Abstract

Purpose:

Patients with glioblastoma (GBM) have a poor prognosis and are in desperate need of better therapies. As therapeutic decisions are increasingly guided by biomarkers, and EGFR abnormalities are common in GBM, thus representing a potential therapeutic target, we systematically evaluated methods of assessing EGFR amplification by multiple assays. Specifically, we evaluated correlation between fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), a standard assay for detecting EGFR amplification, with other methods.

Experimental Design:

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples were used for all assays. EGFR amplification was detected using FISH (N = 206) and whole exome sequencing (WES, N = 74). EGFR mRNA expression was measured using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR, N = 206) and transcriptome profiling (RNAseq, N = 64). EGFR protein expression was determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC, N = 34). Significant correlations between various methods were determined using Cohen’s kappa (κ = 0.61 – 0.80 defines substantial agreement) or R2 statistics.

Results:

EGFR mRNA expression levels by RNAseq and RT-PCR were highly correlated with EGFR amplification assessed by FISH (κ = 0.702). High concordance was also observed when comparing FISH to WES (κ = 0.739). RNA expression was superior to protein expression in delineating EGFR amplification.

Conclusions:

Methods for assessing EGFR mRNA expression (RT-PCR, RNAseq) and copy number (WES), but not protein expression (IHC), can be used as surrogates for EGFR amplification (FISH) in GBM. Collectively, our results provide enhanced understanding of available screening options for patients, which may help guide EGFR-targeted therapy approaches.

Keywords: EGFR, depatuxizumab mafodotin, depatux-m, GBM, biomarkers

Introduction

Therapeutic decisions in glioblastoma (GBM), as with many other cancers, are increasingly reliant on biomarker analysis. Alterations such as amplification or mutation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) gene are a hallmark of disease pathogenesis in GBM (1), with EGFR amplification observed in ~50% (1–4). It has been shown that focal high-level amplification of the EGFR gene is associated with activation and overexpression of EGFR mRNA in GBM (5).

There are several methods available to assay for EGFR abnormalities in tumor tissue. Here, we describe correlations among fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to assess gene amplification, real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to assess mRNA transcription, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess protein translation, as well as whole exome sequencing (WES) and transcriptome profiling (RNAseq), to assess EGFR status. We further compare assays to determine concordance with FISH, which is often considered the standard in detecting gene amplification. Collectively, these results inform on comparability of various methods to evaluate EGFR in GBM, and potentially other tumor types, and may help guide personalized medicine decisions to better treat patients.

Methods

Study design and collection of tumor samples

Archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) GBM tissue was analyzed in a designated central laboratory from patients screened for a Phase 1 clinical trial (NCT01800695, also known as M12-356) of the EGFR antibody-drug conjugate depatuxizumab mafodotin (depatux-m, formerly ABT-414) currently under investigation for the treatment of EGFR-amplified GBM, as described previously (6–9). The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All patients or appropriate surrogates provided written informed consent for the trial and use of tissue for research studies prior to enrollment according to national regulation, and the study design was approved by the institutional review board and/or ethics committee of each participating institution. Values/disposition for all samples across all assays described below can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed by a central laboratory on 206 GBMs (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S1) using the Vysis EGFR CDx Assay (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA; not on market) comprising two DNA probes labeled with spectrally distinct fluorophores: orange locus-specific identifier (LSI) EGFR probe that hybridizes to 7p11.2-7p12 region, and green chromosome enumeration probe (CEP) 7 probe that hybridizes to a centromere of chromosome 7. Slides with probe mix were co-denatured at 73°C for 5 minutes and then hybridized at 37°C for 14-24 hours on a ThermoBrite (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Sample pretreatment and post-hybridization washes were performed using the Vysis Universal FFPE Tissue Pretreatment and Wash Kit (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, IL, USA; not commercially available).

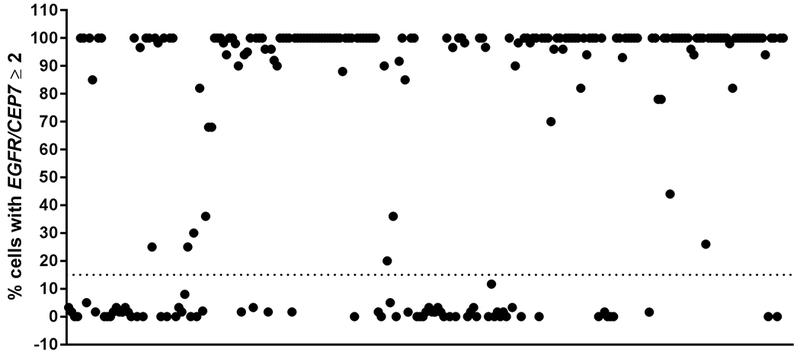

Figure 1. FISH amplification cut-off in tumor samples.

