Abstract

Background

Different common gene variants were related to coronary artery disease (CAD) in many studies. Yet, the relation of these loci to the severity of CAD is not completely elucidated.

Methods

We enrolled 520 subjects (315 CAD cases and 205 controls). CAD presence and extension were assessed by coronary angiography (CAG). Genotyping of five SNPs (namely, rs2230806 (1051G > A) in ABCA1 on chromosome 9, rs2075291 (553G > T) in ApoA5 on chromosome 11, rs320 in LPL on chromosome 8 intron (T → G at position 481), rs10757278 (c.22114477A > G), and rs2383206 (c.22115026 A > G) on chromosome 9p21 locus) was performed by allele-specific PCR. The degree and site of arterial lesions were used to classify patients, tested for association with CAD severity, and related to allele dosage.

Results

The polymorphisms rs2383206 and rs10757278 showed significant associations with 2- and 3-vessel coronary disease (p =0.003 and 0.006, respectively). The homozygous GG genotypes of rs10757278 was associated with higher frequency of left anterior descending (LAD), right coronary artery (RCA) and left circumflex (LCX) diseases (p =0.002, 0.016 and 0.002, respectively). The GG genotypes of rs2383206 were found in higher percentage in patients with left main (LM) trunk and left circumflex (LCX) diseases (p = 0.013 and 0.002, respectively).

Conclusion

SNPs rs10757278 and rs2383206 allele dosage could predict CAD severity in the Saudi Arab population.

1. Introduction

Despite major advances in patient management, coronary artery disease (CAD) remains a leading cause of death worldwide [1]. CAD underlies a composite group of syndromes caused by partial or complete cardiac muscle regional ischemia as a result of temporary or permanent cessation of blood flow in one or more of coronary arteries [2]. These can be diagnosed by clinical, laboratory, and angiographic assessment of the patients suffering from chest pain [3].

Coronary angiography is a technique that uses contrast dye, containing iodine, and X-ray images to detect coronary artery stenosis that is caused by atheromatous plaque development and/or rupture [4, 5]. The plaque pathogenesis is a complex, multistep, and multietiological process [6]. Genetic bases of this process have been recently studied in a wide series of genome-wide association studies [7–11].

Former studies proved that different genetic variants were associated with the major traditional risk factors of CAD [12–15]. Interestingly, genetic factors have been shown to increase the risk of early-onset CAD [12, 16, 17]. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms and genetic predisposition to the disease could permit early detection of individuals at higher risk for CAD, and this, in turn, could pave the way to targeted preventive therapies [18–20]. Several genetic loci on chromosome 9p21.3 and other chromosomes are claimed to have a prominent role in CAD development [21–24].

To the best of our knowledge, few works in the literature studied the relation between genetic risk of CAD and severity indices of the disease [25, 26]. Our objective is to spot the light on angiographic indices of CAD severity in relation to relevant genetic variants in the Saudi Arab population. Five SNPs at 3 loci were selected according to data from previous literature, as they had shown a strong relation with CAD risk [27–36]. We investigated their relation to the disease severity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

Our study is a prospective case-control study on unrelated Arab individuals in Saudi Arabia. Three hundred and fifteen consecutive CAD patients between 30 and 85 years of age were enrolled from the Noor Specialty Hospital (NSH) and King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC) of Mecca. All patients underwent coronary angiography on admission. The number of coronary vessels affected and the degree of atherosclerotic lesions were assessed. CAD patients were classified according to their angiographic data into 2 groups, group I (nonobstructive CAD) with nonsignificant lesions, i.e., stenosis < 50%, consists of 32 patients, and group II (obstructive CAD) consists of 283 patients, i.e., with stenosis ≥ 50% (significant lesions) in at least one main coronary artery. Group II (obstructive CAD) was further subdivided into 3 subgroups according to the number of vessels affected.

Population-based control individuals (n = 205) were enrolled in the study after filling a questionnaire upon voluntary blood donation. A detailed medical history and a complete clinical examination were performed, along with vital signs and anthropometric measurements, to rule out cardiac problems.

We exclude patients with autoimmune diseases, cancer, and other comorbidities that may affect variables under study.

