Abstract

Objective.

Social isolation and loneliness are associated with increased mortality and higher health care spending in older adults. Hearing loss is a common condition in older adults and impairs communication and social interactions. The objective of this review is to summarize the current state of the literature exploring the association between hearing loss and social isolation and/or loneliness.

Data Sources.

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library.

Review Methods.

Articles were screened for inclusion by 2 independent reviewers, with a third reviewer for adjudication. English-language studies of older adults with hearing loss that used a validated measure of social isolation or loneliness were included. A modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality of the studies included in the review.

Results.

Of the 2495 identified studies, 14 were included in the review. Most of the studies (12/14) were cross-sectional. Despite the heterogeneity of assessment methods for hearing status (self-report or objective audiometry), loneliness, and social isolation, most multivariable-adjusted studies found that hearing loss was associated with higher risk of loneliness and social isolation. Several studies found an effect modification of gender such that among women, hearing loss was more strongly associated with loneliness and social isolation than among men.

Conclusions.

Our findings that hearing loss is associated with loneliness and social isolation have important implications for the cognitive and psychosocial health of older adults. Future studies should investigate whether treating hearing loss can decrease loneliness and social isolation in older adults.

Keywords: hearing loss, social isolation, loneliness, older adults

Social isolation and loneliness are distinct yet important measures of the psychosocial well-being of older adults. Social isolation is a measure of an individual’s social network size, number of social contacts, and frequency of engagement with social contacts, whereas loneliness is a subjective measure of an individual’s perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships.1 Both conditions are typically assessed through self-report. Social isolation and loneliness are common in older adults, with prevalence estimates of 24% for social isolation2 and estimates that range from 2% to 40% for loneliness.3,4 Both social isolation and loneliness have been linked to adverse health consequences, including mortality, cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, and depression.5–9 A meta-analysis found that stronger social relationships were associated with a 50% increased likelihood of survival, an effect size comparable with the effect of smoking and alcohol abuse on mortality.10 Moreover, the financial burden for older adults is substantial: loneliness has been shown to be associated with higher healthcare utilization,11 and lack of social contact among older adults is associated with $6.7 billion in additional federal Medicare spending annually.12

Age-related hearing loss is highly prevalent among older adults, such that two-thirds of adults older than 70 years have hearing loss.13 A growing body of evidence has linked age-related hearing loss to functional decline, depression, cognitive decline, and dementia.14–16 In fact, a recent report identified hearing loss as the largest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia, with a population attributable fraction of 9%.17 Social isolation and loneliness are hypothesized potential mechanisms through which hearing loss may be associated with worsened cognitive and mental health.18,19 Previous qualitative studies have suggested that older adults with hearing loss may feel frustration or embarrassment over their difficulty communicating, which may lead to withdrawal from social situations, resulting in social isolation and loneliness.20–22 Importantly, this hypothesized mechanistic pathway may be amenable to hearing aid treatment.

Perhaps because the relationship has been taken for granted by clinicians and researchers as self-evident, there are relatively few epidemiologic studies exploring hearing loss and social isolation and/or loneliness among older adults. Establishing hearing loss as a potentially modifiable risk factor for social isolation and/or loneliness among older adults would further highlight the importance of hearing loss in aging. In an effort to quantify the current state of the literature exploring the association between hearing loss and social isolation and/or loneliness, this article aims to systematically review and synthesize the literature on the association between hearing loss, social isolation, and loneliness in older adults.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

The study team performed a systematic search of PubMed (1946-) via NCBI, Embase (1947-) via Embase.com, CINAHL Plus (1961-) via EBSCOhost, PsycINFO (1967-) via EBSCOhost, and the Cochrane Library (from inception) on June 2, 2017. An updated search was performed on July 19, 2019. An informationist trained in performing database searches for systematic reviews developed the search strategy of relevant terms. The search strategies included controlled vocabulary, where appropriate, and keyword terms for the concepts of hearing loss, social isolation or loneliness, and older adults. The complete search strategies can be found in Supplemental Methods 1 (in the online version of the article). The initial search resulted in 3574 studies, of which 1079 were duplicates and removed, resulting in 2495 unique references.

Study Selection

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstract for each article according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if (1) they were original research studies, (2) participants were older adults (age >60 years), (3) participants had hearing loss (defined subjectively through self-report or objectively using audiometry or speech in noise tests), (4) they assessed loneliness and/or social isolation using any validated measure (including but not limited to the UCLA Loneliness Scale, De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius Loneliness Scale), and (5) they were English-language studies or foreign-language studies with English translation available. Studies were excluded if they included children or adults with prelingual deafness, did not use a validated measure of social isolation or loneliness, did not have a control group, or focused on an intervention comparing social isolation/loneliness before and after the intervention among persons with hearing loss. Conference abstracts, nonprimary research (reviews, editorials), and graduate theses were excluded.

