Abstract

The multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) transporters catalyze active efflux of a broad range of chemically- and structurally-diverse compounds including antimicrobials and chemotherapeutics, thus contributing to multidrug resistance in pathogenic bacteria and cancers. Multiple methodological approaches have been taken to investigate the structural basis of energy transduction and substrate translocation in MATE transporters. Crystal structures representing members from all three MATE subfamilies have been interpreted within the context of an alternating access mechanism that postulates occupation of distinct structural intermediates in a conformational cycle powered by electrochemical ion gradients. Here we review the structural biology of MATE transporters, integrating the crystallographic models with biophysical and computational studies to define the molecular determinants that shape the transport energy landscape. This holistic analysis highlights both shared and disparate structural and functional features within the MATE family, which underpin an emerging theme of mechanistic diversity within the framework of a conserved structural scaffold.

Keywords: MATE, multidrug resistance, alternating access, antiport, NorM, DinF, PfMATE

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Active extrusion of metabolites and xenobiotics from the cell through integral membrane transporters is an essential process to ensure cell survival. Such dedicated transport systems have been harnessed by prokaryotes and eukaryotes as primary mitigators of pharmacotherapies targeting bacterial infections and even cancers [1,2]. As a consequence, these transporters contribute to the clinical phenomenon of multidrug resistance to antibiotics and first line chemotherapeutics [3,4]. Broadly-conserved resistance to specific drugs has been long observed in bacteria [5]. However, a dearth of novel antibiotics combined with steady emergence of microbes displaying acquired drug resistance phenotypes has prompted health organizations to declare multidrug resistance as a global public health concern [6].

An expanding list of transporters that mediate efflux of a wide spectrum of drug substrates, coined multidrug resistance (MDR) transporters, has been compiled from seven families so far [1,7–9]. These families are distinguished by their primary sequence, structural folds and efflux mechanisms: ATP-binding cassette (ABC), small multidrug resistance (SMR), resistance/nodulation/cell division (RND), major facilitator superfamily (MFS), multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) and the recently described proteobacterial antimicrobial compound efflux (PACE) and the AbgT proteins. Whereas ABC transporters utilize ATP hydrolysis to power efflux, the remaining transporter families transduce the potential energy stored in electrochemical ion gradients across the membrane to transport substrates against their concentration gradients. The remarkable diversity of proposed transport mechanisms for these families in combination with overlapping substrate specificity profiles give rise to coordinated networks of MDR transporters that catalyze robust export of cytotoxic molecules [1,10]. Thus, defining structural and functional parameters that underpin MDR transporter activity is central to conquering the problem of multidrug resistance.

Ubiquitously expressed in all kingdoms of life, MATE transporters have been proposed to participate in a myriad of fundamental processes. Plant MATE transporters support iron homeostasis [11], hormone signaling [12], aluminum tolerance in acidic soils and protection of roots from inhibitory compounds [13,14]. In humans, the expression of MATE transporter orthologs hMATE1 and hMATE2 along the brush border membrane of proximal epithelial cells facilitates the terminal step of organic cation/anion excretion from the kidney [15–18]. Although substrate specificities of hMATE1/2 are not identical, they have been shown to transport a variety of chemically-dissimilar drugs including metformin, chloroquine, antimicrobials and chemotherapeutics such as cisplatin and oxaliplatin [19–21]. Expression of MATE transporters in pathogenic bacteria confers resistance to a variety of toxic dyes (ethidium, rhodamine), fluoroquinolones (norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin), aminoglycosides (kanamycin, erythromycin), and even new generation glycylcyline antibiotics [22–25].

Discovered more than 20 years ago, MATE transporters were thought originally to belong to the MFS [25]. However, phylogenetic analysis and subsequent structural characterization indicated that the MFS and MATE family are distinct both in sequence and in topology [26,27]. In fact, MATE transporters are classified into the multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide (MOP) flippase superfamily [28]. Based on primary sequence similarity, the MATE family is further segregated into three main branches (Fig. 1): the NorM, DNA damage-inducible protein F (DinF) and Eukaryotic subfamilies [26]. Crystal structures of representatives from each of these subfamilies revealed a conserved fold of 12 transmembrane helices (TM) arranged as two bundles of six helices with intramolecular two-fold symmetry about an axis perpendicular to the membrane plane [27,29]. Initially, all structures captured transporters adopting outward-facing conformations defined by a central cavity between the two bundles open to the extracellular or periplasmic side of the membrane. Recent crystallographic studies, supported by biophysical analyses, have described other intermediates in the conformational cycle. Similar to other transporter families, these data have been interpreted within the context of an alternating access mechanism (Fig. 2) in which isomerization between distinct conformations is coupled to ligand binding.

Figure 1. MATE phylogenic tree and sequence alignment of subfamily representatives.

(a) Fifty-three sequences derived from the TCDB database [87] were aligned to approximate evolutionary relatedness using the online tool MUSCLE [88]. The phylogram was depicted using the Qiagen CLC Workbench software. Transporters with structural models are highlighted in grey. (b) Sequence alignment of representative MATE transporters, grouped by subfamily, indicating highly conserved residues known to be required for ion and/or substrate binding in the N-lobe (red) and C-lobe (blue). The alignment was performed in Qiagen CLC Workbench using a progressive alignment algorithm.

Figure 2. Schematic of alternating access in MATE transporters.

The antiport mechanism requires coordinated interconversion between at least two structural states separated by an energy barrier(s): outward-facing (OF, i and vi) and inward-facing (IF, iii and iv) conformations that expose ligand binding site(s) to opposite sides of the membrane. Within the context of secondary active transport, transduction of potential energy derived from electrochemical ion gradients powers the conformational cycle. Population of other structural intermediates along the transition pathway, including obligatory doubly occluded conformations (ii and v) in which periplasmic and cytoplasmic gates restrict access to binding site(s), play a role in maintaining thermodynamic coupling of ion gradients to transporter mechanics. The steady-state concentration of bound ligand(s) defines the relative occupancy of specific conformations that exist in equilibrium.

The molecular details of MATE transporter alternating access have been the subject of controversy, precluding a consensus mechanism of substrate efflux. Unique substrate binding motifs, promiscuity of the driving ion and the proposed mechanics of conformational changes underscore an emerging theme of mechanistic diversity, even within the same MATE subfamily. Here, we review and integrate structural, biophysical and computational studies to delineate determinants of alternating access in MATE transporters. Of particular focus are studies that highlight the role of conserved residues in mediating functional dynamics as well as the importance of lipids in shaping the conformational energy landscape.

Alternating access inferred from MATE transporter crystal structures

Conceptualized in terms of a membrane-embedded pump or translocator that mediates passage of cargo, alternating access posits physical barriers, often referred to as “gates”, that undergo explicit conformational changes to govern ligand entry into or egress from a centralized binding site within a substrate permeable cavity [30–32]. If the conformational cycle is thermodynamically-coupled to an energy source, such as that stored in ATP (primary active) or electrochemical potentials (secondary active), transporters will drive substrate flux against its concentration gradient. Schematically depicted in Fig. 2, MATE transporters function as antiporters, or exchangers, that couple substrate export to inwardly-directed Na+ or H+ gradients [33]. The antiport model predicts that the occupation of outward-facing (OF) and inward-facing (IF) conformations is determined by the binding of substrate and ions, respectively. Crystal structures from many transporter families, including the MATE family, along with biophysical studies have supported the basic elements of alternating access by capturing various predicted conformational states and by identifying the relative locations of substrate and ion binding sites [32,34–42]. Although the relationship of the crystal structures to the conformational cycle often requires experimental validation, these structures provide a framework to design and interpret biochemical and biophysical investigations. Clues regarding the molecular details of alternating access have been inferred from the topological arrangement of TM helices. Reviewed extensively elsewhere [32], the “rocker-switch”, “rocking-bundle” and “elevator” mechanisms propose intricate local and global conformational changes to facilitate alternating access in different fold classes of transporters.

General structural features of MATE transporter OF conformations

Twenty-nine crystal structures representing eight transporters from seven organisms have been obtained so far (Table 1 and Fig. 1). These structures have been solved in detergent micelles or in lipid mimetic environments (e.g. monoolein LCP). Remarkably, all but one of these adopt similar OF conformations regardless of bound ion, substrate or inhibitors, which suggest that OF intermediates represent low energy states favored in crystal lattice formation. In general, the OF is defined by a V-shape central cavity cradled by the interface of two pseudo-symmetric six-helix bundles commonly referred to as the N- and C-lobes and oriented toward the extracellular milieu (Fig. 3). In contrast, highly ordered protein structure occludes access to the central cavity from the cytoplasmic side. Simulations of water penetration in the OF conformation of multiple MATE representatives demonstrate hydration of the central cavity all the way into the middle of the lipid bilayer [43–47]. Similar to MFS transporters, the two lobes are connected by a long cytoplasmic loop between TM6 and TM7. Unlike MFS transporters, symmetrical helices TM1 (N-lobe) and TM7 (C-lobe) form packing interactions with other helices in the opposite lobe within the inner membrane leaflet (Fig. 3, lower right).

