Abstract

Background:

Current understanding of amyloid-β protein (Aβ) aggregation and toxicity provides an extensive list of drugs for treating Alzheimer’s disease (AD); however, one of the most promising strategies for its treatment has been tri-peptides.

Objective:

The aim of this study is to examine those tri-peptides, such as Arg-Arg-Try (RRY), which have the potential of Aβ1–42 aggregating inhibition and Aβ clearance.

Methods:

In the present study, in silico, in vitro, and in vivo studies were integrated for screening tri-peptides binding to Aβ, then evaluating its inhibition of aggregation of Aβ, and finally its rescuing cognitive deficit.

Results:

In the in silico simulations, molecular docking and molecular dynamics determined that seven top-ranking tri-peptides could bind to Aβ1–42 and form stable complexes. Circular dichroism, ThT assay, and transmission electron microscope indicated the seven tri-peptides might inhibit the aggregation of Aβ1–42 in vitro. In the in vivo studies, Morris water maze, ELISA, and Diolistic staining were used, and data showed that RRY was capable of rescuing the Aβ1–42-induced cognitive deficit, reducing the Aβ1–42 load and increasing the dendritic spines in the transgenic mouse model.

Conclusion:

Such converging outcomes from three consecutive studies lead us to conclude that RRY is a preferred inhibitor of Aβ1–42 aggregation and treatment for Aβ-induced cognitive deficit.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β , APP/PS1 transgenic mice, high throughput screening, small peptide

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in the elderly characterized by short-term memory loss, continuous cognitive decline and behavioral disturbances [1]. One of the most widely accepted theory to the development of AD is the amyloid hypothesis, featuring aggregation and fibril formation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides as biomarkers in the pathogenesis of AD [2]. Aβ oligomers potently inhibited long-term potentiation, enhanced long-term depression, and reduced dendritic spine density in the rodent hippocampus [3]. Therefore, Aβ is a potential target for AD therapeutic intervention. Based on the Aβ hypothesis, there are a large number of potential molecules for developing AD treatment, for example, the peptide-based inhibitors of Aβ aggregation have drawn much attention during the last two decades [4]. Lots of peptide fragments were identified that bind to the central hydrophobic cores for aggregation of Aβ and preventing Aβ aggregation. Kawasaki and colleagues have found that the arginine-rich tri-peptides exhibit remarkable inhibitory activities for the formation of the aggregates and fibrils of Aβ [5]. However, little effort has been made on the development of a complete small peptide library with the in silico, in vitro, and in vivo studies on the effects of Aβ aggregating inhibition as well as Aβ clearance.

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are commonly used to assess compounds for their properties to bind to some proteins with active sites and can be applied to virtual screening for molecules targeting Aβ aggregation [6]. Information obtained from MD simulations is likely to accelerate the process of novel drug development of AD and have recently been successfully employed in designing Aβ aggregation inhibitors [7]. In order to have a preliminary understanding of small peptides’ effects with Aβ1–42, we used CADD to design and screen tri-peptides, which could bind to Aβ1–42 and prevent Aβ from assembling into aggregates.

In the present study, we firstly performed molecular docking and MD simulations on model systems where Aβ1–42 could interact with different small peptides in silico. Then we used transmission electron microscope (TEM), circular dichroism spectrum, and Thioflavin-T (ThT) assay to confirm that the small peptides could reduce Aβ1–42 aggregates in vitro. Finally, one of the small peptides Arg-Arg-Tyr (RRY) was administered to the amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 (APP/PS1) transgenic (Tg) mice to observe its therapeutic effects through Morris water maze, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and Diolistic labeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

APPswe/PS1dE9 double Tg mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China) (strain type B6C3-Tg [APPswe, PSEN1dE9] 85Dbo/J). In this study, 36 specific pathogen–free (SPF) 12-month-old male APP/PS1 double Tg mice were used (27.70±3.47 g, n = 36), 12 age-matched wild type (Wt) littermates were used as controls (28.12±2.98 g, n = 12). We kept all of the animals under SPF conditions on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle, and food and water were provided to the mice ad libitum.

All experimental procedures involving the animals were performed according to the regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

In silico simulations

Generation of the small peptides’ library

CycloPs was applied to generate a library of structures for di-peptides and tri-peptides [8]. All 20 kinds of natural L-amino acid were used in the generating section of the library. With deletions of the repetitive ones, 4392 tri-peptides and 400 di-peptides peptides were generated in the library.

Molecular docking

The crystal structure of the Human Aβ1–42 (PDB code 1IYT) was used in all simulations including molecular docking and MD simulation [9]. The biopolymer module of SYBYL 1.1 (Tripos Inc., St. Louis, MO) was applied for reparation of the missing and truncated residues of the Aβ properly.

Autodock Vina was employed in this molecular docking. The grid map was set with an 80*80*80 points area, and the points were equally spaced at 0.375 Å. Default values were set in the docking parameters, except for the number of GA runs (200) and energy evaluations (25000000) [10]. Under a tolerance of 2 Å for root mean square deviations (RMSDs), all docked conformations of peptides and Aβ1–42 were clustered, respectively. Moreover, all of the clustered conformations were ranked according to the docking energies at the end of each run for 4,392 peptides.

Molecular dynamics simulations

In the MD simulations, data analysis for the potential peptide-Aβ complexes clustered conformations were completed using the AMBER suite [11]. The all-atom point-charged force field (AMBER ff03), which displayed a good balance between the helix and sheet, was utilized to represent the Aβ [12]. Transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points (TIP3P) model also was used to represent the water solvent accurately [13]. The Gaussian03 program was applied for the acquisition of electrostatic potential of peptides at the HF/6-31 G** level after geometric optimization [14]. Meanwhile, the partial charges of the peptides were derived by fitting the gas-phase electrostatic potential using the restrained electrostatic potential method [15], as well as other force parameters taken from the AMBER GAFF parameter set [16]. Moreover, antechamber tools in AMBER11 were applied for the generation of the missing interaction parameters of the peptides. And to complete the parameters setting section, the entire system was minimized using the steepest decent algorithms for 2000 steps. The MD simulations were run for 30 ns with normal pressure and temperature. The pressure was coupled to 1 bar with anisotropic coupling time of 1.0 ps while the temperature was kept at 300K during the simulation with a coupling time of 0.1 ps. Particle-Mesh Ewald method was applied to compute the long-range electrostate [17]. Also, SHAKE was used to compel all bonds connected to hydrogen atoms, and this enabled a 2.0 fs step in the simulation [18]. Cut-offs of 1.2 nm was used for Aβ. There were 2 additional sodium ions in the case of the negatively charged Aβ. The trajectories were run for 10 ns and recorded every 0.2 ps. Finally, 10 snapshots were taken in total from the trajectory of Aβ1–42 intervals of 1000 ps with peptide-Aβ compound.

Binding free energy calculations

The binding free energies (ΔGbinding) were calculated using the Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) approach inside the AMBER program [19]. The first step of the MM-GBSA method is the generation of multiple snapshots from an MD trajectory of the peptide-Aβ complex, and a total of 250 snapshots were taken from the last 5 ns of the trajectory with an interval of 20 ps. For each snapshot, the free energy is calculated for each molecular species (complex, Aβ and peptide) using the following equations [20]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Gcomplex, GAβ and Gpeptide were the free energies for the complex, Aβ and peptide, respectively. ΔEgas was the molecular mechanic energy of the molecule expressed as the sum of the internal energy of the molecule, the electrostatics and van der Waals (vdW) interactions; ΔGsolvation was the solvation free energy of the molecule; T was the absolute temperature; and ΔS was the entropy of the molecule. ΔEelec was the Coulomb interaction, ΔEvdw was the vdW interaction, and ΔEint was the sum of the bond, angle and dihedral energies; in this case, ΔEint = 0. ΔGGB is polar solvation contribution calculated by solving the GB equation for MM-GBSA method [21]. ΔGnonpolarp was the nonpolar solvation term. γ was the surface tension that was set to 0.0072 kal/(mol Å2) and b was a constant that was set to 0. SASA is the solvent accessible surface area (Å2) that was estimated using the MOLSURF algorithm. The solvent probe radius was set to 1.4 Å to define the dielectric boundary around the molecular surface. To obtain the contribution of each of the binding energy, MM-GBSA was used to decompose the interaction energies of each residue involved in the interaction, while the molecular mechanics and solvation energies did not have entropy contributions. The purpose of the present study was to compare the effect of the peptide relatively, and due to the quantity and duration of the computations, entropy calculation was not included in the analysis.