Following title and abstract screening, the remaining studies underwent a full-text screen by 2 independent reviewers based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the 2 reviewers and adjudication by a third party with intimate knowledge of the systematic review design if necessary. Finally, the references of all included studies were also examined using an iterative title/abstract screen and full-text screen with the above inclusion and exclusion criteria to search for additional articles for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following data were extracted from all included studies: study design, study setting, baseline population characteristics, methods for hearing status assessment, and methods for loneliness and/or social isolation assessment. The results of each study on the relationship between hearing loss and social isolation and/or loneliness were summarized. In this review, all summary measures of the association between hearing loss and social isolation/loneliness were reported, including odds ratios, linear regression coefficients, and correlation coefficients. Extracted data were reviewed and adjudicated by 2 independent reviewers.

The strengths and limitations of each study with respect to sample characteristics and methods for exposure and outcome assessment were summarized. A modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the observational studies included in the review (Supplemental Methods 2 in the online version of the article). This modified NOS scale assess the quality of the study on the following domains: sample representativeness, sample size, assessment of hearing loss, comparability of respondents and nonrespondents, control for confounding factors, and appropriateness of statistical methods. Each domain was worth 1 point, and the total NOS score ranged from 0 to 6, with 0 suggesting a low-quality study and 6 suggesting a high-quality study.

