Abstract

Advanced strategies to bioengineer a fibrocartilaginous tissue to restore the function of the meniscus are necessary. Currently, 3D bioprinting technologies have been employed to fabricate clinically relevant patient-specific complex constructs to address unmet clinical needs. In this study, a highly elastic hybrid construct for fibrocartilaginous regeneration is produced by co-printing a cell-laden gellan gum/fibrinogen (GG/FB) composite bioink together with a silk fibroin methacrylate (Sil-MA) bioink in an interleaved crosshatch pattern. We characterize each bioink formulation by measuring the rheological properties, swelling ratio, and compressive mechanical behavior. For in vitro biological evaluations, porcine primary meniscus cells (pMCs) are isolated and suspended in the GG/FB bioink for the printing process. The results show that the GG/FB bioink provides a proper cellular microenvironment for maintaining the cell viability and proliferation capacity, as well as the maturation of the pMCs in the bioprinted constructs, while the Sil-MA bioink offers excellent biomechanical behavior and structural integrity. More importantly, this bioprinted hybrid system shows the fibrocartilaginous tissue formation without a dimensional change in a mouse subcutaneous implantation model during the 10-week postimplantation. Especially, the alignment of collagen fibers is achieved in the bioprinted hybrid constructs. The results demonstrate this bioprinted mechanically reinforced hybrid construct offers a versatile and promising alternative for the production of advanced fibrocartilaginous tissue.

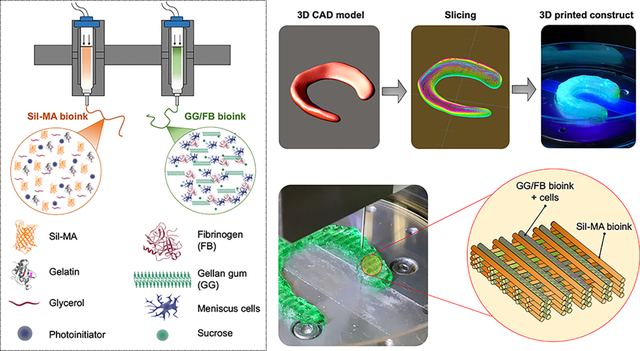

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Fibrocartilage is primarily found in the meniscus in the knee, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc (IVD).1 The meniscus is avascular, resulting in a poor intrinsic regenerative capacity, and injury often results in degenerative disease.2 Since the number of patients affected by the degeneration of the meniscus tissue has increased, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) is one of the most common orthopedic operations.3–6 To date, there is a lack of treatment options due to the unique combination of tensile and compressive properties, deformability, and complex microarchitecture of the meniscus. Thus, advanced strategies for bioengineering fibrocartilaginous tissue constructs are urgently needed.7

3D bioprinting technologies have offered promising and versatile options for the biofabrication of patient-specific constructs that resemble the anatomical, biomechanical, and biological properties of native tissues.8–14 This is achieved by precisely depositing multiple components, including cells and biomaterials (also called bioink), in single tissue architecture. The bioinks provide a 3D network capable of mimicking the in vivo microenvironment to support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Moreover, the functional and biomechanical characteristics of the printed constructs can be tuned by a bioink composition. Consequently, the bioprinted tissue constructs should provide tissue-specific biomechanical and biological microenvironments to ensure post-printing cell phenotype and maturation. The ongoing compromise between printability, capability for cell encapsulation and viability, control of the construct’s physical properties (i.e. degradation, structural maintenance, and shrinkage), and the mechanical behaviors for the tissue-specific function are continually considered to achieve the desired outcomes.

A number of natural and synthetic biomaterials as bioinks such as fibrinogen (FB),15 gelatin,16 alginate,17 hyaluronic acid (HA),18 collagen,19 poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL),20 and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)21 has been commonly utilized in the biofabrication of 3D tissue constructs and, in some cases, used together to improve the bioink characteristics,8, 22, 23 Also, the hybrid system has been suggested to achieve biologically and mechanically suitable tissue constructs: (i) one to give the biological functionality by carrying cells and biological factors and (ii) other to impart the proper structural integrity and biomechanical properties. For instance, the naturally derived hydrogels are used as cell carrier materials, while the synthetic thermoplastic polymers serve as supporting structural materials.24, 25 However, the hydrogel-based bioinks have been limited by poor structural integrity, mechanical stability, and printability, as well as rapid degradation rate.26, 27 Conversely, the synthetic polymers do not offer a proper biological microenvironment.28, 29 This can lead to a reduced cell adhesion capacity and subsequently a weak implant integration. In addition, these synthetic polymers display slow degradation and inappropriate mechanical stiffness.30, 31 More advanced bioink systems are currently being introduced to overcome these current challenges;32 however, regardless of the noteworthy improvements in 3D bioprinting technologies, challenges still remain.

For fibrocartilaginous tissue regeneration, bioinks should provide a proper cellular microenvironment and biomechanical stability to support robust deposition of tissue-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) components by the printed cells.33–35 Particularly, bioinks should withstand the cyclic compressive loading for the meniscus repair. To meet all these requirements, we develop a novel 3D hybrid tissue construct by sequentially co-printing a cell-laden gellan gum (GG) and FB composite bioink containing porcine meniscus cells (pMCs) (Figure 1A) and a silk methacrylate (Sil-MA) bioink (Figure 1B) for fibrocartilaginous tissue regeneration. We hypothesize that the cell-laden GG/FB bioink would impart the biological microenvironment necessary for cell activities and tissue formation, while the Sil-MA bioink would provide the mechanical support and stability required for the 3D printing process, as well as the structural integrity and mechanical properties of the printed tissue constructs. We examine the bioprinted hybrid tissue constructs by measuring the cell viability, proliferation, and maturation in vitro and validate the fibrocartilaginous tissue formation, organization, and dimensional maintenance using a mouse subcutaneous implantation model.

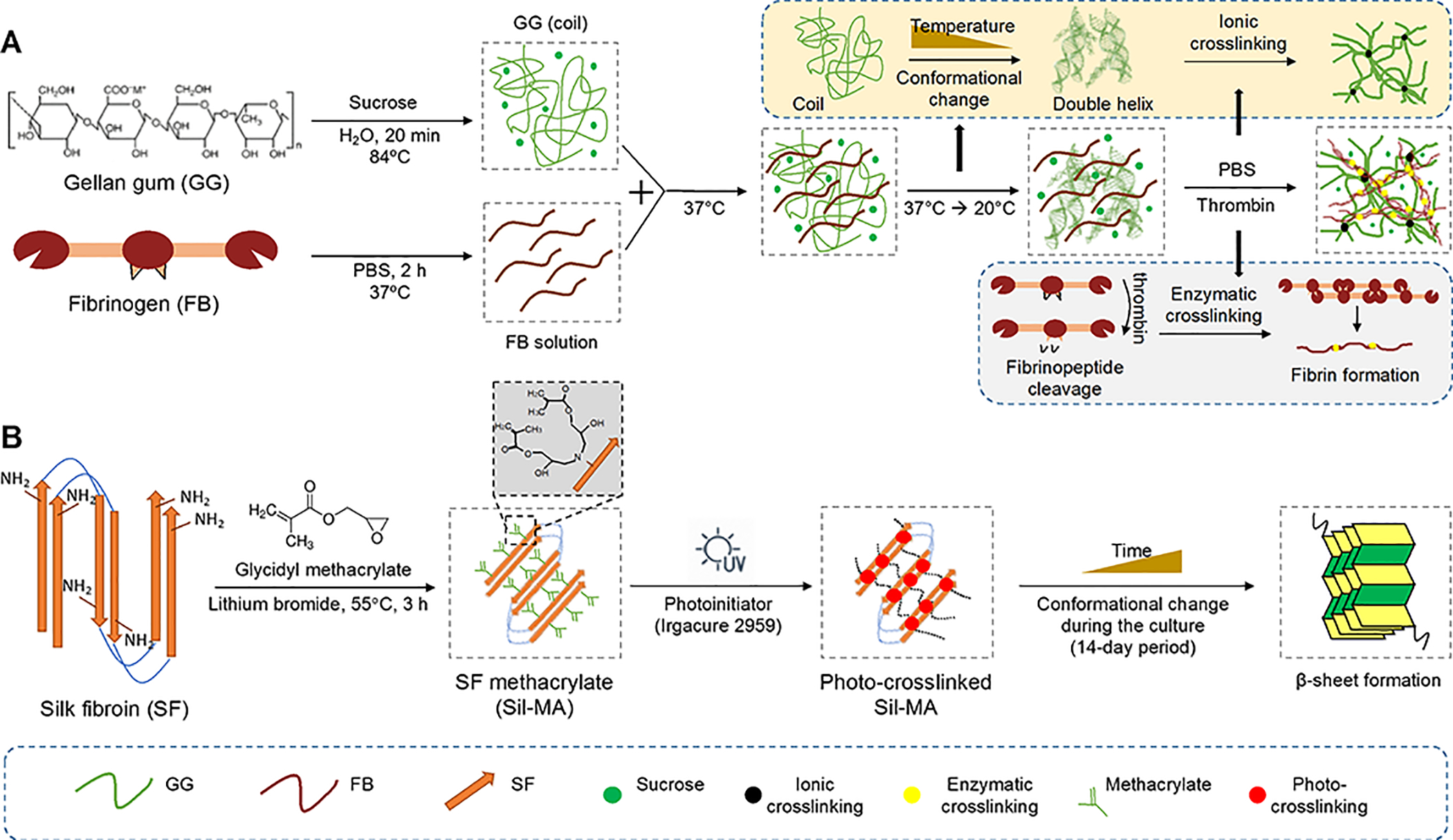

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of bioink formulations for bioprnited hybrid tissue construct. (A) GG and FB composite bioink, forming a stable hydrogel construct by a combination of ionic and enzymatic crosslinking. (B) Chemical modification of SF with methacrylate groups by reaction with MA, yielding Sil-MA.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTIONS

Materials.

Low-acyl GG and FB were obtained from Millipore Sigma (St Louis, MO). Silk fibroin (SF) derived from the silkworm B. mori in the form of cocoons was provided by the Portuguese Association of Parents and Friends of Mentally Disabled Citizens (APPACDM, Castelo Branco, Portugal). All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Millipore Sigma unless otherwise stated.

GG/FB Bioink Preparation.