The body mass index (BMI) cut-points were as specified by the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. It was computed by dividing the weight (kg) by square height (m2) [37]. History of hypertension (HTN) was confirmed by assessing systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP): an SBP of ≥140 and/or a DPB ≥ 90 mmHg was considered indicative of HTN. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was defined according to WHO criteria [38]. Dyslipidemia was diagnosed according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria [39].

The procedure of the study was authorized by the Institutional Review Boards of the Umm Al-Qura University (UQU) (43430838) and KAMC (IRB number 13-043). Written consent was obtained from each participant.

2.2. Angiography

The coronary angiograms were reviewed blindly to genotype results by 2 independent cardiologists. Stenosis in any vessel ≥ 50% was considered as significant. Left main disease was defined as stenosis ≥ 50% in a nonbypassed vessel. Protected left main disease was excluded from analysis, as causing enhanced atherosclerosis in the segments proximal to a bypass anastomosis. [40]

2.3. Biochemical Assays

We collected two tubes of peripheral blood from each subject, an EDTA-tube for DNA extraction and a plain tube for glucose and lipids biochemical assay. The biochemical tests were performed at KAMC clinical chemistry lab. The genetic study was done at Umm Al-Qura University biomedical labs.

2.4. Genotyping

Five SNPs at 3 loci were studied: rs320 in lipoprotein lipase (LPL) on chromosome 8 intron (T → G at position 481); rs2230806 (1051G > A) in ABCA1, rs10757278 (c.22114477A > G), and rs2383206 (c.22115026 A > G) on chromosome 9; and rs2075291 (553G > T) in ApoA5 on chromosome 11.

Following the manufacturer's protocol, DNA extraction was performed from whole blood samples of all subjects, using the EZ1 DNA Blood 350 μl Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A NanoDrop spectrophotometer was used to assess DNA concentration and purity. Allele-specific PCR amplification was used for genotyping. Primer design allowed specific amplification of the reference and minor alleles. TaqMan MGB probe and allele-specific primers were provided on demand (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). We performed the 5′ nuclease assay by using 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1× primer/probe mix, and 1× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions needed for amplification were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test examines if variables are normally distributed.

Mean ± standard deviation was used to express normally distributed quantitative continuous data, while median ± interquartile range (IQR) was used to express nonnormally distributed continuous data. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical data.

Student's t-test and ANOVA were used to assess differences in continuous variables among groups, as appropriate. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare nonnormally distributed variables. We assessed the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and compared genotype distribution and allele frequencies between the study groups by 2 × 2 contingency tables and χ2 test. Logistic regression analysis was performed and adjusted for confounders to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI and corresponding p values, with minor homozygous allele as the reference group. Two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The SPSS program for Windows was used for statistical analysis (version 23; Texas instruments, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

Patients (n = 315) with angiographically confirmed CAD were enrolled. Male patients represent 62.2% of the cohort. The mean age of cases was 59.2 ± 10.5 years.

Characteristics of the demographic and clinical parameters of cases and controls are presented in Table 1. Risk factors were significantly more frequent and/or higher in obstructive-CAD patients when compared with either nonobstructive CAD patients or controls. Dyslipidemia and hypertension frequencies were lower in controls, but more similar between nonobstructive and obstructive CAD patients.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of study groups.

| Control (n = 205) | Nonobstructive CAD (n = 32) | Obstructive CAD (n = 283) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 58.4 ± 9.28 | 58.7 ± 10.4 | 59.3 ± 10.5 |

| Male (n (%)) | 119 (58%) | 27 (90%) | 244 (60.1%)† |

| B. Clinical parameters | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.26 (6.49) | 28.2 ± 4.0§ | 28.5 ± 5.0§ |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128.2 ± 5.8 | 140.5 ± 9.4§ | 143.1 ± 9.9§ |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.3 ± 2.8 | 83.3 ± 3.7§ | 85.0 ± 4.0§ |

| Previous stroke (%) | 7 (3.4%) | 4 (13.3%)∗ | 75 (18.5%)§ |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 35 (17.1%) | 13 (43.3%)§ | 198 (48.8%)§ |

