Abstract

Wheat gluten was hydrolyzed with both alkaline protease and neutral protease to produce high-protein and low-wheat-weight oligopeptides (WOP), which was subjected to a multistage purification. Then, high performance liquid chromatography was applied to separate WOP. In order to identify WOP sequences, six major fractions were gathered for mass spectrometry. A total of 15 peptides were synthesized for further in vitro analyses of their antithrombotic activity, vasorelaxation activity, and cholesterol reducing activity. Two antithrombotic peptides (ILPR and ILR), three vasorelaxant peptides (VN, FPQ, and FR), and four cholesterol-lowering peptides (QRQ, ILPR, FPQ, and ILR) were identified. These active peptides in WOP were also quantified. These peptides are novel candidate peptides with vascular disease suppressing effects. The results indicate WOP as good protein sources for multifunctional peptides.

Keywords: Wheat oligopeptides, Antithrombotic activity, Vasorelaxation activity, Cholesterol reducing activity

Introduction

As a primary cause of death and debilitation across the world, vascular disease is a form of cardiovascular disease that primarily affects the blood vessels. When diagnosed with vascular diseases, avoidance of multiple risk factors is particularly important (Graham et al. 1997; Kinsella et al. 1990; Levy 1984). Due to the concerns about adverse side effects of prescribed drugs, the demand for safer and more novel vascular disease inhibitors becomes increasingly higher. To address this demand, researchers have separated and characterized bioactive peptides from a lot of natural and non-natural foods (Korhonen, Pihlanto 2003). The peptides have been found to exhibit various bioactivities, such as antithrombotic, vasorelaxing, cholesterol-lowering, antioxidative, antihypertensive, and antimicrobial activities (Adebiyi et al. 2009; Beathice et al. 1995; Guani-Guerra et al. 2010; Masaaki et al. 2000; Nagaoka et al. 2001; Qian et al. 2007). Among the different kinds of bioactive peptides, those with suppression effects on vascular diseases have attracted strong attention, due to their potential beneficial effects related to many diseases.

Wheat (Triticum spp.) is a worldwide cultivated cereal grain, and has been the third major cereal only second to maize and rice. Wheat gluten consists of the proteins gliadin and glutenin. There are nearly 30% of hydrophobic amino acid residues in wheat gluten, which make a significant contribution to forming protein aggregates by hydrophobic effect and binding of nonpolar substances (Suetsuna, Chen 2002). One of the main factors limiting its usage in food processing is the insolubility of gluten in aqueous solutions (Kong et al. 2007). Enzymatic hydrolyzation of wheat gluten is a practical way to produce protein hydrolysates and peptides. With regard to the peptides derived from wheat gluten, several reports addressed their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, atheroprotective and opioid properties (Suetsuna et al. 2002; Montserrat-de la Paz et al. 2020; Pruimboom and de Punder 2015; Fukudome and Yoshikawa 1992). However, as far as we know, information on the suppressive effects of peptides derived from wheat gluten on vascular diseases has not been reported to date.

In the present study, high-protein and low-molecular-weight wheat oligopeptides (WOP) powder was prepared by hydrolyzing wheat gluten with alkaline protease and neutral protease. The in vitro antithrombotic, vasorelaxant, and cholesterol-lowering activities of WOP were evaluated. Furthermore, reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was adopted to separate WOP, and 15 peptides were isolated from WOP. Their in vitro antithrombotic activity, vasorelaxation activity, and cholesterol reducing activity were demonstrated.

Materials and approaches

Materials and reactants

CF Haishi Biotechnology Ltd., Co. (Beijing, China) donated wheat gluten. Novo Nordisk (Copenhagen, Denmark) and Genencor Division of Danisco (Rochester, NY, USA) supplied the proteases. GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China) offered the peptides after synthesis. According to the identification by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the purity degree of synthesized peptides was more than 98%. Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) provided Acetonitrile. Alfa Aesar (Tianjin, China) is the seller of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) offered thrombin and fibrinogen from human plasma and acetylcholine (ACh) as positive control. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) from Australia was purchased from Corning CellGro (Mediatech). Through the National Bio-Resource Project of MEXT, Japan, RIKEN BRC supplied human liver carcinoma cells (HepG2, RCB1886). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC, IFO50271) were supplied by the Health Science Research Resources Bank (HSRRB), Japan. All other reagents were of analytical or guaranteed reagent grade and were used without further purification.

