Abstract

Background: It is estimated that one in five people worldwide faces a diagnosis of a malignant neoplasm during their lifetime. Carvacrol and its isomer, thymol, are natural compounds that act against several diseases, including cancer. Thus, this systematic review aimed to examine and synthesize the knowledge on the antitumor effects of carvacrol and thymol.

Methods: A systematic literature search was carried out in the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Lilacs databases in April 2020 (updated in March 2021) based on the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The following combination of health descriptors, MeSH terms and their synonyms were used: carvacrol, thymol, antitumor, antineoplastic, anticancer, cytotoxicity, apoptosis, cell proliferation, in vitro and in vivo. To assess the risk of bias in in vivo studies, the SYRCLE Risk of Bias tool was used, and for in vitro studies, a modified version was used.

Results: A total of 1,170 records were identified, with 77 meeting the established criteria. The studies were published between 2003 and 2021, with 69 being in vitro and 10 in vivo. Forty-three used carvacrol, 19 thymol, and 15 studies tested both monoterpenes. It was attested that carvacrol and thymol induced apoptosis, cytotoxicity, cell cycle arrest, antimetastatic activity, and also displayed different antiproliferative effects and inhibition of signaling pathways (MAPKs and PI3K/AKT/mTOR).

Conclusions: Carvacrol and thymol exhibited antitumor and antiproliferative activity through several signaling pathways. In vitro, carvacrol appears to be more potent than thymol. However, further in vivo studies with robust methodology are required to define a standard and safe dose, determine their toxic or side effects, and clarify its exact mechanisms of action.

This systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020176736) and the protocol is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=176736.

Keywords: carvacrol, thymol, cancer, antitumor, anticancer

Introduction

It is estimated that one in five people worldwide faces the diagnosis of some malignant neoplasm during their lifetime, and the number of people with cancer is forecast to double by the year 2040 (World Health Organization, 2020). In fact, cancer is a major global public health problem, and it is one of the four main causes of premature death (before 70 years old) in most countries, resulting in 8.8 million deaths per year (National Cancer Institute, 2019). The antineoplastic agents available on the market have different mechanisms of action that impair cell proliferation and/or cause cell death, thereby increasing patient survival rate (Powell et al., 2014; Lee and Park, 2016). However, the toxicity and side effects of many treatments can worsen the quality of life of these individuals (Weingart et al., 2018; Hassen et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2019). Thus, despite being the subject of research for many years, cancer still remains a major concern and an important area of study in the search for a cure.

There is, therefore, an ongoing search for substances that can be used to develop more effective treatments, with less side effects, to use against cancer; one promising group of substances are natural products (NPs). There are many medicinal plants whose pharmacological properties have already been described and scientifically proven (Nelson, 1982; Mishra and Tiwari, 2011; Carqueijeiro et al., 2020). However, the enormous diversity of nature still holds many plant compounds without sufficient studies, particularly in the oncology area (Gordaliza, 2007; Asif, 2015). Historically, secondary plant metabolites have made important contributions to cancer therapy, such as, the vinca alkaloids (vinblastine and vincristine) and the paclitaxel terpene that was obtained from the Taxus brevifolia Nutt. species (Martino et al., 2018). More recently, other compounds, such as perillyl alcohol and limonene -monoterpenes found in aromatic plant species, have been widely studied due to their antitumor potential, and have been included in clinical phase studies (Shojaei et al., 2014; Arya and Saldanha, 2019).

In this context, carvacrol (5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) and its thymol isomer (2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol), classified as natural multi-target compounds, deserve attention. Both are monoterpenoid phenols, the main components present in essential oils obtained from several plant species of the Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae families, such as oregano (Origanum vulgare L.), thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) and “alecrim-da-chapada” (Lippia gracilis) (Santos et al., 2016; Salehi et al., 2018; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2018; Baj et al., 2020), which have already been reported to exhibit beneficial effects against many diseases (Silva et al., 2018), including cancer (Elbe et al., 2020; Pakdemirli et al., 2020). In addition, these compounds present anti-inflammatory (Li et al., 2018; Chamanara et al., 2019) and antioxidant (Arigesavan and Sudhandiran, 2015; Sheorain et al., 2019) activities that enable the reduction of inflammation and an increase in enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in the tumor environment (Gouveia et al., 2018). Hence, this systematic review aims to examine and synthesize knowledge about the antitumor and antiproliferative effect of carvacrol and thymol, as well as to report the main mechanisms of action already described for the two compounds against cancer. to provide guidance for future research.

Methods

Question and PICOS Strategy

The purpose of this systematic review was to answer the following question: Do carvacrol and thymol exhibit an anti-tumor effect on cancer cells (in vitro) or in animal models of cancer? The review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021).

A PICOS strategy (patient or pathology, intervention, control, and other outcomes and type of study) was used based on: P: Animals with cancer or tumor cells; I: Treatment with carvacrol or thymol; C: No treatment, healthy cells or placebo (vehicle); O: Cytotoxic and antitumor effects, induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation; S: Pre-clinical studies in vitro and in vivo.

Data Sources and Literature Search

The research was carried out in the databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Lilacs in April 2020 (updated in March 2021) using a combination of health descriptors, MeSH terms and their synonyms, such as antitumor, antineoplastic, anticancer, cytotoxicity, apoptosis, cell proliferation, in vitro, in vivo, carvacrol or 5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol and thymol or 5-methyl-2-propan-2-ylphenol (Supplementary Table S1, contains a complete list of these search terms).

Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

Two independent reviewers (L.A.S. and L.T.S.P.) analyzed the research results and selected potentially relevant studies after reading their title and abstract, using the systematic review application, Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). We used the Kappa statistical test to measure the inter-rater reliability (Landis and Koch, 1977). Disagreements were resolved through a consensus between the reviewers, and the decision was supported by the assistance of a third reviewer when necessary (AGG). The following inclusion criteria were applied: Administration of carvacrol or pure thymol vs. placebo; in vitro studies of cancer cell lines, in vivo study of animals with cancer; cytotoxic effect, antitumor effect, inhibition of proliferation and apoptosis and experimental studies (in vitro and in vivo). The exclusion criteria were: experiments with derivatives of the carvacrol or thymol, association of the two compounds with other substances or in mixtures composing essential oils and extracts, animals with other diseases in addition to cancer, review articles, meta-analyses, abstracts, conference articles, editorials/letters and case reports. A manual search of the reference lists of all selected studies was also conducted, in order to identify additional primary studies for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

We extracted the following data from the included articles: author, year, country, data about the monoterpene (source, obtention method), concentration and/or dose, type of animal or cell line, results (cytotoxicity, cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle, histology), proposed mechanisms involved in the antitumor effect and conclusion. The authors of the included studies were contacted when necessary (whenever any data or article was not available).

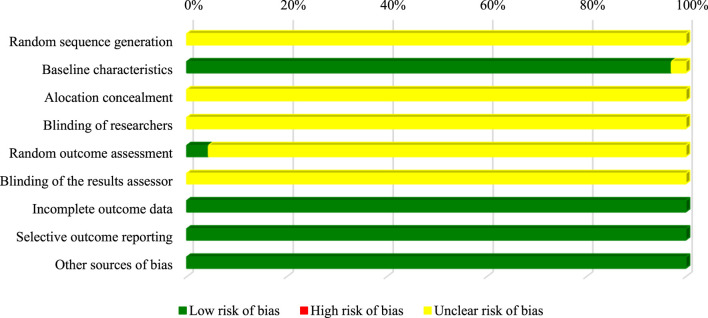

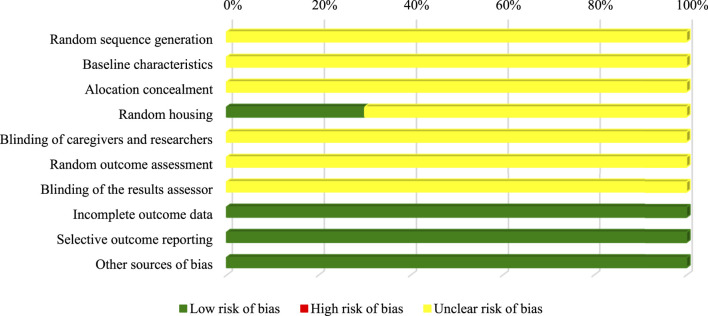

The SYRCLE Risk of Bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias of all in vivo experimental studies (Hooijmans et al., 2014). We analyzed the following ten domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment and random accommodation (selection bias), random accommodation and concealment (performance bias), random evaluation and concealment of results (detection bias), incomplete result data (bias of attrition), selective report of results (report bias) and other sources of bias, such as inappropriate influence from financiers. An adapted protocol of the SYRCLE Risk of Bias tool was used to evaluate the methodological quality of in vitro studies, as described by Chan et al. (2017). The methodological quality was classified as low, unclear or high, according to the established criteria (Hooijmans et al., 2014).

Statistical Analysis

IC50 values determined 24 h after the incubation of the studied cells with carvacrol or thymol were compiled, submitted to the standardization of the unit (μM) (Supplementary Table S2) and were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Study Selection

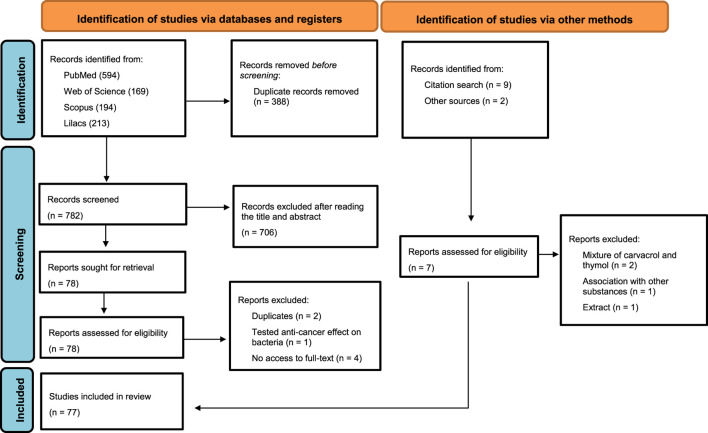

The initial search resulted in 1,170 records, of which 594, 169, 194, and 213 were found in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Lilacs, respectively. Of these, 388 were excluded due to duplication. After screening the title and abstract, 706 reports were excluded, and 1 report was sought for retrieval, as it met the criteria after reading the full text, resulting in 77 studies. Of these, three were excluded after reading the full text (two for presenting the same results and one that tested the anti-cancer effect on bacteria) and four for not having access to the full text, resulting in 70 articles. In addition, 9 studies were identified after a manual search of the references and two studies obtained from other sources, but only seven studies were added (two studies were excluded for having a mixture between carvacrol and thymol, one for being associated with other substances, and one that studied the extract of a plant rich in thymol), finally resulting in 77 included studies (Figure 1). There was almost perfect (Landis and Koch, 1977) reliability/agreement (κ = 0.813) among the reviewers, after selecting the titles and abstracts.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of included studies.

