Abstract

Neurotensin (NT) is an anorexic gut hormone and neuropeptide that increases in circulation following bariatric surgery in humans and rodents. We sought to determine the contribution of NT to the metabolic efficacy of vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG). To explore a potential mechanistic role of NT in VSG, we performed sham or VSG surgeries in diet-induced obese NT receptor 1 (NTSR1) wild-type and knockout (ko) mice and compared their weight and fat mass loss, glucose tolerance, food intake, and food preference after surgery. NTSR1 ko mice had reduced initial anorexia and body fat loss. Additionally, NTSR1 ko mice had an attenuated reduction in fat preference following VSG. Results from this study suggest that NTSR1 signaling contributes to the potent effect of VSG to initially reduce food intake following VSG surgeries and potentially also on the effects on macronutrient selection induced by VSG. However, maintenance of long-term weight loss after VSG requires signals in addition to NT.

Keywords: neurotensin, vertical sleeve gastrectomy, fat preference, food intake

Obesity and associated diseases have reached epidemic proportions but existing antiobesity pharmacotherapies show limited efficacy and are often associated with unacceptable adverse effects (1). Bariatric surgeries, such as vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), constitute the best current antiobesity intervention resulting in a large and sustained weight loss with concomitant improvement in comorbidities. The weight loss is achieved predominantly via reduced food intake accompanied by a shift in food preference toward healthier food choices (2-8). Despite the efficacy of bariatric surgeries, the molecular mechanisms underlying weight loss and altered feeding behavior are incompletely understood and continue to be a topic of investigation, aiming to find nonsurgical therapies to treat obesity.

Peripheral hormones, primarily from the gut, have been prime candidates in the search for mechanistic factors underlying the effects of bariatric surgery as many are increased in circulation following bariatric surgery. Many of these factors are anorexic and improve other metabolic endpoints such as glycemic control (9,10). However, studies in knockout (ko) mouse models indicate that single peripheral hormones do not mediate the effects of bariatric surgery on food intake and weight loss, including glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) (11,12), peptide YY (PYY) (13), glucagon-like peptide 2 (14), ghrelin (15), or growth/differentiation factor 15 (16). Even combined deletion of the receptors for GLP-1 and PYY does not reduce the ability of RYGB to cause weight loss (17). In contrast, human studies have implicated peripheral hormones as important contributors to the effects of bariatric surgery, particularly GLP-1 as a mediator of the weight-loss independent diabetes remission following bariatric surgery (18). In addition to peripheral hormones, changes in the gut microbiome and in the levels and composition of bile acids have been implicated in the beneficial metabolic outcomes of bariatric surgeries (19-22). Another potential candidate that may contribute to the effects of bariatric surgeries is the gut hormone and neuropeptide neurotensin (NT). NT causes an anorectic effect in rodents (23-25) and is increased in circulation following bariatric surgery in humans and rodents (24,26-28). We have previously shown that NT could be involved in mediating the reduced food intake following RYGB in rats using a NT receptor antagonist, which transiently restored food intake to the level of sham-operated rats (24).

NT receptor 1 (NTSR1) belongs to the NT receptor family and is the high affinity NT receptor responsible for the majority of NT effects, including feeding responses (29). Given the relevance of NT in feeding behavior following bariatric surgery, we investigated whether NTSR1-mediated NT signaling is associated with the efficacy of bariatric surgery. In the present study, we applied VSG surgery, one of the most common and efficacious bariatric procedures, to diet-induced obese NTSR1 ko mice, hypothesizing that NTSR1 ko mice would have an attenuated response to VSG surgery.

Material and Methods

Animals

Male NTSR1 ko mice (30-32) (#005826, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were bred at University of Michigan using heterozygous breeding pairs. Male wild-type (wt) littermates were used as control mice. Mice were placed on a high-fat diet (60% fat; #D12492, Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) from 6 to 7 weeks of age and maintained on this diet for 8 weeks to induce obesity. Two weeks before surgery they were single housed. Mice were kept at a 12/12 h light/dark cycle throughout the experiment with ad libitum access to food and tap water unless otherwise stated. All animal procedures were approved by and performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Michigan in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy

Weight- and fat-matched mice received VSG (ko: n = 11; wt: n = 13) or sham surgery (wt: n = 7; ko: n = 7) as previously described (33). Briefly, the surgeries were performed under isoflurane anesthesia, and the lateral 80% of the stomach was excised, leaving a gastric tube connected to the esophagus in the proximal end and the pylorus in the distal end. Sham surgeries involved opening the peritoneal cavity and applying manual pressure on the stomach with blunt forceps. Following surgery, mice were maintained on liquid Osmolite (Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL, USA) for 4 days, solid food was returned on the fourth day along with Osmolite, and from the fifth day mice were only provided solid food. Meloxicam (0.5 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously daily for 3 days after surgery for pain relief. Mice were kept for a total of 8 weeks postsurgery where body weight, food intake, and body composition (EchoMRI, Houston, TX, USA) were recorded. Postoperative deaths resulted in final group numbers of 7 wt sham, 6 ko sham, 9 wt VSG, and 6 ko VSG.

Macronutrient Preference

Macronutrient preference testing was performed at postoperative week 5. Mice were given access to 3 pure macronutrient diets [TD.02521 (carbohydrate), TD.02522 (fat), and TD02523 (protein); Envigo Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) simultaneously in separate containers. After 3 days of acclimation, nutrient intake was recorded daily for 3 days. The total caloric intake per day and the intake of each macronutrient per day were calculated and averaged over the 3 days. Percentage intake of each macronutrient in relation to total intake was also calculated. Due to diet spillage, 1 wt VSG was excluded from the analysis.

