Abstract

Metabolites control immune cell functions, and delivery of these metabolites in a sustained manner may be able to modulate function of the immune cells . In this study, alpha-ketoglutarate (aKG) and diol based polymeric-microparticles (termed paKG MPs) were synthesized to provide sustained release of aKG and promote an immunosuppressive cellular phenotype. Notably, after association with dendritic cells (DCs), paKG MPs modulated the intracellular metabolic-profile/pathways, and decreased glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in vitro. These metabolic changes resulted in modulation of MHC-II, CD86 expression in DCs, and altered the frequency of regulatory T cells (Tregs), and T-helper type-1/2/17 cells in vitro. This unique strategy of intracellular delivery of key-metabolites in a sustained manner provides a new direction in immunometabolism field-based immunotherapy with potential applications in different diseases associated with immune disorders.

Keywords: immunometabolism, immunoengineering, dendritic cell, lymphocytes, metabolites

1. Introduction

Immunometabolism reprogramming is an emerging and exciting new field that is involved in the induction, progression, and therapy of several diseases such as cancer, infections, autoimmune disorders, and Alzheimer’s among others1-5. Notably, modulation of immunometabolism can be performed by delivery of cell permeable metabolites (e.g., 2-hydroxyglutarate)2 or enzymatic inhibitors (e.g., 2-deoxyglucose)6. For example, regulatory T cell (Treg - immunosuppressive) and T-helper type 17 (Th17 - pro-inflammatory) differentiation can be controlled by modulating the glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 1 (GOT1) enzyme, which has direct implications in immunosuppressive applications. On the other hand, metabolites provided via dietary interventions may improve immune cell function in pro-inflammatory applications such as cancer7-9. Notably, increasing energy production from the Krebs cycle without affecting glycolysis can reduce the function of pro-inflammatory effector T-cells, without affecting the function of regulatory anti-inflammatory Tregs (required for regeneration)10. These strategies can be targeted toward the adaptive branch of the immune system to generate effector function. Interestingly, dendritic cells (DCs) that form the bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses, are capable of inducing robust adaptive and innate immune responses, which is advantageous in diseases such as cancer, infections, and wound healing.

Interestingly, DCs play an important role in inflammatory disorders, such as wound healing 11,12, potentially by secreting growth factors11-14. Therefore, targeting DCs that may not only modulate the innate cells (e.g., neutrophils) in inflammatory disorders, but also adaptive cells (e.g. regulatory T cells). Importantly, activated immune cells (e.g., macrophages type 1, activated DCs, and Th1) have an enhanced glycolysis profile in various pro-inflammatory environments, which hampers faster anti-inflammatory responses 15-17. Therefore, modulating the energy-metabolic pathways of the immune cells can be a viable strategy for controlling macrophages and DC responses and affect the inflammatory responses.

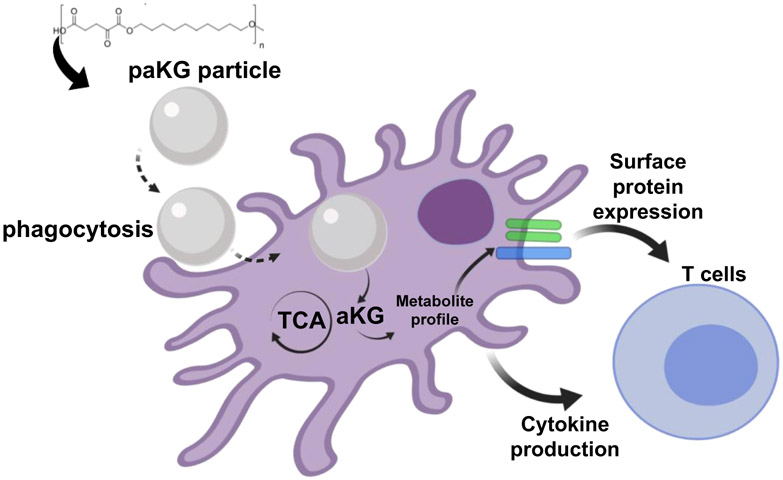

In this study, we demonstrate that delivery of aKG (a Krebs cycle metabolite, and involved in immunosuppression)18 and a diol (feeds into the Krebs cycle and Fatty acid oxidation involved in immunosuppression)1,19 after a one-time treatment lead to modulation of the DC metabolism, DC function and modulation of adaptive immune responses in the form of T cell function (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Central-carbon metabolite-based polymers modulate adaptive immune responses by changing the intracellular metabolites of the dendritic cells.

2. Results

2.1. Central-carbon aKG metabolite-based microparticles (MPs) release aKG in a sustained manner.

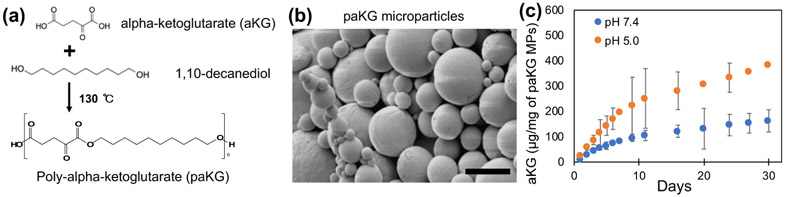

Steady state intracellular concentrations are needed to achieve the desired immunomodulation effect. Although, esterification of aKG molecules makes them cell permeable, aKG would need to be given in high and frequent dosages to achieve the desired effect in vivo. The high and frequent dosages are needed to overcome fast diffusion and elimination from the body caused by the low molecular weight. Therefore, polymers of aKG were generated, which can then degrade over a period of time to release aKG in a sustained manner after one-time application. Specifically, aKG was reacted with 1,10-decanediol to generate a polymer with a number-average molecular weight (Mn) of 15.3 – 23.9 kDa (Figure 2a), which was determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Figure S1 and S2).