Trajectory analysis

After the ΔGbinding were calculated, the trajectories of the RRY-Aβ compound, LPFFD-Aβ compound and Aβ monomer were used for further trajectory analysis. The RMSD of these trajectories were generated for stability evaluation based on the 15000000 snapshots. The SASA of all the residues were computed in default parameters with solvent probe radius of 1.4 Å [22]. We calculated the distance between Cγ of Asp23 and the Nζ of Lys28 to examine the potential formation of the Aβ salt bridge [23]. RMSD conformational clustering analysis was used to generate representative structural ensembles for the each simulation [24, 25]. A total of 3000 snapshots for each simulation were employed, and the cutoff value for RMSD neighbor counting was set to 2.0 Å.

In vitro assays

Thioflavin-T assay

The tri-peptides (RRY, WRW, FWW, WRW, RWY, WWW, RGD, WRY) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co. (Shanghai, China). The ThT fluorescence method was used [26], and Aβ1–42 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was dissolved in phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4, 0.01 M) to give a 50μM solution. Peptides were first dissolved in PB at a concentration of 50μM. The final concentration of Aβ1–42 and small peptides were 2.5μM. After incubating at 37°C for 48 h, ThT (5μM in 50 mM glycine-NaOH buffer, pH 8.50) was added. Fluorescence’s information: excitation at 450 nm and emission at 485 nm. Each peptide was examined in triplicate. The fluorescent intensities were recorded, and the percentage of inhibition on the aggregation was calculated.

Circular dichroism assay

50μM Aβ1–42 was freshly mixed in the presence and absence of 50μM tri-peptides (RRY, WRW, FWW, WRW, RWY, WWW, RGD, WRY) in PB. Then all of the solutions were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. With the final concentration of Aβ1–42 and peptides being 5μM, the structures of treated and untreated Aβ1–42 samples were obtained using a circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarimeter (Applied PhotoPhysics, Britain). A quartz cell with 1 mm optical path was used. The spectra were recorded at 25°C between 190 and 260 nm with a bandwidth of 0.5 nm, a 3 s response time and scan speed of 10 nm/min. The data were converted to mean residue ellipticity [h] as described [27].

Transmission electronic microscopy

Aβ1–42 samples were prepared in PB at a working concentration of 50μM. Then the Aβ1–42 samples were incubated with or without 25μM small peptides (RRY, WRW, FWW, WRW, RWY, WWW, RGD, WRY) at a final concentration of 25μM for 48 hs. To detect the structure of these Aβ1–42 samples, 5μl of samples to be imaged were spotted on 300-mesh Formvar-carbon coated copper grid and stained with 1%uranyl formate for 1 min. Afterwards, the samples were air-dried and observed under the TEM (FEI Inc., USA) with a voltage of 80 kV.

Intracerebroventricular delivery of the tri-peptide Arg-Arg-Tyr

To prolong the administration and reduce the degradation rate, intracerebroventricular (ICV) delivery of the small peptides RRY were administered through the lateral ventricles of the mice using osmotic pumps (model 2002, Alzet) as described [28]. The small peptides were resolved in the PBS containing 0.1%bovine serum albumin (BSA) with the final concentration of 2.3 mM. We randomly divided the mice into four groups: Tg control (Tg Ctrl), Tg RRY (RRY), Tg vehicle (Vehicle), and Wt control (Wt Ctrl). The RRY group was delivered with the small peptide RRY at a rate of 0.25μl/h for two weeks and the PBS containing 0.1%BSA was used for Tg Vehicle. After the drug administration, the pumps were removed and the mice were allowed to recover for one week. The weight of the pumps as well as the placement of the cannula was checked before and after the ICV administration, assuring the proper delivery of the small peptides.

Morris water maze

The Morris water maze (MWM) tests were conducted to evaluate the spatial learning and memory ability of the APP/PS1 Tg AD mice after administering the small peptides as described [29]. The MWM test consists of a five-day acquisition trial, a one day probe test and a two day reversal test [30]. There were four contiguous trails per day in the acquisition trail. The timer was set to 60 s, and automatically stopped once the mouse reached the platform within the 60 s and remained on the platform for 5 s. The mice were manually moved to the platform and allowed to stay on the platform for 20 s if it could not locate the platform. The probe test was conducted 24 h after the completion of the acquisition trial, and the reversal test was conducted 24 h later. On the reversal test (days 7–8), the platform was placed at the quadrant opposite to the location from Day 1 to Day 5, and the mice were then retrained in four sessions per day. After each trial, the mice were dried off in their housing facilities next to an electric heater for 30 min. The trajectory and escape latency of the mice were recorded, and the average escape latency was analyzed each day. In our experiment, we recorded the site crossovers on the platform, the path length of each group in each quadrant and the duration of each group in each quadrant in the extinction phase for 60 s.

Tissue preparation

CSF samples of the mice were collected through the Cisterna Magna [31]. Then all of the mice were sacrificed under deep anesthesia. The venous blood of the mice was collected with 1 mL syringes, followed by transcardial perfusions with ice-cold PBS for 5 min, which included protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Then, the blood samples were allowed to precipitate for 2 h at room temperature before being centrifuged for 15 min at 1000×g. The serum was removed and stored at –80°C. The brain from each of the 8 mice was first removed and immediately frozen at –80°C for biochemical analysis. The other 4 mice were perfused with 2%paraformaldehyde and post-fixed for 12 h, and then the coronal sections (200μm) were cut on a vibratome (Leica VT 1000 S, Germany), afterwards one intact section was stored in 0.01 M PBS for the Diolistic labeling. The dentate gyrus and adjacent cortex –2.2 mm to –2.4 mm relative to the Bregma were taken as the region of interest in the analyses.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

We measured the concentration of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in the mice’s brain with the ELISA kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. The frozen brains were thawed and minced. Then, the cerebral tissues of the brain were weighed; an aliquot of the tissue was homogenized in a RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1%NP-40, 0.5%sodium deoxycholate, 0.1%SDS, sodium orthovanadate, sodium fluoride, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), leupeptin and a cocktail of protease inhibitors. The homogenates were centrifuged (100,000×g, 1 h, 4°C), and the supernatants were stored at –70°C for additional analysis of soluble Aβ. Then, we sonicated the pellet in 5 M guanidine Tris buffer; the samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and then centrifuged (100,000×g, 1 h, 4°C), and the supernatants were stored for analysis of insoluble Aβ.

