Abstract

Objectives

The objective of COAST-Y was to evaluate the effect of continuing versus withdrawing ixekizumab (IXE) in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) who had achieved remission.

Methods

COAST-Y is an ongoing, phase III, long-term extension study that included a double-blind, placebo (PBO)-controlled, randomised withdrawal-retreatment period (RWRP). Patients who completed the originating 52-week COAST-V, COAST-W or COAST-X studies entered a 24-week lead-in period and continued either 80 mg IXE every 2 (Q2W) or 4 weeks (Q4W). Patients who achieved remission (an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)<1.3 at least once at week 16 or week 20, and <2.1 at both visits) were randomly assigned equally at week 24 to continue IXE Q4W, IXE Q2W or withdraw to PBO in a blinded fashion. The primary endpoint was the proportion of flare-free patients (flare: ASDAS≥2.1 at two consecutive visits or ASDAS>3.5 at any visit) after the 40-week RWRP, with time-to-flare as a major secondary endpoint.

Results

Of 773 enrolled patients, 741 completed the 24-week lead-in period and 155 entered the RWRP. Forty weeks after randomised withdrawal, 83.3% of patients in the combined IXE (85/102, p<0.001), IXE Q4W (40/48, p=0.003) and IXE Q2W (45/54, p=0.001) groups remained flare-free versus 54.7% in the PBO group (29/53). Continuing IXE significantly delayed time-to-flare versus PBO, with most patients remaining flare-free for up to 20 weeks after IXE withdrawal.

Conclusions

Patients with axSpA who continued treatment with IXE were significantly less likely to flare and had significantly delayed time-to-flare compared with patients who withdrew to PBO.

Keywords: spondylitis, ankylosing, biological therapy, antirheumatic agents, immune system diseases

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Results from randomised withdrawal studies of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) suggest that discontinuation of TNFi leads to flare in most patients and continuous treatment may be important for maintaining disease control.

However, no studies have evaluated the effect of continuing versus withdrawing an interleukin (IL)-17A antagonist in patients with axSpA.

Ixekizumab (IXE), a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets IL-17A, is an efficacious treatment for the management of axSpA, including radiographic and non-radiographic axSpA.

What does this study add?

COAST-Y is the first study to compare the maintenance of disease control in patients with axSpA who continued versus those who withdrew an IL-17A antagonist (IXE) after having achieved remission.

In patients with axSpA, continuous IXE treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of maintaining optimal disease control compared with IXE withdrawal.

A substantial proportion of patients remained flare-free through 40 weeks of IXE withdrawal and most patients remained flare-free for up to 20 weeks of IXE withdrawal.

Key messages.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

The findings of COAST-Y show that continuous IXE treatment is important for the maintenance of optimal disease control.

A substantial proportion of patients remained flare-free for a prolonged period following IXE withdrawal, which may be important in situations where temporary treatment interruption is necessary or preferred.

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that predominantly affects the axial skeleton.1 AxSpA is categorised as radiographic (r-axSpA, also known as ankylosing spondylitis) or non-radiographic (nr-axSpA) axSpA by the presence or absence of definite radiographic sacroiliitis, respectively.2 AxSpA carries a high disease burden and generally requires long-term therapy to maintain disease control.3 4

Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) and interleukin (IL)-17A antagonists, are recommended for patients with persistently high disease activity refractory to, or intolerant of, conventional treatment with at least two non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4 Inactive disease/remission or low disease activity has been proposed as a treatment target for axSpA.5 There is considerable interest in the durability of bDMARDs’ efficacy following withdrawal or dose reduction in patients who have achieved stable disease control. Previous randomised withdrawal studies of TNFi indicated that complete withdrawal of TNFi significantly increased the likelihood of flare.6–9 However, a reduced dosing frequency of certolizumab pegol resulted in maintenance of disease control with no significantly greater chance of flare.6 In contrast, the maintenance of disease control following withdrawal of IL-17A antagonists has not yet been evaluated.

Ixekizumab (IXE), a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets IL-17A, is approved for r-axSpA and nr-axSpA. In three phase III studies, IXE provided sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of r-axSpA and nr-axSpA through 52 weeks of treatment.10–13 The primary objective at week 64 of the current extension study was to compare the maintenance of disease control in patients who continued IXE versus those who withdrew IXE following achievement of axSpA clinical remission.

Methods

Patients

COAST-Y (NCT03129100) included participants from two originating studies in r-axSpA (COAST-V, NCT02696785; and COAST-W, NCT02696798) and one originating study in nr-axSpA (COAST-X, NCT02757352). Eligibility criteria for the originating studies are published.10 13 Patients eligible for COAST-Y must have completed the final week-52 visit in the originating study without permanently discontinuing investigational product. Patients with a significant uncontrolled safety concern that had developed during the originating study were excluded if the investigator considered it an unacceptable risk to the patient to continue investigational product. However, the investigational product could be resumed and the patient could be enrolled into COAST-Y if the patient recovered from the safety concern within 12 weeks of completing the originating study. Complete eligibility criteria are provided in the online supplemental appendix.

annrheumdis-2020-219717supp001.pdf (358.3KB, pdf)

