Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy/safety of tofacitinib in adult patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

Methods

This phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study enrolled patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with active AS, meeting the modified New York criteria, with centrally read radiographs, and an inadequate response or intolerance to ≥2 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients were randomised 1:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day or placebo for 16 weeks. After week 16, all patients received open-label tofacitinib until week 48. The primary and key secondary endpoints were Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society ≥20% improvement (ASAS20) and ≥40% improvement (ASAS40) responses, respectively, at week 16. Safety was assessed throughout.

Results

269 patients were randomised and treated: tofacitinib, n=133; placebo, n=136. At week 16, the ASAS20 response rate was significantly (p<0.0001) greater with tofacitinib (56.4%, 75 of 133) versus placebo (29.4%, 40 of 136), and the ASAS40 response rate was significantly (p<0.0001) greater with tofacitinib (40.6%, 54 of 133) versus placebo (12.5%, 17 of 136). Up to week 16, with tofacitinib and placebo, respectively, 73 of 133 (54.9%) and 70 of 136 (51.5%) patients had adverse events; 2 of 133 (1.5%) and 1 of 136 (0.7%) had serious adverse events. Up to week 48, with tofacitinib, 3 of 133 (2.3%) patients had adjudicated hepatic events, 3 of 133 (2.3%) had non-serious herpes zoster, and 1 of 133 (0.8%) had a serious infection; with placebo→tofacitinib, 2 (1.5%) patients had non-serious herpes zoster. There were no deaths, malignancies, major adverse cardiovascular events, thromboembolic events or opportunistic infections.

Conclusions

In adults with active AS, tofacitinib demonstrated significantly greater efficacy versus placebo. No new potential safety risks were identified.

Trial registration number

Keywords: spondylitis, ankylosing, antirheumatic agents, therapeutics

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis and polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

In a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study in adult patients with ankylosing spondylitis (NCT01786668), tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg two times per day demonstrated greater clinical efficacy versus placebo, with a safety profile consistent with that established in other indications.

What does this study add?

This was the first phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in adult patients with active ankylosing spondylitis.

Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day demonstrated significantly greater efficacy versus placebo at week 16, with rapid and sustained clinical response, and no new potential safety risks identified up to week 48 (end of study treatment).

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

If approved by regulatory agencies, tofacitinib could be one of a new class of drugs for use in ankylosing spondylitis, adding to the currently limited treatment options for this disease.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), also called radiographic axial spondyloarthritis,1 is a chronic inflammatory disease of the axial skeleton that can result in serious impairment of spinal mobility and reduced quality of life.2–4 The incidence of AS is 0.4–15.0 per 100 000 patient-years, varying by region.5

The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)/European League Against Rheumatism and American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network treatment guidelines recommend several pharmacological treatments for AS management as well as physical therapy.6 7 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended as first-line treatment, followed by biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi).6 7

No evidence exists to support the efficacy of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) for treating purely axial disease.6 Therefore, treatment options are limited for patients with an inadequate response or intolerance (IR) to NSAIDs. Furthermore, given that bDMARDs are administered parenterally, there is an unmet need for oral therapies with alternative mechanisms of action to treat AS.

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor that is being investigated for the treatment of adult patients with AS. JAK inhibitors directly bind to and modulate the intracellular catalytic activity of JAKs, which are essential enzymes in signalling pathways that mediate cytokine signalling for many innate and adaptive immune responses underlying the complex pathogenesis of AS.8 9 Activation of these signalling pathways ultimately leads to the proliferation of inflammatory cells in articular and extramusculoskeletal locations, and of cell types associated with the hallmarks of AS such as joint destruction.9 Thus, inhibition of JAKs could suppress articular and extramusculoskeletal symptoms of AS.9

A favourable benefit–risk balance of tofacitinib treatment has been established in adults with rheumatoid arthritis,10 11 psoriatic arthritis12 13 and ulcerative colitis,14 15 and in children with polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.16

In a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study in patients with AS (NCT01786668), tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg two times per day demonstrated greater efficacy versus placebo at week 12, with a safety profile consistent with that established in other indications.17 These results suggested that JAK inhibition could present a new mechanism of action for treating AS.

Here, we report the results of a phase III study of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in adult patients with active AS.

Methods

Study design and participants

This phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted at 75 centres in 14 countries, from 7 June 2018 through 20 August 2020. The study protocol is provided in the online supplemental material.

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had a diagnosis of AS and fulfilled the modified New York criteria for AS, documented with central reading of the radiograph of the sacroiliac joints. Patients were required to have active disease at screening and baseline, defined as Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score ≥4 and back pain score (BASDAI question 2) ≥4, and an IR to ≥2 NSAIDs. Approximately 80% of the population were to be bDMARD-naïve, and approximately 20% were to have an IR to ≤2 TNFi or to have prior bDMARD (TNFi or non-TNFi) use without IR. Exclusion criteria included current/prior treatment with targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (including JAK inhibitors) and current bDMARD treatment. Prior bDMARD treatment was permitted if discontinued for ≥4 weeks or ≥5 half-lives (whichever was longer) before randomisation.

Patients could continue the following (stable) background therapies: NSAIDs, methotrexate (≤25 mg/week), sulfasalazine (≤3 g/day) and oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent).

In the double-blind phase (weeks 0–16), patients were randomised 1:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day or placebo. In the open-label phase (weeks 16–48), all patients received open-label tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day. Patients who discontinued the study drug were expected to continue with all regularly scheduled visits for safety and efficacy assessments.

All patients were required to have a follow-up visit within 28 (±7) days of week 48, unless they had discontinued study drug before week 40.

