Abstract

Introduction:

The importance of vaccine thermostability has been robustly discussed in the literature. Nevertheless, the challenge of developing thermostable vaccine adjuvants has sometimes not received appropriate emphasis. Adjuvants comprise an expansive range of particulate and molecular compositions, requiring innovative thermostable formulation and process development approaches.

Areas covered:

Reports on efforts to develop thermostable adjuvant-containing vaccines have increased in recent years, and substantial progress has been made in enhancing stability of the major classes of adjuvants. This narrative review summarizes the current status of thermostable vaccine adjuvant development and looks forward to the next potential developments in the field.

Expert opinion:

As adjuvant-containing vaccines become more widely used, the unique challenges associated with developing thermostable adjuvant formulations merit increased attention. In particular, more focused efforts are needed to translate promising proof-of-concept technologies and formulations into clinical products.

Keywords: Thermostable, vaccine adjuvant, lyophilization, spray drying, aluminum salts, emulsions, liposomes, nanoparticles

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has emerged a robust discussion regarding the value and impact of making vaccines more thermostable. While thermostable vaccines are not a panacea and there are many competing factors to consider, there appears to be general consensus that efforts to improve thermostability are relevant in the development of new vaccine candidates [1–4]. Despite the prominence of the vaccine thermostability conversation, the ensuing importance of adjuvant formulation stability has been implied but only rarely discussed at any depth [5]. Since many synthetic or inactivated vaccines require adjuvants, we believe a summary is needed regarding the challenges and progress achieved in developing thermostable adjuvants. We emphasize that thermostable formulation development and characterization efforts should be undertaken early in the development process for maximum likelihood of success.

To define the scope of the present review, it is important to note that not all vaccines require extrinsic adjuvants. Indeed, although thermostability is an important consideration for highly labile live-attenuated and viral vector vaccines, we do not discuss such compositions here since they already contain intrinsic immunostimulators and are considered to be sufficiently immunogenic without the addition of adjuvants [6]. Extrinsic adjuvants are most suitable for inactivated, subunit, or recombinant protein vaccines for various purposes such as antigen dose sparing; modulation of immune response magnitude, quality, breadth, and/or durability; and enhancement of immune responses in specific age groups (e.g. the elderly or young children) or otherwise immunocompromised populations. In many cases, the vaccine antigen(s) may be the most labile component of an adjuvanted vaccine; nevertheless, the adjuvant should not be neglected when considering thermostable formulation and process development approaches.

The term ‘adjuvant’ is imprecise since there are many types of molecules or formulations that are often referred to collectively as ‘adjuvants’ [7]. Thus, adjuvant may refer to specific molecular structures with immunostimulatory properties such as the synthetic oligonucleotide TLR9 agonist CpG 1018 in the recently approved Hepatitis B vaccine Heplisav® [8]. In other cases, adjuvant refers to particulate formulations such as aluminum salts or oil-in-water emulsions, which are easily the most widely employed adjuvants in human vaccines to date [9,10]. Particulate delivery systems without additionally incorporated molecular adjuvants may have immunomodulatory effect as a result of more effective antigen delivery and presentation to the immune system as well as their size similarity to pathogens that evoke immune recognition [7,11]. Finally, adjuvants may consist of combinations of specific immunostimulatory molecules formulated in particulate vehicles. A prime example of this latter type of adjuvant is GSK’s AS01 formulation, consisting of a TLR4 agonist and saponin formulated in a nanoliposome, included in the varicella zoster vaccine Shingrix® [12]. Different classes of adjuvants may require different thermostability development approaches.

Finally, it is important to identify what exactly constitutes sufficient thermostability in order for an adjuvanted vaccine to be useful in the field. On this point, it must first be stated that loss of potency due to accidental freezing of adjuvanted vaccines (especially aluminum-containing vaccines) may in many cases be more of an issue than elevated temperature excursions, so freeze-thaw stability is an important benchmark for achieving a comprehensive thermostability profile [15,16]. Stability of >12 months at 40°C, obviating the need for any cold chain, would be an impressive achievement but lower benchmarks may be more realistic and still yield meaningful results. For instance, stability at 40°C for 2 months has been identified as a critical benchmark that would facilitate significant cost and distribution benefits [1]. Nevertheless, stability at elevated temperature for just a few days has substantial beneficial impact on ease and cost of vaccine distribution, as in the case of MenAfriVac®, which is stable at 40°C for up to 4 days [17,18]. Indeed, the WHO controlled temperature chain (CTC) program has identified stability for at least 3 days of storage at ambient temperatures not exceeding 40°C as a minimum benchmark [19], and vaccine vial monitors are an effective tool for easily determining whether a specific vaccine has reached its stability endpoint [20,21]. Wider adoption of such tools is anticipated to enable more effective delivery of vaccines with different levels of thermostability. The two authorized COVID-19 mRNA vaccines offer another illustrative example of the impact of relative stability differences on vaccine distribution: one of the vaccines can be stored at −20°C for up to 6 months but is stable at ambient temperature for up to 12 h or at 2–8°C for up to 30 days, whereas the other vaccine is currently approved for storage between −80 and −60°C for up to 6 months and is stable for up to 5 days at 2–8°C, though additional stability data have been submitted very recently to the U.S. FDA for approval of storage between −25 and −15°C for 2 weeks [22–25]. Neither of these products would be considered a thermostable vaccine by conventional standards; nevertheless, the former is anticipated to be substantially easier to store and distribute. Thus, thermostability is a relative term and even limited improvements may be valuable.

In the ensuing sections, we first summarize available tools and techniques that facilitate development of thermostable adjuvant formulations. We then highlight the progress reported in the literature regarding approaches to enhance thermostability of aluminum salts, oil-in-water emulsions, liposomes, other nano/microparticle adjuvants, and adjuvant formulations designed for mucosal or dermal administration. Moreover, we have summarized the available literature references on these thermostable adjuvant formulation platforms in Table 1. Finally, we present our anticipation for the next five years in this exciting field.

Table 1.

Summary of Adjuvanted Vaccine Formulations with Demonstrated or Potential Thermostability

| Molecular adjuvant(s) | Formulation | Approach | Excipient(s) | Antigen(s)/Application(s) | Stability assessments | Stability level | Development stage | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Salts | ||||||||

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Liquid (Microenvironment pH control, additional buffer species, freezing point depression) | Histidine, phosphate, propylene glycol | Recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) | In vitro and in vivo demonstration of potency after 3 freeze-thaw cycles at -20°C or storage for 12 months at 37°C | *** | Preclinical | [43,45,46] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide, aluminum phosphate | Liquid (Freezing point depression) | Propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol 300, or glycerol | Diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis (DTaP or DTwP) | In vivo potency and physical properties maintained after 3 freeze-thaw cycles at -20°C followed by storage for 1–3 months at 22–25°C | * | Preclinical | [43,47] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Liquid (stored in separate vials) | Phosphate buffered saline | HBsAg | In vivo immunogenicity maintained for at least 14 days stored at up to 45°C | * | Preclinical | [52] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Liquid (Buffer optimization) | Phosphate buffered saline | Trivalent recombinant rotavirus antigen P2-VP8 | Physicochemical stability demonstrated for 4 weeks at 37°C | * | Clinical | [53,54] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Liquid | Hepatitis E vaccine Hecolin® | In vitro antigenicity and in vivo immunogenicity maintained for 14 days at 42°C | * | Licensed | [51] | ||

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized antigen and liquid aluminum adjuvant in separate vials | Meningitis A vaccine MenAfriVac® | CTC approved for up to 4 days at 40°C | * | Licensed | [19] | ||

| Aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate | Liquid | HPV vaccine Gardasil® | CTC approved for up to 3 days at 42°C | * | Licensed | [19] | ||

| Aluminum phosphate | Liquid | Pneumococcal vaccine Prevnar®-13 | Previously CTC approved for up to 3 days at 40°C | * | Licensed | [19] | ||