The GG/FB formulations were prepared by combining two starting solutions with 1:0.04 volume ratio. GG was formulated with FB with different concentrations. GG at 12 mg/mL containing 0.25M sucrose was dissolved in distilled water at room temperature (RT) under constant stirring and then progressively heated to 84°C in an oil bath. To dissolve GG completely, the solution was kept at 84°C for 20 min under constant stirring. Finally, the solution was filtered using a 0.45 μm syringe filter and kept at 37°C until the use. FB was sterilized by ultraviolet light (UV) irradiation for 30 min and dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C for 2 h. The final concentrations of FB solutions were prepared at 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 mg/mL. Finally, the GG solution was mixed with each of the FB solutions in the volume ratio of 1:0.04. The final concentrations of FB in the GG/FB bioink formulations were 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mg/mL, respectively. Table 1 is represented the nomenclatures of the GG/FB bioinks formulations.

Table 1.

Nomenclatures of GG/FB bioink formulations

| Starting solutions (mg/mL) | Volume ratio | Final concentration of GG in bioink (mg/mL) | Nomenclatures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | FB | |||

| 12 | 0 | - | - | GG |

| 25 | 1:0.04 | 1 | GG/FB1 | |

| 50 | 1:0.04 | 2 | GG/FB2 | |

| 75 | 1:0.04 | 3 | GG/FB3 | |

| 100 | 1:0.04 | 4 | GG/FB4 | |

| 125 | 1:0.04 | 5 | GG/FB5 | |

| 150 | 1:0.04 | 5 | GG/FB6 | |

SF Methacrylate (Sil-MA) and Sil-MA Bioink Preparation.

Purified SF was prepared by removing the glue-like protein sericin from the cocoons in a 0.02 M boiling sodium carbonate solution for 1 h, followed by rinsing with distilled water in order to remove the degumming solution. A 9.3M lithium bromide solution was used to dissolve the purified SF for 1 h at 70°C. After dissolution, 1, 2, and 3 mL of glycidyl methacrylate solutions were added to 50 mL of SF solution, respectively. The reaction occurred under stirring at 55°C for 3 h. Then, the Sil-MA solutions were dialyzed in distilled water for 7 days using the benzoylated dialysis tubing (MWCO: 2 kDa) and then concentrated against PEG for 6 h. The final concentration of the solutions was determined by measuring the dry weight in the oven at 70°C overnight. Based on the amount of glycidyl methacrylate, a high [Sil-MA (H)], a medium [Sil-MA (M)], and a low [Sil-MA (L)] of Sil-MA were obtained.

The different degrees of methacrylate were determined by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) at a frequency of 400 MHz using a Bruker NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Sil-MA solutions were frozen at −80°C for 12 h and freeze-dried for 48 h. A 9.3M lithium bromide solution was prepared in deuterium oxide. Using this solution, lyophilized Sil-MA powders were re-dissolved at a final concentration of 50 mg/mL. Purified SF solution was used as control. The degree of methacrylate was defined according to the percentage of ε-amino groups of lysine in SF that were modified in the Sil-MA. Therefore, the lysine methylene signals (2.4–2.6 ppm) of samples were integrated to obtain the areas. The degree of methacrylate was obtained by the following equation;

| (1) |

Where LiSMA is the lysine integration signal of Sil-MA and LiSF is the lysine integration signal of SF.

For the printing process, the Sil-MA was formulated with gelatin and glycerol. The final concentrations of Sil-MA, gelatin, and glycerol in the formulation were 16% (w/v), 4.5% (w/v), and 8%, respectively. The Sil-MA bioinks were incubated at 65°C for 45 min, and then Irgacure 2959 at a final concentration of 0.1% (w/v) was added in the Sil-MA bioinks.

Rheological Measurement.

The rheological properties of the prepared bioinks were analyzed using a Discovery HR-2 rheometer and the acquisition software TRIOS (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). For the oscillatory experiments, the measuring system was equipped with stainless steel parallel plates using an upper measurement geometry plate of 12-mm diameter. Frequency-sweep and strain sweep were measured. For the rotational experiments, the measuring system was equipped with an upper measurement cone geometry (40-mm diameter and 1° angle). These experiments were performed at 20°C and all plots represent the average of at least three samples.

3D Printing Process.

The printing process was conducted in the house-made 3D integrated tissue-organ printing (ITOP) system based on our previous work.8 The system includes an XYZ stage/controller, multiple dispensing modules, a pneumatic pressure controller, and a closed chamber with a temperature controller. Printed cuboid constructs with a crosshatch pattern (distance between the strands: 500 μm) were designed with 3D computer-aided design (CAD) modeling using our customized software. The created CAD models were converted to a motion program containing the path information, and printing speed and air pressure were controlled. The environmental temperature was kept at 20°C.

For the GG/FB bioinks, a microscale nozzle (240 μm of diameter, TECDIA, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to print 3D cell-laden constructs at a speed of 250 mm/min and air pressures ranging 45 to 65 kPa. After printing, the constructs were cross-linked using a thrombin solution (20 U/mL) for 30 min at RT. For the Sil-MA bioinks, a microscale nozzle (300 μm of diameter, TECDIA, Inc.) was used to print 3D constructs at a speed of 250 mm/min and air pressures ranging 450 to 550 kPa. After printing, the constructs were UV crosslinked by a BlueWave® MX−150 LED Spot-Curing System (Dymax, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 120 sec at an intensity of 400 mw/cm2. A bioprinted hybrid construct was composed of the GG/FB and the Sil-MA bioinks dispensed in an interleaved crosshatch pattern with 500 μm of the distance between the strands.

Swelling Testing.

The swelling ratio of the printed constructs (10 × 10 × 5 mm3) was evaluated after immersion in PBS for time periods ranging from 1 to 24 h. All experiments were conducted at 37°C in static conditions. At each time point, the samples were removed from PBS, the excess of surface water was absorbed using a filter paper, and the sample weight was immediately determined. In the end, the samples were dried at 60°C and weight. The water uptake was obtained using the following equation;

| (2) |

Where mi is the initial weight of the sample, and mw,t is the wet weight of the sample at each time point. A minimum number of three samples were tested.

Compressive Mechanical Testing.

Uniaxial compressive properties of the printed constructs (10 × 10 × 10 mm3) were measured using a Universal Testing Machine (Instron5544 Norwood, MA) with a 100 N cell load at RT. The cross-head speed was set at 2 mm/min and tests were run until achieving 60% reduction in specimen height. From the stress-strain curve, the secant modulus was calculated at 3, 6, and 12% of strain. A minimum number of three samples was tested.

Diffusion Testing.

Diffusion tests were performed in the GG/FB bioinks using fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextrans (FITC-dextrans, Millipore Sigma) with two different molecular weights (4 and 70 kDa). FITC-dextrans were dissolved in 1 mL of a 12 mg/mL GG solution and kept at 37°C. The GG/FITC dextran solutions were posteriorly mixed with the FB solutions obtaining a final concentration of FITC of 0.2 mg/mL. Then, 100 μL of the mixture was added to a 2 mL Eppendorf tube. The samples were incubated at 37°C and 1 mL of PBS buffer, pH 7.4, was added to each tube. After 1, 3, 6, and 24 h of incubation, the amount of dye present in the release medium (PBS) was determined by measuring fluorescence intensity (λex 490 nm, λem 525 nm) using a plate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A minimum number of three samples were tested.

SEM Observation.

The morphology of the printed constructs was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FlexSEM 1000 VP-SEM, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). For SEM, the GG/FB constructs were dried by critical point drying (Leica EM CPD300, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and the Sil-MA constructs were dried by a freeze-drying process. The samples were coated with one layer of 4 nm of Au/Pd in a Leica EM ACE600 coater (Leica). SEM micrographs were taken at an accelerating voltage of 10.0 kV.

Primary Meniscus Cell Isolation and Culture.

Primary pMCs were isolated from meniscus tissue biopsies obtained from pigs. The pMCs were isolated by an enzymatic digestion-based method (collagenase type II and pronase). The extracted tissue underwent 3 washing steps: (i) povidone-iodine, (ii) PBS containing 10% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic mixture, and (iii) PBS containing 2% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic mixture. The washing steps were performed until the total removal of blood or other bodily contaminants. Meniscus tissue was then separated from the fat and vascularized tissue and was cut into small pieces. Tissue digestion was performed by incubation at 37°C in an orbital stirring for 24 h in 10–20 mL of α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic solution, 0.3% (w/v) collagenase type II, and 0.5 mg/mL of pronase. The isolated pMCs were cultured in basal medium consisting α-MEM without nucleosides supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) and antibiotic/antimycotic solution at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. The medium was changed every 2 days.

In Vitro Cellular Activities in the Printed GG and GG/FB4 3D Constructs.

3D printed cell-laden constructs (10 × 10 × 5 mm3) were fabricated using the 3D ITOP system as described above. Confluent pMCs (passage 4–5) were detached with trypsin and mixed with the GG and GG/FB4 bioinks at a density of 1.5 × 107 cells/mL, respectively. The constructs were posteriorly cross-linked by thrombin solution for 30 min at RT, and then fresh α-MEM was added. The medium was changed every 2–3 days.

The cell viability of the pMCs in the printed constructs was measured by Live/Dead staining (Life Technologies). At the designated time points, the samples of each construct were incubated in 1 μg/mL calcein-AM and 5 μg/mL propidium 269 iodide (PI) prepared in PBS for 30 min in the dark at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. After washing with PBS, the samples were immediately examined under fluorescence (calcein-AM in green: ex/em 495/515 nm; PI in red: ex/em 495/635 nm) using a transmitted and reflected light Leica TCS LSI macro Confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Germany). Z-stack scans at 200 μm intervals were acquired and analyzed to evaluate the cell viability.

Cell proliferation assay was performed by measuring the metabolic activity of pMCs in the printed constructs. Following the manufacturer’s instruction, a solution of 10% (v/v) AlamarBlue® (DAL1100; Life Technologies) dissolved in α-MEM medium was transferred to the culture plates in 500 μL/scaffold. The 3D printed cell-laden constructs were transferred to a new culture plate before the addition of the reagent. After 3 h of reaction with cells at 37°C in the CO2 incubator, 100 μL of AlamarBlue® solution was taken from each well and placed in a 96-well white opaque plate in triplicate. The absorbance was measured in a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices) at 2 different wavelengths (570 nm and at 600 nm).

In Vitro Biological Properties of the Printed Sil-MA Constructs.

In a 48-well plate, 200 μL of Sil-MA solution was added to each well and posteriorly UV cross-linked for 120 sec at an intensity of 400 mw/cm2. Confluent pMCs (passage 4 −5) were detached with trypsin-EDTA and plated at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells per well. The culture medium was changed every 2–3 days, and samples were collected at the designated time points (1, 3, and 7 days) to perform the further assays.

Quantitative Glycosaminoglycans and Collagen Contents in the 3D Printed Constructs In Vitro.

