Abstract

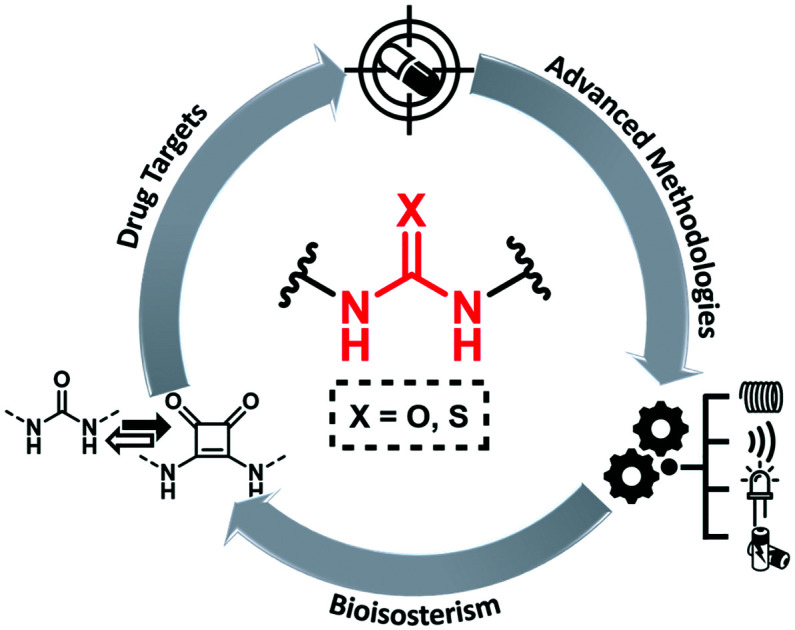

Urea and thiourea represent privileged structures in medicinal chemistry. Indeed, these moieties constitute a common framework of a variety of drugs and bioactive compounds endowed with a broad range of therapeutic and pharmacological properties. Herein, we provide an overview of the state-of-the-art of urea and thiourea-containing pharmaceuticals. We also review the diverse approaches pursued for (thio)urea bioisosteric replacements in medicinal chemistry applications. Finally, representative examples of recent advances in the synthesis of urea- and thiourea-based compounds by enabling chemical tools are discussed.

Urea and thiourea represent privileged structures in medicinal chemistry.

Introduction

Urea and thiourea represent well-established privileged structures in medicinal and synthetic chemistry. These structural motifs constitute a common framework of a variety of drugs and bioactive compounds endowed with a broad range of therapeutic and pharmacological properties,1,2 such as anti-viral, anti-convulsant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and anti-tumor effects.3–8

Urea is a natural compound produced in many organisms from the metabolism of proteins and other nitrogen-containing compounds during the so called “urea cycle” in the liver. In 1828, the first synthesis of urea was realized by the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler showing, for the first time, that a substance, previously known only as an organic waste product, could be synthesized from inorganic starting materials in the laboratory.9 This discovery overturned the widely held doctrine vitalism and was a breakthrough in different chemical fields including organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry.10–12

Thiourea was synthesized for the first time in 1873 by the Polish chemist Marceli Nencki as the first urea analogue characterized by the replacement of the oxygen atom with a sulfur atom. The (thio)urea functionality plays a central role in medicinal chemistry thanks to the possibility of establishing stable hydrogen bonds with recognition elements of biological targets, such as proteins, enzymes and receptors. Indeed, a hydrogen bond network is a key element enabling the stabilization of ligand–receptor interactions and the bioactive site recognition; an example is highlighted in Fig. 1.

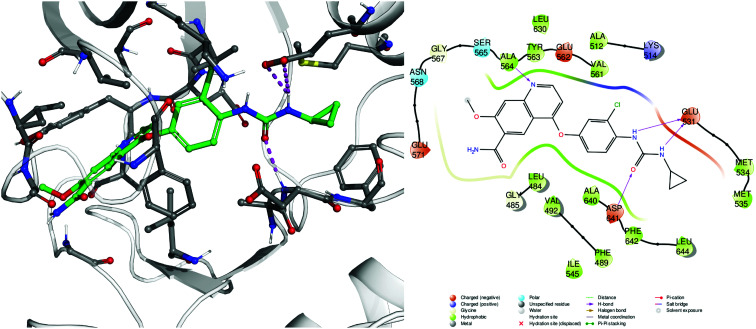

Fig. 1. Example of protein–ligand interactions, 3D (left) and 2D (right), engaged by an antitumor urea-containing drug, lenvatinib (2), complexed with one of its biological targets FGFR-1 (fibroblast growth factor receptor-1, pdb code 5ZV2).13 The urea moiety is able to engage multiple hydrogen bond interactions (magenta dashed lines and arrows) with the carboxylic moiety of Glu531 and the Asp641 backbone nitrogen.

Given this great importance, a variety of urea and thiourea-containing compounds have been approved as marketable drugs by the FDA, EMA and other agencies for the treatment of different human diseases and, thus, promising drug candidates are currently in development by pharmaceutical and academic researchers.1

Here, we review the status of urea- and thiourea-containing approved drugs, including antitumor, chemotherapeutic agents, and central nervous system (CNS) drugs. We then discuss the potential of bioisosteric replacement approaches in medicinal chemistry as well as the ongoing efforts on modern methods for the generation of urea and thiourea scaffolds by means of enabling chemical technologies such as flow chemistry, photo- and electro-chemistry, microwave and ultrasound irradiations.

Urea- and thiourea-containing approved drugs

As a prototype of urea-containing approved drugs, sulfanylureas are certainly the most exploited. This class of well-known drugs has been used in therapy for about half a century for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, being able to stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. Likewise, it is possible to cite many other examples. In the following sections, we mainly reviewed drug candidates or approved drugs developed in the past two decades.

Antitumor agents

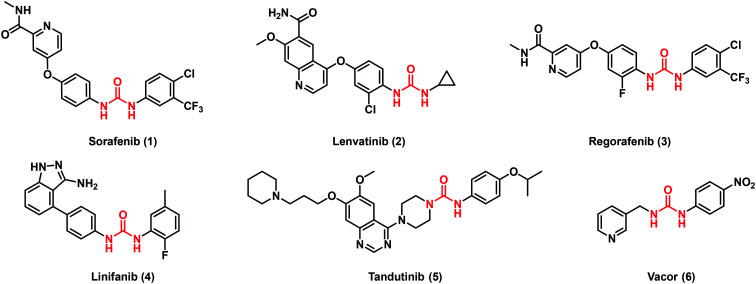

In the last twenty years, considerable efforts have been directed toward the design of antitumor agents containing the (thio)urea scaffold, especially in the field of kinase inhibitors. Among the so far approved drugs, sorafenib (1), lenvatinib (2) and regorafenib (3) are worthy to be cited (Fig. 2). These drugs possess non-selective kinase inhibitor activities acting on different molecular pathways where their over-expression is mainly involved in the transformation of normal cells into uncontrolled proliferative cells.14

Fig. 2. Representative examples of urea-containing antitumor agents.

Sorafenib (1) is a diaryl urea produced by Bayer and Onyx Pharmaceuticals and was initially approved in 2005 for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma, and two years later, for hepatocellular carcinoma in the sorafenib hepatocellular carcinoma assessment randomized protocol or SHARP trial.15 This drug is classified as an oral multi-target receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), being able to recognize and interact with several isoforms of this class of enzymes. The majority of TKIs acts as ATP-mimic compounds through the establishment of hydrogen interactions with the conserved kinase hinge residues. Notable examples are diaryl ureas whereby the hydrogen bond networks and the aromatic rings fit perfectly inside a hydrophobic pocket, close to the ATP-binding site region, keeping the enzymes in an inactive conformation.16 In particular, the ATP pocket consists of a hinge region containing the gatekeeper residue, the P-loop, the C-helix and the activation loop made by the conserved DEG motif. Accordingly, TKIs are commonly constituted by i) a nitrogen urea moiety able to form H-bonds with the hinge region; ii) a hydrophobic moiety interacting with the hydrophobic region I of the kinase (i.e. aromatic rings); iii) a spacer.17

Lenvatinib (2) by Eisai Co. was approved in 2015 for the treatment of peculiar thyroid cancers such as non-radioiodine responsive ones. In 2016, FDA approved this compound for new therapeutic applications such as the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma in combination with everolimus (an immunosuppressive drug) and hepatocellular carcinoma.18 Interestingly, in both drugs 1 and 2, the urea moiety plays a key role in the molecular recognition with the kinase target at the level of the hinge region as above cited. Indeed, the X-ray analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) complexed with these molecules revealed that the urea scaffold promoted a hydrogen bond network with the Asp1046 backbone and Glu885 side-chain.19 Moreover compound 2 is able to inhibit fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR-1)13 by establishing multiple hydrogen bond interactions with both the carboxylic moiety of Glu531 and the Asp641 backbone nitrogen (Fig. 1). Regorafenib (3), developed by Bayer, is a fluorinated sorafenib analogue which targets angiogenic, stromal and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). It was approved in 2012 for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer and three years later for advanced gastrointestinal tumors. Its use was, then, expanded also to treat hepatocellular carcinoma.20

Despite the potential clinical applications of 1, novel TKIs have been developed to overcome compound limitations such as poor solubility, rapid metabolism and resistance issues. Among them, linifanib (4) and tandutinib (5) reached the clinical phases as promising anti-cancer agents (Fig. 2).