Study design

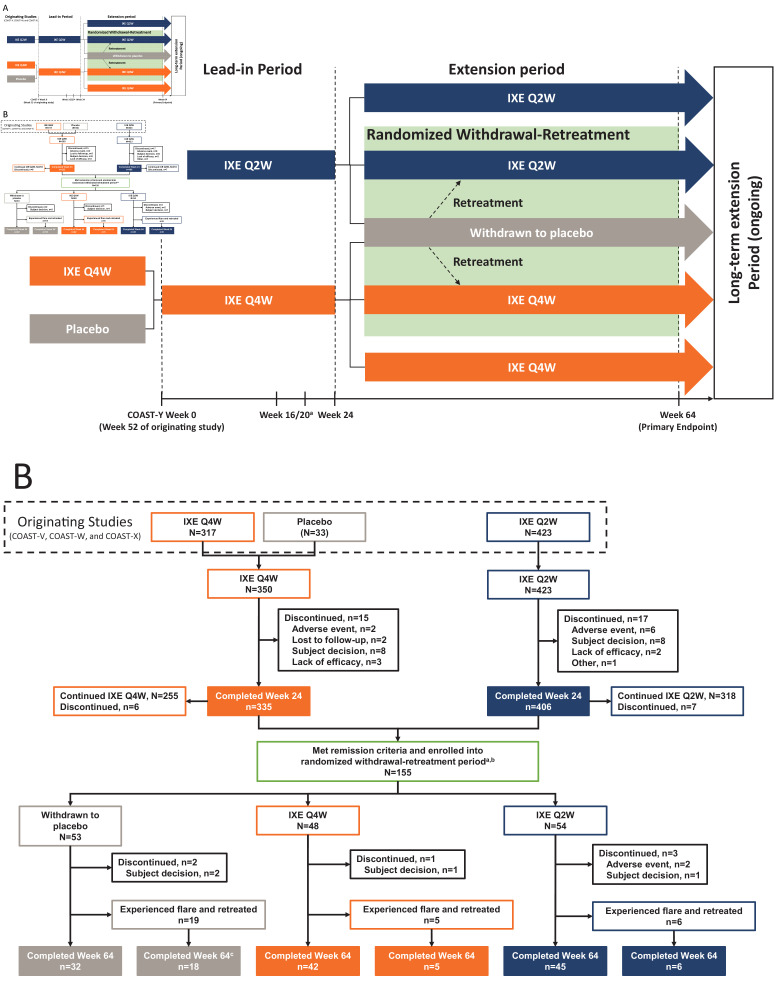

COAST-Y is an ongoing, 104-week, phase III, multicentre, long-term extension study that included an open-label lead-in period and a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal-retreatment period (RWRP) (figure 1A). Patients entered a 24-week lead-in period (weeks 0–24) and continued either 80 mg IXE every 2 weeks (Q2W) or every 4 weeks (Q4W). Patients who completed COAST-X and who were receiving blinded placebo were assigned to IXE Q4W.

Figure 1.

COAST-Y study design (A) and patient flow diagram through week 64 of COAST-Y (B). Treatment groups from the originating studies indicate the assigned treatments at the final visit (week 52) of the originating studies. In addition, patient numbers from the originating studies include only those who entered the lead-in period of COAST-Y. The 33 patients receiving placebo at week 52 of the originating studies were from COAST-X. aPatients were eligible for entering the randomised withdrawal-retreatment period at week 24 if they achieved an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) of <1.3 at least once during study visits at week 16 or week 20 and <2.1 at both visits. bA total of 157 patients met the remission criteria at week 20, but 2 patients discontinued prior to randomisation at week 24. cOne patient in the withdrawn to placebo group who experienced a flare and was retreated discontinued for reason of ‘subject decision’. IXE, ixekizumab; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks.

Patients completing the lead-in period entered a 40-week (weeks 24–64) extension period, which included the RWRP. At week 24, patients who achieved remission, defined as an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) of <1.3 at least once at week 16 or week 20 and <2.1 at both visits, were randomly assigned in equal proportions to continue IXE Q4W, continue IXE Q2W or withdraw to placebo. Specifically, patients in each treatment group (IXE Q4W or IXE Q2W) were randomised in a 2:1 ratio to continue their assigned IXE dosing regimen or to withdraw to placebo, respectively, resulting in an overall 1:1:1 randomisation ratio. Visits during the RWRP occurred every 4 weeks from week 24 to week 64.

Patients who experienced a flare (ASDAS≥2.1 at two consecutive visits or ASDAS>3.5 at any visit) were retreated at the next visit with the same IXE dosing regimen received during the lead-in period but in an open-label fashion, except for patients originally from COAST-X, who received blinded retreatment until the COAST-X week-52 database lock. Additional details on the study design are summarised in the online supplemental appendix.

Study participants provided written informed consent prior to starting study procedures.

Outcomes

The primary outcome at week 64 was the proportion of flare-free patients during the RWRP in the combined IXE group (Q4W and Q2W combined) versus the withdrawn to placebo group. Major secondary outcomes at week 64 included the proportion of flare-free patients in the IXE Q4W group versus withdrawn to placebo group and, in the combined IXE and IXE Q4W groups, the time-to-flare versus the withdrawn to placebo group.

Other secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients at week 64 who maintained response as measured by Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria, ASDAS and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). Categorical outcomes included ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS Partial Remission, ASAS 5/6, ASDAS inactive disease (ID), ASDAS low disease activity (LDA) and BASDAI 50.14–19 Continuous outcomes included the mean change from baseline in ASDAS, BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) in mg/L and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary. Secondary outcomes also included the proportion of patients who achieved ASDAS LDA within 16 weeks of retreatment.

Post hoc assessments were conducted to evaluate predictors of flare during the RWRP. MRI of the sacroiliac joint and spine was conducted at week 24 for patients who qualified for the RWRP to evaluate residual inflammation on MRI as a predictive variable for flare. A post hoc assessment was also conducted to evaluate the proportion of patients who did not meet the ASAS definition of clinically important worsening (ASDAS worsening of ≥0.9) since week 24.20

Safety evaluations included laboratory tests, vital signs, physical examination findings and adverse events (AEs), including treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), serious AEs (SAEs) and AEs of special interest. Data associated with cerebrocardiovascular events or suspected inflammatory bowel disease were adjudicated by an external clinical events committee. Additional details regarding efficacy and safety outcomes are provided in the online supplemental appendix.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy analyses were conducted on the randomised withdrawal intent-to-treat (RW ITT) population, defined as all patients who achieved remission and entered the RWRP. Categorical efficacy variables were analysed using logistic regression with treatment group, geographic region and originating study as factors with non-responder imputation used for handling missing data. Continuous efficacy variables were analysed using analysis of covariance with treatment, COAST-Y week-24 value, baseline (week 0 of the originating study) value, geographical region and originating study included in the model with modified baseline observation carried forward used for handling missing data. Type III sums of squares for the least squares means were used for treatment group comparisons of continuous variables. Baseline for efficacy and health outcomes analyses was defined as the last available value before the first dose of study treatment from the originating study and, in most cases, was the value recorded at week 0 from the originating study.

