Abstract

Neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusions are rare oncogenic drivers in solid tumours. This study aimed to interrogate a large real-world database of comprehensive genomic profiling data to describe the genomic landscape and prevalence of NTRK gene fusions. NTRK fusion-positive tumours were identified from the FoundationCORE® database of >295,000 cancer patients. We investigated the prevalence and concomitant genomic landscape of NTRK fusions, predicted patient ancestry and compared the FoundationCORE cohort with entrectinib clinical trial cohorts (ALKA-372-001 [EudraCT 2012-000148-88]; STARTRK-1 [NCT02097810]; STARTRK-2 [NCT02568267]). Overall NTRK fusion-positive tumour prevalence was 0.30% among 45 cancers with 88 unique fusion partner pairs, of which 66% were previously unreported. Across all cases, prevalence was 0.28% and 1.34% in patients aged ≥18 and <18 years, respectively; prevalence was highest in patients <5 years (2.28%). The highest prevalence of NTRK fusions was observed in salivary gland tumours (2.62%). Presence of NTRK gene fusions did not correlate with other clinically actionable biomarkers; there was no co-occurrence with known oncogenic drivers in breast, or colorectal cancer (CRC). However, in CRC, NTRK fusion-positivity was associated with spontaneous microsatellite instability (MSI); in this MSI CRC subset, mutual exclusivity with BRAF mutations was observed. NTRK fusion-positive tumour types had similar frequencies in FoundationCORE and entrectinib clinical trials. NTRK gene fusion prevalence varied greatly by age, cancer type and histology. Interrogating large datasets drives better understanding of the characteristics of very rare molecular subgroups of cancer and allows identification of genomic patterns and previously unreported fusion partners not evident in smaller datasets.

Subject terms: Cancer, Oncogenes

Introduction

The neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) genes 1/2/3 encode tropomyosin receptor kinases (TRK) A/B/C respectively. Inter-chromosomal rearrangements causing NTRK gene fusions can result in constitutive activation of TRK proteins, which then act as oncogenic drivers through activation of cellular growth pathways1–3. NTRK gene fusions occur in ~0.3% of all solid tumours, though frequencies vary by cancer type4–6. Their prevalence is >90% in rare cancers such as secretory breast carcinoma and mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland (MASC)7,8.

Small molecule TRK inhibitors (entrectinib and larotrectinib) are clinically active in NTRK fusion-positive tumours9,10. Retrospective analysis of data from >26,000 patients from a prospective genomic screening programme at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC, NY, USA) investigated the incidence, distribution and genomic context of NTRK gene fusions across cancers6. They were found in 0.28% of cases and NTRK fusion-positive tumours were largely devoid of other oncogenic drivers.

We aimed to expand these findings by analysing data from >295,000 cancer patients from the FoundationCORE® database (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) to investigate NTRK gene fusions prevalence, co-occurrence with relevant biomarkers/oncogenic drivers, associated fusion partners and cancer types/histologies. Additionally, NTRK fusion-positive cases in the FoundationCORE database were compared with those enrolled in three phase I/II entrectinib clinical trials9 (ALKA-372-001 [EudraCT 2012-000148-88], STARTRK-1 [NCT02097810], STARTRK-2 [NCT02568267]), to determine if the study cohorts were representative of the real-world population.

Results

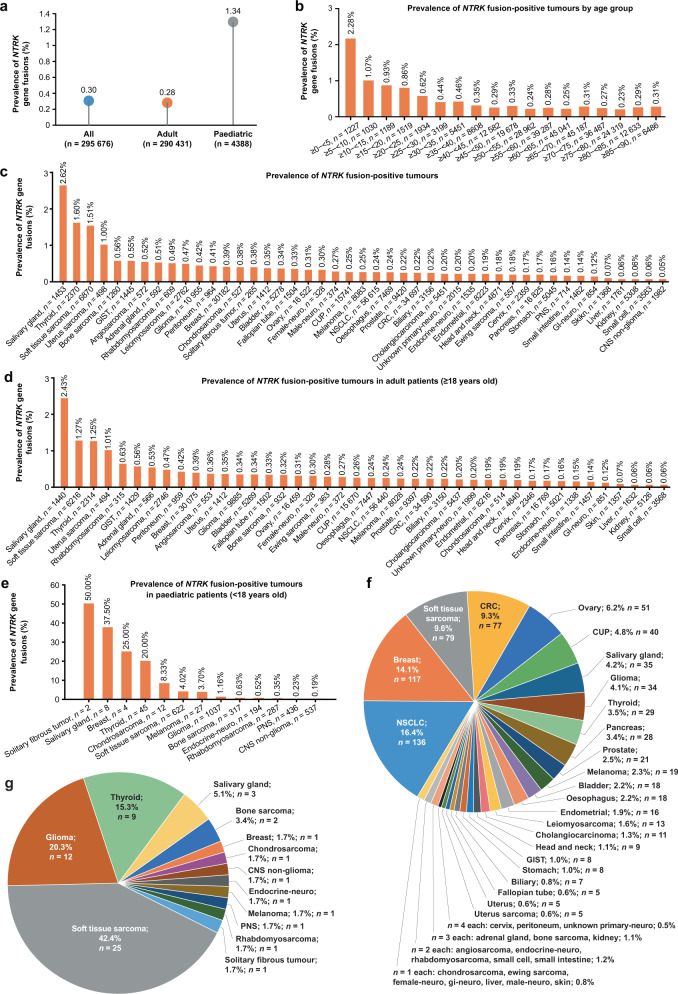

Solid tumour NTRK gene fusion prevalence in the FoundationCORE database

From 295,676 patients, NTRK gene fusions were found in 889 (prevalence = 0.30%, Fig. 1a). Demographics are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The 889 NTRK fusion-positive cases included 134 distinct histological subtypes from 45 cancer types (Supplementary Table 2). NTRK fusion-positive tumours prevalence varied by age and cancer type (Fig. 1a–e); it was 0.28% in adults (aged ≥18 years) and 1.34% in paediatric patients (aged <18 years; Fig. 1a). Prevalence increased with decreasing age, with children <5 years demonstrating the highest incidence of 2.28% (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 3); largely as a result of NTRK fusion-positive soft tissue fibrosarcoma (1.06%, n = 13/1227 of all patients <5 years), not found in other age groups (Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 1. Prevalence of NTRK fusion-positive specimens in FoundationCORE by indication and age group.

