Abstract

Three previously undescribed diketomorpholine natural products, along with the known phenalenones, herqueinone and norherqueinone, were isolated from the mycoparasitic fungal strain G1071, which was identified as a Penicillium sp. in the section Sclerotiora. The structures were established by analyzing NMR data and mass spectrometry fragmentation patterns. The absolute configurations of deacetyl-javanicunine A, javanicunine C, and javanicunine D, were assigned by examining ECD spectra and Marfey’s analysis. The structural diversity generated by this fungal strain was interesting, as only a few diketomorpholines (~17) have been reported from nature.

Keywords: Penicillium, Pyrrolidinoindoline, Diketomorpholine, Javanicunine, Phenalenones

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Pyrrolidinoindolines are a family of alkaloids isolated from fungi and plants (Li et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2009). These specialised metabolites have been shown to exhibit a variety of biological properties, including anti-inflammatory (Lin et al., 2009), P-glycoprotein inhibition (Khalil et al., 2014; Raju et al., 2011), plant growth regulation (de Montaigu et al., 2017; Kusano et al., 1998), and cytotoxicity (Wang et al., 1998). While the pyrrolidinoindolines include those with both diketopiperazine and diketomorpholine moieties, the majority are made up of the former. Diketopiperazines are usually derived from two amino acids, which can vary to give structural diversity to this class of compounds (Borthwick, 2012). For instance, Trp and Leu were reported as key building blocks in fructigenine B and brevicompanine B (Arai et al., 1989; Kusano et al., 1998), Trp and Pro in verruculogen and brevianamide F (Afiyatullov et al., 2004; Ben Ameur Mehdi et al., 2009), and Phe and His in phenylahistin (Kanoh et al., 1997). Moreover, diketopiperazines have served as the inspiration for clinical drugs, such as tadalafil for erectile dysfunction (Daugan et al., 2003), retosiban for preterm labor (Borthwick and Liddle, 2011), and aplaviroc for human immunodeficiency viruses (Borthwick, 2012).

Compared to diketopiperazines, only a few diketomorpholines have been reported from nature. For example, the Dictionary of Natural Products reports > 1300 specialised metabolites with a diketopiperazine moiety, yet only 17 natural products have been reported in the diketomorpholine class. Diketomorpholines are usually derived from an amino acid that forms an amide and ester linkage with another α-hydroxy acid moiety (i.e., an amino acid analogue in which the amine group was replaced with a hydroxy group) (Berthet et al., 2017). A fungal artificial chromosomes and metabolomic scoring (FAC-MS) technology and stable isotope feeding experiments were utilized to identify the biosynthetic pathway of dioxomorpholines (Robey et al., 2018). As suggested for acu-dioxomorpholine, which is derived from Trp and Phe, the biosynthesis of dioxomorpholines involves transamination of the second amino acid, followed by reduction to produce an α-hydroxy acid. The condensation of this α-hydroxy acid with the first amino acid is facilitated by a nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene that features a new type of condensation domain proposed to use an unusual arginine active site for ester bond formation (Robey et al., 2018). Mollenines A and B were the first diketomorpholines to be isolated from a fungus, Eupenicillium molle (strain NRRL 13062), and they had moderate cytotoxic and antibacterial activities (Wang et al., 1998). These were followed by the discovery of javanicunine A and B from E. javanicum (Shou et al., 2006). More recently, P-glycoprotein inhibitory effects were reported in some diketomorpholines (Aparicio-Cuevas et al., 2017; Khalil et al., 2014). Due to our interest in exploring the chemical diversity of fungi, (El-Elimat et al., 2012; González-Medina et al., 2017; González-Medina et al., 2016), we were intrigued that the majority of these diketomorpholine analogues, 15 out of 17, were isolated from fungi.

2. Results and Discussion

In the course of examining fungi from freshwater habitats, which are an under investigated ecological niche of microorganisms for both taxonomic and chemical diversity (El-Elimat et al., 2021), a fungal culture was collected from submerged wood in a stream in Connecticut, USA. This sample [Penicillium sp. (strain G1071)] was flagged for further investigation, since dereplication did not yield any hits compared to an in-house database of over 625 fungal metabolites (El-Elimat et al., 2013; Paguigan et al., 2017). Interestingly, strain G1071 was isolated from a minute mushroom fruiting on submerged wood and should be considered an immigrant to freshwater (El-Elimat et al., 2021; Park, 1972; Shearer, 1993). Fungal strain G1071 was grown over two weeks on rice medium, and the extract was purified via flash chromatography and HPLC to yield compounds 1–3 and 5–6 (Fig. 1). The structures of 1–3 were determined by NMR spectroscopic data, and their absolute configurations were assigned by examining ECD spectra, in addition to acid hydrolysis and Marfey’s analysis. Compounds 5 and 6 were herqueinone and norherqueinone, respectively, based on agreement with characterization data in the literature (Nishikori et al., 2016; Quick et al., 1980). Compounds 1-3 were also tested in suite of biological assays, including those for cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, mu opioid receptor, and cathepsin K assays, but unfortunately, we could not ascribe biological activities to these interesting fungal metabolites.

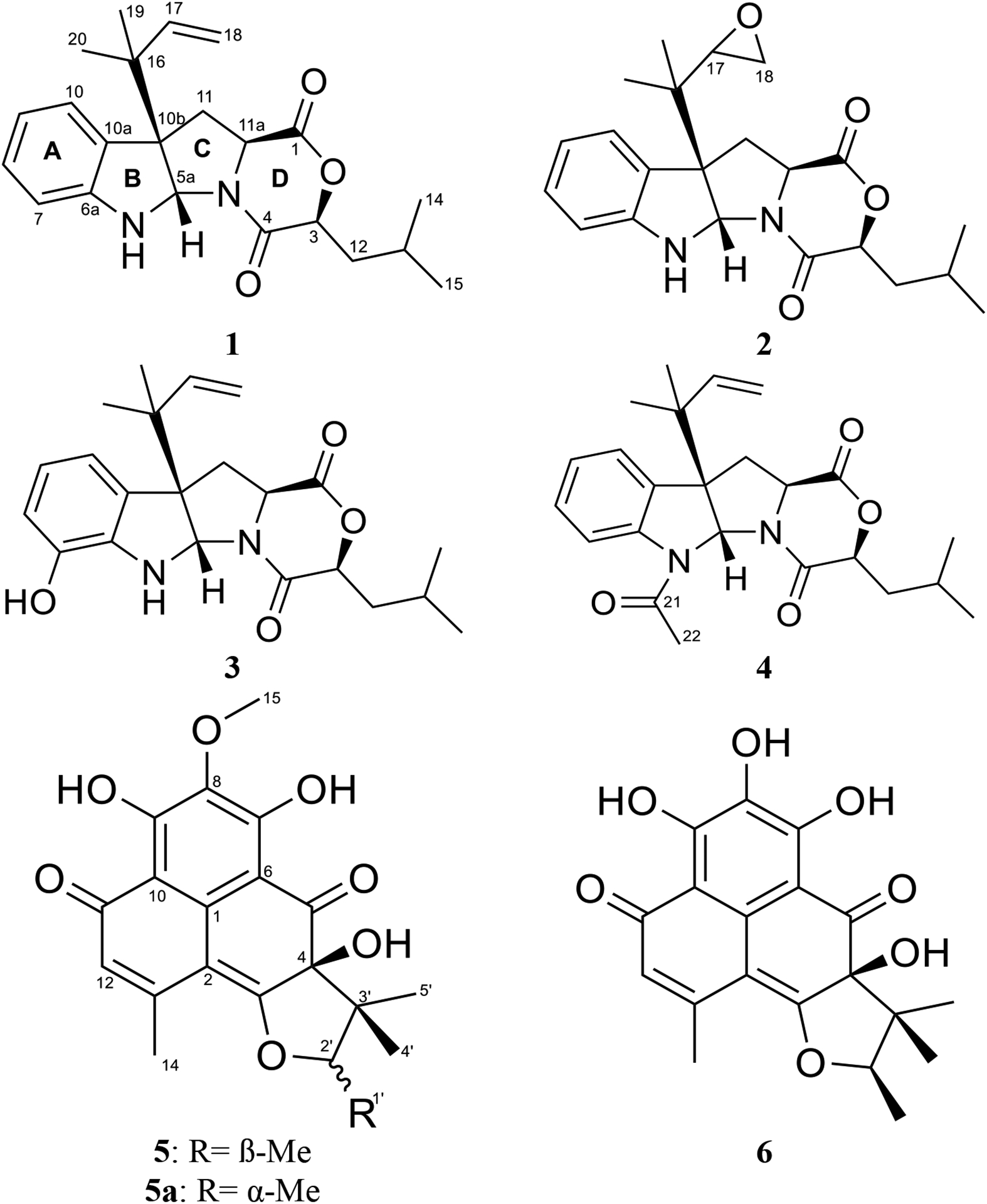

Fig. 1.

