Abstract

Chromobacterium violaceum is a facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative rod found in different ecosystems, especially tropical and subtropical areas. Human infections are rare, and just a few cases have been reported in literature. In this paper, we present the first non-lethal infection due to Chromobacterium violaceum, in an adult male with polycystic kidney disease in Colombia. Periareolar soft tissue infection was documented with isolation of Chromobacterium violaceum. Clinical manifestations, treatment, and outcome are shown.

Keywords: Chromobacterium violaceum, periareolar infection, soft tissue infection

1. Introduction

Chromobacterium violaceum is a facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative rod of the Neisseriaceae family that is considered an opportunistic pathogen. It is mainly found in water and soil; transmission is by contact with organic material and (to a lesser extent) by contaminated water ingestion [1,2]. Mortality rates range between 65 and 80% [2]. Until 2021, 200 cases had been reported worldwide, with two in Colombia—one of them in a child [3] and the latter in an adult [4], both with fatal outcomes. In this paper, we present the first non-fatal soft tissue infection due to Chromobacterium violaceum in an adult with polycystic kidney disease in Colombia, with a favorable outcome.

2. Case Report

A 47-year-old man (an employee of the hotel sector from Bogotá) with a past medical history of polycystic kidney disease presented to the emergency room with complaints of one week of erythema and purulent drainage of the anterior chest wall associated with a fever of up to 38.5 °C. He received cephalexin during a three-day course without any improvement.

Upon physical examination, he was in no acute distress, and his skin exam was remarkable for an erythematous left periareolar nodule with swelling, warm, and purulent discharge (Figure 1), along with signs of systemic inflammatory response without clinical findings of sepsis organic dysfunction (Table 1). The patient started on therapy with intravenous clindamycin. However, he deteriorated due to the worsening of chronic kidney disease with the further requirement of renal replacement therapy.

Figure 1.

Periareolar lesion with erythematous borders and purulent discharge.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings.

| Laboratory | Admission | Discharge |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 22.03 × 103/µL | 11.92 × 103/µL |

| Neutrophils | 18.9 × 103/µL (85.9%) | 6.6 × 103/µL (55.2%) |

| Lymphocytes | 1.33 × 103/µL (6%) | 3.56 × 103/µL (29.9%) |

| Monocytes | 1.61 × 103/µL (7.3%) | 1.18 × 103/µL (9.90%) |

| Red blood cells | 3.89 × 106/µL | 3.35 × 106/µL |

| Hematocrit | 33.3% | 29% |

| Hemoglobin | 11.2 g/dL | 9.70 g/dL |

| MCV | 85.6 fl | 86.6 fl |

| MCH | 28.8 pg | 29 pg |

| MCHC | 33.6 g/dL | 33.4 g/dL |

| RDW | 12.7% | 12.5% |

| Platelets | 264 × 103/µL | 407 × 103/µL |

| C-reactive protein | 176.4 mg/L | 12.29 mg/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 89.7 mg/dL | 74.3 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 9.14 mg/dL | 5.16 mg/dL |

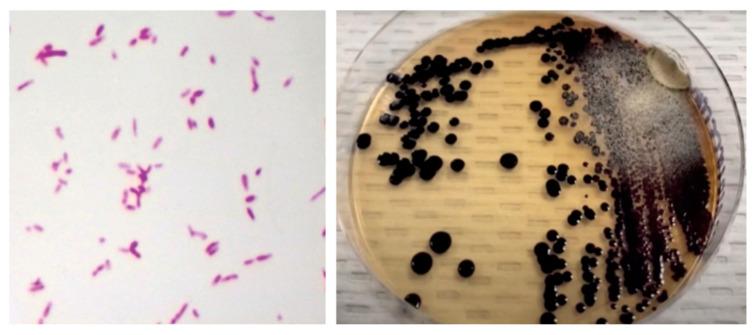

The patient was taken to surgery, where a 15-cm abscess with skin necrosis over the area of renitence was found. The cytochemical results of the abscess showed abundant leukocytes and the isolation of Chromobacterium violaceum (Figure 2). Antibiograms were not made, and blood cultures were negative. The patient continued intravenous clindamycin with no improvement at the third day of admission, so doxycycline was started at a 100 mg BID dosage with partial response. At day five of admission, he was taken to another surgical procedure, and negative pressure therapy was placed over his wound. This therapy allows one to draw fluid from an infected site using a vacuum system, which is especially useful for deep, complicated, and nonhealing wounds. The antibiotic was again changed to tigecycline at a 50 mg BID dosage for ten days.