Results

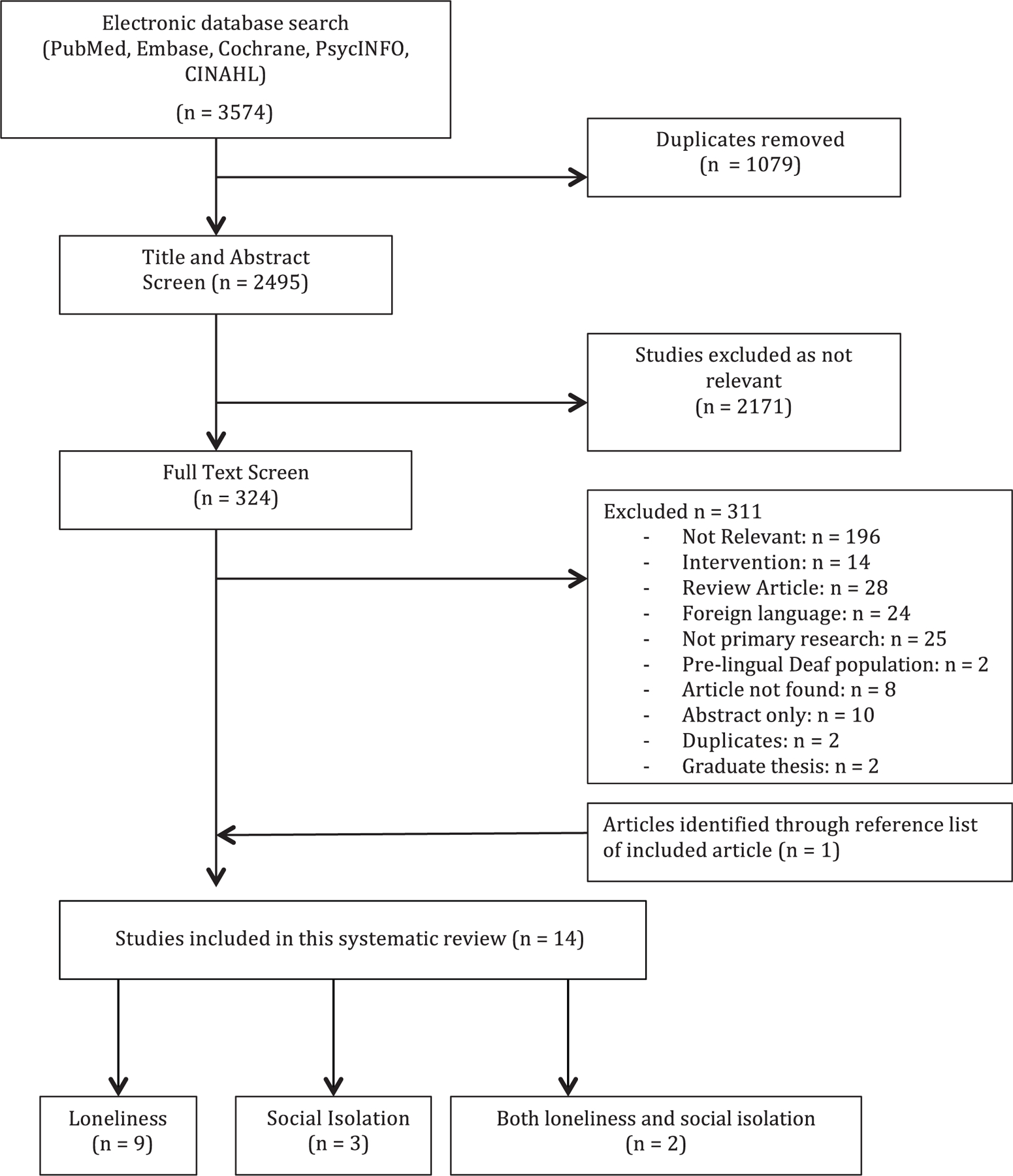

Of the initial 2495 unique articles identified, 2171 were excluded in the title and abstract screen and 324 were subsequently excluded in the full-text screen (Figure 1). The references of the 13 remaining studies were reviewed for relevant articles, and 1 additional study was identified through reference list review for inclusion. A total of 14 studies23–36 were included in the review, including 9 studies that assessed loneliness only, 3 studies that assessed social isolation only, and 2 studies that assessed both loneliness and social isolation in the same study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the key characteristics and findings of the studies included in this review. Included studies were published between 1982 and 2019. Of the included studies, 7 were in the United States,23,24,30,32–35 4 in the Netherlands,25–28 2 in Canada,29,36 and 1 in Japan.31 Most studies (12/14) were cross-sectional, and 2 were longitudinal in design. Most of the populations studied were community-based samples, and only 2 were clinic-based samples. Most of the studies (11/14) adjusted for potential confounding factors such as demographic and clinical characteristics, whereas 3 studies reported only unadjusted crude measures of association. The sample size of included studies ranged from 63 to 30,175 participants. Most studies included both men and women, but 1 study included men only32 and 2 studies reported results separately for men and women.29,35

Table 1.

Characteristics and Findings of Included Studies of Hearing Loss and Loneliness.

| Study | Sample | Hearing Assessment | Loneliness Assessment | Results | Study Strengths, Limitations, and Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen (1994)23 | N = 88, community-and clinic-based convenience sample; 65–90 y old; 51% male | HHIE | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Unadjusted correlational analysis showed a weak positive correlation between HHIE score and loneliness score (r = 0.23; P = .2) | Limitations: small convenience sample, unadjusted correlation between hearing and loneliness NOS score: 1 (high risk of bias) |

| Christian and Dluhy (1989)24 | N = 63, community-based sample of older adults living in housing units for the elderly | Tetratone audiometry at 4 frequencies | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Unadjusted analysis showed no statistically significant difference in mean loneliness scores between those who had serious/ severe HL and those who normal/mild HL (36 vs 32l, P = .097) | Limitations: small, nonrandom sample, only unadjusted t test NOS score: 1 (high risk of bias) |

| Kramer et al (2002)25 | N = 3107 participants from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, a community-based random sample; age range 55–85 y | Self-report: scaled score based on responses to 3 questions about hearing conversation and telephone with and without hearing aids | De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius 11-item loneliness scale | Hearing impairment associated with significantly higher loneliness scores using multivariable analysis of variance (2.5 vs 2.0, P <.01); in multiple linear regression, hearing impairment was associated with higher loneliness score (regression coefficient = 0.07, P <.001 | Strengths: large sample size, random sampling of underlying source population NOS score: 5 (low risk of bias) |

| Nachtegaal et al (2009)26 | N = 1511; clinic-based sample of participants from the ongoing National Longitudinal Study on Hearing 18–70 y old; mean age 46.3 y |

Speech in noise screening test taken online | De Jong Gierveld & Kamphuis 11-item Loneliness Scale | Overall, odds of severe or very severe loneliness increased by 7% for every dB SNR reduction in hearing status (OR 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.12); in the oldest age group (60–70 y), hearing status was not significantly associated with loneliness in adjusted analysis (OR 1.11; 95% CI, 0.94–1.32) | Limitations: had a small sample size for participants aged 60–70 y (n = 208) NOS score: 4 (low risk of bias) |

| Pronk et al (2011)27 | n = 996 participants with self-report hearing data; n = 830 participants with speech-in-noise hearing data from 2 waves of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam; community-based random sample | Self-report: scaled score based on responses to 3 questions about hearing conversation and telephone with and without hearing aids Speech-in-noise test |

De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius 11-item Loneliness Scale, divided into social loneliness (5 items) and emotional loneliness (6 items) | No significant association between self-reported hearing or speech-in-noise hearing and social loneliness; no association between self-reported hearing and emotional loneliness (log beta = .006, P = .376), but there was a significant association between speech-in-noise hearing and emotional loneliness (log beta = .002, P = .013) | Strengths: longitudinal analysis; 2 different hearing assessments Limitations: statistical definition of confounders, no correction for multiple tests in subgroup analysis NOS score: 5 (low risk of bias) |

| Pronk et al (2014)28 | N = 1607 participants from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam who were followed for 4 and 7 y; community-based random sample | Speech-in-noise test over telephone | De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius 11-item Loneliness Scale, divided into social loneliness (5 items) and emotional loneliness (6 items) | No overall association between rate of change in hearing status and rate of change in emotional or social loneliness (change in emotional loneliness: regression coefficient: 0.003, P = .880; change in social loneliness: regression coefficient: 0.030, P = .078) | Strengths: longitudinal analysis Limitations: selective loss to follow-up of older individuals, women, those with poorer hearing and psychosocial health, hearing aid users NOS score: 4 (low risk of bias) |

| Ramage-Morin (2016)29 | N = 30,175, community-based sample 45 y and older, mean age 60.4 y, 48% male |

