Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted both healthcare delivery and the education of healthcare students, with a shift to remote delivery of coursework and assessment alongside the expansion of the scope of practice of Alberta pharmacists. The objective of this research was to understand how the learning of pharmacy students at the University of Alberta was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was distributed to 397 pharmacy students in years one through three. Students responded to three short-answer reflection questions: (1) how has the COVID-19 pandemic situation affected your learning; (2) from a pharmacy and pharmacy school perspective, what have you learned since the COVID-19 pandemic began; and (3) from a personal perspective, what have you learned about yourself since the COVID-19 pandemic began? A thematic analysis was undertaken of students' responses to these reflection questions.

Results

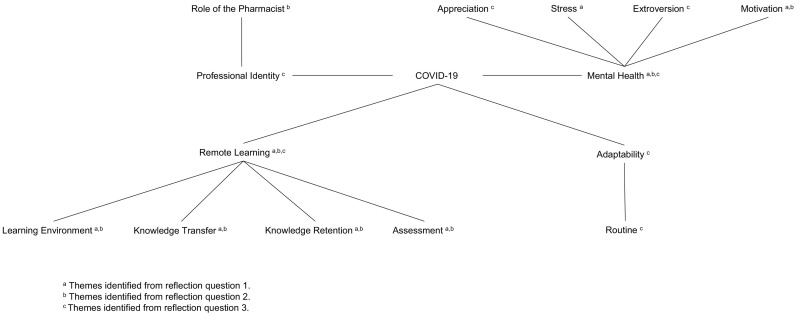

A total of 53 students responded to the survey (response rate 13%). Two major themes were identified across all three reflection questions, with several subthemes: remote learning (learning environment, knowledge transfer, knowledge retention, assessment) and mental health (appreciation, stress, extroversion, motivation). Adaptability, routine, professional identity, and the role of the pharmacist were also identified as less prevalent themes.

Conclusions

Pharmacy students' responses led to the identification of several themes related to their learning given the changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. This increased understanding of student perceptions has the potential to improve the remote delivery of education, support increased university-wide mental health resourcing, and shape pharmacy curriculum development.

Keywords: Pharmacy student, Pharmacy school, Learning, COVID-19, Pandemic, Thematic analysis

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly brought about global change in all aspects of daily life. One major change included the remote delivery of all levels of education due to widespread school closures and enforced social isolation measures. From mid-March 2020, pharmacy students at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada experienced a shift from in-person to remote delivery of all lecture, seminar, and clinical skills lab content. Students were encouraged to return to their permanent residences (including those out of province or country) and assessment was converted to credit/no-credit to accommodate this transition.

Healthcare delivery and resources were also impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with pharmacist roles being observed and taken up by pharmacy students on experiential placements and/or working in community pharmacies. Pharmacists in Alberta enjoy the broadest scope of practice in Canada.1 During the pandemic pharmacists provided patient assessment of potential COVID-19 symptoms and were enabled to renew and extend therapy for narcotic and controlled drugs under Health Canada's exemption to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to ensure continuity of care.2 Pharmacists were also crucial in safeguarding the supply of critical medications.3

Existing literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education focuses on remote learning and the advantages, disadvantages, and challenges faced with this transition.4 While recognizing the shift from in-person to remote delivery of pharmacy student education was a considerable change during this time, our study aimed to examine the holistic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our student population. The objective of this research was to better understand how the learning of pharmacy students at the University of Alberta was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic considering the changes to pharmacy student education and additional pharmacist responsibilities in Alberta.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey of pharmacy students was undertaken. Invitations to participate in the anonymous questionnaire (Google) were sent via email to all pharmacy students in years one through three at the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta. The questionnaire was distributed by the faculty's student services office with a reminder sent one week later. To ensure anonymity of responses, no identifying information (including email addresses) was collected. The questionnaire was administered at the end of the second semester of the 2019–2020 academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

The questionnaire contained the following demographic questions: current year of study, gender, age, pharmacy-related work status, and pharmacy-related work during remote delivery of classes. Three short-answer reflection questions were posed, with supporting prompts: (1) how has the COVID-19 pandemic situation affected your learning (think about aspects of your mental health, stress level, ability to complete schoolwork, how effectively you are learning, if your environment impacts your learning, etc.); (2) from a pharmacy and pharmacy school perspective, what have you learned since the COVID-19 pandemic began (think about how you socialize/interact in school and at work; how you progressed through your different courses, if you feel you effectively learned from the online learning, etc.); and (3) from a personal perspective, what have you learned about yourself since the COVID-19 pandemic began (think about who you are, how you feel, and the potential impact on your professional identity)?