Figure 2.

(Left) Gram stain of skin abscess showing Gram-negative coccobacillary forms. (Right) nutritive agar with black-violet mucoid colonies consistent with Chromobacterium violaceum.

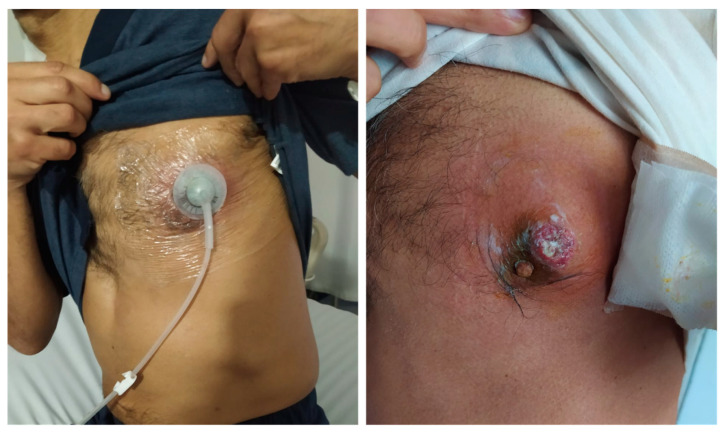

After five days of tigecycline, he underwent surgery again, negative pressure therapy was withdrawn, and the wound was covered with a fasciocutaneous flap. He was discharged after completing 10 days of antibiotic treatment, with no signs of systemic inflammatory response and with adequate closure of the skin wound (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lesion evolution at discharge, after antibiotic and negative pressure therapy.

3. Discussion

Chromobacterium violaceum is a facultative anaerobic, carbohydrate fermenter, catalase-positive, and Gram-negative bacillus. It grows on blood, chocolate, and MacConkey agar within 18–24 h and can produce pigmented colonies due to the production of violacein, a metabolite with apoptotic activity on some cells [5]. Nonetheless, it can also grow as unpigmented colonies.

This microorganism adheres through the CopE membrane protein, which induces rearrangement in the actin cytoskeleton, thus leading to damage in epithelial cells. Furthermore, metalloproteinase (MMP-2) with elastase activity facilitates the production of abscesses, and two type III secretion systems, which are involved in the signal transduction cascade that favor cytotoxicity by allowing for pore formation in host cell membranes, have been described [5].

Skin and soft tissue infections due to this Gram-negative bacteria mainly occur in patients with risk factors—either environment-related, such as exposure to organic or contaminated surfaces (especially if there is a loss of continuity of the skin) or host-related, such as chronic immunosuppression conditions like diabetes mellitus, chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency [6].

There are two ways to explain the susceptibility to Chromobacterium violaceum infections in patients with these last two conditions: The first is related to the dysfunction of the phagocytic cell to eliminate the bacteria, since the production of peroxide is altered due to the deficiency of NADPH and NADPH oxidase. The hydrogen peroxide necessary for phagocytic activity comes from two routes: first after the action of lysosomal enzymes and acid hydrolases, and second through the action of the enzyme NADPH oxidase. Catalase-positive microorganisms such as Chromobacterium violaceum disable the production of lysosomal hydrogen peroxide, leaving only the NADPH route in charge of its production for phagocytic action. Thus, in conditions like CGD and G6PD deficiency where NADPH production is compromised, there is a major susceptibility to infections due to these microorganisms [7]. The second mechanism refers to the inadequate formation of the inflammasome; it has been reported that NADPH pathway is directly involved with the regulation of the latter, so any alteration in the NADPH production (as in CGD and G6PDH) would directly affect the destruction of inflammasome-dependent microorganisms, such as Burkholderia cepacia and Chromobacterium violaceum [8,9,10].