The Kaplan-Meier product limit method was used to estimate the survival curves for time-to-flare and the log-rank test with strata of geographical region and originating study was used for treatment group comparisons. Flare-free patients who completed the treatment period were censored at the date of completion of the analysis period and patients who discontinued were censored at the date of the last dose or the date of the last attended visit in the treatment period (whichever was later).

Among patients who experienced a flare and were retreated with open-label IXE, the proportion of patients who achieved ASDAS LDA within 16 weeks after retreatment are reported using descriptive statistics. Post hoc analyses were conducted to evaluate potential predictors of flare. Due to a small number of patients experiencing flare with continuous IXE treatment, the two IXE treatment groups (IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W) were pooled into a combined IXE group. Additional details of analyses of the flare population with retreatment and for predictors of flare are described in the online supplemental appendix.

Safety analyses were conducted on the randomised withdrawal safety population, defined as all patients who were randomly assigned in the RWRP at week 24 and received at least one dose of study treatment after randomisation. Safety data are summarised from week 24 to week 64. Data after retreatment due to flare were excluded. Baseline was defined as the last non-missing assessment prior to the first injection of study treatment in the RWRP.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of the study, development of outcomes or dissemination of study results.

Results

Patients

Of 773 enrolled patients, 741 completed the 24-week lead-in period and 155 entered the RWRP (figure 1B). At week 24, patients in the RW ITT population had received up to 76 weeks of treatment with IXE and 93.5% (145/155) had received at least 52 weeks of IXE treatment.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics in the RW ITT population were well balanced across treatment arms (table 1). Mean (SD) age and symptom duration were 37.9 (11.1) and 12.7 (8.6) years, respectively. Most (n=97, 63%) patients had r-axSpA and 37% (n=58) had nr-axSpA. Most patients (n=129, 83%) were bDMARD-naïve and 17% (n=26) had prior failure (inadequate response or intolerance) to one or two TNFi. Compared with the overall enrolled patient population at week 0 of COAST-Y, patients in the RW ITT population had lower disease activity (CRP, ASDAS, BASDAI, and Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity) and better function and mobility (BASFI and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index) at week 24; patients in the RW ITT population were also more likely to be younger, bDMARD-naïve and had shorter symptom duration.

Table 1.

Demographics and disease characteristics for patients in COAST-Y

| Lead-in period (N=773) | Randomised withdrawal-retreatment period (N=155) | ||||

| All entered patients N=773 |

Withdrawn to placebo N=53 |

IXE Q4W N=48 |

IXE Q2W N=54 |

Combined IXE N=102 |

|

| Baseline demographics at week 0 | |||||

| Age (years) | 43.2 (12.3) | 38.5 (12.7) | 36.5 (9.7) | 38.4 (10.8) | 37.5 (10.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 551 (71%) | 38 (72%) | 38 (79%) | 40 (74%) | 78 (76%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 562 (73%) | 35 (66%) | 31 (65%) | 31 (57%) | 62 (61%) |

| Asian | 155 (20%) | 13 (25%) | 15 (31%) | 15 (28%) | 30 (29%) |

| Other | 54 (7%) | 5 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 8 (15%) | 10 (10%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 (5.4) | 25.5 (3.9) | 25.9 (4.5) | 25.9 (4.7) | 25.9 (4.6) |

| axSpA symptom duration (years) | 15.5 (10.3) | 12.6 (9.6) | 12.6 (7.5) | 12.9 (8.6) | 12.7 (8.0) |

| axSpA diagnosis duration (years) | 8.3 (8.0) | 6.6 (7.5) | 7.1 (7.0) | 7.6 (8.4) | 7.4 (7.7) |

| HLA-B27 positive, n (%) | 643 (84%) | 45 (85%) | 43 (90%) | 49 (91%) | 92 (90%) |

| csDMARDs use, n (%) | 275 (36%) | 21 (40%) | 18 (38%) | 24 (44%) | 42 (41%) |

| NSAID use, n (%) | 682 (88%) | 50 (94%) | 44 (92%) | 51 (94%) | 95 (93%) |

| Prior TNFi use, n (%)* | |||||

| 0 | 537 (70%) | 44 (83%) | 39 (81%) | 46 (85%) | 85 (83%) |

| 1 | 158 (20%) | 9 (17%) | 3 (6%) | 8 (15%) | 11 (11%) |

| 2 | 78 (10%) | 0 | 6 (13%) | 0 | 6 (6%) |

| Originating study, n (%) | |||||

| COAST-V (r-axSpA, bDMARD-naïve) | 291 (38%) | 24 (45%) | 25 (52%) | 22 (41%) | 47 (46%) |

| COAST-W (r-axSpA, TNFi-experienced) | 236 (31%) | 9 (17%) | 9 (19%) | 8 (15%) | 17 (17%) |

| COAST-X (nr-axSpA, bDMARD-naïve) | 246 (32%) | 20 (38%) | 14 (29%) | 24 (44%) | 38 (37%) |

| Disease characteristics at week 0 | |||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 4.5 (6.1) | 3.5 (8.8)† | 2.9 (5.8) | 2.1 (2.2) | 2.5 (4.3) |

| ≤5 mg/L, n (%) | 548 (71%) | 45 (85%) | 43 (90%) | 48 (89%) | 91 (89%) |

| >5 mg/L, n (%) | 225 (29%) | 8 (15%) | 5 (10%) | 6 (11%) | 11 (11%) |

| ASDAS score | 2.3 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.5) |

| ASDAS LDA (<2.1), n (%) | 344 (45%) | 48 (91%) | 44 (92%) | 52 (96%) | 96 (94%) |

| ASDAS ID (<1.3), n (%) | 123 (16%) | 36 (68%) | 30 (63%) | 31 (57%) | 61 (60%) |

| BASDAI score | 3.9 (2.3) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.1) |

| BASDAI spinal pain‡ | 4.2 (2.5) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.4) |