The prevalence of NTRK gene fusions overall and among adult (aged ≥18 years) and paediatric patients (aged <18 years; (a). The prevalence of NTRK gene fusions by age group (b). The prevalence of NTRK gene fusions by cancer type among: all patients (c), adult patients (d) and paediatric patients (e), with n numbers representing the total number of patients analysed per tumour type. Prevalence analysis of cancer types among all NTRK fusion-positive tumours in adults (f) and paediatric patients (g), where numbers represent the total number of patients with each cancer type. CNS central nervous system, CRC colorectal carcinoma, CUP unknown primary carcinoma, GI gastrointestinal, GIST gastrointestinal stromal tumour, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase, PNS peripheral nervous system.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with NTRK fusion-positive tumours in FoundationCORE.

| All (N = 889)a | Adults (≥18 years, n = 827) | Children (<18 years, n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 60.5 (0–89) | 62 (18–89) | 5 (0–17) |

| Female, n (%) | 511 (57.5) | 481 (58.2) | 28 (47.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 378 (42.5) | 346 (41.8) | 31 (52.5) |

| Specimen location, n (%) | |||

| Local | 338 (38.0) | 315 (38.1) | 23 (39.0) |

| Metastatic: lymph node | 87 (9.8) | 85 (10.3) | 2 (3.4) |

| Metastatic: non-lymph node | 198 (22.3) | 196 (23.7) | 2 (3.4) |

| Unknown | 266 (29.9) | 231 (27.9) | 32 (54.2) |

NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

aThe total number does not equal the sum of adults and children because three patients were of unknown age.

In adults, prevalence of NTRK fusion-positive cancers was highest in salivary gland cancers (2.43%, n = 35/1440), soft tissue sarcomas (1.27%, n = 79/6216) and thyroid cancers (1.25%, n = 29/2314; Fig. 1d). Among the paediatric cohort, prevalence was highest in solitary fibrous tumours (50%, n = 1/2), salivary gland cancers (37.50%, n = 3/8), breast tumours (25%, n = 1/4) and thyroid tumours (20%, n = 9/45), although total numbers were low, as these paediatric cancers are rare (Fig. 1e). NTRK gene fusion prevalence was further investigated by tumour histology (Supplementary Table 2): prevalence was highest in MASC (71.43%, n = 10/14), unknown primary myoepithelial carcinoma (14.29%, n = 1/7) and soft tissue fibrosarcoma (11.76%, n = 16/136).

All NTRK fusion-positive tumours were analysed by cancer type and frequency for adult (Fig. 1f) and paediatric patients (Fig. 1g). The most common adult cancer types (and most common associated histologies; Supplementary Table 2) were non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC; n = 136, of which 95 were adenocarcinoma), breast (n = 117, of which 71 were breast carcinoma not otherwise specified [NOS] and 42 were invasive ductal carcinoma), soft tissue sarcoma (n = 79, of which 37 were sarcoma NOS and 13 were liposarcoma) and CRC (n = 77, of which 73 were colon adenocarcinoma). Among paediatric patients the most common were soft tissue sarcoma (n = 25, of which 13 were fibrosarcoma and 6 were sarcoma NOS), glioma (n = 12, of which 3 were brain astrocytoma pilocytic, 3 were glioma NOS and 3 were glioblastoma) and thyroid (n = 9, all papillary carcinoma). An in silico analysis estimating differences in sensitivity between DNA- and RNA-based NGS assays suggested that, although DNA-based assays may not capture all NTRK fusions, the detection rates were nonetheless very high (91% vs. 100%) (Supplementary Table 5). The predicted detection rate for the DNA assay matches closely with those reported in the analytic validation of FoundationOne® CDx (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) for the detection of NTRK fusions11. Reduced detection rates for QKI:NTRK2 and ETV6:NTRK3 variants II and IV were attributed to limited intronic baiting of NTRK2 and ETV6 by FoundationOne CDx.