Mixed-meal Tolerance Test and Gastric Emptying

A mixed-meal tolerance test combined with gastric emptying was performed at postoperative week 3. Mice were fasted for 4 h in the early light phase. A baseline blood sample was collected, and mice were administered by mouth liquid mixed-meal (30 mg dextrose in 200 µL Ensure Plus; 1.41 kcal/g, 29% fat, Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL, USA) mixed with acetaminophen (100 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and blood glucose was measured at the indicated time points. Insulin was measured at baseline and at 15 min using the mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Crystal Chem, Cat # 90080, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA). Plasma acetaminophen levels were measured using Acetaminophen-L3K assay (Sekisui Diagnostics, Burlington, MA, USA).

Tissue Collection

Mice were fasted for 4 h before sacrifice. Prior to sacrifice, mice were placed in a clean cage, and a fresh fecal sample was collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Mice were sacrificed by decapitation, and trunk blood was collected and plasma prepared. Duodenal and cecal content were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Plasma Neurotensin Measurements

NT was measured using an in-house radioimmunoassay (34) in terminal samples (4 h fasting; samples collected in the light cycle) and in a tail blood sample taken from free-fed mice (samples collected in the light cycle) a few days prior to sacrifice. NT was furthermore measured in another cohort of VSG and sham operated FVB mice (n = 8 sham, n = 13 VSG) 4 weeks after surgery that were overnight fasted (samples collected in the light cycle).

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Generation of Gut Microbiota Profiles

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 100 mg of duodenal and cecal contents as well as from fecal pellets obtained from the 28 mice; in total, 84 samples were included in the 16S rRNA gene profiling. For DNA extraction, 3 cycles of bead-beating at 5.5 m/sec for 60 sec were carried out in a FastPrep-24 Instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA), and supernatants were purified using the NucleoSpin Soil kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 515F and 806R (35) in duplicate reactions as previously described (36). 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed in an Illumina Miseq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the V2 kit (Illumina; 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads), and raw sequence data were processed as previously described (37). A total of 1239 Zero-radius operational taxonomic units (Zotus) were detected in the 84 samples; analyses of gut microbiota composition included Zotus present in a proportion bigger than 0.0015% of total reads (38).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 8.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) repeated measurements with Tukey or Sidak multiple comparisons test for individual time points, mixed model analysis with Tukey multiple comparisons test for individual time points (if missing values were present), and 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test or unpaired t-tests were used as indicated in figure legends. The statistical analyses and graphical representations of the microbiota were performed using R v.3.5.1 with the aid of packages such as phyloseq v.1.26 and ggplot2 v.3. Compositional dissimilarity of the data set was investigated using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric. The Bray-Curtis metric was calculated on proportion-normalized data using the vegdist function from the vegan package. Principal coordinate analysis ordination plots were created to visualize the effect of the different groups on taxa composition. The principal coordinate analysis plots were created using the made4 and ggplot2 packages. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance statistical tests on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity were performed using the Adonis function from the vegan package with 1000 permutations. The effect of surgery and genotype on community diversity was investigated using Shannon Diversity metrics. The diversity metrics were calculated using the estimate richness function in the phyloseq package.

Results

NTSR1 ko Mice Had an Attenuated Reduction in Food Intake and Decreased Fat Preference After VSG

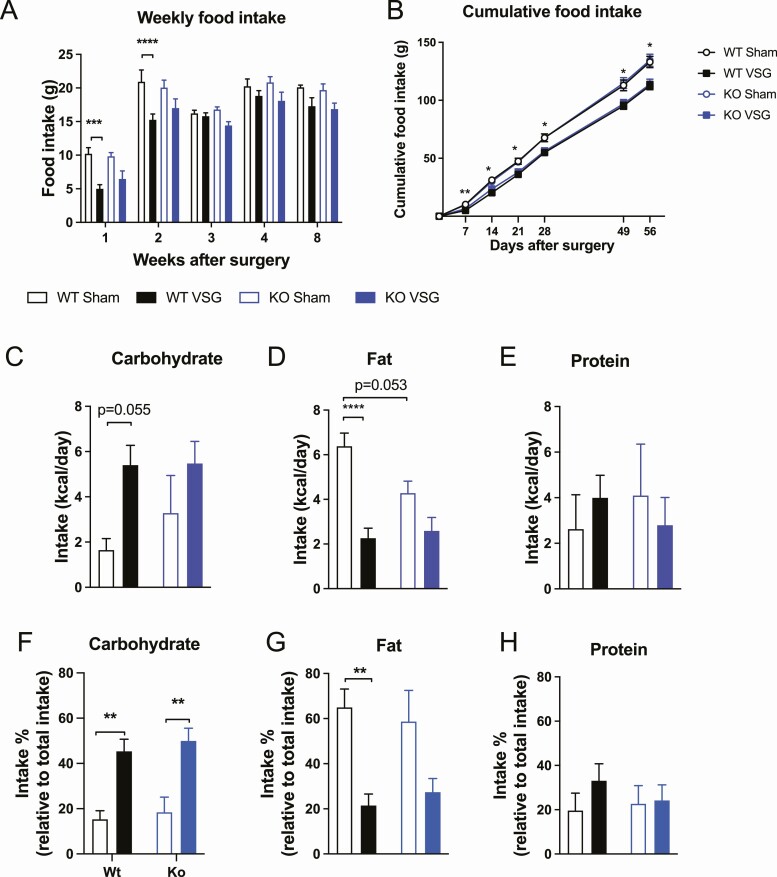

As expected, wt control mice had lower food intake after VSG compared to sham-operated wt mice during the recovery period up to 2 weeks postsurgery where the weight loss predominantly takes place (Fig. 1A) (16,19). During the following weeks, food intake was similar in sham-and VSG-operated wt control mice. In contrast, NTSR1 ko mice did not significantly lower their food intake after VSG surgery compared to ko sham mice (Fig. 1A). Cumulative food intake was lower in wt VSG mice compared to wt sham mice throughout the study, whereas cumulative food intake was not significantly lower in ko VSG mice compared to ko sham mice (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Food intake and macronutrient preference. (A) Weekly food intake, (B) cumulative food intake, (C) carbohydrate preference, (D) fat preference, (E) protein preference, (F) carbohydrate intake relative to total intake, (G) fat intake relative to total intake, and (H) protein intake relative to total intake. Data tested using mixed effects analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A and B), 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (C-H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 wt sham vs wt VSG. n = 7 (wt sham; A-H), n = 9 (wt VSG; A-B), n = 8 (wt VSG; C-H), and n = 6 (ko sham and ko VSG; A-H). Error bars represent SE of the mean.

