Summary

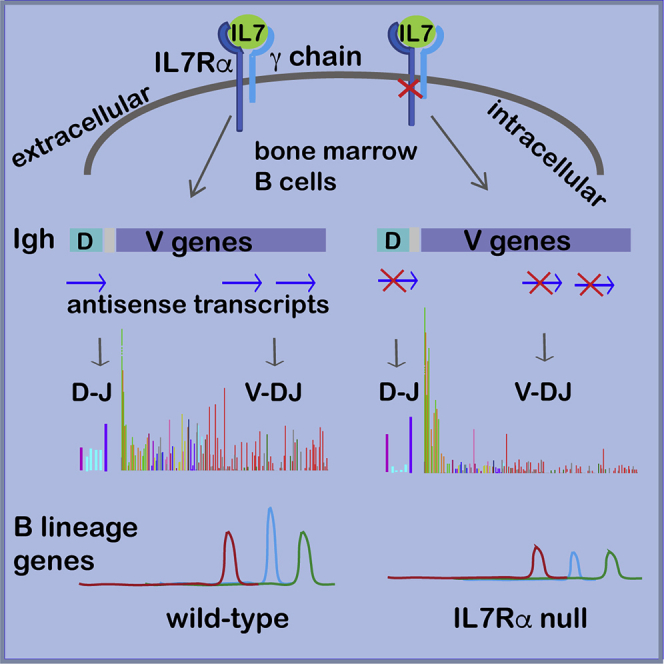

Generation of the primary antibody repertoire requires V(D)J recombination of hundreds of gene segments in the immunoglobulin heavy chain (Igh) locus. The role of interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R) signaling in Igh recombination has been difficult to partition from its role in B cell survival and proliferation. With a detailed description of the Igh repertoire in murine IL-7Rα−/− bone marrow B cells, we demonstrate that IL-7R signaling profoundly influences VH gene selection during VH-to-DJH recombination. We find skewing toward 3′ VH genes during de novo VH-to-DJH recombination more severe than the fetal liver (FL) repertoire and uncover a role for IL-7R signaling in DH-to-JH recombination. Transcriptome and accessibility analyses suggest reduced expression of B lineage transcription factors (TFs) and targets and loss of DH and VH antisense transcription in IL-7Rα−/− B cells. Thus, in addition to its roles in survival and proliferation, IL-7R signaling shapes the Igh repertoire by activating underpinning mechanisms.

Keywords: B lymphocyte development, Igh recombination, interleukin-7 receptor signaling, bone marrow, fetal liver, pro-B cells, Pax5 transcription factor, antisense transcription, chromatin accessibility

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The IL-7R drives recombination of VH and DH genes in the immunoglobulin heavy chain

-

•

Deletion of the IL-7R impairs usage of all except 3′ VH and flanking DH genes

-

•

IL-7R loss diminishes large-scale VH and DH antisense transcription in the Igh

-

•

IL-7R loss causes reduced expression of B lineage transcription factors and targets

Baizan-Edge et al. show that the interleukin-7 receptor drives antibody repertoire diversity. Deletion of the IL-7R impairs usage of most VH genes and DH genes in V(D)J recombination of the Igh, causing a severely restricted repertoire. Defects include reduced Igh antisense transcription and diminished expression of B lineage transcription factors.

Introduction

Interleukin-7 (IL-7) is a critical cytokine for B and T lymphocyte development. It is bound by the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R), composed of the common gamma chain (γc), shared with the IL-2R, and the IL-7-specific IL-7Rα chain (CD127—encoded by Il7r), which also pairs with the thymic stromal lymphopoietin receptor (TSLPR), important in fetal liver (FL) B cell survival (Vosshenrich et al., 2003; Rochman et al., 2009). Binding of IL-7 to the IL-7R in pro-B cells activates several signaling pathways, including Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT), phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt (Protein kinase B), mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK), and PLCγ/PKC/mammalian target of Rapamycin (mTOR), and has been associated with proliferation and survival, B lineage commitment, and Igh recombination (Corcoran et al., 1996, 1998; reviewed by Corfe and Paige, 2012; Yu et al., 2017).

IL-7R signaling is essential for B lineage commitment. Its absence in IL-7Rα−/− mice impairs early B cell development from the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) stage, resulting in reduced progenitors and impaired B-lineage potential (Peschon et al., 1994; Miller et al., 2002; Erlandsson et al., 2004; Dias et al., 2005, Medina et al., 2013). This is due in part to failure to activate early B-Cell Factor 1 (EBF1), a crucial transcription factor (TF) for B lineage specification (Kikuchi et al., 2005; Tsapogas et al., 2011; Pongubala et al., 2008; Roessler et al., 2007; Boller and Grosschedl, 2014). Paired box 5 (PAX5), a key TF for B cell commitment (Nutt et al.; 1999; Rumfelt et al., 2006), is also reduced in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells (Corcoran et al., 1998), but this may be due to reduced EBF1 expression (O’Riordan and Grosschedl 1999; Decker et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010). However, some cells progress to the pre-pro-B stage (Kikuchi et al., 2005; Peschon et al., 1994; Miller et al., 2002) and fewer to the CD19+ pro-B compartment (Corcoran et al., 1998; Miller et al., 2002).

Although IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells in the bone marrow (BM) undergo Igh VH-DJH recombination (Corcoran et al., 1998), their usage of VH genes is severely restricted, indicating a role of IL-7R signaling in this process. Importantly, this is independent of proliferation: IL-7Rα−/− cells expressing an IL-7Rα chain lacking Tyr449, required for PI3K signaling, express a recombined Igμ polypeptide but do not proliferate in vitro (Corcoran et al., 1996). Conversely, a chimeric receptor comprising the IL-7Rα extracellular domain and the IL-2Rβ intracellular domain restored proliferation in IL-7Rα−/− cells, but not Igμ expression, indicating a non-redundant role for the IL-7R in Igh V(D)J recombination.

A diverse antibody repertoire requires inclusion of all available VH and DH genes. Large-scale processes, including non-coding transcription and Ig locus contraction, are thought to facilitate accessibility of distal 5′ VH genes to the recombination center over the DJ region, where the recombination activating gene (RAG) 1 and 2 bind (Ji et al., 2010, Corcoran et al., 1998; Bolland et al., 2004; Yancopoulos and Alt, 1985, Chowdhury and Sen, 2003; Fuxa et al., 2004; Jhunjhunwala et al., 2008; Sayegh et al., 2005; Stubbington and Corcoran, 2013). Nevertheless, VH genes recombine at widely different frequencies; frequently recombining VH genes also have one of two local active chromatin states (Bolland et al., 2016).

IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells in vivo displayed decreased non-coding transcription and recombination of 5′ VH genes (Corcoran et al., 1998), prompting the hypothesis that the IL-7R influences Igh recombination through increasing accessibility of 5′ VH genes, supported by studies linking IL-7R signaling and active histone modifications in the Igh locus (Chowdhury and Sen, 2001; Johnson et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2008), and suggesting that IL-7R activation of the Igh locus is mediated by STAT5 (Bertolino et al., 2005). However, conditional deletion of STAT5 was rescued by the pro-survival factor B-Cell Lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) with no deficiency in 5′ VH recombination, suggesting that the dominant role of STAT5 was pro-B cell survival (Malin et al., 2010). IL-7Rα−/− B cells were only partially rescued and cannot be rescued by Eu-BCL-2 expression (Maraskovsky et al., 1998), indicating that the IL-7R has additional downstream signaling roles. Heterogeneous expression of the IL-7R during the cell cycle both inhibits Rag recombinase expression to prevent DNA breaks during replication, while maintaining Igh locus accessibility throughout the cell cycle (Johnson et al., 2012).

Other studies have suggested that loss of IL-7Rα prevents B cell progression beyond the pre-pro-B stage and that B cells in the BM originate from the FL (Kikuchi et al., 2005; Peschon et al., 1994; Miller et al., 2002; Carvalho et al., 2001), supported by similarity in VH repertoire between IL-7Rα−/− and FL B cells (Corcoran et al., 1998; Jeong and Teale, 1988; Yancopoulos et al., 1988). Definitive conclusions have been hampered by incomplete knowledge of the Igh locus, provided later (Johnston et al., 2006), and low-resolution Igh repertoire assays.

With next-generation sequencing (NGS) enabling more comprehensive analysis of Igh repertoires, we have revisited the IL-7Rα−/− mouse (Peschon et al., 1994) to address the uncertainties above, which confound a complete picture of the role of the IL-7R in B cell development. Using VDJ sequencing (VDJ-seq) (Bolland et al., 2016), a DNA-based NGS technique, we have fully characterized the Igh DJH and VDJH repertoires in IL-7Rα−/− BM B cells. Widespread use of gene segments in both DH-JH and VH-DH recombination was severely impaired by loss of IL-7R signaling.

Importantly, IL-7Rα−/− BM B cells are not derived from the FL. Junctions between VH, DH, and JH gene segments in IL-7Rα−/− BM B cells are much more variable than FL B cell sequences, indicating that IL-7Rα−/− BM pro-B cells undergo de novo V(D)J recombination. Furthermore, they have a much more severe reduction in repertoire diversity than FL. Transcriptome analysis reveals loss of large-scale antisense intergenic transcripts in both DH and VH regions and reduced expression of key transcription factors required for Igh recombination, including EBF1 and Pax5. Thus, IL-7R signaling promotes Igh repertoire diversity in BM pro-B cells by activating mechanisms that enable large-scale access to VH and DH genes.