| Current smokers (%) | 72 (35.1%) | 27 (90%)§ | 164 (40.4%)‡ |

| Exercise (%) | 67 (32.7%) | 10 (33.3%)§ | 104 (25.6%)‡ |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) | 138.3 ± 6.2 | 146.6 ± 8.6∗ | 163.9 ± 8.1§ |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl)# | 177.9 ± 69.9 | 241.4 ± 4.7§ | 242.3 ± 7.5§ |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 38.7 ± 10.4 | 39.1 ± 2.0§ | 38.7 ± 2.4§ |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 91.9 ± 3.9 | 174.2 ± 4.3§ | 185.2 ± 4.9§ |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl)# | 191.2 ± 4.1 | 225.2 ± 5.2§ | 237.9 ± 6.9†§ |

Student t test and X2 test between obstructive CAD and either control groups. #Mann–Whitney U test vs. control group: ∗p < 0.01, §p < 0.001 vs. subjects with nonobstructive CAD: ‡p < 0.01, †p < 0.001.

Patients with 1-vessel, 2-vessel, and 3-vessel disease were 55 (19.5%), 104 (36.7%), and 124 (43.8%), respectively. The percent of patients with left main (LM) disease was 8.7%, with left anterior descending (LAD) lesions 76.8%, with right coronary artery (RCA) lesions 67.2%, and with left circumflex (LCX) lesions 51.6%.

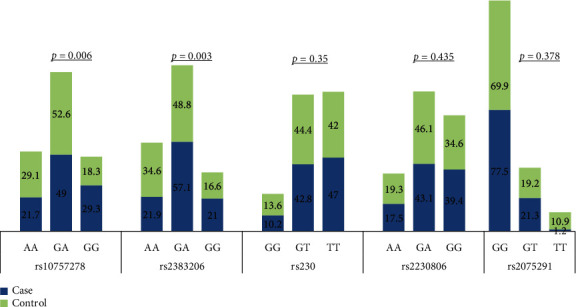

3.2. Genotype Frequencies

In the population studied, there was no significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (p > 0.05) for all examined polymorphisms. We observed a significant difference in the frequency distribution of the genotypes of rs10757278 and rs2383206 among cases and controls (p = 0.006 and p = 0.003, respectively), as shown in Figure 1. Conversely, genotype distribution was not significantly different for rs320, rs2230806, and rs2075291 between cases and controls with no history of CAD (p = 0.353, p = 0.435, and p = 0.378, respectively). Data is available as (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Genotype distribution among CAD patients and controls.

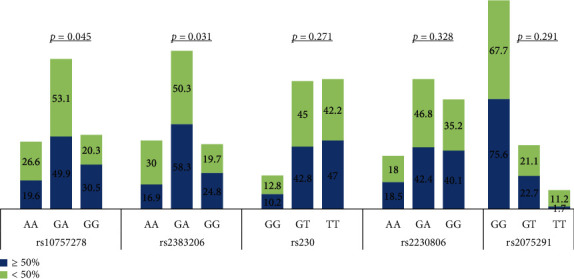

Genotype distribution of rs10757278 and rs2383206 showed significant differences also when comparing group I and group II patients (p = 0.045 and 0.031, respectively). The differences in genotype distribution were not significant for the remaining SNPs (Figure 2). Data is available as (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 2.

Genotype distribution among CAD patients according to the severity of angiographic stenosis.

3.3. Genetic Alleles and Risk for Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease

Genetic association of the minor alleles was assessed by calculating the OR along with CI 95% for all SNPs. The G allele of rs10757278 was found to increase the odds of CAD among cases when compared to controls by 1.409 folds (95%CI = [1.131 − 1.756]; p = 0.001). The risk was increased to 3.38 folds when the OR was calculated comparing CAD cases with nonobstructive CAD subjects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk alleles in CAD subjects compared with control groups.