Overview of Included Studies

The selected studies were carried out in different countries: India (n = 14), China (n = 14), Turkey (n = 13), the Republic of Korea (n = 5), Slovakia (n = 5), Iran (n = 5), Morocco (n = 2), Brazil (n = 2), Greece (n = 2), Iraq (n = 2), The United States of America (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), Egypt (n = 2), Croatia (n = 1), Lithuania (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), The United Kingdom (n = 1), Peru (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1). Asia (51.9%) was the continent with the largest number of publications on the subject, followed by Europe (33.7%), the Americas (9.3%) and Africa (5.1%), with a greater trend of publications on this subject in the last three years (Supplementary Figure S1). Among the selected articles, 69 (89.6%) reported in vitro experiments and 10 (12.9%) were in vivo studies. Likewise, 43, 19, and 15 publications tested only carvacrol, thymol and both compounds, respectively. They were mostly obtained commercially, provided by Sigma Aldrich (n = 52), Fluka (n = 5), Aldrich Chemical (n = 2), Western Chemical (n = 1), Agolin SA (n = 1), Alfa Aesar (n = 1). In only five studies were the compounds isolated from essential oils. Remarkably, ten studies did not report the source of the tested compounds. A detailed description of the included studies is shown in Tables 1 and 2. A narrative summary of the results is presented below, divided into in vitro and in vivo studies.

TABLE 1.

Detailed description of the studies that used carvacrol, included in the systematic review.

| Model | Concentration/incubation time | Experimental methods for testing IC50 values | Results/targets | Conclusion | Authors (Year), Country | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Decrease | IC50 | |||||

| Monoterpene carvacrol | |||||||

| In vitro studies | |||||||

| CO25 | 1–150 μg/mL | MTT assay | p21N−ras | Tumor growth | 60 μg/mL–24 h | Carvacrol has a cytotoxic effect and an antiproliferative effect | Zeytinoglu et al. (2003), Turkey |

| 24, 48, 72 h of incubation | DNA synthesis level | ||||||

| A549 | 100–1,000 μM | — | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol may have an anticancer effect and be used as a drug substance to cure cancer | Koparal and Zeytinoglu (2003), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | Cell proliferation | ||||||

| HepG2 | 25–900 μmol | — | Cytotoxic effects | DNA damage level | — | HepG2 cells were slightly more sensitive to the effects | Horváthová et al. (2006), Slovakia |

| Caco-2 | 24 of incubation | ||||||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 10–4,000 μM | Trypan Blue | Antiproliferative effects | Cell growth | 90 μM–24 h | Carvacrol has anticarcinogenic, antiproliferative and antiplatelet properties | Karkabounas et al. (2006), Greece |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | 67 μM–48 h | ||||||

| K-562 | 200–1,000 μM | Trypan blue exclusion | Cytotoxic effects | DNA damage level | 220 μM–24 h | Carvacrol has cytotoxic, antioxidant effects and has a protective action against DNA damage | Horvathova et al. (2007), Slovakia |

| 24 or 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| P-815 | 0.004–0.5% v/v | MTT assay | — | — | <0.004% v/v–48 h | Carvacrol is cytotoxic | Jaafari et al. (2007), Morocco |

| 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| HepG2 | 100–1,000 μM | Trypan blue exclusion | Cytotoxic effects | Cell proliferation | HepG2 - 350 μM–24 h | Carvacrol has antiproliferative and antioxidant effects | Slamenová et al. (2007), Slovakia |

| Caco-2 | 24 h of incubation | Caco-2 - 600 μM–24 h | |||||

| MDA-MB 231 | 20–100 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell growth | 100 μM–48 h | Carvacrol can be a potent antitumor molecule against breast cancer metastatic cells | Arunasree, (2010), India |

| Caspase activation | S-phase cells | ||||||

| 24 or 48 h of incubation | Sub-stage G0/G1 | Mitochondrial membrane potential | |||||

| Cyt C | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Bax | |||||||

| 5RP7 | 0.0002–0.1 mg/mL | MTT assay and Trypan Blue exclusion | Cytotoxic effects | — | 5RP7 - 0.04 mg/mL–24/48 h | Carvacrol promoted a cytotoxic effect, induced apoptosis and can be used in cancer therapy | Akalin and Incesu, (2011), Turkey |

| CO25 | 24 or 48 h of incubation | Apoptotic cells | CO25–0.1 mg/mL–24 h | ||||

| 0.05 mg/mL–48 h | |||||||

| SiHa | 25–500 μg/mL | MTT and LDH assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | SiHa - 50 ± 3.89 mg/L | Carvacrol is a potent anticancer compound that exhibits cytotoxic effects and induces the inhibition of cell proliferation in both human cervical cancer cells | Mehdi et al. (2011), India |

| HeLa | 48 h of incubation | HeLa - 50 ± 5.95 mg/L | |||||

| HepG2 | 20–200 μg/mL | CellTiter-Blue® cell viability assay | Cytotoxic effects | Membrane damage | 53.09 μg/mL | Carvacrol exhibits antioxidant activity and anticancer effects on cells | Özkan and Erdogan (2011), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | Antiproliferative effects | Cell viability | |||||

| P-815 | 0.05–1.25 μM | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Interruption of cell cycle progression in the S phase | P-815–0.067 μM | Carvacrol showed a cytotoxic effect in all strains tested | Jaafari et al. (2012), Morocco |

| CEM | CEM - 0.042 μM | ||||||

| K-562 | 48 h of incubation | K-562–0.067 μM | |||||

| MCF-7 | MCF-7 - 0.125 μM | ||||||

| MCF-7 gem | MCF-7 gem - 0.067 μM | ||||||

| DBTRG-05MG | 200–1,000 μM | — | Generation of ROS | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol was cytotoxic and induced cell death in human glioblastoma cells | Liang and Lu, (2012), China |

| 24 h of incubation | Caspase-3 | ||||||

| H1299 | 25–1800 μM | CellTiter-Blue® cell viability assay | MDA | Membrane and DNA damage | 380 μM–24 h | Carvacrol exhibited cytotoxic and antioxidant effects | Ozkan and Erdogan (2012), Turkey |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | 8-OHdG | 244 μM–48 h | |||||

| B16-F10 | Not reported | Trypan blue assay and MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 550 μM | Carvacrol showed an antitumor effect with moderate cytotoxicity | Satooka and Kubo (2012), United States |

| 24 h of incubation | Relative melanogenesis | ||||||

| Relative melanin cell | |||||||

| HepG2 | 0.05–0.4 mmol/L | MTT assay | p-p38 | Cell viability | 0.4 mmol/L–24 h | Carvacrol caused inhibition of cell proliferation, inhibition of tumor cell growth and induction of apoptosis | Yin et al. (2012), China |

| 24 h of incubation | MAPK | p-ERK 1/2 | |||||

| Caspase-3 | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| OC2 | 200–1,000 μM | — | Generation of ROS | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol exhibited a cytotoxic effect and induced apoptosis in human oral cancer cells | Liang et al. (2013), China |

| 24 h of incubation | Caspase-3 | ||||||

| MCF-7 | 140–450 μM | MTT and LDH assay | Caspase-3, -6 and -9 | Cell viability | 244.7 ± 0.71μM–48 h | Carvacrol induces cytotoxicity and apoptosis in MCF-7 cells and may be a potential chemotherapeutic agent against cancer | Al-Fatlawi and Ahmad (2014), India |

| 24 and 48 of incubation | Bax | Bcl-2 | |||||

| p53 | |||||||

| N2a | 10–400 mg/L | — | TAC | — | — | Carvacrol has antioxidant and anticancer properties in N2a cells at concentrations of 200 and 400 mg/L | Aydın et al. (2014), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | TOS | ||||||

| Caco-2 | 100–2,500 μM | MTS assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 460 ± 3.6 μM–24 h | Carvacrol exhibited cytotoxic effects and induction of apoptosis | Llana-Ruiz-Cabello et al. (2014), Spain |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | 343 ± 7.4 μM–48 h | ||||||

| HepG2 | 25–1,000 μM | Trypan Blue exclusion and MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell growth | 425 μM–24 h | Carvacrol can be used as an anti-tumor molecule against cancer cells | Melusova et al. (2014), Slovakia |

| 24 h of incubation | SsDNA breaks | ||||||

| Oxidative DNA lesions | |||||||

| HepG2 | 100–600 μM | — | Cells in G1 phase | S-phase cells | — | Carvacrol caused induction of apoptosis and slowed cell division, resulting in cell death | Melušová et al. (2014), Slovakia |