Data analysis

This qualitative research utilized a thematic analysis of the three reflection questions to better understand how students were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. A thematic analysis was chosen for its flexibility in research questions that can be addressed and its descriptive, holistic approach.5 Individual responses to each question were analyzed for recurring themes using the five-stage process of compiling, disassembling, reassembling, interpreting, and concluding.6 First, each individual response was read to highlight important words/phrases, then these meaningful statements were reduced to short statements, and finally emerging common themes were coded. A second researcher conducted an independent review of the initial codes to determine if they were consistent with the data. The identified themes were then cross-compared illustrating both overlap and inter-relation between themes. Microsoft Excel, version 16.32 (Microsoft Corp.) was utilized for data entry and analysis. A mind map was then created to display the individual themes and the high-level relationships between themes using Microsoft PowerPoint, version 16.32 (Microsoft Corp.).

This study was approved by the Human Research and Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00099226).

Results

Demographics

Of the 397 students who received the questionnaire, 53 responded (response rate 13%). The students that responded were relatively evenly distributed between all three years of study (Table 1 ). There was a larger proportion of females who responded (n = 33) and the most prevalent age group was 20 to 24-years-old (n = 39). A similar number of students reported currently working in a pharmacy compared to those who were not (n = 23 and n = 29, respectively), comparable to those citing work in a pharmacy during remote classes.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents (N = 53).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Year of study | |

| Year 1 | 19 (36) |

| Year 2 | 19 (36) |

| Year 3 | 15 (28) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (30) |

| Female | 33 (62) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (8) |

| Age (years) | |

| <20 | 1 (2) |

| 20–24 | 39 (74) |

| 25–29 | 12 (23) |

| Currently working in a pharmacy | |

| Yes | 29 (55) |

| No | 23 (43) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2) |

| Working during online classes | |

| Yes | 29 (55) |

| No | 23 (43) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2) |

Thematic analysis

Two major themes were identified across all three reflection questions. The themes of remote learning and mental health were the most prevalent and had several facets (Fig. 1 ). Identified sub-themes of remote learning included learning environment, knowledge transfer, knowledge retention, and assessment. Sub-themes of mental health were identified as appreciation, stress, extroversion, and motivation. In addition, adaptability, routine, professional identity, and the role of the pharmacist were also identified as themes. Overlapping themes across the reflection questions are displayed in the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Identified themes of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy students' personal and professional learning.

Question 1: how has the COVID-19 pandemic situation affected your learning?

When asked, most students gave an initial statement that their learning was “impacted [ ] at all levels” and that the pandemic was “detrimental to [their] education.” Students provided several reasons including frustration with aspects of remote learning: “it takes longer to get through material” and “it was difficult to keep track of schoolwork.” Several students also explained aspects of their home learning environment such as being “loud and distracting” which was “not conducive of productivity.” Another student described that the “move back home [ ] is not the ideal situation for learning because of poor internet connection and my family not understanding that I have to study and do work.”

Further concerns students expressed with respect to learning included knowledge retention and knowledge transfer in both theory-based and clinical skills courses. “I crammed [ ] for exams instead of learning for the long term,” one student noted. “I fear that this may affect my ability to remember [ ] material covered this semester on the PEBC (Pharmacy Examining Board of Canada) [exam and in] future practice,” stated another. In terms of the ability for knowledge to be transferred from instructor to student, one student said, “I didn't soak up as much information [as I otherwise would have prior to the COVID-19 pandemic].” Another student explained that “online lectures were also much shorter [ ] so it felt like we just breezed through the material [ ] and did not dwell on extraneous information or details that could be applicable to practice.” Others noted the lack of structure and engagement with their instructor and peers due to remote education. “It's much more difficult to follow lectures and truly understand what's going on by watching a [ ] video because there isn't a discussion.” One student said that “there is no bouncing back and forth of ideas with classmates” and another expressed that the “nature of practice skills lab requires in-person meetings to be fully effective.”

Several students also noted how the changes to assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic affected their learning. For example, one student stated “I tried very hard to try to learn material, but because of the pass/fail system, it was easy to just learn the material well enough to know where to find information, rather that actually recalling it.” Another student said, “I felt less stressed out and less motivated to put in the usual amount of effort into school because our examinations were now open book and pass or fail.”

