Abstract

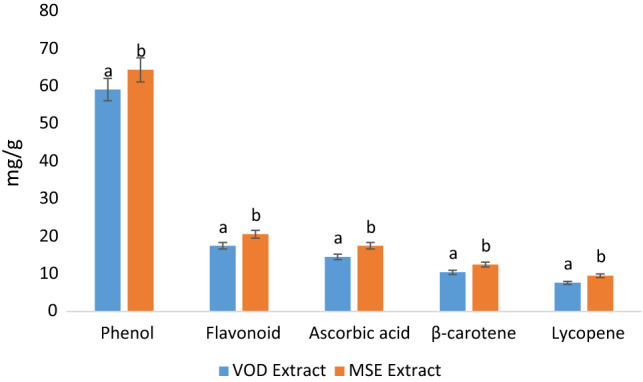

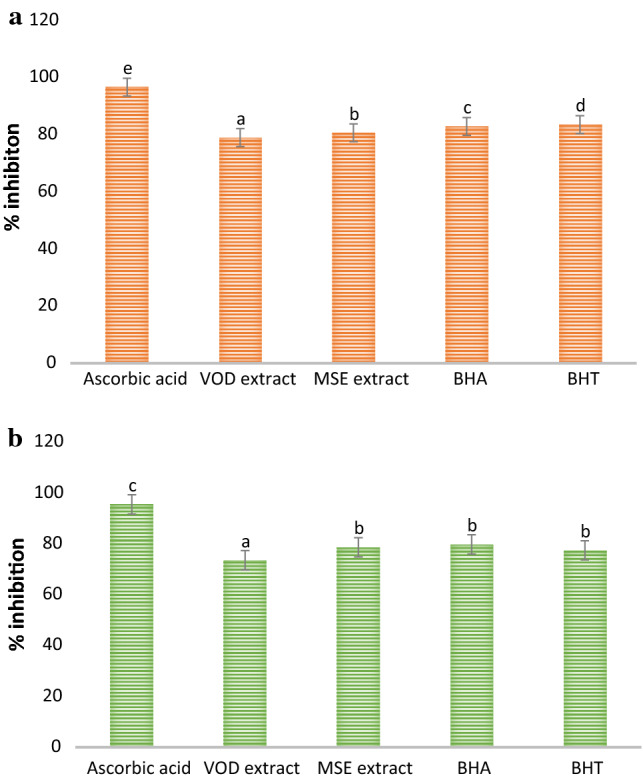

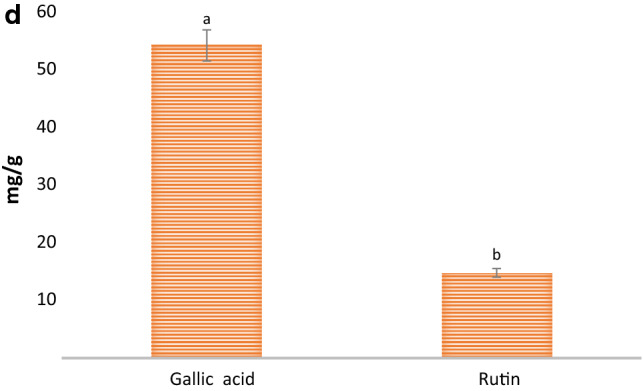

In the present study, we compared vacuum microwave oven drying Vacuum Oven Drying (VOD) and modified solvent evaporation (MSE) assisted methanolic mushroom extracts for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory efficacy. MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher total phenolic content (64.4 mg/g) followed by flavonoid content (20.62 mg/g), ascorbic acid (17.54 mg/g), β-carotene content (12.52 mg/g), and lycopene (9.57 mg/g) content than that of VOD extract. MSE showed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher zone of inhibition against all selected microorganisms as compared to VOD extract. During the time-kill study, the MSE extract inhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher growth of Staphylococcus aureus followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli than that of VOD extract. Also, MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher anti-inflammatory activity in comparison with VOD extract during the Human Red Blood Cell (HRBC) membrane stabilization test and albumin denaturation test. MSE extract revealed significantly (p < 0.05) higher 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and N2O2 scavenging assay than that of VOD extract, however, statistically, MSE extract showed comparable results with Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) and Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT). During the characterization of the selected extract, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy confirmed the functional groups of the flavonoid content, ascorbic acid, β-carotene, and lycopene. Quantitative analysis of gallic acid (54.32 mg/g) and rutin content (14.80 mg/g) was revealed using a high-pressure liquid chromatogram.