All patients provided written, informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

Randomisation was stratified by bDMARD treatment history: (1) bDMARD-naïve and (2) TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR. Allocation of patients to treatment arms was performed using an Interactive Response Technology system. The double-blind phase was masked to the patients, investigators and sponsor study team. The patients, investigators and sponsor study team remained blinded to the double-blind phase treatment assignments for the duration of the study, until week 48 database release.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was ASAS20 response at week 16 (≥20% and ≥1 unit improvement from baseline in ≥3 of 4 components and no worsening of ≥20% and ≥1 unit in the remaining component). The key secondary endpoint was ASAS40 response at week 16 (≥40% and ≥2 units improvement from baseline in ≥3 components and no worsening in the remaining component). The four ASAS components are Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA), patient assessment of back pain (total back pain), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) and morning stiffness (inflammation), defined as the mean of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI. ASAS20/ASAS40 responses were also analysed over time through week 48.

Secondary efficacy endpoints analysed at week 16 included ASAS20/ASAS40 response rates stratified by bDMARD treatment history, and change from baseline (∆) in Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) and Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2 Physical Component Summary (SF-36v2 PCS) scores.

Secondary efficacy endpoints analysed at week 16 and over time up to week 48 included ∆Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) using high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), ∆hsCRP, ∆Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) linear method, ∆Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) total score, ∆ASAS components, ASAS partial remission (scores ≤2 for each of the four ASAS components), ASAS 5/6 response (≥20% improvement in ≥5 of 6 components: the four ASAS components, plus hsCRP and spinal mobility (lateral spinal flexion from the BASMI)), ASDAS clinically important improvement (decrease from baseline of ≥1.1 in patients with baseline scores ≥1.736), ASDAS major improvement (decrease from baseline of ≥2.0 in patients with baseline scores ≥2.636), ASDAS low disease activity (LDA) (scores <2.1 (includes inactive disease) in patients with baseline scores ≥2.1; post-hoc), ASDAS inactive disease (scores <1.3 in patients with baseline scores ≥1.3), ∆BASDAI, BASDAI50 response (≥50% improvement from baseline score), ∆Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) in patients with baseline scores >0, and ∆swollen joint count in 44 joints (SJC(44)) in patients with baseline counts >0.

Safety was monitored throughout the study, including adverse events (AEs), adverse events of special interest (AESIs), clinical laboratory abnormalities and laboratory values over time.

Statistical analyses

The planned sample size was 120 per treatment arm, determined to yield around 89% power to detect a difference of ≥20% in ASAS20 response rate at week 16 between tofacitinib and placebo at a two-sided significance level of 5%. This calculation assumed a 40% ASAS20 response rate for placebo.

The full analysis set and the safety analysis set included all patients who were randomised and received ≥1 dose of study drug. Efficacy analyses included only on-drug data collected while patients were on study treatment.

The reported data are based on two databases: for efficacy data up to week 16, data cut-off 19 December 2019, data snapshot 29 January 2020; all other data are from the final week 48 analysis.

Statistical tests were conducted at the two-sided 5% (or equivalently one-sided 2.5%) significance level for tofacitinib versus placebo. Four families of efficacy endpoints were tested in hierarchical sequences with a step-down approach to control for type I error. The first family, the global type I error-controlled endpoints at week 16, was tested in the following sequence: ASAS20 response, ASAS40 response, ∆ASDAS, ∆hsCRP, ∆ASQoL, ∆SF-36v2 PCS score, ∆BASMI and ∆FACIT-F total score. On meeting statistical significance for ASAS20 response at week 16, the second family, ∆ASAS components at week 16, was tested in the following sequence: ∆PtGA, ∆total back pain, ∆BASFI and ∆morning stiffness (inflammation). The third family, ASAS20 response over time, and the fourth family, ASAS40 response over time, were each tested in the following sequence: weeks 16, 12, 8, 4 and 2. In each family, statistical significance could be declared only if the prior endpoint (or time point) in the sequence met the requirements for significance. Other secondary endpoints were not type I error-controlled.

Binary efficacy endpoints were assessed using normal approximation adjusting for the stratification factor (bDMARD treatment history: bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR) derived from the clinical database, via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach. Missing response was considered as non-response.

For ∆ in continuous efficacy endpoints with repeated measures at multiple visits, a mixed model for repeated measures was used, which included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment group by visit interaction, stratification factor derived from the clinical database, stratification factor by visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline value by visit interaction. The model used a common unstructured variance–covariance matrix, without imputation for missing values. Absolute values were also summarised descriptively, without imputation for missing values.

For ∆ in continuous efficacy endpoints with only a single postbaseline visit measure, an analysis of covariance model was used, which included fixed effects of treatment group, stratification factor derived from the clinical database and baseline value. Missing values were not imputed.

The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of the hsCRP assay was 0.2 mg/L. For hsCRP values <LLOQ, they were set to 0.199 mg/L in all efficacy and safety analyses except for the ASDAS-related endpoints, where values <2 mg/L were set post-hoc to 2 mg/L.18

Safety data were summarised descriptively using observed data.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Patients