In response to how the COVID-19 pandemic situation has affected their learning, many students also mentioned the negative impact on their mental health. Several students revealed the effect of social isolation: “The isolation, not being able to see any of my friends (in person) has had a negative impact on me, and I could feel my mental health declining.” A few students gave examples of how they were coping with social isolation, such as “I have had to make a conscious effort to do things to help keep myself sane - I've been going for runs, talking more to friends and family, cleaning/organizing, and reading.”

Some students also noted that in addition to social isolation, their mental health was impacted by increased stress and declining motivation. Students identified several factors implicated in their stress including the lack of hands-on learning opportunities, transition to remote classes, and concern of contracting the virus. A commonality between sources of their stressors was the overall uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic. As one student explained, “online classes were very stressful initially because of the unknown.” As well, students expressed that their motivation was diminished with remote classes and not having their peers physically present. As one student said, “I find it difficult to create my own motivation. I gather a lot of motivation from others around me.”

In contrast, a few students mentioned that the COVID-19 pandemic improved or enhanced their learning. These students gave examples of increased flexibility, the ability to learn at one's own pace, and feeling like they had more time to study due to the remote delivery of classes. With changes to assessment this student mentioned, “I found my stress level to have gone down as all of the courses were changed to pass/fail instead of by grades.”

Question 2: from a pharmacy and pharmacy school perspective, what have you learned since the COVID-19 pandemic began?

Students' responses to this question were comparable to their responses in Question 1. Similarly, most responses expressed the negative impact on learning with some students even saying they learned “barely anything” and the “lack of formality of online lectures made [them] take it less seriously.” Students also reiterated that learning from home had several distractions.

When students discussed knowledge transfer with the remote delivery of courses, the underlying commonality between responses was a lack of interaction. One student explained, “… we really learn the best by interacting. We would come up with mini cases or study together and ask questions, come up with hypothetical scenarios for treatment options, etc. Pharmacy needs that interactive portion and relies on the connections students have with one another to really get the most out of learning the type of material we learn.” This interactive component to learning also appeared when students mentioned their retention of information taught in class. This student expressed, “… I learn better and retain the information better during [in-class] lectures and from discussions with my colleagues after class.”

With regard to changes in assessment due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students appreciated assignments and exams being altered to better reflect being taught remotely. This student said, “I did like the small online quizzes and assignments that we did after readings. I thought they were engaging and helped us review and keep track of some progress. I liked this more than some closed-book assignments we had gotten in class that we got graded on. This is because I was able to take my time open-book and do my research or study at the same time.” Similar to responses in Question 1, one student noted, “It was definitely nice having open book exams but I feel like it made me study less.”

When students were asked what they have learned since the COVID-19 pandemic began from a pharmacy school perspective, students mentioned several more aspects of how their mental health was impacted. Most of the responses focused on the need to have work-life balance by separating school from home. As one student stated, “I like having to travel to school, a place where I should focus on work [ ], then come home to play.” Students also said that virtual interactions with their peers do not replace in-person socializing and studying, and that “physical interaction with peers and professors allows [them] to be more motivated and engaged in learning.”

An additional theme from Question 2 that was not identified in Question 1 includes the role of the pharmacist. From a pharmacy practice perspective, students felt that the pandemic clarified the role of the pharmacist during a disaster and the importance of being an accessible and trusted health care professional that can discern the truth by “debunking myths and ensuring that patients are properly cared for.” One student, who was not working in a pharmacy at the time of the pandemic, felt that “[professors] should have taught us more about the pandemic [in class].”

Question 3: from a personal perspective, what have you learned about yourself since the COVID-19 pandemic began?

In this final reflection question, the new themes of adaptability and routine emerged. Students gave general statements on how they have adapted to changes in their life caused by the pandemic such as, “I struggled with finding a ‘new normal’ for myself at the beginning of this pandemic, but have adjusted to something now with a lot of support from my peers.” And “I feel that in a way, [the pandemic has] been a good learning experience, as it taught me to adapt to my surroundings, whatever they may be.”

Although most students expressed a new-found adaptability, several students said they struggled with changes to their daily routine. One student explained “I learned that I [ ] need structure to be productive.” And another said, “I find I need to stick to some form of routine to ensure any kind of productivity throughout my day.” However, one student mentioned that they “learned [to] be more independent [and] accountable when [they] don't have friends/teachers reminding [them] in person to get an assignment done or finish a task.”