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Liquid (nanoparticles) | Polyacrylic acid | Recombinant tuberculosis ID93 antigen, recombinant influenza H5 antigen | Physically stable to 3 freeze-thaw cycles and 90 days at 37°C | ** | Preclinical | [48] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized (nanoparticles) | Dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine | Ovalbumin model antigen (OVA) | Antigen integrity maintained for 4 days at 40°C | * | Preclinical | [49] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized | Trehalose | Recombinant ricin antigen (RiVax) | Conformational epitope maintenance and in vivo immunogenicity for 12 months at 40°C | *** | Clinical | [55–57] | |

| GLA | Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized | Trehalose | Recombinant human papilloma virus (HPV) L1 capsomere antigen | Retention of antigen structure and immunogenicity for 12 weeks at 50°C | ** | Preclinical | [58] |

| GLA | Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized | Trehalose | Recombinant anthrax dominant negative inhibitor antigen | Physicochemical stability and in vivo immunogenicity maintained for 16 weeks at 40°C | ** | Preclinical | [59] |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized | Trehalose | Recombinant Ebola glycoprotein | Physicochemical stability and in vivo immunogenicity maintained for 12 weeks at 40°C | ** | Preclinical | [60] | |

| CpG 7909 | Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Lyophilized | Undisclosed excipients | Filtered B. anthracis culture supernatant | Physically stable to freeze-thaw | * | Clinical | [61,62] |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide, aluminum phosphate | Spray dried | Trehalose, mannitol, sodium hydrogen phosphate | HBsAg or meningitis A protein-polysaccharide conjugate antigen | Physicochemical and in vivo immunogenicity maintained for 15 months at 37°C for the hepatitis B vaccine; chemical stability maintained for 20 weeks at 40°C for the meningitis A vaccine | *** | Preclinical | [64] | |

| Various aluminum salts | Thin-film freeze dried | Trehalose | Various antigens | Physically stable to freeze-thaw (various antigens), in vivo immunogenicity maintained after 3 months at 40°C (only ovalbumin tested) | ** | Preclinical | [42,63] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide, aluminum phosphate | Spray freeze dried | Trehalose, mannitol, dextran | HBsAg, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids | For the HBsAg formulation, physical aluminum particle stability maintained for 6 months at 40°C, in vitro antigenicity (in absence of aluminum) maintained for 2 months at 40°C and 6 months at 25°C | ** | Preclinical | [44] [151] | |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide | Carbon dioxide assisted nebulization with bubble drying | Trehalose | HBsAg | In vitro antigenicity maintained for up to 10 days at 66°C and up to 43 days at -20°C | * | Preclinical | [65] | |

| Aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate | Drying by nitrogen stream on microneedle patch | Methylcellulose | HPV virus-like particle (VLP) antigen | Thermostability not evaluated | Preclinical | [66] | ||

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide, aluminum oxide | Atomic layer deposition and spray dried particles | Trehalose, hydroxyethyl starch | HPV capsomere | In vivo immunogenicity maintained following storage for 1 month at 50°C | * | Preclinical | [67] | |

| Calcium phosphate | Biomineralization | Synthetic peptide | Live attenuated enterovirus type 71, Foot-and-mouth disease VLP | In vitro and in vivo antigenicity and/or efficacy maintained following storage for 5–7 days at 37°C | * | Preclinical | [68,69] | |

| Emulsions | ||||||||

| Cationic soybean oil-in-water emulsion | Liquid | Cetyl pyridinium choride, polysorbate 80, ethanol | HBsAg | Physical stability and in vivo immunogenicity maintained for 6 weeks at 40°C or 6 months at 25°C | * | Clinical | [70–73] | |

| MPL | Squalene oil-in-water emulsion | Lyophilized | Polysorbate 80, lecithin | B. anthracis protective antigen | Thermostability not evaluated | Preclinical | [75] | |

| GLA | Squalene oil-in-water emulsion | Lyophilized | Trehalose, dimyristyl phosphatidylcholine, poloxamer 188, Tris buffer | Recombinant tuberculosis antigen ID93 | Maintained physiochemical stability, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy after storage for 3 months at 37°C; physicochemically stable to freeze-thaw | ** | Clinical | [26,76–79] |

| MPL, GLA | Squalene oil-in-water emulsion | Lyophilized | Sucrose, polysorbate 80, histidine buffer | Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus antigen (RSV-sF), recombinant Epstein-Barr vius antigen (EBV gP-350) | Thermostability not evaluated | Preclinical | [74] | |

| GLA | Squalene oil-in-water emulsion | Spray dried | Trehalose, dimyristyl phosphatidylcholine, poloxamer 188, Tris buffer, Trileucine (for inhalable formulation) | Recombinant tuberculosis antigen ID93 | Physicochemically stable for 1 month at 40°C | * | Preclinical | [27,29] |

| Liposomes | ||||||||

| Archaean lipids | Archaesome | Liquid | None | Cancer, Chagas, topical | Preclinical | [80–87] | ||

| Sulphated lactosyl archaeol glycolipids | Archaesome admixed with antigen | Liquid | None | OVA | Adjuvant formulation maintained physicochemical characteristics and adjuvant activity after 6 months at 37°C; antigen-adjuvant mixture retained immunogenicity and anti-tumor immunity in mice after 1 month at 37°C | ** | Preclinical | [83] |

| DDA/TPGS Liposome | Lyophilized | Trehalose | OVA | Maintained physicochemical characteristics and antigen adsorption and integrity after 12 weeks at 20°C | * | Preclinical | [92] | |

| MPL | Liposome | Lyophilized | Sucrose and trehalose | Malaria antigen Pfs25 | Maintained physicochemical characteristics and functional antibodies in mice after at least 6 weeks at 60°C | ** | Preclinical | [93] |

| MPL | Lipid cochleate | Lyophilized | Sucrose and PEG2000 | Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | Maintained physicochemical characteristics, antigen entrapment and integrity, and immunogenicity in orally immunized mice after 2 weeks at room temperature | * | Preclinical | [95] |

| MPL | Liposome with mannose derivative | Lyophilized | Sucrose | BSA | Preclinical | [96] | ||

| Gram-negative bacterial envelope component | Bacterial ghost (BG) | Lyophilized | None | Endogenous antigens and incorporated foreign protein and DNA antigens, assessed by various mucosal routes | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [97–100,130] |

| MPL, QS-21 | AS01 liposome | Lyophilized | Sucrose, polysorbate 80 and potassium phosphate (pH 6.1) | Malaria antigen RTS,S (Mosquirix®) | Maintained integrity of the individual antigen and adjuvant components, physicochemical characteristics of the liposome, and immunogenicity in mice after 1 year at 30°C, up to 6 months at 37°C, or 1 month at 45°C after 1 year at 30°C | ** | Preclinical (non-thermostable version is licensed) | [102] |

| CAF01 liposome | Spray dried | Trehalose | Recombinant tuberculosis antigen H56 | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [104] | |

| Nano/microparticles | ||||||||

| Can recombinantly express protein/peptide-based adjuvants within the system | Thioredoxin nanoparticle | Liquid | None | HPV minor capsid protein L2 | Maintained structural stability for 24 h at 100°C and immunogenicity in mice following lyophilization and multiple freeze-thaw cycles | ** | Preclinical | [107] |

| Multiepitope heptameric nanoparticle | Liquid | None | HPV minor capsid protein L2 | Maintained structural stability for 10 min at 80°C | * | Preclinical | [108] | |

| Protein nanoparticle scaffold engineered for multimeric antigen display | Liquid | None | Recombinant RSV antigen | Maintained antigenicity after 1 h at 20°C or 50°C | * | Preclinical | [165] | |

| Nano/microparticles based on antigen conjugation to first 110 amino acids of polyhedrin | Liquid or vacuum centrifuged | None | Green fluorescent protein (GFP) | Maintained antigen-specific IgG titers in mice after storage for up to one year as a dry powder at room temperature or in solution at -20°C or − 70°C | ** | Preclinical | [110] | |

| α-tocopherol | Nanocapsule with α-tocopherol core surrounded by inner layer of chitosan and outer layer of dextran sulphate | Lyophilized | Sucrose | Outer membrane iron receptor IutA protein antigen from E. coli | Maintained particle size and antigen association after at least 12 weeks at room temperature | * | Preclinical | [111] |

| α-tocopherol | Nanoparticle with α-tocopherol core and protamine shell | Lyophilized | Trehalose | Recombinant HBsAg | Maintained particle size, surface charge, antigen integrity and antigenicity after up to one year at 25°C | * | Preclinical | [112] |

| Nanoparticle composed of lecithin, glyceryl monostearate and Tween 20 | Lyophilized | Mannitol and polyvinylpyrrolidone | BSA | Retained immunogenicity in mice after 2.5 months at room temperature, 37°C or -80°C | ** | Preclinical | [113] | |

| Porous silica vesicle with surface-adsorbed antigen | Lyophilized | Trehalose and glycine | Bovine viral diarrhoea antigen | Antibody and cell-mediated responses in mice confirmed post-lyophilization, with dry product stored in vacuum desiccator at 25°C throughout the study, though long-term thermostability not assessed experimentally | * | Preclinical | [115,116] | |

| MPL, R848, cholera toxin (CT), CpG and aluminum hydroxide | Cross-linked albumin nanoparticle | Spray dried into microparticles | Chitosan | Pneumococcal and meningococcal capsular polysaccharide antigens | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [117–119] |

