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (Nguyen et al., 1983) on which they rate the program using a 1-4 scale on eight dimensions (e.g., quality, needs met, etc.).The coefficient alpha for the CSQ-8 is .93, indicating that it possesses a high degree of internal consistency. Parents also completed the Treatment Adherence Inventory (TAI), which was adapted from a previous study (Schoenfelder et al., 2019) and is used for descriptive engagement measurement. The TAI asked parents to rate their use of 23 program skills (e.g., “When your child did something you asked them to do, did you praise in the moment specifically and enthusiastically?”) and their level of engagement in the program (e.g., “How able to become involved in treatment were you?”), with a 1–5 Likert-scale with choices ranging from (Almost Never) to (Almost Always). Perceived helpfulness of each program skill (e.g., “How helpful was praise or catch them in the act?”) was reported on a 1–5 scale from (Not Very Helpful) to (Extremely Helpful), and an open-ended section was provided for treatment improvement suggestions. Several TAI items were adapted to ask parents about skills specific to LEAP (e.g., “Did you spend daily active time with your child?”) and to assess perceived helpfulness of each LEAP skill (e.g., How helpful was daily active time?”).

After study completion, parents completed a 90-min focus group with other participating parents. Questions solicited their LEAP experiences, including using the Garmin devices, study measures, Facebook group, and overall study participation (e.g., What was your impression of this group’s focus on increasing PA/health behaviors for children with ADHD? Tell us your reactions to wearing the Garmin and having weekly Garmin goals, etc.). The focus groups were audio-recorded and underwent qualitative coding, described below.

Our acceptability goal was to have >80% of parents find the intervention acceptable as measured by focus group interviews and standardized posttest rating scales.

Analysis Plan

Feasibility and acceptability data analysis was largely descriptive and exploratory. We focused on parameter estimates instead of formal hypothesis testing, using means, medians, and SDs for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables using 95% exact confidence intervals (Clopper & Pearson, 1934).

Exploratory content analysis was used to examine Facebook data for themes related to PA and ADHD, following procedures from a previous study (Pumper et al., 2015). Two independent coders completed the Facebook content analysis and achieved agreement on 94% of posts/comments analyzed using a priori codes. Focus group recordings were transcribed and analyzed for themes using a constant comparative method approach, which involved comparing similarities and differences in the data to identify patterns across focus group interviews (Sandelowski, 1995). Coders individually identified and coded interviews after reviewing transcripts using a priori codes. If a quote did not fit the definition of any a priori codes, coders consulted with the study team and a new code was created if appropriate. Independent coders met weekly to identify coding discrepancies, which were resolved through discussion. An excel document was used to collate quotes from the focus groups and track inter-rater agreement across qualitative interviews. Coders achieved agreement on 99% of qualitative categories and themes coded.

Results

Participant Recruitment and Retention

Across two separate 3-month enrollment periods, 88 families expressed initial interest to participate in LEAP via email or telephone (see Figure 1 for study enrollment). Of 55 parent–child dyads determined to be eligible by phone screen, 37 completed the in-person screening visit and 35 screened in. Retention was high among those who attended the baseline screening visit with two drop-outs before the intervention started and two midway through treatment. Thirty-three parent–child dyads initiated the intervention, and 31 parent–child dyads completed the program. We completed four LEAP groups (each with N = 8 or 9 families), two groups ran fall to early winter and two groups ran winter to early spring.

Figure 1.

Lifestyle Enhancement for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Program study enrollment.

Participating children were majority male (51.6%); age ranged from 5 to 10 years old (Mage = 7.63). See Table II for additional child demographic information. Common comorbid diagnoses for children in our study included oppositional defiant disorder (N = 7), separation anxiety disorder (N = 4), specific phobia (N = 1), generalized anxiety disorder (N = 4), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (N = 1).

Table II.

Demographics

| Characteristics (N = 33) | |

|---|---|

| Mean child age (SD) | 7.6 (1.4) |

| Female, N (%) | 16 (48.4%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino, N (%) | 28 (84.8%) |

| White/Caucasian | 20 (60.6%) |

| Black or African American | 2 (6.1%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.0%) |

| Two or more races | 5 (15.2%) |

| Hispanic/Latino, N (%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| White/Caucasian | 2 (6.1%) |

| Two or more races | 1 (3.0%) |

| Race not reported, N (%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Annual household income, N (%) | |

| $30,000–$70,000 | 7 (21.2%) |

| $70,000–$150,000 | 9 (27.3%) |

| Over $150,000 | 17 (51.2%) |

| Parent education level, N (%) | |

| Completed High School | 2 (6.1%) |

| Completed college or university | 13 (39.4%) |

| Completed graduate school or professional degree | 17 (51.5%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) |