Keywords: Pleurotus floridanus, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), FTIR, Anti-inflammatory, Methanol

Introduction

Inflammation is considered as a physiological response against injury or harmful stimuli and is associated with diseases including endotoxemia and sepsis (Kamisoglu et al. 2015). In the human body, immune stimulant causes pro-inflammatory cells such as macrophages and monocytes to secrete inflammatory mediators whose uncontrolled production inside the body results in cell damage and initiation of inflammation process (Pasparakis et al. 2014). Therefore, to obviate the uncontrolled production of these mediators steroidal and nonsteroidal drugs have been recommended. Besides, efficient anti-inflammatory properties, these drugs have adverse effects on the human body and may lead to the development of gastric ulcers and irritation in tissues. Therefore, over the past years, plant extract-based natural components with potential anti-inflammatory activity have been used for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs (Elsayed et al. 2014). Furthermore, researchers and scientists had shown great interest to evaluate the bioactive components of various edible wild mushrooms.

Traditionally, several wild mushrooms have been used to cure various diseases. According to published reports, bioactive compounds isolated from mushrooms are vital natural products that have been studied for their effective anti-inflammatory activity to a large extent. These bioactive compounds include phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and lipid components (Barba et al. 2015). Along with anti-inflammatory properties, the bioactive compounds could have antimicrobial, antidiabetic, and anticancerous properties (Wasser 2017). The intake of foods rich in plant-based bioactive compounds and of functional foods can boost the immune system to help fight off viruses (Galanakis 2020). Consumer's requirements for healthy products are constantly changing and the demand for fresh and natural products with high nutritional value is increasing (Zinoviadou et al. 2015). Edible wild mushrooms are rich in proteins, fibers, and are low in fats therefore consumed for dietary and nutritional benefits (Ananey-Obiri et al. 2018). Among all edible wild mushrooms, Pleurotus floridanus commonly known as oyster belongs to the genus Pleurotus is a higher basidiomycete (Otieno et al. 2015). It is known to be the second most distributed edible mushroom worldwide. During the first world war, China introduces the culture of growing oyster mushrooms and its cultivation method was successfully developed by Germany to defeat hunger (Sekan et al. 2019). P. floridanus is highly nutritious and has a nutrient-rich dietary composition. The mushroom is rich in essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. (Carrasco-González et al. 2017). In addition to this, the mushroom has high protein, fiber, and carbohydrate contents therefore, it has importance in the agriculture and food industry. Bioactive components of P. floridanus characteristics of mushrooms are due to the presence of bioactive compounds, therefore extraction of bioactive compounds from mushrooms could be an effective approach to achieve the desirable results (Deng et al. 2015; Galanakis 2020). Several methodologies found in literature and five distinct recovery stages can principally be used, however, few steps are sometimes eliminated. Processing often initiates from the macroscopic to the macromolecular level and afterward to the extraction of specific bioactive compounds (Galanakis 2012). Various extraction methods have been reported for the extraction of the bioactive compounds, however, these methods may lead to auto-oxidation of the bioactive compounds (Kovačević et al. 2018). Therefore, to overcome this problem, the modified solvent evaporation (MSE) technique could be a better approach. In this process, at refrigerated temperature, polyphenolic components dispersed in methanol and molecules of methanol or organic solvent gather enough kinetic energy from its exchange with neighbor molecules to escape from the bonds with another molecule, hence molecules leave the mass of liquids and join the air as a vapor (Chawla et al. 2019; Bains and Chawla 2020). Therefore, the present study was carried out with the following objectives: (i) Collection of sample and preparation of extract from a mycelial culture of P. floridanus by vacuum microwave oven drying (VOD) and modified solvent evaporation technique, (ii) evaluation of physicochemical properties and comparative in vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of extract prepared from both technique, and (iii) bioactive components confirmation using High-pressure liquid chromatography technique.

Materials and methods

Pleurotus floridanus was collected from the forest of Bharusahib, Sirmour, Himachal Pradesh, India. The identification of the mushroom was confirmed using the conventional method. Media and ‘Analytical Reagent’ grade chemicals including Muller Hinton Agar, Malt extract broth, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, phosphate buffer, sodium chloride, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), L-ascorbic acid, diclofenac sodium salt, aluminum chloride, sodium carbonate, metaphosphoric acid, 2,6-dichlorophenol, 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl, α-naphthyl ethylenediamine, sulphanilic acid, phosphoric acid, methanol were procured from Hi-Media Private Limited, Mumbai, India. HPLC grade water, methanol, acetonitrile, gallic acid, and rutin were procured from Sigma Aldrich St. Louis, USA. Triple distilled water and acid-washed glassware were used during research experiments. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains i.e. Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 3160), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MTCC 424), Klebsiella pneumoniae (MTCC 3384), and Escherichia coli (MTCC 443), were obtained from the Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC), Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh, India.