It is well-described that bariatric surgery alters food preference toward healthier (ie, less fatty) foods (2,3,33). Two-way ANOVA analyses showed significant main effects of surgery on carbohydrate intake (P = 0.0084) and fat intake (P < 0.0001) and a significant interaction between surgery and genotype on fat intake (P = 0.03), indicating that surgery affected the genotypes differently with respect to changes in fat intake (Fig. 1C-1D). Tukey’s multiple comparison test showed that VSG surgery induced a trend toward increased carbohydrate intake (P = 0.055) and a marked decrease in fat intake in wt mice (Fig 1C-1D). In contrast, NTSR1 ko mice did not significantly increase carbohydrate intake or decrease fat intake following VSG (Fig. 1C-1D). Importantly, the basal preference for fat between NTSR1 wt and ko mice may have been different as a trend toward lower fat intake in ko sham mice compared to wt sham mice was observed (P = 0.053) (Fig. 1D). If normalizing the macronutrient intake to total intake, 2-way ANOVA analyses showed significant main effects of surgery on carbohydrate intake (P < 0.0001) and fat intake (P = 0.0002). Tukey’s multiple comparisons analyses showed that carbohydrate intake was significantly elevated in both wt VSG and ko VSG mice compared to wt sham and ko sham mice (Fig. 1F), while fat intake was only significantly reduced in wt VSG mice compared to wt sham mice (Fig. 1G). Total and relative protein intake was similar between groups (Fig. 1E and 1H).

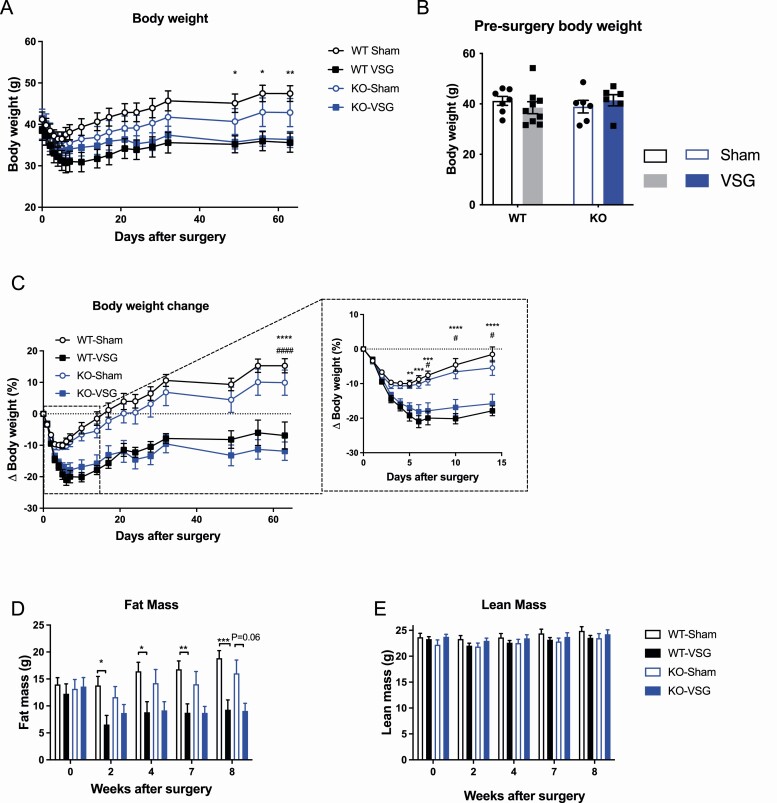

NTSR1 ko Mice Had Attenuated Loss of Fat Mass Following VSG

The wt control mice undergoing VSG surgery had significantly lower absolute body weight compared to wt sham mice, while the absolute body weight was not significantly different between NTSR1 ko sham and ko VSG mice (Fig. 2A). However, the presurgery body weight of the groups favored this body weight distribution with wt VSG mice having slightly lower body weight compared to wt sham mice while the opposite was true for ko groups (Fig. 2B). Thus, the relative body weight loss was similar between wt and ko mice throughout the 8 weeks of the study (Fig. 2C), except for a slightly delayed body weight loss in response to VSG in ko mice during the initial 2 weeks of the study (Fig. 2C, insert). The discrepancy between food intake and body weight data may be due to compensatory metabolic mechanisms such as energy expenditure, but this was not assessed in the present study. wt VSG mice had significantly lower fat mas compared to wt sham mice at all time points postsurgery, while fat mass between ko sham and ko VSG mice was similar except at week 8 where a trend toward lower fat mass in ko VSG mice was observed (P = 0.06) (Fig. 2D). There was a tendency for ko mice to reduce their fat mass after sham surgery, which was not seen in wt sham mice (Fig. 2D). This may contribute to the attenuated response to surgery in ko mice if floor effects limited the fat mass loss of ko VSG mice. No differences in lean mass were observed throughout the study (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Body weight and body composition. (A) Total body weight throughout study, (B) body weight before surgery, (C) change in body weight throughout study (insert shows first 15 days), (D) total fat mas throughout study, and (E) total lean mass throughout study. Data tested with 2-way ANOVA repeated measurements with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A and C-E) and 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (B). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 wt sham vs wt VSG, #P < 0.05 and ####P < 0.0001 ko sham vs ko VSG. n = 7 (wt sham), n = 9 (wt VSG), and n = 6 (ko sham and ko VSG). Error bars represent SE of the mean.