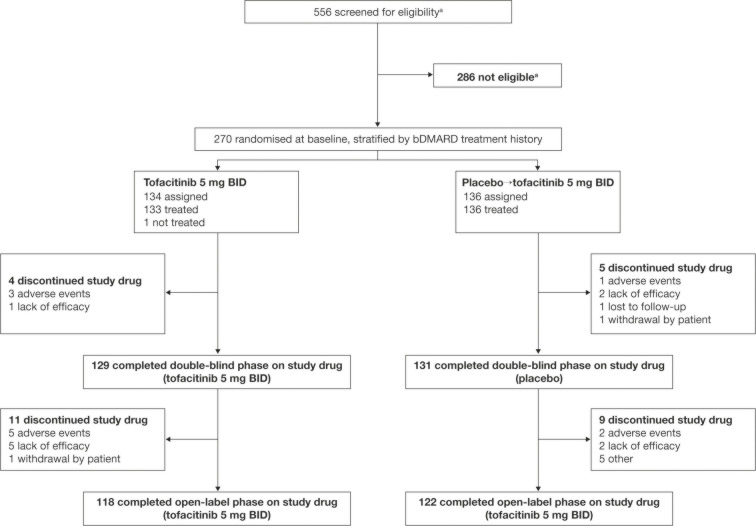

Of 556 screened patients, 270 were randomised (figure 1). Of 134 patients randomised to the tofacitinib arm, 133 patients were treated (1 patient was not treated and was excluded from the analyses). All 136 patients randomised to the placebo→tofacitinib arm were treated. The demographics and baseline disease characteristics were generally similar between the treatment arms (table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. Data are from the week 48 final analysis. Patients receiving placebo in the double-blind phase advanced at week 16 to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day for the open-label phase. aOne additional patient was screened and was considered to be not eligible; this patient did not provide any demographic data and is therefore not included in the formal patient disposition. bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, two times per day.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=133) | Placebo (N=136) |

|

| Male, n (%) | 116 (87.2) | 108 (79.4) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.2 (11.9) | 40.0 (11.1) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 107 (80.5) | 106 (77.9) |

| Asian | 25 (18.8) | 30 (22.1) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| North America* | 16 (12.0) | 11 (8.1) |

| European Union† | 51 (38.3) | 55 (40.4) |

| Asia‡ | 23 (17.3) | 30 (22.1) |

| Rest of the world§ | 43 (32.3) | 40 (29.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.7)¶ | 26.3 (5.8) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoked | 75 (56.4) | 72 (52.9) |

| Former smoker | 24 (18.0) | 19 (14.0) |

| Current smoker | 34 (25.6) | 45 (33.1) |

| AS disease duration since symptoms (years), mean (SD) | 14.2 (9.8) | 12.9 (9.5) |

| AS disease duration since diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 8.9 (9.1) | 6.8 (6.9) |

| History of uveitis, n (%) | 22 (16.5) | 20 (14.7) |

| Current diagnosis of uveitis with history of uveitis, n (%) |

6 (4.5) | 5 (3.7) |

| History of psoriasis, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 3 (2.2) |

| Current diagnosis of psoriasis with history of psoriasis, n (%) |

2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) |

| History of IBD, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) |

| Current diagnosis of IBD with history of IBD, n (%) |

1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) |

| History of peripheral arthritis, n (%) | 21 (15.8) | 25 (18.4) |

| Current diagnosis of peripheral arthritis with history of peripheral arthritis, n (%) | 18 (13.5) | 22 (16.2) |

| HLA-B27-positive, n (%) | 117 (88.0) | 118 (86.8) |

| hsCRP | ||

| Mean mg/dL (SD) | 1.64 (1.73) | 1.80 (1.97) |

| ≤5 mg/L, n (%) | 41 (30.8) | 33 (24.3) |

| >5 mg/L, n (%) | 92 (69.2) | 103 (75.7) |

| ASDAS, mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.8) |

| BASDAI (NRS 0–10), mean (SD) |

6.4 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.4) |

| Morning stiffness (inflammation; NRS 0–10),** mean (SD) |

6.6 (1.9) | 6.8 (1.9) |

| BASMI, mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.8) |

| BASFI (NRS 0–10), mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.3) | 5.9 (2.1) |

| FACIT-F total score, mean (SD) | 27.2 (10.7) | 27.4 (9.3) |

| ASQoL, mean (SD) | 11.6 (4.7) | 11.3 (4.2) |

| SF-36v2 PCS score, mean (SD) | 33.5 (7.3) | 33.1 (7.0)†† |

| PtGA (NRS 0–10), mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.8) | 7.0 (1.7) |

| Total back pain (NRS 0–10), mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.6) |

| Presence of enthesitis based on MASES >0, n (%) |

71 (53.4) | 81 (59.6) |

| MASES,‡‡ mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.4) |

| Presence of swollen joints based on SJC(44) >0, n (%) | 33 (24.8) | 38 (27.9) |

| SJC(44),§§ mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.0) | 4.1 (5.2) |

| Prior NSAID use, n (%) | 133 (100.0) | 135 (99.3)¶¶ |

| Prior bDMARD use, n (%) | ||

| bDMARD-naïve | 102 (76.7) | 105 (77.2) |

| TNFi-IR*** or prior bDMARD use without IR | 31 (23.3) | 31 (22.8) |

| 1 TNFi-IR | 23 (17.3) | 20 (14.7) |

| 2 TNFi-IR | 6 (4.5) | 10 (7.4) |

| Prior bDMARD use without IR | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Concomitant medication use on day 1, n (%) | ||

| NSAIDs | 106 (79.7) | 108 (79.4) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 13 (9.8) | 7 (5.1) |

| csDMARDs | 29 (21.8) | 44 (32.4) |

| Methotrexate | 5 (3.8) | 13 (9.6) |

| Sulfasalazine | 24 (18.0) | 31 (22.8) |

Data are from the week 48 final analysis.

*Canada and USA.

†Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Hungary and Poland.

‡China and South Korea.

§Australia, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine.

¶N1=132.

**Morning stiffness (inflammation) assessed as mean of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI.

††N1=135.

‡‡In patients with baseline MASES >0.

§§In patients with SJC(44) >0.

¶¶One patient did not take prior NSAIDs due to medical history.