The association of Chromobacterium violaceum infection with CGD has been previously described, mainly in children since the hereditary nature of the disease and almost none in adults with skin and soft tissue infections [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Nonetheless, this association does not seem to be directly related to an increase in mortality [28]. Fewer cases of infections in patients with G6PDH deficiency have been reported, perhaps because of the rarity of the disease, so it is not possible to set a mortality trend in this condition [29,30]. In our patient, the only triggering factor corresponded to an insect bite, which had been previously reported in two cases [12,22].

To date, 27 cases of skin and soft tissue infection by Chromobacterium violaceum have been reported in adults (Table 2), mainly described in males of ages between 20 and 50 years old, with an average of 46 years. Most of them have presented with an acute onset of symptoms, frequently requiring hospitalization in the first week [16,19,20,22,25,27]: 44% of infections have presented with bacteremia and 51% have led to sepsis, with mortality as high as 22%. Bacterial growth in culture has ranged from 15 to 72 h, except for a single reported case of 10 days. In most cases, the definitive treatment was found to be a beta-lactam and fluoroquinolone combination, consistent with most reported susceptibility profiles where resistance to penicillins, aminopenicillins, and cephalosporins, as well as sensitivity to carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, is frequent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chromobacterium violaceum skin and soft tissue infections reported worldwide.

| Author/Year | Age and Gender | Clinical Manifestations | Related Condition | Time to Positive Culture | Bacteremia | Sepsis | Resistance Profile | Antibiotic Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sneath et al. [11] (1953) | Not reported (M) | Left thigh ulcer with inguinal lymphadenopathy fever and hepatomegaly. | Not reported. | 24 h | Yes | Yes | Not reported | TCY | Septic shock and multi-organ dysfunction. Death 26 days after admission. |

| Kaufman et al. [12] (1986) | 44 yo (F) | Ulcerated nodules and purpura in the abdomen, limbs, and back. Fever, abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. | Exposure to contaminated water. Wasp sting. | 24 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: MZL, GEN, CLO, TCY, CMX CBN, NMC, and NTM Resistant: PEN, AMP, AMK, TOB, PMX B, and CFS |

MEZ and GEN | Septic shock. Death at 6 weeks after admission. |

| Georghiou et al. [13] (1989) | 35 yo (M) | Posterior neck wound. Twelve days later: extension to the right shoulder with abscess, abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhoea. | Abrasion while carrying old damp floor-covering on that shoulder | 24 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: GEN, CIP, and CLO, IPM, TOB, and AMC Resistant: ATM, AMX, SXT, and CEP |

GEN, IPM, and CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Huffman et al. [14] (1998) | 46 yo (M) | Three weeks of malaise, hyporexia, nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, 7 kg loss, left thigh wound, and liver abscess. | Heavy smoking. | 24 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: GEN, CIP, CLO, TCY, IPM, and SXT Resistant: CRO, AMC, and CAZ |

CLO, GEN, and TCY | Resolved. Neuropathy as a sequel of the disease. |

| Huffman et al. [14] (1998) | 53 yo (M) | 7 mm wound on the sole of the left foot; six days later: fever, pain, and purulent discharge. | Diabetes mellitus. Wound with rusty metal. | Not reported | No | No | Sensitive: GEN, CIP, IPM, PIP, TOB, and AMC Resistant: CAZ |

AMC, GEN, DOX, and CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Dan et al. [15] (2001) | 24 yo (M) | Pimple in right cheek with purulent discharge for three weeks. Fever, headache, and dizziness for 2 weeks. Brain abscess was reported. | Farm laboring. | 24 h | No | No | Sensitive: IPM and CIP Resistant: CTX and CRO |

CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Hee kim et al. [1] (2005) | 38 yo (M) | Polytrauma with multiple wounds, rib fractures, empyema, hemothorax, tibial fracture, kidney, and liver hematoma. | Hit by a car while fishing. Contaminated water exposure. | Not reported | No | No | Sensitive: CIP, AMK, GEN, TZP, LVX, and SXT, Resistant: CRO, AMP, TOB, SAM, and FEP |