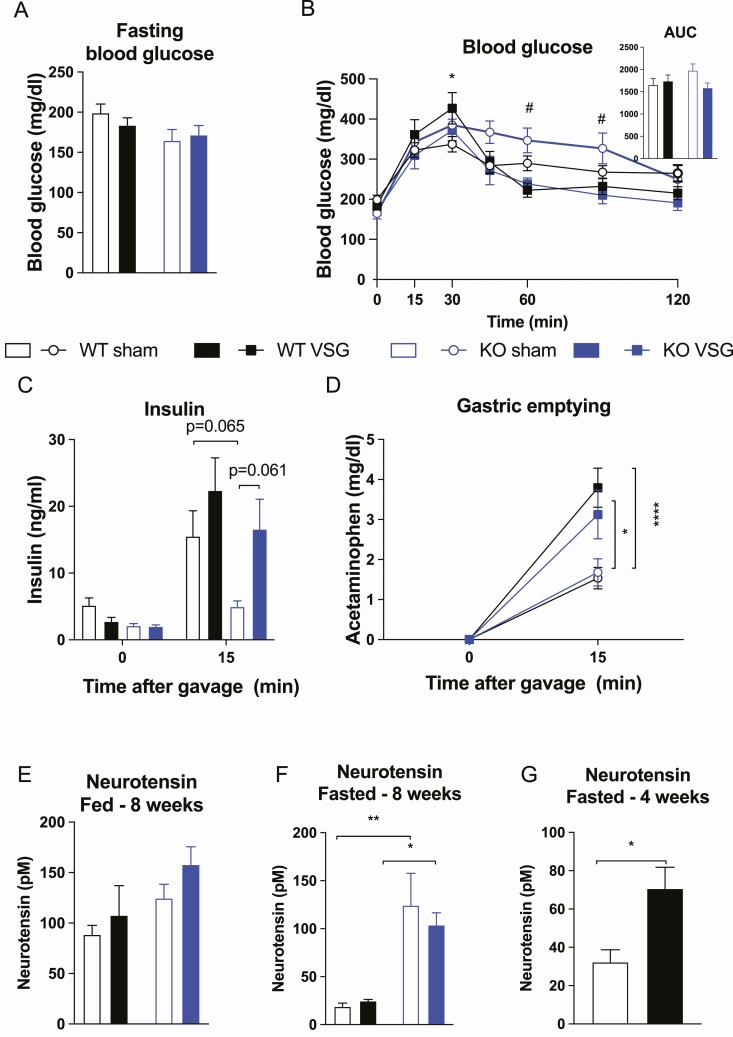

NTSR1 wt and ko Mice Had Similar Mixed-meal Tolerance and Gastric Emptying

All groups had similar fasted blood glucose levels as well as similar glucose excursions during a mixed-meal tolerance test (Fig. 3A-3B). Likewise, no differences in insulin levels were observed, however, there was a trend toward higher insulin in ko VSG compared to ko sham (P = 0.06) (Fig. 3C). Gastric emptying rate was similar between wt and ko mice but increased in VSG compared to sham mice as expected due to the surgical intervention (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Mixed meal tolerance test, gastric emptying, and plasma neurotensin levels. (A) Blood glucose levels after 4 h fasting, (B) glucose excursions and area under the curve during a mixed meal tolerance test, (C) insulin levels during a mixed meal tolerance test, (D) gastric emptying, (E) plasma neurotensin levels in free-fed mice 8 weeks after surgery, (F) plasma neurotensin levels in 4-h–fasted mice 8 weeks after surgery, and (G) plasma neurotensin levels in a separate cohort of FVB mice that were overnight fasted, 4 weeks after surgery. Data tested using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A, B insert, E, and F), mixed effects analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B and C), 2-way ANOVA repeated measurement with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (D), and unpaired t-test (G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001 wt sham vs wt VSG, # P < 0.05 ko sham vs ko VSG. n = 6 (wt sham; A and F), n = 7 (wt sham; B-D), n = 5 (wt sham; E), n = 9 (wt VSG; A-C), n = 6 (wt VSG; D), n = 8 (wt VSG; E), n = 7 (wt VSG; F), n = 6 (ko sham; A-C and E-F), n = 5 (wt VSG; D), n = 6 (ko VSG; A-B and E-F), n = 5 (ko VSG; C-D), n = 8 (sham; G), and n = 13 (VSG; G). Error bars represent SE of the mean.

NT Levels in Circulation Were Increased Transiently

When plasma NT levels were measured at study termination 8 weeks after surgery in 4-h fasted mice and a few days prior to sacrifice in free-fed mice, a significant main effect of genotype on fasted NT levels was observed (P < 0.0001). Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed higher NT levels in ko sham mice compared to wt sham mice and in ko VSG mice compared to wt VSG mice (Fig. 3F), probably reflecting a compensatory increase in response to the NTSR1 deficiency. No differences in NT levels were observed in free-fed mice (Fig. 3E). As the differences in the response to VSG between NTSR1 wt and ko mice was most evident in the first few weeks postsurgery, we hypothesized that changes in NT levels may reflect this. Therefore, we measured NT levels in a separate cohort of FVB mice (n = 8 sham and n = 13 VSG) that were fasted overnight at an earlier time point after surgery (4 weeks) and found an increase in circulating NT (Fig. 3G).