Tumors were deemed positive for EGFR amplification if ≥ 15% (dotted line) of cells demonstrated amplification (defined as EGFR/CEP 7 ratio was ≥ 2). FISH performed on 206 samples; 3 are excluded here (FISH failure).

Slides were reviewed using fluorescence microscopy with orange, green and DAPI (4’,6-diamindino-2-phenylindole) filters. FISH signal counts (copy number) for orange and green were recorded for a total of 50 nuclei in the targeted tumor areas, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2). A tumor was considered EGFR-amplified when there was focal EGFR gene amplification defined as EGFR/CEP 7 ratio was greater than or equal to 2 in ≥ 15% recorded cells. Tumors with polysomy for chromosome 7 (excess copies of the entire chromosome defined as CEP7/EGFR < 2 and CEP7 copy number > 3) but without focal amplification of the EGFR gene ≥ 15% were considered to be EGFR-nonamplified.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Real-time RT-PCR was used to determine relative EGFR mRNA expression levels in 206 GBMs. Relative EGFR mRNA expression was also determined from 20 non-GBM, normal brain tissue specimens (ProteoGenex, Inglewood, CA, USA). Briefly, one ≥ 5μM section containing a minimum of 50 mm2 total tissue area from the FFPE block was processed for RNA extraction using the QIAGEN RNeasy FFPE Extraction Kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD, USA) per manufacturer’s instructions. For non-GBM normal brain tissue specimens, one ≥ 5 μM section containing a minimum of 50 mm2 total tissue area from the FFPE block was processed for RNA extraction using the TargetPrep RNA Pro Kit (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA; not commercially available). FFPE sections were deparaffinized and cells were lysed in the presence of Proteinase K. The nucleic acids were de-crosslinked from formalin and DNAase treated to remove DNA content, captured using microparticles, washed, and eluted. Purified RNA was combined in a 96-well plate with mastermix containing primers and probes for amplification and detection of total EGFR and β-actin on the Abbott m2000 RealTime System (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA). β-actin served as an endogenous control and to provide relative quantitative values for total EGFR expression in the samples. The difference (ΔCt) between β-actin Ct and total EGFR Ct was calculated and reported.

Whole exome sequencing (WES)

WES was performed on 74 GBMs to assess EGFR gene amplification. Tumor DNA was obtained by macrodissection of the tumor area (> 50% tumor content) from FFPE slides. Tumor genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAGEN AllPrep Kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD, USA). Whole exome sequencing libraries were prepared using the SureSelect Clinical Research Exome kit (Agilent, Cedar Creek, TX, USA). Sequencing was performed with an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (2 × 100 base pairs) (Illumina, Hayward, CA, USA). Profiling aimed to achieve a 150× mean on-target coverage. ArrayStudio (Omicsoft Corporation, Cary, NC, USA) was used for sequence alignment and quality control. Copy number variations (CNV) were estimated from WES data using both Sentieon and GATK4 beta versions following suggested CNV best practice guidance. Briefly, sequencing alignment, deduplication and realign-recalibration were performed using Sentieon Genomics Tools (Sentieon, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (10). Realigned bam files of tumor samples were used to calculate library-size normalized mean read depth (coverage) for each WES interval. Further normalization and noise smoothing of the coverage of tumor samples were done by tangent normalization against a panel of normal samples (PON). CNV were identified and merged into larger segments using CBS algorithm. A cut-off of > 3 copies of the EGFR gene was used to define amplification.

Whole transcriptome sequencing (RNAseq)

RNAseq was performed on 64 GBMs to determine EGFR gene transcription. Library preparation was performed with 1-50 ng of total RNA. Double-stranded complementary DNA (ds-cDNA) was prepared using the SeqPlex RNA Amplification Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) per manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was blunt ended, had an A base added to the 3’ ends, and then Illumina sequencing adapters ligated to the ends. Ligated fragments were amplified for 12 cycles using primers incorporating unique index tags. Fragments were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 or HiSeq 3000 using single reads extending 50 bases. Twenty-five to 30 million reads per library were targeted.

RNA sequencing reads were aligned to the Ensembl release 76 assembly with STAR version 2.0.4b. Gene counts were derived from the number of uniquely aligned unambiguous reads by Subread:featureCount version 1.4.5. Transcript counts were produced by Sailfish version 0.6.3. Sequencing performance was assessed for total number of aligned reads, total number of uniquely aligned reads, genes and transcripts detected, ribosomal fraction known junction saturation, and read distribution over known gene models with RSeQC version 2.3.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was performed on 34 GBMs to assess EGFR protein expression using the EGFR pharmDx Kit for Dako Autostainer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). H-score was calculated as described previously (11) as a continuous variable. In brief, the range of H-score is 0 – 300 and is a quantitative measure of protein expression. A score of 200 – 300 was considered as high EGFR expression. The DAKO antibody clone 2-18C9 recognizes both wild-type and EGFRvIII forms of EGFR, and therefore represents total EGFR protein expression.