Linifanib (4) is a ureido indazole derivative with a selective inhibitory activity towards VEGFR (growth factor receptor) and PDGFR (platelet derived growth factor receptor). It reached phase II clinical trials for patients affected by locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer.21 The 3-aminoindazole motif is a new TKI template able to mimic the adenine component of ATP establishing a pair of H-bonding interactions with the kinase hydrophobic pocket. Moreover, the insertion of a diaryl urea confers an additional H binding site favouring the correct orientation of the urea moiety within the pocket and leading to the receptor inactivation.22

Tandutinib (5) is a piperazinyl ureidic derivative in clinical trials for recurrent or progressive glioblastoma and acute leukaemia.23 It inhibits FLT3 (FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3) phosphorylation reducing the malignant growth in vitro and in animal models. 5 displayed interesting antileukemic activity (90% complete remissions) in a phase I/II trial of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) when administered in combination with cytarabine and daunorubicin.23

In search of novel antitumor agents, Chiarugi and collaborators screened compounds bearing the pyridinylmethylurea moiety and identified Vacor (6, Fig. 2), an old rodenticide, as a potent NAD depleting agent.24 The researchers found that Vacor is transformed by the enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) into Vacor mononucleotide (VMN, 7) which, in turn, can then be converted by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 (NMNAT2) into the NAD analogue Vacor adenine dinucleotide (VAD, 8, Fig. 3). In this case, as argued from the docking studies, the ureidic linker oriented the interactions of the ligand within the catalytic site of the NAMPT enzyme. It is worth noting that the biotransformation of Vacor prompts the concomitant inhibition of NAMPT, NMNAT2 and several NAD-dependent dehydrogenases, leading to an unprecedented rapid NAD depletion, thus contributing to energy failure and necrotic cell death. This action was found to be selective since only NMNAT2-expressing cancer cells were involved, discovering an innovative antitumor strategy.24

Fig. 3. Vacor metabolic pathway.

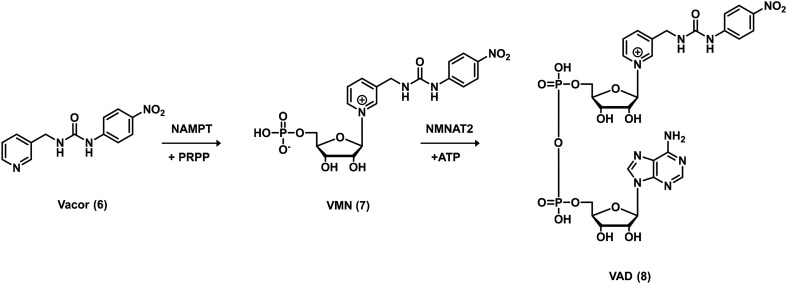

Chemotherapeutic agents

A plethora of (thio)urea-containing drugs is commonly used in treatment of infections as anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-fungal, anti-helminthic and anti-parasitic agents.

In this framework, an early example of urea derivatives was a trypan red analogue (9) from the pioneering work of the Nobel laureate and German physician Paul Ehrlich (Fig. 4). This dye with anti-trypanosomal activity laid the basis for modern chemotherapy. Further optimization led to the discovery of suramin (10), a polysulfonated naphthylureidic drug that is still used in therapy during the early stage of sleeping sickness in humans caused by the trypanosomes gambiense and rhodesiense. Although its discovery dates back to the 19th century, 10 is still under investigation for the treatment of various cancers, viral infections and autism syndrome.25

Fig. 4. Chemical structures of selected urea and thiourea compounds used in therapy as chemotherapeutic agents.

Some thiourea derivatives were used to treat Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections, including thioacetazone (11) and thiocarlide (12) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, some adamantyl urea derivatives were also designed for the treatment of this particular infection. SAR studies demonstrated that the urea moiety was fundamental for the activity and the replacement with other groups caused a decrease in activity.26

Among the historical urea-based drugs, ritonavir (13) (Fig. 4) belongs to the class of protease inhibitors and it is an integral part of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for HIV. A decade ago, a novel urea derivative was approved as an anti-viral agent. Indeed, boceprevir (14), a protease inhibitor useful against hepatitis C virus (HCV), is capable of reversibly binding to the active site of non-structural protein 3 (NS3).27

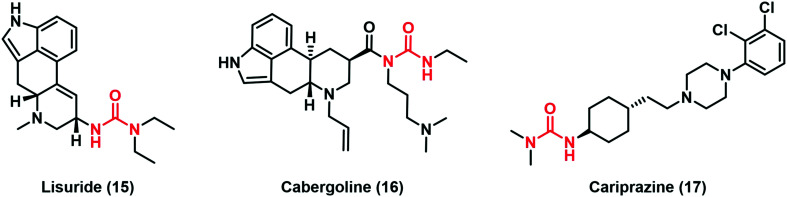

CNS active drugs

The thiourea moiety is commonly found in several compounds for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. The main therapeutic approach in Parkinson's disease (PD) is the use of dopamine agonists such as lisuride (15) and cabergoline (16), drugs that were approved at the end of the last century (Fig. 5).28 Acyl ureas create stable interactions between the tertiary nitrogen and peculiar amino acid residues of D2 dopamine receptors. In particular, it was speculated that Tyr387 is the targeted residue in the receptor helix 7, providing the site of retinal attachment in the homologous G protein coupled receptor rhodopsin and the distantly related protein bacteriorhodopsin.29

Fig. 5. Chemical structures of terminal urea-based drugs for CNS disorders.

In 2015, FDA approved cariprazine (17), a drug that belongs to the atypical antipsychotics, can be used in bipolar disorder treatment.30

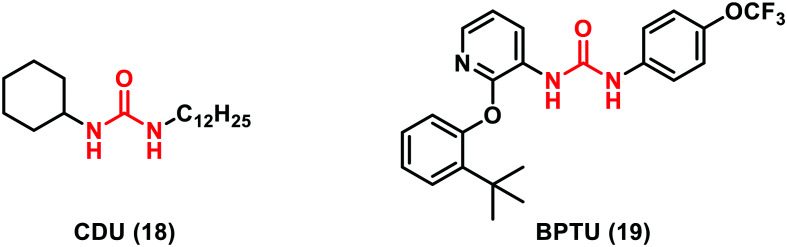

Miscellanea of other potential targets for urea-containing chemical tools

Another interesting target in which urea-containing derivatives may be a wealthy source of potent inhibitors is the epoxide hydrolase enzyme (sEHIs). The sEH enzyme plays a central role in the endogenous metabolism of bioactive molecules converting arachidonic acid (ARA) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) into the corresponding dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids. Accordingly, sEH inhibition is a promising therapeutic strategy for addressing a variety of diseases including hypertension, stroke, inflammatory disease and metabolic syndrome.31 sEH urea-based multitarget inhibitors, such as CDU (18, Fig. 6) (Ki = 7 nM), have been recently investigated since they mimic the transition state for epoxide ring opening. Crystallographic studies revealed that the carbonyl oxygen of the urea motif accepts H-bonds from two tyrosine residues (381 and 465) and the NH group donates a hydrogen bond to Asp333. The potency of sEHIs containing urea was significantly increased by introducing lipophilic groups, such as adamantyl, biphenyl or halogen groups able to build hydrophobic interactions with the L-shaped hydrophobic pocket of the sEH enzyme.32

Fig. 6. Chemical structures of other urea-based chemical tools.

Also, in the field of purinoreceptors, urea-containing compounds have been discovered to be particularly interesting. Indeed, a novel urea derivative called BPTU (19, Fig. 6) was reported by Bristol-Myers Squibb as an antithrombotic agent acting as a potent and selective antagonist of P2Y1 (Ki = 6 nM). X-ray crystallography of the BPTU–P2Y1 complex has highlighted the relationship between the urea scaffold and the receptor backbone. In particular, the single polar interaction is supplied by a bidentate H-bond between the NH groups of the urea moiety and a carbonyl residue of Leu 102 located on the outer surface of the receptor. BPTU (19) is the first structurally characterized selective G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) ligand, being able to bind to the allosteric pocket of the external receptor interface.33

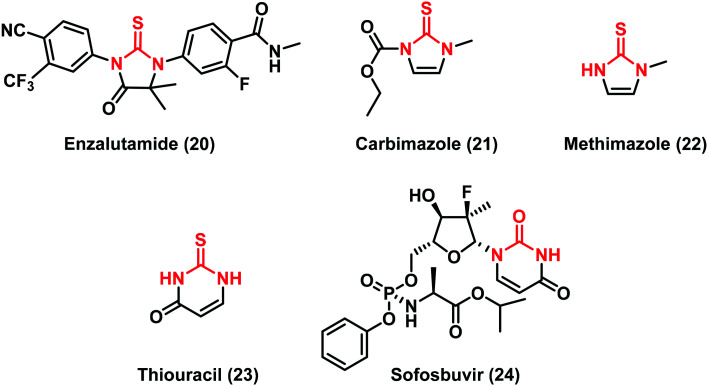

Cyclic (thio)urea-containing drugs

The (thio)urea moiety is often fixed in cyclic structures. The ring system can ensure restricted conformational flexibility, high selectivity and, generally, an increased oral bioavailability.34

Some anti-cancer agents containing a cyclic (thio)urea scaffold can act with different mechanisms of action such as i) inhibiting androgen receptor (AR) signalling: enzalutamide (20), approved in 2012 for the treatment of prostate cancer; or ii) interfering with the biosynthesis of thyroid hormones as in the case of carbimazole (21), a pro-drug converted into the active form methimazole (22), and thiouracil (23) including a high number of its synthetic derivatives (Fig. 7).35,36

Fig. 7. Chemical structures of cyclic (thio)urea-containing drugs.