CFA and AZM | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Teoh et al. [16] (2006) | 40 yo (M) | 1 cm forearm abscess. One day later: purulent discharge epigastric pain and fever. Peritonitis was reported. | Forearm wound during camping near a lagoon. | Not reported | Yes | Yes | Not reported | CIP, MDZ, and CTX | Septic shock. Death at 20 h after admission. |

| Lim et al. [17] (2009) | 40 yo (F) | Anterior chest wall wound. Malaise, fever, chills, lumbar pain, and headache. Apical pansystolic murmur, liver abscess, and vegetations on the coronary cusps. | Wound with a tree branch during lake swimming. | 28–39 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: CIP, TZP, and MEM, IPM, SXT, and CFX Resistant: AMP, CXM, and CAZ |

MEM and CIP | Liver abscess and infective endocarditis resolved after 6–11 weeks, respectively. Alive. |

| Yang et al. [18] (2011) | 64 yo (M) | Right foot erythematous lesion with pain and edema. Headache and fever. | Diabetes mellitus and hepatitis B infection. Fish bite in a river. | 10 days | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: CIP, TZP, and MEM, LVX, ATM, CAS, and FEP Intermediate: GEN and AMK Resistant: SAM |

CRO, CIP, and DOX | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Kumar et al. [19] (2012) |

42 yo (M) | Head and leg lesions. Seven days later: pain, swelling, and purulent discharge. | Exposure to contaminated water. | 24 h | No | No | Sensitive: GEN, CIP, and AMK, CLO, TCY, CAZ, and IPM Intermediate: CTX Resistant: PEN and CFX |

GEN | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Ansari et al. [20] (2015) | 45 yo (M) | Wound in the middle finger of the left hand. Seven days later: fever, epigastric pain, swelling, and purulent discharge. | Stinging wound with unknown object. | 12 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: AMK, GEN, CIP, TZP, MEM, CRO, SXT, AMC, MDZ, and FLX. | TZP, FLX, and MDZ. | Septic shock and death 21 h after admission. |

| Madi et al. [21] (2015) | 53 yo (F) | Left leg lesion. Two weeks later: abdominal pain and vomiting; the lesion then ulcerated. Hepatomegaly and jaundice. | Skin trauma during farm laboring. | Not reported | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: CIP, TZP, MEM IPM, SXT, and CFX Resistant: AMP, CXM, and CAZ |

IPM, CIP, and TZP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 23 yo (F) | Limb injury. Eight months later: granulation tissue in the wound. | Wound contamination in muddy field. | Not reported | No | No | All isolates were sensitive to CIP, MEM FEP, and GEN | TZP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 42 yo (F) | Chest wall wound. | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes | TZP, MEM, and GEN | Sepsis, mesenteric ischemia, abdominal abscess and fat necrosis. Deceased. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 53 yo (F) | Limb wound, diabetic foot with infection, and abscess. | Diabetes mellitus | Not reported | No | No | GEN and SXT | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 52 yo (M) | Post-surgical infected sternotomy wound. | Myocardial revascularization | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | TZP | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 32 yo (M) | Lacerating injury on the toes with purulent discharge. | Wound during swamp hike. | Not reported | No | No | SXT | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 57 yo (M) | Anterior chest wall wound. | Found unconscious in a swamp. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | MEM | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 45 yo (M) | Wound on the palm of the hand. | Stab wound. Possible contaminated metal. | Not reported | No | No | DOX | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 50 yo (M) | Wound on toe | Not reported | Not reported | No | No | CZO and DOX | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Lin et al. [22] (2016) | 21 yo (M) | Stinging wound with abscess in upper limb. | Spider bite. | Not reported | No | No | FLX and AMC | Alive, fully recovered. | |

| Matsuura et al. [23] (2017) | 69 yo (F) | Internal malleolus wound in right leg, fever, and liver abscess. | Rice cultivation and contaminated water. | 72 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: LVX, GEN, TCY, and SXT Resistant: All betalactams. |

CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Sachu et al. [24] (2020) | 76 yo (F) | Several pustulous skin lesions predominantly in the right forearm; intermittent fever. | Myelodysplastic syndrome, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, diabetes mellitus type 2, typhoid fever, and recurrent urinary tract infection. Exposure to contaminated water. | 15 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: AMK, GEN, CIP, MEM, and LVX Resistant: AMP, AMC, and CFS |

MEM | Septic shock, acute kidney failure and death 72 h later. |

| Khadanga et al. [25] (2020) | 62 yo (M) | Left foot ulcer with necrosis associated with five days of abdominal pain and hepatomegaly. | Diabetes mellitus/ | 8 h | Yes | Yes | Sensitive: CIP, GEN, AMK, TZP, TCY, CAZ, FEP, IPM, NTM, and GFX. Resistant: AMP, AMC, and CTX |

CRO, VAN, and CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Mazumder et al. [26] (2020) | 40 yo (M) | Left ankle contusion. Fifteen days later: fever, chills, abdominal pain, sweating, and purulent discharge from the wound. | Contusion in rice crop fields and contaminated water exposure. | 12 h | No | No | Sensitive: AMK, AZM, CIP, NIT, TZP, MEM, IPM, LVX, ETP, SXT, GEN, TOB, and NTM Resistant: CRO, AMP, CAZ, CTX, AMC, COL, PMX B, and CFM |

MEM and CIP | Alive, fully recovered. |

| Zhang et al. [27] (2021) | 50 yo (M) | Left leg wound. Seven days later: ulceration, bleeding, purulent discharge, and necrosis. | Wound while laboring in the field. | 24 h | No | No | Sensitive: TZP, CIP, AMK, MEM, LVX, IPM, TGC, and CFP Resistant: AMP, PEN, and CFS |

TZP and LVX | Alive, fully recovered. |

AMK: amikacin; AZM: azithromycin; CIP: ciprofloxacin; NIT: nitrofurantoin; TZP: piperacillin/tazobactam; CLI: clindamycin; GEN: gentamicin; MEM: meropenem; CRO: ceftriaxone; TCY: tetracycline; CAZ: ceftazidime; FEP: cefepime; IPM: imipenem; AMP: ampicillin; AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanate; CTX: cefotaxime; PIP: piperacillin; AMX: amoxicillin; CEP: cephalothin; NTM: netilmicin; CFM: cefixime; CFX: cefoperazone/sulbactam; MZL: mezlocillin; PEN: penicillin; CFS: cephalosporins; CMX: cotrimoxazole; CBN: carbenicillin; GFX: gatifloxacin; CZO: cefazolin; DOX: doxycycline; MEZ: mezlocillin; CFA: cefpodoxime acid; CTN: cefoxitin; OXA: oxacillin; LVX: levofloxacin; ATM: aztreonam; SAM: ampicillin/sulbactam; SXT: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; VAN: vancomycin; CXM: cefuroxime; ETP: ertapenem; MDZ: metronidazole; CLO: chloramphenicol; COL: colistin; TOB: tobramycin; PMX B: polymyxin B; TGC: tigecycline; FLX: flucloxacillin.

The patient in this case presented a severe clinical course, with organ dysfunction and with requirement of multiple surgical procedures to control the infectious source. The patient had an inappropriate response to initial antimicrobial therapy, which is consistent with previous reported cases where broad spectrum antibiotic combinations were required for control of the infection. However, in comparison with the two other reported cases in Colombia, both of them with fatal outcomes, he did not present bacteremia during his clinical course. In fact, bacteremia and sepsis were present in all of the reviewed cases of skin and soft tissue infections with fatal outcomes, suggesting that the dissemination of the infection into the bloodstream is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes and mortality.

In Colombia, this is the first case of non-lethal infection by Chromobacterium violaceum, and it was the first one of skin and soft tissue infection (Table 3). In Latin America, it corresponds to the first case of non-lethal skin and soft tissue infection [18]

Table 3.