Statistical analysis

Cohen’s kappa statistic (12) was used to compare categorical agreement between amplification detection by FISH with amplification detection by WES and with mRNA expression by RT-PCR. Briefly, k < 0 indicates poor agreement, 0.0 – 0.20 slight agreement, 0.21 – 0.40 fair agreement, 0.41 – 0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61 – 0.80 substantial agreement, 0.81 – 1.0 almost perfect agreement (13). R2 statistic was calculated by linear regression and was used to correlate mRNA expression determined by RNAseq vs RT-PCR, and association between mRNA expression by RT-PCR and WES copy number.

Results

Threshold determination for FISH and RT-PCR assays

FISH was performed on 206 tumor samples. As above, a sample was defined as EGFR-amplified if it had an EGFR/CEP 7 copy number ratio ≥ 2 in ≥ 15% recorded cells. Most tumors had clear results for EGFR amplification, with few ambiguous cases (Figure 1). For example, 93% of GBMs harbored either a very high (≥ 80% cells; 69% of samples) or very low (≤ 5% cells; 24% of samples) number of amplified cells showing EGFR amplification, with few (6%) falling mid-range. This is consistent with historical work, which has also shown a clear dichotomy between “amplified” or “nonamplified.” For example, in early studies from the 1980s – 1990s describing EGFR abnormalities in GBM, amplification was typically unambiguous (20× (14) to 50× (15) increases in gene copy number). Finally, one patient with a partial response to depatux-m in our dataset had a tumor harboring EGFR amplification in 16% of cells (9), which contributed to the establishment of a minimum threshold at 15% to delineate EGFR amplification.

Among 91 samples analylzed, 56 (62%) demonstrated chromosome 7 polysomy. Of those, only 13 (23%) also had concurrent focal EGFR amplification. There was not a significant correlation of polysomy with increased EGFR mRNA expression (Supplementary Figure S3).

For RT-PCR, the cut-off was determined to be ΔCt ≥ −5.50, and was informed by EGFR mRNA expression levels as observed in 20 normal brain samples, and association with EGFR amplification status in 94 tumor samples (46%). The samples demonstrating ΔCt of ≥ −5.50 were considered positive for total EGFR mRNA expression. The other 112 samples (54%) were tested after the cut-off was set. Using this cut-off, 90% of tumor samples positive for EGFR mRNA expression demonstrated EGFR amplification.