Self-report: survey questions asking about difficulty hearing with or without a hearing aid in group conversations and in a quiet room | Three items from the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale and nonvalidated question on sense of community belonging | Perceived isolation (loneliness) associated with hearing difficulty in women (OR 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00–1.09) but not in men (OR 1.00; 95% CI, 0.97–1.04) | Strengths: large, nationally representative sample Limitations: proxy respondents were excluded and were more likely to have HL NOS score: 4 (low risk of bias) |

| Sung et al (2016)30 | N = 145, clinic-based sample of patients presenting for hearing aids or cochlear implants; 50 y and older, 57% male | Pure-tone audiometry to measure PTA averages at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Each 10-dB increase in PTA was associated with a 1.43-point increase in UCLA loneliness score (95% CI, 0.67–2.20; P < .001); severe/profound HL (>70 dB PTA) associated with UCLA scores 13.6 higher compared than normal hearing (95% CI, 6.10–21.17; P < .001) | Strengths: audiometric hearing assessment Limitations: sample of patients not generalizable NOS score: 3 (low risk of bias) |

| Tomioaka et al (2012)31 | N = 1761, community-based nonrandom sample, volunteers recruited from neighborhood associations in 2 Japanese cities; 60 y and older, 44% male | Self-report: SQ: “Do you feel you have hearing loss”; hearing handicap measured using HHIE-S, with score of >8 considered a hearing handicap | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale; upper tertile defined as having loneliness | Those with positive HHIE-S only and with positive HHIE-S and positive SQ had increased odds of loneliness compared with those with no HL by either measure (OR 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4–3.4; and OR 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4–2.4, respectively); those with positive SQ only had no significant increase in loneliness (OR 1.1; 95% CI, 0.7–1.6) | Strengths: 2 different self-reported hearing assessments, large sample size Limitations: only recruited individuals who were living on their own and could walk on their own, may limit generalizability NOS score: 4 (low risk of bias) |

| Weinstein and Ventry (1982)32 | N = 80 male veterans recruited through outpatient centers at a Veterans Affairs medical center; age range 65–88 y, mean age 74 y | Pure tone audiometry; hearing handicap using the HMS; speech detection test using the W-22 PB work list and the Rush-Hughes PB-50 word list | Subjective Isolation Scale from the Comprehensive Assessment and Referral Evaluation (CARE) questionnaire | Subjective isolation (loneliness) was positively correlated with all measures of hearing: HMS (r = 0.52), PTA (r = 0.39), Rush-Hughes word list (r = 0.42), and W-22 word list (r = 0.25) | Limitations: male veterans only, so results nongeneralizable; unadjusted correlations between hearing and loneliness with no control for relevant confounders NOS score: 1 (high risk of bias) |

| Wells et al (2019)35 | N = 20,244 men and women aged 65 y and older | Self-report based on answer to question: “Which statement best describes your hearing without a hearing aid?” | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Among both men and women, mild and severe HL was associated with loneliness; OR of loneliness among women with mild HL = 1.51 (1.35, 1.68) and moderate HL = 1.35 (1.16, 1.58); OR of loneliness among men with mild HL = 1.18 (1.03, 1.35) and moderate HL = 1.19 (1.01, 1.41); there was significant effect modification by gender; use of hearing aids was not associated with decreased loneliness | Strengths: large sample size Limitations: overall survey response rate of 18%; surveys conducted over telephone, which could lead to decrease participation from those with HL NOS score: 5 (low risk of bias) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HHIE, Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly; HL, hearing loss; HMS, Hearing Measurement Scale; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; OR, odds ratio; PTA, pure-tone average; SQ, single question.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Findings of Included Studies of Hearing Loss and Social Isolation.

| Study | Sample | Hearing Assessment | Loneliness Assessment | Results | Study Strengths, Limitations, and Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kramer et al (2002)25 | N = 3107 participants recruited from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, a community-based random sample; age range 55–85 y | Self-report: scaled score based on responses to 3 questions about hearing conversation and telephone with and without hearing aids, dichotomized for analysis | Size of the social network (7 domains of network members with whom respondent maintained a regular relationship) | Hearing loss associated with smaller network (12.7 vs 14.1, P <.01); in multiple linear regression, hearing impairment associated with lower network size (regression coefficient = −0.52, P <.01) | Strengths: large sample size, random sampling of underlying source population NOS score: 5 (low risk of bias) |

| Mick et al (2014)33 | N = 1453 participants from the 1999 to 2006 cycle of the NHANES, a community-based random sample; age range 60–84 y | Pure-tone audiometry to measure PTA at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz | A summary social isolation score (SIS) based on the SSQ | Among 60- to 69-y-olds, odds of social isolation was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.29–3.57) higher per 25 dB of hearing loss; there was an interaction with gender (women: OR 3.49; 95% CI, 1.91–6.39; men: OR: 1.11; 95% CI, 0.66–1.88); among 70- to 84-y-olds, there was no significant increase in odds of social isolation with each 25-dB increase in hearing loss (OR 1.24; 95% CI, 0.75–2.0) | Strengths: random sample of participants, audiometric measure of hearing Limitations: NHANES SSQ questionnaire and SIS have not been standardized NOS score: 5 (low risk of bias) |