Cyclic (thio)ureas have been classified as a new class of nonpeptidic inhibitors of proteases (PRs) because of the carbonyl oxygen mimicking the hydrogen-bonding features of the key structural water molecule inside the enzyme active site.37 A recent example is sofosbuvir (24) (Fig. 7), a novel and efficient urea-based agent, commercially available in combination with ledipasvir for the treatment of HCV.38

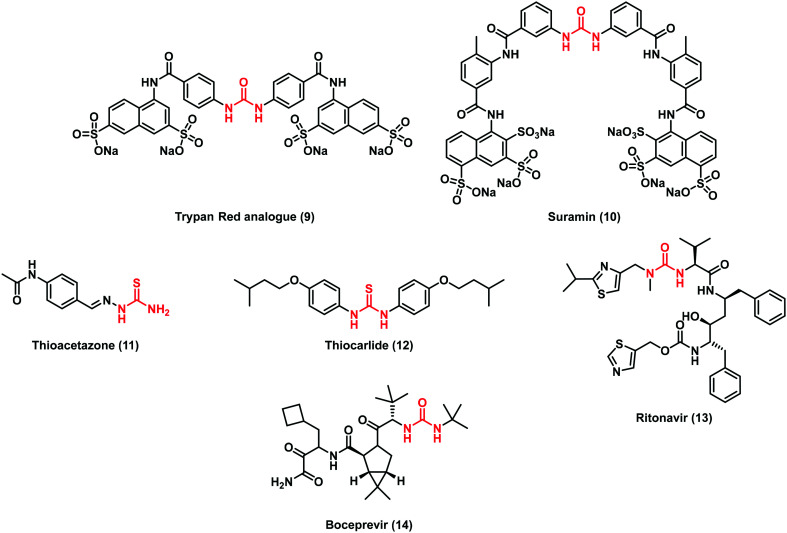

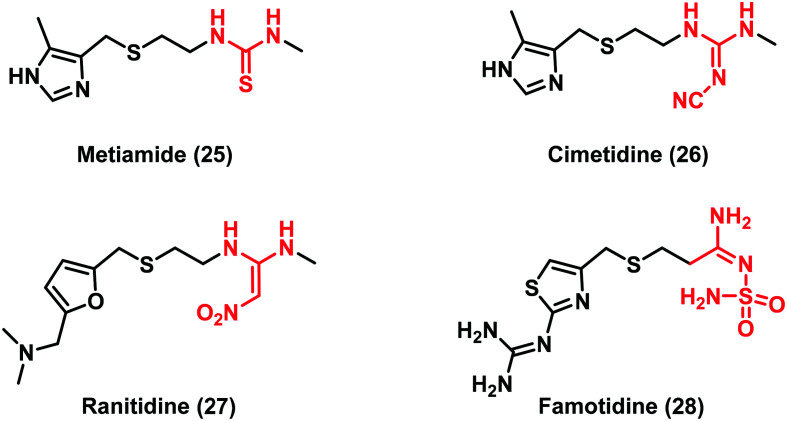

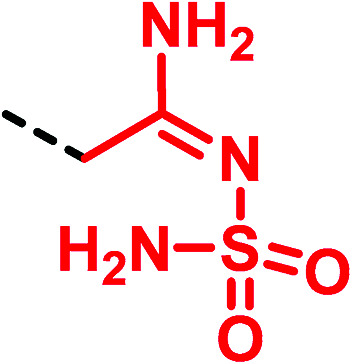

Bioisosteric replacement of the (thio)urea scaffold

Despite many drug candidates belonging to this class, some drawbacks, such as poor solubility, and metabolic and chemical instability resulting in a high attrition rate in clinical phases, have hampered their further development. Thus, the research of (thio)urea pharmacophoric alternatives has been sought as a winning strategy in the development of new lead compounds. In this context, a landmark work is the thiourea replacement by Ganellin and co-workers, which has paved the way for a considerable understanding of isostere design.39 The first thiourea-containing histamine H2-receptor antagonist compound metiamide (25) (Fig. 8) was found to be very effective for ulcer treatment by oral administration. However, side effects that have arisen during clinical trials led researchers to synthesize new derivatives by replacing the thiourea moiety. The introduction of a cyanoguanidine group afforded the well-known drug cimetidine (26), a potent H2-receptor antagonist with reduced toxicity. Further studies led to the discovery of new drugs by introducing the 2,2-diamino-1-nitroethene (ranitidine, 27) and N-aminosulfonylamidine (famotidine, 28) moieties (Fig. 8).40 These modifications improved the biological activity demonstrating how the cyanoguanidine, 2,2-diamino-1-nitroethene and N- aminosulfonylamidine moieties were valid bioisosteres of the thiourea scaffold.

Fig. 8. Thiourea bioisosteres as milestone drugs in antiulcer agent discovery.

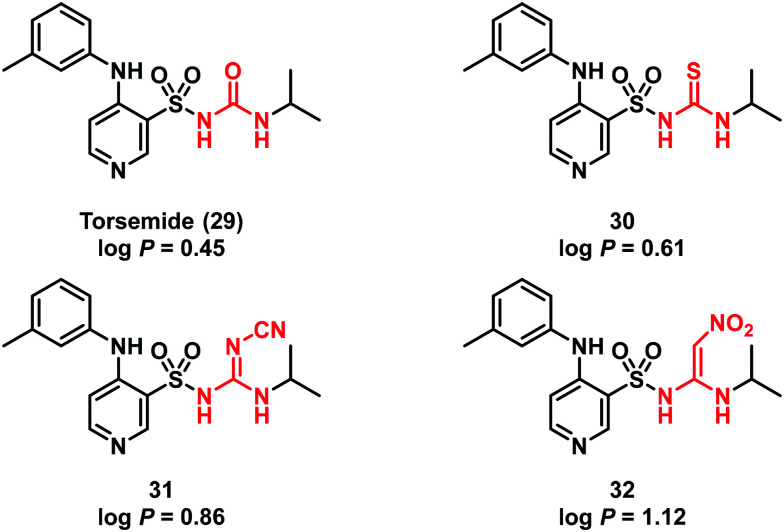

Successively, this strategy was adopted by other researchers in different contexts. During the development of the diuretic torsemide (29), Masereel and co-workers substituted the sulfonyl-urea functionality of the hit 29 with a sulfonylthiourea, cyanoguanidine and 2,2-diamino-1-nitroethene moiety (compounds 30–32, respectively) (Fig. 9).41 The new torsemide derivatives possessed a good lipophilicity profile making them suitable for diuretic and antiepileptic applications.

Fig. 9. Structure of torsemide (29) and its derivatives 30–32.

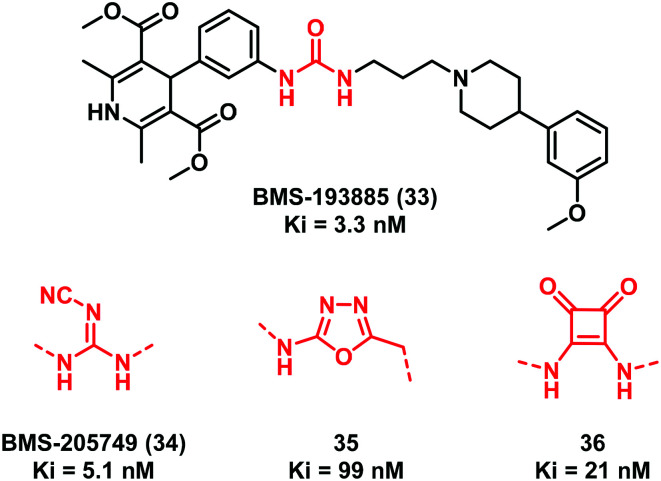

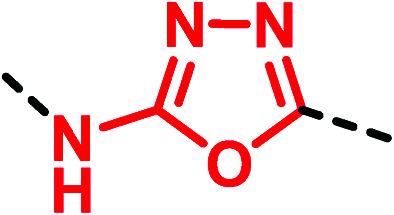

In 2004, Poindexter and collaborators42 focused their attention on the urea-containing compound BMS-193885 (33) (Fig. 10), which showed a potent and selective neuropeptide Y1 receptor antagonism (Ki = 3.3 nM) and a good brain permeability. However, the compound was endowed with a poor oral bioavailability (Fpo = 0.1%) probably because of the presence of the urea linker that prevented intestinal absorption. Thus, a new series of analogues of compound 33 was synthesized (Fig. 10) including cyanoguanidine BMS-205749 (34, Ki = 5.1 nM) and the oxadiazole 35 (Ki = 99 nM) (Fig. 10). Meanwhile, 34 resulted in an improved Caco-2 cell permeability. Compound 35 is the first example of a urea bioisostere characterized by the 2-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazole moiety.42

Fig. 10. Examples of urea bioisosteric replacement in the neuropeptide Y1 receptor antagonist BMS-193885 (33).

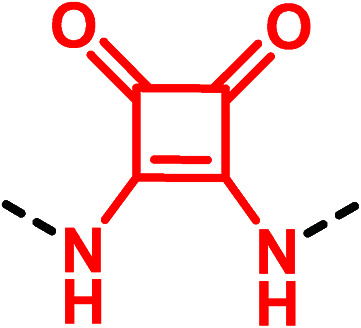

Interestingly, the same researchers also synthesized compound 36 (Ki = 21 nM) where the less common four-membered ring squaramide was used to replace the urea group.43

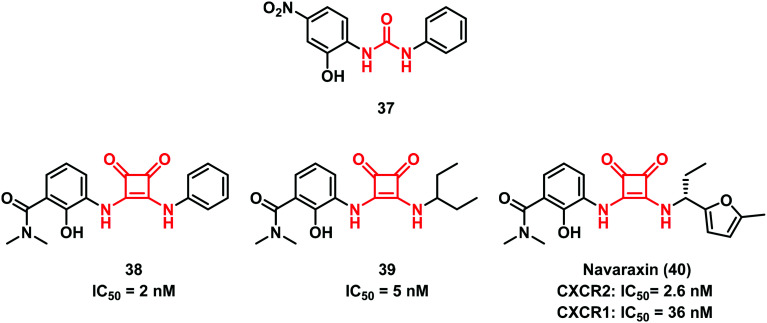

The ability of squaramides to form strong hydrogen bonds that increase the aromatic character and the simple way for their preparation prompted researchers to exploit this structure as a non-classical bioisosteric replacement for different functionalities including the urea scaffold.44 Other examples were successfully reported by Merritt et al.45 in the discovery of C–X–C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) GPCR antagonists, where the central spacer of some diaryl urea compounds (i.e., 37) was replaced by the squaramide moiety (Fig. 11). Some of the compounds synthesized showed good in vitro activity and 38 was found to be the most effective one. Dwyer and co-workers at Schering-Plough later focused their attention on this class of compounds. Starting from 39, an equipotent derivative of 38, they developed the drug candidate navarixin (40) (Fig. 11), an orally bioavailable dual CXCR1/CXCR2 receptor antagonist that entered phase II clinical studies in 2012.46

Fig. 11. Squaramide moiety as a urea bioisostere.