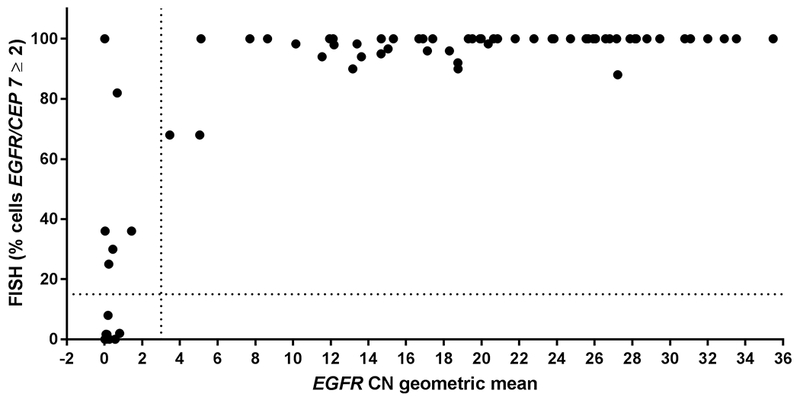

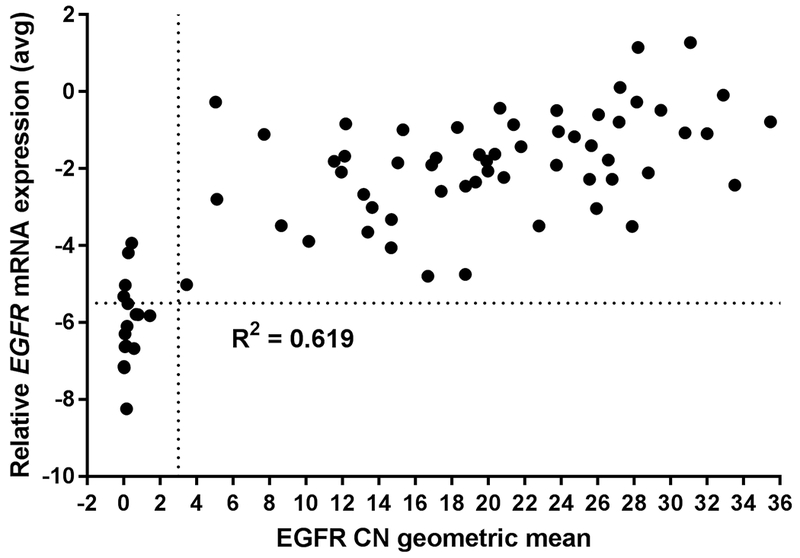

Concordance of amplification by FISH and WES

Of the 74 samples that underwent WES, a 92% concordance rate (68/74) with EGFR amplification status was observed when comparing WES to FISH results (Supplementary Table S2) and substantial agreement was observed (κ = 0.739 [95% CI = 0.538, 0.939]). The majority of the discordant cases were low FISH positive (Figure 2), and thus not captured by WES, which normalizes copy number across the tissue sample instead of on a cell-by-cell basis as with FISH. EGFR expression data, as determined by RT-PCR, was tightly associated to WES copy number determination (R2 = 0.619, Figure 3). Furthermore, all samples screened by WES underwent mutational analysis; 37 unique point mutations were identified, some of which were present in more than one sample (Supplementary Figure S4, Supplementary Table S3). Three mutations have also been identified as pathogenic in the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). However, we did not identify any mutations that were significantly associated with EGFR amplification, likely because of the small sample size.

Figure 2. Correlation of EGFR amplification by FISH with copy number (CN) determined by WES.

X-axis, geometric mean of EGFR copy number (all exons except exons 2–7); linear scale. Vertical dotted line at 3 delineates EGFR-amplified (to the right) vs –nonamplified samples (to the left) by CN. Y-axis, percentage EGFR amplification by FISH. Cut-off for amplification (≥ 15%) indicated by dotted horizontal line. N = 74 samples.

Figure 3. EGFR mRNA expression is highly associated with copy number (CN) determined by WES.

X-axis, geometric mean of EGFR copy number (all exons except exons 2-7); linear scale. Vertical dotted line at 3 delineates EGFR-amplified (to the right) vs –nonamplified samples (to the left) by CN. Y-axis, EGFR mRNA expression measured by RT-PCR (ΔCt); linear scale. Horizontal dotted line at −5.50 delineates cut-off between EGFR-positive (above line) and -negative (below line) samples. N = 74 samples.