A dimethyl methylene blue (DMB) based-kit (Blyscan, Biocolor Ltd, Newtownabbey, UK) was used for sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) quantification, according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The samples were washed with PBS and digested overnight at 65°C in 1 mL papain digestion solution, prepared by adding to each 50 mL of digestion buffer, 25 mg of papain and 48 mg of n-acetylcysteine. Digestion buffer was composed of 200 mM of phosphate buffer (sodium phosphate monobasic) containing 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH 6.8). Then, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected. The GAG content was determined by adding the DMB dye. The absorbance was measured in a microplate reader with a wavelength of 656 nm. A chondroitin sulphate stock solution was used for a standard curve with concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 μg/mL. All the results were normalized against the values obtained at 1 day.

The amount of collagen was determined using a total collagen assay kit (Biovision Inc., Milpitas, CA). The assay is based on the acid hydrolysis of samples to form hydrolysates and hydroxyproline. The oxidation of the hydroxyproline leads to the production of an intermediate that forms a chromophore (abs. 560 nm). The samples were washed with PBS and hydrolyzed at 75°C overnight using hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution (~12 M). Then, the samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 3 min, and 25 μL of each hydrolyzed sample was transferred in triplicate to 96-well plate. The plate was posteriorly placed in an oven in order to evaporate. A standard curve was obtained by using the same procedure with a collagen type I Standard. After drying, 100 μL of chloramine T reagent was added to each well, and the samples were incubated at RT for 5 min. Afterward, 100 μL of the DMAB reagent was added to each well and incubated for 90 min at 60°C. The absorbance was measured in a microplate reader with a wavelength of 560 nm. All the results were normalized against 1 day obtained values.

Histological Examination.

The samples were fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin at RT and paraffin-embedded. Then, the samples were serially sectioned with 7.5-μm thick using a microtome. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Safranin-O, Masson’s Trichrome, Picrosirius Red, and Alcian Blue/Sirius Red staining. Representative images of each sample were obtained using a transmitted and reflected light microscope Olympus BX63 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

In Vivo Implantation of the 3D Fibrocartilaginous Constructs.

To examine the structural stability and fibrocartilaginous tissue formation, the bioprinted hybrid constructs (10 × 10 × 3 mm3) with a density of 1.5 × 107 cells/mL of pMCs were implanted in dorsal subcutaneous pockets of athymic mice (NU/NU Nude, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Four experimental groups, Sil-MA (H), GG/FB4 (+ cells), GG/FB4 (- cells), and hybrid constructs, were tested, and a total of 24 animals were used in this in vivo experiment [(4 groups × 3 time points × 4 samples per time point)/2 constructs per animal]. The constructs were harvested after 2, 5, and 10 weeks of post-implantation.

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with Wake Forest University Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) regulations. General anesthesia was induced using an anesthesia machine that mixed isoflurane with oxygen. Isoflurane was used with a dose between 0–5% (up to 5% induction, 1–3% maintenance). Under the general anesthesia, a dorsal longitudinal incision was made, and a subcutaneous pocket was created. The constructs were placed into the subcutaneous pockets, and the skin incision was closed in a routine fashion. All surgical procedures will be performed aseptically.

Characterization of the Retrieved Tissue Constructs.

The assessment of the dimensional changes was performed by calculating the volume of the constructs by the displacement method. Mechanical analysis of the retrieved samples was performed as described in previous sections. In addition, the constructs were evaluated by H&E, Safranin-O, Masson’s Trichrome, and Alcian Blue/Sirius Red staining, and total collagen and GAG quantification assays were performed as described above.

Image Analysis for Fibrocartilaginous Tissue Formation.

The polarized Alcian Blue/Sirius Red images were analyzed with CurveAlign program designed by Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI).36 Settings were kept at default and data were input into MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for analysis and graphing.37 Each collagen fiber was overlaid and converted into a direction heat map to quantify the alignment coefficient; with zero being no alignment and one being complete alignment. About 300 fibers per image were analyzed (3 images per sample; 3 samples per group). The alignment coefficient and collagen fiber color were both quantified using a custom MATLAB code. The color threshold for the image was used to isolate the four main colors (red, yellow, orange, and green) seen in Alcian Blue/Sirius Red stained samples under polarized light. The relative percentage of each color was quantified by dividing the pixel count of each color by the total pixel count in each image.

Statistical Analysis.

All the numerical results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). First, a Shapiro-Wilk test was used to ascertain data normality. For the compressive elastic modulus results and all the biological quantification assays, the differences between the experimental results were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Two independent experiments were performed for cell studies, and at least three samples were analyzed per group in each culturing time. The significance level was set to *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Preparation and Characterization of GG/FB Composite Bioinks.

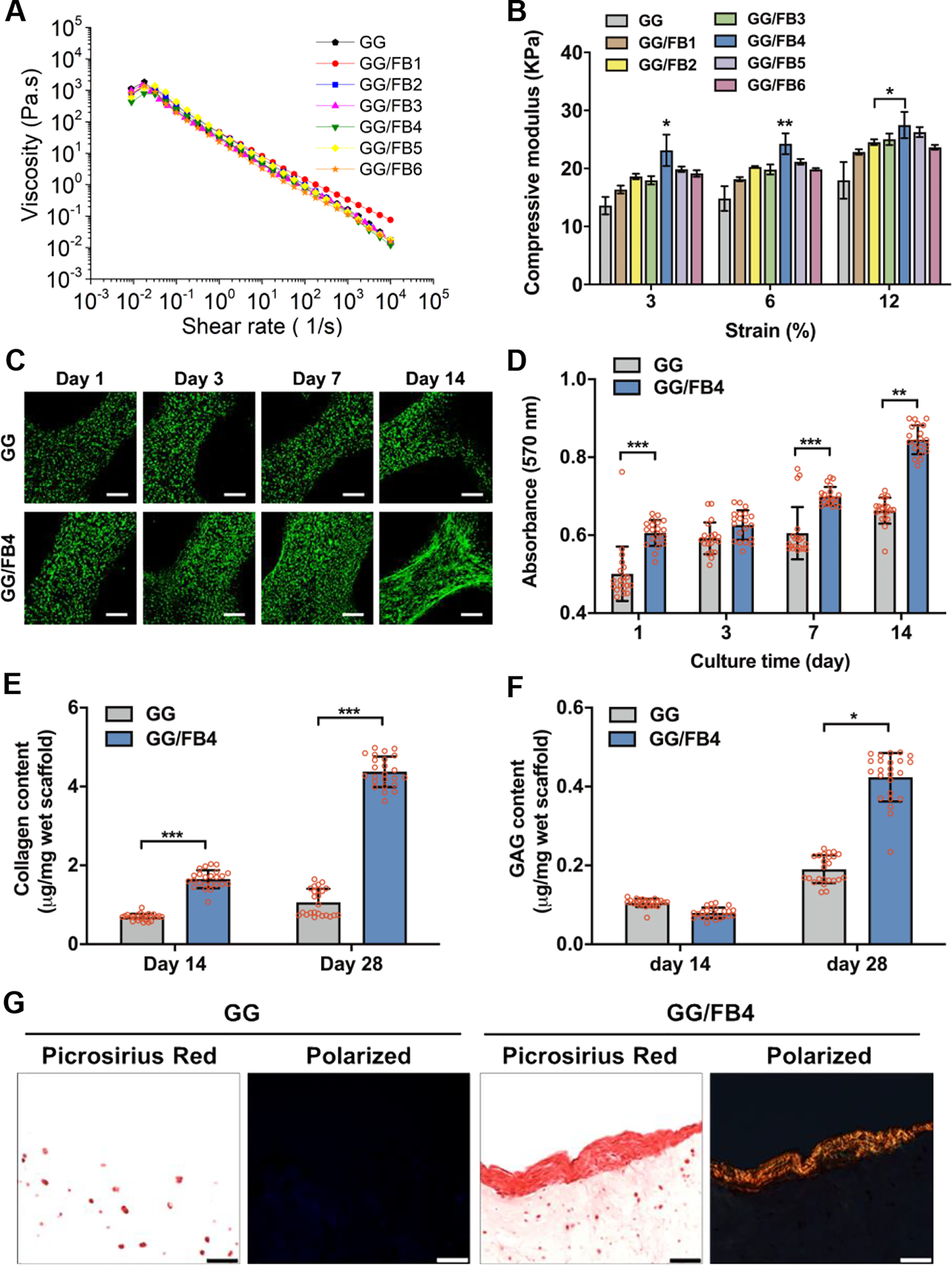

The rheological assessment of six different concentrations of FB (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mg/mL) mixed with GG was tested (Table 1), and GG alone was used as a control. Oscillatory measurements at different frequencies and low strains revealed that no significant differences were found between all GG/FB bioink formulations (Figure S1). An elastic behavior (G’>G”) was mainly exhibited by the GG/FB composite bioinks. Additionally, all bioink formulations presented a shear-thinning behavior that is crucial in extrusion-based bioprinting (Figure 2A).38

Figure 2.

Material characterization and in vitro biological evaluation of GG/FB bioinks. (A) The viscosity of GG/FB bioinks with different concentrations of FB before crosslinking and (B) compressive elastic modulus of GG/FB hydrogel constructs after crosslinking. (C) Live/dead stained images of the printed pMCs in GG alone and GG/FB4 constructs showing viability at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days in culture, where live cells were stained in green and dead cells in red (scale bar: 200 μm). (D) Metabolic activity of the printed pMCs in GG and GG/FB4 constructs at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days in culture as confirmed by AlamarBlue assay. Quantification of (E) collagen and (F) GAG production in GG alone and GG/FB4 constructs at 14 and 28 days in culture. (G) Non-polarized (left) and polarized (right) Picrosirius Red stained images of the bioprinted cell-laden GG and GG/FB4 constructs after 28 days of culture (scale bar: 50 μm). Statistical significant differences were represented by *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. GG alone without FB was used as control.

To determine the fluidic exchange and nutrient diffusion of the bioprinted GG/FB constructs, we performed the diffusion test using two different molecular weights (4 and 70 kDa) of FITC-dextrans. With the 4 kDa FTFC-dextran, about 60% diffusion occurred after 1 h of incubation, and over 90% of dextran was released after 6 h of incubation (Figure S1C). With the 70 kDa FITC-dextran, about 40% diffusion was achieved at 1 h after incubation, and about 20% of dextran was remained in the constructs for up to 24 h of incubation (Figure S1D). The results showed that the different concentrations of FB with GG did not affect the dextran diffusion from the constructs. In the swelling test, all the GG/FB constructs reached equilibrium after 1 h of immersion in PBS solution (~2800%) (Figure S1E). Overall, there were no significant differences in the diffusion rate and swelling ratio of the constructs between the GG/FB constructs with different FB concentrations.