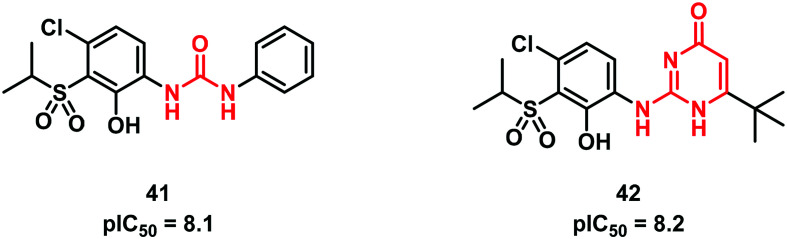

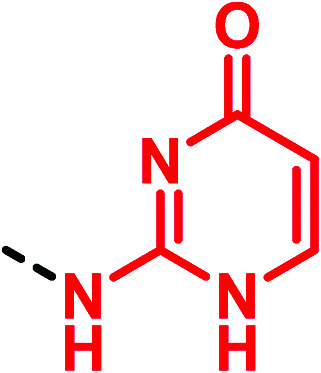

In the same field, Lu et al.47 at GSK introduced a 2-aminopyrimidin-4(1H)-one ring as an original urea bioisostere in the hit compound 41 (Fig. 12). The resulting compound 42 was found to be effective as a CXCR2 antagonist and to possess good permeability and better stability than the parent compound 41.

Fig. 12. Aminopyrimidin-4-one as a urea bioisosteric group.

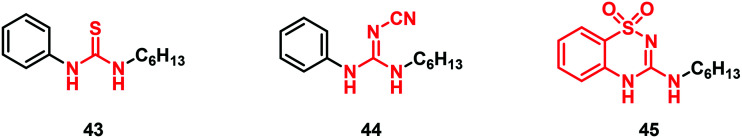

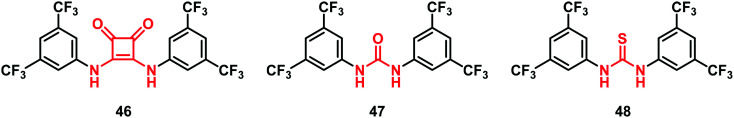

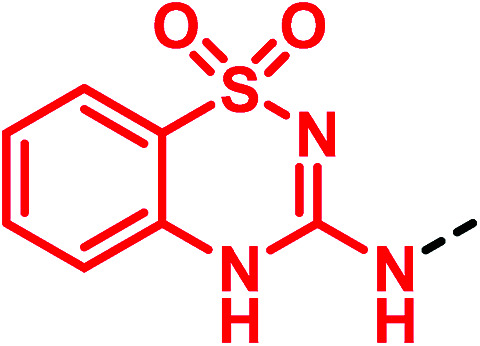

The concept of (thio)urea-based receptors comes from the studies carried out by Wilcox and collaborators in 1992.48 The authors observed that a urea derivative was able to interact with anions such as phosphonates, sulfates and carboxylates, forming stable 1 : 1 complexes held together by two parallel N–H⋯O hydrogen bonds. Since then, a variety of urea-based anion receptors have been synthesized, including different bioisosteres such as cyanoguanidine, squaramide and others. On this road, in 2011, Gale and co-workers developed anion receptors and transporters containing thiourea and cyanoguanidine moieties with compounds 43 and 44 as the initial prototypes. They also discovered compound 45 bearing an unusual 3-amino-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine-1,1-dioxide scaffold as a phenylurea bioisostere (Fig. 13). Testing their chloride transport properties in comparison with the parent thiourea derivative 43, these potential “urea-based anion receptors” showed high capacity for binding and transporting anions.49

Fig. 13. 3-Amino-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine-1,1-dioxide scaffold as a (thio)urea bioisostere.

It is worthy to note that squaramides were subsequently chosen as a leitmotiv for the development of novel anion transport modulators. Thus, Busschaert et al.50 synthesized the squaramide derivative 46 with a low EC50 (0.01 mol%, expressed as carrier to lipid) in comparison with the corresponding urea-analogue 47 (0.30 mol%) and thio-analogue 48 (0.16 mol%) proving to be a good anion transport modulator (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Examples of squaramide derivatives.

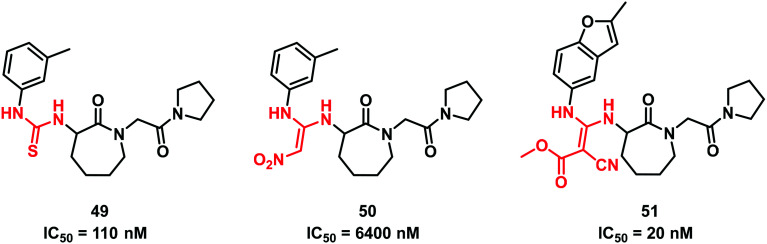

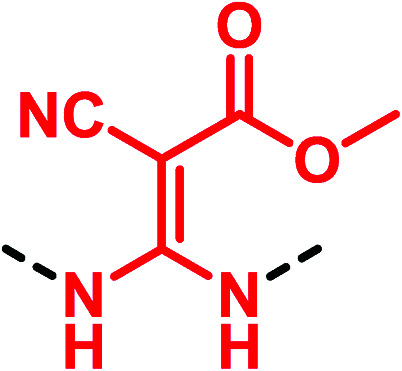

In 2005, Shi et al.51 studying the factor Xa inhibition reported the substitution of the thiourea scaffold of the starting lactam hit 49 with the classical 2,2-diamino-1-nitroethene. However, this replacement produced a weaker compound (IC50 = 6400 nM for 50vs. 110 nM of 49). Further modifications afforded 51 bearing a methyl-3,3-diamino-2-cyanoacrylate group, endowed with improved inhibition activity (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Structures of 2,2-diamino-1-nitroethene derivatives as factor Xa inhibitors.

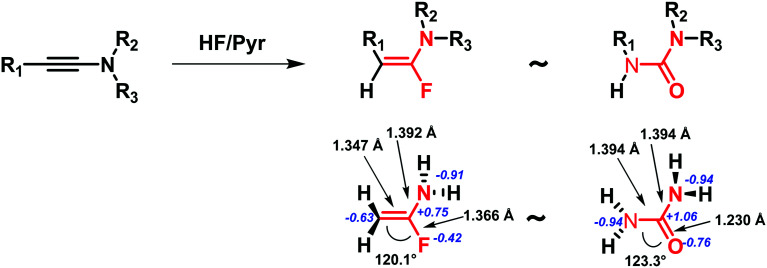

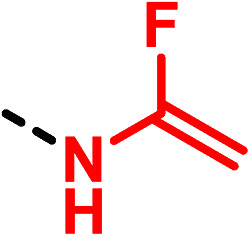

In 2015, Métayer and co-workers proposed a new uncommon α-fluoroenamine motif expanding the knowledge of (thio)urea bioisosteres. The project was focused on the investigation of the N-sulfonyl-substituted ureas' chemical space, synthesizing a set of α-fluoroenamides. After the evaluation of their chemical stability, theoretical ab initio calculations were carried out showing similar geometric and electronic properties between urea and α-fluoroenamide moieties (Fig. 16).52

Fig. 16. Urea and α-fluoroenamide groups display similar geometric and electronic properties. As an example, the unsubstituted compounds are reported together with the relevant measured angles, distance lengths (black arrows and labels) and partial charges (blue label) obtained by ab initio calculations.

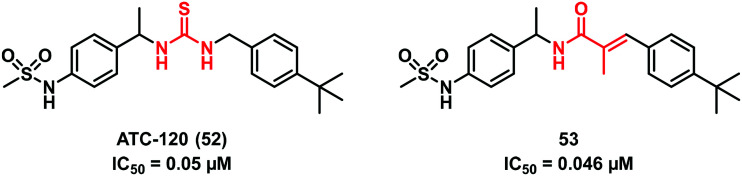

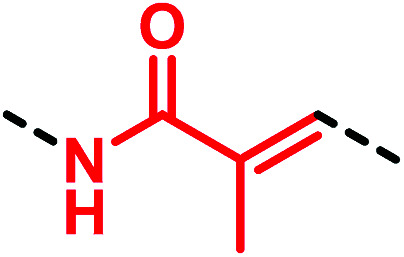

A recent study by Park et al.53 on the non-selective cation channel TRPV1 showed a new interesting chemotype of (thio)urea bioisostere. Indeed, replacing the thiourea functionality of ATC-120 (52) with a 2-methylacrylamide moiety as in 53 resulted in a molecule equally potent to the starting compound 52 (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. 2-Methylacrylamide moiety as a thiourea bioisostere.

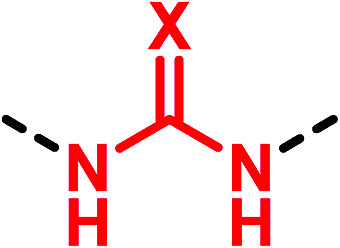

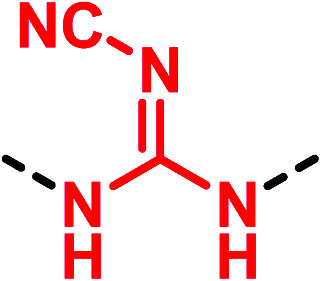

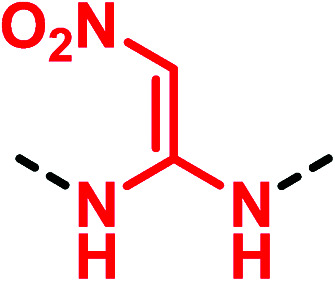

All replacements above described are summarized in the following table (Table 1).