Figure 2: Central-carbon metabolite-based microparticles release metabolites in a sustained manner.

(a) Schema of paKG synthesis. (b) Scanning electron microscope micrograph of paKG microparticles (MPs) (scale bar = 5 μm). (c) Cumulative release kinetics of alpha-ketoglutarate (aKG) from paKG MPs determined via high performance liquid chromatography (n = 3, avg ± SD).

Next, in order to ensure that these polymers can deliver aKG intracellularly in phagocytes (e.g. DCs), these polymers were formulated into phagocytosable MPs using oil-in-water emulsions (DCs can phagocytose particles < 15 μm20). The formation of particles was confirmed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and (Figure 2b), the average size of these particles was determined to be 4 μm using dynamic light scattering, which matched SEM analyses. In order to test if these particles could release aKG in a sustained manner, release kinetics experiments in pH 7.4 (1X PBS, physiological pH) and in pH 5.0 (100 mM acetate buffer) were performed. The amount of aKG released as a function of time was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which demonstrates that the particles were able to release aKG in a sustained fashion for at least 30 days. Moreover, the particles released aKG faster and at a higher amount at pH 5.0 as compared to pH 7.4. Cumulative release of aKG from paKG MPs is shown in Figure 2c. Supernatant from paKG particles was visualized under scanning electron microscope at increasing magnification at multiple spots (representative images shown) to confirm that no particles were left in the supernatant (Figure S6). It should be noted that the release of aKG in DCs is not required for 30 days, as the DCs post-phagocytosis many not live for 30 days.

2.2. DCs are capable of associating with paKG MPs

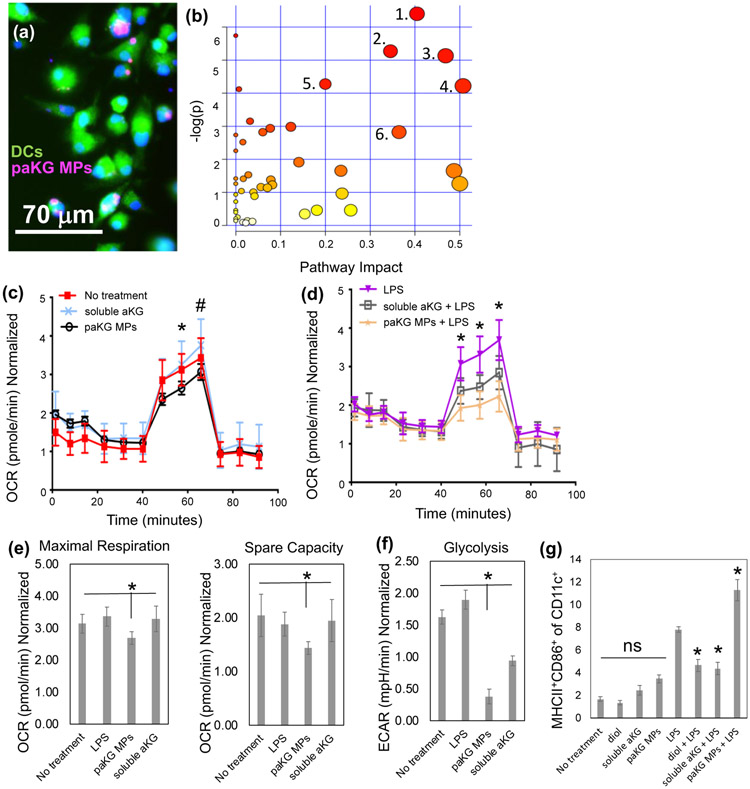

Although, DCs play an important role in modulating immune responses, the modulation in DC function after exposure to TCA metabolites is not well understood. In this study, we tested the ability of paKG MPs to deliver aKG, potentially a key-immunosuppressive metabolite in TCA cycle, to DCs. In order for the intracellular sustained delivery of aKG to occur, DCs should be able to associate the paKG MPs. To determine if DCs are capable of associating with paKG MPs, bone marrow derived DCs were cultured for 60 minutes with Rhodamine 6G encapsulated paKG MPs. These cells were then fixed and imaged using a fluorescent microscope. It was observed that DCs were able to successfully associate with the paKG MPs (Figure 3a). It should be noted that the particle size is much larger than the size of the endosome that might contain spontaneously released dye from the particles, which strongly suggests that the particles are associating or potentially internalized by DCs.

Figure 3: paKG microparticles affect function of dendritic cells by modulating their metabolism.