| Viral capsid protein | VLP | Spray dried | Mannitol, trehalose, dextran and L-leucine | HPV VLP | Maintained antigen-specific antibody response in intramuscularly or orally immunized mice after 14 months at 37°C | ** | Preclinical | [121] |

| Mucosal Formulations | ||||||||

| Variant specific surface proteins (VSPs) from protozoa | VLP decorated with VSPs | Liquid | None | Influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) | Maintained in vitro activation of APCs after ten cycles of freezing and thawing, or one month at -70°C, 4°C, or room temperature | * | Preclinical | [124] |

| Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) | Inactivated whole-cell V. cholerae strains | Liquid in phosphate buffered saline | None | Cholera vaccine Dukoral® | Recommended storage at 2–8°C for 3 years, can withstand one-time exposure to temperatures up to 25°C for 14 days | * | Licensed | [37,125] |

| Double mutant E. coli heat-labile toxin (dmLT) | Formalin-inactivated H. pylori whole cell | Lyophilized | Trehalose, mannitol, and citrate buffer (pH 6.8) | H. pylori infection | Maintained immunogenicity in mice immunized orally after at least one month at 37°C | * | Preclinical | [131] [132] |

| 3M-052 | Synthetic virosome | Lyophilized | Sublingual tablet: mannitol, fish

gelatine and trehalose Nasal: trehalose and sodium alginate (mucoadhesive) Oral: trehalose |

HIV-1 gp41-derived antigen | Maintained immunogenicity in rats

immunized subcutaneously after up to 3 months at 40°C, maintained

virosome integrity after one-week exposure to <-15°C |

** | Preclinical | [133] |

| MPL and chitosan | VLP | Lyophilized | Chitosan (mucoadhesive and adjuvant), sucrose and mannitol | Norwalk VLP | Thermostability not assessed | * | Clinical | [136,166] |

| Lipokel® | Direct conjugation | Spray dried | Mannitol | TB antigens Culp1–6 and MPT83 | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [137] |

| Mast cell activator compound 48/80 | Admixture | Spray freeze dried | Trehalose | Recombinant anthrax protective antigen (rPA) | Retained immunogenicity in rabbits immunized intranasally with a unit dose powder device after over 2 years at room temperature | ** | Preclinical | [138] |

| α-galactosylceramide | Single Multiple Pill® (emulsion of antigen and adjuvant dispersed in a gelatin matrix, covered by an enteric polymer coating) | Oral capsule | N/A | E. coli colonization factor antigen I | Maintained internal structure and antigenicity for 12 months and adjuvant activity for 5 months at 25°C/60% relative humidity (RH) and 30°C/ 65% RH | ** | Preclinical | [139] |

| Dermal Formulations | ||||||||

| VLP adsorbed to aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate | Dry coating on microneedle array Nanopatch™ | Methylcellulose | Gardasil® | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [66] | |

| QS-21 and 3D-(6-acyl) PHAD | Synthetic virosome containing antigen and separate liposome adjuvant | Dry coating on microneedle array VaxiPatch™ | Trehalose | Recombinant influenza HA | Accelerated stability test performed on antigen (retains antigenicity for 2 months at 40°C and 60°C) though not adjuvant | * | Preclinical | [142] |

| dmLT | Admixture of antigen and adjuvant (Fluzone® was coated without additional adjuvant)Fadhes | Dry coating on dissolvable silk fibroin microneedle array | Silk fibroin | Fluzone®, C. difficile chimeric toxin A/toxin B, Shigella IpaDB protein | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [143] |

| QS-21 | Antigen and adjuvant molded into dissolvable microneedle array patch made of hydroxyethyl starch and chondroitin sulphate | Thermosetting process | Sucrose | HBsAg | Maintained antigenicity after 6 months at

37°C and 45°C and with 10% loss at

50°C. Adjuvant stability was not monitored. |

** | Preclinical | [144] |

| CpG, aluminum phosphate, CT, CTB, reduced or non-toxic LT | Antigen, adjuvant and excipient mixtures | Air drying in nitrogen purged desiccator | Trehalose | HBsAg, diphtheria toxin and inactivated influenza virus strains | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [145–149] |

| Aluminum oxyhydroxide, aluminum phosphate | Spray freeze dried | Trehalose, mannitol, dextran | HBsAg, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids | For the HBsAg formulation, physical aluminum particle stability maintained for 6 months at 40°C, in vitro antigenicity (in absence of aluminum) maintained for 2 months at 40°C and 6 months at 25°C | *** | Preclinical | [44] [151] | |

| CpG-ODN and CT | Oily paste in Lipid C | N/A | N/A | H. pylori sonicate | Thermostability not assessed | * | Preclinical | [152] |

Notes: Table includes only studies reviewed in this article in the six main formulation categories listed. Except where noted, the antigen and adjuvant components were formulated or dried together in the same container. Thermostability levels are rated as limited (*), promising (**) or very promising (***) consistent with the thermostability categories shown in Figure 1 and depending on the comprehensiveness of the characterization data reported.

2. Approaches for Developing Thermostable Adjuvants

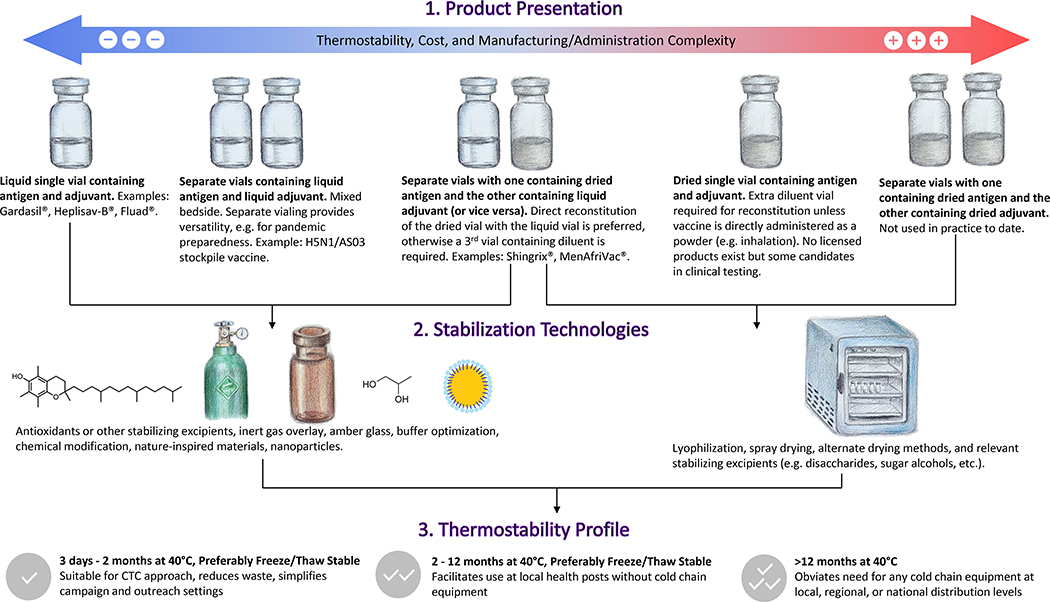

The desired target product profile will help dictate appropriate thermostability development approaches. In some products, adjuvants are separately vialed from the vaccine antigen, and mixed ‘bedside’ prior to administration (e.g. Shingrix®). Indeed, for some indications, separately vialed adjuvant is highly desirable because it offers stockpiling flexibility if the desired antigen is unknown beforehand, such as in the case of pandemic influenza. In other cases, adjuvants are formulated in the same vial as the vaccine antigen (e.g. the seasonal influenza vaccine Fluad®). Thus, thermostabilization approaches may need to take both antigen and adjuvant stability into account. The theoretical product profile options with their advantages and disadvantages are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Thermostable Adjuvanted Vaccine Product Development Flow Chart. Thermostable product design should be considered early in development to maximize efficiency and chance for success. Vials are represented in the figure but other containers or delivery devices may be employed (e.g. pre-filled syringe, nasal powder delivery device, microneedle patch). The thermostability profile categories are adapted from references 1 and 19. Artwork by Yizhi Qi.