The compressive mechanical properties of the GG/FB constructs were further evaluated using a uniaxial compression test (Figure 2B and Figure S1F). The inclusion of FB in GG enhanced the constructs’ mechanical properties, and higher values of compressive elastic modulus were observed in the GG/FB4 construct. Compared with the control group (GG alone), the compressive elastic modulus of the GG/FB4 construct increased from 13.6 ± 1.5 KPa to 23.1 ± 2.7 KPa at 3% strain (*p < 0.05), 14.8 ± 2.1 KPa to 24.3 ± 1.8 KPa at 6% strain (*p < 0.01), and from 17.9 ± 3.2 to 27.5 ± 2.3 KPa at 12% strain (*p < 0.05). The combination of ionic crosslinking of GG and thrombin-induced polymerization of FB is a plausible explanation for this mechanical improvement. However, the increase in the amount of FB is not directly proportional to the increase of the compressive elastic modulus values. The formulations GG/FB5 and GG/FB6 presented lower modulus values when compared with the GG/FB4. A possible explanation is the existence of a crosslink “competition” between the ionic crosslinking and the FB polymerization leading to less stable constructs. In further experiments, GG/FB4 was selected to be used as bioink to ensure appropriate mechanical properties and structural integrity.

To assess the in vitro biological properties of the GG/FB4 bioink, cell-laden 3D constructs were bioprinted and subsequently crosslinked with a thrombin solution. Isolated pMCs were used for cell-encapsulation in the GG/FB4 bioink. The cells were cultured for 14 days, and their viability and metabolic activity were examined by the Live/Dead® staining assay (Figure 2C) and AlamarBlue® assay (Figure 2D), respectively. The cell viability of the pMCs encapsulated in the GG/FB4 bioink was over 90% during the culture, and the metabolic activity was significantly higher compared with the control GG alone group. Significant differences were found at 1 day (***p < 0.001), 7 days (***p < 0.001), and 14 days (**p < 0.001) in culture, endorsing that the presence of FB was a key factor to improve the bioink’s biological properties. ECM deposition from encapsulated cells is also an important feature to be addressed in order to assess the bioink’s biological performance. Fibrocartilage is an avascular and aneural tissue highly embedded in a readily visible ECM.39, 40 Thus, the presence of ECM deposition is an indicator of cellular functions of the encapsulated pMCs. When encapsulated in the GG/FB4 bioink, the pMCs revealed a higher deposition of collagen (***p < 0.001, Figure 2E) and GAGs (*p < 0.05, Figure 2F) after 28 days of in vitro culture when compared with the GG alone bioink. Interestingly, perichondrium-like collagen deposition was revealed in the surface region of the GG/FB4 bioink constructs while GAG production occurred in the entire region of the constructs (Figure 2G and Figure S2).

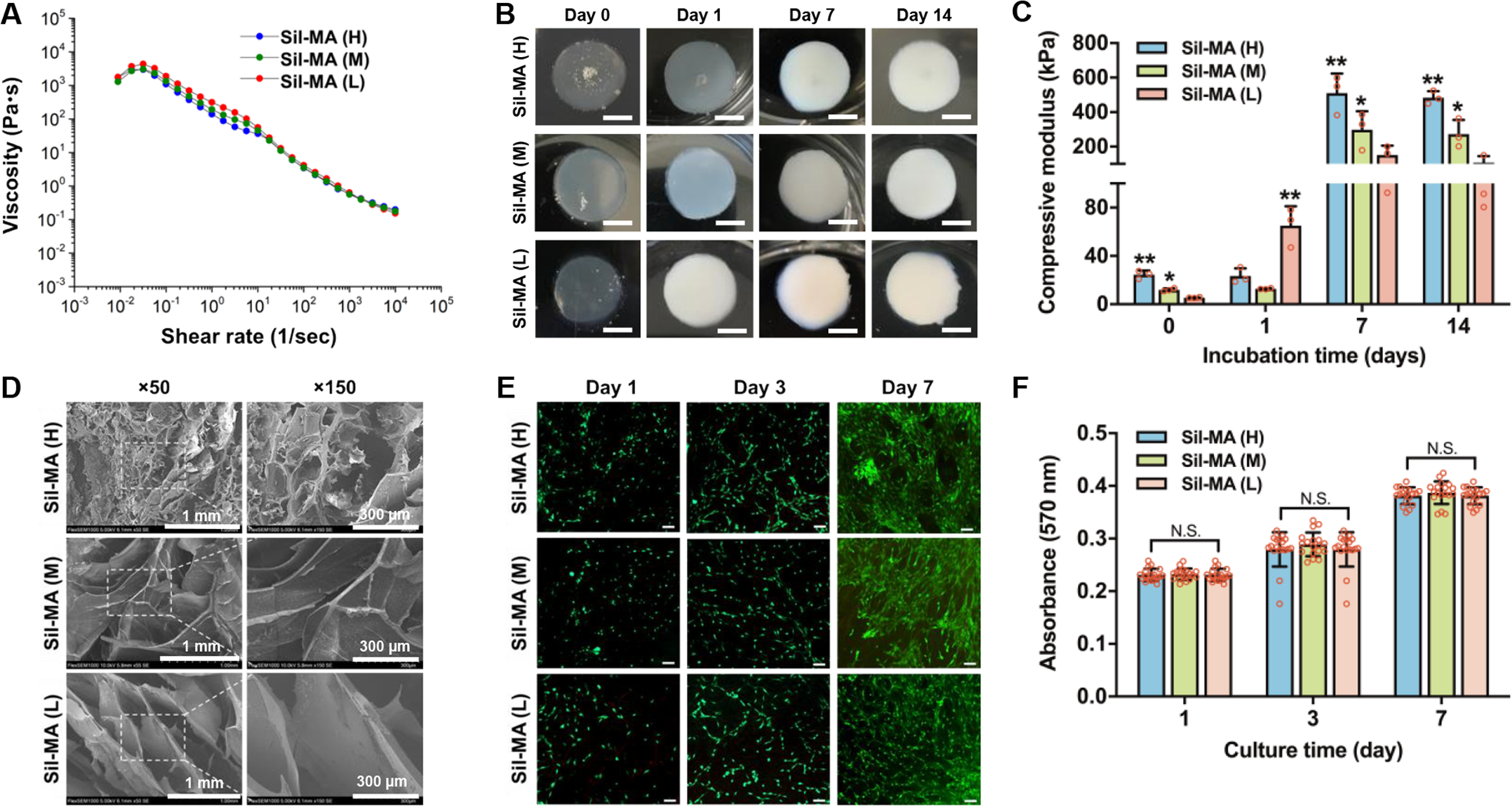

Preparation and Characterization of Sil-MA Bioink.

Fibrocartilaginous tissues are characterized to be present in zones of the human body that are subjected to great compressive and tensile loads.41, 42 Even though the GG/FB4 construct showed improved mechanical properties and structural integrity, its mechanical properties and stability are not fulfilled for fibrocartilage regeneration. Herein, we developed the Sil-MA bioink to offer the improved mechanical properties and structural integrity for bioengineering the fibrocartilaginous tissue construct. Sil-MA-based bioinks with three different degrees of methacrylation were prepared. Depending on the amount of glycidyl methacrylate used for the methacrylation, 63.5% [Sil-MA (H)], 57.2% [Sil-MA (M)], and 44.5% [(Sil-MA (L)] of methacrylate were produced for the further experiments (Figure S3). Based on the previous studies43 and preliminary extrusion tests (data not shown), Sil-MA bioinks were composed of 16% (w/v) Sil-MA, 4.5% (w/v) gelatin, and 8% (w/v) glycerol. For the printing process, gelatin introduced a thermo-sensitive property, while glycerol enhanced dispensing uniformity and prevented nozzle clogging.8 Rheological measurement presented that the chemical modification of the SF did not affect the bioinks’ rheological behavior, and these Sil-MA bioinks showed the desired elastic (G’>G”) and shear-thinning behaviors (Figure 3A and Figure S4A,B). The results suggest that the rheological behavior is highly dependent upon gelatin and glycerol that offer the proper printability despite the different degrees of methacrylate used for the printing process. Ultimately, these Sil-MA-based bioink formulations allowed to print 3D tissue constructs with good printing fidelity and easy to handle.

Figure 3.

Material characterization and in vitro biological evaluation of Sil-MA bioinks. (A) The viscosity of Sil-MA bioinks with different methacrylate degrees. (B) The conformational change occurred during incubation at 0, 1, 7, and 14 days of incubation. (C) Compressive elastic modulus of Sil-MA constructs at 0, 1, 7, and 14 days in culture (*p < 0.05 compared with Sil-MA (L) at 0, 7, and 14 days; *p < 0.05 compared with Sil-MA (M) at 1 day and **p < 0.05 compared with others). (D) SEM images of Sil-MA constructs with different methacrylate degrees. (E) Live/dead stained images of pMCs seeded Sil-MA constructs at 1, 3, and 7 days in culture, where live cells were stained in green and dead cells in red (scale bar: 200 μm). (F) Metabolic activity of pMCs seeded in Sil-MA constructs at 1, 3, and 7 days in culture as confirmed by AlamarBlue assay (N.S.: no significant).

The conformation change of the Sil-MA constructs was determined under an aqueous condition with time. These constructs can be examined by the occurrence of a spontaneous conformation change from random coil to crystalline conformation (β-sheet).44, 45 In this study, the spontaneous conformation change of the Sil-MA constructs was also confirmed after a photo-crosslinking process via UV exposure. By altering the degree of methacrylate, the results showed the possibility to tune the rate of conformation change, as well as the improvement of the mechanical properties over time (Figure 3B,C and Figure S4C). In Figure 3B, the Sil-MA constructs presented a predominance of random coil conformation after printing, as confirmed by their transparent appearance. This color change is indicative of a conformation change from random coil to β-sheet as previously reported.44, 45 After 1 day of incubation, the Sil-MA (H) constructs maintained a transparent appearance; however, Sil-MA (M) constructs produced an opaque white color, and the Sil-MA (M) constructs were completely white. After 7 days, all the Sil-MA constructs were completely white, indicating the predominance of the β-sheet conformation of Sil-MA. These results were endorsed by the results obtained from the following compressive mechanical testing (Figure 3C). At 0 day, the compressive elastic modulus of the Sil-MA constructs was 24.4 ± 2.8 KPa for Sil-MA (H), 11.6 ± 1.2 KPa for Sil-MA (M), and 5.4 ± 0.3 KPa for Sil-MA (L). Interestingly, the compressive elastic modulus of Sil-MA (L) was significantly increased from 5.4 ± 0.3 KPa to 62.2 ± 10.6 KPa after 1 day of incubation, while Sil-MA (H) and Sil-MA (M) remained similarly. This indicates that the conformational change of the SF is possibly impeded by the methacrylate crosslinking. After total conformation change at 7 days of incubation, the Sil-MA (H) revealed the highest compressive elastic modulus (510 ± 92.4 KPa) compared with the others, and the compressive elastic moduli of all Sil-MA constructs were maintained over time. These results show that the compressive mechanical properties of the Sil-MA constructs can be tunable by both conformational change and crosslinking degree.