(Thio)urea bioisosteres.

| Motif | Bioisotere | Replacement effecta |

|---|---|---|

X = O, S X = O, S |

|

▶ Fixing agranulocytosis side effect [metiamide (25) → cimetidine (26)]39 |

| ▶ Improvement in lipophilicity [log P = 0.45 (torsemide, 29) vs. 0.86 (31)]41 | ||

| ▶ Increase of acidityb [pKa = 6.68 (29) vs. 6.00 (31)]41 | ||

| ▶ Similar binding potency at the Y1 receptor [Ki = 3.3 nM (BMS-193885, 33) vs. 5.1 nM (BMS-205749, 34)]42 | ||

| ▶ Improvement in permeability in Caco-2 cells [Pc = 19 nm s−1 (33) vs. 43 nm s−1 (34)]42 | ||

| ▶ Fixing potentially toxic effects of thioureas (43 → 44)49 | ||

|

▶ Similar properties and behaviour of the corresponding thiourea motif [metiamide (25) → ranitidine (27)]40 | |

| ▶ Large improvement in lipophilicityb [log P = 0.45 (torsemide, 29) vs. 1.12 (32)]41 | ||

| ▶ Fixing potentially toxic effects of thioureas (49 → 50)51 | ||

|

▶ Similar properties and behaviour of the corresponding thiourea compoundc [metiamide (25) → famotidine (28)]40 | |

|

▶ Moderate binding affinity at the Y1 receptor (20-fold loss of potency) [BMS-193885 (33) → 35]42 | |

|

▶ Good binding affinity at the Y1 receptor (4-fold loss of potency) [BMS-193885 (33) → 36)43 | |

| ▶ Increase of the number of H-bonds | ||

| ▶ H-Bond acceptor capability driven by an increase in aromaticity on binding structural rigidity (37 → 38, 39, navaraxin (40); 47 → 46)45,46,50 | ||

|

▶ Increased chemical stability in SGF (simulated gastric fluid) | |

| ▶ Improvement of solubility and passive permeability (41 → 42)47 | ||

|

▶ Similar properties and behaviour of the corresponding thiourea motif (43 → 45)49 | |

|

▶ Not clarified by the authors (49 → 51)51 | |

|

▶ Similar geometry and physico-chemical properties | |

| ▶ Improvement of chemical stability52 | ||

|

▶ Improve drug-like properties without loss of potency [ATC-120 (52) → 53]53 |

Examples are reported between brackets.

pKa of the sulfonamido group.

The increased potency is mainly related to the replacement of the imidazole ring.

Innovative methods for the preparation of urea and thiourea derivatives

As a complement to prior reviews1,2,54 dealing with the current ‘conventional’ methods enabling the synthetic accessibility of (thio)urea compounds, in this section, we report recent developments of novel approaches based on the employment of the so-called “enabling chemical technologies”. Despite the advances made, classical synthesis is still plagued with several drawbacks including high reaction times, moderate yields, limited substrate scope, and the use of toxic, unstable, explosive (phosgene, inorganic azides) and bio-hazardous metallic reagents.55

To leverage the power of synthesis toward ureas and thioureas, a number of enabling approaches have been developed that can facilitate the execution of chemical transformations and expedite compound synthesis. Among them, continuous flow chemistry, microwave irradiation, ultrasound, and photo- and electro-chemistry have not only increased synthesis efficiency but also improved safety and lowered environmental impact.

Continuous flow chemistry

Continuous flow chemistry represents an appealing area of research inspiring the development of green and modern methods,56,57 gaining attention from academia and pharmaceutical companies. The advantages of flow chemistry include the high control of the reaction variables, which translates into higher product quality; increased safety; possibility of conducting reactions under superheated conditions; feasibility of automation reducing manual handling; reproducibility and easy scale-up; possibility of in-line work-up/purification operations and reaction telescoping; process intensification resulting in a smaller footprint in a manufacturing plant.58

Continuous flow chemistry has been exploited in the rapid preparation of compound collections, in the optimization and scale-up of relevant products and, more recently, in the development and manufacturing processes of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).59–61

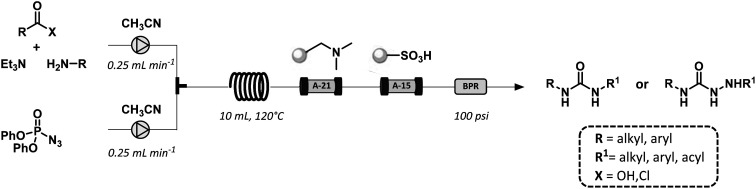

The Curtius rearrangement is a common synthetic strategy toward urea scaffolds.62 As this transformation relies on high-energy acyl azide intermediates that release nitrogen gas upon heating, the enhanced process control ensured by flow reactors is crucial for the safe execution of such reactions.63,64

The first flow synthesis of ureas was reported by the Ley group. The method consisted in the Curtius rearrangement of hazardous azides or acyl azides with in situ trapping of the resulting isocyanate intermediate leading to the corresponding urea derivatives in 75–93% yield (Fig. 18).65,66 The use of polymer-supported scavengers facilitated the in-line purification of the desired products using a combination of the readily available low-cost scavenger resins A-15 and A-21.

Fig. 18. General scheme for the Curtius rearrangement of carboxylic acids and acyl chlorides under continuous flow conditions.

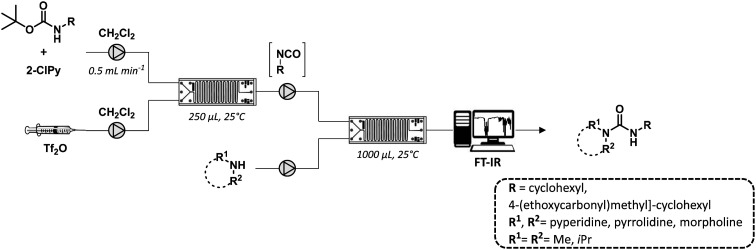

In a recent work, Bana and co-workers developed a two-step flow synthesis of nonsymmetric ureas from Boc-protected amines under mild conditions and a short reaction time (Fig. 19).67 The flow set-up was based on the integration of two sequential microreactors and was applied to the preparation of a series of urea derivatives variably functionalized. The advantages of the flow approach was further demonstrated for the scale-up of the active pharmaceutical ingredient cariprazine (17) with a yield of 83% and a productivity of 320 mg h−1.

Fig. 19. General schematic flow set-up composed of two sequential microreactors and an in-line FT-IR spectrometer.

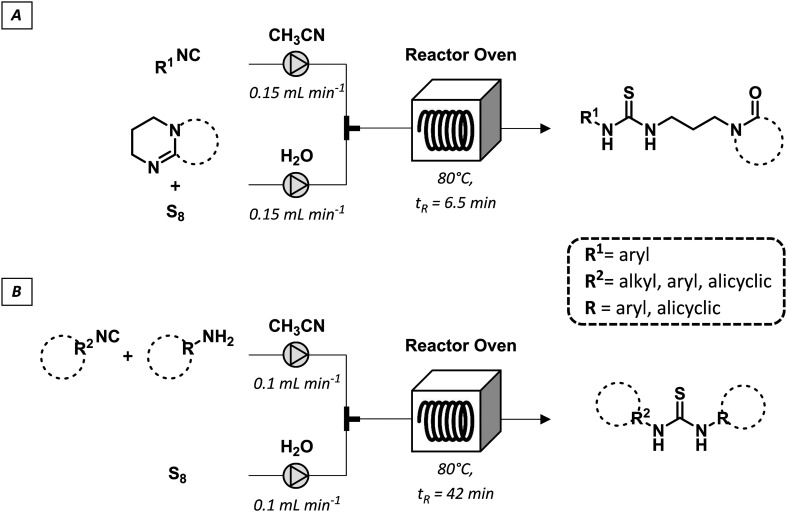

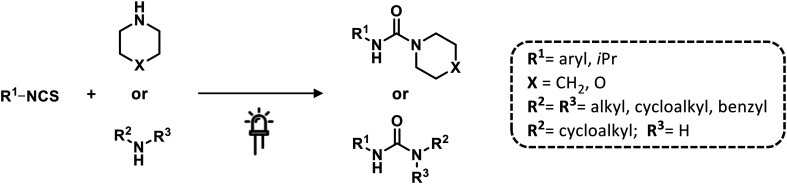

A series of variably functionalized thioureas was synthesized by a multicomponent flow approach by reaction of isocyanides with amidines or amines in the presence of an aqueous polysulfide solution.68 The latter was prepared from elemental sulfur and was efficiently used to incorporate sulfur atoms in diversified substrates under homogeneous conditions (Fig. 20). Importantly, the products were isolated by simple filtration without the need for further purification confirming the potential of the convenient flow adoption for sulfur chemistry.

Fig. 20. Multicomponent continuous-flow synthesis of thioureas from isocyanides (A), amidines or amines and sulfur (B).

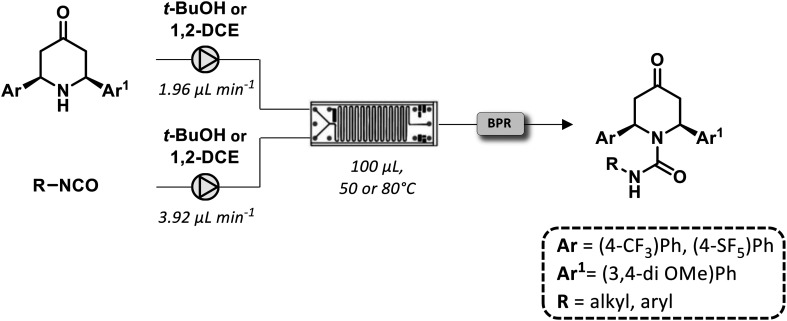

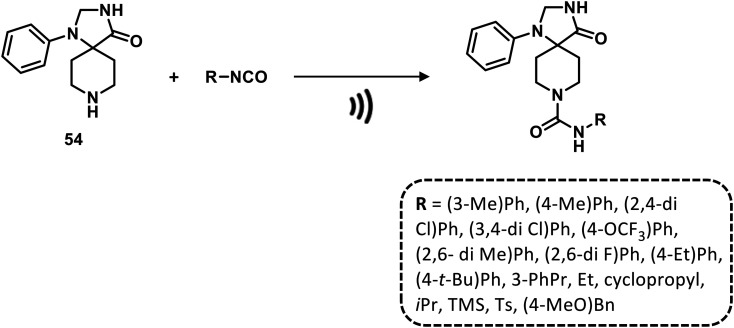

Recently, the synthesis of a novel library of piperidin-4-one derivatives containing a urea moiety was realized under flow conditions.69 The reaction between enantiopure amino ketones and isocyanates provided a set of spirocyclic compounds in moderate to high yields (Fig. 21). The reactions utilized for their syntheses were achieved with a residence time of 17 min without a further need for purification.

Fig. 21. Continuous-flow generation of a piperidin-4 one library based on a urea scaffold.