DiOlistic labeling and morphological analyses

The gene gun bullets were prepared as described [32, 33]. We mixed 4 mg of gold particles (1.6μm diameter) with 2.5 mg DiI (Sigma-Aldrich Inc) and dissolved in 250μl methylene chloride. After drying, the coated particles were collected in 1.5 ml water and placed into a sonicator for 5 min. The solution was vortexed for 15 s and immediately transferred to a Tefzel tubing (Bio-Rad). The labeled sections were rinsed in 0.01 M PBS three times and resuspended in PBS at 4°C overnight in order for the dye to diffuse through the neuronal membranes. The images of DiI-impregnated cells were taken using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The neuron was scanned at 1μm increments along the Z-axis and reconstructed using LAS AF software to analyze the dendrite segments. The density of the dendritic spines was measured on 10 to 30 randomly chosen dendrites from 3 to 6 neurons, calculated by quantifying the number of spines per unit length of dendrite and normalized per 10μm of dendrite length. 3D reconstructions of confocal images were performed with an Imaris 6.4.2 (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

The data represented as the mean±standard error (S.E.M) including the measurement of body weight. To compare a variable among three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effect of small peptide within the Tg group. Two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons of more than two groups. Repeated measures of ANOVA were performed to analyze the MWM data. p < 0.05 was considered to be significant and n = 5 otherwise exact experimental numbers were shown in the figures. In the analyses of ELISA and Diolistic labeling, we used a simple t-test to determine the difference between Wt Ctrl and Tg Ctrl. SPSS 13.0 software was used for all the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

A schematic diagram demonstrates the outline of the study. First of all, CycloPs were used to construct a small peptide library containing 400 bi-peptides and 4392 tri-peptides. In this work a computational approach was applied for structure-based virtual screening of 4,392 tri-peptides to find novel potential inhibitor of Aβ1–42 aggregation. So-called in silico computer-aided search for Aβ1–42 aggregation inhibitor was performed on molecular docking, MD, binding free energy calculation and trajectory analysis based on the PDB structure of Aβ1–42. The results of the supercomputing-based calculations with in vitro assays including ThT, CD, and TEM were analyzed and compared with the results of high-throughput flexible molecular docking. Seven top rating peptides were chosen and the best-performing tri-peptide RRY was used for subsequent studies. RRY was administered into the cerebral ventricle of the APP/PS1 Tg mice for in vivo experiment. After the MWM test of the mice, ELISA, immunocytochemistry, and Diolistic labeling were then performed to evaluate the inhibition of Aβ1–42 aggregation and explore the mechanism of behavior improvement. Therefore, we proposed that RRY could be a potential inhibitor of Aβ1–42 aggregation through this large-scale peptides screening (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of the study: CycloPs used to construct a small peptide library containing 400 bi-peptides and 4392 tri-peptides.

Following a series of in silico studies including molecular docking, molecular dynamics, binding free energy calculation and trajectory analysis based on the PDB structure of Aβ1–42, seven top rating peptides were chosen. Next, in vitro assays including ThT, CD and TEM were carried out, and the best-performing tri-peptide RRY was used for subsequent studies. RRY was administered into the cerebral ventricle of the APP/PS1 Tg mice. After the MWM test of the mice, a set of in vivo experiments was then performed. Therefore, we determined that RRY can be a potential inhibitor of Aβ1–42 aggregation.

The tri-peptides could bind to the Aβ1–42 in the in silico simulations

The conformations of peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes remained stable in MD simulation

The conformations of peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes from 0 to 10 ns in the simulations were also analyzed. Clustering analyses were implied to generate a reduced set of representative conformational states for potential peptides. Representative conformations of each MD simulation were presented (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Small peptides bind to Aβ1–42 to form a stable structure in silico. A) The final conformations of the small peptides-Aβ1–42 complexes of MD simulation were relatively constant compared to the dramatically changed conformations of Aβ1–42 monomer. B) Root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) were calculated to investigate the stability of the small peptide- Aβ1–42 complexes. Most complexes remained stable at the last 3 ns of the whole 10 ns simulation. C) RMSDs of the Aβ1–42-RRY complex. The RMSD of Aβ1–42 remained steady at approximately 7 Å or 7 Å in three repeated simulations, indicating that the complex is relatively stable. The red, blue, and black were three repeating trajectories for the MD simulations. D) The SASA of each residue of Aβ1–42 in the presence (black) and absence (red) of RRY. The greater values revealed the weaker hydrophobicity of the residues. E) The conformations of the RRY- Aβ1–42 complexes of MD simulation were relatively constant. It showed that the residues Asp1, Ala2, Gly33, Leu34, Gly38, and Ala42 in Aβ1–42 form hydrogen bonds with RRY. According to the stability of hydrogen bonds, we further emphatically selected five bonds formed by the three Aβ residues above: Asp-1, Ala-2, and Ala-42, to conduct time dependence analysis, the details of which were illustrated in Fig. 2G. F) The distance between Asp23 and Lys28 of Aβ1–42. The distance between Asp23 and Lys28 remained constant at approximately 15 nm when RRY is bound to Aβ1–42 (black), which suggested the absence of the Asp23-Lys28 salt bridge. The distance between Asp23 and Lys28 shows a sharp decrease in Aβ1–42 without RRY bound (red), which suggested the formation of the Asp23-Lys28 salt bridge. G) The key hydrogen bond distances between Aβ1–42 and RRY with time dependence. The five lines in the graph respectively representative the distance between: (i) the hydrogen atom (H) at the amino terminal of RRY and the double bond oxygen atom (O) of the Ala-42 carboxyl group of Aβ (black); (ii) the hydrogen atom (H) on RRY’s first carbon atom and single bond oxygen atom (OXT) of Aβ’s Ala-42 carboxyl group (red); (iii) the hydrogen bond formed by the oxygen atom (O) of RRY and the amino terminal hydrogen atom (H) of Asp-1 of Aβ (blue); (iv) the oxygen atom (O) of RRY and the amino terminal hydrogen atom H of Ala-2 of Aβ (green); (v) RRY’s single-bond oxygen atom O with the hydrogen atom (H) at the amino terminal of Asp-1 of Aβ (purple). The distance between the residues in Aβ1–42 and RRY stays under 3.5 Å and remains stable, which indicated the formation of strong hydrogen bonds. H) The conformation of Aβ1–42 during the MD simulation in the presence RRY. The conformation of Aβ1–42 was stable with RRY bound Aβ1–42.

The conformations of the WRW-Aβ1–42, RGD-Aβ1–42, and WRY-Aβ1–42 complexes were stable with a relatively constant proportion of α-helix and turn structure. The relatively stable turn structures could also be observed in the conformations of the FWW-Aβ1–42 and RWY-Aβ1–42 complexes. Moreover, formation of β-sheet structure was not observed in all conformations of peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes. These results suggested that potential peptides stabilized the α-helix and turn structures of Aβ1–42, and inhibited the β-sheet structure formation, thereby maintaining stable conformations.

Peptides bind to Aβ1–42 to form a stable complex in silico

Mass screening was performed in the molecular docking by calculating the docking energies of all of the peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes. Seven peptides including Trp-Arg-Trp (WRW), Phe-Trp-Trp (FWW), RRY, Arg-Trp-Tyr (RWY), Trp-Trp-Trp (WWW), Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), and Trp-Arg-Tyr (WRY) with high scores as well as appropriate docking sites were chosen as potential peptides.

The MD simulations were performed to investigate the stability of the peptide-Aβ complexes according to the RMSDs (Fig. 2B). The RMSDs of RGD-Aβ1–42 complex remained stable at around 7.5 Å, and the RMSDs of RRY-Aβ1–42 complex fluctuated at around 6 Å. The RMSDs of WRY and WRW also remained relatively stable around 6.5 Å. All of the RMSDs of peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes were below 11 Å, and indicated that these peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes were relatively stable.

The binding free energy of peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes were relatively low

The binding free energies (ΔGbinding) of Aβ1–42 and peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes were calculated (Table 1) with the MM_GBSA method. The calculated binding free energy of the WRY-Aβ1–42 complex was –34.0396 kcal/mol and the WWW-Aβ1–42 complex was –26.2614 kcal/mol, which indicated that WWW and WRY bound strongly to Aβ. The free binding energy of RRY to the Aβ1–42 was ΔGbinding = –5.8458 kcal/mol, which was higher than the binding energy of the β-sheet breaker peptide LPFFD [33]. For the WRY-Aβ1–42 complex, the electrostatic energy and the vdW energy with nonpolar solvation contribution favorably contributed to the binding free energies, where the electrostatic energy contributed to a greater extent than that of vdW. The binding free energy of these peptide-Aβ complexes showed that the binding process was thermodynamically favorable. Therefore, we concluded that all of the potential peptides bound stably to Aβ1–42.