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| U87 | 125–1,000 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 561.3 μM–24 h | Carvacrol has therapeutic potential for the treatment of glioblastomas by inhibiting TRPM7 channels | Chen et al. (2015), Canada |

| 24, 48 or 72 h of incubation | Caspase-3 | Cell proliferation | |||||

| PI3K/Akt | |||||||

| MAPK | |||||||

| TRPM7 | |||||||

| MMP-2 | |||||||

| HCT116 | 100–900 μmol/L | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell growth | HCT116–544.4 μmol/L–48 h | Carvacrol can be a promising natural product in the management colon cancer | Fan et al. (2015), China |

| LoVo | 48 h of incubation | Cell migration and invasion | |||||

| Bcl-2 | |||||||

| Bax | MMP-2 and -9 | LoVo - 530.2 μmol/L–48 h | |||||

| Cyclin B1 | |||||||

| p-ERK | |||||||

| p-JNK | p-Akt | ||||||

| PI3K/Akt | |||||||

| Cell cycle stop in phase G2/M | |||||||

| AGS | 0.01–6 mg/mL | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 30 μg/mL–48 h | Carvacrol exhibited a cytotoxic effect against gastric cancer cells | Maryam et al. (2015), Iran |

| 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| HL-60 | 10–200 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | HL-60–100 μM–24 h | Carvacrol effectively blocked the proliferation of cancer cells in vitro | Bhakkiyalakshmi et al. (2016), India |

| Jurkat | 24 h of incubation | Cytotoxic effects | MMP | Jurkat - 50 μM–24 h | |||

| Generation of ROS | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Caspase-3 | |||||||

| Bax | |||||||

| Tca-8113 | 10–80 μM | — | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | — | Carvacrol is a powerful new natural anti-cancer drug for human OSCC | Dai et al. (2016), China |

| SCC-25 | 24 and 48 h of incubation | S-Phase cells | |||||

| p21 | CCND1 | ||||||

| CDK4 | |||||||

| Bcl-2 | |||||||

| Bax | MMP-2 and -9 | ||||||

| COX-2 | |||||||

| A549 | 1–1,000 μM | SRB assay | Antiproliferative effects | — | A549–0.118 ± 0.0012 mΜ–72 h | Carvacrol exhibited antiproliferative and antioxidant effects. In addition, it exhibited more potent cytotoxicity against cells (A549). The cells (Hep3B) were more resistant to treatment and the cells (HepG2) were less sensitive | Fitsiou et al. (2016), Greece |

| HepG2 | 72 h of incubation | Cytotoxic effects | HepG2 - 0.344 ± 0.0035 mΜ–72 h | ||||

| Hep3B | Hep3B- 0.234 ± 0.017 mΜ–72 h | ||||||

| PC-3 | 250–750 μM | CCK-8 Kit | — | Cell viability | PC-3 - 498.3 ± 12.2 μM–24 h | Carvacrol treatment suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion, indicating that it has antiprostatic effects in vitro | Luo et al. (2016), China |

| DU 145 | 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation | Cell proliferation | DU 145–430.6 ± 21.9 μM–24 h | ||||

| Cell migration | |||||||

| Wound healing | |||||||

| MMP-2 | |||||||

| PI3K/Akt and MAPK | |||||||

| Cell invasion | |||||||

| TRPM7 | |||||||

| A549 | 0–250 μM | — | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol has cytotoxic activity | Coccimiglio et al. (2016), Canada |

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| U87 | 1–10,000 μM | MTT assay | Anticancer activity | — | U87–322 μM–24 h | Carvacrol exerted anticancer and antiproliferative activity with greater effect against the breast cancer cell line | Baranauskaite et al. (2017), Lithuania |

| MDA-MB 231 | 24 h of incubation | Antiproliferative activity | MDA-MB 231–199 μM–24 h | ||||

| Antioxidant activity | |||||||

| HepG2 | 0.01–0.25 μg/μL | MTT assay | — | Cell viability | 48 mg/L–24 h | Carvacrol has therapeutic potential in tumor cells without adverse effects in healthy cells | Elshafie et al. (2017), Italy |

| 24 h of incubation | Hepatocarcinoma cells | ||||||

| PC-3 | 100–800 μM | — | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol is cytotoxic | Horng et al. (2017), China |

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| DU 145 | 10–500 μM | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 84.39 μM–24 h | Carvacrol has antiproliferative potential and can act as a chemopreventive agent in prostate cancer | Khan et al. (2017), India |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | 42.06 μM–48 h | ||||

| Caspase-3 | Mitochondrial membrane potential | ||||||

| Generation of ROS | Cell cycle stop | ||||||

| Cells in phase G0/G1 | Cells in S and G2/M phases | ||||||

| SiHa | 140–450 μM | MTT assay and LDH | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | SiHa - 424.22 μmol –24 h and 339.13 μmol–48 h | Carvacrol exhibited antiproliferative effects and may be a potential chemotherapeutic agent against cancer | Abbas and Al-Fatlawi (2018), Iraq |

| HepG2 | 24 and 48 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | Bcl-2 | ||||

| Caspase-3, -6 and -9 | HepG2 - 576.52 μmol –24 h and 415.19 μmol –48 h | ||||||

| Bax | |||||||

| p53 | |||||||

| A375 | 3.906–1,000 μg/mL | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 40.41 ± 0.044 μg/mL–24 h | Carvacrol exhibits antiproliferative effects | Govindaraju and Arulselvi (2018), India |

| 24 of incubation | Sub-G1 phase | Cell growth | |||||

| Bcl-2 | |||||||

| Cell cycle stop | |||||||

| Cells in phase G0/G1 and G2/M | |||||||

| AGS | 10–600 µM | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent cell viability assay | Apoptotic effects | Cell viability | 82.57 ± 5.58 µM–24 h | Carvacrol has cytotoxic effects, apoptotic, genotoxic effects and dose-dependent ROS generators | Günes-Bayir et al. (2018), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | Necrosis | Bcl-2 | |||||

| Bax | |||||||

| Caspase-3 and -9 | |||||||

| Generation of ROS | GSH levels | ||||||

| Genotoxic effect | |||||||

| AGS | 10–600 µM | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent cell viability assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 82.57 ± 5.5 μM–48 h | Carvacrol inhibited cell proliferation and induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells | Günes-Bayir et al. (2018), Turkey |

| 48 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | Bcl-2 | |||||

| Bax | |||||||

| Caspase-3 e -9 | |||||||

| Generation of ROS | GSH levels | ||||||

| Genotoxic effect | |||||||

| MCF-7 | 10–200 μg/mL | MTT assay | — | Cell viability | MCF-7 - 46.5 μg/mL–24 h | Carvacrol has a cytotoxic effect and can cause inhibition of cell growth | Jamali et al. (2018), Iran |

| MDA-MB 231 | 24 h of incubation | MDA-MB 231–53 μg/mL– 24 h | |||||

| A549 | 30–300 μM | — | — | Cell viability | - | Carvacrol suppressed cell proliferation and migration and its inhibitory effect was attenuated in NSCLC cells with overexpression of AXL | Jung et al. (2018), Republic of Korea |

| H460 | 24 h of incubation | Cell proliferation | |||||

| AXL expression | |||||||

| Cell migration | |||||||

| JAR | 50–300 μM | — | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | — | Carvacrol may be a possible new therapeutic agent or supplement for the control of human choriocarcinomas | Lim et al. (2019), Republic of Korea |

| JEG3 | 48 h of incubation | Sub-G1 phase | Cell viability | ||||

| Generation of ROS | PI3K/AKT | ||||||

| p-JNK | p-ERK1/2 | ||||||

| p-p38 | MMP | ||||||

| HeLa | 100–800 µM | XTT Reduction assay | Induction of cytotoxicity and apoptosis | Cyclin D1 | 556 ± 39 μM–24 h | Carvacrol can be used to treat cervical cancer, however, it should be avoided during cisplatin chemotherapy | Potočnjak et al. (2018), Croatia |

| 24 h of incubation | ERK1/2 | ||||||

| Caspase-9 | |||||||

| p21 | |||||||

| PC-3 | 100–800 μM | MTT assay | Cell death | Cell viability | 360 μM–48 h | Carvacrol inhibited the ability to invade and migrate PC3 cells and can be considered an anticancer agent | Heidarian and Keloushadi (2019), Iran |

| 48 h of incubation | Cell proliferation | ||||||

| Tumor cell invasion | |||||||

| IL-6 | |||||||

| p-STAT3 | |||||||

| p-ERK1/2 | |||||||

| p-AKT | |||||||

| PC-3 | 10–500 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 46.71 μM–24 h | Carvacrol is a chemopreventive agent and has an antiproliferative effect on prostate cancer cells | Khan et al. (2019), India |

| Caspases -8 e -9 | Cell proliferation | ||||||

| Cell migration | |||||||

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | Generation of ROS | Cell cycle stop at G0/G1 | 39.81 μM–48 h | ||||

| Cells in S and G2/M phases Bcl-2 | |||||||

| Bax | Notch-1 | ||||||

| mRNA Jagged-1 | |||||||

| MCF-7 | 31.2–500 μg/mL | AlamarBlue® assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | MCF-7 - 266.8 μg/mL–48 h | Carvacrol had the most cytotoxic effect among the other components studied | Tayarani-Najaran et al. (2019), Iran |

| PC-3 | 48 h of incubation | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | PC-3 - >500 μg/mL– 48 h | |||

| DU 145 | Bax | DU 145–21.11 μg/mL– 48 h | |||||

| PC-3 | 25–200 μg/mL | — | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | — | At the lowest concentration tested (25 μg/ml), carvacrol did not exhibit cytotoxicity to cancer cells | Trindade et al. (2019), Brazil |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| HCT116 | 25–200 μM | xCELLigence Real-time cell Analysis | — | Cell proliferation | HCT116–92 μM–48 h | Carvacrol has an antiproliferative effect on both cell lines, but is more efficient against HT-29 compared to the HCT116 cell line | Pakdemirli et al. (2020), Turkey |

| HT-29 | 48 h of incubation | HT-29–42 μM–48 h | |||||

| MCF-7 | 25–250 μmol/L | MTT and LDH assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 200 μmol/L–24/48 h | Carvacrol can be used in a new approach for the treatment of breast cancer | Mari et al. (2020), India |

| Cells in phase G0/G1 | Cells in S and G2 phase | ||||||

| CDK4 and 6 | |||||||

| 24 and 48 of incubation | Cyclin D1 | ||||||

| Bax | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| PI3K/p-AKT | |||||||

| SKOV-3 | 100, 200, 400, 600 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 322.50 µM–24 h | Carvacrol was cytotoxic to the ovarian cancer cell line | Elbe et al. (2020), Turkey |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | 289.54 µM–48 h | ||||||

| Kelly | 12.5, 25, 50 µM | — | Antiproliferative effects | — | — | Carvacrol can be used to inhibit neuroblastoma cell proliferation | Kocal and Pakdemirli (2020), Turkey |

| SH-SY5Y | 24 h of incubation | ||||||

| BT-483 | 25–500 μM | — | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | — | Carvacrol suppresses breast cancer cells by regulating the cell cycle and the TRPM7 pathway is one of the pharmacological mechanisms | Li et al. (2021), China |

| BT-474 | Cells in G1/G0 phase | S-phase and G2/M cells | |||||

| MCF-7 | 24 h of incubation | Cyclin C, D and E | Cell proliferation | ||||

| MDA-MB 231 | Cyclin A e B | ||||||

| MDA-MB 453 | CDK 4 | ||||||

| KG1 | 100, 200, 300, 400 μM | — | Cell death | Cell viability | — | KG1 cell lines were very sensitive to 300 µM carvacrol compared to the HL60 line, while the K562 line showed resistance after 48 h of treatment with 400 µM carvacrol | Bouhtit et al. (2021), Belgium |