| BASDAI morning stiffness§ | 3.5 (2.4) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.2) |

| PatGA | 4.1 (2.5) | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.4) |

| BASFI score | 3.8 (2.5) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.1) |

| BASMI score | 3.5 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.3) |

| Disease characteristics at week 24 | |||||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | – | 2.0 (2.4) | 3.1 (4.0) | 2.1 (1.8) | 2.6 (3.1) |

| ≤5 mg/L, n (%) | – | 46 (87%) | 38 (79%) | 49 (91%) | 87 (85%) |

| >5 mg/L, n (%) | – | 7 (13%) | 10 (21%) | 5 (9%) | 15 (15%) |

| ASDAS score | – | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| ASDAS LDA (<2.1), n (%) | – | 50 (94%) | 43 (90%) | 54 (100%) | 97 (95%) |

| ASDAS ID (<1.3), n (%) | – | 37 (70%) | 32 (67%) | 34 (63%) | 66 (65%) |

| BASDAI score | – | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.0) |

| BASDAI spinal pain† | – | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| BASDAI morning stiffness‡ | – | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| PatGA | – | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.3) |

| BASFI score | – | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) |

| BASMI score | – | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.3) |

Data are presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise specified.

*Excludes adalimumab taken as study drug in COAST-V.

†One patient in the withdrawn to placebo group had a high CRP of 61.5 mg/L at week 0, resulting in an increased mean CRP for this treatment group (maximum CRP level was 32.3 for IXE Q4W and 12.3 for IXE Q2W).

‡BASDAI Question 2.

§Mean of BASDAI Questions 5 and 6.

ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen B27; IXE, ixekizumab; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PatGA, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; r-axSpA, radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Maintenance of disease control when continuing versus withdrawing ixekizumab

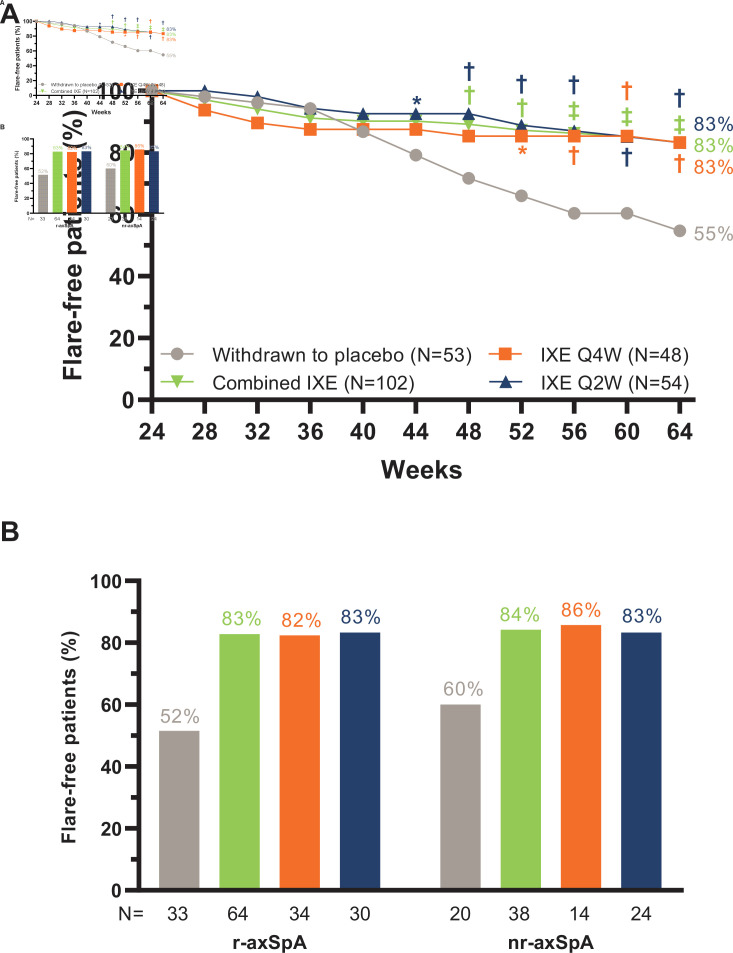

The primary and all major secondary objectives were achieved at week 64. During the RWRP, 83.3% of patients (n=85, p<0.001) in the combined IXE treatment group (IXE Q4W: 83.3%, n=40, p=0.003; IXE Q2W 83.3%, n=45, p=0.001) remained flare-free versus 54.7% (n=29) in patients who withdrew to placebo (figure 2A, table 2). The proportion of flare-free patients was similar between patient subgroups with r-axSpA and nr-axSpA (figure 2B). The proportion of flare-free rates in additional patient subgroups are presented in online supplemental table 1.

Figure 2.

(A) Proportion of flare-free patients through week 64. P value vs withdrawn to placebo: *p<0.05, †p<0.01, ‡p<0.001. (B) Proportion of flare-free patients at week 64 in patient subgroups with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (r-axSpA) and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA).

Table 2.

Summary of efficacy outcomes at week 64 in the randomised withdrawal intent-to-treat population

| Withdrawn to placebo N=53 |

IXE Q4W N=48 |

IXE Q2W N=54 |

Combined IXE N=102 |

|||||||

| Response n (%) |

Response n (%) |

Difference vs placebo (95% CI) |

P value vs placebo | Response n (%) |

Difference vs placebo (95% CI) |

P value vs placebo | Response n (%) |

Difference vs placebo (95% CI) |

P value vs placebo | |

| Flare-free patients* | 29 (54.7%) | 40 (83.3%) | 28.6%(11.6% to 45.7%) | 0.003 | 45 (83.3%) | 28.6% (11.9% to 45.3%) | 0.001 | 85 (83.3%) | 28.6% (13.4% to 43.8%) | <0.001 |

| Patients without clinically important worsening (ASDAS worsening ≥0.9 per ASAS definition)† | 16 (30.2%) | 35 (72.9%) | 42.7% (25.1% to 60.4%) | <0.001 | 40 (74.1%) | 43.9% (26.9% to 60.9%) | <0.001 | 75 (73.5%) | 43.3% (28.3% to 58.4%) | <0.001 |

| ASDAS | ||||||||||

| ASDAS LDA (<2.1) | 24 (45.3%) | 40 (83.3%) | 38.1% (21.0% to 55.1%) | <0.001 | 44 (81.5%) | 36.2% (19.3% to 53.1%) | <0.001 | 84 (82.4%) | 37.1% (21.8% to 52.4%) | <0.001 |

| ASDAS ID (<1.3) | 13 (24.5%) | 29 (60.4%) | 35.9% (17.8% to 53.9%) | <0.001 | 29 (53.7%) | 29.2% (11.5% to 46.8%) | 0.003 | 58 (56.9%) | 32.3% (17.3% to 47.4%) | <0.001 |

*Flare was defined as an ASDAS≥2.1 at two consecutive visits or an ASDAS>3.5 at any visit.