Results

Usage of V and D genes in Igh recombination is severely skewed in pro-B cells lacking the IL-7Rα chain

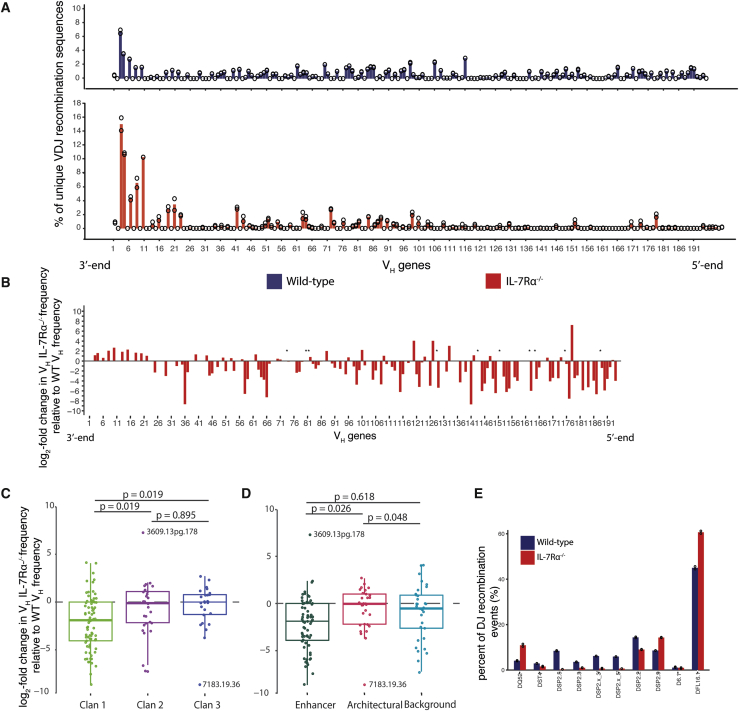

VDJ-seq was performed on two IL-7Rα−/− BM and two wild-type (WT) FL pro-B cell samples and compared with two WT BM datasets we previously generated (GEO: GSE80155; Bolland et al., 2016). Replicate libraries for all genotypes were highly correlated, indicating VDJ-seq is highly reproducible (Figure S1). Although IL-7Rα−/− libraries were generated with approximately 6-fold fewer reads (Figure S2), the ratio of VDJH to DJH recombined products was similar to WT, indicating that dynamic progression through first DH to JH, followed by VH to DJH recombination, was not slowed (Figure S3). A binomial test was applied to determine genes with significantly greater read counts than expected by chance, considered to be actively recombining (Bolland et al., 2016). Consistent with a requirement for IL-7R signaling to enable usage of VH genes in recombination, fewer VH genes passed the binomial test in IL-7Rα−/− (84 genes) relative to WT pro-B cells (128 genes). All but three were within the WT group (Table S1).

To visualize VH gene recombination frequencies and compare between genotypes, VH gene quantifications were normalized to the total number of reads over all VH genes for each genotype (Figure 1A). A much higher proportion of sequences mapped to the most 3′ VH genes in IL-7Rα−/− than in the WT repertoire (Figure 1B). Notably, the first five VH genes comprised 45% of the total repertoire, compared with 20% in WT. Of the 44 VH genes that recombine in WT, but not in IL-7Rα−/− BM, the vast majority were at the 5′ end of the V region, including several that normally recombine at high frequency (J558.16.106, J558.26.116, and J558.67.166).

Figure 1.

IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells have impaired VH and DH repertoires

(A) Recombination frequencies of 195 VH genes measured by VDJ-seq. WT BM pro-B cells (blue) and IL-7Rα−/− (red) are shown. Two biological replicates are shown as open circles (bar height represents average). Reads for each VH gene are shown as percentage of total reads quantified. VH gene number legend is shown in Table S1.

(B) The mean of each VH gene was divided with the WT mean followed by log2 transformation. Only genes recombining in either genotype are shown. ∗ represents VH genes with value 0 in IL-7Rα−/− (only in WT). VH gene raw read counts and recombining/non-recombining classification are shown in Table S1.

(C and D) Log2 values for each gene in graph B (excluding those marked by ∗) were grouped by (C) evolutionary origin: clan 1 (n = 78), clan 2 (n = 27), and clan 3 (n = 26); ANOVA (degrees freedom [Df] = 2; F-value = 5.39; p = 0.005) and (D) chromatin state: enhancer (n = 68), architectural (n = 30), and background (n = 33); ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 4.54; p = 0.012).

(E) Reads for each DH gene as percentage of total reads quantified for two biological replicates of WT (blue) and IL-7Rα−/− (red) pro-B cells.

The 195 VH genes segregate into 16 families in 3 clans (Johnston et al., 2006). Their diverged evolutionary origins correlate with differential TF binding and chromatin state around VH genes (Bolland et al., 2016). Because accessibility, TF expression, and chromatin state have been linked to IL-7R signaling, we investigated the relationship between recombination frequency and VH gene clan or chromatin state in IL-7R−/− pro-B cells. VH genes in clan 1 recombine at lower frequency in the IL-7Rα−/−, although clan 2 and 3 VH genes recombine at similar frequencies to WT (Figure 1C). When the data are broken down to VH gene families, a more nuanced picture emerges. Within clan 2 and 3, 7183 and Q52, the two largest and most 3′ VH families, recombine more frequently in IL-7Rα−/−. However, several of the smaller families in the middle region recombine less frequently (Figure S3). The enhancer state VH genes (including clan 1 and the distal 3609 family from clan 2) were significantly less frequently recombined relative to the architectural state VH genes (clan 2, except 3609, and clan 3; Figure 1D). However, some architectural state VH families also recombined less frequently. Thus, loss of IL-7R impacts on VH genes in the enhancer state (distal and middle genes) and on several middle region families in the architectural state. This distribution also applies to the clans: loss of IL-7R reduces recombination of clan 1 (mostly distal V genes) as well as the middle genes from clans 2 and 3. Importantly, this suggests that the IL-7R does not influence either clans or local chromatin states selectively but rather linear positioning in the Igh V region, i.e., loss of IL-7R impairs recombination of middle and 5′ V genes in the Igh locus.

Actively recombining DH genes were also identified by binomial test. VDJ-seq revealed profound changes in individual DH usage in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells. Several centrally positioned DSP gene segments (DSP2×5′, DSP2×3′, DSP2.3, and DSP2.5) do not recombine in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells (Figure 1E). Conversely, relative recombination frequencies of the most 3′ DH gene, DQ52; the most 5′, DFL16.1; and its adjacent DSP2.9 were increased in IL-7Rα−/− cells.

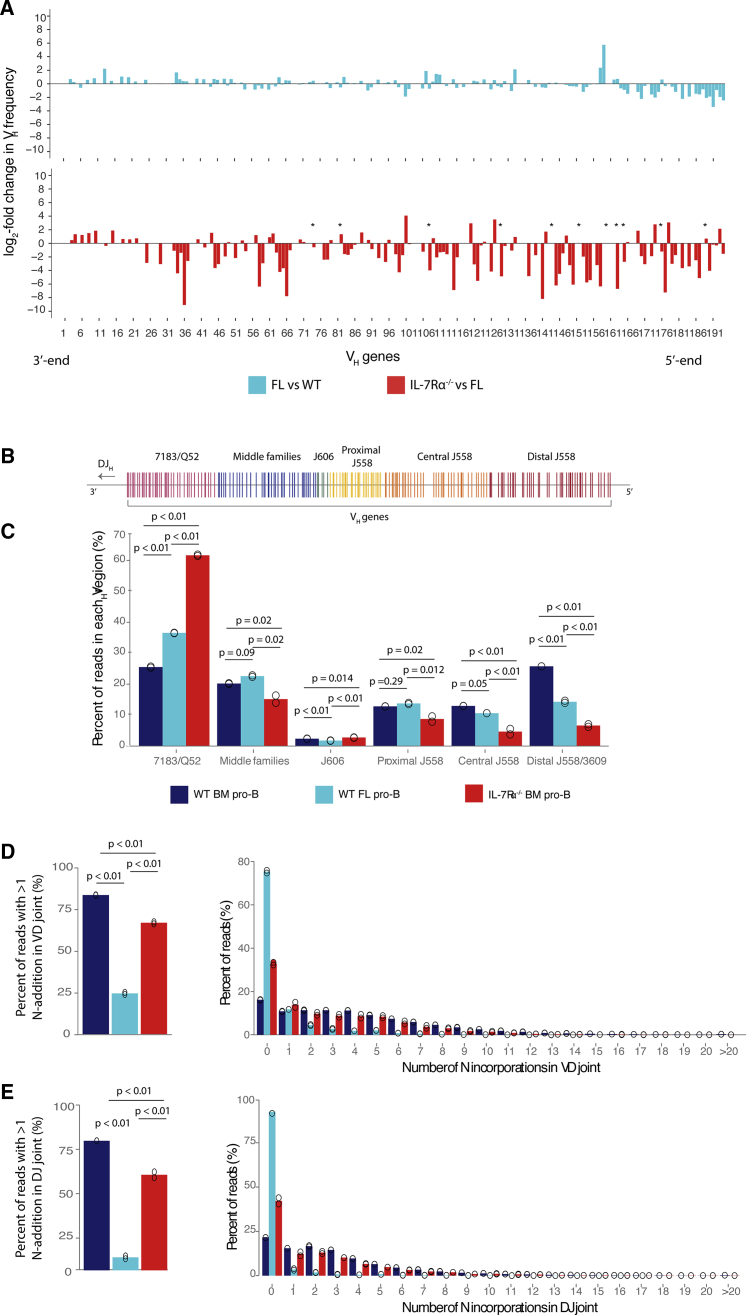

IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells do not originate from the FL

We investigated whether recombination events in IL-7Rα−/− BM were comparable to B cells derived from FL, rather than de novo in the BM. VDJ-seq data from WT embryonic day 15.5 pro-B cells were compared with IL-7Rα−/− and WT BM. Notably, the ratio of DJ to VDJ recombinants in FL was 12:1, in contrast to WT and IL-7Rα−/− BM ratios of approximately 2:1 and 1:1, respectively (Figure S3). Consistent with previous reports, the FL VH gene repertoire exhibited a 3′ bias relative to WT, including more frequent use of the most recombined VH gene, VH-81X (11% compared with 7% for WT BM; Figures 2A and S2C). However, IL-7Rα−/− cells had a more pronounced phenotype, with VH-81X comprising 14% of VDJ recombined sequences. Additionally, many 5′ VH genes recombined less frequently than in FL pro-B cells (Figure 2A). VH usage within Igh VH gene family sub-domains (Figure 2B) is distributed evenly across the locus in WT but is somewhat biased toward the D-proximal 3′ gene families in FL B cells. However, this shift is mild for all but the central and distal J558 genes (Figure 2C). The IL-7Rα−/− repertoire is also biased toward the 7183/Q52 VH family but much more severely than FL B cells. In contrast to FL, this increase in 7183/Q52 VH gene usage was mirrored by a decrease in usage for every other family except the small J606 family. Thus, recombination in IL-7Rα−/− cells is markedly more biased toward the 3′ VH genes than FL, suggesting IL-7Rα−/− BM pro-B cells do not simply originate from FL precursors.