(a) Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) are able to associate with paKG microparticles, as observed by fluorescent micrograph (paKG MP – magenta, cytosol – green, nucleus – blue; scale bar = 70 μm). (b) paKG MPs modulate intracellular metabolite levels as observed by significant (p<0.05) changes in 113 metabolites (out of 299 analyzed using LC-MS/MS), and their respective signaling pathways. - 1 – Glycine/Serine/Threonine 2 – Arginine biosynthesis, 3 - Glyoxylate metabolism, 4 – Glutamate metabolism, 5 – Arginine metabolism, 6 – Glutathione metabolism. Pathway impact – number of metabolites modified significantly in a pathway; log(p) – level of modulation (n=3). (c,d) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of DCs is reduced when cultured with paKG MPs in the presence of LPS (d) (* - p<0.05; all groups significantly different than each other) or (c) absence of LPS (*, # - p<0.05, * - paKG MPs significantly different than soluble aKG and no treatment; # - paKG MPs significantly different than soluble aKG). (e) Maximal respiration and spare capacity of DCs when cultured with paKG MPs, and (f) glycolysis of DCs in the presence of paKG MPs (n = 10, avg ± SEM, * - p<0.05). (g) Activation of DCs in the presence of paKG MPs as indicated by frequency of MHCII+CD86+ in CD11c+ cells. (n = 5, avg ± SEM, * - p<0.05 – significantly different than LPS; ns = not significant).

2.3. paKG MPs modulate intracellular metabolite profile in DCs

DC function can be modulated by changing the intracellular metabolite profile21. Since, paKG MPs release aKG in a sustained manner, the ability of these particles to modulate intracellular metabolite levels was measured using LC-MS22-28. Modulation in intracellular metabolite levels in DCs was determined by culturing BMDCs with paKG MPs. The intracellular metabolites were isolated, quantified using LC-MS/MS, normalized to protein amount, and the levels of these metabolites were compared to no treatment control.

Enrichment analysis was conducted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database searches and metabolite intensities for different conditions was determined. The enrichment analysis of 299 reliably detected metabolites (using LC-MS) showed significant (p<0.05) perturbations or changes in the levels of glutamate, glycine/threonine/serine, alanine/aspartate/arginine and glutathione metabolisms, among others. Notably, large impact coefficient (>0.50) was observed in glutamate pathway suggesting the greatest impact of aKG delivery on the intracellular glutamate pathway metabolite levels (Figure 3b). Specifically, L-glutamate, 4-aminobutanoate and asparagine in the glutamate pathway were 3-6 fold higher in DCs treated with paKG MPs as compared to the no treatment control. Moreover, in the arginine pathway, aspartate, acetyl-ornithine and L-citrulline are upregulated in DCs treated with paKG MPs approximately 4-fold as compared to the no treatment control (Figure S3). Notably, these metabolites are involved in immune suppression via DCs29-31.

Interestingly, although large impact coefficients were not observed in other metabolic pathways, certain metabolites involved in DC-mediated immunosuppression such as kynurenine (>6-fold increase), were significantly affected as compared to the no treatment. Moreover, the intracellular levels of aKG were not significantly different when compared to the no treatment control. Since glutamate and succinate were significantly upregulated, this suggests quick metabolization of aKG intracellularly. Overall, these data demonstrate that the paKG MPs modulate intracellular metabolism of DCs.

Additionally, in ordert to ensure that the changes in DC metabolism are not due to endotoxins present in the paKG MPs, endotoxin tests were performed. Endotoxin levels were found to be <0.05 endotoxin units/mL for the paKG MPs, thus suggesting that the releaese of metabolites might be responsible fort he modification in DC metabolism.

2.4. paKG MPs reduce glycolysis and spare capacity in DCs

Intracellular metabolite changes in DCs due to paKG MPs suggest that the metabolic pathways in DCs might be modulated as well. Notably, upregulation of glycolysis and metabolic respiration are known to play an important role in DC activation19. Therefore, in order to test if the paKG MPs modulate glycolysis and metabolic respiration, Seahorse Assays were performed to determine the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used as a positive control, and no treatment was used as a negative control. Additionally, extracellularly added soluble aKG to the cell culture was used as a control.

It was observed that the paKG MPs have a lower trend of OCR as compared to the soluble aKG and no treatment groups. Importantly, in the presence of LPS (mimicking inflammation e.g. in wound healing), paKG substantially decreased the OCR in DCs, suggesting substantial decrease in the metabolic respiration (Figure 3c, 3d). In order to further analyze this data, basal respiration without glucose, maximal respiration in the presence of glucose, and spare capacity (determines the ability of the cell to respond to an energetic demand) was determined. It was observed that the DCs treated with paKG MPs had higher basal respiration, lower maximal respiration and lower spare capacity than the no treatment control (Figure 3e).

In addition, glycolysis was significantly decreased in DCs cultured with paKG MPs as compared to LPS (positive control) and no treatment (negative control). Interestingly, soluble aKG decreased glycolysis in DCs compared to the no treatment control; however, soluble aKG had higher glycolysis levels in DCs as compared to paKG MPs (Figure 3f). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the paKG MPs reduce the metabolic activity of DCs even in the presence of LPS. Thus, these data suggest that paKG MPs might be beneficial in preventing uncontrolled inflammation due to reduced DC metabolic activity.

2.5. paKG MPs do not activate DCs in vitro

The metabolism of DCs can play an important role in its function including changes in MHC-II, CD86 expression and adaptive immune responses1,19,21. In order to test if paKG MPs modulated DC metabolism, can modify DC function, MHC-II, and CD86 expression was determined using flow cytometry (representative flow plots - Figure S4).