Structures of compounds 1–6.

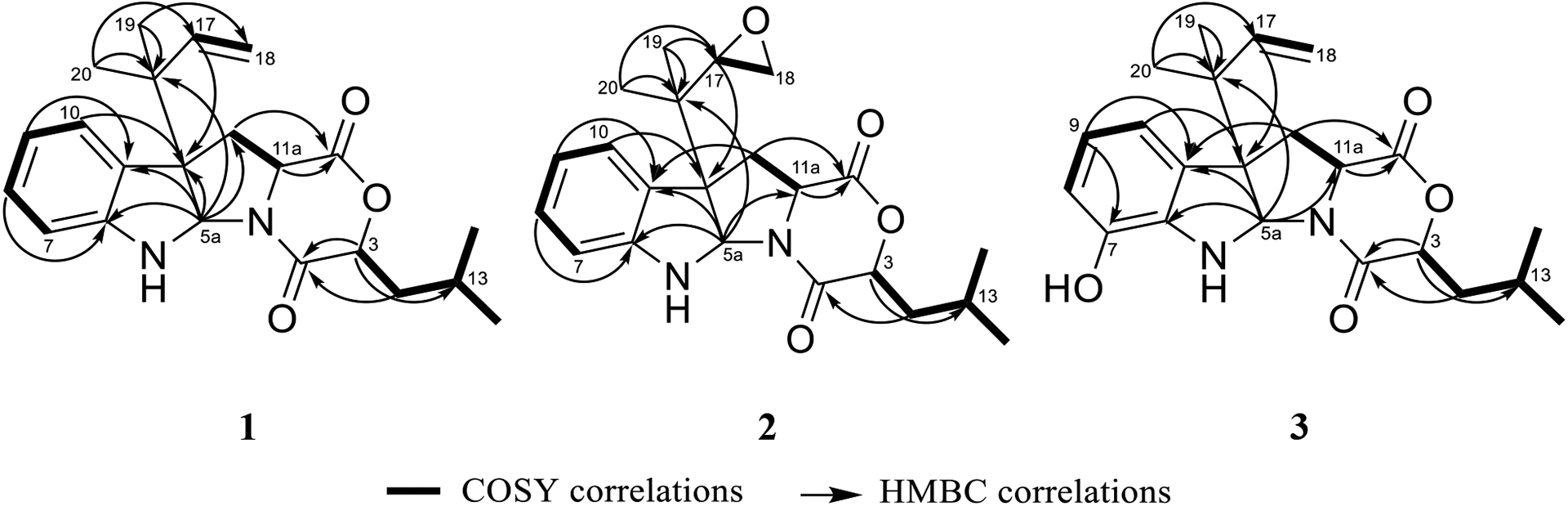

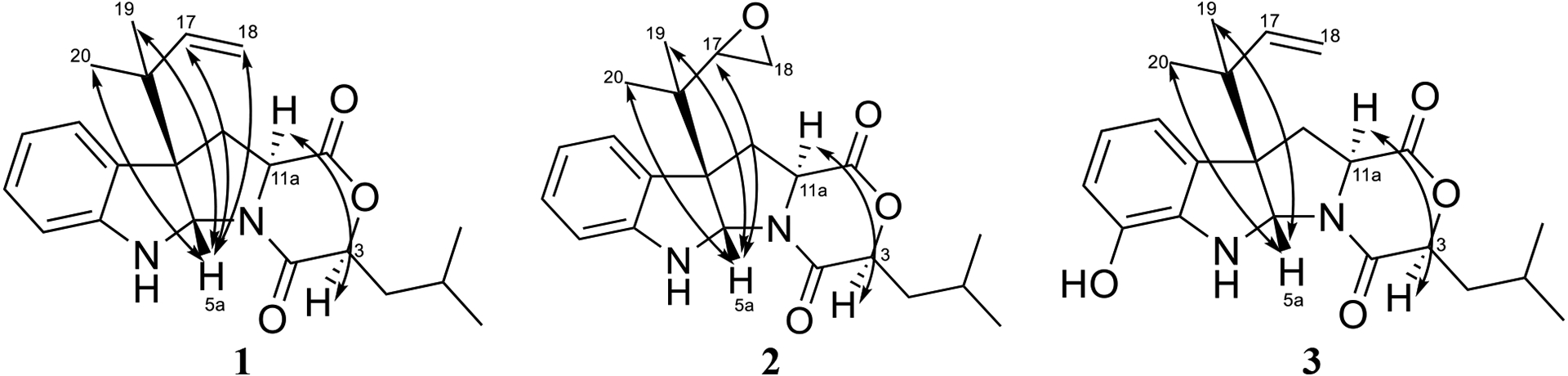

Compound 1 was obtained as a yellow oil with a molecular formula of C22H28N2O3 as deduced by HRESIMS (Fig. S1), indicating an index of hydrogen deficiency of 10. An examination of the 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1) indicated the presence of a disubstituted aromatic ring, a terminal double bond, two carbonyls, and four methyl groups. The tryptophan core was suggested by the COSY spin system from H-7 to H-10, the HMBC correlations of H-5a with C-6a, C-10a, C-10b, and C-11, and the HMBC correlations of H2-11 and H-11a with the C-1 carbonyl (Fig. 2). The 1,1-dimethyl-2-propenyl group attached to C-10b was confirmed by the HMBC correlations of H3-19 and H3-20 with C-16, C-17, and C-18. This side chain includes a characteristic terminal double bond and has been observed in various compounds with diketopiperazine and diketomorpholine moieties (Arai et al., 1989; Kusano et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2018), and our data corresponded well with the literature. A 2-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoate unit was suggested by the 1H-1H spin system from H-3 to H3-15, along with the HMBC correlation of H-3 with the C-4 carbonyl. This unit represents an α-hydroxy leucine-like moiety, where the amine group in Leu is replaced with a hydroxy. This α-hydroxy acid contributes to ring D by forming an ester linkage with the carboxylic acid of a Trp building block from one side and an amide linkage with the same Trp from the other side. Searching the literature for compounds with structural similarities showed that the NMR spectra of 1 matched those for the immediate synthetic precursor of javanicunine A (4), which was reported recently (Wang et al., 2019) (Table S1). Therefore, compound 1 is the deacetylated derivative of javanicunine A (4) and is reported for the first time as a fungal metabolite, which we have ascribed the trivial name, deacetyl-javanicunine A. NOESY cross peaks of H-5a with H3-19, H3-20, H-17, and H2-18 suggested the same orientation of the H-5a proton and the dimethyl-2-propenyl unit (Fig. 3). Additionally, NOESY correlations of H-3 with H-11a supported the co-facial orientation of these two protons (Fig. 3). Based on the match in the 1D and 2D NMR spectra (Table S1 and Figs. S2–S6), UV maxima, and specific rotation data (measured in CH2Cl2 [α]D20= −394 vs reported in CH2Cl2 [α]D20= −361) with those reported for the synthetic precursor of javanicunine A, the absolute configuration of 1 was assigned as 3S, 5aS, 10bR, 11aS (Wang et al., 2019) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR data in CDCl3 for 1 and CD3CN for 2 and 3.