***Patients designated as TNFi-IR must have had an IR to at least one, but not more than two, approved TNFi.

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score using hsCRP; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen-B27; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IR, inadequate response or intolerance; MASES, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score; N, number of patients in safety analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at visit; n, number of patients with the characteristic; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SF-36v2 PCS, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2 Physical Component Summary; PtGA, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; SJC(44), swollen joint count in 44 joints; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Efficacy at week 16 (end of double-blind phase)

The ASAS20 response rate was significantly (p<0.0001) greater with tofacitinib (56.4%, 75 of 133) versus placebo (29.4%, 40 of 136) at week 16 (primary endpoint; table 2). Similarly, the ASAS40 response rate was significantly (p<0.0001) greater with tofacitinib (40.6%, 54 of 133) versus placebo (12.5%, 17 of 136) at week 16 (key secondary endpoint; table 2). When stratified by bDMARD treatment history, ASAS20/ASAS40 response rates at week 16 remained numerically greater with tofacitinib versus placebo, and in both treatment groups response rates were numerically greater in patients who were bDMARD-naïve versus those with TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR (online supplemental figure S1).

Table 2.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo at week 16: type I error-controlled primary and secondary endpoints†

| Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=133) | Placebo (N=136) | p value | |

| Global type I error-controlled endpoints at week 16, tested in the sequence below | |||

| ASAS20 response,‡ n (%) | 75 (56.4) | 40 (29.4) | <0.0001***§ |

| ASAS40 response,‡ n (%) | 54 (40.6) | 17 (12.5) | <0.0001***§ |

| ∆ASDAS,¶ LSM (SE) (N1) | −1.36 (0.07) (129) | −0.39 (0.07) (131) | <0.0001***§ |

| ∆hsCRP (mg/dL),¶ LSM (SE) (N1) | −1.05 (0.10) (129) | −0.09 (0.10) (131) | <0.0001***§ |

| ∆ASQoL,** LSM (SE) (N1) | −4.03 (0.40) (129) | −2.01 (0.41) (130) | 0.0001***§ |

| ∆SF-36v2 PCS score,** LSM (SE) (N1) | 6.69 (0.59) (129) | 3.14 (0.59) (130) | <0.0001***§ |

| ∆BASMI,¶ LSM (SE) (N1) | −0.63 (0.06) (129) | −0.11 (0.06) (131) | <0.0001***§ |

| ∆FACIT-F total score,¶ LSM (SE) (N1) | 6.54 (0.80) (129) | 3.12 (0.79) (131) | 0.0008***§ |

| Type I error-controlled ∆ASAS components at week 16¶§§ tested in the sequence below | |||

| ∆PtGA (NRS 0–10), LSM (SE) (N1) | −2.47 (0.20) (129) | −0.91 (0.20) (131) | <0.0001***†† |

| ∆Total back pain (NRS 0–10), LSM (SE) (N1) | −2.57 (0.19) (129) | −0.96 (0.19) (131) | <0.0001***†† |

| ∆BASFI (NRS 0–10), LSM (SE) (N1) | −2.05 (0.17) (129) | −0.82 (0.17) (131) | <0.0001***†† |

| ∆Morning stiffness (inflammation, NRS 0–10),‡‡ LSM (SE) (N1) | −2.69 (0.19) (129) | −0.97 (0.19) (131) | <0.0001***†† |

Data are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020.

***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo.

†In each family of type I error-controlled endpoints, statistical significance could be declared only if the prior endpoint in the sequence met the requirements for significance (p≤0.05).

‡Normal approximation adjusting for the stratification factor (bDMARD treatment history: bDMARD-naïve versus TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR) derived from the clinical database via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach was used. Missing response was considered as non-response.

§p≤0.05 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo, according to the prespecified step-down testing procedure for global type I error control.

¶Mixed model for repeated measures included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment group by visit interaction, stratification factor derived from the clinical database, stratification factor by visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline value by visit interaction. The model used a common unstructured variance–covariance matrix, without imputation for missing values.

**Analysis of covariance model included fixed effects of treatment group, stratification factor derived from the clinical database and baseline value. Missing values were not imputed.

††p≤0.05 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo, according to the prespecified step-down testing procedure for type I error control of ASAS components.

‡‡Morning stiffness (inflammation) assessed as mean of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI.

§§Endpoints were tested in sequence after ASAS20 response at week 16 met the requirements for significance (p≤0.05).

∆, change from baseline; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score using hsCRP; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IR, inadequate response or intolerance; LSM, least squares mean; n, number of patients with response; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at week 16; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PtGA, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2 Physical Component Summary; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp001.pdf (2.3MB, pdf)

Significant improvements with tofacitinib versus placebo were seen at week 16 in the other global type I error-controlled endpoints: ∆ASDAS, ∆hsCRP, ∆ASQoL, ∆SF-36v2 PCS score, ∆BASMI and ∆FACIT-F total score (table 2). Furthermore, significant improvements were seen with tofacitinib versus placebo at week 16 in the type I error-controlled ∆ASAS components (table 2).

Efficacy was greater with tofacitinib versus placebo at week 16 in rates of ASAS partial remission, ASAS 5/6 response, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS LDA, ASDAS inactive disease and BASDAI50 response, and in ∆BASDAI (table 3). There was no difference at week 16 between tofacitinib versus placebo in ∆MASES or ∆SJC(44) (table 3).

Table 3.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo at week 16: secondary endpoints without type I error control

| Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=133) | Placebo (N=136) | |

| ASAS partial remission rate,† n (%) | 20 (15.0)*** | 4 (2.9) |

| ASAS 5/6 response rate,† n (%) | 58 (43.6)*** | 10 (7.4) |

| ASDAS clinically important improvement response rate,†‡ n (%) (N1) | 81 (61.4) (132)*** | 26 (19.1) (136) |

| ASDAS major improvement response rate,†§ n (%) (N1) | 37 (30.1) (123)*** | 6 (4.7) (129) |

| ASDAS LDA rate,†¶ n (%) (N1) | 51 (38.9) (131)*** | 11 (8.1) (136) |

| ASDAS inactive disease rate,†** n (%) (N1) | 9 (6.8) (133)** | 0 (0.0) (136) |

| BASDAI50 response rate,† n (%) | 57 (42.9)*** | 24 (17.7) |

| ∆BASDAI,†† LSM (SE) (N2) | −2.55 (0.18) (129)*** | −1.11 (0.17) (131) |

| ∆MASES,††‡‡ LSM (SE) (N2) | −1.94 (0.29) (70) | −1.41 (0.27) (76) |

| ∆SJC(44),††§§ LSM (SE) (N2) | −3.35 (0.48) (33) | −2.79 (0.47) (36) |

Data are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020.