| K-562 | 24 and 48 h of incubation | ||||||

| HL-60 | |||||||

| Model | Dose | Results/targets | Conclusion | Authors (Year), Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Decrease | ||||

| In vivo studies | |||||

| Chemical carcinogenesis induced by B [a]P in male wistar rats | 20 mL of carvacrol (ε = 976 mg/mL) mixed with 200mg of B [a]P | Anticarcinogenic effects | 30% tumor incidence | Carvacrol has anticarcinogenic, antiproliferative and antiplatelet properties | Karkabounas et al. (2006), Greece |

| Animal survival time | B [a]P carcinogenic potency | ||||

| Male wistar rats induced with hepatocarcinogenesis providing 0.01% DEN through drinking water for 16 weeks | Pre-treatment: (15 mg/kg b.wt) of carvacrol orally one week before DEN administration and up to 16 weeks | Final body weight | Pre-treatment: Number of nodules; neoplastic transformations; liver weight | Carvacrol has the ability to cause apoptosis in cancer cells and has a potent elimination of free radicals and antioxidant activities | Jayakumar et al. (2012), India |

| Post-treatment: (15 mg/kg b.wt) of carvacrol orally for 6 weeks after administration of DEN for 10 weeks | Chemopreventive effect apoptosis induction | Post-treatment: Persistent but tiny nodules; architecture; | |||

| GPx, GR, GSH, SOD, CAT | Likely to spread through intrahepatic veins | ||||

| AST, ALT, ALP, LDH, cGT | |||||

| Liver carcinogenesis chemically induced by NDEA in male wistar rats orally (dissolved in 0.9% normal saline), in a dose of 20 mg/kg body weight, five times a week, for 6 weeks | 15 mg/kg of carvacrol orally, five times a week for 15 weeks, after NDEA administration for 6 weeks | Antiproliferative effect | AFP | Carvacrol may have an antitumor effect through its antiangiogenic capacity, antiproliferative effect and apoptotic activity against tumor cells in vivo | Ahmed et al. (2013), Egypt |

| Apoptosis induction | VEGF | ||||

| Marked improvement in histological characteristic of liver tissue | AFU | ||||

| GGT | |||||

| Male wistar rats induced with hepatocarcinogenesis providing 0.01% DEN through drinking water for 16 weeks | Pre-treatment: (15 mg/kg b.wt) of carvacrol orally one week before DEN administration and up to 16 weeks | — | Cell proliferation | Carvacrol attenuates hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting cell proliferation and tumor metastases | Subramaniyan et al. (2014), India |

| Post-treatment: (15 mg/kg b.wt) of carvacrol orally for 6 weeks after administration of DEN for 10 weeks | Tumor markers | ||||

| Mast cell density | |||||

| PCNA | |||||

| MMP-2 and -9 | |||||

| AgNORs | |||||

| DMH-induced colon carcinogenesis in male Wistar rats who received subcutaneous injections of DMH (20 mg/kg b.wt) in the right thigh, once a week for the first 4 weeks of the experiment (four injections) | 20, 40 or 80 mg/kg every day from the day of the carcinogen treatment till the end of the 16th week | Weight gain | Incidence of tumors | Carvacrol has antiproliferative, anticarcinogenic and chemopreventive potential and its effects were better observed at a dose of 40 mg/kg b.wt | Sivaranjani et al. (2016), India |

| Growth rate | Growth of neoplastic polyps | ||||

| GPx, GR, GSH, SOD, CAT | |||||

| C57BL/6 mice induced with DEN hepatocellular carcinoma injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 mg/kg | — | Intrastromal and peritumor lymphocytes | Tumor growth | The direct regulation relationship between DAPK1 and PPP2R2A may be the biological mechanism of tumorigenesis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma | Li et al. (2019), China |

| Intragastrically | DAPK1 | Tumor cells | |||

| 20 weeks | Mitotic phase | ||||

| PPP2R2A | |||||

| DMBA-induced breast cancer in female Holztman mice in a single administration of DMBA by oral gavage at a dose of 80 mg /kg body weight | 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg/day | Tumor latency | Number of tumors | Carvacrol had an antitumor effect on breast cancer in vivo and it is likely that this effect may be due to its antioxidant activity | Rojas-Armas et al. (2020), Peru |

| Oral gavage | 75% in the frequency of tumors | ||||

| 14 weeks | 67% in the incidence of tumors | ||||

| Average volume | |||||

TABLE 2.

Detailed description of the studies that used thymol, included in the systematic review.

| Model | Concentration/Incubation time | Experimental methods for testing IC50 values | Results/targets | Conclusion | Authors (Year), Country | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Decrease | IC50 | |||||

| Monoterpene thymol | |||||||

| In vitro studies | |||||||

| HepG2 | 150–900 μmol | – | Cytotoxic effects | DNA damage level | – | HepG2 cells were slightly more sensitive to the effects | Horváthová et al. (2006), Slovakia |

| Caco-2 | 24 of incubation | ||||||

| K-562 | 200, 400, 600, 800, 1,000 μM | Trypan blue exclusion | Cytotoxic effects | DNA damage level | 500 μM–24 h | Thymol has cytotoxic, antioxidant effects and has a protective action against DNA damage | Horvathova et al. (2007), Slovakia |

| 24 or 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| P-815 | 0.004–0.5% v/v | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | – | 0.015% v/v–48 h | Thymol is cytotoxic | Jaafari et al. (2007), Morocco |

| 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| HepG2 | 150–1,000 μM | Trypan blue exclusion | Cytotoxic effects | Cell proliferation | HepG2 - 400 μM–24 h | Thymol has antiproliferative and protective effects | Slamenová et al. (2007), Slovakia |

| Resistance to harmful DNA effects (antioxidant properties) | |||||||

| Caco-2 | 24 of incubation | Caco-2 - 700 μM–24 h | |||||

| HeLa | 15, 30.5, 61, 122, 244 ng/mL | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell survival | – | Thymol has strong antitumor activity against the HeLa cell line | Abed, (2011), Iraq |

| Hep | 72 h of incubation | ||||||

| MG63 | 100, 200, 400, 600 μmol/L | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Thymol showed antitumor activity in MG63 cells, moreover, its apoptotic effect is related to the pronounced antioxidant activity | Chang et al. (2011), China |

| 24 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | ||||||

| Generation of ROS | |||||||

| HL-60 | 5, 25, 50, 75, 100 μM | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Apoptosis induced by thymol in HL-60 cells involves the dependent and independent pathways of caspase | Deb et al. (2011), India |

| 24 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | Cells in phases G0/G1, S and G2/M | |||||

| Cells in sub phase G0/G1 generation of ROS | Cell cycle stop in phase G0/G1 Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Caspase-9, -8 and -3 | |||||||

| DBTRG-05MG | 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 800 μM | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Thymol induces cell death in human glioblastoma cells | Hsu et al. (2011), China |

| Apoptosis induction and necrosis | |||||||

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| HepG2 | 20–200 μg/mL | CellTiter-Blue® cell viability assay | Cytotoxic effects | Membrane damage | 60.01 μg/mL–24 h | Thymol exhibits antioxidant activities and anti-cancer effects on cells | Özkan and Erdogan, (2011), Turkey |

| Antiproliferative effects | |||||||

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| P-815 | 0.05–1.25 μM | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell cycle stop in phase G0/G1 | P-815–0.15 μM–48 h | Thymol showed relevant cytotoxic effects in all tested strains | Jaafari et al. (2012), Morocco |

| CEM | 48 h of incubation | CEM - 0.31 μM–48 h | |||||

| K-562 | K-562–0.44 μM–48 h | ||||||

| MCF-7 | MCF-7 - 0.48 μM–48 h | ||||||

| MCF-7gem | MCF-7gem - | ||||||

| H1299 | 10–2,000 μM | CellTiter-Blue® cell viability assay | Cytotoxic effects | Membrane and DNA damage | 497 μM–24 h | Thymol exhibited a cytotoxic and antioxidant effect | Ozkan and Erdogan, (2012), Turkey |

| 24 and 48 of incubation | MDA | 266 μM–48 h | |||||

| 8-OHdG | |||||||

| B16-F10 | 75, 150, 300, 600, 1,200 μM | Trypan blue and MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 400 μM | Thymol showed antitumor effect with moderate cytotoxicity | Satooka and Kubo, (2012), United States |

| 24 h of incubation | Generation of ROS | ||||||

| Density of melanoma cells | |||||||

| HepG2 | 1.56–50 μg/mL | Trypan blue assay | Cytotoxicity only for B16-F10 cells | – | HepG2 - > 25 μg/mL | Thymol showed cytotoxicity to B16-F10 cells | Ferraz et al. (2013), Brazil |

| K-562 | 72 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction in HepG2 cells | K-562–72 h | ||||

| B16-F10 | Induction of caspase-3-dependent apoptotic cell death in HepG cells | B16-F10–18.23 μg/mL–72 h | |||||

| PC-3 | 10, 30.50, 70, 100 μg/mL | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | PC-3 - 18 μg/mL–48 h | Thymol exhibited cytotoxicity and induced apoptosis | Pathania et al. (2013), India |

| MDA-MB 231 | Apoptosis induction | Cell proliferation | MDA-MB 231–15 μg/mL–48 h | ||||

| A549 | 48 h of incubation | DNA fraction sub G0 | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | A549–52 μg/mL–48 h | |||

| MCF-7 | TNF-R1 | MCF-7 - 10 μg/mL–48 h | |||||

| HL-60 | Bax | Bcl-2 | HL-60–45 μg/mL–48 h | ||||

| Caspase-8 and 9 | |||||||

| Caco-2 | 100–2,500 μM | – | – | – | – | The cells exposed to thymol remained unchanged and did not produce any cytotoxic, apoptotic or necrotic effects at any of the tested concentrations | Llana-Ruiz-Cabello et al. (2014), Spain |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | |||||||

| A549 | 1–1.000 μM | SRB assay | Cytotoxic effects | – | A549–0.187 ± 0.061 mΜ–72 h | Thymol exhibited more effective cytotoxicity against cells (Hep3B), while cells (A549) were less sensitive to treatment and cells (HepG2) were more resistant | Fitsiou et al. (2016), Greece |

| HepG2 | 72 h of incubation | Antiproliferative effects | HepG2 - 0.390 ± 0.01 mΜ–72 h | ||||

| Hep3B | Hep3B- 0.181 ± 0.016 mΜ–72 h | ||||||

| AGS | 100, 200, 400 μM | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Thymol has potent anticancer effects on gastric cancer cells | Kang et al. (2016), Republic of Korea |