| 1a | 2a | 3b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 169.0, C | 170.0, C | 170.1, C | |||

| 3 | 77.7, CH | 4.69, dd (10.0, 2.4) | 78.0, CH | 4.83, dd (9.9, 2.8) | 78.1, CH | 4.82, dd (9.8, 3.1) |

| 4 | 166.0, C | 166.3, C | 166.6, C | |||

| 5a | 77.9, CH | 5.48, s | 78.0, CH | 5.54, s | 78.6, CH | 5.45, s |

| 6 | 5.06, brs | 5.42, brs | 5.00, brs | |||

| 6a | 149.7, C | 151.4, C | 138.9, C | |||

| 7 | 109.7, CH | 6.59, d (7.7) | 110.5, CH | 6.65, d (7.8) | 142.6, C | |

| 8 | 129.3, CH | 7.12, t (8.0) | 129.8, CH | 7.11, t (7.6) | 120.6 or 116.1, CH | 6.66, d (4.2) |

| 9 | 119.2, CH | 6.78, t (7.5) | 119.5, CH | 6.76, t (7.5) | 117.8, CH | 6.81, t (4.3) |

| 10 | 125.1, CH | 7.17, d (7.5) | 126.1, CH | 7.26, d (7.5) | 116.1 or 120.6, CH | 6.66, d (4.3) |

| 10a | 128.8, C | 129.8, C | 131.9, C | |||

| 10b | 61.9, C | 62.5, C | 63.4, C | |||

| 11 | 36.2, CH2 | 2.56, m | 36.2, CH2 | 2.60, dd (12.8, 10.5) | 36.7, CH2 | 2.47, dd (12.8, 10.6) |

| 2.62, m | 2.65, dd (12.9, 7.1) | 2.54, dd (12.8, 6.8) | ||||

| 11a | 57.8, CH | 4.06, dd (10.3, 7.0) | 58.3, CH | 4.09, dd (10.3, 7.0) | 58.4, CH | 4.06, dd (10.6, 6.9) |

| 12 | 37.9, CH2 | 1.81, m | 38.4, CH2 | 1.66, ddd (13.6, 10.2, 3.5) | 38.4, CH2 | 1.66, ddd (14.2, 9.9, 4.3) |

| 1.93, m | 1.87, m | 1.87, m | ||||

| 13 | 24.1, CH | 1.91, m | 25.0, CH2 | 1.83, m | 25.0, CH | 1.83, m |

| 14 | 23.4, CH3 | 0.97, d (6.2) | 21.4, CH3 | 0.90, d (6.2) | 21.5, CH3 | 0.90, d (6.4) |

| 15 | 21.3, CH3 | 0.90, d (6.1) | 23.4, CH3 | 0.96, d (6.4) | 23.4, CH3 | 0.96, d (6.5) |

| 16 | 41.0, C | 38.9, C | 41.6, C | |||

| 17 | 143.3, CH | 5.96, dd (17.4, 10.8) | 56.5, CH | 2.94, t (3.5) | 145.2, CH | 6.06, dd (17.0, 11.2) |

| 18 | 115.0, CH2 | 5.09, d (17.4) | 43.8, CH2 | 2.45, m | 114.3, CH2 | 5.07, dd (17.0, 1.2) |

| 5.15, d (10.8) | 5.08, dd (11.0, 1.2) | |||||

| 19 | 22.9, CH3 | 1.00, s | 19.0, CH3 | 0.83, s | 23.3, CH3 | 0.97, s |

| 20 | 22.6, CH3 | 1.12, s | 19.5, CH3 | 0.93, s | 23.1, CH3 | 1.09, s |

Data collected at 400 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C).

Data collected at 700 MHz (1H) and 175 MHz (13C).

Fig. 2.

Key COSY and HMBC correlations of 1–3.

Fig. 3.

Key NOESY correlations of compounds 1–3.

To further confirm that 1 represented the deacetylated analogue of javanicunine A (4), acetylation of 1 at N-6 was performed to afford 4. The addition of the acetyl group was confirmed by the molecular formula of 4 (C24H30N2O4), as deduced by HRESIMS data (Fig. S7), and the new methyl (i.e., δH/δC 2.63/23.7) and carbonyl (i.e., δC 170.0) signals (Table S2 & Fig. S8). The NMR (Table S2) and specific rotation data (measured in CH2Cl2 [α]D20= −196 vs reported in CH2Cl2 [α]D20= −152) of 4 matched those reported for javanicunine A (Shou et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2019). The absolute configuration of 4 was determined previously by acid hydrolysis, which showed that 4 was derived from L-tryptophan (L-Trp) (Shou et al., 2006), further supporting the 3S, 5aS, 10bR, 11aS assignment of 1.

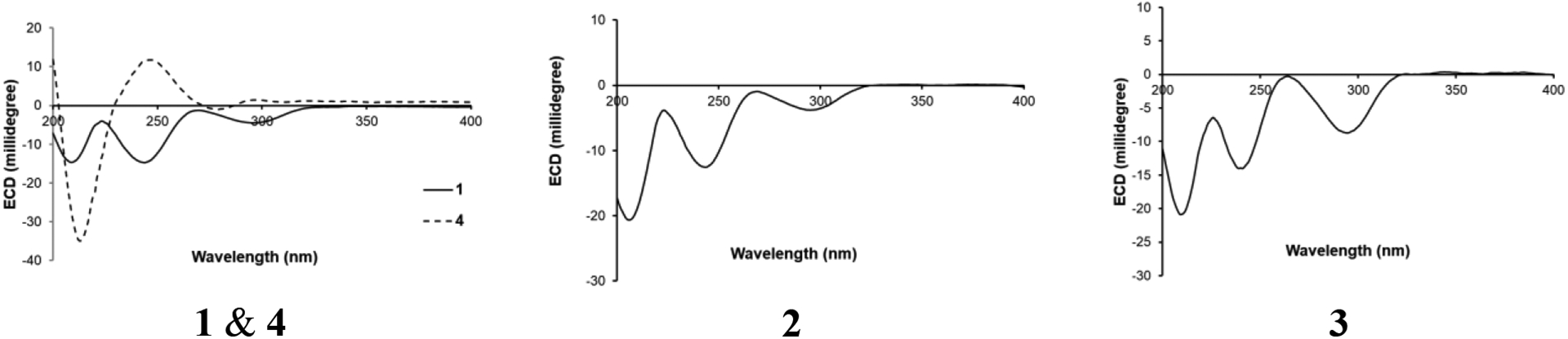

Finally, the ECD spectra of 1 and 4 revealed an interesting observation. Specifically, the ECD of 1 exhibited a negative Cotton effect at 245 nm, while the N-acetylated derivative (4) exhibited a positive Cotton effect at this range of wavelengths (Fig. 4). Similar behavior was reported previously for diketopiperazines and their N-acetylated derivatives with the same absolute configurations at the B-C ring junction (i.e. positions 5a and 10b), position C-3, and position C-11a as compounds 1 and 4 (Arai et al., 1989; Hino et al., 1981; Takase et al., 1985). This further confirmed the absolute configuration of these two compounds as 3S, 5aS, 10bR, 11aS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

ECD spectra of compounds 1–4 in CH3CN.

The molecular formula of compound 2 was identified as C22H28N2O4 as deduced by HRESIMS (Fig. S9). 1H and 13C NMR data suggested structural similarity with 1 (Table 1), however, compound 2 was missing the three olefinic protons at C-17 and C-18, indicating a loss of the terminal double bond. The two new sets of signals (i.e. δH/δC 2.94/56.5 and δH/δC 2.45/43.8) for positions C-17 and C-18, respectively, suggested the presence of an oxirane ring. The fact that compounds 1 and 2 shared the same index of hydrogen deficiency supported this conclusion. The position of the oxirane ring was confirmed by the HMBC correlations of H-17 with C-10b, C-19, and C-20 carbons (Fig. 2). Therefore, compound 2 differed from 1 by having a 2-isopropyloxirane side chain attached to C-10b instead of the 1,1-dimethyl-2-propenyl group. The NOESY spectrum of 2 suggested a similar relative configuration as that observed in 1 (Fig. 3), where H-5a correlated with H3-19 and H3-20, while H-3 correlated with H-11a. Due to free rotation, the configuration of the oxirane ring could not be defined despite the observed NOESY cross peak between H-17 and H-5a. The ECD spectrum of 2 was nearly identical to that for 1, suggesting the same configuration for positions 3, 5a, 10b, and 11a in 1 and 2 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, acid hydrolysis and Marfey’s analysis of 2 revealed the presence of L-Trp, also in accord with the data for compounds 1 and 4 (Figs. S15–S17) (Shou et al., 2006). Accordingly, compound 2 has the absolute configuration of 3S, 5aS, 10bS, and 11aS, and was named as javanicunine C (Fig. 1).