†Assessment of ASDAS worsening of ≥0.9 was conducted as a post hoc analysis and was not the prespecified definition of flare nor a criterion for retreatment after flare. Six patients (IXE Q4W: n=4, IXE Q2W: n=1, and withdrawn to placebo: n=1) were censored due to retreatment after meeting the prespecified definition of flare. As a result, response is slightly underestimated using non-responder imputation.

ASAS, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society criteria; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ID, inactive disease; IXE, ixekizumab; LDA, low disease activity; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks.

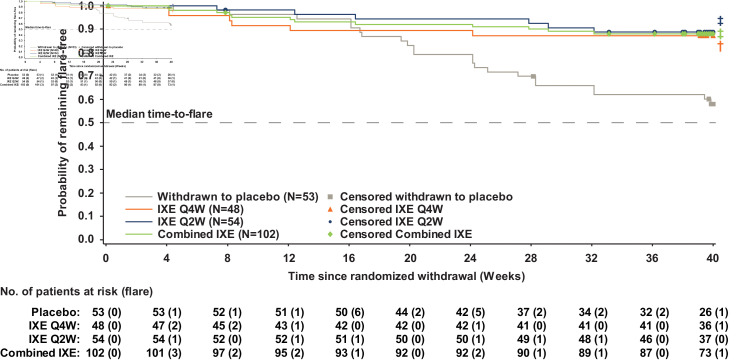

Continuing IXE treatment significantly delayed time-to-flare versus withdrawal to placebo for the combined IXE (p<0.001), IXE Q4W (p=0.004) and IXE Q2W (p<0.001) groups (figure 3). Separation between the continuous IXE and withdrawn to placebo groups first occurred 20 weeks after withdrawal from IXE treatment.

Figure 3.

Time-to-flare. P value vs withdrawn to placebo: †p<0.01, ‡p<0.001. IXE, ixekizumab; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks.

In post hoc analyses, the proportion of patients who did not experience a clinically important worsening (ASDAS worsening ≥0.9) since week 24 was significantly greater in the IXE groups versus patients who withdrew to placebo (table 2).

Predictors of flare

Post hoc analysis for the pooled RW ITT population was conducted to identify patient characteristics associated with flare, which are presented in online supplemental tables 2-4. Multivariate model analysis identified IXE withdrawal, non-normal body mass index (BMI) (non-normal BMI: <18.5 or ≥25 kg/m2), antidrug antibody positive status at any time between week 0 of the originating study and week 24 of COAST-Y, higher CRP level at baseline of the originating study, and larger ASDAS area under the curve as being associated with flare (online supplemental table 3). In addition, when the interaction of treatment by the potential predictors of flare was examined, IXE withdrawal, non-normal BMI and higher CRP at baseline of the originating study were identified as predictors of flare (online supplemental table 4). A significant interaction of IXE withdrawal by BASDAI pain score at week 24 was identified, indicating that higher BASDAI pain score at week 24 was significantly associated with flare in patients who continued IXE treatment; this association was not significant in patients who withdrew to placebo.

Efficacy following retreatment with ixekizumab

The mean (SD) ASDAS at the time of flare was 2.9 (1.1) for IXE Q4W, 2.8 (0.6) for IXE Q2W and 3.5 (0.9) for patients who withdrew to placebo. In addition, a greater proportion of patients who withdrew to placebo (48%) had ASDAS very high disease activity (>3.5) than patients who continued IXE treatment (IXE Q4W: 29%, IXE Q2W: 17%) (online supplemental table 5). Among patients who flared and received at least 16 weeks of retreatment with open-label IXE, ASDAS LDA and ASDAS ID were recaptured within 16 weeks of retreatment for 93% (n=14/15) and 44% (n=8/18) of those who had withdrawn to placebo, respectively; 50% (n=2/4) of those who had continued IXE recaptured ASDAS LDA and 30% (3/10) recaptured ASDAS ID within 16 weeks of retreatment.

Safety

TEAEs were reported in 42.6% (IXE Q4W), 44.4% (IXE Q2W) and 52.8% (withdrawn to placebo) of patients (table 3). Two patients (IXE Q2W) discontinued the study due to AEs. SAEs were reported in two (4.3%) patients in the IXE Q4W group (benign ovarian germ cell teratoma and compression fracture), two (3.7%) patients in the IXE Q2W group (chronic tonsillitis and myelopathy in one patient and Clostridium difficile colitis in another) and one (1.9%) patient who withdrew to placebo (soft tissue inflammation). Only one SAE (C. difficile colitis) resulted in discontinuation. There were no deaths and no reports of reactivation of tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) or malignancy.

Table 3.