Figure 2.

VH gene use in FL pro-B cells is less restricted than IL-7Rα−/−, and VDJ sequences in IL-7Rα−/− and WT show similar N-incorporations

(A) Average of two WT, two FL, and two IL-7Rα−/− biological replicates calculated for each VH gene. To display changes between WT and FL frequencies, VH frequencies for FL were divided with the WT mean value and log2 transformed (light blue). Only genes active in either genotype are shown. FL and IL-7Rα−/− frequencies are compared (red). ∗ represents VH genes with value 0 in IL-7Rα−/− replicates.

(B) Representation of all VH gene segments, colored by family domains.

(C) Quantified VDJ-seq reads over each VH gene merged for each family domain and calculated as a percent of total quantified reads for WT (dark blue) and IL-7Rα−/− (red) BM pro-B cells and wild-type FL pro-B cells (light blue). Each open circle represents a biological replicate (n = 2). 7185/Q52, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 11,961; p = 0.01); middle families, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 29.4; p = 0.01); J606, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 93.14; p = 0.002); proximal J558, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 26.70; p = 0.012); central J558, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 67.82; p = 0.003); distal J558, ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 917.6; p < 0.001).

(D and E) VDJ-seq libraries analyzed with IMGT to determine number of nucleotides inserted into junctions during VDJ recombination: (D) junction between VH and DH (ANOVA [Df = 2; F-value = 3,578.5; p < 0.001]) and (E) junction between DH and JH gene segments (ANOVA [Df = 2; F-value = 1,037.4; p < 0.001]) of WT (dark blue) and IL-7Rα−/− (red) BM and wild-type FL (light blue) recombination events. Number of sequences with more than 1 N-addition (left) and distribution of sequences with N-additions (right) is shown as percent of all mapped VDJ-seq sequences.

To distinguish whether VDJH sequences in IL-7Rα−/− BM cells are derived from FL or adult BM, we analyzed VDJ-seq libraries with IMGT to compare non-templated (N-) incorporations within VDH and DJH junctions. Terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT), which inserts N-nucleotides, is absent in FL and first expressed in pro-B cells in the BM (Feeney, 1990; Li et al., 1993). Accordingly, we identified very few N-additions in FL junctions; only 25% and 15% had more than one incorporation in the VD and DJ junction, respectively. In contrast, around 80% of VD and DJ junctions in WT BM had N-additions (Figures 2D and 2E). 60% of VD and DJ joins from IL-7Rα−/− cells also had N-additions. IL-7Rα−/− and WT sequences also had a similar distribution, including up to 10 additions (Figures 2D and 2E). Together, these data demonstrate that IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells undergo V(D)J recombination de novo in the BM, but loss of the IL-7Rα severely restricts usage of VH and DH genes in the formation of the primary Igh repertoire.

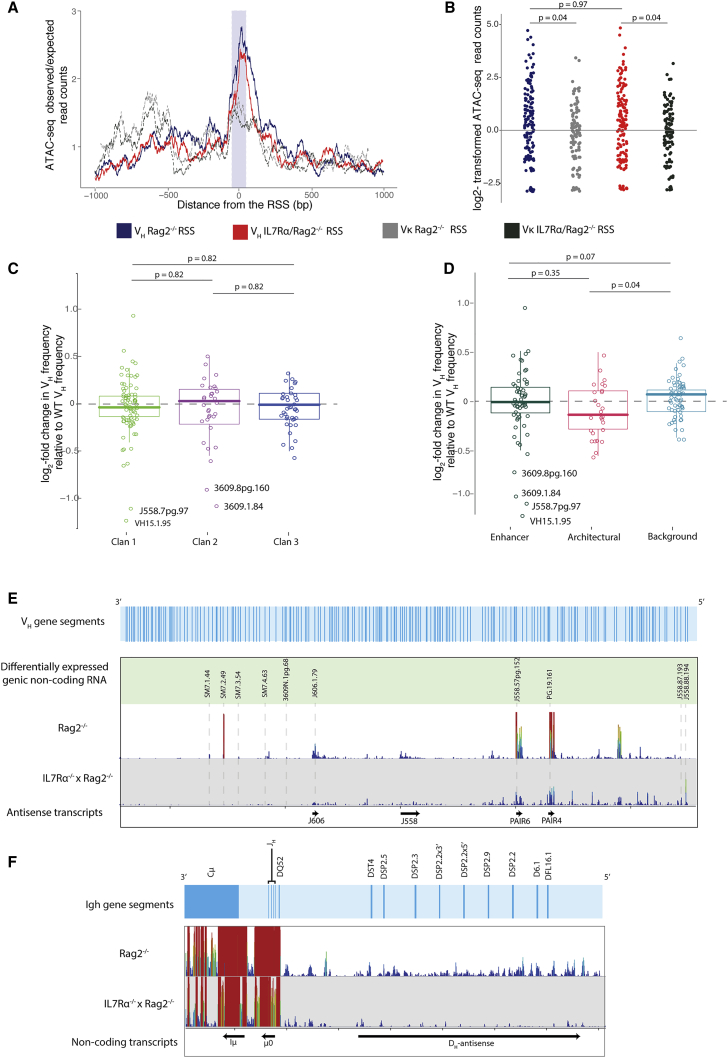

IL-7R signaling does not influence local V gene chromatin state

We next investigated how IL-7R signaling may regulate V(D)J recombination. Reduction in recombination of 5′ VH genes in IL-7Rα−/− BM, together with normal DJ/VDJ ratios, suggests that signaling through IL-7R is specifically required for 5′ VH gene recombination. We first asked whether altered Recombination Signal Sequence (RSS) accessibility could account for this reduced recombination, because the local enhancer chromatin state is predominantly associated with 5′ VH genes (Bolland et al., 2016). We performed ATAC-seq to identify accessible DNA in a chromatin context (Pulivarthy et al., 2016). We performed these experiments in Rag recombinase-deficient models, which cannot recombine Ig loci, thereby enabling analysis of the intact, poised Igh locus and avoiding interference from loss of sequence, or elevated VH gene expression, due to recombination. We compared Rag2−/− pro-B cells (which express the endogenous IL-7R) with IL-7Rα−/− × Rag2−/− (referred to as IL-7Rα/Rag2−/−) BM. Duplicate libraries for both genotypes were highly correlated, indicating the data are highly reproducible (Figure S1).

In Rag2−/− pro-B cells, VH RSSs coincided with a peak of accessibility (Figure 3A). VH RSSs in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells had a similar highly accessible profile, suggesting IL-7R signaling does not activate local accessibility over VH RSSs. The Igκ light chain V gene (Vκ) RSSs were used as a negative control because the Igκ locus does not become fully activated until the pre-B stage (Matheson et al., 2017). Accordingly, Vκ RSSs were less accessible than VH RSSs (Figures 3A and 3B). Notably, this pattern was similar in Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells, suggesting that Igκ Vκ genes are not activated prematurely in the absence of the IL-7Rα.

Figure 3.

IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells show no significant changes in RSS accessibility but striking loss of non-coding transcription over the Igh locus

(A) Accessibility over the VH and Vκ RSSs in Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells. Accessibility tracks over a 1,000-bp region centered on the RSS. ATAC-seq reads were quantified over each bp. Each track is an average for all Rag2−/− VH (blue) and Vκ (dotted gray) RSSs and IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− VH RSSs (red) and Vκ (dotted black). Purple area represents the RSS.

(B) ATAC-seq reads over a 50-bp region over VH (n = 195) and Vκ (n = 162) RSS for Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα/Rag2−/−. ANOVA (Df = 3; F-value = 3.68; p = 0.012).

(C and D) Differential expression for each RSS calculated by DESeq2 was grouped by (C) evolutionary origin: clan 1 (n = 78), clan 2 (n = 27), and clan 3 (n = 26); ANOVA (Df = 2; F-value = 0.27; p = 0.77) and (D) chromatin state: enhancer (n = 68), architectural (n = 30), and background (n = 33); Kruskal-Wallis test (Df = 2; chi-square = 7.51; p = 0.023) plus pairwise Wilcox test (adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg method) to calculate p value.

(E and F) RNA-seq reads for Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− were quantified per 60-bp bins along the Igh locus and normalized by rpm. Height and color of bars represent number of reads over each probe: high red bars have more reads than short blue bars. Each track was generated from average of two biological replicate RNA-seq libraries.

(E) Transcription over the VH region. Top light blue track: location of all VH genes is shown. Transcription over ten significantly differentially expressed VH genes (Table S2) in green track (gray dotted line marks their location) is shown; locations of antisense intragenic non-coding transcripts are shown as black arrows.

(F) Transcription over DH, JH and CH regions. Gene locations are shown in light blue track. Intergenic non-coding transcripts, black arrows.

We divided the RSSs into clans and chromatin states to test whether these groups showed different accessibility patterns in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/−. There was no significant difference between clans (Figure 3C). RSS accessibility in both enhancer and architectural groups was significantly reduced compared to the background state VH genes, which showed a small increase in RSS accessibility relative to WT (Figure 3D). Together, these data indicate little difference in local accessibility at recombining VH genes in the absence of the IL-7Rα.