Microwave and ultrasound-assisted synthesis

In organic and pharmaceutical chemistry, Microwave (MW) and ultrasound (US) irradiations are recognized, as non-conventional energy sources, useful in enhancing the reaction rates and generating cleaner and high-yielding chemical transformations.70,71 As alternative activation factors, microwaves (MWs) or ultrasound (US) and also their combination have been proved for the rapid and efficient generation of bioactive products in applied medicinal chemistry.72

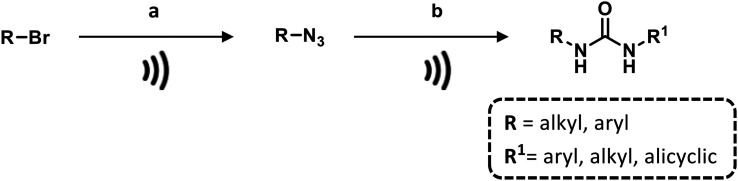

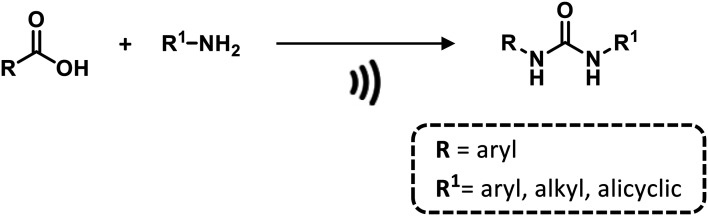

An alternative and safer generation of isocyanide was proposed by Cravotto and collaborators by optimization of the MW-assisted Staudinger–aza-Wittig reaction using supported polymer bound diphenylphosphine (PS-PPh2) in a carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere (Scheme 1). The replacement of traditional phosgene with the nontoxic, abundant and economical CO2 provides a new green synthetic procedure for a rapid and easy access to urea libraries using a sustainable source.73

Scheme 1. Generation of a urea library by using MW-assisted Staudinger–aza-Wittig reaction. Reaction conditions: a) NaN3, CH3CN, 95 °C, 240 W; b) PS-PPh2, CO2, primary amine, 70 °C, 200 W.

In 2017, Thakur and co-workers reported a simple protocol for the preparation of unsymmetrical ureas starting from (hetero)aromatic carboxylic acids and amines via Curtius rearrangement by using diphenylphosphorylazide (DPPA). This one-pot tandem, microwave-accelerated synthesis provided the construction of a large panel of variably functionalized urea derivatives in a short time (1–5 minutes) and in excellent yields (Scheme 2). The procedure was applied to the gram-scale synthesis of cannabinoid CB1 and α7 nicotinic receptor ligands.55

Scheme 2. One-pot tandem, microwave-accelerated synthesis of diaryl ureas. Reaction conditions: DPPA, Et3N, 100 °C, toluene.

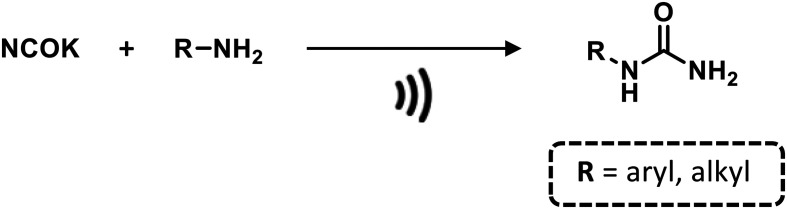

In the (thio)urea context, the classical batch reaction limitations between potassium cyanate and amines, such as long reaction times and moderate yields, were overcome by performing the reaction under microwave conditions in the presence of an aqueous solution of HCl, obtaining N-monosubstituted ureas (Scheme 3).74

Scheme 3. Synthesis of N-substituted ureas via reaction between potassium cyanate and different amines under microwave irradiation. Reaction conditions: H2O, 80 °C, 1000 W.

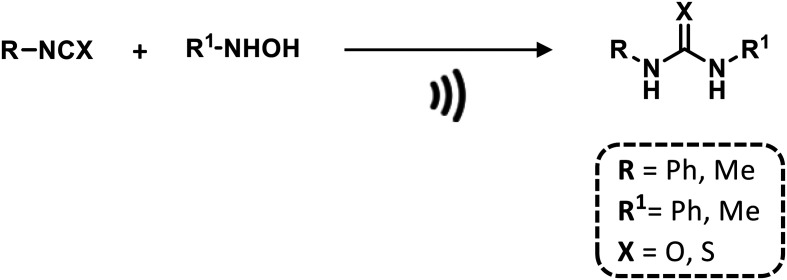

In addition, the use of green reaction media or solventless reactions has been increasingly exploited for the synthesis of relevant scaffolds including (thio)ureas. As an example, a variety of symmetrical and unsymmetrical disubstituted thioureas and ureas were rapidly prepared by reacting N-monosubstituted hydroxylamines with isocyanate and isothiocyanate derivatives over MgO as a basic solid support in a solventless system under MW (Scheme 4).75

Scheme 4. Microwave-assisted synthesis of (thio)ureas in a solventless system. Reaction conditions: MgO, 200 W.

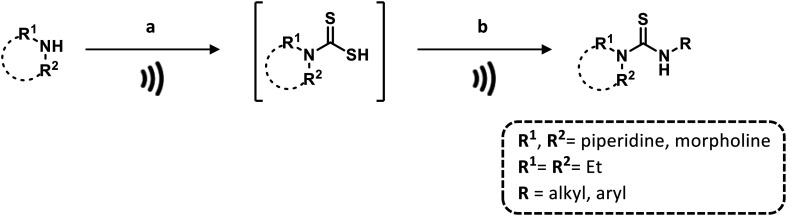

Furthermore, Chau et al.76 proposed a base- and solvent-free microwave-assisted procedure for the one-pot synthesis of di- and trisubstituted thioureas in a few minutes and in good yields (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. One-pot synthesis of substituted-thioureas under microwave conditions. Reaction conditions: a) CS2, 160 °C, 150 W; b) primary amine, 160 °C, 150 W.

A diversified library of 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one urea derivatives was constructed from 1-phenyl-1,3,8- triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one and aromatic or aliphatic isocyanates at room temperature under ultrasound conditions, ensuring significant advantages in terms of efficiency, selectivity and sustainability (Scheme 6).77

Scheme 6. Ultrasound-mediated synthesis of ureas. Reaction conditions: CH2Cl2, r.t.

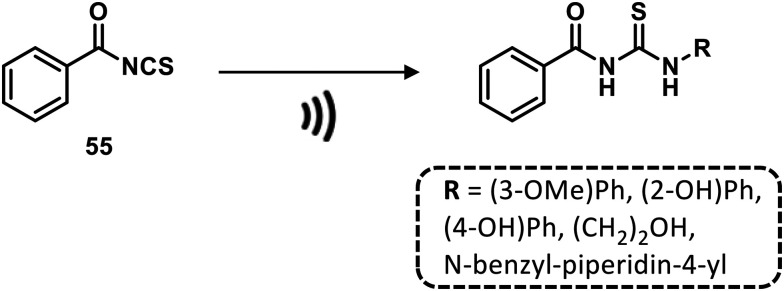

In a recent work, Odame and collaborators reported an ultrasound-promoted formation of benzoyl isothiocyanate as a starting material for the generation of a series of substituted thioureas in excellent yields and in a relatively short time (about 1 h) at room temperature (Scheme 7).78

Scheme 7. Synthesis of thioureas under ultrasounds. Reaction Conditions: primary amine, acetone, r.t.

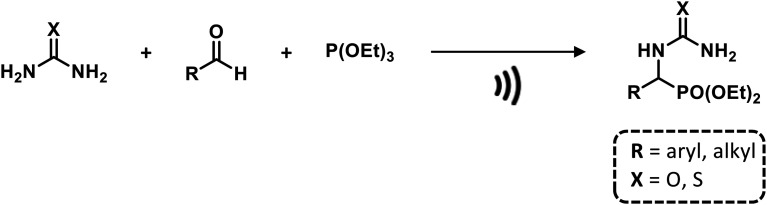

Notably, α-ureidophosphonates were obtained by reacting aldehydes, urea/thioureas, and triethyl phosphite or diethyl phosphite using ultrasonic irradiation under solvent- and catalyst-free conditions at different ranges of temperature in high yields and short reaction times (15–30 min). In this case, USI facilitates the nucleophilic attack of the amino functional group (urea/thiourea) on the carbonyl group (aldehyde) promoting forbidden reactions in traditional batch methods (Scheme 8).79

Scheme 8. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of α-ureidophosphonates. Reaction conditions: 75 °C, 40 kHz.

Electrochemistry and photochemistry

Photochemical and electrochemical processes are currently an important research field and the recent advances on these methodologies have made clear their advantages and importance in modern chemistry and technology.80–82 In light of unconventional or innovative techniques, electrochemistry and photochemistry provide an alternative way to synthesize organic molecules. The use of electrons or photons as mass-free reagents results in environment friendliness, with a low production of waste and generation organic molecules and intermediates that cannot be generally achieved with conventional chemistry.83

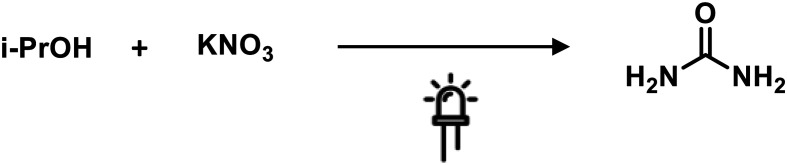

Srinivas and collaborators proposed the synthesis of urea from in situ generated ammonia and carbon dioxide, using TiO2 and Fe-titanate supported over zeolite photocatalysts. The reaction was performed in aqueous media containing nitrate ions and 2-propanol, generating ammonia and CO2, respectively. The ammonium carbamate obtained underwent a dehydration process affording urea as the desired product. The reaction was carried out at room temperature using UV as the light source (Scheme 9).84

Scheme 9. Photocatalytic synthesis of urea. Reaction conditions: TiO2-zeolite, Hg lamp 250 W, 1 atm, 40 °C.

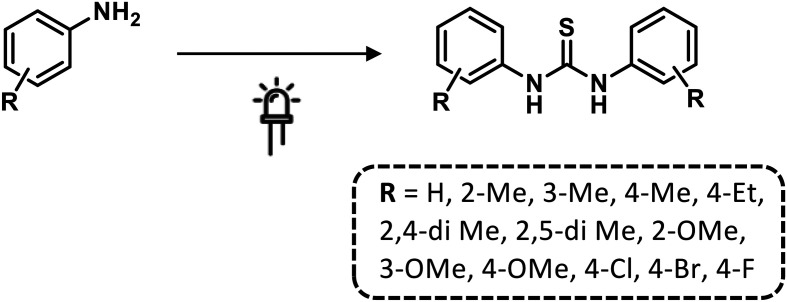

Kumavat et al.85 developed a catalyst-free method for synthesizing symmetric thiourea derivatives. The reaction was carried out in water, without stirring, and using CS2 and aromatic primary amines under sunlight. With this simple procedure, they afforded a series of thiourea derivatives in good yields (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10. Synthesis of symmetrical N,N′-diaryl thioureas under sunlight. Reaction conditions: CS2, H2O.