Enzymatic preparation of WOP

Wheat gluten was dissolved in distilled water until the protein concentration reached 10% (w/w), and a homogenizer (Donghua Homogenizer Factory, Shanghai, China) was used to stir it at 25,000×g for 10 min. Alkaline protease was used for 2-h enzymatically digestion of the protein slurry to a substrate protein proportion of 1:100 (w/w) at pH 8.5 and 55 °C. Next, for the second step, the 2-h enzymatic hydrolysis of the mixture was made with neutral protease (1:100, w/w) at pH 6.5 and 60 °C. In order to keep the pH of the reaction mixture constant during hydrolysis as required, 1.0 mol/L HCl or NaOH was added. The hydrolysis was stopped by increasing the temperature to 100 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, an LG10-2.4A centrifuge (Beijing LAB Centrifuge Co., Ltd. in Beijing, China) was used to centrifuge the resultant hydrolysate at 3000×g for 15 min. In order to get the permeate liquid which contained oligopeptides, molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) ceramic membranes of 10 and 1 kDa (Filter and Membrane Technology Co., Ltd., Fujian, China) were used to filter the supernatant. For the removal of residual salts, a MWCO nanofilter membrane of 100 Da (Filter and Membrane Technology Co., Ltd. in Fujian, China) was adopted to dialyze the permeate at pH 6.5–7.5. Then, a R-151 rotary evaporator (Buchi Co., Ltd., Flawil, Switzerland) was applied to condense the solution to the solid content of 30–50%. Next, 5% of active charcoal was employed to decolorize the concentrated liquid at 80 °C for 30 min, followed by filtering with a sand-core funnel of 4511–500 mL-3 (Shanghai Preferential Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Finally, L-217 Lab (Beijing Laiheng Lab-Equipments Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was conducted to spray dry the resulting liquid, and WOP powder was got.

Chemical composition and molecular weight distribution analyses of WOP

The approaches of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC 2002) was used to determine the chemical compositions. While using the system of LC-20A HPLC (Shmadzu, Kyoto, Japan), gel permeation chromatography was applied to analyze the molecular weight (MW) distribution on a TSK gel G2000 SWXL of 300 × 7.8 mm column (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan). The mobile phase (45% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA, v/v) was adopted for HPLC at the flow rate of 0.5 mL/min under the monitoring at 220 nm and 30 °C. In the aspect of MW standards, tripeptide GGG (Mr 189), tetrapeptide GGYR (Mr 451), bacitracin (Mr 1450), aprotinin (Mr 6500), and cytochrome C (Mr 12,500) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) were used (Kong et al. 2008).

Separation of WOP

The dissolution of WOP was conducted in Milli-Q water at the concentration of 10 mg/mL. Then, an XBridge BEH130 C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, Waters, MA, USA) was used to load them onto RP-HPLC at the flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The volume of 50 µL was injected. The linear gradient of solvent A (Milli-Q water with 0.1% TFA, v/v) and solvent B (80% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA, v/v) was used to make elution: 0–15% B during 0–50 min; 15–40% B during 50–120 min; 40–80% B during 120–140 min. The monitoring was made on the absorbance of the eluent at 220 nm. Lyophilization of the fractions was made for sequence identification (Gu et al. 2011).

Identification of active peptides

The National Center of Biomedical Analysis (Beijing, China) conducted the mass analysis. The determination of the molecular mass of the purified fractions was made by a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Q-TOF2; Micromass Co., Manchester, UK) where there was an electrospray ionization (ESI) source based on the supplier’s guidelines. The mass spectrum was analyzed using MassLynX software (Waters, USA).

Antithrombotic activity of the peptides

The approach of Yu et al. (2011) was adopted to measure the antithrombotic activity. Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) which contained 0.154 mM NaCl was adopted to prepare fibrinogen (0.1% w/v) and thrombin (10 U/mL). After adding 30 µL of sample (or Tris–HCl buffer) and 105 µL of fibrinogen solution to the 96-well plate, 5-min mixing and incubation were made for the mixture. Next, the reaction started after adding 7.5 µL of thrombin, which was followed by four-minute vigorous mixing at 37 °C. An infinite M1000 microplate reader (Tecan Japan Co., Ltd., Kawasaki, Japan) was employed to measure the absorbance at 405 nm. The antithrombotic activity was calculated as (A1—A2)/(A1—A0) × 100%, where A1 represents the absorbance of the reaction solution which contained Tris–HCl buffer rather than peptide sample; A2 represents the absorbance of the reaction solution which contained peptide sample; and A0 represents the absorbance of the reaction solution which contained buffer solution instead of thrombin.