**p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo.

†Normal approximation adjusting for the stratification factor (bDMARD treatment history: bDMARD-naïve versus TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR) derived from the clinical database via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach was used. Missing response was considered as non-response.

‡Analysed in patients with baseline ASDAS ≥1.736.

§Analysed in patients with baseline ASDAS ≥2.636.

¶Analysed in patients with baseline ASDAS ≥2.1.

**Analysed in patients with baseline ASDAS ≥1.3.

††Mixed model for repeated measures included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment group by visit interaction, stratification factor derived from the clinical database, stratification factor by visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline value by visit interaction. The model used a common unstructured variance-covariance matrix, without imputation for missing values.

‡‡Analysed in patients with baseline MASES >0.

§§Analysed in patients with baseline SJC(44) >0.

Δ, change from baseline; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score using hsCRP; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IR, inadequate response or intolerance; LDA, low disease activity; LSM, least squares mean; MASES, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients who met the baseline ASDAS inclusion criterion for the analysis; N2, number of patients with observation at week 16; n, number of patients with response; SJC(44), swollen joint count based on 44 joints; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Efficacy over time up to week 16 (end of double-blind phase) and up to week 48 (end of open-label phase)

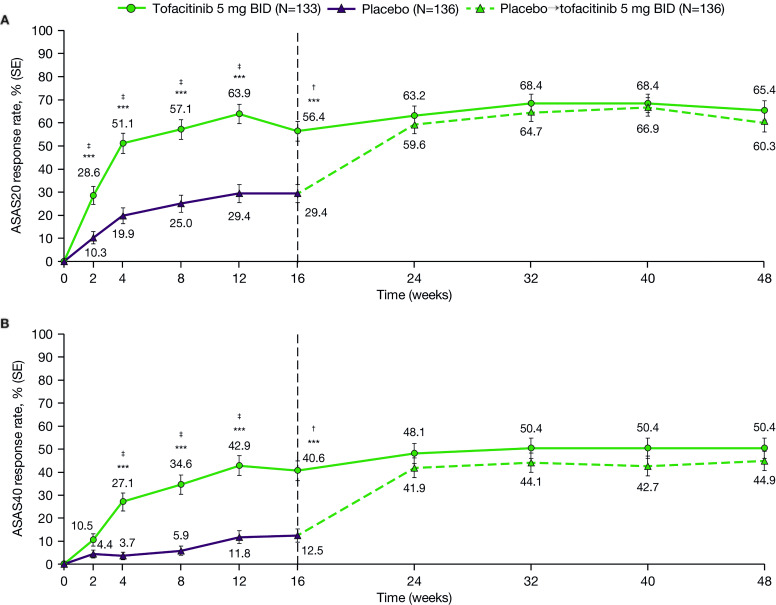

Significant differences between tofacitinib and placebo were seen from week 2 (first post-baseline visit) in ASAS20 response and from week 4 in ASAS40 response up to week 16 (figure 2; type I error-controlled). In the open-label phase, ASAS20/ASAS40 response rates remained stable over time up to week 48 in the tofacitinib group; in the placebo→tofacitinib group, response rates increased between weeks 16 and 24, then remained stable up to week 48.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg two times per daya over time up to week 48: (A) ASAS20 responseb and (B) ASAS40 response.b Data up to week 16 are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020. Data for weeks 24–48 are from the week 48 final analysis. ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo. †p≤0.05 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo, according to the prespecified step-down testing procedure for global type I error control. ‡p≤0.05 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo, according to the prespecified step-down testing procedure for type I error control of ASAS response over time. aPatients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day at week 16 (dashed line). bUp to week 16, response rate was tested in hierarchical sequence to control for type I error: weeks 16, 12, 8, 4 and 2. Statistical significance could be declared only if the prior time points in the sequence met the requirements for significance (p≤0.05). After week 16, there was no type I error control. Normal approximation adjusting for the stratification factor (bDMARD treatment history: bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR) derived from the clinical database via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach was used. Missing response was considered as non-response. ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ≥40% improvement; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, two times per day; IR, inadequate response or intolerance; N, number of patients in full analysis set; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