Summary of safety in the randomised withdrawal safety population* (weeks 24–64)

| Withdrawn to placebo N=53 |

IXE Q4W N=47 |

IXE Q2W N=54 |

Combined IXE N=101 |

|

| TEAE | 28 (52.8%) | 20 (42.6%) | 24 (44.4%) | 44 (43.6%) |

| Mild | 14 (26.4%) | 13 (27.7%) | 11 (20.4%) | 24 (23.8%) |

| Moderate | 9 (17.0%) | 4 (8.5%) | 13 (24.1%) | 17 (16.8%) |

| Severe | 5 (9.4%) | 3 (6.4%) | 0 | 3 (3.0%) |

| Serious AE | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (3.7%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Discontinuation due to AE | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs of special interest | ||||

| Infections | 18 (34.0%) | 8 (17.0%) | 13 (24.1%) | 21 (20.8%) |

| Serious infections | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Opportunistic infections | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candidiasis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection-site reactions | 0 | 1 (2.1%) | 3 (5.6%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| IBD (adjudicated)† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anterior uveitis | 3 (5.7%) | 2 (4.2%) | 3 (5.6%) | 5 (4.9%) |

| Allergic reactions/hypersensitivities‡ | 3 (5.7%) | 0 | 2 (3.7%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Cytopenia | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (1.0%) |

| Hepatic events | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (4.3%) | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| Adjudicated cerebrocardiovascular events | 1 (1.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MACE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 0 | 1 (2.1%) | 0 | 1 (1.0%) |

Data are presented as n (%).

*Includes all randomly assigned patients who entered the randomised withdrawal-retreatment period and received at least one dose of study treatment after randomisation in the randomised withdrawal-retreatment period. Data after retreatment were excluded.

†Includes adjudicated Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Events of suspected IBD were confirmed by adjudication by an external clinical events committee with expertise in IBD. EPIdemiologique des Maladies de l’Appareil Digestif (EPIMAD) criteria for adjudication of suspected IBD define ‘probable’ and ‘definite’ classifications as confirmed cases.

‡No anaphylaxis was reported.

AE, adverse event; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IXE, ixekizumab; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Discussion

Continued IXE treatment resulted in significantly lower occurrence of flare and significantly delayed time-to-flare versus treatment withdrawal among patients with axSpA who achieved remission with IXE treatment. Most patients remained flare-free for as long as 20 weeks after IXE withdrawal. Flare-free response was similar between IXE regimens and between patients with r-axSpA and nr-axSpA.

Large randomised withdrawal studies have evaluated the effects of withdrawal or tapering of TNFi in patients with axSpA, including the ABILITY-3 study of adalimumab and the C-OPTIMISE study of certolizumab pegol.6–9 COAST-Y is the first study to assess the effects of withdrawal of an IL-17A antagonist in patients who achieved axSpA remission. There are several differences in the study design and patient populations between COAST-Y, ABILITY-3 and C-OPTIMISE. COAST-Y included both bDMARD-naïve and TNFi-experienced patients across the axSpA spectrum with a long (12.7 years) mean symptom duration. ABILITY-3 only enrolled bDMARD-naïve patients with nr-axSpA and a mean symptom duration of 6.7 years, whereas C-OPTIMISE enrolled patients across the axSpA spectrum with a short (3.1–3.8 years) mean symptom duration.6 7 At the time of randomised withdrawal, patients in COAST-Y had up to 76 weeks of treatment versus 28 weeks in ABILITY-3 and 48 weeks in C-OPTIMISE. Additional differences include the length of the randomised withdrawal periods, eligibility criteria for entry into the RWRP and definitions for flares.

The above methodological differences limit the comparison of results across studies; however, there are several notable similarities and differences in results. ABILITY-3 and C-OPTIMISE showed that complete withdrawal of adalimumab or certolizumab pegol, respectively, led to significantly more flares compared with continuous treatment.6 7 Similarly, COAST-Y results suggest continuous treatment with IXE is important to maintain optimal disease control. The proportion of flare-free patients continuing IXE in COAST-Y (83.3%, all treatment groups) was similar to those seen for the certolizumab pegol 200 mg Q2W (83.7%) and 200 mg Q4W (79.0%) dosing regimens from C-OPTIMISE.6 In ABILITY-3, a slightly lower proportion of patients (70.0%) remained flare-free.7

Interestingly, 54.7% of patients who withdrew to placebo in COAST-Y remained flare-free during the RWRP, which was greater than observed in ABILITY-3 (47%) and C-OPTIMISE (20.2%). The first separation between the withdrawn to placebo and IXE groups in time-to-flare was observed at approximately 20 weeks after withdrawal from IXE in COAST-Y, whereas first separation occurred earlier in ABILITY-3 (12 weeks) and C-OPTIMISE (8 weeks).

Identifying predictors of flare is important to help clinicians better understand the risk of flare for patients following treatment interruption. Post hoc analyses identified multiple characteristics associated with flare including ASDAS area under the curve, suggesting that patients with less well-controlled disease over time may have been more likely to flare than those who had stable disease control. In addition, withdrawal of IXE, a higher baseline CRP and non-normal BMI (which in most cases was ≥25 kg/m2) were identified as being associated with flare. Higher BASDAI pain score at week 24 was also associated with flare in patients who continued IXE treatment, but not in patients who withdrew to placebo. It is difficult to compare predictors between COAST-Y, ABILITY-3 and C-OPTIMISE given differences in sample size and methodology used to identify predictors.

Among patients who flared and received at least 16 weeks of retreatment with open-label IXE, 93% in the withdrawal to placebo group and 50% of those who continued IXE treatment recaptured ASDAS LDA within 16 weeks of retreatment. These findings are consistent with findings with TNFi, as most patients who flared were able to recapture disease control with retreatment.6 7 However, the number of patients who flared and received retreatment during the first 40 weeks of the RWRP was limited. Longer-term data from this ongoing study (with up to 80 weeks of randomised withdrawal) will likely provide additional information regarding response to retreatment with IXE, as well as predictors of flare.

There were no new or unexpected safety concerns during the RWRP of COAST-Y. TEAEs were typically mild or moderate in severity and SAEs were reported in five (3.2%) patients equally spread across arms. One SAE in the IXE Q2W arm led to discontinuation. There were no deaths and no TEAEs of opportunistic infections, reactivation of tuberculosis, Candida infections, positively adjudicated IBD, MACE or malignancies reported.