| Mick et al (2018)36 | N = 21,241 community-dwelling older adults age 45–89 y, a nationally representative sample from the Canadian Longitudinal Study of Aging | Self-reported hearing status based on the following question: “Is your hearing, using a hearing aid if you use one: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor or Nonexistent or deaf” | Social network diversity determined using a modified version of the SNI; availability of social support measured using the Medical Outcomes Social Support Survey | Hearing loss was not associated with social network diversity (mean difference in SNI score between those with hearing loss and those without = 0.02, 95% CI, 0.06, 0.10); hearing loss was associated with having a social support score lower than the median (OR 1.22; 95% CI, 1.10, 1.25) | Strengths: large sample size, nationally representative sample; used multiple validated measures of social isolation and social support NOS score: 5 |

| Mick and Pichora-Fuller (2016)34 | N = 1820 participants from the 1999 to 2010 cycles of NHANES | Self-reported hearing status, hearing test history, and hearing aid use; pure-tone audiometry; participants categorized as having unacknowledged hearing loss (PTA >25 dB but self-reported normal hearing) and as having unaddressed hearing loss (PTA >25, self-reported hearing difficulty but no hearing test or hearing aid use) | A summary SIS based on SSQ: not married or in a domestic partnership, no close friends, no one to provide financial support, no one to provide emotional support; participants were considered isolated if they met 2 of the above criteria | A 10-dB increase in PTA was associated with 1.52 higher odds of social isolation among 60- to 69-yolds with unacknowledged or unaddressed hearing loss (OR: 1.52; 95% CI, 1.19–1.93); there was no association between higher odds of social isolation with each 10-dB increase in PTA among 701 y olds (OR 1.08; 95% CI, 0.77–1.52) | Strengths: random sample of participants, audiometric measure of hearing Limitations: NHANES SSQ questionnaire and SIS have not been standardized; did not look at participants with treated hearing difficulty NOS score: 5 |

| Weinstein and Ventry (1982)32 | N = 80 male veterans recruited through outpatient centers at a Veterans Affairs medical center; age range 65–88 y, mean age 74 y | Pure-tone audiometry; hearing handicap using the HMS; speech detection test using the W-22 PB work list and the Rush-Hughes PB-50 word list | Objective Isolation Scale from the Comprehensive Assessment and Referral Evaluation (CARE) Questionnaire | Objective isolation was positively correlated with all measures of hearing: HMS (r = 0.26), PTA (r = 0.24), Rush-Hughes word list (r = 0.22), and W-22 word list (r = 0.18 | Limitations: male veterans only, findings nongeneralizable; unadjusted correlations between hearing and loneliness with no control for relevant confounders NOS score: 1 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HMS, Hearing Measurement Scale; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; OR, odds ratio; PTA, pure-tone average; SIS, social isolation score; SNI, Social Network Index; SSQ, Social Support Questionnaire.

There was substantial heterogeneity in the measurement of hearing status. Three studies measured hearing status using pure-tone audiometry,30,32,33 1 used tetratone audiometry,24 2 used a speech-in-noise test,26,28 and 6 used self-report (either a single question, multiple questions, or the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly).23,25,28,29,35,36 Two studies used a combination of methods to measure hearing status, including both self-report and the speech-in-noise test27 and both audiometry and self-report.34 Seven of the included studies assessed hearing aid use through self-report.26–29,31,33,35

Most of the included studies scored between a 4 and 5 on our modified NOS quality assessment scale and were of high quality. Studies that scored lowest on our quality assessment scale did so because they had an unrepresentative or small sample size and did not control for confounding factors in their statistical analyses.23,24,32

Hearing Loss and Loneliness

Overall, there were 11 studies that assessed the association between hearing loss and loneliness (Table 1). Of these, 9 were cross-sectional and 2 longitudinal. There was heterogeneity in assessment of loneliness: 4 studies used the De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius 11-item Loneliness Scale,25–28 4 studies used the 20-item revised UCLA Loneliness Scale,23,24,30,31 2 used 3 items from the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale,29,35 and 1 used the subjective isolation scale from the Comprehensive Assessment and Referral Evaluation (CARE) questionnaire.32 The De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius Loneliness Scale has 11 items that are answered on a 3-point scale, with higher scores indicating more loneliness.37 The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale consists of 20 items that assess how often the participant has felt certain emotions, with scores ranging from 1 to 4 for each question and higher scores signifying increased loneliness.38