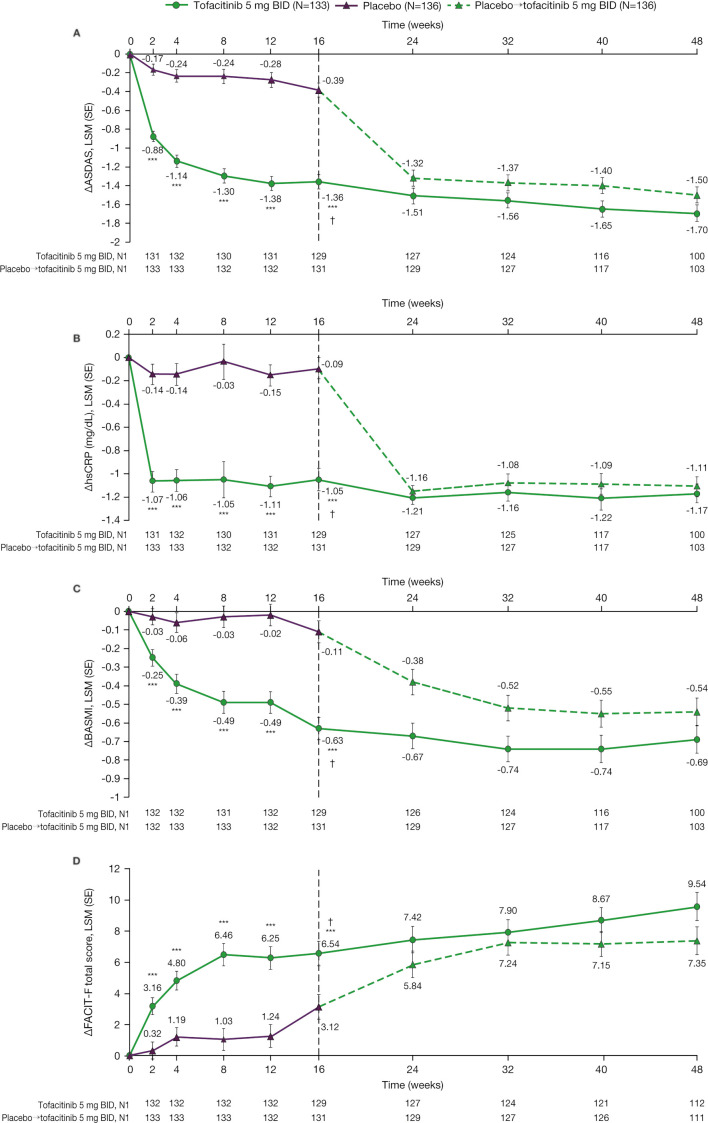

Throughout the double-blind phase, improvements in ∆ASDAS, ∆hsCRP, ∆BASMI and ∆FACIT-F total score were greater with tofacitinib versus placebo (figure 3). During the open-label phase, these endpoints remained stable in the tofacitinib group and improved in the placebo→tofacitinib group between weeks 16 and 24, then remained stable up to week 48. Similar trends were seen in ∆ASAS components (online supplemental figure S2); ASAS partial remission and ASAS 5/6 response (online supplemental figure S3); ASDAS clinically important improvement, major improvement, LDA and inactive disease (online supplemental figure S4); and ∆BASDAI and BASDAI50 response (online supplemental figure S5). No difference in ∆MASES was observed between tofacitinib and placebo at week 16, but improvement was greater with tofacitinib versus placebo at weeks 4, 8 and 12 (online supplemental figure S6A). In the double-blind phase, improvements in ∆SJC(44) were similar with tofacitinib and placebo and were maintained in the open-label phase in both groups (online supplemental figure S6B). Mean ASDAS, hsCRP, BASMI, FACIT-F total score, PtGA, total back pain, BASFI, morning stiffness (inflammation), BASDAI, MASES and SJC(44) over time supported these findings (online supplemental figure S7).

Figure 3.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg two times per daya over time up to week 48: (A) ∆ASDAS,b (B) ∆hsCRP (mg/dL),b (C) ∆BASMIb and (D) ∆FACIT-F total score.b Data up to week 16 are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020. Data for weeks 24–48 are from the week 48 final analysis. ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo. †p≤0.05 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo, according to the prespecified step-down testing procedure for global type I error control. aPatients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day at week 16 (dashed line). bMixed model for repeated measures included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment group by visit interaction, stratification factor (bDMARD treatment history: bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR) derived from the clinical database, stratification factor by visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline value by visit interaction. The model used a common unstructured variance–covariance matrix, without imputation for missing values. Two separate models were used. In the analyses of results through the first 16 weeks, the data cut-off of 19 December 2019 was used; the results through week 16 are from this model. In the analyses of the results through week 48 (including all post-baseline data through week 48), the week 48 final data were used; the results from week 24 through week 48 are from this model. ∆, change from baseline; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score using hsCRP; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, two times per day; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IR, inadequate response or intolerance; LSM, least squares mean; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at visit; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Safety

AEs and laboratory abnormalities are summarised in table 4. Rates of AEs, serious AEs, severe AEs, discontinuations of study drug due to AEs, and dose reductions or temporary discontinuations of study drug due to AEs were numerically higher with tofacitinib versus placebo and placebo→tofacitinib up to week 16 (double-blind phase) and up to week 48 (double-blind and open-label phases), respectively.

Table 4.

Summary of safety up to week 16 and up to week 48

| Patients with events, n (%) | Up to week 16 (double-blind phase) |

Up to week 48 (double-blind and open-label phases) |

||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=133) |

Placebo (N=136) |

Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=133) |

Placebo→ tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=136) |

|

| AEs | 73 (54.9) | 70 (51.5) | 103 (77.4) | 93 (68.4) |

| SAEs* | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (5.3) | 2 (1.5) |

| Severe AEs† | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 6 (4.5) | 0 |

| Discontinued study drug due to AEs | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (6.0) | 3 (2.2) |

| Reduced dose or temporarily discontinued study drug due to AEs | 9 (6.8) | 5 (3.7) | 18 (13.5) | 13 (9.6) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most common AEs by preferred term (>5% of any treatment group) | ||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 14 (10.5) | 10 (7.4) | 21 (15.8) | 18 (13.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 9 (6.8) | 10 (7.4) | 11 (8.3) | 17 (12.5) |

| Diarrhoea | 6 (4.5) | 5 (3.7) | 10 (7.5) | 8 (5.9) |

| Arthralgia | 1 (0.8) | 8 (5.9) | 2 (1.5) | 9 (6.6) |

| ALT increased | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (6.0) | 2 (1.5) |

| Protein urine present | 5 (3.8) | 2 (1.5) | 8 (6.0) | 4 (2.9) |

| Headache | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 5 (3.8) | 7 (5.1) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.5) | 7 (5.1) |