All FDA-licensed vaccines are currently administered as liquids, either parenterally or intranasally. Accordingly, some adjuvant thermostabilization approaches are designed to enhance liquid formulation stability. In other cases, vaccine adjuvant thermostability is best enhanced using drying technologies to remove water content, followed by reconstitution prior to administration as a liquid. Intriguingly, progress in the development of adjuvant-containing vaccines that can be administered directly as dry powders via intranasal, pulmonary or intradermal routes may result in thermostable vaccines that do not require reconstitution [13,14]. Selection of an appropriate drying technology and formulation should take into account the target product profile and different drying processes involved (Figure 1), which may necessitate different excipients to maintain product stability under the relevant conditions. Drying a complex vaccine formulation with appropriate excipients can involve a substantial number of both process and product parameters that need to be optimized for the best outcome. Optimization via a “one variable at a time” approach is resource and time consuming. Therefore, Design of Experiments (DoE), a systematic and statistical approach that enables one to optimize key system or process parameters with fewer experiments, has been increasingly utilized [28]. In any case, effective drying process development requires characterization of fundamental formulation and molecular properties such as collapse temperature, glass transition temperature, and diffusion coefficients to inform critical process parameters. Such information can be employed to guide experimental design and accelerate achievement of target objectives [29].

Lyophilization, also known as freeze drying, is the most established drying technology for pharmaceutical formulations including vaccines. Lyophilization requires freezing of the vialed liquid formulation followed by primary drying under reduced pressure to remove unbound water and secondary drying at increased temperature to remove bound water [26]. Several licensed vaccines are available in lyophilized form, designed for reconstitution in liquid form prior to administration [30]. However, it is interesting to note that in the case of adjuvant-containing vaccines, there are no licensed products with lyophilized adjuvant. Instead, the liquid adjuvant is mixed with liquid antigen (e.g. Pandemrix®) or used to directly reconstitute lyophilized antigen (e.g. Shingrix®, MenAfriVac®) [30]. Nevertheless, lyophilization remains an attractive approach for developing thermostable adjuvants since large lyophilization capacity is already established at pharmaceutical manufacturers and the lyophilization development process is well understood. In typical practice, vials are filled with sterile liquid vaccine prior to lyophilization. The lyophilization process is then conducted under aseptic conditions, resulting in a dried cake being formed in each vial. Potential challenges associated with lyophilization include non-uniform exposure of vials to process temperature stresses depending on shelf location, vial fill volume effects, and long processing times. Variations to typical lyophilization include foam drying and thin-film freeze-drying, which have been employed in preclinical studies [31,32].

Another drying technology employed for pharmaceutical formulations is spray drying. Spray drying does not require freezing, is conducted with bulk formulation rather than filled vials, and may be more easily scaled [27]. However, spray drying requires greater exposure to heat and shear stresses during the atomization and evaporation process compared to lyophilization. Multiple small molecule drug commercial products are manufactured via spray drying, and the first asepctically spray-dried biologic, Raplixa®, was approved in 2015 [33,34]. Moreover, various preclinical development efforts regarding spray-dried vaccines have been described [33]. Though not as well established as lyophilization, spray drying offers alternative product characteristics. For instance, liquid solutions can be spray dried and subsequently stored as a bulk powder. Moreover, spray drying is usually designed to produce a flowable powder so that the dried product can be filled into vials. As with lyophilized products, spray dried products can be reconstituted for administration as a liquid. In contrast to lyophilized products, spray dried products can be directly administered as an aerosolized powder. Variations on spray drying technology have been described, including spray freeze drying and carbon dioxide-assisted nebulization with bubble drying [35–37]. While multiple other drying technologies besides lyophilization and spray drying are available, they have not yet been widely employed for vaccine or adjuvant applications [31].

While drying technologies are of high interest for development of thermostable adjuvants, there is also strong motivation for augmenting liquid formulation stability to avoid the need for reconstitution or the added development costs associated with dried products. Liquid formulation stability can be increased through judicious excipient selection. For instance, excipient additives including saline and glycerol can lower solution freezing temperature, and glass-forming excipients such as disaccharides can in some cases protect formulations from damage at sub-freezing temperatures. Overlaying vial headspace with inert gas, inclusion of antioxidants, and protection from light are also commonly practiced approaches to maximize formulation stability.

Regardless of the modalities employed to enhance adjuvant stability, it is important to incorporate appropriate stability monitoring tools to accurately assess the physical and chemical stability of the adjuvant (and antigen). Indeed, appropriately designed stressed stability studies combined with physicochemical characterization can pinpoint degradation mechanisms and thereby indicate which stabilization approaches might have the most impact on adjuvant stability. The vast majority of vaccines are indicated for storage at refrigerated conditions (2–8°C). The WHO’s CTC program specifies stability monitoring at 40°C as a critical benchmark since maintaining stability at this temperature, even for just a few days, can have a major impact on ease of distribution of the vaccine [19]. Ironically, many vaccines (particularly those that contain aluminum salts) are destroyed due to exposure to freezing temperatures rather than elevated temperatures [15,16]. Thus, thermostability evaluation should consider stability to freeze-thaw conditions as well. Advanced software modeling tools can help to extrapolate long-term stability performance based on accelerated data, although such tools must be employed with discretion based on the complex composition of many adjuvant formulations which may preclude using simpler modeling approaches [38]. Moreover, such predictive tools cannot substitute for real time stability studies required by regulatory authorities [39].

3. Aluminum salts

Aluminum salts are approaching 100 years of use in vaccine adjuvant applications. Due to their long history and excellent safety profile, aluminum salts are by far the most commonly employed vaccine adjuvant in clinical products. However, challenges to achieving thermostability with aluminum-containing vaccines include considerations such as maintaining the aluminum salt particulate structure as well as optimal interactions (e.g. adsorption) with vaccine antigens [10].

3.1. Liquid formulations.

It is widely known that freezing of aluminum salts results in particle aggregation, loss of vaccine potency, and increased local reactogenicity although the magnitude of effect varies for different vaccines [40,41]. Indeed, the WHO has developed a simple ‘shake test’ for healthcare workers to determine if aluminum-containing vaccines have undergone freezing and should thus be discarded [41]. Freezing of aluminum salts causes formation of large water crystals that overcome repulsive forces as well as modulation of particle surface chemistry, resulting in substantial particle size growth and increased sedimentation [40,42]. Stabilizing aluminum-containing vaccines to prevent particle aggregation at freezing temperatures has been achieved by inclusion of excipients that depress the freezing point and/or minimize agglomeration, such as glycerol, polyethylene glycol, propylene glycol, polysorbate 80, polyvidone, glycine, and various saccharides and sugar alcohols, as summarized by Clapp et al. [40,43–47]. Interestingly, although differences in vaccine container could theoretically modulate ice-crystal formation, no change in freezing behavior was evident when an aluminum-containing vaccine was packaged in multidose vials compared to single-dose syringes [41]. Another approach to creating freeze-stable aluminum-containing vaccines is through novel nanoparticles, which have been shown to resist particle aggregation after freezing [48,49]. However, it should be noted that aluminum nanoparticles may induce a different quality and magnitude of immune response compared to typical aluminum salts [48,50]. Regarding the stability of aluminum-containing vaccines at elevated temperatures, the stability of the adsorbed vaccine antigen is of most relevance. In this context, it has been shown that the heat stability of antigens adsorbed to aluminum salts can be enhanced by optimizing buffer composition to promote microenvironment pH control [40,45]. Notably, a licensed hepatitis E vaccine containing aluminum oxyhydroxide in pre-filled syringes was shown to maintain antigenicity and immunogenicity after 14 days at 42°C, indicating potential suitability for CTC [51]. Moreover, licensed aluminum-containing vaccines that have been approved for use in the WHO’s CTC program include MenAfriVac® (up to 4 days at 40°C), Gardasil® (up to 3 days at 42°C), and Prevnar® 13 (up to 3 days at 40°C), with additional aluminum-containing vaccines anticipated for CTC approval in the future including for hepatitis B, tetanus, and human papilloma virus vaccines [19]. In this regard, a preclinical hepatitis B vaccine candidate and aluminum oxyhydroxide adjuvant stored in separate vials at up to 45°C maintained immunogenicity in mice after at least 14 days [52]. Finally, a clinical stage subunit trivalent rotavirus vaccine adsorbed to aluminum oxyhydroxide demonstrated 4 weeks physicochemical stability at 37°C [53,54].

3.2. Lyophilized formulations.

Lyophilization of aluminum-containing vaccines can establish stability to freezing and heating excursions. Nevertheless, since lyophilization requires a freezing step prior to drying, additional excipients and control of the freezing rate must be employed to prevent major perturbation of particle size during processing [40]. Using a combination of formulation and process development approaches, multiple successful reports of lyophilized aluminum-containing vaccine candidates have been described. In particular, the Randolph Lab at the University of Colorado with various partners has reported successful development of lyophilized thermostable aluminum-containing vaccine candidates against ricin toxin, anthrax, human papillomavirus, and Ebola [55–60]. In general, the key factors to achieve successful lyophilized aluminum-containing vaccines while minimizing particle aggregation included addition of the excipient trehalose and rapid cooling in the lyophilization freezing process step. The most impressive performance was achieved with the ricin vaccine candidate, which was stable for 1 year at 40°C and demonstrated protective efficacy in mice and non-human primates [55–57]. The lyophilized anthrax, Ebola, and HPV formulations demonstrated stability for at least 3–4 months at 40°C or 50°C [58–60]. While some of the lyophilized formulations also contained the synthetic TLR4 ligand GLA, the stability of GLA was apparently not measured [58,59].