It was observed that the paKG MPs do not activate DCs as compared to untreated immature DCs, since frequency of MHC-II+CD86+ was not significantly different from each other. On the other hand, LPS (positive control), significantly upregulated the frequency of MHC-II+CD86+ in DCs (Figure 3g). Additionally, the controls of 1,10-decanediol, and soluble aKG, added at the equivalent amount as the paKG MPs did not significantly change the MHC-II+CD86+ expression in CD11c+ DCs as compared to the no treatment control and the paKG MP condition (Figure 3g). Notably, in the presence of LPS, paKG MPs upregulate activation of DCs, thus suggesting that the inflammatory response to DCs is not modified by particles. Interestingly, addition of soluble aKG or diol (same quantity as the final paKG MPs) prevented activation of DCs in the presence of LPS, which suggests that individual components in large quantities added as bolus modulate the activation state in the preseence of inflammation. Overall, these data suggest that DCs may have an immunosuppressive phenotype in the presence of paKG MPs, and therefore may modulate adaptive immune responses.

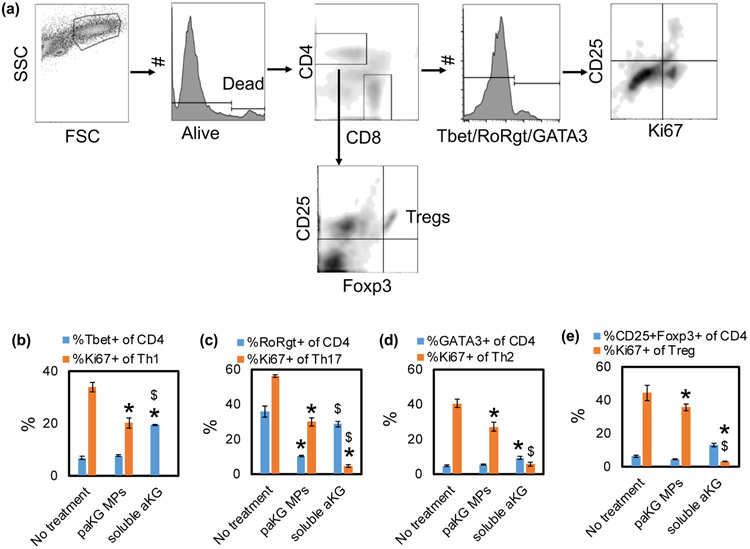

2.6. paKG MPs decreases pro-inflammatory T cell responses in allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction

DCs are effective modulators of T cell responses, which are essential for generating adaptive immune responses. paKG MPs modulate DC phenotype, which might also modulate T cell responses. Therefore, a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) with BALB/c mice-derived CD3+ T-cells and C57BL/6j mice-derived DCs were cultured with the paKG MPs. Co-culture of untreated DCs and T cells was used as control. These cells were cultured for 48-72 hours and the frequency of T helper type 1 (Th1 - CD4+Tbet+), Th2 (CD4+GATA3+), Tc1 (CD8+Tbet+) and Treg (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+), along with proliferation (Ki67+) and activation (CD25+) in these cells (Figure 4a) was determined. The DCs that were treated with paKG MPs down-regulated Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg population proliferation in the MLR (Figure 4b-e). Moreover, the DCs that were treated with soluble aKG also down-regulated Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg population proliferation in the MLR. Notably, the percentage decrease in the frequency of proliferating Th1 (1.7-fold decrease) and Th17 (2 fold decrease) population was substantially higher as compared to the frequency of prolfierating Treg population decrease (1.2 – fold decrease), suggesting preferential decrease in pro-inflammatory cell type. Moreover, the decrease in Treg proliferation in soluble aKG group was 8-fold lower than the paKG MP group, thus suggesting the difference in exposing aKG intracellularly versus extracellularly. Additionally, it was observed that the paKG MPs did not modulate the frequency of CD4+ T cell percentage in the MLR (Figure S5) as compared to the no treatment control or soluble aKG control. These data strongly suggest that paKG MPs by themselves may prevent CD4+ pro-inflammatory immune activation.

Figure 4: paKG microparticles modulate allogeneic adaptive immune responses in vitro.

(a) Schematic of flow plot analysis. (b) T helper type 1 cell frequency (Th1). (c) T helper type 17 cell frequency (Th17). (d) T helper type 2 cell frequency (Th2). (e) Regulatory T cell frequency (Treg). (n = 3-6, avg ± SEM, * - p<0.05 - significantly different than no treatment control; $ - significantly different than paKG MPs).

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which demonstrates that one-time application of aKG metabolite-based polymeric microparticles can lead to modulation of the immune system. Energy metabolic reprogramming can orchestrate immune cell polarization and contribute to functional plasticity1,32,33. Notably, it has been demonstrated that immune cells can generate an anti-inflammatory response when cell permeable aKG is delivered to macrophages18. However, delivery of these molecules in vivo can be challenging due to the quick diffusion (within seconds) of small molecules in vivo34. Therefore, in this work, a polymer made of aKG metabolite was generated that could release aKG in a sustained manner. This is the first evidence of Krebs cycle metabolite-based polymers that can be used to deliver metabolites in a sustained fashion in vitro, and lead to modulation of the metabolism of immune cells.

Metabolism modulating enzyme inhibitor drugs can also be used to alter the function of macrophages and DCs, and thus modulate disease outcomes1,21,32. For example, global immune suppression can be achieved using glycolytic inhibitors 2-deoxyglucose6. However, these inhibitors can also lead to prevention of proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and hence may not be suitable for anti-inflammatory applications.35 Therefore, development of a strategy that does not modulate the glycolytic enzymes but still leads to local suppression of immune cells can be beneficial for anti-inflammatory applications.