Two new sub-themes of mental health were identified from this third reflection question wherein students expressed appreciation of educational and lifestyle freedoms prior to the pandemic and realized how extroverted they truly are. “I learned to be more appreciative of small things in my life and learned to not take everything in my life for granted,” one student said. Several students noted they were more social than they previously thought. One explicitly stated, “I'm more extroverted than I once thought” and recognized that the social aspect of being on campus and learning in a classroom should not be taken for granted as “socializing is a necessity to become successful in school.”

Students also stated that their professional identity was enhanced. Several students noted that they have a better understanding of “how important [their] role in society is as a future pharmacist” and that “pharmacists are essential … in emergency healthcare situations.” And because of this, one student said, “I feel proud to be in this profession [and] inspire[d] to be an extraordinary pharmacist.” Another student wrote, “I feel that the COVID pandemic has enhanced my professional identity as I am increasingly needed at work to provide the duties of a pharmacist under [direct] supervision. I have had to utilize enhanced scope activities such as renewing controlled substances and therefore achieved better learning and self-confidence.” Comparably, one student who was not working in a pharmacy at the time of the pandemic noted that they felt useless: “… here I am, a person with some skill in health care, just sitting at home during a crisis” (in response to Question 1).

Discussion

This evaluation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy students' educational and professional learning is the first study of its kind in Canada. The survey identified major and minor themes implicated in the individual perspectives of a small but representative sample of the pharmacy student population at the University of Alberta. Major themes comprised remote learning and mental health with sub-themes of learning environment, knowledge transfer, knowledge retention, and assessment along with appreciation, stress, extroversion, and motivation, respectively. In addition, minor themes included adaptability, routine, professional identity, and the role of the pharmacist.

As elucidated in students' responses, the identified themes are interconnected and therefore must not be interpreted individually. Students expressed that their ability to retain the information taught remotely was influenced by their (home) learning environment, the way the knowledge was transferred in the lecture, and the type of assessment used. The remote delivery and time of social isolation also impacted students' motivation, which likely influenced their perception of how well they were learning the material. Overall, these changes made students feel that they did not learn as much compared to when classes were taught in person.

However, it has been shown that students' perception of their learning is not a good predictor of their true knowledge or performance and that when under acute stress, self-assessment of performance is negatively impacted.7 While considering this, there is emerging evidence of learning loss due to the COVID-19 pandemic.8 Early trajectories of the predicted learning loss of kindergarten to grade 12 students estimate that these students will be starting the 2020 fall semester with 70% of the reading and 50% of the mathematics skills they would have gained from the year prior under normal circumstances.8 If these early trajectories are true, the actual impact of the pandemic will not be realized for years. Therefore, it will be important to longitudinally follow this cohort and, for pharmacy students, to compare their performance on the PEBC standardized licensing exam to past cohorts. Ideally, this cohort of pharmacy students would also be followed with respect to their professional success, including the utilization of their full scope of practice, development of leadership skills, and achievement of work-life balance.9

The extensive shifts required due to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated to pharmacy students the importance of maintaining their mental health, being able to adapt to change, and the value of socialization in supporting their education through various learning opportunities. This result was no surprise as globally, everyone is experiencing the same “loss of normalcy” and “loss of connection” due to the COVID-19 pandemic.10 Research has shown that Canadian university teachers also feel an increase in anxiety and stress due to aspects of the pandemic including the loss of face-to-face teaching and work-life balance.11

Our study found that aspects of pharmacy students' stress included challenges with remote learning and overall uncertainty brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Students felt that the value of the education they received remotely was not comparable to that received through face-to-face lectures. This negative view of remote learning is shared by many post-secondary students across Canada and is a factor when considering postponing education continuation in the 2020–2021 academic year.12 However, a factor of stress that was not identified in our study but was prevalent in a survey of other post-secondary students across Canada includes the financial impact of the pandemic and ability to afford to continue their education.12 Although pharmacy students expressed unpredictability as a factor of their stress, finances were not mentioned. One explanation for this could be that pharmacy students' jobs were not negatively impacted by the pandemic as many pharmacies were hiring more students to help with the increased demand of healthcare services and pharmacist scope of practice in Alberta during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regard to pharmacy practice, our study found that pharmacy students' self-confidence and knowledge of a pharmacist's role during a disaster was deepened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, new research shows that neither pharmacy students nor practicing pharmacists are prepared to respond to a disaster.13 This may be due to a lack of education on disaster response or the absence of pharmacists in local and national disaster planning.13 This provides an opportunity for positive change, whereby pharmacy educators better prepare students for their role in environmental and healthcare disaster response.