Another lyophilized aluminum-containing anthrax vaccine has also been reported; in this case, the vaccine composition included the TLR9 ligand CpG 7909 [61]. Following reconstitution, the lyophilized vaccine demonstrated nearly identical particle size characteristics as the liquid vaccine, indicating stability to freeze-thaw; nevertheless, stability data at elevated temperature were not shown. Immunogenicity and efficacy profile of the lyophilized composition in guinea pigs was equivalent to the liquid composition. The vaccine has now advanced to clinical evaluation [62].

Using the lesser known thin-film freeze-drying process and trehalose as an excipient, various antigen and aluminum salt combinations were successfully dried while preventing major changes in particle size characteristics [42]. Stability was demonstrated for 3 months at 40°C, as well as after several freeze-thaw cycles [63]. A helpful practical guide to the thin-film freeze-drying method for aluminum-containing vaccines is available [32]. Another potentially promising approach is the combination of aluminum nanoparticle technology with lyophilization [49].

3.3. Spray dried formulations.

While traditional lyophilization approaches proved problematic in many cases with regard to aluminum particle size changes, spray freeze-drying was demonstrated to generate dried aluminum-containing vaccines with minimal impact on particle size, possibly due to a faster cooling rate [40,44]. Spray freeze-dried formulations were physicochemically stable for at least 6 months at elevated temperatures with regards to antigen content and particle characteristics, although immunogenicity following heated storage was not measured [44]. Impressively, a spray dried hepatitis B vaccine containing aluminum oxyhydroxide with trehalose, mannitol, and sodium hydrogen phosphate, demonstrated maintenance of aluminum particle size, antigen conformation, and vaccine immunogenicity for at least 15 months at 37°C, and a spray dried meningitis A protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine containing aluminum phosphate and trehalose also demonstrated promising thermostability [64]. Carbon dioxide assisted nebulization with bubble drying has likewise been employed to generate a dried aluminum-containing viral vaccine candidate that demonstrated stability at elevated and freezing temperatures, and largely maintained potency following reconstitution [40,65].

3.4. Other approaches.

Drying under nitrogen jet of an aluminum-containing vaccine with methylcellulose on a dermal microneedle patch resulted in an immunogenic vaccine, although thermostability was not evaluated in this case [66]. Atomic layer deposition was employed to apply a shell of aluminum oxide onto spray dried particles containing human papillomavirus antigen capsomeres, hydroxyethyl starch, and trehalose, with or without aluminum oxyhydroxide [67]. The alumina-coated microparticles appeared to be stable for at least 1 month at 50°C, and the alumina coating appeared to obviate the need for inclusion of aluminum oxyhydroxide in the interior of the particles. Similarly, live vaccines or virus-like particles coated with another inorganic salt, calcium phosphate, via a synthetic peptide-induced biomineralization process were stable for several days at 37°C, with the metal shell apparently providing an adjuvant effect in addition to thermostability [68,69].

4. Oil-in-water emulsions

Next to aluminum salts, oil-in-water emulsions are the most widely employed vaccine adjuvant class in approved vaccines [9]. In general, oil-in-water adjuvant emulsions consist of sub-200 nm diameter droplets containing metabolizable oils (e.g. squalene), emulsifiers, and other excipients. While storage at 2–8°C is typically recommended for oil-in-water adjuvant emulsions, some efforts exploring alternative stability conditions have been reported.

4.1. Liquid formulations.

Instability mechanisms of oil-in-water emulsions include droplet aggregation and/or coalescence, resulting in increased droplet diameter and eventually visible phase separation. Chemical degradation of oils and emulsifiers is also potentially problematic, and inclusion of antioxidants or inert gas overlay of vials to improve chemical stability is often employed. An intranasal hepatitis B vaccine candidate containing a liquid cationic nanoemulsion maintained antigen stability, emulsion physical stability, and immunogenicity in mice after 6 weeks at 40°C or 6 months at 25°C; however, emulsion chemical stability was not measured [70]. The nasal nanoemulsion platform has moved forward into Phase 1 clinical testing with influenza and anthrax vaccines [71–73].

4.2. Lyophilized formulations.

Transforming oil-in-water emulsions into dried formulations without appropriate stabilizing excipients and lyophilization process development will cause droplet aggregation or coalescence, and changes in droplet diameters have implications for biological activity [74]. A common approach is to employ glass-forming excipients to reduce mobility and/or replace the hydrogen-bonding role of water in maintaining the oil-in-water emulsion droplet structure. Interested readers are referred to a practical resource regarding lyophilization of oil-in-water emulsion adjuvants including insightful tips to optimize performance [26]. Early work on a lyophilized squalene-based emulsion adjuvant was reported using a preclinical anthrax vaccine candidate; however, no thermostability monitoring or emulsion characterization was reported [75]. More recently, a formulation containing squalene oil-in-water emulsion with the TLR4 ligand GLA (GLA-SE) and a recombinant tuberculosis vaccine antigen (ID93) was optimized by a DOE approach, resulting in a lyophilized solid composition that maintained stability for 3 months at 37°C as measured by a suite of physicochemical measurements as well as protective efficacy in the mouse model [26,76–78]. From a large number of excipients screened, trehalose and sucrose (with or without mannitol) were found to be the most effective excipients for lyophilization and stability performance, and a trehalose-based lead candidate formulation was selected for advanced development. Following lyophilization process development, the lyophilized thermostable vaccine was produced under cGMP conditions and is currently being evaluated in a Phase 1 clinical trial to compare its safety and immunogenicity with the liquid-based composition [79]. Another squalene-in-water emulsion with GLA was lyophilized together with recombinant viral protein antigens, and sucrose was more effective than trehalose in reducing droplet size change post-lyophilization; nevertheless, lyophilized emulsion stability was only evaluated for 12 months at 5°C [74].

4.3. Spray-dried formulations.

The same ID93+GLA-SE composition containing trehalose that was successfully lyophilized as mentioned above was also found to be suitable for spray drying, with a comparable thermostability profile as the lyophilized presentation [29]. Moreover, addition of trileucine as a dispersability enhancer yielded a dry powder formulation ID93+GLA-SE with particle characteristics suitable for inhalable delivery [27], although thermostability and biological activity of this presentation have not yet been reported.

5. Liposomes

Liposomes are generally defined as vesicles consisting of an aqueous core encapsulated by a lipid bilayer that can be manipulated to deliver molecular adjuvants (such as TLR ligands or saponins) and/or antigens. The success of the Shingrix® vaccine has secured the place of liposomes as another vaccine adjuvant platform with extensive clinical usage. Other late-stage vaccines such as Mosquirix® and the M72/AS01E tuberculosis candidate indicate that liposome adjuvants could well become even more widely used.

5.1. Liquid formulations.

When it comes to thermostability, nature has something to offer. In contrast to conventional liposomes which may be prone to physical instability and/or chemical degradation in solution, archaeosomes made with one or more ether lipids derived from archaea take advantage of the intrinsic adjuvanticity and stability of these lipids toward a variety of environmental stressors, including high temperatures such as in sterilization by autoclave processes [80,81]. Additionally, archaeosomes have shown higher phagocytic uptake compared to conventional liposomes [82]. Archaeosomes composed of sulphated lactosyl archaeol (SLA) glycolipids maintained their physicochemical characteristics and adjuvant activity following storage at 37 °C for 6 months. SLA archaeosomes admixed with a model antigen and stored at 37 °C for up to 1 month also retained immunogenicity in mice [83]. Archaeosomes have been developed as self-adjuvanting delivery systems for vaccine candidates against cancer [84,85], Chagas disease [86], and as a topical adjuvant [87].