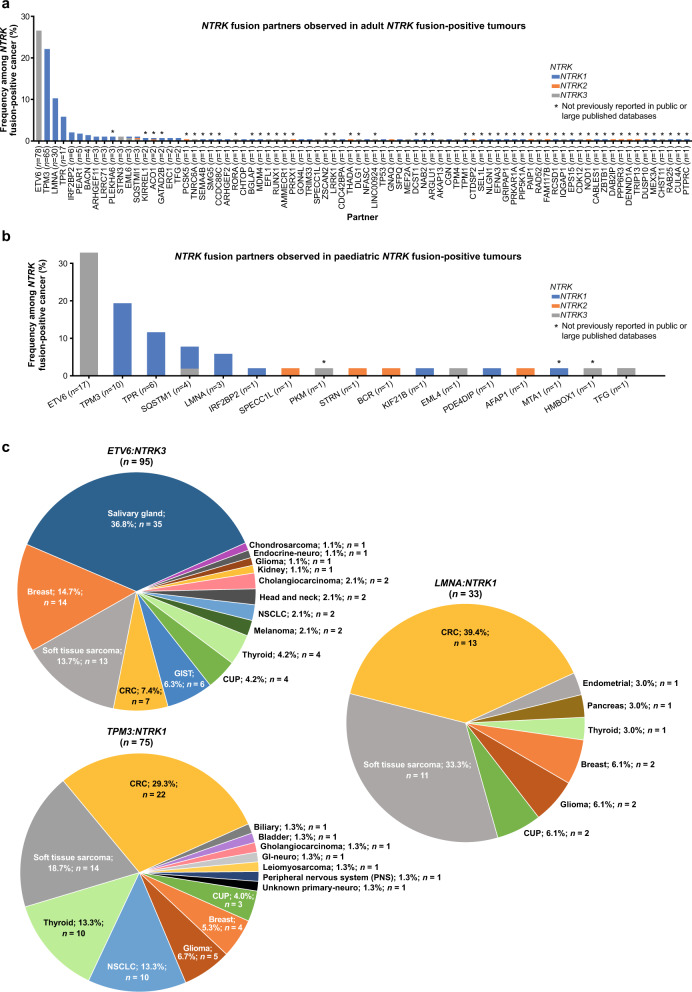

Spectrum of NTRK gene fusion partners detected in solid tumours

Eighty-eight unique fusion partner pairs were identified, of which 65.9% (n = 58/88) were not previously reported in other large public databases/studies4–6,8,9,12,13 (Fig. 2a and b; Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). ETV6:NTRK3 was most common in adults (26.4%, n = 78/295 [total cases with known fusion partners]) and paediatric patients (32.7%, n = 17/52 [total cases with known fusion partners]). From all cases with known fusion partners, ETV6:NTRK3 (27.2%, n = 95/349), TPM3:NTRK1 (21.5%, n = 75/349) and LMNA:NTRK1 (9.5%, n = 33/349) were the most common. The most common tumour type with ETV6 was salivary gland (36.8%), with TPM3 was CRC (29.3%) and with LMNA was CRC (39.4%; Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. The spectrum of NTRK fusion partners detected among NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours.

Breakdown of NTRK gene fusions detected among adult (a) and paediatric patients (b) and the disease breakdown of the three most frequently observed NTRK fusion partners (c). CRC colorectal carcinoma, CUP unknown primary carcinoma, GI gastrointestinal, GIST gastrointestinal stromal tumour, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

Prevalence of NTRK gene fusions by predicted ancestry

Prevalence of NTRK fusions was marginally higher in patients with primarily Asian (East and South Asian) ancestry (0.40%) compared with Central/South American (0.37%), African (0.34%) or European (0.28%) ancestry (odds ratio = 1.36; P < 0.017; Supplementary Fig. 1). Supplementary Table 8 summarises tumour types by ancestry. NSCLC made up 24% of the East Asian total population but was only 13–20% in other ancestries. Central/South American ancestry was enriched for NTRK fusion-positive soft tissue sarcoma (24% versus 10–13% in other ancestries).

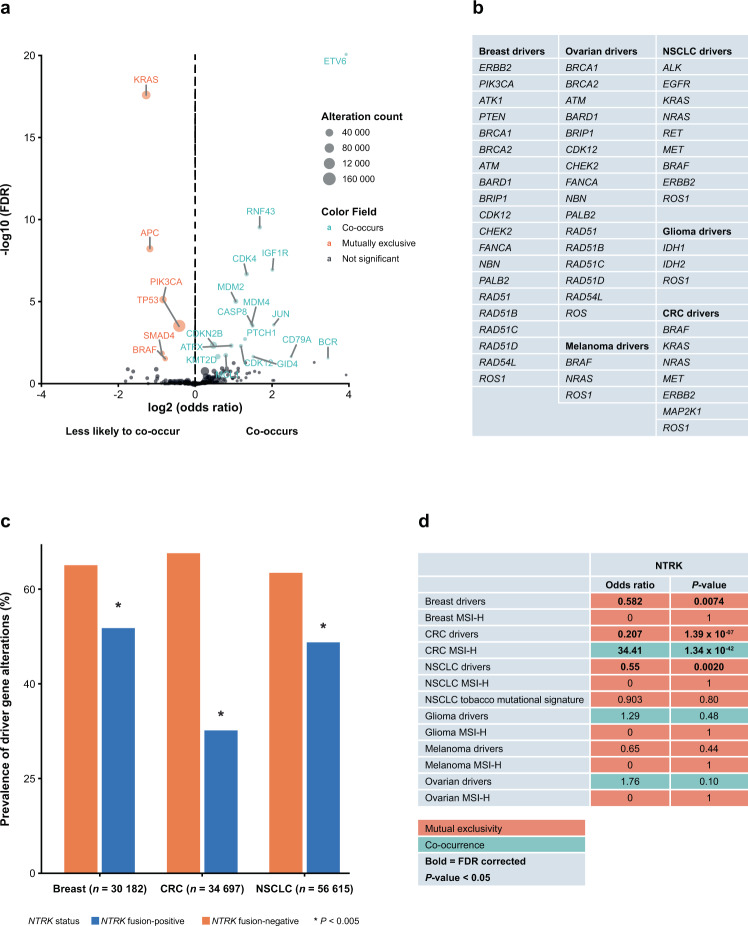

Co-alteration patterns of NTRK gene fusions with cancer-related genes

Across all solid tumours, NTRK gene fusions were less likely to co-occur with mutations in KRAS, APC, TP53 and PIK3CA (P < 0.01; Fig. 3a). There was significant co-occurrence of NTRK gene fusions with alterations in 14 genes, including ETV6, RNF43, IGF1R, CDKN2B and CDK4 (Fig. 3a). Co-occurrence with ETV6 correlated with it being the most common fusion partner. No enrichment was seen with alterations in other clinically relevant biomarkers such as EGFR, ERBB2, RET, ALK or MET. Supplementary Table 9 summarises results for all genes tested for co-occurrence, providing insight into the genomic landscape of NTRK gene fusion-positive cancers.