Six of the 9 cross-sectional studies found increased loneliness among older adults with hearing loss compared with those with normal hearing.25,29–32,35 Of these, 5 were multivariable adjusted analyses25,29–31,35 and 1 was an unadjusted correlational analysis.32 One cross-sectional study found that older adults with self-perceived hearing handicap (score >8 on the Hearing Handicap Inventory of the Elderly [HHIE]) had 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–3.4) times the odds of loneliness compared with those without a hearing handicap.31 Another cross-sectional study found that objectively measured hearing loss was associated with increased loneliness, such that each 10-dB increase in pure-tone average (PTA) was associated with a 1.43 increase in the UCLA loneliness score (95% CI, 0.67–2.20).30 They also found that those with severe or profound hearing loss (defined as a PTA of ≥70-dB hearing level in the better-hearing ear) had UCLA loneliness scores 13.6 points higher (95% CI, 6.10–21.17) than those with normal hearing but with a wide confidence interval due to a small sample size of participants with severe or profound hearing loss.30 One of the cross-sectional studies assessed men and women separately and found that loneliness was associated with self-reported hearing difficulty in women (OR 1.04; 95%, CI 1.00–1.09) but not in men (OR 1.00; 95% CI, 0.97–1.04).29 Another study that assessed men and women separately found that there was an effect modification by gender on the effect of hearing loss on loneliness, with a stronger association between hearing loss and loneliness observed among women (women with mild hearing loss: OR 1.51, 95% CI, 1.35–1.68; women with moderate hearing loss: OR 1.35, 95% CI, 1.16–1.58; men with mild hearing loss: OR 1.18, 95% CI, 1.03–1.35; men with moderate hearing loss: OR 1.19, 95% CI, 1.01–1.41).35

Three of the 9 cross-sectional studies did not find an association between hearing and loneliness. Notably, 2 of the 3 were unadjusted crude analyses23,24 with a low score on our quality assessment scale, and only 1 was a multivariable adjusted analysis.26 In the multivariable analysis, the authors found no significant association between hearing loss and loneliness in the subgroup of older adults aged 60 to 70 years (OR 1.11; 95% CI, 0.94–1.32; n = 208) although they did find a significant association in the overall population of adults aged 18 to 70 years (OR 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01–1.12).26 Notably, this study used an Internet-based speech-in-noise test to measure hearing status, whereas the other studies on hearing loss and loneliness that did find an association used either self-report or audiometric hearing assessment.

There were 2 longitudinal studies of hearing loss and loneliness, both within the same cohort of older adults enrolled in the Longitudinal Aging Study, Amsterdam.27,28 In both of these studies, loneliness was measured using the 11-item De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius scale, divided into social loneliness (5 items, related to deficits in social integration) and emotional loneliness (6 items, related to absence of intimate attachments with friends and family) subscales. In 1 study, the authors assessed whether hearing loss at baseline (measured through both self-report and objectively with a speech-in-noise test) led to increased loneliness over 4 years of follow-up.27 They found no significant association between either self-reported or objectively measured hearing status and social loneliness or between self-report hearing status and emotional loneliness, but they did find an association between objectively measured hearing status and emotional loneliness.27 In the other study, hearing status was measured with a speech-in-noise test, and the authors examined whether the rate of change in hearing (measured as the change in decibels of hearing level at which participants could understand 50% of speech correctly) was associated with the rate of change in loneliness (measured as the change in the social and emotional loneliness subscales of the De Jong Gierveld & Kamphius scale) over 4 years of follow-up. They found no significant association between rate of change in hearing and rate of change in either social or emotional loneliness.28

Hearing Loss and Social Isolation

Overall, 5 cross-sectional studies examined the association between hearing loss and social isolation (Table 2). Two of the studies measured social isolation using a composite social isolation score based on the Social Support Questionnaire in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).33,34 One study used the objective isolation scale from the CARE questionnaire,32 1 defined the size of the social network as a measure of social isolation,25 and 1 study used both a modified version of the Social Network Index and the Medical Outcomes Social Support Survey.36 Four studies were multivariable-adjusted analyses, while 1 was an unadjusted correlational analysis.

All 5 studies found increased social isolation in older adults with hearing loss compared with those with normal hearing. One study found that self-reported hearing loss was associated with a smaller social network size.25 In another study of self-reported hearing loss, hearing status was not associated with social network diversity but was associated with having a lower than median social support score.36

Two studies of objectively measured hearing in nationally representative NHANES samples found that hearing loss was associated with a higher odds of social isolation. These studies found that among 60- to 69-year-olds, hearing loss was associated with a higher odds of social isolation (OR 2.14; 95% CI, 1.29–3.57),33 and each 10-dB increase in PTA was associated with 1.52 times (95% CI, 1.19–1.93) higher odds of social isolation.34 The authors also found a significant interaction with gender, such that hearing loss was associated with social isolation in women (OR 3.49; 95% CI, 1.91–6.39) but not in men (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.66–1.88).34

Discussion

In this systematic review of 14 studies, most included studies found that hearing loss was associated with loneliness and social isolation in older adults. These results highlight that hearing loss may have important implications for the psychosocial and cognitive health of older adults.