Table 1:

Library of MATE crystal structures and known antimicrobial substrates.

| Protein | Subfamily | Organism | Bound/Transported Substrates | PDB ID | Resolution (A) | Ligand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NorM-Vc | NorM | Vibrio cholerae | Et, CFX, DXR, DNR, RBXL,R6G, NFX | 3MKT | 3.65 | |

| Refs [48,51,75,83] | 3MKU | 4.20 | Rb+ | |||

| NorM-Ng | NorM | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Et, TPP, R6G, CFX, NFX, AFh, NME, BE, BC | 4HUK | 3.60 | TPP, monobody |

| 4HUL | 3.80 | Cs+, monobody | ||||

| Refs [49,84,85] | 4HUM | 3.50 | ethidium, monobody | |||

| 4HUN | 3.60 | R6G, monobody | ||||

| 5C6P | 3.00 | verapamil, monobody | ||||

| PfMATE | DinF | Pyrococcus furiosus | Et, NFX, R6G | 3VVN | 2.40 | |

| Refs [53,56] | 3VVO | 2.50 | ||||

| 3VVP | 2.90 | Br-norfloxacin | ||||

| 3WBN | 2.45 | Cyclic peptide MaL6 | ||||

| 3VVR | 3.00 | Cyclic peptide MaD5 | ||||

| 3VVS | 2.60 | Cyclic peptide MaD3S | ||||

| 3W4T | 2.10 | |||||

| 6FHZ | 2.80 | |||||

| 6GWH | 2.80 | |||||

| 6HFB | 3.50 | Cs+ | ||||

| 4MLB | 2.35 | |||||

| DinF-Bh | DinF | Bacillus halodurans | CFX, TPP, R6G, Dequalinium, Et, NFX,TPA | 4LZ6 | 3.20 | |

| 4LZ9 | 3.70 | R6G | ||||

| Refs [50,54] | 5C6N | 3.00 | ||||

| 5C6O | 3.00 | verapamil | ||||

| VcmN | DinF | Vibrio cholerae | CFX, Et, OFX, Hoechst 33342, Kan, NFX, Streptomycin | 6IDP | 2.20 | |

| 6IDR | 2.50 | |||||

| Refs [55,86] | 6IDS | 2.80 | ||||

| ClbM-Ec | DinF | Escherichia coli | Et, R6G, Precolibactin | 4Z3N | 2.70 | |

| Refs [66,67] | 4Z3P | 3.30 | Rb+ | |||

| DTX14-At | Eukaryotic | Arabidopsis thaliana | NFX | 5Y50 | 2.60 | |

| Ref [79] | ||||||

| CasMATE | Eukaryotic | Camelina sativa | 5XJJ | 2.90 |

Transported substrates for structurally characterized transporters are listed. AFh (acriflavine hydrochloride); BC (benzalkonium chloride); BE (berberine); CFX (ciprofloxacin); DXR (doxorubicin); DNR (daunorubicin); Et (ethidium); NFX (norfloxacin); NME (2-N-methylellipticinium); RBXL (ruboxyl); R6G (rhodamine 6G); TPA (tetraphenylarsonium); TPP (tetraphenyl phosphonium).

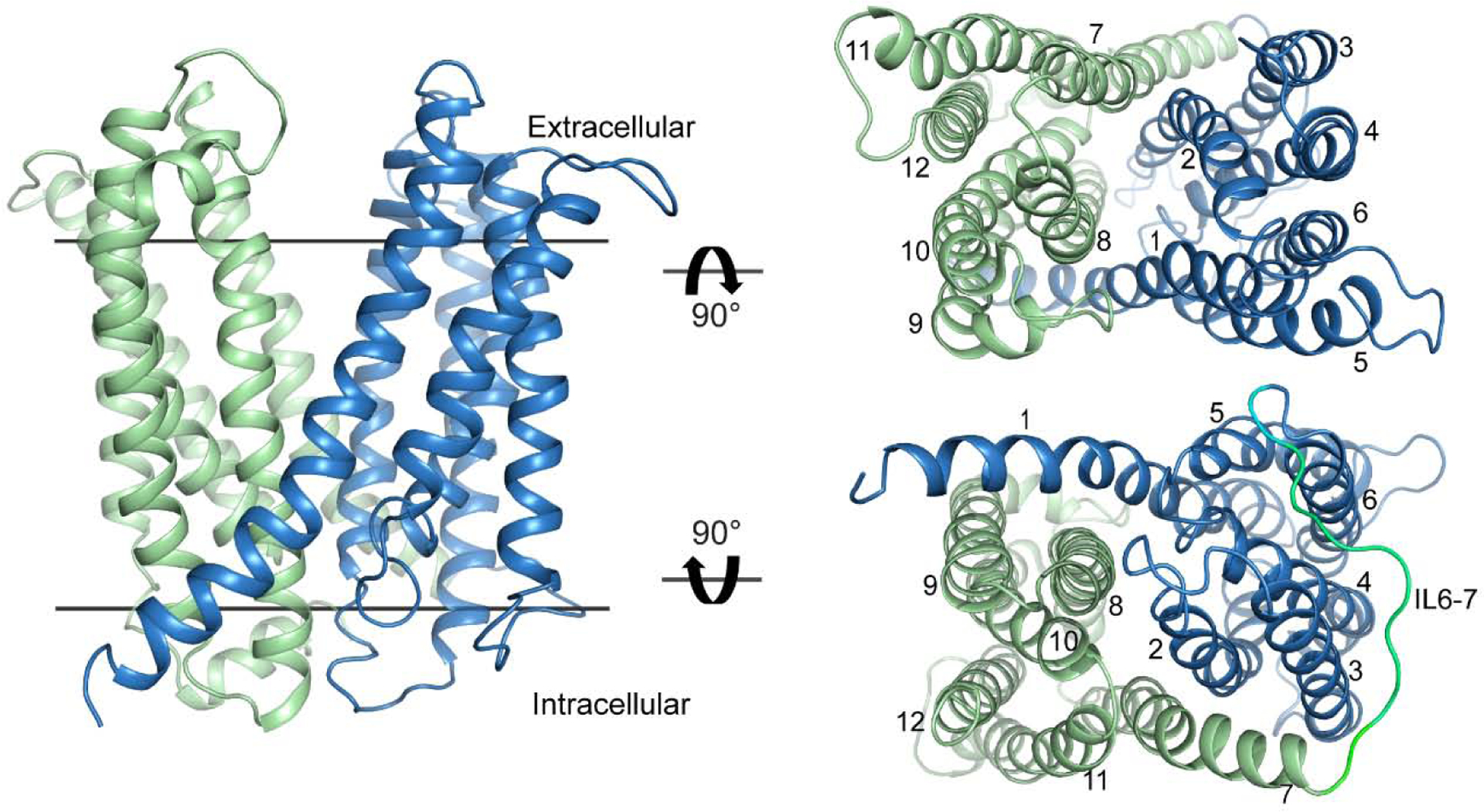

Figure 3. General topology and fold of MATE transporters.

The representative MATE transporter NorM-Vc (PDB ID 3MKT) displays structural features of the OF conformation. The N- and C- lobes are colored blue and green, respectively. Views from the extracellular (upper right) and intracellular (lower right) sides show 12 transmembrane helices arranged as two symmetric six-helix bundles that constitute the N- and C-lobes and are connected by a long intracellular loop (IL6–7, lower right).

Ligand binding sites and conformational changes in crystal structures of NorM transporters

Structural differences between OF conformations obtained in the presence or absence of ligands (ions or substrates) have been interpreted as unique intermediates in the transport cycle. At the determined resolution (Table 1), mapping of putative Na+ binding sites for Na+-coupled NorM transporters from V. cholerae (NorM-Vc) and N. gonorrheae (NorM-Ng) required heavy atom congeners, namely Rb+ and Cs+ [48,49]. These electron-dense analogs were found to bind to similar, although not identical, locations within the C-lobe coordinated primarily by conserved acidic sidechains (Glu and Asp) indispensable for function (Fig. 4a, inset). Despite this correspondence, a notable 20° tilt of TM7/8 was observed in the Cs+-bound structure of NorM-Ng relative to NorM-Vc (Fig. 4b). Presumably, this structural deviation was due to occupation of the NorM-Ng central cavity by an unidentified molecule. Indeed, crystal structures of NorM-Ng were found to adopt nearly identical OF conformations in the presence of tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP), ethidium, rhodamine 6G (R6G), and the MDR transporter inhibitor verapamil [49,50]. These compounds were docked to a common site near the membrane-water interface (Fig. 4b). Decorated with polar and acidic residues, including strictly conserved TM1 Asp41, the NorM-Ng drug binding site appeared to favorably interact with cationic substrates (Fig. 4b, inset). Using a spin-labeled derivative of daunorubicin in conjunction with double electron electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy, Steed et al. proposed a similarly located substrate binding site within the central cavity of NorM-Vc [51]. However, there are no substrate-bound NorM-Vc crystal structures available for direct comparison.