Chromobacterium violaceum infections reported in Colombia.

| Author | Year | Age | Gender | Bacteremia | Resistance Profile | Antibiotic Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Díaz J, et al. [22] | 2007 | 38 | M | Yes | Sensitive: IPM, MEM, and TZP Resistant: GEN, AZM, AMK, CRO, FEP, CTX, CAZ, CIP, and PIP |

CIP, CRO, and OXA | Death |

| Mattar S, et al. [23] | 2007 | 4 | M | Yes | Sensitive: CLO, TCC, SXT, and CIP Resistant: AMP, CFS, CTN, CRO, CTX, CAZ, ATM, IPM, AMK, GEN, and TOB |

CRO, AMK, and CIP | Death |

AMK: amikacin; AZM: azithromycin; CIP: ciprofloxacin: TZP: piperacillin/tazobactam; GEN: gentamicin; MEM: meropenem; CRO: ceftriaxone; TCY: tetracycline; CAZ: ceftazidime; FEP: cefepime; IPM: imipenem; AMP: ampicillin; AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanate; CTX: cefotaxime; PIP: piperacillin; CFS: cephalosporins; CTN: cefoxitin; OXA: oxacillin; ATM: aztreonam; SXT: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; TOB: tobramycin; PMX B: polymyxin B; TGC: tigecycline; FLX: flucloxacillin.

4. Conclusions

Chromobacterium violaceum has been reported since 1927 as the cause of severe infections, with a trend towards immunocompromised populations and patients of reproductive age with skin trauma. Thus far, the inflammasome and NADPH pathway dysfunction are the most studied predisposing factors for infection, while the presence of bacteremia is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes and mortality. The mechanisms of antibiotic resistance are not yet clear, but carbapenems and fluoroquinolones are the most widely used antibiotics in hospitalized patients.

Many factors contributed to clinical cure in the presented case, including an adequate control of infectious source and tissue debridement, the absence of bloodstream infection, and a strong antibiotic therapy. More studies are required to understand the dynamics of this microorganism and its clinical implications.