| AESIs | ||||

| Malignancies (including NMSC)‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MACE‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thromboembolic events (DVT, PE or ATE)‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GI perforation‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic events‡ | 1 (0.8)§ | 0 | 3 (2.3)¶ | 0 |

| DILI‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HZ (serious and non-serious) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.3)** | 2 (1.5)** |

| Opportunistic infections‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious infections | 1 (0.8)†† | 0 | 1 (0.8)†† | 0 |

| ILD‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Laboratory values meeting protocol criteria for monitoring‡‡ | 0 | 6 (4.4) | 7 (5.3) | 10 (7.4) |

| Haemoglobin drop >20 g/L below baseline | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.3) | 5 (3.7) |

| Platelet count <100×109/L | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Serum creatinine increase >50% or increase 0.5 mg/dL over the average of screening and baseline values | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) |

| Creatine kinase >5×ULN | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Laboratory values meeting protocol criteria for discontinuation of study drug§§ | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 0 |

| Two sequential AST or ALT elevations >5×ULN | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 0 |

Data are from the week 48 final analysis.

*SAEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence at any dose that was life-threatening; resulted in hospitalisation, prolongation of existing hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect or death; or was considered to be an important medical event.

†Investigators used the adjectives mild, moderate or severe to describe the maximum intensity of the AE. Severe AEs were defined as those that interfered significantly with the patient’s usual function.

‡Adjudicated events.

§Two sequential AST or ALT ≥3×ULN; unrelated DILI; patient did not meet criteria for potential Hy’s law or definite Hy’s law.

¶One patient had two sequential AST or ALT ≥3×ULN, which was unrelated DILI; one patient had AST or ALT ≥5×ULN, which was unlikely DILI; one patient had cholecystitis and recurrence of gallstones, which was unrelated DILI. None of these patients met the criteria for potential Hy’s law nor definite Hy’s law.

**All cases were non-serious.

††Meningitis; did not meet opportunistic infection adjudication criteria.

‡‡Notably, no patients met the following protocol criteria for monitoring: absolute neutrophil count <1.2×109/L; absolute lymphocyte count <0.5×109/L.

§§Notably, no patients met the following protocol criteria for discontinuation of study drug: two sequential absolute neutrophil counts <1.0×109/L; two sequential absolute lymphocyte counts <0.5x109/L.

AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse event of special interest; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ATE, arterial thromboembolism; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GI, gastrointestinal; HZ, herpes zoster; ILD, interstitial lung disease; N, number of patients in safety analysis set; n, number of patients with event; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PE, pulmonary embolism; SAE, serious adverse event; ULN, upper limit of normal.

With tofacitinib up to week 48, there were no deaths and no cases of malignancies (including non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), thromboembolic events, gastrointestinal perforation, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), opportunistic infections or interstitial lung disease (ILD). Adjudicated hepatic events were reported in one (0.8%) patient up to week 16 and three (2.3%) patients up to week 48; one was unlikely DILI and the other two were unrelated DILI—none met the criteria for potential Hy’s law or definite Hy’s law. There was one (0.8%) patient with a serious infection (meningitis) up to week 16 and up to week 48 (same patient); this event did not meet the opportunistic infection criteria. Three (2.3%) patients had non-serious herpes zoster (HZ) up to week 48.

With placebo, there were no deaths or AESIs up to week 16. Up to week 48, two (1.5%) patients in the placebo→tofacitinib group had non-serious HZ.

In the tofacitinib group, uveitis was reported in one (0.8%) patient up to week 16 and two (1.5%) patients up to week 48; both had history of uveitis. There were no AEs of psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), regardless of history.

In the placebo→tofacitinib group, uveitis was reported in three (2.2%) patients up to week 16 and four (2.9%) patients up to week 48 (one additional patient experienced uveitis after switching to tofacitinib), all with history of uveitis. Psoriasis was reported in one (0.7%) patient up to week 16 and up to week 48 (same patient), who had history of psoriasis. There were no AEs of IBD, regardless of history.

Up to week 16 and up to week 48, a higher proportion of patients in the placebo→tofacitinib versus the tofacitinib group had laboratory values meeting the protocol criteria for monitoring. Up to week 48, two (1.5%) patients in the tofacitinib group and no patients in the placebo→tofacitinib group had laboratory values meeting protocol criteria for discontinuation of study drug.

Up to week 48, mean haemoglobin, lymphocytes, neutrophils, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and cholesterol were stable over time; mean creatine kinase increased slightly over time (online supplemental figure S8).

There were no cases of COVID-19. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some cases of protocol deviation, discontinuation of study drug and withdrawal from the study (online supplemental table S1).

Discussion

In this phase III study of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day in patients with active AS, the ASAS20 response rate at week 16 (the primary endpoint) was significantly greater with tofacitinib versus placebo. These findings were supported by secondary efficacy endpoints, which demonstrated significant improvements with tofacitinib versus placebo in clinical measures and patient-reported outcomes relating to disease activity, mobility, function and health-related quality of life. Importantly, a rapid onset of clinical response (as early as week 2, the first post-baseline visit), including ASAS20 response, was seen in patients who received tofacitinib. Efficacy of tofacitinib was sustained up to the end of the open-label phase (week 48). In patients who advanced from placebo to tofacitinib at week 16, there was an improved clinical response between weeks 16 and 24, sustained up to week 48.