Figure 4. Alignment of the N-lobes of NorM-Vc and –Ng reveal structural deviations in the C-lobe and location of ligand binding sites.

NorM-Vc (PDB ID: 3MKU) and NorM-Ng (PDB ID: 4HUK) are depicted as cartoons. The N- and C-lobes for NorM-Vc are colored blue and green, respectively; for NorM-Ng, cyan and yellow, respectively. (a) The ion binding site in the C-lobe of both transporters is formed by conserved residues in the C-lobe (inset) that coordinate sodium congeners Rb+ (purple sphere, 3MKU) and Cs+ (brown sphere, 4HUK). Viewed from the extracellular side of the transporters (b), a 20° tilt of TM7/8 toward the membrane normal is observed in NorM-Ng relative to NorM-Vc. Residues within these helices (b, inset) coordinate the substrate TPP.

Unlike other well-characterized antiporters such as the SMR transporter EmrE [52], the crystal structures suggested that the ion and substrate binding sites were not overlapping in the NorM transporters. Thus, the proposed model of ion-coupled substrate efflux departed from the classical exchange mechanism that envisions mutually exclusive binding of ions and substrate to the same site. As a consequence of the subtle rearrangement of TM7/8 observed in NorM-Ng relative to NorM-Vc, it was suggested that ion-bound NorM-Vc represents a post-substrate release conformation [49]. That is, Na+ binding initiates substrate extrusion by inducing conformational changes that disrupt the multidrug binding site in the central cavity. This allosteric mechanism describes an “indirect competition” between ion and substrate mediated by global changes in protein structure to promote efflux.

Divergent transport mechanisms inferred from OF conformations in the DinF subfamily

Subsequent structural analyses of MATE transporters from the DinF subfamily occupying distinct OF conformations emphasized the unique chemistries of substrate binding sites and, consequently, promoted disparate mechanistic models. Relative to DinF from P. furiosus (PfMATE) [53], the structure of the H+-coupled transporter from B. halodurans DinF-Bh displayed a break in the topological symmetry of helices lining the central cleft (Fig. 5a) [54]. Defined by new packing interactions between TM1/2 with TM7/8, this asymmetry resulted in a wide, solvent-accessible crevice within the C-lobe while reducing access to the central cavity. The significance of this new conformation was inferred from crystal structures bound to R6G and a TPP analog [54]. Both drugs were found buried within a methionine-rich, low dielectric chamber coordinated by residues from the new TM1/TM8 interface as well as copious contacts from TM2, TM4, TM5 and TM6 (Fig. 5b). Unlike R6G binding to NorM-Ng [49], the positive charge of R6G was satisfied only through direct interaction with Asp40 (Asp41 in NorM-Ng). Disrupting this interaction by mimicking protonation (D40N) strongly impaired R6G binding, even though this substitution did not induce changes in the crystal structure [54]. Verapamil also was found to inhibit R6G extrusion, which is likely due to competition for binding to the hydrophobic chamber [50]. Since the C-lobe crevice remained unperturbed in these structures, the authors suggested that the unique conformation of TM7/8 mediated formation of an occluded binding site [54]. In concert with a canonical direct competition mechanism, protonation of Asp40 was hypothesized to promote substrate release from this OF state into the extracellular milieu via the C-lobe crevice (Fig. 5c). In contrast to NorM-Ng, this proposed mechanism did not invoke explicit conformational changes from the crystallized OF state. Instead, the substrate release pathway was demarcated by the lateral fenestration between TM7/8.

Figure 5. Comparison of PfMATE with DinF-Bh reveals structural deviations in the C-lobe and distinct substrate binding sites in the N-lobe.

(a) The superimposition reveals TM7/8 displacement in DinF-Bh (PDB ID: 4LZ9, cyan) toward the membrane normal relative to PfMATE (PDB ID: 3VVP, blue). Substrate binding sites are indicated for NFX (dark blue) in PfMATE and R6G (brown) in DinF-Bh. (b) The hydrophobic substrate binding chamber of DinF-Bh stabilizes the conjugated ring system of R6G. (c) A C-lobe fenestration formed by the topological asymmetry of TM7/8 denotes a probable path for substrate extrusion. (d) In addition to participating in NFX binding, Tyr37 of PfMATE engages an H-bond network (dashed lines) involving conserved residues D41 and D184. (e) Mapping of the root mean square deviation (rmsd) between Straight (pH 8.0, PDB ID: 3VVN) and Bent (pH 6.0, PDB ID: 3VVO) conformations of PfMATE onto a ribbon representation of 3VVN indicates the proposed H+-induced structural changes of TM1, 5 and 6. TM1 bending (e, inset), facilitated by the strictly conserved Pro26, collapses the substrate binding cavity.

A collection of PfMATE crystal structures argued for an entirely different mechanism of efflux grounded in a putative H+-coupled conformational change of TM1 and a novel substrate binding site [53]. At pH 8, the PfMATE crystal structure adopted a similar conformation as NorM-Vc and NorM-Ng in which splaying of the large central cavity formed by TM1/2 and TM7/8 helices remained intact. However, a pronounced bending of TM1 toward TM2 was observed at pH 6 enabled by kinks at conserved residues Pro26 and Gly30 in addition to an outward movement of TM5 and TM6 (Fig. 5e, inset). Notably, the structural change of TM1 was associated with a rearrangement of H-bonds between conserved polar sidechains, including the critical Asp41. Substitution of a select panel of these residues compromised resistance to the fluoroquinolone norfloxacin (NFX), suggesting that residues mediating the conformational change are involved in efflux. In support of this interpretation, an NFX-derivative compound (Br-NRF) was found to bind to a cavity within the N-lobe that collapsed in the bent state. Asp41 did not interact directly with Br-NRF, consistent with a distinct substrate binding mode relative to DinF-Bh. However, a few residues that contributed to the drug binding site (Tyr37, Asn180 and Thr202) also participated in H-bonds that facilitated TM1 bending (Fig. 5d). These observations led to the proposal that H+-driven conformational changes in TM1 pushes substrate out of the N-lobe binding site [53].

Whereas molecular details of transport could be expected to display variations between MATE subfamilies, the stark differences in the structure-based mechanisms of DinF-Bh and PfMATE, members of the same MATE subfamily, have elicited controversy based on differences in crystallization approaches or data quality [50,55]. The extent to which these mechanisms may reflect evolution of substrate binding sites and/or permeation pathways between an archaeal and bacterial transporter is not clear. Bending of TM1 has yet to be observed in DinF-Bh. However, structural analysis of WT and mutant VcmN, a H+-dependent DinF transporter from V. cholerae (Table 1) suggested that TM1 bending could be a common feature in the MATE transport cycle [55]. Recently, we presented a study of PfMATE that supports mechanistic divergence and a unique binding site for a substrate (R6G) shared with DinF-Bh [56]. Unlike DinF-Bh, high affinity R6G binding to PfMATE did not require the strictly conserved TM1 Asp41. Similar to NFX resistance, PfMATE-mediated resistance to R6G toxicity in E. coli cell growth assays was dependent on sidechains in the N-lobe that were shown to be either involved in an intricate H-bond network or enabled TM1 bending. Substitution of these sidechains did not alter R6G binding affinity, yet disrupted the pattern of H+-dependent fluorescence quenching of nearby Trp44 (Fig. 5d). Interpreting the quenching behavior as a surrogate reporter of TM1 dynamics, the data suggested that these N-lobe residues mediate H+ coupling through the formation of a structural intermediate defined by localized TM1 conformational changes required for transport [56].

The IF conformation of PfMATE implies a rocker-switch mechanism

In the context of alternating access, the MATE transporter OF crystal structures postulate ligand binding modes and probable pathways for substrate release. Critical details of substrate transport from the cytoplasm or the membrane remained ambiguous in the absence of IF conformations. Given the bi-lobe architecture reminiscent of MFS transporters, formation of an IF conformation could proceed via relative rigid body rotation of the lobes within the plane of the membrane akin to the “rocker-switch” mechanism proposed for the MFS [32,57,58].