Vasorelaxation activity of the peptides

Cultured endothelial cells were used to examine vasorelaxation activity according to the report of Hirota et al. (2011). Under the conditions of 5% CO2, HUVEC were routinely grown in HuMedia-EG2 medium (KURABO, Osaka, Japan) at the temperature of 37 °C. Subsequently, HUVEC were plated into 96-well plates at 2500 cells/cm2 until the cells were in the confluent state. The cells were precultivated for 4 h after the media were replaced with serum and phenol red-free media. Then, the samples dissolved in the replaced media were added to the cell culture. From independent wells, the supernatants were collected before and 1 h after adding samples, and an NO2/NO3 assay kit-FX (Dojindo Laboratories in Kumamoto, Japan) was adopted to measure the NOx (nitrate and nitrite) concentrations in the supernatants collected according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cholesterol reducing activity of peptides

The cholesterol reducing activity was measured via human cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) gene expression in Human liver cells (HepG2) using the method of Morikawa et al. (2007). HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s improved eagle medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% (v/v) FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2 conditions. Next, after seeding HepG2 cells with the density of 5000 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates, cultivation in serum-free DMEM was made during peptide treatment periods (for 24 h). After treatment, an SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was applied to prepare total RNA from HepG2 cells. A NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was used to make quality and quantity evaluation on RNA. Subsequently, while applying an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA), the total RNA was converted to cDNA on a Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems). In terms of the real-time PCR on a CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad), an SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan) was employed. Primers for PCR: β-actin forward: 5′-TGTGTTGGCGTACAGGTCTTTG-3′; β-actin reverse: 5′-GGGAAATCGTGCGTGACATTAAG-3′; CYP7A1 forward: 5′-TTGTGAATACATGGCTGGAATAAGA-3′; CYP7A1 reverse: 5′-GGACTGTGTGGTGAGGGTGTT-3′. The primers were synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Japan). The mRNA expression levels of CYP7A1 were standardized against β-actin.

Quantitative analysis of active peptides in WOP

The active peptides in WOP were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC and tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS/MS). For the separation of peptides on a MSLAB HP-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm) by ten-minute gradient elution at the flow rate of 1 mL/min, an ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, USA) was adopted. Eluent A (Milli-Q water which contained 2 mmol/L ammonium formate) and eluent B (acetonitrile which contained 2 mmol/L ammonium formate) were used to elute peptides. Ten microliters of the sample was injected. The system of API 3200 Q TRAP LC/MS/MS (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) equipped with an ESI source was used to perform tandem mass spectrometry. In the positive mode, the ionspray voltage was 4500 V. The mass spectrum was analyzed using Analyst Software 1.5 (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Statistical analysis

The relevant NOx concentrations (%) in culture medium after 1-h processing in each group were compared by analyzing variances in one way, and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was made for subsequently comparing the control and test substances. GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was adopted to process all statistics. A significance level of p < 0.05 was employed.

Experiment results and related discussion

Chemical compositions and MW distribution of WOP

According to the analysis of chemical compositions, the contents of protein, lipid, ash, and moisture (dry basis) of WOP were 97.43 ± 0.58%, 0.06 ± 0.01%, 4.42 ± 0.24%, 4.09 ± 0.19%, and 4.28 ± 0.23%, respectively. After enzymatic 0hydrolysis and purification, the protein content of WOP reached up to 97.43 ± 0.58%. In the process of WOP preparation, insoluble undigested nonprotein substances were removed, protein was solubilized during hydrolysis, and lipids were removed partially after hydrolysis. These may be the reasons for the high protein content of WOP (Benjakul and Morrissey 1997). The results showed the effective production and high nutritional value of the produced WOP due to their high protein content.