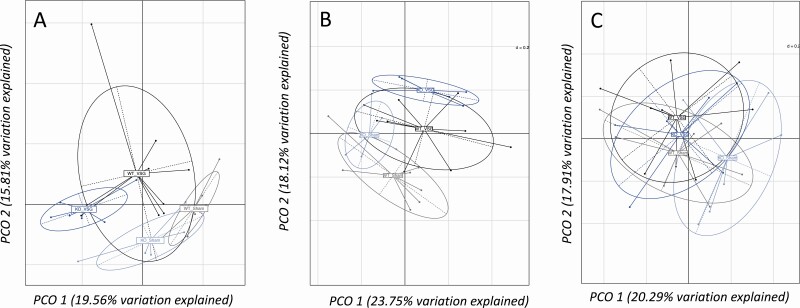

Gut Microbiota Profiles Were Regulated by Surgery and Genotype

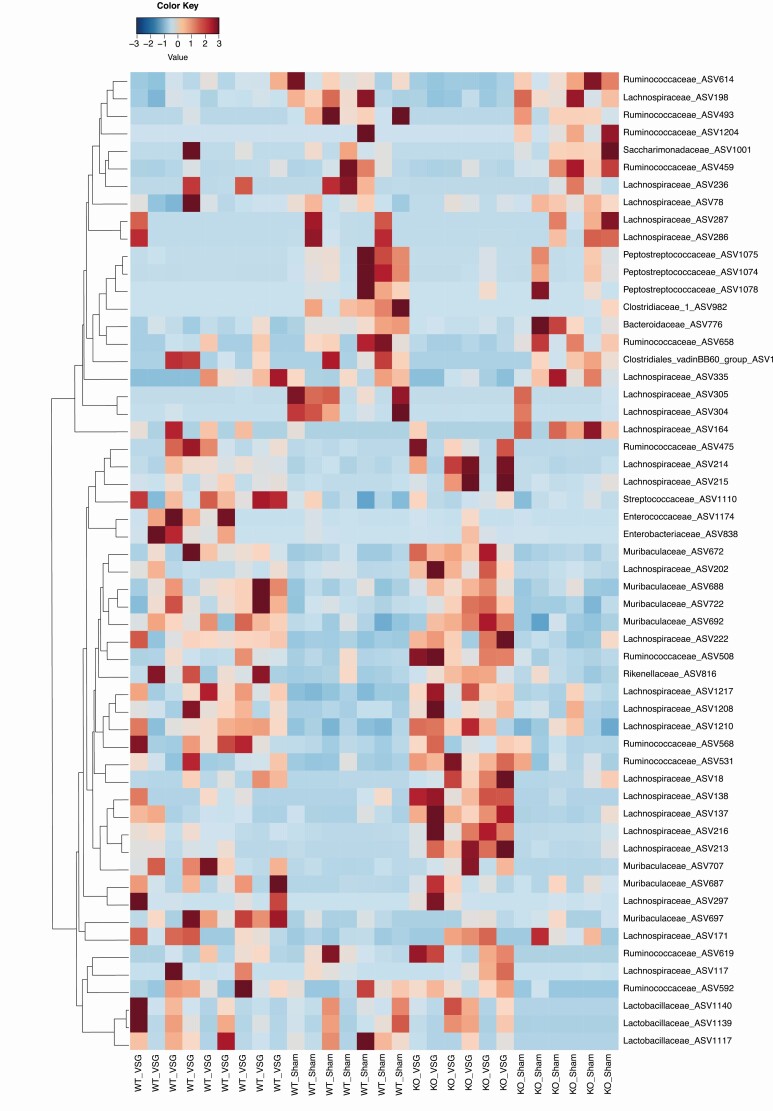

Significant differences were observed for overall gut microbiota composition between groups in cecum and feces (P = 0.001) (Fig. 4A and 4B) but not in duodenum (P = 0.09) (Fig. 4C). Overall gut microbiota composition in cecum and feces differed significantly also between genotypes (wt vs ko), and differed in all three tissues following surgery (sham vs VSG) (Fig. 4A-4C). Analysis of the relative abundance of specific microbial Zotus indicated differences in wt mice compared to ko mice with sham surgeries, which could reflect differences at baseline due to genotype, as also observed for the analysis of overall gut microbiota. In addition, we also observed that VSG altered the abundance of several microbial species both in wt and ko mice [Fig. 5 (cecum); also see Supplementary Figure 1 in (39) (duodenum) and Supplementary Figure 2 in (40) (feces)] (eg, several species in the Lachnospiraceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and lactic acid bacteria in the genera Enterococcus and Streptococcus). Similar changes were observed as a consequence of surgery in the work by Ryan et al (19). We also observed shifts in relative abundance of microbial species specifically in the wt or in the ko mice; in particular, we observed an increase of 1 species belonging to the genus Roseburia only in wt mice (ASV297) [Fig. 5; also see Supplementary Figure 2 in (40)], and a similar change was previously observed by Ryan et al in wt mice but not in farnesoid X receptor (FXR) ko mice after VSG (19).

Figure 4.

Gut microbiota composition after VSG. (A) Principal coordinates analysis for gut microbiota composition in samples collected from the cecum. We observed a significant difference of gut microbiota composition between groups (P = 0.001 and r2=0.25, Adonis 1000 permutations) and an effect of both surgery (P = 0.001 and r2=0.12, Adonis 1000 permutations) and genotype (P = 0.001 and r2=0.09, Adonis 1000 permutations). (B) Principal coordinates analysis for gut microbiota composition in samples collected from feces. We observed a significant difference of gut microbiota composition between groups (P = 0.001 and r2=0.26, Adonis 1000 permutations) and an effect of both surgery (P = 0.001 and r2 = 0.14, Adonis 1000 permutations) and genotype (P = 0.017 and r2 = 0.08, Adonis 1000 permutations). (C) Principal coordinates analysis for gut microbiota composition in samples collected from the duodenum. We observed no significant difference for gut microbiota composition between the groups (P = 0.09 and r2=0.15, Adonis 1000 permutations) and no effect of genotype (P = 0.237 and r2=0.05, Adonis 1000 permutations); however, there was a significant effect of surgery on gut microbiota composition (P = 0.026 and r2 = 0.07, Adonis 1000 permutations). Values in the brackets indicate the percentage of total variation explained by the first 2 principal components (PCO 1 and PCO 2, respectively). The analysis was performed on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity at the Zotu level. n = 7 (wt sham), n = 9 wt VSG, and n = 6 (ko sham and ko VSG).