Methods

Extraction of methanolic extract of P. floridanus

A sterile tissue was obtained from the fruiting body of the mushroom and cultured on a malt extract agar plate at 25 °C for 5 days to obtain mycelial culture, and after 5 days small square (about 5 × 5 mm in size) of mycelial culture from the mother plate were inoculated in 250 ml of conical flasks containing malt extract broth. These flasks were then incubated at 25 °C for 15 days to obtain the appropriate growth of the mushroom. The mycelial culture was filtered and kept for drying in a hot air oven to remove extra water at 30 °C. The dried culture was ground using a mechanical grinder (Bajaj High-Speed 950W, Chennai, India) and the powder was used for extract preparation. Herein, two methods were used for the evaporation of the solvent to obtain the extract of mushroom. For MSE extract preparation, the method proposed by (Chawla et al. 2019) was used, whereas, for VOD extract preparation, the proposed method of (Xie et al. 2017) was used. Briefly, a 10 g powdered mycelial sample was dispersed in 100 ml of absolute methanol in a conical flask and the mixture was kept in an orbital shaker (Orbitek LT, Scigenics Biotech Pvt. Ltd., Chennai, India) for 72 h. The sample was then filtered using Whatman no. 1 filter paper and methanol was evaporated (72 h) at refrigerated temperature (4–7 °C) to obtain MSE extract. For VOD extract, the solvent was evaporated using a vacuum oven (Laboratory deal VO, 4500). Both MSE and VOD extracts were collected in glass vials and stored at −20 °C for bioactivity analysis and characterization.

Total phenolic content of P. floridanus extract

Total phenolic content was evaluated according to the method described by (Sadh et al. 2018). A stock solution (10 mg/10ml) of VOD and MSE extracts was prepared in methanol and 200 μl MSE and VOD extract solution were properly mixed with 1 N Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1 ml) and 2 ml sodium carbonate (7.5%). The mixture was kept constant and undisturbed in dark condition for 30 min and absorbance was measured at 760 nm UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453). Gallic acid was used as a standard and a calibration curve was plotted using different concentrations of the gallic acid and total phenolic content was calculated GAE/g.

Estimation of flavonoid contents

The total flavonoid of MSE and VOD extract was calculated using aluminum chloride assay by following the proposed method (Bains and Tripathi 2017). Herein, a 2 ml MSE and VOD extract solution were mixed in the different test tubes with 5% sodium nitrite (200 μl) and kept undisturbed for 5 min. After that, 10% of aluminum chloride (200 μl) was added to the mixture and mixed properly using the vortex shaker. The reaction mixture was then kept constant for 6 min and 1 M NaOH (2 ml) was added to it. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was immediately measured at 510 nm using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer. Quercetin was used for the calibration curve and total flavonoid was calculated.

Estimation of ascorbic acid

The ascorbic acid content of MSE and VOD extract was calculated by the method proposed by (Klein and Perry 1982). Herein, a 100 mg of both the extract was mixed with 1% of metaphosphoric acid and kept undisturbed for 45 min at 30 °C. It was then filtered through Whatman no. 1 filter paper and the filtrate was mixed with 2,6-dichlorophenol. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 515 nm within 30 min. L-ascorbic acid was the standard curve to calculate the total amount of ascorbic acid.

Estimation of β-carotene and lycopene content

Briefly, 100 mg methanol extract of P. floridanus was dissolved in a 4:6 ratio of the acetone-hexane mixture (10 ml), and the test tube was kept undisturbed for 1 min at 30 °C. The mixture was then filtered through Whatman no. 4 filter paper and absorbance was measured at 453, 505, and 663 nm using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Nagata and Yamashita 1992).

Total β-carotene and lycopene content was measured by applying the following equations:

Antimicrobial properties

Antimicrobial susceptibility of methanol extract of P. floridanus was determined by the agar well diffusion method proposed by (Chawla et al. 2020). Herein, Muller Hinton agar plates were prepared and inoculated with test microorganisms (1.5 × 108 cells/ml approximately) i.e. S. aureus (MTCC 3160), P. aeruginosa (MTCC 424), K. pneumoniae (MTCC 3384), and E. coli (MTCC 443). The agar plates allowed to solidify and 6 mm wells were made by using a cork borer. Both MSE and VOD extract (25 μl) dissolved in 5% DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) was added into the agar wells. DMSO and antibiotic ciprofloxacin were taken as the negative and positive control. The plates were kept at 37 °C for 24 h and the zone inhibition (mm) against pathogenic microorganisms was measured to evaluate the antimicrobial efficiency of VOD and MSE extracts.