Table 1.

The binding free energies (ΔGbinding) of Aβ and peptide-Aβ complexes with the MM_GBSA method and the contributions of each force

| Contribution | WRW | FWW | RRY | |||||

| mean | SEM | mean | SEM | mean | SEM | |||

| ΔEelec | –127.8622 | 31.7238 | –39.2240 | 32.8006 | –227.0111 | 23.7255 | ||

| ΔEvdw | –31.5055 | 3.5854 | –32.2817 | 5.2270 | –23.3137 | 4.9036 | ||

| ΔEgas | –159.3677 | 31.6756 | –71.5057 | 35.9271 | –250.3248 | 24.3890 | ||

| ΔGnonpolarp | –4.7953 | 0.3023 | –5.7332 | 0.6516 | –3.7533 | 0.4370 | ||

| ΔGGB | 141.7892 | 32.1894 | 52.2206 | 33.8447 | 248.2323 | 23.5212 | ||

| ΔGsolvation | 136.9939 | 32.2142 | 46.4874 | 33.4034 | 244.4790 | 23.4184 | ||

| ΔGbinding | –22.3738 | –25.0183 | –5.8458 | |||||

| Contribution | RWY | WWW | RGD | WRY | ||||

| mean | SEM | mean | SEM | mean | SEM | mean | SEM | |

| ΔEelec | –105.6885 | 21.4133 | 15.1222 | 24.6331 | –134.6431 | 31.9144 | –188.2275 | 22.2736 |

| ΔEvdw | –24.5772 | 4.4112 | –32.8116 | 5.4779 | –13.2767 | 2.6566 | –41.7505 | 4.8319 |

| ΔEgas | –130.3117 | 22.3945 | –17.6893 | 27.6163 | –147.9199 | 32.3657 | –229.9781 | 25.0730 |

| ΔGnonpolarp | –4.2947 | 0.4543 | –5.4620 | 0.6199 | –2.7636 | 0.2908 | –6.4817 | 0.3609 |

| ΔGGB | 118.0171 | 20.9540 | –3.1101 | 24.9175 | 142.9110 | 30.3403 | 202.4201 | 22.6944 |

| ΔGsolvation | 113.7224 | 20.7604 | –8.5721 | 24.6319 | 140.1474 | 30.1113 | 195.9385 | 22.5127 |

| ΔGbinding | –16.5893 | –26.2614 | –7.7724 | –34.0396 | ||||

The interaction between RRY and Aβ1–42

In order to figure out the inhibition effect of RRY, MD simulations were performed to investigate the stability of RRY Aβ1–42. The RMSD of the complex remained constant at approximately 7 Å or 10 Å after 10 ns, and the variations were within 1 Å.

In order to evaluate the stability of Aβ1–42-RRY complex, the RMSD of Aβ1–42-RRY was analyzed for three times. Aβ1–42-RRY complex remains steady at approximately 7 Å or 7 Å in three repeated simulations, indicating that the complex was relatively stable. The red, blue and black were three trajectories representing for the repeated MD simulations (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, hydrophobic interactions were one of the most essential interactions between RRY and Aβ1–42. Studies showed that the helix structure correlates with the hydrophobicity of the residues, and the β-sheet structure is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions. Thus, the SASA per residue was calculated to examine the extent of hydrophobic bonds in different regions of Aβ1–42 with and without RRY binding. The positive and negative values revealed a decrease and increase, respectively, in the hydrophobic character of the residues (Fig. 2D). This result suggested that Aβ1–42 weakened the hydrophobic interactions in the aggregation of the Aβ1–42. The detailed conformations of the RRY- Aβ1–42 complexes of MD simulation are relatively constant. The molecular docking analysis showed that the residues Asp1, Ala2, Gly33, Leu34, Gly38, and Ala42 in Aβ1–42 form hydrogen bonds with RRY (Fig. 2E). The salt bridge formation was also measured. The formation of the salt bridge between Asp23 and Lys28 in monomer folding plays a central role in the aggregation of Aβ [34, 35]. The distance between the Asp23 and Lys28 for the Aβ1–42 and RRY- Aβ1–42 complexes was shown in Fig. 2F, and the distance sharply decreased in Aβ1–42 without RRY binding, it suggested the formation of the Asp23-Lys28 salt bridge. When RRY was bound to Aβ1–42, the distance between Asp23 and Lys28 held steady at approximately 15 nm for 30 ns. This result showed that the probability of Asp23-Lys28 salt bridge formation in the RRY- Aβ1–42 complex was lower. In order to measure the key hydrogen bond distances between Aβ1–42 and RRY with time dependence, MD analysis demonstrated the relations between hydrogen bond distance and time elapse. The distance between the five key residues in Aβ1–42 and RRY peptide stayed under 3.5 Å and remains stable after 10000 ps, which indicated the formation of strong hydrogen bonds inside the peptide-Aβ1–42 complexes (Fig. 2G).

The structure analysis of Aβ1–42 (from 20 ns to 30 ns) in the simulations showed that the structure of the RRY- Aβ1–42 complex (Fig. 2H) was stable with a relatively constant proportion of α-helices and the presence of a turn structure. RRY binded to both the C-terminal and N-terminal, it might explain the stability of RRY- Aβ1–42. In contrast, the conformation of Aβ without binding of RRY changed randomly (figure not shown). These results suggested that RRY stabilized the initial structure of Aβ1–42, thus inhibiting Aβ aggregation.

The mechanism of the inhibition of RRY on the aggregates of Aβ

AD is characterized by Aβ plaques, which contains fibrillar aggregates of the Aβ peptide. Aβ1–42 monomer is featured with α-helix in its C-terminal, which can transfer into β-strands. The transition promotes the formation of neurotoxic Aβ oligomers and the C-terminal residues of Aβ form the core structure of the Aβ oligomers [36]. In the Aβ oligomers, residues 18–26 and 31–42 of the Aβ1–42 monomers form β1-strand and β2-strand to further form a β-strand-turn-β-strand motif, with vital hydrophobic residues: Phe-19, Ala-21, Val-36, and Gly-38 in the two β-strands. When aggregating, an intermolecular, parallel and in-register β-sheet is formed by β-strands through hydrophobic interaction pairs, Phe-19/Gly-38 and Ala-21/Val-36. Besides, the intermolecular salt bridge formation of Asp23-Lys28 enhances hydrophobic interaction and plays a critical role in the aggregation and hydrogen bonds [37].

The present study showed that RRY can bind to Aβ1–42 to form the complex stably, mainly through hydrophobic interactions, and several hydrogen bonds were formed between them as well, enhancing the stability. Strong hydrogen bonds can inhibit the α-helix to β-sheet transition in Aβ142 and stabilize its initial structure. Molecular docking and MD simulation were conducted to indicate RRY-Aβ1–42 complex’s high stability, with no formation of β-sheet structure observed in all conformations of complexes. And low free binding energy of RRY to the Aβ1–42 suggested that the binding process was thermodynamically favorable.

Besides, RRY binds to both the C-terminal and N-terminal of Aβ1–42, which might explain the constant proportion of α-helices and the presence of a turn structure, inhibiting the aggregation of Aβ. The essential hydrophobic interaction between RRY and Aβ1–42 occupies hydrophobic residues of Aβ and weaken its ability to form hydrophobic interaction with other Aβs, impairing the Aβ’s aggregation. Moreover, the presence of RRY can increase the distance between Asp23 and Lys28 for the Aβ1–42, therefore greatly lowers the probability of Asp23-Lys28 salt bridge formation, which plays a central role in the aggregation of Aβ.