| SNP variant | Risk allele OR (95% CI) Obstructive CAD/control |

p | Risk allele OR (95% CI) Obstructive/nonobstructive CAD |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10757278 | 1.409 (1.131–1.756) | 0.001 | 3.38 (1.231–6.341) | 0.006 |

| rs2383206 | 1.413 (1.009–1.718) | 0.004 | 2.925 (1.132–4.562) | 0.012 |

| rs320 | 0.826 (0.635–1.074) | 0.087 | 1.262 (0.973–2.326) | 0.151 |

| rs2230806 | 1.253 (0.761–1.941) | 0.091 | 1.430 (0.901–2.182) | 0.163 |

| rs2075291 | 0.564 (0.327–0.132) | 0.128 | 0.705 (0.561–0.182) | 0.231 |

Also, the G allele of rs2383206 was found to increase the odds of CAD among cases when compared to controls by 1.413 folds (95%CI = [1.099 − 1.817]; p = 0.004). The risk was increased to 2.925 folds when the OR was calculated comparing obstructive vs. nonobstructive CAD (Table 2).

The other SNPs investigated did not reveal any significant association between genetic variants with CAD risk among the study subjects.

3.4. Risk Assessment for the Severity of CAD Lesion

Binary logistic regression test comparing subjects with significant lesions vs. nonsignificant ones detected several independent variables that increase the risk of stenosis. After adjusting confounding factors, regression analysis showed that smoking (OR = 2.81, p = 0.032), diabetes (OR = 1.92, p = 0.041), and the G allele of rs10757278 and rs2383206 (OR = 1.82 and 2.41, p = 0.015 and 0.036, respectively) increased the risk of coronary stenosis independently of the other variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors contributing to the severity of CAD.

| Variable | B | SE | p | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10757278 G | 0.273 | 0.117 | 0.015 | 1.82 | (1.17-2.57) |

| rs2383206 G | 0.332 | 0.142 | 0.003 | 2.41 | (1.31-3.53) |

| Smoking (current + ever) | 0.782 | 0.139 | 0.032 | 2.81 | (1.52-4.03) |

| DM | 0.853 | 0.171 | 0.041 | 1.92 | (1.23-2.71) |

CAD: coronary artery disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

3.5. Association between Genotypes and the Number and Location of Coronary Lesions

A strong relation between the dosage of the G allele of rs10757278 and the number of diseased vessels in obstructive CAD patients (Table 4). Results showed that individuals with rs10757278 GG genotype had a significantly higher chance of getting 2- or 3-vessel disease (p ≤ 0.001; OR = 1.952, 95% CI: 1.131–3.348 and p = 0.006; OR = 2.854, 95% CI: 1.264–6.192, respectively). Conversely, no significant association was found between rs10757278 G allele dosage and 1-vessel disease. Higher rates of LAD stenosis (p = 0.001, OR = 2.284, 95%CI = 1.271–3.521), RCA stenosis (p = 0.004, OR = 1.261, 95%CI = 1.241–3.318), and LCX stenosis (p = 0.002, OR = 1.121, 95%CI = 1.041–2.261) were found in GG genotype subjects (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between SNP rs10757278 genotypes and severity of CAD.

| Reference genotype | AG | GG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Number of lesions | 1VD | AA | 0.720 | 0.365-1.397 | 0.401 | 1.207 | 0.635-2.243 | 0.260 |

| 2VD | AA | 0.787 | 0.351-1.533 | 0.541 | 1.952 | 1.131-3.348 | ≤0.001 | |

| 3VD | AA | 1.207 | 0.591-3.421 | 0.129 | 2.854 | 1.264-6.192 | 0.006 | |

| Location of lesions | LM stenosis | AA | 2.254 | 0.510-9.964 | 0.265 | 3.478 | 0.674-11.262 | 0.115 |

| LAD stenosis | AA | 1.109 | 0.619-1.701 | 0.691 | 2.284 | 1.271-3.521 | 0.001 | |

| RCA stenosis | AA | 1.044 | 0.505-1.651 | 0.845 | 1.261 | 1.241-3.318 | 0.004 | |

| LCX stenosis | AA | 1.119 | 0.581-1.705 | 0.677 | 1.121 | 1.041 – 2.261 | 0.002 | |

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; CAD: coronary artery diseases; VD: vessel disease; LM: left main; LAD: left anterior descending; RCA: right coronary artery; LCX: left circumflex.