Time kill study

A time-kill study for VOD and MSE extracts was conducted by following the method proposed by (Majeed et al. 2016). Muller Hinton agar plates were prepared as mentioned in the previous section and a 100 μl of the VOD and MSE extract solution was taken after a time interval of 0, 18, 24, and 48 h. Serial dilution of the sample was done and then spread on plates containing Muller-Hinton agar. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h and Log CFU/ml was calculated.

In-vitro anti-inflammatory efficacy

HRBC membrane stabilization assay

For the HRBC membrane stabilization assay, blood (5 ml) was collected from a healthy human volunteer who did not intake NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) for 2 weeks. The blood was dissolved in an equal volume of sterilized Alsever solution (20.5 g Dextrose, 8 g sodium citrate, 0.55 g citric acid, and 4.2 g sodium chloride in 1000 ml water) and was then centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min. After centrifugation packed cells were obtained, washed with isosaline. The assay mixture that contains 500 μl mushroom extract, 1 ml 0.15 M phosphate buffer with pH 7.4, 2 ml 0.36% hyposaline solution, and 500 μl HRBC suspension was prepared. This assay mixture was then incubated in the Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) incubator at 37 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min. Diclofenac sodium was used as a positive control and distilled water was used as a negative control. The supernatant containing content of hemoglobin was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 560 nm using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Bains and Tripathi 2017). Anti-inflammatory activity was calculated as follows:

Albumin denaturation assay

To perform albumin denaturation, a volume of 5 ml of the reaction mixture was prepared including 200 μl of fresh egg albumin, 2.8 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH6.4), and 2 ml of VOD and MSE extract. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C in the BOD incubator for 15 min followed by heating up to 70 °C for 5 min and absorbance was measured at 660 nm. Diclofenac sodium was used as a positive control and deionized water was taken as control. Albumin denaturation percentage inhibition was calculated as follows:

here, VT is the absorbance of the test sample and VC is the absorbance of the control (Bains and Tripathi 2017).

Antioxidant assay

DPPH free radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activity of VOD and MSE extracts was determined by following the method of (Sadh et al. 2018). Briefly, 200 μl methanol extract of mushroom was added in 2 ml of 0.1 mM DPPH solution in a test tube and the mixture was then kept in dark condition for 30 min. After 30 min of incubation change in DPPH color from purple to pale yellow was observed and absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV–Visible spectrophotometer. The percentage of free radical scavenging activity was calculated as:

where Ay is the absorbance of the solution and Az is the absorbance of the control (DPPH solution).

Nitric oxide scavenging assay

The nitrite detection assay was performed by following the proposed method (Bains and Tripathi 2017). Briefly, a 5 ml sodium nitroprusside (10 mM) was dissolved in 5 ml 0.5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and it was used as a chemical source of nitric oxide. The solution was added with a 0.5 ml Griess reagent (1:1 ratio of α-naphthyl ethylenediamine 0.1% in water and sulphanilamide 1% in 5% H3PO4) after incubation at 37 °C for 5 h. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 546 nm.

where As is the absorbance of the solution and At is the absorbance of control.

Characterization of extract

Based upon better bioactivity MSE extract was further selected for characterization. FTIR and HPLC techniques were used for further characterization of MSE extract. Functional groups present in MSE extract, it was evaluated by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (Agilent Technologies, Mumbai, India). Herein, 5 mg of the sample was kept on the mirror stage of the FTIR spectrometer and the lens was tightened over the sample. Spectra were obtained at mid-infrared region 4000–600 cm−1 using air as background and data thus obtained in terms of transmittance (55 scans). A high-pressure liquid chromatography technique was used for the quantification of bioactive compounds present in MSE extract. The quantification of gallic and rutin in the MSE extract was carried out using the HPLC technique. Herein, 25 mg of mushroom extract was dissolved in methanol in a 100 ml flask and kept in an orbital shaker for 20 min, after 20 min the sample was filtered through Whatman filter paper and used for further analysis. The HPLC system (Water 515) consisted of a manual injector, a high gradient binary pump system, and a temperature-controlled column chamber. The detection and quantification of phenol and flavonoids were done by using 2998 Photodiode Array Detector. The data thus obtained was collected and analysis was done using Empower2 software. The analytic column C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 33 cm) column (Waters) with a flow rate of 60 ml/h was employed for analysis of gallic acid and rutin. The quantification of rutin and gallic acid present in the MSE extract was done at 357 and 272 nm (Kaushik et al. 2014).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for the obtained results was carried out by following the method proposed by Kaushik et al, (Kaushik et al. 2018). Microsoft excel office, 2016 was used to calculate the standard error mean. Statistical difference was calculated using a one-way analysis of variance and comparison between mean was calculated by difference value.