Figure 5.

Heatmap of cecal microbiota profiles in wt and ko NTSR1 mice undergoing sham or VSG surgeries. Fifty-six ASV presented significantly different relative abundances between groups (adjusted P < 0.05, Wald test). The color scale indicates taxa relative abundance. n = 7 (wt sham), n = 9 wt VSG, and n = 6 (ko sham and ko VSG).

Discussion

In the present study, we show that NTSR1 ko mice have a transient attenuated response to VSG surgery in terms of anorexia, reduction in fat preference, and loss of fat mass compared to wt mice, during the first weeks after surgery. However, at week 8 postsurgery, food intake, body weight loss, and loss of fat mass were similar between NTSR1 wt and ko mice. These data indicate that NT could be a contributing factor to the beneficial metabolic outcomes of obesity surgery. This is supported by our previous data in RYGB rats where blocking NT signaling transiently using NT receptor antagonism restores food intake to the level of sham-operated rats (24). However, to achieve long-term weight loss after VSG, NT likely needs to act in concert with other gut signals.

Altered signaling via the gut-brain axis of hormones regulating feeding behavior and glycemia has been proposed as the mechanism for the reduced food intake, weight loss, and resolution of diabetes following bariatric surgery (10,20). However, studies using ko mouse models have yielded largely negative results regarding the necessity of single peripheral hormone candidates such as ghrelin, GLP-1, and PYY in mediating effects on food intake and body weight induced by bariatric surgery (11-13,15,17,33). The current study supports the notion that the long-term weight loss is likely mediated by the concomitant alteration of multiple gut signals.

Deletion of the bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 have attenuated the response to VSG surgery (19,22), although FXR was not found to have a similarly important role in RYGB surgery (41). As NT regulates bile acid release and enterohepatic bile acid recycling (42-46), we hypothesized that deletion of NTSR1 could impact FXR signaling by altering the amount and composition of bile acids in the lumen and/or in circulation. In turn, such changes can have an impact on the composition of the gut microbiome (19). Some VSG-induced changes in the gut microbiota observed specifically in FXR wt but not ko mice [ie, an increase in Roseburia, a species believed to have beneficial effects on host metabolism (47)], were also present specifically in NTSR1 wt but not ko mice. However, while NTSR1 deficiency attenuated anorexia in the initial phase postsurgery, deletion of FXR affected maintenance of weight loss through rebound hyperphagia in the later stages postsurgery (19). Thus, the diminished initial anorexia in response to VSG surgery in NTSR1 ko mice is likely not entirely dependent on altered FXR signaling and associated changes to the gut microbiota (19).

Among the most potent effects of surgery is to not just alter food consumption but also food choice in both humans and rodents (2-8). In a 3-choice test, VSG mice shift their preference to lower density options (15,19). These alterations in food choice have been hypothesized to be a contributor to some of the long-term benefits of surgery on a variety of endpoints (48-50) and may be predictive of postoperative weight loss in humans (51,52). Interestingly, this effect to alter food choice was attenuated in NTSR1 ko mice. Other work has linked altered vagal activity to regulate dopamine in the striatum to this effect of surgery on food choice (53). NTSR1 is expressed on vagal afferents (54) and on dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain (55), where they receive input from NT expressing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (56). Lateral hypothalamus NT neurons are important integrators of energy availability signals such as food cues and peripheral hormones and translate these into appropriate ingestive and locomotor output behaviors via NTSR1 on dopaminergic neurons (57-59). The projection seems particularly important for maintaining body weight homeostasis in states of negative energy balance (59), which could include VSG. Thus, deletion of NTSR1 may prevent VSG mice from responding appropriately to the altered hormonal and nutritional milieu following VSG surgery.

It is also possible that the attenuated response to VSG surgery in NTSR1 ko mice is driven by the inability of peripherally derived NT to exert its effects on central NTSR1. Pharmacological doses of NT (24,25) and half-life extended analogues reduce food intake through a melanocortin-dependent pathway (23). Importantly, in addition to reducing food intake, activity of the melanocortin system is also associated with reduced appetite for fat specifically (60-62), and the melanocortin 4 receptor has been implicated in the metabolic improvements following RYGB (63,64) but not following VSG in rats (65). Blocking NT action on proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons via deletion of NTSR1 may contribute to the attenuated initial anorexia and induction of fat aversion in NTSR1 ko mice. It is, however, uncertain whether the NT levels achieved after bariatric surgery are sufficient to activate the POMC system and suppress feeding and fat intake. In particular, the increase in NT levels we observed after VSG surgery in mice was less robust compared to what is seen in RYGB rats (24), These data combined with previous divergent findings between RYGB and VSG surgery (19,41,63-65) highlight the need to carefully consider differences between species and surgical procedures.

In conclusion, we have shown that mice with a whole-body deletion of NTSR1 have an attenuated response to VSG surgery in terms of initial decrease in food intake, loss of fat mass, and potentially food preference changes. Importantly, the genetic difference between wt and ko mice may have impacted results. Loss of central NTSR1 signaling in dopaminergic or POMC neurons could be important for mediating anorexia and fat preference changes associated with bariatric surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manuela Krämer for 16S rRNA gene sample preparation and sequencing and Alfor Lewis, Andriy Myronivych, and Mouhamaoule Toure for performing the vertical sleeve gastrectomy surgery.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the Project grants in Endocrinology and Metabolism—Nordic Region 2019 (#0057417) and Novo Nordisk Foundation NNF15OC0013655. In addition, it was funded from The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (www.metabol.ku.dk), which is supported by an unconditional grant (NNF10CC1016515) from the Novo Nordisk Foundation to University of Copenhagen. C.R. was financially supported by a postdoctoral grant (R231-2016-3031) from the Lundbeck Foundation. This work was also supported by NIH grants P30 DK089503, P01 DK117821, R01 DK119188 to R.J.S. The computations for microbiota analyses were performed on resources provided by SNIC through Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science (UPPMAX) under Project SNIC 2018-3-350.