As determined by the HRESIMS data (Fig. S18), compound 3 shared the same molecular formula as 2 (C22H28N2O4). However, 3 maintained the terminal double bond between C-17 and C-18, as noted by the two sets of signals (i.e. δH/δC 6.06/145.2 and δH/δC 5.07 & 5.08/114.3) for positions C-17 and C-18, respectively. Unlike 1 and 2, the NMR data of 3 (Table 1) showed only three aromatic protons in the indole core, suggesting hydroxylation of this aromatic ring, which was supported by the deshielded carbon at δC 142.6 (C-7). The position of the hydroxy group was assigned based on the -CH-CH-CH- proton spin system observed from H-8 to H-10, along with the HMBC correlations of H-9 with C-7, and H-10 with C-10b. As with 1 and 2, the NOESY spectrum of 3 showed correlations of H-5a with H3-19 and H3-20, while H-3 correlated with H-11a (Fig. 3). The similar ECD spectra (Fig. 4) and specific rotation of 1 and 3 ([α]D20= −356 for 1 in CH3CN and −345 for 3 in CH3CN) suggested that 3 represented the 7-hydroxy analogue of 1 with an absolute configuration of 3S, 5aS, 10bR, 11aS (Fig. 1). Compound 3 was assigned the name javanicunine D. Interestingly, compound 3 was structurally similar to javanicunine B, where they share the same molecular formula (Shou et al., 2006). However, javanicunine B has the hydroxy group attached to C-11a.

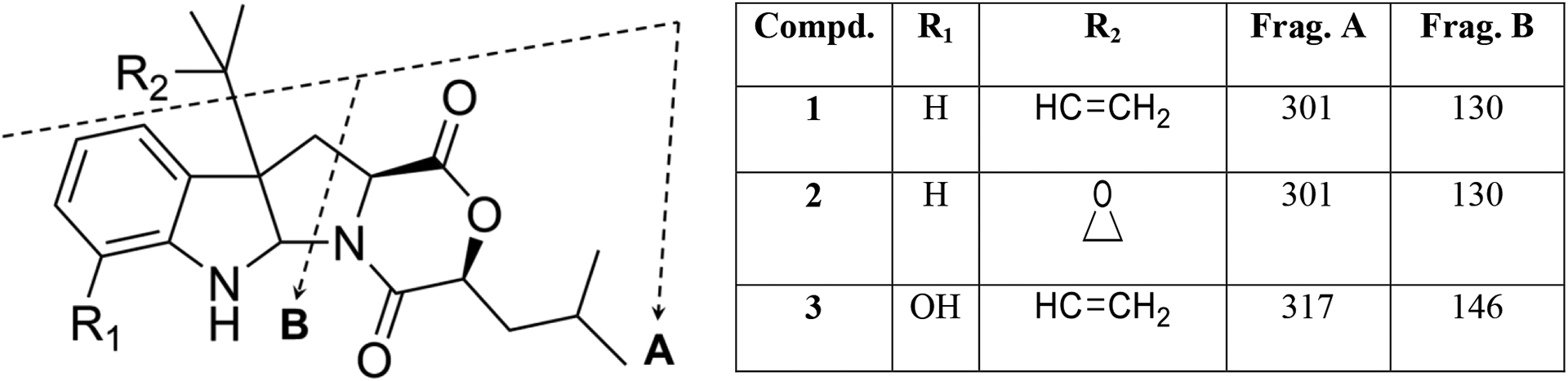

The structures of 1–3 were also supported by their HRESIMS fragmentation patterns (Fig. S24). Fragment A, which represents the loss of the side chain attached to C-10b, was the same in compounds 1 and 2 (m/z 301) (Fig. 5), which confirmed the presence of the epoxide group in place of the terminal double bond in 2. On the other hand, fragment A was 16 Da higher in 3 (m/z 317), supporting the presence of the same dimethyl-2-propenyl side chain attached to C-10b as in 1. The presence of the hydroxy group attached to the indoline ring of 3 was supported by its m/z for fragment B (m/z 146), which is 16 units higher than that for 1 and 2.

Fig. 5.

(+)-HRESIMS fragmentation patterns of 1–3.

Based on the identified biosynthesis pathway of acu-dioxomorpholine (Robey et al., 2018), compounds 1–3 likely derive from Trp and Leu. Transamination of Leu to replace the amino group with a ketone, followed by reduction to an alcohol via NAD(P)H-dependent reductase, allows for the conversion of the Leu to α-hydroxy leucine. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene that features a new type of condensation domain, as reported for acu-dioxomorpholine, could be responsible for condensation of Trp with α-hydroxy leucine.

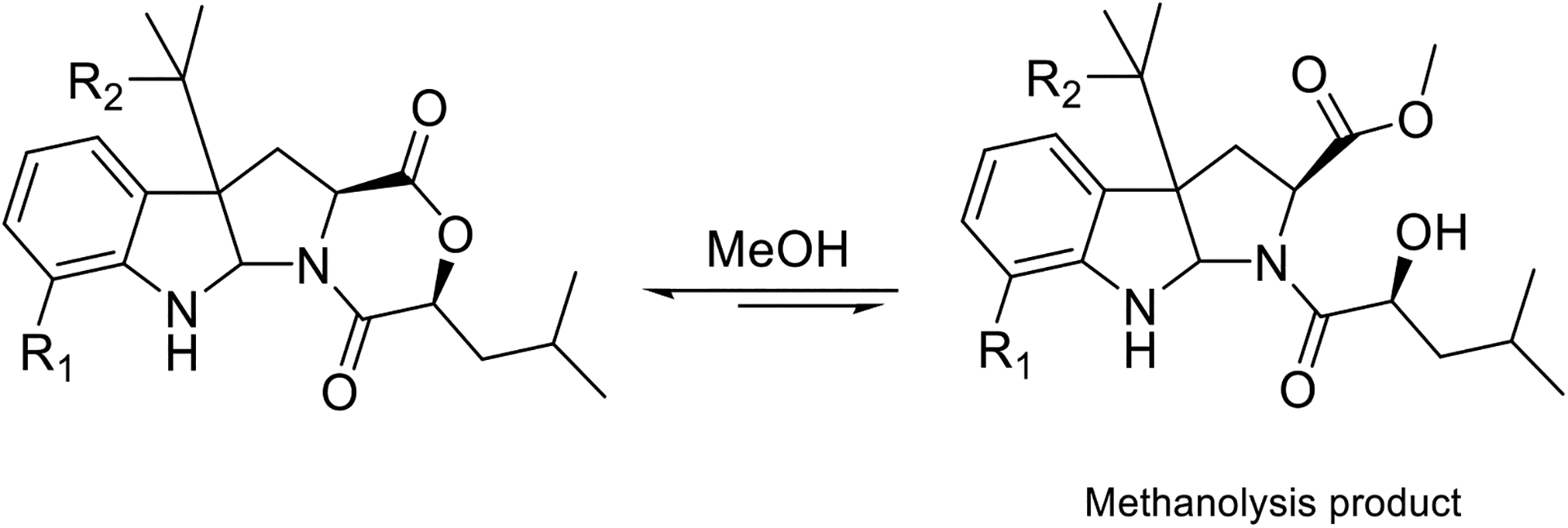

It is well established that some natural products are chemically reactive and prone to transformation by environmental stimuli, such as pH, temperature, light, air, or solvent exposure, and understanding of the possible transformations that could be induced is important to differentiate between natural products and their possible artifacts (Capon, 2020; Khalil et al., 2014). Solvolysis was suggested previously for several diketomorpholines after exposure to protic solvents (e.g., MeOH or EtOH) (Khalil et al., 2014; Wang et al., 1998). To investigate this, MeOH solutions of 1–4 were prepared at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL and subjected to UPLC-HRESIMS after 48 h. An ion peak corresponding to [M + H] + + MeOH was obtained for each compound (Fig. S25), suggesting an opening of ring D and formation of a methyl ester (Fig. 6). Although Khalil et al. suggested that solvolytically unstable diketomorpholines can be stabilized by the alkylation of N-5 (Khalil et al., 2014), compounds 1–4 are all N-alkylated diketomorpholines and are still susceptible to partial solvolysis. Interestingly, while we could generate these artifacts by treating the isolated fungal metabolites, none of the methanolysis products were isolated from the original extract despite the use of MeOH in the extraction process. It is possible that in the context of the multicomponent extract, with only limited exposure to methanol, and with the N-alkylation noted by Kalil et al. (Khalil et al., 2014) that such methanolysis reactions are minimized.