Results and discussion

Bioactive compounds estimation

The yield of the extract is an important characteristic that can directly correlate with the bioactivity of the extract. In our research, we obtained a significantly higher yield of MSE extract (5.35%) in comparison with VOD extract (4.13%). MSE extract was obtained in 72 h, whereas we obtained VOD extract in 8 h. The quantification of phenolic compounds, flavonoid, ascorbic acid, and lycopene was carried out using the spectrophotometric technique, and results are represented in (Fig. 1). Herein, the MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher total phenolic content (64.4 mg/g), flavonoid content (20.62 mg/g), ascorbic acid (17.54 mg/g), β-carotene content (12.52 mg/g), and lycopene (9.57 mg/g) as compared to total phenolic (59.12 mg/g), flavonoid (17.53 mg/g), Ascorbic acid (14.56 mg/g), β-carotene (10.45 mg/g), and lycopene content (7.66 mg/g) of VOD extract. The reduction of bioactive compounds of VOD extract could be due to the activation of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase enzymes. These enzymes are oxidative enzymes and their activation cause changes in the structure of phenolic compounds (Toor and Savage 2006; An et al. 2016). Therefore, it can be concluded that the VOD extract altered its chemical composition of bioactive compounds. Results were in accordance with the findings of (Bains and Chawla 2020) who revealed total phenolic content (48.71 mg/g), total flavonoid content (13.13 mg/g), ascorbic acid content (11.03 mg/g), β-carotene content (8.34), and lycopene content (6.85) of modified solvent evaporation assisted methanolic extract of Trametes versicolor.

Fig. 1.

Total phenol, flavonoid, ascorbic acid content, total β-carotene, and lycopene content of VOD and MSE extract of P. floridanus

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity of VOD and MSE extract were evaluated against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms and results are represented in Fig. 2. Both MSE and VOD reagent showed antimicrobial properties against the selected microorganisms in terms of zone of inhibition. Herein, MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher zone of inhibition ranged from 24.25 to 28.35 mm in comparison with VOD extract against all pathogenic bacteria that ranged from 21.03 to 24.06 mm. MSE extract at refrigerated temperature retained a higher number of bioactive components as compared to VOD extract, hence showed effective antimicrobial activity (Chawla and Bains 2020). Moreover, both MSE and VOD extract showed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher zone of inhibition against Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus whereas, whereas both the extracts showed significantly (p < 0.05) lower zone of inhibition for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa. Being a Gram-positive microorganism S. aureus consists of membrane-bounded periplasm that is present in its cell membrane (consisting of peptidoglycan composed of techoic and teichuronic acid), therefore both the extract were highly effective against the growth of test microorganisms. Furthermore, the outer cell wall of S. aureus is a formulation of a thick hydrophobic structure in which a large number of proteins and lipids can bind. This porous membrane could be the reason for the increased permeability of peptidoglycans of mushrooms and other bioactive agents. On the other hand, the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria contains lipopolysaccharides, these lipopolysaccharides don't allow any chemotherapeutic or bioactive components to pass through it hence act as an effective permeability barrier (Chawla et al. 2020). Furthermore, (Appiah et al. 2017) observed similar trends from mushroom extract against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, hence, the present results were in accordance with their findings.

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial activity of MSE and VOD extracts of P. floridanus showing zone of inhibition against pathogenic microorganisms

Time kill study

The time-kill study of the VOD and MSE extract was performed and the results are represented in Fig. 3a, b. Both VOD and MSE extracts showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher inhibition in the growth S. aureus as compared to P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli with increasing time interval. However, with increasing time interval, MSE extract showed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher killing effect than that of VOD extract against all microorganisms. Herein, S. aureus showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher reduction in the log CFU/ml values (from 8.46 to7.94 and 8.45 to 7.81), whereas, in case of in the case of P. aeruginosa log CFU/ml was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced from 8.46 to 8.01 and 8.43 to 7.93, in the case of E. coli log CFU/ml significantly (p < 0.05) reduced from 8.42 to 8.05, and 8.42 to 7.92 in the case of K. pneumoniae log CFU/ml significantly (p < 0.05) reduced from 8.44 to 8.03 and 8.44 to 7.96. However, all Gram-negative microorganisms showed non-significant (p < 0.05) differences with each other in terms of the killing of microorganisms with respect to increasing time. The S. aureus consists of a peptidoglycan layer permeable to antibiotics and mushroom peptidoglycans which results in the denaturation of proteins and disruption in the cell membrane, therefore, showed the least colony count upon treatment with both VOD and MSE extracts. However, in the case of P. aeruginosa the log CFU/ml value was significantly higher than that of other organisms due to the efflux mechanism in which antibiotic components get flushed out (Chika et al. 2016). The present results were in line with the findings of (Tinrat 2015; Appiah et al. 2017) who observed the time-kill effect of Schizophyllum commune, Trametes gibbosa, Trametes elegans, S. commune, Volvariella volvacea, Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, Hypsizygus tesselltus and Flamullina velutipes against E. coli, S. aureus, Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella typhimurium.