Fig. 3. Co-occurrence of genes among NTRK fusion-positive cancers.

Co-occurrence of genes in all NTRK fusion-positive cancers (a). The prevalence of gene mutations was compared for NTRK fusion-positive and fusion-negative disease. Co-occurrence refers to genes that occurred in NTRK fusion-positive disease with an odds ratio greater than 1 compared with NTRK fusion-negative disease and the false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P-value was <0.05. Lack of co-occurrence refers to genes that did not occur in NTRK fusion-positive disease with an odds ratio less than 1 compared with NTRK fusion-negative disease and the FDR-adjusted P-value was <0.05. List of known disease-specific driver genes for different tumour types (b). The frequency of mutations found within driver genes listed in b in NTRK fusion-positive and NTRK fusion-negative colorectal cancer (CRC), breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; c). Summary of co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity of driver gene mutations and microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status with specific NTRK fusion-positive cancers (d). NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

Co-alteration patterns of NTRK gene fusions with altered driver genes in select tumour types

Analysis of NTRK gene fusions and known oncogenic driver genes (Fig. 3b) for breast, ovarian, melanoma, NSCLC, glioma and CRC showed NTRK gene fusions were mutually exclusive with alterations in disease-specific driver genes in breast, CRC and NSCLC (P < 0.01; Fig. 3c, d; Supplementary Tables 10 and 11) and trended toward mutual exclusivity in melanoma (Fig. 3d). Importantly, there was no mutual exclusivity based on the presence of a tobacco trinucleotide mutational signature in NSCLC (Fig. 3d). Likewise, median tumour mutational burden (TMB) was similar in NTRK fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumours, including those in NSCLC, but was increased in NTRK fusion-positive CRC (Supplementary materials; Supplementary Fig. 2).

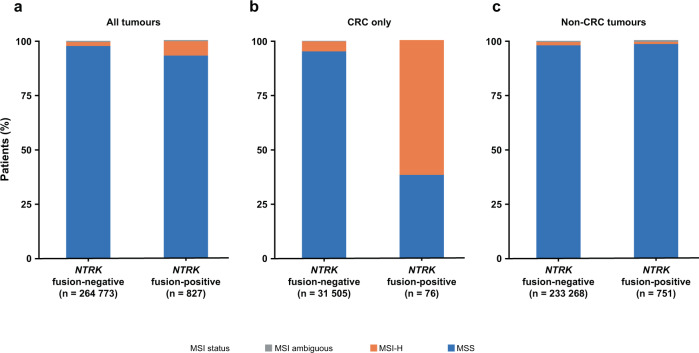

Evaluation of microsatellite instability (MSI) status in NTRK fusion-positive versus NTRK fusion-negative tumours

We investigated the association of MSI status and NTRK gene fusions with a focus on CRC, due to previous reports that spontaneous MSI in CRC enriches for complex genomic rearrangements, including NTRK fusions14. In NTRK fusion-positive CRC, 61.8% of cases were MSI-H (n = 47/76). Conversely, few non-CRC NTRK fusion-positive (0.93%; n = 7/751) or fusion-negative cancers were also MSI-H (1.3%; n = 3035/233,268; Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 12). Within NTRK fusion-positive MSI-H CRC, significant co-occurrence with RNF43 alterations and mutual exclusivity with BRAF, KRAS, PIK3CA, CTNNB1 and APC alterations was observed (Supplementary Table 13a). According to our assessment, spontaneous MSI-H (see Methods) represented 70.2% of NTRK fusion-positive MSI-H CRC cases (n = 33/47; Table 2). In NTRK fusion-positive spontaneous MSI-H CRC, mutual exclusivity was identified with BRAF alterations (Supplementary Table 13b). There were no germline MSI-H cases and four ambiguous MSI-H cases among MSI-H NTRK fusion-positive CRC (Table 2); no significant co-occurrences or exclusivities were seen in ambiguous MSI-H CRC. There was no enrichment in specific fusion partners seen in MSI-H CRC (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Evaluation of and microsatellite instability (MSI) status in NTRK fusion-positive versus NTRK fusion-negative solid tumours.

MSI status in all tumours (a), CRC only (b) and non-CRC tumours (c). CRC colorectal cancer, MSI-H microsatellite instability-high, MSS microsatellite stable, NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

Table 2.

Categorisation of MSI-H status among NTRK fusion-positive CRC, NTRK fusion-negative CRC and NTRK fusion-positive non-CRC tumours.

| Group | Total MSI-H, N | Spontaneous MSI -H, n (%) | Ambiguous MSI -H, n (%) | Germline MSI -H, n (%) | Othera MSI-H, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTRK fusion-positive MSI-H CRC | 47 | 33 (70.2) | 4 (8.5) | 0 | 10 (21.3) |

| NTRK fusion-negative MSI-H CRC | 1389 | 618 (44.5) | 228 (16.4) | 165 (11.88) | 378 (27.2) |

| NTRK fusion-positive MSI-H non-CRC | 2972 | 1545 (52.0) | 460 (15.5) | 194 (6.53) | 773 (26.0) |

MSI-H status was categorised into spontaneous, ambiguous or germline depending on alterations/short variants in PMS2, MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 as described in Methods.

CRC colorectal carcinoma, MSI-H microsatellite instability high, NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

aOther MSI-H refers to any MSI-H samples that did not fit the defined criteria in the Methods section.