Concordance of FISH with mRNA transcription and protein expression

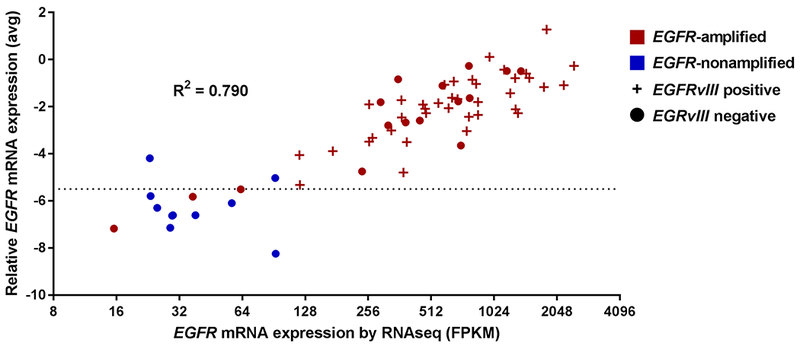

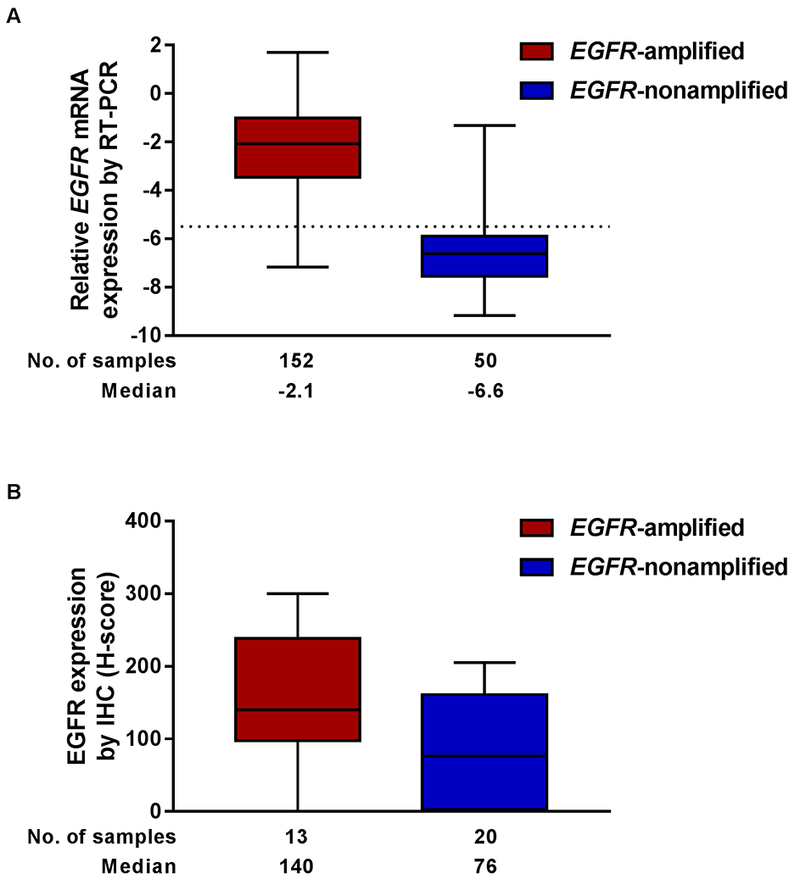

We further evaluated EGFR mRNA and protein expression in the context of focal gene amplification. In 201 samples tested by both FISH and RT-PCR, a 94% concordance rate (188/201) was observed between the assays, and we again observed substantial agreement (κ = 0.702 [95% CI = 0.473, 0.931]) (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Figure S5). RNAseq was comparable to RT-PCR, demonstrating correlation of R2 = 0.790 (Figure 4). A 94% concordance rate (60/64) was observed in samples that had both RNAseq and FISH results with substantial agreement (κ = 0.796 [95% CI = 0.603, 0.990]) (Supplementary Table S5). As with focal gene amplification testing by FISH, mRNA results were typically unambiguous; for example, total EGFR mRNA by RT-PCR was approximately 19-fold higher in patient samples with FISH-defined EGFR amplification vs those without (Figure 5A).

Figure 4. EGFR expression by RNAseq and RT-PCR are comparable.

Correlation between RNAseq (x-axis, log2 scale; FPKM, fragments per kilobase million.) and RT-PCR (y-axis, ΔCt, linear scale) results in 64 tumor samples. Horizontal dotted line at −5.50 delineates cut-off between EGFR-positive (above line) and -negative (below line) samples. Colors indicate EGFR amplification as determined by FISH, symbol indicates EGFRvIII mutation (present +, absent •), with mutation detected exclusively among EGFR-amplified tumors.

Figure 5. Correlation of EGFR amplification with mRNA and protein expression.

A, EGFR mRNA expression measured by RT-PCR (ΔCt, linear scale). FISH and RT-PCR assays performed on 202 samples; 4 are excluded here (2 FISH failure, 1 FISH result unreadable, 1 RT-PCR failure). B, H-score for EGFR protein expression determined by IHC. Colors indicate EGFR amplification as determined by FISH. FISH and IHC assays performed on 34 samples; 1 sample with an H-score of 0 is excluded due to FISH failure. Error bars indicate range.

A less well-defined association between EGFR amplification as determined by FISH and protein expression as assessed by IHC was observed (Figure 5B). Protein expression was determined as a continuous variable (H-score) in 33 GBMs. Numerically, there was a trend between higher protein expression in EGFR-amplified vs -nonamplified cases. However, when defining high EGFR protein expression as an H-score ≥ 200, there was only 73% concordance (24/33) with FISH, and fair agreement was observed (κ = 0.369 [95% CI = 0.018, 0.721) (Supplementary Table S6). Neither lowering the threshold for high EGFR expression to 150, nor performing similar comparisons with H-score sub-components (data not shown), increased accuracy of IHC to discriminate between samples that were amplified with high EGFR expression vs nonamplified with high EGFR expression as easily as assays measuring EGFR mRNA; thus, an IHC cut-off threshold could not be determined.

Discussion

Here, we have described different methods used to determine EGFR excess in GBM (Table 1). When performing FISH, we observed a distinct dichotomy: those with a high proportion of EGFR-amplified cells, and those with very few amplified cells. We found that EGFR mRNA relative expression had a higher association with EGFR amplification as determined by FISH than did protein expression as determined by IHC. As the Phase 1 trial progressed, it became apparent that radiographic responses to depatux-m were observed exclusively in patients with GBMs that harbored EGFR amplification rather than EGFR overexpression by IHC. Therefore, routine performance of IHC was aborted mid-trial to conserve tissue.

Table 1.