These efficacy findings are consistent with those from the phase II study of tofacitinib versus placebo in patients with AS.17 Two other JAK inhibitors, upadacitinib and filgotinib, have been investigated in patients with AS, with efficacy findings similar to those for tofacitinib. In the phase II/III study SELECT-AXIS 1, the ASAS40 response rate at week 14 was significantly greater with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily versus placebo (48 of 93 (52%) vs 24 of 94 (26%), p=0.0003; primary endpoint).19 In the phase II study TORTUGA, the mean (SD) ∆ASDAS at week 12 was significantly greater with filgotinib 200 mg once daily versus placebo (−1.47 (1.04) vs −0.57 (0.82), p<0.0001; primary endpoint).20

In descriptive analyses in this phase III study of tofacitinib, ASAS20/ASAS40 response rates at week 16 remained numerically greater with tofacitinib versus placebo when stratified by bDMARD treatment history (bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR or prior bDMARD use without IR); there was no statistical hypothesis testing for these subgroup analyses, and the smaller sample size at each subgroup level would limit statistical testing due to type II error.

The analysis of SJC(44) was limited by the small number of patients included, hence potentially larger type II error: at baseline, 33 and 38 patients had SJC(44) >0 in the tofacitinib and placebo groups, respectively. Furthermore, in patients with baseline MASES >0 or SJC(44) >0, a numerically higher proportion of patients had baseline csDMARD use in the placebo group versus the tofacitinib group (data not shown), which may partially explain the response seen in the placebo group and the lack of difference between tofacitinib and placebo in SJC(44).

AEs were more frequent with tofacitinib versus placebo, consistent with the phase II study of tofacitinib in patients with AS.17 The safety profile of tofacitinib, including laboratory changes, in patients with AS in this study was consistent with the established safety profile of tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day across all clinical programmes.10–16 In patients receiving tofacitinib, there were no deaths and no reported cases of malignancies (including NMSC), thromboembolic events, MACE, gastrointestinal perforation, DILI, opportunistic infections or ILD. Up to week 48, in the tofacitinib group, three (2.3%) patients had adjudicated hepatic events (one unlikely DILI, the other two unrelated DILI; none met the criteria for potential Hy’s law or confirmed Hy’s law), three (2.3%) patients had non-serious HZ and one (0.8%) patient had a serious infection (meningitis). Up to week 48 in the placebo→tofacitinib group, two (1.5%) patients had non-serious HZ.

Limitations of the study must be considered. The study population was relatively small. Additionally, the follow-up length of the study was relatively short to assess long-term efficacy and safety, including occurrence of AESIs. Furthermore, the study did not include image evaluation such as MRI improvement, which may need to be evaluated in future studies. In the phase II study of tofacitinib in patients with AS, significant improvements in MRI outcomes were observed for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus placebo.17

Currently, the unmet need for treatment options is high in patients with AS, including a need for effective oral treatment options following NSAIDs and a need for additional mechanisms of action. If approved by regulatory agencies, tofacitinib could be one of a new class of drugs for use in AS, providing an additional treatment option for patients with this disease.

In conclusion, in this phase III study, patients with active AS and an IR to NSAIDs had a rapid, sustained and clinically meaningful response to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day, with no new potential safety risks identified. This suggests a favourable benefit–risk balance in patients with active AS treated with tofacitinib.

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp003.pdf (37.4KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and investigators who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Presented at: Some data reported in this manuscript were previously presented at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence, 5–9 November 2020 (Deodhar A, Sliwinska‑Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of adult patients with ankylosing spondylitis: primary analysis of a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo‑controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72(Suppl 10):L11).

Contributors: AD: study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision and approval. PS-S: acquisition of data, manuscript revision and approval. HX: study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision and approval. XB, LF: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision and approval. LSG: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision and approval. DF, LW, JW, SM, CW, OD, KSK, DvdH: study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision and approval.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. The funder was involved in study design and data collection. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Sarah Piggott, MChem, CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, New York, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4). All authors, including those employed by the funder, had full access to all the data, revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: AD has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer Inc and UCB, and is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer Inc and UCB. PS-S and HX have no competing interests to declare. XB is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer Inc and UCB. LSG has received grant/research support from Pfizer Inc and UCB, and is a consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Novartis and UCB. DF, LW, JW, SM, CW, OD, LF and KSK are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. DvdH is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cyxone, Daiichi, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda and UCB, and is Director of Imaging Rheumatology BV.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-resultsformoreinformation), Pfizer will provide access to individual de-identified participant data from Pfizer-sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the USA and/or European Union or (2) in programmes that have been terminated (ie, development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de-identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was done in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, local regulatory requirements and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site.

References

- 1. Boel A, Molto A, van der Heijde D, et al. Do patients with axial spondyloarthritis with radiographic sacroiliitis fulfil both the modified New York criteria and the ASAS axial spondyloarthritis criteria? Results from eight cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1545–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dean LE, Jones GT, MacDonald AG, et al. Global prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2014;53:650–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61(Suppl 3):8iii–18. 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_3.iii8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poddubnyy D, Sieper J. Treatment of axial spondyloarthritis: what does the future hold? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:47. 10.1007/s11926-020-00924-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bohn R, Cooney M, Deodhar A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis: methodologic challenges and gaps in the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018;36:263–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS. 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:1285–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hodge JA, Kawabata TT, Krishnaswami S, et al. The mechanism of action of tofacitinib - an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:318–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Veale DJ, McGonagle D, McInnes IB, et al. The rationale for Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2019;58:197–205. 10.1093/rheumatology/key070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61424-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-Controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:495–507. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panés J, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in active ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:616–24. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1723–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brunner H, Synoverska O, Ting T. Tofacitinib for the treatment of polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71(Suppl 10):L22. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1340–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Machado P, Navarro-Compán V, Landewé R, et al. Calculating the ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score if the conventional C-reactive protein level is below the limit of detection or if high-sensitivity C-reactive protein is used: an analysis in the DESIR cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:408–13. 10.1002/art.38921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2378–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp001.pdf (2.3MB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2020-219601supp003.pdf (37.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-resultsformoreinformation), Pfizer will provide access to individual de-identified participant data from Pfizer-sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the USA and/or European Union or (2) in programmes that have been terminated (ie, development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de-identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.