Comparison of NTRK fusion-positive tumours in FoundationCORE with clinical trials

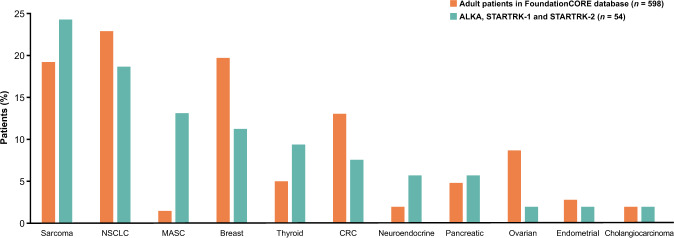

Fifty-four adults with 11 different NTRK fusion-positive tumour types were enrolled into the entrectinib ALKA-372-001, STARTRK-1 and STARTRK-2 trials9. Adult patients from the FoundationCORE database were matched to the 11 NTRK fusion-positive disease groups identified in trial patients. The frequency of patients with sarcoma, NSCLC, pancreatic, endometrial and cholangiocarcinoma cancers was similar in the clinical trial population and the FoundationCORE cohort (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table 14). The clinical trial population had a higher frequency of MASC, and the FoundationCORE population had a higher frequency of breast, CRC and ovarian cancers. Median age and sex distributions were similar in patients with NTRK fusion-positive tumours from the database and the clinical trials for the 11 matched tumour types (Supplementary Table 15).

Fig. 5. Comparisons of NTRK fusion-positive tumour types in entrectinib adult clinical studies versus FoundationCORE database.

CRC colorectal cancer, MASC mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, NTRK neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase.

Discussion

We investigated the prevalence of NTRK fusion-positive cancers and their relation to other biomarkers in a large population of >295,000 cancer cases from the FoundationCORE database; the largest cohort analysed for NTRK fusion-positive cancers to date. Similar to previous studies4–6, overall NTRK gene fusion prevalence was 0.30% (n = 889). Notably, we found a higher prevalence within the paediatric cohort (1.34%) than in adults (0.28%), largely attributed to the different tumour types/histologies commonly identified within these two NTRK fusion-positive cohorts. A fusion prevalence around 0.30% with low frequency among common cancers and higher frequency within certain rare cancers is in line with previous estimations from smaller datasets4–6. In the FoundationCORE database, Asian ancestry was associated with slightly increased NTRK gene fusions prevalence, possibly because of the higher proportion of NSCLC found in this cohort. Generally, NTRK gene fusions did not co-occur with other oncogenic drivers, supporting findings from smaller datasets6.

Due to the size of the FoundationCORE database and the large cohort of NTRK fusion-positive cases analysed, we were able to identify 88 different NTRK fusion partner pairs, of which 65.9% had not previously been reported in other large public databases4–6,8,9,12,13. Importantly, although the predicted specificity of DNA-based assays is lower than that of RNA-based assays, and thus has greater potential for false-positive results, all of these fusions were predicted to be pathogenic based on conservative definitions for functional rearrangements and mutually exclusive with other known oncogenic drivers, further arguing for their pathogenicity. Moreover, clinical bridging analyses in a selected clinical trial population15, estimated a response rate of 72.2% in patients with NTRK fusion-positive tumours identified by DNA-based assays, providing more evidence that these assays can detect pathogenic fusions. The significant number of rearrangements identified in our study that were not previously reported highlights the value of analysing large datasets and underscores the need for high-quality diagnostic methods ensuring identification of novel fusion partners. With the rarity of NTRK fusions, it seems important to cover known and unknown fusion events to identify patients qualifying for TRK inhibitor treatment. Due to their capacity to detect unknown fusions and to yield lower rates of false-negative and false-positive results than immunohistochemistry16, NGS assays are now integral to the process of identifying patients with tumours harbouring an NTRK fusion: when testing an unselected population, the ESMO guidelines for NTRK testing recommend front-line sequencing or screening by immunohistochemistry followed by sequencing of positive cases8.

To assess if the clinical trial cohorts investigating entrectinib for NTRK fusion-positive tumours were representative of the real-world situation, we compared the frequencies of the 11 matched NTRK fusion-positive tumour types between the clinical trial and real-world populations and found similar frequencies for most cancers. Notably, MASC tumours were much more frequent in the clinical trial population versus the real-world population, likely representing screening biases as NTRK fusions are highly prevalent in MASC7.

The large dataset analysed here allowed us to further describe the genomic landscape of NTRK fusion-positive cancers. In line with the assumption that NTRK-fusion-driven cancers are largely devoid of other oncogenic drivers, NTRK gene fusions were less likely to co-occur with common drivers, such as those involved in MAPK and PI3K signalling pathways (KRAS, PIK3CA) and with known oncogenic driver genes in breast cancer, CRC and NSCLC. Consequently, co-occurrence was seen with only 14 genes, including the most common fusion partner. The recent Rosen et al. study in NTRK fusion-positive cancers reported no co-occurrence with KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, EGFR, ALK, MET or ROS16, and we did not observe co-occurrence with these genes either. Apart from CRC (owing to the over-representation of MSI-H CRC), median TMB was not different between NTRK fusion-positive and -negative cases.