There were several other identified opportunities for positive change at the university level to enhance future pharmacy students' learning and experience. First, recording future in-person lectures would allow students to learn at their own pace and increase flexibility with when and how students go through lectures. Next, ensuring pharmacy students have mental health support available is paramount. This is supported by a study on the mental health impact of COVID-19 on pre-registration nursing students in Australia, which recommends students and academic staff participation in virtual social events to stay connected during social isolation, university counselling service reminders, and provision of reliable information about COVID-19 and related changes to teaching and assessment structure.14

This study is not without limitations. The low response rate and subsequent small sample size may decrease the generalizability of our results. However, considering the saturation of theme identification and overlap of identified themes between questions, any larger sample size or increase in response rate is unlikely to change the results. There is also the possibility of response bias as the topics that students discussed in their questionnaire answers may have been influenced by the way the questions were worded or by the prompts given to clarify each question. However, every student's response uniquely elaborated on the theme, forming the basis for the content analysis.

Conclusions

This study uncovered the perception of changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic that pharmacy students at the University of Alberta hold. Responses to the cross-sectional survey revealed that the most prevalent contributor to pharmacy students' learning during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with the switch to remote delivery of classes as well as students' mental health. Although the long-term personal and professional implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy students will not be seen for several years, increased understanding of student perceptions has the potential to improve the delivery of remote education, support increased university-wide mental health resourcing, and shape pharmacy curriculum development. Further, this study is the basis of future research to determine the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy students' academic achievement and professional success.

Author statement

Danielle Nagy has no conflicts to disclose with regards to research funding or products in this manuscript. Danielle has no prior relationship with CPTL.

Jill Hall has no conflicts to disclose with regards to research funding or products in this manuscript. Jill has no prior relationship with CPTL.

Theresa Charrois has no conflicts to disclose with regards to research funding. Theresa is on the editorial board of CPTL.

Disclosure(s)

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Danielle Nagy received funding in part by the Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management, jointly held by the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta.

References

- 1.Pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice. Canadian Pharmacists Association; January 2021. https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/scope-of-practice-canada/ Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subsection 56(1) class exemption for patients, practitioners and pharmacists prescribing and providing controlled substances in Canada during the coronavirus pandemic. Government of Canada; 30 September 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/controlled-substances-precursor-chemicals/policy-regulations/policy-documents/section-56-1-class-exemption-patients-pharmacists-practitioners-controlled-substances-covid-19-pandemic.html Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharmacy benefact number 847. Alberta Blue Cross; March 2020. https://www.ab.bluecross.ca/pdfs/pharmacy-benefacts/pharmacy-benefact-847.pdf Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajab M.H., Gazal A.M., Alkattan K. Challenges to online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castleberry A., Nolen A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data : is it as easy as it sounds? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(6):807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin R.K. 2011. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persky A.M., Lee E., Schlesselman L.S. Perception of learning versus performance as outcome measures of educational research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(7):ajpe7782. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soland J., Kuhfeld M., Tarasawa B., Johnson A., Ruzek E., Liu J. Brown Center Chalkboard; 27 May 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on student achievement and what it may mean for educators.https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2020/05/27/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-student-achievement-and-what-it-may-mean-for-educators/ Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward A., Hall J., Mutch J., Cheung L., Cor M.K., Charrois T.L. What makes pharmacists successful? an investigation of personal characteristics. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2019;59(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2018.09.001. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berinato S. Harvard Business Review; 23 March 2020. That discomfort you’re feeling is grief.https://hbr.org/2020/03/that-discomfort-youre-feeling-is-grief Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.What impact is the pandemic having on post-secondary teachers and staff? Canadian Association of University Teachers; 2020. https://www.caut.ca/sites/default/files/covid_release-impacts_of_pandemic-en-final-08-19-20.pdf Accessed 9 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Survey: post-secondary students reconsidering fall semester plans in wake of COVID-19. Canadian Association of University Teachers; 12 May 2020. https://www.caut.ca/latest/2020/05/survey-post-secondary-students-reconsidering-fall-semester-plans-wake-covid-19 Accessed 8 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCourt E., Singleton J., Tippett V., Nissen L. Disaster preparedness amongst pharmacists and pharmacy students: a systematic literature review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2021;29(1):12–20. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usher K., Wynaden D., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Jackson D. The mental health impact of COVID-19 on pre-registration nursing students in Australia. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(6):1015–1017. doi: 10.1111/inm.12791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]