Summary

A recent Phase 1 clinical study of the immunological effects of inhibiting the chemokine receptor, CXCR4, in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or colorectal cancer suggests that stimulation of CXCR4 on immune cells suppresses the intratumoural immune reaction. Here, we discuss how CXCR4 mediates this response, and how cancer cells elicit it.

Subject terms: Immunosurveillance, Immunotherapy

Main

Patients with human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) or colorectal cancer (CRC) do not have durable responses to antagonists of the PD-1 pathway, unless their tumours exhibit microsatellite instability (MSIhi). MSIhi PDA or CRC has increased immunogenicity caused by frameshift mutations, shows the accumulation of T cells within cancer cell nests and frequently regress during treatment with anti-PD-1 antibody. Since T cells are absent from tumours from patients with microsatellite stable (MSS) CRC or PDA, cancer immunologists have reasoned that the exclusion of T cells is the basis for resistance to immunotherapy. Therefore, a major goal has been to understand how cancer cell nests prevent the infiltration of T cells.1 In this commentary, we consider the recent report that inhibiting CXCR4 in patients with MSS PDA or CRC may resolve this problem by promoting the accumulation and activation of intratumoural T cells.2

The homing of immune cells to secondary lymphoid and “damaged” tissues depends on the local production of chemokines that bind to chemokine receptors on the immune cells to stimulate their directed migration. The Phase 1 trial showing that inhibiting CXCR4 activated intratumoural immunity in patients with MSS CRC and PDA provides evidence that this immunological principle is relevant to cancer.2 This finding also validated the preclinical demonstration in a mouse model of PDA that depleting the intratumoural source of CXCL12, the chemokine that stimulates CXCR4, enhanced T cell infiltration and uncovered sensitivity to blocking the PD-1 checkpoint.3 Thus, one may conclude that the chemokine/chemokine receptor system contributes to the regulation of intratumoural immunity.

This clinical study was constrained by two characteristics shared by current small-molecule CXCR4 inhibitors, lack of oral bioavailability and short half-lives. The CXCR4 inhibitor used in the study, AMD3100, although approved for use in the mobilisation of haematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow, is not approved for the continuous administration that is required for uninterrupted inhibition of CXCR4. Fortunately, a precedent existed. AMD3100 had been administered to patients with HIV by continuous intravenous infusion for 1 week in a previous clinical trial assessing the effects of blocking HIV gp120 binding to CXCR4. Thus, it was possible to achieve continuous inhibition of CXCR4 for 1 week in patients with MSS PDA or CRC. However, since this short duration of CXCR4 inhibition would not be sufficient for a durable clinical response, the primary research objective became an analysis of the AMD3100-induced immunological changes in the tumours rather than clinical outcomes.

This scientific aim was accomplished by comparing the transcriptomes of paired biopsies of PDA or CRC metastases taken before and at the end of AMD3100 infusion. The transcriptional analysis showed that CXCR4 blockade by AMD3100 administration to patients for only 1 week induced intratumoural immune responses that involved multiple mediators and cells of the innate and adaptive immune responses. This multifaceted, “integrated” type of immune response is most likely programmed, as it was found in other examples of immunological damage to non-infected tissues, such as rejecting allografts, breast and lung cancers, and melanomas of patients responding to treatment with antibodies to CTLA-4 and PD-1. The capacity of CXCR4, which is expressed by all immune cell types, to control an integrated immune response may be related to its ability to suppress the chemotactic function of other chemokine receptors that direct the migration of neutrophils, monocytes, B cells and effector T cells. Most importantly, the integrated immune response in the metastatic tissues elicited by CXCR4 inhibition included increased expression of genes whose products mediate cytotoxicity by CD8+ T cells that correlated with decreased expression of genes characteristic of cancer cells. Thus, continuous inhibition of CXCR4 in these patients for only 1 week allowed their pre-existing anti-cancer immune responses to overcome CXCL12-mediated intratumoural immune suppression. This finding provides the rationale for extending CXCR4 inhibition for longer periods, as is done for other immunotherapies, and for combining this approach with an antagonist of the PD-1 checkpoint, since blocking these two targets had synergistic anti-tumour effects in PDA-bearing mice.3