Additional Information

Disclosures: R.J.S. receives research support from Novo Nordisk, Zafgen, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, and Ionis; acts as a consultant for Novo Nordisk, Scohia, Kintai Therapeutics, and Ionis; and owns equity in Zafgen, Calibrate, and Rewind.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nance K, Eagon JC, Klein S, Pepino MY. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy vs. roux-en-Y gastric bypass on eating behavior and sweet taste perception in subjects with obesity. Nutrients. 2017;10(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilson-Pérez HE, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA, et al. The effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on food choice in rats. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(2):288-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shin AC, Zheng H, Pistell PJ, Berthoud HR. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery changes food reward in rats. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(5):642-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathes CM, Bohnenkamp RA, Blonde GD, et al. Gastric bypass in rats does not decrease appetitive behavior towards sweet or fatty fluids despite blunting preferential intake of sugar and fat. Physiol Behav. 2015;142:179-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. le Roux CW, Bueter M, Theis N, et al. Gastric bypass reduces fat intake and preference. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(4):R1057-R1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kittrell H, Graber W, Mariani E, Czaja K, Hajnal A, Di Lorenzo PM. Taste and odor preferences following Roux-en-Y surgery in humans. PloS One. 2018;13(7):e0199508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ullrich J, Ernst B, Wilms B, Thurnheer M, Schultes B. Roux-en Y gastric bypass surgery reduces hedonic hunger and improves dietary habits in severely obese subjects. Obes Surg. 2013;23(1):50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. le Roux CW, Aylwin SJ, Batterham RL, et al. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg. 2006;243(1):108-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Mechanisms in bariatric surgery: Gut hormones, diabetes resolution, and weight loss. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):708-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ye J, Hao Z, Mumphrey MB, et al. GLP-1 receptor signaling is not required for reduced body weight after RYGB in rodents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(5):R352-R362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mokadem M, Zechner JF, Margolskee RF, Drucker DJ, Aguirre V. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on energy and glucose homeostasis are preserved in two mouse models of functional glucagon-like peptide-1 deficiency. Mol Metab. 2014;3(2):191-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boland B, Mumphrey MB, Hao Z, et al. The PYY/Y2R-deficient mouse responds normally to high-fat diet and gastric bypass surgery. Nutrients. 2019;11(3):585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel A, Yusta B, Matthews D, Charron MJ, Seeley RJ, Drucker DJ. GLP-2 receptor signaling controls circulating bile acid levels but not glucose homeostasis in Gcgr-/- mice and is dispensable for the metabolic benefits ensuing after vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Mol Metab. 2018;16:45-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chambers AP, Kirchner H, Wilson-Perez HE, et al. The effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy in rodents are ghrelin independent. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):50-52.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frikke-Schmidt H, Hultman K, Galaske JW, Jørgensen SB, Myers MG Jr, Seeley RJ. GDF15 acts synergistically with liraglutide but is not necessary for the weight loss induced by bariatric surgery in mice. Mol Metab. 2019;21:13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boland BB, Mumphrey MB, Hao Z, et al. Combined loss of GLP-1R and Y2R does not alter progression of high-fat diet-induced obesity or response to RYGB surgery in mice. Mol Metab. 2019;25:64-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papamargaritis D, le Roux CW. Do gut hormones contribute to weight loss and glycaemic outcomes after bariatric surgery? Nutrients. 2021;13(3):762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, et al. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509(7499):183-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pucci A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019;42(2):117-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tremaroli V, Karlsson F, Werling M, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty induce long-term changes on the human gut microbiome contributing to fat mass regulation. Cell Metab. 2015;22(2):228-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGavigan AK, Garibay D, Henseler ZM, et al. TGR5 contributes to glucoregulatory improvements after vertical sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Gut. 2017;66(2):226-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ratner C, He Z, Grunddal KV, et al. Long-acting neurotensin synergizes with liraglutide to reverse obesity through a melanocortin-dependent pathway. Diabetes. 2019;68(6):1329-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ratner C, Skov LJ, Raida Z, et al. Effects of peripheral neurotensin on appetite regulation and its role in gastric bypass surgery. Endocrinology. 2016;157(9):3482-3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooke JH, Patterson M, Patel SR, et al. Peripheral and central administration of xenin and neurotensin suppress food intake in rodents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(6):1135-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christ-Crain M, Stoeckli R, Ernst A, et al. Effect of gastric bypass and gastric banding on proneurotensin levels in morbidly obese patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3544-3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martinussen C, Dirksen C, Bojsen-Moller KN, et al. Intestinal sensing and handling of dietary lipids in gastric bypass-operated patients and matched controls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(1):28-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Näslund E, Grybäck P, Hellström PM, et al. Gastrointestinal hormones and gastric emptying 20 years after jejunoileal bypass for massive obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(5):387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Remaury A, Vita N, Gendreau S, et al. Targeted inactivation of the neurotensin type 1 receptor reveals its role in body temperature control and feeding behavior but not in analgesia. Brain Res. 2002;953(1-2):63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Opland D, Sutton A, Woodworth H, et al. Loss of neurotensin receptor-1 disrupts the control of the mesolimbic dopamine system by leptin and promotes hedonic feeding and obesity. Mol Metab. 2013;2(4):423-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim ER, Mizuno TM. Role of neurotensin receptor 1 in the regulation of food intake by neuromedins and neuromedin-related peptides. Neurosci Lett. 2010;468(1):64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bugni JM, Rabadi LA, Jubbal K, Karagiannides I, Lawson G, Pothoulakis C. The neurotensin receptor-1 promotes tumor development in a sporadic but not an inflammation-associated mouse model of colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(8):1798-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson-Pérez HE, Chambers AP, Ryan KK, et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy is effective in two genetic mouse models of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor deficiency. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2380-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuhre RE, Bechmann LE, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Hartmann B, Holst JJ. Glucose stimulates neurotensin secretion from the rat small intestine by mechanisms involving SGLT1 and GLUT2, leading to cell depolarization and calcium influx. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(12):E1123-E1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(17):5112-5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deschasaux M, Bouter KE, Prodan A, et al. Depicting the composition of gut microbiota in a population with varied ethnic origins but shared geography. Nat Med. 2018;24(10): 1526-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Djekic D, Shi L, Brolin H, et al. Effects of a vegetarian diet on cardiometabolic risk factors, gut microbiota, and plasma metabolome in subjects with ischemic heart disease: a randomized, crossover study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(18):e016518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10(1):57-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ratner C, Shin JH, Dwibedi C, et al. Ratner_FigS1. Figshare. Deposited May 6, 2021. 10.6084/m9.figshare.14550924.v1 [DOI]