We determined the pore size and swelling ratio of the Sil-MA constructs with different degrees of crosslinking. SEM observation revealed that Sil-MA (H) constructs had smaller pores compared with Sil-MA (M) and Sil-MA (L) constructs (Figure 3D). Furthermore, the swelling ratio was lower for the Sil-MA constructs with higher degrees of methacrylate (Figure S4D). To evaluate the in vitro biological properties of the Sil-MA bioinks, pMCs were seeded onto the Sil-MA constructs. Viability (Figure 3E) and metabolic activity (Figure 3F) assays showed that all Sil-MA bioinks supported cell adhesion and maintained pMCs metabolically active for 7 days of culture. No significant differences were found comparing the three different Sil-MA constructs.

In Vitro Evaluation of 3D Bioprinting of Silk-Reinforced Hybrid Tissue Constructs.

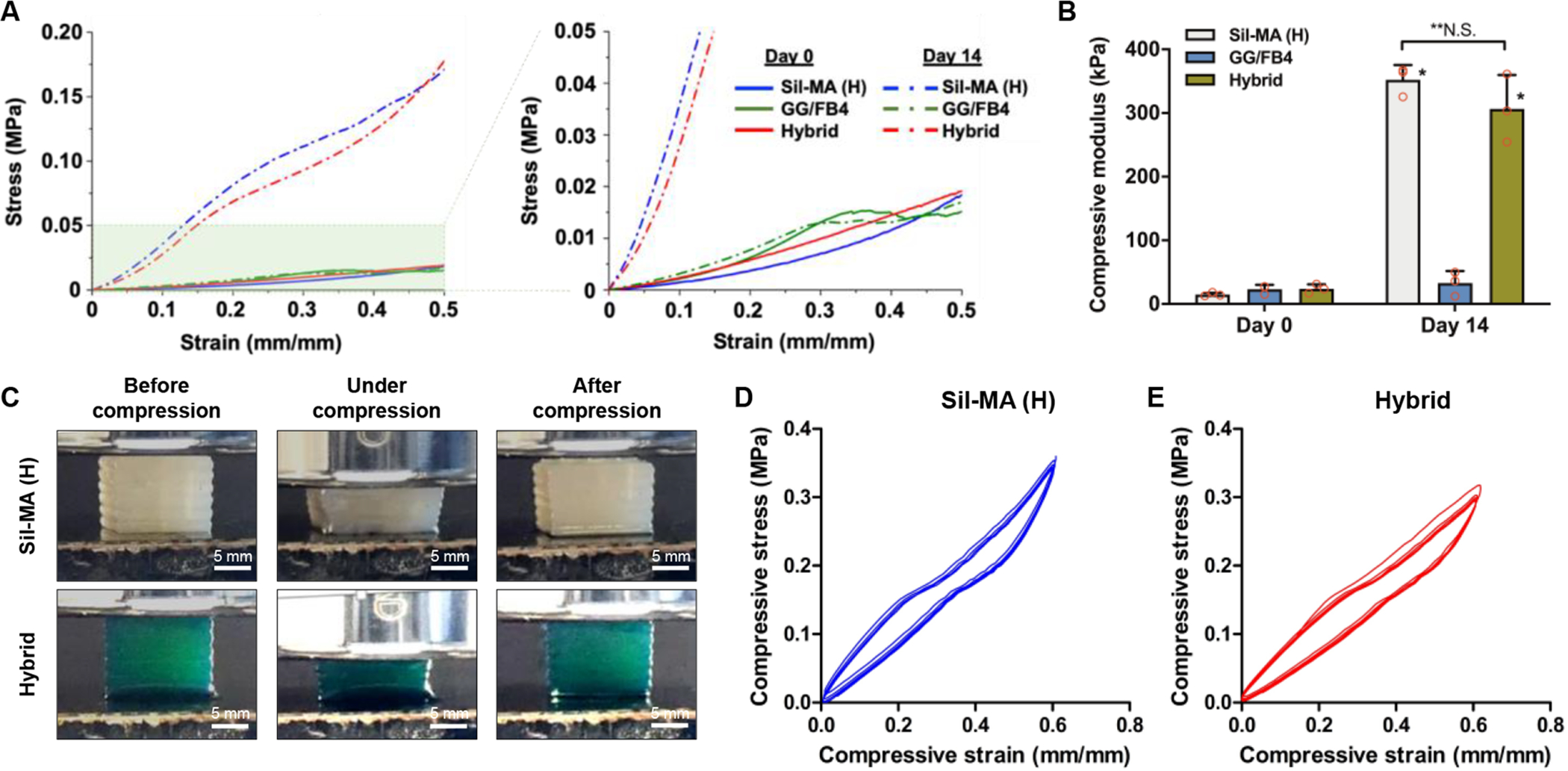

Based on the experiments above, GG/FB4 and Sil-MA (H) were chosen for the bioprinting of 3D hybrid fibrocartilaginous tissue constructs. The GG/FB4 bioink formulation had the highest compressive elastic modulus compared with other formulations while maintaining biological characteristics. The Sil-MA (H) construct also showed the highest compressive modulus, as well as high structural stability. Significant differences were observed in the compressive mechanical behavior of the Sil-MA (H) alone and hybrid (GG/FB4 + Sil-MA) constructs compared with the GG/FB4 alone constructs after 14-day incubation in PBS at 37°C (Figure 4A). The compressive elastic moduli increased from 14.7 ± 2.1 KPa to 352.4 ± 19.2 KPa and from 23.9 ± 5.7 KPa to 306.5 ± 43.7 KPa for the Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs, respectively, and there was no significant difference between the Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs at 14-day incubation (Figure 4B). In addition, the Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs presented a shape-memory capability by maintaining their original shape immediately after compression release (Figure 4C and Movie S1A,B). This shape-memory behavior was confirmed by a cyclic stress-relaxation compressive test (Figure 4D,E). The bioprinted constructs were tested up to 60% strain to examine their mechanical recovery. Five identical stress-strain plots were obtained from the five sequential stress-relaxation cycles, confirming a full shape recovery of the constructs. Furthermore, the mechanical behavior of the 3D hybrid constructs appear to be similar to native tissue, and thus suitable for biofabrication of 3D bioprinted patient-specific implants for cartilage/fibrocartilage regeneration.42, 46, 47 In addition, it is important to emphasize that the target mechanical properties could be tuned using different degrees of methacrylate and different concentrations of the SF48.

Figure 4.

Compressive mechanical properties of 3D bioprinted hybrid constructs. (A) Stress-strain curve and (B) compressive elastic modulus of the bioprinted Sil-MA (H), GG/FB4, and hybrid constructs at 0 and 14 days after incubation (*p < 0.05 compared with GG/FB4, **N.S.: no significant). (C) Gross appearance of the 3D bioprinted Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs under compression testing. The compressive cyclic stress-relaxation curve of the bioprinted (D) Sil-MA (H) and (E) hybrid constructs.

In Vivo Fibrocartilaginous Regeneration of 3D Bioprinted Hybrid Tissue Constructs.

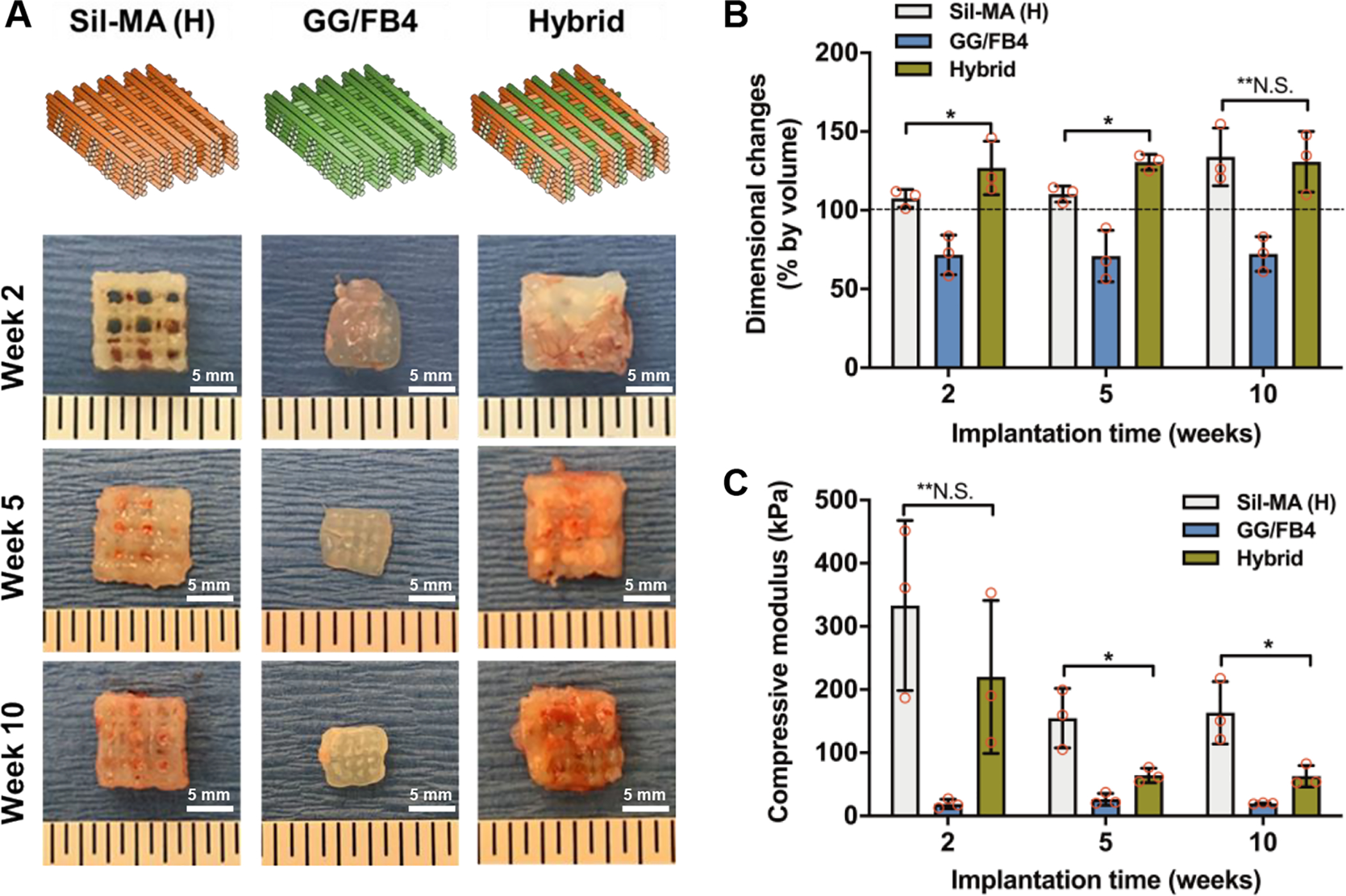

To validate the feasibility using the bioprinted hybrid constructs for the fibrocartilaginous regeneration, the constructs were implanted in the subcutaneous space of athymic nude mice and retrieved them at 2, 5, and 10 weeks after implantation. The macroscopic assessment revealed that the hybrid constructs maintained their original dimension during 10-week implantation, and vascularization was observed in the Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs (Figure 5A,B). In contrast, a reduction of dimension was observed in the GG/FB4 constructs at 2 weeks after implantation. The biomechanical analysis showed that the Sil-MA (H) (333.1 ± 109.9 kPa) and hybrid (220.0 ± 99.0 kPa) constructs presented a higher compressive modulus compared with the GG/FB4 (18.9 ± 6.1 kPa) at 2 weeks after implantation (Figure 5C). At 5 weeks after implantation, a significant decrease in mechanical strength was observed in the Sil-MA (H) and hybrid constructs, and the Sil-MA (H) (154.8 ± 38.5 kPa) was significantly higher than the hybrid (64.2 ± 9.5 kPa) constructs (*p < 0.05). Despite tissue formation, a possible degradation and deterioration of the Sil-MA (H) resulted in reducing the mechanical properties of the implanted constructs. At 10 weeks of implantation, the compressive modulus of the constructs was maintained.