In this review, we found that hearing loss was more consistently associated with social isolation than with loneliness. Despite a heterogeneity of measures to assess isolation, all 5 cross-sectional studies of social isolation found that older adults with hearing loss were more likely to be socially isolated. In contrast, of the 11 studies on loneliness, 6 of the 9 cross-sectional and 1 of the 2 longitudinal studies found that older adults with hearing loss were more likely to report loneliness. This may reflect that while hearing loss can be socially isolating because of decreased participation in activities or a smaller social network, this may not lead to loneliness in all older adults who experience social isolation. Loneliness is an emotional response to a perceived discrepancy between actual and desired levels of social connection.39 Older adults may not feel lonely despite isolation from others if they believe it to be a normal part of the aging process or if they prefer a smaller social network as they age.40 Studies have found that social isolation and loneliness in older adults are weakly correlated with one another, suggesting that the two are related yet distinct constructs.41

There are several potential mechanisms that could explain the observed association between hearing loss and social isolation and loneliness. Age-related hearing loss degrades peripheral auditory processing by the cochlea, impairing an individual’s ability to comprehend auditory information and making conversations more difficult to follow.42,43 Difficulty following conversations can lead to frustration and may result in older adults avoiding potentially embarrassing social situations, particularly those with large groups or loud background noises.20 Degraded auditory processing by the cochlea may also lead to increased cognitive load and depleted cognitive reserve for social activity and interactions.44

There were some gender-based differences in the association between hearing and social isolation and loneliness in the studies included in this review. Most notably, one of the included studies found that hearing loss was associated with a higher odds of loneliness in older women but not in older men,29 while 2 other studies found a significant interaction between gender and hearing loss on loneliness35 and social isolation.34 This may represent the varied emotional responses an individual with hearing loss may have to the new communicative challenges in social settings. Compared with men, women have been found to rely more heavily on verbal communication to establish and maintain social connections.45 Thus, older women may be more vulnerable to be socially and emotionally affected by being less connected with their social environment as a result of degraded auditory processing. Another possibility is that women may be more likely to report feelings of loneliness or decreased social support than men.

The association between hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation has important implications. The emerging literature has hypothesized that reduced social engagement and loneliness might lie on the mechanistic pathway linking hearing loss to cognitive decline.18,46 Loneliness and social isolation may also contribute to worsened mental health among older adults with hearing loss, including depression and psychological distress.16,47 Importantly, both conditions in older adults have been linked to higher health care utilization and costs,11,12 and thus identifying potentially modifiable risk factors for social isolation and loneliness is important. This review focused on observational studies of both treated and untreated hearing loss. We did not assess whether treating hearing loss through the use of hearing aids has an impact on social isolation and loneliness, and this remains an area for future study.

We note several limitations of this review. Only 14 studies met our inclusion criteria, and there was substantial heterogeneity in the measures used to assess social isolation, loneliness, and hearing status. We were unable to perform a meta-analysis of the included studies given the heterogeneity of response measures in the included studies. Several of the included studies assessed hearing status as well as social isolation and loneliness through self-report, which could result in the same source bias. We included studies with both subjective and objective assessments of hearing status, as self-reported assessments of hearing have been found to be well correlated with hearing loss measured by pure-tone audiometry.48 There were only 2 longitudinal studies assessing risk of incident loneliness with hearing loss and no longitudinal studies of social isolation and hearing loss. Thus, we cannot determine whether the observed associations are causal. Finally, we excluded studies that used nonvalidated measures of social isolation and loneliness (such as single questions, institutionally derived nonvalidated scales) and therefore may not have captured the entire extent of the literature on this relationship.

Conclusion

To the study team’s knowledge, this is the first systematic review that synthesizes the literature on the quantitative association between hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation in older adults. The current literature is heterogeneous, but important conclusions emerge. Several cross-sectional studies across various populations found an association between hearing loss and increased loneliness and social isolation. Older women with hearing loss were more likely to report social isolation than men in some studies, suggesting a potential gender effect on this relationship. The findings of this review have important implications for the cognitive, mental, and psychosocial health of older adults with hearing loss. Future longitudinal studies are required to establish whether there is a causal association between hearing loss and increased risk of social isolation and loneliness. This review did not assess whether treatment of hearing loss improves social isolation and loneliness in those with hearing loss. Future research should also extend into determining the role of hearing care, such as aural rehabilitation and hearing aids, in decreasing social isolation and loneliness among older adults with hearing loss.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: None

Footnotes

Disclosures

Competing interests: Adele Goman is a consultant to Cochlear Americas Ltd and to Auditory Insight. Frank R. Lin is a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Amplifon, and Cochlear; receives speaker fees from Caption Call; is a board member for Access Hears; has received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation during the conduct of the study; and is the director of a research center based at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health funded in part by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear Ltd. Nicholas S. Reed is a scientific advisor (nonfinancial) to Shoebox, Inc and consultant to Helen of Troy.