A recently described IF conformation of PfMATE indeed implied such movements relative to the OF conformation [47]. Closure of the central cavity on the periplasmic side entailed formation of a dense network of hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions between aliphatic sidechains in TM1, TM2, TM8 and TM10 thereby establishing a 10Å-thick gate (Fig. 6a). A similar periplasmic interface was predicted for an IF conformation of NorM-Ng based on guided molecular modeling and cysteine cross-linking experiments [59]. On the other hand, formation of the IF of PfMATE required rupture of an even thicker (14Å) intracellular gate involving both hydrophobic and ionic interactions (Fig. 6b, inset). The combination of these intracellular molecular interactions likely account for greater stability of the OF intermediates as inferred from a host of crystal structures.

Figure 6. PfMATE intracellular and extracellular gates are mediated by unique molecular interactions.

(a) The IF conformation of PfMATE (PDB ID: 6FHZ) is depicted as a cartoon with the N- and C- lobes colored blue and green, respectively. Helical periodicity of TM1 is disrupted and pivots about Gly30 ~27° in the Y/Z plane and 42° in the X/Z plane. Viewed from the extracellular side (a, upper panel), residues involved in hydrophobic interactions are depicted as sticks while those involved in van der Waals interactions are depicted as spheres (a, inset). Formation of the extracellular gate is concomitant with opening of the central cavity to the intracellular side (a, lower panel). (b) In contrast, the intracellular gate of the OF conformation is mediated by hydrophobic (yellow sticks) and ionic (cyan sticks) interactions (b, middle panel).

Two critical elements of the isomerization between the two states should be noted. First, conformational flexibility of TM1 and TM7 allowed for these helices to retain N- and C-lobe interactions present in the OF state (Fig. 6a, lower panel). Strikingly, TM1 is partially unfolded in the IF crystal structure (Fig. 6a), a feature that has been called into question recently (see below), while TM7 retains its α-helical character. Secondly, LCP crystallization of the IF required doping the sample with native P. furiosus lipids. In the absence of these lipids, PfMATE crystallized in the OF conformation under otherwise identical conditions for crystallization of the IF state (pH 5). Although specifically-bound lipids could not be assigned, the authors implied that these lipids alter the conformation of PfMATE by operating as a substrate; i.e., PfMATE is ostensibly a lipid transporter [47]. However, substrates should drive the OF, not the IF, conformation according to the antiport model (Fig. 2). Interestingly, stable binding of lipids to PfMATE were observed only in the OF conformation in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [41]. Thus, the driving forces for interconversion between the OF/IF conformations were unclear from simple analysis of the crystal structures.

Conformational snapshots of the evolutionarily-related MOP transporter MurJ

Despite the absence of significant sequence similarity, MATE transporters share an equivalent topological arrangement with the first 12 helices of the bacterial MOP lipid II flippase MurJ [60]. Besides the symmetry-related N- and C-lobes, MurJ bears two ancillary C-terminal TM segments that form a hydrophobic groove predicted to bind the undecaprenyl tail of lipid II (Fig. 7a). A series of crystal structures and cysteine crosslinking experiments has indicated that MurJ operates via a “rocker-switch” alternating access mechanism determined by the relative orientation of the N- and C-lobes [61,62]. Interestingly, MurJ crystal structures have been found to adopt a range of IF conformations in addition to the OF conformation.

Figure 7. OF and IF conformational states of MurJ.

(a) MurJ, a putative Lipid II flippase within the MOP superfamily, is composed of 14 TMs arranged as two symmetric six-helix bundles, similar to MATE transporters, but with two ancillary C-terminal TMs that are involved in lipid binding and transport. The N- and C-lobes are colored blue and green, respectively. TMs 13 and 14 of MurJ are depicted as beige ribbons. (b) TM1 from MurJ occupies a number of distinct conformations in the IF state relative to TM1 from PfMATE (blue).

The assignment of four distinct IF conformations (inward closed, inward, inward occluded and inward open) was informed by the size of a membrane “portal” defined by the spatial arrangements of TM1, TM8, and the TM4–5 loop (in accord with MATE topology) [61]. The flexibility of TM1 combined with the dynamics of TM8 and the TM4–5 loop appeared to govern access to the substrate binding cavity. Similar to PfMATE [47], TM7 in MurJ is also highly flexible and predicted to support transition to the OF by supplying tension to the long cytoplasmic TM6–7 loop [61]. However, TM1 of MurJ deviates from that observed in the IF crystal structure of PfMATE specifically through disengagement of the C-lobe while retaining secondary structure (Fig. 7b). The extent to which these MurJ intermediates offers a glimpse of potential MATE transporter IF conformations is not known. Residues in TM1 and the TM4–5 loop are strongly conserved in MurJ homologs, but not MATE transporters [61]. Thus, the molecular details of the proposed lateral gate mechanism of MurJ may reflect specialization for lipid-linked oligosaccharide flipping.

Alternating access and energy landscapes

A fundamental challenge in the structural biology of MATE transporters is defining the general mechanistic principles that are conserved among the MATE family while differentiating idiosyncratic features that arise from diverse efflux mechanisms for subfamilies and organisms. MATE transporter crystal structures from across the evolutionary spectrum have showcased similar structural features of the OF and, in some cases, putative ligand-dependent rearrangements [27]. Yet a number of factors have conspired to obfuscate the relationship of these conformers in the transport cycle. A limited set of models for each MATE family member occupying distinct conformational states inherently limits a structure-based interpretation of ion-coupled transport. Furthermore, the relative energies of these conformations that shape the energy landscape cannot be deduced within the confines of a crystal lattice. Defining the landscape necessitates assignment of the conformational state of crystal structures combined with explicit measurement of the role of substrates and ions in driving formation of intermediates associated with alternating access. Moreover, the transport energy landscape is dependent on the detergent or lipid environment of the transporter [63–65].

Further confounding the understanding of MATE transporter alternating access is mounting evidence for promiscuity in the cation coupling mechanism. Ethidium and R6G efflux by ClbM, a DinF subfamily member implicated in the export of precolibactin from E. coli, has been shown to be facilitated by a Na+ gradient in whole cell assays [66,67]. Although the mechanism is not clear, K+ and Rb+ also supported drug efflux yet to a lesser extent than Na+. Additionally, efflux was observed to be modulated by the extracellular proton concentration even in the absence of the other alkali cations, suggesting a role for the proton motive force [66]. Similarly, transport assays of reconstituted NorM-Vc have suggested that it couples to both Na+ and H+ gradients simultaneously [68].

Questions regarding the nature and veracity of crystallographic Na+ binding sites in the C-lobe identified by monovalent heavy atoms (Cs+, Rb+) add another layer of complexity. The binding of these congeners simply could reflect localized electronegative patches rather than specific Na+ sites with optimal sidechain coordination geometry. For example, non-protein electron density found in the N-lobe of PfMATE, ClbM, and VcmN, originally regarded as an ordered water molecule that mediates H+ transfer, has been reinterpreted as a Na+ based on sequence analysis, modeling and MD simulations [43,69,70]. Notably, the computational analysis of PfMATE suggested that the N-lobe ion binding motif (including Asp41) demonstrates strong selectivity for Na+ over K+ (and, by extension, larger Cs+ and Rb+), yet is marginally selective over H+ [70]. Nevertheless, H+ coupling was hypothesized to be mediated by other sidechains residing in the C-lobe [70]. Additional crystallographic and computational analysis of PfMATE provided some support for this proposal [47], although the mechanistic role of Na+ in PfMATE alternating access is not known.

In order to address central issues of transporter dynamics and energy coupling, biophysical approaches that can detect distinct structural states under thermodynamic equilibrium are necessary. Only a few studies reported to date have investigated the conformational dynamics of MATE transporters. Interpreted in light of available crystal structures and in combination with functional analysis, the studies described below have outlined ligand-dependent alternating access consistent with the antiport model, elucidated the role of residues critical for transport and uncovered novel mechanistic insights.

Equilibrium measurements of conformational dynamics

Substrate drives an OF conformation of NorM-Ps

HDX-MS [71,72] experiments of the H+-coupled NorM transporter from Pseudomonas stutzeri (NorM-Ps) have explored conformational sampling in n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) detergent micelles in the absence and presence of the cationic substrate DAPI [73]. Based on a homology model derived from NorM-Vc (Fig. 3), DAPI binding increased deuterium uptake along periplasmic helices lining the central cavity (TM1 and TM8). Additionally, deuterium uptake was reduced for helices surrounding the cavity at the predicted DAPI binding site in the C-lobe and portions of the cytoplasmic side of the transporter. The pattern of changes were interpreted as consistent with a “rocker-switch” antiport model (Fig. 2) that posits formation of an OF structure promoted by substrate binding [73].