Targeting phagocytic cells (e.g. macrophages, DCs) in a tissue, where there is a diverse type of cell population is challenging. Therefore, microparticles made of the aKG polymer that can be picked by phagocytic cells, were utilized in this study for intracellular delivery of aKG. Interestingly, the transporter of aKG, GPR99 expression on DCs is not well known. Furthermore, recently it was demonstrated that dimethyl alpha-ketoglutarate when added to antigen presenting cells were able to modulate these cells at the epigenetic scale and also effect their metabolism18. Therefore, we expect that addition of soluble aKG should modulate the metabolite levels of the DCs as well. These studies support our results that intracellular delivery of aKG indeed modulate the metabolic profile of cells. Interestingly, these paKG MPs also provide an added advantage of encapsulating and delivering drugs intracellularly in phagocytic cells, which was demonstrated by delivering rhodamine as a representative fluorescent drug molecule dye. This strategy can further be utilized to deliver proteins, peptides or other drugs that can then modulate the function of these phagocytic cells.

In a pro-inflammatory milieu, a series of cellular and humoral immune responses are involved in the recruitment of immune cells. Specifically, innate immune cells such as DCs, which are professional APCs are known to infiltrate the injection sites12. Importantly, DCs form a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune system, and modulate the function of lymphocytes such as T cells36,37. T cells play a crucial role in defending against in both the inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phases of immune responses13,38. The data presented herein demonstrate that paKG MPs might assist in anti-inflammatory responses by releasing aKG intracellularly or extracellularly in a sustained manner.

4. Conclusion

In summary, metabolite-based polymers provide a new technique to deliver metabolites intracellularly and locally to modulate the metabolism of immune cells. In this study, paKG MPs were generated that could not only modulate DC function but also modulate T cell functions in vitro.

5. Experimental Section

5.1. Polymer synthesis and characterization

Ketoglutaric acid and 1,10-decanediol were mixed at equimolar ratio in a round-bottom flask. This mixture was stirred at 130°C for 48 hrs under nitrogen. The polymer thus generated was precipitated in methanol solution, and the unreacted monomers were removed by multiple (3X) precipitation steps. Residual methanol was then evaporated off using a rotary evaporator, and the polymers were then dried under vacuum at room temperature for 48 hrs.

1H-NMR spectroscopy was performed on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer using deuterated chloroform (CDCl3 - VWR, Radnor, PA), with a concentration of 5mg/ml. All 1H NMR experiments are reported in δ or parts per million (ppm) unit, and were measured relative to the chloroform H-signal (7.26 ppm) in CDCl3, unless stated differently. The following abbreviations were used to indicate multiplicities: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), br (broad), and tt (triplet of triplets). Coupling constants are expressed in hertz (Hz). 1H NMR (500 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.21 (t, 82H), 4.03 (t, 85H), 3.11 (t, 88H), 2.94 (t, 1H), 2.62 (t, 88H), 1.68 (tt, 91H), 1.57 (tt, 91H), 1.25 (br, 571H).

The molecular weight of the polymer was determined using GPC and 1H NMR spectroscopy. GPC was performed using a Waters Alliance e2695 HPLC system interfaced to a light scattering detector (miniDAWN TREOS) and an Optilab T-rEX differential refractive index (dRI) detector controlled using Astra v6.1 software. The mobile phase was tetrahydrofuran (THF) Optima (inhibitor-free) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and molecular weights were determined either via a calibration curve prepared using Agilent low dispersity polystyrene standards of 500, 200, 100, 30, 10, and 5 kDa or by determining the refractive index increment using the RI detector and using the light scattering detector response to determine an absolute weight-average molecular weight (Mw). The paKG samples were dissolved in THF at ~1.0 mg/mL and passed through 0.22 μm filters before injection to the GPC system. For molecular weight determination by 1H NMR spectroscopy, the integration of the peaks attributed to the end group protons were compared to the integrations of the peaks from the main-chain backbone protons to determine the number-average molecular weight (Mn).

5.2. Microparticle synthesis and characterization

paKG polymers were utilized to generate microparticles using a water-oil-water emulsion method. In order to generate microparticles, first, 50 mg of the polymers were dissolved in 1 mL of dichloromethane (DCM). This solution was then added to 10 mL of 2% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution in deionized water (DIH2O) and homogenized at 30,000 rpm using a handheld homogenizer for 2 min. This emulsion was then added to 50 mL of 1 % (vol/vol) PVA solution and stirred at 400 rpm for 3 hrs to remove DCM. The particles thus formed were then washed 3 times by centrifuging at 2000 X g for 5 min (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY), removing the supernatant and resuspending in DIH2O. These particles were then freeze dried and used for next experiments.

The particles were imaged using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) XL30 Environmental FEG - FEI at Erying Materials Center at Arizona State University. Moreover, the size of the particles was quantified using dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano, Cambridge, UK).

Release kinetics of the metabolites were determined by incubating 5 mg of the microparticles in 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and placed on a rotator at 37 °C. Next, triplicates of each release sample were centrifuged at 2000 X g for 5 min. After centrifugation, 800 μL of the supernatant was removed and placed into a separate 1.5 mL tube (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) and then replaced by 800 μL of new buffer. Collection days were intially everyday for the first 7 days. This then transitioned to 3-5 days a week until 30 days was reached.