Comparison of EGFR testing methods

| FISH | WES | RT/PCR | RNAseq | IHC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | 15% tumor cells with amplification defined as EGFR/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2 | Relative copy number EGFR exons (excluding 2-7) compared with chromosome 7 1.3 log increase of EGFR categorized as amplified |

Normalized to β-actin ΔCt of β-actin – EGFR used and ΔCt ≥ −5.5 categorized as overexpressed |

RPKM > 40 categorized as overexpressed | Indeterminate |

| Correlation with FISH | NA | Substantial agreement with amplification by FISH | Substantial agreement with amplification by FISH | Highly associated with EGFR RT-PCR | Low specificity to detect amplification |

| Pros | Widely used methodology Fluorescence allows for more multiplexing as compared with similar techniques such as chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) |

Highly flexible and can assess many genetic changes in parallel | Multiple assay options | Highly flexible and can assess many targets in parallel | Broadly used, widely available method of protein expression Cost effective Latest automation minimizes human variable Quick turnaround |

| Cons | Fluorescence fades over time Fluorescence technology more expensive than CISH |

Complex process and algorithms with more room for variation Loss of cell and tissue morphology More expensive and longer turnaround time than FISH |

Detects mRNA expression as a surrogate for amplification | Detects mRNA expression as a surrogate for amplification More expensive and longer turnaround time than FISH |

Not a direct measurement of gene amplification Measures protein expression only Semi-quantitative False positive and false negative cases |

The lack of specificity of IHC to accurately identify patients responsive to depatux-m was also observed in a Phase 1/2 trial for advanced solid tumors (none of which were GBM) (16). In that study, 21 patients (38%) had a tumor sample with an EGFR H-score ≥ 150, but only 1 patient had a partial response. By contrast, of the 35 samples tested for amplification by FISH, only 6 (17%), including one from the responsive patient, were EGFR-amplified. Moreover, the vast majority of GBMs demonstrate EGFR protein overexpression. For example, Schlegel et al (15) found EGFR gene amplification (using Southern blot) in 49% of GBMs, consistent with our results, but reported EGFR overexpression at the protein level by IHC in 92%, lending further support to our conclusion that EGFR protein overexpression cannot be used effectively as a predictive biomarker as its presence is nearly ubiquitous. These data, combined with previous studies that have shown discrepancies in IHC concordance with other antibodies, tests across multiple sites, and reproducibility (17,18), raise further concern with the use of IHC as a screening method to identify the appropriate targeted population. Accordingly, fewer samples were tested for EGFR IHC than by other methods, and central testing of amplification by FISH became an eligibility criterion for patients accrued to multiple clinical trials of depatux-m (NCT01800695, NCT02573324, NCT02343406, NCT02590263). To that end, using FISH as the gold standard for amplification, mRNA expression and amplification detection by WES were highly associated, with a major contributing factor likely to be the multi-log dynamic range that encompasses low to high expression of EGFR. IHC had a weaker association, which may be partly attributed to its insufficient analytical dynamic range to measure the large biological dynamic range at the higher end of EGFR expression observed in GBM, demonstrated by 8/27 samples with low EGFR expression by H-score still classified as EGFR-amplified by FISH, and 1/6 samples with high H-score classified as EGFR-nonamplified (Supplementary Table S5). With an ever-growing list of targeted therapies in GBM as well as other cancers, a firm understanding of concordance of molecular methods measuring biomarkers is critical.

Importantly, our results demonstrate that an array of methods beyond FISH can be used to assay for EGFR gene amplification, including WES and RNAseq (but excluding IHC), all with equivalent validity to identify cases for appropriate therapy, thereby reducing the potential for depleting tissue as a precious resource in performing multiple tests for the same biomarker. Furthermore, comparison of screening results obtained by central FISH assay vs a local FISH (or chromogenic in situ hybridization) assay developed and performed by an independent academic molecular pathology laboratory suggest a high concordance rate of 90% (19). This suggests that local biomarker results may be adequate to identify EGFR amplification, which could help to streamline the process of biomarker testing and conserve tissue.

Of note, data presented here demonstrate that “newer” assays, which look across the exome or transcriptome (i.e., WES, RNAseq), are well associated with mature technology (i.e., FISH) and may offer opportunities to look at multiple biomarkers in the context of one another as opposed to a univariate view (Table 1). The differences tended to be in samples with low amplification, indicating FISH was more sensitive. Although these techniques are complex, they are becoming more common and offer multiple options to assess the genome as a whole. This may refine predictive biomarkers in a patient and allow a patient to be screened for multiple potential therapies at one time. Beyond EGFR, there are molecular markers that are already commonly tested for in GBM (20,21), and screening to identify other events may become more common as further targeted therapies, and novel combination therapies, emerge in the treatment landscape. Systematic studies cross-comparing various assay approaches can help elucidate the analytical strengths and weaknesses of biomarker methodologies so that trade-offs in terms of sensitivity vs throughput can be optimized. In our ongoing studies, we continue to use FISH for central testing when weighing the pros and cons in comparison to other assays (Table 1).