Fig. 3.

Antimicrobial activity of (a) VOD and (b) MSE extract and extract of P. floridanus against pathogenic microorganism

Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity VOD and MSE extract were evaluated and the results are represented in Fig. 4a, b. Here, all concentrations of L-Ascorbic acid showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher percentage inhibition in comparison with varying concentrations of BHA, BHT, MSE, and VOD extract. Furthermore, the MSE extract showed a high percentage inhibition for DPPH (80.65%) and N2O2 (78.57%) as compared to the VOD extract (78.97% and 73.57%). MSE extract at refrigerated temperature retained a higher number of bioactive components as compared to VOD extract, hence showed effective antimicrobial activity (Chawla and Bains 2020). Statistically, MSE extract and synthetic antioxidants showed a non-significant (p < 0.05) difference in terms of percentage inhibition during DPPH and N2O2 scavenging assay. The ability of MSE extract was similar to that of artificial antioxidant BHT and BHA. Therefore, if a pure form of bioactive compounds gets isolated they may show more effective results than that of control (Olugbami et al. 2015). These results were in agreement with the study of (Reid et al. 2017; Sim et al. 2017; Liaotrakoon and Liaotrakoon 2018).

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant activity of MSE and VOD extract of P. floridanus by (a) DPPH free radical scavenging assay and (b) nitric oxide free radical scavenging assay

Anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of VOD and MSE extract was carried out by HRBC membrane stabilization and albumin denaturation assay as shown in Fig. 5a, b. Diclofenac sodium salt was used as a standard and anti-inflammatory activity of VOD and MSE was compared with it. During membrane stabilization and protein denaturation assay, a significant (p < 0.05) difference was observed in the anti-inflammatory activity of VOD and MSE extract. The MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher percentage stabilization and percentage inhibition in comparison with VOD extract. However, all concentrations of diclofenac sodium showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher percentage stabilization and percentage inhibition in comparison with varying concentrations of both extracts. The MSE extract VOD extract showed percentage stabilization 79.82% and 76.62% for the HRBC membrane stabilization test respectively, and 78.35% and 74.24% respectively for the albumin denaturation test. Diclofenac sodium salt showed higher percent stabilization 91.62% for HRBC stabilization and 92.58%, respectively for albumin denaturation test. Mushroom extracts exert anti-inflammatory activity due to the presence of glycopeptides and other bioactive compounds. The present results were in line with the findings of (Bains and Tripathi 2017; Bains and Chawla 2020) who observed efficient results of the anti-inflammatory activity of P. ostreatus, T. versicolor, P. floridanus, Calocybe indica, Mycrocybe sp, and Agrocybe agerita.

Fig. 5.

Effect of MSE and VOD extract of P. floridanus on (a) membrane stabilization and (b) and on albumin denaturation

Characterization of MSE extract

The characterization of the MSE extract was done as it showed enhanced biological activities as compared to VOD extract. The functional groups present in bioactive compounds were confirmed by FTIR and results are shown in Fig. 6a. Here, the vibrational stretching of the phenolic-OH group was confirmed at 3264 cm−1. The stretching at 1640 cm−1 was due to C=C vibrations of the conjugated double bond and at 1380 cm−1, 2925.76 cm−1 of carotenoid was due to C–H bending (Rubio-Diaz et al. 2011). The stretching of ascorbic acid was confirmed at 1745 cm−1 which was due to the stretching vibration of C=O of a five-membered lactone ring (Khatua et al. 2015). The vibrational band at 2854.72 cm−1 confirmed the presence of a pyranose ring. Also, stretching at 892 cm−1 revealed the presence of β-glycosidic linkage. Furthermore, stretching at 1313 cm−1 and 1547 cm−1 confirmed the presence of secondary amines (N–H bending), whereas H–C–H symmetric or asymmetric stretch indicated the presence of alkanes (Andrew et al. 2018). The vibrational band at 1153 cm−1 attributes to the presence of glycosidic bonds (Thenmozhi et al. 2013). HPLC analysis of the MSE extract of P. floridanus was carried out for the quantification of rutin and gallic acid. HPLC chromatogram of gallic acid and rutin present in the extract showed a sharp peak with retention time 2.017 and 1.909 min, respectively as shown in (Fig. 6b, c, d). Herein, HPLC chromatogram revealed significantly (p < 0.05) higher gallic acid content (54.32 mg/g) as compared to rutin content (14.80 mg/g). Therefore, it was concluded from the study that spectra obtained from FTIR and HPLC chromatogram of MSE extract support and justified the presence of different bioactive components and their biological activities (Khatua et al. 2015).