Similar strong associations were found for the GG genotype of rs2383206 with CAD patients with two or three-vessel disease (p = 0.004, OR = 1.723, 95% CI: 1.328-3.452 and p = 0.003, OR = 1.862, 95% CI: 1.175-4.153, respectively), but not with 1-vessel disease (Supplementary Table S3). The GG genotype is found to be associated more with LM stenosis (p = 0.013, OR = 2.382, 95%CI = 1.061–4.812) and LCX stenosis (p = 0.002, OR = 2.512, 95%CI = 1.437–4.038) (Supplementary Table S3).

4. Discussion

In our study, CAD cases and controls were precisely stratified according to the angiographic estimation of the number and/or degree of stenosis of coronary artery lesions. The severity of CAD was assessed angiographically as the number and degree of coronary artery stenosis. Association between genetic variants and different risk factors was assessed by careful clinical and biochemical characterization of study subjects. Our results showed a significant association between risk allele frequency of SNPs rs10757278 and rs2383206 and CAD angiographic severity.

Our findings are consistent with different GWAS that proved an association of 9p21 locus polymorphism and CAD in different ethnic groups [7, 41–45]. McPherson et al. described two SNPs (rs10757274 and rs2383206) on the 9p21 chromosome that were found to be in association with CAD among Caucasians [43]. Helgadottir et al. showed that almost 21% of subjects of European ancestry carry a homozygous genotype for rs10757278-G and assessed a risk of 1.64-fold higher than the noncarriers to have MI [42]. Shen et al. considered 4 SNPs in Korean population on chromosome 9p21, which were found related to CAD (rs2383206 and rs10757274) and MI (rs10757278 and rs2383207). They defined CAD severity as ≥70% coronary stenosis and characterized a greater cross-race risk for CAD development [46].

A collaborative meta-analysis, including 21 studies, investigated the association between the chromosome 9p21 locus and the burden of angiographic CAD [47]. Risk allele homozygotes are 23% more prone to multivessel disease than to single-vessel disease when compared with nonrisk allele homozygotes. Our results in a Saudi Arab cohort concerning 2 SNPs on chromosome 9p21 locus go in parallel with their findings.

For the ABCA1 R219K variant (+1051GA, rs2230806), we did not find any significant difference in genotype distribution or association with disease risk and/or severity between patients and controls. This is in line with Takagi et al. who concluded that the polymorphism does not seem to influence coronary atherosclerosis [48]. On the contrary, a meta-analysis including 2658 controls and 2730 CAD patients found that the ABCA1 gene K allele had a significant role in protecting against the risk of CAD in Chinese and was associated with decreased CAD susceptibility [49]. Indeed, several studies highlighted a protective effect of the rs2230806 polymorphism [50, 51]. On the opposite side, Brousseau et al. found that rs2230806 could potentiate the development of CAD [52]. Abd El-Aziz et al. found that the ABCA1 gene R allele was associated with premature CAD in the Egyptian population: the SNP had an apparent impact on patients with low HDLc [53].

The SNP rs2075291 (553G > T) is a rare APOA5 gene variant. Our results matched a large meta-analysis that included 3 studies with 9,518 subjects, which found no association between rs2075291 (553G > T) gene polymorphism and risk of CHD [54]. Besides, the SNP rs2075291 was found to be correlated with triglycerides and total cholesterol serum levels in Chinese Han population [55]. An association between rs2075291 polymorphism and CHD was found to be significant in Taiwan and Nanjing cohorts [56, 57].

We found no difference in LPL polymorphisms genotype distribution between the control and CAD group. Thus, rs320 could not be considered as independent CAD risk factors in our population. These results go in parallel with others in different regions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [33, 35, 36], but do not replicate the results Al-Jafari et al. who found a significant association between this polymorphism and the risk of CAD [34]. An Indian study strongly suggested that the homozygous genotype of rs320 on the LPL gene is an independent risk factor for first MI [58].