Recently, Yang and co-workers developed a green and one-pot oxidative desulfurization protocol for the synthesis of unsymmetrical ureas starting from different aryl isothiocyanates and aliphatic amines under visible light conditions.86 The reaction was carried out in DMSO, using eosin Y as a photo-redox catalyst, a 12 W blue LED as the irradiation source and oxygen affording unsymmetrical urea derivatives in high yields (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11. Oxidative desulfurization of thiocarbonyl compounds for the synthesis of urea derivatives. Reaction conditions: O2, eosin Y, DMSO/H2O, 12 W blue LED.

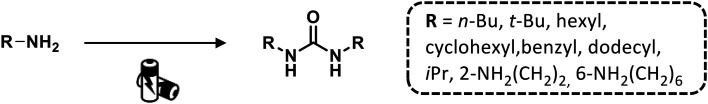

Electrochemistry was also employed in the synthesis of ureas. Deng and co-workers synthesized several symmetrical dialkyl ureas using Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 as a catalyst and Cu(Oac)2 as a cocatalyst, avoiding a high pressure of carbon monoxide (CO) and O2.87 Under mild reaction conditions (T = 30 °C and P = 1 atm), the authors claimed very efficient electrochemical and homogeneous electrocatalytic activities. However, the formation of isocyanate as a side product was observed (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12. Synthesis of symmetrical dialkyl ureas by electrocatalytic carbonylation of aliphatic amines. Reaction conditions: CO, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, Cu(OAc)2, n-BuNCl4, CH3CN or DMF, 30 °C, 1 atm, 0.9 V.

Feroci and Chiarotto developed a new methodology to synthesize symmetrical urea derivatives starting from aromatic and aliphatic primary amines and CO under mild conditions (Scheme 13).88 The absence of any cocatalyst was allowed thanks to the recycling of the palladium(ii) catalyst at a graphite electrode. The ureas were generated with high reaction yields from aliphatic amines and low formation of collateral products.

Scheme 13. Oxidative carbonylation of aliphatic and aromatic amines for the synthesis of symmetrical ureas. Reaction conditions: CO, Pd(OAc)2 or Pd(PPh3)4, n-Bu4NBF4, CH3CN, NaOAc, 50 °C, 1 atm, 0.4 V.

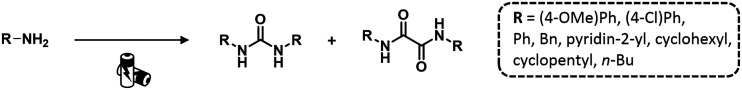

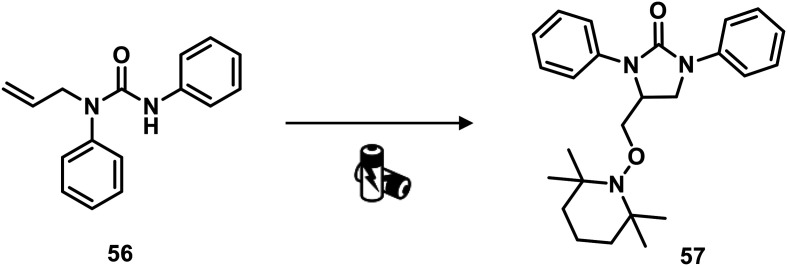

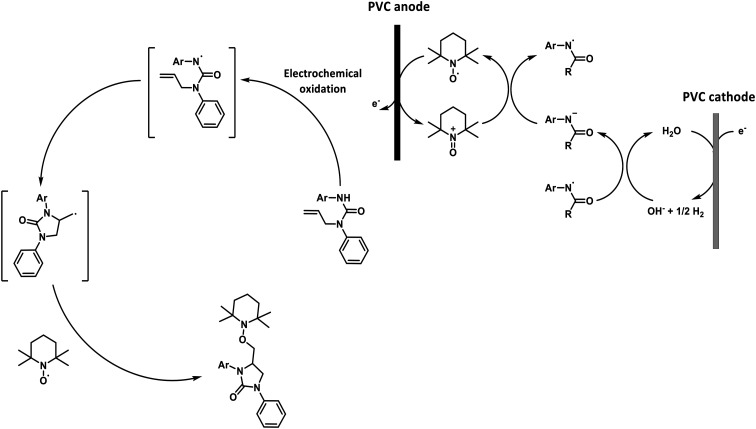

Recently, Nisar and Saira reported a green catalyst- and oxidant-free approach for difunctionalization of urea-tethered alkenes. By using controlled intramolecular amination, they obtained cyclic compounds, in high yields, starting from several urea nucleophiles. Indeed, electricity has driven the reaction involving the generation of a nitrogen radical on the urea moiety that, after the addition of an unactivated/unsubstituted terminal alkene, led to the formation of a new terminal carbon radical. The latter was trapped with TEMPO which played a dual role of redox facilitator and radical trapper (Scheme 14 and Fig. 22).89

Scheme 14. Synthesis of cyclic urea derivatives by difunctionalization of alkenes. Reaction conditions: TEMPO, H2O, CH3CN, 60 °C, RVC anode, Pt cathode 10 mA.

Fig. 22. A proposed mechanism for the electrosynthesis of phenylimidazolidinones.

Conclusions

Urea, thiourea and their derivatives are substructures in numerous pharmaceutical compounds with a broad scope of therapeutic applications. Given this great importance, a variety compounds have been already approved for the treatment of different human diseases and, thus, many promising drug candidates are currently in development. Herein, we initially highlighted a plethora of pharmacological and clinical applications emphasizing the role of these scaffolds in candidates or approved drugs with clinical potential. We also outlined the recent approaches and uses of (thio)urea bioisosteres. Finally, in the last section, we showcased recent innovative methodologies and synthetic strategies aimed at the efficient preparation of (thio)urea products. Indeed, these unconventional synthetic methodologies meets the need of modern pharmaceutical chemistry of exploiting more sustainable, green and safe protocols. The proposed strategies based on “enabling technologies” allow the extension of the chemical space for drug discovery, ensuring a rapid access to diversified (thio)urea libraries with good/excellent yield. Although photochemistry and electrochemistry represent alternative and attractive techniques in the synthesis of promising (thio)urea drug targets, these approaches are still challenging and require further investigations. In conclusion, the use of these powerful tools mentioned above has the real aim of simplifying the chemical accessibility of this class of versatile compounds.

According to all mentioned information in this text, we hope that the present review will further stimulate researchers active in the field to exploit urea and thiourea compounds as important structural motifs instrumental in modern drug design, synthesis, and medicinal chemistry.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Perugia for financial support (Ricerca di base 2018).

References

- Ghosh A. K. Brindisi M. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:2751–2788. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garuti L. Roberti M. Bottegoni G. Ferraro M. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016;23:1528–1548. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160411142532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui N. Alam M. S. Stables J. P. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:2236–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimshoni J. A. Bialer M. Wlodarczyk B. Finnell R. H. Yagen B. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6419–6427. doi: 10.1021/jm7009233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keche A. P. Hatnapure G. D. Tale R. H. Rodge A. H. Birajdar S. S. Kamble V. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:3445–3448. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashem H. E. Amr A. E. E. Nossier E. S. Elsayed E. A. Azmy E. M. Molecules. 2020;25:2766. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas S. Y. Al-Harbi R. A. K. El-Sharief M. A. M. Sh. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;198:112363. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V. Chimni S. S. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015;15:163–175. doi: 10.2174/1871520614666140407123526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramberg P. J. Ambix. 2000;47:170–195. doi: 10.1179/amb.2000.47.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Schreiner P. R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1187–1198. doi: 10.1039/b801793j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap A. D. Kondekar N. B. Sadani A. A. Chern J. W. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017;24:622–651. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666161129124915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra R. K. Das P. K. Pradhan M. K. El-Ajaily M. M. Das D. Salem H. F. Mahanta U. Badhei G. Parhi P. K. Maihub A. A. Kudrat-E-Zahan M. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2019;39:127–187. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki M. Hoshi T. Yamamoto Y. Ikemori-Kawada M. Minoshima Y. Funahashi Y. Matsui J. Cancer Med. 2018;7:2641–2653. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian M. A. 3rd Biggs W. H. Treiber D. K. Atteridge C. E. Azimioara M. D. Benedetti M. G. Carter T. A. Ciceri P. Edeen P. T. Floyd M. Ford J. M. Galvin M. Gerlach J. L. Grotzfeld R. M. Herrgard S. Insko D. E. Insko M. A. Lai A. G. Lélias J. M. Mehta S. A. Milanov Z. V. Velasco A. M. Wodicka L. M. Patel H. K. Zarrinkar P. P. Lockhart D. J. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. C. Hsu C. Cheng A. L. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;45:794–807. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano A. Iacopetta D. Sinicropi M. S. Franchini C. Appl. Sci. 2021;11:374. [Google Scholar]