| ADHD diagnosis | |

| ADHD inattentive presentation, N (%) | 12 (36.3%) |

| ADHD combined presentation, N (%) | 17 (51.5%) |

| ADHD hyperactivity-impulsive presentation, N (%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| ADHD not otherwise specified, N (%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Taking medications for ADHD at pre-test | |

| ADHD medication treatment | 30% |

| BMI percentiles, N (%)a | |

| Healthy Weight | 27 (82.0%) |

| Underweight | 1 (3.0%) |

| Overweight | 3 (9.0%) |

| Obese | 2 (6.0%) |

Used the child’s height and weight at baseline to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI) using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Child and Teen BMI calculator (BMI = weight in kilograms/square of height in meters).

Feasibility

Retention was high, with 31 out of 33 caregivers who attended the first group session completing the program. Parents attended an average of 85.8% (6.9 out of 8 sessions) of group sessions and 93.2% (7.5 out of 8 sessions) of overall sessions including make-up sessions. Forty-six percent of families attended at least one make-up session. All parents completed pretest measures and 90.9% completed the posttest measures.

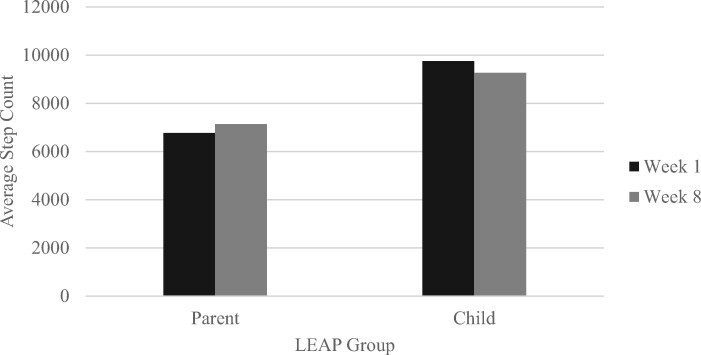

Parents wore their provided Garmin devices to self-monitor their PA on an average of 5.1 days/week over the course of the study. Child participants wore the devices an average of 6.0 days/week. Children had an average daily step count of 9,823 over an average wear span of 55.4 days, whereas parents had an average daily step count of 7,092 over an average wear span of 54.9 days. The average daily step count from weeks 1 to 8 for parents and children who participated in LEAP is summarized in Figure 2. Mean parent group steps ranged from 5,824 to 8,012 steps across the intervention period. Mean child group steps ranged from 8,586 to 10,952 steps across the intervention period. Though our sample size was too small to detect significant differences in average step count from weeks 1 to 8, results indicate a slight increase in average daily step count for parents by 369 steps. Children with ADHD had a decrease in average daily step count from weeks 1 to 8 by 484 steps.

Figure 2.

Average step count across Lifestyle Enhancement for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Program groups.

Regarding Facebook, 100% of families remained in the Facebook group for the duration of LEAP. A total of 259 posts or comments were created by 93% of parents across all LEAP parent groups (N = 29). Each parent made an average of eight posts or comments in the Facebook Group throughout the duration of LEAP (M = 8.35). Forty-four percent of parents’ posts related to community building and resource sharing categories (N = 116). Twenty-two percent of posts were about PA (N = 58), 8% of posts were about limiting screen time (N = 21), 8% (N = 20) about Garmin use, and 4% (N = 11) about sleep. Fifty-four percent (N = 54) of the health behavior posts and comments (PA, limiting screen time, Garmin, healthy sleep) posted by parents in the LEAP group received at least one like (68 likes in total). Parents commonly shared ways to stay active, as well as challenges with health behaviors and skills discussed in group. For example, one parent posted, “My son has no interest in anything other than the iPad. We have tried getting him to try all different activities with no luck. We have limited the kid’s iPad use to weekends only but I’m wondering if we need to take them away completely to see what happens.” Several parents also shared their successes with the group skills: “My daughter is loving the new system of us providing her reward tickets for behaviors that we are working on, as well as moments that we catch her in the act [praise]. I’m hopeful the momentum will continue from both ends and she does not lose excitement. I will put that on me as my challenge to use my creativity and positive fun parenting side to keep her incentivized with this new system we are rolling out in our household.”