Fig. 6.

Proposed methanolysis products of 1–4. The R1 and R2 groups for compounds 1–4 are as noted in Fig. 5.

Compound 5 was the major constituent of the fungal extract and was identified as herqueinone by comparing its MS and NMR data (Figs. S26 and S27) with those reported in the literature (Nishikori et al., 2016; Quick et al., 1980). Epimerization of herqueinone to produce a mixture of herqueinone (5)/isoherqueinone (5a) was also observed (Fig. S28), and this phenomenon was reported previously for herqueinone (Cason et al., 1970). Compound 6 was identified as a desmethoxylated derivative of 5 by examining its HRESIMS spectrum and 1D, and 2D NMR data (Figs. S29–S30). The 1D structure of 6 matched those reported for norherqueinone and its epimer, isonorherqueinone (Quick et al., 1980). However, the specific rotation of 6 (measured in pyridine [α]D20= +847) allowed its identification as norherqueinone (reported in pyridine [α]D20= +1080) rather than isonorherqueinone (reported in pyridine [α]D20= −730) (Galarraga et al., 1955). As the NMR data of norherqueinone (6) have never been published, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 6 are reported in the supporting information (Fig. S30). Both 5 and 6 belong to the phenalenone family. Various Penicillium species in section Sclerotiora had been reported to produce phenalenones, such as P. herquei strain PSU-RSPG93 and strain P14190 (Nishikori et al., 2016; Tansakul et al., 2014).

The biological activity of these fungal metabolites (1–3) were elusive, as they were neither cytotoxic against a panel of cancer cell lines (IC50 > 25 μM, Table S3) nor antimicrobial against a broad series of pathogenic microorganisms (MIC > 60 μg/mL, Table S4). Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of these compounds were measured by broth microdilution against various pathogenic microorganisms as outlined in Table S4. STarFish, which is a computational target fishing model for natural products, was utilized to identify possible protein targets for 1–4 (Cockroft et al., 2019). The Mu-type opioid receptor for 1 and cathepsin K for 1, 2, and 4 were suggested by STarFish as possible targets for these compounds (score range between 0.06–0.1). pain management and the bone resorption process, respectively. Unfortunately, testing of compounds 1–3 against cAMP accumulation assay and compounds 2, 3, 5, and 6 for cathepsin K inhibition showed negative results.

3. Conclusion

This project expanded the natural diketomorpholines family with the identification of three undescribed fungal metabolites. The structures and absolute configurations of 1–3 were determined by examining 1D and 2D NMR data, mass spectrometry fragmentation patterns, ECD spectra, and Marfey’s analysis. Despite testing against a suite of cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, protease and second messenger assays, we were unable to ascribe biological properties for these structurally interesting fungal metabolites. Given the preponderance of diketopiperazines reported in the literature, and the relative lack of diketomorpholines from nature, further studies to probe and compare the biosynthesis of these metabolites seems warranted.

4. Experimental

4.1. General experimental procedure

Optical rotation data were collected using a Rudolph Research Autopol III polarimeter (Rudolph Research Analytical). ECD and UV spectra were measured using an Olis DSM 17 ECD spectrophotometer (Olis, Inc.) and a Varian Cary 100 Bio UV‒ Vis spectrophotometer (Varian Inc.), respectively. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded in either CDCl3 or CD3CN using an Agilent 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe, a JEOL ECA‒500 spectrometer, or a JEOL ECS-400 spectrometer equipped with a high sensitivity JEOL Royal probe and a 24-slot autosampler. Residual solvent signals were used for referencing the NMR spectra. UPLC-HRESIMS data were collected via an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometry system (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA) connected to a Waters Acquity UPLC system. A BEH Shield RP C18 column (Waters, 1.7 μm; 50 × 2.1 mm) heated to 40 °C was used. The mobile phase consisted of CH3CN-H2O (0.1% formic acid) in a gradient system of 15:85 to 100:0 over 10 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. MS data were collected from m/z 150 to 2000 in the positive mode. All analytical and preparative HPLC experiments were carried out using a Varian Prostar HPLC system equipped with ProStar 210 pumps and a Prostar 335 photodiode array detector (PDA). HPLC data were collected and analyzed using Galaxie Chromatography Workstation software (version 1.9.3.2, Varian Inc.). For preparative HPLC, an Atlantis T3 column (Waters, 5 μm; 250 × 19 mm) was used. Flash chromatography was carried out using a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash Rf 200 that was equipped with both UV and evaporative light‒scattering detectors and using Silica Gold columns (from Teledyne Isco).

4.2. Fungal strain isolation and identification

Strain G1071 was isolated from a minute mushroom fruiting body, which was growing out of submerged wood collected in January 2019 from a freshwater stream in Hebron, Connecticut (N41 41.26776, W72 26.52564). Placing the entire mushroom fruiting body on antibiotic water agar (AWA, agar 20 g, streptomycin sulfate 250 mg/L, penicillin G 250 mg/L, distilled water 1L; antibiotics were added to the molten agar immediately after autoclaving) followed by incubating the Petri plate at room temperature encouraged growth of fungal hyphae. A small portion of hyphae along with the agar was excised and placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco) to obtain a pure culture of strain G1071. The fungus produced a yellow to yellow-green to light olivaceous green colony with a dark yellow-green reverse within 14 days when incubated at 25 °C. Morphological characteristics of the fungal strain on PDA indicated the strain could be identified as a Penicillium sp. (Visagie et al., 2014).

For molecular identification, the ITS rDNA region was amplified to confirm whether the fungus belongs to the genus Penicillium; this was accomplished with the primer combination ITS1F and ITS4 (Gardes et al., 1991; Innis et al., 2014) using DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing methods outlined previously (Raja et al., 2017). In addition, to obtain more specific information about species level identification by Maximum Likelihood analysis using RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006) run on the CIPRES server (Miller et al., 2010), the second largest (RPB2) subunit of RNA polymerase was studied using the primer combination RPB2–5f and RPB2–7Cr (Liu et al., 1999). The RPB2 region was utilized, since it is an important secondary marker utilized for phylogenetic analysis of Penicillium spp. (Visagie et al., 2014). The RPB2 region has the added advantage of lacking introns in the amplicon, which permits constructing robust and easy alignments when used for phylogenetic analysis (Visagie et al., 2014).

Based on BLAST searches of the ITS region with both the RefSeq database (Schoch et al., 2014) as well as with pairwise sequence identification from CBS Database - Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute – KNAW, strain G1071 showed ≥ 99% sequence similarity with Penicillium sp. including P. herquei. Similar results were obtained upon a BLAST search using RPB2. Since P. herquei is a member of the section Sclerotiora, (Visagie et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017) all species showing high sequence homology with strain G1071 based on the RPB2 region were downloaded and aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) analysis showed that strain G1071 was nested in a unique clade with strong ML bootstrap support (100%), and was related to P. herquei, P. verrucisporum, and P. choerospondiatis with ≥ 98% bootstrap support (Fig. S31). Based on the morphology of the culture, BLAST search results, and ML analysis, we identify strain G1071 as belonging to Penicillium sp. in the section Sclerotiora, Aspergillaceae, Eurotiomycetes, Ascomycota. Additional micromorphological and molecular phylogenetic analysis using CaM, BenA and RPB2 data are warranted to verify if strain G1071 might be a novel species. From an ecological perspective, strain G1071 is not truly a freshwater species because Penicillium spp. are ubiquitous fast-growing molds that do not have adaptations to live and reproduce in fresh water, but rather occur fortuitously in aquatic habitats (El-Elimat et al., 2021). The sequences obtained in this study were deposited in GenBank (ITS: MW341222; RPB2:MW349119, MW349120).