The amount of metabolite released was then determined by developing a new method in a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Specifically, the mobile phase of 0.02 M H2SO4 in water was used. A 50 μL of injection volume was utilized in a Hi-Plex H, 7.7 × 300 mm, 8 μm column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). A flow rate of 1.2 mL/min was utilized and the absorbance was determined using a UV detector at 210 nm. The area under the curve was determined in order to determine the concentration using the ChemStation analysis software as per manufacturer’s directions.

5.3. Dendritic cell isolation and culture

Immature bone marrow-derived DCs were generated from 6-8 week-old female C57BL/6j mice in accordance with protocol approved by the Arizona State University (protocol number 19-1688R) using a modified 10-day protocol36,39,40. Briefly, femur and tibia from mice were isolated and kept in wash media composed of DMEM/F-12 (1:1) with L-glutamine (VWR, Radnor, PA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologics, Flowery Branch, GA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (VWR, Radnor, PA). The ends of the bones were cut and bone marrow was flushed out with 10 ml wash media and mixed to make a homogeneous suspension. Red blood cells were lysed by incubating and resuspending the pellet in 3mL 1X red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer for 3 min at 4 °C. The cell suspension was then washed twice with wash media and re-suspended in DMEM/F-12 with L-glutamine (VWR, Radnor, PA), 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% sodium pyruvate (VWR, Radnor, PA), 1% non-essential amino acids (VWR, Radnor, PA), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (VWR, Radnor, PA) and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (VWR, Radnor, PA) (DC media). All % values shown here are vol/vol. This cell suspension was then seeded in a tissue culture-treated T-75 flask (day 0). After 48 hrs (day 2), floating cells were collected, centrifuged, re-suspended in fresh media and seeded on low attachment plates (VWR, Radnor, PA) for 6 additional days. Half of the media was changed every alternate day. At the end of 6 days (day 8), cells were lifted from the low attachment wells by gentle pipetting, re-suspended and seeded on tissue culture-treated polystyrene plates for 2 more days before treating them. On day 10, cells were treated with either 0.1 μg/ml of paKG MPs or 0.1 μg/mL of soluble aKG and LPS conditions were administered 1 μg/mL of LPS. Purity, yield and immaturity of DCs (CD11c, MHC-II and CD86) were verified via immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry. Dendritic cells were isolated from at least 3 separate mice for each experiment.

5.4. Mixed lymphocyte reactions

Spleens were isolated from 6–8-week-old BALB/c mice. Single cell suspensions were prepared by mincing the spleen through a 70 μm pore sized cell strainer. The effluent was centrifuged for 5 min at 300 X g. The cells were then resuspended in 3 mL 1X RBC lysis buffer for 3 min at 4 °C. Next the cells were spun down at 300Xg for 5 min and the pellet was re-suspended in 4 μL of buffer (0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA in PBS) per million cells. Negative selection of CD3+ T-cells was performed according to manufacturer’s recommendation (Miltenyi Biosciences, San Diego, CA). A biotin-labeled antibody cocktail (CD8a (Ly-2) (rat IgG2a), CD11b (Mac-1) (rat IgG2b), CD45R (B220) (rat IgG2a), DX5 (rat IgM) and Ter-119 (rat IgG2b); Miltenyi) was added (10 μL per 10 million cells) and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C. Buffer (30 μL) and anti-biotin microbeads (10 μL) were added to the mixture per 10 million cells. After 15 min incubation at 4°C, cells were centrifuged at 300Xg for 5 min and re-suspended in 500 μL of buffer per 100 million cells. A magnetic column was then utilized to collect CD3+ T-cells. The CD3+ T-cells were centrifuged at 300Xg for 5 min and used in mixed lymphocyte reaction. Bone marrow derived DCs were isolated from C57BL/6j mice and were treated prior to the addition of T cells. Mixed lymphocyte reaction was performed at DC:T cell ratio of 1:5 for 48-72 hours.

5.5. LC-MS metabolomics studies

Bone marrow derived DCs from C57BL/6j were cultured in 6 well plates at 1 million cells per well. paKG MPs were added at 50 μg/well and no treatment was utilized as a control. After 24 hrs of culture, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were gently rinsed with 2 mL of 37 °C PBS. Next, immediately, 1 mL of 80:20 methanol:H2O (−80 °C) into the plates, and the plates were then placed on dry ice to quench metabolism and perform extraction. After 30 min of incubation on dry ice the cells were scraped using a cell scraper (VWR, Radnor, PA), and transferred into centrifuge tubes. The tubes were then spun at 16,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, USA). The soluble extract was removed into a vial and completely dried. The pellets were utilized to measure the total protein using Nanodrop 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The LC-MS/MS method was performed according to previous protocols22-28. Briefly, LC-MS/MS were performed using Agilent 1290 UPLC-6490 QQQ-MS (Santa Clara, CA) system. A total of 10 μL of the processed samples were injected twice, for analysis using negative ionization mode and a total of 4 μL of the processes sample for analysis using positive ionization mode. Both chromatographic separations were performed in hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) mode on a Waters XBridge BEH Amide column (150 x 2.1 mm, 2.5 μm particle size, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The flow rate utilized in these studies was 0.3 mL/min, auto-sampler temperature was kept at 4 °C, and the column compartment was set at 40 °C. The mobile phase was composed of Solvents A - 10 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM ammonium hydroxide in 95% H2O/5% ACN and Solvent B - 10 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM ammonium hydroxide in 95% acetonitrile (ACN)/5% H2O. After the initial 1 min isocratic elution of 90% B, the percentage of Solvent B decreased to 40% at t=11 min. The composition of Solvent B maintained at 40% for 4 min (t=15 min), and then the percentage of B gradually went back to 90% to prepare for the next injection.