Acceptability

The average total CSQ-8 score was 25.12 (SD = 10.06) out of a possible total score of 32, with higher values indicating higher parent satisfaction. All respondents responded in the affirmative when asked if they received the kind of service they wanted, would recommend the program, and would participate again in the program. TAI results are shown in Figure 3. Overall, participating families found the health behavior content to range between “somewhat helpful” and “quite helpful.” The highest rated skills were having a consistent sleep routine, setting screen time limits, and wearing the Garmin device. The lowest rated skills in LEAP were the mindfulness skills learned in group and participation in the Facebook group content.

Figure 3.

Postintervention treatment adherence index results for standard behavior management training and unique Lifestyle Enhancement for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Program targets.

Qualitative Focus Group Data

Qualitative focus group data universally indicated positive experiences with the LEAP groups, including the PA components. For example, a mother described LEAP as “icing on the cake because I knew exercise was going to be incorporated on a day to day basis. I saw the big picture of how this was changing him, me, and us together. So, that was helpful.” Similarly, several parents described benefits derived from their “special active playtime” and in using the Garmin as a reminder to engage in PA with their child. For instance, a mother reported, “as far as the Garmin [for] me, it was beneficial to see the parent–child relationship, because it made me think, he is home from school and I have this to do, but now, I need to get some activity with him, and it needs to be exercise. So that drew us closer together.” Parents also described changes in their routine to facilitate more opportunities to increase their child’s and their own PA (e.g., walking children to school).

The most frequent qualitative feedback about LEAP from parents focused on wanting more technical support to learn about the Garmin features (e.g., set reminders or alarms) and synchronizing with their smartphones. Secondly, parents also shared ideas on promoting greater interest and engagement on Facebook (e.g., include research findings on ADHD and PA and sleep, share books/resources, etc.).

LEAP Adaptations

Program improvements and adaptations were made to the LEAP intervention manual, procedures, and materials based on qualitative feedback from parents. For example, to promote greater caregiver engagement with the Garmin devices, visual guides were developed to help caregivers set up devices, address common technical issues, and use other device functions (e.g., sleep monitoring, assigning chores, awarding tokens). We also began visually presenting and discussing the past week’s average child and adult step counts at the beginning of each group session. Parents asked for more information about how ADHD affects their child’s functioning in different areas (e.g., motivation, sleep problems) and how this related to parenting strategies (e.g., rewards, sleep plans). We revised the LEAP handouts for families to better depict these concepts.

We also made stakeholder-informed modifications to the Facebook group procedures to make it more engaging for families. Parents expressed they did not find the digital badges (e.g., “most improved” steps award) to be reinforcing. Therefore, we removed this from the protocol and increased encouragement by Facebook group moderators, such as “liking” and commenting on discussion posts. Additionally, parents expressed a desire for more scientific/parent education content in the Facebook group. Therefore, we supplemented discussion posts with links to psychoeducational materials (e.g., books on lifestyle behaviors and ADHD, research articles, evidence-based YouTube videos). We also made efforts to improve the engagement with discussion posts by tailoring them to questions or points brought up by parents during that week’s LEAP group. The average total CSQ score for the two groups completed before these changes (M = 3.42) was comparable to those of the two groups completed after the changes (M = 3.72).

Discussion

This study found that the LEAP, a novel intervention to help families of children with ADHD make healthy lifestyle changes related to PA, sleep, and media use, was feasible and highly acceptable. Parents participated to a high degree in the weekly group sessions, Garmin, and social media components of the program and reported overall positive experiences with the LEAP program. We exceed all our feasibility and acceptability targets for the study. Overall, the intervention appears to be a promising approach to improve health behaviors and functioning in children with ADHD and has implications for improving behavioral treatment of ADHD.

The LEAP group curriculum was well-received, and parents reported utilizing the health behavior strategies taught (including daily active time, screen time limits, and bedtime routines) and finding them to be helpful. Of note, standard BMT strategies also received high scores from parents, implying that these evidence-based components were not compromised with the LEAP curriculum‘s adaptations.