4.3. Fermentation, extraction, and isolation

A culture of strain G1071 was maintained on a malt extract slant and was transferred periodically. A fresh culture was grown on PDA media, subsequently; an agar plug from the PDA culture was transferred to a sterile falcon tube with 10 ml of YESD (2% soy peptone, 2% dextrose, and 1% yeast extract). The YESD cultures were grown for 7 days on an orbital shaker (100 rpm) at room temperature (~23°C) and then used to inoculate five small-scale flasks of solid fermentation media. Each solid-state fermentation was prepared in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask using 10 g of autoclaved rice that was moistened with 20 mL of deionized water. The cultures were then incubated at room temperature for two weeks.

To each small-scale solid fermentation culture of G1071, 60 mL of 1:1 MeOH:CHCl3 was added. The cultures were chopped with a spatula and shaken for 12 h at 100 rpm at rt. followed by vacuum filtration. The filtrate from the five small-scale cultures were combined, and then 900 mL of CHCl3 and 1000 mL of deionized water were added and stirred for 30 min before being transferred to a separatory funnel. The bottom layer was drawn off and evaporated to dryness. The dried organic extract was re-constituted in 500 mL of 1:1 MeOH:CH3CN and 500 mL hexanes. The biphasic solution was shaken vigorously and then transferred to a separatory funnel. The MeOH:CH3CN layer was separated and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. This defatted extract material (490 mg) was dissolved in CHCl3, adsorbed onto Celite 545, and fractionated into four fractions via normal-phase flash chromatography using a gradient solvent system of hexanes-CHCl3-MeOH at a 30 mL/min flow rate and 80 column volumes over 45 min. The first fraction from the flash chromatography was subjected to a preparative reverse-phase HPLC separation (Atlantis T3) using an isocratic system of 60:40 CH3CN-H2O (0.1% formic acid) for 35 min at a flow rate of 17.0 mL/min to yield five subfractions. Subfractions 1, 2, and 5 were identified as compounds 2 (3.9 mg), 3 (1.0 mg), and 1 (4.0 mg), respectively. The third fraction from the flash chromatography was subjected to a preparative reverse-phase HPLC separation (Atlantis T3) using an isocratic system of 50:50 CH3CN-H2O (0.1% formic acid) for 45 min at a flow rate of 17.0 mL/min to afford compounds 5 (85.0 mg) and 6 (3.5 mg).

Deacetyl-javanicunine A (1): Yellow oil; [α]D20= −356 (c = 0.1, CH3CN); UV (CH3CN) λmax (log ε) 298 (3.4), 243 (3.8), 206 (4.5) nm. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) (see Table 1); HRESIMS m/z 369.2173 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C22H29N2O3, 369.2172).

Javanicunine C (2): Yellow oil; [α]D20= −346 (c = 0.1, CH3CN); UV (CH3CN) λmax (log ε) 298 (3.4), 242 (3.8), 205 (4.4) nm. 1H NMR (CD3CN, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3CN, 100 MHz) (see Table 1); HRESIMS m/z 385.2130 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C22H29N2O4, 385.2121).

Javanicunine D (3): Yellow oil; [α]D20= −345 (c = 0.1, CH3CN); UV (CH3CN) λmax (log ε) 295 (3.4), 212 (4.5) nm. 1H NMR (CD3CN, 700 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3CN, 176 MHz) (see Table 1); HRESIMS m/z 385.2119 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C22H29N2O4, 385.2121).

Javanicunine A (4): Colorless amorphous solid; [α]D20= −196 (c = 0.1, CH 12Cl2). H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) (see Table S2); HRESIMS m/z 411.2263 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C24H31N2O4, 411.2278).

Herqueinone (5) and isoherqueinone (5a): Orange amorphous powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) (see Fig. S27 and S28); HRESIMS m/z 373.1275 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C20H21O7, 373.1281).

Norherqueinone (6): Orange amorphous powder; [α]D20= +847 (c = 0.1, pyridine). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) (see Fig. S30); HRESIMS m/z 359.1120 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C19H19O7, 359.1125).

4.4. Acetylation of deacetyl-javanicunine A (1)

Acetylation of compound 1 was carried out as described previously (Wang et al., 2019). In brief, 2.5 mg of 1 were dissolved in 500 μL of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). Then, 150 μL of acetic anhydride was added gradually. The reaction mixture was kept at 60 °C for 15 hrs. The mixture was evaporated to dryness and then subjected to semi-preparative HPLC over a Phenomenex PFP column using a gradient system of 50:50 to 60:40 of CH3CN-H2O (0.1% formic acid) over 15 min at a flow rate of 4.72 mL/min to yield 1.0 mg of javanicunine A (4).

4.5. Acid hydrolysis and Marfey’s analysis of Javanicunine C (2)

Acid hydrolysis and Marfey’s analysis were performed according to Helaly et al. (Helaly et al., 2018) and Capon et al. (Capon et al., 2003) with slight modification. Briefly, 500 μL of 6 M HCl was added to 1.5 mg of javanicunine C (2). The resulting solution was kept in a sealed vial after being flushed with nitrogen and left stirring at 110 °C for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then neutralized with 500 μL of 6 M NaOH and allowed to dry completely. The resulting sample was subjected to UPLC-HRMS to confirm the production of Trp (Fig. S15–S16). For the Marfey’s analysis, the hydrolysate mixture was re-dissolved in deionized water (250 μL) before adding 100 μL of sodium bicarbonate (1 M) and 500 μL of 1-fluoro-2-4-dinitrophenyl-5- L-alanine amide (L-FDAA) (1% in acetone). The resulting solution was kept stirring at 37 °C for 1 h and then neutralized with 100 μL of 1 M HCl. Similarly, L-Trp and D-Trp were dissolved in water and treated with L-FDAA as described for the acid hydrolysate to afford L-FDAA standards. UPLC-HRMS analysis of the Marfey’s derivatives of compound 2, L-Trp, and D-Trp was performed using an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer connected to a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Fig. S17).

4.6. Cytotoxicity and Antimicrobial Assays

To evaluate the cytotoxic activity of 1–3 against human melanoma cancer cells (MDA-MB-435), human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), and human ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR3), the previously described protocol was followed (Al Subeh et al., 2021). In brief, a total of 5,000 cells were seeded per well of a 96-well clear, flat-bottom plate (Microtest 96, Falcon) and incubated overnight (37 °C in 5% CO2). Samples dissolved in DMSO were then diluted and added to the appropriate wells. The cells were incubated in the presence of test substance for 72 h at 37 °C and evaluated for viability with a commercial absorbance assay.

Testing for antibacterial and antifungal activities included tests against Gram-negative Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and Bacillus anthracis, and the fungi Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus niger. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of compounds 1–3 were measured by broth microdilution antimicrobial assays. The antimicrobial assay protocol is previously described (Ayers et al., 2012).

4.7. STarFish Analysis.

The full details for how to use STarFish to probe the potential biological activity of a compound have been detailed recently (Cockroft et al., 2019), and these directions were followed to upload the compounds into the software and analyze for potential activities (Software download link: https://github.com/ntcockroft/STarFish).

4.8. cAMP Accumulation Assay

The cAMP Hunter eXpress OPRM1 CHO-K1 GPCR assay (Eurofins DiscoveRx Corporation) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 100 μL cell plating reagent in 96 well plates and allowed to incubate at 37 °C (5% CO2, 95% relative humidity) for 24 hr. Media was removed from cells, and cells were washed with 30 μL of cell assay buffer. Compounds 1–3 were assessed using an 11 point 5-fold serial dilution with a starting concentration of 10 mM. Aliquots of compound/forskolin solution were added to cells (final concentrations were 20 μM forskolin, and 0.4% DMSO) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 min. Next, cAMP antibody reagent detection solution was added to each well according to manufacturer’s instructions at room temperature protected from light for one hr. Next, enzyme acceptor solution was added, and the solution allowed to incubate at RT protected from light overnight. Luminescence was quantified using an iD5 multimode microplate reader plate reader with SoftMax® Pro software (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Data were normalized to vehicle and forskolin only control values and analyzed using three parameter nonlinear regression with GraphPad Prism 8.0.