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information is available in the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(1):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cudjoe TK, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ. The epidemiology of social isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;75(1):107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenger GC, Davies R, Shahtahmasebi S, Scott A. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: review and model refinement. Ageing Soc. 1996;16(3):333–358. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victor CR, Bowling A. A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. J Psychol. 2012;146(3): 313–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gopinath B, Rochtchina E, Anstey KJ, Mitchell P. Living alone and risk of mortality in older, community-dwelling adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):320–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of alameda county residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxman TE, Berkman LF, Kasl S, Freeman DH Jr, Barrett J. Social support and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(4):356–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar A, Hamer M, McMunn A, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(2):161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13): 1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7): e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flowers L, Houser A, Noel-Miller C, et al. Medicare spends more on socially isolated older adults. Insight on the Issues. 2017;125.

- 13.Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the united states. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1851–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liljas AE, Carvalho LA, Papachristou E, et al. Self-reported hearing impairment and incident frailty in English community-dwelling older adults: a 4-year follow-up study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):958–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deal JA, Reed NS, Kravetz AD, et al. Incident hearing loss and comorbidity: a longitudinal administrative claims study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;145(1):36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113): 2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutherford BR, Brewster K, Golub JS, Kim AH, Roose SP. Sensation and psychiatry: linking age-related hearing loss to late-life depression and cognitive decline. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;175(3):215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin FR. Hearing loss in older adults: who’s listening? JAMA. 2012;307(11):1147–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heine C, Browning CJ. The communication and psychosocial perceptions of older adults with sensory loss: a qualitative study. Ageing Soc. 2004;24(1):113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnick HE, Fries BE, Verbrugge LM. Windows to their world: the effect of sensory impairments on social engagement and activity time in nursing home residents. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(3):S13–S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barker AB, Leighton P, Ferguson MA. Coping together with hearing loss: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the psychosocial experiences of people with hearing loss and their communication partners. Int J Audiol. 2017;56(5):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen HL. Hearing in the elderly: relation of hearing loss, loneliness, and self-esteem. J Gerontol Nurs. 1994;20(6):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christian E, Dluhy N. Sounds of silence coping with hearing loss and loneliness. J Gerontol Nurs. 1989;15(11):4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer SE, Kapteyn TS, Kuik DJ, Deeg DJ. The association of hearing impairment and chronic diseases with psychosocial health status in older age. J Aging Health. 2002;14(1):122–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nachtegaal J, Smit JH, Smits C, et al. The association between hearing status and psychosocial health before the age of 70 years: results from an Internet-based national survey on hearing. Ear Hear. 2009;30(3):302–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pronk M, Deeg DJ, Smits C, et al. Prospective effects of hearing status on loneliness and depression in older persons: identification of subgroups. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(12):887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pronk M, Deeg DJ, Smits C, et al. Hearing loss in older persons: does the rate of decline affect psychosocial health? J Aging Health. 2014;26(5):703–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramage-Morin PL. Hearing Difficulties and Feelings of Social Isolation among Canadians Aged 45 or Older. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sung Y, Li L, Blake C, Betz J, Lin FR. Association of hearing loss and loneliness in older adults. J Aging Health. 2016; 28(6):979–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomioka K, Ikeda H, Hanaie K, et al. The Hearing Handicap Inventory for Elderly-Screening (HHIE-S) versus a single question: reliability, validity, and relations with quality of life measures in the elderly community, Japan. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(5):1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstein BE, Ventry IM. Hearing impairment and social isolation in the elderly. J Speech Hear Res. 1982;25(4):593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 2014;150(3):378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mick P, Pichora-Fuller MK. Is hearing loss associated with poorer health in older adults who might benefit from hearing screening? Ear Hear. 2016;37(3):e19–e201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells TS, Nickels LD, Rush SR, et al. Characteristics and health outcomes associated with hearing loss and hearing aid use among older adults [published online May 16, 2019]. J Aging Health. doi: 10.1177/0898264319848866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Mick P, Parfyonov M, Wittich W, Phillips N, Pichora-Fuller MK. Associations between sensory loss and social networks, participation, support, and loneliness: analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(1): e33–e41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuls F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1985;9(3):289–299. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peplau LA. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. Vol 36. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Social and emotional aging. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61(1):383–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pichora-Fuller MK. Cognitive aging and auditory information processing. Int J Audiol. 2003;42(suppl 2):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peelle JE, Troiani V, Grossman M, Wingfield A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. J Neurosci. 2011;31(35):12638–12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tun PA, McCoy S, Wingfield A. Aging, hearing acuity, and the attentional costs of effortful listening. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(3):761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maltz DN, Borker RA. A cultural approach to male-female miscommunication. In: Monaghan L, Goodman JE, Robinson JM, eds. A Cultural Approach to Interpersonal Communication: Essential Readings. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 1982: 168–185. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray J, Popli G, Fell G. Association of cognition and age-related hearing impairment in the English Longitudinal Studyof Ageing. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(10): 876–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Association of audiometric age-related hearing loss with depressive symptoms among Hispanic individuals. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;145(2):132–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Smith W, et al. Validation of self-reported hearing loss: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.