Inhibition of the aggregation of Aβ1–42 in the in vitro studies incubated with 7 peptides

The ThT fluorescence intensities of Aβ1–42 incubated with 7 peptides

We performed the ThT assay to investigate the inhibition effects of our potential peptides in the aggregation of Aβ1–42 (Fig. 3A). The ThT associated rapidly with aggregated fibrils of the Aβ1–42, resulting in a new excitation at 450 nm and enhanced emission at 485 nm. This transformation depended on the aggregated states of Aβ1–42, as the monomeric or dimeric peptides could not be reflected. As shown in Fig. 3A, most of peptides showed better inhibitory effects on Aβ1–42 aggregation at the concentration of 2.5μM compared to the reference compound Resveratrol [38]. Therefore, experimental data indicated that peptides compounds inhibited Aβ1–42 aggregation.

Fig. 3.

Small peptides inhibit Aβ1–42 aggregation in vitro. A) Inhibition of Aβ1–42 (2.5μM) aggregation by the 7 small peptides with resveratrol as a reference. The measurements were carried out by ThT fluorescence at 485 nm in presence of 2.5μM compounds including Resveratrol, WRW, FWW, RRY, RWY, WWW, RGD, and WRY. Most of the small peptides had higher inhibition of Aβ1–42 aggregation than the reference compound resveratrol. The mean relative fluorescence unit of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–42 incubated with the compounds were statistically different. The values were the means±S.E.M (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, n = 6). B) CD spectroscopy showed less β-sheet structure formation signal in the peptide-Aβ complexes. Aβ1–42 (5μM) samples were incubated at 37°C for 48 h alone (black line) or in the presences of RWY (5μM) (light purple), WWW (5μM) (dark purple), RGD (5μM) (dark blue), WRY (5μM) (orange), WRW (5μM) (red), FWW (5μM) (light blue), or RRY (5μM) (green), respectively. In lower panel, small peptides inhibit the aggregation of Aβ1–42 under negative stains TEM. Samples were dissolved (25μM) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. a) Aβ1–42 peptide alone. Long linear Aβ1–42 fibrils were shown. The fibrils compact in parallel bundles and intercross with each other, forming radial nucleation center, which was shown with arrowheads. b-h) Aβ1–42 treated with small peptides. Only a few short fibrils (b, c, d, e, f) or amorphous aggregates (g, h) are seen. Fibrils and amorphous were also shown with arrowheads. Scale bar = 200 nm.

Decreased β-sheet structure formation in the peptide-Aβ complexes

CD spectroscopy was employed to study the effect of the 7 potential peptides on the structural change of Aβ1–42. As shown in Fig. 3B, the CD spectrum of untreated Aβ1–42 (black line) was found to have a negative band around 216 nm that indicated the formation of the β-sheet structure. The peptides of WWW (dark purple line), RGD (dark blue line), WRY (orange line), WRW (red line), FWW (light blue line), or RRY (green line), led to increasingly more significant decreases of the band around 216 nm, while the peptide of RWY (light purple line) resulted in slight increase of the negative band. These results demonstrated that most potential peptides could reduce the β-sheet structure formation.

Small peptides inhibited the aggregation of Aβ1–42 fibrils in TEM

According to the TEM images, the typical high-density long linear Aβ1–42 fibrils were detected in the image of untreated Aβ1–42 (Fig. 3a). These fibrils compacted in parallel bundles and intercrossed with each other. In contrast, Aβ1–42 samples incubated with these small peptides contained only a few short linear fibrils [Fig. 3b (RWY), 3c (WWW), 3d (FWW), 3e (WRW), 3f (WRY)] or few amount of amorphous aggregates [Fig. 3g (RGD), 3h (RRY)]. Particularly, short bundles of Aβ1–42 were seen in these images, especially in Fig. 3f. and in Fig. 3c and 3d, the fibril bundles intercrossed randomly, developed into irregular aggregates. In Fig. 3g and h, various sizes of amorphous aggregates were detected (shown in arrowheads), and these aggregates were comparatively smaller in Fig. 3h. The results were consistent with the results shown in the ThT and CD assays, thereby proving that those potential peptides could inhibit the aggregation of Aβ1–42 fibrils.

RRY attenuated the spatial learning impairment of the APP/PS1 transgenic mice

The MWM test was conducted to examine whether RRY could improve cognitive abilities such as reference memory and working memory in the APP/PS1 Tg mice. In the first day of the acquisition trial with a visible platform as shown in Fig. 4, no significant difference was observed, therefore indicating that there was no visual distinction among these groups. From the 2nd day to the 5th day, all mice showed progressive decline in the escape latencies. A two-way ANOVA and post-hoc tests showed that group RRY had decreased escape latency compared to the groups Tg Ctrl and Vehicle (F [3,27] = 120.39; ***p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). In the probe test, compared to the Tg Ctrl and vehicle groups, the mice administered with RRY showed more platform passing times (F [3,27] = 13.55; ***p < 0.001), increased path length (F [3,27] = 9.10; ***p < 0.001) and stayed longer on the platform (F [3,27] = 10.76; ***p < 0.001) in the target quadrant (Fig. 4B-D). The results illustrated that RRY could attenuate the reference memory deficit of the APP/PS1 Tg mice. Moreover, the decline of escape latency in the reversal test on the 7th and 8th days displayed that RRY might also improve the working memory of the APP/PS1 Tg mice (F = 97.90[3, 27]; ***p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

RRY attenuates spatial memories deficit of the APP/PS1 transgenic mice in MWM. A) In the first day of acquisition test (visible platform), no significant difference of escape latencies among groups was observed (p > 0.05). During the 2nd day and the 5th day (hidden platform), the mice infuse with RRY showed a shorter latency compared to groups Tg Vehicle and Tg Ctrl (***p < 0.001). In the reversal test, a significant disparity was shown in the 7th and the 8th day (***p < 0.001). B-D) In the probe test on the 6th day, the mice of group RRY pass the platform area more frequently (B) (***p < 0.001), had longer path length (C) (p < 0.01), and stay longer on the platform (D) (***p < 0.001) in the target quadrant than group vehicle and group Tg Ctrl. n = 7.

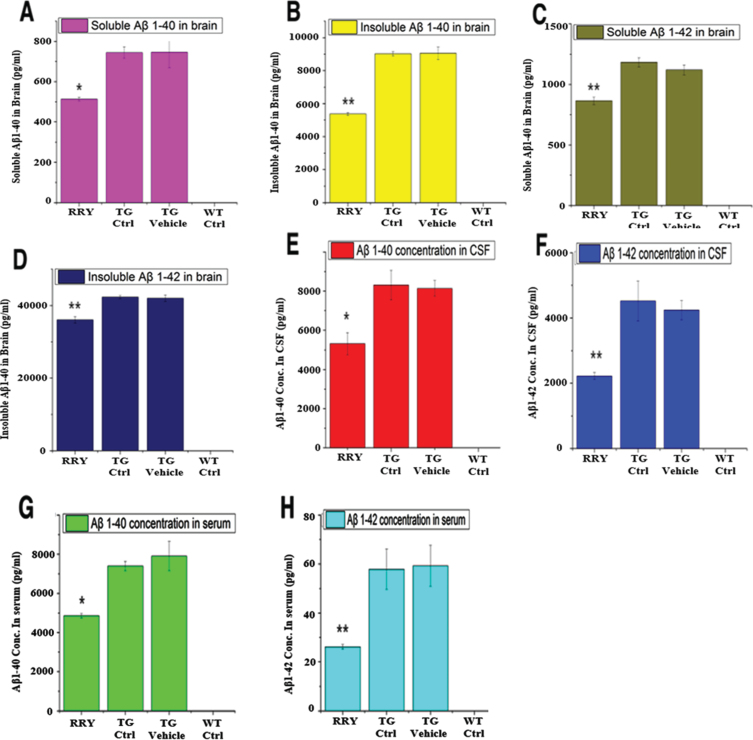

RRY decreased the amount of Aβ in the brain, serum and CSF of the APP/PS1 transgenic mice

The level of soluble and insoluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in brain tissue, CSF and serum of the APP/PS1 Tg mice was measured by ELISA. Comparing to the Tg Ctrl and vehicle groups as shown in Fig. 5, the quantity of soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in the brain homogenates (n = 8, *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 in all four tests), and soluble Aβ1–42 in the serum and CSF (n = 8, *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 in serum and CSF) of the APP/PS1 Tg mice administered with RRY decreased significantly, indicating that RRY might have the ability of eliminating Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in the brain, CSF as well as serum. Aβ level in the wild type mouse was not measurable.