As mentioned, in the Phase 1 study M12-356 of patients with GBM treated with depatux-m, radiographic responses occurred exclusively among patients with EGFR-amplified disease by FISH (7,9,22). Recently reported results from the INTELLANCE-2 study in EGFR-amplified rGBM revealed a survival benefit from the combination of depatux-m and TMZ in multiple subgroups (23,24). Thus, the positive correlation of EGFR amplification with clinical benefit further emphasizes that a clinically relevant biomarker for patient selection, proper screening, and a personalized medicine approach is of paramount importance and EGFR amplification was therefore used for eligibility criterion in further clinical trials. These findings may inform future studies in a targeted population, including the ongoing INTELLANCE-1 trial (NCT02573324) in newly diagnosed GBM. Collectively, these results provide a better understanding of screening options for patients, and may help to further guide EGFR-targeted therapy approaches in GBM and potentially other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Therapeutic decisions in glioblastoma (GBM) are increasingly reliant on the molecular characterization of a patient’s tumor. EGFR gene amplification occurs in ~50% of GBMs, and thus presents an important target for therapeutic intervention and as a potential predictive biomarker. Various methodologies are available to assess EGFR amplification and expression status. A systematic study evaluating different methods to assess EGFR amplification and expression was undertaken to understand comparability and concordance of various assays to evaluate EGFR status in GBM. Using EGFR amplification as detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as the reference method, we found that amplification detection using whole exome sequencing and RNA expression by either RT-PCR or RNAseq were well correlated, whereas protein detection by immunohistochemistry was not. Collectively, these results provide information on comparability of various methods to evaluate biomarkers in GBM, and potentially other tumor types, and may help guide precision medicine-oriented decisions with EGFR-directed therapies.

Acknowledgements

AbbVie, Inc. provided financial support for this study (NCT01800695) and participated in the design, study conduct, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as the writing, review, and approval of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the data gathering, analysis, review, interpretation and manuscript preparation and approval. The authors and AbbVie would like to thank patients and their families/caregivers; study investigators and staff; Mrinal Y. Shah, PhD for medical writing support, and Yan Sun, PhD for statistical support, both of AbbVie, Inc.; and the Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine for help with genomic analysis. The Center is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and by ICTS/CTSA Grant #UL1RRO24992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. ABL was supported in part by grants 5P30CA013696-43 and 5UG1CA189960-04 from the NCI. This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH.

Financial Support: AbbVie

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Andrew B. Lassman: In the last 12 months, honoraria from AbbVie, Agios, American Society of Clinical Oncology, Focus Forward Incentives, GLG, Guidepoint Global, Health Advisors Bureau, Olson Research Group, Sapience, WebMD, Research America, Connected Research and Consulting, Physicians’ Education Resource, Atheneum, Bionest Partners, NCI; research support (to institution) from Genentech/Roche, AbbVie, University of California Los Angeles, Millennium, Celldex, Pfizer, Aeterna Zentaris, Novartis, Karyopharm, NCI, Cornell University, RTOG Foundation, VBI Vaccines; travel support from AbbVie, Agios, NRG Oncology, Tocagen, New York University, Global Coalition for Adaptive Research, Yale, Oncoceutics

Lisa Roberts-Rapp, Zheng Zha, Xin Lu, Erica Gomez, Anahita Bhathena, David Maag, Kyle D. Holen, Peter J. Ansell: Employees of AbbVie and may own stock/options

Irina Sokolova, Ekaterina Pestova, Minghao Song, Rupinder Kular, Carolyn Mullen: Employees of Abbott Laboratories and may own stock/options

Priya Kumthekar: Consulting/advisory role for AbbVie

Hui K. Gan: Consulting/advisory role for AbbVie, Merck Serono; served on speakers’ bureau for Ignyta, BMS, AbbVie; travel, accommodations, expenses reimbursed from Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Ignyta; research funding from AbbVie; affiliated with the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research

Andrew M. Scott: Consultant/advisory role for AbbVie, Life Science Pharmaceuticals; research funding from AbbVie, EMD Serono, Daiichi-Sankyo; inventor on mAb ABT-806 patents; affiliated with the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research

Martin J. van den Bent: Honoraria from Roche, AbbVie, Celldex, Celgene, VAXIMM, BMS, Novartis; research funding from AbbVie