In conclusion, our study confirmed that the presence of the G allele in rs10757278 and rs2383206 was significantly associated with multivessel CAD, while rs2230806, rs2075291, and rs320 did not significantly affect CAD.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association of 5 CAD-associated SNPs with the occurrence, extent, and severity of the disease. We had to acknowledge some limitations of our research. Linkage study could not be performed among the 5 loci under study due to their positions on different chromosomes. Increasing the number of SNPs in the same chromosome in further research could help to perform linkage analysis. Another limitation is that we did not classify CAD patients clinically. Other research encompassed several clinical CAD presentations including MI, calcification in coronary arteries, or angiographic CAD plus MI history. Further prospective cohort studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our results and evaluate the prognosis and degree of atherosclerosis progression.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Ahmed Shawky and the staff of the Science and Technology Unit (STU) and Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm-Al-Qura University, Makkah, and Innovation (MAARIFAH)-King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology-the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for their support, Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University, as well as the Monzino Heart Center, the University of Milan, Milan, Italy, the King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital and King Abdullah Medical City Makkah for their continuous support. The authors also acknowledge the support of Dr. Ahmed Fawzy, Dr. Dareen Ibrahim Rednah, Dr. Saad Alghamdi, Dr. Khalid Faruqui, Dr. Enas Alharthi, and Dr. Elaf Almatrouk. We all are deeply appreciative of Mr. Soud Abdulraof A Khogeer, Mr. Abdulmonim Gowda, Mr. Sami Kalantan, Mr. Mustafa N Bogari, Miss Dema N Bogari, Mr. Ehab Melibary, and Mr. Abdulaziz Alhussini from the Department of Biochemistry, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, KSA.

Contributor Information

Neda M. Bogari, Email: nmbogari@uqu.edu.sa.

Reem M. Allam, Email: rmallam@medicine.zu.edu.eg.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest concerning this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables describing genotype distribution among CAD patients and controls, genotype distribution among CAD patients according to the severity of angiographic stenosis, and association between SNP rs2383206 genotypes and CAD severity are included.