Figure 5.

In vivo biological characterization of 3D bioprinted hybrid constructs. (A) Scheme of the printed patterning used for the production of 3D bioprinted constructs and gross appearance of the explants at 2, 5, and 10 weeks after implantation. (B) Dimensional changes and (C) compressive elastic modulus of 3D bioprinted constructs at 2, 5, and 10 weeks after implantation (*p < 0.05, **N.S.: no significant).

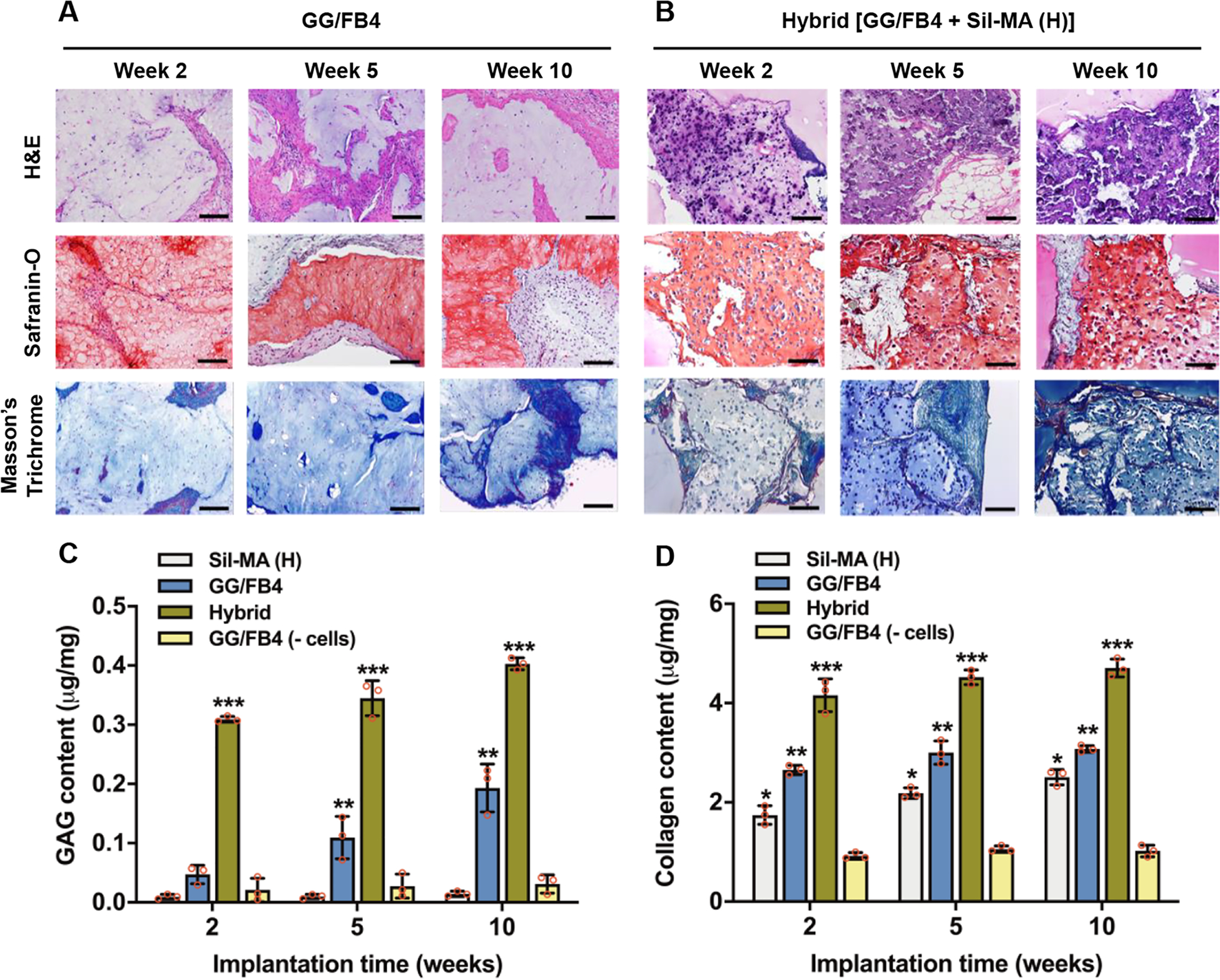

Histological analyses revealed the formation of fibrocartilage-like tissue in the GG/FB4 and hybrid constructs (Figure 6A,B). In both groups, GAG and collagenous matrix production were confirmed by Safranin O and Masson’s Trichrome staining, respectively. Quantification showed an increase in GAG and collagenous matrix production with time (Figure 6C,D). The results indicated that the hybrid constructs presented a considerably higher amount of GAGs (0.4 ± 0.01 μg/mg) and collagen (4.71 ± 0.15 μg/mg) when compared with other constructs at 10 weeks after implantation. As expected, the GG/FB4 constructs without cells presented less ECM production, and histological analysis only revealed host tissue infiltration (Figure S5).

Figure 6.

Histological and biochemical examination of the 3D bioprinted hybrid constructs. Histological images of 3D bioprinted (A) GG/FB4 and (B) hybrid constructs after 2, 5, and 10 weeks of implantation (scale bars: 200 μm). Quantification of (C) GAG and (D) collagen production of the bioprinted constructs at 2, 5, and 10 weeks after implantation; Sil-MA (H), GG/FB4, hybrid, and GG/F4 without cells (*p < 0.05 compared with GG/FB4 (-cells), **p < 0.05 compared with Sil-MA (H), and ***p < 0.05 compared with others).

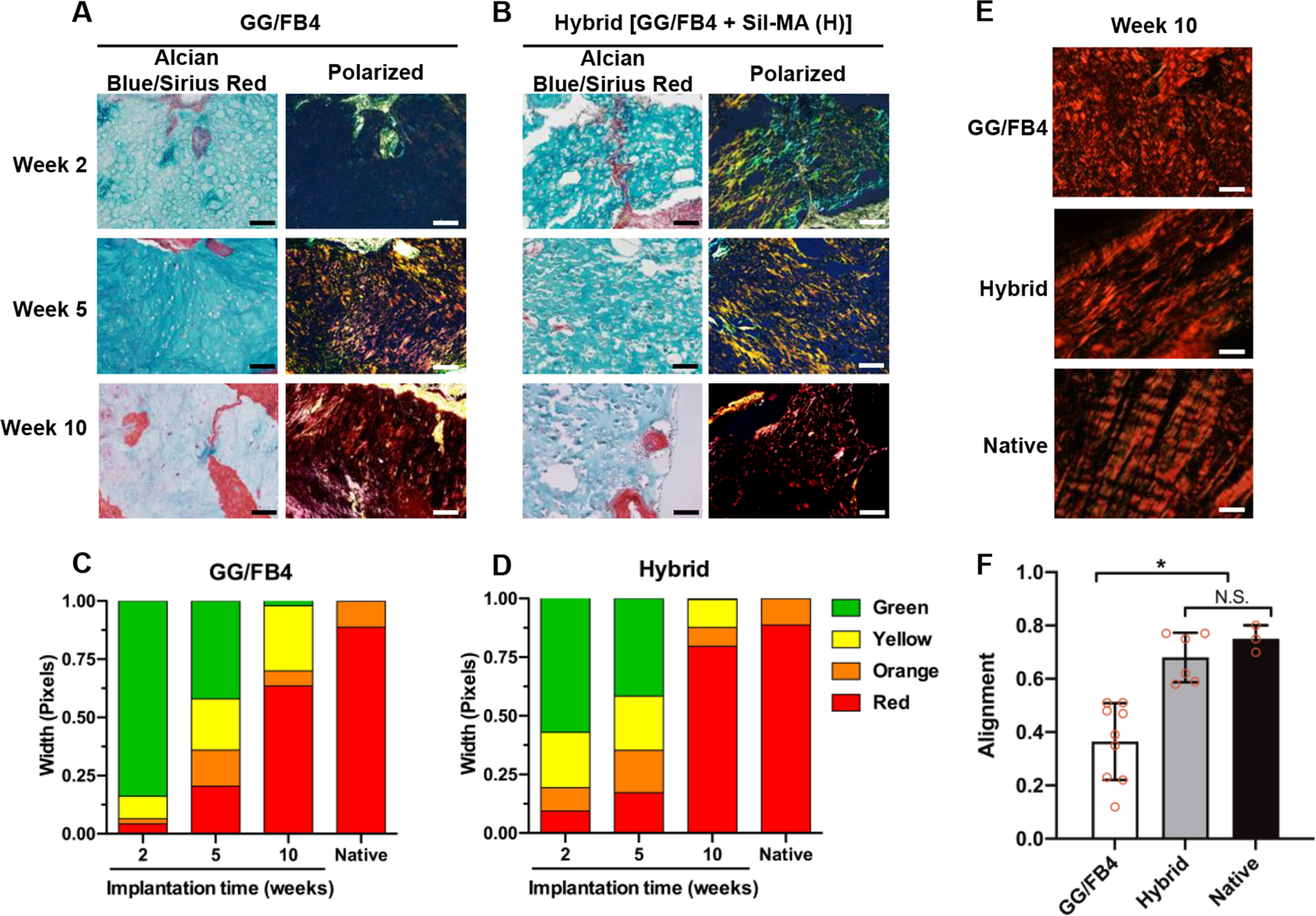

To examine the collagenous tissue maturation, we performed an imaging analysis using an Alcian Blue/Sirius Red staining. The stained samples were observed under polarized light to analyze the collagenous matrices (Figure 7A,B). In the Picrosirius Red-polarization detection method, collagen type I fibers are assigned to a yellow-red birefringence while collagen type III fibers display weak birefringent and are associated with a greenish color.49 Figure 7C,D depicts the average percentage of each collagen fiber color in the GG/FB4 and hybrid constructs. The results confirmed the change from green color to red color over the 10 weeks of implantation in both constructs, suggesting the tissue maturation with mature collagenous fibers. After 10 weeks of implantation, the hybrid construct revealed a higher presence of red-colored collagenous fibers (79.6% ± 0.01) resembling the results obtained in the native tissue (88.7% ± 0.04). In addition, CurvAlign software was used to determine the coefficient of alignment of collagen fibers in each construct (Figure 7E,F). The coefficient of alignment is considered zero when there is no alignment and one when the fibers are completely aligned. No significant differences were found between the hybrid constructs (0.68 ± 0.08) and the native meniscus tissue (0.75 ± 0.04). These results suggest that the produced tissue resembles the ECM native tissue composition and architecture.41, 50

Figure 7.