It has been described before that spontaneous MSI-H CRC enriches for complex rearrangements and targetable fusions, including NTRK fusions14. In contrast to hereditary MSI-H CRC (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer [HNPCC]/Lynch syndrome) in the setting of germline mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes17, spontaneous MSI-H CRC is predominantly caused by methylation of the MLH1 promoter and consecutive inactivation of the MLH1 gene18,19. In up to 75% of spontaneous MSI-H CRC, BRAF V600E mutations cause the CpG island methylator phenotype leading to the MLH1 promoter methylation described. Here we show that NTRK fusion-positive MSI-H CRC is a unique subset of CRC. First, most NTRK fusion-positive CRC cases are MSI-H and can be classified as spontaneous MSI-H. Secondly, and contrary to classical spontaneous MSI-H CRC, NTRK fusion-positive spontaneous MSI-H CRC does not carry BRAF mutations. This mutual exclusivity with BRAF V600E mutations suggests a yet unappreciated very rare subtype of spontaneous MSI-H CRC defined by the presence of NTRK gene fusions. Future studies will need to investigate the underlying biology of this observation. Importantly, these findings have immediate clinical implications, as testing for NTRK gene fusions in spontaneous MSI-H and BRAF wild-type CRC cases could identify patients who may benefit from NTRK-directed therapies.

Our study has some limitations. NGS testing with Foundation Medicine Inc assays does not cover the whole exome/genome, so while NTRK1/2/3 are interrogated, including all exons and specific introns, the description of the genomic characteristics of NTRK fusion-positive cancers cannot be considered exhaustive. Furthermore, comparisons to clinical trial cohorts were limited by a lack of clinical and demographic information available in the FoundationCORE database20. Finally, as we did not collect clinical outcomes data, we are unable to investigate the prognostic value of NTRK fusions in our cohort. Despite this, our study included the largest population used to profile the characteristics and genomic landscape of NTRK fusion-positive cancers in a tumour-agnostic setting.

The FoundationCORE database of >295,000 patient records, with an overall prevalence of 0.30% for NTRK fusion-positive cancers, allowed us to describe the largest cohort of NTRK fusion-positive cancers to date. From these 889 cases, we were able to identify 88 unique fusion partners of which two-thirds had not been reported before, underscoring the critical need for appropriate testing to identify this very small subgroup of cancers. Importantly, we were able to describe a subtype of spontaneous MSI-H CRC defined by the presence of NTRK fusions and the absence of otherwise pathogenic BRAF V600E mutations. The results presented here deepen our general understanding of NTRK fusion-positive cancers and might help clinicians to identify patients potentially suitable for NTRK-directed therapies.

Methods

FoundationCORE database samples

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP), including TMB21 and genetic ancestry prediction22, were carried out in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certified, College of American Pathologists accredited laboratory (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). Data from 295,676 de-identified, consented-for-research cases between January 2013 and December 2019 from 75 different solid tumour types were profiled. Detailed methods for this assay were previously described by Chmielecki, et al.23. Briefly, haematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides or Wright-Giemsa stained blood/aspirate smears were used to confirm the pathologic diagnosis of each case. Samples containing a minimum of 20% tumour cells were selected for subsequent RNA and/or DNA extraction, from 10-μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections or fresh blood/bone marrow aspirates, and genomic analysis. The FoundationOne® assay uses adaptor ligation and hybrid capture to analyse DNA for all coding exons of cancer-related genes (v1: n = 182; v2: n = 287; v3: n = 323; v5: n = 395) plus select introns from genes frequently rearranged in cancer (v1: n = 14; v2: n = 19; v3: n = 24; v5: n = 31)23. FoundationOne CDx uses hybrid capture to analyse all coding exons of 309 cancer-related genes plus select introns from 36 genes frequently rearranged in cancer24. FoundationOne® Heme v4 (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) uses DNA- and RNA-based hybrid capture to evaluate all coding exons of 465 genes plus select introns from 31 genes frequently rearranged in cancer; rearrangement analysis in 333 genes was performed by targeted RNA-sequencing for samples that had RNA available25,26. The sequences of captured libraries (median exon coverage depth >600x using Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) were analysed for select gene fusions, indels, base substitutions and copy number alterations, as previously described25,26. Variants removed from the dataset included germline variants (1000 Genomes Project [dbSNP142] or dbSNP database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), those with ≥2 counts in the ExAC database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) except for known cancer drivers (e.g. BRCA1/2 and TP53 mutations), and recurrent variants of unknown significance predicted to be germline by an internally developed algorithm27. Known confirmed somatic alterations according to the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) were highlighted as biologically significant.

Approval was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 20152817). Written consent was obtained to use the de-identified patient samples for research.

NGS from the FoundationCORE database

Co-occurrence of NTRK1/2/3 gene fusions with known and likely somatic alterations in each of >300 cancer-related genes was assessed across all samples. Odds ratios for mutational co-occurrence were generated using two-sided Fisher’s exact test. False discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P-values calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction were used to determine significance (P < 0.05). Co-occurrence was also evaluated with alterations of disease-specific driver genesets in their respective indications.

Throughout this analysis, NTRK fusion-positive cases were defined as those harbouring any NTRK1/2/3 rearrangement known or suspected to result in a fusion protein, consistent with definitions used in other pan-solid tumour prevalence studies4–6.

An assessment of NTRK fusion detection rate was conducted for the FoundationOne CDx platform using COSMIC v92 (cancer.sanger.ac.uk) as the reference baseline. Using 10 internal process-matched normal control specimens (each an equal mixture of 10 diploid HapMap cell lines), the mean sequence coverage at all genomic loci was calculated. Conservatively, using 100x as the minimum for which custom FoundationOne CDx algorithms would detect breakpoints, all annotated fusion breakpoints in NTRK1/2/3 in the COSMIC v92 database (TPM3:NTRK1, TPR:NTRK1 variant I, TPR:NTRK1 variant II, TFG:NTRK1, LMNA:NTRK1, TP53:NTRK1, QKI:NTRK2, NACC2:NTRK2, ETV6:NTRK3 variant I, ETV6:NTRK3 variant II, ETV6:NTRK3 variant III, and ETV6:NTRK3 variant IV) were compared with the empirically measured coverage profile of FoundationOne CDx. The expected NTRK fusion detection rate per fusion variant was calculated using Eq. (1):

Fusions without annotated breakpoint regions in COSMIC (n = 10) were ignored. All intron and exon base pair counts were measured using the hg19 reference sequence.