The significance of these findings was investigated further by HDX-MS of mutants known to compromise pH-dependent transport activity. D38N (N-lobe, TM1) and D373N (C-lobe, TM10) of NorM-Ps were shown previously to abrogate DAPI efflux from everted vesicles [74]. Corresponding to the functionally-required Asp36 in NorM-Vc (Fig. 1), Asp38 in NorM-Ps is predicted to facilitate ion entry into the transporter according to MD simulations of NorM-Vc [46]. Incorporation of D38N altered the pattern of deuterium uptake upon DAPI binding relative to the wild type protein, suggesting an incomplete transition to the OF conformation [73]. On the other hand, Asp373 was predicted to contribute to the substrate binding site since D373N substantially reduced affinity (>10 fold) for DAPI as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry [74]. Indeed, limited DAPI-induced changes in the HDX-MS map of the D373N mutant were consistent with reduced substrate binding. Informed by these measurements, the authors proposed that NorM-Ps catalyzes efflux of DAPI from a mutually-exclusive substrate/H+ binding site in the C-lobe [73].

Role of conserved residues in ligand binding and conformational dynamics of NorM-Vc

Using a distinct and multifaceted methodological approach, Claxton et al. applied DEER spectroscopy combined with substrate binding and in vivo drug-resistance assays to elucidate the contribution of highly conserved sidechains to the conformational cycle of NorM-Vc [75]. Specifically, the study focused on a select panel of conserved polar sidechains located in the N-lobe near the membrane-water interface, as well as two carboxylate residues conserved in the NorM subfamily that project into the core of the C-lobe (Fig. 1 and Fig. 8a). The N-lobe cluster included the critical Asp36 and is analogous to the network of residues in PfMATE predicted to bind Na+ or mediate H+ transfer (Fig. 8a, right inset). In contrast to the carboxylates in the C-lobe (Fig. 8a, left inset), residue substitutions in the N-lobe were observed to modulate Na+- and H +-driven conformational dynamics as reported by distance changes between spin labels fingerprinting the periplasmic cleft (Fig. 8b). However, the N-lobe substitutions did not substantially reduce DXR binding affinity or prevent formation of the DXR-bound intermediate (Fig. 8b–c). A plot that correlated the ion-dependent changes between distance distributions (root mean square deviation, RMSD) of the reporter pair 45/269 with the in vivo DXR resistance profile of N-lobe mutants established the relationship of Na+ and H+ intermediates to function (Fig. 8d). A robust structural response, defined by relatively large RMSD to either Na+, H+ or both, correlated with transport-competent NorM-Vc. These results strongly implied that the N-lobe contained an ion binding site to mediate entry of Na+ and H+, consonant with conclusions from MD simulations of NorM-Vc [46] and PfMATE [70].

Figure 8. Role of conserved residues in the conformational cycle of NorM-Vc.

Ligand binding sites in the N- and C-lobe of NorM-Vc (PDB ID: 3MKT) determined from DEER spectroscopy and functional analysis are shown in (a). Critical residues in the C-lobe (left inset) and N-lobe (right inset) are depicted as sticks. The location of spin labels for the reporter 45/269 pair is shown as purple spheres connected by a dashed line. (b) Site directed mutagenesis of Asp36 and Asp371 alter the structural response to ions and substrate, respectively. The distance distributions, P(r), of the reporter pair that retains the functional residues are shaded for each biochemical condition. P(r) for D36N and D371N are shown as solid lines. (c) Loss of DXR binding affinity at low pH is indicated by a right shift in the binding isotherm. Mutation of C-lobe residue Asp371 likewise reduces DXR binding affinity at pH 7.5. (d) Correlation of in vivo DXR resistance activity mediated by NorM-Vc mutants with the ion-driven structural transitions quantified by the RMSD between distance distributions. The change in of each mutant corresponds to the color and size of each data point according to the scale.

In addition to this discovery, the structural and functional characterization of the acidic residues in the C-lobe (Glu255 and Asp371) uncovered striking similarities to the proposed substrate binding and release mechanism of NorM-Ps. These carboxylate moieties, equivalent to Glu257 and Asp373 that mediate DAPI binding in NorM-Ps [74], were found to be essential for in vitro doxorubicin (DXR) binding and in vivo resistance to DXR toxicity [75]. Binding isotherms generated from changes in DXR fluorescence anisotropy indicated a substantial loss of high affinity binding upon neutralization of the negatively-charged sidechains with E255Q and D371N, substitutions thought to mimic protonation (Fig. 8c). Although the mutant binding curves were obtained at pH 7.5, the KDs were similar to measurements collected at pH 4 with a NorM-Vc construct that retained the wild type residues. Despite the original hypothesis that Glu255 and Asp371 participate in Na+ coordination based on a Rb+-bound NorM-Vc crystal structure [48], the functional analysis suggested that these residues instead participate in binding of cationic substrates [75]. Additionally, the correlation between altered DXR binding affinity of E255Q and D371N with pH-dependent DXR binding implicated protonation of these sidechains in substrate release. In support of this model, DEER spectroscopy revealed that DXR-dependent structural rearrangements were impaired by E255Q and D371N (Fig. 8b). Together, the spectroscopic and functional analysis supported an efflux mechanism in which Na+-dependent structural changes facilitate enhanced water penetration into the central cavity to promote H+-induced substrate release from its binding site in the C-lobe. Importantly, this proposed mechanism rationalized the dual ion dependence observed in transport studies of NorM-Vc [68].

Energetics of alternating access in PfMATE reconstituted into lipid bilayers

The spectroscopic analysis of NorM-Vc described above provided a connection between population of distinct ligand-dependent intermediates and conserved residues crucial for function. Yet the interpretation of the study was limited since it did not probe the structural dynamics of the cytoplasmic gate. Recently, an exhaustive DEER investigation of more than 40 spin label pairs in PfMATE effectively captured the OF/IF transitions by mapping structural rearrangements of helices on both sides of the transporter [76]. Shifts in the equilibrium population of discrete distance components associated with binding of ions or the substrate R6G were interpreted in the context of an OF/IF conformational change outlined by the crystal structures.

Fundamental to this study was the reconstitution of purified PfMATE into lipid nanodiscs, a discoidal phospholipid bilayer mimic surrounded by an annulus of amphipathic scaffold protein [77]. Ligand-driven changes in spin label distance distributions were minor or non-existent for PfMATE mutants purified into DDM micelles [76]. In contrast to crystallization of the IF state [47], native P. furiosus lipids were not required explicitly to observe PfMATE interconversion. While native lipids are expected to influence the conformational energy landscape, the strong correspondence between spectroscopic and crystallographic states (discussed further below) suggested that even a non-native lipid environment sufficiently reduced the energy barrier for isomerization to occur.

The collective DEER dataset uncovered a simple pattern of structural changes and identified the energetic driving forces for stabilizing the IF and OF conformations. Spin label pairs sampling distance changes between the N- and C-lobes unambiguously demonstrated H+ induced (achieved by lowering the pH from 7.5 to 4.0) opening of the cytoplasmic gate concomitant with closure of the periplasmic gate (Fig. 9). As shown in Fig. 9a, the addition of H+ decreased the average distance (red solid lines) between periplasmic reporter pairs relative to basic pH (solid black lines). In contrast, distances between intracellular pairs increased with protonation (Fig. 9b), indicating that the OF-to-IF transition is driven by H+. RG6 binding induced the opposite pattern of distance changes [76], in keeping with the antiport model (Fig. 1). Whereas large-amplitude motion between helices was observed across the central cavity, intra-lobe dynamics were limited, consistent with relative rigid body rotation of the N- and C-lobes. Notably, no discernable changes in distance distributions were elicited by Na+, even though this ion was predicted to bind in the N-lobe according to computational [70] and crystallographic [47] studies.

Figure 9. Protons induce population of the IF conformation in PfMATE.

Spin labeled pairs sampling distances between the N- and C-lobes are shown as purple spheres connected with a dashed line and are depicted on the extracellular side (a) and intracellular side (b) of the OF structure (PDB ID: 3VVN). Experimentally-determined distance distributions (solid lines) are plotted with the predicted distance distributions derived from the OF (black, dashed traces) and the IF (red, dashed traces) crystal structures. (a) Measurements from sites on TMs in the C-lobe to sites on TMs in the N-lobe on the extracellular side of the transporter demonstrate H+-dependent decreases in distance between spin labels. (b) In contrast, measurements from sites in the C-lobe to sites in the N-lobe on the intracellular side of the transporter report increases in distance.