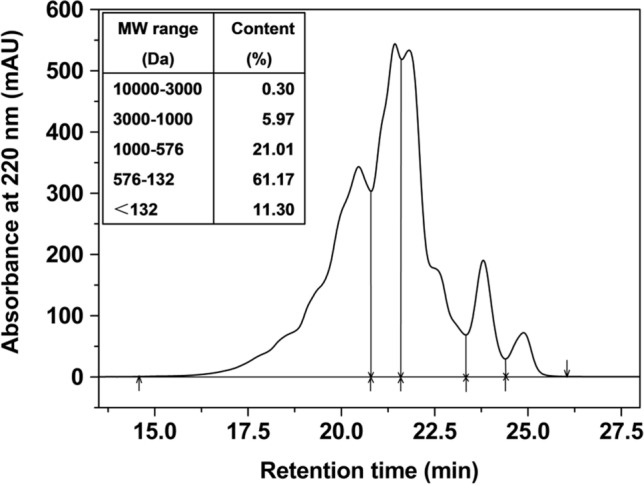

According to chromatographic data (Fig. 1), there were high content (93.48%) of oligopeptides in WOP below 1000 Da. WOP were mainly composed of the peptides in the MW ranging from 132 to 576 Da (61.17%). With easy absorption rate by human body, oligopeptides can effectively enter the blood circulation by overcoming the intestinal barrier compared with both amino acids and intact proteins (Roberts et al. 1999). Moreover, compared with longer peptides, oligopeptides can exert a physiologically influence in vivo because they are less susceptible to gastrointestinal hydrolysis (Gómez-Ruiz et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

Size exclusion chromatographic plot, showing the molecular weight (MW) distribution of wheat oligopeptides (WOP). (Inset) Content of peptides with different classes of MW range in WOP

Separation of WOP and identification of peptides from WOP

To purify and identify peptides, a linear gradient of acetonitrile was used to separate WOP on a RP-HPLC column. While separating proteins and peptides, RP-HPLC is widely applied due to its higher solubility, better repeatability, and higher rate of recovery (Liu et al. 2011). Figure 2 shows the elution profile of WOP and the selected six fractions (fractions 1–6) during different elution timeframes. After chromatography, pooling and freeze-drying were made on these fractions, and in order to confirm the active peptides, Q-TOF2 mass spectrometry was conducted. The mass spectra of these fractions are shown in Fig. 3. In a word, 15 peptides were synthesized and determined as candidate peptides with suppressing effects on vascular diseases. Table 1 summarizes the sequences of amino acids and molecular weights of peptides with 2–4 amino acid residues and molecular weights below 1000 Da.

Fig. 2.

Purification profiles of wheat oligopeptides (WOP) digested by alkaline protease (at pH 8.5, 55 °C, and for 2 h) and neutral protease (at pH 6.5, 60 °C, and for 2 h). Separation was achieved on an XBridge BEH130 C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) using a linear gradient of solvent A (0.1% TFA in Milli-Q water, v/v) and solvent B (80% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The collected fractions are numbered from 1 to 6

Fig. 3.

Mass spectra of RP-HPLC fractions 1–6 (A-F) from wheat oligopeptides (WOP) using a Q-TOF2 mass spectrometer (Micromass Co., Manchester, UK) equipped with an ESI source

Table 1.

Identification of oligopeptides contained in the RP-HPLC fractions by a Q-TOF2 mass spectrometry

| Peptide sequencea | Observed mass | Calculated massb | RP-HPLC fractionc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Val-Asn (VN) | 231.11 | 231.25 | 1 |

| Gln-Arg-Gln (QRQ) | 430.21 | 430.46 | 1 |

| Ala-Pro-Ser-Tyr (APSY) | 436.19 | 436.46 | 2 |

| Pro-Tyr (PY) | 278.12 | 278.31 | 3 |

| Ile-Leu-Arg (ILR) | 400.28 | 400.52 | 3 |

| Lys-Asn-Phe (KNF) | 407.20 | 407.47 | 3 |

| Pro-Gln (PQ) | 243.13 | 243.26 | 4 |

| Leu-Tyr (LY) | 294.16 | 294.35 | 4 |

| Arg-Gly-Gly-Tyr (RGGY) | 451.22 | 451.48 | 4 |

| Phe-Pro-Gln (FPQ) | 390.21 | 390.44 | 5 |

| Gln-Pro-His-Pro (QPHP) | 477.27 | 477.52 | 5 |

| Tyr-Gln (YQ) | 309.22 | 309.32 | 6 |

| Leu-Val-Ser (LVS) | 317.13 | 317.39 | 6 |

| Phe-Arg (FR) | 321.12 | 321.38 | 6 |

| Ile-Leu-Pro-Arg (ILPR) | 497.36 | 497.64 | 6 |

aLetters in parentheses indicate a single-letter representation of amino-acid sequence

bAverage mass

cFractions are termed as in the legend of Fig. 2

Antithrombotic activity of the peptides

Thrombosis refers to the thrombogenesis inside blood vessels, and the blood circulation through the circulatory system was obstructed. Thrombotic disease is one of the most significant factors causing death. The peptides with antithrombotic activity may be effective for vascular disease prevention and treatment (Johnson 2008; Klafke et al. 2012).