References

- 1.Nabel E. G., Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(1):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kop W. J. Chronic and acute psychological risk factors for clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61(4):476–487. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugiardini R., Badimon L., Collins P., et al. Angina, “normal” coronary angiography, and vascular dysfunction: risk assessment strategies. PLoS medicine. 2007;4(2):p. e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campeau L. Percutaneous radial artery approach for coronary angiography. Catheterization and cardiovascular diagnosis. 1989;16(1):3–7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zir L. M., Miller S. W., Dinsmore R. E., Gilbert J., Harthorne J. Interobserver variability in coronary angiography. Circulation. 1976;53(4):627–632. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.53.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallika V., Goswami B., Rajappa M. Atherosclerosis pathophysiology and the role of novel risk factors: a clinicobiochemical perspective. Angiology. 2007;58(5):513–522. doi: 10.1177/0003319707303443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baudhuin L. M. Genetics of coronary artery disease: focus on genome-wide association studies. American journal of translational research. 2009;1(3):221–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly P. Progress and challenges in genome-wide association studies in humans. Nature. 2008;456(7223):728–731. doi: 10.1038/nature07631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotta L. A. Genome-wide association studies in atherothrombosis. European journal of internal medicine. 2010;21(2):74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy M. I., Abecasis G. R., Cardon L. R., et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nature reviews genetics. 2008;9(5):356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prins B. P., Lagou V., Asselbergs F. W., Snieder H., Fu J. Genetics of coronary artery disease: genome-wide association studies and beyond. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghassibe-Sabbagh M., Platt D. E., Youhanna S., et al. Genetic and environmental influences on total plasma homocysteine and its role in coronary artery disease risk. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222(1):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotger M., Glass T. R., Junier T., et al. Contribution of genetic background, traditional risk factors, and HIV-related factors to coronary artery disease events in HIV-positive persons. Clinical infectious diseases. 2013;57(1):112–121. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson P. W. Established risk factors and coronary artery disease: the Framingham Study. American journal of hypertension. 1994;7(7_Part_2):7S–12S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.7.7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balashanmugam M. V., Shivanandappa T. B., Nagarethinam S., Vastrad B., Vastrad C. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Coronary Artery Disease by Integrated Microarray Analysis. Biomolecules. 2019;10(1):p. 35. doi: 10.3390/biom10010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauser E. R., Crossman D. C., Granger C. B., et al. A genomewide scan for early-onset coronary artery disease in 438 families: the GENECARD Study. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;75(3):436–447. doi: 10.1086/423900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheuner M. T. Genetic evaluation for coronary artery disease. Genetics in Medicine. 2003;5(4):269–285. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000079364.98247.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albuquerque D., Stice E., Rodríguez-López R., Manco L., Nóbrega C. Current review of genetics of human obesity: from molecular mechanisms to an evolutionary perspective. Molecular genetics and genomics. 2015;290(4):1191–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsburg G. S., McCarthy J. J. Personalized medicine: revolutionizing drug discovery and patient care. TRENDS in Biotechnology. 2001;19(12):491–496. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(01)01814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suh Y., Vijg J. SNP discovery in associating genetic variation with human disease phenotypes. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2005;573(1-2):41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium I. K. C. Large-scale gene-centric analysis identifies novel variants for coronary artery disease. PLoS genetics. 2011;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorn G. W., Cresci S. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Coronary Artery Disease and Heart Failure: Where Are We Going? Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10(2):213–223. doi: 10.2217/14622416.10.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muendlein A., Saely C. H., Rhomberg S., et al. Evaluation of the association of genetic variants on the chromosomal loci 9p21. 3, 6q25. 1, and 2q36. 3 with angiographically characterized coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205(1):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel R. S., Su S., Neeland I. J., et al. The chromosome 9p21 risk locus is associated with angiographic severity and progression of coronary artery disease. European heart journal. 2010;31(24):3017–3023. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S. N., Ballantyne C. M., Gotto A. M., Marian A. J. The 9p21 susceptibility locus for coronary artery disease and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2009;9(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dandona S., Stewart A. F. R., Chen L., et al. Gene dosage of the common variant 9p21 predicts severity of coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56(6):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogari N., Dannoun A., Athar M., et al. Genetic association of rs 10757278 on chromosome 9p21 and coronary artery disease in a Saudi population. International Journal of General Medicine. 2021;Volume 14:1699–1707. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S300463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogari N. M., Aljohani A., Amin A. A., et al. A genetic variant c. 553G> T (rs2075291) in the apolipoprotein A5 gene is associated with altered triglycerides levels in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients with lipid lowering drug. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2019;19(1):p. 2. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogari N. M., Aljohani A., Dannoun A., et al. Association between HindIII (rs320) variant in the lipoprotein lipase gene and the presence of coronary artery disease and stroke among the Saudi population. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020;27(8):2018–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neda Bogari D. R., Elkhateeb O., Dannoun A. I., et al. Obesity is associated with cardiac disease and the apo lipoprotein A5 gene a genetic variant C.553g > T is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. International Conference on Obesity and Chronic Diseases (ICOCD-2016); 2016; Las Vegas, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogari N. M., Aljohani A., Amin A. A., et al. Intronic polymorphisms in the CDKN2B-AS1 gene are strongly associated with the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease in the Saudi population. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016;17(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms17030395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan Q., Zhu Y., Zhao F. Association of rs2230806 in ABCA1 with coronary artery disease: an updated meta-analysis based on 43 research studies. Medicine. 