COAST-Y provides the first randomised withdrawal data in axSpA for an IL-17A antagonist. The RWRP of COAST-Y included patients across the axSpA spectrum with and without prior TNFi failure and with symptom duration ranging from 1.9 to 44.7 years (mean of 12.7 years). Eligibility criteria for entry into the RWRP and the definition for flare used in COAST-Y are consistent with the current recommended treatment goals of achieving inactive disease, or at least low disease activity, in patients with axSpA.5 COAST-Y is the first randomised-withdrawal study in axSpA to include an assessment of clinically important worsening in disease activity, as defined by ASAS as an increase in ASDAS of ≥0.9 point.20 However, clinically important worsening in disease activity was not the prespecified flare definition in COAST-Y and thus was not a criterion for retreatment after flare. An additional strength of COAST-Y was the long period of active treatment of up to 76 weeks prior to randomised withdrawal (93.5% of patients had ≥52 weeks of IXE treatment), which reflects long-term sustained treatment in clinical practice before clinicians may consider treatment withdrawal for patients with stable disease control. A limitation of COAST-Y is that the study did not assess the effect of tapering treatment.

Continuing IXE treatment resulted in significantly fewer flares and significantly delayed time-to-flare compared with patients who withdrew treatment. Interestingly, 54.7% of patients who withdrew to placebo remained flare-free for up to 40 weeks of treatment withdrawal, with most patients remaining flare-free for up to 20 weeks of withdrawal from IXE. In addition, patients who withdrew to placebo appeared to have greater disease activity at the time of flare than those who continued IXE treatment. Among those patients who did flare, most recaptured an acceptable level of disease control within 16 weeks of retreatment.

Overall, these findings suggest that continuous IXE treatment is important to maintain long-term disease control for most patients. However, the long durability of treatment response following withdrawal of IXE suggests that temporary treatment interruption, such as during infection or prior to surgical procedures, is unlikely to result in flare for most patients. These results are important for clinicians when making treatment decisions regarding treatment interruption and optimising long-term management of axSpA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Clint Bertram, PhD, a medical writer and employee of Eli Lilly and Company, for writing and editorial support. The authors also thank Emily Seem, MS, a statistical analyst and employee of Eli Lilly and Company, and Ann Leung, MS, a biostatistician and employee of Syneos Health, for statistical review and support. Eli Lilly and Company was involved in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and preparation of the submitted manuscript. All authors had full access to all data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Collaborators: The COAST-Y study group includes: Federico Javier Ariel, Alberto Berman, Judith Carrio, Eleonora Del Valle Lucero, Jose Maldonado Cocco, Benito Jorge Velasco, Heinrich Resch, Johannes Grisar, Valderilio Azevedo, Mauro Keiserman, Flora Marcolino, Ricardo Xavier, Antonio Ximenes, Ana Melazzi, Antonio Scotton, Louis Bessette, Walter Maksymowych, Frederic Morin, Eva Dokoupilova, Zdenek Dvorak, Vlastimil Racek, Radka Moravcova, Martina Malcova, Karel Pavelka, Kari K. Eklund, Pentti Jarvinen, Leena Paimela, Philippe Goupille, Eric Lespessailles, Bernard Combe, Gunther Neeck, Jürgen Braun, Andrea Everding, Regina Cseuz, Edit Drescher, Yolanda Braun Moscovici, Ori Elkayam, Yair Molad, Tatiana Reitblat, Carlo Salvarani, Tetsuya Tomita, Yoshinori Taniguchi, Hiromichi Tamaki, Tokutaro Tsuda, Kurisu Tada, Hiroaki Dobashi, Tadashi Okano, Kentaro Inui, Yukitaka Ueki, Yoshifuji Matsumoto, Yoshinobu Koyama, Tatsuya Atsumi, Hitoshi Goto, Yuya Takakubo, Yeon-Ah Lee, Ji Hyeon Ju, Seong Wook Kang, Tae-Hwan Kim, Chang Keun Lee, Eun Bong Lee, Sang Heon Lee, Min-Chan Park, Kichul Shin, Sang-Hoon Lee, Aaron Alejandro Barrera Rodriguez, Fidencio Cons-Molina, Sergio Duran Barragan, Cassandra Michelle Skinner, Cesar Francisco Pacheco Tena, Cesar Ricardo Ramos Remus, Juan Cruz Rizo Rodriguez, Marleen G. van de Sande, Eduard Griep, Malgorzata Szymanska, Tomasz Blicharski, Jan Brzezicki, Anna Dudek, Pawel Hrycaj, Rafal Plebanski, Artur Racewicz, Rafal Wojciechowski, Marek Krogulec, Daniela Opris-Belinski, Ana Maria Ramazan, Galina Matsievskaya, Evgeniya Schmidt, Tatiana Dubinina, Marina Stanislav, Sergey Yakushin, Olga Ershova, Andrey Rebrov, Carlos Gonzalez Fernandez, Jordi Gratacos Masmitja, Juan Sanchez Burson, Hung-An Chen, Ying-Chou Chen, Song-Chou Hsieh, Joung-Liang Lan, Cheng-Chung Wei, Nicholas Barkham, Karl Gaffney, Sophia Khan, Jonathan Packham, Pippa Watson, Melvin Churchill, Atulya Deodhar, Kathleen Flint, Norman Gaylis, Maria Greenwald, Mary Howell, Akgun Ince, Yoel Drucker, Jeffery L. Kaine, Alan Kivitz, Steven Klein, Clarence Legerton, Daksha Mehta, Eric Mueller, Eric Peters, Roel N. Querubin, John Reveille, Michael Sayers, Craig Scoville, Joseph Shanahan, Richard Roseff, Mark Harris, Roger Diegel, Christine Thai, Gregorio Cortes-Maisonet, Oscar Soto-Raices, Carlos Pantojas.