According to the current study, WOP failed to exhibit antithrombotic activity even at the high concentration of 40 mg/mL. Alike results were previously reported for porcine skin collagen hydrolysate and egg white protein hydrolysate (Maruyama et al. 1993; Yang et al. 2007). According to a research by Maruyama et al. (1993), thrombin activity was not inhibited by hydrolysating porcine skin collagen which contained thermolysin or bacterial collagenase. Yang et al. (2007) determined the anti-thrombosis of egg white protein hydrolysate which showed an activity of about 10% at the concentration of 40 mg/mL.

For the 15 peptides, the antithrombotic activities were found in two peptides at a concentration of 10 mM (Fig. 4). The tetrapeptide ILPR exhibited a stronger activity (23.3 ± 4.5%) than the tripeptide ILR (3.3 ± 0.6%). The other 13 peptides did not exhibit activities at this concentration. To the authors’ knowledge, these two peptides can be treated as novel peptides with antithrombotic activities which were not reported previously. In the study of Yu et al. (2011), after extracting the peptide Arg-Val-Pro-Ser-Leu (RVPSL) from egg white protein, its antithrombotic activity was tested. The result showed that the activity ranged between 20 and 30% at a concentration of 10 mM. Compared with their study, the activity of ILR was weaker than that of RVPSL, whereas the activity of ILPR was similar to that of RVPSL.

Fig. 4.

Antithrombotic activity of two peptides from wheat oligopeptides (WOP) at a concentration of 10 mM. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD; n = 3)

With regard to the association between the structure and activity of antithrombotic peptides, according to the report, the Arg-Gly bonds of fibrinogen was cleaved by the endolytic serine protease thrombin selectively, so as to form fibrin and liberate the fibrinopeptides A and B. The best cleavage sites for thrombin include: (1) A-B-Pro-Arg-||-X-Y where A and B refer to hydrophobic amino acids, and X and Y represent nonacidic amino acids, and (2) Gly-Arg-||-Gly (Chang 1985). In the present study, ILR and ILPR with Arg at the C-terminus showed potent antithrombotic activity. But, FR with an Arg at the C-terminus did not exhibit antithrombotic activity. Therefore, the presence of preferred peptide sequences fails to determine the activity of peptides. In virtue of integrating preferred amino acids, synergistic effects and other causes, the antithrombotic properties of peptides are produced.

Vasorelaxation activity of peptides

One of the factors causing cardiovascular diseases is the increase in arterial stiffness. In case of the dilation of blood vessels, the blood flow volume will increase because vascular resistance decreases. Therefore, blood pressure decreases due to arterial blood vessels dilate (Heitzer et al. 2001; Hirota et al. 2011). In the vascular regulation, the vasorelaxation factors produced by the endothelium play crucial parts through releasing such substances (Lüscher 1990; Vanhoutte 1989). NO is able to protect blood vessels as the most effective endogenous vasorelaxation substance (Huang et al. 1995).

In this study, the effects of WOP and peptides on the induction of NOx production were demonstrated. After adding Ach (positive control) at the final concentration of 1 mM to the HUVEC culture media, NOx concentration in the media increased to 137.2 ± 11.6% after one hour compared with that without Ach. Likewise, after adding WOP at the final concentration of 1 mg/mL, the relative NOx concentration in the media after 1 h was higher (131.9 ± 15.8%) than that without WOP (Fig. 5). After adding the tested peptides from WOP at the final concentration of 1 mM, the NOx concentrations increased after 1 h by comparing with that without tested peptides. While comparing the group of test materials with control group, the relative NOx concentrations of culture media at 1 mg/mL of WOP, 1 mM of ACh, VN (196.4 ± 25.6%), FPQ (172.1 ± 21.9%), and FR (130.3 ± 10.4%) were greatly higher (p < 0.05) at 1 h after addition of test materials.