2020;99(4) doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abu-Amero K. K., Wyngaard C. A., Al-Boudari O. M., Kambouris M., Dzimiri N. Lack of association of lipoprotein lipase gene polymorphisms with coronary artery disease in the Saudi Arab population. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2003;127(5):597–600. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-0597-LOAOLL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Jafari A. A., Daoud M. S., Mobeirek A. F., Al Anazi M. S. DNA polymorphisms of the lipoprotein lipase gene and their association with coronary artery disease in the Saudi population. International journal of molecular sciences. 2012;13(6):7559–7574. doi: 10.3390/ijms13067559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmadi Z., Senemar S., Toosi S., Radmanesh S. The association of lipoprotein lipase genes, HindIII and S447X polymorphisms with coronary artery disease in Shiraz city. Journal of cardiovascular and thoracic research. 2015;7(2):63–67. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daoud M. S., Ataya F. S., Fouad D., Alhazzani A., Shehata A. I., Al-Jafari A. A. Associations of three lipoprotein lipase gene polymorphisms, lipid profiles and coronary artery disease. Biomedical reports. 2013;1(4):573–582. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Lorenzo A., Deurenberg P., Pietrantuono M., Di Daniele N., Cervelli V., Andreoli A. How fat is obese? Acta diabetologica. 2003;40(S1):s254–s257. doi: 10.1007/s00592-003-0079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deckers J. G., Schellevis F. G., Fleming D. M. WHO diagnostic criteria as a validation tool for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a study in five European countries. The European journal of general practice. 2006;12(3):108–1133. doi: 10.1080/13814780600881268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodríguez A., Delgado-Cohen H., Reviriego J., Serrano-Ríos M. Risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients according to World Health Organization, Third Report National Cholesterol Education Program, and International Diabetes Federation definitions. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targets and therapy. 2011;4(1) doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroncke G., Kosolcharoen P., Clayman J., Peduzzi P., Detre K., Takaro T. Five-year changes in coronary arteries of medical and surgical patients of the veterans administration randomized study of bypass surgery. Circulation. 1988;78, 3 Part 2:I144–I150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craddock N. J., Jones I. R. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helgadottir A., Thorleifsson G., Manolescu A., et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316(5830):1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPherson R., Pertsemlidis A., Kavaslar N., et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316(5830):1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samani N. J., Erdmann J., Hall A. S., et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(5):443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wakil S. M., Ram R., Muiya N. P., et al. A genome-wide association study reveals susceptibility loci for myocardial infarction/coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabs. Atherosclerosis. 2016;245:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen G.-Q., Li L., Rao S., et al. Four SNPs on chromosome 9p21 in a South Korean population implicate a genetic locus that confers high cross-race risk for development of coronary artery disease. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28(2):360–365. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.157248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan K., Patel R. S., Newcombe P., et al. Association between the chromosome 9p21 locus and angiographic coronary artery disease burden: a collaborative meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(9):957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takagi S., Iwai N., Miyazaki S., Nonogi H., Goto Y. Relationship between ABCA1 genetic variation and HDL cholesterol level in subjects with ischemic heart diseases in Japanese. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2002;88(8):369–370. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1613218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Y-y L., Zhang H., X-y Q., Lu X.-z., Yang B., M-l C. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism and coronary artery disease in Chinese population: a meta-analysis of 5,388 participants. Molecular biology reports. 2012;39(12):11031–110319. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cenarro A., Artieda M., Castillo S., et al. A common variant in the ABCA1 gene is associated with a lower risk for premature coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Journal of medical genetics. 2003;40(3):163–168. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma X.-y., J-p L., Z-y S. Associations of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R219K polymorphism with HDL-C level and coronary artery disease risk: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215(2):428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brousseau M. E., Bodzioch M., Schaefer E. J., et al. Common variants in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 in men with low HDL cholesterol levels and coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154(3):607–611. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00722-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abd El-Aziz T. A., Mohamed R. H., Hagrass H. A. Increased risk of premature coronary artery disease in Egyptians with ABCA1 (R219K), CETP (TaqIB), and LCAT (4886C/T) genes polymorphism. Journal of clinical lipidology. 2014;8(4):381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.ZHOU J. I. A. N. Q. I. N. G., XU L. I. M. I. N., HUANG R. O. N. G. S. T. E. P. H. A. N. I. E., et al. Apolipoprotein A5 gene variants and the risk of coronary heart disease: a case-control study and meta-analysis. Molecular medicine reports. 2013;8(4):1175–1182. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan S., Ma Y., Xie X., et al. Association between apolipoprotein A5 gene polymorphism and coronary heart disease in the Han population from Xinjiang. Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2011;32(1):51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kao J.-T., Wen H.-C., Chien K.-L., Hsu H.-C., Lin S.-W. A novel genetic variant in the apolipoprotein A5 gene is associated with hypertriglyceridemia. Human molecular genetics. 2003;12(19):2533–2539. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang Y., Sun P., Guo D., et al. A genetic variant c. 553G> T in the apolipoprotein A5 gene is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease and altered triglyceride levels in a Chinese population. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185(2):433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie L., Li Y.-M. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) polymorphism and the risk of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2017;14(1):p. 84. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables describing genotype distribution among CAD patients and controls, genotype distribution among CAD patients according to the severity of angiographic stenosis, and association between SNP rs2383206 genotypes and CAD severity are included.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.