Contributors: RBML, MH, XL and SLL contributed to data analysis and interpretation. LSG, PR and FVdB contributed to data interpretation. DP contributed to data acquisition and interpretation. DA contributed to study design and data interpretation. HC contributed to conception of the study, study design, data analysis and data interpretation. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Competing interests: RBML reports X-ray/MRI reading fees from Rheumatology Consultancy BV and personal fees from AbbVie, UCB, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis and Celgene. LSG reports personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead, Galapagos and GlaxoSmithKline; grants and personal fees from Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. DP reports honorarium from Eli Lilly and Company; grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, MSD, Novartis and Pfizer; and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, UCB, Biocad, GlaxoSmithKline and Gilead. PR reports personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Pfizer and UCB; and grants and personal fees from Janssen and Novartis. MH, XL, SLL, DA and HC report personal fees and stock ownership from Eli Lilly and Company. FVdB reports personal fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the COAST-Y study group:

Federico Javier Ariel, Alberto Berman, Judith Carrio, Eleonora Del Valle Lucero, Jose Maldonado Cocco, Benito Jorge Velasco, Heinrich Resch, Johannes Grisar, Valderilio Azevedo, Mauro Keiserman, Flora Marcolino, Ricardo Xavier, Antonio Ximenes, Ana Melazzi, Antonio Scotton, Louis Bessette, Walter Maksymowych, Frederic Morin, Eva Dokoupilova, Zdenek Dvorak, Vlastimil Racek, Radka Moravcova, Martina Malcova, Karel Pavelka, Kari K. Eklund, Pentti Jarvinen, Leena Paimela, Philippe Goupille, Eric Lespessailles, Bernard Combe, Gunther Neeck, Jürgen Braun, Andrea Everding, Regina Cseuz, Edit Drescher, Yolanda Braun Moscovici, Ori Elkayam, Yair Molad, Tatiana Reitblat, Carlo Salvarani, Tetsuya Tomita, Yoshinori Taniguchi, Hiromichi Tamaki, Tokutaro Tsuda, Kurisu Tada, Hiroaki Dobashi, Tadashi Okano, Kentaro Inui, Yukitaka Ueki, Yoshifuji Matsumoto, Yoshinobu Koyama, Tatsuya Atsumi, Hitoshi Goto, Yuya Takakubo, Yeon-Ah Lee, Ji Hyeon Ju, Seong Wook Kang, Tae-Hwan Kim, Chang Keun Lee, Eun Bong Lee, Sang Heon Lee, Min-Chan Park, Kichul Shin, Sang-Hoon Lee, Aaron Alejandro Barrera Rodriguez, Fidencio Cons-Molina, Sergio Duran Barragan, Cassandra Michelle Skinner, Cesar Francisco Pacheco Tena, Cesar Ricardo Ramos Remus, Juan Cruz Rizo Rodriguez, Marleen G. van de Sande, Eduard Griep, Malgorzata Szymanska, Tomasz Blicharski, Jan Brzezicki, Anna Dudek, Pawel Hrycaj, Rafal Plebanski, Artur Racewicz, Rafal Wojciechowski, Marek Krogulec, Daniela Opris-Belinski, Ana Maria Ramazan, Galina Matsievskaya, Evgeniya Schmidt, Tatiana Dubinina, Marina Stanislav, Sergey Yakushin, Olga Ershova, Andrey Rebrov, Carlos Gonzalez Fernandez, Jordi Gratacos Masmitja, Juan Sanchez Burson, Hung-An Chen, Ying-Chou Chen, Song-Chou Hsieh, Joung-Liang Lan, Cheng-Chung Wei, Nicholas Barkham, Karl Gaffney, Sophia Khan, Jonathan Packham, Pippa Watson, Melvin Churchill, Atulya Deodhar, Kathleen Flint, Norman Gaylis, Maria Greenwald, Mary Howell, Akgun Ince, Yoel Drucker, Jeffery L. Kaine, Alan Kivitz, Steven Klein, Clarence Legerton, Daksha Mehta, Eric Mueller, Eric Peters, Roel N. Querubin, John Reveille, Michael Sayers, Craig Scoville, Joseph Shanahan, Richard Roseff, Mark Harris, Roger Diegel, Christine Thai, Gregorio Cortes-Maisonet, Oscar Soto-Raices, and Carlos Pantojas

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

COAST-Y was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethical review board at each participating site.

References

- 1. Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis: is there a treatment of choice? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2013;5:45–54. 10.1177/1759720X12468658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (Part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83. 10.1136/ard.2009.108233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. López-Medina C, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, et al. Characteristics and burden of disease in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a comparison by systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open 2019;5:e001108. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smolen JS, Schöls M, Braun J, et al. Treating axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis, especially psoriatic arthritis, to target: 2017 update of recommendations by an international Task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:3–17. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landewé RB, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Maintenance of clinical remission in early axial spondyloarthritis following certolizumab pegol dose reduction. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:920–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Landewé R, Sieper J, Mease P, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuing versus withdrawing adalimumab therapy in maintaining remission in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (ABILITY-3): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2018;392:134–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31362-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haibel H, Heldmann F, Braun J, et al. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab after drug withdrawal and retreatment in patients with active non-radiographically evident axial spondyloarthritis who experience a flare. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2211–3. 10.1002/art.38014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song I-H, Althoff CE, Haibel H, et al. Frequency and duration of drug-free remission after 1 year of treatment with etanercept versus sulfasalazine in early axial spondyloarthritis: 2 year data of the ESTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1212–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:2441–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31946-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ixekizumab in the Treatment of Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis: Sixteen-Week Results From a Phase III Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Patients With Prior Inadequate Response to or Intolerance of Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:599–611. 10.1002/art.40753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dougados M, Wei JC-C, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:176–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Gensler LS, et al. Ixekizumab for patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-X): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020;395:53–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32971-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The assessment of spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) Handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68 Suppl 2:ii1–44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1876–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandt J, Listing J, Sieper J, et al. Development and preselection of criteria for short term improvement after anti-TNF alpha treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1438–44. 10.1136/ard.2003.016717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53. 10.1136/ard.2010.138594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Machado PM, Landewé R, Heijde Dvander, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity states. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1539–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Machado PMMC, Landewé RBM, van der Heijde DM. Endorsement of definitions of disease activity states and improvement scores for the ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score: results from OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1502–6. 10.3899/jrheum.110279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molto A, Gossec L, Meghnathi B, et al. An Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS)-endorsed definition of clinically important worsening in axial spondyloarthritis based on ASDAS. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:124–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2020-219717supp001.pdf (358.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.