5.2. Lyophilized formulations.

Dehydration of liposomes without stabilizing excipients can cause physical damages including vesicle fusion, leakage, aggregation, and phase separation [88]. A variety of excipients have been utilized to stabilize liposomal formulations during drying processes, including sugars, sugar alcohols, polyols, polymers, amino acids, and polypeptides [89]. Similar to the stabilizing mechanisms discussed for emulsions, these excipients stabilize liposomes through one or both of the following mechanisms: 1) vitrification into an amorphous glass matrix that reduces molecular mobility and serves as a physical barrier between adjacent liposomal bilayers; and 2) replacement of hydrogen bonds formerly supplied by water via direct interaction with the lipid polar head groups [89,90]. Disaccharides are among the most commonly used excipients to protect liposomal vaccine formulations during lyophilization [91–93]. A cationic liposome mixed with a model antigen and lyophilized in the presence of trehalose maintained its physicochemical characteristics as well as antigen adsorption and integrity after storage at 20°C for 12 weeks [92]. Another liposomal system containing a synthetic variant of the TLR4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and the malaria vaccine antigen Pfs25 was lyophilized using sucrose and trehalose as excipients. Lyophilized Pfs25-bound liposomes maintained physicochemical stability and induced functional antibodies in mice following storage at 60°C for at least 6 weeks [93].

A variation of classic lyophilization called procedure of emulsification-lyophilization (PEL) is a technique that involves first preparing an emulsion of vaccine components and excipients, followed by lyophilization to obtain a dry product which, upon rehydration, forms the final structure in solution [94]. PEL has been used to make MPL-incorporated lipid cochleates with sucrose and PEG2000 as excipients, and multifunctional cationic liposomes dually decorated with mannose derivative and MPL and stabilized by sucrose. After storage at room temperature for 2 weeks, both lyophilized formulations remained stable in terms of physicochemical characteristics, antigen entrapment efficiency and integrity, as well as immunogenicity in mice after oral administration [95,96].

Another tool borrowed from nature’s toolbox for the development of thermostable vaccines is bacterial ghosts (BGs). BGs are non-living bacterial envelopes produced by protein E-mediated lysis of Gram-negative bacteria. Because BGs maintain the native cellular morphology and surface antigenic structures of the bacteria, they not only target antigens to antigen-presenting cells (APCs), but also act as natural adjuvants [97]. Importantly, BGs can be lyophilized, and thus have long shelf-life without the need for cold-chain storage [98]. BGs have been used as delivery vehicles for endogenous antigens and incorporated foreign protein and DNA antigens [97,99,100].

While a majority of studies focus on developing new thermostable formulations, some work is also reported on modifying existing formulations to provide thermostability. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) reported the development of a co-lyophilized thermostable form of their RTS,S/AS01 vaccine, which is the world’s first malaria vaccine approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2015 for infants and young children in endemic regions [101]. The vaccine is originally presented as a two-vial liquid-solid formulation, with the lyophilized RTS,S antigen in one vial and the liposomal adjuvant system AS01 containing MPL and QS-21 in solution in another vial. In the study, RTS,S and AS01 were co-lyophilized with sucrose and polysorbate 80 in potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6.1. Stability with regard to integrity of the individual antigen and adjuvant components, physicochemical characteristics of the liposome, and immunogenicity in mice were demonstrated for storage periods including 1 year at 30 °C, up to 6 months at 37 °C, and a heat excursion consisting of 1 month at 45 °C after 1 year storage at 30 °C [102].

5.3. Spray dried formulations.

A clinically tested multistage subunit tuberculosis vaccine antigen H56 was spray dried with the cationic liposome adjuvant “CAF01” and trehalose into a potentially thermostable and inhalable dry powder vaccine. A fast drying rate was found to be essential to avoid phase separation and lipid accumulation at the surface of the liposomes during spray drying [103]. Reconstituted spray-dried formulation showed comparable physicochemical properties and vaccine-induced humoral and cellular immune responses to liquid formulation in mice immunized subcutaneously. However, the study did not investigate thermostability over time [104].

6. Nano/microparticles

Particulate-based formulations that are not easily classified in the major adjuvant platforms listed above are generally described below as nanoparticle or microparticle formulations. Thus, adjuvant systems based on synthetic polymers or biopolymers, solid lipids, silica, etc. are included below. In some cases, the formulations combine classical adjuvant components (e.g. squalene) with novel particulate formulation platforms.

6.1. Liquid formulations.

Particulate formulations stored in solution can suffer from physical instabilities such as aggregation due to their thermodynamically unfavorable state and chemical breakdown of their various components over time, which can be exacerbated by temperature perturbations [105,106]. Several innovative approaches have been reported to impart thermostability to nano/microparticle formulations in solution. A recombinant single-molecule human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine candidate exploiting the highly thermostable thioredoxin from the hyperthermophilic archaeon P. furiosus as an antigen-presenting nanoparticle scaffold was reported to maintain structural stability for 24 h at 100°C as well as immunogenicity in mice following lyophilization and multiple freeze-thaw cycles [107]. A follow-up study upgraded the original monomeric vaccine into a multiepitope heptameric nanoparticle, though it was less stable, maintaining structural stability for 10 min at 80°C. When tested in mice, the multiepitope nanoparticle vaccine elicited neutralizing antibodies against ten different HPV viral types including three not represented in the vaccine [108]. Similarly, an engineered protein nanoparticle scaffold designed for multimeric display facilitated increased thermostability (and immunogenicity) of a recombinant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) antigen compared to the recombinant antigen alone [109]. Although the vaccines in these studies were tested with separately added commercial adjuvants, the platforms do offer the possibility of recombinantly expressing protein/peptide-based adjuvants within the system [107]. A related approach involved fusion of a model antigen to the first 110 amino acids of polyhedrin from Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhederovirus to produce a protein construct that self-aggregates into nano- and microparticles, although in this case no exogenous adjuvants were employed. Nevertheless, the nanoparticle construct appeared to have inherent adjuvant properties since long-lasting antigen-specific IgG titers in mice were maintained following storage as a vacuum centrifuged dry powder at room temperature or in solution stored at −20°C or − 70°C for up to one year [110].

6.2. Lyophilized formulations.

Other studies have developed more thermostable particulate formulations via the more traditional approach of drying with appropriate stabilizing excipients. Turning complex particulate systems into dry forms while preserving the physicochemical characteristics and biological activities of the components can be challenging. Different excipients can have very different interactions with a particular system that are difficult to predict beforehand, therefore an empirical approach is typically taken to select the optimal excipient(s). A nanocapsule composed of a vitamin E core, surrounded by a polymeric bilayer composed of an inner layer of chitosan and an outer layer of dextran sulphate was reported. Nanocapsules containing the outer membrane iron receptor IutA protein antigen from E. coli sandwiched between the two polymeric layers elicited higher antibody titers in mice than those obtained with antigen precipitated with aluminum. Excipients including mannitol, sucrose, trehalose and glucose were screened, with sucrose giving the best result. Lyophilized nanocapsules were stable at room temperature for at least 12 weeks in terms of particle size and antigen association, though no in vivo functional assessment post-lyophilization was performed [111].

Thermostable nanoparticles consisting of an oily core (squalene or α-tocopherol), surrounded by a protamine shell have been described. The positively charged protamine facilitated adsorption of the recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen that carries (has) a negative surface charge. Additional benefits of protamine include cell-penetrating capacity and ability to enhance antigen-specific response when presented in particulate form. The formulation containing an α-tocopherol core lyophilized in the presence of trehalose maintained particle size and surface charge, as well as antigen integrity and antigenicity following storage at 25°C for up to 1 year [112].

Nanoparticles composed of lecithin, glyceryl monostearate and Tween 20, and conjugated with model antigens bovine serum albumin (BSA) and the B. anthracis protective antigen (PA) were lyophilized into dry powders. Among sucrose, dextrose, mannose, mannitol and trehalose screened as excipients, mannitol proved to be the most effective. However, the low glass transition temperature (Tg) of mannitol prompted the addition of polyvinylpyrrolidone as a co-protectant to enable storage above room temperature. Lyophilized nanoparticles maintained particle size and immunogenicity in mice. Antigen-specific IgG titers of lyophilized PA nanoparticles were comparable to PA adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide. Lyophilized BSA nanoparticles stored for 2.5 months at room temperature, 37°C or −80°C maintained anti-BSA IgG titers in mice [113].

Porous silica nanoparticles, a platform that has already been extensively explored for drug delivery applications [114], are gaining increasing interest as vaccine carriers in recent years. The capacity of silica nanoparticles to induce both humoral and cellular immune responses makes them advantageous over traditional adjuvants [115]. Porous silica vesicles surface-adsorbed with a bovine viral diarrhoea antigen were co-lyophilized with trehalose and glycine. The dry product was stored in a vacuum desiccator at 25°C over the course of the study, though long-term thermostability was not assessed experimentally. Lyophilized vesicles induced balanced antibody and cell-mediated memory responses that lasted for at least 6 months in mice [116].