| Apoptosis induction | |||||||

| Sub-G1 phase | Cell growth | ||||||

| 6, 12, 24 h of incubation | Generation of ROS | ||||||

| Bax | MMP | ||||||

| Caspase-8, -7 and -9 | |||||||

| C6 | 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, | – | – | Cell viability | – | Thymol is a potential candidate for the treatment of malignant gliomas | Lee et al. (2016), Republic of Korea |

| 30, 100, 200 µM | Cell migration | ||||||

| 24 h of incubation | p-ERK1/2 | ||||||

| MMP-2 and -9 | |||||||

| A549 | 0–250 μM | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Thymol has cytotoxic and antioxidant activity and its cytotoxic effect was greater than that of carvacrol | Coccimiglio et al. (2016), Canada |

| 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| HCT-116 | 100, 150, 200 μg/mL | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell proliferation | – | Thymol can be used as a potent drug against colon cancer due to its lower toxicity | Chauhan et al. (2018), Republic of Korea |

| 24 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | Clonogenic potential | |||||

| Generation of ROS | |||||||

| Caspase-3 | |||||||

| p-JNK | |||||||

| Cyt C | |||||||

| HepG2 | 0.06, 0.11, 0.22, 0.45, 0.90 μg/μL | MTT assay | – | Cell viability | 289 mg/L–24 h | Thymol has therapeutic potential in tumor cells without adverse effects on healthy cells | Elshafie et al. (2017), Italy |

| 24 h of incubation | Hepatocarcinoma cells | ||||||

| T24 | 25, 50, 100, 150 μM | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | T24–90.1 ± 7.6 μM–24 h | Thymol can be used as a promising anticancer agent against bladder cancer | Li et al. (2017), China |

| SW780 | 24 h of incubation or 100 μM – | Apoptosis induction | Cell cycle stop in phase G2/M | SW780–108.6 ± 11.3 μM–24 h | |||

| p21 | Cyclin A and B1 | ||||||

| J82 | 6, 12, 24, 36 h of incubation | Caspase-3 and -9 | CDK2 | J82–130.5 ± 10.8 μM–24 h | |||

| p-JNK | |||||||

| p-p38 | |||||||

| MAPK | PI3K/Akt | ||||||

| Generation of ROS | |||||||

| PC-3 | 100, 300, 500, 700, 900 μM | – | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | – | Thymol was cytotoxic to PC-3 cells | Yeh et al. (2017), China |

| 24 h of incubation | Induction of cell death | ||||||

| Cal7 | 200–800 µM | Cell Titer 96 ® Aqueous non-Radioactive cell Proliferation assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 350 μM–500 μM | Thymol had cytotoxic, antiproliferative and antitumor effects | De La Chapa et al. (2018), United States |

| SCC4 | 48 h of incubation | ||||||

| SCC9 | |||||||

| HeLa | |||||||

| H460 | |||||||

| MDA-231 | |||||||

| PC-3 | |||||||

| AGS | 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600 µM | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent cell viability assay | Apoptotic effects | Cell viability | 75.63 ± 4.01 µM–24 h | Thymol has cytotoxic, apoptotic, genotoxic and dose-dependent ROS-generating effects | Günes-Bayir et al. (2018), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | Necrosis | Bcl-2 | |||||

| Bax | |||||||

| Caspase-3 and -9 | |||||||

| Generation of ROS | GSH levels | ||||||

| Genotoxic effect | |||||||

| MCF-7 | 10, 15, 30, 50, 80, 100, 200 μg/mL | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Bcl-2 | MDA-MB 231–56 μg/mL–24 h | Thymol has antiproliferative effects | Jamali et al. (2018), Iran |

| MDA-MB 231 | 24 h of incubation | Antiproliferative effect | Interruption of cell cycle progression in the S phase | MCF-7 - 47 μg/mL–24 h | |||

| Apoptosis induction | |||||||

| Caspase-3 | |||||||

| Bax | |||||||

| Generation of ROS | |||||||

| Sub-G1 phase | |||||||

| MCF-7 | 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 75, 100 g/mL | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | Number of cancer cells | 54 μg/mL - 48 h | Thymol can induce the process of apoptosis in MCF-7 and, therefore, can be considered an anticancer agent | Seresht et al. (2019), Iran |

| 48 and 72 h of incubation | p53 | Cell cycle arrest induction | 62 μg/mL - 72 h | ||||

| p21 | |||||||

| HT-29 | 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 750, 1,000 ppm | Trypan Blue exclusion assay | Cytotoxic effects | – | 152.1 ± 18.0 ppm–24 h | Thymol induces cytotoxicity and provides genoprotective effects | Thapa et al. (2019), United Kingdom |

| 24 h of incubation | Genoprotective effects | ||||||

| MDA-MB 231 | 100, 200, 400, 600, 800 µM | MTT assay | Cytotoxic effects | – | MDA-MB 231–208.36 μM–72 h; | Thymol has apoptotic and antiproliferative properties and can serve as a potential therapeutic agent | Elbe et al. (2020), Turkey |

| PC-3 | 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation | Antiproliferative effect | PC-3 - 711 μM–24 h, 601 μM–48 h and 552 μM–72 h; | ||||

| DU 145 | Apoptosis induction | DU 145–799 μM–24 h, 721 μM–48 h and 448 μM–72 h | |||||

| KLN 205 | KLN 205–421 μM–48 h and 229.68 μM–72 h | ||||||

| SKOV-3 | 100, 200, 400, 600 μM | MTT assay | Apoptosis induction | Cell viability | 316.08 μM–24 h | Thymol was cytotoxic to the ovarian cancer cell line and it was more potent than carvacrol | Elbe et al. (2020), Turkey |

| 24 and 48 h of incubation | 258.38 μM–48 h | ||||||

| HCT116 | 10, 20, 40, 80, 120 μg/mL | CCK-8 Kit | Apoptosis induction | Proliferative capacity | LoVo - 41.46 μg/mL - 48 h | Thymol treatment reduced the proliferative capacity of cells and suppressed cell migration and invasion | Zeng et al. (2020), China |

| HCT116–46.74 μg/mL - 48 h | |||||||

| LoVo | 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation | Bax | Cell migration and invasion | ||||

| Caspase-3 and PARP | Cell cycle stop | ||||||

| Cells in phase G0/G1 | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Cells in S and G2/M phases | |||||||

| AGS | 0–600 μM | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent cell viability assay | Cytotoxic effects | Cell viability | 75.63 ± 4.01 μM–24 h | Thymol has cytotoxic and antioxidant effects in gastric adenocarcinoma | Günes-Bayir et al. (2020), Turkey |

| 24 h of incubation | Generation of ROS | GSH levels | |||||

| Apoptosis induction | |||||||

| Bax | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Caspase-3 and -9 | |||||||

| DNA damage | |||||||

| A549 | 25–200 μg/mL | MTT assay | Antiproliferative effect | Cell viability | 745 μM–24 h | Thymol can act as a safe and potent therapeutic agent to treat non-small cell lung cancer | Balan et al. (2021), India |

| 12 and 24 h of incubation | Apoptosis induction | MMP | |||||

| DNA damage | Bcl-2 | ||||||

| Generation of ROS | |||||||

| Caspase-3 and -9 | |||||||

| Bax | SOD | ||||||

| Cells in phase G0/G1 | |||||||

| TBARBS | |||||||

| CARBONIL | |||||||

| KG1 | 25, 50, 100 μM | – | Cell death | Cell viability | – | KG1 cells treated with 50 µM thymol were more sensitive compared to the other two lines. At 100 μM, thymol induced complete cell death of KG1 and HL60 cells, while about 50% of K562 cells resisted cell death after 48 h of treatmentl | Bouhtit et al. (2021), Belgium |

| K-562 | 24 and 48 h of incubation | ||||||

| HL-60 | |||||||

| Model | Concentration | Results/Targets | Conclusion | Authors (Year), country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Decrease | ||||

| In vivo studies | |||||

| Female athymic nude rats were injected subcutaneously in the right flank with 3 × 106 Cal27 or HeLa cells in 0.1 mL of sterile PBS | 4.3 mM thymol (32 μg diluted in 50 μl sterile saline with a final concentration of 0.25% DMSO) | Apoptotic cells | Tumor volume reduction | Thymol had cytotoxic, antiproliferative and antitumor effects | De La Chapa et al. (2018), United States |

| Proliferative cells | |||||

| Xenograft model: BALB/c male nude mice were injected subcutaneously with HCT116 cells (1 × 107 cells in 0.2 mL of PBS) on the back | Xenograft model and lung metastasis model: Intraperitoneal injection for 30 days with thymol at 75 mg/kg 1x on alternate days or thymol at 150 mg/kg 1x on alternate days | Necrotic lesions | Tumor growth and metastasis | Thymol inhibits the growth and metastasis of colorectal cancer in vivo by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling and the EMT program | Zeng et al. (2020), China |

| Average number of tumor nodules on the surface of the lungs | |||||

| Bax | Ki-67 expression level | ||||

| Lung metastasis model: HCT116 cells (1 × 106) were intravenously injected into the tail vein of each mouse | Cell proliferation | ||||

| Bcl-2 | |||||

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | |||||

| Caderina-E | Vimentina | ||||

| Cyclin D1 | |||||

| C-myc | |||||

| Survivin | |||||

| Male Wistar rats injected with DMH (40 mg/kg intraperitoneally, twice a week) for 16 consecutive weeks | 20 mg/kg/day, orally, for 16 weeks | Final body weight | Mortality | Thymol administration had promising preclinical protective efficacy by promoting inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation and induction of apoptosis | Hassan et al. (2021), Egypt |