References

- 1.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 2013;155(2):462–77 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan HK, Cvrljevic AN, Johns TG. The epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII): where wild things are altered. FEBS J 2013;280(21):5350–70 doi 10.1111/febs.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimoto K, Dang J, Zhu S, Nathanson D, Huang T, Dumont R, et al. Development of a real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting EGFRvIII in glioblastoma samples. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14(2):488–93 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bent M, Roberts-Rapp LA, Ansell P, Lee J, Looman J, Bain E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplification rates observed in screening patients for randomized clinical trials in glioblastoma. Ann Oncol 2017;28(Suppl 5) doi 10.1093/annonc/mdx366.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(50):20007–12 doi 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reardon DA, Lassman AB, van den Bent M, Kumthekar P, Merrell R, Scott AM, et al. Efficacy and safety results of ABT-414 in combination with radiation and temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2017;17(7):965–75 doi 10.1093/neuonc/now257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan HK, Reardon DA, Lassman AB, Merrell R, van den Bent M, Butowski N, et al. Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Antitumor Response of Depatuxizumab Mafodotin as Monotherapy or in Combination with Temozolomide in Patients with Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;20(6):838–47 doi 10.1093/neuonc/nox202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Bent M, Gan HK, Lassman AB, Kumthekar P, Merrell R, Butowski N, et al. Efficacy of depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) monotherapy in patients with EGFR-amplified, recurrent glioblastoma: results from a multi-center, international study. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2017;80(6):1209–17 doi 10.1007/s00280-017-3451-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lassman AB, van den Bent MJ, Gan HK, Reardon DA, Kumthekar P, Butowski N, et al. Safety and efficacy of depatuxizumab mafodotin + temozolomide in patients with EGFR-amplified, recurrent glioblastoma: results from an international phase I multicenter trial. Neuro Oncol 2018. doi 10.1093/neuonc/noy091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed DN, Aldana R, Weber JA, Edwards JS. The Sentieon Genomics Tools - A fast and accurate solution to variant calling from next-generation sequence data. bioRxiv 2017. doi 10.1101/115717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirker R, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, Krzakowski M, Ramlau R, Park K, et al. EGFR expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of data from the phase 3 FLEX study. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(1):33–42 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960;20(1):37–46 doi 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libermann TA, Nusbaum HR, Razon N, Kris R, Lax I, Soreq H, et al. Amplification, enhanced expression and possible rearrangement of EGF receptor gene in primary human brain tumours of glial origin. Nature 1985;313(5998):144–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlegel J, Stumm G, Brandle K, Merdes A, Mechtersheimer G, Hynes NE, et al. Amplification and differential expression of members of the erbB-gene family in human glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 1994;22(3):201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goss GD, Vokes EE, Gordon MS, Gandhi L, Papadopoulos KP, Rasco DW, et al. Efficacy and safety results of depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) in patients with advanced solid tumors likely to overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer 2018;124(10):2174–83 doi 10.1002/cncr.31304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson RA, Adams RA, McArt DG, Salto-Tellez M, Jasani B, Hamilton PW. Epidermal growth factor receptor immunohistochemistry: new opportunities in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Transl Med 2015;13:217 doi 10.1186/s12967-015-0531-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anagnostou VK, Welsh AW, Giltnane JM, Siddiqui S, Liceaga C, Gustavson M, et al. Analytic variability in immunohistochemistry biomarker studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19(4):982–91 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lassman A, Dimino C, Mansukhani M, Murty V, Holen KD, Ansell PJ, et al. PATH-35. MAINTENANCE OF EGFR ABNORMALITIES OVER TIME AND COMPARISON OF MOLECULAR METHODOLOGIES IN GLIOBLASTOMA (GBM). Neuro-Oncology 2017;19(suppl_6):vi178–vi doi 10.1093/neuonc/nox168.725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352(10):997–1003 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med 2009;360(8):765–73 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lassman AB, Bent MJVD, Gan HK, Reardon DA, Kumthekar P, Butowski NA, et al. Efficacy analysis of ABT-414 with or without temozolomide (TMZ) in patients (pts) with EGFR-amplified, recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) from a multicenter, international phase I clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017;35(15_suppl):2003. doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Bent M, Eoli M, Sepulveda JM, Smits M, Walenkamp AM, Frenel JS, et al. First Results of the Randomized Phase II Study on Depatux-m Alone, Depatux-m in Combination With Temozolomide and Either Temozolomide or Lomustine in Recurrent EGFR Amplified Glioblastoma: First Report From INTELLANCE 2/EORTC Trial 1410. Neuro Oncol 2017;19(suppl_6):vi316 doi 10.1093/neuonc/nox213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Bent MJ, French P, Eoli M, Sepulveda JM, Walenkamp AM, Frenel JS, et al. Updated results of the INTELLANCE 2/EORTC trial 1410 randomized phase II study on Depatux-M alone, Depatux-M in combination with temozolomide (TMZ) and eitehr TMZ or lomustine (LOM) in recurrent EGFR amplified glioblastoma (NCT02343406). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018;36(15_suppl):2023 doi 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.