Igh antisense intergenic transcription, but not VH genic transcription, is impaired in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells

Non-coding transcription has been proposed to promote chromatin accessibility to facilitate Igh VH gene recombination. The Igh VH region has short non-coding genic sense transcripts at VH promoters (Yancopoulos and Alt, 1985; Corcoran et al., 1998) and long intergenic antisense transcripts (Bolland et al., 2004, 2016; Verma-Gaur et al., 2012). To investigate changes in the absence of IL-7R signaling, we performed RNA-seq (Figures S1G–S1I). This revealed that there is generally little VH genic transcription over the 3′ V genes; 31 of the 39 most D-proximal V genes showed no transcription in Rag2−/− pro-B cells. Very few non-coding VH genic transcripts were differentially expressed between IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− cells (Table S2). Notable exceptions included all four members of the middle region SM7 family, highly abundant in Rag2−/− but almost completely absent in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells. Conversely, two of the most 5′ VH genes, J558.88.194 and J558.87.193, not transcribed in Rag2−/− pro-B cells, are highly expressed in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells (Figure 3E). Long intergenic antisense non-coding transcripts in the VH (Pax5-activated intergenic repeat 4 [PAIR4], PAIR6, J558, and J606) and DJH regions (Iμ, μ0, and DH-antisense) were also analyzed. Although the RNA-seq libraries were not strand specific, these known transcripts are easily distinguished from the much less frequently transcribed genic transcripts in Rag2−/− pro-B cells (Figure 3E). Strikingly, antisense transcription throughout the VH region was almost completely absent in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells. DESeq2 revealed significant reduction in all VH antisense transcripts tested (Table S2). Furthermore, although sense transcription over the JH (μ0) or the CH (Iμ) transcript regions was relatively unchanged (Table S2), DH antisense transcription was almost completely lost over the entire DJH region in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells (Figure 3F).

EBF1, PAX5, and other key B-cell-lineage-specifying genes are mis-regulated in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells

We next examined genome-wide alterations in gene expression in the absence of the IL-7R (Figure S4). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) confirmed the essential role of IL-7R signaling in cell cycle and clonal expansion as genes related to E2F, G2M checkpoint, and MYC were downregulated in the IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells (Figures S4B–S4D). Consistent with previous reports, expression of both Ebf1 and Pax5 was substantially reduced in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells (Table S3). Importantly, several key B-lineage genes regulated by Ebf1 and Pax5 had reduced transcription levels in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells, including Foxo1, Rag1, and Cd79a (coding for Igα, pre-B cell receptor complex), downregulated in EBF1-deficient cells (Györy et al., 2012). PAX5-activated genes, including Smarca4 (encoding BRG1) and Lef1, were also decreased. Conversely, FLT3R (Flt3), downregulated in pro-B cells by PAX5 (Pridans et al., 2008), was upregulated in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells. GSEA demonstrated that, overall, genes with PAX5 binding sites at their promoters were depleted in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells (Figure S4E). However, some B-cell-specific genes regulated by PAX5 and EBF1 were expressed normally: Irf4 (direct target of both), Myb, and Pdcd1 (activated and repressed by EBF1) showed no significant transcriptional changes in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells. Indeed, Irf8 and Ikzf3 (Aiolos), activated by both, were more highly expressed in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells. Together, these results suggest that EBF1 and PAX5 function is mis-regulated in IL-7Rα−/− cells.

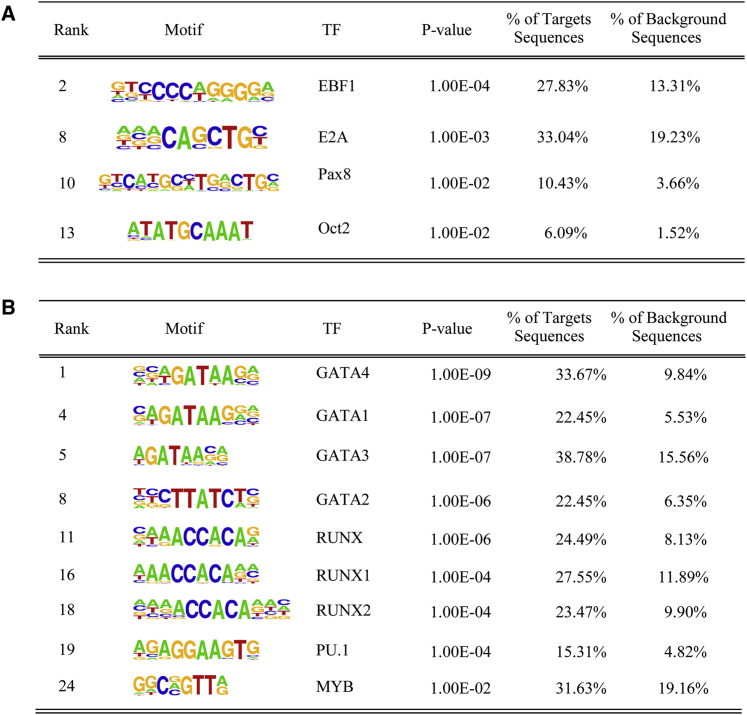

To determine whether IL-7R signaling additionally influences the binding pattern of these and other TFs, we compared accessible hypersensitivity sites with ATAC-seq, using the Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) caller (Zhang et al., 2008) function in Seqmonk. We divided the sites into two groups: those that had fewer reads (less accessible) or more reads (more accessible) in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− than Rag2−/− cells. We used hypergeometric optimization of motif enrichment (HOMER) to identify TF motifs within these sites. This allowed us to infer TFs that bind less often (less accessible sites) in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− relative to Rag2−/− and vice versa. EBF1 bound less often in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells, correlating with reduction in its expression and that of its target genes. The PAX5 motif was not found in HOMER. We infer that the PAX8 motif, with a similar binding pattern, is PAX5, because PAX8 is not expressed in B cells. Again, we found reduced representation of this motif in ATAC-seq-accessible sites in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

TF motif analysis at genomic sites of altered accessibility

Peaks identified from ATAC-seq by MACS peak calling from two biological replicates.

(A) Sites less accessible in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− analyzed using DESeq2. TF motif enrichment using HOMER is shown. Relevant significantly enriched motifs are shown in order of significance (rank indicated their position in the list).

(B) The same analysis as in (A) for peaks that were more accessible in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/−.

To further interrogate the differences in PAX5 and EBF1 binding in the Igh locus, we examined MACS peaks in published PAX5 (GSM932924) and EBF1 (GSM876622 and GSM876623) chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data in Rag−/− pro-B cells. We quantified ATAC-seq reads over these sites to infer TF binding differences between IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− cells. Of 24 accessible sites in the Igh locus (not counting RSSs), all overlapped with one of the 34 PAX5 binding sites. Five showed a marked decrease in accessibility in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells (Table S3). Importantly, two of these sites correspond to the PAIR4 and PAIR6 PAX5 binding sites (Figure S4I), providing a mechanism for the loss of non-coding transcription above. We only detected three EBF1 binding sites in the Igh locus, with no difference in accessibility. However, quantification of ATAC-seq reads over 2,896 EBF1 binding sites genome-wide revealed 643 significantly differentially enriched sites. 630 had lower accessibility in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells (Table S4). In the HOMER analysis, we also detected reduced accessibility at motifs of other important TFs involved in B cell specification, including E2A. Reduced specification was reflected in TF motifs at more accessible sites in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells, which included T cell development motifs (GATA family TFs) and early B cell priming TFs, including PU.1, MYB, and RUNX (Figure 4B). Furthermore, GSEA analysis showed that genes with binding sites for GATA, LIM domain only 2 (LMO2), and NFE2 (TFs in T- and erythroid development) were enriched in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− pro-B cells (Figures S4F–S4H). Overall, the pattern of TF motif accessibility and target gene alteration suggests that the IL-7Rα enforces commitment to the B cell lineage.

Discussion

Here, we asked whether and how the IL-7R plays a role in de novo immunoglobulin gene recombination in BM B cells. As previously reported (Jeong and Teale, 1988; Yancopoulos et al., 1988), we found that FL pro-B cells had a bias toward usage of 3′ VH genes. However, the FL B cell antibody repertoire was far less restricted than previously thought, suggesting the current model of B cell ontogeny, in which complex antibody repertoires do not develop until after birth warrants revisiting (Siegrist and Aspinall 2009). It will be important to investigate which mechanisms that underpin adult Igh repertoire formation are already in place in FL, including long-range looping and local V gene activation, dependent on CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and PAX5 (Gerasimova et al., 2015; Bolland et al., 2016; Jain et al., 2018). Because PAX5 is essential for FL Igh recombination (Nutt et al., 1997), it may play similar roles in FL B cells.

Our unprecedented depth of analysis of IL-7Rα−/− VDJH and DJH sequences demonstrates that BM pro-B cells lacking the IL-7Rα−/− display widespread defects at both stages of Igh recombination. Most importantly, the VH repertoire was highly biased toward 3′ VH genes. Reduced use of 5′ VH genes was much more pronounced than in FL pro-B cells, indicating that IL-7R signaling is specifically needed in the BM to make all VH genes available for the primary antibody repertoire. The presence of N-additions within IL-7Rα−/− VDJH sequences demonstrates that they are derived from BM, not FL, progenitors. Our findings concur with a study in neonatal IL-7Rα−/− BM (Hesslein et al., 2006). Detection of N-additions at DH-JH junctions indicated that DH to JH recombination also took place de novo in the BM. Thus, V(D)J recombination progressed with normal dynamics but severely restricted participation of both VH and DH genes. Previous models of a block in B cell development in IL-7Rα−/− BM (Kikuchi et al., 2005; Peschon et al., 1994; Miller et al., 2002; Carvalho et al., 2001) inferred that IL-7Rα−/− BM B cells had originated in the FL, where the IL-7R is not essential (Erlandsson et al., 2004), due to their restricted Vh gene usage. Here, our demonstration that V(D)J recombination occurs de novo in the BM, albeit in the very few remaining B cells, has enabled us to uncover specific roles of the IL-7R in regulating DH and VH gene usage in the Igh repertoire in BM pro-B cells.