Solidifying the role of H+ in the alternating access mechanism was the discovery that the interconversion between OF and IF was strictly dependent on protonation of Glu163 found on the cytoplasmic TM4–5 loop [76]. In the OF conformation, this charged sidechain likely interacts with Tyr224 in the TM6–7 cytoplasmic loop (Fig. 10a). Ala substitution of either residue compromised resistance to R6G toxicity despite retaining high affinity R6G binding (Fig. 10a). Remarkably, the E163A and Y224A substitutions promoted isomerization of PfMATE to the IF state (Fig. 10b). Inspection of DEER data from spin label reporter pairs (44/364 and 95/318) on both sides of PfMATE revealed that the distance distributions in the E163A and Y224A backgrounds (solid lines, Fig. 10b) preferentially overlapped the distance components corresponding to the IF conformation of the native construct (shaded red), even at basic pH. This result indicated that Glu163 and Tyr224 are required for stabilizing the OF conformation. These novel findings highlighted intramolecular interactions between cytoplasmic loops in mediating the H+-dependent OF-to-IF transition, contributing a missing element in the transport model along the line to that hypothesized for MurJ [61]. Namely, tension in the long TM6–7 loop that supports cytoplasmic gate closure is released as a consequence of a broken pi-charge interaction through protonation of Glu163 [76].

Figure 10: Protonation of Glu163 facilitates OF-to-IF interconversion in PfMATE.

(a) Glu163 on IL4/5 and Y224 on IL6/7 are depicted as sticks on a cartoon representation of OF PfMATE. (a, bottom panel) Mutation of these residues compromises PfMATE-conferred resistance to toxic concentrations of R6G in a cell based assay. P(r) of E163A and Y224A mutations introduced into extracellular (44/364) and intracellular (95/318) reporter pairs (b, solid lines; upper and lower panels, respectively) is compared with the P(r) of the native construct that retains the wild type residues (shaded distributions) at pH 4 and pH 7.5. The distance components corresponding to the OF and IF conformations on each plot are indicated. E163A and Y224A abrogate the H+-dependent alternating access and destabilize the OF conformation at pH 7.5. (c) A network of polar and charged residues lining the N-lobe could mediate proton translocation from the conserved N-lobe cluster near the periplasmic membrane-water interface to Glu163 on the cytoplasmic side of PfMATE.

Interestingly, residue substitutions in the conserved N-lobe network demonstrated only marginal impact on the H+-induced IF state despite severely weakened drug resistance [56,76]. Perturbation of the N-lobe cluster could result in diminished transport rates, but these were not measured. Alternatively, the substitutions could disrupt a H+ translocation pathway formed by a conduit of polar and charged sidechains linking the N-lobe network with Glu163 (Fig. 10c). Methodologically, the DEER analysis of PfMATE in nanodiscs did not require the imposition of a H + gradient. Presumably, increasing the H+ concentration through buffer conditions effectively bypassed the translocation pathway to protonate Glu163 and trigger isomerization to the IF state.

Importantly, the extensive spectroscopic analysis allowed for an unequivocal evaluation of the mechanistic context of the OF and IF PfMATE crystal structures. In most cases, the DEER-derived distance distributions (solid lines) corresponded remarkably well with predictions (dashed lines, Fig. 9). However, deviations were apparent for TM1 on both the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides [76]. Distance measurements from TM1 reported mostly limited H+-driven structural changes. Specifically, DEER analysis of TM1 pairs were inconsistent with helix unwinding observed in the IF crystal structure (Fig. 6a) [47]. Crystal packing interactions at the N-terminus were thus proposed to induce non-native secondary structure of TM1. In fact, the DEER data supported an intact TM1 helix that remains engaged with the C-lobe and mirrors the symmetry-related structure of TM7, which is contrary to models of TM1 in MurJ IF structures (Fig 7). Moreover, the global shift toward shorter average distances of TM1 pairs on the periplasmic side strongly diverged from the “bent” TM1 configuration proposed by Tanaka et al [53].

Perspective: Fold conservation and mechanistic divergence

The convergence of crystallographic models with functional analysis and biophysical interrogation has begun to illuminate the principles governing alternating access mechanisms in MATE transporters. The preponderance of evidence accumulated from various homologs spanning the MATE phylogenetic tree supports a consensus “rocker-switch” conformational cycle to facilitate ion-coupled antiport. Yet the collective body of work highlights apparent evolutionary shifts in the molecular details, emphasizing diversified molecular mechanisms accomplished with recycled structural folds (Fig. 11).

Figure 11. Putative efflux mechanisms in MATE transporters.

The integration of functional and biophysical studies with crystal structures of MATE transporters highlights mechanistic divergence across subfamilies. The locations of known ion (H+ or Na+) binding sites (orange spheres) are shown relative to the predicted substrate binding sites and proposed permeation pathways (purple region) on cartoon renderings of crystal structure representatives (PDB IDs 5XJJ, 3MKT, 3VVN and 6FHZ, left to right). The structural variation of TM7/8 captured in DinF-Bh (PDB ID 4LZ9, dark blue helices) is mapped onto the structure of PfMATE for comparison. Unlike the DinF subfamily, crystal structures of IF conformations have yet to be determined for eukaryotic and NorM MATE transporters.

As the most thoroughly characterized archetype of prokaryotic MATE transporters, the structural dynamics of PfMATE offer a blueprint of alternating access that can guide the generation of hypotheses of energy coupling in other MATE family members. For example, the mechanistic similarity between PfMATE and MurJ epitomized by the TM6–7 loop functioning as a fulcrum for isomerization argues for broad conservation across the MOP superfamily. However, the energetic basis for powering conformational transitions is most certainly different. Unlike PfMATE, MurJ transport is thought to be independent of H+, yet dependent on the membrane potential [78]. However, Na+ binding in the C-lobe of MurJ may be pivotal to stabilizing the OF conformation [61]. Given that isomerization between PfMATE OF/IF conformations was observed spectroscopically in the absence of Na+ [76], the structural consequences of Na+ binding in the predicted N-lobe site (or elsewhere) are yet to be determined. Based on the potential for multiple ionic species to support transport in ClbM [66] and NorM-Vc [68], thermodynamic coupling to more than one ion may be the rule rather than the exception.

Regardless of the coupling ion, the highly conserved sequence and structural features of the N-lobe in archaeal and bacterial MATE transporters appear essential for ion coordination and entry into a translocation pathway. Interestingly, this network of charged and polar sidechains is not conserved in the Eukaryotic branch (Fig. 1). Instead, structures of two plant MATE transporters CasMATE (C. sativa) and DTX14-At (A. thaliana) possess a well-conserved patch of acidic and polar sidechains in the C-lobe near to the central cavity that is proposed to mediate mutually exclusive H+/substrate binding [79,80]. Two of these residues in DTX14-At, Glu265 and Asp383, correspond to Glu273 and Glu389 in hMATE1 (Fig. 2). Like DTX14-At, substitution of these residues in hMATE1 abrogates transport activity [81]. Accordingly, site directed mutagenesis of the homologous acidic residues in the C-lobe of NorM-Vc [75] and NorM-Ps [74] results in the same reduced activity, arguing for shared mechanistic elements between NorM and Eukaryotic subfamilies.

The presence of buried carboxylates in the C-lobe likely serves as a proxy indicator of the overall chemical properties of substrates. A comparison of a select group of MATE transporter structures from each subfamily underscored the disparity in electrostatic potential of the central cavity [80]. Based on the presence of the conserved carboxylates and a negative electrostatic potential, a substrate binding pocket would be expected to reside in the C-lobe near the central cleft in NorM-Ng, NorM-Vc and CasMATE (approximate location shown in Fig. 11) [27]. Thus, the crystallographic drug binding sites captured within the large cavity near the membrane-water interface of NorM-Ng (Fig. 4) may reflect transient binding along the substrate permeation pathway [49]. In stark contrast with NorM-Vc, NorM-Ng and CasMATE, the internal pocket formed between the N- and C-lobes is distinctly cationic in PfMATE and DinF-Bh [80]. The electropositive cavity in PfMATE, similar to MurJ, has been presented as evidence that PfMATE is a transporter for endogenous negatively-charged lipids [47], potentially rationalizing its poor performance in efflux of cationic toxins in cell-based assays [47,56]. Notably, electron densities within the N- and C-lobes of PfMATE crystal structures were interpreted as belonging to monoolein lipid chains used in the LCP crystallization approach [53].