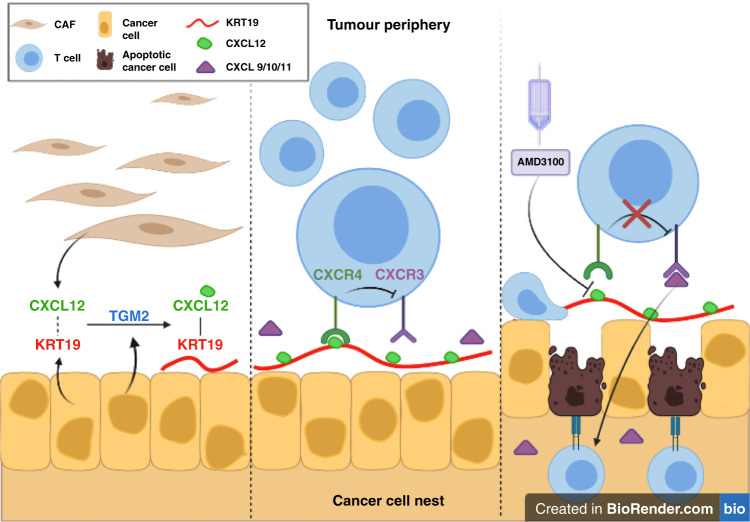

The study by Biasci et al.2 also provided a clue to how cancer cells stimulate CXCR4 to exclude T cells from cancer cell nests; they are “coated” with CXCL12. Another recent study has shown that this CXCL12-coating of PDA and CRC cells represents covalent heterodimers of the chemokine with keratin-19 (KRT19) that are formed by transglutaminase-2 (TGM2)4 (Fig. 1). Interrupting expression of either KRT19 or TGM2 by PDA cells in mouse tumours prevents the formation of the CXCL12–KRT19 coating, allows the intratumoural accumulation of T cells, and uncovers sensitivity of the PDA tumours to T cell checkpoint immunotherapy. Thus, carcinomas have a capacity to capture the ligand for CXCR4, which enables them to exclude T cells from their immediate vicinity to escape immune attack.

Fig. 1. Blocking CXCR4 with AMD3100 allows T cell killing of CXCL12-coated cancer cells.

Left panel Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumour secrete CXCL12, which reversibly binds to KRT19 on the surface of PDA and CRC cancer cells. Cancer cell-derived TGM2 then covalently crosslinks the two proteins. Middle panel The CXCL12–KRT19 heterodimers stimulate CXCR4 on adjacent T cells to inhibit the ability of CXCR3 to mediate their infiltration into cancer cell nests. Right panel Administration of AMD3100 blocks the interaction between the cancer cell-associated CXCL12–KRT19 heterodimers with CXCR4 on T cells and allows their CXCR3 to respond to CXCL9/10/11 to mediate the accumulation of T cells in cancer cell nests.

Does this mechanism for the exclusion of T cells by cancers relate to other explanations for tumour immune suppression? The finding that CXCR3 mediates the intratumoural accumulation in mouse solid tumours5 is consistent with the finding that CXCR4 inhibits CXCR3 (Fig. 1).2 The presence of only “exhausted” intratumoural T cells6,7 may be a consequence of the exclusion of non-senescent, replication-competent T cells. The ineffectiveness of CAR T cell therapy in solid tumours may be caused by the exclusion of the genetically engineered T cells from cancer cell nests. Vaccination of patients with PDA with tumour-associated antigens, despite showing evidence of an enhanced intratumoural immune reaction, does not induce durable clinical responses, again perhaps because of the CXCR4-mediated exclusion of the vaccine-primed T cells.8 Therefore, one may predict that therapy-inhibiting CXCR4 or the formation of the CXCL12–KRT19 heterodimer would complement other immunotherapies directed at endogenous T cells, adoptively transferred T cells or the CXCL12-producing cancer-associated fibroblasts.9,10 Clinical trials of longer-term inhibition of CXCR4 in combination antagonists of the PD-1 checkpoint are urgently needed to assess the therapeutic potential of overcoming CXCR4-mediated T cell exclusion.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Jordan A. Pearson who created Fig. 1.

Author contributions

DTF contributed to the conception of the work and drafted the manuscript. KD contributed to the writing of the paper. Both authors approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348:74–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biasci D, Smoragiewicz M, Connell CM, Wang Z, Gao Y, Thaventhiran JED, et al. CXCR4 inhibition in human pancreatic and colorectal cancers induces an integrated immune response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:28960–28970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013644117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJ, Deonarine A, Chan DS, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20212–20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, Z., Yan, R., Li, J., Gao, Y., Moresco, P., Yao, M. et al. Pancreatic cancer cells assemble a CXCL12-keratin 19 coating to resist immunotherapy. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/776419 (2020).

- 5.Chow, M. T., Ozga, A. J., Servis, R. L., Frederick, D. T., Lo, J. A., Fisher, D. E. et al. Intratumoral activity of the CXCR3 chemokine system is required for the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy. Immunity50, 1498–1512 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019;37:457–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott AC, Dündar F, Zumbo P, Chandran SS, Klebanoff CA, Shakiba M, et al. TOX is a critical regulator of tumour-specific T cell differentiation. Nature. 2019;571:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutz ER, Wu AA, Bigelow E, Sharma R, Mo G, Soares K, et al. Immunotherapy converts nonimmunogenic pancreatic tumors into immunogenic foci of immune regulation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:616–631. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford K, Hanley CJ, Mellone M, Szyndralewiez C, Heitz F, Wiesel P, et al. NOX4 inhibition potentiates immunotherapy by overcoming cancer-associated fibroblast-mediated CD8 T-cell exclusion from tumors. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1846–1860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasashima, H., Duran, A., Martinez-Ordoñez, A., Nakanishi, Y., Kinoshita, H., Linares, J. F. et al. Stromal SOX2 upregulation promotes tumorigenesis through the generation of a SFRP1/2-expressing cancer-associated fibroblast population. Dev. Cell56, S1534–S5807 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.