Quantification of polarized PicroSirius Red stained collagen fibers of the 3D bioprinted constructs after 2, 5, and 10 weeks of implantation. Unpolarized and polarized Alcian Blue/Sirius Red stained images of the bioprinted (A) GG/FB4 and (B) hybrid constructs (scale bar: 100 μm). The average percentage of each collagen fiber color in (C) GG/FB4 and (D) hybrid constructs using a custom MATLAB code. (E) Representative polarized images (scale bar: 20 μm) and (F) alignment analysis of the bioprinted constructs at 10 weeks after implantation and native (pig meniscus) (*p < 0.05 compared with GG/FB4, N.S.: no significant).

DISCUSSION

The cell-based 3D bioprinting has a great potential to bioengineer clinically applicable tissue constructs for reconstruction.8, 9 However, most of the hydrogels used for 3D bioprinting to deposit cells in the 3D tissue structures are mechanically weak and structurally unstable during in vitro culture or after implantation. In order to improve the structural integrity of the printed hydrogel-based constructs, we previously reported a novel 3D bioprinting system that deposits a cell-laden hydrogel together with PCL material to achieve the proper structural integrity, thereby overcoming current limitations on hydrogel-based printed constructs.8 Even though this supporting PCL structure provides the proper structural integrity to build 3D cell-laden constructs with clinically relevant size and shape, this polymeric structure is relatively stiff and less biological properties for soft tissue regeneration.51

The material selection during the development of novel bioinks is a crucial step for successful bioprinting of cell-laden constructs.52 In this study, FB and GG were selected as the cell-laden bioink. FB is a protein that has been widely used as a hydrogel in the 3D cell culture experiments, mainly due to its simple gelation process with thrombin and inherent cell-adhesion capability.12, 53, 54 However, FB-based hydrogel constructs have limited for the structural maintenance by shrinkage in an aqueous condition and rapid degradation by the fibrinolytic enzyme. Alternatively, GG is an anionic polysaccharide that has been currently used as a hydrogel55, 56 and a bioink57, 58 due to its good biocompatibility and mechanical properties.59 GG is a temperature-sensitive material, which is more viscous at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures due to its reversible physical crosslinking.60 Thus, we expected that this composite of FB and GG could offer the enhanced cell-adhesion capability and mechanical stability used in 3D bioprinting applications. Furthermore, it was envisioned that the GG/FB composite constructs showed improved structural stability and mechanical properties by ionic interaction and thrombin treatment.

To improve the structural integrity, the SF obtained from the silkworm Bombyx mori was selected for this study, which has been widely used in various tissue engineering applications.61 The SF has been increasingly recognized as a promising biomaterial for scaffold fabrication due to its excellent biocompatibility, remarkable mechanical properties, shape-memory capability, and tailorable degradability.62, 63 And, SF-based materials have been utilized for 3D bioprinting applications;48, 64–66 however, these materials were challenged for the printing process because of the conformational change of the SF by the shear stress. To avoid the conformational change during the printing process, we used a low concentration of the SF in the bioink formulation and chemically modified by the addition of methacrylate groups to the amine-containing groups of the SF. This functionalization creates a photo-crosslinkable hydrogel that can be used as an advantage in terms of in situ or post-processing crosslink.67 The potential of this functionalization was confirmed by our previous work,48 where SF-based bioink was developed by the methacrylate process using glycidyl methacrylate. This Sil-MA bioink was posteriorly used in a digital light processing (DLP) bioprinting process revealing good structure stability and biocompatibility.

Based on these strategies, we developed the novel hybrid tissue construct using the FB/GG-based bioink to provide a cell-friendly microenvironment and the silk-based bioink to obtain the structural integrity. In this study, we evaluated both GG/FB and Sil-MA bioinks by measuring the rheological properties, mechanical behavior, printability, and in vitro biological properties for the 3D bioprinting process. The presented results provided a proof of concept strategy that offered 3D bioprinted silk-reinforced hybrid tissue construct for advanced fibrocartilaginous regeneration. We achieved this hybrid tissue construct by the sequential deposition of the cell-laden GG/FB bioink and the Sil-MA bioink in a layer-by-layer fashion using a previously developed the ITOP system.8 Moreover, the in vivo animal study to validate the 3D bioprinted constructs containing cells revealed the fibrocartilage-like tissue formation with the structural maintenance at 10 weeks after implantation.

To avoid an exacerbated host immune response by the porcine cell source, we used an immunocompromised animal model for in vivo validation of the bioprinted cell-laden hybrid constructs. Although this animal model allowed us to determine the meniscus tissue maturation and formation in the bioprinted tissue constructs, a future preclinical large animal study using an autologous cell source will be mandatory to examine the host responses and functional recovery after the meniscus defect injury.

For the future clinical applications, the bioengineered tissue constructs should have appropriate biological properties to ensure the integration of the implant with the adjacent tissue.68 In addition, the mechanical behavior of the implanted tissue constructs should be tailored to match with the adjacent tissue, providing an immediate mechanical function.69 Previous works demonstrated the combination of a naturally derived material with a synthetic polymer as a hybrid biomaterial system for various tissue engineering applications; however, some of these approaches revealed the mechanical mismatching with native tissue by an inadequate stiffness and lack of tunability. Therefore, we believe that the combination of GG/FB and Sil-MA presents great versatility and capability to produce patient-specific tissue constructs with suitable biological and mechanical properties for fibrocartilaginous tissue regeneration. These naturally derived biomaterials could better mimic the native microenvironment to enhance the integration with the surrounding tissue.70

CONCLUSIONS

The bioprinted hybrid tissue construct for fibrocartilaginous tissue regeneration is fabricated by bioprinting of the cell-laden FB/GG-based bioink together with the silk-based bioink. These novel bioink formulations provide a cell-friendly biological microenvironment along with structural integrity. In vivo studies demonstrate that the bioprinted hybrid tissue constructs are capable to maintain their structural dimension with adequate biomechanical properties for 10 weeks after implantation and more importantly to allow tissue maturation with ECM deposition that resembles the native meniscus tissue. The versatility and tunability of these novel bioinks suggest the possible use of this system in different tissue engineering applications that require mechanically reinforced tissue constructs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Mahesh Devarasetty and Ms. Anna Young for technical assistance. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1P41EB023833-346 01) and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (PTDC/BBB-ECT/2690/2014 and PTDC/EMD-EMD/31367/2017). FCT/MCTES is acknowledged for the Ph.D. scholarship attributed to J.B.C. (PD/BD/113803/2015) and the financial support provided to J.S.-C. (IF/00115/2015), and J.M.O. (IF/01285/2015) under the program “Investigador FCT”.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

- Characterizations of the GG/FB composite bioinks: Rheological measurement, diffusion, swelling ratio, and compressive stress-strain curve

- Histological analysis of the printed cell-laden GG/FB4 constructs

- 1H-NMR spectra and methacrylate degrees of Sil-MAs

- Characterizations of the Sil-MA bioinks: Rheological measurement, compressive stress-strain curve, and swelling ratio