The mass spectrometer is equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Targeted data acquisition was performed in multiple-reaction-monitoring (MRM) mode. A total of ~320 MRM transitions in negative and positive modes were observed. The whole LC-MS system was controlled by Agilent Masshunter Workstation software (Santa Clara, CA). The extracted MRM peaks were integrated using Agilent MassHunter Quantitative Data Analysis (Santa Clara, CA).

5.6. Seahorse assay

Glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation were measured with the Seahorse Extracellular Flux XF-96) analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA) as previously described41. Briefly, cells were seeded in Seahorse XF-96 plates at a density of 50,000 cells per well and cultured for 24 hrs in the presence of 10 μg/well of paKG MPs or equivalent amount of soluble aKG, in the presence of absence of 1 μg/mL of LPS. After 24 hrs, cells were changed to unbuffered DMEM in the absence of glucose. Sequential injections were performed with D-glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 mM), and 2-deoxyglucose (100 mmol/L). The extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) after the injection of D-glucose was a measure of glycolysis, and the ECAR after the injection of oligomycin represented maximal glycolytic capacity. Non-glycolytic activity was quantified by the measure of ECAR after the injection of 2-deoxyglucose. Samples were analyzed with 10 technical replicates.

For oxidative phosphorylation, 24 hrs after cell seeding, media was changed to unbuffered DMEM containing 2mM glutamine, 1mM pyruvate, and 10 mM glucose. Sequential injections were performed with oligomycin (2 mM), 7 Carbonyl cyanide-4 (trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (1 mM), and antimycin/rotenone (1 mM) to modify mitochondrial membrane potential. The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) after the injection of oligomycin was a measure of ATP-linked respiration and the OCR after the injection of FCCP represented maximal respiratory capacity. Basal respiration was quantified by the measure of OCR prior to the injection of oligomycin. Samples were analyzed with 10 technical replicates.

5.7. Flow cytometry

All the antibodies were purchased and used as is (BD biosciences, Tonbo Biosciences, BioLegend, Thermo Scientific, Invitrogen). Flow staining buffers were prepared by generating 0.1% bovine serum albumin (VWR, Radnor, PA), 2mM Na2EDTA (VWR, Radnor, PA) and 0.01% NaN3 (VWR, Radnor, PA). Live/dead staining was performed using fixable dye eF780 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Flow cytometry was performed by following manufacturer’s recommendations using Attune NXT Flow cytometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The antibodies used in these studies are shown in the table below.

Table.

| Target | Fluorophore | Company | Catalog # | Clone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CD4 | BB700 | BD Biosciences | 566407 | RM4-5 |

| 2 | CD8 | APC-R700 | BD Biosciences | 564983 | 53-6.7 |

| 3 | CD25 | PECy7 | BD Biosciences | 552880 | PC61 |

| 4 | CD11c | PE | BioLegend | 117308 | N418 |

| 5 | CD86 | SB600 | ThermoFisher Scientific | 63-0862-82 | GL1 |

| 6 | MHC | APC | BioLegend | 107614 | M5/114.15.2 |

| 7 | Tbet | BV785 | BioLegend | 644835 | 4B10 |

| 8 | FoxP3 | eF450 | Invitrogen | 48-5773-82 | FJK-16s |

| 9 | RORγT | BV650 | BD Biosciences | 564722 | Q31-378 |

| 10 | Ki67 | FITC | Invitrogen | 11-5698-82 | SolA15 |

| 11 | GATA3 | BV711 | BD Biosciences | 565449 | L50-823 |

5.11. Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Comparison between two groups was performed using Student’s t-test (Microsoft, Excel). Comparisons between multiple treatment groups were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons, and p-values ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism Software 6.0 (San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Seo, School of Molecular Sciences, ASU for providing access to DLS. The authors would also like to acknowledge the start up funds provided by ASU for completion of this study.