Fig. 5.

Relative NOx concentrations in culture media of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). Data are expressed as percentage values relative to the NOx concentration at 0 h. Cells were treated with acetylcholine (Ach, 1 mM), wheat oligopeptides (WOP, 1 mg/mL), or peptides (1 mM) for 1 h. Values are expressed as mean ± SD of four determinations. Statistical significance compared with medium treatment was assessed by Student’s t test. Asterisks indicate statistical significance compared to medium treatment at p < 0.05

According to a previous study (Hirota et al. 2011), the same cell types were used to examine the impact of Val-Pro-Pro (VPP) and Ile-Pro-Pro (IPP) on the induction of NOx production. The result showed that compared with that in the control group, the NOx concentration in the test group was greatly higher after adding VPP and IPP to the medium of cultured endothelial cells at final concentrations of 0.01 mM. Although VN, FPQ, and FR in this study displayed a less potent activity than VPP and IPP, VN and FPQ showed a more powerful ability than the positive control Ach and WOP, and FR showed a similar ability to both Ach and WOP. To the best of our knowledge, VN, FPQ, and FR were identified as vasorelaxation peptides for the first time.

According to Hirota et al. (2011), vasorelaxation was caused by the influence of VPP and IPP, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides, on vascular endothelial cells. According to their research, these peptides were conducive to the vasorelaxation effect of bradykinin because they could inhibit the degradation of bradykinin by ACE. Furthermore, they would induce the production of vasorelaxant substances such as NO by endothelial cells through the B2 receptor. In the present study, FR was also reported to be an ACE inhibitory peptide in the literature (Cushman 1981). Therefore, the mechanism underlying the vasorelaxation activity of the peptide may connect with the ACE inhibiting effect. However, VN and FPQ were not reported as ACE inhibiting peptides in the literature. Therefore, the investigation on the mechanism of vasorelaxation activity of the peptides shall be researched further.

Cholesterol reducing activity of the peptides

Hypercholesterolemia refers to the presence of cholesterol at high level. In the cholesterol metabolism, the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1; EC 1.14.13.17) is an enzyme with limited rate in the classical (neutral) pathway of transforming the bile acid into cholesterol (Martin et al. 1993). It seems that the regulatory control is mainly exerted at the gene transcription level because CYP7A1 activity is highly related to CYP7A1 mRNA abundance (Agellon et al. 2002).

In the current research, the influence of WOP and peptides on the cholesterol metabolism gene human CYP7A1 was investigated (Fig. 6). The results showed that treatment with WOP increased the CYP7A1 gene expression (127.7 ± 17.9%). Among the 15 peptides, 1 mM QRQ, ILR, FPQ, and ILPR greatly increased the CYP7A1 mRNA level (p < 0.05) (ranging from 130.9 ± 8.0 to 159.1 ± 24.2%). Treatment with these peptides activated CYP7A1 gene expression more significantly than treatment with WOP. To the best of our knowledge, it is first reported that in the aspect of inducing CYP7A1 mRNA, all these active peptides are effective.

Fig. 6.

Effects of WOP (5 mg/mL) and peptides (1 mM) on CYP7A1 gene expression in HepG2 cells involved in cholesterol metabolism. HepG2 cells were treated with WOP (5 mg/mL) or peptides (1 mM) for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted from the treated cells and used for quantitative real-time PCR analyses. All data are shown as mean ± SD of three determinations. Statistical significance compared to medium treatment was assessed by Student’s t test. Asterisks indicate statistical significance compared to medium treatment at p < 0.05

Morikawa et al. (2007) assessed the effects of 1 mM Ile-Ile-Ala-Glu-Lys (IIAEK) and its fractional peptides on CYP7A1 gene expression. The results showed that IIAEK increased the mRNA level to approximately 170% of that of the control. According to the treatment of the fragmented peptides of IIAEK, in terms of inducing CYP7A1 mRNA, the C-terminal side of IIAEK, especially EK, was important. In the present study, QRQ, ILR, FPQ, and ILPR showed similar results as IIAEK. Morikawa et al. (2007) demonstrated a novel regulation approach that was involved in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway related to calcium channel for IIAEK-mediated cholesterol degradation. In this context, we plan to continue this investigation of the mechanism of active peptides-mediated induction of CYP7A1 mRNA.