| Weight gain | Incidence of ACF | ||||

| Growth rate | Serum CEA levels | ||||

| NRF2 | Serum levels of CA19-9 | ||||

| Caspase-3 | |||||

| TNF-α | |||||

| GST, GSH, SOD, CAT | NF-κB | ||||

| IL-6 | |||||

| Tissue content of MDA (colon lipid peroxidation) | |||||

Abbreviations: 5RP7, Mouse embryonic fibroblast with transformation of H-ras oncogenes; 8-OHdG, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; A375, Melanoma (skin) cancer cell line; A549, Lung Carcinoma Cell Line; ACF, Aberrant crypt foci; AFP, Alpha-fetoprotein serum; AFU, Alpha l-fucosidase; AgNORs, Proteins Associated with the Argyrophilic Nucleolar Organizing Region; AGS, Human gastric carcinoma cell line; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT, Alanine transaminase; AST, Aspartate transaminase; AXL, Tyrosine Kinase Receptor; B[a]P, 3.4 benzopurene; B16-F10, Mouse melanoma cells; BT-474, Breast ductal carcinoma; BT-483, Breast ductal carcinoma; C6, Glioma cell line; Caco-2, Cell line derived from human colon carcinoma; CA 19–9, Tumor markers carbohydrate antigen 19–9; Cal27, Cell line of the squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue; CAT, Catalase; CEA, Carcinoembryonic antigen; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; CCND1, Gene encoding the cyclin D1 protein; CDK4 or 6, Cyclin-dependent kinases; cGT, Glutamyl transpeptidase Range; CyT C, Cytochrome C; c-Myc, Proto-oncogene; CO25, Mouse muscle cell line; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase; DAPK1, Protein kinase 1 associated with death; DBTRG-05MG, Human Glioblastoma Cells; DEN, Diethylnitrosamine; DMH, 1,2-dimethylhydrazine; DMBA, 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene; DMSO, Dimethylsulfoxide; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; DU 145, Human Prostate Cancer Cell Line; EC50, Half of the maximum effective concentration; EMF, Acute T Lymphoblastoid Leukemia; EMT, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ERK 1/2, Kinase 1/2 regulated by extracellular signal; ERO, Reactive Oxygen Species; GGT, Gamma-Glutamyltransferase; GPx, Glutathione Peroxidase; GR, Glutathione reductase; GSH, Reduced Glutathione; H1299, Parental and Drug Resistant Human Lung Cancer Cell Line; H460, Non-small cell lung cancer cell line; HCT116, Colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line; HeLa, Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line; Hep, Human Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma; Hep3Β, Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line; HepG2, Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line; HL-60, Human Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cell Line; HT-29, Colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line; IC50, Half of the maximum inhibitory concentration; IL-6, Interleukin-6; J82, Bladder Cancer Cell Line; Jagged-1, Jagged Canonical Notch Ligand 1; JAR, Human Choriocarcinoma Cell Line; JEG3, Human Choriocarcinoma Cell Line; Jurkat, Lymphocytes derived from T-cell lymphoma; KG1 and K-562, Human Myelogenous Leukemia Cell Line; Kelly, Neuroblastoma cell line; Ki-67, Antigen, biomarker; KLN 205, Non-small cell lung cancer; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; LoVo, Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cell Line; MAPK, Protein kinase activated by mitogen; MTT, Methyl Tetrazolium Test; MTS, Tetrazolium salt reduction; MCF-7, Human breast cancer cell line; MCF-7gem, Gemcitabine-resistant human breast adenocarcinoma; MDA, Malondialdehyde; MDA-MB 231, Human metastatic breast adenocarcinoma cell line; MDA-MB 453, Human metastatic breast adenocarcinoma cell line; MDPK, Myotonic dystrophy protein kinase; MG63, Human Osteosarcoma Cell Line; MMP, Potential of the mitochondrial membrane; MMP-2 or 9, Metalloproteinase-2 or 9 of the matrix; N2a, Rat neuroblastoma cell line; NDEA, N-nitrosodiethylamine; Notch-1, Signaling path; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; OC2, Human oral cancer cells; OSCC, Human oral squamous cell carcinoma; p21, WAF1 encoding gene; p38, Mitogen-activated protein kinases; p53, tumor protein; P-815, Murine Mastocytoma Cell Line; p-AKT, Phospho-protein kinase B; PBS, Sterile phosphate buffered saline; PC-3, Human Prostate Cancer Cell Line; PCNA, Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen; PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target; PI3K/Akt, Phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt; p-JNK, Fosto-c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p-p38, Phospho-p38; PPP2R2A, Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A; p-STAT3, Phospho-signal transducer and transcription activator; SRB, Sulforhodamine B; SCC-25, Human squamous cell carcinoma cell line; SCC4 and SCC9, Human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line; SH-SY5Y, Neuroblastoma cell line; SiHa, Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line; SKOV-3, Ovarian cancer cell line; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; SW780, Bladder cancer cell line; T24, Bladder Cancer Cell Line; TAC, Total antioxidant capacity; TBARS, Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances; TCA-8113, Human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell line; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha; TNFR1, Tumor necrosis factor 1 receptor; TOS, Total oxidant status; TRPM7, Subfamily M of the cation channel of the potential transient receptor Member 7; U87, Human glioblastoma cell line; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; XXT, 2.3‐bis(2‐methoxy‐4‐nitro‐5‐sulfophenyl)‐2H‐tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt.

Description of In Vitro Studies with Carvacrol and Thymol

Carcinomas

Carvacrol (500 and 1,000 μM) was able to inhibit the viability and proliferation of lung cancer cells (A549 cell line), in addition to inducing early apoptotic characteristics (Koparal and Zeytinoglu, 2003) and reducing the viability of the A549, H460 (Jung et al., 2018) and H1299 cells lines, the latter being resistant to epirubicin (Ozkan and Erdogan, 2012). These effects occurred mainly through the inhibition of tyrosine kinase receptor (AXL) expression and an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels (8-OHdG) (Ozkan and Erdogan, 2012; Jung et al., 2018).

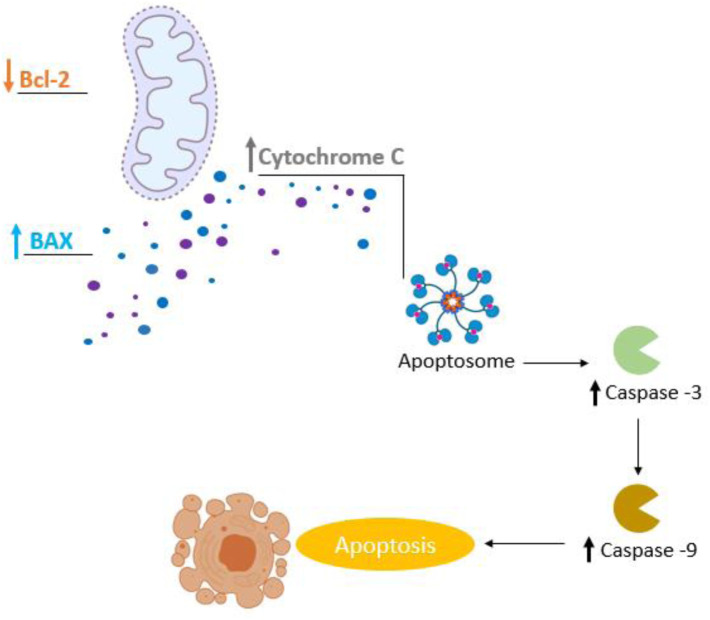

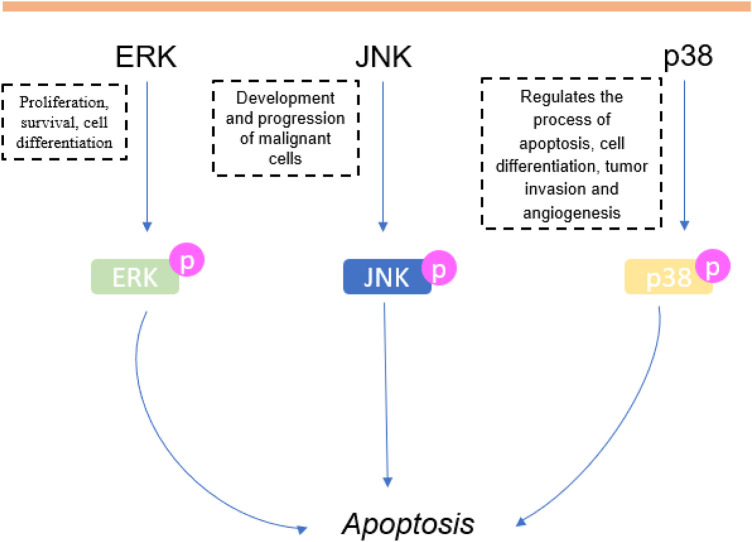

In relation to hepatocarcinomas (HepG2 cell line), carvacrol exhibited anticancer effects, provoking cell death and antiproliferative effects in a concentration-dependent manner (Özkan and Erdogan, 2011; Melusova et al., 2014). The inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis induction occurred via the mitochondria-mediated pathway, accompanied by caspase-3 activation and Bcl-2 inhibition (Yin et al., 2012). The via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) protein, and mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38) apoptotic pathways may also be involved (Yin et al., 2012). Similarly, Melušová et al. (2014) demonstrated a marked apoptotic effect of carvacrol at a concentration of 650 μM after 24 h of incubation, and an accumulation of cells in the G1 phase, together with a reduction of cells in the S phase, slowing cell cycle/mitosis and provoking cell death.

Colorectal cancer (Caco-2 cell line) also exhibited reduced cell viability and a significant increase of early apoptotic cells after carvacrol incubation (115 μM) (Llana-Ruiz-Cabello et al., 2014). There was also inhibition of HCT116, LoVo and HT-29 cells proliferation (Fan et al., 2015; Pakdemirli et al., 2020). Carvacrol also promoted a decrease in Bcl-2, metalloproteinase-2 and -9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9), p-ERK, p-Akt, cyclin B1 levels and an increase in p-JNK, Bax levels, resulting in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase (Fan et al., 2015).