The added behavior change techniques used in this intervention (mHealth technology monitoring and feedback, goal setting, and social support) were also found to be feasible and acceptable tools for use with parents and their children with ADHD. Some parents experienced challenges with understanding their devices‘ functionalities and required additional technical support. Thoughtful visual or video tutorials and tech support offerings may be considered for others interested in incorporating mHealth technology into behavioral interventions. Consumer wearables and mHealth technologies for promoting PA have gained considerable popularity in recent years; however, we are not aware of prior literature using them to promote PA in children with ADHD. This study’s feasibility data are promising concerning adherence with the wrist-worn activity trackers over 9 weeks, with both children and parents wearing their Garmin for over 5 days/week on average. Subsequent studies should include longer follow-up and adequate power to evaluate relations between Garmin wear and accelerometer-measured PA levels. The parents’ average step count during the first week of LEAP was 6,766 steps/day, indicating that they too could benefit from increasing their PA. Their average daily steps increased by about 369 steps from the first to the last week of LEAP, indicating a favorable trajectory in shifting parent health behaviors, though the week 1 measure took place after the intervention had begun and families were encouraged to exercise. The children’s average daily step counts decreased, with about 480 fewer steps by the end of LEAP. We hypothesize that children with ADHD in our study may have encountered a period of “overexcitement” that led to inflated initial step counts when they first received the Garmin devices. We also suspect seasonal effects could have played a role in changing step-counts during LEAP, especially for groups that started in warmer weather and ended in winter, when outdoor exercise became more limited. Overall, we suspect that most children in our study remained under the recommended 60 min/day MVPA after completing LEAP, with a step-count average of 9,270 steps by the end of LEAP. Limited evidence suggests that 60 min of MVPA in elementary school children can be achieved with a total volume of 13,000–15,000 steps/day in boys and 11,000–12,000 steps/day in girls (Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). Our primary outcome of PA will be measured with accelerometry prior to the intervention in a subsequent, adequately powered, investigation.

LEAP’s Facebook group component was also well received and may be a strategy that could be used to enhance existing and novel behavioral group interventions. Over forty percent of parents’ posts were related to community building and resource sharing topics, which suggests that group participants are eager for a platform to connect outside of the group meetings. Some participants expressed concerns about privacy on Facebook and preferred a different platform for interaction with group members, which is essential feedback for consideration. Mindfulness was also a novel strategy embedded within LEAP to promote parent wellbeing. Some parents reported using mindfulness skills but finding them only “somewhat” helpful; they also described these skills as reducing their stress and helping them be more present and intentional with their parenting. These findings support other recent studies (Anderson & Guthery, 2015; Miller & Brooker, 2017), indicating that mindfulness is a promising approach for targeting the overall wellbeing of parents raising children with behavior challenges.

Study limitations included the small sample size and the absence of a control group. Over 50% of the families in our study also reported household incomes in the top income bracket (over $150,000), which limits the generalizability of our study findings to other demographic groups, despite exceeding our target of recruiting over 10% of children identifying as part of a racial/ethnic minority group. Future recruitment should focus on community and primary care settings, rather than specialty care settings, as was mostly the case in this pilot. Our diagnostic screening procedures did not include collateral (teacher) report of child ADHD symptoms, which is considered best practice and enhances diagnostic validity. Additionally, we do not know whether medication doses changed during the intervention period and affected participant experiences. These limitations will be addressed with a subsequent randomized control trial (RCT) comparing LEAP to a standard BMT program. The proposed RCT will also assess sustained behavior changes by maintaining the Facebook and mHealth components of LEAP for a longer study period and measure PA outcomes with accelerometry before the intervention.

This pilot trial of the LEAP program found that BMT can be successfully modified to incorporate a focus on health behaviors and integrated with novel interactive technology to promote engagement, social connectedness, and goal-setting. Such an intervention has promise to improve the health and long-term well-being of children with ADHD, a population at-risk for chronic functional and health problems, including obesity. Our successful engagement strategies also have implications for enhancing other family-based interventions to include a focus on improving mental and physical health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our participating children and families for their time and support of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH; grant number 4R33AT010041-03).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Anderson S. B., Guthery A. M. (2015). Mindfulness-based psychoeducation for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: An applied clinical project. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(1), 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atienza A. A., Patrick K. (2011). Mobile health: The killer app for cyberinfrastructure and consumer health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(5 Suppl 2), S151–S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. A. (2013). Defiant children: Clinician’s manual for assessment of parent training (3rd edn).Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Clopper C. J., Pearson E. S. (1934). The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomal. Biometrika, 26(4), 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S., Faraone S. V., Konofal E., Lecendreux M. (2009). Sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis of subjective and objective studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 894–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson L. M., Aktar E., de Bruin E., Potharst E., Bögels S. (2021). Mindful parenting in secondary child mental health: Key parenting predictors of treatment effects. Mindfulness, 12(2), 532–542. [Google Scholar]