A previous study showing that IL-7Rα−/− B cell development could be partially rescued by a vav-cre bcl2 transgene, indicating a crucial role in CLP survival (Malin et al., 2010), suggested that IL-7R signaling is not required for BM B cell recombination. However, Bcl2 driven by the Igh Eμ enhancer did not rescue B cell development (Maraskovsky et al., 1998), indicating that the IL-7R has important functions beyond survival, in pro-B cells where V(D)J recombination is taking place. Here, we show that these functions include making the Igh locus accessible for V(D)J recombination.

Furthermore, we have uncovered mechanisms underpinning impaired recombination of VH genes. It must be noted that we performed RNA- and ATAC-seq on a Rag2−/− background. Although an established model for studying mechanisms underpinning recombination because the Igh locus remains in an intact, poised state, it has the caveat that DH to JH recombination, which normally affects locus structure and V region accessibility, has not occurred. Nevertheless, several marks of V region accessibility are acquired, against which we measured the effect of IL-7R loss. There were no significant differences in local chromatin accessibility over VH gene RSSs in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− cells. Importantly, low accessibility at Vκ gene RSSs suggests that surviving IL-7Rα−/− B cells have not “rushed through” to the IL-7R-independent pre-B cell stage where increased Vκ access occurs. IL-7R signaling must be downregulated to enable Igκ recombination (Johnson et al., 2008; Mandal et al., 2011). Here, loss of the IL-7R is not sufficient to activate Vκ genes, suggesting that additional mechanisms are at play (Mandal et al., 2019). Overall, we find no evidence that defects in local accessibility at 5′ V genes account for the preference for recombination of 3′ VH genes in IL-7Rα−/− cells. We also found that VH genic non-coding transcription rarely changed in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells, supporting multiomics studies that found no correlation with VH usage (Choi et al., 2013; Bolland et al., 2016).

Non-coding intergenic transcription activates T cell receptor α (TCRα) locus recombination in vivo (Abarrategui and Krangel, 2006), although de novo antisense transcription over Igh 3′ VH genes increases their recombination (Guo et al., 2011). These and other findings support a model in which intergenic transcription drives recombination (Corcoran, 2010). Here, widespread loss of all PAX5-dependent (PAIRs 4 and 6) and PAX5-independent (J558 and J606) antisense intergenic transcripts (Bolland et al., 2004, 2016; Ebert et al., 2011; Verma-Gaur et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2013) suggests that the IL-7R regulates all Igh antisense transcription and supports a role in promoting long-range mechanisms underpinning VH to DH recombination. We did not observe de novo antisense transcription over 3′ VH genes in IL-7Rα−/− pro-B cells, indicating the relative increase in 3′ VH gene recombination is secondary to the defect in 5′ recombination rather than a bona fide increase in 3′ recombination (Guo et al., 2011).

PAX5, downregulated in IL-7Rα−/− cells, is essential for Igh locus contraction (Fuxa et al., 2004; Nutt et al., 1997; Hesslein et al., 2003; Medvedovic et al., 2013; Montefiori et al., 2016). PAX5 has pleiotropic functions, but here, reduced accessibility at Pax5 sites on PAIR promoters and downregulation of PAX5-dependent PAIR transcription in the Igh locus suggests that PAX5 binding and function at these regulatory regions is directly impaired by loss of the IL-7R (Ebert et al., 2011).

A key finding was that DH to JH recombination is also impaired in IL-7Rα−/− BM B cells. Representation of the central DSP family was severely reduced. Strikingly, antisense non-coding transcription over the DH region was also ablated. These findings support our model that antisense transcription over the DSP genes activates their recombination (Bolland et al., 2007) and reveal a role for the IL-7R in activating this transcription to drive DH to JH recombination.

Reduced accessibility at hundreds of EBF1 binding sites and reduced expression of multiple Pax5 targets by GSEA suggests specific functional consequences of reduced EBF1 and Pax5 expression. Conversely, increased accessibility at putative T cell TF motifs suggests that, although IL-7Rα−/− B cells are committed to the B cell lineage, they nevertheless remain plastic, similarly to PAX5−/− B cells (Nutt et al., 1999).

Our findings have important implications for human B cell development. Pediatric studies suggested early human B cell development did not require IL-7 (LeBien, 2000), but recent studies have shown that adult B cell development is dependent on IL-7R signaling, thereby aligning the dynamics of mouse and human IL-7R dependency (Parrish et al., 2009; Milford et al., 2016). It will be important to determine whether the IL-7R regulates immunoglobulin recombination in human B cells. Human immunodeficiency diseases and aging both have restricted antibody repertoires and poor response to infection (Siegrist and Aspinall, 2009; Martin et al., 2015). Notably, both Igh recombination and IL-7R signaling are impaired in aging mice (Stephan et al., 1997; Szabo et al., 1999) and humans. The therapeutic potential of the IL-7R in human aging is an emerging area of interest (Passtoors et al., 2015), and our findings suggest therapeutic potential of IL-7 for boosting naive antibody repertoires.

In conclusion, we reveal that, in addition to its roles in pro-B cell survival and proliferation, IL-7R signaling shapes the Igh repertoire at both the DH-to-JH and VH-to-DJH stages of recombination in mouse BM and identify several mechanisms by which it can activate the Igh locus. IL-7R signaling is therefore essential for expanding antibody diversity to ensure robust activation of the adaptive immune system.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CD11b Monoclonal Antibody, Biotin | eBioscience | Clone M1/70; Cat# 13-0112-82; RRID:AB_466359 |

| Ly-6G/Gr-1 Monoclonal Antibody, Biotin | eBioscience | Clone RB6-8C5; Cat# 13-5931-82; RRID: AB_466800 |

| RAT ANTI MOUSE Ly-6C:Biotin | AbD Serotec | Clone ER-MP20 Cat# MCA2389B RRID: AB_844550 |

| TER-119 Monoclonal Antibody, Biotin | eBioscience | Clone TER-119 Cat# 13-5921-82 RRID: AB_466797 |

| CD3e Monoclonal Antibody, Biotin | eBioscience | Clone 145-2C11 Cat# 13-0031-82 RRID: AB_466319 |

| BV421 Rat Anti-Mouse CD45R/B220 | BD bioscience | Clone RA3-6B2 Cat# 562922 RRID: AB_2737894 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 Rat Anti-Mouse CD19 | BD bioscience | Clone 1D3 Cat# 561113 RRID: AB_10563071 |

| FITC Rat Anti-Mouse CD43 | BD bioscience | Clone S7 Cat# 553270 RRID: AB_394747 |

| Chemicals, peptides and recombinant proteins | ||

| Agencourt AMPure XP beads | Beckman | Cat# A63880 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Ovation RNA-seq SystemV2 kit | NuGen | Cat# 7102-08 |

| TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 | Illumina | Cat# RS-122-2001 |

| Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit | Illumina | Cat# 15028211 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE157603 |

| PAX5 ChIP Rag−/− pro-B | Revilla-I-Domingo et al., 2012 | GEO: GSM932924 |

| EBF1 ChIP Rag−/− pro-B | Vilagos et al., 2012 | GEO: GSM876622, GSM876623 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: IL7Rα−/− | J.J. Peschon | Peschon et al., 1994 |

| Mouse: RAG2−/− | Frederick Alt | Shinkai et al., 1992 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| Seqmonk | The Babraham Institute | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/seqmonk/ |

| DESeq2 | Love et al., 2014 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| LinkON | The Babraham Institute Chovanec et al., 2018 | https://github.com/peterch405/BabrahamLinkON/blob/master/README.md |

| HOMER | Heinz et al., 2010 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ngs/peaks.html |

| IMGT | Lefranc et al., 2015 | http://www.imgt.org/ |

| GSEA4.1 | Subramanian et al., 2005 | http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Anne Corcoran (anne.corcoran@babraham.ac.uk).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The VDJ-seq, ATAC-seq and RNA-seq raw sequencing files generated in this study, as well as processed files have been deposited at GEO, and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the Key resources table. This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the Key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Wild-type, RAG2−/− (Shinkai et al., 1992), IL-7Rα−/− (Peschon et al., 1994) and IL-7Rα−/− crossed with RAG2−/− (IL-7Rα−/− x RAG2−/−) C57BL/6 mice were maintained in accordance with Babraham Institute Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body and Home Office rules under Project License 80/2529. Recommended ARRIVE reporting guidelines were followed. Mice were bred and maintained in the Babraham Institute Biological Services Unit under Specific Opportunistic Pathogen Free (SOPF) conditions. After weaning, mice were maintained in individually ventilated cages (2–5 mice per cage). Mice were fed CRM (P) VP diet (Special Diet Services) ad libitum, and millet, sunflower or poppy seeds at cage-cleaning as environmental enrichment. Health status was monitored closely and any mouse with clinical signs of ill-health or distress persisting for more than three days was culled. Treatment with antibiotics was not permitted to avoid interference with immune function. Thus, all mice remained ‘sub-threshold’ under UK Home Office severity categorization. 6-8-week-old IL-7Rα−/− and IL-7Rα−/− x RAG2−/− mice (all mixed sex), and 10-12 week old RAG2−/− mice (one female replicate and one male replicate) were used. Although wild-type (WT) comparison data were from 12 week old mice, IL-7Rα−/− animals were taken before 10 weeks because they produce fewer BM B cells as they age, with very few produced after 10 weeks (Peschon et al., 1994; Erlandsson et al., 2004). To maximize cell numbers and considering IL-7Rα−/− mice as young as 3 weeks have adult B cell populations (Hesslein et al., 2006), pro-B cells from 6-8-week old mice were taken for sorting. Fetal livers (FL) were harvested from day 15.5 mouse embryos.