4.9. Screening for Cathepsin K Inhibition

Cathepsin K Inhibitor Screening kit (Sigma, #MAK-201K) was purchased and used to investigate cathepsin K inhibitory activity of compounds 2, 3, 5, and 6. Fluorescence (FLU, λex= 400/λem= 505nm) was quantified using a iD5 multimode microplate reader plate reader in kinetic mode for 60 minutes at 37 °C (SoftMax® Pro software; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Data were normalized to Enzyme Control values and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Deacetyl-javanicunine A, javanicunine C, and D were isolated from a Penicillium sp.

Few diketomorpholines have been described, demonstrating the chemical diversity of fungi.

The structures of 1–3 were elucidated by 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy and MS fragmentation patterns.

The absolute configurations of 1–3 were defined by examining ECD spectra and Marfey’s analysis.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute/NIH via grant P01 CA125066. This work was performed in part at the Joint School of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering, a member of the Southeastern Nanotechnology Infrastructure Corridor (SENIC) and National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-1542174). From UNCG, we thank Mitch Croatt, Tyler Graf, and Manuel Rangel-Grimaldo for helpful suggestions and Heather Winter for collecting samples of submerged wood, which led to the isolation of strain G1071.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

1H NMR, 13C NMR and (+)-HRESIMS data for compounds 1–6, 2D NMR data (HSQC, COSY, and HMBC) for the new compounds (1–3), MS fragmentation patterns of 1–3, UPLC chromatograms of Marfey’s derivatives, UPLC-HRESIMS chromatograms of 1–4 after exposure to methanol, and phylograms of the most likely tree. The 1D and 2D NMR spectra for 1–6 were deposited in Harvard Dataverse and can be freely accessed through https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8KHOMC.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Afiyatullov SS, Kalinovskii AI, Pivkin MV, Dmitrenok PS, Kuznetsova TA, 2004. Fumitremorgins from the marine isolate of the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Chem. Nat. Compd 40, 615–617. DOI: 10.1007/s10600-005-0058-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Subeh ZY, Raja HA, Maldonado A, Burdette JE, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2021. Thielavins: tuned biosynthesis and LR-HSQMBC for structure elucidation. J. Antibiot 74, 300–306. DOI: 10.1038/s41429-021-00405-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Cuevas MA, Rivero-Cruz I, Sánchez-Castellanos M, Menéndez D, Raja HA, Joseph-Nathan P, González M. d. C., Figueroa M, 2017. Dioxomorpholines and derivatives from a marine-facultative Aspergillus species. J. Nat. Prod 80, 2311–2318. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, Kimura K, Mushiroda T, Yamamoto Y, 1989. Structures of fructigenines A and B, new alkaloids isolated from Penicillium fructigenum Takeuchi. Chem. Pharm. Bull 37, 2937–2939. DOI: 10.1248/cpb.37.2937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S, Ehrmann BM, Adcock AF, Kroll DJ, Carcache de Blanco EJ, Shen Q, Swanson SM, Falkinham JO 3rd, Wani MC, Mitchell SM, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2012. Peptaibols from two unidentified fungi of the order Hypocreales with cytotoxic, antibiotic, and anthelmintic activities. J. Pept. Sci 18, 500–510. DOI: 10.1002/psc.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ameur Mehdi R, Shaaban KA, Rebai IK, Smaoui S, Bejar S, Mellouli L, 2009. Five naturally bioactive molecules including two rhamnopyranoside derivatives isolated from the Streptomyces sp. strain TN58. J. Nat. Prod 23, 1095–1107. DOI: 10.1080/14786410802362352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet M, Legrand B, Martinez J, Parrot I, 2017. A general approach to the aza-diketomorpholine scaffold. Org. Lett 19, 492–495. DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick AD, 2012. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: synthesis, reactions, medicinal chemistry, and bioactive natural products. Chem. Rev 112, 3641–3716. DOI: 10.1021/cr200398y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick AD, Liddle J, 2011. The design of orally bioavailable 2,−5-diketopiperazine oxytocin antagonists: from concept to clinical candidate for premature labor. Med. Res. Rev 31, 576–604. DOI: 10.1002/med.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capon RJ, 2020. Extracting value: mechanistic insights into the formation of natural product artifacts case studies in marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep 37, 55–79. DOI: 10.1039/C9NP00013E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capon RJ, Skene C, Stewart M, Ford J, O’Hair RAJ, Williams L, Lacey E, Gill JH, Heiland K, Friedel T, 2003. Aspergillicins A-E: five novel depsipeptides from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus carneus. Org. Biomol. Chem 1, 1856–1862. DOI: 10.1039/b302306k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cason J, Koch CW, Correia JS, 1970. Structures of herqueinone, isoherqueinone and norherqueinone. J. Org. Chem 35, 179–186. DOI: 10.1021/jo00826a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cockroft NT, Cheng X, Fuchs JR, 2019. STarFish: A stacked ensemble target fishing approach and its application to natural products. J. Chem. Inf. Model 59, 4906–4920. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugan A, Grondin P, Ruault C, Le Monnier de Gouville AC, Coste H, Linget JM, Kirilovsky J, Hyafil F, Labaudiniere R, 2003. The discovery of tadalafil: a novel and highly selective PDE5 inhibitor. 2: 2,3,6,7,12,12a-hexahydropyrazino(1’,2’:1,6)pyrido(3,4-b)indole-1,4-- dione analogues. J. Med. Chem 46, 4533. DOI: 10.1021/jm0300577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montaigu A, Oeljeklaus J, Krahn JH, Suliman MNS, Halder V, de Ansorena E, Nickel S, Schlicht M, Plíhal O, Kubiasová K, Radová L, Kracher B, Tóth R, Kaschani F, Coupland G, Kombrink E, Kaiser M, 2017. The root growth-regulating brevicompanine natural products modulate the plant circadian clock. ACS Chem. Biol 12, 1466–1471. DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC, 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Elimat T, Figueroa M, Ehrmann BM, Cech NB, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2013. A high-resolution MS, MS/MS, and UV database of fungal secondary metabolites as a dereplication protocol for bioactive natural products. J. Nat. Prod 76, 1709–1716. DOI: 10.1021/np4004307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Elimat T, Raja HA, Figueroa M, Al Sharie AH, Bunch RL, Oberlies NH, 2021. Freshwater Fungi as a Source of Chemical Diversity: A Review. J. Nat. Prod 84, 898–916. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c01340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Elimat T, Zhang X, Jarjoura D, Moy FJ, Orjala J, Kinghorn AD, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2012. Chemical diversity of metabolites from fungi, cyanobacteria, and plants relative to FDA-approved anticancer agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 3, 645–649. DOI: 10.1021/ml300105s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarraga JA, Neill KG, Raistrick H, 1955. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms. The colouring matters of Penicillium herquei Bainier & Sartory. Biochem. J 61, 456–464. DOI: 10.1042/bj0610456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, White TJ, Fortin JA, Bruns TD, Taylor JW, 1991. Identification of indigenous and introduced symbiotic fungi in ectomycorrhizae by amplification of nuclear and mitochondrial ribosomal DNA. Can. J. Bot 69, 180–190. DOI: 10.1139/b91-026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Medina M, Owen JR, El-Elimat T, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, Figueroa M, Medina-Franco JL, 2017. Scaffold diversity of fungal metabolites. Front. Pharmacol 8. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Medina M, Prieto-Martínez FD, Naveja JJ, Méndez-Lucio O, El-Elimat T, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, Figueroa M, Medina-Franco JL, 2016. Chemoinformatic expedition of the chemical space of fungal products. Future Med. Chem 8, 1399–1412. DOI: 10.4155/fmc-2016-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helaly SE, Teponno RB, Bernecker S, Stadler M, Helaly SE, Ashrafi S, Maier W, Teponno RB, Dababat AA, 2018. Nematicidal cyclic lipodepsipeptides and a xanthocillin derivative from a phaeosphariaceous fungus parasitizing eggs of the plant parasitic nematode Heterodera filipjevi. J. Nat. Prod 81, 2228–2234. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino T, Taniguchi M, Yamamoto I, Yannaguchi K, Nakagawa M, 1981. Cyclic tautomers of tryptamines and tryptophans. V. Formation and reactions of cyclic tautomers of cyclo-L-tryptophanyl-L-proline. Tetrahedron Lett. 22, 2565–2568. DOI: 10.1021/ja00485a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, 2014. PCR Protocols : a Guide to Methods and Applications. Elsevier Science, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh K, Kohno S, Asari T, Harada T, Katada J, Muramatsu M, Kawashima H, Sekiya H, Uno I, 1997. (−)-Phenylahistin: a new mammalian cell cycle inhibitor produced by Aspergillus ustus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 7, 2847–2852. DOI: 10.1016/S0960-894X(97)10104-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil ZG, Huang X. c., Raju R, Piggott AM, Capon RJ, 2014. Shornephine A: structure, chemical stability, and P-glycoprotein inhibitory properties of a rare diketomorpholine from an Australian marine-derived Aspergillus sp. J. Org. Chem 79, 8700–8705. DOI: 10.1021/jo501501z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano M, Sotoma G, Koshino H, Uzawa J, 1998. Brevicompanines A and B: new plant growth regulators produced by the fungus, Penicillium brevicompactum. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans I, 2823–2826. DOI: 10.1039/A803880E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sun KL, Wang Y, Fu P, Liu PP, Wang C, Zhu WM, 2013. A cytotoxic pyrrolidinoindoline diketopiperazine dimer from the algal fungus Eurotium herbariorum HT-2. Chin. Chem. Lett 24, 1049–1052. DOI: 10.1016/j.cclet.2013.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Xinying Y, Tianjiao Z, 2009. Diketopiperazine alkaloids from a deep ocean sediment derived fungus Penicillium sp. Chem. Pharm. Bull 57, 873–876. DOI: 10.1038/ja.2010.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Whelen S, Hall BD, 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol 16, 1799–1808. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T, 2010. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of large phylogenetic trees. In Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikori S, Takemoto K, Kamisuki S, Nakajima S, Kuramochi K, Tsukuda S, Iwamoto M, Katayama Y, Suzuki T, Kobayashi S, Watashi K, Sugawara F, 2016. Anti-hepatitis C virus natural product from a fungus, Penicillium herquei. J. Nat. Prod 79, 442–446. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paguigan ND, El-Elimat T, Kao D, Raja HA, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2017. Enhanced dereplication of fungal cultures via use of mass defect filtering. J. Antibiot 70, 553–561. DOI: 10.1038/ja.2016.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, 1972. On the ecology of heterotrophic micro-organisms in fresh-water. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc 58, 291–299. DOI: 10.1016/S0007-1536(72)80157-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quick A, Thomas R, Williams DJ, 1980. X-Ray crystal structure and absolute configuration of the fungal phenalenone herqueinone. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun, 1051–1053. DOI: 10.1039/C39800001051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Miller AN, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH, 2017. Fungal identification using molecular tools: a primer for the natural products research community. J. Nat. Prod 80, 756–770. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju R, Piggott AM, Huang X-C, Capon RJ, 2011. Nocardioazines: a novel bridged diketopiperazine scaffold from a marine-derived bacterium Inhibits P-glycoprotein. Org. Lett 13, 2770–2773. DOI: 10.1021/ol200904v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey MT, Ye R, Bok JW, Clevenger KD, Islam MN, Chen C, Gupta R, Swyers M, Wu E, Gao P, Thomas PM, Wu CC, Keller NP, Kelleher NL, 2018. Identification of the first diketomorpholine biosynthetic pathway using FAC-MS technology. ACS Chem. Biol 13, 1142–1147. DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Robbertse B, Robert V, Vu D, Cardinali G, Irinyi L, Meyer W, Nilsson RH, Hughes K, Miller AN, Kirk PM, Abarenkov K, Aime MC, Ariyawansa HA, Bidartondo M, Boekhout T, Buyck B, Cai Q, Chen J, Crespo A, Crous PW, Damm U, De Beer ZW, Dentinger BTM, Divakar PK, Dueñas M, Feau N, Fliegerova K, García MA, Ge Z-W, Griffith GW, Groenewald JZ, Groenewald M, Grube M, Gryzenhout M, Gueidan C, Guo L, Hambleton S, Hamelin R, Hansen K, Hofstetter V, Hong S-B, Houbraken J, Hyde KD, Inderbitzin P, Johnston PR, Karunarathna SC, Kõljalg U, Kovács GM, Kraichak E, Krizsan K, Kurtzman CP, Larsson K-H, Leavitt S, Letcher PM, Liimatainen K, Liu J-K, Lodge DJ, Luangsa-ard JJ, Lumbsch HT, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Manamgoda D, Martín MP, Minnis AM, Moncalvo J-M, Mulè G, Nakasone KK, Niskanen T, Olariaga I, Papp T, Petkovits T, Pino-Bodas R, Powell MJ, Raja HA, Redecker D, Sarmiento-Ramirez JM, Seifert KA, Shrestha B, Stenroos S, Stielow B, Suh S-O, Tanaka K, Tedersoo L, Telleria MT, Udayanga D, Untereiner WA, Diéguez Uribeondo J, Subbarao KV, Vágvölgyi C, Visagie C, Voigt K, Walker DM, Weir BS, Weiß M, Wijayawardene NN, Wingfield MJ, Xu JP, Yang ZL, Zhang N, Zhuang W-Y, Federhen S, 2014. Finding needles in haystacks: linking scientific names, reference specimens and molecular data for Fungi. Database (Oxford) 2014, bau061. DOI: 10.1093/database/bau061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CA, 1993. The freshwater Ascomycetes. Nova Hedwigia 56, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shou N, Koohei N, Hitoshi H, Nakadate S, Nozawa K, Horie H, 2006. New dioxomorpholine derivatives, javanicunine A and B, from Eupenicillium javanicum. Heterocycles 68, 1969–1972. DOI: 10.1002/chin.200704199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase S, Kawai Y, Uchida I, Tanaka H, Aoki H, 1985. Structure of amauromine, a new hypotensive vasodilator produced by Amauroascus sp. Tetrahedron 41, 3037–3048. DOI: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96656-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tansakul C, Rukachaisirikul V, Maha A, Kongprapan T, Phongpaichit S, Hutadilok-Towatana N, Borwornwiriyapan K, Sakayaroj J, 2014. A new phenalenone derivative from the soil fungus Penicillium herquei PSU-RSPG93. Nat. Prod. Res 28, 1718–1724. DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2014.941363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visagie CM, Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Hong SB, Klaassen CHW, Perrone G, Seifert KA, Varga J, Yaguchi T, Samson RA, 2014. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol 78, 343–371. DOI: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visagie CM, Houbraken J, Rodriques C, Silva Pereira C, Dijksterhuis J, Seifert KA, Jacobs K, Samson RA, 2013. Five new Penicillium species in section Sclerotiora: a tribute to the Dutch Royal family. Persoonia 31, 42–62. DOI: 10.3767/003158513X667410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HJ, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF, 1998. Mollenines A and B: new dioxomorpholines from the ascostromata of Eupenicillium molle. J. Nat. Prod 61, 804–807. DOI: 10.1021/np9704056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MZ, Si TX, Ku CF, Zhang HJ, Li ZM, Chan ASC, 2019. Synthesis of javanicunines A and B, 9-deoxy-PF1233s A and B, and absolute configuration establishment of javanicunine B. J. Org. Chem 84, 831–839. DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X-C, Chen K, Zeng Z-Q, Zhuang W-Y, 2017. Phylogeny and morphological analyses of Penicillium section Sclerotiora (Fungi) lead to the discovery of five new species. Sci. Rep 7, 1–14. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-08697-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-H, Long C-L, Yang F-M, Wang X, Sun Q-Y, Wang H-S, Shi Y-N, Tang G-H, 2009. Pyrrolidinoindoline alkaloids from Selaginella moellendorfii. J. Nat. Prod 72, 1151–1154. DOI: 10.1021/np9001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SQ, Li XM, Li X, Chi LP, Wang BG, 2018. Two new diketomorpholine derivatives and a new highly conjugated ergostane-type steroid from the marine algal-derived endophytic fungus Aspergillus alabamensis EN-547. Mar. Drugs 16, 114. DOI: 10.3390/md16040114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.