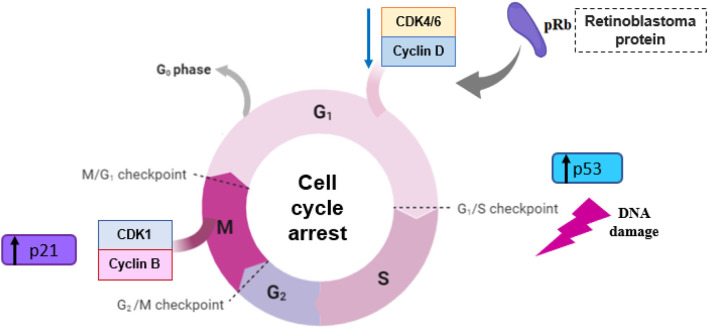

In respect of breast cancer, treatment with carvacrol decreases MDA-MB231 (Jamali et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021) and MCF-7 cells line viability (Al-Fatlawi and Ahmad, 2014; Jamali et al., 2018; Tayarani-Najaran et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). At 200 μM, the MDA-MB-231 cell line was the most sensitive and MCF-7 was the least sensitive, indicating that the effectiveness of carvacrol may vary according to the types of breast cancer cell. In addition, the TRPM7 pathway is one of the suggested pharmacological mechanisms of action (Li et al., 2021). Carvacrol was more cytotoxic compared to thymol (Jamali et al., 2018), α-thujone, 4-terpineol, 1,8-cineol, bornyl acetate and camphor (Tayarani-Najaran et al., 2019). Tayarani-Najaran et al. (2019) also reported an apoptotic effect marked by an increased level of Bax protein, and cleaved both poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and caspase-3. The antiproliferative activity of carvacrol was 1.2 times higher against MDA-MB231 cells compared to U87 cells (Baranauskaite et al., 2017). MDA-MB 231 cell proliferation slowed after treatment with carvacrol, accompanied by apoptosis induction with increased levels of Bax, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, cytochrome C release, caspase activation, PARP cleavage, increased sub-phase G0/G1 of the cell cycle and a reduced number of cells in the S phase (Arunasree, 2010). The viability of MCF-7 cells was reduced after carvacrol treatment (200 μmol/L), with a significant increase in the number of early and late apoptotic cells, accompanied by a negative regulation of Bcl2 and positive regulation of Bax protein. An accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 phase was observed, along with a reduction of cells in the S and G2 phases, mainly through the reduced expressions of CDK4, CDK6, retinoblastoma protein (pRB), cyclin D and phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt (PI3K/p-AKT) (Mari et al., 2020).

It was also observed that the administration of carvacrol provoked cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on HeLa and SiHa cervical cell lines (Mehdi et al., 2011). In fact, Potočnjak et al. (2018) demonstrated that the cytotoxicity exhibited by carvacrol against HeLa cells occurred through the suppression of the cell cycle and induction of apoptosis, the latter accompanied by an increase in caspase-9, PARP cleavage, and activation of ERK, increasing the expression of phospho-ERK1/2. In SiHa cells, the reduction in viability and apoptosis induction occurred through p53 activation and Bax, caspase-3, -6, -9 expression, along, with negative regulation of Bcl-2 gene (Abbas and Al-Fatlawi, 2018). Furthermore, another study demonstrated that carvacrol and thymol were cytotoxic against ovarian cancer (SKOV-3 cell line) exhibiting apoptotic and antiproliferative properties (Elbe et al., 2020).

Carvacrol also induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis (via caspase-3 and reactive oxygen species—ROS) of human oral squamous cell carcinoma (OC2 cell line) in a concentration-dependent manner (Liang et al., 2013). In tongue cancer (Tca-8113, SCC-25 cell lines), Dai et al. (2016) reported that carvacrol effectively inhibited cell proliferation through the negative regulation of CCND1 and CDK4 expression, and the positive regulation of p21 expression, resulting in a significant decrease of cells in the S phase, in addition to inhibiting the migration and invasion abilities of Tca-8113 cells via phospho-focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK), p-catenin, ZEB1 and MMP-2 and -9 reduction. Apoptosis was marked by a reduction of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins expression and an increase of proapoptotic Bax proteins levels (Dai et al., 2016).

In a prostate cancer cell line (DU 145), carvacrol showed a significant reduction of cell viability and proliferation in a concentration and time dependent manner, marked by a cell cycle arrest, resulting in the accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 phase, and apoptosis, related to the increased activity of caspase-3, production of ROS and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Khan et al., 2017). PC-3 cells also exhibited cytotoxicity and decreased cell viability in a concentration dependent manner after carvacrol treatment (Horng et al., 2017). A blockade of TRPM7 channels, reduced expression of MMP-2 and F-actin, was also observed, together with the inhibition of PI3K/Akt and MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinases) signaling pathways was also observed (Luo et al., 2016). Similarly, Heidarian and Keloushadi (2019) reported that this monoterpene acts through the negative regulation of pERK1/2, pSTAT3 and pAKT expression, suggesting that inhibition of interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling pathways can be a promising target for prostate cancer treatment. The induction of PC-3 cells apoptosis was mostly through the intrinsic pathway, associated with the production of ROS and mediated by the increase expression of caspase-3, -8 and -9 and Bcl-2/Bax. There was also a G0/G1 phase arrest of cell cycle, together with a considerable decrease of cells in the S and G2/M phase (Khan et al., 2019). Similarly, Tayarani-Najaran et al. (2019) demonstrated decreased cell viability in a concentration dependent manner and also marked apoptosis (mitochondrial pathway), accompanied by cleavage of PARP-1 and caspase-3 and an increased Bax protein level.

Günes-Bayir et al. (2018), Günes-Bayir et al. (2018), and Maryam et al. (2015) reported cytotoxic effects of carvacrol on gastric cancer (AGS cell line) significantly reducing cell viability in a manner dependent on concentration. There was also an induction of apoptosis with a reduction of Bcl-2 protein levels, and an increase in Bax, caspase-3 and -9 protein levels, besides the production of ROS. In their most recent study, Günes-Bayir et al. (2020) also identified the cytotoxic effects of thymol on AGS cell viability, in addition to inducing apoptosis, by increasing ROS, Bax, Caspase-3, -9 levels and reducing Bcl-2 and GSH levels.

Regarding human choriocarcinoma (JAR and JEG3 cell lines), carvacrol was able to inhibit proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest. The results showed that carvacrol reduced cell proliferation and provoked apoptosis mediated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization, increased mitochondrial calcium and activation of Bax and Cytochrome C expression. In addition, treatment with this monoterpene promoted an accumulation of cells in the sub-G1 phase, indicating that changes in intracellular calcium and ROS generation are related to the antiproliferative effects observed. Additionally, there was a marked phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and also inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, indicating that carvacrol regulates signaling pathways by inhibiting MAPK and PI3K (Lim et al., 2019).

In murine B16-F10 and A375 melanoma cell lines, carvacrol reduced cell viability and induced cytotoxicity (Satooka and Kubo, 2012; Ferraz et al., 2013; Govindaraju and Arulselvi, 2018). The antiproliferative effect was confirmed by Govindaraju and Arulselvi (2018), who reported marked cell cycle arrest, attested by the accumulation of G1 phase cells, a reduction in the number of G2/M cells and apoptosis through the mitochondria-mediated pathway and PARP cleavage/activation, together with a reduced expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2.

Similarly, the administration of thymol to lung cancer cells promoted a reduction in cell viability in the A549, H460 and H1299 cell lines (Pathania et al., 2013; Coccimiglio et al., 2016; De La Chapa et al., 2018; Balan et al., 2021). Likewise, the cytotoxic effect of thymol on A549 cells was higher than carvacrol cytotoxicity (Coccimiglio et al., 2016). Thymol also promoted cytotoxicity and apoptosis of KLN 205 cells with an IC50 of 421 and 229.68 μM in 48 and 72 h, respectively (Elbe et al., 2020). In liver carcinoma cells (HepG2), thymol exhibited antioxidant activity at lower (<IC50 = 60.01 μg/mL) concentrations and antitumor effects (apoptosis and inhibition of cell proliferation) at higher concentrations (>IC50 = 60.01 μg/mL) (Özkan and Erdogan, 2011). Elshafie et al. (2017) reported HepG2 cell death, decreased cell viability and a selective action of thymol against these tumor cells.

Thymol also showed concentration-dependent cytotoxic effects and reduced the proliferation of Caco-2 cells (Horváthová et al., 2006). In contrast, Llana-Ruiz-Cabello et al. (2014) reported that Caco-2 cells exposed to thymol did not exhibit any cytotoxic, apoptotic or necrotic effects in any of the tested concentrations. HCT-116 and HT-29 cells, after thymol administration, displayed a cell number reduction, cell apoptosis by disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS production (Chauhan et al., 2018; Thapa et al., 2019). These effects may have been caused by the positive regulation of the caspase-3, PARP-1, p-JNK and Cytochrome C expression (Chauhan et al., 2018).

Breast cancer cells (MDA-MB 231 cell line) also exhibited a reduction in cell viability after thymol treatment (Pathania et al., 2013; De La Chapa et al., 2018; Elbe et al., 2020). The inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis on MDA-MB231 and MCF-7 cell lines occurred via the mitochondrial pathway and induction of oxidative damage to DNA through Bax/Bcl-2 modulation, decreased levels of procaspase-8, -9, -3, increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 and ROS, and also cell cycle arrest at S-phase (Jamali et al., 2018). According to the results found by Seresht et al. (2019), thymol produced cytotoxic effects and reduced the number of MCF-7 cells, suggesting that this monoterpene induces cell cycle arrest, probably due to p21 overexpression. Thymol also promoted a marked antitumor effect on cervical cancer (HeLa cell line), through cytotoxic effects on the concentration of 30.5 ng/mL (Abed, 2011). De La Chapa et al. (2018) also reported decreased viability of HeLa cells and induction of apoptosis by PARP cleavage, suggesting that the anticancer effect of thymol is caused by mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent apoptosis.

The administration of thymol to bladder cancer (T24, SW780, J82 cell lines) provoked inhibition of cell proliferation and decreased the cell viability in a concentration and time dependent manner, along with marked cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and induction of apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway, together with the activation of caspase-3 and -9, JNK and p38, release of cytochrome C, negative regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins and production of ROS. In addition, a considerable decrease in the expression of cyclin A, B1 and CDK2, as well as an increase in the expression of p21 were observed after treatment with thymol, suggesting that its antitumor effect occurs by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, via MAPKs, and generation of ROS (Li et al., 2017). In human laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas (Hep), thymol showed a pronounced reduction of cell proliferation and also apoptosis, at a concentration of 30.5 ng/mL. According to De La Chapa et al. (2018) thymol exhibited cytotoxicity and decreased cell viability in a concentration dependent manner on Cal27, SCC4 and SCC9 cell lines. However, this cytotoxicity was reversed by the N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) antioxidant addition, providing evidence that the anticancer mechanism of action of thymol involves mitochondrial dysfunction, and generation of ROS, culminating in apoptosis (De La Chapa et al., 2018). Thymol also caused a decrease in cell viability of prostate cancer (PC-3 cell line), and provoked cytotoxic effects (Pathania et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2017; De La Chapa et al., 2018). PC-3 cells demonstrated greater sensitivity to treatment with thymol compared to DU145 cells. In addition, the induction of apoptosis in both cell lines occurred in a concentration-dependent manner (Elbe et al., 2020). Similarly, thymol suppressed the viability of melanoma (B16-F10 cell line), also in a concentration-dependent manner, by reducing the cell number and provoking cytotoxic effects. These effects seem to be related to the oxidative damage observed after the increase of ROS levels (Satooka and Kubo, 2012).