Method details

Primary cells

Following CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation, mouse BM was flushed from femurs and tibias, resuspended at 25 × 106 cells/ml, and depleted of macrophages, granulocytes, erythroid lineage and T cells using biotinylated antibodies against CD11b (MAC-1; ebioscience; 1:1600), Ly6G (Gr-1; ebioscience; 1:1600), Ly6C (Abd Serotec; 1:400), Ter119 (ebioscience; 1:400) and CD3e (ebioscience; 1:800), incubated on ice for 30 mins, followed by streptavidin MACs beads (10 μl/107 cells in 100 μl) (Miltenyi) at 4°C for 15 mins. MACS LS columns were equilibrated and the flow through collected for flow sorting. MACS depletion for FL was carried out as for BM, using TER119-biotin at a higher concentration (1:200). Cells were stained for 45 mins on ice in the dark with the following sorting antibodies from BD Bioscience: BV421-anti B220,1:200; PerCP-Cy5.5-antiCD19, 1:400; FITC-anti CD43, 1:200) Thereafter, pro-B cells from IL-7Rα−/− BM and WT FL were flow-sorted for forward and side scatter and cell surface markers as B220+ CD19+, while IL-7Rα−/− x RAG2−/− and RAG2−/− BM B pro-B cells were sorted as a B220+ CD19+ CD43+ population on a BD FACSAria in the Babraham Institute Flow Cytometry facility.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse B cells using the DNeasy kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except for the incubation step, which was changed to 30 mins. DNA was eluted in nuclease-free water and quantified by Nanodrop.

RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from ~200,000 cells for each replicate using the RNeasy Plus kit (QIAGEN). cDNA preparation was performed using the Ovation RNaseq System V2 kit (NuGen) protocol, and 200 ng of cDNA (made up to 130 μL with nuclease-free water) was carried through to generate 50bp paired-end RNA-seq libraries for Illumina sequencing. cDNA was sonicated using a Covaris E220 to fragment lengths between 200-700 bp (10% duty cycle, 140W peak incident power, 200 cycles per burst, 80 s processing time). End repair was carried out by adding 16 μL of 10x T4 Ligase Buffer (NEB), 4 μL of 10 mM dNTP mix, 3 μL T4 DNA polymerase (5 U/μl, Invitrogen), 1 μL Klenow (2U/μl, Invitrogen), 1 μL T4 polynucleotide kinase (10 U/μl, NEB) and 3 μL nuclease-free water, and incubating the reaction for 30 min at 20°C. Samples were purified again using QIAquick columns and eluted in 43 μL of nuclease-free water. A-tailing was then performed by adding 5 μL of 10x Klenow Buffer (NEB), 1 μL of dATP (10 mM) and 1 μL of exo minus Klenow (5U/μl, Fermentas); the reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and purified using MinElute PCR purification columns (QIAGEN) and cDNA eluted in 10 μl. To sequence multiple libraries in one lane, Illumina TruSeq adaptors (6 bp index) (TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2) were ligated by adding 15 μL 2x Rapid Ligation Buffer (Enzymatics), 4 μL of Rapid T4 DNA Ligase (6U/μl, Enzymatics) and 1 μL of adaptor mix (indexed adaptor and universal adaptor at 1.5 uM each) to the 10 μL of eluted cDNA. This reaction was incubated at 23°C for 30 min and 15°C for 30 min. Agencourt AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) were used to select library fragments between 200-700 bp by performing double-sided SPRI bead selection. Amplification was performed as follows: a 50 μL reaction was set up by adding 5ul of 10x Pfx amplification buffer (Invitrogen), 0.8 μL Pfx Platinum (2.5 U/μl), 2 μL of dNTPs (10 mM each), 2 μL MgSO4 (50 mM) and 1 μL of each Illumina paired-end primer (25 uM, Sigma) to the 38.2 μL library. Program: 94°C for 2 min, 8-11 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 62°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, and a final 10 min at 72°C. The library was purified by single-sided SPRI selection as above (modified from Parkhomchuk et al., [2009]). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500 (4 libraries per lane).

VDJ-seq

VDJ-seq was carried out as previously described in Bolland et al. (2016). 1-5 μg of DNA was sonicated using a Covaris E220, to get an average length of 500 bp. End repair was carried out by adding 16 μL 10x T4 DNA ligas buffer (NRB), 4 μL dNTP mix (10 mM total each - dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 5 μL T4 DNA polymerase (3U/μl, NEB), 1 μL Klenow (5 U/μl, NEB) and 5 μL T4 PNK (10 U/μl, NEB) to the sonicated DNA (161 μL reaction), and incubating it at room temperature for 30 min. The sample was purified following the QIAquick PCR purification column protocol (QIAGEN). Repaired DNA fragments were eluted in 50 μL of nuclease-free water, and A-tailing was then carried out by adding 6 μL of 10x buffer 2 (NEB), 1 μL dATP (10 nM) and 3 μL Klenow exo- (5U/μl, NEB), and incubating the mix at 37°C for 30 min. DNA was purified using QIAquick PCR columns again. Two altered PE1 adaptor mixes were used, both including 6 random nucleotide barcodes. For the latter reaction, the A-tailed samples were split in two, each ligating to one of the two adaptor mixes. Adaptor ligation was carried out by adding 6 μL 10x T4 DNA ligase buffer (NEB), 4 μL adaptor (50 μM) and 5 μL T4 DNA ligase (400,000 U/ml, NEB) to each sample, making a 60 μL reaction. Reactions were incubated at 16°C overnight. The split reactions were pooled after incubation, and QIAquick columns were again used for purification. Depletion of unrecombined sequences was achieved by the use of 4 pairs of biotinylated primers (Bolland et al., 2016) which target the intergenic region upstream of each JH gene. Each sample was split so that each aliquot was < 1 μg of DNA in 50 μL containing 5 μL 10x ThermoPol reaction buffer (Roche), 2 μL dNTP (10 mM each) and 1 μL Vent exo- (200U/ml, NEB). Incubation: 95°C- 4 min, 55°C- 5 min, 72°C- 15 min. Reactions for each sample were pooled and purified using QIAquick columns. Unrecobined JH sequences were removed from the samples using streptavidin magnetic beads (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1, Invitrogen) and samples were purified using QIAquick columns. To enrich for recombined sequences, primer extension was carried out as above (annealing temperature 59°C rather than 55°C) using biotinylated reverse primers for each of the four JH genes. Recombined sequences were recovered using streptavidin beads as above. Beads were washed twice using 100 μL of washing buffer and once with EB buffer, and resuspended in 42 μL of EB buffer. To amplify the library, a PE1 primer (Illumina) and a mix of four JH primers which included a PE2 adaptor sequence (Bolland et at., 2016), were used. The resuspended beads were split into four aliquots (10.5 μL each) and 12.5 μL Pwo master mix (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μL PE1 primer (10 μM) and 1 μL JH reverse primer mix (10 μM) were added to make a 25 μL reaction. Incubation: 94°C- 2 min, 15 cycles of 94°C- 15 s, 61°C-30 s, 72°C- 45 s, followed by a final 72°C- 5 min. The sample was pooled again, and beads were washed using 30 μL EB (QIAGEN), which was added to the supernatant containing the amplified library. These were put through a double-sided selection using Ampure XP beads (Bekman Coulter) for 200-700 bp. The library was further amplified to incorporate flowcell-binding indexes. PE1 and PE2 (including the index) primers (Illumina) were added to a PCR reaction as described above but with only 5 cycles and an annealing temperature of 55°C, rather than 61°C. PCR products were combined and purified using SPRI beads, eluting in 20 μl.

Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq (8-12 libraries/lane; 250 BP paired-end). Due to the low number of cells in IL-7Rα−/− BM, VDJ-seq libraries were generated with approximately 6-fold less starting material, resulting in reduced numbers of sequences relative to the WT BM VDJ-seq libraries (Table S7). Nevertheless, this amount of starting material does not compromise detection of the wide dynamic range of frequency of VDJ and DJ recombined sequences (Chovanec et al., 2018).

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) was performed as previously described (Buenrostro et al., 2013, 2015) on 70,000-100,000 cells. Sorted cells were washed, centrifuged, and resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP40) on ice for 15 min. Nuclei were centrifuged at 600 rcf. for 10 min at 4°C, resuspended in 50 μl 1xTD buffer containing 2.5 μl TDE1 transposase (Illumina Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit), and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were purified using MiniElute columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in 21 μl RSB buffer (10mM Tris HCl pH7.6, 10mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP40). PCR amplification and index incorporation were performed in a 50 μl reaction containing 5 μl of forward and reverse index primers (Illumina Nextera Index Kit), 15 μl NPM, 5 μl PPC (Illumina Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit) and 20 μl DNA. Libraries were purified using QIAquick PCR clean-up columns (QIAGEN) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq (6 libraries/lane).

Quantification and statistical analysis

RNA-seq reads were mapped to the mouse genome build NCBI37/mm9 using Bowtie2 and quantified using Seqmonk (Babraham Bioinformatics; https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/seqmonk/). Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), using all annotated genes, VH genic transcripts and intergenic transcripts in a single analysis. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using GSEA 4.1 (Subramanian et al., 2005). Mouse gene names were converted to human gene symbols, and ran with default parameters for genes with BaseMean > = 5. The Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene sets and the transcription factor targets/regulatory target were used to perform pathway enrichment analysis limiting the output to the top 1000 gene sets.