Sophisticated transport models from finely-tuned experiments that clarify principles of ion selectivity and translocation, map substrate permeation pathways and identify the residues that shape these molecular interactions should consider the energetic contribution of lipid bilayers. As demonstrated by our work with PfMATE [76], lipid nanodiscs lowered the energy barrier to the H+-induced OF-to-IF transition, which was undetectable in the context of detergent micelles. The role of lipids in modulating the conformational energy landscape cannot only be appreciated from the perspective of MATE transporters, but also other MDR families that demonstrate robust structural and functional responses to distinct lipid compositions [82]. The integration of these fundamental factors will be necessary to elucidate a comprehensive view of MATE transporter alternating access mechanisms.

Highlights.

MATE transporters mediate xenobiotic extrusion and contribute to multidrug resistance

Crystal structures of MATE transporter family members have captured distinct conformational intermediates interpreted in the context of an alternating access mechanism

Biophysical and computational studies have illuminated fundamental aspects of ion binding and energy coupling in the conformational cycle

Systematic integration of the structural and functional analysis emphasizes divergent molecular mechanisms

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a NIH grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01-GM077659 to Hassane S. Mchaourab.

Abbreviations

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- TM

transmembrane helix

- OF

outward-facing

- IF

inward-facing

- LCP

lipidic cubic phase

- R6G

rhodamine 6G

- TPP

tetraphenylphosphonium

- NFX

norfloxacin

- DEER

double electron electron resonance

- HDX-MS

hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

- DDM

n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Du D, van Veen HW, Murakami S, Pos KM & Luisi BF (2015). Structure, mechanism and cooperation of bacterial multidrug transporters. Curr Opin Struct Biol 33, 76–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins CF (2007). Multiple molecular mechanisms for multidrug resistance transporters. Nature 446, 749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alibert S, N’Gompaza Diarra J, Hernandez J, Stutzmann A, Fouad M, Boyer G & Pages JM (2017). Multidrug efflux pumps and their role in antibiotic and antiseptic resistance: a pharmacodynamic perspective. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 13, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman MM, Fojo T & Bates SE (2002). Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer 2, 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair JM, Webber MA, Baylay AJ, Ogbolu DO & Piddock LJ (2014). Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 13, 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, Ouellette M, Outterson K, Patel J, Cavaleri M, Cox EM, Houchens CR, Grayson ML, Hansen P, Singh N, Theuretzbacher U & Magrini N (2018). Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 18, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delmar JA & Yu EW (2016). The AbgT family: A novel class of antimetabolite transporters. Protein Sci 25, 322–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan KA, Liu Q, Elbourne LDH, Ahmad I, Sharples D, Naidu V, Chan CL, Li L, Harborne SPD, Pokhrel A, Postis VLG, Goldman A, Henderson PJF & Paulsen IT (2018). Pacing across the membrane: the novel PACE family of efflux pumps is widespread in Gram-negative pathogens. Res Microbiol 169, 450–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saier MH Jr. & Paulsen IT (2001). Phylogeny of multidrug transporters. Semin Cell Dev Biol 12, 205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tal N & Schuldiner S (2009). A coordinated network of transporters with overlapping specificities provides a robust survival strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 9051–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers EE, Wu X, Stacey G & Nguyen HT (2009). Two MATE proteins play a role in iron efficiency in soybean. J Plant Physiol 166, 1453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Zhu H, Pan Y, Yu Y, Luan S & Li L (2014). A DTX/MATE-type transporter facilitates abscisic acid efflux and modulates ABA sensitivity and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 7, 1522–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener AC, Gaxiola RA & Fink GR (2001). Arabidopsis ALF5, a multidrug efflux transporter gene family member, confers resistance to toxins. Plant Cell 13, 1625–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maron LG, Pineros MA, Guimaraes CT, Magalhaes JV, Pleiman JK, Mao C, Shaff J, Belicuas SN & Kochian LV (2010). Two functionally distinct members of the MATE (multi-drug and toxic compound extrusion) family of transporters potentially underlie two major aluminum tolerance QTLs in maize. Plant J 61, 728–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuda S, Terada T, Yonezawa A, Tanihara Y, Kishimoto K, Katsura T, Ogawa O & Inui K (2006). Identification and functional characterization of a new human kidney-specific H+/organic cation antiporter, kidney-specific multidrug and toxin extrusion 2. J Am Soc Nephrol 17, 2127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omote H, Hiasa M, Matsumoto T, Otsuka M & Moriyama Y (2006). The MATE proteins as fundamental transporters of metabolic and xenobiotic organic cations. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27, 587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otsuka M, Matsumoto T, Morimoto R, Arioka S, Omote H & Moriyama Y (2005). A human transporter protein that mediates the final excretion step for toxic organic cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 17923–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonezawa A & Inui K (2011). Importance of the multidrug and toxin extrusion MATE/SLC47A family to pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics/toxicodynamics and pharmacogenomics. Br J Pharmacol 164, 1817–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito S, Kusuhara H, Kuroiwa Y, Wu C, Moriyama Y, Inoue K, Kondo T, Yuasa H, Nakayama H, Horita S & Sugiyama Y (2010). Potent and specific inhibition of mMate1-mediated efflux of type I organic cations in the liver and kidney by pyrimethamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333, 341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura T, Yonezawa A, Hashimoto S, Katsura T & Inui K (2010). Disruption of multidrug and toxin extrusion MATE1 potentiates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol 80, 1762–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuda M, Terada T, Ueba M, Sato T, Masuda S, Katsura T & Inui K (2009). Involvement of human multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 in the drug interaction between cimetidine and metformin in renal epithelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329, 185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaatz GW, McAleese F & Seo SM (2005). Multidrug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus due to overexpression of a novel multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) transport protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49, 1857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAleese F, Petersen P, Ruzin A, Dunman PM, Murphy E, Projan SJ & Bradford PA (2005). A novel MATE family efflux pump contributes to the reduced susceptibility of laboratory-derived Staphylococcus aureus mutants to tigecycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49, 1865–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita Y, Kataoka A, Shiota S, Mizushima T & Tsuchiya T (2000). NorM of vibrio parahaemolyticus is an Na(+)-driven multidrug efflux pump. J Bacteriol 182, 6694–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita Y, Kodama K, Shiota S, Mine T, Kataoka A, Mizushima T & Tsuchiya T (1998). NorM, a putative multidrug efflux protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its homolog in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42, 1778–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown MH, Paulsen IT & Skurray RA (1999). The multidrug efflux protein NorM is a prototype of a new family of transporters. Mol Microbiol 31, 394–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusakizako T, Miyauchi H, Ishitani R & Nureki O (2020). Structural biology of the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion superfamily transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1862, 183154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hvorup RN, Winnen B, Chang AB, Jiang Y, Zhou XF & Saier MH Jr. (2003). The multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide (MOP) exporter superfamily. Eur J Biochem 270, 799–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M (2016). Structures of multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporters and their mechanistic implications. Channels (Austin) 10, 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jardetzky O (1966). Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature 211, 969–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell P (1957). A general theory of membrane transport from studies of bacteria. Nature 180, 134–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drew D & Boudker O (2016). Shared Molecular Mechanisms of Membrane Transporters. Annu Rev Biochem 85, 543–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuroda T & Tsuchiya T (2009). Multidrug efflux transporters in the MATE family. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794, 763–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boudker O, Ryan RM, Yernool D, Shimamoto K & Gouaux E (2007). Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature 445, 387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yernool D, Boudker O, Jin Y & Gouaux E (2004). Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature 431, 811–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dastvan R, Fischer AW, Mishra S, Meiler J & McHaourab HS (2016). Protonation-dependent conformational dynamics of the multidrug transporter EmrE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 1220–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jia R, Martens C, Shekhar M, Pant S, Pellowe GA, Lau AM, Findlay HE, Harris NJ, Tajkhorshid E, Booth PJ & Politis A (2020). Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry captures distinct dynamics upon substrate and inhibitor binding to a transporter. Nat Commun 11, 6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazmier K, Sharma S, Quick M, Islam SM, Roux B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA & McHaourab HS (2014). Conformational dynamics of ligand-dependent alternating access in LeuT. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y & Gouaux E (2005). Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl--dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reading E, Hall Z, Martens C, Haghighi T, Findlay H, Ahdash Z, Politis A & Booth PJ (2017). Interrogating Membrane Protein Conformational Dynamics within Native Lipid Compositions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 56, 15654–15657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verhalen B, Dastvan R, Thangapandian S, Peskova Y, Koteiche HA, Nakamoto RK, Tajkhorshid E & McHaourab HS (2017). Energy transduction and alternating access of the mammalian ABC transporter P-glycoprotein. Nature 543, 738–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgieva ER, Borbat PP, Ginter C, Freed JH & Boudker O (2013). Conformational ensemble of the sodium-coupled aspartate transporter. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20, 215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krah A, Huber RG, Zachariae U & Bond PJ (2020). On the ion coupling mechanism of the MATE transporter ClbM. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1862, 183137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung YM, Holdbrook DA, Piggot TJ & Khalid S (2014). The NorM MATE transporter from N. gonorrhoeae: insights into drug and ion binding from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J 107, 460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song J, Ji C & Zhang JZ (2013). Insights on Na(+) binding and conformational dynamics in multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporter NorM. Proteins 82, 240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanni S, Campomanes P, Marcia M & Rothlisberger U (2012). Ion binding and internal hydration in the multidrug resistance secondary active transporter NorM investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 51, 1281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zakrzewska S, Mehdipour AR, Malviya VN, Nonaka T, Koepke J, Muenke C, Hausner W, Hummer G, Safarian S & Michel H (2019). Inward-facing conformation of a multidrug resistance MATE family transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 12275–12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He X, Szewczyk P, Karyakin A, Evin M, Hong WX, Zhang Q & Chang G (2010). Structure of a cation-bound multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporter. Nature 467, 991–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu M, Symersky J, Radchenko M, Koide A, Guo Y, Nie R & Koide S (2013). Structures of a Na+-coupled, substrate-bound MATE multidrug transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 2099–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radchenko M, Symersky J, Nie R & Lu M (2015). Structural basis for the blockade of MATE multidrug efflux pumps. Nat Commun 6, 7995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steed PR, Stein RA, Mishra S, Goodman MC & McHaourab HS (2013). Na(+)-substrate coupling in the multidrug antiporter norm probed with a spin-labeled substrate. Biochemistry 52, 5790–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuldiner S (2014). Competition as a way of life for H(+)-coupled antiporters. J Mol Biol 426, 2539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka Y, Hipolito CJ, Maturana AD, Ito K, Kuroda T, Higuchi T, Katoh T, Kato HE, Hattori M, Kumazaki K, Tsukazaki T, Ishitani R, Suga H & Nureki O (2013). Structural basis for the drug extrusion mechanism by a MATE multidrug transporter. Nature 496, 247–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu M, Radchenko M, Symersky J, Nie R & Guo Y (2013). Structural insights into H+-coupled multidrug extrusion by a MATE transporter. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20, 1310–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusakizako T, Claxton DP, Tanaka Y, Maturana AD, Kuroda T, Ishitani R, McHaourab HS & Nureki O (2019). Structural Basis of H(+)-Dependent Conformational Change in a Bacterial MATE Transporter. Structure 27, 293–301 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jagessar KL, McHaourab HS & Claxton DP (2019). The N-terminal domain of an archaeal multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) transporter mediates proton coupling required for prokaryotic drug resistance. J Biol Chem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abramson J, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Verner G, Kaback HR & Iwata S (2003). Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science 301, 610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang Y, Lemieux MJ, Song J, Auer M & Wang DN (2003). Structure and mechanism of the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter from Escherichia coli. Science 301, 616–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radchenko M, Nie R & Lu M (2016). Disulfide Cross-linking of a Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion Transporter Impacts Multidrug Efflux. J Biol Chem 291, 9818–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuk AC, Mashalidis EH & Lee SY (2017). Crystal structure of the MOP flippase MurJ in an inward-facing conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24, 171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuk ACY, Hao A, Guan Z & Lee SY (2019). Visualizing conformation transitions of the Lipid II flippase MurJ. Nat Commun 10, 1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar S, Rubino FA, Mendoza AG & Ruiz N (2019). The bacterial lipid II flippase MurJ functions by an alternating-access mechanism. J Biol Chem 294, 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adhikary S, Deredge DJ, Nagarajan A, Forrest LR, Wintrode PL & Singh SK (2017). Conformational dynamics of a neurotransmitter:sodium symporter in a lipid bilayer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E1786–E1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garavito RM & Ferguson-Miller S (2001). Detergents as tools in membrane biochemistry. J Biol Chem 276, 32403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moller IR, Merkle PS, Calugareanu D, Comamala G, Schmidt SG, Loland CJ & Rand KD (2020). Probing the conformational impact of detergents on the integral membrane protein LeuT by global HDX-MS. J Proteomics 225, 103845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mousa JJ, Newsome RC, Yang Y, Jobin C & Bruner SD (2016). ClbM is a versatile, cation-promiscuous MATE transporter found in the colibactin biosynthetic gene cluster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 482, 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mousa JJ, Yang Y, Tomkovich S, Shima A, Newsome RC, Tripathi P, Oswald E, Bruner SD & Jobin C (2016). MATE transport of the E. coli-derived genotoxin colibactin. Nat Microbiol 1, 15009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jin Y, Nair A & van Veen HW (2014). Multidrug transport protein norM from vibrio cholerae simultaneously couples to sodium- and proton-motive force. J Biol Chem 289, 14624–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castellano S, Claxton DP, Ficici E, Kusakizako T, Stix R, Zhou W, Nureki O, McHaourab HS & Faraldo-Gomez JD (2021). Conserved binding site in the N-lobe of prokaryotic MATE transporters suggests a role for Na(+) in ion-coupled drug efflux. J Biol Chem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ficici E, Zhou W, Castellano S & Faraldo-Gomez JD (2018). Broadly conserved Na(+)-binding site in the N-lobe of prokaryotic multidrug MATE transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E6172–E6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chalmers MJ, Busby SA, Pascal BD, West GM & Griffin PR (2011). Differential hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analysis of protein-ligand interactions. Expert Rev Proteomics 8, 43–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Percy AJ, Rey M, Burns KM & Schriemer DC (2012). Probing protein interactions with hydrogen/deuterium exchange and mass spectrometry-a review. Anal Chim Acta 721, 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eisinger ML, Nie L, Dorrbaum AR, Langer JD & Michel H (2018). The Xenobiotic Extrusion Mechanism of the MATE Transporter NorM_PS from Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Mol Biol 430, 1311–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nie L, Grell E, Malviya VN, Xie H, Wang J & Michel H (2016). Identification of the High-affinity Substrate-binding Site of the Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE) Family Transporter from Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Biol Chem 291, 15503–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Claxton DP, Jagessar KL, Steed PR, Stein RA & McHaourab HS (2018). Sodium and proton coupling in the conformational cycle of a MATE antiporter from Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E6182–E6190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jagessar KL, Claxton DP, Stein RA & McHaourab HS (2020). Sequence and structural determinants of ligand-dependent alternating access of a MATE transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 4732–4740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bayburt TH & Sligar SG (2010). Membrane protein assembly into Nanodiscs. FEBS Lett 584, 1721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rubino FA, Kumar S, Ruiz N, Walker S & Kahne DE (2018). Membrane Potential Is Required for MurJ Function. J Am Chem Soc 140, 4481–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miyauchi H, Moriyama S, Kusakizako T, Kumazaki K, Nakane T, Yamashita K, Hirata K, Dohmae N, Nishizawa T, Ito K, Miyaji T, Moriyama Y, Ishitani R & Nureki O (2017). Structural basis for xenobiotic extrusion by eukaryotic MATE transporter. Nat Commun 8, 1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tanaka Y, Iwaki S & Tsukazaki T (2017). Crystal Structure of a Plant Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion Family Protein. Structure 25, 1455–1460 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matsumoto T, Kanamoto T, Otsuka M, Omote H & Moriyama Y (2008). Role of glutamate residues in substrate recognition by human MATE1 polyspecific H+/organic cation exporter. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294, C1074–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martens C, Shekhar M, Borysik AJ, Lau AM, Reading E, Tajkhorshid E, Booth PJ & Politis A (2018). Direct protein-lipid interactions shape the conformational landscape of secondary transporters. Nat Commun 9, 4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singh AK, Haldar R, Mandal D & Kundu M (2006). Analysis of the topology of Vibrio cholerae NorM and identification of amino acid residues involved in norfloxacin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50, 3717–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Long F, Rouquette-Loughlin C, Shafer WM & Yu EW (2008). Functional cloning and characterization of the multidrug efflux pumps NorM from Neisseria gonorrhoeae and YdhE from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 3052–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rouquette-Loughlin C, Dunham SA, Kuhn M, Balthazar JT & Shafer WM (2003). The NorM efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis recognizes antimicrobial cationic compounds. J Bacteriol 185, 1101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Begum A, Rahman MM, Ogawa W, Mizushima T, Kuroda T & Tsuchiya T (2005). Gene cloning and characterization of four MATE family multidrug efflux pumps from Vibrio cholerae non-O1. Microbiol Immunol 49, 949–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saier MH Jr., Reddy VS, Tsu BV, Ahmed MS, Li C & Moreno-Hagelsieb G (2016). The Transporter Classification Database (TCDB): recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Edgar RC (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 1792–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]