- Gandin V. Ferrarese A. Dalla Via M. Marzano C. Chilin A. Marzaro G. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16750. doi: 10.1038/srep16750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas M. E. Habra M. A. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016;42:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K. Ikemori-Kawada M. Jestel A. von König K. Funahashi Y. Matsushima T. Tsuruoka A. Inoue A. Matsui J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;6:89–94. doi: 10.1021/ml500394m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondevila F. Méndez-Blanco C. Fernández-Palanca P. González-Gallego J. Mauriz J. L. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0308-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. H. Goss G. D. Salgia R. Besse B. Gandara D. R. Hanna N. H. Yang J. C. Thertulien R. Wertheim M. Mazieres J. Hensing T. Lee C. Gupta N. Pradhan R. Qian J. Qin Q. Scappaticci F. A. Ricker J. L. Carlson D. M. Soo R. A. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:1418–1425. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318220c93e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. Hartandi K. Ji Z. Ahmed A. A. Albert D. H. Bauch J. L. Bouska J. J. Bousquet P. F. Cunha G. A. Glaser K. B. Harris C. M. Hickman D. Guo J. Li J. Marcotte P. A. Marsh K. C. Moskey M. D. Martin R. L. Olson A. M. Osterling D. J. Pease L. J. Soni N. B. Stewart K. D. Stoll V. S. Tapang P. Reuter D. R. Davidsen S. K. Michaelides M. R. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1584–1597. doi: 10.1021/jm061280h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelo D. J. Stone R. M. Heaney M. L. Nimer S. D. Paquette R. L. Klisovic R. B. Caligiuri M. A. Cooper M. R. Lecerf J. M. Karol M. D. Sheng S. Holford N. Curtin P. T. Druker B. J. Heinrich M. C. Blood. 2006;108:3674–3681. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonvicino D. Mazzola F. Zamporlini F. Resta F. Ranieri G. Camaioni E. Muzzi M. Zecchi R. Pieraccini G. Dölle C. Calamante M. Bartolucci G. Ziegler M. Stecca B. Raffaelli N. Chiarugi A. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018;25:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemar N. Hauser D. A. Mäser P. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01168–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01168-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R. North E. J. Hurdle J. G. Morisseau C. Scarborough J. S. Sun D. Korduláková J. Scherman M. S. Jones V. Grzegorzewicz A. Crew R. M. Jackson M. McNeil M. R. Lee R. E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:5585–5595. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njoroge F. G. Chen K. X. Shih N. Y. Piwinski J. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:50–59. doi: 10.1021/ar700109k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz C. M. and Fernández A. M., in Urea: synthesis, properties and uses, Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2012, pp. 183–200 [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox R. E. Tseng T. Brusniak M. Y. Ginsburg B. Pearlman R. S. Teeter M. DuRand C. Starr S. Neve K. A. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4385–4399. doi: 10.1021/jm9800292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agai-Csongor E. Domány G. Nógrádi K. Galambos J. Vágó I. Keserű G. M. Greiner I. Laszlovszky I. Gere A. Schmidt E. Kiss B. Vastag M. Tihanyi K. Sághy K. Laszy J. Gyertyán I. Zájer-Balázs M. Gémesi L. Kapás M. Szombathelyi Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:3437–3440. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandan S. K. Do Z. N. Webb H. K. Patel D. V. Gless R. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:1066–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Mahapatra A. Choubey R. Datta B. Molecules. 2020;25:5488. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Gao Z. G. Zhang K. Kiselev E. Crane S. Wang J. Paoletta S. Yi C. Ma L. Zhang W. Han G. W. Liu H. Cherezov V. Katritch V. Jiang H. Stevens R. C. Jacobson K. A. Zhao Q. Wu B. Nature. 2015;520:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frecer V. Burello E. Miertus S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:5492–5501. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalken J. Fitzpatrick J. M. BJU Int. 2016;117:215–225. doi: 10.1111/bju.13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Jee J. G. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:28534–28548. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge C. N. Aldrich P. E. Bacheler L. T. Chang C. H. Eyermann C. J. Garber S. Grubb M. Jackson D. A. Jadhav P. K. Korant B. Lam P. Y. Maurin M. B. Meek J. L. Otto M. J. Rayner M. M. Reid C. Sharpe T. R. Shum L. Winslow D. L. Erickson-Viitanen S. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:301–314. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourlière M. Adhoute X. Ansaldi C. Oules V. Benali S. Portal I. Castellani P. Halfon P. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;9:1483–1494. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1111757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant G. J. Emmett J. C. Ganellin C. R. Miles P. D. Parsons M. E. Prain H. D. White G. R. J. Med. Chem. 1977;20:901–906. doi: 10.1021/jm00217a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganellin C. R., in The role of organic chemistry in drug research, ed. C. R. Ganellin and S. M. Roberts, Academic Press, London, 1993, pp. 227–255 [Google Scholar]

- Wouters J. Michaux C. Durant F. Dogné J. M. Delarge J. Masereel B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000;35:923–929. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)01174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poindexter G. S. Bruce M. A. Breitenbucher J. G. Higgins M. A. Sit S. Y. Romine J. L. Martin S. W. Ward S. A. McGovern R. T. Clarke W. Russell J. Antal-Zimanyi I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:507–521. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G. Mattson G. K. Bruce M. A. Wong H. Murphy B. J. Longhi D. Antal-Zimanyi I. Poindexter G. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:5975–5978. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew-Francis K. A. Williams C. M. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:11616–11650. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt J. R. Rokosz L. L. Jr Nelson K. H. Kaiser B. Wang W. Stauffer T. M. Ozgur L. E. Schilling A. Li G. Baldwin J. J. Taveras A. G. Dwyer M. P. Chao J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:4107–4110. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer M. P. Yu Y. Chao J. Aki C. Chao J. Biju P. Girijavallabhan V. Rindgen D. Bond R. Mayer-Ezel R. Jakway J. Hipkin R. W. Fossetta J. Gonsiorek W. Bian H. Fan X. Terminelli C. Fine J. Lundell D. Merritt J. R. Rokosz L. L. Kaiser B. Li G. Wang W. Stauffer T. Ozgur L. Baldwin J. Taveras A. G. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7603–7606. doi: 10.1021/jm0609622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. Yang T. Xu Z. Wren P. B. Zhang Y. Cai X. Patel M. Dong K. Zhang Q. Zhang W. Guan X. Xiang J. Elliott J. D. Lin X. Ren F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:5493–5496. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. J. Reddington M. V. Wilcox C. S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6085–6088. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. Light M. E. Davis A. P. Gale P. A. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7641–7643. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12439k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busschaert N. Kirby I. L. Young S. Coles S. J. Horton P. N. Light M. E. Gale P. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4426–4430. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Zhang J. Stein P. D. Shi M. O'Connor S. P. Bisaha S. N. Li C. Atwal K. S. Bisacchi G. S. Sitkoff D. Pudzianowski A. T. Liu E. C. Hartl K. S. Seiler S. M. Youssef S. Steinbacher T. E. Schumacher W. A. Rendina A. R. Bozarth J. M. Peterson T. L. Zhang G. Zahler R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:5453–5458. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métayer B. Compain G. Jouvin K. Martin-Mingot A. Bachmann C. Marrot J. Evano G. Thibaudeau S. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:3397–3410. doi: 10.1021/jo502699y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. R. Kim J. Lee S. Y. Park Y. H. Kim H. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:2080–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppeler F. Iwan D. Wojaczyńska E. Wojaczyński J. Molecules. 2020;25:401. doi: 10.3390/molecules25020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A. R. Garai S. Thakur G. A. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:992–999. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger D. Gutmann B. Kappe O. C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:1330–1341. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlin F. Lanari D. Vaccaro L. Green Chem. 2020;22:5937–5955. [Google Scholar]

- Plutschack M. B. Pieber B. Gilmore K. Seeberger P. H. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:11796–11893. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioiello A. Piccinno A. Lozza A. M. Cerra B. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:6624–6647. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan A. R. Dombrowski A. W. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:6422–6468. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. L. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018;22:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K. Brindisi M. Sarkar A. ChemMedChem. 2018;13:2351–2373. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M. Moody T. S. Smyth M. Wharry S. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020;24:1802–1813. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.4c00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipponi P. Ostacolo C. Novellino E. Pellicciari R. Gioiello A. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014;18:1345–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M. Baxendale I. R. Ley S. V. Nikbin N. Smith C. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:1577–1586. doi: 10.1039/b801631n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M. Baxendale I. R. Ley S. V. Nikbin N. Smith C. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:1587–1593. doi: 10.1039/b801634h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bana P. Lakó Á. Kiss N. Z. Béni Z. Szigetvári Á. Kóti J. Túrós G. I. Éles J. Greiner I. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2017;21:611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Németh A. G. Szabó R. Orsy G. Mándity I. M. Keserű G. M. Ábrányi-Balogh P. Molecules. 2021;26:303. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesco-Domínguez A. Blanco-Ania D. Rutjes F. P. J. T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018;11:1312–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Kappe C. O. Dallinger D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:51–63. doi: 10.1038/nrd1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draye M. Chatel G. Duwald R. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13:23. doi: 10.3390/ph13020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawełczyk A. Sowa-Kasprzak K. Olender D. Zaprutko L. Molecules. 2018;23:2360. doi: 10.3390/molecules23092360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnaroglio D. Martina K. Palmisano G. Penoni A. Domini C. Cravotto G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013;9:2378–2386. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca L. Porcheddu A. Giacomelli G. Murgia I. Synlett. 2010;16:2439–2442. [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh H. Dinparast L. Monatsh. Chem. 2012;143:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chau C.-M. Chuana T.-J. Liu K.-M. RSC Adv. 2014;4:1276–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Velupula G. Prasada T. R. Valluru K. R. Konidena L. N. S. Maroju S. Mule S. N. R. Chem. Data Collect. 2021;31:100615. [Google Scholar]

- Odame F. Hosten E. C. Lobb K. Tshentu Z. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1216:128302. [Google Scholar]

- Macarie L. Simulescu V. Ilia G. Monatsh. Chem. 2019;150:163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Crisenza G. E. M. Melchiorre P. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:803. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13887-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten C. Nicholls T. P. Bourne R. A. Kapur N. Nguyen B. N. Willans C. E. Green Chem. 2020;22:3358–3375. [Google Scholar]

- Yan M. Kawamata Y. Baran P. S. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:13230–13319. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. Xu K. Zeng C. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4485–4540. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas B. Kumari V. D. Sadanandam G. Hymavathi C. Subrahmanyam M. De B. R. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012;88:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumavat P. P. Jangale A. D. Patil D. R. Dalal K. S. Meshram J. S. Dalal D. S. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2013;11:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gan Z. Li G. Yan Q. Deng W. Jiang Y.-Y. Yang D. Green Chem. 2020;22:2956. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Deng Y. Shi F. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2001;176:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarotto I. Feroci M. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7137–7139. doi: 10.1021/jo034750d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N. Khatoon S. ChemistryOpen. 2018;7:576–582. doi: 10.1002/open.201800064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]