- 40. Ratner C, Shin JH, Dwibedi C, et al. Ratner_FigS2. Figshare. Deposited May 6, 2021. 10.6084/m9.figshare.14550963.v1 [DOI]

- 41. Li K, Zou J, Li S, et al. Farnesoid X receptor contributes to body weight-independent improvements in glycemic control after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in diet-induced obese mice. Mol Metab. 2020;37:100980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiao Y, Yan W, Lu Y, Zhou K, Cai W. Neurotensin contributes to pediatric intestinal failure-associated liver disease via regulating intestinal bile acids uptake. Ebiomedicine. 2018;35:133-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43. Gui X, Degolier TF, Duke GE, Carraway RE. Neurotensin elevates hepatic bile acid secretion in chickens by a mechanism requiring an intact enterohepatic circulation. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;127(1):61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gui X, Carraway RE. Enhancement of jejunal absorption of conjugated bile acid by neurotensin in rats. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(1):151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gui X, Dobner PR, Carraway RE. Endogenous neurotensin facilitates enterohepatic bile acid circulation by enhancing intestinal uptake in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281(6):G1413-G1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamasato T, Nakayama S. Effects of neurotensin on the motility of the isolated gallbladder, bile duct and ampulla in guinea-pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;148(1):101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Neyrinck AM, Possemiers S, Verstraete W, De Backer F, Cani PD, Delzenne NM. Dietary modulation of clostridial cluster XIVa gut bacteria (Roseburia spp.) by chitin-glucan fiber improves host metabolic alterations induced by high-fat diet in mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(1):51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Behary P, Miras AD. Food preferences and underlying mechanisms after bariatric surgery. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74(4):419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miras AD, le Roux CW. Bariatric surgery and taste: novel mechanisms of weight loss. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(2): 140-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zakeri R, Batterham RL. Potential mechanisms underlying the effect of bariatric surgery on eating behaviour. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25(1):3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Søndergaard Nielsen M, Rasmussen S, Just Christensen B, et al. Bariatric surgery does not affect food preferences, but individual changes in food preferences may predict weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(12):1879-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hubert PA, Papasavas P, Stone A, et al. Associations between weight loss, food likes, dietary behaviors, and chemosensory function in bariatric surgery: a case-control analysis in women. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hankir MK, Seyfried F, Hintschich CA, et al. Gastric bypass surgery recruits a gut PPAR-α-striatal D1R pathway to reduce fat appetite in obese rats. Cell Metab. 2017;25(2):335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Egerod KL, Petersen N, Timshel PN, et al. Profiling of G protein-coupled receptors in vagal afferents reveals novel gut-to-brain sensing mechanisms. Mol Metab. 2018;12:62-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodworth HL, Perez-Bonilla PA, Beekly BG, Lewis TJ, Leinninger GM. Identification of neurotensin receptor expressing cells in the ventral tegmental area across the lifespan. eNeuro. 2018;5(1):ENEURO.0191-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Woodworth HL, Brown JA, Batchelor HM, Bugescu R, Leinninger GM. Determination of neurotensin projections to the ventral tegmental area in mice. Neuropeptides. 2018;68:57-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brown JA, Bugescu R, Mayer TA, et al. Loss of action via neurotensin-leptin receptor neurons disrupts leptin and ghrelin-mediated control of energy balance. Endocrinology. 2017;158(5):1271-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Leinninger GM, Opland DM, Jo YH, et al. Leptin action via neurotensin neurons controls orexin, the mesolimbic dopamine system and energy balance. Cell Metab. 2011;14(3):313-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Woodworth HL, Batchelor HM, Beekly BG, et al. Neurotensin receptor-1 identifies a subset of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons that coordinates energy balance. Cell Rep. 2017;20(8): 1881-1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Samama P, Rumennik L, Grippo JF. The melanocortin receptor MCR4 controls fat consumption. Regul Pept. 2003;113(1-3):85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. van der Klaauw AA, Keogh JM, Henning E, et al. Divergent effects of central melanocortin signalling on fat and sucrose preference in humans. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tung YC, Rimmington D, O’Rahilly S, Coll AP. Pro-opiomelanocortin modulates the thermogenic and physical activity responses to high-fat feeding and markedly influences dietary fat preference. Endocrinology. 2007;148(11): 5331-5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hatoum IJ, Stylopoulos N, Vanhoose AM, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptor signaling is required for weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):E1023-E1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zechner JF, Mirshahi UL, Satapati S, et al. Weight-independent effects of roux-en-Y gastric bypass on glucose homeostasis via melanocortin-4 receptors in mice and humans. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(3):580-590.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mul JD, Begg DP, Alsters SI, et al. Effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy in melanocortin receptor 4-deficient rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(1):E103-E110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.