Fig. 6.

(a) FTIR spectra (b) HPLC chromatogram of gallic acid, (c) rutin, and (d) quantitative analysis of gallic acid and rutin of MSE extract of P. floridanus

Conclusion

In the present study, VOD and modified solvent evaporation (MSE) assisted methanolic mushroom extracts were compared for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory efficacy. MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher total phenolic content followed by flavonoid content, ascorbic acid, β-carotene content, and lycopene content than that of VOD extract. MSE showed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher zone of inhibition against all selected microorganisms as compared to VOD extract. During the time-kill study, the MSE extract inhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher growth of S. aureus followed by P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli than that of VOD extract. Also, MSE extract showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher anti-inflammatory activity in comparison with VOD extract during the HRBC membrane stabilization test and albumin denaturation test. MSE extract revealed significantly (p < 0.05) higher DPPH and N2O2 scavenging assay than that of VOD extract, however, statistically, MSE extract showed comparable results with BHA and BHT. During the characterization of the selected extract, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy confirmed the functional groups of the flavonoid content, ascorbic acid, β-carotene, and lycopene. Quantitative analysis of gallic acid and rutin content was revealed using a high-pressure liquid chromatogram.

Acknowledgment

The authors are gratefully acknowledged to Shoolini University, Solan, Himachal Pradesh.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest between the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aarti Bains, Email: aarti05888@gmail.com.

Prince Chawla, Email: princefoodtech@gmail.com.

Astha Tripathi, Email: astha4u@gmail.com.

Pardeep Kumar Sadh, Email: pardeep.sadh@gmail.com.

References

- An K, Zhao D, Wang Z, Wu J, Xu Y, Xiao G. Comparison of different drying methods on Chinese ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): changes in volatiles, chemical profile, antioxidant properties, and microstructure. Food Chem. 2016;197:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananey-Obiri D, Matthews L, Azahrani MH, Ibrahim SA, Galanakis CM, Tahergorabi R. Application of protein-based edible coatings for fat uptake reduction in deep-fat fried foods with an emphasis on muscle food proteins. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;80:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew K, Andrew KA, Thomas M, Pesterfield A, Lineberry Q, Steinfelds EV (2018). Raman detection threshold measurements for acetic acid in martian regolith simulant JSC-1 in the presence of hydrated metallic sulfates. Preprint arXiv:1801.06870

- Appiah T, Boakye YD, Agyare C. Antimicrobial activities and time-kill kinetics of extracts of selected ghanaian mushrooms. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4534350. doi: 10.1155/2017/4534350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains A, Chawla P. In vitro bioactivity, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory efficacy of modified solvent evaporation assisted Trametes versicolor extract. 3 Biotech. 2020;10(9):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02397-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains A, Tripathi A. Evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of aqueous extract of wild mushrooms collected from Himachal Pradesh. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(3):467. [Google Scholar]