Quantitative analysis of active peptides in WOP

The concentrations of the active peptides ILPR, ILR, VN, FPQ, FR, and QRQ were estimated by HPLC/MS/MS. Quantifications of ILPR, ILR, VN, FPQ, FR, and QRQ were performed, and it was determined that there were 1.5517, 0.2354, 0.1182, 0.0653, 1.2241, and 0.3528 mg/g of the above peptides in WOP, respectively. These peptides were all candidate peptides with beneficial effects for vascular function.

Conclusion

In this study, a method to produce high protein and low molecular weight WOP was developed. Furthermore, two antithrombotic peptides (ILPR and ILR), three vasorelaxant peptides (VN, FPQ, and FR), and four cholesterol-lowering peptides (QRQ, ILPR, FPQ, and ILR) were isolated and identified in WOP. According to the research results, wheat gluten was identified as an excellent protein source of active peptides by enzyme hydrolysis. In this report, the multifunctional peptides identified can be treated as an ingredient of nutraceuticals and functional food. The investigation on the in vivo effects of each peptide shall be researched further. Moreover, analysis of the functional mechanisms of the peptides is needed.

Author contributions

This work was designed by M.T., M.-Y.C., T.M., and W.-Y.L.; the experiments were carried out by W.-Y.L., T.M., J.L., Y.H.H., R.-Z.G., Y.M., and K.K. under the supervision of M.T. and M.-Y.C. All authors contributed to the results and discussion. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by W.-Y.L., and all authors contributed to the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFD0400604 to MC) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (Grant number, 23228003).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wen-Ying Liu, Email: wenyingliu888@126.com.

Takuya Miyakawa, Email: atmiya@mail.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Jun Lu, Email: johnljsmith@163.com.

Yun Hua Hsieh, Email: jennifer19870905@gmail.com.

Ruizeng Gu, Email: guruizeng@163.com.

Yumiko Miyauchi, Email: yumisukem@hotmail.com.

Kana Katsuno, Email: taido-girl@hotmail.co.jp.

Mu-Yi Cai, Email: caimuyi@vip.sina.com.

Masaru Tanokura, Email: amtanok@mail.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

References

- Adebiyi A, Adebiyi A, Yamashita J, Ogawa T, Muramoto K. Purification and characterization of antioxidative peptides derived from rice bran protein hydrolysates. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;228(4):553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Agellon LB, Drover VA, Cheema SK, Gbaguidi GF, Walsh A. Dietary cholesterol fails to stimulate the human cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(23):20131–20134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) Official Methods of Analysis. 17. Washington DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beathice C, Pierre J, Carmen I, Elisabeth M, Christine F, Ludovic D, Anne-Marie F. Characterization of an antithrombotic peptide from α-casein in newborn plasma after milk ingestion. Br J Nutr. 1995;73(4):583–590. doi: 10.1079/bjn19950060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjakul S, Morrissey MT. Protein hydrolysates from Pacific whiting solid wastes. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45(9):3423–3430. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J-Y. Thrombin specificity. Eur J Biochem. 1985;151(2):217–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman DW (1981) Evolution of a new class of antihypertensive drugs. In: Horovitz ZP (ed) Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors: mechanisms of action and clinical implications. Urban & Schwarzenberg, p 19