Fig. 5.

The reversal effect of RRY on levels of Aβ1–42 in the brain, CSF and the serum of the APP/PS1 transgenic mice. A decrease in the total levels of insoluble Aβ1–40 (B)/Aβ1–42 (D) and soluble Aβ1–40 (A)/Aβ1–42 (C) in the brain of the APP/PS1 Tg mice after RRY administration is observed compare to the Tg Ctrl and Tg Vehicle groups. And reductions of Aβ1–40/Aβ1–42 levels in the CSF (E, F) and serum (G, H) were also observed in the RRY-treated group. The data are expressed as the means±SEM (n = 8, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). The results showed a decrease in Aβ aggregation in the RRY-treated group.

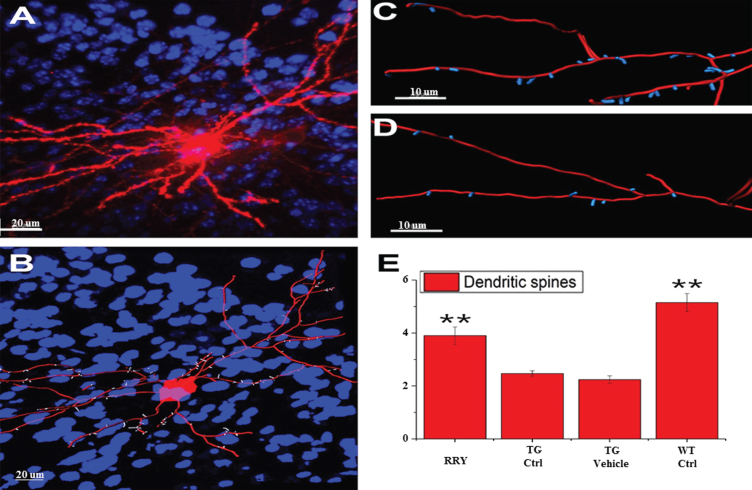

Effect of RRY on dendritic spines in the brain of APP/PS1 transgenic mice

The improved learning and memory ability in the APP/PS1 Tg mice was investigated in the MWM test, which led us to consider whether the same result could be observed in the dendritic spines. To examine this hypothesis, the density of dendritic spines in the neurons of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus was studied by Diolistic labeling. Using the Diolistic labeling of the brain slices and performing quantification analysis of reconstruction and quantification, data in the Fig. 6 showed that the dendritic spines, whose reduction is related to the decline of the synaptic plasticity and neuron impairment in Tg control or vehicle compared to wild type control, increased in the RRY group compared to the Tg Ctrl group (n = 4, **p < 0.01).

Fig. 6.

Demonstration of the reconstruction and quantification of the DiI-labeled neuron in mice and increase in the density of the dendritic spines by RRY in the brains of the APP/PS1 transgenic mice. A) An image of DiI-labeled neuron in the brain of the APP/PS1 Tg mouse administered with RRY (Red: DiI, Blue: DAPI). B) The reconstructed neuron of the APP/PS1 Tg mouse administered with RRY (Red: dendrites and cell body, Blue: nuclus of surrounding cells, white: dendritic spines). C and D showed the comparison of the density of the dendritic spines between the groups RRY (C) and Tg Ctrl (D). E) RRY increased the density of the dendritic spines in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of the APP/PS1 Tg mice compared to the groups Tg Ctrl and Tg Vehicle (n = 4, **p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, application of small peptides in the treatment of AD based on the Aβ hypothesis was investigated. Small peptide library building, in silico simulations, in vitro assays (ThT, CD, and TEM), and in vivo experiments (Morris Water Maze, ELISA, IF assay as well as Diolistic labeling) were integrated to investigate the binding affinity of the small peptides to Aβ1–42, during which RRY emerged to be the most effective one. Thus, this pilot study provides a novel approach involving in silico, in vitro, and in vivo study of small peptide development on AD treatment, and a considerable range of neurodegenerative diseases that have known targets such as Parkinson’s disease. Nevertheless, several problems regarding AD and other screenings remained in this study.

In the past two decades, the peptide-based Aβ aggregation inhibitors, or “fibrillogenesis inhibitor” have drawn much attention in the field of AD therapeutics. The penta-peptide β-sheet breaker such as LPFFD and KLVFF have played effective roles in the inhibition of Aβ aggregation, both in silico and in vivo. A study shows that arginine-rich tri-peptides exhibit remarkable inhibitory activities to the formation of Aβ1–42 37/48 kDa oligomer and fibril [5]. However, a systemic research on the fibrillogenesis inhibitory effect of the small peptides is not yet available. Therefore, exploring a method for primary screening of these small peptide inhibitors to Aβ aggregation is necessary for AD therapeutics.

MD simulations represent a powerful tool in the study of many interesting biological systems as they provide a description of the system of physicochemical properties in terms of microscopic degrees of freedom. In the case of the Aβ peptide, MD results have been employed not only to guide experiments but also act as an instrument to design potential Aβ aggregation inhibitors. In our studies, Molecular docking and MD simulations yielded 7 comprehensively top-ranking tri-peptides based on the binding of Aβ1–42. However, whether the performance of the small peptides is in proper correlation to the simulation outputs requires more research.

In the in silico simulations, several tri-peptides exhibited their abilities to bind and stabilize the initial structure of Aβ1–42 from the value of the binding free energy from the MD simulations, which indicated that these peptides possibly have good affinity to Aβ1–42, suggesting the anti-aggregation properties of these tri-peptides [34]. And the seven best-performing tri-peptides, WRW, FWW, RRY, RWY, WWW, RGD, and WRY, were chosen to conduct the in vitro assays. Besides, the SASA of the tri-peptides and Aβ1–42, the distance of Asp23-Lys28 residues were decreased by these tri-peptides, indicating that the formation of Aβ fibril may be inhibited [22, 42]. In the in vitro assays, the results in the CD, ThT, and TEM showed that the seven tri-peptides can hamper the structural conversion of the Aβ1–42 monomers and inhibit the formation of the Aβ1–42 fibrils, validating the hypothesis in the in silico studies, and suggesting they may attenuate the senile plaque load in vivo. The comprehensively top-ranking tri-peptide RRY was chosen for the subsequent analysis.

In the in vivo experiments, we examined that RRY can ameliorate the process of memory deficit and neurodegeneration in the APP/PS1 Tg AD model mouse, whose brain have age-related increases in the soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, and develop senile plaques at 5 to 6 months of age comparable to those observed in postmortem brains of human AD patients [43, 44]. The reference memory and working memory of the APP/PS1 Tg mice with ICV delivery of RRY were improved compared to the Tg Ctrl and Tg Vehicle group in the MWM experiments, indicating that RRY is able to regulate the cognitive deficit in this AD model.