Predicted ancestry

Inferred estimated population ancestry was performed using germline single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Samples from the 1000 Genomes Project phase III dataset28 were used to train a classifier to recognise five ancestral populations: African, Central/South American, East and South Asian and European. In this approach, SNP allele counts variation was captured by the top five principal components29, and a random forest classifier was trained to recognise populations based on these four variation measures. The classifier was applied on patient samples to make ancestry calls, with confusion between Central/South American and European ancestries being observed22,30,31. Prevalence comparisons between predicted ancestry groups were calculated using two-sided Fisher’s exact test for the group of interest versus all other samples.

Microsatellite instability

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status can result from germline mutations in MMR genes (HNPCC/Lynch syndrome) or can be spontaneous due to hypermethylation of the MLH1 gene promoter20. Colorectal cancer (CRC) MSI-H status was categorised as spontaneous, germline or ambiguous, based on Sato and colleagues14. Spontaneous was defined as absence of known/likely pathogenic alterations (somatic or germline) in PMS2, MLH1, MSH2 or MSH618,19. Germline was defined as presence of ≥1 known/likely pathogenic variant in PMS2, MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 with predicted germline status based on a previously described somatic germline zygosity algorithm reported to have a 95–99% accuracy17,27. Ambiguous was defined as presence of known/likely pathogenic variant in PMS2, MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 that had an ambiguous somatic/germline status and no known/likely pathogenic variants in the aforementioned genes with a predicted germline status.

Clinical trial data comparisons

Details of the three entrectinib phase I/II clinical trials (ALKA-372-001, STARTRK-1, STARTRK-2) have been previously published9. In brief, patients were ≥18 years old, with metastatic/locally advanced NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours, measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours v1.1 and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2. Patients were enrolled based on local molecular testing (including fluorescence in situ hybridisation, quantitative polymerase chain reaction or DNA/RNA-based NGS) or central RNA-based NGS (Trailblaze Pharos™). Clinical characteristics of patients enrolled into these three clinical trials were compared with those of the real-world population from the FoundationCORE database.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dean Pavlick for his assistance in evaluating expected NTRK fusion detection rates in silico. M.G.K. would like to acknowledge support by NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. Third-party medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Laura Vergoz PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health company, and was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: C.B.W., M.G.K., C.L.T., E.S.S., S.L.M., T.R.W., D.F., L.V., M.T., F.d.B.; Data curation: S.M.; Formal analysis: E.S.S., S.L.M., D.X.J.; Funding acquisition: M.T.; Investigation: E.S.S., S.L.M., T.R.W., D.X.J., M.T., F.d.B.; Methodology: C.L.T., E.S.S., S.L.M., T.R.W., D.X.J., J.Y.N., D.F., M.T.; Validation: C.L.T., D.F.; Visualisation: E.S.S., S.L.M., D.X.J. All authors were involved in writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed during this study are described in the following data record: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1460446532. The data were generated and analysed under the auspices of Roche, which is a member of the Vivli Center for global clinical research data. Data access conditions are described at https://vivli.org/ourmember/roche/. To request access to individual patient-level data from the clinical trials, first locate the clinical trial in Vivli (https://search.vivli.org/ requires sign up and log in) using the trial registration number (given above), then click the ‘Request Study’ button and follow the instructions. In the event that you cannot see a specific study in the Roche list, an Enquiry Form can be submitted to confirm the availability of the specific study. To request access to individual patient-level data from the clinical trials, first locate the clinical trial in Vivli (https://search.vivli.org/ requires sign up and log in) using the trial registration number (ALKA-372-001 [EudraCT 2012-000148-88], STARTRK-1 [NCT02097810], STARTRK-2 [NCT02568267]), then click the ‘Request Study’ button and follow the instructions. In the event that you cannot see a specific study in the Roche list, an Enquiry Form can be submitted to confirm the availability of the specific study. To request access to related clinical study documents (e.g.: protocols, CSR, safety reports), please use Roche’s Clinical study documents request form: https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/research_and_clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing/clinical_study_documents_request_form.htm. Patient-level data which were derived from the Foundation Research dataset and used in the related study cannot be shared as they contain patient genomic information that, depending on the prevalence of the identified alterations, could be used to identify individuals. To maximise transparency and provide the most thorough information without compromising patients’ personal information, the authors have created a large number of supplementary files and made them openly available as part of the figshare data record32.

Competing interests

C.B.W. has received honoraria from Bayer, Celgene, Ipsen, Medscape, Roche, Servier; participated in advisory boards from Celgene, Shire/Baxalta, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, RedHill, Roche; received travel support from Bayer, Celgene, RedHill, Roche, Servier and Taiho; and received research support from Roche. M.K. has participated in advisory boards from Achilles Therapeutics, Bayer, Janssen, Octimet, OM Pharma and Roche; undertaken consultancy for Roche; received travel grants from AstraZeneca, BerGenBio and Immutep; and received research grants from BerGenBio and Roche. C.L.T. has participated in advisory boards from MSD, BMS, Merck Serono, Roche, Celgene, GSK, Rakuten, Nanobiotix, AstraZeneca and Seattle Genetics. E.S.S., D.X.J., J.Y.N. and D.F. are employees of Foundation Medicine and stockholders in Roche. S.L.M. and T.R.W. are employed by Genentech, Inc. and have equity in Roche. L.V. and M.T. are employed by Roche. F.d.B. reports advisory/consultancy fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Roche, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Istituto Gentili, Fondazione Internazionale Menarini, Octomet Oncology, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ignyta, Bayer, Noema, ACCMED, Dephaforum, Nadirex, Biotechspert, Pfizer, Tiziana Life Sciences and Pierre Fabre; has participated in speaker bureaus for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ignyta, Dephaforum, prIME Oncology, Pfizer and Biotechespert; has received research grants from Roche, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Kymab, Celgene and Tesaro and travel/accommodation expenses from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Celgene and Amgen.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/17/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41698-021-00222-y

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41698-021-00206-y.