For VDJ-seq, reads were mapped to the mouse genome build NCBI37/mm9 using Bowtie2. To quantify individual V and D genes, probes were created over each gene segment and correctly orientated reads were quantified over each probe using Seqmonk. Libraries were also analyzed using IMGT (International ImMunoGeneTics information system – http://www.imgt.org/ Lefranc et al., 2015). Analysis of VDJ-recombined sequences was carried out as described previously (Bolland et al., 2016); however, to analyze DJ-recombined sequences using IMGT, it was necessary to artificially add a VH gene 5′ of the DH sequence, as IMGT/HighVQUEST can only process VDJ sequences. The J558.78.182 VH gene was appended, as it is functional and in-frame. These data were kept separate, and only DH genes and the DJH junction were used for the analysis.

Due to the expectation for less variable VDJ events in IL-7Rα−/− cells, measures were taken to distinguish and discount technical duplicates in VDJ-seq libraries. VDJ-seq libraries were de-duplicated based on the sequence of read 2 (containing both VH-DJH and DH-JH junctions) and the sequence and position of the VH gene (LinkON pipeline described in Bolland et al. (2016). This method relies on the variability of gene usage, junction diversity, and the sonication step; therefore, reduced variability in the junctions and in VH usage would lead to sequences being more likely to be identical, particularly in partially (DH-JH) recombined alleles. To overcome this issue, modified PE1 adaptors containing random barcodes were used to generate the IL-7Rα−/− and FL libraries, allowing PCR duplicates, biological duplicates and Illumina sequencing errors to be distinguished (Chovanec et al., 2018).

ATAC-seq reads were mapped to the mouse genome build NCBI37/mm9 using Bowtie2 and quantified using the MACS peak caller within Seqmonk. DESeq2 was used to identify genomic locations exhibiting significant differences in ATAC-seq reads in IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− relative to Rag2−/−, and these sites were tested for TF motifs using the HOMER analysis tool (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ngs/peaks.html - Heinz et al., 2010).

ChIP reads were mapped using Bowtie and peaks called using MACS2 (in the narrow peak mode): PAX5 Rag−/− pro-B (GSM932924) and EBF1 Rag−/− pro-B (GSM876622, GSM876623).

For calculating statistical significance between groups for the above datasets, a two-tailed ANOVA (type III) together with a pairwise t test (adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg method) were used to calculate significance and p values (significant when > 0.05) when data were normal. When data failed the normality test a Kruskal-Wallis test (followed by pairwise Wilcox test (adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg method) was performed. All results for specific tests are explained in the figure legends, including the statistical test used, value and meaning of n, and confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoff Butcher, Martin Turner, and members of the Corcoran lab for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Mark Veldhoen for provision of IL-7Rα/Rag2−/− mice. We thank Flow Cytometry and Biological Services Unit for excellent support. Work in our laboratory is supported by grants from the BBSRC (BBS/E/B/000C0404, BBS/E/B/000C0405, BBS/E/B/000C0427, BBS/E/B/000C0428, and Core Capability Grant), A.B.-E. was supported by an MRC PhD studentship (1236141), B.A.S. was supported by an MRC PhD studentship (1129229), and M.J.T.S. was supported by a Babraham Institute PhD studentship.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.-E., B.A.S., and A.E.C.; methodology, A.B.-E., B.A.S., and D.J.B.; software, B.A.S., M.J.T.S., and S.A.; validation, A.B.-E. and A.E.C.; formal analysis, A.B.-E., B.A.S., M.J.T.S., and S.A.; investigation, A.B.-E. and B.A.S.; resources, A.B.-E., K.T., and A.E.C.; data curation, A.B.-E. and B.A.S.; writing – original draft, A.B.-E. and A.E.C.; writing – review and editing, A.B.-E., B.A.S., M.J.T.S., D.J.B., S.A., and A.E.C.; visualization, A.B.-E. and B.A.S.; supervision, A.E.C.; project administration, A.B.-E. and A.E.C.; funding acquisition, A.E.C.

Declaration of interests

D.J.B. and A.E.C. are inventors on a patent method of identifying VDJ recombination products, published in 2013, PCT/GB2O13/050516 and WO2013128204A1; in 2015, US2015/0031042; and in 2017, US9797014B2. M.J.T.S. is an employee and share- and option-holder of 10x Genomics.

Inclusion and diversity

We worked to ensure sex balance in the selection of non-human subjects. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in science. While citing references scientifically relevant for this work, we also actively worked to promote gender balance in our reference list.

Published: July 13, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109349.

Supplemental information

Recombination activity. VDJ-seq reads were quantified over each gene for each replicate library and raw read counts are shown for each replicate. A binomial test was used on the mean of two replicates to determine genes with significantly greater read counts than would be expected by chance, and were therefore considered to be actively recombining (R) and those which are not actively recombining (NR) in pro-B cells from WT and IL-7Rα−/− bone marrow cells, and in wild-type FL cells (fdr-adjusted p value < 0.01). Mapped Reads. VDJ-seq reads were mapped to the C57BL/6 mouse genome (genome build mm9). Paired-end read counts are shown for total mapped reverse orientated reads, and mapped reads over the whole VH and DH regions of the Igh locus. All samples were generated with 10 μg of pro-B cell DNA, except IL-7Rα−/− replicates which were made with 1-2 μg of DNA.

All V gene transcripts. RNA-seq raw reads were quantified over each VH gene probe (only VH genes which had detectable transcription are shown). Each of two replicates was quantified separately to determine differences in transcription between Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα−/−/Rag2−/− pro-B cells. The adjusted mean for each probe, as well as the log2-fold change and adjusted p value in the IL-7Rα−/−/Rag2−/− relative to Rag2−/− samples was calculated by DESeq2. ∗ - Significantly differentially expressed genes. Differentially expressed V genes. Table of significantly differentially expressed genes. Differentially expressed antisense. Significantly differentially expressed transcripts over Igh V intergenic regions in Rag2−/− and IL-7Rα−/−Rag2−/− pro-B cells. RNA-seq raw reads were quantified over intergenic non-coding transcript probes (see Figure 3E – length of probes shown in bp). Each of two replicates was quantified separately. The adjusted mean for each probe, log2-fold change and adjusted p value in the IL-7Rα−/−Rag2−/− relative to Rag2−/− samples was calculated by DESeq2. Transcripts significantly differentially expressed are marked with ∗.

ATAC-seq raw reads were quantified over EBF1 binding sites genome-wide for each of two replicates. The adjusted mean for each probe, as well as the log2-fold change and adjusted p value in the IL-7Rα−/− Rag2−/− relative to Rag2−/− samples was calculated by DESeq2.