Since 1992, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has been considered to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD [45, 46]. The production and accumulation of Aβ are believed as a primary event in the progression of AD. It is believed that Aβ, no matter intracellular or extracellular, has neurotoxic property [47, 48]. Recent studies have supported the hypothesis that the accumulation of Aβ within the brain arises from an imbalance in the production and clearance of Aβ. Therefore, the animal models, such as the mouse and drosophila, expressing Aβ are considered potential pathological model for better understanding of the mechanism of AD [49, 50]. In the present study, we measured the quantity of soluble and insoluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the brain of the APP/PS1 Tg mice. The concentration of Aβ in the blood serum and CSF was considered as good indicators for the development of AD [51–54], therefore the concentration of the Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the serum and CSF of the mice was also measured. The results showed that the RRY-treated mice had a lower amount of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in blood serum, CSF, and brain tissue, indicating that RRY is likely to reduce Aβ-related neurotoxicity in the brain of the APP/PS1 mice.

Dendritic spines are the primary recipients of excitatory input in the central nervous system. They provide biochemical compartments that locally control the signaling mechanisms at individual synapses [55]. Study shows that Aβ oligomers extracted from the AD patients can decrease the dendritic spine density in the normal rodent hippocampus [56]. Though the accurate relationship is not yet determined, the intraneuronal Aβ accumulation is also considered responsible for dendritic dysfunction [57]. However, no preferential localization of the abnormal dendritic spines is seen in regions with the accumulation of senile plaques [58], implicating that there are accumulation of Aβ oligomers and deterioration of the microenvironment in the brain, instead of Aβ fibril and senile plaque formations, are responsible for the dysfunction of the synapto-dendritic complex. In our research, the dendritic spines in the hippocampus and the cortex in the APP/PS1 Tg mice were labeled by Diolistic staining. The number of the dendritic spines increased in the RRY-treated mice compared to the Tg Vehicle group, meaning that RRY may play a protective role during the process of synapse dysfunction.

Nonetheless, the mechanisms underlying these results were yet to be clarified. Several assumptions may be responsible for those observations. First of all, Aβ aggregates in the brain cause inflammation, oxidative stress, deteriorating neurogenesis and eventually neuronal loss [59–61]. Besides, Aβ is also involved in many detrimental effects on neurogenesis by interfering the NMDA receptor trafficking [62], aggravating tau pathology [63], and sequestering many key proteins with significant cellular functions in the cell [64]. As studies show that the oligomeric Aβ is detrimental to the functions of the synapto-dendritic complex [56], the increase in the number of the dendritic spines in the RRY-treated mice may implicate that RRY can inhibit the formation of the Aβ oligomer, which corresponds with the results in the in silico and in vitro studies. However, direct evidence is yet to be discovered.

The past two decades have witnessed progress in the development of various kinds of compounds targeting Aβ, such as γ-secretase inhibitor, γ-secretase modulator, β -secretase inhibitor, Aβ aggregation inhibitor, and Aβ vaccine [65]. Yet the effects of most of the compounds were inconclusive, and most clinical trials of anti-Aβ drugs and antibodies failed. This unsatisfied discovery of AD therapy indicating that compounds whose functions are more comprehensive will be inevitable for the therapy of AD. However, most of the studies presently only explore one or a few compounds, and targeting one or few molecules, which makes the discovery of effective drugs inefficient. To address this problem, many high throughput-screening tools such as peptide phage display are introduced [66]. One of the most commonly used tools is the in silico simulation, which includes molecular docking and MD simulations. Effective compounds are discovered and mechanisms underlying ligand-receptor interactions are explored with this method [22, 67]. Nonetheless, problems remain in these in silico studies, which cannot validate the progress of the in silico studies made in the discovery of anti-AD compounds. In current research, through the computational studies mentioned above, a complete tri-peptide library was established, and used for the screening of the anti-fibrillogenesis compound in a more efficient way, which will be financially and costly merely through the in vitro or in vivo ways. However, a good performing molecule in the computational simulations does not guarantee therapeutic effect in an AD patient, and a poor score in the simulations does not invalidate the value of the compound either. Whether or not a compound can be used as an anti-AD drug requires further investigations. Accumulation of Aβ oligomers, Aβ fibril and senile plaque formations are pathological marker of AD. Current study tested Aβ aggregation rather than analyzed Aβ accumulation given short-period of intracerebroventricular delivery of RRY. ELISA is more sensitive in measuring Aβ fragments of brain tissue than quantifying Aβ accumulation change in cortex at the early phase of the RRY treatment. Future studies will focus on establishing delivery methods of nanoparticle of RRY in combination of high energy ultrasonography which allows RRY to open regional blood-brain barrier and increase penetration of RRY. Extending treatment of RRY for several months will be done to quantify change of Aβ accumulation in brain tissue, and the density of dendritic spines in the neurons of the dentate gyrus. More neurodegenerative disorder tests will be included, such as learning and memory ability.