References

- 1.O’Neill LAJ and Pearce EJ, J. Exp. Med, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu T, Stewart KM, Wang X, Liu K, Xie M, Kyu Ryu J, Li K, Ma T, Wang H, Ni L, Zhu S, Cao N, Zhu D, Zhang Y, Akassoglou K, Dong C, Driggers EM and Ding S, Nature, , DOI: 10.1038/nature23475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assmann N, O’Brien KL, Donnelly RP, Dyck L, Zaiatz-Bittencourt V, Loftus RM, Heinrich P, Oefner PJ, Lynch L, Gardiner CM, Dettmer K and Finlay DK, Nat. Immunol, , DOI: 10.1038/ni.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steed AL, Christophi GP, Kaiko GE, Sun L, Goodwin VM, Jain U, Esaulova E, Artyomov MN, Morales DJ, Holtzman MJ, Boon ACM, Lenschow DJ and Stappenbeck TS, Science (80-. )., , DOI: 10.1126/science.aam5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulland TK, Song WM, Huang SCC, Ulrich JD, Sergushichev A, Beatty WL, Loboda AA, Zhou Y, Cairns NJ, Kambal A, Loginicheva E, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Virgin HW, Unanue ER, Wang Y, Artyomov MN, Holtzman DM and Colonna M, Cell, , DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abboud G, Choi SC, Kanda N, Zeumer-Spataro L, Roopenian DC and Morel L, Front. Immunol, , DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malvi P, Chaube B, Singh SV, Mohammad N, Pandey V, Vijayakumar MV, Radhakrishnan RM, Vanuopadath M, Nair SS, Nair BG and Bhat MK, Cancer Metab., , DOI: 10.1186/s40170-016-0162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung H-Y and Park YK, J. Cancer Prev, , DOI: 10.15430/jcp.2017.22.3.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins BD, Pauli C, Xing D, Wang DG, Li X, Wu D, Amadiume SC, Goncalves MD, Hodakoski C, Lundquist MR, Bareja R, Ma Y, Harris EM, Sboner A, Beltran H, Rubin MA, Mukherjee S and Cantley LC, Nature, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu R-TT, Zhang M, Yang C-LL, Zhang P, Zhang N, Du T, Ge M-RR, Yue L-TT, Li X-LL, Li H and Duan R-SS, J. Neuroinflammation, 2018, 15, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinish M, Cui W, Stafford E, Bae L, Hawkins H, Cox R and Toliver-Kinsky T, Wound Repair Regen., , DOI: 10.1111/wrr.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyes BE, Liu S, Asare A, Naik S, Levorse J, Polak L, Lu CP, Nikolova M, Pasolli HA and Fuchs E, Cell, , DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Muinck E, Pruthi D, Conejo-Garcia J and Moodie K, Scand. Cardiovasc. J [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregorio J, Meller S, Conrad C, Di Nardo A, Homey B, Lauerma A, Arai N, Gallo RL, DiGiovanni J and Gilliet M, J. Exp. Med, , DOI: 10.1084/jem.20101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weyand CM, Zeisbrich M and Goronzy JJ, Curr. Opin. Immunol, 2017, 46, 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okano T, Saegusa J, Nishimura K, Takahashi S, Sendo S, Ueda Y and Morinobu A, Sci. Rep, , DOI: 10.1038/srep42412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin Y, Choi S-C, Xu Z, Zeumer L, Kanda N, Croker BP and Morel L, J. Immunol, 2016, 196, 80–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu PS, Wang H, Li X, Chao T, Teav T, Christen S, DI Conza G, Cheng WC, Chou CH, Vavakova M, Muret C, Debackere K, Mazzone M, Da Huang H, Fendt SM, Ivanisevic J and Ho PC, Nat. Immunol, , DOI: 10.1038/ni.3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly B and O’Neill LAJ, Cell Res., 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion JA and Mitragotri S, Pharm. Res, , DOI: 10.1007/s11095-008-9626-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Everts B and Pearce EJ, Front. Immunol, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi X, Wang S, Jasbi P, Turner C, Hrovat J, Wei Y, Liu J and Gu H, Anal. Chem, , DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jasbi P, Mitchell NM, Shi X, Grys TE, Wei Y, Liu L, Lake DF and Gu H, J. Proteome Res, , DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parent BA, Seaton M, Sood RF, Gu H, Djukovic D, Raftery D and O’Keefe GE, JAMA Surg., , DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sood RF, Gu H, Djukovic D, Deng L, Ga M, Muffley LA, Raftery D and Hocking AM, Wound Repair Regen., , DOI: 10.1111/wrr.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll PA, Diolaiti D, McFerrin L, Gu H, Djukovic D, Du J, Cheng PF, Anderson S, Ulrich M, Hurley JB, Raftery D, Ayer DE and Eisenman RN, Cancer Cell, , DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu H, Carroll PA, Du J, Zhu J, Neto FC, Eisenman RN and Raftery D, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed, , DOI: 10.1002/anie.201609236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jasbi P, Baker O, Shi X, Gonzalez L, Wang S, Anderson S, Xi B, Gu H and Johnston C, Food Funct., , DOI: 10.1039/c9fo01082c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bronte V and Zanovello P, Nat. Rev. Immunol, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simioni PU, Fernandes LGR and Tamashiro WMSC, Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol, , DOI: 10.1177/0394632016678873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC and Al-Khami AA, Front. Immunol, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce EJ and Everts B, Nat. Rev. Immunol, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van den Bossche J, Baardman J, Otto NA, van der Velden S, Neele AE, van den Berg SM, Luque-Martin R, Chen HJ, Boshuizen MCS, Ahmed M, Hoeksema MA, de Vos AF and de Winther MPJ, Cell Rep., 2016, 17, 684–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun K, Tang Y, Li Q, Yin S, Qin W, Yu J, Chiu DT, Liu Y, Yuan Z, Zhang X and Wu C, ACS Nano, , DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b02386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falkenberg K, Rohlenova K, Luo Y and Carmeliet P, Nat. Metab, 2019, 1, 937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acharya AP, Sinha M, Ratay ML, Ding X, Balmert SC, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali DAA and Little SR, Adv. Funct. Mater, , DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201604366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acharya AP, Clare-Salzler MJ and Keselowsky BG, Biomaterials, , DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Havran WL and Jameson JM, J. Immunol, , DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acharya AP, Dolgova NV, Clare-Salzler MJ and Keselowsky BG, Biomaterials, , DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acharya AP, Dolgova NV, Xia CQ, Clare-Salzler MJ and Keselowsky BG, Acta Biomater., , DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis M, Kenny HA, Ashcroft B, Mukherjee A, Johnson A, Zhang Y, Helou Y, Batlle R, Liu X, Gutierrez N, Gao X, Yamada SD, Lastra R, Montag A, Ahsan N, Locasale JW, Salomon AR, Nebreda AR and Lengyel E, Cell Metab., , DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.