- Fukudome S-I, Yoshikawa M. Opioid peptides derived from wheat gluten: their isolation and characterization. FEBS Lett. 1992;296(1):107–111. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80414-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ruiz JÁ, Ramos M, Recio I. Identification of novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides from ovine milk proteins by CE-MS and chromatographic techniques. Electrophoresis. 2007;28(22):4202–4211. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham IM, Daly LE, Refsum HM, Robinson K, Brattström LE, Ueland PM, Palma-Reis RJ, Boers GH, Sheahan RG, Israelsson B. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(22):1775–1781. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540460039030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R-Z, Li C-Y, Liu W-Y, Yi W-X, Cai M-Y. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of low-molecular-weight peptides from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) skin. Food Res Int. 2011;44(5):1536–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Guani-Guerra E, Santos-Mendoza T, Lugo-Reyes SO, Teran LM. Antimicrobial peptides: general overview and clinical implications in human health and disease. Clin Immunol. 2010;135(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzer T, Schlinzig T, Krohn K, Meinertz T, Münzel T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2673–2678. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T, Nonaka A, Matsushita A, Uchida N, Ohki K, Asakura M, Kitakaze M. Milk casein-derived tripeptides, VPP and IPP induced NO production in cultured endothelial cells and endothelium-dependent relaxation of isolated aortic rings. Heart Vessels. 2011;26(5):549–556. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, Bloch KD, Moskowitz MA, Bevan JA, Fishman MC. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377(6546):239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. Known knowns and known unknowns: risks associated with combination antithrombotic therapy. Thromb Res. 2008;123:S7–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella JE, Lokesh B, Stone RA. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and amelioration of cardiovascular disease: possible mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52(1):1–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klafke JZ, da Silva MA, Rossato MF, Trevisan G, Walker CIB, Leal CAM, Borges DO, Schetinger MRC, Moresco RN, Duarte MMF, Santos ARS, Viecili PRN, Ferreira J. Antiplatelet, antithrombotic, and fibrinolytic activities of Campomanesia xanthocarpa. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/954748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Zhou H, Qian H. Enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat gluten by proteases and properties of the resulting hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2007;102(3):759–763. [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Guo M, Hua Y, Cao D, Zhang C. Enzymatic preparation of immunomodulating hydrolysates from soy proteins. Biores Technol. 2008;99(18):8873–8879. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen H, Pihlanto A. Food-derived bioactive peptides-opportunities for designing future foods. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(16):1297–1308. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RI. Causes of the decrease in cardiovascular mortality. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54(5):7–13. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90850-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-H, Tian Y-G, Wang Y, Nie S-P, Xie M-Y, Zhu S, Wang C-Y, Zhang P. Characterization and in vitro antioxidation of papain hydrolysate from black-bone silky fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus Brisson) muscle and its fractions. Food Res Int. 2011;44(1):133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher TF. Imbalance of endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors? A new concept in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1990;3(4):317–330. doi: 10.1093/ajh/3.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KO, Budai K, Javitt NB. Cholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylation: evidence for two different enzymes. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama S, Nonaka I, Tanaka H. Inhibitory effects of enzymatic hydrolysates of collagen and collagen-related synthetic peptides on fibrinogen/thrombin clotting. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1993;1164(2):215–218. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90250-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaaki Y, Hiroyuki F, Nobuyuki M, Yasuyuki T, Taichi Y, Rena Y, Hirotaka T, Kyoya T. Bioactive peptides derived from food proteins preventing lifestyle-related diseases. BioFactors. 2000;12:143–146. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montserrat-de la Paz S, Rodriguez-Martin NM, Villanueva A, Pedroche J, Cruz-Chamorro I, Millan F, Millan-Linares MC. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective properties of wheat gluten protein hydrolysates in primary human monocytes. Foods. 2020;9:854. doi: 10.3390/foods9070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K, Kondo I, Kanamaru Y, Nagaoka S. A novel regulatory pathway for cholesterol degradation via lactostatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352(3):697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka S, Futamura Y, Miwa K, Awano T, Yamauchi K, Kanamaru Y, Tadashi K, Kuwata T. Identification of novel hypocholesterolemic peptides derived from bovine milk β-lactoglobulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281(1):11–17. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruimboom L, de Punder K. The opioid effects of gluten exorphins: asymptomatic celiac disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33:24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-015-0032-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian ZJ, Je JY, Kim SK. Antihypertensive effect of angiotensin i converting enzyme-inhibitory peptide from hydrolysates of Bigeye tuna dark muscle, Thunnus obesus. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55(21):8398–8403. doi: 10.1021/jf0710635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PR, Burney JD, Black KW, Zaloga GP. Effect of chain length on absorption of biologically active peptides from the gastrointestinal tract. Digestion. 1999;60(4):332–337. doi: 10.1159/000007679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsuna K, Chen J-R. Isolation and characterization of peptides with antioxidant activity derived from wheat gluten. Food Sci Technol Res. 2002;8(3):227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium and control of vascular function State of the Art lecture. Hypertension. 1989;13(6 Pt 2):658–667. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WG, Wang Z, Xu SY. A new method for determination of antithrombotic activity of egg white protein hydrolysate by microplate reader. Chin Chem Lett. 2007;18(4):449–451. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Yin Y, Zhao W, Wang F, Yu Y, Liu B, Liu J, Chen F. Characterization of ACE-inhibitory peptide associated with antioxidant and anticoagulation properties. J Food Sci. 2011;76(8):C1149–C1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.