6.3. Spray dried formulations.

Biodegradable cross-linked animal-derived albumin nanoparticles spray dried into microparticles have been developed to enable slow release of encapsulated antigens with or without additional adjuvant, thereby creating a depot effect. Spray drying was facilitated by chitosan as an excipient in one study [117]. The approach has been used to encapsulate several antigens and adjuvants including MPL, R848, cholera toxin, CpG and aluminum hydroxide for preclinical studies, though thermostability of the formulations was not assessed [117–119]. A bacteriophage virus-like particle (VLP)-based HPV vaccine candidate, consisting of multivalent epitope presentation on a self-assembled viral capsid protein with endogenous adjuvant activity [120], was spray dried with a multi-component excipient system containing mannitol, trehalose, dextran and L-leucine and optimized spray drying parameters identified by a half-factorial DoE approach. Intramuscular immunization of mice with a single dose of reconstituted dry powder VLPs that were stored at 37°C for 14 months elicited high antigen specific IgG titers, though oral delivery of dry powder VLPs encapsulated in enteric-coated capsules elicited a weaker response [121].

7. Mucosal formulations

Protection against many pathogens that enter through mucosal surfaces may require induction of mucosal immune responses, which is most effectively achieved by mucosal immunization [122]. Moreover, in contrast to the invasive nature of the more traditional parenteral routes of vaccination, which reduces patient compliance, vaccination via mucosal routes enables painless administration. There is thus a strong interest in development efforts regarding mucosal vaccine formulations. Nevertheless, mucosal delivery is challenging due to biological barriers to delivery, unique stability and device compatibility requirements, and additional safety considerations [123].

7.1. Liquid formulations.

Variant specific surface proteins (VSPs) expressed by intestinal and free-living protozoa not only are resistant to proteolytic degradation and extreme pHs and temperatures, but also act as TLR4 agonists. These unique properties make them a useful tool to protect and adjuvant vaccine antigens for oral immunization. Chimeric VLPs decorated with VSPs and expressing model surface antigens including influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA), were protected from various means of degradation, and activated antigen-presenting cells in vitro after ten cycles of freezing and thawing, or one month storage at −70°C, 4°C, or room temperature. Orally administered VSP-HA-VLPs, but not HA-VLPs, protected mice from influenza infection and HA-expressing tumors [124].

Dukoral®, an oral cholera vaccine licensed in Europe and Canada, consists of inactivated whole-cell V. cholerae strains and purified recombinant cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) as a suspension in phosphate buffered saline [125]. The nontoxigenic CTB component in this vaccine serves as both an antigen and an adjuvant and has been shown as an effective mucosal adjuvant for a variety of vaccine antigens in various formulation formats [126,127]. The vaccine is taken orally with a sodium bicarbonate solution to neutralize the stomach acid that otherwise destroys CTB. The recommended storage condition for Dukoral® is refrigeration at 2–8 °C with a shelf life of 3 years, though the formulation can withstand a one-time exposure to temperatures up to 25 °C for 14 days [128]. Furthermore, licensed inactivated oral cholera vaccines that do not contain CTB include Shanchol®, which has been approved for CTC use for up to 14 days at 40°C, and Euvichol®, which is anticipated to soon have a similar CTC recommendation [19,129].

7.2. Lyophilized formulations.

Lyophilized bacterial ghosts have been assessed by various routes of mucosal immunization in animal models, including pulmonary, oral, intranasal, intravaginal, intraocular and rectal [98]. For example, lyophilized A. pleuropneumoniae BG powder administered as an aerosol to pigs induced complete protection against pleuropneumonia [130]. Oral administration of lyophilized V. cholerae ghosts in rabbits induced humoral and cellular immune responses, including protective immunity against challenge infections [99].

Formalin-inactivated H. pylori whole cell (HWC) adjuvanted with a double mutant E. coli heat-labile toxin adjuvant (dmLT) was lyophilized in trehalose, mannitol, and citrate buffer at pH 6.8. The double mutation was introduced on the LT to reduce its enterotoxicity. Oral vaccination of lyophilized HWC vaccine in mice was as protective as liquid HWC vaccine. The lyophilized vaccine was reported to maintain immunogenicity in mice after storage at 37°C for at least 1 month, though data were not shown [131]. The E. coli heat-labile toxin itself has been rendered more thermostable via the introduction of an additional disulfide bond in its A1 subunit, by means of the double mutation N40C and G166C, which increases the melting temperature of the A subunit by 6°C as measured by differential scanning calorimetry [132].

A recent report by the MACIVIVA European consortium described new GMP manufacturing processes to fabricate thermostable virosome-based human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vaccines in solid forms for mucosal vaccination. Virosomes containing HIV-1 gp41-derived antigens anchored in the phospholipid membrane and the TLR7/8 agonist adjuvant 3M-052 were freeze-dried into sublingual tablets with mannitol, fish gelatine and trehalose. Immunogenicity of the tablets stored at 40°C for up to 3 months was preserved when tested by subcutaneous immunization in rats [133].

One unique challenge of mucosal vaccination is the need to overcome the natural defense mechanisms at mucosal sites, such as the mucus layer that coats all mucosal surfaces, which protect the host from invasion of foreign pathogens, but also work against successful delivery of vaccines [134]. Many mucosal vaccine formulations thus incorporate mucoadhesive agents, typically synthetic and biopolymers such as chitosan and alginate, to facilitate vaccine retention and delivery. In some cases, these materials can also serve as adjuvants and stabilizing excipients [135]. A lyophilized norovirus VLP vaccine, containing MPL as an adjuvant, chitosan as a mucoadhesive agent and adjuvant, and sucrose and mannitol as stabilizing excipients, showed promise in a Phase 1 clinical trial against Norwalk virus infection; although thermostability data was not reported, the potential for storage at room temperature was mentioned [136]. Vaccination using an intranasal delivery device significantly reduced the frequencies of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis and Norwalk virus infection in patients [14].

7.3. Spray dried formulations.

TB antigens Culp1–6 and MPT83, separately conjugated to the TLR2 agonist adjuvant Lipokel®, were spray dried with mannitol and delivered directly to the lungs of mice by intra-tracheal insufflation. Both formulations generated protective responses in the lungs against aerosol M. tuberculosis challenge. The study did not specifically evaluate thermostability of the formulations over time [137].

Anthrax recombinant protective antigen (rPA) adjuvated with a mucosal adjuvant, a mast cell activator compound 48/80, were spray freeze dried with trehalose and delivered intranasally in rabbits with a unit dose powder device. Freshly prepared SFD powder vaccine or powders stored for over 2 years at room temperature both elicited immune responses comparable to that induced by intramuscular injection with rPA [138].

In the same MACIVIVA study described above [133], the HIV-1 gp41 virosomes were also spray-dried with trehalose and sodium alginate (mucoadhesive) for nasal delivery and trehalose for oral delivery. Reconstituted virosomes had similar size and in vitro uptake by antigen-presenting cells compared to virosomes in liquid form. After exposure to 40°C for up to 3 months, immunogenicity of both solid forms were maintained in rats immunized subcutaneously. Virosome integrity was also reported to be preserved during a one-week exposure to <−15°C, mimicking accidental freezing conditions [133].

7.4. Other approaches.

An adjuvanted oral capsule named Single Multiple Pill® (SmPill®) has been developed for oral vaccine delivery. The formulation contains an emulsion core consisting of antigen and adjuvant droplets dispersed in a gelatin matrix, covered by an enteric polymer coating for intestine-specific release. An SmPill® containing E. coli colonization factor antigen I and the orally active adjuvant α-galactosylceramide maintained its internal structure and antigenicity at 25°C/60% relative humidity (RH) and at 30°C/ 65% RH for 12 months, and at 40°C/75% RH for 6 months. The immunostimulatory activity of the adjuvant was preserved after exposure to all three temperature/RH conditions for up to 5 months [139].

8. Dermal formulations

With increasing interest in developing self-administrable vaccines, the area of dermal vaccine delivery has seen rapid growth. The skin makes an attractive alternative site for vaccination due to its dense network of potent APCs and dermal dendritic cells that are not readily accessible to parenteral vaccination [66]. However, there may be unique challenges associated with dermal delivery such as device requirements, local reactogenicity considerations, and volume limitations [140].

8.1. Microneedle arrays.

Microneedle arrays are devices composed of rows of microscopic needles that allow minimally invasive delivery of vaccines or therapeutics across the skin [141]. Dry-coating of vaccine antigens and adjuvants on microneedle arrays with the aid of stabilizing excipients such as methylcellulose, trehalose and silk fibroin have resulted in effective transdermal vaccination in rodents [66],[142,143]. A dissolvable microneedle array patch made of hydroxyethyl starch (HES) and chondroitin sulphate has also been described, where the microneedles dissolve upon dermal penetration to release the incorporated vaccine content. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) formulated with QS-21 and sucrose as an excipient was incorporated within the HES-based microneedles via a thermosetting process. Intradermal vaccination with the patch in swines demonstrated the same level of immunogenicity as the commercially available aluminum-adjuvanted HBsAg vaccine Engerix-B™ administered intramuscularly. Antigenicity was retained after six months of storage at 37°C and 45°C and with only a 10% loss at 50°C, though adjuvant stability was not monitored [144].