- Barba FJ, Galanakis CM, Esteve MJ, Frigola A, Vorobiev E. Potential use of pulsed electric technologies and ultrasounds to improve the recovery of high-added value compounds from blackberries. J Food Eng. 2015;167:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-González JA, Serna-Saldívar SO, Gutiérrez-Uribe JA. Nutritional composition and nutraceutical properties of the Pleurotus fruiting bodies: potential use as food ingredient. J Food Compos Anal. 2017;58:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla P, Kumar N, Kaushik R, Dhull SB. Synthesis, characterization and cellular mineral absorption of nanoemulsions of Rhododendron arboreum flower extracts stabilized with gum arabic. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(12):5194–5203. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03988-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla P, Kumar N, Bains A, Dhull SB, Kumar M, Kaushik R, Punia S. Gum arabic capped copper nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;146:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chika E, Charles E, Ifeanyichukwu I, Chigozie U, Chika E, Carissa D, Michael A. Phenotypic detection of AmpC beta-lactamase among anal Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in a Nigerian abattoir. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2016;7(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Zinoviadou KG, Galanakis CM, Orlien V, Grimi N, Vorobiev E, et al. The effects of conventional and non-conventional processing on glucosinolates and its derived forms, isothiocyanates: extraction, degradation, and applications. Food Eng Rev. 2015;7(3):357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed EA, El Enshasy H, Wadaan MA, Aziz R. Mushrooms: a potential natural source of anti-inflammatory compounds for medical applications. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014:805841. doi: 10.1155/2014/805841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis CM. Recovery of high added-value components from food wastes: conventional, emerging technologies and commercialized applications. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2012;26(2):68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis CM. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods. 2020;9(4):523. doi: 10.3390/foods9040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisoglu K, Haimovich B, Calvano SE, Coyle SM, Corbett SA, Langley RJ, et al. Human metabolic response to systemic inflammation: assessment of the concordance between experimental endotoxemia and clinical cases of sepsis/SIRS. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0783-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik R, Sachdeva B, Arora S, Wadhwa BK. Development of an analytical protocol for the estimation of vitamin D2 in fortified toned milk. Food Chem. 2014;151:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik R, Chawla P, Kumar N, Janghu S, Lohan A. Effect of premilling treatments on wheat gluten extraction and noodle quality. Food Sci Technol Int. 2018;24(7):627–636. doi: 10.1177/1082013218782368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatua S, Dutta AK, Acharya K. Prospecting Russula senecis: a delicacy among the tribes of West Bengal. PeerJ. 2015;3:e810. doi: 10.7717/peerj.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BP, Perry AK. Ascorbic acid and vitamin A activity in selected vegetables from different geographical areas of the United States. J Food Sci. 1982;47(3):941–945. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević DB, Barba FJ, Granato D, Galanakis CM, Herceg Z, Dragović-Uzelac V, Putnik P. Pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE) for the green recovery of bioactive compounds and steviol glycosides from Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni leaves. Food Chem. 2018;254:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaotrakoon W, Liaotrakoon V. Influence of drying process on total phenolics, antioxidative activity and selected physical properties of edible bolete (Phlebopus colossus (R. Heim) Singer) and changes during storage. Food Sci Technol. 2018;38(2):231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed H, Liu F, Hategekimana J, Sharif HR, Qi J, Ali B, et al. Bactericidal action mechanism of negatively charged food grade clove oil nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2016;197:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata M, Yamashita I. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi. 1992;39(10):925–928. [Google Scholar]

- Olugbami JO, Gbadegesin MA, Odunola OA. In vitro free radical scavenging and antioxidant properties of ethanol extract of Terminalia glaucescens. Pharm Res. 2015;7(1):49. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.147200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otieno OD, Onyango C, Onguso JM, Matasyoh LG, Wanjala BW, Wamalwa M, Harvey JJ. Genetic diversity of Kenyan native oyster mushroom (Pleurotus) Mycologia. 2015;107(1):32–38. doi: 10.3852/13-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis M, Haase I, Nestle FO. Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(5):289–301. doi: 10.1038/nri3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid T, Merjury M, Takafira M. Effect of cooking and preservation on nutritional and phytochemical composition of the mushroom Amanita zambian. Food Sci Nutr. 2017;5(3):538–544. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Diaz DE, Francis DM, Rodriguez-Saona LE. External calibration models for the measurement of tomato carotenoids by infrared spectroscopy. J Food Compos Anal. 2011;24(1):121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sadh PK, Chawla P, Duhan JS. Fermentation approach on phenolic, antioxidants and functional properties of peanut press cake. Food Biosci. 2018;22:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sekan AS, Myronycheva OS, Karlsson O, Gryganskyi AP, Blume Y. Green potential of Pleurotus spp. in biotechnology. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6664. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim KY, Liew JY, Ding XY, Chddng WS, Intan S. Effect of vacuum and oven drying on the radical scavenging activity and nutritional contents of submerged fermented Maitake (Grifola frondosa) mycelia. Food Sci Technol. 2017;37(1):131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Thenmozhi N, Gomathi T, Sudha P. Preparation and characterization of biocomposites: Chitosan and silk fibroin. Pharm Lett. 2013;5(4):88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tinrat S. Antimicrobial activities and synergistic effects of the combination of some edible mushroom extracts with antibiotics against pathogenic strains. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2015;35(2):253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Toor RK, Savage GP. Effect of semi-drying on the antioxidant components of tomatoes. Food Chem. 2006;94(1):90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wasser SP. Medicinal mushrooms in human clinical studies. Part I. Anticancer, oncoimmunological, and immunomodulatory activities: a review. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2017;19(4):279–317. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v19.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Zhu D, Zhang W, Huai W, Wang K, Huang X, et al. Microwave-assisted aqueous two-phase extraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography for simultaneous extraction and determination of four flavonoids in Crotalaria sessiliflora L. Ind Crop Prod. 2017;95:632–642. [Google Scholar]

- Zinoviadou KG, Galanakis CM, Brnčić M, Grimi N, Boussetta N, Mota MJ, et al. Fruit juice sonication: implications on food safety and physicochemical and nutritional properties. Food Res Int. 2015;77:743–752. [Google Scholar]