Author Contributions

Data collection and process D.A.C.D., D.A.M., N.B.O., A.L.O.M. and V.H.A. Conceptualization D.A.C.D. and D.A.M. Images and translation Y.F.M.F., D.A.C.D. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de La Sabana Clinic.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant information has been presented in the case report. Any additional data may be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kim M.H., Lee H.J., Suh J.T., Chang B.S., Cho K.S. A case of chromobacterium infection after car accident in korea. Yonsei Med. J. 2005;46:700–702. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.5.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gómez M., Santos A., Guevara A., Rodríguez C. Reporte de dos casos de inusual infección no letal por Chromobacterium violaceum. Revisión literaria. Infectio. 2017;21:129–131. doi: 10.22354/in.v21i2.657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattar S., Martinez P. Case report fatal septicemia caused by Chromobacterium violaceum in a child from colombia. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo. 2007;49:391–393. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000600011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander Díaz Pérez J., García J., Andrea Rodriguez Villamizar L., Alexander Díaz J. Sepsis by Chromobacterium violaceum: First Case Report from Colombia [Internet] Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;11:441–442. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Justo G.Z., Durán N. Action and function of Chromobacterium violaceum in health and disease: Violacein as a promising metabolite to counteract gastroenterological diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017;31:649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C.H., Li Y.H. Chromobacterium violaceum infection: A clinical review of an important but neglected infection. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2011;74:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal B.H., Ding L., Holland S.M. Phagocyte NADPH oxidase, but not inducible nitric oxide synthase, is essential for early control of Burkholderia cepacia and Chromobacterium violaceum infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:205–210. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.205-210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abais J.M., Zhang C., Xia M., Liu Q., Gehr T.W.B., Boini K.M., Li P.L. NADPH oxidase-mediated triggering of inflammasome activation in mouse podocytes and glomeruli during hyperhomocysteinemia. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013;18:1537–1548. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batista J.H., da Silva Neto J.F. Chromobacterium violaceum pathogenicity: Updates and insights from genome sequencing of novel Chromobacterium species. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2213. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee D., Raghunathan A. Constraints-based analysis identifies NAD + recycling through metabolic reprogramming in antibiotic resistant Chromobacterium violaceum. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0210008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sneath P.H.A., Bhagwan S.R., Whelan J.P.F., Edwards D. Fatal infection by Chromobacterium violaceum. Lancet. 1953;262:276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(53)91132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman S.C., Ceraso D., Schugurensky A. First Case Report from Argentina of Fatal Septicemia Caused by Chromobacterium violaceum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986;23:956–958. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.5.956-958.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georghiou P.R., O’Kane G.M., Siu S., Kemp R.J. Near-fatal septicaemia with Chromobacterium violaceum. Med. J. Aust. 1989;150:720–721. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huffam S.E., Nowotny M.J., Currie B.J. Notable Cases Chromobacterium violaceum in tropical northern Australia. Med. J. Aust. 1998;168:335–337. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb138962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dan M., Poch F., Shpitz D., Sheinberg B. An Unusual Bacterium Causing a Brain Abscess. Report on emerging issues. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001;7:159. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teoh A.Y.B., Hui M., Ngo K.Y., Wong J., Lee K.F., Lai P.B.S. Case Report Fatal septicaemia from Chromobacterium violaceum: Case reports and review of the literature. Hong Kong Med. J. 2006;12:228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim I.W.M., Stride P.J., Horvath R.L., Hamilton-Craig C.R., Chau P.P. Chromobacterium violaceum endocarditis and hepatic abscesses treated successfully with meropenem and ciprofloxacin. Med. J. Aust. 2009;190:386–387. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang C.H. Nonpigmented Chromobacterium violaceum bacteremic cellulitis after fish bite. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2011;44:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar M. Chromobacterium violaceum: A rare bacterium isolated from a wound over the scalp. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2012;2:70. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.96814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ansari S., Paudel P., Gautam K., Shrestha S., Thapa S., Gautam R. Chromobacterium violaceum Isolated from a Wound Sepsis: A Case Study from Nepal. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2015;2015:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2015/181946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madi D.R., Vidyalakshmi K., Ramapuram J., Shetty A.K. Case report: Successful treatment of Chromobacterium violaceum sepsis in a south indian adult. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;93:1066–1067. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y.D., Majumdar S.S., Hennessy J., Baird R.W. The spectrum of Chromobacterium violaceum infections from a single geographic location. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016;94:710–716. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura N., Miyoshi M., Doi N., Yagi S., Aradono E., Imamura T., Koga R. Multiple liver abscesses with a skin pustule due to Chromobacterium violaceum. Intern Med. 2017;56:2519–2522. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.8682-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachu A., Antony S., Mathew P., Sunny S., Koshy J., Kumar V., Mathew R. Chromobacterium violaceum causing deadly sepsis [Internet] Iran. J. Microbiol. 2020;12:364. doi: 10.18502/ijm.v12i4.3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khadanga S., Karuna T., Dugar D., Satapathy S.P. Chromobacterium violaceum-induced sepsis and multiorgan dysfunction, resembling melioidosis in an elderly diabetic patient: A case report with review of literature. J. Lab. Physicians. 2017;9:325–328. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_21_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazumder R., Sadique T., Sen D., Mozumder P., Rahman T., Chowdhury A., Halim F., Akter N., Ahmed D. Agricultural Injury–Associated Chromobacterium violaceum Infection in a Bangladeshi Farmer. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103:1039–1042. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P., Li J., Zhang Y.Z., Li X.N. Chromobacterium violaceum infection on lower limb skin: A case report. Medicine. 2021;100:e24696. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meher-Homji Z., Mangalore R.P., Johnson P.D.R., Chua K.Y.L. Chromobacterium violaceum infection in chronic granulomatous disease: A case report and review of the literature. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005084. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thwe P.M., Ortiz D.A., Wankewicz A.L., Hornak J.P., Williams-Bouyer N., Ren P. The Brief Case: Recurrent Chromobacterium violaceum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58:6–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00312-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamlok R.J., Mamiok V., Mills G.C., Daeschner C.W., Schmalstieg F.C., Anderson D.C. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, neutrophil dysfunction and Chromobacterium violaceum sepsis. J. Pediatr. 1987;111:852–854. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant information has been presented in the case report. Any additional data may be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.