8.2. Epidermal powder injection.

Epidermal powder injection (EPI) is another technique that has been explored for intradermal administration of dry powder vaccines. EPI devices accelerate vaccine powders upon actuation by a stream of expanding gas, to deposit vaccine particles to the epidermal layer of the skin, targeting its rich network of APCs. The narrow epidermal target space necessitates an interconnected approach to optimizing injector device parameters and vaccine powder particle characteristics to achieve a precisely targeted delivery [145], posing an even greater challenge to also incorporate thermostability in the formulations. Various combinations of vaccine antigens, adjuvants (aluminum salts, CpG, bacterial toxins and QS-21) and excipients have been developed into dry powders for epidermal powder injection [145–149].

Spray freeze drying is commonly used to produce dry powdered vaccines for EPI as the technique has been shown to produce particles with light and porous characteristics, giving rise to powders with favorable aerodynamic properties and thus superior aerosol performance [44]. Spray freeze drying also has some unique characteristics that make the technique well suited for enhancing vaccine stability. It combines characteristics of spray drying, which involves atomization of a liquid into small droplets of controlled sizes, and freeze-drying, which is particularly suitable for drying thermally sensitive materials. Increased surface area of the droplets enables rapid freezing and sublimation, which mitigate phase separation of vaccine components and particle aggregation [150]. In a study comparing freeze drying, spray drying, air drying, and spray freeze drying for making dry powder of aluminum-adsorbed antigens for EPI, spray freeze drying resulted in minimal aluminum coagulation upon reconstitution and best preserved the in vivo immunogenicity of antigens in animal models in contrast to the other techniques [151]. Additionally, like spray drying, this technique enables separate drying of the antigen and adjuvant components, which can be stored either combined or separately without undesired interactions between the two [37].Hepatitis B antigen adsorbed to aluminum salts were spray freeze dried into powder formulations with an excipient combination of trehalose, mannitol and dextran. When delivered to guinea pigs by EPI or intramuscular injection after reconstitution, the dry powder formulations were as immunogenic as the original liquid vaccines. Powder samples stored at 40°C for up to 6 months showed no obvious changes in particle size or agglomeration. Antigen integrity and antigenicity remained stable at 25°C for up to 6 months or 40°C for up to 2 months [44].

8.3. Other approaches.

Transcutaneous or topical application of an oily paste containing soluble H. pylori sonicate formulated in Lipid C, a blend of fractionated triglycerides, significantly reduced the gastric bacterial burden in mice following gastric challenge with live H. pylori. Protection was further enhanced by inclusion of CpG-ODN and cholera toxin in the formulation. The study did not specifically evaluate thermostability though the authors suggest its potential given the nature of this formulation [152].

9. Alternative platforms

Other creative approaches to achieving thermostable adjuvants have been reported. For instance, an approved TLR7 ligand-containing topical cream (Aldara®) that is stable at room temperature has been topically applied immediately prior to intradermal vaccination with approved viral vaccines, eliciting enhanced seroprotection/seroconversion, durability, and response broadening effects in multiple clinical studies [153–155]. DNA vaccines have also been reported to offer ambient temperature as well as freeze-thaw stability, and genetic adjuvants can be engineered into such vaccines [156]. Ensilication, a method that uses the silica solution-gelation process to encase materials in a resistant silica cage, has been shown to thermally protect vaccine materials including a protein-based adjuvant prior to use [157,158]. However, one drawback of this approach is that the ensilicated content needs to be released using an acidic solution before administration, which can cause a certain degree of degradation to the vaccine components and adds additional processing procedures that likely will require trained personnel and specialized equipment. Silk fibroin protein, which has previously been used to fabricate dissolvable microneedles for delivering adjuvanted vaccine antigens [143], recently found utility in the formulation of thin films to thermally stabilize vaccines. When co-formulated with other excipients and air-dried, silk fibroin films containing the active vaccine material of the licensed inactivated poliovirus vaccine IPOL® maintained 70% in vitro potency of its D-antigen component after storage for nearly three years at room temperature, and greater than 50% potency for two of its three serotypes after one year storage at 45 °C. Films stored at 45 °C for 2 weeks generated equivalent neutralizing antibody responses to IPOL® for two of the three serotypes in rats. The authors hypothesized that the stabilizing effect of dried silk fibroin matrix results from its glassy nature, which suppresses molecular mobility [159]. This technology is likely to also be useful for stabilizing adjuvanted vaccines. Finally, laser-based systems have been shown to induce adjuvant effects alone or in combination with molecular adjuvants, thus providing a physical adjuvant modality without cold chain storage restrictions [160].

10. Conclusion

Attempts to develop thermostable formulations have been reported for most classes of adjuvants, including aluminum salts, oil-in-water emulsions, liposome, polymeric particles, virosomes, virus-like particles, mucosal and dermal formulations, and other novel adjuvant platforms. Besides optimization of liquid formulations, lyophilization and spray drying technologies to generate dried adjuvant formulations have been widely employed in preclinical studies. Nevertheless, significant gaps remain. More effort is needed to advance development of thermostable adjuvant-containing products to clinical and licensure stages. Moreover, the thermostability of some candidates is not always well characterized even when there is apparently good potential for expecting increased stability, such as in the case of dried formulations. Translation of the promising approaches reported here to cGMP manufacturing and clinical testing should enable eventual licensure of next generation adjuvant-containing vaccines that are better-suited for distribution in resource-poor areas.

11. Expert opinion

Although efforts in recent years have shown promise as described here, the development of thermostable adjuvant formulations has historically been neglected as evidenced by the lack of any licensed products. The vast expense and clinical testing complexity involved in re-engineering existing licensed vaccine formulations results in little motivation to dedicate resources to this area. However, no such limitation exists for the development of new vaccine candidates containing adjuvants, especially considering the encouraging results reported here across multiple classes of formulations. While the potential benefits of thermostable adjuvants may have the greatest implications for limited-resource settings, the impact in other settings should not be underestimated. For instance, the frozen storage requirements of the two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (formulated in lipid nanoparticles) that have been approved or received emergency use authorization in several countries has complicated distribution efforts [22–24,161]. Although there is an unfortunate paucity of stability data due to the relative novelty of the mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine platform, it appears that chemical stability issues with the mRNA as well as physical stability issues with the lipid nanoparticle delivery systems have resulted in the extreme storage recommendations [162], and attempts at lyophilization and improved thermostability have apparently not been very promising to date [163,164]. This situation clearly illustrates that preparedness for future pandemics should benefit from thermostable adjuvants and delivery systems, enabling produced vials to be more easily distributed and stored for longer periods of time before needing to be replaced.

Despite the potential benefits of thermostable adjuvants, there may also be less desirable impacts. For instance, dried formulations designed for injection need to be reconstituted prior to delivery. Reconstitution adds complexity at the point of use, and errors in this context have sometimes resulted in serious safety issues. Alternatively, some devices enable simplified reconstitution by containing separate compartments for dried formulation and reconstitution liquid; when ready for use, reconstitution occurs by rupturing the membrane separating the two components. While elegant in principle, such approaches are anticipated to result in higher costs of goods and fill/finish complexity. For simplicity, the ideal format is a thermostable liquid in a single container/device, or a powder that does not require reconstitution (e.g. for intranasal delivery). However, the presence of water can make achieving thermostability challenging, and there are currently no licensed dried vaccines that do not require reconstitution. Nevertheless, the desirability of a single vial liquid formulation means that efforts to establish their thermostability profiles are worthwhile, even if only a few days or weeks of stability outside the cold chain are achieved [51].

In the next five years, we can anticipate that additional thermostable adjuvants will enter clinical testing and that completion of ongoing trials will reveal the safety and immunogenicity profile of existing candidates. Combinations of thermostable adjuvant formulations with alternative routes of delivery, such as coated microneedles or dry powder nasal delivery, are particularly interesting. An important prerequisite to adoption of thermostable formulations in the industry will require more widespread use of drying technologies to make vaccines. While lyophilization is firmly established and used by many manufacturers, other drying technologies have yet to be employed to make any licensed vaccine products. Nevertheless, as spray drying and other techniques gain broader acceptance with vaccine manufacturers it will be much easier to translate the promising early stage work described above.