In conclusion, current results indicated that RRY, a tri-peptide screened from consecutive studies of in silico, in vitro and in vivo experiments, can inhibit Aβ142 aggregation, prevent memory impairment, and increase synaptogenesis in the brain of the APP/PS1 Tg mouse. Current experimental findings also provided evidence that the tri-peptides have the potential to be used as therapeutic agents to diminish the progression of amyloidosis in AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the funds from the Guangdong Science and Technology Department (2012B090600019-SD), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (2011AA03A113-RL) and the 985 project of Sun Yat-sen University (90034e3283300-SD and RL). This work was in part supported by research grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number K08AA024895-Qi Cao; R01AA028995-01-Liya Pi). We are very thankful to Professor Jun Xu for providing the software for the MD simulation, and to Mr. Shaoliang Fang for providing the supercomputer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Huang Y, Mucke L (2012) Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Hardy J, Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ (2008) Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Sciarretta KL, Gordon DJ, Meredith SC (2006) Peptide-based inhibitors of amyloid assembly. Methods Enzymol 413, 273–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kawasaki T, Kamijo S (2012) Inhibition of aggregation of amyloid β42 by arginine-containing small compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76, 762–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Lemkul JA, Bevan DR (2012) The role of molecular simulations in the development of inhibitors of amyloid β-peptide aggregation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci 3, 845–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Novick PA, Lopes DH, Branson KM, Esteras-Chopo A, Graef IA, Bitan G, Pande VS (2012) Design of β-amyloid aggregation inhibitors from a predicted structural motif. J Med Chem 55, 3002–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Duffy FJ, Verniere M, Devocelle M, Bernard E, Shields DC, Chubb AJ (2011) CycloPs: Generating virtual libraries of cyclized and constrained peptides including nonnatural amino acids. J Chem Inf Model 51, 829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Crescenzi O, Tomaselli S, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, D’Ursi AM, Temussi PA, Picone D (2002) Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide (1-42) in an apolar microenvironment. Similarity with a virus fusion domain. Eur J Biochem 269, 5642–5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Trott O, Olson AJ (2010) AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ (2005) The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem 26, 1668–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong G, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang J, Kollman P (2003) A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J Comput Chem 24, 1999–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Jorgensen W, Chandrasekhar J, Madura J, Impey R, Klein M (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Gaussian Revision C, LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S (2007) Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 8, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell W, Kollman PA (1993) A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: The RESP model. J Phys Chem 97, 10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Wang J, Wolf R, Caldwell J, Kollman P, Case D (2004) Development and testing of a general AMBER force field. J Comput Chem 25, 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Darden T, York D, Pedersen L (1993) Particle mesh Ewald: An N.log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys (USA) 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen H (1977) Numerical-integration of cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints –molecular-dynamics of N-alkanes. J Comput Phys 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Fogolari F, Brigo A, Molinari H (2003) Protocol for MM/PBSA molecular dynamics simulations of proteins. Biophys J 85, 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Agrawal P, Sudalayandi B, Raff L, Komanduri R (2008) Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the dependence of C–C bond lengths and bond angles on the tensile strain in single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT). Comput Mater Sci 41, 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Srinivasan J, Cheatham TE, Cieplak P, Kollman PA, Case DA (1998) Continuum solvent studies of the stability of DNA, RNA, and phosphoramidate-DNA helices. J Am Chem Soc 120, 9401–9409. [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Lee C, Ham S (2011) Characterizing amyloid-beta protein misfolding from molecular dynamics simulations with explicit water. J Comput Chem 32, 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Yang C, Zhu X, Li J, Shi R (2010) Exploration of the mechanism for LPFFD inhibiting the formation of beta-sheet conformation of A beta(1-42) in water. J Mol Model 16, 813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Daura X, van Gunsteren WF, Mark AE (1999) Folding-unfolding thermodynamics of a beta-heptapeptide from equilibrium simulations. Proteins 34, 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC (2005) GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem 26, 1701–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. LeVine H, 3rd (1993) Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptides: Detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci 2, 404–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Sreerama N, Woody RW (2004) Computation and analysis of protein circular dichroism spectra. Methods Enzymol 383, 318–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. DeVos SL, Miller TM (2013) Direct intraventricular delivery of drugs to the rodent central nervous system. J Vis Exp, e50326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [29]. Vorhees CV, Williams MT (2006) Morris water maze: Procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc 1, 848–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Ziv Y, Ron N, Butovsky O, Landa G, Sudai E, Greenberg N, Cohen H, Kipnis J, Schwartz M (2006) Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood. Nat Neurosci 9, 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Liu L, Duff K (2008) A technique for serial collection of cerebrospinal fluid from the cisterna magna in mouse. J Vis Exp, 960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [32]. O’Brien JA, Lummis SCR (2006) Diolistic labeling of neuronal cultures and intact tissue using a hand-held gene gun. Nat Protoc 1, 1517–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Seabold GK, Daunais JB, Rau A, Grant KA, Alvarez VA (2010) DiOLISTIC labeling of neurons from rodent and non-human primate brain slices. J Vis Exp, 2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [34]. Viet MH, Ngo ST, Lam NS, Li MS (2011) Inhibition of aggregation of amyloid peptides by beta-sheet breaker peptides and their binding affinity. J Phys Chem B 115, 7433–7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R (2005) 3D structure of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta(1-42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 17342–17347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Tarus B, Straub JE, Thirumalai D (2006) Dynamics of Asp23-Lys28 salt-bridge formation in Abeta10-35 monomers. J Am Chem Soc 128, 16159–16168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Thal DR, Walter J, Saido TC, Fändrich M (2015) Neuropathology and biochemistry of Aβ and its aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 129, 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Han YS, Zheng WH, Bastianetto S, Chabot JG, Quirion R (2004) Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against amyloid-beta-induced neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons: Involvement of protein kinase C. Br J Pharmacol 141, 997–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Hetényi C, Körtvélyesi T, Penke B (2001) Computational studies on the binding of β-sheet breaker (BSB) peptides on amyloid βA(1–42). J Mol Struct Theochem 542, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Soto C, Sigurdsson EM, Morelli L, Kumar RA, Castaño EM, Frangione B (1998) Beta-sheet breaker peptides inhibit fibrillogenesis in a rat brain model of amyloidosis: Implications for Alzheimer’s therapy. Nat Med 4, 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Tjernberg LO, Näslund J, Lindqvist F, Johansson J, Karlström AR, Thyberg J, Terenius L, Nordstedt C (1996) Arrest of amyloid-beta fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J Biol Chem 271, 8545–8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, Elliott JI, Van Nostrand WE, Smith SO (2010) Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1-42) oligomers to fibrils. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17, 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Hamilton A, Holscher C (2012) The effect of ageing on neurogenesis and oxidative stress in the APP(swe)/PS1(deltaE9) mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 1449, 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Yu Y, He J, Zhang Y, Luo H, Zhu S, Yang Y, Zhao T, Wu J, Huang Y, Kong J, Tan Q, Li XM (2009) Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in the progressive stage of Alzheimer’s disease phenotype in an APP/PS1 double transgenic mouse model. Hippocampus 19, 1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B (2011) The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: An appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10, 698–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Reitz C (2012) Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid cascade hypothesis: A critical review. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 369808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S (2007) Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 8, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Mucke L, Selkoe DJ (2012) Neurotoxicity of amyloid βprotein: Synatic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Bayer T, Wirths O (2008) Review on the APP/PS1KI mouse model: Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation triggers axonopathy, neuron loss and working memory impairment. Genes Brain Behav 7(Suppl 1), 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Iijima K, Liu HP, Chiang AS, Hearn SA, Konsolaki M, Zhong Y (2004) Dissecting the pathological effects of human Abeta40 and Abeta42 in Drosophila: A potential model for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 6623–6628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Blennow K, Hampel H (2003) CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2, 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Shoji M, Matsubara E, Kanai M, Watanabe M, Nakamura T, Tomidokoro Y, Shizuka M, Wakabayashi K, Igeta Y, Ikeda Y, Mizushima K, Amari M, Ishiguro K, Kawarabayashi T, Harigaya Y, Okamoto K, Hirai S (1998) Combination assay of CSF Tau, Ab1-40 and Ab1-42(43) as a biochemical marker of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci 158, 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Koyama A, Okereke OI, Yang T, Blacker D, Selkoe DJ, Grodstein F (2012) Plasma amyloid-β as a predictor of dementia and cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Neurol 69, 824–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Schneider P, Hampel H, Buerger K (2009) Biological marker candidates of Alzheimer’s disease in blood, plasma, and serum. CNS Neurosci Ther 15, 358–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Bourne JN, Harris KM (2008) Balancing structure and function at hippocampal dendritic spines. Annu Rev Neurosci 31, 47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Dennis J, Selkoe DJ (2008) Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 142, 387-397. Nat Med 14, 837–842.18568035 [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Gouras GK, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E (2010) Intraneuronal amyloid-beta accumulation and synapse pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 119, 523–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Moolman DL, Vitolo OV, Vonsattel JPG, Shelanski ML (2004) Dendrite and dendritic spine alterations in Alzheimer models. J Neurocytol 33, 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Ermini FV, Grathwohl S, Radde R, Yamaguchi M, Staufenbiel M, Palmer TD, Jucker M (2008) Neurogenesis and alterations of neural stem cells in mouse models of cerebral amyloidosis. Am J Pathol 172, 1520–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Faure A, Verret L, Bozon B, Tannir E, Tayara N, Ly M, Kober F, Dhenain M, Rampon C, Delatour B (2011) Impaired neurogenesis, neuronal loss, and brain functional deficits in the APPxPS1-Ki mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 32, 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Kiyota T, Okuyama S, Swan RJ, Jacobsen MT, Gendelman HE, Ikezu T (2010) CNS expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-4 attenuates Alzheimer’s disease-like pathogenesis in APP+PS1 bigenic mice. FASEB J 24, 3093–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P (2005) Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci 8, 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63]. Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, Wölfing H, Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Napier IA, Eckert A, Staufenbiel M, Hardeman E, Götz J (2010) Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 142, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Olzscha H, Schermann SM, Woerner AC, Pinkert S, Hecht MH, Tartaglia GG, Vendruscolo M, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Vabulas RM (2011) Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell 144, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Lobello K, Ryan JM, Liu E, Rippon G, Black R (2012) Targeting Beta amyloid: A clinical review of immunotherapeutic approaches in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 628070–628070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66]. Molek P, Strukelj B, Bratkovic T (2011) Peptide phage display as a tool for drug discovery: Targeting membrane receptors. Molecules 16, 857–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Prabhakar R (2009) Computational insights into the development of novel therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Future Med Chem 1, 119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]