References

- Abarrategui I., Krangel M.S. Regulation of T cell receptor-alpha gene recombination by transcription. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolino E., Reddy K., Medina K.L., Parganas E., Ihle J., Singh H. Regulation of interleukin 7-dependent immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable gene rearrangements by transcription factor STAT5. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:836–843. doi: 10.1038/ni1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland D.J., Wood A.L., Johnston C.M., Bunting S.F., Morgan G., Chakalova L., Fraser P.J., Corcoran A.E. Antisense intergenic transcription in V(D)J recombination. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:630–637. doi: 10.1038/ni1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland D.J., Wood A.L., Afshar R., Featherstone K., Oltz E.M., Corcoran A.E. Antisense intergenic transcription precedes Igh D-to-J recombination and is controlled by the intronic enhancer Emu. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5523–5533. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02407-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland D.J., Koohy H., Wood A.L., Matheson L.S., Krueger F., Stubbington M.J.T., Baizan-Edge A., Chovanec P., Stubbs B.A., Tabbada K. Two mutually exclusive local chromatin states drive efficient V(D)J recombination. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2475–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller S., Grosschedl R. The regulatory network of B-cell differentiation: a focused view of early B-cell factor 1 function. Immunol. Rev. 2014;261:102–115. doi: 10.1111/imr.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro J.D., Giresi P.G., Zaba L.C., Chang H.Y., Greenleaf W.J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro J.D., Wu B., Chang H.Y., Greenleaf W.J. ATAC-seq: a method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2015;109:21.29.1–21.29.9. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2129s109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho T.L., Mota-Santos T., Cumano A., Demengeot J., Vieira P. Arrested B lymphopoiesis and persistence of activated B cells in adult interleukin 7(-/)- mice. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1141–1150. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N.M., Loguercio S., Verma-Gaur J., Degner S.C., Torkamani A., Su A.I., Oltz E.M., Artyomov M., Feeney A.J. Deep sequencing of the murine IgH repertoire reveals complex regulation of nonrandom V gene rearrangement frequencies. J. Immunol. 2013;191:2393–2402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chovanec P., Bolland D.J., Matheson L.S., Wood A.L., Krueger F., Andrews S., Corcoran A.E. Unbiased quantification of immunoglobulin diversity at the DNA level with VDJ-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:1232–1252. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2018.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury D., Sen R. Stepwise activation of the immunoglobulin mu heavy chain gene locus. EMBO J. 2001;20:6394–6403. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury D., Sen R. Transient IL-7/IL-7R signaling provides a mechanism for feedback inhibition of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements. Immunity. 2003;18:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran A.E. The epigenetic role of non-coding RNA transcription and nuclear organization in immunoglobulin repertoire generation. Semin. Immunol. 2010;22:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran A.E., Smart F.M., Cowling R.J., Crompton T., Owen M.J., Venkitaraman A.R. The interleukin-7 receptor alpha chain transmits distinct signals for proliferation and differentiation during B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 1996;15:1924–1932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran A.E., Riddell A., Krooshoop D., Venkitaraman A.R. Impaired immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in mice lacking the IL-7 receptor. Nature. 1998;391:904–907. doi: 10.1038/36122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfe S.A., Paige C.J. The many roles of IL-7 in B cell development; mediator of survival, proliferation and differentiation. Semin. Immunol. 2012;24:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T., Pasca di Magliano M., McManus S., Sun Q., Bonifer C., Tagoh H., Busslinger M. Stepwise activation of enhancer and promoter regions of the B cell commitment gene Pax5 in early lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2009;30:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias S., Silva H., Jr., Cumano A., Vieira P. Interleukin-7 is necessary to maintain the B cell potential in common lymphoid progenitors. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:971–979. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert A., McManus S., Tagoh H., Medvedovic J., Salvagiotto G., Novatchkova M., Tamir I., Sommer A., Jaritz M., Busslinger M. The distal V(H) gene cluster of the Igh locus contains distinct regulatory elements with Pax5 transcription factor-dependent activity in pro-B cells. Immunity. 2011;34:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsson L., Licence S., Gaspal F., Bell S., Lane P., Corcoran A.E., Mårtensson I.L. Impaired B-1 and B-2 B cell development and atypical splenic B cell structures in IL-7 receptor-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:3595–3603. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney A.J. Lack of N regions in fetal and neonatal mouse immunoglobulin V-D-J junctional sequences. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:1377–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxa M., Skok J., Souabni A., Salvagiotto G., Roldan E., Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. 2004;18:411–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimova T., Guo C., Ghosh A., Qiu X., Montefiori L., Verma-Gaur J., Choi N.M., Feeney A.J., Sen R. A structural hierarchy mediated by multiple nuclear factors establishes IgH locus conformation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1683–1695. doi: 10.1101/gad.263871.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Yoon H.S., Franklin A., Jain S., Ebert A., Cheng H.-L., Hansen E., Despo O., Bossen C., Vettermann C. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Györy I., Boller S., Nechanitzky R., Mandel E., Pott S., Liu E., Grosschedl R. Transcription factor Ebf1 regulates differentiation stage-specific signaling, proliferation, and survival of B cells. Genes Dev. 2012;26:668–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.187328.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y.C., Laslo P., Cheng J.X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesslein D.G.T., Pflugh D.L., Chowdhury D., Bothwell A.L.M., Sen R., Schatz D.G. Pax5 is required for recombination of transcribed, acetylated, 5′ IgH V gene segments. Genes Dev. 2003;17:37–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1031403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesslein D.G.T., Yang S.Y., Schatz D.G. Origins of peripheral B cells in IL-7 receptor-deficient mice. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Ba Z., Zhang Y., Dai H.-Q., Alt F.W. CTCF-binding elements mediate accessibility of Rag substrates during chromatin scanning. Cell. 2018;174:102–116.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H.D., Teale J.M. Comparison of the fetal and adult functional B cell repertoires by analysis of VH gene family expression. J. Exp. Med. 1988;168:589–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhunjhunwala S., van Zelm M.C., Peak M.M., Cutchin S., Riblet R., van Dongen J.J.M., Grosveld F.G., Knoch T.A., Murre C. The 3D structure of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus: implications for long-range genomic interactions. Cell. 2008;133:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Resch W., Corbett E., Yamane A., Casellas R., Schatz D.G. The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell. 2010;141:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Angelin-Duclos C., Park S., Calame K.L. Changes in histone acetylation are associated with differences in accessibility of V(H) gene segments to V-DJ recombination during B-cell ontogeny and development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2438–2450. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2438-2450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Hashimshony T., Sawai C.M., Pongubala J.M.R., Skok J.A., Aifantis I., Singh H. Regulation of immunoglobulin light-chain recombination by the transcription factor IRF-4 and the attenuation of interleukin-7 signaling. Immunity. 2008;28:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Chaumeil J., Micsinai M., Wang J.M.H., Ramsey L.B., Baracho G.V., Rickert R.C., Strino F., Kluger Y., Farrar M.A. IL-7 functionally segregates the pro-B cell stage by regulating transcription of recombination mediators across cell cycle. J. Immunol. 2012;188:6084–6092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C.M., Wood A.L., Bolland D.J., Corcoran A.E. Complete sequence assembly and characterization of the C57BL/6 mouse Ig heavy chain V region. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4221–4234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K., Lai A.Y., Hsu C.-L., Kondo M. IL-7 receptor signaling is necessary for stage transition in adult B cell development through up-regulation of EBF. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1197–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBien T.W. Fates of human B-cell precursors. Blood. 2000;96:9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc M.-P., Giudicelli V., Duroux P., Jabado-Michaloud J., Folch G., Aouinti S., Carillon E., Duvergey H., Houles A., Paysan-Lafosse T. IMGT®, the international ImMunoGeneTics information system® 25 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue, D1):D413–D422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.S., Hayakawa K., Hardy R.R. The regulated expression of B lineage associated genes during B cell differentiation in bone marrow and fetal liver. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:951–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.C., Jhunjhunwala S., Benner C., Heinz S., Welinder E., Mansson R., Sigvardsson M., Hagman J., Espinoza C.A., Dutkowski J. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin S., McManus S., Cobaleda C., Novatchkova M., Delogu A., Bouillet P., Strasser A., Busslinger M. Role of STAT5 in controlling cell survival and immunoglobulin gene recombination during pro-B cell development. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:171–179. doi: 10.1038/ni.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M., Powers S.E., Maienschein-Cline M., Bartom E.T., Hamel K.M., Kee B.L., Dinner A.R., Clark M.R. Epigenetic repression of the Igk locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1212–1220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M., Okoreeh M.K., Kennedy D.E., Maienschein-Cline M., Ai J., McLean K.C., Kaverina N., Veselits M., Aifantis I., Gounari F., Clark M.R. CXCR4 signaling directs Igk recombination and the molecular mechanisms of late B lymphopoiesis. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:1393–1403. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0468-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraskovsky E., Peschon J.J., McKenna H., Teepe M., Strasser A. Overexpression of Bcl-2 does not rescue impaired B lymphopoiesis in IL-7 receptor-deficient mice but can enhance survival of mature B cells. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:1367–1375. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V., Bryan Wu Y.C., Kipling D., Dunn-Walters D. Ageing of the B-cell repertoire. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015;370:20140237. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson L.S., Bolland D.J., Chovanec P., Krueger F., Andrews S., Koohy H., Corcoran A.E. Local chromatin features including PU.1 and IKAROS binding and H3K4 methylation shape the repertoire of immunoglobulin kappa genes chosen for V(D)J recombination. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1550. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina K.L., Tangen S.N., Seaburg L.M., Thapa P., Gwin K.A., Shapiro V.S. Separation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells from B-cell-biased lymphoid progenitor (BLP) and Pre-pro B cells using PDCA-1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic J., Ebert A., Tagoh H., Tamir I.M., Schwickert T.A., Novatchkova M., Sun Q., Huis In ’t Veld P.J., Guo C., Yoon H.S. Flexible long-range loops in the VH gene region of the Igh locus facilitate the generation of a diverse antibody repertoire. Immunity. 2013;39:229–244. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milford T.A., Su R.J., Francis O.L., Baez I., Martinez S.R., Coats J.S., Weldon A.J., Calderon M.N., Nwosu M.C., Botimer A.R. TSLP or IL-7 provide an IL-7Rα signal that is critical for human B lymphopoiesis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016;46:2155–2161. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.P., Izon D., DeMuth W., Gerstein R., Bhandoola A., Allman D. The earliest step in B lineage differentiation from common lymphoid progenitors is critically dependent upon interleukin 7. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:705–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefiori L., Wuerffel R., Roqueiro D., Lajoie B., Guo C., Gerasimova T., De S., Wood W., Becker K.G., Dekker J. Extremely long-range chromatin loops link topological domains to facilitate a diverse antibody repertoire. Cell Rep. 2016;14:896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt S.L., Urbánek P., Rolink A., Busslinger M. Essential functions of Pax5 (BSAP) in pro-B cell development: difference between fetal and adult B lymphopoiesis and reduced V-to-DJ recombination at the IgH locus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:476–491. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt S.L., Heavey B., Rolink A.G., Busslinger M. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature. 1999;401:556–562. doi: 10.1038/44076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan M., Grosschedl R. Coordinate regulation of B cell differentiation by the transcription factors EBF and E2A. Immunity. 1999;11:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhomchuk D., Borodina T., Amstislavskiy V., Banaru M., Hallen L., Krobitsch S., Lehrach H., Soldatov A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish Y.K., Baez I., Milford T.-A., Benitez A., Galloway N., Rogerio J.W., Sahakian E., Kagoda M., Huang G., Hao Q.-L. IL-7 dependence in human B lymphopoiesis increases during progression of ontogeny from cord blood to bone marrow. J. Immunol. 2009;182:4255–4266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passtoors W.M., van den Akker E.B., Deelen J., Maier A.B., van der Breggen R., Jansen R., Trompet S., van Heemst D., Derhovanessian E., Pawelec G. IL7R gene expression network associates with human healthy ageing. Immun. Ageing. 2015;12:21. doi: 10.1186/s12979-015-0048-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon J.J., Morrissey P.J., Grabstein K.H., Ramsdell F.J., Maraskovsky E., Gliniak B.C., Park L.S., Ziegler S.F., Williams D.E., Ware C.B. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1955–1960. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongubala J.M.R., Northrup D.L., Lancki D.W., Medina K.L., Treiber T., Bertolino E., Thomas M., Grosschedl R., Allman D., Singh H. Transcription factor EBF restricts alternative lineage options and promotes B cell fate commitment independently of Pax5. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:203–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridans C., Holmes M.L., Polli M., Wettenhall J.M., Dakic A., Corcoran L.M., Smyth G.K., Nutt S.L. Identification of Pax5 target genes in early B cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2008;180:1719–1728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulivarthy S.R., Lion M., Kuzu G., Matthews A.G., Borowsky M.L., Morris J., Kingston R.E., Dennis J.H., Tolstorukov M.Y., Oettinger M.A. Regulated large-scale nucleosome density patterns and precise nucleosome positioning correlate with V(D)J recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E6427–E6436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605543113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-I-Domingo R., Bilic I., Vilagos B., Tagoh H., Ebert A., Tamir I.M., Smeenk L., Trupke J., Sommer A., Jaritz M., Busslinger M. The B-cell identity factor Pax5 regulates distinct transcriptional programmes in early and late B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3130–3146. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochman Y., Spolski R., Leonard W.J. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γ(c) family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]