Central Nervous System Cancers

Human glioblastoma cells (DBTRG-05MG) showed reduced viability in a concentration-dependent manner when treated with carvacrol (200–600 μM), induced apoptosis and necrosis by ROS production and caspase-3 activity (Liang and Lu, 2012). In a rat neuroblastoma (N2a cell line), treatment with carvacrol (200–400 mg/L) exhibited cytotoxic and antiproliferative effects, along with antioxidant activity (Aydın et al., 2014). Kelly and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells also exhibited a reduced proliferation rate after exposure to carvacrol (Kocal and Pakdemirli, 2020). In glioblastoma (cell line U87), carvacrol induced apoptosis by increasing the levels of caspase-3 cleavage, moreover, its antitumor mechanism of action seems to be related to the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, activation of mitogen/protein kinase by extracellular signals (via MAPK/ERK) and decreased levels of MMP-2 protein (Chen et al., 2015).

Regarding thymol, treatment at concentrations of 100 and 200 µM induced a significant reduction in cell viability and inhibited the migration of glioma cells (C6 cell line) through phosphorylation of PKCα and ERK1/2, that resulted in decreased expression of MMP-9 and MMP-2 (Lee et al., 2016). In addition, in DBTRG-05MG cells, thymol exhibited a cytotoxic effect in a concentration-dependent manner, by reducing cell viability and inducing apoptosis. The 400–600 μM range of concentrations promoted cell necrosis and the 800 μM concentration killed all cultivated cells (Hsu et al., 2011).

Sarcomas

Treatment with carvacrol in leiomyosarcoma cells exhibited antiproliferative effects in a concentration dependent manner and also inhibition of cell growth (Karkabounas et al., 2006). In addition, carvacrol showed a greater cytotoxicity compared to thymol against murine mast cell cells (P-815 cell line) (Jaafari et al., 2007; Jaafari et al., 2012), with accumulation of cells in the S phase (Jaafari et al., 2012).

In relation to thymol, there were concentration-dependent cytotoxic effects and interruption of the cell cycle progression in the G0/G1 phase in P-815 cells (Jaafari et al., 2012). In human osteosarcoma cells (MG63 cell line), thymol reduced cell viability, induced cytotoxic effects and apoptosis, which occurred in a concentration-dependent manner. Additionally, there was an increase in the production of ROS and cell death (Chang et al., 2011).

Leukemias

Carvacrol showed cytotoxic effects against human myeloid leukemia cells (K-562 cell line) (Horvathova et al., 2007; Jaafari et al., 2012) and against T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (CEM cell line) (Jaafari et al., 2012). Carvacrol was more cytotoxic than thymol, inducing accumulation of cells in the S phase (Jaafari et al., 2012). It was shown that carvacrol produced cytotoxic effects and reduced cell viability in human acute promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60 cell line) and lymphocytes derived from T-cell lymphoma (Jurkat cell line). Treatment with carvacrol (100 μM) showed early and late apoptotic cells accompanied by a reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential levels, suggesting that apoptosis was mediated by the mitochondrial pathway, with a significant increase of Bax pro-apoptotic proteins, decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl2 and an increased caspase-3 protein level (Bhakkiyalakshmi et al., 2016).

Analyzing the effects of thymol on K-562 and CEM cells, Jaafari et al. (2012) revealed that the latter was more sensitive to thymol effects, resulting in the accumulation of cells in the G0/G1 phase. In addition, treatment with thymol also reduced HL-60 cell viability, exhibiting cytotoxicity with concentrations above 50 μM (Deb et al., 2011). Cell cycle arrest was observed in the G0/G1 phase, with decreased Bcl-2 protein levels and interruption of mitochondrial homeostasis; increased ROS production, mitochondrial production of H2O2, and Bax protein levels; and activation of caspase-8, -9, -3 and PARP (Deb et al., 2011). Thus, inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway may be a possible mechanism involved behind the effects of thymol on HL-60 cells (Pathania et al., 2013).

It was observed by Bouhtit et al. (2021) that at a concentration of 300 µM of carvacrol the KG1 cell lines were more sensitive compared to the HL60 cell line, and at 400 µM the K-562 cell line showed resistance after 48 h of treatment. Regarding thymol (50 µM), the KG1 cell line was also more sensitive when compared to the other two and at the 100 µM dose, thymol was able to induce complete cell death in the KG1 and HL60 cell lines (Bouhtit et al., 2021).

Transformed Cell Lines

When using mouse myoblast cells (CO25 cell line) transformed with human N-RAS oncogene, Zeytinoglu et al. (2003) showed that the concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 μg/mL of carvacrol provoked cytotoxic effects. The same effects were also observed for 5RP7 and CO25 cells transformed by H-RAS and N-RAS oncogenes, respectively, as well as apoptotic morphological changes in both cell lines. However, the fragmentation of internucleosomal DNA and the initial apoptotic determinants were observed only in the cell line 5RP7 cell line. In addition, H-RAS-transformed 5RP7 cells were more sensitive to carvacrol than N-RAS-transformed CO25 cells (Akalin and Incesu, 2011).

Based on these data, we compiled the IC50 (μM) values determined 24 h after the incubation of the studied cells with carvacrol or thymol. It was possible to verify that, in general, carvacrol (336.7 ± 35.0, n = 21) is more potent than thymol (527.1 ± 146.6, n = 11), with difference between means of 103.8 (±106.9). The lowest IC50 values for carvacrol were against prostate carcinoma (PC-3 IC50 = 46.71 μM, Khan et al., 2019; DU 145 IC50 = 84.39 μM, Khan et al., 2017) and gastric carcinoma (AGS IC50 = 82.57 μM, Günes-Bayir et al., 2018), whereas thymol appears to be more selective for gastric cancer carcinoma (AGS, IC50 = 75.63 μM, Günes-Bayir et al., 2018) as seen in Supplementary Table S2.

Description of In Vivo Studies with Carvacrol and Thymol

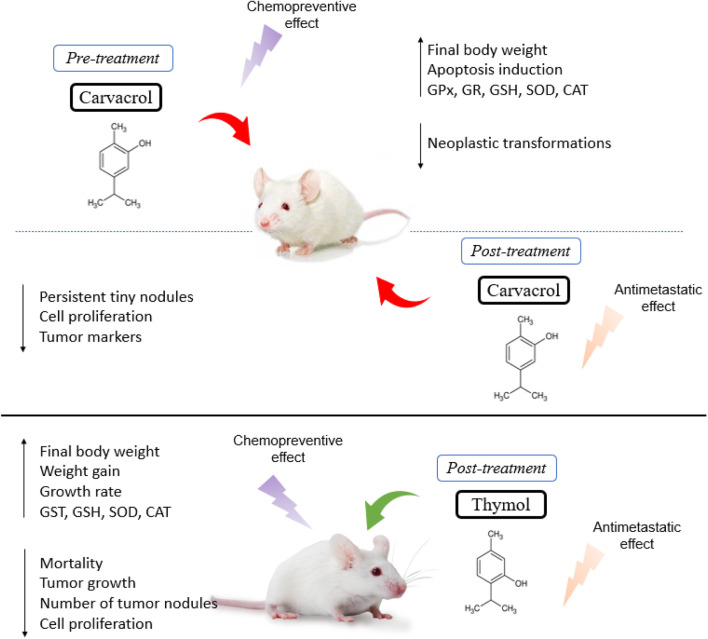

Anticarcinogenic effects were observed after treatment with carvacrol in Wistar rats, depicted by a reduction in the incidence of tumors, increased survival rate, and a reduced carcinogenic potency of the substance in inducing malignant tumors (Karkabounas et al., 2006). The pre- and post-treatment with carvacrol in animals with liver cancer induced by diethylnitrosamine (DEN) revealed a decrease in the number of nodules, a final body weight increase and a reduction in liver weight. In fact, carvacrol pre-treatment caused the disappearance of most tumoral foci and nodules, characterized by few neoplastic cells, suggesting a chemopreventive effect. In contrast, post-treatment with carvacrol demonstrated the presence of small persistent nodules, loss of cellular architecture and a lower tendency to spread through the intrahepatic veins. Moreover, carvacrol was able to increase the levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione reductase (GR) and glutathione (GSH), along with a reduction of lipid peroxides and the enzymes AST, ALT, ALP, LDH and γGT in the serum (Jayakumar et al., 2012).

Similarly, Subramaniyan et al. (2014) also evaluated the effect of carvacrol pre- and post-treatment on a DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis rat model and observed a stability in tumor marker levels, a reduced mast cell density and inhibition of cell proliferation. Furthermore, supplementation with carvacrol significantly restored the activities of liver microsomal xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes to normal, with a reduced expression of proliferative nuclear cell antigen (PCNA), MMP-2 and -9, and thereby prevented the local spread of carcinogenic cells, showing an antimetastatic effect (Subramaniyan et al., 2014). Hence, in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by diethylnitrosamine (DEN), carvacrol treatment promoted DNA fragmentation indicating its potential as an apoptotic agent. In addition, carvacrol showed a reduction in serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), alpha l-fucosidase (AFU), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and decreased expression of the gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) gene (Ahmed et al., 2013).

Carvacrol supplementation significantly improved the weight gain and growth rate of animals with colon cancer induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH), exhibiting a lower incidence of tumors and pre-neoplastic lesions, along with a reduction in oxidative stress damage (higher levels of GSH, GPx, GR, SOD and CAT), suggesting that carvacrol presents chemopreventive effects (Sivaranjani et al., 2016).

Li et al. (2019) showed that tumor growth in mice with DEN-induced hepatocarcinoma and treated with carvacrol was limited, revealing tumor cell reduction, rare mitotic figures, normal arrangement of cells, few microvessels, a central necrotic area on tumor tissue and a reduction of intrastromal and peritumor lymphocytes. Likewise, there was an increased expression of the death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) and decreased expression of serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A (PPP2R2A) in tumor tissues (Li et al., 2019). More recently, Rojas-Armas et al. (2020) showed a better effect of carvacrol at a dose of 100 mg/kg/day compared to the other doses tested (50 and 200 mg/kg/day) in female Holztman rats with breast cancer induced by 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA), showing a reduction of 4 (of 16) tumors, in addition to a 75% reduction in the frequency of tumors, a 67% reduction in incidence, an increase in tumor latency and a reduction in the average tumor volume and cumulative tumor volume (Rojas-Armas et al., 2020).