References

- 1.Ricciuti B, et al. Targeting NTRK fusion in non-small cell lung cancer: rationale and clinical evidence. Med. Oncol. 2017;34:105. doi: 10.1007/s12032-017-0967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupain C, Harttrampf AC, Urbinati G, Geoerger B, Massaad-Massade L. Relevance of fusion genes in pediatric cancers: toward precision medicine. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;6:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet-Cordero EA, Biegel JA. The genomic landscape of pediatric cancers: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Science. 2019;363:1170–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamura, R. et al. Analysis of NTRK alterations in pan-cancer adult and pediatric malignancies: implications for NTRK-targeted therapeutics. JCO Precis. Oncol.10.1200/PO.18.00183 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Gatalica Z, Xiu J, Swensen J, Vranic S. Molecular characterization of cancers with NTRK gene fusions. Mod. Pathol. 2019;32:147–153. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen EY, et al. TRK fusions are enriched in cancers with uncommon histologies and the absence of canonical driver mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:1624–1632. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amatu A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S. NTRK gene fusions as novel targets of cancer therapy across multiple tumour types. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000023. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2015-000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchio C, et al. ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect NTRK fusions in daily practice and clinical research. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30:1417–1427. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doebele RC, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1–2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:271–282. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drilon A, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:731–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabrizio D, et al. Clinical and analytic validation of FoundationOne CDx™ for NTRK fusion-positive solid tumors in patients treated with entrectinib. J. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019;18:A028–A028. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The AACR Project GENIE Consortium. AACR Project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2020;7:818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Sanger Institute. Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC). https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic (2020).

- 14.Sato K, et al. Fusion kinases identified by genomic analyses of sporadic microsatellite instability–high colorectal cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:378–389. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dziadziuszko R, et al. Clinical validity of FoundationOne liquid CDx (F1L CDx) assay as an aid in selecting patients for treatment with entrectinib. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:S785–S786. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penault-Llorca F, Rudzinski ER, Sepulveda AR. Testing algorithm for identification of patients with TRK fusion cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019;72:460–467. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerretelli G, Ager A, Arends MJ, Frayling IM. Molecular pathology of Lynch syndrome. J. Pathol. 2020;250:518–531. doi: 10.1002/path.5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lochhead P, et al. Microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1151–1156. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisenberger DJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartmaier RJ, et al. High-throughput genomic profiling of adult solid tumors reveals novel insights into cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2464–2475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers ZR, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9:34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newberg J, Connelly C, Frampton G. Determining patient ancestry based on targeted tumor comprehensive genomic profiling. J. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1599–1599. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chmielecki J, et al. Genomic profiling of a large set of diverse pediatric cancers identifies known and novel mutations across tumor spectra. Cancer Res. 2017;77:509–519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foundation Medicine Inc. FoundationOne CDx™—Technical Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf17/P170019C.pdf (2017).

- 25.Frampton GM, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He J, et al. Integrated genomic DNA/RNA profiling of hematologic malignancies in the clinical setting. Blood. 2016;127:3004–3014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-664649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun JX, et al. A computational approach to distinguish somatic vs. germline origin of genomic alterations from deep sequencing of cancer specimens without a matched normal. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2018;14:e1005965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genomes Project Consortium. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connelly CF, Carrot-Zhang J, Stephens PJ, Frampton GM. Somatic genome alterations in cancer as compared to inferred patient ancestry. J. Cancer Res. 2018;78:1227–1227. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrot-Zhang J, et al. Comprehensive analysis of genetic ancestry and its molecular correlates in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:639–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westphalen, C. B. et al. Metadata record for the article: genomic context of NTRK1/2/3 fusion-positive tumours from a large real-world population. figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.14604465 (2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed during this study are described in the following data record: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1460446532. The data were generated and analysed under the auspices of Roche, which is a member of the Vivli Center for global clinical research data. Data access conditions are described at https://vivli.org/ourmember/roche/. To request access to individual patient-level data from the clinical trials, first locate the clinical trial in Vivli (https://search.vivli.org/ requires sign up and log in) using the trial registration number (given above), then click the ‘Request Study’ button and follow the instructions. In the event that you cannot see a specific study in the Roche list, an Enquiry Form can be submitted to confirm the availability of the specific study. To request access to individual patient-level data from the clinical trials, first locate the clinical trial in Vivli (https://search.vivli.org/ requires sign up and log in) using the trial registration number (ALKA-372-001 [EudraCT 2012-000148-88], STARTRK-1 [NCT02097810], STARTRK-2 [NCT02568267]), then click the ‘Request Study’ button and follow the instructions. In the event that you cannot see a specific study in the Roche list, an Enquiry Form can be submitted to confirm the availability of the specific study. To request access to related clinical study documents (e.g.: protocols, CSR, safety reports), please use Roche’s Clinical study documents request form: https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/research_and_clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing/clinical_study_documents_request_form.htm. Patient-level data which were derived from the Foundation Research dataset and used in the related study cannot be shared as they contain patient genomic information that, depending on the prevalence of the identified alterations, could be used to identify individuals. To maximise transparency and provide the most thorough information without compromising patients’ personal information, the authors have created a large number of supplementary files and made them openly available as part of the figshare data record32.