- Gapin J., Etnier J. L. (2010). The relationship between physical activity and executive function performance in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 32(6), 753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. (1976). ECDU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised. United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin J. M., Berwid O. G., O’Neill S. (2014). Healthy body, healthy mind? Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(4), 899–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin J. M., Healey D. M. (2011). The influences of environmental enrichment, cognitive enhancement, and physical exercise on brain development: Can we alter the developmental trajectory of ADHD? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 621–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G. C. C., Conduit R., Wong J., Di Benedetto M., Lee E. (2020). Diet, physical Activity, and screen time to sleep better: Multiple mediation analysis of lifestyle factors in school-aged children with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1087054720940417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Martin C. P., Pirog A., Shoulberg E. K. (2016). Using physical activity to manage ADHD symptoms: The state of the evidence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(12), 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B., Smith A. L., Shoulberg E. K., Linnea K. S., Dorsch T. E., Blazo J. A., Alerding C. M., McCabe G. P. (2015). A randomized trial examining the effects of aerobic physical activity on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(4), 655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J., Birmaher B., Brent D., Rao U., Flynn C., Moreci P., Williamson D., Ryan N. (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korioth T. (2020). Pediatricians want all families to be physically active for life. AAP News. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/02/24/parentplus022420. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Medina J. A., Netto T. L. B., Muszkat M., Medina A. C., Botter D., Orbetelli R., Scaramuzza L. F. C., Sinnes E. G., Vilela M., Miranda M. C. (2010). Exercise impact on sustained attention of ADHD children, methylphenidate effects. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 2(1), 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza J. A., Baker K. S., Moreno M. A., Whitlock K., Abbey-Lambertz M., Waite A., Colburn T., Chow E. J. (2017). A Fitbit and Facebook mHealth intervention for promoting physical activity among adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors: A pilot study. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 64(12), e26660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. J., Brooker B. (2017). Mindfulness programming for parents and teachers of children with ADHD. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 28, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece C. L. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: Implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 174–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. D., Attkisson C. C., Stegner B. L. (1983). Assessment of patient satisfaction: Development and refinement of a Service Evaluation Questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning, 6(3–4), 299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkelen S. W. C., Valkenburg P. M., Huizinga M., Bushman B. J. (2014). Media use and ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2228–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J., Gruber R., Brown T., Corkum P., Cortese S., O’Brien L., Stein M., Weiss M. (2013). Future research directions in sleep and ADHD: Report of a Consensus Working Group. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17(7), 550–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner L. J., Haack L. M. (2014). Behavior management for school-aged children with ADHD. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(4), 731–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontifex M. B., Saliba B. J., Raine L. B., Picchietti D. L., Hillman C. H. (2013). Exercise improves behavioral, neurocognitive, and scholastic performance in children with ADHD. The Journal of Pediatrics, 162(3), 543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumper M. A., Mendoza J. A., Arseniev-Koehler A., Holm M., Waite A., Moreno M. A. (2015). Using a Facebook group as an adjunct to a pilot mHealth physical activity intervention: A mixed methods approach. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 219, 97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1995). Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(4), 371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder E., Moreno M., Wilner M., Whitlock K. B., Mendoza J. A. (2017). Piloting a mobile health intervention to increase physical activity for adolescents with ADHD. Preventive Medicine Reports, 6, 210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder E. N., Chronis-Tuscano A., Strickland J., Almirall D., Stein M. A. (2019). Piloting a sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial for mothers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their at-risk young children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 29(4), 256–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. L., Hoza B., Linnea K., McQuade J. D., Tomb M., Vaughn A. J., Shoulberg E. K., Hook H. (2013). Pilot physical activity intervention reduces severity of ADHD symptoms in young children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17(1), 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung V., Hiscock H., Sciberras E., Efron D. (2008). Sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(4), 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon P. S., Sasser T., Gonzalez E. S., Whitlock K. B., Christakis D. A., Stein M. A. (2019). Physical activity, screen time, and sleep in children with ADHD. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 16(6), 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma V. K., Schulz-Zhecheva Y., Oser C., Fleischhaker C., Biscaldi M., Klein C. (2020). Media use, sleep quality, and ADHD symptoms in a community sample and a sample of ADHD patients aged 8 to 18 years. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(4), 576–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C., Craig C. L., Beets M. W., Belton S., Cardon G. M., Duncan S., Hatano Y., Lubans D. R., Olds T. S., Raustorp A., Rowe D. A., Spence J. C., Tanaka S., Blair S. N. (2011). How many steps/day are enough? For children and adolescents. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Oord S., Bögels S. M., Peijnenburg D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret C., Guay M.-C., Berthiaume C., Gardiner P., Béliveau L. (2012). A physical activity program improves behavior and cognitive functions in children with ADHD: An exploratory study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(1), 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yürümez E., Kılıç B. G. (2016). Relationship between sleep problems and quality of life in children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(1), 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]