- Histological analysis of the printed GG/FB4 constructs without cells in vivo

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin M; Evans EJ, Fibrocartilage. J. Anat 1990, 171, 1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makris EA; Hadidi P; Athanasiou KA, The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7411–7431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen KA; Hall MJ; Golosinskiy A, Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl. Health Stat. Report 2009, (11), 1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe J; Almarza AJ, A review of in-vitro fibrocartilage tissue engineered therapies with a focus on the temporomandibular joint. Arch. Oral Biol 2017, 83, 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams GD; Frank RM; Gupta AK; Harris JD; McCormick FM; Cole BJ, Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005–2011. Am. J. Sports Med 2013, 41, 2333–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rongen JJ; van Tienen TG; Buma P; Hannink G, Meniscus surgery is still widely performed in the treatment of degenerative meniscus tears in The Netherlands. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc 2018, 26, 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sihvonen R; Paavola M; Malmivaara A; Itälä A; Joukainen A; Nurmi H; Kalske J; Ikonen A; Järvelä T; Järvinen TAH; Kanto K; Karhunen J; Knifsund J; Kröger H; Kääriäinen T; Lehtinen J; Nyrhinen J; Paloneva J; Päiväniemi O; Raivio M; Sahlman J; Sarvilinna R; Tukiainen S; Välimäki V-V; Äärimaa V; Toivonen P; Järvinen TLN, Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 2-year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis 2018, 77, 188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HW; Lee SJ; Ko IK; Kengla C; Yoo JJ; Atala A, A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat. Biotechnol 2016, 34, 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH; Kim I; Seol YJ; Ko IK; Yoo JJ; Atala A; Lee SJ, Neural cell integration into 3D bioprinted skeletal muscle constructs accelerates restoration of muscle function. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorgensen AM; Varkey M; Gorkun A; Clouse C; Xu L; Chou Z; Murphy SV; Molnar J; Lee SJ; Yoo JJ; Soker S; Atala A, Bioprinted Skin Recapitulates Normal Collagen Remodeling in Full-Thickness Wounds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2020, 26, 512–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim W; Lee H; Lee J; Atala A; Yoo JJ; Lee SJ; Kim GH, Efficient myotube formation in 3D bioprinted tissue construct by biochemical and topographical cues. Biomaterials 2020, 230, 119632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JH; Seol YJ; Ko IK; Kang HW; Lee YK; Yoo JJ; Atala A; Lee SJ, 3D Bioprinted Human Skeletal Muscle Constructs for Muscle Function Restoration. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z; Lee SJ; Cheng HJ; Yoo JJ; Atala A, 3D bioprinted functional and contractile cardiac tissue constructs. Acta Biomater 2018, 70, 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merceron TK; Burt M; Seol YJ; Kang HW; Lee SJ; Yoo JJ; Atala A, A 3D bioprinted complex structure for engineering the muscle-tendon unit. Biofabrication 2015, 7, 035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinton TJ; Jallerat Q; Palchesko RN; Park JH; Grodzicki MS; Shue H-J; Ramadan MH; Hudson AR; Feinberg AW, Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels. Sci. Adv 2015, 1, e1500758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying G-L; Jiang N; Maharjan S; Yin Y-X; Chai R-R; Cao X; Yang J-Z; Miri AK; Hassan S; Zhang YS, Aqueous Two-Phase Emulsion Bioink-Enabled 3D Bioprinting of Porous Hydrogels. Adv. Mater 2018, 30, e1805460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romanazzo S; Vedicherla S; Moran C; Kelly DJ, Meniscus ECM-functionalised hydrogels containing infrapatellar fat pad-derived stem cells for bioprinting of regionally defined meniscal tissue. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 2018, 12, e1826–e1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groen WM; Diloksumpan P; van Weeren PR; Levato R; Malda J, From intricate to integrated: Biofabrication of articulating joints. J. Orthop. Res 2017, 35, 2089–2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X; Lu Z; Wu H; Li W; Zheng L; Zhao J, Collagen-alginate as bioink for three-dimensional (3D) cell printing based cartilage tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 2018, 83, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong L; Wang SJ; Zhao XR; Zhu YF; Yu JK, 3D-printed poly(epsilon-caprolactone) scaffold integrated with cell-laden chitosan hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong S; Sycks D; Chan HF; Lin S; Lopez GP; Guilak F; Leong KW; Zhao X, 3D Printing of highly stretchable and tough hydrogels into complex, cellularized structures. Adv. Mater 2015, 27, 4035–4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aisenbrey EA; Tomaschke A; Kleinjan E; Muralidharan A; Pascual-Garrido C; McLeod RR; Ferguson VL; Bryant SJ, A Stereolithography-Based 3D Printed Hybrid Scaffold for In Situ Cartilage Defect Repair. Macromol. Biosci 2018, 18, 1700267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuurman W; Khristov V; Pot MW; van Weeren PR; Dhert WJ; Malda J, Bioprinting of hybrid tissue constructs with tailorable mechanical properties. Biofabrication 2011, 3, 021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moroni L; Boland T; Burdick JA; De Maria C; Derby B; Forgacs G; Groll J; Li Q; Malda J; Mironov VA; Mota C; Nakamura M; Shu W; Takeuchi S; Woodfield TBF; Xu T; Yoo JJ; Vozzi G, Biofabrication: A guide to technology and terminology. Trends Biotechnol 2018, 36, 384–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moroni L; Burdick JA; Highley C; Lee SJ; Morimoto Y; Takeuchi S; Yoo JJ, Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater 2018, 3, 21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X; Yan Y; Zhang R, Recent trends and challenges in complex organ manufacturing. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev 2010, 16, 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman AS, Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2002, 54, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutmacher DW, Polymers for Medical Applications. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, Buschow KHJ; Cahn RW; Flemings MC; Ilschner B; Kramer EJ; Mahajan S; Veyssière P, Eds. Elsevier: Oxford, 2001; pp 7664–7673. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maitz MF, Applications of synthetic polymers in clinical medicine. Biosurf. Biotribol 2015, 1, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coenen AMJ; Bernaerts KV; Harings JAW; Jockenhoevel S; Ghazanfari S, Elastic materials for tissue engineering applications: Natural, synthetic, and hybrid polymers. Acta Biomater 2018, 79, 60–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan UM; Sethuraman S, Electrospun Nanofibers as Scaffolds for Skin Tissue Engineering AU - Sundaramurthi, Dhakshinamoorthy. Polym. Rev 2014, 54, 348–376. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyle S; Jessop ZM; Al-Sabah A; Whitaker IS, ‘Printability’ of candidate biomaterials for extrusion based 3d printing: state-of-the-art. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critchley SE; Kelly DJ, Bioinks for bioprinting functional meniscus and articular cartilage. J. 3D Print. Med 2017, 1, 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy SV; De Coppi P; Atala A, Opportunities and challenges of translational 3D bioprinting. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2020, 4, 370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon H; Brown WE; Lee CA; Wang D; Paschos N; Hu JC; Athanasiou KA, Surgical and tissue engineering strategies for articular cartilage and meniscus repair. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 2019, 15, 550–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bredfeldt JS; Liu Y; Pehlke CA; Conklin MW; Szulczewski JM; Inman DR; Keely PJ; Nowak RD; Mackie TR; Eliceiri KW, Computational segmentation of collagen fibers from second-harmonic generation images of breast cancer. J. Biomed. Opt 2014, 19, 16007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devarasetty M; Skardal A; Cowdrick K; Marini F; Soker S, Bioengineered submucosal organoids for in vitro modeling of colorectal cancer. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 1026–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxton N; Smolan W; Bock T; Melchels F; Groll J; Jungst T, Proposal to assess printability of bioinks for extrusion-based bioprinting and evaluation of rheological properties governing bioprintability. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 044107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamin M; Ralphs JR, Biology of fibrocartilage cells. Int. Rev. Cytol 2004, 233, 1–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verdonk PC; Forsyth RG; Wang J; Almqvist KF; Verdonk R; Veys EM; Verbruggen G, Characterisation of human knee meniscus cell phenotype. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005, 13, 548–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox AJS; Bedi A; Rodeo SA, The basic science of human knee menisci: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2012, 4, 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newell N; Little JP; Christou A; Adams MA; Adam CJ; Masouros SD, Biomechanics of the human intervertebral disc: A review of testing techniques and results. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 2017, 69, 420–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez MJ; Brown J; Giordano J; Lin SJ; Omenetto FG; Kaplan DL, Silk based bioinks for soft tissue reconstruction using 3-dimensional (3D) printing with in vitro and in vivo assessments. Biomaterials 2017, 117, 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan L-P; Silva-Correia J; Ribeiro VP; Miranda-Gonçalves V; Correia C; da Silva Morais A; Sousa RA; Reis RM; Oliveira AL; Oliveira JM; Reis RL, Tumor growth suppression induced by biomimetic silk fibroin hydrogels. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 31037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribeiro VP; Silva-Correia J; Gonçalves C; Pina S; Radhouani H; Montonen T; Hyttinen J; Roy A; Oliveira AL; Reis RL; Oliveira JM, Rapidly responsive silk fibroin hydrogels as an artificial matrix for the programmed tumor cells death. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0194441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beck EC; Barragan M; Tadros MH; Gehrke SH; Detamore MS, Approaching the compressive modulus of articular cartilage with a decellularized cartilage-based hydrogel. Acta Biomater 2016, 38, 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chia HN; Hull ML, Compressive moduli of the human medial meniscus in the axial and radial directions at equilibrium and at a physiological strain rate. J. Orthop. Res 2008, 26, 951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SH; Yeon YK; Lee JM; Chao JR; Lee YJ; Seo YB; Sultan MT; Lee OJ; Lee JS; Yoon S.-i.; Hong I-S; Khang G; Lee SJ; Yoo JJ; Park CH, Precisely printable and biocompatible silk fibroin bioink for digital light processing 3D printing. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rittie L, Method for Picrosirius Red-Polarization Detection of Collagen Fibers in Tissue Sections. Methods Mol. Biol 2017, 1627, 395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makris EA; Hadidi P; Athanasiou KA, The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7411–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JH; Yoo JJ; Lee SJ, Three-dimensional cell-based bioprinting for soft tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2016, 13, 647–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy SV; Atala A, 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32, 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abelseth E; Abelseth L; De la Vega L; Beyer ST; Wadsworth SJ; Willerth SM, 3D printing of neural tissues derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells using a fibrin-based bioink. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2019, 5, 234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolesky DB; Homan KA; Skylar-Scott MA; Lewis JA, Three-dimensional bioprinting of thick vascularized tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3179–3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Z; Li Z; Jiang S; Bratlie KM, Chemically modified gellan gum hydrogels with tunable properties for use as tissue engineering scaffolds. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6998–7007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silva-Correia J; Oliveira JM; Caridade SG; Oliveira JT; Sousa RA; Mano JF; Reis RL, Gellan gum-based hydrogels for intervertebral disc tissue-engineering applications. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2011, 5, e97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levato R; Visser J; Planell JA; Engel E; Malda J; Mateos-Timoneda MA, Biofabrication of tissue constructs by 3D bioprinting of cell-laden microcarriers. Biofabrication 2014, 6, 035020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Visser J; Peters B; Burger TJ; Boomstra J; Dhert WJ; Melchels FP; Malda J, Biofabrication of multi-material anatomically shaped tissue constructs. Biofabrication 2013, 5, 035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skardal A; Atala A, Biomaterials for integration with 3-D bioprinting. Ann. Biomed. Eng 2015, 43, 730–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coutinho DF; Sant SV; Shin H; Oliveira JT; Gomes ME; Neves NM; Khademhosseini A; Reis RL, Modified gellan gum hydrogels with tunable physical and mechanical properties. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7494–7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma D; Wang Y; Dai W, Silk fibroin-based biomaterials for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 2018, 89, 456–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kasoju N; Bora U, Silk Fibroin in tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2012, 1, 393–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costa JB; Silva-Correia J; Oliveira JM; Reis RL, Fast setting silk fibroin bioink for bioprinting of patient-specific memory-shape implants. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1701021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Costa JB; Silva-Correia J; Ribeiro VP; da Silva Morais A; Oliveira JM; Reis RL, Engineering patient-specific bioprinted constructs for treatment of degenerated intervertebral disc. Mater. Today Commun 2019, 19, 506–512. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez MJ; Dixon TA; Cohen E; Huang W; Omenetto FG; Kaplan DL, 3D freeform printing of silk fibroin. Acta Biomater 2018, 71, 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sommer MR; Schaffner M; Carnelli D; Studart AR, 3D printing of hierarchical silk fibroin structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 34677–34685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy AR; Kaplan DL, Biomedical applications of chemically-modified silk fibroin. J. Mater. Chem 2009, 19, 6443–6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Makris EA; Gomoll AH; Malizos KN; Hu JC; Athanasiou KA, Repair and tissue engineering techniques for articular cartilage. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 2014, 11, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daly AC; Freeman FE; Gonzalez-Fernandez T; Critchley SE; Nulty J; Kelly DJ, 3D bioprinting for cartilage and osteochondral tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Brien FJ, Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.